Abstract

The C-terminal tail of yeast plasma membrane (PM) H+-ATPase extends approximately 38 amino acids beyond the final membrane-spanning segment (TM10) of the protein and is known to be required for successful trafficking, stability, and regulation of enzyme activity. To carry out a detailed functional survey of the entire length of the tail, we generated 15 stepwise truncation mutants. Eleven of them, lacking up to 30 amino acids from the extreme terminus, were able to support cell growth, even though there were detectable changes in plasma membrane expression, protein stability, and ATPase activity. Three functionally distinct regions of the C terminus could be defined. (i) Truncations upstream of Lys889, removing more than 30 amino acid residues, yielded no viable mutants, and conditional expression of such constructs supported the conclusion that the stretch from Ala881 (at the end of TM10) to Gly888 is required for stable folding and PM targeting. (ii) The stretch between Lys889 and Lys916, a region known to be subject to kinase-mediated posttranslational modification, was shown here to be ubiquitinated in carbon-starved cells as part of cellular quality control and to be essential for normal ATPase folding and stability, as well as for autoinhibition of ATPase activity during glucose starvation. (iii) Finally, removal of even one or two residues (Glu917 and Thr918) from the extreme C terminus led to visibly reduced expression of the ATPase at the plasma membrane. Thus, the C terminus is much more than a simple appendage and profoundly influences the structure, biogenesis, and function of the yeast H+-ATPase.

INTRODUCTION

In the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Pma1 H+-ATPase pumps protons out of the cell, forming an electrochemical membrane potential that is critical for the uptake of sugars, amino acids, and other nutrients. The ATPase is a highly expressed product of the PMA1 gene, constituting more than 10% of total plasma membrane (PM) protein, and belongs to the widespread family of P-type ATPases that are found throughout animal, plant, and microbial cells (reviewed in references 1 and 2). It has a characteristic topology, with 10 membrane-spanning elements and three well-defined cytoplasmic domains; the N and C termini are also located in the cytoplasm (3). In recent years, it has served as a useful model for studies of structure-function relationships and membrane biogenesis (4–8).

Compared to P-type enzymes of animal cells, yeast Pma1 H+-ATPase has an elongated cytoplasmic tail that was found to be a key regulatory domain soon after the PMA1 gene was cloned (9). Autoinhibition of Pma1 H+-ATPase activity during glucose starvation is now thought to occur through direct interaction of the tail with other elements of the polypeptide. While no high-resolution structure is available to identify those elements directly, modeling of second-site suppressor mutants and comparison to the published structure for a related plant H+-ATPase suggest that the inhibitory tail winds around the core of the ATPase to interact with the A actuator domain (10). Mechanistically, the interaction depends on the level of kinase-mediated phosphorylation of a pair of C-terminal residues (Ser911/Thr912) (11).

Growing evidence suggests that the C-terminal tail of Pma1 H+-ATPase also plays a major role in trafficking to the cell surface and stability of the mature protein. In a previous study from our laboratory (4), removal of 38 amino acids from the distal end of the ATPase led to endoplasmic reticulum (ER) arrest of Pma1-Δ881p, followed by degradation in the proteasome. In contrast, an ATPase truncated by 18 amino acids (Pma1-Δ901p) was transported to the PM, where it retained sufficient ATPase activity to support growth despite being significantly less stable than the wild type.

The present study was undertaken to analyze structure-function relationships throughout the C-terminal tail of the Pma1 H+-ATPase in finer detail. The results, obtained using both integrative and conditional expression of truncated pma1 alleles, indicate that up to 30 amino acids can be removed from the C terminus while still allowing for measurable trafficking and function of the mutant ATPase. On the other hand, removal of the final three residues from the extreme C terminus is sufficient to significantly impact both activity and glucose-dependent regulation, while removal of the final five residues undermines protein stability. Multiple quality control (QC) mechanisms, including protein ubiquitination, are known to regulate the PM expression of truncated forms of the ATPase. Using Pma1-Δ901p as an example of a functional, export-competent mutant, we show that a fraction of the newly synthesized mutant ATPase is ubiquitinated at two specific Lys residues close to the C terminus, contributing to the instability of the truncated protein.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Yeast strains and growth conditions.

Table 1 lists the S. cerevisiae strains used in this study. Chromosomal integrations of pma1 alleles were performed using BMY58, a pma2Δ strain (Table 1). For transient expression experiments, the chromosomal copy of PMA1 in the background yeast strain [e.g., BMY40, sec6(Ts)] was placed under the control of the GAL1 promoter (Table 1). Mutant pma1 alleles controlled by either heat shock or MET3 promoters were then introduced on centromeric plasmids. Transformants were selected on 2% galactose in complete synthetic medium minus uracil (CSM-ura) and the relevant auxotrophic amino acid(s) (QBiogene, OH). To express hemagglutinin (HA)-tagged Pma1p mutant proteins, chromosomal GAL1pr-PMA1 expression was first turned off by incubating the cells for 3 h in CSM-ura containing 2% glucose instead of galactose. With the secretory pathway now purged of wild-type ATPase, expression from the HA-tagged pma1 allele was turned on by either incubation of the cells at 39°C or by switching the cells to methionine-free medium for the designated time (4). Mutant Pma1p expression was terminated either by returning cells to 23°C or by adding methionine back to the medium (30 μg/ml final concentration).

TABLE 1.

Yeast strains used in this study

| Yeast strain | Relevant genotype | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| NY13 | MATα ura3-52 | P. Novick |

| BMY58 | MATα ura3-52 pma2Δ::KANMX4 | This study |

| BMY62 | MATα ura3-52 pma2Δ::KANMX4 HA-pma1-Δ901::URA3 | This study |

| BMY66 | MATα ura3-52 pma2Δ::KANMX4 HA-pma1-Δ890::URA3 | This study |

| BMY67 | MATα ura3-52 pma2Δ::KANMX4 HA-pma1-Δ896::URA3 | This study |

| BMY70 | MATα ura3-52 pma2Δ::KANMX4 HA-PMA1::URA3 | This study |

| BMY85 | MATα ura3-52 pma2Δ::KANMX4 HA-pma1-Δ889::URA3 | This study |

| BMY90 | MATα ura3-52 pma2Δ::KANMX4 HA-pma1-Δ908::URA3 | This study |

| BMY91 | MATα ura3-52 pma2Δ::KANMX4 HA-pma1-Δ913::URA3 | This study |

| BMY112 | MATα ura3-52 pma2Δ::KANMX4 HA-pma1-Δ914::URA3 | This study |

| BMY113 | MATα ura3-52 pma2Δ::KANMX4 HA-pma1-Δ915::URA3 | This study |

| BMY97 | MATα ura3-52 pma2Δ::KANMX4 HA-pma1-Δ916::URA3 | This study |

| BMY98 | MATα ura3-52 pma2Δ::KANMX4 HA-pma1-Δ917::URA3 | This study |

| BMY99 | MATα ura3-52 pma2Δ::KANMX4 HA-pma1-Δ918::URA3 | This study |

| BMY40 | MATa trp1-289 his3Δ200 ura3-52 pma1::YIpGAL-PMA1 | Mason et al. (4) |

| BMY401 | MATa trp1-289 his3Δ200 ura3-52 pma1::YIpGAL-PMA1 YCplac22-2HSEpr-HA-PMA1 | Mason et al. (4) |

| BMY4016 | MATa trp1-289 his3Δ200 ura3-52 pma1::YIpGAL-PMA1 YCplac22-2HSEpr-HA-pma1-Δ881 | Mason et al. (4) |

| BMY4072 | MATa trp1-289 his3Δ200 ura3-52 pma1::YIpGAL-PMA1 YCplac22-2HSEpr-HA-pma1-Δ885 | This study |

| BMY4073 | MATa trp1-289 his3Δ200 ura3-52 pma1::YIpGAL-PMA1 YCplac22-2HSEpr-HA-pma1-Δ887 | This study |

| BMY4042 | MATa trp1-289 his3Δ200 ura3-52 pma1::YIpGAL-PMA1 YCplac22-2HSEpr-HA-pma1-Δ888 | This study |

| BMY4043 | MATa trp1-289 his3Δ200 ura3-52 pma1::YIpGAL-PMA1 YCplac22-2HSEpr-HA-pma1-Δ889 | This study |

| BMY4070 | MATa trp1-289 his3Δ200 ura3-52 pma1::YIpGAL-PMA1 YCplac22-2HSEpr-HA-pma1-Δ890 | This study |

| BMY4071 | MATa trp1-289 his3Δ200 ura3-52 pma1::YIpGAL-PMA1 YCplac22-2HSEpr-HA-pma1-Δ896 | This study |

| BMY4017 | MATa trp1-289 his3Δ200 ura3-52 pma1::YIpGAL-PMA1 YCplac22-2HSEpr-HA-pma1-Δ901 | Mason et al. (4) |

| BMY4040 | MATa trp1-289 his3Δ200 ura3-52 pma1::YIpGAL-PMA1 YCplac22-2HSEpr-HA-pma1-Δ908 | This study |

| BMY4041 | MATa trp1-289 his3Δ200 ura3-52 pma1::YIpGAL-PMA1 YCplac22-2HSEpr-HA-pma1-Δ913 | This study |

| BMY4047 | MATa trp1-289 his3Δ200 ura3-52 pma1::YIpGAL-PMA1 YCplac22-2HSEpr-HA-pma1-Δ914 | This study |

| BMY4048 | MATa trp1-289 his3Δ200 ura3-52 pma1::YIpGAL-PMA1 YCplac22-2HSEpr-HA-pma1-Δ915 | This study |

| BMY4044 | MATa trp1-289 his3Δ200 ura3-52 pma1::YIpGAL-PMA1 YCplac22-2HSEpr-HA-pma1-Δ916 | This study |

| BMY4045 | MATa trp1-289 his3Δ200 ura3-52 pma1::YIpGAL-PMA1 YCplac22-2HSEpr-HA-pma1-Δ917 | This study |

| BMY4046 | MATa trp1-289 his3Δ200 ura3-52 pma1::YIpGAL-PMA1 YCplac22-2HSEpr-HA-pma1-Δ918 | This study |

| BMY4051 | MATa trp1-289 his3Δ200 ura3-52 pma1::YIpGAL-PMA1 YCplac22-2HSEpr-HA-pma1-Δ901-K892/894/895R | This study |

| BMY4052 | MATa trp1-289 his3Δ200 ura3-52 pma1::YIpGAL-PMA1 YCplac22-2HSEpr-HA-pma1-Δ901-K892R | This study |

| BMY4053 | MATa trp1-289 his3Δ200 ura3-52 pma1::YIpGAL-PMA1 YCplac22-2HSEpr-HA-pma1-Δ901-K894R | This study |

| BMY4054 | MATa trp1-289 his3Δ200 ura3-52 pma1::YIpGAL-PMA1 YCplac22-2HSEpr-HA-pma1-Δ901-K895R | This study |

| TFY341 | MATa trp1-289 his3Δ200 ura3-52 sec6-4(Ts) pma1::YIpGAL-PMA1 | Ferreira et al. (15) |

| TFY341-M3WT | MATa trp1-289 his3Δ200 ura3-52 sec6-4(Ts) pma1::YIpGAL-PMA1 YCplac22-MET3pr-HA-PMA1 | This study |

| TFY341-M3901 | MATa trp1-289 his3Δ200 ura3-52 sec6-4(Ts) pma1::YIpGAL-PMA1 YCplac22-MET3pr-HA-pma1-Δ901 | This study |

Standard yeast media and genetic manipulations were as described by Sherman et al. (12). Yeast transformations were performed as described previously (13) using the alkali-cation yeast transformation kit (QBiogene, OH).

Plasmids.

For constitutive expression of pma1Δ alleles, mutant constructs were made in plasmid pBM432 (4) by replacing the 1.1-kb BamHI-MluI fragment from the PMA1 coding sequence with a corresponding fragment that incorporated a TAA stop codon at the chosen position. Linear 6-kb HindIII fragments from these constructs were then used to transform BMY58, relying on integration of linearized constructs at the chromosomal PMA1 locus by homologous recombination. Transformants were selected on CSM-glucose (CSMGlu) plates lacking uracil. Screening was performed by dot blotting total protein extracts to detect HA tag expression, followed by Western blotting and DNA sequencing to confirm expression of a truncated ATPase.

To examine conditional expression of truncated Pma1 H+-ATPases, pma1Δ alleles were introduced into plasmid pBM45, pBM49, or pBM51 using a strategy described previously (4). Plasmid YCplac22-2HSEpr-HA-PMA1-MluI was modified by inclusion of an NcoI site at the ATG start codon of the PMA1 coding sequence to give pBM45, while pBM51 was made from pBM45 by replacing the heat shock promoter with the MET3 promoter (MET3pr) (14) as a 513-bp PstI-NcoI fragment. Plasmid pBM49 had the same MET3pr-PMA1 insert as pBM51 but was made using YCplac111 as the parental vector; therefore, it carried LEU2 as the selectable auxotrophic marker.

When possible, both wild-type and mutant alleles of PMA1 used in this study were tagged with a single copy of the 9-amino-acid HA epitope (YPYDVPDYA) inserted in frame between codons 2 and 3 of the PMA1 coding sequence. The QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) was used for in vitro mutagenesis, and all mutant constructs were verified by DNA sequencing.

Immunofluorescence.

Intracellular structures containing HA-tagged ATPase were visualized by confocal microscopy as described previously (4). Cells were fixed, treated with Zymolyase T-100, permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100, and stained for immunofluorescence (15). Primary antibodies used were anti-HA.11 monoclonal 16B12 (Babco, Richmond, CA) diluted 1/150 and rabbit anti-Kar2p polyclonal antibody (provided by M. Rose) diluted 1:2,500. Goat anti-rabbit and goat anti-mouse IgGs conjugated to fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) and Texas red (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA), respectively, served as fluorescent secondary antibodies and were used at 1/100 dilutions. For double labeling experiments, both primary antibodies were present during the initial incubation and both secondary antibodies were present during the subsequent incubation. To control for spurious antibody cross-reactivity, noninduced cells were simultaneously fixed and stained with each set of antibodies. Samples were then mounted in Citifluor (Ted Pella, Redding, PA).

Cells were observed under a Zeiss L510 scanning confocal microscope using dual-channel filters for simultaneous visualization of FITC and Texas red fluorochromes. All images were taken with a 63×, 1.4-numeric-aperture Plan-Apochromat III differential interference contrast (DIC) objective (Zeiss). In time course experiments, microscope settings were unchanged throughout the experiment in order to obtain a semiquantitative signal. Cross-talk between FITC and Texas red was avoided through the use of the Zeiss L510 digital signal processor. The absence of bleed-through was confirmed by checking that the signal disappeared when viewed with single-wavelength filter blocks. Images were collected with LSM5 software (Zeiss) and modified by contrast stretching and merging using Adobe Photoshop CS2 (Adobe Systems Inc., San Jose, CA).

Total protein extracts and immunoblotting.

Total protein extracts were prepared as described by Volland et al. (16). Log-phase cells (optical density at 600 nm [OD600], 1.5) were suspended in 0.5 ml of water and then lysed by adding 50 μl of 1.85 M NaOH, 5% (vol/vol) β-mercaptoethanol. Proteins were precipitated by adding 50 μl 50% (wt/vol) trichloroacetic acid. The resulting pellets were resuspended in 15 μl 1 M Trizma base and 30 μl 3× Laemmli SDS-PAGE loading buffer (17). These samples were then either spotted directly onto a polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane for dot blotting or resolved on 10% polyacrylamide gels by SDS-PAGE and then transferred to a PVDF membrane (Immobilon, Millipore Corp., Bedford, MA) in standard Western blots. HA-tagged ATPases were quantified by reaction with rabbit anti-HA polyclonal antibody diluted 1/4,000 (Medical and Biological Laboratories MBL, Nagoya, Japan) followed by incubation with 125I-protein A, autoradiography, and phosphorimage analysis (Molecular Dynamics Storm 840; Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ). Alternatively, blots were developed using either horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibodies and the ECL chemiluminescent detection system (GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, United Kingdom) or alkaline phosphatase (AP)-conjugated secondary antibodies and BCIP/NBT (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl phosphate/nitroblue tetrazolium) chromogenic substrate (SIGMAFAST; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO).

Limited trypsinolysis of gradient-purified plasma membranes.

Plasma membranes were prepared from glucose-metabolizing and carbon-starved cells as described previously (18). Trypsinolysis was performed according to Nakamoto et al. (19) using trypsin/protein ratios as indicated.

ATP hydrolysis and protein determination.

The activity of the plasma membrane H+-ATPase was assayed at 30°C using a standard ATPase assay (18). Protein concentrations were measured as described previously (20) or as modified by Ambesi et al. (21), using bovine serum albumin as the standard.

Immunoprecipitation and detection of ubiquitinated ATPase.

Yeast strains grown overnight in selective CSM (QBiogene, OH) containing 2% galactose (CSMGal) were shifted to fresh medium containing 2% glucose for 3 h, and then wild-type or mutant Pma1 H+-ATPase expression was induced at 39°C for a specified time as described above. Immediately before (t = 0) and at designated times after induction, volumes of cell suspension equivalent to a standard number of OD600 units (usually 40) were collected. Cells were lysed, and HA-tagged ATPase was immunoprecipitated from solubilized yeast membranes using a modification of the method described by Galan et al. (22). Briefly, cells were vortexed with chilled glass beads for 4 1-min pulses in lysis buffer (0.1 M Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 0.15 M NaCl, 5 mM EDTA) supplemented with N-ethyl maleimide (NEM) to 25 mM, PMSF (phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride) to 0.5 mM, and a cocktail of leupeptin, aprotinin, pepstatin, and chymostatin (each at 2 μg/ml final concentration). Homogenates were centrifuged at 3,000 rpm for 5 min at 4°C, and then supernatants were collected and centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 30 min. Membrane-enriched pellets were resuspended in 0.5 ml TNET buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, 1% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS) plus protease inhibitors as listed above. Insoluble material was removed by centrifugation at 14,000 rpm for 30 min. Twenty-five μl of protein A Sepharose CL-4B matrix (0.125 g/ml in 25 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 20 mM NaCl, 0.01% sodium azide) was added to each volume of solubilized membranes, and the mixture was incubated with gentle mixing at 4°C for 90 min. After this preclearing step, the bead matrix was removed by centrifugation at 3,000 rpm for 5 min and each supernatant received a fresh 25 μl of protein A Sepharose CL-4B plus 20 μl of a 1/20 dilution of anti-HA (HA.11) monoclonal antibody 16B12 (Babco, Richmond, CA). Following overnight incubation at 4°C, the matrix was recovered by centrifugation at 5,000 rpm and washed a total of four times, twice with TNET, once with TNET plus 0.5 M NaCl, and finally with TNET. Fifty μl of 3× Laemmli SDS-PAGE loading buffer was used to resuspend the affinity matrix, and immunoprecipitates were recovered after incubation at 30°C for 15 min. Samples were separated on 10% polyacrylamide gels and immunoblotted as described above. Rabbit polyclonal antibodies were used to detect HA-tagged (MBL, Nagoya, Japan) or ubiquitinated (rabbit anti-ubiquitin; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, Mo) proteins, followed by incubation with HRP- or AP-conjugated anti-rabbit antibodies. Immunoblots were developed using either the ECL (GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, United Kingdom) or chromogenic (SIGMAFAST; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, Mo) detection system.

RESULTS

Distinct regions of the Pma1 H+-ATPase C terminus are required for trafficking, enzymatic activity, and glucose-mediated regulation.

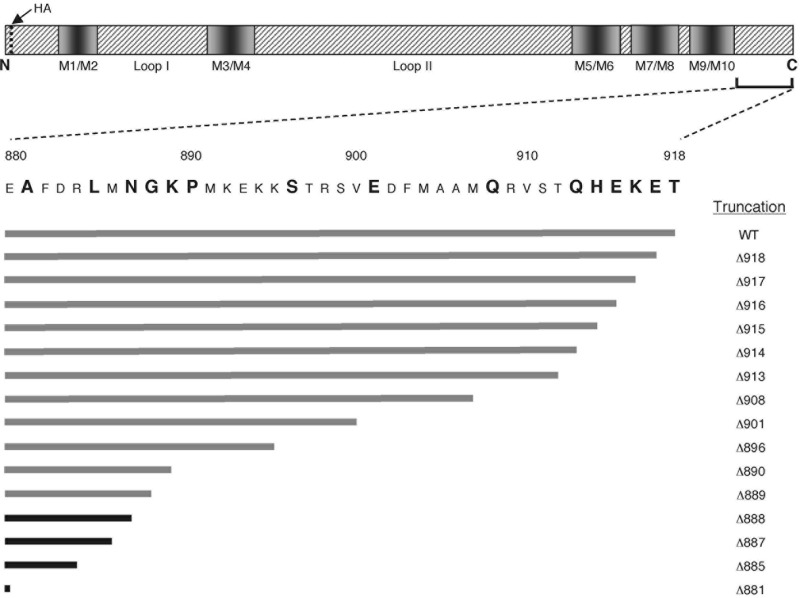

To map the functional domains of the C-terminal tail, progressive stepwise truncations were made, starting with Pma1-Δ918p (which lacked only the final residue, Thr918) and ending with Pma1-Δ881p (38 residues removed) (Fig. 1). Each pma1Δ allele incorporated an HA tag at the N terminus and was integrated into the chromosome in place of the wild-type PMA1 gene. Because deleterious mutations in the PMA1 gene can be repaired by gene conversion with the poorly expressed PMA2 gene (23), all integrations were made in a pma2Δ strain (BMY58). The C-terminally truncated pma1 mutants were then characterized with respect to growth, Pma1p expression at the plasma membrane, and H+-ATPase activity. Viable transformants were obtained using alleles truncated up to and including Lys889 (pma1-Δ889), but despite exhaustive screening, none were recovered for pma1-Δ888, pma1-Δ887, or pma1-Δ885. Thus, a Pma1 H+-ATPase truncated at Lys889 represented the longest C-terminal deletion mutation that still enabled growth, a result supported by conditional expression experiments (see below).

FIG 1.

Stepwise deletions in the C-terminal domain of Pma1 H+-ATPase. The domain structure of the S. cerevisiae Pma1 H+-ATPase is presented (upper), together with the specific sites of truncations made at the C terminus in this study (larger, boldface letters). Gray bars indicate viable mutations, while black bars show truncations that did not yield viable haploid yeast strains after integrative transformation. HA, hemagglutinin tag; M1/M2, transmembrane sequences M1 and M2; WT, wild type.

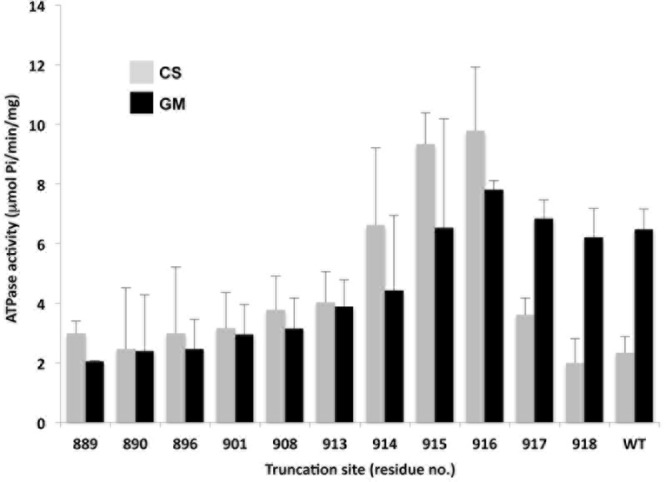

Table 2 and Fig. 2 present the properties of the viable truncation mutants from pma1-Δ918 through pma1-Δ889. In these experiments, expression and activity measurements were carried out with both carbon-starved (CS) and glucose-metabolizing (GM) cells, since glucose-dependent regulation of ATPase activity has been shown to be mediated by changes in kinase-mediated phosphorylation at C-terminal residues Ser911 and Thr912 (11). While the removal of a single amino acid residue (pma1-Δ918) reduced the steady-state expression level of Pma1p at the PM by up to 30% relative to that of the wild-type control, expression then remained constant with further truncations of up to 28 amino acids (pma1-Δ890). There was a modest additional decrease to just below 60% expression in cells expressing Pma1-Δ889p.

TABLE 2.

Analysis of pma1 C-terminal deletion mutants by growth rate and ATPase expression level

| Truncation | Growth ratea (OD units/h) | Expression by cell typeb |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| CS | GM | ||

| Wild type | 0.62 | 100 | 100 |

| Δ918 | 0.60 | 70 | 83 |

| Δ917 | 0.58 | 74 | 88 |

| Δ916 | 0.60 | 77 | 93 |

| Δ915 | 0.58 | 59 | 63 |

| Δ914 | 0.53 | 67 | 58 |

| Δ913 | 0.59 | 76 | 69 |

| Δ908 | 0.58 | 68 | 67 |

| Δ901 | 0.37 | 79 | 84 |

| Δ896 | 0.64 | 68 | 74 |

| Δ890 | 0.53 | 83 | 73 |

| Δ889 | 0.36 | 57 | 58 |

Average rate based on at least 3 cultures per strain.

Average expression level determined from at least 2 different preparations. CS, carbon starved; GM, glucose metabolizing.

FIG 2.

Effect of glucose metabolism on activity of C-terminally truncated ATPases. Bar graph shows the ATPase activities of WT and C-terminally truncated Pma1 H+-ATPases in PM preparations (see Materials and Methods) made from carbon-starved (CS; gray bars) or glucose-metabolizing (GM; black bars) cells. Numbers on abscissa represent the residue replaced with a TAA STOP codon. Error bars represent standard errors of the means (SEM) from assays performed on at least three different PM preparations.

The ATPase activity of PMs from GM cells was virtually unaffected by the first four truncations but declined gradually with subsequent truncations to plateau at 2 to 3 μmol/min/mg. In contrast, the suppression of ATPase activity by carbon starvation was affected dramatically by even minor truncations (Fig. 2). Removal of only two amino acids (pma1-Δ917) slightly reduced the autoinhibitory action of the C terminus in CS cells and the loss of three residues (pma1-Δ916) eliminated it altogether, actually elevating the PM ATPase activity of CS cells above that of GM cells. The shift in CS versus GM cells was also seen in pma1-Δ915 and pma1-Δ914 but with ATPase activity decreasing gradually in both cases. Finally, the glucose effect disappeared altogether in truncations made at, or upstream of, Glu913 (pma1-Δ913), consistent with our earlier finding that glucose-dependent regulation by the C-terminal tail depends upon the phosphorylation state of the Ser911/Thr912 pair (11).

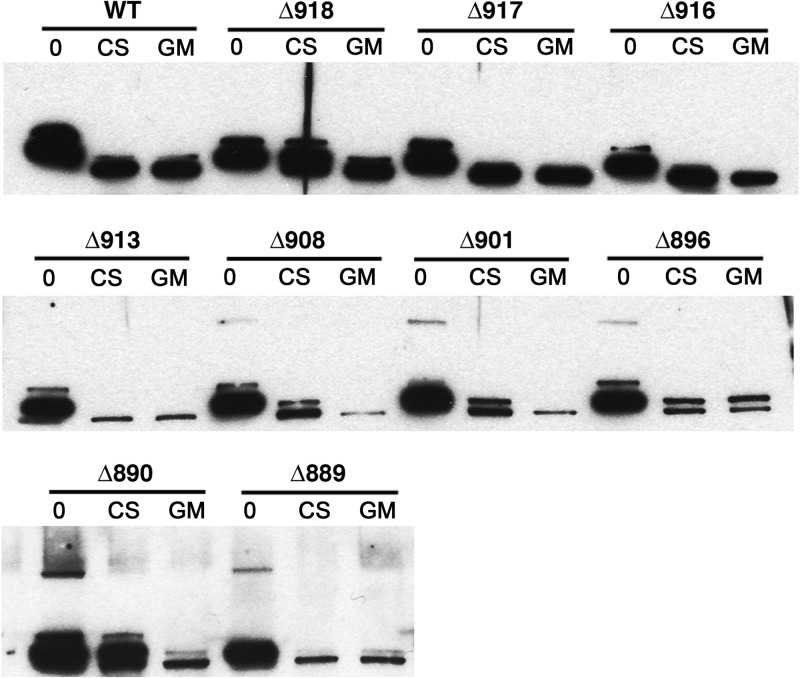

Limited trypsinolysis was then used to compare the conformations of truncated ATPases to the wild-type enzyme (Fig. 3). After brief trypsin digestion, PMs were immunoblotted and Pma1p digestion products detected with polyclonal anti-Pma1 antiserum. Under these conditions, the first two truncated forms (Pma1-Δ918p and Pma1-Δ917p) were indistinguishable from the wild type, while Pma1-Δ916p and Pma1-Δ915p (not shown) displayed only slight increases in trypsin sensitivity under GM conditions. Truncations of five residues (Pma1-Δ914p) or more rendered the proteins highly sensitive to trypsin under both CS and GM conditions, except for Pma1-Δ890p, which appeared to achieve a tighter conformation under CS conditions than most of the other truncations.

FIG 3.

Trypsin sensitivity of truncated ATPases as a measure of protein stability. Purified plasma membranes (5 μg protein) prepared from cells grown under CS or GM conditions were digested using a trypsin/protein ratio of 1:4. Aliquots of each digest (50 ng) were removed after 2.5 min, separated by SDS-PAGE on 4 to 15% polyacrylamide gradient gels, and immunoblotted with polyclonal rabbit anti-Neurospora crassa Pma1p antibody. The amount of high-molecular-weight ATPase remaining reflects how well the original protein was folded. Digests were performed on at least two different PM preparations for each strain/carbon source. Results shown are representative of the entire series of truncations.

To this point, the results serve to define three regions of the C-terminal tail: first, a region from the distal end of the last membrane-spanning segment to Gly888 that was required for maturation and function of the ATPase; second, a stretch of 27 amino acids from Lys889 to Lys916, within which truncations had a noticeable impact on protein folding and on glucose-dependent regulation but nonetheless permitted sufficient PM trafficking and ATPase activity to support growth; and third, the last two residues (Glu917 and Thr918), which were not necessary for folding, activity, trafficking, or regulation but were required for maximal stability of the ATPase in the plasma membrane.

Stability and trafficking of truncated ATPases to the cell surface.

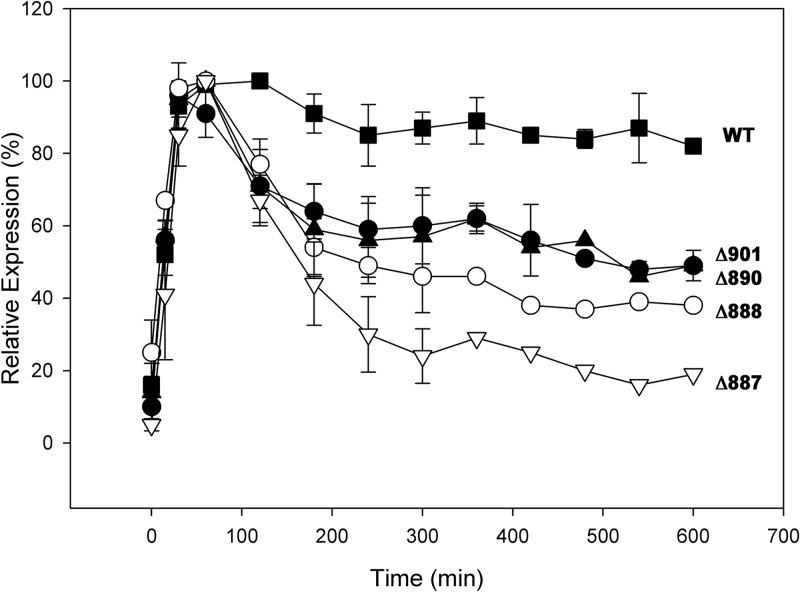

To directly test the stability of truncated ATPases, as well as their ability to traffic along the secretory pathway, each HA-tagged pma1Δ allele was subcloned into a centromeric plasmid (pBM45) under the control of a heat shock (2HSE) promoter. These constructs were then transformed into yeast strain BMY40, which has GAL1 promoter-regulated expression of chromosomal PMA1. Cells were grown in CSM-galactose medium at 23°C (PMA1 allele ON, pma1Δ allele OFF) and shifted to CSM-glucose medium at 23°C to turn off PMA1 expression and empty the secretory pathway of wild-type ATPase. A brief burst of mutant ATPase synthesis was induced by shifting the cells to 39°C for 15 min before returning them to 23°C. Stability and intracellular location of the truncated ATPases were monitored by detection of the HA tag. In addition to the truncated ATPases listed in Table 2, these studies included four more extensively truncated versions for which viable haploid transformants had not been recovered: Pma1-Δ888p, Pma1-Δ887p, Pma1-Δ885p, and Pma1-Δ881p. Wild-type HA-Pma1 H+-ATPase expressed from the same centromeric plasmid served as a control.

The stability of newly synthesized ATPases was analyzed using total protein extracts made from cells harvested between 0 and 10 h postinduction. Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE, immunoblotted versus anti-HA antibody, and then quantitated via 125I-protein A and autoradiography (Fig. 4). After a small initial decrease, the amount of plasmid-encoded wild-type ATPase synthesized during a 15-min burst held steady at about 90% for at least 10 h. Any ATPase lacking up to five residues from the C terminus was slightly less stable than the wild type (not shown), but when between 6 and 29 residues were removed, a new pattern emerged in which the amount of ATPase declined steadily over 3 to 4 h and then stabilized at ∼50% of the initial level. Pma1p expression profiles for two examples from this group, Pma1-Δ901p and Pma1-Δ890p, are shown in Fig. 4. Removal of additional C-terminal residues led to a progressive decrease in the steady-state amount of ATPase, to 40% in Pma1-Δ888p and 20% in Pma1-Δ887p, neither of which was able to support growth (as described above).

FIG 4.

Stability of transiently expressed truncated ATPases. Cultures were shifted to 39°C at t = 0 min to induce expression of plasmid-encoded, HA-tagged ATPases and then returned to 23°C at t = 15 min. Total protein extracts (see Materials and Methods) were separated by SDS-PAGE, immunoblotted against polyclonal anti-HA, and detected by 125I-protein A and autoradiography. Each point represents the averages from at least three determinations, and standard deviations are indicated. WT, squares; Pma1-Δ901p, solid circles; Pma1-Δ890, solid triangles; Pma1-Δ888, open circles; Pma1-Δ887, open inverted triangles.

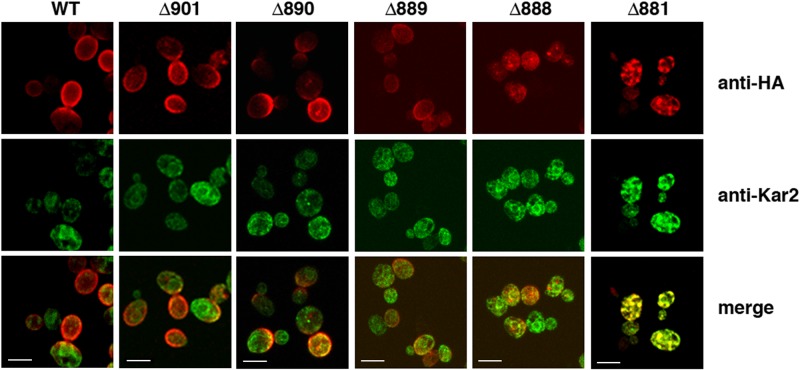

We visualized the intracellular distribution of the truncated ATPases by confocal immunofluorescence microscopy. Figure 5 shows the results of an experiment in which samples were taken 120 min after induction, and anti-HA antibody was used to decorate newly synthesized ATPase (red) while the ER was defined with antibody against the ER-localized molecular chaperone Kar2p (green). As described previously (4, 15), newly synthesized wild-type ATPase reached the PM by 120 min, with little evidence of residual intracellular labeling. Significant amounts of Pma1-Δ901p and Pma1-Δ890p also reached the cell surface, as did a smaller amount of Pma1-Δ889p, although some labeled intracellular ATPase was still visible. In contrast, Pma1-Δ888p was only seen intracellularly, distributed in a punctate pattern that colocalized partially with Kar2p. Stronger Kar2p colocalization was seen with Pma1-Δ887p, Pma1-Δ885p (not shown), and Pma1-Δ881p (Fig. 5). Thus, Lys889 appears to mark a cutoff point that is critical for the shipment of sufficient ATPase to the cell surface to support growth. Upstream truncations led to arrest in the ER, while truncations made at or downstream of Lys889 allowed a significant fraction of newly synthesized ATPases to travel to the PM.

FIG 5.

ATPases truncated upstream of Lys889 do not appear to reach the PM. Expression of HA-tagged ATPases was induced as described in the legend to Fig. 4, and the proteins were located using monoclonal anti-HA, followed by goat anti-mouse IgG conjugated to Alexa Fluor 594 (red) as a secondary antibody. Cells were imaged by confocal microscopy 120 min after the start of induction. The ER-resident ATPase/chaperone Kar2p was used as an ER marker and detected using a combination of rabbit anti-Kar2p and goat anti-rabbit IgG conjugated to Alexa Fluor 488 (green). Because images were taken using the same microscope settings, the signal intensity provides a semiquantitative indication of relative expression levels. Bar, 5 μm.

Dual quality control mechanisms for Pma1-Δ901p.

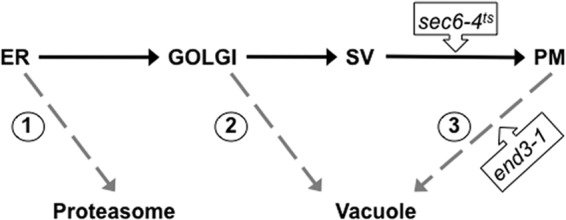

Work reported primarily from the laboratory of Amy Chang has shown that the cell uses multiple quality control mechanisms to eliminate poorly folded forms of Pma1 ATPase (Fig. 6 and reference 5): (i) in many cases, the mutant form is retrotranslocated from the ER into the cytoplasm and degraded in the proteasome by ER-associated degradation (ERAD; see reference 24 for a recent review); (ii) some misfolded Pma1 polypeptides escape the ER only to be rerouted from the Golgi complex to the vacuole for degradation; while (iii) a third subset of mutants is transported successfully to the PM but turned over more rapidly than the highly stable wild-type ATPase and delivered to the vacuole via endocytosis (25).

FIG 6.

Quality control checkpoints along the secretory pathway. Misfolded H+-ATPases may be recognized as aberrant and targeted for degradation at several points along the secretory pathway: 1, ER-associated degradation (ERAD) by the proteasome; 2, detection in the Golgi body followed by targeting to the vacuole and degradation; 3, detection at the PM followed by endocytosis to the vacuole and degradation. The QC checkpoint(s) involved in processing a particular mutant may be investigated using mutant yeast backgrounds, such as temperature-sensitive sec6(Ts) to block fusion of secretory vesicles (SV) with the PM or end3-1 to block endocytosis from the PM.

In a study of large stepwise truncations that encompassed the entire C-terminal half of the Pma1 H+-ATPase (4), we have shown previously that mutant polypeptides from Pma1-Δ452p (truncated in the middle of the cytoplasmic nucleotide-binding domain) to Pma1-Δ881p were protected in cells deficient in Pre1 and Pre2 proteasomal proteases; thus, they were processed predominantly by mechanism 1. In contrast, Pma1-Δ901p was completely protected when expressed in cells lacking the vacuolar Pep4 protease, suggesting that it is degraded primarily in the vacuole (mechanism 2 and/or 3) (Fig. 6); similar results have since been obtained for other pma1Δ mutants truncated as far back as Lys889 (not shown).

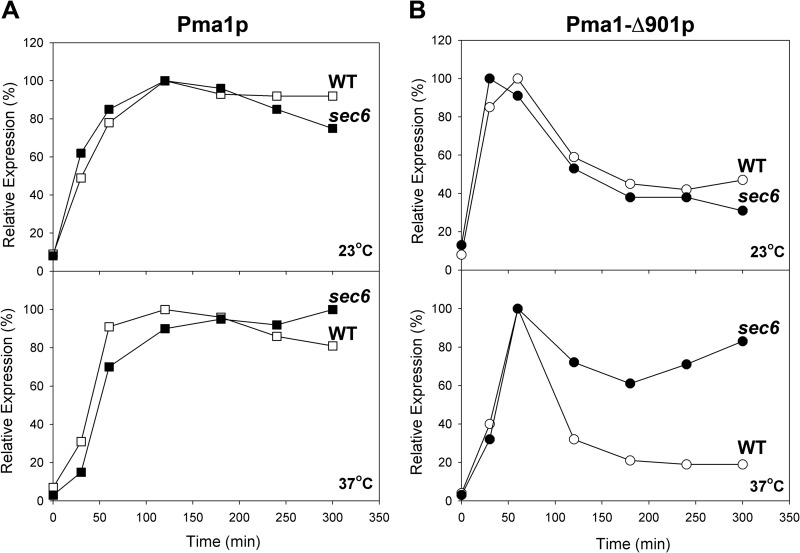

To learn more about the quality control pathways that handle such mutants, we tested to see whether Pma1-Δ901p could be protected by a sec6(Ts) mutation that prevents the fusion of post-Golgi secretory vesicles (SVs) with the PM. Because establishing the sec6(Ts) block depends upon maintaining the cells at an elevated temperature, plasmid-based ATPase synthesis was driven in this set of experiments by the promoter of the yeast MET3 gene and induced by removal of methionine from the growth medium (4). In the experiment shown in Fig. 7, synthesis of wild-type (native) or Pma1-Δ901 ATPase was induced for 15 min in methionine-free medium at 37°C in wild-type and sec6(Ts) backgrounds. The cells were then either maintained at 37°C [to block vesicle fusion in the sec6(Ts) background] or returned to 23°C (no block). At selected intervals up to 300 min, total protein extracts were prepared and the level of newly synthesized ATPase was assessed by quantitative immunoblotting using anti-HA antibody. Each yeast background gave the expected result when cells were incubated at 23°C: wild-type ATPase remained stable throughout the course of the experiment, while Pma1-Δ901p decayed to a fraction of its initial level (Fig. 7A). On the other hand, in cells maintained at 37°C, the sec6(Ts) block had little or no effect on newly synthesized wild-type ATPase but gave clear-cut protection of Pma1-Δ901p (Fig. 7B). Protection was incomplete, however, suggesting that this mutant form is processed in at least two different ways by the cell, with some of the ATPase recognized as abnormal early in the secretory pathway (perhaps at the Golgi complex) and shipped to the vacuole for degradation (mechanism 2), while the majority is ultimately delivered to the vacuole but only after it has been incorporated into post-Golgi SVs.

FIG 7.

sec6(Ts) block affords partial protection of Pma1-Δ901p at the restrictive temperature. Mid-log-phase cells growing in CSMGal-trp were shifted to CSMGlu-trp and incubated for 3 h to clear the secretory pathway of endogenous WT Pma1p, and expression of HA-tagged WT or HA-Pma1-Δ901p then was induced by transferring cells to CSMGlu-trp-met for 15 min at either 23 or 37°C. Synthesis of HA-tagged ATPases was turned off by the addition of 30 μg/ml methionine. Total protein extracts were made at the indicated times and analyzed by Western blotting using rabbit anti-HA to detect HA-Pma1p (see Materials and Methods). Relative expression levels for each protein, based on at least 3 replicate cultures, are plotted. (A) Expression of WT Pma1p in the presence and absence of the sec6(Ts) mutation at 23°C (upper) and 37°C (lower). (B) Expression of Pma1-Δ901p in the presence and absence of the sec6(Ts) mutation at 23°C (upper) and 37°C (lower). Note that expression of Pma1-Δ901p driven by the MET3 promoter decreased over time to lower levels (20 to 30%) than those seen earlier using 2HSE-driven expression (50 to 65%). This may have been due to tighter regulation of the MET3 promoter resulting in faster transcriptional shutdown and/or additional induction of protective heat shock protein chaperones during 2HSE-driven expression.

Ubiquitination in the quality control of C-terminally truncated Pma1 H+-ATPases.

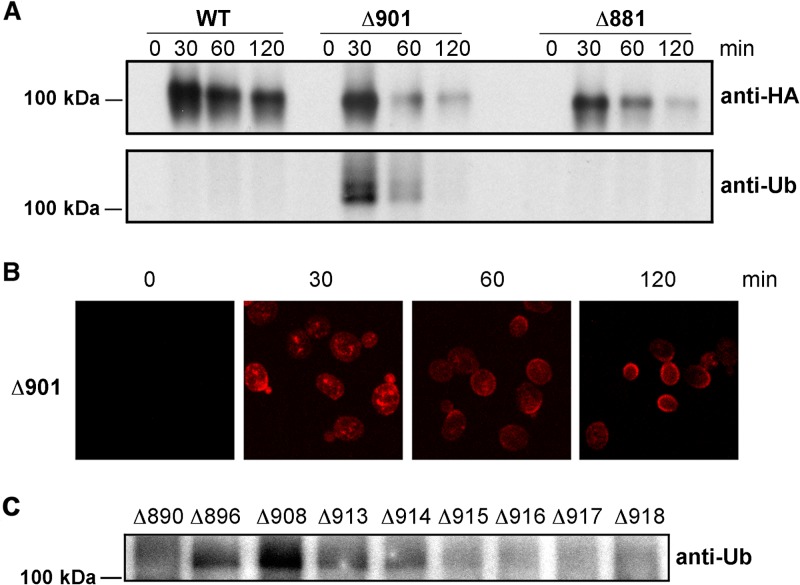

Although wild-type (native) Pma1 H+-ATPase is not ubiquitinated, certain temperature-sensitive ATPase mutants have been shown to be modified in this way prior to vacuolar degradation (25–27). Thus, it seemed possible that ubiquitination serves as a signal for quality control in the case of truncated ATPases (such as Pma1-Δ901p) that are also degraded primarily in the vacuole. We tested this idea for a series of truncated forms of the protein that were expressed transiently using the heat shock (2HSE) promoter system. In the experiment shown in Fig. 8A, cells expressing Pma1-Δ901p were compared to those expressing wild-type Pma1p or Pma1-Δ881p, the latter serving as an example of a mutant that is retained in the ER and processed by ERAD. At each time point, cells were lysed and newly synthesized ATPase was immunoprecipitated with anti-HA antibody. Equal aliquots of the immunoprecipitates were then separated on SDS-PAGE gels and immunoblotted with anti-ubiquitin antibody. As illustrated in Fig. 8A, there was clear evidence of ubiquitination in Pma1-Δ901p, with by far the heaviest modification seen at 30 min postinduction. This timing suggested that ubiquitination occurred prior to arrival at the PM, since Pma1-Δ901p was still intracellular at 30 min (Fig. 8B). No modified Pma1-Δ881p was detected at any of the time points; this result is discussed below.

FIG 8.

Pma1-Δ901p and other Pma1 H+-ATPases truncated between Pro890 and His914 are ubiquitinated en route to the PM. (A) Cells were induced to express WT, Pma1-Δ901p, or Pma1-Δ881p for 15 min as described in the legend to Fig. 4. Lysates were prepared at the indicated times, and Pma1 H+-ATPase was immunoprecipitated with anti-HA monoclonal antibody. Immunoprecipitates were then analyzed by Western blotting against polyclonal anti-HA and anti-ubiquitin antibodies (see Materials and Methods). (B) Confocal microscopy to track the cellular location of newly synthesized Pma1-Δ901 ATPase by confocal microscopy. (C) Lysates from cells expressing truncated mutant ATPases were tested for ubiquitin modification at 30 min postinduction by Western blotting with anti-ubiquitin antibody.

To gain further information, other truncation mutants were examined for ubiquitination at the 30-min time point (Fig. 8C). All of the ATPases truncated between Ser896 and His914 were seen to be ubiquitinated at 30 min, while there was no significant modification of Pma1-Δ890p or truncations made C terminal to His914 (Fig. 8C). These findings were consistent with the relative stabilities of the various truncated ATPases (see Fig. 3) and suggested that there is at least one potentially important ubiquitination site between Pro890 and Ser896.

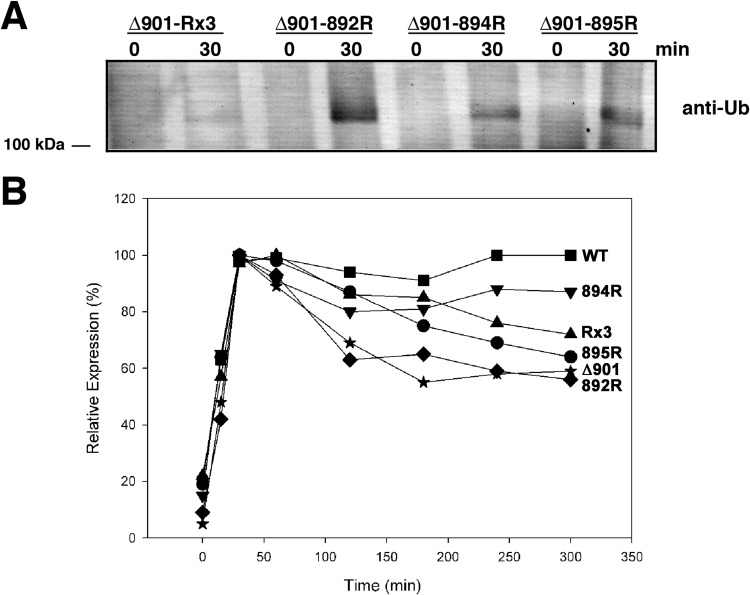

The five-amino-acid sequence bracketed by Pro890 and Ser896 contains three lysine residues (Lys892, Lys894, and Lys895) that are obvious targets for ubiquitin attachment. This possibility was explored by making Lys-to-Arg substitutions individually and in combination at all three positions in Pma1-Δ901p. HA-tagged ATPases were expressed using the 2HSE promoter system and sampled by immunoprecipitation with anti-HA antibody from protein extracts made before and after 30 min of induction at 39°C. As shown in Fig. 9A, substitution of all three lysines eliminated detectable ubiquitination of the mutant ATPase, and substitution at Lys894 or Lys895 reduced the level of ubiquitination; in contrast, substitution at Lys892 had no apparent effect. In keeping with this result, K894R, K895R, and the triply substituted mutant showed improved postinduction stability compared to that of Pma1-Δ901p, while there was no detectable improvement for K892R (Fig. 9B). Taken together, the data shown in Fig. 9 suggest strongly that residues Lys894 and Lys895 become modified by ubiquitin, while Lys892 appears to be inaccessible to the ubiquitination machinery. The same data are also consistent with the apparent absence of ubiquitinated Pma1-Δ881p (Fig. 8A), since this mutant lacks Lys894 and Lys895. Indeed, Pma1-Δ881p is predicted to have little, if any, C-terminal protein sequence exposed on the cytoplasmic side of the ER membrane, so it may fail to bind the molecular chaperones that recruit the E3 ubiquitin ligases required for ubiquitin attachment and subsequent retrotranslocation to the proteasome.

FIG 9.

Identification of specific lysine residues ubiquitinated in Pma1-Δ901p. (A) Lysates from cells carrying Lys-to-Arg substitution mutations made in a pma1-Δ901 background (BMY62) were tested before (t = 0) and at 30 min after induction of Pma1p expression to identify the Lys residue(s) that was targeted for ubiquitination. (B) Relative stabilities of WT and mutant ATPases were assessed as described in the legend to Fig. 4. Values at each time point represent the averages from at least 3 determinations. Error bars have been omitted for clarity, but the SEM was typically less than 10%.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, deletion and substitution mutations have been used to characterize the C-terminal domain of yeast Pma1 H+-ATPase, providing new insights into its role in targeting, stability, function, regulation, and degradation.

Is there a minimum length requirement for the C-terminal tail?

While definitive proof awaits further experiments, our inability to recover viable transformants from pma1 mutants with truncations upstream of Lys889 suggests that this is a dividing line for stable PM expression of a functional ATPase. Two pieces of evidence support this conclusion. First, the PM expression level of Pma1p in strains with integrated pma1 C-terminal truncations decreased abruptly for proteins truncated upstream of Pro890 (Table 2). Second, in conditional expression experiments, the trafficking of Pma1p mutants truncated upstream of Lys889 to the PM could not be detected by confocal microscopy (Fig. 5). This minimum length requirement for the Pma1p C-terminal tail is at odds with earlier studies that reported viable cells expressing PM H+-ATPases truncated by 40 (5) or even 46 (9) C-terminal residues. It should be noted, however, that the yeast strains used in the earlier studies retained a chromosomal PMA2 gene, raising the possibility of gene conversion events between it and any pma1Δ alleles that placed selective pressure on the growing cells (23). We have observed such events to occur well within the time frame of a typical expression experiment in PMA2-containing strains.

Gene conversion may also explain the dual population of Pma1 proteins detected in a cell culture expressing a pma1-Δ40C allele (5), with one fraction processed at the ER while the rest was shipped to the PM, but it was no longer detectable using an anti-HA antibody because the C-terminal triple HA tag was missing. In the same study, Liu and Chang (5) showed that a pma1-Δ30C mutant (which corresponds precisely to our Pma1-Δ889p) supported growth despite being differentially processed by both ERAD and vacuolar degradation pathways.

Amino acids close to the extreme C terminus are critical for autoregulation of Pma1p.

Truncation of the ATPase at, or upstream of, Lys916 nullified glucose-mediated regulation of enzyme activity, confirming the idea that autoinhibition of the enzyme following dephosphorylation of Ser911/Thr912 requires additional downstream sequence elements very close to the extreme C terminus. Similarly, the extreme C-terminal location of a pair of Tyr residues in the alpha subunit of the mammalian Na+, K+-ATPase is critical for proper Na+ ion binding on both sides of the membrane through interactions with Lys768 (in M5) and Arg935 (in the loop between M8 and M9) (28). Since Lys916 is conserved among fungal Pma1 H+-ATPases, we anticipate that substitution mutagenesis will determine which, if any, specific properties of this residue are indispensable for the inhibition of pump activity. By incorporating appropriate cross-linking reagents, it may also be possible to identify the intra- or intermolecular docking site involved in the inhibitory interaction. With regard to mechanism, it is worth noting that autoinhibition was also abrogated if the C terminus was extended by six histidines, presumably because the added residues interfered with the interaction between the dephosphorylated tail and the other domain(s) of the enzyme (A. Brett Mason, unpublished result).

As with other proteins, structural changes to the proton pump are often reflected by changes in its trypsin sensitivity. For example, a T912A mutation generates a trypsin-resistant ATPase, while T912D (which mimics the negative charge introduced by a phosphorylation event) results in trypsin sensitivity (29). In the present study, the influence of the C-terminal amino acid sequence on the overall structure of Pma1p was evidenced by the heightened trypsin sensitivity of truncations up to and including His914. One exception was the relatively resistant CS form of Pma1-Δ890p, suggesting that an ATPase polypeptide truncated at this point is still able to fold into a stable conformation that can be modified when glucose is available. These modifications to protein structure may reflect direct changes in the monomeric structure as influenced by the C-terminal domain, but it is also conceivable that they destabilize the structure through an effect on TM10, which was shown previously to be a critical component both for oligomerization/trafficking of the H+-ATPase (30) and for mediating the dominant lethal effects of mutations at the core of the enzyme (7).

Multiple fates of a misfolded truncated Pma1 H+-ATPase.

Pma1-Δ901p exemplifies a misfolded H+-ATPase that is only partially eliminated by QC mechanism(s). When expressed from an integrated pma1-Δ901 allele in haploid yeast, some of the mutant protein travels slowly through the secretory pathway to the PM, where it is maintained at 20 to 30% of the wild-type level and is able to support growth. The rest appears to be degraded in the vacuole, since it can be protected from premature degradation in a pep4Δ mutant background.

This behavior is partially reminiscent of a temperature-sensitive mutant (Pma1-10) that has been shown by Chang and her coworkers to be ubiquitinated under restrictive conditions and targeted to the vacuole (5). In that strain, instability of the ATPase was attributed to two amino acid substitutions (A165G and V197I) in the first cytoplasmic loop, located within the actuator (A) domain, but specific ubiquitination sites were not determined. In the present case, the simplicity and discrete location of the C-terminal truncation in Pma1-Δ901p has allowed us to identify two residues proximal to the truncation site (Lys894 and Lys895) that serve as major targets for ubiquitin modification and where replacement with Arg led to partial restoration of ATPase stability. While it seems unlikely that Lys894 and Lys895 are the only ubiquitination sites in misfolded Pma1 H+-ATPases, it will be interesting to see whether substitution of these two residues can stabilize, or even rescue, other pma1 mutant proteins that are recognized as misfolded products at the ER, Golgi complex, or PM. Relatively little is known about the quality control mechanisms that identify and process aberrant integral membrane proteins that are trafficked beyond the ER or become unstable at the PM. Thus, the pma1 truncation/substitution mutants that we have described and the potent ubiquitination sites that we have identified in this study should be useful tools for further investigation of the mechanisms and molecular components involved in post-ER quality control.

Taken together with our evidence for the important role of the C terminus in the biogenesis, stability, and activity of Pma1p, the demonstration of the C-terminal tail as a ubiquitin target adds to our appreciation of the multiple ways in which its state can determine the ultimate cellular fate of Pma1 H+-ATPase.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are indebted to Mark Rose for providing antibody to Kar2p and Efim Golub for assistance with some of the mutant constructs. Thanks also to other members of the Slayman laboratory for their helpful discussions.

This work was supported by NIH research grant GM15761 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 1 November 2013

REFERENCES

- 1.Bublitz M, Morth JP, Nissen P. 2011. P-type ATPases at a glance. J. Cell Sci. 124:2515–2519. 10.1242/jcs.088716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Palmgren MG, Nissen P. 2011. P-type ATPases. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 40:243–266. 10.1146/annurev.biophys.093008.131331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mandala SM, Slayman CW. 1989. The amino and carboxyl termini of the Neurospora plasma membrane H+-ATPase are cytoplasmically located. J. Biol. Chem. 264:16276–16281 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mason AB, Allen KE, Slayman CW. 2006. Effects of C-terminal truncations on trafficking of the yeast plasma membrane H+-ATPase. J. Biol. Chem. 281:23887–23898. 10.1074/jbc.M601818200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu Y, Sitaraman S, Chang A. 2006. Multiple degradation pathways for misfolded mutants of the yeast plasma membrane ATPase, Pma1. J. Biol. Chem. 281:31457–31466. 10.1074/jbc.M606643200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grossmann G, Opekarova M, Malinsky J, Weig-Meckl I, Tanner W. 2007. Membrane potential governs lateral segregation of plasma membrane proteins and lipids in yeast. EMBO J. 26:1–8. 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eraso P, Mazon MJ, Portillo F. 2010. A dominant negative mutant of PMA1 interferes with the folding of the wild type enzyme. Traffic 11:37–47. 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2009.01005.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miranda M, Pardo JP, Petrov VV. 2011. Structure-function relationships in membrane segment 6 of the yeast plasma membrane Pma1 H+-ATPase. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1808:1781–1789. 10.1016/j.bbamem.2010.11.034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Portillo F, de Larrinoa IF, Serrano R. 1989. Deletion analysis of yeast plasma membrane H+-ATPase and identification of a regulatory domain at the carboxyl-terminus. FEBS Lett. 247:381–385. 10.1016/0014-5793(89)81375-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pedersen BP, Buch-Pedersen MJ, Morth JP, Palmgren MG, Nissen P. 2007. Crystal structure of the plasma membrane proton pump. Nature 450:1111–1114. 10.1038/nature06417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lecchi S, Nelson CJ, Allen KE, Swaney DL, Thompson KL, Coon JJ, Sussman MR, Slayman CW. 2007. Tandem phosphorylation of Ser-911 and Thr-912 at the C terminus of yeast plasma membrane H+-ATPase leads to glucose-dependent activation. J. Biol. Chem. 282:35471–35481. 10.1074/jbc.M706094200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sherman F, Hicks JB, Fink GR. 1986. Methods in yeast genetics. A laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ito H, Fukuda Y, Murata K, Kimura A. 1983. Transformation of intact yeast cells treated with alkali cations. J. Bacteriol. 153:163–168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cherest H, Kerjan P, Surdin-Kerjan Y. 1987. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae MET3 gene: nucleotide sequence and relationship of the 5′ non-coding region to that of MET25. Mol. Gen. Genet. 210:307–313. 10.1007/BF00325699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ferreira T, Mason AB, Pypaert M, Allen KE, Slayman CW. 2002. Quality control in the yeast secretory pathway: a misfolded PMA1 H+-ATPase reveals two checkpoints. J. Biol. Chem. 277:21027–21040. 10.1074/jbc.M112281200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Volland C, Garnier C, Haguenauer-Tsapis R. 1992. In vivo phosphorylation of the yeast uracil permease. J. Biol. Chem. 267:23767–23771 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Laemmli UK. 1970. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 227:680–685. 10.1038/227680a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miranda M, Allen KE, Pardo JP, Slayman CW. 2001. Stalk segment 5 of the yeast plasma membrane H+-ATPase: mutational evidence for a role in glucose regulation. J. Biol. Chem. 276:22485–22490. 10.1074/jbc.M102332200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nakamoto RK, Rao R, Slayman CW. 1991. Expression of the yeast plasma membrane H+-ATPase in secretory vesicles. A new strategy for directed mutagenesis. J. Biol. Chem. 266:7940–7949 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lowry OH, Rosebrough NJ, Farr AL, Randall RJ. 1951. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J. Biol. Chem. 193:265–275 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ambesi A, Allen KE, Slayman CW. 1997. Isolation of transport-competent secretory vesicles from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Anal. Biochem. 251:127–129. 10.1006/abio.1997.2257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Galan JM, Moreau V, Andre B, Volland C, Haguenauer-Tsapis R. 1996. Ubiquitination mediated by the Npi1p/Rsp5p ubiquitin-protein ligase is required for endocytosis of the yeast uracil permease. J. Biol. Chem. 271:10946–10952. 10.1074/jbc.271.18.10946 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harris SL, Na S, Zhu X, Seto-Young D, Perlin DS, Teem JH, Haber JE. 1994. Dominant lethal mutations in the plasma membrane H+-ATPase gene of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 91:10531–10535. 10.1073/pnas.91.22.10531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smith MH, Ploegh HL, Weissman JS. 2011. Road to ruin: targeting proteins for degradation in the endoplasmic reticulum. Science 334:1086–1090. 10.1126/science.1209235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu Y, Chang A. 2006. Quality control of a mutant plasma membrane ATPase: ubiquitylation prevents cell-surface stability. J. Cell Sci. 119:360–369. 10.1242/jcs.02749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Egner R, Kuchler K. 1996. The yeast multidrug transporter Pdr5 of the plasma membrane is ubiquitinated prior to endocytosis and degradation in the vacuole. FEBS Lett. 378:177–181. 10.1016/0014-5793(95)01450-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pizzirusso M, Chang A. 2004. Ubiquitin-mediated targeting of a mutant plasma membrane ATPase, Pma1-7, to the endosomal/vacuolar system in yeast. Mol. Biol. Cell 15:2401–2409. 10.1091/mbc.E03-10-0727 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Toustrup-Jensen MS, Holm R, Einholm AP, Schack VR, Morth JP, Nissen P, Andersen JP, Vilsen B. 2009. The C terminus of Na+,K+-ATPase controls Na+ affinity on both sides of the membrane through Arg935. J. Biol. Chem. 284:18715–18725. 10.1074/jbc.M109.015099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lecchi S, Allen KE, Pardo JP, Mason AB, Slayman CW. 2005. Conformational changes of yeast plasma membrane H+-ATPase during activation by glucose: role of threonine-912 in the carboxy-terminal tail. Biochemistry 44:16624–16632. 10.1021/bi051555f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kuhlbrandt W, Zeelen J, Dietrich J. 2002. Structure, mechanism, and regulation of the Neurospora plasma membrane H+-ATPase. Science 297:1692–1696. 10.1126/science.1072574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]