Abstract

Treatment for Chagas disease with currently available medications is recommended universally only for acute cases (all ages) and for children up to 14 years old. The World Health Organization, however, also recommends specific antiparasite treatment for all chronic-phase Trypanosoma cruzi-infected individuals, even though in current medical practice this remains controversial, and most physicians only prescribe palliative treatment for adult Chagas patients with dilated cardiomyopathy. The present opinion, prepared by members of the NHEPACHA network (Nuevas Herramientas para el Diagnóstico y la Evaluación del Paciente con Enfermedad de Chagas/New Tools for the Diagnosis and Evaluation of Chagas Disease Patients), reviews the paradigm shift based on clinical and immunological evidence and argues in favor of antiparasitic treatment for all chronic patients. We review the tools needed to monitor therapeutic efficacy and the potential criteria for evaluation of treatment efficacy beyond parasitological cure. Etiological treatment should now be mandatory for all adult chronic Chagas disease patients.

TEXT

There are an estimated 8 million chronic Chagas disease (CD) patients in Latin America (1), a large proportion of whom do not receive specific antiparasite treatment, and a growing infected population in the United States, Canada, and Europe (2). Antiparasitic treatment for Chagas disease (CD) is recommended universally for acute cases and for children up to 14 years old in most countries (3). Despite the inclusion of chronic patients in the guidelines, most doctors only prescribe symptomatic treatment of cardiomyopathy and digestive symptoms, avoiding antiparasitic drugs. At a meeting of clinical CD experts held in 1983, the use of etiological treatment for chronic stages was not recommended, pending more solid evidence of its efficacy (4) and of autoimmune mechanism involvement (5). Natural and elicited immunoglobulins and effector immune cells produced or modified during Trypanosoma cruzi infection can directly or indirectly affect heart tissue. There is no evidence that any putative autoimmune mechanisms, which may be secondary aggravating factors in the progression to cardiomyopathy, are primary causes of the chronic pathology (6). It is unclear, in addition, whether autoimmune reactions can be avoided if the infection is prevented or controlled (7), although it has been experimentally demonstrated that elimination of the parasite results in the reduction or elimination of autoimmune responses in the chronic phase of infection (8, 9).

In addition to neglecting adult chronic patient treatment by adopting the 1983 recommendations, the lack of even a tentative recommendation had a negative impact on the chronic patients' perceptions regarding their illness. These patients are labeled as “chagasic” and not simply as T. cruzi-infected persons, leading to social stigma and negative economic and psychological effects from carrying a lethal, cureless, and disabling disease (10). A similar conflict between infection and disease existed for AIDS and leprosy. Chronic progression in both cases, similar to that in CD, evolves differentially in each patient, leading to a shift in current clinical management to the use of pathogen-specific treatments (3).

Scientific evidence regarding the role of the parasite, Trypanosoma cruzi, as a stimulus and trigger for tissue damage has accumulated over the last 2 decades, providing a solid basis to reconsider antiparasitic treatment for chronic adult patients. The present article reviews the evidence and presents arguments for antiparasitic treatment of adult chronic patients, representing the opinion of clinical and biomedical scientists of the NHEPACHA network and coinciding with international guidelines that now recommend offering treatment to these patients (3, 11, 12).

PATHOGENESIS OF CHRONIC CHAGAS DISEASE: CHRONIC PERSISTENCE OF THE PARASITE?

Following the acute phase of T. cruzi infection, CD patients evolve a chronic phase which is initially asymptomatic (indeterminate form of CD). This form of CD is defined by T. cruzi infection (positive parasitological and/or serological tests), the absence of clinical disease symptoms, and normal electrocardiogram (EKG), thorax radiography, and colonic/esophageal imaging tests. However, around 30% to 40% of chronically infected individuals will develop symptomatic disease over time (13). Biomarkers to follow each patient's evolution are currently being developed, assessed, and standardized. Several studies have highlighted the key role of myocardial inflammation in the progressive fibrotic cardiomyopathy of chronic cardiac CD (14). Evidence for chronic persistence of infective parasites after the acute infection, both in areas where T. cruzi is endemic and where it is not, includes vertical transmission or transfusion and transplant transmission, which only occur if there are viable parasites in chronically infected mothers or blood/transplant donors (15, 16). In addition, chronic persistence is evident from clinical reactivations of immune-depressed patients or transplanted or HIV-infected individuals (17, 18), by isolation of parasites through hemoculture of samples from chronically infected patients, and by detection of parasites in bug feces following xenodiagnosis. Parasites can be detected most sensitively in blood and tissues using molecular techniques (19) and have been documented in cardiac inflammatory tissues (20).

The pathogenesis of chronic CD is currently considered multifactorial, with as-yet poorly understood complex host-pathogen interactions. Several potential autoimmune mechanisms have been described (21), and good reviews and critiques of prevailing theories are available (22, 23). Although there is no doubt regarding the existence of an inflammatory immune response in CD, there is no conclusive experimental evidence that autoimmunity plays a significant role in its pathogenesis (7). Additional factors which may also play a role in chronic CD are microvascular disturbances and neurogenic lesions producing dysautonomy (24).

Overall, the prevailing evidence indicates that parasite persistence is fundamental for triggering and sustaining pathogenic processes (25).

WHAT IS CONSIDERED EFFICACY: A LOWER PARASITE BURDEN OR PARASITE CLEARANCE?

Although the treatment goal for infectious diseases is or should be pathogen elimination, there are other equally important therapeutic outcomes to be considered (26). Control and reduction of the pathogen burden are well-recognized strategies for some infections, such as AIDS, which is now a classic example of a lethal infection which can convert into a chronically controlled disease with the administration of appropriate treatment.

Numerous studies in animal models and humans have reported the efficacy of parasitic treatment in both the acute and chronic phase of CD (8, 9, 27, 28), with two randomized studies having demonstrated the efficacy of benznidazole treatment in children (29, 30). Furthermore, other experimental studies have demonstrated a strong treatment impact on many immune response parameters, and these findings are consistent with parasite elimination or reduction (31, 32). One previous report and several subsequent nonrandomized studies have shown improved clinical and serological evolution for treatment with benznidazole compared with the same parameters in untreated chronic patients (26, 33–37). Numerous subsequent studies and evidence supporting etiologic treatment of chronic CD are summarized elsewhere (27), while Table 1 summarizes the results of etiologic treatment in chronic patients from four nonrandomized studies (38). These latter studies demonstrate better clinical evolution in antiparasite-treated patients. An association between clinical evolution and negative seroconversion has also been analyzed in these previous studies, as in a recent publication that reported 107 chronic adult patients with cure criteria (39).

TABLE 1.

Results of nonrandomized studies with etiological treatment for patients with chronic Chagas disease, showing the relationship between clinical and serological evolutiona

| 1st author, yr (reference) | No. of patients: |

No. of patients (treated/not treated) that had: |

% of patients: |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treated | Not treated | EKG changes | Progression of cardiomyopathy | With reduction of risk progression | Negative for seroconversion |

||

| Treated | Not treated | ||||||

| Viotti, 1994 (33) | 131 | 70 | 0/4 | 2/17 | 88 | 19 | 6 |

| Gallerano, 2000 (35) | 535 | 668 | 14/34 | 4/18 | 78 | 5 | Data not available |

| Viotti, 2006 (37) | 283 | 283 | 5/16 | 4/14 | 71 | 15 | 6 |

| Fabbro De Suasnábar, 2000 (34) | 54 | 57 | 4/16 | 75 | 37 | Data not available | |

| Avg | 6/17 | 3/16 | 78 | 19 | 6 | ||

Treatment was with benznidazole except for reference 35, which reports on 309 patients treated with alopurinol, 130 treated with benznidazole, and 96 treated with nifurtimox.

Two randomized trials are in the process of comparing benznidazole to placebo in chronic patients. The first, including patients with or without mild heart disease, conducted in Argentina (TRAENA) and terminated in 2012, is currently being analyzed (40). The other is a multicenter study (BENEFIT) that should be completed by 2014 (41) and will provide evidence regarding the evolution of advanced or mild heart disease in chronic patients treated with antiparasitic drugs. The evolution of individuals with irreversible myocardial damage and, hence, at the clinical endpoint for trial evaluation may not be the same as for those who have not yet developed cardiomyopathy when they are each given antiparasitic treatment.

TREATMENT MONITORING

Antiparasitic treatment efficacy in Chagas disease can only be measured currently using anti-T. cruzi antibody titers and/or by parasite detection in blood. A therapeutic failure is defined by the persistence of the parasite, detected using different methods, such as PCR, while treatment success would be measured by the absence or reduction of antibody titers. However, a reduction in T. cruzi-specific antibody titers often takes many years, rendering measurement of treatment success insensitive and lengthy.

A long-term follow-up study using qualitative PCR before and after treatment with benznidazole, conducted in a country where CD is not endemic (42), demonstrated two key findings. Sixty-eight percent of adults with chronic Chagas disease were PCR positive prior to treatment, and of these, 100% converted to PCR negative immediately after treatment. Additionally, sustained PCR-negative results were observed in 90% of treated patients after 1 year posttreatment. Standardized qualitative PCR for the assessment of the impact of parasitic load on the overall treatment response is now available (43) and is being used in ongoing preclinical and clinical studies. These studies will clarify the value of quantitative and qualitative T. cruzi DNA measurements for monitoring therapeutic response and their association with clinical outcomes (40, 41).

Changes in various biochemical (44) and nonconventional serological and immune parameters detected shortly after benznidazole treatment may also be used for evaluating therapeutic efficacy. Following benznidazole treatment, there is a reduction of several markers, such as (i) anti-T cruzi gamma interferon (IFN-γ)-producing cells (45), (ii) T. cruzi antigen-specific antibody titers detected using nonconventional serology (multiplex) (26), and (iii) seroreactivity against specific recombinant antigens (complement regulatory protein, recombinant trans-sialidase, or kinetoplastid antigen) (46, 47).

The tools available to assess treatment impact in adult chronic patients, although not always accessible in the medical practice, can be summarized as follows.

Clinical stability, which has low sensitivity but high significance, should be evaluated using clinical signs and symptoms and complementary methods like EKG and echocardiogram and should always accompany the other markers for treatment efficacy.

Seroconversion using conventional serology is often long-term or incomplete, although it continues to be a standard for follow-up.

Changes in specific anti-T. cruzi T cell responses and IFN-γ production after treatment may correlate with the immune status prior to treatment and with the efficacy of treatment.

ADVERSE EFFECTS OF ANTIPARASITIC TREATMENT

Both benznidazole and nifurtimox, the only drugs currently available for treatment, can have variable adverse effects. Adults are more affected than children, and a proportion of treated individuals must discontinue treatment due to severe adverse events (adverse drug reactions [ADR]). Severe adverse events, similar to the incidence of ADR like Stevens-Johnson syndrome for other drugs, occur in an estimated one in 3,000 treated patients (48). Using a rabbit model, a high dose of benznidazole can provoke an increased risk of lymphoma. However, in humans and with the doses used for Chagas treatment, no such risk has been detected in adult cohorts with long-term follow-up (49).

Strict supervision of patients is required to manage ADR with the aforementioned drugs. The risk of adverse effects and lack of experience in ADR prevention and management, especially in adults, often affects physician compliance for treatment (physician opposition). The development of more-effective and safe drugs is a clear target for improved patient outcome and for clinical management. Fortunately, the currently available drugs can be used in all T. cruzi-infected adults at least until 50 years of age with careful follow-up by attending clinical staff.

CONCLUSIONS

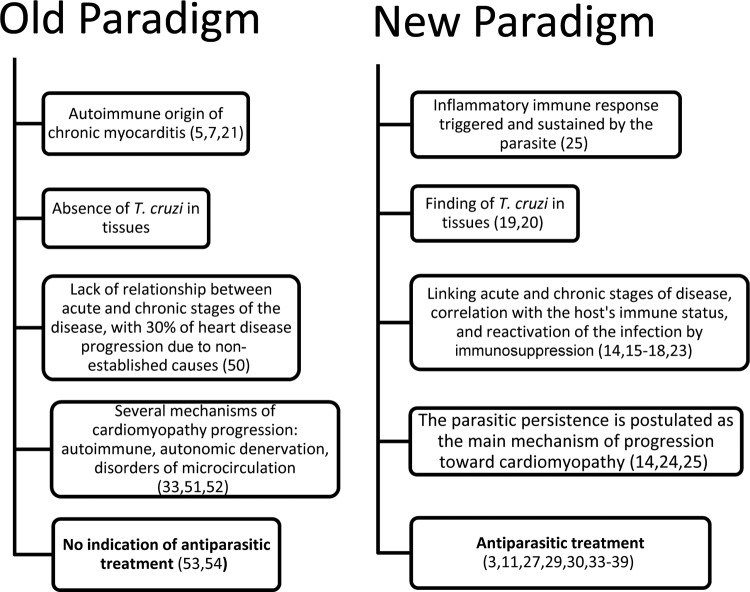

Chagas is a major neglected disease. For years, the hypothesis that chronic Chagas disease has an autoimmune origin has held back basic research and the development of more effective antiparasitic drugs and, more importantly, has led to the failure to treat most chronic adult patients. The lack of recognition of the important role of parasite persistence for the development of lesions and clinical presentations is only one of the current barriers to more effective clinical management of CD. From an integrated perspective, appropriate follow-up care for chronic patients and the development of clinical trials for new drug candidates will require appropriate early follow-up and surrogate markers for cure. The evidence-based paradigm shift (Fig. 1) that supports etiological treatment of chronic patients will require the development of novel marker tools. Whereas there has been clear recognition of the shift in the treatment paradigm by academia for several years, public health and clinical care communities have lagged in recognizing and adopting this evidence. The greatest challenge now is how to change the mindset and habits of health professionals who are biased by the old paradigm.

FIG 1.

Comparison of concepts belonging to the old and the new paradigms for chronic Chagas disease. Relevant references are given in parentheses.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We declare that we have no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 18 November 2013

The views expressed in this Commentary do not necessarily reflect the views of the journal or of ASM.

REFERENCES

- 1.Organización Panamericana de la Salud 2006. Estimación cuantitativa de la Enfermedad de Chagas en las Américas, OPS/HDM/CD/425. Organización Panamericana de la Salud, Montevideo, Uruguay [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gascon J, Bern C, Pinazo MJ. 2010. Chagas Disease in Spain, the United States and other non-endemic countries. Acta Trop. 115:22–27. 10.1016/j.actatropica.2009.07.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.WHO 2002. Control of Chagas disease, aetiological treatment. Technical Report Series no. 905. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland: [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brener Z. 1984. Recent advances in the chemotherapy of Chagas' disease. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 79:149–155. 10.1590/S0074-02761984000500026 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cunha-Neto E, Teixeira PC, Nogueira LG, Kalil J. 2011. Autoimmunity. Adv. Parasitol. 76:129–152. 10.1016/B978-0-12-385895-5.00006-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gutierrez FR, Guedes PM, Gazzinelli RT, Silva JS. 2009. The role of parasite persistence in pathogenesis of Chagas heart disease. Parasite Immunol. 31:673–685. 10.1111/j.1365-3024.2009.01108.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kierszenbaum F. 2005. Where do we stand on the autoimmunity hypothesis of Chagas disease? Trends Parasitol. 21:513–516. 10.1016/j.pt.2005.08.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hyland KV, Leon JS, Daniels MD, Giafis N, Woods LM, Bahk TJ, Wang K, Engman DM. 2007. Modulation of autoimmunity by treatment of an infectious disease. Infect. Immun. 75:3641–3650. 10.1128/IAI.00423-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garcia S, Ramos CO, Senra JFV, Vilas-Boas F, Rodrigues MM, Campos-de-Carvalho AC, Ribeiro-Dos-Santos R, Soares MB. 2005. Treatment with benznidazole during the chronic phase of experimental Chagas' disease decreases cardiac alterations. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49:1521–1528. 10.1128/AAC.49.4.1521-1528.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Oliveira W., Jr 2006. Depressao e qualidade de vida no paciente chagasico. Rev. Soc. Bras. Med. Trop. 39(Suppl 3):130–132 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gascón J, Albajar P, Cañas E, Flores M, Gómez i Prat J, Herrera RN, Lafuente CA, Luciardi HL, Moncayo A, Molina L, Muñoz J, Puente S, Sanz G, Treviño B, Sergio-Salles X. 2007. Diagnóstico, manejo y tratamiento de la cardiopatía chagásica crónica en áreas donde la infección por Trypanosoma cruzi no es endémica. Rev. Esp. Cardiol. 60:285–293. 10.1157/13100280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bern C, Montgomery SP, Herwaldt BL, Rassi A, Jr, Marin-Neto JA, Dantas RO, Maguire JH, Acquatella H, Morillo C, Kirchhoff LV, Gilman RH, Reyes PA, Salvatella R, Moore AC. 2007. Evaluation and treatment of Chagas disease in the United States: a systematic review. JAMA 298:2171–2181. 10.1001/jama.298.18.2171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Viotti R, Vigliano CA, Alvarez MG, Lococo BE, Petti MA, Bertocchi GL, Armenti AH. 2009. The impact of socioeconomic conditions on chronic Chagas disease progression. Rev. Esp. Cardio. 62:1224–1232. 10.1016/S0300-8932(09)73074-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Higuchi ML, Benvenuti LA, Reis MM, Metzger M. 2003. Pathophysiology of the heart in Chagas' disease: current status and new developments. Cardiovasc. Res. 60:96–107. 10.1016/S0008-6363(03)00361-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Muñoz J, Coll O, Juncosa T, Vergés M, del Pino M, Fumado V, Bosch J, Posada EJ, Hernandez S, Fisa R, Boguña JM, Gállego M, Sanz S, Portús M, Gascón J. 2009. Prevalence and vertical transmission of Trypanosoma cruzi infection among pregnant Latin American women attending two maternity clinics in Barcelona, Spain. Clin. Infect. Dis. 48:1736–1740. 10.1086/599223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hermann E, Truyens C, Alonso-Vega C, Rodriguez P, Berthe A, Torrico F, Carlier Y. 2004. Congenital transmission of Trypanosoma cruzi is associated with maternal enhanced parasitemia and decreased production of interferon-gamma in response to parasite antigens. J. Infect. Dis. 189:1274–1281. 10.1086/382511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schijman A, Vigliano C, Burgos J, Favaloro R, Perrone S, Laguens R, Levin MJ. 2000. Early diagnosis of recurrence of Trypanosoma cruzi infection by polymerase chain reaction after heart transplantation of a chronic Chagas heart disease patient. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 19:1114–1117. 10.1016/S1053-2498(00)00168-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rivera J, Hillis LD, Levine BD. 2004. Reactivation of cardiac Chagas disease in acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Am. J. Cardiol. 94:1102–1103. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2004.06.081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jones EM, Colley DG, Tostes S, Lopes ER, Vnencak-Jones CL, McCurley TL. 1993. Amplification of a Trypanosoma cruzi DNA sequence from inflammatory lesions in human chagasic cardiomyopathy. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 48:348–357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schijman AG, Vigliano CA, Viotti RJ, Burgos JM, Brandariz S, Lococo BE, Leze MI, Armenti HA, Levin MJ. 2004. Trypanosoma cruzi DNA in cardiac lesions of Argentinean patients with end-stage chronic Chagas heart disease. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 70:210–220 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kierszenbaum F. 1999. Chagas' disease and the autoimmunity hypothesis. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 12:210–223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bonney KM, Engman DM. 2008. Chagas heart disease pathogenesis: one mechanism or many? Curr. Mol. Med. 8:510–518. 10.2174/156652408785748004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Higuchi ML. 1997. Chronic chagasic cardiopathy: the product of a turbulent host-parasite relationship. Rev. Inst. Med. Trop. Sao Paulo 39:53–60. 10.1590/S0036-46651997000100012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marin-Neto JA, Cunha-Neto E, Maciel BC, Simões MV. 2007. Pathogenesis of chronic Chagas heart disease. Circulation 115:1109–1123. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.624296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang L, Tarleton RL. 1999. Parasite persistence correlates with disease severity and localization in chronic Chagas' disease. J. Infect. Dis. 180:480–486. 10.1086/314889 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Viotti R, Vigliano C, Alvarez MG, Lococo B, Petti M, Bertocchi G, Armenti A, De Rissio AM, Cooley G, Tarleton R, Laucella S. 2011. Impact of aetiological treatment on conventional and multiplex serology in chronic Chagas disease. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 5:e1314. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Viotti R, Vigliano C. 2007. Etiological treatment of chronic Chagas disease: neglected evidence by evidence-base medicine. Expert Rev. Anti Infect. Ther. 5:717–726. 10.1586/14787210.5.4.717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Andrade SG, Stocker-Guerret S, Pimentel AS, Grimaud JA. 1991. Reversibility of cardiac fibrosis in mice chronically infected with T. cruzi, under specific chemotherapy. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 86:187–200. 10.1590/S0074-02761991000200008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sosa Estani S, Segura EL, Ruiz AM, Velazquez E, Porcel BM, Yampotis C. 1998. Efficacy of chemotherapy with benznidazole in children in the indeterminate phase of Chagas' disease. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 59:526–529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.de Andrade AL, Zicker F, de Oliveira RM, Almeida Silva S, Luquetti A, Travassos LR, Almeida IC, de Andrade SS, de Andrade JG, Martelli CM. 1996. Randomised trial of efficacy of benznidazole in treatment of early Trypanosoma cruzi infection. Lancet 348:1407–1413. 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)04128-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bustamante JM, Bixby LM, Tarleton RL. 2008. Drug-induced cure drives conversion to a stable and protective CD8+ T central memory response in chronic Chagas disease. Nat. Med. 14:542–550. 10.1038/nm1744 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fernández MC, González Cappa SM, Solana ME. 2010. Trypanosoma cruzi: immunological predictors of benznidazole efficacy during experimental infection. Exp. Parasitol. 124:172–180. 10.1016/j.exppara.2009.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Viotti R, Vigliano C, Armenti H, Segura E. 1994. Treatment of chronic Chagas' disease with benznidazole: clinical and serologic evolution of patients with long-term follow-up. Am. Heart J. 127:151–162. 10.1016/0002-8703(94)90521-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fabbro De Suasnabar D, Arias E, Streiger M, Piacenza M, Ingaramo M, Del Barco M, Amicone N. 2000. Evolutive behavior towards cardiomyopathy of treated (nifurtimox or benznidazole) and untreated chronic chagasic patients. Rev. Inst. Med. Trop. Sao Paulo 42:99–109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gallerano RR, Sosa RR. 2000. Interventional study in the natural evolution of Chagas disease. Evaluation of specific antiparasitic treatment. Retrospective-prospective study of antiparasitic therapy. Rev. Fac. Cien. Med. Univ. Nac. Cordoba 57:135–162 (In Spanish.) 10.1590/S0036-46652000000200007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cancado JR. 2002. Long term evaluation of etiological treatment of Chagas disease with benznidazole. Rev. Inst. Med. Trop. Sao Paulo 44:29–37. 10.1590/S0036-46652002000100006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Viotti R, Vigliano C, Lococo B, Bertocchi G, Petti M, Alvarez MG, Postan M, Armenti A. 2006. Long-term cardiac outcomes of treating chronic Chagas disease with benznidazole versus no treatment. A nonrandomized trial. Ann. Intern. Med. 144:724–734. 10.7326/0003-4819-144-10-200605160-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sosa-Estani S, Viotti R, Segura E. 2009. Therapy, diagnosis and prognosis of chronic Chagas disease: insight gained in Argentina. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 104:167–180. 10.1590/S0074-02762009000900023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bertocchi G, Vigliano C, Lococo B, Petti M, Viotti R. 2013. Clinical characteristics and outcome of 107 adult patients with chronic Chagas disease and parasitological cure criteria. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 107:372–376. 10.1093/trstmh/trt029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Riarte A, Prado N, Luna C. 2005. Tratamiento etiológico con benznidazol (BZ) en pacientes adultos en diferentes estadios de la enfermedad de Chagas crónica. Un ensayo clínico aleatorizado (ECA), p 30–31 Abstr. VII Congreso Argentino de Protozoología y Enfermedades Parasitarias. Sociedad Argentina de Parasitología (SAP), Mendoza, Argentina [Google Scholar]

- 41.Marin-Neto JA, Rassi A, Jr, Morillo CA, Avezum A, Connolly SJ, Sosa-Estani S, Rosas F, Yusuf S, BENEFIT Investigators 2008. Rationale and design of a randomized placebo-controlled trial assessing the effects of etiologic treatment in Chagas' cardiomyopathy: the BENznidazole Evaluation For Interrupting Trypanosomiasis (BENEFIT). Am. Heart. J. 156:37–43. 10.1016/j.ahj.2008.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Murcia L, Carrilero B, Muñoz MJ, Iborra MA, Segovia M. 2010. Usefulness of PCR for monitoring benznidazole response in patients with chronic Chagas' disease: a prospective study in a non-disease-endemic country. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 65:1759–1764. 10.1093/jac/dkq201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schijman AG, Bisio M, Orellana L, Sued M, Duffy T, Mejia Jaramillo AM, Cura C, Auter F, Veron V, Qvarnstrom Y, Deborggraeve S, Hijar G, Zulantay I, Lucero RH, Velazquez E, Tellez T, Sanchez Leon Z, Galvão L, Nolder D, Monje Rumi M, Levi JE, Ramirez JD, Zorrilla P, Flores M, Jercic MI, Crisante G, Añez N, De Castro AM, Gonzalez CI, Acosta Viana K, Yachelini P, Torrico F, Robello C, Diosque P, Triana Chavez O, Aznar C, Russomando G, Büscher P, Assal A, Guhl F, Sosa Estani S, DaSilva A, Britto C, Luquetti A, Ladzins J. 2011. International study to evaluate PCR methods for detection of Trypanosoma cruzi DNA in blood samples from Chagas disease patients. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 5:e931. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000931 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pinazo MJ, Tàssies D, Muñoz J, Fisa R, Posada Ede J, Monteagudo J, Ayala E, Gállego M, Reverter JC, Gascon J. 2011. Hypercoagulability biomarkers in Trypanosoma cruzi-infected patients. Thromb. Haemost. 106:617–623. 10.1160/TH11-04-0251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Laucella SA, Mazliah DP, Bertocchi G, Alvarez MG, Cooley G, Viotti R, Albareda MC, Lococo B, Postan M, Armenti A, Tarleton RL. 2009. Changes in Trypanosoma cruzi-specific immune responses after treatment: surrogate markers of treatment efficacy. Clin. Infect. Dis. 49:1675–1684. 10.1086/648072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Meira WS, Galvão LM, Gontijo ED, Machado-Coelho GL, Norris KA, Chiari E. 2004. Use of the Trypanosoma cruzi recombinant complement regulatory protein to evaluate therapeutic efficacy following treatment of chronic chagasic patients. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:707–712. 10.1128/JCM.42.2.707-712.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fernandez-Villegas A, Pinazo MJ, Marañón C, Thomas MC, Posada E, Carrilero B, Segovia M, Gascon J, López MC. 2011. Short-term follow-up of chagasic patients after benznidazole treatment using multiple serological markers. BMC Infect. Dis. 11:206. 10.1186/1471-2334-11-206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yun O, Lima MA, Ellman T, Chambi W, Castillo S, Flevaud L, Roddy P, Parreño F, Albajar Viñas P, Palma PP. 2009. Feasibility, drug safety, and effectiveness of etiological treatment programs for Chagas disease in Honduras, Guatemala, and Bolivia: 10-year experience of Médecins Sans Frontières. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 3:e488. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Viotti R, Vigliano C, Lococo B, Alvarez MG, Petti M, Bertocchi G, Armenti A. 2009. The side effects of benznidazole as treatment in chronic Chagas disease: fears and realities. Expert Rev. Anti Infect. Ther. 7:157–163. 10.1586/14787210.7.2.157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Andrade ZA. 1999. Immunopathology of Chagas disease. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 94:71–80. 10.1590/S0074-02761999000700007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.da Cunha AB. 2003. Chagas' disease and the involvement of the autonomic nervous system. Rev. Port. Cardiol. 22:813–824 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rossi MA, Tanowitz HB, Malvestio LM, Celes MR, Campos EC, Blefari V, Prado CM. 2010. Coronary microvascular disease in chronic Chagas cardiomyopathy including an overview on history, pathology, and other proposed pathogenic mechanisms. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 4:e674. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Resolución de la Secretaría de Programas de Salud Ministerio de Salud y Acción Social de la Nación 1983. Normas para atención médica del infectado Chagásico. Norma no. 28/99. Ministerio de Salud y Acción Social y COFESA, Buenos Aires, Argentina [Google Scholar]

- 54.The National Health Foundation of Brazil 1997. Etiological treatment for Chagas disease. Parasitol. Today 13:127–128. 10.1016/S0169-4758(97)01018-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]