Abstract

The chemolithoautotrophic bacterium Nitrosospira multiformis is involved in affecting the process of nitrogen cycling. Here we report the existence and characterization of a functional quorum sensing signal synthase in N. multiformis. One gene (nmuI) playing a role in generating a protein with high levels of similarity to N-acyl homoserine lactone (AHL) synthase protein families was identified. Two AHLs (C14-AHL and 3-oxo-C14-AHL) were detected using an AHL biosensor and liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) when nmuI, producing a LuxI homologue, was introduced into Escherichia coli. However, by extracting N. multiformis culture supernatants with acidified ethyl acetate, no AHL product was obtained that was capable of activating the biosensor or being detected by LC-MS. According to reverse transcription-PCR, the nmuI gene is transcribed in N. multiformis, and a LuxR homolog (NmuR) in this ammonia-oxidizing strain showed great sensitivity to long-chain AHL signals by solubility assay. A degradation experiment demonstrated that the absence of AHL signals might be attributed to the possible AHL-inactivating activities of this strain. To summarize, an AHL synthase gene (nmuI) acting as a long-chain AHL producer has been found in a chemolithotrophic ammonia-oxidizing microorganism, and the results provide an opportunity to complete the knowledge of the regulatory networks in N. multiformis.

INTRODUCTION

Quorum sensing (QS) is a form of cell-cell communication that regulates gene expression in response to fluctuations in cell density. QS bacteria can alter their behavior through producing, releasing, and responding to autoinducing signaling molecules that accumulate in the environment (1). A variety of physiological functions, including biofilm formation, bioluminescence, virulence, swarming, plasmid transfer, and antibiotic biosynthesis, are subject to QS regulation (1–3). In Gram-negative bacteria, several signal molecules have now been identified, such as N-acyl homoserine lactones (AHLs), quinolone, p-coumarate, and 3-OH palmitic acid methyl ester (3-OH PAME), and the AHLs have probably been the most intensively investigated of these (3, 4). In the currently accepted LuxI/LuxR-type regulatory system of QS, AHL biosynthesis depends primarily on a synthase protein (I protein), and target genes are then activated via the interaction between the signal molecules and a response regulator protein (R protein) (1, 3, 5).

Nitrosospira multiformis is a chemolithoautotrophic bacterium that is capable of oxidizing ammonia to obtain energy for growth (6). The ecological importance of N. multiformis and other ammonia-oxidizing bacteria (AOB) is that they affect the biological oxidation of inorganic nitrogen compounds in the environment. During the ammonia oxidation process in water or soil, biofilm formed by AOB can greatly affect the nitrification efficiency and ecological behavior of nitrifying bacteria (7–9). In many Gram-negative bacteria, the QS process controls exopolysaccharide production and biofilm formation, which is mediated by an AHL autoinducer (10). However, only a few studies have shown the types of AHL signal molecules produced by Nitrosomonas europaea (11) and AOB biofilm activity regulated by an AHL-based communication system (12, 13). Knowledge of the QS regulatory system directly involved in AOB biofilm processes and other physiological functions is limited. Furthermore, the functional QS system of AOB has not been proved conclusively to date.

In the current study, we describe an AHL synthase (NmuI) of N. multiformis and the signal molecules produced by NmuI introduced into Escherichia coli. Two different types of AHLs were identified in the heterogeneous expression system by using a signal biosensor and liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS). By evaluating the QS activity in N. multiformis, our results suggest that the nmuI gene is functional in N. multiformis and that long-chain AHLs solubilized the R protein (NmuR) of N. multiformis in extracts of recombinant E. coli. Moreover, the absence of AHL signals in this strain might be attributed to possible AHL-inactivating activities.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth media.

N. multiformis (ATCC 25196) was grown in ATCC medium 929 at 26°C in the dark as described previously (14). N. multiformis cultures were subcultured into fresh medium after the pH had been adjusted three times, and cells were also harvested from a 5-liter fermentor in fed-batch cultivation. (NH4)2SO4 was supplied in a fed-batch manner from stock solution so that its concentration was no less than 10 mM. The pH and aeration of the reactor were further controlled at 7.5 and 0.1 liter/min, respectively. E. coli strain BL21(DE3)/pLysS and derivatives of this strain were grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium and, where required, ampicillin (100 μg/ml) or kanamycin (50 μg/ml). Agrobacterium tumefaciens A136 was incubated on LB medium plus tetracycline (4.5 μg/ml) and spectinomycin (50 μg/ml) at 30°C.

Bioinformatic analyses.

To identify genes encoding AHL synthases and transcriptional activators, the genome of N. multiformis, which was made available by the BLAST program (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov), was searched for genes with similarity to all QS-related genes. With the SWISS-MODEL server (http://swissmodel.expasy.org/), Clustal W2 (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/clustalw2/), and the Swiss Protein Data Bank (PDB) viewer (http://www.expasy.ch/spdbv/), amino acid sequence alignments were achieved, and a three-dimensional homology model of NmuI was automatically created by using the LasI structure as a template.

DNA manipulations.

Genomic DNA isolated from N. multiformis was used as the template for nmuI gene amplification with the primers 5′-CAGGATCCATGCTTGCACAACATGGCA-3′ (5′ end) and 5′-CCGCTCGAGTCATGCGGCCTTCCTTTG-3′ (3′ end). The 5′-end primer included a BamHI restriction site, and the 3′-end primer included an XhoI restriction site (underlined). PCR was performed by incubation for 2 min at 95°C followed by 30 cycles of 30 s at 95°C, 30 s at 51°C, and 1 min at 72°C, with a final step of 10 min at 72°C. Amplified nmuI was cloned into pGEX-4T-1 (GE) as described by the manufacturer, and the resulting recombinant plasmid was termed pGEX-nmuI. We also created the LuxR homolog protein (NmuR) expression plasmid pET-R. The NmuR gene was amplified with the primers 5′-CCGGAATTCATGGATAACTTGACCTTATTC-3′ (5′ end) and 5′-CCGCTCGAGCTAGCGAATCGTACGGGG-3′ (3′ end). The 5′-end primer included an EcoRI restriction site, and the 3′-end primer included an XhoI restriction site (underlined). PCR was performed by the procedure described above. The amplified DNA fragment was cloned into pET-30a (+) (Novagen) as described by the supplier, and the resulting recombinant plasmid was termed pET-R. pGEX-nmuI and pET-R were transformed into E. coli BL21(DE3)/pLysS, and the transformants were grown on LB medium containing ampicillin (100 μg/ml) and kanamycin (50 μg/ml), respectively, at 37°C. Details of the characteristics of bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are shown in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristics | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| Nitrosospira multiformis ATCC 25196 | Type strain | ATCC |

| Escherichia coli BL21(DE3)/pLysS | F− ompT hsdSB(rB− mB−) dcm gal λ(DE3) pLysS Cmr | Promega |

| Agrobacterium tumefaciens A136(pCF218)(pCF372) | traI-lacZ fusion; AHL biosensor | 15 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pGEX-4T-1 | E. coli cloning and expression vector | GE |

| pET-30a (+) | T7 expression vector | Novagen |

| pGEX-nmuI | nmuI of N. multiformis expressed from pGEX-4T-1 tac promoter | This study |

| pET-R | pET-30a (+) containing the AHL receptor gene | This study |

AHL reporter plate assays and LC-MS analysis.

The bacterial cells and supernatants were extracted three times with half a volume of acidified ethyl acetate (EtAc) containing 0.2% glacial acetic acid. Supernatant was dried by N2 gas and the residue reconstituted in high-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC)-grade acetonitrile. The extracts were spotted onto overlaid LB agar plates (containing 80 μg/ml 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside [X-Gal]) mixed with the AHL reporter strain A. tumefaciens A136 (15) and incubated overnight at 30°C. AHL profiling was confirmed by use of a Waters Micromass Q-TOF micromass spectrometer (LC-MS) system using a C18 reverse-phase column (5 μm by 250 mm by 4.6 mm) (Zorbax Eclipse XDB-C18; Agilent) coupled with positive-ion electrospray ionization (ESI) mass spectrometry (16). The elution procedure consisted of an isocratic profile of acetonitrile-water (60:40 [vol/vol]) for 10 min followed by a linear gradient from 60 to 100% acetonitrile in water over 18 min and an isocratic profile over 22 min. ESI spectra (m/z range, 50 to 400) containing a fragment product at m/z 102 were compared for retention time and spectral properties to the corresponding synthetic AHL standards. All detected AHL standards were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich.

To determine whether AHLs were inactivated by N. multiformis, the strain and medium solution were incubated with 10 μM long-chain AHLs (C14-AHL and 3-oxo-C14-AHL) for 0 h, 4 h, or 8 h, after which the culture supernatants were spotted onto AHL reporter plates (see above). The residual AHLs were detected by use of A. tumefaciens A136.

RNA manipulations.

To study if nmuI and nmuR were functional in N. multiformis, gene expression was analyzed by reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR). Total RNA was extracted from the bacterial culture during exponential growth by using TRIzol reagent (Life Technologies) according to the manufacturer's protocol. RT-PCR was performed using a PrimeScript One-Step RT-PCR kit (TaKaRa Bio) with the primers 5′-ATGCTTGCACAACATGGCA-3′ (5′ end) and 5′-TCATGCGGCCTTCCTTTG-3′ (3′ end) for nmuI and 5′-ATGGATAACTTGACCTTATTC-3′ (5′ end) and 5′-CTAGCGAATCGTACGGGG-3′ (3′ end) for nmuR. The RT-PCR steps were performed by the same procedure for nmuI and nmuR. The reaction mixture was initially incubated at 50°C for 30 min and denatured at 94°C for 2 min, followed by 30 cycles of 30 s at 94°C, 30 s at 51°C, and 1 min at 72°C. A control treated with RNase before RT-PCR was carried out to check if the RNA products contained genomic DNA. RT-PCR products were checked by electrophoresis performed at 100 V on a 1% agarose gel.

Assessing the solubility of NmuR.

E. coli BL21(DE3)/pLysS containing pET-R was cultured at 28°C in 50 ml of LB broth containing 50 μg kanamycin per ml and 5 μM C14-AHL plus 3-oxo-C14-AHL, 5 μM C12-AHL plus 3-oxo-C12-AHL, or no AHL, as indicated. When cultures reached an optical density at 600 nm of 0.6, 200 μM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) was added to induce NmuR expression. Incubation was continued at 28°C for 4 h, and the total cell lysates and soluble and pellet fractions were collected according to a published protocol (17). The total, soluble, and insoluble protein fractions were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). Samples were electrophoresed with a 12% gel concentration and stained with Coomassie brilliant blue G-250.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The nucleotide sequences of nmuI and nmuR have been deposited in GenBank under accession numbers KF030793 and KF806554, respectively.

RESULTS

Characterization of the novel LuxI homolog NmuI.

Although quorum sensing was first described for the LuxI/LuxR system of Gram-negative bacteria, other AHL synthase families have been characterized, namely, the AinS family and the HdtS family (18). We used a previously described strategy to search for genes with similarity to all QS-related genes. An ortholog of AHL synthases (Nmul_A2390) was found in N. multiformis (ATCC 25196) only for the LuxI family.

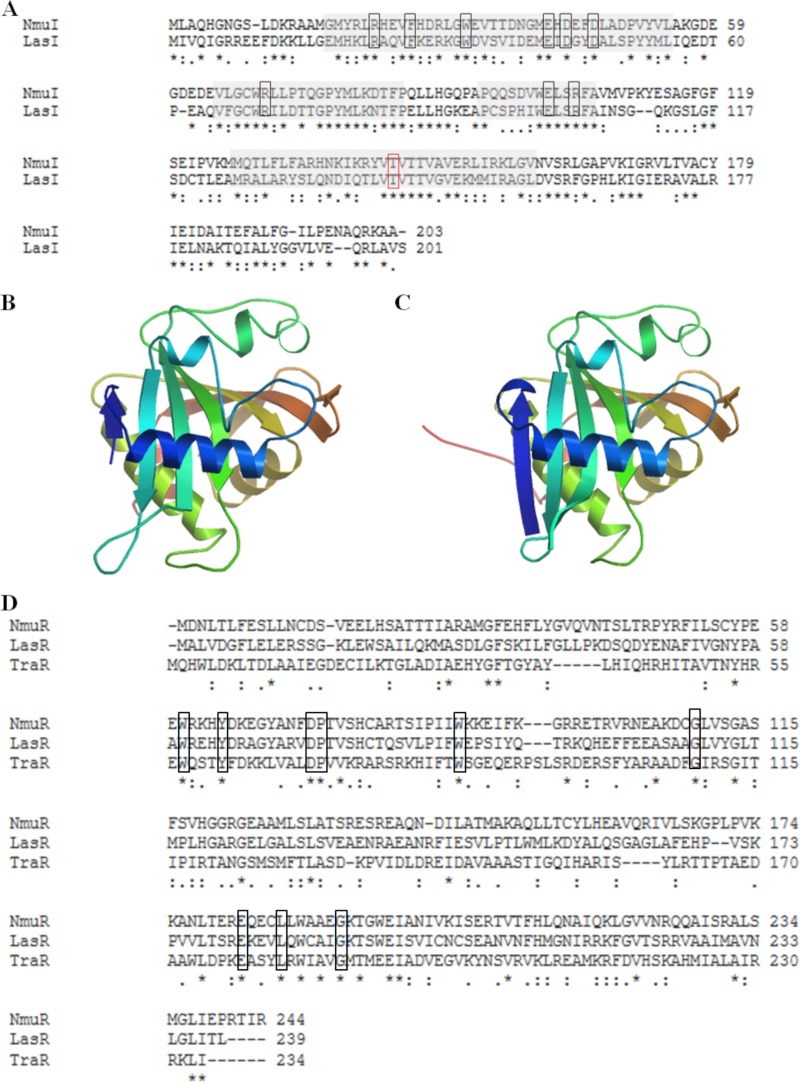

The open reading frame (ORF) (Nmul_A2390) coded for a protein that was 44% similar to the LasI protein from Pseudomonas aeruginosa (Fig. 1A). The LuxI homologue LasI in P. aeruginosa was identified as directing the synthesis of the autoinducer 3-oxo-C12-AHL (19). The homologous protein in N. multiformis was termed NmuI, and it had 203 amino acids, a molecular mass of 22.9 kDa, and a theoretical isoelectric point of 6.08. The amino acid sequence of the AHL synthase NmuI was compared to that of LasI (Fig. 1A), and the alignment showed a conserved sequence for this group of proteins, based on the previous work of Watson et al. (20) and Schaefer et al. (21). These conserved residues are important for the active sites, including a threonine residue (red box in Fig. 1A) that influences synthesis of the 3-oxo-AHLs by reacting with 3-oxo-acyl acyl carrier proteins (ACPs) (20). We obtained a three-dimensional structure of NmuI with a high degree of homology and structural similarity to LasI (Fig. 1B and C) by using the protein homology modeling server SWISS-MODEL (22–24).

FIG 1.

Sequence and structural alignment of NmuI and NmuR. (A) The amino acid sequence of NmuI was compared to that of the AHL synthase LasI. The gray shaded blocks show conserved sequence regions in NmuI and LasI. Identical and similar amino acid residues in the two proteins are indicated by asterisks and colons, respectively, and nine completely conserved residues in the LuxI family are highlighted in black boxes. The residue framed in red is related to 3-oxo-AHL synthesis. The three-dimensional structure of NmuI (B) was based on the experimental structure of LasI (C). (D) The amino acid sequence of NmuR was compared to those of LasR of P. aeruginosa and TraR of A. tumefaciens. The nine highly conserved amino acids in LuxR homologs are highlighted in black boxes.

Identification of nmuI gene responsible for AHL production.

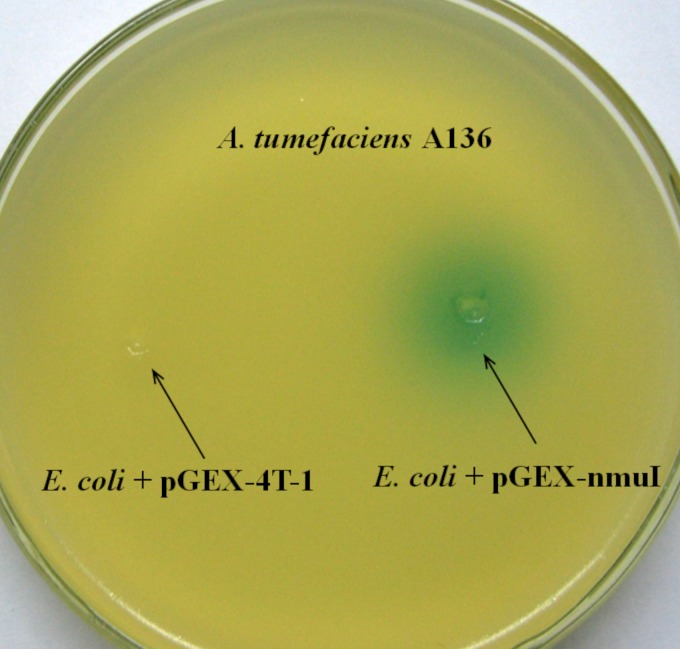

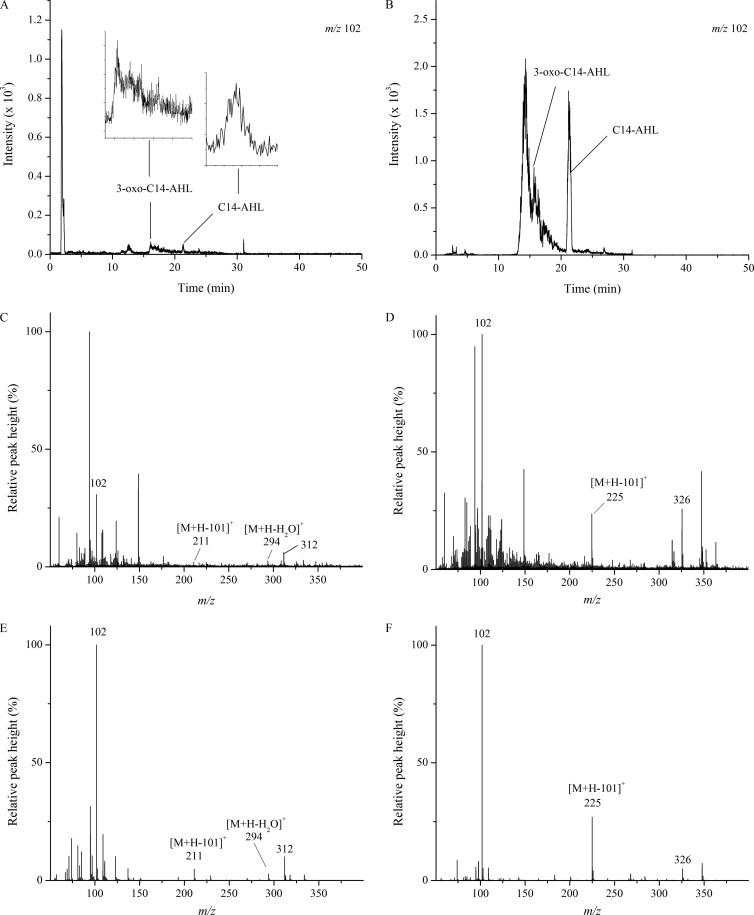

To identify that the nmuI gene product was an AHL synthase, the expression of nmuI was examined in an E. coli strain which does not produce AHLs. The nmuI gene, which was confirmed by sequence analysis, was cloned into the plasmid pGEX-4T-1 and transformed into the E. coli BL21(DE3)/pLysS strain. In a plate assay, the A. tumefaciens A136 biosensor detected AHLs from a recombinant E. coli culture extract induced with 0.4 M isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) for 1 h (25). Signals were obtained from the recombinant sample as a blue stain on the indicator plate, while no activity was observed for spent extract of the control E. coli strain carrying pGEX-4T-1 without the nmuI gene (Fig. 2). This suggested that nmuI from N. multiformis encoded an enzyme with homoserine lactone synthase function that was able to synthesize AHLs and oxo-AHLs with long acyl chains when expressed in the heterologous host E. coli BL21(DE3)/pLysS. Putative AHLs in the recombinant extract were confirmed by comparing the retention times and mass spectra from LC-MS with those of standard AHLs. Figure 3 shows that two compounds, with molecular ions [M + H] of m/z 312 and 326, corresponding to C14-AHL and 3-oxo-C14-AHL, respectively, were clearly identified, indicating that NmuI could direct the synthesis of the two N. multiformis AHLs. None of these AHLs were found in the control E. coli strain carrying the pGEX-4T-1 vector without the nmuI gene (data not shown).

FIG 2.

Bioassay for AHL activity of N. multiformis NmuI. An extract from the recombinant E. coli strain containing pGEX-nmuI was recognized by the reporter strain A. tumefaciens A136 (blue stain). The blank control, E. coli with pGEX-4T-1, had no effect on the AHL biosensor strain.

FIG 3.

LC-MS chromatograms for AHLs occurring in E. coli containing pGEX-nmuI and for AHL standards. (A) Chromatogram of the lactone moiety at m/z 102 from a recombinant E. coli strain culture extract. The inset graphs show amplified chromatograms for the corresponding peaks. (B) Selected ion (m/z 102) chromatograms for C14-AHL and 3-oxo-C14-AHL standards. (C and D) The mass spectra of extracts from recombinant E. coli with pGEX-nmuI reveal molecular ions [M + H] of m/z 312 and 326. The comparable fragmentation products with their respective m/z are labeled. (E and F) The fragmentation patterns of the strain extract were consistent with those of the C14-AHL (E) and 3-oxo-C14-AHL (F) standards.

Solubility of NmuR overexpressed with long-chain AHLs.

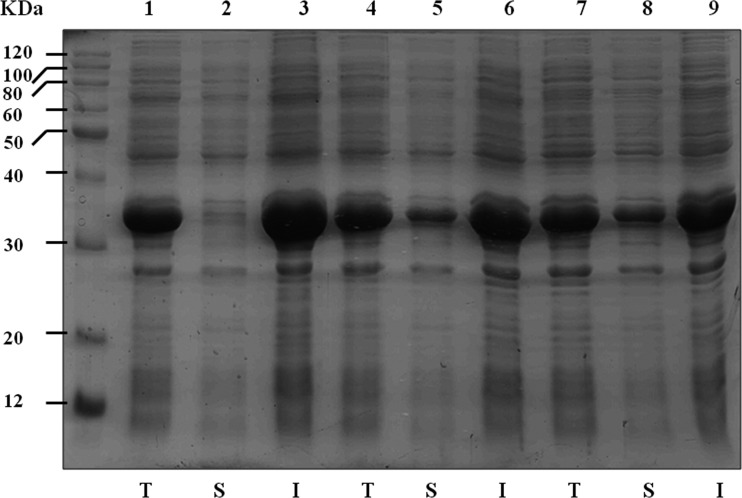

In N. multiformis, one LuxR homolog (Nmul_A2417) was predicted to contain an autoinducer binding domain (pfam03472), named NmuR. Sequence alignments revealed that the reported nine highly conserved amino acid residues shared by most LuxR-type proteins are included in NmuR (Fig. 1D) (26). The I/R QS system is required for activation by LuxR and its homologs, and the active form of these transcription factors requires their cognate signals or closely related AHLs (17, 27). It is clear that appropriate signal binding is necessary for LuxR homologs in soluble form (5). We wanted to test the hypothesis that C14-AHL and 3-oxo-C14-AHL were NmuR cognate signals in N. multiformis. The R protein was overexpressed in E. coli strain BL21(DE3)/pLysS by using a T7 protein expression system in the absence of AHLs, but in cell extracts, all of the NmuR protein was found in the particulate fraction, while a proportion of the overexpressed polypeptide was in the soluble fraction in the presence of 5 μM C14-AHL and 3-oxo-C14-AHL (Fig. 4). Interestingly, there was more soluble protein when NmuR was expressed in medium containing C12-AHL and 3-oxo-C12-AHL than when the cells were grown in the presence of C14-AHL and 3-oxo-C14-AHL. Although the experiment supports the conclusion that there is a possible QS circuit encoded in the N. multiformis genome, the difference in ability to increase NmuR solubility might reflect another potential chemical information network.

FIG 4.

Solubility of NmuR in extracts of recombinant E. coli. Cells of E. coli BL21(DE3)/pLysS containing the vector pET-R carrying nmuR were cultured in LB medium in the presence or absence of 5 μM AHLs. SDS-PAGE was used to show cell lysates with different treatments. Lanes: left, molecular mass markers, in kDa; 1, 2, and 3, no AHLs in medium; 4, 5, and 6, C14-AHL and 3-oxo-C14-AHL in medium; 7, 8, and 9, C12-AHL and 3-oxo-C12-AHL in medium. T, S, and I, total, soluble, and insoluble fractions of the cell lysates, respectively. The predicted molecular mass of NmuR (27.5 kDa plus tag of pET-30a) is 32.3 kDa.

AHL synthesis and degradation in N. multiformis.

We hoped to obtain AHL signals from cell cultures of the N. multiformis strain, but the results from the A. tumefaciens A136 bioassay and LC-MS showed that extracts derived from both batch culture (exponential phase; about 12 days of incubation) and fed-batch culture (quasi-steady state; ∼3 × 106 cells/ml) of the N. multiformis strain did not yield a product related to AHLs under our experimental conditions (data not shown).

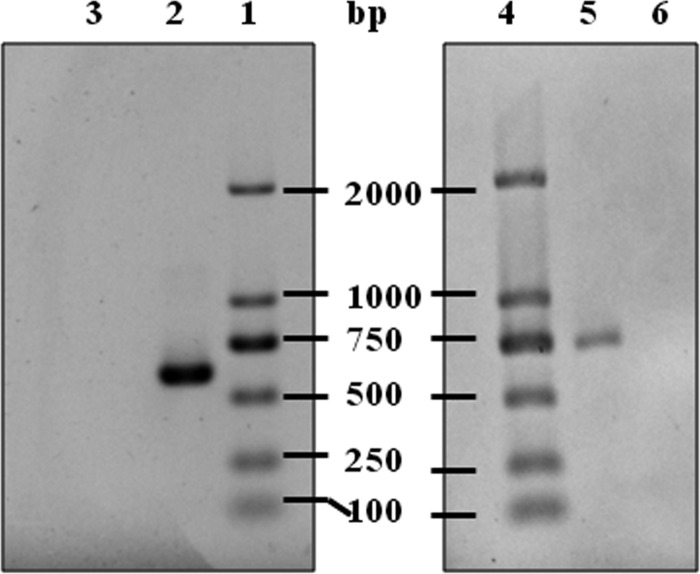

To determine whether NmuI and NmuR were functional in N. multiformis, gene expression was analyzed by RT-PCR. Total RNA was harvested from stationary-phase cells of N. multiformis grown at 26°C. The results of RT-PCR clearly showed that nmuI and nmuR were expressed in N. multiformis, and no amplification products were detected in the RNA sample subjected to RNase treatment (Fig. 5).

FIG 5.

RT-PCR analysis of mRNA production for nmuI and nmuR in N. multiformis. Contamination of the RNA sample by genomic DNA was excluded by RNase treatment. Lanes: 1 and 4, molecular mass markers; 2 and 5, transcription analysis of nmuI (lane 2) and nmuR (lane 5) by RT-PCR; 3 and 6, transcription analysis of nmuI (lane 3) and nmuR (lane 6) by RT-PCR with RNase treatment. The 612-bp nmuI and 735-bp nmuR products are clearly visible in lanes 2 and 5, respectively.

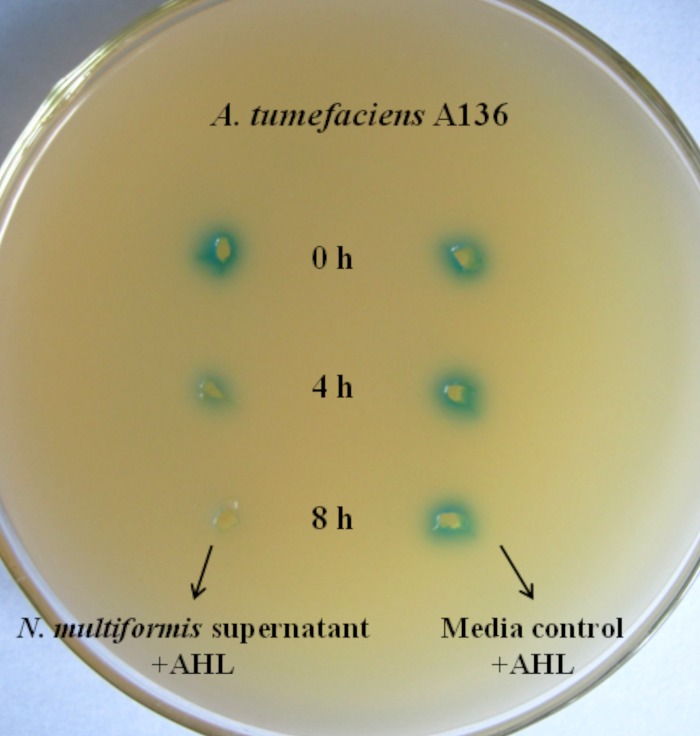

Since the AHLs were absent in the N. multiformis culture, we analyzed whether there might be AHL-degrading capacities in this strain. When provided with 10 μM C14-AHL and 3-oxo-C14-AHL as cosubstrates in N. multiformis culture medium, the strain showed the capacity to degrade the long-chain AHLs (Fig. 6). This could suggest that biodegradation of AHLs takes place in N. multiformis. Although the findings are not directly able to prove AHL production in the N. multiformis strain, we have demonstrated that the absence of signal molecules in this ammonia-oxidizing strain might be attributed to possible AHL degradation.

FIG 6.

Identification of degradation of the long-chain AHLs by N. multiformis. The N. multiformis strain and medium solution were incubated with 10 μM long-chain AHLs (C14-AHL and 3-oxo-C14-AHL) for 0 h, 4 h, or 8 h, after which the culture supernatants were spotted onto an agar plate (containing X-Gal). The residual AHLs were detected by A. tumefaciens A136 (blue stain).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we showed a functional quorum sensing signal synthase in the AOB species N. multiformis. An N. multiformis gene termed nmuI, when introduced into E. coli, resulted in the synthesis of long-chain AHLs detected by a reporter strain, and LC-MS results demonstrated that these AHLs were enriched in molecules of C14 and 3-oxo-C14. None of the two AHLs made by nmuI from N. multiformis have yet been identified in other AOB strains. Burton et al. (11) first documented the production of multiple AHLs (C6-, C8-, and C10-AHL) by Nitrosomonas europaea, but the homoserine lactone synthase-encoding gene of N. europaea is still unconfirmed. To the best of our knowledge, relevant studies regarding a functional quorum sensing system in AOB have not been published before, but our results have identified the biosynthetic activity of an AHL synthase in N. multiformis, as well as the relevant types of signal molecules.

We found a LuxR homolog (NmuR) which exhibited 39% similarity to LasR, an AHL response regulator from P. aeruginosa, but it was unusual in N. multiformis that the regulatory gene nmuR did not seem to be in tandem with nmuI (31,809 bp apart) (6). In P. aeruginosa, lasR and lasI are relatively close together, and the transcriptional regulator LasR and the cognate autoinducer 3-oxo-C12-HSL constitute the las system to control virulence gene expression and biofilm development (28). As a test of the hypothesis that C14-AHL and 3-oxo-C14-AHL are cognate signals of NmuR in N. multiformis, we examined the solubility of the R protein. As expected, a portion of NmuR protein was detected in the soluble fraction from cells grown with C14-AHL and 3-oxo-C14-AHL; however, there was more soluble protein when the protein was expressed in medium containing C12-AHL and 3-oxo-C12-AHL. LuxR and its homologs are thought to be composed of an N-terminal domain binding with the AHL signals and a C-terminal target promoter binding domain (29). LuxR family proteins are known to be mostly insoluble when overexpressed, while in the presence of their cognate AHLs, they become soluble and more stable (30). In this study, when the R protein was overexpressed in E. coli, it seemed that C12-AHL and 3-oxo-C12-AHL were bound with a higher affinity in the solubility assay. As both long-chain AHLs formed a complex with the N-terminal domain of NmuR, one can assume that there is at least one complete QS circuit encoded in N. multiformis.

A previous study reported that the luxI homolog of Rhodobacter capsulatus, which is responsible for long-chain AHL synthesis, synthesized a different range of AHLs in E. coli instead of the native AHL signals (21). It is thus possible that the QS component in E. coli might exert an influence on the predominant AHL signals produced by NmuI.

Duerkop et al. (17) also reported that synthesis of the soluble LuxR homolog protein of Burkholderia mallei in recombinant E. coli required C10-AHL, which was not the AHL synthase-generated signal. Moreover, there was less soluble R protein when cells were grown in the presence of C10-AHL than with the cognate signal C8-AHL. In our study, it was also reasonable to deduce that the AOB strain might use C12-AHL and 3-oxo-C12-AHL as supplements or substitutes for C14-AHL and 3-oxo-C14-AHL. However, solubility testing of the R protein showed that C12-AHL and 3-oxo-C12-AHL served more effectively than NmuI-generated signals, which suggested that other LuxR homologs responsive to C14-AHL and 3-oxo-C14-AHL might exist in N. multiformis.

It seemed that the findings of different effects of NmuR solubility with diverse AHLs could be clarified through the signals produced by N. multiformis. However, no AHLs were detected in the culture supernatants of N. multiformis. According to the results of RT-PCR, the nmuI gene was transcribed in N. multiformis, and the degradation experiment demonstrated that the absence of AHL signals might be attributed to the possible AHL-inactivating activities of this strain. It could be supposed that the AHL-degrading activity of N. multiformis might help this autotrophic ammonia oxidizer to survive when faced with a potential competing organism in natural ecosystems. On the other hand, some AOB strains can utilize fructose and other compounds as carbon sources to support growth (31, 32). These data suggest that in N. multiformis, AHLs might provide benefits for cells as the carbon and nitrogen source in several metabolic pathways. In studies of QS in N. europaea, it has been considered that the low levels of AHL produced by AOB strains might be related to metabolic patterns of chemoautotrophic bacteria (11). The coexistence of QS with AHL-degrading activities indicates a complicated signaling system in N. multiformis.

The study of Batchelor et al. (12) demonstrated that N. europaea cells were more capable of maintaining ammonia-oxidizing potential in biofilms than in suspension cultures after nutrient starvation. The results showed that there was a response by N. europaea to the quorum sensing signal molecule 3-oxo-C6-AHL, and the rapid recovery of starved biofilm populations may have been due to AHL production and accumulation. Recently, De Clippeleir et al. (13) reported that long-chain acyl homoserine lactones were detected in an oxygen-limited autotrophic nitrification/denitrification (OLAND) biofilm, and addition of N-dodecanoyl homoserine lactone (C12-AHL) could increase the anaerobic ammonium oxidation (anammox) rate at low biomass concentrations. It seems likely that ammonia-oxidizing activity is related to bacterial communication signals; nevertheless, the metabolic mechanism of ammonia oxidation mediated and affected by quorum sensing in AOB is still unknown. Further study of the AHL synthases in N. multiformis is the key to understanding the QS signal biosynthetic pathways in a chemolithotrophic microorganism and offers the possibility of exploring whether QS effects are significant in controlling AOB behavior. Further studies are needed to confirm the quorum sensing regulon and genes regulated by QS to complete the knowledge of the regulatory networks in N. multiformis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grants 41371266, 21377157, and 21177145), the Strategic Priority Research Program of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Major Science and Technology Program for Water Pollution Control and Treatment of China (grant 2012ZX07209-003), and the National Key Technology R&D Program of China (grant 2013BAD11B03-3).

We thank R. McLean (Department of Biology, Texas State University) for kindly providing the AHL reporter strains.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 22 November 2013

REFERENCES

- 1.Miller MB, Bassler BL. 2001. Quorum sensing in bacteria. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 55:165–199. 10.1146/annurev.micro.55.1.165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fuqua C, Parsek MR, Greenberg EP. 2001. Regulation of gene expression by cell-to-cell communication: acyl-homoserine lactone quorum sensing. Annu. Rev. Genet. 35:439–468. 10.1146/annurev.genet.35.102401.090913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Williams P. 2007. Quorum sensing, communication and cross-kingdom signalling in the bacterial world. Microbiology 153:3923–3938. 10.1099/mic.0.2007/012856-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhuang X, Gao J, Ma A, Fu S, Zhuang G. 2013. Bioactive molecules in soil ecosystems: masters of the underground. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 14:8841–8868. 10.3390/ijms14058841 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hao Y, Winans SC, Glick BR, Charles TC. 2010. Identification and characterization of new LuxR/LuxI-type quorum sensing systems from metagenomic libraries. Environ. Microbiol. 12:105–117. 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2009.02049.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Norton JM, Klotz MG, Stein LY, Arp DJ, Bottomley PJ, Chain PS, Hauser LJ, Land ML, Larimer FW, Shin MW. 2008. Complete genome sequence of Nitrosospira multiformis, an ammonia-oxidizing bacterium from the soil environment. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74:3559–3572. 10.1128/AEM.02722-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Okabe S, Kindaichi T, Ito T, Satoh H. 2004. Analysis of size distribution and areal cell density of ammonia-oxidizing bacterial microcolonies in relation to substrate microprofiles in biofilms. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 85:86–95. 10.1002/bit.10864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Briones AM, Jr, Okabe S, Umemiya Y, Ramsing N-B, Reichardt W, Okuyama H. 2003. Ammonia-oxidizing bacteria on root biofilms and their possible contribution to N use efficiency of different rice cultivars. Plant Soil 250:335–348. 10.1023/A:1022897621223 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gómez-Villalba B, Calvo C, Vilchez R, González-López J, Rodelas B. 2006. TGGE analysis of the diversity of ammonia-oxidizing and denitrifying bacteria in submerged filter biofilms for the treatment of urban wastewater. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 72:393–400. 10.1007/s00253-005-0272-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davies DG, Parsek MR, Pearson JP, Iglewski BH, Costerton J, Greenberg E. 1998. The involvement of cell-to-cell signals in the development of a bacterial biofilm. Science 280:295–298. 10.1126/science.280.5361.295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burton E, Read H, Pellitteri M, Hickey W. 2005. Identification of acyl-homoserine lactone signal molecules produced by Nitrosomonas europaea strain Schmidt. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:4906–4909. 10.1128/AEM.71.8.4906-4909.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Batchelor S, Cooper M, Chhabra S, Glover L, Stewart G, Williams P, Prosser J. 1997. Cell density-regulated recovery of starved biofilm populations of ammonia-oxidizing bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:2281–2286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.De Clippeleir H, Defoirdt T, Vanhaecke L, Vlaeminck SE, Carballa M, Verstraete W, Boon N. 2011. Long-chain acylhomoserine lactones increase the anoxic ammonium oxidation rate in an OLAND biofilm. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 90:1511–1519. 10.1007/s00253-011-3177-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Norton JM, Alzerreca JJ, Suwa Y, Klotz MG. 2002. Diversity of ammonia monooxygenase operon in autotrophic ammonia-oxidizing bacteria. Arch. Microbiol. 177:139–149. 10.1007/s00203-001-0369-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McLean RJ, Whiteley M, Stickler DJ, Fuqua WC. 1997. Evidence of autoinducer activity in naturally occurring biofilms. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 154:259–263. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1997.tb12653.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morin D, Grasland B, Vallée-Réhel K, Dufau C, Haras D. 2003. On-line high-performance liquid chromatography-mass spectrometric detection and quantification of N-acylhomoserine lactones, quorum sensing signal molecules, in the presence of biological matrices. J. Chromatogr. A 1002:79–92. 10.1016/S0021-9673(03)00730-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Duerkop BA, Ulrich RL, Greenberg EP. 2007. Octanoyl-homoserine lactone is the cognate signal for Burkholderia mallei BmaR1-BmaI1 quorum sensing. J. Bacteriol. 189:5034–5040. 10.1128/JB.00317-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nasser W, Reverchon S. 2007. New insights into the regulatory mechanisms of the LuxR family of quorum sensing regulators. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 387:381–390. 10.1007/s00216-006-0702-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.De Kievit TR, Gillis R, Marx S, Brown C, Iglewski BH. 2001. Quorum-sensing genes in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms: their role and expression patterns. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:1865–1873. 10.1128/AEM.67.4.1865-1873.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Watson WT, Minogue TD, Val DL, von Bodman SB, Churchill ME. 2002. Structural basis and specificity of acyl-homoserine lactone signal production in bacterial quorum sensing. Mol. Cell 9:685–694. 10.1016/S1097-2765(02)00480-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schaefer AL, Taylor TA, Beatty JT, Greenberg E. 2002. Long-chain acyl-homoserine lactone quorum-sensing regulation of Rhodobacter capsulatus gene transfer agent production. J. Bacteriol. 184:6515–6521. 10.1128/JB.184.23.6515-6521.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Arnold K, Bordoli L, Kopp J, Schwede T. 2006. The SWISS-MODEL workspace: a web-based environment for protein structure homology modelling. Bioinformatics 22:195–201. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guex N, Peitsch MC. 1997. SWISS-MODEL and the Swiss-Pdb Viewer: an environment for comparative protein modeling. Electrophoresis 18:2714–2723. 10.1002/elps.1150181505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schwede T, Kopp J, Guex N, Peitsch MC. 2003. SWISS-MODEL: an automated protein homology-modeling server. Nucleic Acids Res. 31:3381–3385. 10.1093/nar/gkg520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Farah C, Vera M, Morin D, Haras D, Jerez CA, Guiliani N. 2005. Evidence for a functional quorum-sensing type AI-1 system in the extremophilic bacterium Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:7033–7040. 10.1128/AEM.71.11.7033-7040.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.González JF, Venturi V. 2013. A novel widespread interkingdom signaling circuit. Trends Plant Sci. 18:167–174. 10.1016/j.tplants.2012.09.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Qin Y, Luo Z-Q, Smyth AJ, Gao P, von Bodman SB, Farrand SK. 2000. Quorum-sensing signal binding results in dimerization of TraR and its release from membranes into the cytoplasm. EMBO J. 19:5212–5221. 10.1093/emboj/19.19.5212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Duan K, Surette MG. 2007. Environmental regulation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 Las and Rhl quorum-sensing systems. J. Bacteriol. 189:4827–4836. 10.1128/JB.00043-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hanzelka BL, Greenberg E. 1995. Evidence that the N-terminal region of the Vibrio fischeri LuxR protein constitutes an autoinducer-binding domain. J. Bacteriol. 177:815–817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pinto UM, Winans SC. 2009. Dimerization of the quorum-sensing transcription factor TraR enhances resistance to cytoplasmic proteolysis. Mol. Microbiol. 73:32–42. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06730.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hommes NG, Sayavedra-Soto LA, Arp DJ. 2003. Chemolithoorganotrophic growth of Nitrosomonas europaea on fructose. J. Bacteriol. 185:6809–6814. 10.1128/JB.185.23.6809-6814.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Racz L, Datta T, Goel R. 2010. Effect of organic carbon on ammonia oxidizing bacteria in a mixed culture. Bioresour. Technol. 101:6454–6460. 10.1016/j.biortech.2010.03.058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]