Abstract

Evolutionarily conserved 14-3-3 proteins have important functions as dimers in numerous cellular signaling processes, including regulation of transcription. Yeast 14-3-3 proteins, known as Bmh, inhibit a post-DNA binding step in transcription activation by Adr1, a glucose-regulated transcription factor, by binding to its regulatory domain, residues 226 to 240. The domain was originally defined by regulatory mutations, ADR1c alleles that alter activator-dependent gene expression. Here, we report that ADR1c alleles and other mutations in the regulatory domain impair Bmh binding and abolish Bmh-dependent regulation both directly and indirectly. The indirect effect is caused by mutations that inhibit phosphorylation of Ser230 and thus inhibit Bmh binding, which requires phosphorylated Ser230. However, several mutations inhibit Bmh binding without inhibiting phosphorylation and thus define residues that provide important interaction sites between Adr1 and Bmh. Our proposed model of the Adr1 regulatory domain bound to Bmh suggests that residues Ser238 and Tyr239 could provide cross-dimer contacts to stabilize the complex and that this might explain the failure of a dimerization-deficient Bmh mutant to bind Adr1 and to inhibit its activity. A bioinformatics analysis of Bmh-interacting proteins suggests that residues outside the canonical 14-3-3 motif might be a general property of Bmh target proteins and might help explain the ability of 14-3-3 to distinguish target and nontarget proteins. Bmh binding to the Adr1 regulatory domain, and its failure to bind when mutations are present, explains at a molecular level the transcriptional phenotype of ADR1c mutants.

INTRODUCTION

14-3-3 proteins are evolutionarily conserved and ubiquitously expressed in all eukaryotes (1–3). Multiple isoforms are found in various organisms, ranging in number from 2 in yeast, Caenorhabditis elegans, and Drosophila melanogaster to 7 in mammals and 14 in Arabidopsis. 14-3-3 proteins act as important cellular modulators and regulate essential signaling processes to influence cell viability, growth, differentiation, cell cycle regulation, apoptosis, vesicular trafficking, etc. They do so by interacting with Ser/Thr-phosphorylated motifs in functionally diverse signaling proteins, including kinases, phosphatases, and transmembrane receptors, and affect their activity, subcellular localization, and ability to interact with other proteins or small-molecule substrates.

14-3-3 proteins function as homo- and heterodimers formed by different isoforms (1), in which two monomers associate with each other through multiple hydrophobic and polar contacts, as well as by several salt bridges within the first four N-terminal α-helices (4, 5). 14-3-3 dimers are horseshoe- or clamp-like in shape, and each monomer provides a target-binding amphipathic groove (5). Theoretically, each dimer can bind two identical or different target molecules or two different sites of a single target molecule (5). 14-3-3 proteins recognize target proteins containing either a mode I (RSXpS/TXP), mode II (RXY/FXpS/TXP) (6, 7), or mode III (carboxy terminal, pS/TX1-2CO2H) (8, 9) motif, where p indicates a phosphorylated residue and X is any amino acid other than Pro. In addition, 14-3-3 proteins can recognize nonphosphorylated targets (1, 10, 11) and phosphoserine/threonine-containing sequences distinct from the canonical mode I, II, and III motifs (12–15). The binding of mammalian and plant 14-3-3 proteins has been characterized in detail, but whether these binding modes are conserved between higher and lower eukaryotes has not been determined.

Although dimerization of 14-3-3 is crucial for its function, it was observed that under certain conditions, 14-3-3 monomers can bind some of its targets, such as Raf kinase (16, 17), Bcr (18), tryptophan hydroxylase (19), platelet glycoprotein Ibα (GPIbα) (20), DAF-16 (21), Drosophila Slowpoke calcium-dependent potassium channel (dSlo) (22), Tau, and HspB6 (23, 24). However, a dimer-incapable truncated form of 14-3-3ζ was unable to bind vimentin both in vitro and in vivo (25). Notably, binding of 14-3-3ζ monomer does not regulate the activity of Raf kinase, whereas for Drosophila dSlo, the 14-3-3ζ monomer is functional. Whether dimerization is required for 14-3-3 function(s) may depend on how that function is carried out.

As in higher eukaryotes, redundant 14-3-3 isoforms in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Bmh1 and Bmh2 (26), regulate diverse signaling and cell differentiation pathways, including pseudohyphal differentiation, the DNA damage checkpoint, nitrogen catabolism, TOR signaling, stress response, protein degradation, retrograde signaling, exocytosis and vesicle transport, catabolite repression, and cell cycle regulation. Bmh also contributes to glucose repression by inhibiting the transcription of glucose-repressed genes (27–29).

Glucose repression is an intrinsic property of the budding yeast S. cerevisiae. Genes required for utilization of glucose are repressed when cells are grown in its presence (20) and activated upon its depletion or replacement by a nonfermentable carbon source. The yeast homologue of the AMP-activated protein kinase Snf1 plays a central role in the signaling pathway(s) for expression of glucose-repressed genes (30, 31). Snf1 controls the transcription of glucose-repressed genes in multiple ways, including inhibiting a repressor's function (32–37); inducing the expression, promoting the activation, and facilitating the promoter binding of a transcription activator (38, 39); and activating transcription initiation and stabilizing the nascent transcript (40). In response to low glucose, Snf1 activates two transcription factors, Cat8 (Zn cluster DNA binding) and Adr1 (Zn finger DNA binding) (41), that function both independently and in combination to activate the expression of glucose-repressed genes (42). Snf1 regulates the activity of Cat8 at the transcriptional and posttranscriptional levels, whereas it regulates Adr1 uniquely at the posttranscriptional level (43).

A role for Bmh in glucose repression was discovered after it was found to be associated with Reg1 (27), a subunit of the PP1-type protein phosphatase Glc7, which dephosphorylates and inactivates Snf1. Snf1 is apparently partially active in the presence of glucose when Bmh is absent, leading to constitutive activation of glucose-repressed genes. A second role for Bmh in glucose repression was suggested by the synergism observed when both Reg1 and Bmh were absent. This second inhibitory function of Bmh is due to direct binding of Bmh to the Adr1 regulatory domain (RD) (residues 215 to 260) and inhibition of a nearby cryptic activation domain (cAD) (residues 255 to 360) (27, 44). Bmh binding occurs on promoter-bound Adr1 and inhibits its activity after recruitment of RNA Pol II (45). Although some details of the mechanism of regulation of Adr1 activity by Bmh are known, how the two interact has not been determined. Surprisingly, there is no such study available for yeast 14-3-3 and its client. Therefore, the residue and motif preferences of yeast 14-3-3 are unknown.

In the present study, we mapped the minimal Bmh binding region on Adr1 and found that it colocalizes with ADR1c alleles, residues 226 to 239. Extensive mutational analysis distinguishes two regions that are important for Bmh binding: a core region consisting of residues immediately flanking Ser230, the site of phosphorylation, and a distal region that participates in Bmh binding without affecting Ser230 phosphorylation. This result suggests the direct involvement of residues outside the 14-3-3 motif in interacting with Bmh. The inability of monomeric Bmh to bind and regulate Adr1 activity suggests that the distally located residues, including Tyr239, might be providing a contact with the second subunit of the Bmh dimer to accomplish stable and functional interaction between Adr1 and Bmh.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Yeast strains and growth of cultures.

All the strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. Epitope tags were introduced according to previously published methods (46, 47). Yeast cultures were grown in either yeast extract-peptone medium or synthetic medium lacking the appropriate amino acid or uracil for plasmid selection. The repressed cultures contained 5% glucose, and the derepressed cultures contained 0.05% glucose. Cultures of yeast were grown at 30°C. The bmh1-170 allele is temperature sensitive for growth at 37°C, but not at 30°C. However, it displays the same defect in Adr1-dependent gene expression at both temperatures (44), so 30°C was employed to avoid introducing temperature stress.

TABLE 1.

Strains used in the study

Plasmid constructs.

All pOBD2-based vectors were made by cloning the corresponding coding sequence into the TRP1-CEN4 vector, pOBD2 (48), using gap repair methods (49, 50), where proteins were expressed as N-terminal Gal4 DNA binding domain (Gal4DBD) fusions, as described by Parua et al. (44). PCR fragments were generated using forward and reverse primers that contained homology to the vector sequences flanking the polylinker region of pOBD2, as well as homology to ADR1. The NcoI- and PvuII-digested pOBD2 plasmid (51) and a PCR fragment were used to transform PJ69-4a to Trp+ prototrophy. Plasmid DNA from Trp+ transformants was rescued and sequenced to confirm that recombination had produced the correct in-frame gene fusion using primers OBDsF and OBDsR. Western analysis with an anti-Gal4DBD monoclonal antibody (RK5C1; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) was used to confirm the synthesis of a fusion protein of the correct size.

pKP86 was generated by incorporating mutations into the wild-type BMH1 copy in the plasmid pBF-BMH1 (a gift from S. Zheng) using a QuikChange II XL site-directed mutagenesis kit (Agilent Technologies). pKP92 was generated by cloning mutated BMH1 amplified from pKP86 into pGEX-3X at the BamHI site. DNA sequencing analysis tested the sequence and directionality of the insert using the sequencing primer GEX_sF. All plasmids and primers are listed in Tables S1 and S2, respectively, in the supplemental material.

Mutagenesis.

All site-directed and deletion mutations were created either by the overlap extension method or using a QuikChange II XL site-directed mutagenesis kit (Agilent Technologies).

Western blot analysis.

Western blot analyses were performed according to the manufacturer's instructions for the Odyssey infrared imaging system (LiCor Biosciences). Proteins on the polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane were visualized using diluted monoclonal (1:500) and polyclonal (1:1,000) primary antibodies and LiCor λ800 (1:2,500) secondary antibodies. All primary antibodies were either obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology or produced by Bethyl Laboratories.

Preparation of protein extracts from yeast cells.

Protein extracts from yeast cells were prepared following the procedure described by Parua et al. (44). In brief, 50 to 100 ml of yeast cell culture grown to an A600 of ∼1 was used for protein extraction. Cells were collected by centrifugation at 1,600 × g for 5 min at 4°C in a Sorvall RC3B-plus centrifuge, washed once with 15% glycerol containing 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), and resuspended in an equal volume of chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) lysis buffer (50 mM HEPES-KOH, pH 7.5, 140 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, 0.1% sodium deoxycholate) containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors (Sigma). The cells were broken with glass beads in a Savant FP120 FastPrep machine with two disruption cycles of 45 s at a speed setting of 4.0. The unbroken cells and debris were pelleted by centrifugation in a microcentrifuge at 13,600 × g for 10 min. The clarified extract was collected in a fresh microcentrifuge tube containing 1 mM PMSF and 1× phosphatase inhibitor and used in subsequent experiments.

GST pulldown assays.

Glutathione S-transferase (GST) pulldown assays were done following the protocol described by Parua et al. (44). GST-Bmh1 wild-type (Bmh1-wt) and mutant fusion proteins were expressed from pGEX-3X-BMH1 and pKP92, respectively, in Escherichia coli BL21(DE3). The fusion proteins were immobilized on glutathione-Sepharose 4B beads as described by the manufacturer (GE Healthcare Life Sciences). Pulldown assays were performed using 30 to 40 μg of glutathione-Sepharose 4B-coupled GST fusion proteins and yeast extract containing ∼2 mg of total proteins in 1× PBST (phosphate-buffered saline containing 0.1% Tween 40), 1× protease inhibitor, and 1× phosphatase inhibitor (Sigma). The suspension was incubated at 4°C for 1 h with continuous nutation. The beads were then pelleted by centrifugation at 320 × g for 1 min, washed three times with 1× PBST, and resuspended in 60 μl of 2× LDS-NuPAGE sample buffer, followed by heating at 95°C for 5 min. Fractions collected at different steps of the pulldown assays were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting.

mRNA isolation and qRT-PCR.

Total RNA was extracted from strains grown in either repressing or derepressing medium using the acid phenol method described by Collart and Oliviero (52). Residual DNA in the RNA preparation was removed by treatment with DNase I (Ambion) following the manufacturer's recommendations. cDNA synthesis was performed with SuperScript III (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer's protocol. Quantitative real-time reverse transcription (RT)-PCR (qRT-PCR) for measuring mRNA levels was performed using a 1:300 dilution of the cDNA. A standard curve was generated from ACT1 primers and used to quantify all of the RNA levels. Samples were prepared from biological triplicates and analyzed in duplicate.

β-Galactosidase assays.

β-Galactosidase assays were performed as described by Guarente (53). Cells were grown at 30°C in selective medium to an A600 of 1.0. The reported values (in Miller units) are the averages of the results for three to five transformants.

Protein expression and purification from E. coli.

Bmh1 wild type and mutants were expressed in E. coli as an N-terminal GST tag from the vectors pGEX-3X-BMH1 and pKP92, respectively. Protein purification was done following the protocol described by Parua et al. (54). Briefly, BL21(DE3) cells harboring the respective plasmid were induced by 500 μM IPTG at an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of ∼0.6 to 0.7 for 4 h at 37°C. Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 5,000 × g at 4°C for 7 min and suspended in lysis buffer (1× phosphate-buffered saline, 10% glycerol, 10 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and 200 μg/ml lysozyme, pH 7.4). The cells were lysed by sonication, followed by centrifugation at 17,400 × g for 20 min at 4°C to collect the clear supernatant, which was applied to a glutathione-Sepharose 4B column (GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences AB, Sweden) preequilibrated with the lysis buffer. The column was washed with 10 times the bead volume of wash buffer (1× phosphate-buffered saline and 10% glycerol, pH 7.4). Protein was cleaved from GST using factor Xa protease (New England BioLabs) by incubating the protein-immobilized beads at 4°C for 24 h with a 10:1 (protein-enzyme) weight ratio. The collected flowthrough contained the purified protein. The level of purification was determined by running Any KDMini Protean TGX gels (Bio-Rad), followed by Coomassie staining.

Glutaraldehyde cross-linking.

Glutaraldehyde cross-linking was used to determine the dimeric state of Bmh1-wt and the mutant, as described by Parua et al. (54). Briefly, 2 μg of E. coli-expressed and purified wild-type and mutant Bmh1 was incubated with 0.1% glutaraldehyde (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) in a reaction buffer containing 20 mM Tris-Cl, 150 mM NaCl, and 1 mM EDTA (pH 8.0) at 25°C for the specified time (in minutes). The reaction was stopped by addition of glycine to a final concentration of 200 mM, followed by SDS-PAGE sample buffer. The reaction mixtures were heated for 5 min at 95°C and electrophoresed on Any KDMini Protean TGX gels (Bio-Rad). Protein was visualized by Coomassie staining.

RESULTS

Bmh binding region and Adr1c mutations colocalize to amino acids 226 to 240.

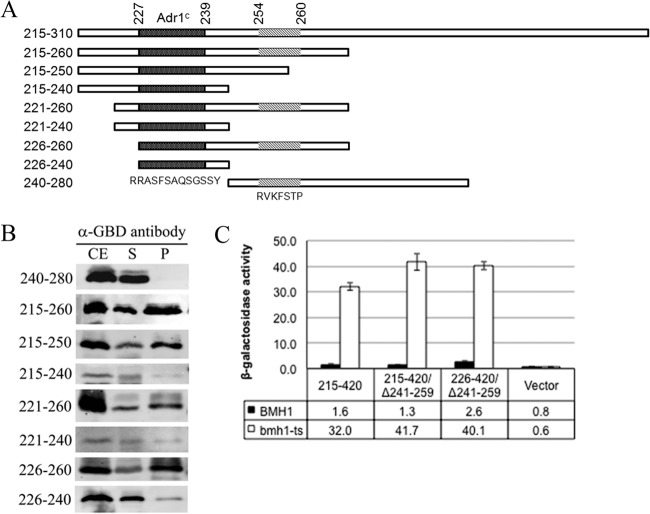

Sequence analysis suggests that the Bmh binding region of Adr1, residues 215 to 260, consists of two blocks of conserved amino acids, 226 to 240 and 254 to 260, each of which contains 14-3-3 motif-like sequences (44). Residues 227 to 232 (RRASFS) match motif I (RXX[pS/T]XP, where X is any amino acid), with Ser in place of Pro at position +2 (Fig. 1A). Residues 254 to 260 (RVKFSTP) perfectly match consensus motif II (RXXX[pS/T]XP) (2) (Fig. 1A). To determine whether they are important for Bmh binding, we performed GST pulldown assays using E. coli-expressed GST-Bmh1 and yeast extracts prepared from cells expressing various Gal4DBD-Adr1 variants encompassing the amino acid 215 to 260 region of Adr1 (Fig. 1A). As shown in Fig. 1B, the shortest protein fragment retained with GST-Bmh1 contained amino acids 226 to 240, whereas the fragment (residues 240 to 280) containing consensus motif II (RVKFSTP at 254 to 260) was not pulled down with GST-Bmh1. An independent experiment using Gal4DBD-Adr1 fusion variants with or without the 254-to-260 region encompassing residues 215 to 310 of Adr1 suggests that the amino acid 254 to 260 region is not required for binding (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). These results suggest that amino acids 226 to 240 of Adr1 are necessary and sufficient for Bmh binding. Surprisingly, all 21 ADR1c mutations found genetically were localized within this region (55–57), suggesting that the region has a unique function.

FIG 1.

Identifying the minimum Bmh binding region in Adr1. (A) The indicated Adr1 regions were expressed as Gal4DBD fusion proteins in yeast. The dark and light shaded areas represent 14-3-3 motifs. (B) GST pulldown results obtained after Western blotting with anti-Gal4DBD antibody. GST-Bmh pulldown assays were done using E. coli-expressed GST-Bmh1 and yeast extract containing Gal4DBD-Adr1 variants diagramed in panel A. CE, cell extract; S, supernatant; P, pellet. (C) β-Galactosidase activity assays from the reporter cassette (GAL10p-CYC1-lacZ) in BMH1 wild-type and bmh1-ts (bmh1-170) mutant strains expressing Gal4DBD-Adr1 fusion proteins (indicated in the graph). Cultures of yeast were grown at 30°C. The bmh1-170 allele displays the same defect in Adr1-dependent gene expression at 30°C as at 37°C (44). The error bars represent the standard deviations in three separate experiments using three different biological replicates.

Next, we asked whether this minimal Bmh binding region (amino acids 226 to 240) is sufficient to cause Bmh-mediated inhibition of transcription factor activity. We generated a Gal4DBD-fused Adr1 variant containing Adr1 amino acids 226 to 240, the Bmh binding region, and the cAD (amino acids 260 to 360), and its activity was evaluated in both BMH1 wild-type and bmh1-ts mutant strains at 30°C by measuring β-galactosidase activity from a reporter cassette, GAL10p-lacZ. The bmh1-170 allele used in these experiments exhibits the same defect in Adr1-dependent gene expression at 30°C as at 37°C (reference 44 and unpublished data), so the lower temperature was used for all experiments to avoid heat stress. As shown in Fig. 1C, the minimal Bmh binding region completely inhibited the transcriptional activity of cAD in the BMH1 wild-type strain, but not in the bmh1-ts mutant, suggesting that amino acids 226 to 240 are sufficient to provide the platform for Bmh binding and Bmh-mediated inhibition of Adr1 activity.

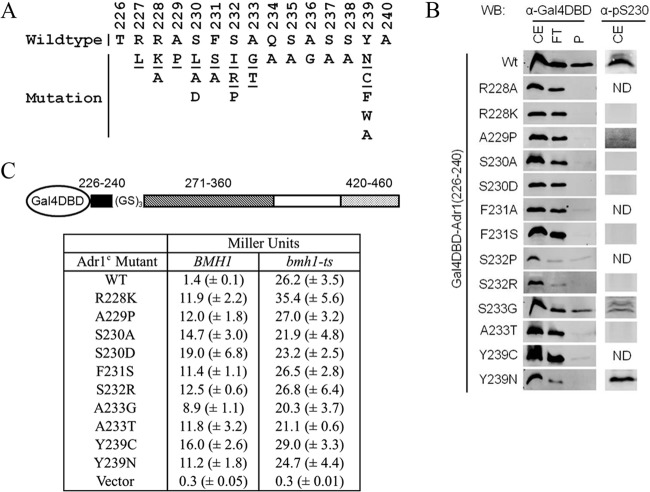

Adr1c mutations abolish the binding of Bmh.

As noted above, the Bmh binding region and Adr1c mutations colocalize to amino acids 226 to 240. Thus, we asked whether Bmh is the missing link between Adr1c mutations and their constitutive activity under repressing condition (58). A total of 21 different ADR1c alleles were identified genetically, representing 11 amino acid substitutions (ADR1c alleles) at 8 different positions and distributed over residues 227 to 239, as schematically presented in Fig. 2A (55–57). To examine the influence of ADR1c mutations on Bmh binding, we performed GST pulldown assays using yeast extract expressing a Gal4DBD-fused Adr1 variant encompassing amino acids 226 to 240 with a specific ADR1c point mutation and glutathione-Sepharose 4B-immobilized GST-Bmh1. As shown in Fig. 2B (left), all of the mutants tested showed no or a reduced level of interaction. The effect of the ADR1c mutations on Bmh binding could be due to reduced or absent phosphorylation of Ser230. Although the identity of the kinase that phosphorylates S230 in vivo is unclear (59), it can be phosphorylated in vitro by cyclic AMP (cAMP)-dependent protein kinase (55, 56) and by Ca2+-calmodulin-dependent protein kinase (60) and regulates Adr1 activity in a carbon source-dependent way (55, 56, 58, 61). 14-3-3 proteins preferentially interact with Ser/Thr-phosphorylated targets (1, 2), and Ser230 phosphorylation is important in regulation of Adr1 activity by Bmh (44). Therefore, we measured the phosphorylation level of Ser230 in all of the Adr1 variants by Western blot analysis using anti-pSer230 antibody. As shown in Fig. 2B (right), A229P and A233G were very weakly phosphorylated and Y239N was significantly phosphorylated at Ser230. Phosphorylation of the other Adr1c proteins was not detected, even though the proteins were present. This result suggests that Bmh binding depends on the phosphorylation of Ser230 and indicates that most of the ADR1c mutations disrupted phosphorylation of Ser230 and thereby prevented Bmh binding. The results for the Y239N mutant were quite surprising and interesting. Despite a level of Ser230 phosphorylation comparable to that of the wild type, the substitution completely abolished binding, indicating that Y239 plays an important role in Bmh binding, either by taking part in interaction directly or by influencing the peptide orientation in the target binding cleft(s) of Bmh. Therefore, it was important to study how distally located Y239 influences Bmh binding without affecting Ser230 phosphorylation. Furthermore, this impairment of binding of Y239 mutants was not due to the influence of its very C-terminal location in the context of the 226-to-240 peptide, as we obtained consistent results using a construct encompassing amino acids 226 to 250 of Adr1 (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). In addition, other mutants also showed binding results consistent with those observed using the amino acid 226 to 240 region of Adr1. As we observed that all of the ADR1c mutations disrupted Bmh binding, we measured their effects on Adr1 activity by evaluating β-galactosidase activity using a reporter cassette, GAL10p-lacZ. We generated various Gal4DBD-fused Adr1 proteins comprising the Bmh binding region (amino acids 226 to 240) with or without ADR1c mutations, the cAD (amino acids 260 to 360), and TAD III (amino acids 420 to 460). As shown in Fig. 2C, all of the mutant proteins showed constitutive reporter activity in a Bmh wild-type strain, a result that is consistent with Bmh binding inhibiting transcription activation. As expected from the binding results, the A233G mutation showed comparatively low inhibition of reporter activity. The activity of the mutants was further elevated in a bmh1-ts mutant strain for unknown reasons perhaps related to the absence of Bmh-mediated inhibition of Snf1. In conclusion all of the ADR1c mutations disrupted Bmh binding and reduced or eliminated Bmh-dependent inhibition of the Gal4DBD-Adr1 fusion proteins. We conclude that Bmh is the missing link between ADR1c mutations and their ability to activate gene expression in the presence of glucose (58), to hyperactivate gene expression under derepressive growth conditions (58), and to suppress the requirement for Cat8 at genes normally codependent on both Adr1 and Cat8 (45). Whether the absence of Bmh, like ADR1c mutations, promotes petite formation (62) and suppresses the requirement for some coactivators (44) remains to be tested.

FIG 2.

Effect of Adr1 mutation(s) on Bmh binding and Bmh-mediated regulation of transcriptional activity. (A) Adr1 (amino acids 226 to 240) wild-type sequence and amino acid substitutions. The underlined residues are genetically identified ADR1c alleles. (B) (Left) GST pulldown results after immunoblotting (Western blotting [WB]) with anti-Gal4DBD antibody. GST pulldown was done using E. coli-expressed GST-Bmh1 and a yeast extract (CE)-containing Gal4DBD-Adr1 fusion variant with the indicated mutations. FT, flowthrough; P, pellet. (Right) Ser230 phosphorylation status. The results were obtained after Western blotting of the CE with anti-pSer230 antibody. ND, not determined; Wt, wild type. (C) lacZ reporter assays from plasmid pHZ18′ (GAL10p-CYC1-lacZ) (53) in BMH1 wild-type and bmh1-ts (bmh1-170) mutant strains expressing a Gal4DBD-fused Adr1 variant with the indicated mutations. (GS) represents a six-amino-acid linker consisting of alternating Gly-Ser residues. Cultures of yeast were grown at 30°C. The bmh1-170 allele displays the same defect in Adr1-dependent gene expression at 30°C as at 37°C (44). The expressed fusion cassette is diagramed at the top. β-Galactosidase activity is expressed as Miller units with standard deviations generated from three separate experiments using three different biological replicates.

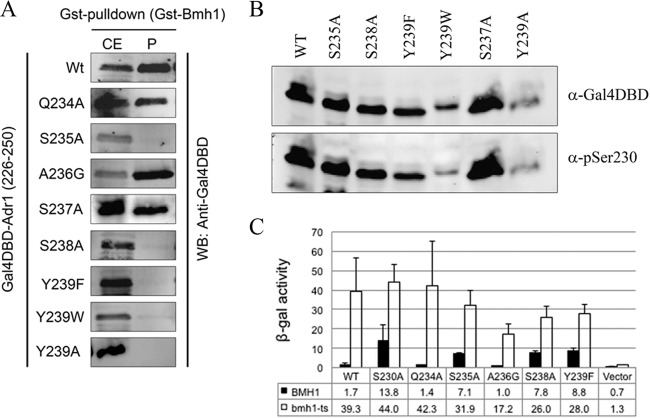

Role of residues other than Adr1c in Bmh binding.

No mutation was found by genetic screening in the region between Ala233 and Tyr239 (Gln234 to Ser238). To reveal their role, if any, in Bmh binding and inhibition of Adr1, we generated Gal4DBD fusion proteins with amino acids 226 to 250 of Adr1 that had substitutions for each residue from Q234 to S238, as indicated in Fig. 2A. GST pulldown assays were performed using glutathione-Sepharose 4B-immobilized GST-Bmh1 and yeast extract expressing the above-mentioned fusion peptides. As shown in Fig. 3A, S235A and S238A substitutions abolished Bmh binding, whereas three other substitutions (Q234A, A236G, and S237A) retained Bmh binding ability. Interestingly, three additional Y239 substitutions (including two aromatic ones), Y239A, Y239W, and Y239F, disrupted Bmh binding (Fig. 3A), suggesting that the hydroxyl group of Tyr, and not its hydrophobicity, is important at position 239. None of the non-ADR1c mutations had an effect on Ser230 phosphorylation (Fig. 3B), suggesting the direct involvement of Tyr239, Ser235, and Ser238 in Bmh binding. The activities of the mutants were consistent with their Bmh binding profiles (Fig. 3C).

FIG 3.

Effects of Adr1 mutations on Bmh binding and Bmh-mediated regulation of the activity of Adr1. (A) GST-pulldown profile of Gal4DBD-Adr1 fusion variants in the context of the amino acid 226 to 250 region of Adr1. Pulldown was done using E. coli-expressed GST-Bmh1 and yeast cell extract (CE) expressing a Gal4DBD-Adr1 fusion peptide with the indicated amino acid substitutions. After washing, beads were boiled and used as the pellet (P) fraction. (B) The effects of various mutations on Ser230 phosphorylation were examined by Western blot analysis of the CE using anti-pSer230 antibody. Protein expression was monitored by Western blotting with anti-Gal4DBD antibody. Adr1 (amino acids 226 to 250) variants were expressed as an N-terminal Gal4DBD fusion protein. (C) β-Galactosidase activity was measured from the reporter plasmid pHZ18′ in BMH1 wild-type and bmh1-ts (BMH1-170) mutant strains expressing Gal4DBD-Adr1 fusion protein with the indicated mutations. Cultures of yeast were grown at 30°C. The bmh1-170 allele displays the same defect in Adr1-dependent gene expression at 30°C as at 37°C (44). The error bars represent the standard deviations in three separate experiments using three different biological replicates.

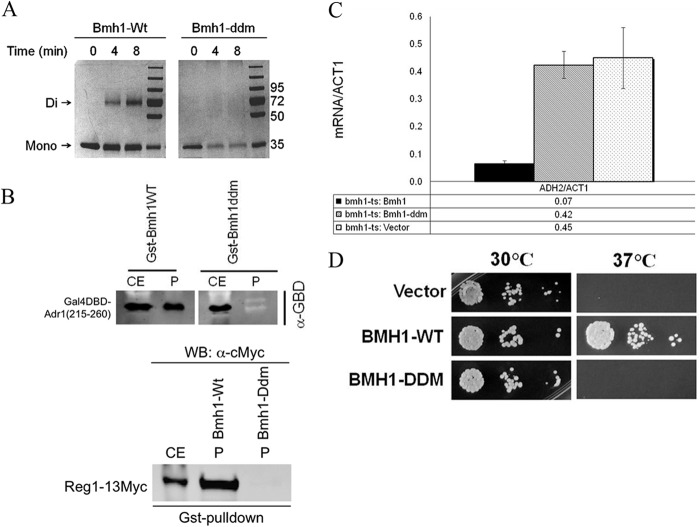

A dimerization-deficient Bmh is unable to bind Adr1.

We asked whether dimerization-deficient Bmh could bind and regulate Adr1 activity. Several approaches have been used to generate dimerization-deficient 14-3-3 proteins (1, 16–20, 22, 25, 63–67). One such dimer-incapable 14-3-3 protein, introduced by Tzivion et al. (17), contained 7 nonconservative amino acid replacements in the N-terminal region (E5, L12AE, Y82REKIE to K5, Q12QR, Q82RENIQ; mutated residues are underlined). To examine the interaction between dimerization-deficient Bmh and Adr1, we introduced seven mutations (D7, L14AE, Y87RSKIETE to R7, Q14NK, N87RSNIETQ) in the dimeric interface of Bmh1 to disrupt the dimer. To examine whether the mutations had disrupted dimer formation, glutaraldehyde cross-linking was performed using E. coli-expressed and purified wild-type (Bmh1-wt) and mutant (Bmh1-ddm) proteins. As shown in Fig. 4A, the mutations indeed disrupted the dimerization ability of Bmh. Furthermore, the appreciable amount of soluble mutant protein in purified fractions suggests that the mutant was structurally stable. GST pulldown assays using E. coli-expressed GST–Bmh1-wt and GST–Bmh-ddm and yeast extract containing Gal4DBD-Adr1 (amino acids 215 to 260) fusion peptides were performed to test the ability of the dimerization-deficient mutant to interact with Adr1. As shown in Fig. 4B, the dimerization-deficient Bmh1 was unable to bind Adr1, whereas Bmh1-wt bound as expected. Consistent with the binding results, Bmh1-ddm was unable to inhibit the transcriptional activity of Adr1 (Fig. 4C), and it was also unable to rescue the temperature-sensitive phenotype of bmh1-ts cells (Fig. 4D). Reg1 is a Bmh target (27), so we checked Bmh1-ddm binding to Reg1. Figure 4B shows that, like Adr1, Bmh1-ddm did not show any binding to Reg1. In conclusion, the results suggest that dimerization of yeast 14-3-3 is indispensable to bind Adr1 and inhibit its activity.

FIG 4.

A dimerization-deficient mutant of Bmh does not bind to and regulate transcriptional activity of Adr1. (A) Glutaraldehyde cross-linking profile of wild-type Bmh1 (Bmh1-Wt) and mutant Bmh1 (Bmh1-ddm). Proteins were visualized by Coomassie staining after cross-linking at 25°C for the indicated time using E. coli-expressed and purified proteins and 0.1% glutaraldehyde. Molecular mass standards are shown in kDa. The corresponding positions of monomer (Mono) and dimer (Di) Bmh are indicated. (B) GST pulldown results after immunoblotting with anti-Gal4DBD antibody. CE, cell extract; P, pellet. (Top) Pulldown results of GST-tagged wild-type and mutant Bmh1 with yeast-expressed Gal4DBD-Adr1 (amino acids 215 to 260). (Bottom) Binding of Reg1-13myc with wild-type and mutant GST-tagged Bmh1. (C) Activity assays of wild-type and mutant Bmh1 in BMH1 wild-type and bmh1-ts (bmh1-170) mutant strains. ADH2 mRNA was normalized to ACT1 mRNA. Cultures of yeast were grown at 30°C. The bmh1-170 allele displays the same defect in Adr1-dependent gene expression at 30°C as at 37°C (44). The error bars represent the standard deviations from three separate experiments using three different biological replicates. (D) Growth of bmh2Δ bmh1-ts cells expressing either wild-type or mutant protein at 30°C and 37°C. The empty vector was used as a negative control.

Probing of the Bmh binding region in Adr1 to understand the yeast 14-3-3 sequence motif(s).

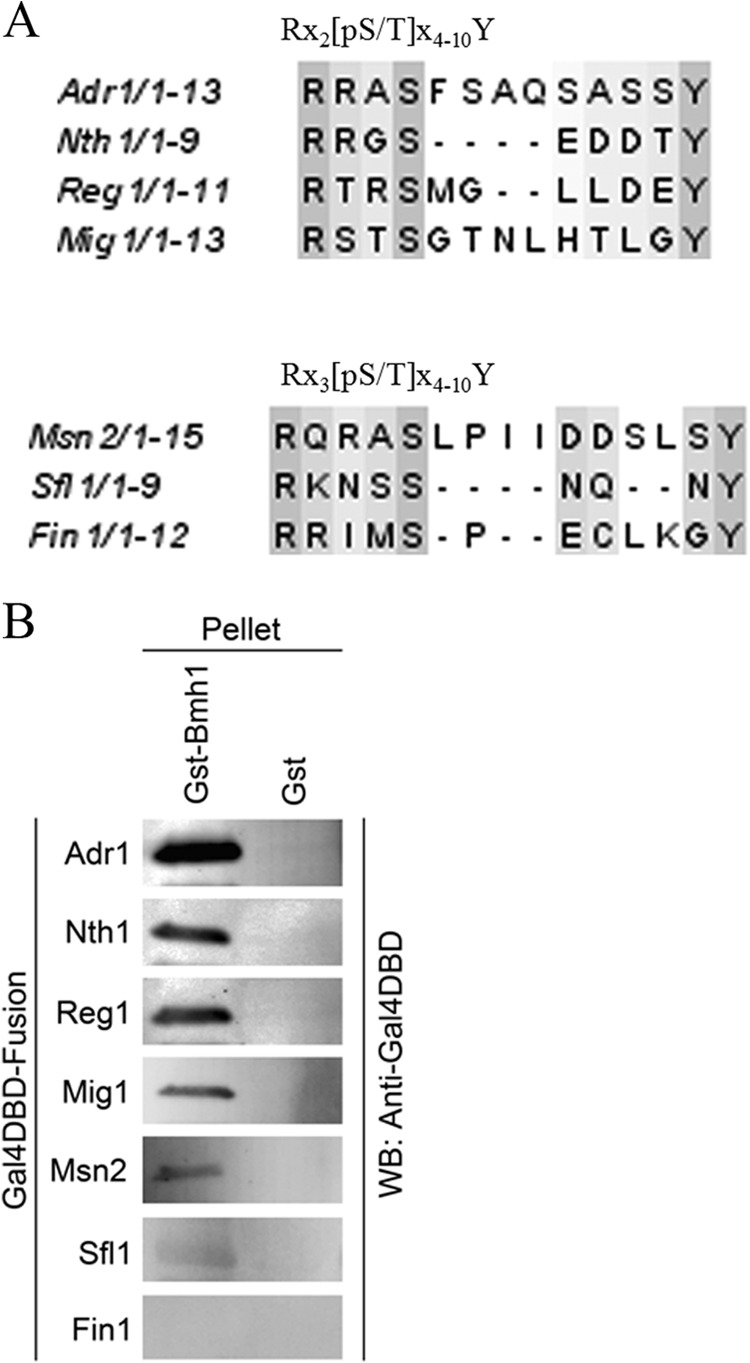

The novel mode of interaction between Bmh and Adr1 suggests that other yeast proteins might employ a similar strategy. We asked whether other yeast 14-3-3 targets also contain a Bmh binding motif containing a long stretch of amino acids between the phosphorylated Ser/Thr and a distal Tyr. A computational approach followed by a binding assay allowed us to identify other proteins with a similar motif that were bound by Bmh. First, we searched in the Saccharomyces Genome Database (SGD) (http://www.yeastgenome.org/) for yeast proteins sharing the sequence pattern RX2-3[pS/T]X4-10Y, where X is any amino acid and the subscript number denotes the number of residues allowed. We found 6,252 sequence hits representing 3,308 unique sequence entries after searching 5,886 proteins in SGD. Then, we asked how many of the 270 Bmh targets found by Kakiuchi et al. (68) were present in the SGD-extracted protein list. There were 204 Bmh targets with the sequence RX2-3[pS/T]X4-10Y. How significant is that enrichment of high-throughput Bmh targets with a consensus sequence pattern? To examine this, we used Fisher's exact test (see Table S3 in the supplemental material) and calculated a P value of 1.667e−11. By searching the database in PhosphoGRID (http://www.phosphogrid.org/) to find Bmh targets containing either phosphorylated Ser or Thr in the search motif, we found 56 matches from 43 different proteins that contain an Adr1-like consensus sequence (Table 2). These matches were grouped into two classes based on mode I and mode II motif characteristics, i.e., whether two or three residues were present between the N-terminal Arg and the phosphorylated residue. For yeast 14-3-3 targets other than Adr1, Bmh binding sites have been determined experimentally only in neutral trehalase, Nth1, and the protein kinase Yak1 (69, 70). In Nth1, Ser60 and Ser83 play equally important roles in Bmh binding and activity modulation (69). Interestingly, both sites lack +2 Pro, as in the Bmh binding site in Adr1. One of the two above-mentioned Bmh binding sites of Nth1 containing Ser83 was in our final list. In Yak1, autophosphorylated Ser335 plays an important role in Bmh binding, together with an unidentified site in the N terminus (70). Ser335 in Yak1 has a Pro at the +2 position and closely matches a mode II 14-3-3 motif. Interestingly, our list was enriched with several known 14-3-3 targets, although the Bmh recognition sequence is unknown. Surprisingly, only six of them share +2 Pro.

TABLE 2.

Adr1-like sequence pattern hits (SGD and PhosphoGRID)a

| Proteinb | Pattern |

Position (pS/T) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| RX2[pS/T]X4-10Y | RX3[pS/T]X4-10Y | ||

| AccI | RAVSVSDLSY | 1157 | |

| Cki1 | RPGSVRSYSVGY | 9 | |

| Nup60 | RRASATVPSAPY | 10 | |

| Pbs2 | RTSSTSSHY | 38 | |

| Nnk1 | RANSSDTIY | 65 | |

| Reg1 | RTRSMGLLDEY | 75 | |

| Nap1 | RLGSLVGQDSGY | 76 | |

| Nth1 | RRGSEDDTY | 83 | |

| Boi2 | RAKSTKRIY | 118 | |

| Cdc25-a | RKHSHPMKKY | 135 | |

| Cdc25-b | RRSSLNSLGNSAY | 151 | |

| Cdh1-a | RPSSNSVRGASLLTY | 193 | |

| Sfl1-a | RKNSSNQNY | 220 | |

| Mhp1 | RSKTESEVY | 222 | |

| Gip2 | RSKSVHFDQAAPVKY | 221 | |

| Frt1 | RRSSAGSFDY | 228 | |

| Adr1 | RRASFSAQSASSY | 230 | |

| Jsn1 | RSQSNASSIY | 275 | |

| Npr1 | RQSSIYSASRQPTGSY | 317 | |

| Bni5 | RKSSLNKY | 340 | |

| Atg13 | RANSFEPQSWQKKVY | 355 | |

| Mig1 | RSTSGTNLHTLGY | 381 | |

| Cyk3 | RARTLTKYDKHPRY | 391 | |

| Haa1-a | RSRSFIHHPANEY | 439 | |

| Ptp3 | RSHSQPIFTQY | 492 | |

| Kin82 | RTNSFVGTEEY | 501 | |

| Haa1-b | RSSSIDVNHRY | 506 | |

| Msb1 | RRDSAPDNQGIY | 538 | |

| Ydr186c | RSTSSNHFTNVY | 575 | |

| Mds3 | RLSSSGSLDNY | 618 | |

| Ksp1-a | RRGSTTTVQHSPGAY | 624 | |

| Mpt5 | RHFSLPANAY | 662 | |

| Fpk1 | RTNSFVGTEEY | 676 | |

| Kin1-a | RAVSDFVPGFAKPSY | 677 | |

| Pmd1 | RASSVSPPPVY | 785 | |

| Kin1-b | RAKSVGHARRESLKY | 791 | |

| Ksp1-b | RRLSMEQKFKNGVY | 827 | |

| Akl1 | RKGSSKRNNY | 884 | |

| Kin1-c | RKTSITETY | 986 | |

| Sec16-a | RTNSAISQSPVNY | 701 | |

| Kip2-a | RSDSINNNSRKNDTY | 88 | |

| Tco89-a | RVLTHDGTLDNDY | 52 | |

| Syt1-a | RRRSRTVDVFDY | 275 | |

| Sec16-b | RGHTSSISSY | 840 | |

| Sec16-c | RSSRTNSAISQSPVNY | 699 | |

| Msn4 | RKRKSITTIDPNNY | 558 | |

| Ksp1-c | RDFFTPPSVQHRY | 526 | |

| Msn2 | RQRASLPIIDDSLSY | 451 | |

| Syt1-b | RRSRTVDVFDY | 277 | |

| Sfl1-b | RKNSSNQNY | 221 | |

| Igd1 | RRKSSFKYEDFKKDIY | 175 | |

| Kip2-b | RRSDSINNNSRKNDTY | 88 | |

| Fin1 | RRIMSPECLKGY | 74 | |

| Tco89-b | RRVLTHDGTLDNDY | 52 | |

| Cdh1-b | RSRPSTVYGDRY | 50 | |

| Ask10 | RKSSSSTY | 627 | |

The table lists peptides sharing an Adr1-like sequence pattern (RX2-3[pS/T]X4-10Y) from a search in SGD with filtering by PhosphoGRID. Phosphorylated residues (Ser or Thr) are in boldface, and their positions are also indicated. Sequences that have +2 Pro are shaded.

a, b, and c indicate various peptides from the same protein.

To examine whether the matched sequences are Bmh targets, we performed GST pulldown assays using yeast-expressed Gal4DBD fusion proteins containing a matched sequence. To determine which sequences to examine in more detail, all of them were aligned using ClustalW2 (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/clustalw2/), and their phylogeny was determined using EBI Web Service (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/webservices/services/phylogeny/clustalw2_phylogeny_rest) to assign them to a family on the basis of sequence homology and the number of residues present between the phosphorylated residue and Tyr (see Fig. S3A and B in the supplemental material). GST-pulldown assays were performed on one known Bmh target representing each family in this phylogeny. We chose seven sequences, including Adr1, and the corresponding coding sequence (CDS) was cloned into a plasmid and expressed in yeast as a Gal4DBD fusion protein. Alignment of all seven is presented in Fig. 5A. As shown in Fig. 5B, six out of the seven sequences we tested showed Bmh binding. We conclude that many yeast 14-3-3 targets share a sequence feature that has a Tyr located outside the phosphomotif.

FIG 5.

Using the Adr1 Bmh1 binding motif to identify potential Bmh regions in other yeast proteins. (A) Alignment of seven sequences matching the Adr1 motif using ClustalW2 (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/clustalw2/). They were tested for Bmh binding as shown in panel B. (B) GST pulldown profiles of various peptides from the indicated protein. All the peptides were expressed as Gal4DBD fusions by replacing the amino acid 226 to 240 sequence of Adr1 from pGBDA14 (44). Pulldown was done using E. coli-expressed empty GST or GST-Bmh1 and yeast cell extract expressing a Gal4DBD fusion peptide. After washing, the beads were boiled, and the pellet fraction was analyzed by PAGE and Western blotting using anti Gal4DBD antisera.

DISCUSSION

14-3-3 proteins regulate numerous signaling processes by interacting with their phosphorylated targets (1–3). An unbiased phosphopeptide library search revealed two consensus 14-3-3 motifs, motif I (RXX-pS/T-XP) and motif II (RXXX-pS/T-XP) (7). The third motif (carboxy terminal, pS/TX1-2CO2H) has been observed in few 14-3-3 targets, e.g., plant H+-ATPase (8, 9). However, the Pro located at position +2 of the phosphorylation site occurs in only about one-half of known 14-3-3 binding motifs (71). The Bmh binding motif in Adr1 also lacks (+2) Pro. Ser is present at the +2 position and, surprisingly, replacement of that Ser with Pro reduced the binding. It is unknown whether yeast 14-3-3 or Bmh prefers Pro at the +2 position for other targets, because no unbiased interaction study is available for Bmh clients. In addition to Adr1, Nth1 (69, 72) and Yak1 (70) are the only yeast proteins with known Bmh binding sites. Interestingly, Nth1 does not have +2 Pro at the two Bmh binding sites (69) but Yak1 does have +2 Pro at the major site of autophosphorylation, where Bmh binds (70).

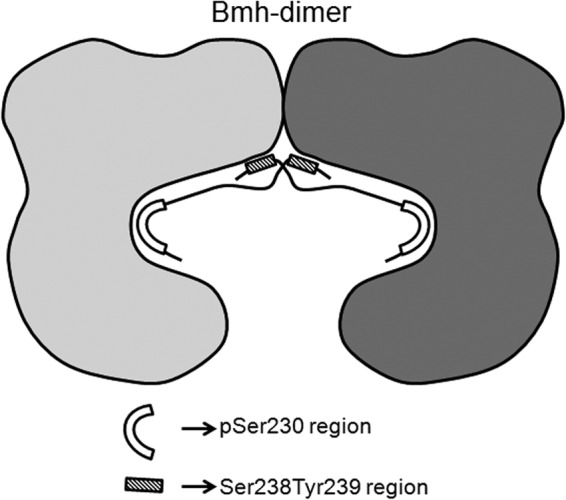

Another unusual aspect of the Bmh binding motif in Adr1 is the presence of distally located Ser and Tyr, which are essential for Bmh binding but not for phosphorylation. This is the first report documenting the involvement of residues outside the yeast 14-3-3 motif. However, the involvement of residues located distally from the phosphorylation site has been documented structurally and biochemically for a few targets in higher eukaryotes (73–75). Lys943 in the H+-ATPase is located 10 residues upstream of the 14-3-3 binding motif, and it has been shown to be involved in direct binding with the N-terminal region of the second 14-3-3 monomer. This interaction explains why dimerization of both 14-3-3 and the H+-ATPase target is indispensable for binding and activity regulation (75). Cdc25b may represent another example of a site with distally located interactions, but there is no structural study to corroborate that explanation. Although the evidence demonstrates that distally located Ser238 and Tyr239 play important roles in Bmh binding and regulation of the activity of Adr1 without affecting Ser230 phosphorylation, we do not yet know how these two residues influence Bmh binding. One possibility is that Adr1's interaction with Bmh resembles the interaction of H+-ATPase with 14-3-3ζ. If that is the case, the distal portion of Adr1's Bmh binding region would emerge from the target binding cleft of one monomer, and S238 and Y239 would interact with the nearest surface of the second 14-3-3 monomer, as shown in the proposed model (Fig. 6). This model assumes that a Bmh dimer would be important for efficient interaction with Adr1, and indeed, a dimerization-deficient Bmh was unable to bind Adr1. Structural studies need to be done to gain insight into the role of the distal region in binding and inhibition of Adr1 activity. An important recognition region located distal to the canonical 14-3-3 motif might help explain how these proteins distinguish target from nontarget proteins.

FIG 6.

Proposed model of Bmh-Adr1 interaction. The two monomers in the Bmh dimer are shown in different shades of gray. Ser230 and the distally located S238Y239 region are shown by different shaded shapes, and their involvement and possible position(s) in the cross-dimer interaction are also indicated.

An intriguing but unexplained observation is the presence of a second predicted 14-3-3 binding motif between residues 254 and 260 (44). We did not detect Bmh binding to this site. Because it is highly conserved in Adr1 orthologs in other yeast species (76), we speculate that phosphorylation of S258 may occur under some physiological conditions and promote Bmh binding and an additional avenue of regulation.

In conclusion, these studies provide a molecular understanding of the altered regulatory properties of ADR1c alleles first isolated by Ciriacy (58) and later expanded by Denis et al. (55). These alleles were the earliest demonstration, together with mutations in the GAL system, that eukaryotic gene regulation involved trans-acting regulatory factors. They are also the only genetically isolated and characterized mutations we are aware of that define a binding site for 14-3-3 proteins. The unusual ability to isolate such mutants was due to unique properties of the motif in providing stringent inhibition of gene expression when Bmh is bound to the site. Inhibition apparently occurs at a step after Adr1 has bound its cognate promoters (45), but the mechanism is unknown. Inhibition of a post-Adr1 binding step is also suggested by the observation that Adr1c activators show a reduced requirement for and enhanced recruitment of some transcriptional coactivators (77).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health, GM26079, to E.T.Y.

We thank other members of the laboratory for discussions and valuable suggestions and especially Ken Dombek for helping with the statistical analysis and S. Zheng for BMH plasmids.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 18 October 2013

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/EC.00240-13.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aitken A. 2006. 14-3-3 proteins: a historic overview. Semin. Cancer Biol. 16:162–172. 10.1016/j.semcancer.2006.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fu H, Subramanian RR, Masters SC. 2000. 14-3-3 proteins: structure, function, and regulation. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 40:617–647. 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.40.1.617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ferl RJ, Manak MS, Reyes MF. 2002. The 14-3-3s. Genome Biol. 3:REVIEWS3010. 10.1186/gb-2002-3-7-reviews3010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gardino AK, Smerdon SJ, Yaffe MB. 2006. Structural determinants of 14-3-3 binding specificities and regulation of subcellular localization of 14-3-3-ligand complexes: a comparison of the X-ray crystal structures of all human 14-3-3 isoforms. Semin. Cancer Biol. 16:173–182. 10.1016/j.semcancer.2006.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu D, Bienkowska J, Petosa C, Collier RJ, Fu H, Liddington R. 1995. Crystal structure of the zeta isoform of the 14-3-3 protein. Nature 376:191–194. 10.1038/376191a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Muslin AJ, Tanner JW, Allen PM, Shaw AS. 1996. Interaction of 14-3-3 with signaling proteins is mediated by the recognition of phosphoserine. Cell 84:889–897. 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81067-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yaffe MB, Rittinger K, Volinia S, Caron PR, Aitken A, Leffers H, Gamblin SJ, Smerdon SJ, Cantley LC. 1997. The structural basis for 14-3-3:phosphopeptide binding specificity. Cell 91:961–971. 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80487-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ganguly S, Weller JL, Ho A, Chemineau P, Malpaux B, Klein DC. 2005. Melatonin synthesis: 14-3-3-dependent activation and inhibition of arylalkylamine N-acetyltransferase mediated by phosphoserine-205. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102:1222–1227. 10.1073/pnas.0406871102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Borch J, Bych K, Roepstorff P, Palmgren MG, Fuglsang AT. 2002. Phosphorylation-independent interaction between 14-3-3 protein and the plant plasma membrane H+-ATPase. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 30:411–415. 10.1042/BST0300411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Henriksson ML, Francis MS, Peden A, Aili M, Stefansson K, Palmer R, Aitken A, Hallberg B. 2002. A nonphosphorylated 14-3-3 binding motif on exoenzyme S that is functional in vivo. Eur. J. Biochem. 269:4921–4929. 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2002.03191.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang B, Yang H, Liu YC, Jelinek T, Zhang L, Ruoslahti E, Fu H. 1999. Isolation of high-affinity peptide antagonists of 14-3-3 proteins by phage display. Biochemistry 38:12499–12504. 10.1021/bi991353h [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fuglsang AT, Visconti S, Drumm K, Jahn T, Stensballe A, Mattei B, Jensen ON, Aducci P, Palmgren MG. 1999. Binding of 14-3-3 protein to the plasma membrane H(+)-ATPase AHA2 involves the three C-terminal residues Tyr(946)-Thr-Val and requires phosphorylation of Thr(947). J. Biol. Chem. 274:36774–36780. 10.1074/jbc.274.51.36774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Waterman MJ, Stavridi ES, Waterman JL, Halazonetis TD. 1998. ATM-dependent activation of p53 involves dephosphorylation and association with 14-3-3 proteins. Nat. Genet. 19:175–178. 10.1038/542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Olayioye MA, Guthridge MA, Stomski FC, Lopez AF, Visvader JE, Lindeman GJ. 2003. Threonine 391 phosphorylation of the human prolactin receptor mediates a novel interaction with 14-3-3 proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 278:32929–32935. 10.1074/jbc.M302910200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ku NO, Liao J, Omary MB. 1998. Phosphorylation of human keratin 18 serine 33 regulates binding to 14-3-3 proteins. EMBO J. 17:1892–1906. 10.1093/emboj/17.7.1892 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Luo ZJ, Zhang XF, Rapp U, Avruch J. 1995. Identification of the 14.3.3 zeta domains important for self-association and Raf binding. J. Biol. Chem. 270:23681–23687. 10.1074/jbc.270.40.23681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tzivion G, Luo Z, Avruch J. 1998. A dimeric 14-3-3 protein is an essential cofactor for Raf kinase activity. Nature 394:88–92. 10.1038/27938 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ichimura T, Ito M, Itagaki C, Takahashi M, Horigome T, Omata S, Ohno S, Isobe T. 1997. The 14-3-3 protein binds its target proteins with a common site located towards the C-terminus. FEBS Lett. 413:273–276. 10.1016/S0014-5793(97)00910-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ichimura T, Uchiyama J, Kunihiro O, Ito M, Horigome T, Omata S, Shinkai F, Kaji H, Isobe T. 1995. Identification of the site of interaction of the 14-3-3 protein with phosphorylated tryptophan hydroxylase. J. Biol. Chem. 270:28515–28518. 10.1074/jbc.270.48.28515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gancedo JM. 1998. Yeast carbon catabolite repression. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 62:334–361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shen YH, Godlewski J, Bronisz A, Zhu J, Comb MJ, Avruch J, Tzivion G. 2003. Significance of 14-3-3 self-dimerization for phosphorylation-dependent target binding. Mol. Biol. Cell 14:4721–4733. 10.1091/mbc.E02-12-0821 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhou Y, Reddy S, Murrey H, Fei H, Levitan IB. 2003. Monomeric 14-3-3 protein is sufficient to modulate the activity of the Drosophila slowpoke calcium-dependent potassium channel. J. Biol. Chem. 278:10073–10080. 10.1074/jbc.M211907200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sluchanko NN, Artemova NV, Sudnitsyna MV, Safenkova IV, Antson AA, Levitsky DI, Gusev NB. 2012. Monomeric 14-3-3zeta has a chaperone-like activity and is stabilized by phosphorylated HspB6. Biochemistry 51:6127–6138. 10.1021/bi300674e [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sluchanko NN, Sudnitsyna MV, Seit-Nebi AS, Antson AA, Gusev NB. 2011. Properties of the monomeric form of human 14-3-3zeta protein and its interaction with tau and HspB6. Biochemistry 50:9797–9808. 10.1021/bi201374s [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tzivion G, Luo ZJ, Avruch J. 2000. Calyculin A-induced vimentin phosphorylation sequesters 14-3-3 and displaces other 14-3-3 partners in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 275:29772–29778. 10.1074/jbc.M001207200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van Heusden GP, Steensma HY. 2006. Yeast 14-3-3 proteins. Yeast 23:159–171. 10.1002/yea.1338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dombek KM, Kacherovsky N, Young ET. 2004. The Reg1-interacting proteins, Bmh1, Bmh2, Ssb1, and Ssb2, have roles in maintaining glucose repression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 279:39165–39174. 10.1074/jbc.M400433200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ichimura T, Kubota H, Goma T, Mizushima N, Ohsumi Y, Iwago M, Kakiuchi K, Shekhar HU, Shinkawa T, Taoka M, Ito T, Isobe T. 2004. Transcriptomic and proteomic analysis of a 14-3-3 gene-deficient yeast. Biochemistry 43:6149–6158. 10.1021/bi035421i [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mayordomo I, Regelmann J, Horak J, Sanz P. 2003. Saccharomyces cerevisiae 14-3-3 proteins Bmh1 and Bmh2 participate in the process of catabolite inactivation of maltose permease. FEBS Lett. 544:160–164. 10.1016/S0014-5793(03)00498-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carlson M. 1999. Glucose repression in yeast. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2:202–207. 10.1016/S1369-5274(99)80035-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Caspary F, Hartig A, Schuller HJ. 1997. Constitutive and carbon source-responsive promoter elements are involved in the regulated expression of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae malate synthase gene MLS1. Mol. Gen. Genet. 255:619–627. 10.1007/s004380050536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.De Vit MJ, Waddle JA, Johnston M. 1997. Regulated nuclear translocation of the Mig1 glucose repressor. Mol. Biol. Cell 8:1603–1618. 10.1091/mbc.8.8.1603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Johnston M, Flick JS, Pexton T. 1994. Multiple mechanisms provide rapid and stringent glucose repression of GAL gene expression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 14:3834–3841 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vallier LG, Carlson M. 1994. Synergistic release from glucose repression by mig1 and ssn mutations in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 137:49–54 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ostling J, Carlberg M, Ronne H. 1996. Functional domains in the Mig1 repressor. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16:753–761 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ostling J, Ronne H. 1998. Negative control of the Mig1p repressor by Snf1p-dependent phosphorylation in the absence of glucose. Eur. J. Biochem. 252:162–168. 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1998.2520162.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Treitel MA, Kuchin S, Carlson M. 1998. Snf1 protein kinase regulates phosphorylation of the Mig1 repressor in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18:6273–6280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Young ET, Kacherovsky N, Van Riper K. 2002. Snf1 protein kinase regulates Adr1 binding to chromatin but not transcription activation. J. Biol. Chem. 277:38095–38103. 10.1074/jbc.M206158200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Haurie V, Perrot M, Mini T, Jeno P, Sagliocco F, Boucherie H. 2001. The transcriptional activator Cat8p provides a major contribution to the reprogramming of carbon metabolism during the diauxic shift in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 276:76–85. 10.1074/jbc.M008752200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Young ET, Zhang C, Shokat KM, Parua PK, Braun KA. 2012. The AMP-activated protein kinase Snf1 regulates transcription factor binding, RNA polymerase II activity, and mRNA stability of glucose-repressed genes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 287:29021–29034. 10.1074/jbc.M112.380147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schuller HJ. 2003. Transcriptional control of nonfermentative metabolism in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Curr. Genet. 43:139–160. 10.1007/s00294-003-0381-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tachibana C, Yoo JY, Tagne JB, Kacherovsky N, Lee TI, Young ET. 2005. Combined global localization analysis and transcriptome data identify genes that are directly coregulated by Adr1 and Cat8. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25:2138–2146. 10.1128/MCB.25.6.2138-2146.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hahn S, Young ET. 2011. Transcriptional regulation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: transcription factor regulation and function, mechanisms of initiation, and roles of activators and coactivators. Genetics 189:705–736. 10.1534/genetics.111.127019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Parua PK, Ratnakumar S, Braun KA, Dombek KM, Arms E, Ryan PM, Young ET. 2010. 14-3-3 (Bmh) proteins inhibit transcription activation by Adr1 through direct binding to its regulatory domain. Mol. Cell. Biol. 30:5273–5283. 10.1128/MCB.00715-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Braun KA, Parua PK, Dombek KM, Miner GE, Young ET. 2013. 14-3-3 (Bmh) proteins regulate combinatorial transcription following RNA polymerase II recruitment by binding at Adr1-dependent promoters in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 33:712–724. 10.1128/MCB.01226-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cross FR. 1997. ‘Marker swap' plasmids: convenient tools for budding yeast molecular genetics. Yeast 13:647–653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Knop M, Siegers K, Pereira G, Zachariae W, Winsor B, Nasmyth K, Schiebel E. 1999. Epitope tagging of yeast genes using a PCR-based strategy: more tags and improved practical routines. Yeast 15:963–972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fields S, Song O. 1989. A novel genetic system to detect protein-protein interactions. Nature 340:245–246. 10.1038/340245a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Orr-Weaver TL, Szostak JW. 1983. Yeast recombination: the association between double-strand gap repair and crossing-over. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 80:4417–4421. 10.1073/pnas.80.14.4417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Szostak JW, Orr-Weaver TL, Rothstein RJ, Stahl FW. 1983. The double-strand-break repair model for recombination. Cell 33:25–35. 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90331-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Uetz P, Giot L, Cagney G, Mansfield TA, Judson RS, Knight JR, Lockshon D, Narayan V, Srinivasan M, Pochart P, Qureshi-Emili A, Li Y, Godwin B, Conover D, Kalbfleisch T, Vijayadamodar G, Yang M, Johnston M, Fields S, Rothberg JM. 2000. A comprehensive analysis of protein-protein interactions in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nature 403:623–627. 10.1038/35001009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Collart MA, Oliviero S. 2001. Preparation of yeast RNA. Curr. Protoc. Mol. Biol. Chapter 13:Unit 13.12. 10.1002/0471142727.mb1312s23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Guarente L. 1983. Yeast promoters and lacZ fusions designed to study expression of cloned genes in yeast. Methods Enzymol. 101:181–191. 10.1016/0076-6879(83)01013-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Parua PK, Mondal A, Parrack P. 2010. HflD, an Escherichia coli protein involved in the lambda lysis-lysogeny switch, impairs transcription activation by lambdaCII. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 493:175–183. 10.1016/j.abb.2009.10.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Denis CL, Fontaine SC, Chase D, Kemp BE, Bemis LT. 1992. ADR1c mutations enhance the ability of ADR1 to activate transcription by a mechanism that is independent of effects on cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase phosphorylation of Ser-230. Mol. Cell. Biol. 12:1507–1514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cherry JR, Johnson TR, Dollard C, Shuster JR, Denis CL. 1989. Cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase phosphorylates and inactivates the yeast transcriptional activator ADR1. Cell 56:409–419. 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90244-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Denis CL, Gallo C. 1986. Constitutive RNA synthesis for the yeast activator ADR1 and identification of the ADR1-5c mutation: implications in posttranslational control of ADR1. Mol. Cell. Biol. 6:4026–4030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ciriacy M. 1979. Isolation and characterization of further cis- and trans-acting regulatory elements involved in the synthesis of glucose-repressible alcohol dehydrogenase (ADHII) in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Gen. Genet. 176:427–431. 10.1007/BF00333107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ratnakumar S, Kacherovsky N, Arms E, Young ET. 2009. Snf1 controls the activity of adr1 through dephosphorylation of Ser230. Genetics 182:735–745. 10.1534/genetics.109.103432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hook SS, Kemp BE, Means AR. 1999. Peptide specificity determinants at P-7 and P-6 enhance the catalytic efficiency of Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase I in the absence of activation loop phosphorylation. J. Biol. Chem. 274:20215–20222. 10.1074/jbc.274.29.20215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dombek KM, Camier S, Young ET. 1993. ADH2 expression is repressed by REG1 independently of mutations that alter the phosphorylation of the yeast transcription factor ADR1. Mol. Cell. Biol. 13:4391–4399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cherry JR, Denis CL. 1989. Overexpression of the yeast transcriptional activator ADR1 induces mutation of the mitochondrial genome. Curr. Genet. 15:311–317. 10.1007/BF00419910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Messaritou G, Grammenoudi S, Skoulakis EM. 2010. Dimerization is essential for 14-3-3zeta stability and function in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 285:1692–1700. 10.1074/jbc.M109.045989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Powell DW, Rane MJ, Joughin BA, Kalmukova R, Hong JH, Tidor B, Dean WL, Pierce WM, Klein JB, Yaffe MB, McLeish KR. 2003. Proteomic identification of 14-3-3zeta as a mitogen-activated protein kinase-activated protein kinase 2 substrate: role in dimer formation and ligand binding. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23:5376–5387. 10.1128/MCB.23.15.5376-5387.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sluchanko NN, Chernik IS, Seit-Nebi AS, Pivovarova AV, Levitsky DI, Gusev NB. 2008. Effect of mutations mimicking phosphorylation on the structure and properties of human 14-3-3zeta. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 477:305–312. 10.1016/j.abb.2008.05.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sluchanko NN, Sudnitsyna MV, Chernik IS, Seit-Nebi AS, Gusev NB. 2011. Phosphomimicking mutations of human 14-3-3zeta affect its interaction with tau protein and small heat shock protein HspB6. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 506:24–34. 10.1016/j.abb.2010.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Woodcock JM, Murphy J, Stomski FC, Berndt MC, Lopez AF. 2003. The dimeric versus monomeric status of 14-3-3zeta is controlled by phosphorylation of Ser58 at the dimer interface. J. Biol. Chem. 278:36323–36327. 10.1074/jbc.M304689200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kakiuchi K, Yamauchi Y, Taoka M, Iwago M, Fujita T, Ito T, Song SY, Sakai A, Isobe T, Ichimura T. 2007. Proteomic analysis of in vivo 14-3-3 interactions in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochemistry 46:7781–7792. 10.1021/bi700501t [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Veisova D, Macakova E, Rezabkova L, Sulc M, Vacha P, Sychrova H, Obsil T, Obsilova V. 2012. Role of individual phosphorylation sites for the 14-3-3-protein-dependent activation of yeast neutral trehalase Nth1. Biochem. J. 443:663–670. 10.1042/BJ20111615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lee P, Paik SM, Shin CS, Huh WK, Hahn JS. 2011. Regulation of yeast Yak1 kinase by PKA and autophosphorylation-dependent 14-3-3 binding. Mol. Microbiol. 79:633–646. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07471.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Johnson C, Crowther S, Stafford MJ, Campbell DG, Toth R, MacKintosh C. 2010. Bioinformatic and experimental survey of 14-3-3-binding sites. Biochem. J. 427:69–78. 10.1042/BJ20091834 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Macakova E, Kopecka M, Kukacka Z, Veisova D, Novak P, Man P, Obsil T, Obsilova V. 2013. Structural basis of the 14-3-3 protein-dependent activation of yeast neutral trehalase Nth1. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1830:4491–4499. 10.1016/j.bbagen.2013.05.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Uchida S, Kubo A, Kizu R, Nakagama H, Matsunaga T, Ishizaka Y, Yamashita K. 2006. Amino acids C-terminal to the 14-3-3 binding motif in CDC25B affect the efficiency of 14-3-3 binding. J. Biochem. 139:761–769. 10.1093/jb/mvj079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Uhart M, Iglesias AA, Bustos DM. 2011. Structurally constrained residues outside the binding motif are essential in the interaction of 14-3-3 and phosphorylated partner. J. Mol. Biol. 406:552–557. 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.12.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ottmann C, Marco S, Jaspert N, Marcon C, Schauer N, Weyand M, Vandermeeren C, Duby G, Boutry M, Wittinghofer A, Rigaud JL, Oecking C. 2007. Structure of a 14-3-3 coordinated hexamer of the plant plasma membrane H+-ATPase by combining X-ray crystallography and electron cryomicroscopy. Mol. Cell 25:427–440. 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.12.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Parua PK, Ryan PM, Trang K, Young ET. 2012. Pichia pastoris 14-3-3 regulates transcriptional activity of the methanol inducible transcription factor Mxr1 by direct interaction. Mol. Microbiol. 85:282–298. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2012.08112.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ratnakumar S, Young ET. 2010. Snf1 dependence of peroxisomal gene expression is mediated by Adr1. J. Biol. Chem. 285:10703–10714. 10.1074/jbc.M109.079848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.James P, Halladay J, Craig EA. 1996. Genomic libraries and a host strain designed for highly efficient two-hybrid selection in yeast. Genetics 144:1425–1436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lottersberger F, Rubert F, Baldo V, Lucchini G, Longhese MP. 2003. Functions of Saccharomyces cerevisiae 14-3-3 proteins in response to DNA damage and to DNA replication stress. Genetics 165:1717–1732 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.