Abstract

Legionella pneumophila, the causative agent of Legionnaires' disease, is an intracellular human pathogen that utilizes the Icm/Dot type IVB secretion system to translocate a large repertoire of effectors into host cells. To find coregulated effectors, we performed a bioinformatic genomic screen with the aim of identifying effector-encoding genes containing putative CsrA regulatory elements. The regulation of these genes by the LetAS-RsmYZ-CsrA regulatory cascade was experimentally validated by examining their levels of expression in deletion mutants of relevant regulators and by site-directed mutagenesis of the putative CsrA sites. These analyses resulted in the identification of 26 effector-encoding genes regulated by the LetAS-RsmYZ-CsrA regulatory cascade, all of which were expressed at higher levels during the stationary phase. To determine if any of these effectors is involved in modulating the secretory pathway, they were overexpressed in wild-type yeast as well as in a yeast sec22 deletion mutant, which encodes an R-SNARE that participates in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER)-Golgi trafficking. This examination identified many novel LetAS-RsmYZ-CsrA regulated effectors which are involved in this process. To further characterize the role of these 26 effectors in vesicular trafficking, they were examined in yeast arf and arl deletion mutants, which encode small GTPases that regulate ER-Golgi trafficking. This analysis revealed that the effectors examined manipulate different processes of the secretory pathway. Collectively, our results demonstrate that several of the L. pneumophila effectors which are coregulated in the bacterial cell are involved in the modulation of the same eukaryotic pathway.

INTRODUCTION

Legionella pneumophila is an opportunistic human pathogen that multiplies within alveolar macrophages and causes a severe pneumonia known as Legionnaires' disease. Human disease occurs when aerosolized L. pneumophila is inhaled from man-made or natural freshwater reservoirs harboring the bacteria (1–3). In the environment, L. pneumophila multiplies in many different protozoan cells that serve as their training ground for pathogenesis (4–6). In order to establish a replicative niche inside eukaryotic cells, L. pneumophila modulates host-cell functions by delivering about 300 effector proteins through the Icm/Dot type IVB secretion system (reviewed in references 7, 8, 9, and 10). Most of these effectors have no homologues in the GenBank, but several of them are homologous to eukaryotic proteins or contain eukaryotic protein motifs (11–13).

The effectors that participate in high numbers in the establishment of the Legionella-containing vacuole (LCV) are expected to be regulated at the level of gene expression in order to coordinate a successful infection. To date, three regulatory systems have been shown to directly regulate the expression of effector-encoding genes: (i) the PmrAB two-component system was shown to directly activate the expression of about 40 effector-encoding genes (14, 15); (ii) the CpxRA two-component system was shown to directly activate or repress the expression of several effector-encoding genes as well as icm/dot genes (16, 17); and (iii) the LetAS-RsmYZ-CsrA regulatory cascade, which includes the LetAS two-component system, the two small RNAs (sRNAs) RsmY and RsmZ, and the posttranscriptional repressor CsrA, was shown to posttranscriptionally repress the translation of three effector-encoding genes (18–20). Furthermore, these three regulatory systems were shown to be part of a regulatory network that regulates the expression of effector-encoding genes (21). Beside these three regulatory systems, other regulators such as RpoS, LqsR, and ArgR were suggested to be involved in the regulation of effector-encoding genes (22–24), however, none of them was shown to directly regulate the expression of these genes.

Components similar to the ones identified in the L. pneumophila LetAS-RsmYZ-CsrA regulatory cascade were described before in many Gram-negative bacteria, and these components function similarly in all of them (25–27). In L. pneumophila, this regulatory cascade was found to function as follows: during the exponential phase, the CsrA repressor binds to the mRNA of its target genes and represses their translation. Upon entry into the stationary phase, the sensor kinase LetS is activated and phosphorylates LetA, its cognate response regulator. LetA thus binds and activates the expression of the two sRNAs RsmY and RsmZ; these sRNAs contain several CsrA binding sites (AGGA, ATGGA, ACGGA, and AGGGA) and, when expressed, sequester multiple CsrA molecules from their target mRNAs, thus releasing the CsrA repression from its target mRNAs. This leads to high levels of expression of the corresponding proteins at the stationary phase (18–20, 28–30). Examination of mutants lacking different components of this regulatory cascade indicated that LetA is required for intracellular multiplication in amoeba, and the same result was obtained with a double-deletion mutant in the two genes encoding RsmY and RsmZ (19, 31, 32). The gene encoding CsrA was found to be essential for L. pneumophila; however, mutants containing a reduced level of this regulator were shown to be attenuated for intracellular multiplication in amoeba (29, 33).

The regulation of subsets of effectors by the three regulatory systems described above most likely results in groups of effectors which are coordinated at the level of gene expression and might also function together in the host cell. The LCV establishment was shown to be dependent on numerous effectors (8, 34, 35); these effectors modulate many host cell factors involved in vesicular trafficking such as Rab1, Arf1, Sec22b, Sar1, and others (36–39). In addition, effectors involved in the modulation of these factors (such as RalF, SidM/DrrA, and many others) were shown to translocate into host cells very early during infection (39, 40). The members of the subset of effectors regulated by the LetAS-RsmYZ-CsrA cascade are expected to be expressed at the end of an infection cycle (the equivalent of the stationary phase) and probably are translocated into host cells and perform their function early during the next infection, when the LCV is being established.

Currently, the group of effectors regulated by the LetAS-RsmYZ-CsrA cascade consists of three effectors (VipA, LegC7/YlfA, and LegC2/YlfB), all of which were shown to be involved in vesicular trafficking. The VipA effector was identified in a screen looking for proteins that subvert trafficking in yeast, and it was later shown to bind actin in vitro and to directly polymerize actin microfilaments. During macrophage infection, VipA was found to be associated with actin patches and early endosomes, suggesting a role in modulating organelle trafficking (41, 42). The paralogous effectors LegC7/YlfA and LegC2/YlfB were identified in a screen looking for proteins that caused a lethal effect on yeast growth, and they were later shown to be involved in vesicular trafficking and to be located within large structures that colocalized with anti-KDEL antibodies in mammalian cells (12, 43). The fact that all the effectors known to be regulated by the LetAS-RsmYZ-CsrA cascade were found to be involved in vesicular trafficking might indicate that additional effectors regulated by this cascade are involved in the same process.

The goal of this research was to identify the group of effectors which are regulated by the LetAS-RsmYZ-CsrA cascade and to find if coregulated effectors also modulate similar eukaryotic pathways. To achieve this goal, we performed a bioinformatic genomic screen with the aim of identifying genes containing putative CsrA regulatory elements. Examination of the genes that were found in the screen resulted in the identification of 26 effectors regulated by the LetAS-RsmYZ-CsrA regulatory cascade. Further work revealed that most of them are involved in modulating the evolutionarily conserved secretory pathway.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial and yeast strains, plasmids, and primers.

The L. pneumophila wild-type strain used in this work was JR32, a streptomycin-resistant, restriction-negative mutant of L. pneumophila Philadelphia-1, which is a wild-type strain in terms of intracellular growth (44). In addition, mutant strains derived from JR32 which contain a kanamycin (Km) cassette instead of the icmT gene (GS3011) (45), the letA gene (OG2001) (31), and the rsmY gene (MR-rsmY) (19) and a double-deletion mutant containing a Km cassette instead of the rsmY gene and a gentamicin cassette instead of the rsmZ gene (MR-rsmYZ) (19) were used. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae wild-type strain used in this work was BY4741 (MATa his3Δ leu2Δ met15Δ ura3Δ) (46). In addition, deletion mutants derived from BY4741 (a kind gift from Martin Kupiec, Tel Aviv University) which contain a G418 resistance cassette instead of the arf1, arf2, arl1, arl3, and sec22 genes (47) were used. The plasmids and primers used in this work are listed in Table S2 and Table S3 in the supplemental material.

Construction of lacZ translational fusions.

To generate lacZ translational fusions, the regulatory regions of the 62 genes examined were amplified by PCR using the primers listed in Table S3 in the supplemental material. Genes for which the predicted CsrA site was found to be located upstream from the ATG start codon, the translational fusions contain the first seven codons of the gene fused to the lacZ gene. When the predicted CsrA site was found to be located downstream from the first ATG, the predicted CsrA site was included in the fusion as well as seven or eight nucleotides downstream of it in such a way that an in-frame lacZ fusion was formed. The resulting PCR products were digested with BamHI and EcoRI (or with only EcoRI if a BamHI site was present in the regulatory region), cloned into pGS-lac-02, and sequenced. The list of lacZ fusion plasmids constructed is presented in Table S2 in the supplemental material. The β-galactosidase assays were performed as described elsewhere (48).

Construction of plasmids containing an IPTG-inducible LetA and CsrA.

The plasmids containing the L. pneumophila letA and csrA genes under the control of Ptac (pMR-Ptac-csrA-207 and pMR-Ptac-letA-207, respectively) were described before (19). These plasmids were digested with XbaI and EheI, and the fragments containing Ptac-csrA together with the lacI gene, or Ptac-letA together with the lacI gene, were cloned into the plasmids containing the lacZ translational fusions of the mavT, mavQ, and lpg2461 genes, resulting in the plasmids listed in Table S2 in the supplemental material. These plasmids were introduced to different L. pneumophila strains and examined using different concentrations of IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside) (see Results).

Site-directed mutagenesis of predicted CsrA regulatory elements.

To generate substitutions in the putative CsrA regulatory elements in the regulatory regions of the cegC1, legA7, ravH, mavT, ravR, lem11, legL3, mavQ, lpg0375, lpg0963, lpg1273, cegL2, and lpg2461 genes, site-directed mutagenesis was performed by the PCR overlap extension approach (49) using a method similar to one previously described (15). In genes where the mutations were constructed in putative CsrA sites located upstream from the ATG start codon, the pair of G nucleotides of the CsrA consensus was changed to a pair of C nucleotides; in genes where the putative CsrA site mutated was located downstream from the ATG start codon, the mutations were constructed such that no amino acid was changed (synonymous mutations). The primers used for mutagenesis are listed in Table S3 in the supplemental material, and the plasmids resulting from the site-directed mutagenesis are listed in Table S2 in the supplemental material.

Construction and examination of cyaA fusions and plasmids for expression in yeast.

The pMMB-cyaA-C vector, described before (15), was used to construct CyaA fusions. In addition, a yeast expression vector was constructed to contain the pUC-18 polylinker, at the same reading frame as that present in pMMB-cyaA-C. pUC-18 containing the Km cassette inside its polylinker was digested with EcoRI and PvuII and cloned into pGREG523 (50), and the product was digested with EcoRI and HincII to generate pGREG523-Km. This vector was used to construct effector C-terminal fusions to the 13× myc tag regulated by the yeast GAL1 promoter.

The L. pneumophila genes examined for translocation and/or lethal effect on yeast growth were amplified by PCR using a pair of primers containing suitable restriction sites (see Table S3 in the supplemental material). The PCR products were subsequently digested with the relevant enzymes and cloned into pUC-18. The insertions of the resulting plasmids were sequenced to verify that no mutations were introduced during the PCR. The insertions were then digested with the same enzymes and cloned into the CyaA and/or the yeast expression vectors; the plasmids generated are listed in Table S2 in the supplemental material. The translocation assays and yeast lethality assays were performed as described before (51).

RESULTS

Numerous L. pneumophila genes harbor putative CsrA regulatory elements.

Information available from studies of many bacterial species as well as L. pneumophila (19, 25–27) indicated that the CsrA regulatory element consists of the sequence AGGA or ABGGA (B = C, T, or G) and that these sites are usually located in close proximity to the ATG start codon of the regulated genes, as part of their mRNA (52). Most of the genes known to be repressed by CsrA contain at least two CsrA sites, one of which usually overlaps the ribosomal binding site (26, 53). To find L. pneumophila genes potentially regulated by CsrA, a genomic search was performed aimed at identifying regulatory regions that contain the following features: (i) at least two putative CsrA sites are present; (ii) at least two of the putative CsrA sites are located less than 50 nucleotides apart; and (iii) one of the putative CsrA sites also constitutes the putative ribosomal binding site of the corresponding gene. This screen resulted in the identification of numerous genes potentially regulated by CsrA. We focused our study on 62 of them (see Table S1 in the supplemental material) grouped according to the following criteria: (i) genes encoding effector proteins (47 genes); (ii) genes encoding regulators (11 genes); and (iii) genes encoding proteins involved in flagellum biosynthesis (4 genes).

It was previously shown that three L. pneumophila effector-encoding genes (legC7-ylfA, legC2-ylfB, and vipA) are regulated by the LetA-RsmYZ-CsrA cascade (19). When the level of expression of these genes was examined in a letA deletion mutant, a strong reduction in their level of expression was obtained at the stationary phase (19). This reduction occurs because the expression of the RsmY and RsmZ sRNAs was not activated in the letA deletion mutant and consequently CsrA continued to repress the mRNA of its target genes also during the stationary phase (19). To examine the genes identified in the bioinformatic screen described above, we constructed translational lacZ fusions for all the 62 genes identified and their level of expression was examined in the L. pneumophila wild-type and letA deletion mutant strains at the stationary phase, as described below.

Numerous L. pneumophila effector-encoding genes are regulated by the LetA-RsmYZ-CsrA regulatory cascade.

The 47 effector-encoding genes identified in the screen included the 3 effector-encoding genes (legC7-ylfA, legC2-ylfB, and vipA) that were shown before to be regulated by the LetA-RsmYZ-CsrA cascade (19) and those encoding 42 known effectors as well as two open reading frames (ORFs) that were not shown before to encode effectors, and their translocation into host cells was validated in this study (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). These two novel effectors (lpg1925 and lpg2324) were designated CegL1 and CegL2, respectively, for coregulated with effector genes by the LetA-RsmYZ-CsrA cascade.

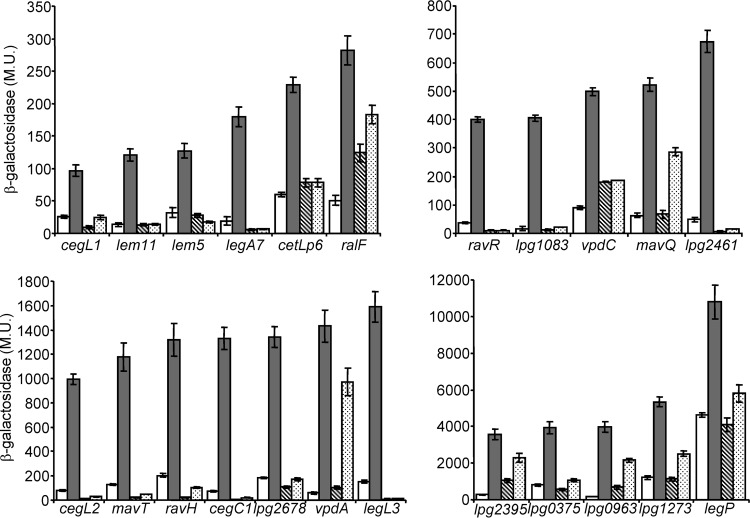

Examination of translational lacZ fusions constructed for the 44 effectors (see Table S1 in the supplemental material) described above (42 known effectors and the 2 newly identified effectors) indicated that 23 of them had a reduced (between 2- and 242-fold) level of expression in the letA deletion mutant in comparison to the wild-type strain at the stationary phase (Fig. 1). To further validate the regulation of these effectors by the LetA-RsmYZ-CsrA regulatory cascade, their level of expression was also examined in the rsmYZ double-deletion mutant, and a reduction in their level of expression was obtained in this mutant as well (Fig. 1). In addition, as expected from genes regulated by the LetA-RsmYZ-CsrA cascade (see the introduction), all these genes were found to have a higher level of expression at the stationary phase than at the exponential phase (Fig. 1). These results indicate that 26 L. pneumophila effectors are regulated by the LetA-RsmYZ-CsrA regulatory cascade, which directs their higher level of expression at the stationary phase.

FIG 1.

Numerous L. pneumophila effector-encoding genes are activated at the stationary phase in a LetA-RsmYZ-CsrA-dependent manner. The expression of effector translational lacZ fusions (the effectors examined are indicated below the bars) was examined in the wild-type strain (JR32) at the exponential phase (white bars) and at the stationary phase (gray bars), in the letA deletion mutant (OG2001) at the stationary phase (diagonal striped bars), and in the rsmYZ double-deletion mutant (MR-rsmYZ) at the stationary phase (dotted bars). β-Galactosidase activity was measured as described in Materials and Methods. Data (expressed in Miller units [M.U.]) are the averages ± standard deviations (error bars) of the results of at least three different experiments. The effector-encoding genes were divided according to their levels of expression.

Regulators and flagellum-related genes are also regulated by the LetA-RsmYZ-CsrA cascade.

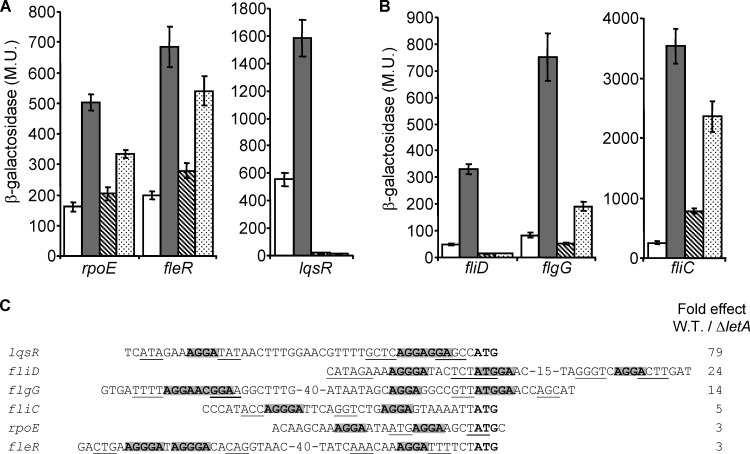

Two additional groups of genes were examined for regulation by the LetA-RsmYZ-CsrA cascade: genes encoding regulators and genes encoding proteins involved in flagellum biosynthesis. The motivation to examine regulators of gene expression comes from the observation that the known regulators of L. pneumophila effectors form a regulatory network (see the introduction). Therefore, it was interesting to examine whether the LetA-RsmYZ-CsrA cascade controls the expression of regulators that might in turn regulate the expression of other effector-encoding genes, thus expanding the regulatory network of the effectors. Moreover, it was previously shown in several bacterial species that CsrA usually functions as a regulator of regulators (26, 54). The incentive for examining genes that encode proteins involved in flagellum biosynthesis comes from the correlation between the effector and flagellum gene expression (55, 56) and from the fact that the LetA response regulator was first identified in a screen examining differential expression of flagella (18). Using analyses similar to the ones described above, 11 regulators and four flagellum-related genes were examined (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). Three genes encoding regulators (rpoE, lqsR, and fleR) and three genes encoding proteins involved in flagellum biosynthesis (fliC, fliD, and flgG) were found to be regulated by the LetA-RsmYZ-CsrA cascade (Fig. 2A and B, respectively). It should be noted that FleR and LqsR were previously suggested to be involved in flagellum gene expression (57, 58) and that LqsR was also suggested to be involved in the regulation of effector-encoding genes (58). These results show that, in addition to directly contributing to the regulation of effector-encoding genes, the LetA-RsmYZ-CsrA cascade also controls the expression of regulators that by themselves might regulate the expression of other effector-encoding genes.

FIG 2.

L. pneumophila genes encoding regulators and flagellum biosynthesis proteins are activated at the stationary phase in a LetA-RsmYZ-CsrA-dependent manner. The expression of translational lacZ fusions of genes encoding regulators (A) and genes encoding flagellum-related proteins (B) was examined in the wild-type strain (JR32) at the exponential phase (white bars) and at the stationary phase (gray bars), in the letA deletion mutant (OG2001) at the stationary phase (diagonal striped bars), and in the rsmYZ double-deletion mutant (MR-rsmYZ) at the stationary phase (dotted bars). β-Galactosidase activity was measured as described in Materials and Methods. Data (expressed in Miller units [M.U.]) are the averages ± standard deviations (error bars) of the results of at least three different experiments. The genes were divided according to their levels of expression. (C) The regulatory regions of regulators and flagellum-related genes that were found to be regulated by the LetA-RsmYZ-CsrA regulatory cascade. The nucleotides representing the putative CsrA consensus are in boldface and gray background, small inverted repeats surrounding the putative CsrA sites are underlined, and the ATG start codon is in bold. The genes are indicated on the left, and the fold reduction in the level of expression of each gene between the letA deletion mutant and the wild-type (W.T.) strain at the stationary phase is indicated on the right.

Properties of the L. pneumophila CsrA regulatory element.

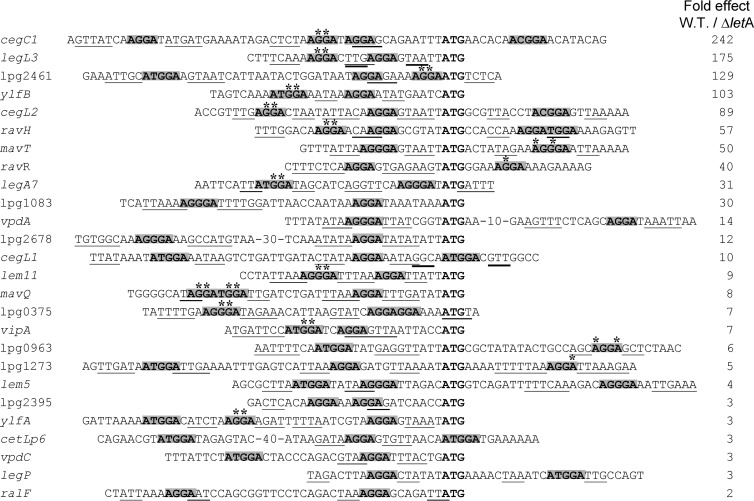

The analyses described above resulted in the identification of 32 genes regulated by the LetA-RsmYZ-CsrA cascade (26 effector-encoding genes, 3 genes encoding regulators, and 3 flagellum-related genes). The majority (18) of these genes contain two putative CsrA sites, and the rest contain 3 to 6 CsrA sites (Fig. 2C and 3; see also Table S1 in the supplemental material). In total, these 32 genes harbor 86 putative CsrA regulatory elements, 53 of which contain an adenosine nucleotide directly upstream from the CsrA consensus sequence (AGGA, ATGGA, ACGGA, or AGGGA). This observation might suggest that adenosine is the preferred nucleotide at this position. Another interesting observation was that the CsrA regulatory element ACGGA was rarely found in the genes identified. Of the 86 potential CsrA sites detected, only four sites, in four different genes (cegC1, cetLp6, cegL2, and flgG), were found to harbor this sequence. In addition, these four genes contain two or three additional CsrA sites, which suggests that, even in these genes, the ACGGA site might not be functional. In correlation with this finding, when we examined the L. pneumophila RsmY and RsmZ sRNAs, it was found that, of the 11 potential CsrA sites present in these two sRNAs, only one potential site consists of the sequence ACGGA (data not shown). On the other hand, the most abundant CsrA site was found to be AGGA; this site appeared in 50 of the 86 potential CsrA sites detected, and 32 of these sites are composed of the sequence AAGGA. These results further refine our understanding of the CsrA consensus used by the L. pneumophila CsrA posttranscriptional repressor and indicate that there is a preference for the use of an AGGA site whereas the ACGGA site is rarely used.

FIG 3.

The putative CsrA regulatory elements of effector-encoding genes. The regulatory regions of the effectors found to be regulated by the LetA-RsmYZ-CsrA cascade are presented. The nucleotides representing the putative CsrA consensus are in boldface and gray background, small inverted repeats surrounding the putative CsrA sites are underlined, the ATG start codon is in bold, and the nucleotides that were mutated are marked with asterisks. The effector designations are indicated on the left, and the fold reduction in the level of expression of each effector between the letA deletion mutant and the wild-type strain at the stationary phase is indicated on the right.

Different components of the LetA-RsmYZ-CsrA regulatory cascade similarly affect the expression of effectors.

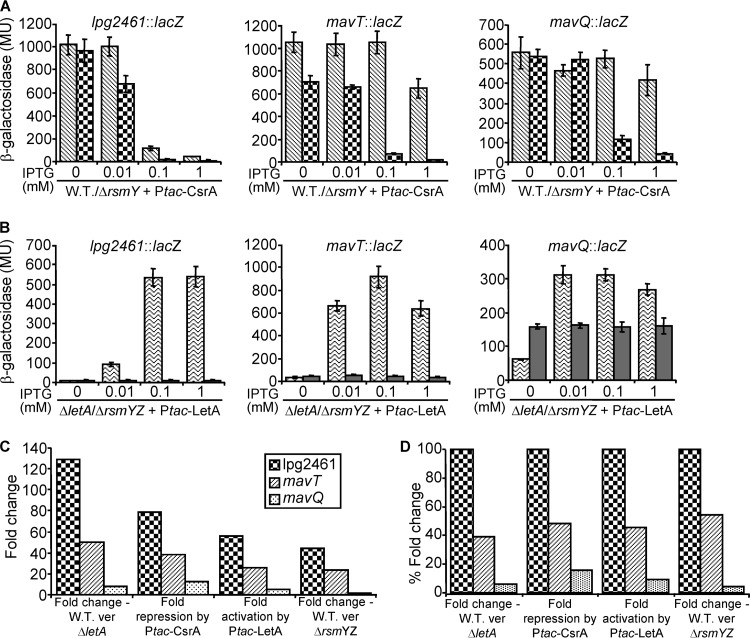

Analysis of the expression data of the genes regulated by the LetA-RsmYZ-CsrA regulatory cascade indicates that the degrees of reduction in their levels of expression in the letA deletion mutant and the rsmYZ double-deletion mutant differ significantly from the those seen with the wild-type strain (Fig. 1, 2, and 3). To further substantiate the regulation of these genes by the LetA-RsmYZ-CsrA regulatory cascade, we examined the effect of overexpression of different components of this cascade on the levels of expression of three effector-encoding genes (lpg2461, mavT, and mavQ), which were affected differently by the letA deletion mutant (129-fold, 50-fold, and 8-fold reduction, respectively). The levels of expression of these three genes were examined under conditions of increasing levels of CsrA (using an IPTG [isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside]-inducible Ptac-CsrA construct) in the wild-type strain and in the rsmY deletion mutant (Fig. 4A). Increasing levels of CsrA in the wild-type strain reduced the level of expression of lpg2461 in the two higher concentrations of IPTG (0.1 mM and 1 mM). The reduction occurring with mavT was observed only with the maximal IPTG concentration, and no reduction in the level of expression of mavQ was observed in the wild-type strain (Fig. 4A). When the same analysis was performed in the rsmY deletion mutant, the levels of expression of all three genes were reduced. A reduction in the level of expression of lpg2461 was obtained even when using a very low concentration of IPTG (0.01 mM). Furthermore, the levels of expression of these genes were also examined under conditions of increasing levels of LetA (using a Ptac-LetA construct) in the letA deletion mutant and in the rsmYZ double-deletion mutant (Fig. 4B). When increasing levels of LetA were examined in the letA deletion mutant (Fig. 4B), they were seen to result in complementation of the levels of expression of the three lacZ fusions. This complementation was completely dependent on the presence of RsmY and RsmZ, since, in their absence (the rsmYZ double-deletion mutant), no increases in the levels of expression of the three effector lacZ fusions were obtained with increasing levels of LetA (Fig. 4B). In this analysis, the maximal activation by LetA was obtained with lpg2461 and the lowest with MavQ.

FIG 4.

CsrA and LetA affect the levels of expression of different effector lacZ fusions similarly. (A) The levels of expression of the lpg2461, mavT, and mavQ lacZ fusions were examined in L. pneumophila wild-type strain JR32 (diagonal striped bars) and L. pneumophila rsmY deletion mutant MR-rsmY (boxed bars). The bacteria examined contained a plasmid with the csrA gene cloned under the control of the Ptac promoter (activated by IPTG). (B) The same effector lacZ fusions were examined in the L. pneumophila letA deletion mutant OG2001 (waved bars) and the L. pneumophila rsmYZ double-deletion mutant MR-rsmYZ (gray bars). The bacteria examined contained a plasmid with the letA gene cloned under the control of the Ptac promoter. In the experiments represented in both panel A and panel B, the strains were grown in media containing different concentrations of IPTG (indicated below the bars) and β-galactosidase activity was measured at the stationary phase as described in Materials and Methods. The data are the averages ± standard deviations (error bars) of the results of at least three different experiments. (C) Comparison of the effects of different mutants and overexpression conditions on the level of expression of the effector lacZ fusions examined as described for panels A and B. The mutants and overexpression conditions compared are indicated below the bars. (D) Data represent the results of experiments performed as described for panel C, but the degree of the effect on lpg2461 was normalized to 100% and the relative effects on mavT and mavQ genes were calculated in relation to it. ver, versus.

In all parameters tested in Fig. 1 and Fig. 4, the strongest effect was obtained with lpg2461, a moderate effect was observed with mavT, and the weakest effect was seen with mavQ (Fig. 4C). After normalization according to the effect on lpg2461, the degrees of the effects of each of the mutants or overexpression conditions on the genes were similar (Fig. 4D). These results strongly indicate that, even though the degrees of the effects of the letA deletion mutant on the levels of expression of the genes examined were different, all of them are regulated by the LetA-RsmYZ-CsrA regulatory cascade.

Mutagenesis of the putative CsrA regulatory elements results in elevated levels of expression at the exponential phase.

To further investigate the putative CsrA sites identified in the bioinformatic screen, we performed site-directed mutagenesis on 13 putative CsrA sites in 13 different effector-encoding genes (marked by asterisks in Fig. 3). The putative CsrA sites selected for site-directed mutagenesis were from genes that were affected differently by the letA deletion mutant, and they were constructed in putative CsrA sites located upstream or downstream from the ATG start codon of the genes (Fig. 3). In addition, we avoided constructing mutations in putative CsrA sites that also constitute the potential ribosomal binding sites, since generating mutations in such sites would most likely influence both the putative CsrA site and the putative ribosomal binding site, making the results ambiguous. The results of this analysis were very clear (Fig. 5): mutations in all the putative CsrA sites (9 AGGA, 4 ATGGA, and 3 AGGGA sites) resulted in levels of expression of the lacZ fusions that were higher than those seen with the wild-type lacZ fusions at the exponential phase. This result was expected, since these sites are subjected to repression by the CsrA translational repressor at the exponential phase (see the introduction). In addition, we mutagenized the ACGGA site found in cegC1, and the level of expression of a lacZ fusion containing this mutation was found to be similar to that of the wild-type lacZ fusion (data not shown). This result supports our assumption that the ACGGA sites are not functional CsrA sites in L. pneumophila (see above). Collectively, these results strongly indicate that the mutated CsrA sites are subjected to repression at the exponential phase and that their mutagenesis resulted in a relief of this repression, thus further supporting the idea of the regulation of these genes by the LetA-RsmYZ-CsrA cascade.

FIG 5.

Mutations constructed in the putative CsrA regulatory elements resulted in elevated levels of expression at the exponential phase. The expression of effector (indicated below the bars) wild-type lacZ fusions (white bars) and lacZ fusions of the same genes containing a mutation in a putative CsrA binding site (waved bars) were examined at the exponential phase in the L. pneumophila wild-type strain. The mutations constructed are marked by asterisks in Fig. 3. β-Galactosidase activity was measured as described in Materials and Methods. The data are the averages ± standard deviations (error bars) of the results of at least three different experiments. The genes were divided according to their levels of expression.

The LetA-RsmYZ-CsrA coregulated effectors inhibit yeast cell growth.

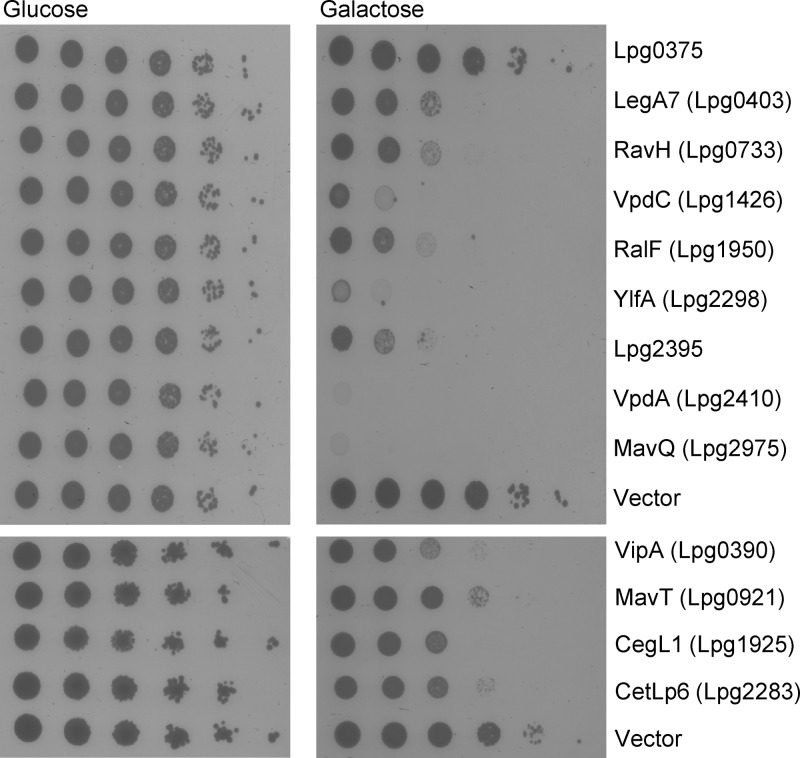

Five of the 26 effector proteins identified in our screen (VipA, VpdC, RalF, LegC7/YlfA, and VpdA) were shown before to be lethal when overexpressed in yeast cells (43, 59, 60). The lethal effect on yeast growth suggests that a conserved and essential eukaryotic process which is modulated by the effector in the host cell was also modulated in the yeast cell, resulting in an inhibition of cell growth (43, 59, 61, 62). Examination of all the 26 LetA-RsmYZ-CsrA coregulated effectors in yeast revealed that 12 of them (VipA, LegA7, RavH, MavT, VpdC, CegL1, RalF, CetLp6, LegC7/YlfA, Lpg2395, VpdA, and MavQ) cause lethal effects on yeast growth (Fig. 6 and Table 1). (Lpg2461 was not examined since it was impossible to introduce it into yeast; a similar result was observed before with other effectors, some of which were found to inhibit translation [59].) This result indicates that almost half of the LetA-RsmYZ-CsrA coregulated effectors affect conserved eukaryotic processes.

FIG 6.

Effectors regulated by the LetA-RsmYZ-CsrA cascade cause different degrees of lethal effect on yeast growth. The effectors regulated by the LetA-RsmYZ-CsrA cascade were cloned under the control of the GAL1 promoter and grown on plates containing glucose or galactose (inducing conditions) in the wild-type S. cerevisiae BY4741 strain. Ten-fold serial dilutions were performed, and the lethal effect was compared to the one of the vector pGREG523 control (vector). Lpg0375 is presented as a representative of an effector that caused no lethal effect on yeast growth. The effectors presented in the upper panel were examined at 30°C, and the effectors presented in the lower panel were examined at 37°C.

TABLE 1.

Effect on yeast growth and trafficking caused by LetA-RsmYZ-CsrA-regulated effectors

| lpg no. | Name | Lethal effect ina: |

Involvement in traffickingb | Source or reference(s)c | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild type | sec22Δ mutant | ||||

| lpg0012 | CegC1 | − | +++ | ||

| lpg0375 | − | − | SGD in arl1Δ mutant | This study | |

| lpg0390 | VipA | + (37°C) | ++++ (37°C) | Binds actin, associates with early endosomes | 42, 59 |

| lpg0403 | LegA7 | ++ | ++++ | ||

| lpg0733 | RavH | ++ | − | SGD in arfΔ and arlΔ mutants | This study |

| lpg0921 | MavT | + (37°C) | ++ (37°C) | ||

| lpg0963 | − | ++ | |||

| lpg1083 | − | ++ | |||

| lpg1110 | Lem5 | − | ++ | ||

| lpg1166 | RavR | − | ++ | ||

| lpg1273 | − | ++ | |||

| lpg1426 | VpdC | +++ | ++++ | Phospholipase A | 59 |

| lpg1598 | Lem11 | − | ++ | ||

| lpg1660 | LegL3 | − | ++ | ||

| lpg1884 | LegC2/YlfB | − | ++ | Colocalized with anti-KDEL antibodies | 43, 59 |

| lpg1925 | CegL1 | + (37°C) | +++ (37°C) | ||

| lpg1950 | RalF | ++ | +++ | Arf1-GEF | 43, 59, 63 |

| lpg2283 | CetLp6 | + (37°C) | +++ (37°C) | SGD in arfΔ and arlΔ mutants | This study |

| lpg2298 | LegC7/YlfA | ++++ | ++++ | Colocalized with anti-KDEL antibodies | 12, 43, 59 |

| lpg2324 | CegL2 | − | +++ | ||

| lpg2395 | ++ | +++ | |||

| lpg2410 | VpdA | ++++ | ++++ | Phospholipase A | 59 |

| lpg2461 | X | X | |||

| lpg2678 | − | − | |||

| lpg2975 | MavQ | ++++ | ++++ | ||

| lpg2999 | LegP | − | − | ||

The scale of the lethal effect on yeast growth was as follows: −, no effect; +, weak effect; ++, medium effect; +++, strong effect; ++++, very strong effect; X, no yeast transformants were obtained.

SGD, synthetic growth defect.

The references listed indicate the sources for the information about the effect on trafficking.

Most of the LetA-RsmYZ-CsrA coregulated effectors manipulate vesicular trafficking in yeast.

To further examine these effectors, we utilized a well-established approach which was used before to uncover genetic interactions, such as synthetic growth defects, between gene pairs in yeast (64). This approach was also used before with bacterial effectors, some of which resulted in a synthetic growth defect when expressed in specific yeast deletion mutants related to their function (i.e., the mutants were hypersensitive to the expression of the effector) (51, 65). The assumption is that this phenotype results from the activity of the effector, which resembles the phenotype of a mutation in the effector target protein; thus, the phenotype results from the combined effect of the absence of the gene deleted and the misfunctioning of the effector target protein. Three of the LetA-RsmYZ-CsrA coregulated effectors (VipA, RalF, and LegC7/YlfA) which were shown to cause lethal effect on yeast growth and one that did not (LegC2/YlfB) were shown before to be involved in vesicular trafficking (42, 59, 66). Therefore, we decided to test whether additional LetA-RsmYZ-CsrA coregulated effectors are involved in vesicular trafficking.

Most of the genes encoding components of the secretory pathway are essential for yeast growth. Exceptions to this rule are genes such as sec22 and arf1, which can be deleted (67, 68). Therefore, we overexpressed the LetA-RsmYZ-CsrA coregulated effectors in yeast deleted for the sec22 gene, which encodes an R-SNARE protein (involved in ER-Golgi trafficking), and examined their effect on the growth of this mutant. As expected from their known function, VipA, RalF, and LegC2/YlfB showed an enhanced lethal effect on yeast growth in the sec22Δ mutant in comparison to their effect on the wild-type yeast strain (Fig. 7 and data not shown). Furthermore, 15 additional effectors showed a clear synthetic growth defect in the sec22Δ mutant in comparison to the wild-type yeast (Fig. 7 and Table 1). Only 6 of the 25 effectors examined did not show synthetic growth defect in the sec22Δ mutant (Fig. 7 and Table 1). These six effectors include three effectors that caused a very strong lethal effect on wild-type yeast growth (no additive effect was observed for two of the three [Fig. 6]) and three effectors that did not cause a lethal effect on wild-type yeast growth. The lack of an additive effect with these effectors further supports the idea of the specificity of the synthetic growth defect observed with the majority of the effectors. Strikingly, the lethal effect mediated by RavH in the wild-type yeast was completely suppressed in the sec22Δ mutant (Fig. 7), indicating that deletion of the sec22 gene can sometimes prevent the lethal effect caused by an effector (see below). To further strengthen the specificity of the results obtained, we examined two effectors that are not involved in trafficking (LegS2 and LpdA [51, 69]), and that are not regulated by the LetA-RsmYZ-CsrA cascade, for their lethal effect in the sec22Δ mutant in comparison to the wild-type yeast strain; no additive effect was observed (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). Together, these results strongly indicate that 19 of the 26 LetA-RsmYZ-CsrA coregulated effectors are probably involved in the modulation of endoplasmic reticulum (ER)-Golgi vesicular trafficking in yeast.

FIG 7.

Several L. pneumophila effectors cause a synthetic growth defect in the yeast sec22 deletion mutant. Data represent a comparison of the degrees of lethal effect caused by effectors expressed in the wild-type yeast and the sec22Δ mutant. Yeast containing the effectors indicated on the right were plated in 10-fold serial dilutions under inducing conditions (galactose). The effectors were overexpressed in the wild-type S. cerevisiae BY4741 strain (upper dilutions in each pair) and the sec22Δ mutant (lower dilutions in each pair). The vector on which the effectors were cloned (pGREG523) was used as a control (vector). Lpg0375, YlfA, and LegP are presented as representatives of effectors that caused no additive effect in the sec22Δ mutant. The glucose control plates of this experiment are shown in Fig. S2 in the supplemental material.

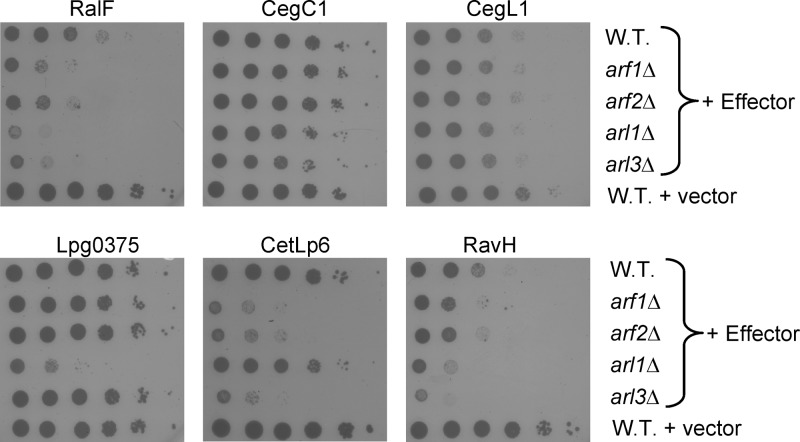

Three novel LetA-RsmYZ-CsrA coregulated effectors manipulate different components of ER-Golgi vesicular trafficking.

It was shown before that effectors manipulate different components of the secretory pathway (34, 35, 70), and the effectors that showed a synthetic growth defect in the sec22Δ mutant described above might function on different components of this pathway. To further characterize the involvement of these effectors in the ER-Golgi trafficking, they were expressed in arf1Δ, arl1Δ, and arl3Δ mutants, which encode small GTPases involved in the ER-Golgi trafficking.

The results obtained from this analysis indicated that the expression of four effectors (Lpg0375, RalF, CetLp6, and RavH) caused a synthetic growth defect in the arf1Δ, arl1Δ, and arl3Δ mutants (Fig. 8 and Table 1). This result probably indicates that the arf1Δ, arl1Δ, and arl3Δ mutants uncover effects on the secretory pathway that are more specific than those of the sec22Δ mutant. To further strengthen the specificity of the results obtained, we examined two effectors (LegS2 and LpdA) that are not regulated by the LetA-RsmYZ-CsrA cascade for their lethal effect in the arf1Δ, arf2Δ, arl1Δ, and arl3Δ mutants in comparison to the wild-type yeast strain, and no additive effect was observed (see Fig. S3A in the supplemental material). In addition, the mutants strains themselves grew similarly to the wild-type yeast strain under the conditions used (see Fig. S3B).

FIG 8.

Several L. pneumophila effectors cause a synthetic growth defect in the yeast arf and arl deletion mutants. Data represent a comparison of the degrees of lethal effect caused by RalF, CegC1, CegL1, lpg0375, CetLp6, and RavH in different yeast arf and arl deletion mutants plated in 10-fold serial dilutions under inducing conditions (galactose). The effectors (indicated above each panel) were overexpressed in the wild-type S. cerevisiae BY4741 strain (W.T.), the arf1 deletion mutant (arf1Δ), the arf2 deletion mutant (arf2Δ), the arl1 deletion mutant (arl1Δ), and the arl3 deletion mutant (arl3Δ). The vector on which the effectors were cloned (pGREG523) was used as a control (vector). CegC1 and CegL1 are presented as representatives of effectors that caused no additive effect in the arf and arl deletion mutants. The glucose control plates of this experiment are shown in Fig. S4 in the supplemental material.

One of the effectors that caused a synthetic growth defect in the arf and arl mutants was RalF (Fig. 8). RalF was shown before to function as an Arf1-GEF (ADP ribosylation factor-guanine exchange factor) (43, 59, 63), and therefore it was expected that it would cause a synthetic growth defect in these mutants (see Discussion). Three additional effectors examined (Lpg0375, CetLp6, and RavH) showed interesting results in the arf and arl mutants. (i) The Lpg0375 effector showed no additive effect in the sec22Δ mutant as well as in the arf1Δ, arf2Δ, and arl3Δ mutants but had a very strong lethal effect in the arl1Δ deletion mutant (Fig. 8). This result might indicate that this effector modulates a specific factor of the secretory pathway and that its malfunctioning caused the synthetic growth defect only in the arl1Δ mutant. (ii) The CetLp6 effector caused a moderate lethal effect on wild-type yeast growth, and it showed a strong additive lethal effect in the sec22Δ mutant as well as in the arf1Δ, arf2Δ, and arl3Δ mutants, but no additive effect was observed in the arl1Δ deletion mutant (Fig. 8). The contrasting results obtained with Lpg0375 and CetLp6 in all the mutants examined might indicate that the arl1Δ mutant exposes specific functions mediated by the effectors. (iii) The most fascinating result was obtained with the effector RavH. RavH caused moderate lethal effect on wild-type yeast growth, and its lethal effect was completely suppressed in the sec22Δ mutant (Fig. 7). However, expression of this effector in the arf1Δ, arf2Δ, arl1Δ, and arl3Δ mutants showed a synthetic growth defect, especially with the arl3Δ mutant (Fig. 8), indicating that this effector modulates a host factor different from those modulated by the other effectors examined (see Discussion). Collectively, these results indicate that three novel LetA-RsmYZ-CsrA coregulated effectors probably manipulate different components of the ER-Golgi trafficking pathway.

DISCUSSION

The study of the regulation of L. pneumophila effectors until now revealed three main regulatory systems that control the level of expression of effectors (21). These systems include the two-component systems PmrAB and CpxRA and the LetA-RsmYZ-CsrA regulatory cascade (references 15, 16, and 19 and this study). These three regulatory systems were shown to be part of a regulatory network that regulates the expression of effector-encoding genes (21). As part of this network, a regulatory switch was described in which the PmrA response regulator directly activates the expression of a group of effector-encoding genes, and indirectly represses the expression of a second group of effectors, by directly activating the expression of the CsrA posttranscriptional repressor (19). In this study, we expanded the group of effector-encoding genes known to be regulated by the LetA-RsmYZ-CsrA regulatory cascade and identified three regulators that might also participate in the regulatory network that controls the expression of effector-encoding genes. We found that the CsrA posttranscriptional repressor itself controls the expression of three other regulators (FleR, RpoE, and LqsR). The possible involvement of FleR in the regulation of pathogenesis-related genes is the most appealing one, since its regulation of a flagellum-related gene in L. pneumophila was found to be different from its regulation in other bacteria (57), which might indicate that this regulator participates in the regulation of genes other than flagellum-related genes in L. pneumophila.

The level of expression of the LetA-RsmYZ-CsrA coregulated effectors was found to be higher at the stationary phase (reference 19 and this study). This result suggests that the cytoplasm of L. pneumophila that ended an infection cycle (the equivalent of the stationary phase) should be loaded with the 26 LetA-RsmYZ-CsrA coregulated effectors identified in this study. Thus, when a new infection cycle begins, these effectors are probably the first to translocate into the host cell (depending also on their secretion signal and possible interaction with chaperons) and might participate in the establishment of the LCV which involves massive modulation of the ER-Golgi vesicular trafficking. To examine whether the LetA-RsmYZ-CsrA coregulated effectors are involved in vesicular trafficking, we examined them in several yeast mutants with mutations in genes which encode proteins that participate in this pathway. The Sec22 R-SNARE protein is a critical component of the yeast secretory pathway, and it functions in ER-Golgi anterograde and retrograde trafficking (71). However, a deletion of the yeast sec22 gene was found to be viable since another R-SNARE protein (Ykt6) compensates for its absence (67). Moreover, it was previously shown that the human Sec22b protein (the homolog of the yeast Sec22 protein) is localized to the LCV during L. pneumophila infection (38) and that this protein is required for L. pneumophila multiplication in cells (36, 37). Additionally, in yeast there are six (Sar1, Arf1, Arf2, Arl1, Arl3, and Ypt1) small GTPases that directly regulate different processes of the secretory pathway, and effectors that modulate Arf1 and Ypt1 were already described (39, 40, 43, 59, 63). Since sar1 and ypt1 are essential genes in yeast, we used yeast arf1Δ, arf2Δ, arl1Δ, and arl3Δ mutants in our analyses. Arf1 and Arf2 are highly homologous; they regulate ER-Golgi trafficking and are synthetic lethal in yeast (68), and the Arl1 and Arl3 small GTPases are involved in Golgi trafficking (72).

These analyses uncovered three interesting effectors. The first effector, CetLp6, like RalF, showed a synthetic growth defect in the sec22Δ mutant as well as in the arf1Δ, arf2Δ, and arl3Δ mutants (RalF showed a synthetic growth defect also in the arl1Δ mutant; Fig. 8). It is known that RalF functions as an Arf1-GEF; therefore, it was expected that a synthetic growth defect would be obtained with this effector in the arf1Δ and arf2Δ mutants since in both mutants the level of the RalF target protein is reduced and consequently RalF is expected to activate a larger fraction of its remaining target protein, thus causing a synthetic growth defect. The similar result that was obtained with CetLp6 might indicate that this effector functions on one of the Arf/Arl proteins as well. The second effector, Lpg0375, showed a result that was opposite the CetLp6 result, and a synthetic growth defect was observed only in the arl1Δ mutant. Since the function of Arl1 is restricted to the Golgi compartment, this result might indicate that this effector modulates a protein of the secretory pathway that functions in this compartment. The third effector, RavH, showed intriguing results that might indicate its function. The moderate lethal effect of RavH in wild-type yeast was completely suppressed in the sec22Δ mutant, but its expression caused a synthetic growth defect with the arf1Δ, arf2Δ, and arl1Δ mutants and particularly in the arl3Δ mutant. In general, suppression of the lethal effect of an effector can be obtained in one of three ways: (i) deletion of the yeast target protein modulated by the effector (as was shown with the effector LecE and its target protein Pah1 [51]); (ii) overexpression of a yeast protein that counteracts the effector function (as was shown with the effector LecE and the Dgk1 protein [51]); or (iii) overexpression of the effector target protein (as was shown with the effector AnkX and its target protein Ypt1 [73]). The results obtained with RavH in the sec22Δ mutant might indicate that Sec22 itself or a protein located upstream in the pathway which leads to Sec22 activation (such as Sar1 or a Sar1-GEF) might serve as the RavH target protein.

In conclusion, our study revealed numerous effectors regulated by the LetA-RsmYZ-CsrA regulatory cascade, most of which were found to be implicated in vesicular trafficking. Further studies that will result in the identification of the host proteins that interact with these coregulated effectors are required in order to determine their specific function.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Martin Kupiec and Yaniv Harari for their assistance with the yeast system. We also thank Martin Kupiec and David Burstein for carefully reading the manuscript.

This research was supported by Israeli Science Foundation (ISF) grant 479/11 (to G.S.).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 22 November 2013

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/JB.01175-13.

REFERENCES

- 1.Fields BS, Benson RF, Besser RE. 2002. Legionella and Legionnaires' disease: 25 years of investigation. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 15:506–526. 10.1128/CMR.15.3.506-526.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Steinert M, Hentschel U, Hacker J. 2002. Legionella pneumophila: an aquatic microbe goes astray. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 26:149–162. 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2002.tb00607.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cianciotto NP. 2001. Pathogenicity of Legionella pneumophila. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 291:331–343. 10.1078/1438-4221-00139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gimenez G, Bertelli C, Moliner C, Robert C, Raoult D, Fournier PE, Greub G. 2011. Insight into cross-talk between intra-amoebal pathogens. BMC Genomics 12:542. 10.1186/1471-2164-12-542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Franco IS, Shuman HA, Charpentier X. 2009. The perplexing functions and surprising origins of Legionella pneumophila type IV secretion effectors. Cell. Microbiol. 11:1435–1443. 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2009.01351.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fields BS. 1996. The molecular ecology of Legionellae. Trends Microbiol. 4:286–290. 10.1016/0966-842X(96)10041-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ensminger AW, Isberg RR. 2009. Legionella pneumophila Dot/Icm translocated substrates: a sum of parts. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 12:67–73. 10.1016/j.mib.2008.12.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shin S, Roy CR. 2008. Host cell processes that influence the intracellular survival of Legionella pneumophila. Cell. Microbiol. 10:1209–1220. 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2008.01145.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gomez-Valero L, Rusniok C, Cazalet C, Buchrieser C. 2011. Comparative and functional genomics of Legionella identified eukaryotic like proteins as key players in host-pathogen interactions. Front. Microbiol. 2:208. 10.3389/fmicb.2011.00208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lifshitz Z, Burstein D, Peeri M, Zusman T, Schwartz K, Shuman HA, Pupko T, Segal G. 2013. Computational modeling and experimental validation of the Legionella and Coxiella virulence-related Type-IVB secretion signal. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 110:E707–E715. 10.1073/pnas.1215278110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cazalet C, Rusniok C, Bruggemann H, Zidane N, Magnier A, Ma L, Tichit M, Jarraud S, Bouchier C, Vandenesch F, Kunst F, Etienne J, Glaser P, Buchrieser C. 2004. Evidence in the Legionella pneumophila genome for exploitation of host cell functions and high genome plasticity. Nat. Genet. 36:1165–1173. 10.1038/ng1447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Felipe KS, Glover RT, Charpentier X, Anderson OR, Reyes M, Pericone CD, Shuman HA. 2008. Legionella eukaryotic-like type IV substrates interfere with organelle trafficking. PLoS Pathog. 4:e1000117. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Felipe KS, Pampou S, Jovanovic OS, Pericone CD, Ye SF, Kalachikov S, Shuman HA. 2005. Evidence for acquisition of Legionella type IV secretion substrates via interdomain horizontal gene transfer. J. Bacteriol. 187:7716–7726. 10.1128/JB.187.22.7716-7726.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Al-Khodor S, Price CT, Habyarimana F, Kalia A, Abu Kwaik Y. 2008. A Dot/Icm-translocated ankyrin protein of Legionella pneumophila is required for intracellular proliferation within human macrophages and protozoa. Mol. Microbiol. 70:908–923. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06453.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zusman T, Aloni G, Halperin E, Kotzer H, Degtyar E, Feldman M, Segal G. 2007. The response regulator PmrA is a major regulator of the icm/dot type IV secretion system in Legionella pneumophila and Coxiella burnetii. Mol. Microbiol. 63:1508–1523. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05604.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Altman E, Segal G. 2008. The response regulator CpxR directly regulates the expression of several Legionella pneumophila icm/dot components as well as new translocated substrates. J. Bacteriol. 190:1985–1996. 10.1128/JB.01493-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gal-Mor O, Segal G. 2003. Identification of CpxR as a positive regulator of icm and dot virulence genes of Legionella pneumophila. J. Bacteriol. 185:4908–4919. 10.1128/JB.185.16.4908-4919.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hammer BK, Tateda ES, Swanson MS. 2002. A two-component regulator induces the transmission phenotype of stationary-phase Legionella pneumophila. Mol. Microbiol. 44:107–118. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.02884.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rasis M, Segal G. 2009. The LetA-RsmYZ-CsrA regulatory cascade, together with RpoS and PmrA, post-transcriptionally regulates stationary phase activation of Legionella pneumophila Icm/Dot effectors. Mol. Microbiol. 72:995–1010. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06705.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sahr T, Bruggemann H, Jules M, Lomma M, Albert-Weissenberger C, Cazalet C, Buchrieser C. 2009. Two small ncRNAs jointly govern virulence and transmission in Legionella pneumophila. Mol. Microbiol. 72:741–762. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06677.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Segal G. 2013. The Legionella pneumophila two-component regulatory systems that participate in the regulation of Icm/Dot effectors. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 376:35–52. 10.1007/82_2013_346.s [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tiaden A, Spirig T, Weber SS, Bruggemann H, Bosshard R, Buchrieser C, Hilbi H. 2007. The Legionella pneumophila response regulator LqsR promotes host cell interactions as an element of the virulence regulatory network controlled by RpoS and LetA. Cell. Microbiol. 9:2903–2920. 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2007.01005.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hovel-Miner G, Faucher SP, Charpentier X, Shuman HA. 2010. ArgR-regulated genes are derepressed in the Legionella-containing vacuole. J. Bacteriol. 192:4504–4516. 10.1128/JB.00465-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hovel-Miner G, Pampou S, Faucher SP, Clarke M, Morozova I, Morozov P, Russo JJ, Shuman HA, Kalachikov S. 2009. SigmaS controls multiple pathways associated with intracellular multiplication of Legionella pneumophila. J. Bacteriol. 191:2461–2473. 10.1128/JB.01578-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lucchetti-Miganeh C, Burrowes E, Baysse C, Ermel G. 2008. The post-transcriptional regulator CsrA plays a central role in the adaptation of bacterial pathogens to different stages of infection in animal hosts. Microbiology 154:16–29. 10.1099/mic.0.2007/012286-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Romeo T, Vakulskas CA, Babitzke P. 2013. Post-transcriptional regulation on a global scale: form and function of Csr/Rsm systems. Environ. Microbiol. 15:313–324. 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2012.02794.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Timmermans J, Van Melderen L. 2010. Post-transcriptional global regulation by CsrA in bacteria. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 67:2897–2908. 10.1007/s00018-010-0381-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Edwards RL, Jules M, Sahr T, Buchrieser C, Swanson MS. 2010. The Legionella pneumophila LetA/LetS two-component system exhibits rheostat-like behavior. Infect. Immun. 78:2571–2583. 10.1128/IAI.01107-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Molofsky AB, Swanson MS. 2003. Legionella pneumophila CsrA is a pivotal repressor of transmission traits and activator of replication. Mol. Microbiol. 50:445–461. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03706.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sahr T, Rusniok C, Dervins-Ravault D, Sismeiro O, Coppee JY, Buchrieser C. 2012. Deep sequencing defines the transcriptional map of L. pneumophila and identifies growth phase-dependent regulated ncRNAs implicated in virulence. RNA Biol. 9:503–519. 10.4161/rna.20270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gal-Mor O, Segal G. 2003. The Legionella pneumophila GacA homolog (LetA) is involved in the regulation of icm virulence genes and is required for intracellular multiplication in Acanthamoeba castellanii. Microb. Pathog. 34:187–194. 10.1016/S0882-4010(03)00027-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lynch D, Fieser N, Gloggler K, Forsbach-Birk V, Marre R. 2003. The response regulator LetA regulates the stationary-phase stress response in Legionella pneumophila and is required for efficient infection of Acanthamoeba castellanii. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 219:241–248. 10.1016/S0378-1097(03)00050-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Forsbach-Birk V, McNealy T, Shi C, Lynch D, Marre R. 2004. Reduced expression of the global regulator protein CsrA in Legionella pneumophila affects virulence-associated regulators and growth in Acanthamoeba castellanii. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 294:15–25. 10.1016/j.ijmm.2003.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Neunuebel MR, Machner MP. 2012. The taming of a Rab GTPase by Legionella pneumophila. Small GTPases 3:28–33. 10.4161/sgtp.18704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Isberg RR, O'Connor TJ, Heidtman M. 2009. The Legionella pneumophila replication vacuole: making a cosy niche inside host cells. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 7:13–24. 10.1038/nrmicro1967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.O'Connor TJ, Boyd D, Dorer MS, Isberg RR. 2012. Aggravating genetic interactions allow a solution to redundancy in a bacterial pathogen. Science 338:1440–1444. 10.1126/science.1229556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dorer MS, Kirton D, Bader JS, Isberg RR. 2006. RNA interference analysis of Legionella in Drosophila cells: exploitation of early secretory apparatus dynamics. PLoS Pathog. 2:e34. 10.1371/journal.ppat.0020034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kagan JC, Stein MP, Pypaert M, Roy CR. 2004. Legionella subvert the functions of Rab1 and Sec22b to create a replicative organelle. J. Exp. Med. 199:1201–1211. 10.1084/jem.20031706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kagan JC, Roy CR. 2002. Legionella phagosomes intercept vesicular traffic from endoplasmic reticulum exit sites. Nat. Cell Biol. 4:945–954. 10.1038/ncb883 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Neunuebel MR, Chen Y, Gaspar AH, Backlund PS, Jr, Yergey A, Machner MP. 2011. De-AMPylation of the small GTPase Rab1 by the pathogen Legionella pneumophila. Science 333:453–456. 10.1126/science.1207193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Franco IS, Shohdy N, Shuman HA. 2012. The Legionella pneumophila effector VipA is an actin nucleator that alters host cell organelle trafficking. PLoS Pathog. 8:e1002546. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002546 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shohdy N, Efe JA, Emr SD, Shuman HA. 2005. Pathogen effector protein screening in yeast identifies Legionella factors that interfere with membrane trafficking. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102:4866–4871. 10.1073/pnas.0501315102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Campodonico EM, Chesnel L, Roy CR. 2005. A yeast genetic system for the identification and characterization of substrate proteins transferred into host cells by the Legionella pneumophila Dot/Icm system. Mol. Microbiol. 56:918–933. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04595.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sadosky AB, Wiater LA, Shuman HA. 1993. Identification of Legionella pneumophila genes required for growth within and killing of human macrophages. Infect. Immun. 61:5361–5373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zusman T, Yerushalmi G, Segal G. 2003. Functional similarities between the icm/dot pathogenesis systems of Coxiella burnetii and Legionella pneumophila. Infect. Immun. 71:3714–3723. 10.1128/IAI.71.7.3714-3723.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Brachmann CB, Davies A, Cost GJ, Caputo E, Li J, Hieter P, Boeke JD. 1998. Designer deletion strains derived from Saccharomyces cerevisiae S288C: a useful set of strains and plasmids for PCR-mediated gene disruption and other applications. Yeast 14:115–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Giaever G, Chu AM, Ni L, Connelly C, Riles L, Veronneau S, Dow S, Lucau-Danila A, Anderson K, Andre B, Arkin AP, Astromoff A, El-Bakkoury M, Bangham R, Benito R, Brachat S, Campanaro S, Curtiss M, Davis K, Deutschbauer A, Entian KD, Flaherty P, Foury F, Garfinkel DJ, Gerstein M, Gotte D, Guldener U, Hegemann JH, Hempel S, Herman Z, Jaramillo DF, Kelly DE, Kelly SL, Kotter P, LaBonte D, Lamb DC, Lan N, Liang H, Liao H, Liu L, Luo C, Lussier M, Mao R, Menard P, Ooi SL, Revuelta JL, Roberts CJ, Rose M, Ross-Macdonald P, Scherens B, et al. 2002. Functional profiling of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae genome. Nature 418:387–391. 10.1038/nature00935 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Miller JH. 1972. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, NY [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ho SN, Hunt HD, Horton RM, Pullen JK, Pease LR. 1989. Site-directed mutagenesis by overlap extension using the polymerase chain reaction. Gene 77:51–59. 10.1016/0378-1119(89)90358-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jansen G, Wu C, Schade B, Thomas DY, Whiteway M. 2005. Drag&Drop cloning in yeast. Gene 344:43–51. 10.1016/j.gene.2004.10.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Viner R, Chetrit D, Ehrlich M, Segal G. 2012. Identification of two Legionella pneumophila effectors that manipulate host phospholipids biosynthesis. PLoS Pathog. 8:e1002988. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mercante J, Edwards AN, Dubey AK, Babitzke P, Romeo T. 2009. Molecular geometry of CsrA (RsmA) binding to RNA and its implications for regulated expression. J. Mol. Biol. 392:511–528. 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.07.034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Babitzke P, Romeo T. 2007. CsrB sRNA family: sequestration of RNA-binding regulatory proteins. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 10:156–163. 10.1016/j.mib.2007.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Edwards AN, Patterson-Fortin LM, Vakulskas CA, Mercante JW, Potrykus K, Vinella D, Camacho MI, Fields JA, Thompson SA, Georgellis D, Cashel M, Babitzke P, Romeo T. 2011. Circuitry linking the Csr and stringent response global regulatory systems. Mol. Microbiol. 80:1561–1580. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07663.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Heuner K, Steinert M. 2003. The flagellum of Legionella pneumophila and its link to the expression of the virulent phenotype. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 293:133–143. 10.1078/1438-4221-00259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Molofsky AB, Shetron-Rama LM, Swanson MS. 2005. Components of the Legionella pneumophila flagellar regulon contribute to multiple virulence traits, including lysosome avoidance and macrophage death. Infect. Immun. 73:5720–5734. 10.1128/IAI.73.9.5720-5734.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Albert-Weissenberger C, Sahr T, Sismeiro O, Hacker J, Heuner K, Buchrieser C. 2010. Control of flagellar gene regulation in Legionella pneumophila and its relation to growth phase. J. Bacteriol. 192:446–455. 10.1128/JB.00610-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tiaden A, Spirig T, Carranza P, Bruggemann H, Riedel K, Eberl L, Buchrieser C, Hilbi H. 2008. Synergistic contribution of the Legionella pneumophila lqs genes to pathogen-host interactions. J. Bacteriol. 190:7532–7547. 10.1128/JB.01002-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Heidtman M, Chen EJ, Moy MY, Isberg RR. 2009. Large-scale identification of Legionella pneumophila Dot/Icm substrates that modulate host cell vesicle trafficking pathways. Cell. Microbiol. 11:230–248. 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2008.01249.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.VanRheenen SM, Luo ZQ, O'Connor T, Isberg RR. 2006. Members of a Legionella pneumophila family of proteins with ExoU (phospholipase A) active sites are translocated to target cells. Infect. Immun. 74:3597–3606. 10.1128/IAI.02060-05 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Curak J, Rohde J, Stagljar I. 2009. Yeast as a tool to study bacterial effectors. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 12:18–23. 10.1016/j.mib.2008.11.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Slagowski NL, Kramer RW, Morrison MF, LaBaer J, Lesser CF. 2008. A functional genomic yeast screen to identify pathogenic bacterial proteins. PLoS Pathog. 4:e9. 10.1371/journal.ppat.0040009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nagai H, Kagan JC, Zhu X, Kahn RA, Roy CR. 2002. A bacterial guanine nucleotide exchange factor activates ARF on Legionella phagosomes. Science 295:679–682. 10.1126/science.1067025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Schuldiner M, Collins SR, Thompson NJ, Denic V, Bhamidipati A, Punna T, Ihmels J, Andrews B, Boone C, Greenblatt JF, Weissman JS, Krogan NJ. 2005. Exploration of the function and organization of the yeast early secretory pathway through an epistatic miniarray profile. Cell 123:507–519. 10.1016/j.cell.2005.08.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kramer RW, Slagowski NL, Eze NA, Giddings KS, Morrison MF, Siggers KA, Starnbach MN, Lesser CF. 2007. Yeast functional genomic screens lead to identification of a role for a bacterial effector in innate immunity regulation. PLoS Pathog. 3:e21. 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Nagai H, Cambronne ED, Kagan JC, Amor JC, Kahn RA, Roy CR. 2005. A C-terminal translocation signal required for Dot/Icm-dependent delivery of the Legionella RalF protein to host cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102:826–831. 10.1073/pnas.0406239101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Liu Y, Barlowe C. 2002. Analysis of Sec22p in endoplasmic reticulum/Golgi transport reveals cellular redundancy in SNARE protein function. Mol. Biol. Cell 13:3314–3324. 10.1091/mbc.E02-04-0204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Stearns T, Kahn RA, Botstein D, Hoyt MA. 1990. ADP ribosylation factor is an essential protein in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and is encoded by two genes. Mol. Cell. Biol. 10:6690–6699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Degtyar E, Zusman T, Ehrlich M, Segal G. 2009. A Legionella effector acquired from protozoa is involved in sphingolipids metabolism and is targeted to the host cell mitochondria. Cell. Microbiol. 11:1219–1235. 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2009.01328.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hubber A, Roy CR. 2010. Modulation of host cell function by Legionella pneumophila type IV effectors. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 26:261–283. 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-100109-104034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Barlowe CK, Miller EA. 2013. Secretory protein biogenesis and traffic in the early secretory pathway. Genetics 193:383–410. 10.1534/genetics.112.142810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gillingham AK, Munro S. 2007. The small G proteins of the Arf family and their regulators. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 23:579–611. 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.23.090506.123209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Tan Y, Luo ZQ. 2011. Legionella pneumophila SidD is a deAMPylase that modifies Rab1. Nature 475:506–509. 10.1038/nature10307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.