Abstract

Midcell selection, septum formation, and cytokinesis in most bacteria are orchestrated by the eukaryotic tubulin homolog FtsZ. The alphaproteobacterium Magnetospirillum gryphiswaldense (MSR-1) septates asymmetrically, and cytokinesis is linked to splitting and segregation of an intracellular chain of membrane-enveloped magnetite crystals (magnetosomes). In addition to a generic, full-length ftsZ gene, MSR-1 contains a truncated ftsZ homolog (ftsZm) which is located adjacent to genes controlling biomineralization and magnetosome chain formation. We analyzed the role of FtsZm in cell division and biomineralization together with the full-length MSR-1 FtsZ protein. Our results indicate that loss of FtsZm has a strong effect on microoxic magnetite biomineralization which, however, could be rescued by the presence of nitrate in the medium. Fluorescence microscopy revealed that FtsZm-mCherry does not colocalize with the magnetosome-related proteins MamC and MamK but is confined to asymmetric spots at midcell and at the cell pole, coinciding with the FtsZ protein position. In Escherichia coli, both FtsZ homologs form distinct structures but colocalize when coexpressed, suggesting an FtsZ-dependent recruitment of FtsZm. In vitro analyses indicate that FtsZm is able to interact with the FtsZ protein. Together, our data suggest that FtsZm shares key features with its full-length homolog but is involved in redox control for magnetite crystallization.

INTRODUCTION

Magnetotactic bacteria (MTB) produce magnetosomes to navigate along Earth's magnetic field lines toward growth-favoring microoxic environments. Magnetosomes consist of nanometer-sized membrane-enveloped magnetite crystals and have recently emerged as a model system to study formation of prokaryotic organelles (1). In the alphaproteobacterium Magnetospirillum gryphiswaldense MSR-1 (in the following, referred to as MSR-1) and related magnetospirilla, the intracellular organelles are attached to a filamentous cytoskeletal structure formed by the actin-like MamK protein (2, 3, 4) which assembles magnetosomes into a cohesive chain (5). This magnetosome chain generates a magnetic moment which aligns the cell in external magnetic fields. In order to be cleaved evenly during cytokinesis and to be equipartitioned to daughter cells, the magnetosome chain is positioned at midcell. After cytokinesis, daughter chains are translocated to midcell again, suggesting that chain separation and relocalization are coordinated with the cell cycle.

A crucial factor for midcell determination and septum formation in most bacteria is the conserved tubulin homolog FtsZ. FtsZ monomers assemble in a GTP-dependent manner to form protofilaments that align into higher-ordered structures by lateral self-interaction assisted by accessory proteins. The FtsZ polymers are membrane tethered by C-terminal interaction with FtsA and build ring- or arc-like structures at future division sites (6). These FtsZ assemblies recruit further cell division proteins to finally build the divisome complex (7, 8). Several factors have been identified that regulate the timing and spatial organization of FtsZ polymerization and interaction with itself and other cell division proteins (reviewed in references 9 and 10).

FtsZ protein concentration, localization, and polymeric state are tightly controlled during the cell cycle. Whereas most bacteria that rely on FtsZ for division have merely one ftsZ gene, a few alphaproteobacteria such as members of the Rhizobiales (11) and Magnetospirillum species were found to possess multiple ftsZ homologs (12). In Sinorhizobium, for example, one isoform (ftsZ1) is essential and expressed in free-living, nonsymbiotic cells, whereas the second, truncated gene (ftsZ2) is not essential but is likely involved when cells differentiate into bacteroids (13, 14). Heterologous expression of the two FtsZ proteins from Sinorhizobium meliloti blocked cell division in Escherichia coli, and replacement of the FtsZ1 C terminus by green fluorescent protein (GFP) led to polymerization into axial protein filaments (11, 15, 16). A function for the truncated ftsZ has not been demonstrated.

The three as yet published genome sequences of Magnetospirillum species indicate that these bacteria may contain up to four genes coding for FtsZ homologs. For example, whereas the complete genome of Magnetospirillum magneticum AMB-1 contains one full-length ftsZ gene and one truncated homolog, the incomplete genome of Magnetospirillum magnetotacticum MS-1 contains one full-length ftsZ gene in addition to three truncated ftsZ homologs, with two of them likely representing pseudogenes (12). This suggests that Magnetospirillum species typically may contain two functional ftsZ genes, one of which encodes a full-length protein while the other always encodes a C-terminally truncated protein. Interestingly, in all magnetospirilla, the truncated genes are part of the conserved mamXY operon within the magnetosome island (MAI) located next to genes exclusively involved in magnetosome formation (17, 18), which led to speculation that the truncated ftsZ genes may function in magnetosome synthesis and chain assembly or may be involved in the apparently unusual mechanism of asymmetric cell division and cell bending during cytokinesis in Magnetospirillum species (19, 20).

Cell division in magnetospirilla involves asymmetry along two directions. In addition to uneven lengths of daughter cells, the division septum grows inward asymmetrically from the position distal to the magnetosome chain. As a consequence, dividing cells bend unidirectionally and thereby facilitate cleavage of the magnetosome chain by leverage against intrachain magnetic forces. However, this asymmetry is not caused by the magnetosome chain itself since it is observed also in nonmagnetic cells. Interestingly, an asymmetric ring structure at midcell was observed in dividing MSR-1 cells by cryo-electron tomography (20). It has been speculated that this asymmetric structure may represent a partially membrane-detached Z-ring possibly formed by FtsZm as a result of the missing C-terminal FtsA binding domain in FtsZm.

After asymmetric septation and cytokinesis, split chains are recruited from the new cell poles to the centers of the daughter cells and thus to future division sites in an MamK-dependent manner. Magnetosome chain division and segregation thereby resemble partitioning mechanisms of other organelles and macromolecular complexes in bacteria; i.e., magnetosome chains undergo a dynamic pole-to-midcell translocation during the cell cycle, which is accomplished by an active, MamK-dependent process (20, 21). It has been speculated that magnetosome chain positioning at midcell might also be controlled by early-assembling components of the divisome such as FtsZ, perhaps by direct interaction with the magnetosome filament or by interaction with its homolog FtsZm (20).

In MSR-1, a full-length, likely essential ftsZ gene could not be identified within the currently unassembled genome (GenBank accession number CU459003.1) (17). However, the truncated homolog ftsZm has been analyzed by Ding et al. (22). Ding et al. reported that the purified FtsZm protein hydrolyzed GTP and polymerized into filamentous bundles in vitro. Deletion of the gene caused formation of small, superparamagnetic magnetite crystals reminiscent of the phenotype of the mamXY operon deletion mutant (18). This suggests that ftsZm is involved in control of biomineralization but not in cell division and growth. However, previous studies did not consider the presence of a full-length FtsZ protein and its potential interplay with FtsZm. Thus, in vivo properties such as polymerization, localization, and colocalization with FtsZ and magnetosome-related proteins have remained unresolved, and a putative role of FtsZm in chain division and asymmetric septation has not been addressed thoroughly.

Here, we analyzed the FtsZm protein in vivo by fluorescent tagging both in E. coli and MSR-1 and together with its hitherto uncharacterized and full-length paralog, FtsZ. Our data suggest that FtsZ and FtsZm polymeric structures in E. coli are different from those in MSR-1, and our in vitro results support the notion that FtsZm not only colocalizes but also interacts with FtsZ. Whereas ftsZm is not essential for asymmetric cell division and magnetosome chain recruitment, we found that the reported biomineralization defect in the ftsZm mutant could be compensated by the addition of nitrate, suggesting that ftsZm may be involved in redox control for biomineralization. These findings may indicate a novel role of tubulin homologs in prokaryotic cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, vectors, culture conditions, and fluorescence microscopy.

Bacterial strains and vectors are listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material. E. coli strains were cultivated in lysogeny broth (LB) medium. Kanamycin was added to 25 μg/ml when necessary, and E. coli BW29427 cultures (K. Datsenko and B. L. Wanner, unpublished data) were supported with 1 mM DL-α, ε-diaminopimelic acid (DAP). Medium was solidified by addition of 1.5% (wt/vol) agar. M. gryphiswaldense cultures were grown microaerobically in modified flask standard medium (FSM) at 30°C (23) and 120 rpm agitation, and kanamycin was added to 5 μg/ml when appropriate. To cultivate M. gryphiswaldense in ammonium medium, nitrate was replaced by ammonium chloride in an equimolar ratio. For growth under low-iron conditions, M. gryphiswaldense strains were cultivated in low-iron medium (LIM) (24) in six-well plates until no magnetic response was detectable. The optical density (OD) and magnetic response (Cmag) of exponentially growing cultures were measured photometrically at 565 nm as reported previously (25).

To record growth and Cmag curves, microaerobically grown overnight cultures were harvested and transferred into 100 ml of preflushed (1% O2) FSM in a sterile 250-ml bottle to an OD at 565 nm (OD565) of 0.025. The cultures were grown for 24 h at 30°C, and samples were taken at the beginning and after 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 14, 16, 20, and 24 h.

For fluorescence microscopy, M. gryphiswaldense strains were grown in 15-ml polypropylene tubes with sealed screw caps and a culture volume of 11 ml to early log phase. Expression of fluorescently labeled proteins was induced by addition of isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) to 2 mM, and samples were taken after 5 h or as indicated in the figure legends. E. coli strain BW29427 (auxotroph for diaminopimelic acid [DAP]) (provided by B. Wanner) was grown in LB broth supplemented with dl-α,ε-diaminopimelic acid (Sigma-Aldrich, Switzerland) to 1 mM. Overnight cultures were diluted 200-fold, and gene expression of fluorescently labeled proteins was induced by addition of IPTG to 1 mM. To generate spherical E. coli cells, DAP was omitted from the subculture medium. Five-microliter samples were immobilized on 1% (wt/vol) agarose pads and covered with a coverslip. The samples were imaged with an Olympus BX81 microscope equipped with a 100× UPLSAPO100XO objective and an Orca-ER camera (Hamamatsu) and appropriate filter sets. Exposures were recorded and processed (brightness and contrast adjustments) using Olympus Xcellence software. Images were assembled with the GNU Image Manipulation Program (GIMP).

Construction of integrative vectors for gene deletion and markerless chromosomal fluorescent fusion.

The ftsZm gene was deleted by a cre-lox-based technique as previously described (18, 26, 27). Briefly, lox sites were introduced up- and downstream of the ftsZm gene by conjugation and homologous recombination. For homologous recombination, up- and downstream flanking regions of the ftsZm gene were cloned into suicide vector pAL01 or pAL02/2 (18) harboring a lox71 site and a kanamycin resistance cassette or a lox66 site and a gentamicin resistance cassette, respectively. The upstream flanking regions were amplified using primers OR017/OR018, and the downstream flanking regions were amplified using primers OR019/OR020 and cloned using EcoRI and NotI restriction sites and BamHI and HindIII restriction sites, respectively. Integration of both vectors was controlled by growth on medium containing kanamycin, gentamicin, or both antibiotics and confirmed by PCR. Excision of the lox-flanked gene was accomplished by transformation of plasmid pLJY87 (Y. Li, unpublished data) expressing Cre recombinase. Specific gene deletion was verified by PCR using oligonucleotide primers OR035/OR081, followed by sequencing of the PCR product. Presence or absence of the ftsZm gene in the deletion strain and wild type (wt) were additionally verified by PCR using the oligonucleotide primer pair oFM240a/oFM241b and genomic DNA as the template.

All constructs were verified by DNA sequencing using an ABI 3700 capillary sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Darmstadt, Germany), utilizing a BigDye Terminator, version 3.1, kit. Sequence data were analyzed with Vector NTI Advance, version 11. 5, software (Invitrogen).

ftsZm overexpression.

The plasmid pOR051 harboring the ftsZm gene under the control of the IPTG-inducible lac promoter was transferred into MSR-1 wt by conjugation. Kanamycin-resistant colonies were passaged into FSM and cultivated at 30°C under microoxic conditions in the presence of kanamycin. To induce ftsZm expression, overnight cultures of the transformed strains were diluted in FSM to an OD565 of 0.05 and induced with 2 mM IPTG (final concentration). Control cultures were treated equally but not induced with IPTG. Samples were taken immediately and at 16 h after IPTG induction and fixed by addition of paraformaldehyde to 1% (wt/vol). Cell length and ultrastructure were analyzed by light and electron microscopy.

Bioinformatics and sequence analysis.

The working draft genome sequence of M. gryphiswaldense (GenBank accession number CU459003.1) was analyzed for homologs of the conserved cell division protein, FtsZ, using the BLASTp (28) algorithm. The putative position of a full-length ftsZ gene was determined by comparing its assumed conserved genomic context to the genomes of the closely related species M. magneticum AMB-1 and M. magnetotacticum MS-1. In both species, the full-length ftsZ is flanked by ftsA and lpxC. Homologs of these two genes were identified at the ends of two MSR-1 genome contigs but no ftsZ homolog was found, suggesting that the missing MSR-1 ftsZ gene is not part of the draft genome sequence but is within a gap between two fragments. The primers oFM221/oFM222n (see Table S2 in the supplemental material) were designed to match the 3′ end of ftsA and the 5′ end of lpxC, respectively. A PCR resulted in one single product of about 2 kbp which was cloned into pJET1.2 vector (Fermentas) and sequenced. tBLASTX analysis was applied to identify conserved genes within the sequence, and the most likely start codon of ftsZ was identified by alignment to the FtsZ sequences of M. magneticum AMB-1 and M. magnetotacticum MS-1.

Sequence alignments and phylogenetic trees were calculated with MEGA, version 4, software using the maximum-likelihood algorithm. Sequences were aligned by ClustalW (default settings), and similarity trees were constructed using the neighbor-joining (NJ) method and the bootstrap (1,000 replicates) phylogeny tests as described previously (29, 30).

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The obtained FtsZ sequence was deposited in the GenBank under accession number JN157806.

RESULTS

The biomineralization defect of the ftsZm mutant can be rescued by nitrate.

Previous work suggests that the ftsZm mutant synthesizes only small, superparamagnetic magnetite crystals, whereas growth is unaffected (22). To analyze whether FtsZm is essential for asymmetric cell septation and involved in midcell recruitment of magnetosomes, as hypothesized by Katzmann et al. (20), we generated a markerless ftsZm deletion mutant and assessed its phenotype in cell division and biomineralization. Consistent with previous observations, the mutant exhibited wt-like growth. Unexpectedly however, we found a wt-like magnetic response (Cmag measurements) (25), suggesting that deletion of ftsZm did not seriously disturb magnetosome formation when the ftsZm mutant was grown in our standard FSM (Fig. 1D). Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) analysis indicated that the mutant formed magnetite crystals of normal shape and size (Fig. 1C) and aligned in a wt-like chain. The chain was further located at midcell and opposite to an asymmetrically inward-growing division septum (Fig. 1A), as in the wt (20). We verified this observation by repeated gene deletion and with slightly different approaches, but in all attempts, we had identical results. We therefore tested whether different culture conditions may influence the described ftsZm mutant phenotype and grew the mutant under different nonstandard and stress conditions, such as altered temperature and nutrient concentrations. However, the mutant did not display any significant effect on growth and magnetism, as indicated by optical density and magnetic orientation. Similarly, cell length distributions did not differ reproducibly from wt levels (data not shown). However, when cells were grown in medium where nitrate was replaced by ammonium (thereby matching the culture conditions of the study of Ding et al. [22] in terms of electron acceptors), we could partially reproduce the biomineralization phenotype; i.e., cells contained many small, poorly crystalline flake-like crystals (Fig. 1B; see also Fig. S8 in the supplemental material) although we found that a significant number of cells still displayed wt-like magnetosomes (see Fig. S8 and S10). In addition, these crystals were coaligned in chains; and when both types of crystals were present in one cell, flakes were always found at both ends, and mature crystals were found at the center of the chains, reminiscent of the recently identified mamX and mamZ mutant phenotypes (31).

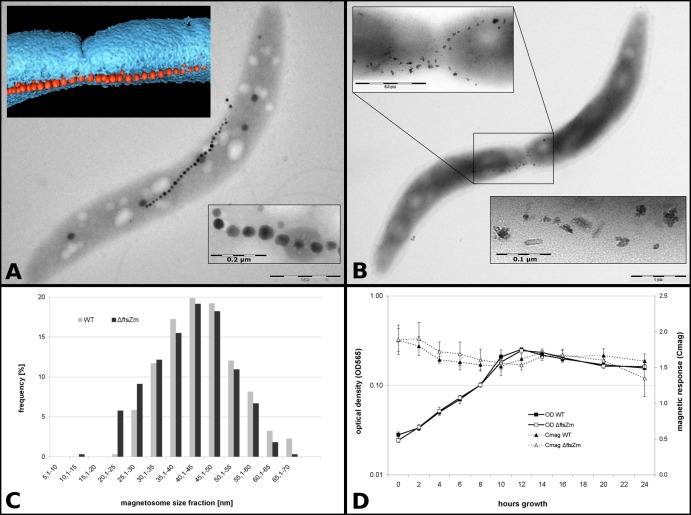

FIG 1.

The ftsZm mutant grown in FSM is indistinguishable from the wt. (A) TEM images depicting a representative ftsZm mutant cell grown in FSM (containing nitrate). In the upper inset, a segmented cryo-electron tomogram shows incipient membrane (blue) constriction at midcell distal to the magnetosome chain (red particles). In the lower inset a magnified section of a magnetosome chain reveals wt-like magnetite crystals. (B) TEM image of an ftsZm mutant cell grown in modified FSM where nitrate was replaced by ammonium in an equimolar ratio. The image of the cell is magnified in the upper inset. The lower inset shows the magnification of poorly crystallized, flake-like particles. (C) Size distribution of wt and ΔftsZm magnetosomes from cells grown in FSM showing no evident difference in crystal sizes. (D) Optical density and magnetic response measurements of wt and ftsZm mutant strains over a 24-h growth period in FSM showing no significant difference in growth and magnetism values.

MSR-1 has one full-length and one truncated ftsZ gene.

To analyze the role of FtsZm in more detail and to determine potential interaction partners, we searched for a generic full-length ftsZ gene. However, inspection of the incomplete MSR-1 genome revealed only one truncated FtsZ homolog (ftsZm) which is encoded in the mamXY operon of the MAI (17, 22). Comparison of the incompletely assembled MSR-1 genome to the genomes of the related Magnetospirillum species AMB-1 and MS-1 suggested that a full-length MSR-1 ftsZ gene is located in a gap between two sequence contigs. Sanger sequencing and tBLASTX analysis of a gap-bridging PCR product indeed revealed an ftsZ homolog, which shares 66% identity with the full-length FtsZ protein of M. magneticum AMB-1 and possesses a typical tubulin/FtsZ domain with the conserved signature motif GGGTGSG (corresponding to Prosite motifs PDOC00199/PDOC00873) (see Fig. S1A in the supplemental material). A conserved N-terminal section is followed by a 230-amino-acid (aa) nonconserved C-terminal linker and a C-terminal peptide which is perfectly conserved between all three Magnetospirillum species (see Fig. S1B). This architecture together with the genomic context suggests that this gene likely represents the generic ftsZ gene of MSR-1 with a conserved role in cell division (12, 32). Consistent with this assumption, we were not able to delete the gene by double homologous recombination (data not shown).

MSR-1 full-length FtsZ likely is a functional cell division protein.

Since there are two ftsZ homologs present in the MSR-1 genome, we still could not rule out that the full-length ftsZ might have a function other than in cell division. As genetic tools for controlled depletion of essential proteins in magnetospirilla are not yet established, we corroborated the assumed FtsZ function in cell division by overexpression and fluorescent tagging. Thus, we cloned the gene under the control of an inducible lac promoter and fused it C terminally to the red fluorescent protein mCherry. To test whether FtsZ colocalizes with MamK or MamC, we also coexpressed egfp-mamK or mamC-egfp. We selected the filament-forming, actin-like MamK protein because of its role in magnetosome recruitment to midcell and MamC because of its abundance and strict specificity for the magnetosome membrane (33). First, we explored localization patterns in E. coli.

Expression of full-length FtsZ-mCherry in E. coli blocked cell division, as indicated by cell filamentation starting approximately 20 min after induction. Fluorescence microscopy suggests that FtsZ-mCherry localized to the cytoplasmic membrane in early stages. In cells that were about to divide upon induction, FtsZ-mCherry also localized to the division plane which could be identified as constriction at midcell (see Movie S1 in the supplemental material). In later stages, the protein polymerized into bright, cell-spanning filaments (Fig. 2A and B). This localization pattern is reminiscent of the patterns of other heterologously expressed FtsZ proteins in E. coli.

FIG 2.

Localization patterns of full-length FtsZ, MamC, and MamK in E. coli (left side) and MSR-1 (right side). (A) Coexpression of FtsZ-mCherry and MamC-EGFP. FtsZ-mCherry (red) forms cell-spanning filaments, whereas MamC-EGFP (green) aggregates into speckles. (B) Expression of FtsZ-mCherry and EGFP-MamK. EGFP-MamK filaments (green) colocalize with FtsZ-mCherry (red). Cells in panels A and B were induced with IPTG (1 mM) for approximately 1 h. (C) FtsZ-mCherry expression time course. At 5 h after induction, FtsZ-mCherry localizes to the center of predivisional cells. Extended incubation blocks cell division and causes cell filamentation. Additional foci of FtsZ-mCherry appear located symmetrically between midcell and the cell poles. At approximately 12.5 h after induction, cells contain multiple evenly spaced FtsZ-mCherry spots. Insets show differential interference contrast images of the respective cell. (D) Localization patterns of FtsZ-mCherry (red) and the magnetosome-specific MamC-EGFP protein (green) in MSR-1 at 5, 12.5, and 20 h after induction of gene expression. From the beginning, the MamC-EGFP signal is confined to a filamentous structure indicating the position of the magnetosome chain. FtsZ-mCherry, however, localizes in a lateral spot at midcell at 5 h after induction. At 12.5 h after induction cells elongate, and FtsZ-mCherry forms several spots, whereas MamC-EGFP localizes in an elongated, central filament-like structure. After approximately 20 h, highly elongated cells display numerous lateral FtsZ-mCherry spots and one or multiple long magnetosome chains, as indicated by the MamC-EGFP fluorescence signal. (E) Coexpression of FtsZ-mCherry and EGFP-MamK for approximately 20 h causes cell filamentation. EGFP-MamK filaments bypass numerous FtsZ-mCherry foci. Depicted are two individual cells. Scale bar, 2 μm.

To explore a potential colocalization or interaction with the actin-like MamK, for which filamentous polymerization has been shown (2, 3, 5), the egfp-mamK genes were expressed from the same vector. Enhanced GFP (EGFP)-MamK polymerized into filaments that clearly colocalized with the FtsZ filaments (Fig. 2B), whereas coexpressed MamC-EGFP localized as seemingly membrane-attached speckles (Fig. 2A). These observations indicate that MSR-1 FtsZ has the potential to polymerize, to perturb cell division in E. coli, and to colocalize with MamK filaments.

We next analyzed the position of fluorescently labeled full-length FtsZ in MSR-1. By taking advantage of the weak lac promoter activity in MSR-1 (34), we minimized the negative effects of protein overexpression. Consistent with the assumed function of FtsZ, cell division was blocked, and cells grew as extended spirilla, suggesting that moderate overexpression or dominant dysfunctionality of FtsZ-mCherry impaired cell division (Fig. 2D and E). In contrast to E. coli, fluorescence microscopy revealed that FtsZ-mCherry formed numerous intracellular spots rather than filaments. In addition, the spots appeared to be asymmetric, i.e., to localize laterally. This asymmetry became more obvious when FtsZ-mCherry was coexpressed with the magnetosome-specific MamC-EGFP (33) and the magnetosome filament-forming EGFP-MamK protein. Both EGFP fluorescence signals were confined to a filamentous structure that bypassed lateral FtsZ-mCherry spots, suggesting that magnetosome chains and MamK filaments assemble but do not segregate independently of the cell's division and segregation machinery (Fig. 2D and E).

To test whether the spot-like FtsZ localization might have been an artifact caused by accumulation of overexpressed FtsZ-mCherry protein for several generation times, we also analyzed cells at distinct time points after induction. FtsZ-mCherry spots became visible after approximately 5 h at midcell. Later, when cells elongated, additional spots emerged apparently evenly spaced between existing spots and the cell poles, likely indicating blocked division sites (Fig. 2C). Notably, the asymmetric accumulation of the FtsZ-mCherry signal could be observed from the beginning, i.e., when cells were still nonelongated.

We also tested whether FtsZ has the potential to polymerize in vitro upon addition of GTP, as suggested by sequence analysis (see Fig. S1A in the supplemental material) and as characteristic for genuine FtsZ proteins. Therefore, we expressed the untagged FtsZ in E. coli, and the purified protein was tested for polymerization by light-scattering and electron microscopy. The results suggest that FtsZ formed homopolymers and extended bundles in the presence of GTP (see Fig. S2A, Bi, and Bii).

Taken together, these data suggest that the newly identified full-length FtsZ from MSR-1 is a functional and generic FtsZ protein and support the notion that FtsZm could have adopted an accessory function or may play an additional role apart from cell division.

FtsZm shares core properties with FtsZ.

We next focused on ftsZm expression and analyzed protein localization and the effect of overexpression in living cells. Unexpectedly, expression of FtsZm-mCherry blocked cell division in E. coli in a manner similar to that of FtsZ-mCherry, and the elongated cells contained bright, cell-spanning FtsZm filaments (Fig. 3Ai). In contrast to our results with FtsZ, we found that the fluorescence signal was never membrane associated but emerged from spots that localized predominantly at polar or subpolar positions. To analyze the origin of these filaments, we performed time-lapse fluorescence microscopy and started to image E. coli cells approximately 10 min after induction. Over time, straight fluorescent filaments nucleated at these spots and grew toward the cell center (see Movie S2 in the supplemental material). Concomitantly, cell division was blocked, leading to filamentation of the E. coli cells. Ultimately, the straight filaments extended into loose spirals lining the cell body (Fig. 3Ai; see also Fig. S3Aiii). We never observed tight helices or ring-like structures although the elongated cells contained well-separated nucleoids (see Fig. S3Aiv). When FtsZm-mCherry and EGFP-MamK were coexpressed, their polymeric structures conucleated at the same polar or subpolar foci (see Fig. S4A). The filaments, however, grew and persisted independently, and, in contrast to results with FtsZ-mCherry, they did not colocalize (Fig. 3Ai). To better visualize the coexistence of distinct filaments, the diaminopimelic acid (DAP) auxotrophic E. coli strain BW29427 was induced with IPTG and shifted to DAP-free medium, where it adopted a spherical cell shape. These cells still maintained discrete filaments, again suggesting that FtsZm and MamK do not interact in their filamentous state (Fig. 3Aii; see also Fig. S4B in the supplemental material).

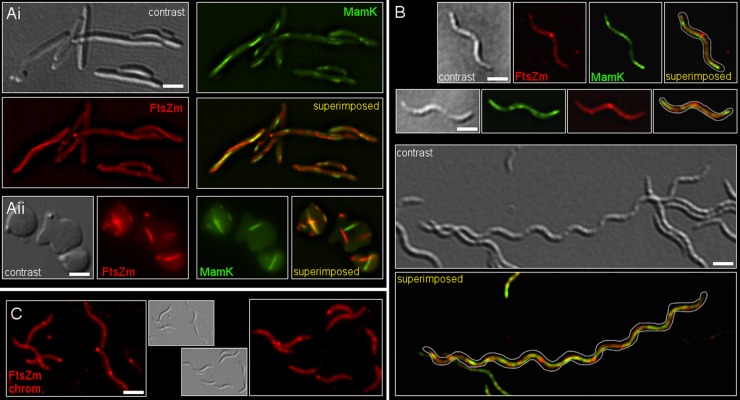

FIG 3.

Localization patterns of FtsZm, MamC, and MamK in E. coli (A) and MSR-1 (B and C). (Ai) Coexpression of FtsZm-mCherry and EGFP-MamK in E. coli DH5α. Cell division is inhibited, and both proteins polymerize into distinct filaments that do not colocalize. (Aii) Expression of FtsZm-mCherry and EGFP-MamK in E. coli BW29427. The protein filaments bend and line the inner cell surface. Cells in panels Ai and Aii were induced with IPTG (1 mM) for approximately 1 h prior to imaging. E. coli BW29427 was harvested before induction and transferred into DAP-free LB medium, where cells adopted a spherical shape due to impaired cell wall synthesis. (B) Upper panels show images of MSR-1 cells expressing FtsZm-mCherry and EGFP-MamK for approximately 5 h. FtsZm-mCherry forms a lateral spot at midcell, reminiscent of FtsZ-mCherry (Fig. 2D and E), whereas EGFP-MamK forms a filamentous structure indicative of the magnetosome filament. The lower panel shows an elongated cell approximately 20 h after induction of gene expression. (C) Fluorescence and differential interference contrast images of cells carrying a markerless chromosomal ftsZm-mCherry fusion. The protein accumulates in foci primarily at midcell and at the cell poles. Scale bar, 2 μm.

Expression of FtsZm-mCherry in MSR-1 caused cells to elongate less than in cells expressing FtsZ-mCherry, suggesting a weaker effect on cell division. Similar to FtsZ-mCherry, FtsZm-mCherry did not form filaments in MSR-1. The fluorescence signal appeared as spots at midcell reminiscent of the FtsZ-mCherry position (Fig. 3B). Notably, this pattern could also be observed in the MSR-1B mutant (35), where large parts of the MAI are absent (see Fig. S5 in the supplemental material), suggesting that the FtsZm localization pattern is independent of other MAI-encoded factors. To test if the FtsZm-mCherry expression affects MamK filament formation, we assessed the localization of EGFP-MamK in parallel. As in the case of FtsZ-mCherry, we found the EGFP-MamK filaments closely bypassing lateral FtsZm-mCherry spots (Fig. 3).

To exclude that the perturbed cell division upon FtsZm-mCherry expression in MSR-1 was due to dysfunctionality of the fusion protein, we next expressed the untagged ftsZm from the same inducible promoter and imaged the cells by light microscopy and TEM. We observed that cells started to elongate 6 h after induction with IPTG, and filamentation became pronounced 16 h after induction (corresponding to approximately three to four generation times), again suggesting that FtsZm may indeed interfere with cell division. The magnetic response of induced and uninduced cultures did not differ significantly, consistent with the TEM micrographs, which confirmed that elongated cells contained longer magnetosome chains with a high crystal number (see Fig. S6 in the supplemental material), reminiscent of cephalexin-treated cells (20).

To avoid the severe effects on cell division caused by protein overexpression and to analyze protein localization under native expression levels we next generated a markerless chromosomal ftsZm-mCherry fusion. Immunoblot analysis indicated that the fusion protein was expressed and stable under standard culture conditions (see Fig. S7 in the supplemental material). In these strains, filamentous cells were not visible, suggesting that the labeled version as the sole ftsZm gene did not interfere with cell division. The observed fluorescence signal resembled that of the in trans-expressed protein; i.e., spots at midcell were visible in a proportion of cells. In addition, many cells displayed a mono- or bipolar protein localization pattern, and some cells showed spots at midcell and at one cell pole. We rarely observed intermediate states or more than three spots in a single cell (Fig. 3C). Assuming a confined midcell localization of FtsZm before cytokinesis, we hypothesize that the protein becomes relocated from the new cell pole to midcell during the cell cycle and follows the dynamic localization of full-length FtsZ proteins in other alphaproteobacteria (36, 37).

As for FtsZ, we next tested whether FtsZm has the potential to polymerize in vitro under the same conditions as its full-length homolog. As suggested by light-scattering microscopy and TEM analysis and in accordance with the findings of Ding et al. (22), the purified protein formed homopolymers and bundles (see Fig. S2A, Biii, and Biv in the supplemental material).

Taken together, these observations suggest that FtsZm has the potential to polymerize in vitro and under the same conditions as FtsZ and that overexpression interferes with cell division in E. coli and MSR-1, whereas magnetosome and filament formation were not perturbed in the presence of nitrate. In E. coli, FtsZm did not colocalize with MamK filaments.

FtsZ and FtsZm colocalize in vivo and interact in vitro.

The results of our localization experiments in E. coli and MSR-1 suggested that positioning of FtsZm may depend on FtsZ. Therefore, we coexpressed FtsZ-mCherry and FtsZm-EGFP and analyzed their subcellular localizations. As before, we first examined the proteins in E. coli and observed again the membrane-associated localization of FtsZ-mCherry. FtsZm-EGFP, however, now colocalized with FtsZ-mCherry to the cytoplasmic membrane instead of forming spots and straight filaments (Fig. 4A). In MSR-1, both proteins colocalized as well (Fig. 4B) but in a spot-like pattern, suggesting that there might be an FtsZ-dependent recruitment of FtsZm.

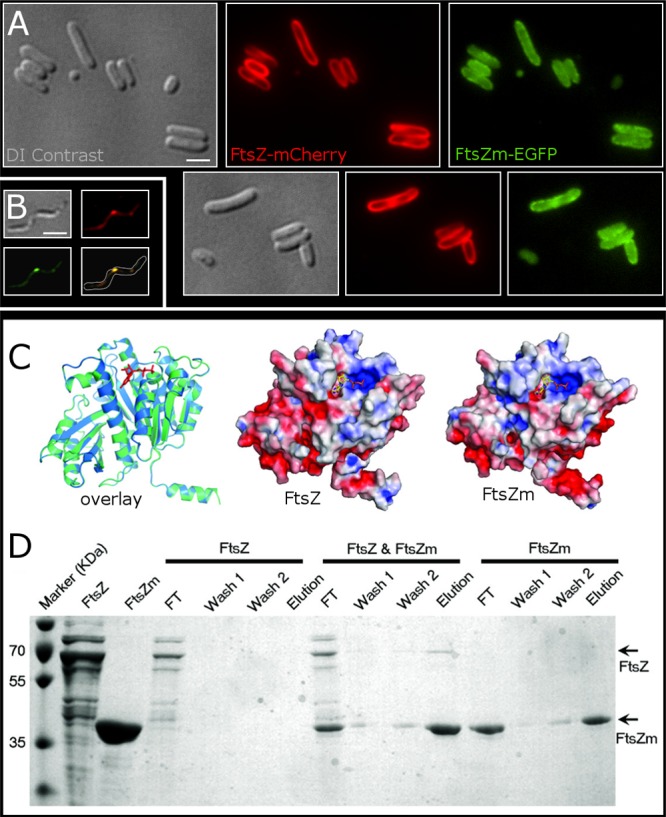

FIG 4.

Full-length FtsZ and FtsZm interact in vivo and in vitro. (A) Coexpression of FtsZ-mCherry and FtsZm-EGFP. The two proteins colocalize in a membrane-associated pattern, suggesting that FtsZ-mCherry (red) recruits FtsZm-EGFP (green) to the cytoplasmic membrane. Cells were imaged approximately 35 min after induction with IPTG (1 mM) coinciding with the onset of cell filamentation. DI contrast, differential interference contrast. (B) Coexpression of FtsZ-EGFP and FtsZm-mCherry in MSR-1. The two fluorescence signals colocalize in a lateral spot at midcell. Cells were imaged 5 h after induction with IPTG. Scale bar, 1 μm. (C) Overlapped homology models of FtsZ (blue) and FtsZm (green) from MSR-1 represented in a ribbon diagram with GDP shown as red sticks (left). FtsZ (middle) and FtsZm (right) electrostatic potentials are modeled on their molecular surfaces (red represents negative charges, and blue represents positive charges). (D) Interaction of full-length FtsZ with His-tagged FtsZm tested by binding to Ni-NTA. Individually or jointly polymerized FtsZ and FtsZm proteins were loaded onto a Ni-NTA column. Bound proteins were eluted and analyzed on a 12.5% SDS-polyacrylamide gel. FT, flowthrough.

Because of the missing C terminus in FtsZm, we asked whether FtsZ might recruit FtsZm to its position by direct interaction. Therefore, we developed FtsZ and FtsZm structural models. Based on E. coli FtsZ (Protein Data Bank accession number 1FSZ) (38), we first built homology models for FtsZ consisting of residues 1 to 43 [FtsZ(1–334)] and FtsZm(3–323). These models represent the typical tubulin/FtsZ domain without the C-terminal flexible tail (Fig. 4C). Since protein-protein interactions are based on their surface features and their complementary electrostatics, we examined the similarity of FtsZ to FtsZm. Based on their models, both structures are highly similar in their exposed surfaces, their electrostatic patches show similar charge distributions over the overall structures, and their GTP binding sites are identical (Fig. 4C). As these similarities suggested that FtsZ and FtsZm may interact in vivo and in vitro, we expressed both proteins separately in E. coli and tested their potential interaction by binding polymerized His-tagged FtsZm, polymerized FtsZ, and copolymerized His-FtsZm and FtsZ to Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid (NTA) beads, followed by extensive washing steps and protein elution (Fig. 4D). In the interaction experiment, we observed binding of FtsZ to Ni-NTA only when His-FtsZm was present, indicating an interaction of both proteins.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we reassessed the phenotype of the MSR-1 ftsZm mutant and traced the function of FtsZm and its relation to the unexplored full-length FtsZ in vivo and in vitro. We found that both MSR-1 FtsZ homologs share basic characteristics of FtsZ proteins such as the signature motif, GTP-dependent polymerization, and perturbation of cell division in E. coli and MSR-1 upon overexpression, and we found that localization of FtsZm likely depends on FtsZ. Our in vitro data support the assumption that both proteins are able to interact. Localization studies suggest that FtsZ- and FtsZm-mCherry concentrate at midcell in MSR-1 after induced ectopic gene expression and that chromosomally tagged FtsZm-mCherry localizes predominantly at midcell and at the cell pole. Importantly, we found that the reported effect of ftsZm on magnetite biomineralization disappears in the presence of nitrate, reminiscent of the recently reported phenotype of the mamX and mamZ mutants.

Potential interplay of FtsZ paralogs in other organisms and in MSR-1.

FtsZ proteins are essential factors in most bacteria. Heterologous FtsZ proteins typically do not complement and are deleterious to cells (39). Overexpression of native ftsZ genes likewise interferes with cell division. This suggests that in some alphaproteobacteria and other organisms, there must be a distinct means to enable coexistence of two or more FtsZ homologs. One such adaptation may be the loss of the C-terminal domain in all but one of these proteins. The truncated homolog(s) may then feed additional cues into the cell division process or adopt a function apart from cytokinesis while still possessing basic FtsZ properties.

Although remotely related, chloroplasts of algae, mosses, and higher plants utilize two to five FtsZ proteins to divide (40, 41). These FtsZ proteins play essential and nonredundant roles in plastid division. They colocalize in Z-rings in the chloroplast stroma underneath the envelope membrane, and they interact with different partner proteins (42). Chloroplast FtsZ proteins were shown to coassemble in vitro (43), and coassembly is strongly favored over self-assembly even when their ratios in assembly reactions are highly skewed (44). Fluorescently labeled FtsZ1 and FtsZ2 from Arabidopsis thaliana colocalize when coexpressed in fission yeast, and FtsZ2 determines shape and structure of these filaments (45). It has been suggested that coassembly may allow dynamic regulation of protofilament composition and morphology and the degree of bundling during constriction (44) and therefore help to divide the organelle. Thus, in chloroplasts, it seems that the multiplicity of FtsZ proteins is mainly devoted to plastid division.

The interaction of naturally cooccurring FtsZ proteins in bacteria, however, has been largely unexplored until now. The only other species for which two ftsZ paralogs have been investigated to some extent is S. meliloti (11, 46). The first homolog (FtsZ1) contains an extended C-terminal part (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material) and is likely essential. The second (FtsZ2) is C-terminally truncated, similar to FtsZm, and dispensable at least for axenic growth. Transcriptional analysis suggests that ftsZ2 becomes strongly expressed during root infection (13), i.e., under specific environmental conditions that include a shift toward microoxic conditions and increased iron requirement. However, the role of FtsZ2 is as yet unclear, and we are not aware of studies that dissected potential interactions between the FtsZ paralogs.

Transcriptional (22), proteomic (18), and Western blot analyses as well as fluorescence microscopy of chromosomally tagged ftsZm (this study) suggest that the gene is expressed in MSR-1. The protein has been found to hydrolyze GTP and to polymerize in vitro (22) (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). Taken together, these observations suggest that MSR-1 expresses two different ftsZ genes at the same time even under standard growth conditions. Moreover, both proteins are able to interact, as suggested by the colocalization in MSR-1, the membrane recruitment of FtsZm-EGFP in E. coli, and our in vitro experiments.

Our in vivo fluorescence data suggest that both FtsZ proteins accumulate and may also interact at midcell in MSR-1. Midcell localization of FtsZ in Caulobacter crescentus and likely in other alphaproteobacteria is mainly controlled by a gradient of the dimeric MipZ protein, which was shown to stimulate FtsZ GTP hydrolysis and depolymerization. Dimerization of MipZ is stimulated in the vicinity of the chromosomal origin of replication by interaction with DNA-bound ParB (36, 47). Formation of polymeric FtsZ structures is thereby restricted to midcell and new cell poles. Intriguingly, the same type of dynamic positioning is observed for the magnetosome chain, which becomes repositioned from the new cell pole to midcell after cytokinesis. This translocation seems to be congruent with the locations of FtsZ polymeric structures although it is not yet clear whether there exists a link between chain dynamics (imparted by MamK) (20) and FtsZ repositioning. However, the observed colocalization of FtsZ and MamK in E. coli may hint toward an interaction. Additional support for this hypothesis is lent by an ftsZ-mamK fusion gene which was found in a metagenomic clone library from enriched magnetotactic bacteria (48). Direct interactions of bacterial actin and tubulin homologs during cell growth and division are also known from other studies (16, 32, 49, 50).

Potential role of FtsZm in denitrification-dependent redox control for biomineralization.

Unexpectedly, deletion of ftsZm had neither an obvious effect on asymmetric septation and bending (19, 20) of dividing MSR-1 cells nor an influence on cell lengths under various culture conditions. This observation suggests that asymmetric division may be an intrinsic property of helical cells and is attributed either to other cell division genes (including the full-length FtsZ) or geometric cues of the spirillum (including the peptidoglycan sacculus). On the other hand, the observed properties of FtsZm in vitro and in vivo (22; also this study) suggest that the protein has all basic properties of true FtsZ proteins, such as nucleotide dependent polymerization, GTPase activity, and interference with cell division. These observations together with the colocalization and copolymerization suggest that FtsZm nevertheless interacts with the full-length FtsZ, and FtsZm likely receives its positional information from FtsZ.

The disturbed magnetosome formation in the absence of nitrate, however, indicates a functional link to denitrification, redox control, and magnetosomal iron homeostasis. Recently, it has been shown that dissimilatory denitrification is essential to form proper magnetosomes under microaerobic conditions (51). A nitrate reductase nap mutant formed small and poorly crystallized magnetite reminiscent of that of the ftsZm mutant but, in contrast to the latter, also in the presence of nitrate. It has been suggested that one of the main functions of Nap is to maintain the cellular redox balance by dissipating excess reductant with nitrate as an ancillary oxidant. The similar nap mutant phenotype and the genomic context of ftsZm hint to a potential role of the FtsZm protein in magnetosomal iron homeostasis, possibly dependent on redox conditions. More precisely, the protein could function in fine-tuning the magnetosomal Fe2+/Fe3+ ratio to ensure continuous coprecipitation of ferrous and ferric iron to form magnetite under changing environmental conditions. This assumed function suggests direct or indirect interaction of FtsZm with a redox-active system. Interestingly, such a type of interaction has been shown recently in C. crescentus, where the NAD(H)-binding protein KidO promotes FtsZ disassembly, thereby linking redox sensing to cell division (52). Assuming that FtsZm is involved in redox-dependent magnetosomal iron homeostasis, accessory redox-responsive proteins are to be considered. Conspicuously, the upstream genes mamX and mamZ code for proteins which contain heme c and b binding motifs, a putative iron reductase domain, and may be part of a transport system. Both genes are transcribed together with ftsZm (22), and, indeed, recent work demonstrated a biomineralization defect in the mamX and mamZ mutants which could be rescued by nitrate, reminiscent of the ftsZm mutant phenotype (31). These results suggest that ftsZm primarily functions in a pathway that is needed to circumvent nitrate-dependent iron oxidation by other reactions. Since it appears unlikely that FtsZm directly mediates redox processes, it may function as a scaffolding factor in organizing redox-active protein complexes or—by interaction with FtsZ—provide positional information to the enzymes involved in electron transport.

Interestingly, the genomic context of the ftsZm-like gene ftsZ2 in S. meliloti resembles that of ftsZm in that it likely belongs to an operon coding for a putative iron transport system. Increased transcription of ftsZ2 in bacteroids has been observed by Gao and Teplitski (13). The microoxic root nodule represents a very discrete environment, particularly with respect to the availability of electron acceptors and redox conditions. Symbiosis and nitrogen fixation in this environment may be linked to alternative reductant flows as well, and it requires efficient uptake of iron from the peribacteroid space (53). Interestingly, Fe2+ is transported more efficiently into the symbiosome than Fe3+, but Fe3+ uptake is stimulated by NADH (54, 55). It would be interesting to see whether deletion of ftsZ2 in S. meliloti affects iron uptake in bacteroids.

In conclusion, our findings point toward a novel function of bacterial tubulin homologs apart from cell cycle control and cell division. Future studies should dissect these interactions and analyze their physiological roles in detail.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Isabelle Mai for technical assistance.

This research was supported by grant DFG Schu 1080/9-1.

We declare that we have no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 22 November 2013

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/JB.00804-13.

REFERENCES

- 1.Murat D, Byrne M, Komeili A. 2010. Cell biology of prokaryotic organelles. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2:a000422. 10.1101/cshperspect.a000422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Komeili A, Li Z, Newman DK, Jensen GJ. 2006. Magnetosomes are cell membrane invaginations organized by the actin-like protein MamK. Science 311:242–245. 10.1126/science.1123231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pradel N, Santini C-L, Bernadac A, Fukumori Y, Wu L-F. 2006. Biogenesis of actin-like bacterial cytoskeletal filaments destined for positioning prokaryotic magnetic organelles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103:17485–17489. 10.1073/pnas.0603760103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scheffel A, Gruska M, Faivre D, Linaroudis A, Plitzko JM, Schüler D. 2006. An acidic protein aligns magnetosomes along a filamentous structure in magnetotactic bacteria. Nature 440:110–114. 10.1038/nature04382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Katzmann E, Scheffel A, Gruska M, Plitzko JM, Schüler D. 2010. Loss of the actin-like protein MamK has pleiotropic effects on magnetosome formation and chain assembly in Magnetospirillum gryphiswaldense. Mol. Microbiol. 77:208–224. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07202.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bi EF, Lutkenhaus J. 1991. FtsZ ring structure associated with division in Escherichia coli. Nature 354:161–164. 10.1038/354161a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Den Blaauwen T, de Pedro MA, Nguyen-Distèche M, Ayala JA. 2008. Morphogenesis of rod-shaped sacculi. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 32:321–344. 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2007.00090.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goley ED, Yeh Y, Hong S, Fero MJ, Abeliuk E, McAdams HH, Shapiro L. 2011. Assembly of the Caulobacter cell division machine. Mol. Microbiol. 80:1680–1698. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07677.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Erickson HP, Anderson DE, Osawa M. 2010. FtsZ in bacterial cytokinesis: cytoskeleton and force generator all in one. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 74:504–528. 10.1128/MMBR.00021-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kirkpatrick CL, Viollier PH. 2011. New(s) to the (Z-) ring. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 14:691–697. 10.1016/j.mib.2011.09.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Margolin W, Long SR. 1994. Rhizobium meliloti contains a novel second homolog of the cell division gene ftsZ. J. Bacteriol. 176:2033–2043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vaughan S, Wickstead B, Gull K, Addinall SG. 2004. Molecular evolution of Ftsz protein sequences encoded within the genomes of archaea, bacteria, and eukaryota. J. Mol. Evol. 58:19–29. 10.1007/s00239-003-2523-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gao M, Teplitski M. 2008. RIVET—a tool for in vivo analysis of symbiotically relevant gene expression in Sinorhizobium meliloti. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 21:162–170. 10.1094/MPMI-21-2-0162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shakhatreh MAK, Robinson JB. 2012. The cell division gene ftsZ2 of Sinorhizobium meliloti is expressed at high levels in host plant Medicago trunculata nodules in the absence of sinI. Afr. J. Microbiol. Res. 6:499–503. 10.5897/AJMR11.015 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Margolin W, Corbo JC, Long SR. 1991. Cloning and characterization of a Rhizobium meliloti homolog of the Escherichia coli cell division gene ftsZ. J. Bacteriol. 173:5822–5830 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ma X, Ehrhardt DW, Margolin W. 1996. Colocalization of cell division proteins FtsZ and FtsA to cytoskeletal structures in living Escherichia coli cells by using green fluorescent protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 93:12998. 10.1073/pnas.93.23.12998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Richter M, Kube M, Bazylinski DA, Lombardot T, Glöckner FO, Reinhardt R, Schüler D. 2007. Comparative genome analysis of four magnetotactic bacteria reveals a complex set of group-specific genes implicated in magnetosome biomineralization and function. J. Bacteriol. 189:4899–4910. 10.1128/JB.00119-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lohße A, Ullrich S, Katzmann E, Borg S, Wanner G, Richter M, Voigt B, Schweder T, Schüler D. 2011. Functional analysis of the magnetosome island in Magnetospirillum gryphiswaldense: the mamAB operon is sufficient for magnetite biomineralization. PLoS One 6:e25561. 10.1371/journal.pone.0025561 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Staniland SS, Moisescu C, Benning LG. 2010. Cell division in magnetotactic bacteria splits magnetosome chain in half. J. Basic Microbiol. 50:392–396. 10.1002/jobm.200900408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Katzmann E, Müller FD, Lang C, Messerer M, Winklhofer M, Plitzko JM, Schüler D. 2011. Magnetosome chains are recruited to cellular division sites and split by asymmetric septation. Mol. Microbiol. 82:1316–1329. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07874.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Draper O, Byrne ME, Li Z, Keyhani S, Barrozo JC, Jensen G, Komeili A. 2011. MamK, a bacterial actin, forms dynamic filaments in vivo that are regulated by the acidic proteins MamJ and LimJ. Mol. Microbiol. 82:342–354. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07815.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ding Y, Li J, Liu J, Yang J, Jiang W, Tian J, Li Y, Pan Y, Li J. 2010. Deletion of the ftsZ-like gene results in the production of superparamagnetic magnetite magnetosomes in Magnetospirillum gryphiswaldense. J. Bacteriol. 192:1097–1105. 10.1128/JB.01292-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heyen U, Schüler D. 2003. Growth and magnetosome formation by microaerophilic Magnetospirillum strains in an oxygen-controlled fermentor. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 61:536–544. 10.1007/s00253-002-1219-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Faivre D, Menguy N, Pósfai M, Schüler D. 2008. Environmental parameters affect the physical properties of fast-growing magnetosomes. Am. Mineral. 93:463–469. 10.2138/am.2008.2678 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schüler D, Uhl R, Bäuerlein E. 1995. A simple light scattering method to assay magnetism in Magnetospirillum gryphiswaldense. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 132:139–145. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1995.tb07823.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schultheiss D, Schüler D. 2003. Development of a genetic system for Magnetospirillum gryphiswaldense. Arch. Microbiol. 179:89–94. 10.1007/s00203-002-0498-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ullrich S, Schüler D. 2010. Cre-lox-based method for generation of large deletions within the genomic magnetosome island of Magnetospirillum gryphiswaldense. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 76:2439–2444. 10.1128/AEM.02805-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. 1990. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 215:403–410. 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tamura K, Dudley J, Nei M, Kumar S. 2007. MEGA4: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis (MEGA) software version 4.0. Mol. Biol. Evol. 24:1596–1599. 10.1093/molbev/msm092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Montanini B, Blaudez D, Jeandroz S, Sanders D, Chalot M. 2007. Phylogenetic and functional analysis of the cation diffusion facilitator (CDF) family: improved signature and prediction of substrate specificity. BMC Genomics 8:107. 10.1186/1471-2164-8-107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Raschdorf O, Müller FD, Pósfai M, Plitzko JM, Schüler D. 2013. The magnetosome proteins MamX, MamZ and MamH are involved in redox control of magnetite biomineralization in Magnetospirillum gryphiswaldense. Mol. Microbiol. 89:872–886. 10.1111/mmi.12317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yan K, Pearce KH, Payne DJ. 2000. A Conserved Residue at the extreme C terminus of FtsZ is critical for the FtsA-FtsZ interaction in Staphylococcus aureus. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 270:387–392. 10.1006/bbrc.2000.2439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lang C, Schüler D. 2008. Expression of green fluorescent protein fused to magnetosome proteins in microaerophilic magnetotactic bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74:4944–4953. 10.1128/AEM.00231-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lang C, Pollithy A, Schüler D. 2009. Identification of promoters for efficient gene expression in Magnetospirillum gryphiswaldense. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75:4206–4210. 10.1128/AEM.02906-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schübbe S, Kube M, Scheffel A, Wawer C, Heyen U, Meyerdierks A, Madkour MH, Mayer F, Reinhardt R, Schüler D. 2003. Characterization of a spontaneous nonmagnetic mutant of Magnetospirillum gryphiswaldense reveals a large deletion comprising a putative magnetosome island. J. Bacteriol. 185:5779–5790. 10.1128/JB.185.19.5779-5790.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thanbichler M, Shapiro L. 2006. MipZ, a spatial regulator coordinating chromosome segregation with cell division in Caulobacter. Cell 126:147–162. 10.1016/j.cell.2006.05.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zupan JR, Cameron TA, Anderson-Furgeson J, Zambryski PC. 2013. Dynamic FtsA and FtsZ localization and outer membrane alterations during polar growth and cell division in Agrobacterium tumefaciens. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 110:9060–9065. 10.1073/pnas.1307241110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Löwe J, Amos LA. 1998. Crystal structure of the bacterial cell-division protein FtsZ. Nature 391:203–206. 10.1038/34472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Osawa M, Erickson HP. 2006. FtsZ from divergent foreign bacteria can function for cell division in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 188:7132–7140. 10.1128/JB.00647-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Martin A, Lang D, Heckmann J, Zimmer AD, Vervliet-Scheebaum M, Reski R. 2009. A uniquely high number of ftsZ genes in the moss Physcomitrella patens. Plant Biol. (Stuttg.) 11:744–750. 10.1111/j.1438-8677.2008.00174.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Miyagishima S. 2011. Mechanism of plastid division: from a bacterium to an organelle. Plant Physiol. 155:1533–1544. 10.1104/pp.110.170688 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Maple J, Aldridge C, Møller SG. 2005. Plastid division is mediated by combinatorial assembly of plastid division proteins. Plant J. 43:811–823. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02493.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Smith AG, Johnson CB, Vitha S, Holzenburg A. 2010. Plant FtsZ1 and FtsZ2 expressed in a eukaryotic host: GTPase activity and self-assembly. FEBS Lett. 584:166–172. 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.11.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Olson BJSC, Wang Q, Osteryoung KW. 2010. GTP-dependent heteropolymer formation and bundling of chloroplast FtsZ1 and FtsZ2. J. Biol. Chem. 285:20634–20643. 10.1074/jbc.M110.122614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.TerBush AD, Osteryoung KW. 2012. Distinct functions of chloroplast FtsZ1 and FtsZ2 in Z-ring structure and remodeling. J. Cell Biol. 199:623–637. 10.1083/jcb.201205114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Galibert F, Finan TM, Long SR, et al. 2001. The composite genome of the legume symbiont Sinorhizobium meliloti. Science 293:668–672. 10.1126/science.1060966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kiekebusch D, Michie KA, Essen L-O, Löwe J, Thanbichler M. 2012. Localized dimerization and nucleoid binding drive gradient formation by the bacterial cell division inhibitor MipZ. Mol. Cell 46:245–259. 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.03.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jogler C, Lin W, Meyerdierks A, Kube M, Katzmann E, Flies C, Pan Y, Amann R, Reinhardt R, Schüler D. 2009. Toward cloning of the magnetotactic metagenome: identification of magnetosome island gene clusters in uncultivated magnetotactic bacteria from different aquatic sediments. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75:3972–3979. 10.1128/AEM.02701-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fenton AK, Gerdes K. 2013. Direct interaction of FtsZ and MreB is required for septum synthesis and cell division in Escherichia coli. EMBO J. 32:1953–1965. 10.1038/emboj.2013.129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Szwedziak P, Wang Q, Freund SM, Löwe J. 2012. FtsA forms actin-like protofilaments. EMBO J. 31:2249–2260. 10.1038/emboj.2012.76 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Li Y, Katzmann E, Borg S, Schüler D. 2012. The periplasmic nitrate reductase nap is required for anaerobic growth and involved in redox control of magnetite biomineralization in Magnetospirillum gryphiswaldense. J. Bacteriol. 194:4847–4856. 10.1128/JB.00903-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Radhakrishnan SK, Pritchard S, Viollier PH. 2010. Coupling prokaryotic cell fate and division control with a bifunctional and oscillating oxidoreductase homolog. Dev. Cell 18:90–101. 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.10.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kaiser BN, Moreau S, Castelli J, Thomson R, Lambert A, Bogliolo S, Puppo A, Day DA. 2003. The soybean NRAMP homologue, GmDMT1, is a symbiotic divalent metal transporter capable of ferrous iron transport. Plant J. 35:295–304. 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2003.01802.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.LeVier K, Day DA, Guerinot ML. 1996. Iron uptake by symbiosomes from soybean root nodules. Plant Physiol. 111:893–900 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Moreau S, Day DA, Puppo A. 1998. Ferrous iron is transported across the peribacteroid membrane of soybean nodules. Planta 207:83–87. 10.1007/s004250050458 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.