Abstract

Infectious bovine keratoconjunctivitis (IBK) caused by Moraxella bovis is the most common eye disease of cattle. The pathogenesis of M. bovis requires the expression of pili that enable the organism to attach to the ocular surface and an RTX (repeats in the structural toxin) toxin (cytotoxin or hemolysin), which is cytotoxic to corneal epithelial cells. In this pilot study, ocular mucosal immune responses of steers were measured following intranasal (i.n.) vaccination with a recombinant M. bovis cytotoxin adjuvanted with polyacrylic acid. Beef steers were vaccinated with either 500 μg (n = 3) or 200 μg (n = 3) of recombinant M. bovis cytotoxin plus adjuvant. Control group steers (n = 2) were vaccinated with adjuvant alone, and all steers were given a booster on day 21. Antigen-specific tear IgA and tear IgG, tear cytotoxin-neutralizing antibody responses, and serum cytotoxin-neutralizing antibody responses were determined in samples collected prevaccination and on days 14, 28, 42, and 55. Changes in tear antigen-specific IgA levels from day 0 to days 28, 42, and 55 were significantly different between groups; however, in post hoc comparisons between individual group pairs at the tested time points, the differences were not significant. Our results suggest that i.n. vaccination of cattle with recombinant M. bovis cytotoxin adjuvanted with polyacrylic acid effects changes in ocular antigen-specific IgA concentrations. The use of intranasally administered recombinant M. bovis cytotoxin adjuvanted with polyacrylic acid could provide an alternative to parenteral vaccination of cattle for immunoprophylaxis against IBK.

INTRODUCTION

Infectious bovine keratoconjunctivitis (IBK) (“pinkeye”) is the most common eye disease of cattle and causes corneal ulceration, corneal edema, blepharospasm, photophobia, and lacrimation in affected animals; young animals are most often affected. The disease occurs most commonly in cattle populations during summer periods in association with risk factors such as UV radiation, dust, plant awns, and flies. In severe cases, rupture of the cornea results in permanent blindness. Along with economic losses associated with treatment and prevention of IBK, there are individual animal costs associated with reduced animal well-being, comfort, and welfare. The etiologic agent of IBK has long been considered to be Moraxella bovis (1). In 2007, another species, Moraxella bovoculi, was reported that had been isolated from calves with IBK in northern California (2). Challenge inoculation of calves with M. bovoculi has not supported a direct causal role for M. bovoculi in corneal ulceration associated with IBK (3), and at this time, M. bovis remains the only organism for which Koch's postulates have been established with respect to IBK (1).

The pathogenesis of M. bovis requires the expression of pilin for attachment to the corneal surface (4–6) and cytotoxin (hemolysin or cytolysin) that mediates damage to corneal epithelium, leading to ulceration (7–9). Pilus-based vaccines reduce the incidence and the severity of IBK (10–14); however, the presence of multiple pilus serogroups (15) coupled with the potential for pilin gene inversions (16) increases antigenic variability and may result in antigenic switching, allowing M. bovis to evade a host immune response in animals vaccinated with pili (12). In contrast to pilus antigens, the M. bovis cytotoxin (MbxA) is more highly conserved among isolates (17). Cattle with IBK develop a systemic immune response to cytotoxin (18–21), and antihemolysin antibodies to one strain of M. bovis were shown to neutralize hemolysins from different strains of M. bovis (20). Calves vaccinated with a partially purified cytotoxin were protected against IBK following challenge with a heterologous M. bovis strain (18), and protection against IBK was observed in calves vaccinated with a partially purified native M. bovis cytotoxin vaccine (22).

The efficacy of a subcutaneously administered recombinant M. bovis cytotoxin subunit vaccine against naturally occurring IBK was previously evaluated (23). While significantly reduced cumulative proportions of IBK-affected calves were found in vaccinates compared to control group calves during certain weeks of that trial, significant reductions in vaccinates were not maintained over the 20-week observation period spanning a typical pinkeye summer season. In subsequent studies to further refine the recombinant cytotoxin vaccine, additional antigens were added, including conserved M. bovis pilin fragments (24) and recombinant M. bovoculi cytotoxin (25).

Most vaccine studies to prevent IBK have evaluated occurrences of IBK among vaccinates and controls that received parenterally administered vaccines. Given the mucosal localization of IBK, it is rational to consider delivery of an M. bovis vaccine by a mucosal route. To date, 4 studies have examined mucosal vaccination against IBK. Two of these studies evaluated an M. bovis bacterin administered by aerosol (26, 27), one evaluated a native M. bovis pilus antigen administered by the intranasal (i.n.) route (28), and one evaluated an M. bovis bacterin administered by the intraocular route (29). To the author's knowledge, no published studies have evaluated ocular and systemic immune responses of cattle following i.n. vaccination with recombinant M. bovis cytotoxin. The following pilot study was done to determine whether i.n. administration of a recombinant M. bovis cytotoxin vaccine adjuvanted with a mucoadhesive polymer (polyacrylic acid) could elicit ocular and systemic anticytotoxin antibody responses in beef steers.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals.

The experimental procedures for this study were approved by the University of California Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (protocol number 16585). Steers used for this study were maintained on a feedlot finishing ration throughout the study period at the University of California, Davis, Department of Animal Science campus feedlot. The study animals included 8 Angus and Angus-Hereford crossbred steers that were 336 to 380 days old and weighed 380 to 539 kg. By the day of enrollment (day 0), all steers had received both primary and booster vaccinations against respiratory viral pathogens (infectious bovine rhinotracheitis-parainfluenza 3-respiratory syncytial virus) (Inforce 3 [intranasal]; Zoetis, NJ), Clostridium spp. and Histophilus somni (Ultrabac 7/Somubac; Zoetis, NJ), and Mannheimia haemolytica (One Shot; Zoetis, NJ) and were dewormed with doramectin (Dectomax Pour-On; Zoetis, NJ). All steers had received oral selenium bolus supplementation as calves prior to arrival at the feedlot (Se 365 bolus selenium supplement; Pacific Trace Minerals, Inc., CA). Prior to the day of enrollment, steers were restrained in a hydraulic squeeze chute, and their eyes were examined; all enrolled steers were determined to have 2 clear corneas without evidence of corneal opacification suggestive of previous IBK. The 55-day trial began on 28 September 2011.

Antigen preparation.

Details regarding the molecular cloning and expression of the recombinant carboxy terminus (amino acids 590 through 927) of M. bovis cytotoxin (MbxA) as inclusion bodies in Escherichia coli have been previously described (23). Expressed inclusion bodies were solubilized in buffer containing 4 M urea, 0.25% Triton X-100, 5 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), and 1 mM EDTA and then chromatographed (HiLoad 16/60 Superdex 200 prep-grade column; Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Inc., NJ) in buffer containing 8 M urea, 200 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, and 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7). Peak fractions were identified by SDS-PAGE and pooled, and the recombinant protein was dialyzed against water at 4°C (Slide-A-Lyzer Dialysis Cassette [extra strength] 10,000 molecular-weight cutoff [MWCO]; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., IL) and then harvested. During dialysis, the recombinant protein precipitated; the final recombinant protein was quantitated (BCA kit; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., IL) prior to vaccine formulation.

Vaccine formulation.

The adjuvant (Carbigen; MVP Technologies, NE) was added to the precipitated antigen to 9% vol/vol, the vaccine was mixed vigorously with shaking for 1 min at room temperature, and the final pH was adjusted to approximately 7 (pH 5–10 strips; EMD Chemicals, Inc., NJ) with 10 N NaOH. Following overnight storage at 4°C, vaccines were warmed to room temperature and the pH was readjusted to 7 if necessary. To reduce viscosity of the final vaccine, 9% NaCl was added to achieve a final salt concentration of approximately 0.1%. At this concentration, the final vaccine could be easily expelled with a 3-ml syringe attached to a 14-cm catheter (Sovereign 3[1/2] Fr Tom Cat catheter; Tyco Healthcare Group LP, MA). Vaccines were formulated to deliver 500 μg or 200 μg in a 2-ml volume. The control vaccine consisted of sterile water to which adjuvant was added as described above.

Vaccination and sample collection.

The order in which the vaccines were administered to steers as they presented through the cattle chute on the day of vaccination (day 0) was predetermined by selecting each group assignment (3 for each of the 200-μg and 500-μg dose groups) and 2 controls from a hat without replacement. On day 0, the steers were administered the 2-ml vaccine intranasally, 1 ml per nostril, with the heads restrained with nylon halters in an elevated position; this head position was maintained for approximately 1 to 2 min following administration to help ensure retention of the vaccine in the nasal cavity. Booster vaccinations were administered similarly on day 21. Steers were housed in separate study groups throughout the study.

Serum and tear samples were collected prior to vaccination on day 0 and on days 14, 28, 42, and 55. For sera, whole blood (10 ml) was collected by coccygeal venipuncture into serum separator tubes with no additive (Tyco Healthcare Group LP, Mansfield, MA), allowed to clot, and then centrifuged (2,000 × g) for 20 min, and then serum was harvested. Tears were collected from both eyes of each steer by placement of a cotton dental roll (Patterson Dental Supply, Inc., St. Paul, MN) under the lower eyelid until the rolls were saturated. Once removed, rolls were processed and tear fluids were collected as previously described (23). Tears collected from both eyes were pooled. Sera and tears were stored at −80°C until use. The total protein concentrations of collected tears were determined in triplicate (Pierce BCA protein Assay kit; Pierce Biotechnology, IL).

Tear and serum hemolysis neutralization assays.

A diafiltered retentate (DR) containing native M. bovis cytotoxin for use in tear and serum hemolysin neutralization assays was prepared as previously described (30), except that M. bovis was propagated in heart infusion broth (Bacto heart infusion broth; Becton, Dickinson, and Co., MD) and the ultrafiltration/diafiltration of culture supernatant was performed using 2 cross-linked cellulose membrane cartridges in parallel according to the manufacturer's directions (Vivaflow 200 protein concentrator HY [10,000 MWCO]; Sartorius Stedim North America, Inc., NY). The final diafiltered retentate containing native M. bovis cytotoxin was stored at −80°C until use.

Prior to use in hemolysis neutralization assays, tear and serum samples were heat inactivated at 56°C for 1 h. Neutralization assays were performed in 96-well cell culture plates (Nunclon F Delta Surface; Nunc A/S, Roskilde, Denmark). For serum neutralization assays, serial 2-fold dilutions of serum were made in Tris-buffered saline (TBS) CaCl2 buffer (50 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, and 1.5 mM CaCl2 [pH 7.4]); serum samples were assayed in duplicate. An equal volume of 1:32 diluted DR containing native M. bovis cytotoxin in chilled (4°C) TBS CaCl2 buffer was added to the diluted serum and the plates were incubated on a rocker for 1 h at 4°C. Next, an equal volume of a 1% suspension of washed packed bovine red blood cells (defibrinated bovine blood; HemoStat Laboratories, CA) in TBS CaCl2 buffer was added to the diluted serum and plates were incubated at a 45° angle in a humidified 37°C incubator for 3 h. Plates were removed from the incubator and continued to incubate overnight at a 45° angle at room temperature to allow erythrocytes to fully settle. Following overnight incubation, plates were laid flat and individual wells were scored visually for the presence of hemolysis. The final serum cytotoxin-neutralizing antibody titer was defined as the last dilution in which no hemolysis was observed. The geometric mean of 2 dilution endpoints was used as the final serum titer.

Tear neutralization assays were performed in 96-well plates in triplicate as described above for serum neutralization assays, except that the DR containing native M. bovis cytotoxin was diluted 1:256 prior to adding it to the serially diluted tear samples. Also, plates were incubated flat for 2 h at 37°C after the addition of bovine erythrocytes. Following incubation, sedimented erythrocytes were gently resuspended by pipetting. Plates were then placed in a swinging bucket multiwell-plate carrier and centrifuged at 1,280 × g for 10 min at 4°C. Following centrifugation, 200 μl of supernatant from each well was transferred to a new 96-well plate, and the optical density at 455 nm (OD455) was measured in an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) plate reader (SpectraMax 250; Molecular Devices Corp., CA). The TBS CaCl2 buffer alone and TBS CaCl2 buffer with DR served as respective negative and positive (maximum lysis) controls (2 wells each) on each plate. To determine the final tear cytotoxin-neutralizing antibody titer, the percentage of maximum lysis was calculated by dividing the sample OD455 by the average of the lysis-positive control wells. The tear cytotoxin-neutralizing antibody titer was defined as the last serial dilution for which the OD455 remained at <25% of the OD455 of the mean of the 2 lysis-positive control wells. The geometric mean of 3 dilution endpoints was used as the tear titer. To account for variations in tear titers caused by various tear protein concentrations among samples, a tear-neutralizing index (NI) was calculated as the natural logarithm of the final tear titer divided by the mg of protein present in the initial 1:2 dilution of the tear neutralization assay.

Tear antigen-specific ELISA.

The concentrations of antigen-specific IgA and IgG in tears were determined by ELISA. Assays were performed in flat-well 96-well plates (Immulon 4HBX ultrahigh-binding polystyrene microtiter plates; Thermo Scientific, NY) at room temperature. Wells were coated for 1 h on a platform shaker with either 100 μl of the recombinant carboxy terminus of M. bovis cytotoxin (5 μg/ml) diluted in coating buffer (0.05 M sodium carbonate [pH 9.6]) (for antigen-specific IgA or IgG) or affinity-purified sheep anti-bovine IgA or IgG (Bethyl Laboratories, TX) diluted 1:100 in coating buffer (for the IgA or IgG standard curve). After coating, plates were washed 5 times in ELISA buffer (50 mM Tris, 0.14 M NaCl, and 0.05% Tween 20 [pH 8.0]) and 200 μl blocking buffer (ELISA buffer plus 2% fish gelatin) (teleostean gelatin; Sigma Life Science, MO) was added. The plates were incubated for 1 h and then washed 5 times and either 100 μl bovine reference serum (Bethyl Laboratories, Inc. TX) (appropriately diluted to generate a standard curve) or diluted tear samples (1:80 dilution) were added to each well. Duplicate and triplicate wells were run for each respective standard curve value and unknown tear sample. Positive-control tear IgA and tear IgG samples included on each plate were diluted tears from a study calf identified during ELISA optimization to have high antigen-specific tear IgA or IgG levels. Plates were then incubated for 1 h on a platform shaker and washed 5 times in ELISA buffer, and then 100 μl of either sheep anti-bovine IgG (1:100,000 in ELISA buffer) conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (HRP) (Bethyl Laboratories, Inc., TX) or sheep anti-bovine IgA-HRP (1:35,000 in ELISA buffer; Bethyl Laboratories, Inc., TX) was added and plates were incubated for 1 h on a platform shaker. Following incubation, plates were washed 5 times and enzyme substrate (TMB peroxidase substrate ELISA; Moss, Inc., MD) was added. Reactions were stopped with 100 μl of 0.1 N HCl and the OD at 450 nm was measured on an automated ELISA plate reader (SpectraMax 250; Molecular Devices Corp., CA). The final concentrations of antigen-specific tear IgA or IgG were determined from the slopes of the standard curves generated by use of commercial ELISA analysis software (MasterPlex ReaderFit [Version 2.0.0.68]; Hitachi Solutions America, Ltd., MiraiBio Group, CA). The calculated IgA or IgG concentrations represented the mean of triplicate samples. If the OD of a sample differed by >10% of the mean of the triplicate samples, that value was excluded from the data analysis. To correct for interplate variation in the IgA or IgG values from the positive control wells, the calculated sample IgA or IgG was corrected by the following formula: (calculated sample IgA or IgG value) × (mean of all test-plate-positive control IgA or IgG values/positive control IgA or IgG value of the test plate). To account for variations in tear IgA and tear IgG concentrations caused by various concentrations of tear protein, a tear IgA ratio and a tear IgG ratio were calculated by dividing the natural logarithm of the final calculated antigen-specific tear IgA or IgG concentration (in ng/ml) by the natural logarithm of the total tear total protein (μg/ml).

Statistical analysis.

Initial data diagnostics using the Shapiro-Wilk test revealed that the data were not normally distributed and thus nonparametric analyses were used. Analysis of variance of simple changes (for tear IgA and tear IgG ratios) and fold changes (for serum titer and tear NI) at time intervals from day 0 to day 14 (D0 to D14), D0 to D28, D0 to D42, and D0 to D55 were determined using the Friedman test. Post hoc analyses of differences between the 3 groups were determined using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test with Bonferroni adjustments for multiple comparisons and the Dunnett's multiple comparisons test for nonparametric or repeated measures of analysis of variance (ANOVA). Where applicable, a commercial statistical software program was used for the analysis (SAS version 9.3, NC). In the overall analyses, differences were considered significant at P values of <0.05. For the Bonferroni adjustments, differences were considered significant at P values of <0.0167 (0.05/3 comparisons).

RESULTS

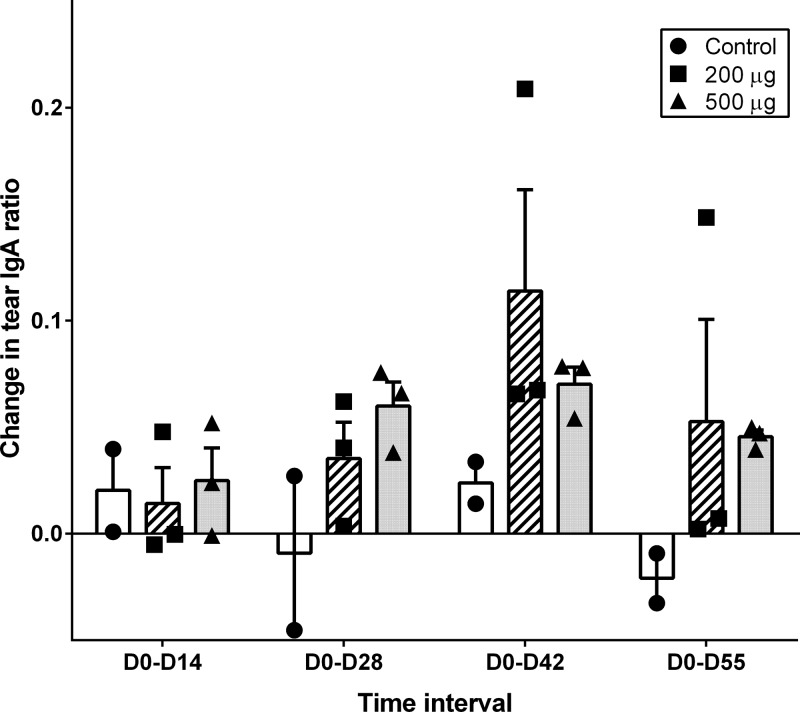

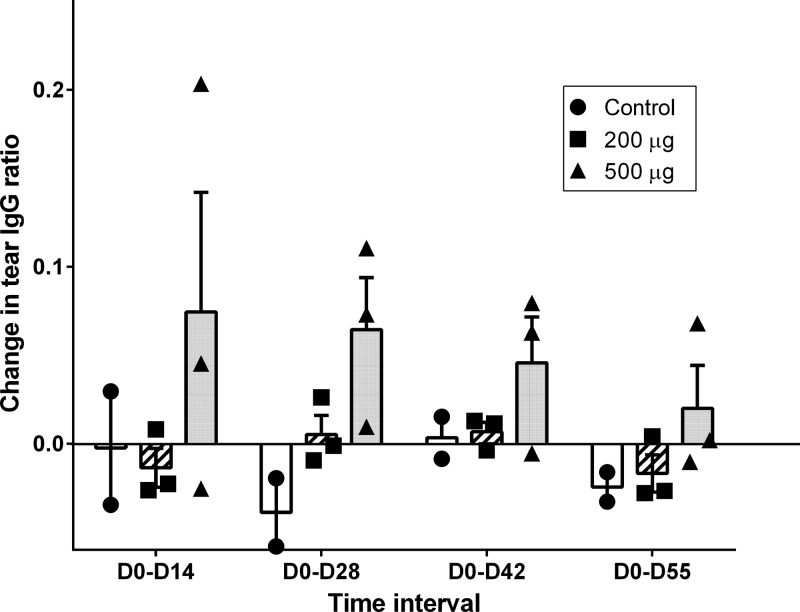

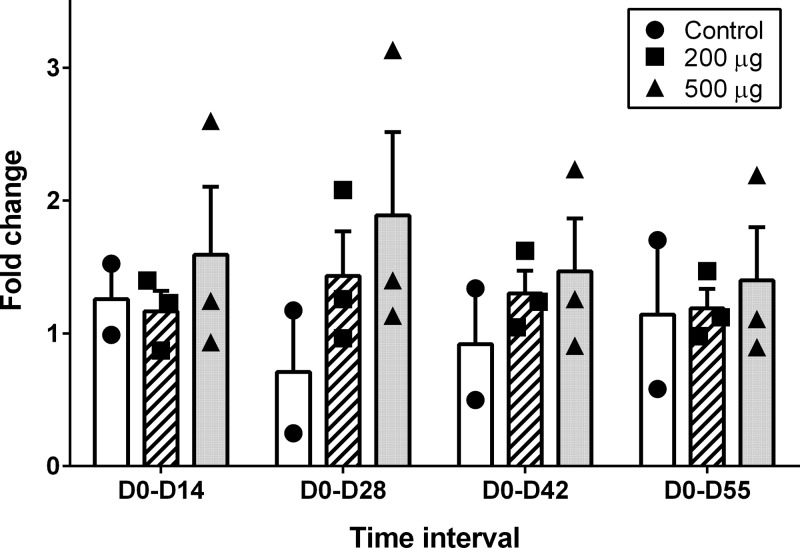

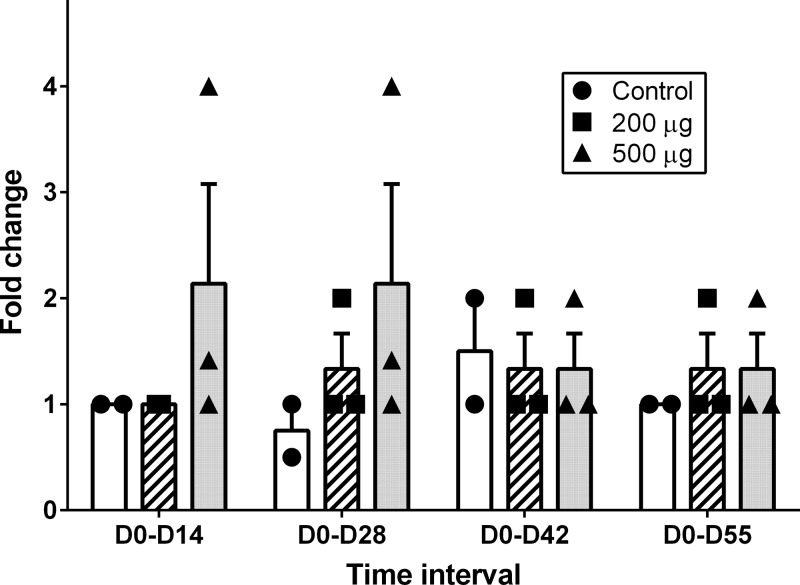

To determine if the i.n. vaccine administered to the steers in this study stimulated antibody responses in tears and serum of vaccinated steers, D0 to D14, D0 to D28, D0 to D42, and D0 to D55 changes in tear antigen-specific IgA and IgG ratios and fold changes in tear neutralization index and serum-neutralizing titers were measured. The changes in these immune response variables for the 500-μg dose, 200-μg dose, and control groups are shown in Fig. 1 (tear IgA ratio), Fig. 2 (tear IgG ratio), Fig. 3 (tear NI), and Fig. 4 (serum-neutralizing titer). The tear IgA ratios were significantly different among the 3 groups (P = 0.0104) at the 4 tested time intervals. While the mean changes in tear IgA ratios were increased relative to the control group for D0 to D28, D0 to D42, and D0 to D55, post hoc comparisons between the individual treatment group pairs were not significantly different (P > 0.017 for Bonferroni adjustments and for the Dunnett's method's calculated values being less than the critical values) at these time intervals. No significant differences were identified between groups for changes in tear IgG ratio, tear NI, or serum-neutralizing titers.

FIG 1.

Individual and group mean (+ standard error [SE]) values for changes in tear antigen-specific IgA ratios from day 0 to day 14 (D0-D14), day 0 to day 28 (D0-D28), day 0 to day 42 (D0-D42), and day 0 to day 55 (D0-D55) in steers that received primary and day-21 booster i.n. vaccination with 0 μg (control group, n = 2; black circles/white rectangles), 200 μg (n = 3; black squares/hatched rectangles), or 500 μg (n = 3; black triangles/gray rectangles) recombinant Moraxella bovis cytotoxin adjuvanted with polyacrylic acid. The tear IgA ratios were significantly different among the 3 groups (P = 0.0104) at the 4 tested time intervals. Post hoc comparisons between the individual treatment group pairs were not significantly different (P > 0.017).

FIG 2.

Individual and group mean (+ SE) values for changes in tear antigen-specific IgG ratios from day 0 to day 14 (D0-D14), day 0 to day 28 (D0-D28), day 0 to day 42 (D0-D42), and day 0 to day 55 (D0-D55) in steers that received primary and day-21 booster i.n. vaccination with 0 μg (control group, n = 2; black circles/white rectangles), 200 μg (n = 3; black squares/hatched rectangles), or 500 μg (n = 3; black triangles/gray rectangles) recombinant Moraxella bovis cytotoxin adjuvanted with polyacrylic acid.

FIG 3.

Individual and group mean (+ SE) fold changes in Moraxella bovis cytotoxin neutralization indices of tear samples from day 0 to day 14 (D0-D14), day 0 to day 28 (D0-D28), day 0 to day 42 (D0-D42), and day 0 to day 55 (D0-D55) in steers that received primary and day-21 booster i.n. vaccination with 0 μg (control group, n = 2; black circles/white rectangles), 200 μg (n = 3; black squares/hatched rectangles), or 500 μg (n = 3; black triangles/gray rectangles) recombinant M. bovis cytotoxin adjuvanted with polyacrylic acid.

FIG 4.

Individual and group mean (+ SE) fold changes in serum-neutralizing antibody titers to Moraxella bovis cytotoxin from day 0 to day 14 (D0-D14), day 0 to day 28 (D0-D28), day 0 to day 42 (D0-D42), and day 0 to day 55 (D0-D55) in steers that received primary and day-21 booster i.n. vaccination with 0 μg (control group, n = 2; black circles/white rectangles), 200 μg (n = 3; black squares/hatched rectangles), or 500 μg (n = 3; black triangles/gray rectangles) recombinant M. bovis cytotoxin adjuvanted with polyacrylic acid.

DISCUSSION

For this study, measurements of tear antigen-specific IgG ratio changes were included in order to help interpret results of the tear neutralization assay. Because tear IgG1 is selectively transferred from blood to tears in cattle (31), the ability of a collected tear sample to neutralize native M. bovis cytotoxin in the tear neutralization assay cannot entirely be attributed to the presence of antigen-specific IgA. The results showed that mean fold changes in tear neutralization indices in the vaccinates were higher than those in control group steers, especially at D0 to D28 and D0 to D55; however, the overall lack of significance in the measured differences between groups for tear IgG ratio and tear neutralization index made it impossible to clearly attribute any changes in the tear NI to either IgA or IgG.

For this study, we used as a positive control on each tear IgA/IgG ELISA plate a sample from one of the study animals that we identified during ELISA optimization to have high antigen-specific tear IgA or IgG. While it would have been more appropriate to use a control sample from a nonstudy animal, such material was unavailable. The ELISAs utilized IgA (or IgG) standard curves within each assay to determine the antigen-specific Ig concentrations, an approach that we had previously used in another study (23). In the present study, the positive control on each plate was used as an additional way to help control for interplate variation. In addition, in our analyses we evaluated changes from baseline day 0 values among the three study groups. These methods seemed adequate to overcome the limitation of not having material from a nonstudy animal as a positive control.

In one of the high-dose vaccine group steers the tear antigen-specific IgG ratio was >2× the tear IgG ratio of the other 2 steers in that group at the D0 to D14 time interval. This same calf also had a 4-fold change in the serum neutralization titer over this same time frame. We suspect that in this particular animal, the measured high change in tear IgG ratio occurred because of an increase in serum IgG titer to M. bovis cytotoxin. While the steers in this study were initially screened for the presence of normally appearing corneas and showed no evidence of clinical IBK throughout the trial, ocular cultures were not collected to determine if animals were infected with M. bovis prior to enrollment. Previously, cattle without clinical IBK were shown to develop serum hemolysin (cytotoxin)-neutralizing titers in the absence of clinical disease (20). If seroconversion without clinical evidence of IBK had occurred, it follows that for this particular study animal there was not a marked change in the tear IgA ratio from D0 to D14. Previously, it was shown that lacrimal IgA responses against M. bovis antigens were associated with more severe cases of IBK (32).

Over many years of investigations into the pathogenesis and prevention of IBK, there have been various conclusions as to the importance of local ocular immunity in determining resistance to IBK. In early studies, it was observed that lacrimal secretions of calves with more severe IBK developed increased lacrimal fluid IgA against crude M. bovis antigens and the presence of these antibodies seemed to reduce disease susceptibility following reinfection (32, 33). While authors suggested that local ocular vaccination could be beneficial (32), a subsequent investigation that evaluated immune responses in ocular fluids of subconjunctivally vaccinated versus unvaccinated calves demonstrated that ocular antibodies to M. bovis were not protective because clinical IBK developed even in the presence of high tear-hemagglutinating (HA) titers (34). An important observation in that study, however, was that the percentage of calves (both vaccinated and unvaccinated) from which M. bovis could be isolated decreased as the mean tear HA titer increased (34). Authors of a subsequent study that measured lacrimal fluid IgA and IgG using an indirect fluorescent antibody test also reported that lacrimal antibodies did not prevent IBK (35).

In later studies, however, positive correlations were reported between specific antibodies in lacrimal secretions as assessed by a passive hemagglutination test using tannic acid-treated sheep red blood cells sensitized with a whole M. bovis cell sonicate, amelioration of clinical IBK, and declining numbers of M. bovis that were isolated from conjunctival swabs of experimentally infected calves (36). When an ELISA using a whole-M. bovis cell antigen was used to measure anti-M. bovis responses in tears of calves with experimentally induced IBK, a predominant IgA response to M. bovis was detected (37). When a whole-M. bovis antigen ELISA was used to quantitate humoral IgG and lacrimal IgA in calves with experimentally induced IBK, an association between the presence of ocular IgA against M. bovis antigens and resistance to reinfection was found (38). The authors suggested that vaccination by a route that would stimulate mucosal IgA against M. bovis would be important in developing an effective M. bovis vaccine (38).

When subcutaneous versus subconjunctival routes of vaccination were evaluated in a study of a pilus-based vaccine, subconjunctival vaccinates were found to have greater resistance to challenge infection (39). In the most recent study of a subconjunctival route of vaccination with an autogenous M. bovis bacterin, no difference was found between subconjunctival versus subcutaneous vaccinates (40). In neither of these studies were lacrimal antibody responses against M. bovis antigens measured, and so it is unknown whether the subconjunctival route of injection successfully stimulated a specific ocular fluid antibody response against M. bovis antigens.

Mixed results have been reported for investigations into nonparenteral routes of vaccination of cattle against IBK. An aerosolized fimbriated M. bovis bacterin was reported to be effective at preventing naturally occurring IBK (26, 27). In those studies, ocular antibody responses against M. bovis antigens were not reported. Presumably, the vaccine which was administered with an atomizer could have exposed antigen at inductive sites on ocular, nasal, and oropharyngeal mucosal surfaces. A more recently reported investigation of ocular IgA antibody responses following i.n. vaccination with purified M. bovis pili plus various adjuvants revealed that pili adjuvanted with QuilA or Marcol Span induced significant increases in antipilus ocular IgA responses in calves receiving vaccine compared to adjuvant control calves (28). In that study, however, the antipilus ocular IgA responses did not correlate well with either protection against M. bovis infection or the development of IBK (28). Other studies previously demonstrated the success of subcutaneously administered pilus-based vaccines at protecting calves against homologous but not heterologous challenges with M. bovis of different pilus serogroups (14), and it is possible that in the study reported by Zbrun et al (28), heterologous pilus strains were circulating in the study herd, which may have contributed to the development of IBK among vaccinates despite high tear antipilus IgA concentrations. In another recent study, calves were challenged 45 days following topical ocular vaccination with a killed M. bovis bacterin alone or with recombinant human interleukin 2 and alpha interferon (29). In that study, ocular antibody responses were not reported; however, calves that received the M. bovis bacterin plus cytokines had the lowest proportion of IBK and the lowest clinical IBK scores following challenge (29).

In the present study, a variety of different factors may have contributed to suboptimal performance of the experimental M. bovis subunit vaccine, including adjuvant, antigen formulation, and method of delivery. For this study, we chose to use a polymer of acrylic acid (PAA) as the adjuvant, and while it is possible that the use of a different adjuvant may have improved our success at stimulating an ocular anticytotoxin IgA response, PAA was a logical choice because of its demonstrated adjuvant properties (41), mucoadhesive qualities, and commercial availability. The antigen used for this study precipitated during the final steps of dialysis against water and it is possible that reformulation of this antigen in a soluble form may improve its antigenicity. For this study, we delivered the vaccine through a 14-cm polypropylene catheter. Delivery of antigen to inductive lymphoid sites within the bovine nasal cavity could have been improved by use of a longer catheter capable of delivering vaccine to nasal-associated lymphoid tissues of Waldeyer's ring, including pharyngeal and tubal tonsils. Commercial i.n. vaccines that are currently marketed for use in cattle in the United States use a relatively short cannula for administration; however, these vaccines contain modified live agents that induce immunity by virtue of localized infection, a benefit that a nasally delivered recombinant protein subunit such as the antigen used in this study does not have.

In a previous study of subcutaneously administered recombinant M. bovis cytotoxin, we observed significantly higher antigen-specific IgG in sera and tears, as well as the lowest cumulative proportion of IBK, in vaccinated versus control group calves (23). In that study we also observed the largest corneal ulcers in vaccinated calves, an observation that suggested that perhaps high levels of IgG in serum/tears contributed to increased ocular pathology due to complement fixation and attraction of neutrophils and subsequent release of degradative enzymes into the corneal stroma. The possibility for immune-mediated damage in the eye associated with M. bovis infections provides a rationale for trying to augment ocular antigen-specific IgA responses by mucosal vaccination. Shallower and larger (in surface area) ulcers were demonstrated in one study of calves that were immunosuppressed by treatment with hydroxyurea versus control calves 8 days following an M. bovis challenge (42). A similar study of normal versus immunosuppressed calves with differing concentrations of anti-M. bovis IgG in ocular secretions could provide further insight into the possibility of immune-mediated ocular injury during M. bovis infection.

In summary, the results of this study demonstrated that i.n. vaccination of healthy beef cattle with the carboxy terminus of recombinant M. bovis cytotoxin adjuvanted with the mucoadhesive polymer polyacrylic acid can stimulate changes in antigen-specific ocular mucosal IgA. It is likely that the small sample size and high individual animal variation in measured immune response variables accounted for the lack of statistical significance in post hoc testing between treatment groups. While the significance of these results are limited, the use of i.n. vaccination to increase anticytotoxin-specific IgA in tear secretions of steers vaccinated with an M. bovis cytotoxin subunit antigen adjuvanted with polyacrylic acid appears promising. Further studies are under way to investigate whether refinements to this vaccine can improve ocular mucosal responses to M. bovis cytotoxin in cattle. Subsequent trials will be necessary to determine whether such responses can prevent naturally occurring IBK.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the University of California-Davis School of Veterinary Medicine Center for Food Animal Health Funds and USDA Formula Funds.

We thank David Coons, Karen Brown, Jerry Johnson, and James Moller for technical assistance.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 11 December 2013

REFERENCES

- 1.Henson JB, Grumbles LC. 1960. Infectious bovine keratoconjunctivitis. I. Etiology. Am. J. Vet. Res. 21:761–766 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Angelos JA, Spinks PQ, Ball LM, George LW. 2007. Moraxella bovoculi sp. nov., isolated from calves with infectious bovine keratoconjunctivitis. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 57:789–795. 10.1099/ijs.0.64333-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gould S, Dewell R, Tofflemire K, Whitley RD, Millman ST, Opriessnig T, Rosenbusch R, Trujillo J, O'Connor AM. 2013. Randomized blinded challenge study to assess association between Moraxella bovoculi and infectious bovine keratoconjunctivitis in dairy calves. Vet. Microbiol. 164:108–115. 10.1016/j.vetmic.2013.01.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moore LJ, Rutter JM. 1989. Attachment of Moraxella bovis to calf corneal cells and inhibition by antiserum. Aust. Vet. J. 66:39–42. 10.1111/j.1751-0813.1989.tb03012.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ruehl WW, Marrs C, Beard MK, Shokooki V, Hinojoza JR, Banks S, Bieber D, Mattick JS. 1993. Q pili enhance the attachment of Moraxella bovis to bovine corneas in vitro. Mol. Microbiol. 7:285–288. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01119.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Annuar BO, Wilcox GE. 1985. Adherence of Moraxella bovis to cell cultures of bovine origin. Res. Vet. Sci. 39:241–246 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beard MK, Moore LJ. 1994. Reproduction of bovine keratoconjunctivitis with a purified haemolytic and cytotoxic fraction of Moraxella bovis. Vet. Microbiol. 42:15–33. 10.1016/0378-1135(94)90074-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gray JT, Fedorka-Cray PJ, Rogers DG. 1995. Partial characterization of a Moraxella bovis cytolysin. Vet. Microbiol. 43:183–196. 10.1016/0378-1135(94)00084-A [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kagonyera GM, George LW, Munn R. 1989. Cytopathic effects of Moraxella bovis on cultured bovine neutrophils and corneal epithelial cells. Am. J. Vet. Res. 50:10–17 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lehr C, Jayappa HG, Goodnow RA. 1985. Serologic and protective characterization of Moraxella bovis pili. Cornell Vet. 75:484–492 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jayappa HG, Lehr C. 1986. Pathogenicity and immunogenicity of piliated and nonpiliated phases of Moraxella bovis in calves. Am. J. Vet. Res. 47:2217–2221 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lepper AW, Atwell JL, Lehrbach PR, Schwartzkoff CL, Egerton JR, Tennent JM. 1995. The protective efficacy of cloned Moraxella bovis pili in monovalent and multivalent vaccine formulations against experimentally induced infectious bovine keratoconjunctivitis (IBK). Vet. Microbiol. 45:129–138. 10.1016/0378-1135(94)00123-E [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lepper AW, Elleman TC, Hoyne PA, Lehrbach PR, Atwell JL, Schwartzkoff CL, Egerton JR, Tennent JM. 1993. A Moraxella bovis pili vaccine produced by recombinant DNA technology for the prevention of infectious bovine keratoconjunctivitis. Vet. Microbiol. 36:175–183. 10.1016/0378-1135(93)90138-W [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lepper AW. 1988. Vaccination against infectious bovine keratoconjunctivitis: protective efficacy and antibody response induced by pili of homologous and heterologous strains of Moraxella bovis. Aust. Vet. J. 65:310–316. 10.1111/j.1751-0813.1988.tb14513.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moore LJ, Lepper AW. 1991. A unified serotyping scheme for Moraxella bovis. Vet. Microbiol. 29:75–83. 10.1016/0378-1135(91)90111-R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marrs CF, Ruehl WW, Schoolnik GK, Falkow S. 1988. Pilin-gene phase variation of Moraxella bovis is caused by an inversion of the pilin genes. J. Bacteriol. 170:3032–3039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Angelos JA, Ball LM. 2007. Relatedness of cytotoxins from geographically diverse isolates of Moraxella bovis. Vet. Microbiol. 124:382–386. 10.1016/j.vetmic.2007.04.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Billson FM, Hodgson JL, Egerton JR, Lepper AW, Michalski WP, Schwartzkoff CL, Lehrbach PR, Tennent JM. 1994. A haemolytic cell-free preparation of Moraxella bovis confers protection against infectious bovine keratoconjunctivitis. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 124:69–74. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1994.tb07263.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nakazawa M, Nemoto H. 1979. Hemolytic activity of Moraxella bovis. Nippon Juigaku Zasshi 41:363–367. 10.1292/jvms1939.41.363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ostle AG, Rosenbusch RF. 1985. Immunogenicity of Moraxella bovis hemolysin. Am. J. Vet. Res. 46:1011–1014 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hoien-Dalen PS, Rosenbusch RF, Roth JA. 1990. Comparative characterization of the leukocidic and hemolytic activity of Moraxella bovis. Am. J. Vet. Res. 51:191–196 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.George LW, Borrowman AJ, Angelos JA. 2005. Effectiveness of a cytolysin-enriched vaccine for protection of cattle against infectious bovine keratoconjunctivitis. Am. J. Vet. Res. 66:136–142. 10.2460/ajvr.2005.66.136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Angelos JA, Hess JF, George LW. 2004. Prevention of naturally occurring infectious bovine keratoconjunctivitis with a recombinant Moraxella bovis cytotoxin-ISCOM matrix adjuvanted vaccine. Vaccine 23:537–545. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2004.06.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Angelos JA, Bonifacio RG, Ball LM, Hess JF. 2007. Prevention of naturally occurring infectious bovine keratoconjunctivitis with a recombinant Moraxella bovis pilin-Moraxella bovis cytotoxin-ISCOM matrix adjuvanted vaccine. Vet. Microbiol. 125:274–283. 10.1016/j.vetmic.2007.05.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Angelos JA, Gohary KG, Ball LM, Hess JF. 2012. Randomized controlled field trial to assess efficacy of a Moraxella bovis pilin-cytotoxin-Moraxella bovoculi cytotoxin subunit vaccine to prevent naturally occurring infectious bovine keratoconjunctivitis. Am. J. Vet. Res. 73:1670–1675. 10.2460/ajvr.73.10.1670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Misiura M. 1994. Estimation of fimbrial vaccine effectiveness in protection against keratoconjunctivitis infectiosa in calves considering different routes of introducing vaccine antigene. Arch. Vet. Pol. 34:177–186 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Misiura M. 1994. Keratoconjunctivitis infectiosa in calves–attempt at elimination by active immunization. Arch. Vet. Pol. 34:187–194 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zbrun MV, Zielinski GC, Piscitelli HC, Descarga C, Urbani LA, Defain Tesoriero MV, Hermida L. 2012. Evaluation of anti-Moraxella bovis pili immunoglobulin-A in tears following intranasal vaccination of cattle. Res. Vet. Sci. 93:183–189. 10.1016/j.rvsc.2011.05.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.di Girolamo FA, Sabatini DJ, Fasan RA, Echegoyen M, Vela M, Pereira CA, Maure P. 2012. Evaluation of cytokines as adjuvants of infectious bovine keratoconjunctivitis vaccines. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 145:563–566. 10.1016/j.vetimm.2011.12.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Angelos JA, Hess JF, George LW. 2001. Cloning and characterization of a Moraxella bovis cytotoxin gene. Am. J. Vet. Res. 62:1222–1228. 10.2460/ajvr.2001.62.1222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pedersen KB. 1973. The origin of immunoglobulin-G in bovine tears. Acta Pathol. Microbiol. Scand. B Microbiol. Immunol. 81:245–252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nayar PS, Saunders JR. 1975. Infectious bovine keratoconjunctivitis II. Antibodies in lacrimal secretions of cattle naturally or experimentally infected with Moraxella bovis. Can. J. Comp. Med. 39:32–40 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nayar PS, Saunders JR. 1975. Infectious bovine keratoconjunctivitis I. Experimental production. Can. J. Comp. Med. 39:22–31 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Arora AK, Killinger AH, Myers WL. 1976. Detection of Moraxella bovis antibodies in infectious bovine keratoconjunctivitis by a passive hemagglutination test. Am. J. Vet. Res. 37:1489–1492 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Killinger AH, Weisiger RM, Helper LC, Mansfield ME. 1978. Detection of Moraxella bovis antibodies in the SIgA, IgG, and IgM classes of immunoglobulin in bovine lacrimal secretions by an indirect fluorescent antibody test. Am. J. Vet. Res. 39:931–934 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Weech GM, Renshaw HW. 1983. Infectious bovine keratoconjunctivitis: bacteriologic, immunologic, and clinical responses of cattle to experimental exposure with Moraxella bovis. Comp. Immunol. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 6:81–94. 10.1016/0147-9571(83)90040-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bishop B, Schurig GG, Troutt HF. 1982. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for measurement of anti-Moraxella bovis antibodies. Am. J. Vet. Res. 43:1443–1445 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Smith PC, Greene WH, Allen JW. 1989. Antibodies related to resistance in bovine pinkeye. Calif. Vet. 46:7, 9–10, 18 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pugh GW, Jr, Kopecky KE, McDonald TJ. 1985. Infectious bovine keratoconjunctivitis: subconjunctival administration of a Moraxella bovis pilus preparation enhances immunogenicity. Am. J. Vet. Res. 46:811–815 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Davidson HJ, Stokka GL. 2003. A field trial of autogenous Moraxella bovis bacterin administered through either subcutaneous or subconjunctival injection on the development of keratoconjunctivitis in a beef herd. Can. Vet. J. 44:577–580 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hilgers LA, Ghenne L, Nicolas I, Fochesato M, Lejeune G, Boon B. 2000. Alkyl-polyacrylate esters are strong mucosal adjuvants. Vaccine 18:3319–3325. 10.1016/S0264-410X(00)00114-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kagonyera GM, George LW, Munn R. 1988. Light and electron microscopic changes in corneas of healthy and immunomodulated calves infected with Moraxella bovis. Am. J. Vet. Res. 49:386–395 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]