Abstract

Dehalococcoides mccartyi strains KS and RC grow with 1,2-dichloropropane (1,2-D) as an electron acceptor in enrichment cultures derived from hydrocarbon-contaminated and pristine river sediments, respectively. Transcription, expression, enzymatic, and PCR analyses implicated the reductive dehalogenase gene dcpA in 1,2-D dichloroelimination to propene and inorganic chloride. Quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) analyses demonstrated a D. mccartyi cell increase during growth with 1,2-D and suggested that both D. mccartyi strains carried a single dcpA gene copy per genome. D. mccartyi strain RC and strain KS produced 1.8 × 107 ± 0.1 × 107 and 1.4 × 107 ± 0.5 × 107 cells per μmol of propene formed, respectively. The dcpA gene was identified in 1,2-D-to-propene-dechlorinating microcosms established with sediment samples collected from different geographical locations in Europe and North and South America. Clone library analysis revealed two distinct dcpA phylogenetic clusters, both of which were captured by the dcpA gene-targeted qPCR assay, suggesting that the qPCR assay is useful for site assessment and bioremediation monitoring at 1,2-D-contaminated sites.

INTRODUCTION

1,2-Dichloropropane (1,2-D) has been used in a variety of applications, including as an industrial solvent, a lead scavenger in gasoline, and a fumigant to prevent root nematode damage to high-value crops (1). In addition, 1,2-D is a precursor in the production of other chlorinated solvents and is produced as a by-product in the manufacture of propylene oxide and epichlorohydrine (2). 1,2-D is toxic and is a suspected carcinogen, and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) regulates its maximum concentration level (MCL) in drinking water to 5 μg/liter (http://water.epa.gov/drink/contaminants/index.cfm#List). Today, 1,2-D is no longer used as a solvent and in soil fumigant applications; however, the 2010 EPA's Toxics Release Inventory reported that 1,2-D in excess of 90,000 pounds was disposed of or released in the United States (http://iaspub.epa.gov/triexplorer/tri_release.chemical). A 2006 study conducted by the National Water-Quality Assessment Program (NAWQA) and led by the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) detected 1,2-D in 1.0% of aquifer samples from throughout the United States (at an assessment level of 0.02 μg/liter). In 18 of 723 (2.5%) shallow groundwater samples adjacent to agricultural areas, 1,2-D was present at concentrations exceeding 0.02 μg/liter. In some aquifer samples and domestic wells, 1,2-D was reported at levels above the 5-μg/liter MCL (3). The NAWQA aquifer study detected fumigants in 10 to 30% of the aquifers sampled in areas where fumigant applications were common, such as Oahu, HI, and the Central Valley of California (3). Hawaii used more than 1.8 million pounds of fumigants in the 1970s to protect pineapple crops from root-parasitic nematodes (4). Today, 1,2-D use is controlled and new contamination minimized; however, 1,2-D has emerged as a pervasive groundwater contaminant and threatens environmental health and drinking water quality.

1,2-D is recalcitrant under oxic conditions, but a few strictly anaerobic bacteria have been implicated in 1,2-D reductive dechlorination to nontoxic propene. These microorganisms use 1,2-D as a terminal electron acceptor for organohalide respiration. Microbes involved in this process include a Dehalobacter sp. identified in a mixed culture derived from river sediment (5); the bacterial isolate Desulfitobacterium dichloroeliminans strain DCA1, obtained from an industrial site impacted with 1,2-dichloroethane (1,2-DCA) (6); Dehalogenimonas lykanthroporepellens strains BL-DC-8 and BL-DC-9 and Dehalogenimonas alkenigignens strain IP3-3, isolated from groundwater collected at a Superfund site (7, 8); and Dehalococcoides mccartyi strains RC and KS, derived from pristine and contaminated river sediments, respectively (9, 10). D. mccartyi strains RC and KS share up to 99.8% 16S rRNA gene sequence identity with D. mccartyi strains of the Pinellas group, which cannot grow with 1,2-D (10). The incongruence between the 16S rRNA gene sequence and reductive dechlorination activity demonstrates the need for identifying 1,2-D dechlorination-specific biomarkers.

Reductive dechlorination reactions are catalyzed by reductive dehalogenases (RDases). D. mccartyi genomes contain multiple RDase genes (e.g., 11 in strain BAV1 and 36 in strain VS) (11). Few D. mccartyi RDases have assigned functions, and all of them share common characteristics, such as a Tat signal peptide close to the N terminus, two iron-sulfur clusters close to the C terminus, and an adjacent B gene. To date, only a few RDases have been characterized biochemically and implicated in specific dechlorination reactions, and an RDase responsible for 1,2-D-to-propene dechlorination has not been identified. In this study, RDase transcript, cDNA clone library, and expression analyses implicated DcpA in 1,2-D reductive dechlorination to propene. A dcpA-targeted quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) approach correlated the presence of dcpA with 1,2-D reductive dechlorination activity, indicating that dcpA serves as a biomarker for 1,2-D reductive dechlorination.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

1,2-D-dechlorinating cultures.

The 1,2-D-dechlorinating mixed cultures RC and KS were derived from the Red Cedar River, near Okemos, MI, and the King Salmon River, AK, respectively. The Red Cedar River has no known anthropogenic sources of chlorinated solvents but is located in an agricultural area. The King Salmon River sediment had reported hydrocarbon contamination. Both cultures are nonmethanogenic and have been maintained for more than 15 years in reduced mineral salts medium (10). D. lykanthroporepellens strain BL-DC-9 was kindly provided by William M. Moe and maintained as described previously (7, 12).

Microcosms and enrichment cultures.

Details on sample collection and site information are provided in the supplemental material and given in Table 1. Microcosms were prepared inside an anoxic chamber (N2/H2, 97%/3% [vol/vol]) by using established procedures (13), with the following modifications. One-gram (wet weight) samples of solids were transferred to sterile 60-ml (nominal capacity) glass serum bottles containing 40 ml of defined, completely synthetic reduced mineral salts basal salts medium (14) amended with 5 mM lactate, 30 mM bicarbonate (pH 7.2), 0.2 mM Na2S · 9H2O, resazurin (0.25 mg liter−1), vitamins (15), and 0.2 mM 1,2-D. Microcosms established with groundwater were initiated with 20 ml of groundwater plus 20 ml of medium. All microcosms were prepared in duplicate and incubated statically in the dark at room temperature. After all of the 1,2-D was dechlorinated to propene, 3% (vol/vol) inocula were transferred to glass vessels containing fresh medium. After four consecutive transfers, all solids had been removed. Propene and 1,2-D concentrations were monitored by manually injecting 0.1-ml headspace samples into an HP 7890 gas chromatograph (GC) equipped with a DB-624 column (60 m long by 0.32 mm in diameter; film thickness of 1.8 μm [nominal]) and a flame ionization detector (FID) as described previously (16). To verify propene formation, additional GC measurements were made with an Agilent HP-PLOT/Q column (30 m long by 0.53 mm in diameter; 40 μm of film thickness), which resolves propene from other C1 to C3 alkanes and alkenes.

TABLE 1.

Site materials used for microcosm setup to evaluate 1,2-D reductive dechlorination activity and analyzed for the presence of the D. mccartyi and D. lykanthroporepellens 16S rRNA genes and the dcpA genee

| Sample designation | Sample location | Sample type | Major reported contaminants | Date of collection | Dechlorination end products | Presence of indicated gene |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D. mccartyi 16S rRNA gene | D. lykanthroporepellens 16S rRNA gene | dcpA | ||||||

| Microcosms | ||||||||

| Third Creek, TRS1 | Third Creek, Knoxville, TN | Sediment | PCE, TCE, 1,1,1-TCA | February 2011 | Propene | + | + | + |

| Third Creek, TRS2 | Third Creek, Knoxville, TN | Sediment | PCE, TCE, 1,1,1-TCA | February 2011 | Propene | + | + | + |

| Third Creek, TRS3 | Third Creek, Knoxville, TN | Sediment | PCE, TCE, 1,1,1-TCA | March 2011 | Propene | + | + | + |

| Neckar River | Stuttgart, Germany | Sediment | None | May 2011 | Propene | + | + | + |

| Trester | Stuttgart, Germany | Solidsa | None | May 2011 | Propene | + | + | + |

| 001-ST-SO, 2.7–2.9 m | Barra Mansa, Brazil | Sediment | Chloroform, CCl4 | August 2010 | −b | + | ND | + |

| 002-ST-SO, 5.7–5.8 m | Barra Mansa, Brazil | Sediment | Chloroform, CCl4 | August 2010 | −b | + | ND | + |

| Way-MW13D-12J811 | Waynesboro, GA | Groundwater | 1,2-D and 1,2-DCA | August 2010 | − | ND | ND | ND |

| FP1-MW46, 22–26 m | Ft. Pierce, FL | Sediment | Nonec | August 2010 | − | ND | ND | ND |

| FP2-MW49, 26–27 m | Ft. Pierce, FL | Sediment | Nonec | August 2010 | − | + | + | ND |

| FP3-MW49, 46–47 m | Ft. Pierce, FL | Sediment | Nonec | August 2010 | − | + | + | ND |

| FP4-MW47, 47–48 m | Ft. Pierce, FL | Sediment | Nonec | August 2010 | − | + | ND | ND |

| FP5-MW49, 95–98 m | Ft. Pierce, FL | Sediment | Nonec | August 2010 | − | ND | ND | ND |

| FP-MW33, 13–14 m | Ft. Pierce, FL | Groundwater | 18,000 μg/liter of 1,2-D | June 2012 | Propene | + | + | + |

| FP-MW26, 14–15 m | Ft. Pierce, FL | Groundwater | 17,000 μg/liter of 1,2-D | June 2012 | Propene | + | + | + |

| FP-MW20, 20–21 m | Ft. Pierce, FL | Groundwater | 810 μg/liter of 1,2-D | June 2012 | Propene | + | + | + |

| DNA samples | ||||||||

| FP-MW-2S, 6–7 m | Ft. Pierce, FL | DNA/Biobead | 14,000 μg/liter of 1,2-D | July 2011 | No propened | + | ND | ND |

| FP-MW-20, 20–21 m | Ft. Pierce, FL | DNA/Biobead | 810 μg/liter of 1,2-D | February 2011 | Propened | ND | ND | + |

| FP-MW-26, 14–15 m | Ft. Pierce, FL | DNA/Biobead | 17,000 μg/liter of 1,2-D | March 2011 | Propened | + | + | + |

| FP-MW-61, 20–21 m | Ft. Pierce, FL | DNA/Biobead | 140 μg/liter of 1,2-D | May 2011 | Propened | ND | + | + |

| FW-024 | IFC site, Oak Ridge, TN | DNA/GW | Multiple | February 2004 | NT | + | ND | ND |

| FW-103 | IFC site, Oak Ridge, TN | DNA/GW | Multiple | February 2004 | NT | + | + | + |

| FW-100-2 | IFC site, Oak Ridge, TN | DNA/GW | Multiple | August 2005 | NT | + | ND | + |

| FW-100-3 | IFC site, Oak Ridge, TN | DNA/GW | Multiple | February 2004 | NT | + | ND | + |

Solid residues (trester) from wine making, consisting mostly of grape skins.

Small amounts of 1-chloropropane (1-CP) or 2-chloropropane (2-CP) were detected in live microcosms but also in negative controls.

Ft. Pierce is contaminated with 1,2-D (up to 24,000 μg/liter), but the sediments tested here were from wells outside the plume area.

Dechlorination not tested on microcosm; data provided reflect field-site conditions. There was no propene detected in FP1-MW-2S.

PCE, tetrachloroethene; TCE, trichloroethene; 1,1,1-TCA, 1,1,1-trichloroethene; 1,2-DCA, 1,2-dichloroethane; NT, not tested; ND, not detected; −, no dechlorination in microcosm after 90 days of incubation.

DNA isolation.

A DNeasy Blood and Tissue kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) was used to extract DNA from sediment-free cultures, with modifications to improve cell lysis (10). DNAs from solid and groundwater samples were extracted using a Mo Bio Power Soil DNA kit (Mo Bio Laboratories Inc., Carlsbad, CA) and a PowerWater DNA isolation kit (Mo Bio Laboratories Inc.), respectively, following the manufacturer's recommendations.

RNA isolation and preparation of cDNA libraries.

Biomass was collected from 10 to 20 ml of RC and KS culture suspensions when 50 to 75% of the initial 1,2-D dose had been converted to propene. Cells were harvested by vacuum filtration onto a Durapore hydrophilic polyvinylidene fluoride membrane (25-mm diameter and 0.22-μm pore size) (Millipore, Billerica, MA). RNA extraction, DNase treatment, and cDNA synthesis and purification were performed as described previously (17). cDNA libraries were established with degenerate primers B1R and RR2F, targeting D. mccartyi RDase genes (18). Primer walking procedures extended the partial dcpA and dcpB genes (see the supplemental material for details).

qPCR.

D. mccartyi and D. lykanthroporepellens 16S rRNA gene-targeted PCR assays followed established protocols (see Table 2 for primer information and references). IDT DNA Primer Quest software (http://scitools.idtdna.com/Primerquest/) was used to design qPCR primers dcpA-1257F and dcpA-1449R and TaqMan probe dcpA-1426 to enumerate dcpA gene copies (Table 2). First, the primers were used with SYBR green chemistry to recognize nonspecific amplification and/or primer dimer formation (19). Standard curves were generated with 10-fold serial dilutions (108 to 100 copies) of the partial D. mccartyi strain KS dcpAB gene fragment cloned into the TOPO TA (Invitrogen) pCRII plasmid. To confirm target specificity, melting curves were obtained with genomic template DNAs from D. mccartyi strains RC and KS and D. lykanthroporepellens strain BL-DC-9. Additionally, the qPCR amplicons were resolved in 1% agarose gels run at 120 V for 30 min to assess amplicon sizes for target-specific amplification. Reaction mixtures with sterile water (no-template DNA) and with genomic DNA from D. mccartyi strain GT, which does not possess the dcpA gene, served as negative controls. After validation and optimization in SYBR green qPCR, the primers were used with the TaqMan probe dcpA-1426 in assays as described previously (20). All assays exhibited amplification efficiencies of 100% ± 10% (i.e., with a slope between −3.6 and −3.1), consistency across replicate reactions, and linear standard curves (R2 > 0.980) (21, 22). A quantification limit of 30 copies per reaction was determined based on fluorescence signals above the cycle threshold value of 0.2 within the first 38 PCR cycles measured in 20 replicate assays (21, 22). The lowest value of the standard curve (3 copies per reaction) was the detection limit, and all nontemplate control assays fell below this value. The qPCR assay conditions for the reactions targeting the D. mccartyi 16S rRNA gene have been published (20). All known D. mccartyi genomes possess one 16S rRNA gene copy, and the enumeration of this gene is used to determine the D. mccartyi cell number (20). The number of dcpA genes per D. mccartyi genome was calculated by dividing the number of dcpA gene copies detected per ml of culture by the total number of D. mccartyi 16S rRNA genes detected in the same culture volume.

TABLE 2.

Primers and probes used in this study

| Primer or probe | Primer sequence (5′–3′) | Target | Purpose | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RRF2 | SHMGBMGWGATTTYATGAARRa | RDase A RRDFMK motif | Amplification of RDase-like genes | 18 |

| B1R | CHADHAGCCAYTCRTACCAa | RDase B WYEW motif | Amplification of RDase-like genes | 18 |

| dcpA-1257Fb | CGATGTGCCAGCCATTGTGTCTTT | dcpA gene | dcpA gene quantification and primer walking | This study |

| dcpA-1449Rb | TTTAAACAGCGGGCAGGTACTGGT | dcpA gene | dcpA gene quantification, direct and nested PCR with dcpA-360F | This study |

| dcpA-1426b | FAM-ACGTCATCTCAGATGAAGGCAGAGCT-BHQc | dcpA gene | dcpA gene quantification, direct and nested PCR | This study |

| dcpA-360Fb | TTGCGTGATCAAATTGGAGCCTGG | dcpA qPCR | dcpA gene quantification, direct and nested PCR with primer dcpA-1449R, primer walking | This study |

| Dhc-1200F | CTGGAGCTAATCCCCAAAGCT | D. mccartyi 16S rRNA gene | D. mccartyi 16S rRNA gene quantification | 20 |

| Dhc-1271R | CAACTTCATGCAGGCGGG | D. mccartyi 16S rRNA gene | D. mccartyi 16S rRNA gene quantification | 20 |

| Dhc-1240Probe | FAM-TCCTCAGTTCGGATTGCAGGCTGAA-TAMRAc | D. mccartyi 16S rRNA gene | D. mccartyi 16S rRNA gene quantification | 20 |

| LuciF | TACAACACCCCAACATCTTCGA | Luciferase reference mRNA | Quantitation of internal standard | 23 |

| LuciR | GGAAGTTCACCGGCGTCAT | Luciferase reference mRNA | Quantitation of internal standard | 23 |

| Luci-probe | JOE-CGGGCGTGGCAGGTCTTCCC-BHQ | Luciferase reference mRNA | Quantitation of internal standard | 23 |

| rpoB-1648F | ATTATCGCTCAGGCCAATACCCGT | D. mccartyi rpoB gene | D. mccartyi rpoB gene quantification | 24 |

| rpoB-1800R | TGCTCAAGGAAGGGTATGAGCGAA | D. mccartyi rpoB gene | D. mccartyi rpoB gene quantification | 24 |

| Dhc-730F | GCGGTTTTCTAGGTTGTC | D. mccartyi 16S rRNA gene | D. mccartyi detection by PCR | 60 |

| Dhc-1350R | CACCTTGCTGATATGCGG | D. mccartyi 16S rRNA gene | D. mccartyi detection by PCR | 60 |

| BL-DC-631F | GGTCATCTGATACTGTTGGACTTGAGTATG | D. lykanthroporepellens 16S rRNA gene | D. lykanthroporepellens detection by PCR | 61 |

| BL-DC-796R | ACCCAGTGTTTAGGGCGTGGACTACCAGG | D. lykanthroporepellens 16S rRNA gene | D. lykanthroporepellens detection by PCR | 61 |

| dcp_up120Fb | GCTCCTGGCAGAGCCGTCAGT | 120 bp upstream of dcpA | Amplification and assembly of dcpA gene start | This study |

Abbreviations for degenerate nucleotide positions are as follows: R = A or G; K = G or T; M = A or C; S = C or G; W = A or T; Y = C or T; B = C, G, or T; D = A, G, or T; V = A, C, or G; and H = A, C, or T.

Primer names are given based on the target position relative to the dcpA start coordinates in the Dehalogenimonas lykanthroporepellens BL-DC-9 sequenced genome.

FAM, 6-carboxyfluorescein; TAMRA, 6-carboxytetramethylrhodamine.

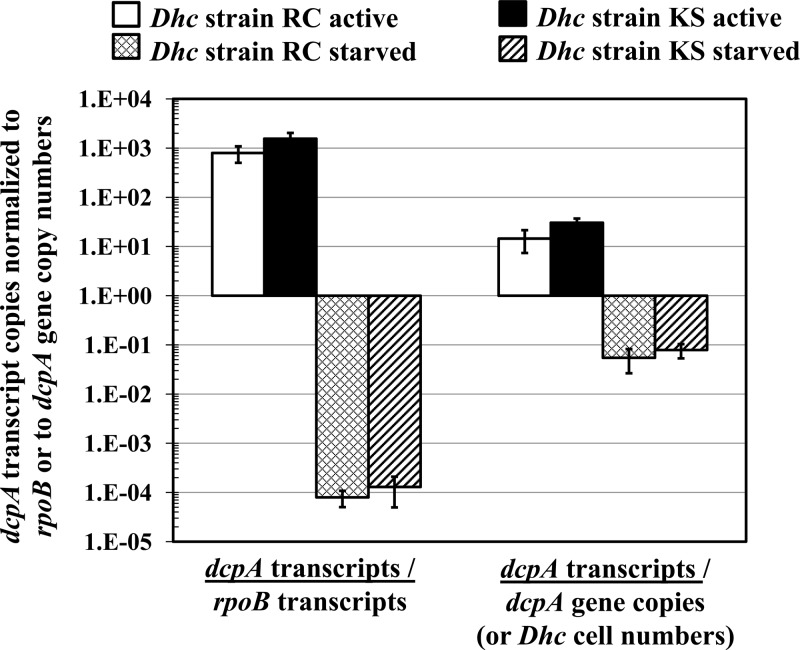

For transcriptional analysis, cDNAs generated from active 1,2-D-dechlorinating cultures served as templates. All qPCR data were corrected for the loss (i.e., % recovery) of luciferase transcripts, which were used as an internal standard (23), and rpoB transcripts were quantified as a measure of general metabolic activity, as described previously (24). The rpoB housekeeping gene is conserved in D. mccartyi genomes, and rpoB transcripts were quantified as a measure of general metabolic activity and for normalization (24–26). When applicable, dcpA transcript abundances were normalized to rpoB or dcpA gene copy numbers. Starved cultures (i.e., cultures that had consumed all 1,2-D for at least 1 month) served as baseline controls for the transcriptional studies. All samples were analyzed in triplicate at two dilutions (1:10 and 1:100), using an ABI 7500 fast quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) instrument (Applied Biosystems), and the reported values represent the averages for at least three biological replicate cultures (i.e., six pseudoreplicates per sample, or 18 data sets for the three biological replicates).

Cloning of dcpA sequences from environmental samples and phylogenetic analysis.

Primers dcpA-360F and dcpA-1449R were designed for standard PCRs to detect, clone, and sequence dcpA genes from samples of interest (Table 2). These primers were designed based on alignments of the dcpA sequences retrieved from the cDNA libraries of D. mccartyi strains RC and KS and the dcpA gene (Dehly_1524) of D. lykanthroporepellens strain BL-DC-9. dcpA clone libraries were established using DNAs isolated from the original sediment and groundwater samples listed in Table 1. Environmental DNA samples were subjected to nested PCR, with the initial PCR amplification mixture containing 2 μl of undiluted or 1:10-diluted template DNA and the degenerate primers B1R and RRF2, as described previously (18). Subsequently, a second (nested) round of PCR with the dcpA-specific primers dcpA-360F and dcpA-1449R was performed using 2 μl of the DNA solution obtained from the first round of amplification (Fig. 1 shows approximate binding sites for primers RRF2 and B1R as well as the dcpA-specific primers). The expected amplicon size generated in nested PCR was 1,089 bp. The dcpA-specific PCR mixtures consisted of (final concentrations) 1× PCR buffer, 2.5 mM MgCl2, a 250 μM concentration of each deoxynucleoside triphosphate (ABI), 250 nM (each) primers, and 2.5 U of AmpliTaq polymerase (ABI). The following temperature program was used to amplify the dcpA gene: 94°C for 2 min 10 s (1 cycle); 94°C for 30 s, 56.0°C for 45 s, and 72°C for 2 min 10 s (30 cycles); and 72°C for 6 min. The dcpA amplicons were cloned into the pCRII TOPO vector and transformed into Escherichia coli TOP10 competent cells (TOPO TA cloning kit; Invitrogen) following the manufacturer's recommendations. A QIAprep Spin miniprep kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) was used for plasmid isolation, the inserts were sequenced using primers M13F and M13R (http://tools.lifetechnologies.com/content/sfs/manuals/topotaseq_man.pdf), and the DNA nucleotide sequences were translated (http://web.expasy.org/translate/) and aligned using ClustalW (27) in MEGA, version 5 (28). Phylogenetic relationships were calculated from a total of 53 amino acid (aa) sequences by using the neighbor-joining tree method (29), and evolutionary distances were computed using a method based on the number of differences (30). Branch support values were estimated with a bootstrap test (1,000 replicates) (31). The 53 translated nucleotide sequences used in the phylogenetic tree comprised 48 partial dcpA sequences (∼1 kb long) obtained from environmental samples, the complete dcpA sequences of D. lykanthroporepellens strain BL-DC-9 RC and D. mccartyi strain RC and strain KS, the translated nucleotide sequence of the pseudogene DET0162, and the sequence of DET1538, encoding a putative RDase with unknown function (both identified in the genome of D. mccartyi strain 195 [32]). DET1538 served as the outgroup for phylogenetic analyses.

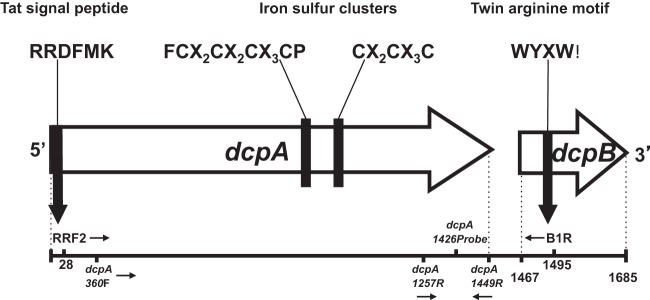

FIG 1.

Arrangements of the dcpA gene and its corresponding dcpB gene in D. mccartyi strains RC and KS. Approximate binding sites for the degenerate primers RRF2 and B1R as well as the dcpA-specific primers designed in this study are indicated. Also shown are the characteristic dehalogenase features encoded by the dcpA gene, which include the conserved Tat signal peptide RRXFXK at the N terminus and two iron-sulfur clusters closer to the C terminus, in the form of FCXXCXXCXXXCP (or FCX2CX2CX3CP) and CXXCXXXC (or CX2CX3C). dcpB is located downstream of dcpA and encodes a small, highly hydrophobic protein with the conserved twin-arginine motif in the form WYXW. The dcpA and dcpB genes (Dehly_1524 and Dehly_1523) in D. lykanthroporepellens strain BL-DC-9 also encode a dehalogenase with these common features.

Protein assays and BN-PAGE.

D. lykanthroporepellens strain BL-DC-9 was used for in vitro enzyme assays, blue native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (BN-PAGE), and proteomic workflows because strain BL-DC-9 is a pure culture and its genome sequence is available. Strain BL-DC-9 harboring the dcpA gene was grown with 0.5 mM 1,2-D. Cells were harvested by centrifugation (10,000 × g for 20 min at 4°C) and lysed by bead beating (33). The crude extracts were subjected to BN-PAGE to detect reductive dechlorination activity in gel slices following electrophoretic separation. Activity assays with individual gel slices were performed as described previously (33), with minor modifications (see the supplemental material). In the activity assays, the positive controls consisted of 1 ml of pelleted cell culture suspended in assay buffer, while negative-control vials did not receive protein.

2D LC-MS/MS.

BN-PAGE enzyme assays were combined with proteomic workflows to identify RDase peptides present in the gel slices showing 1,2-D dechlorination activity. Identified peptide sequences were matched to the closed genome sequence of D. lykanthroporepellens strain BL-DC-9 (NC_014314.1) by using MyriMatch (34) along with IDPicker software (35) to translate spectra into peptide sequences. Detailed information on sample preparation for two-dimensional liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (2D LC-MS/MS) analysis and database parameters are available in the supplemental material.

Computational analyses.

The DcpA sequences were analyzed for secretory signal peptides by using the TatP (www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/TatP) and SignalP (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/SignalP/) programs. The Compute pI/MW program (http://us.expasy.org/tools/pi_tool.html) was used to predict the molecular weight and isoelectric point of DcpA. The DcpB sequences were analyzed with TMMOD (http://liao.cis.udel.edu/website/servers/TMMOD/scripts/frame.php?p=submit) to predict protein topology based on transmembrane motifs. The presence of corrinoid and ribosome binding sites and a putative dehalobox (a stretch of nucleotides resembling the FNR box that bind to the promoter for transcription initiation) (36, 37) were identified by visually inspecting the nucleotide sequences and manually aligning the regions with known motifs.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The dcpA gene sequences from D. mccartyi strains KS and RC were deposited in GenBank under accession numbers JX826286 and JX826287, respectively. The 48 dcpA sequences obtained from environmental samples were deposited under accession numbers JX913691 to JX913735 and KC906160 to KC906162.

RESULTS

cDNA libraries identify the 1,2-D RDase gene.

Using template cDNA derived from the RNA pool of the 1,2-D-grown cultures RC and KS, PCR with the degenerate RDase-targeted primers B1R and RR2F yielded amplicons of approximately 1,500 bp in length (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). No amplification occurred when RNA prior to the reverse transcription (RT) step was used as the PCR template, confirming that all genomic DNA had been removed from the RNA pool (see Fig. S1). Among 200 E. coli clones screened from the B1R and RR2F amplicon-derived clone libraries of cultures RC and KS, 12 and 10, respectively, had vectors carrying cDNA fragments of the expected size of ∼1,500 bp. Sequence analysis of the 10 KS cDNA library clones with an insert of the correct size revealed a single, 1,486-bp sequence. The sequence included the nearly complete RDase A gene and a partial RDase B gene, indicating that these genes were cotranscribed. An open reading frame corresponding to the RDase B gene start was found 18 nucleotides (nt) downstream of the RDase A gene TAA stop codon and included 35 nt of the adjacent RDase B gene. Analysis of the 12 RC cDNA library clones revealed eight inserts with the same 1,486-bp insert found in the KS cDNA library clones, and four clones had a 1,589-bp insert. The 1,589-bp insert consisted of 1,472 bp of the partial RDase A gene, 19 nt of intergenic region, and 98 bp of a partial RDase B gene. The 1,486-bp insert cloned from both D. mccartyi strain RC and strain KS genes showed 90% sequence identity to a putative RDase gene (gene tag Dehly_1524) found in the genome of the 1,2-D-dechlorinating D. lykanthroporepellens strain BL-DC-9. To rule out the presence of a D. lykanthroporepellens-type population in the RC and KS cultures, PCR with primers targeting the D. lykanthroporepellens 16S rRNA gene was performed; however, DNAs from cultures RC and KS failed to produce an amplicon, confirming that D. lykanthroporepellens was not present in these cultures. The second, 1,589-bp insert found in four RC clones was 99.9% similar to the putative RDase gene RCRdA02 (accession no. EU266045). This gene was almost identical (98 to 99%) to the D. mccartyi RDase genes DehalGT_1352 (accession no. CP001924), cbdbA1638 (accession no. AJ965256), and KSRdA02 (accession no. EU266035) and also demonstrated high similarity (96% nt identity) to FL2RdhA6 in D. mccartyi strain FL2 (accession no. AY374250). Additionally, RCRdA02 shared 98 to 99% nt sequence identity with RDase genes retrieved from the KB-1 and TUT2264 dechlorinating mixed cultures (KB1RdhAB5 [accession no. DQ177510] and TUT2264_rdhA2 [accession no. AB362921]) and from a contaminated site (FtL-RDase-1638 [accession no. EU137843]). At the nucleotide level, no gene in the D. lykanthroporepellens strain BL-DC-9 genome shared similarity with RCRdA02.

Protein assays and LC-MS/MS analysis.

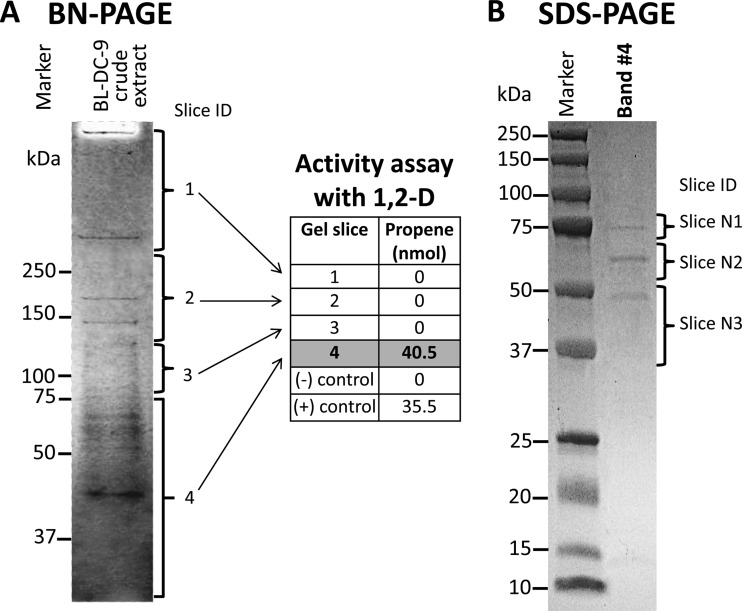

After BN-PAGE separation of D. lykanthroporepellens strain BL-DC-9 proteins, a gel slice representing the section below the 75-kDa marker demonstrated 1,2-D-dechlorinating activity (Fig. 2A, slice 4). Coomassie staining revealed that this gel slice comprised multiple polypeptides (i.e., several visible bands) near the 75- to 55-kDa size marker, with a major band of 45.5 kDa (Fig. 2A). Subsequent SDS-PAGE separation of the proteins eluted from this gel piece exhibited protein bands with masses of 75, 63, and 50 kDa (Fig. 2B, slices N1, N2, and N3).

FIG 2.

Activity assays following BN-PAGE separation of crude extracts of D. lykanthroporepellens BL-DC-9 cells grown with 1,2-D. (A) Coomassie-stained BN-PAGE showing the predominant proteins and the gel sections that were subjected to dechlorination activity testing with 1,2-D. For enzyme activity assays, gel slices from unstained lanes adjacent to the Coomassie-stained lanes were used. (B) Propene formation was observed only in gel slice 4, which was subjected to SDS-PAGE. Three bands were visualized by SDS-PAGE, and gel slices N1, N2, and N3 were further analyzed by LC-MS/MS. DcpA (Dehly_1524) was the only RDase detected in gel slice 4.

LC-MS/MS analysis of the proteins separated by SDS-PAGE identified 15 D. lykanthroporepellens strain BL-DC-9 proteins (Table 3, data for slices N2 and N3). In the N1 gel section, protein levels were too low for confident identification, while in the gel section around 50 kDa (i.e., slice N3), Dehly_0337 (annotated as translation elongation factor Tu) and Dehly_1524 (annotated as an RDase) were the dominant proteins, based on peptide spectral abundances (Table 3). Other peptides associated with gel slice N3 included subunits of the nickel-dependent hydrogenases, encoded by Dehly_0929 and Dehly_0726 (Table 3). Among all the protein fragments recovered from slices N2 and N3, the highest coverage and spectral counts belonged to Dehly_1407, a chaperonin GroEL protein (Table 3, data for slice N2). Dehly_1524 was the only RDase associated with the gel slices (Table 3), corroborating that this enzyme catalyzes 1,2-D-to-propene dichloroelimination. The 1,2-RDase was designated DcpA, encoded by the dcpA gene.

TABLE 3.

D. lykanthroporepellens strain BL-DC-9 proteins identified in gel slice 4, exhibiting 1,2-D-to-propene dechlorination activity following BN-PAGEa

| Gel slice | Gene ID | Protein accession no. | Protein length (aa) | Sequence coverage (%) | No. of distinct peptides | Spectral count | Adjusted NSAF valueb | Protein description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N2 | Dehly_1407 | YP_003759016 | 534 | 33.0 | 17 | 230 | 74,691.4 | Chaperonin GroEL |

| Dehly_0935 | YP_003758558 | 543 | 9.0 | 5 | 12 | 3,832.4 | DAK2 domain fusion protein YloV | |

| Dehly_0744 | YP_003758371 | 526 | 7.0 | 3 | 12 | 3,956.2 | d-3-Phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase | |

| Dehly_1273 | YP_003758885 | 610 | 6.7 | 3 | 13 | 3,695.7 | Hypothetical protein | |

| Dehly_1425 | YP_003759034 | 511 | 7.0 | 3 | 10 | 3,393.6 | Phosphoribosylaminoimidazolecarboxamide formyltransferase/IMP cyclohydrolase | |

| Dehly_1020 | YP_003758642 | 557 | 3.9 | 2 | 10 | 3,113.4 | Arginyl-tRNA synthetase | |

| Dehly_0812 | YP_003758435 | 588 | 4.9 | 2 | 8 | 2,359.4 | Formate-tetrahydrofolate ligase | |

| Dehly_1485 | YP_003759090 | 500 | 4.4 | 2 | 5 | 1,734.1 | Glutamine synthetase | |

| Dehly_0665 | YP_003758293 | 555 | 4.3 | 2 | 4 | 1,249.8 | Dihydroxy acid dehydratase | |

| Dehly_0337 | YP_003757978 | 400 | 5.5 | 2 | 3 | 1,300.6 | Translation elongation factor Tu | |

| Dehly_0353 | YP_003757993 | 515 | 6.6 | 2 | 2 | 673.5 | Carboxyl transferase | |

| N3 | Dehly_0337 | YP_003757978 | 400 | 9.8 | 4 | 23 | 53,241.2 | Translation elongation factor Tu |

| Dehly_1524 | YP_003759128 | 482 | 6.6 | 3 | 14 | 26,894.3 | Reductive dehalogenase | |

| Dehly_0929 | YP_003758552 | 423 | 6.9 | 2 | 3 | 6,566.9 | Nickel-dependent hydrogenase large subunit | |

| Dehly_1407 | YP_003759016 | 534 | 6.4 | 3 | 3 | 5,201.9 | Chaperonin GroEL | |

| Dehly_0692 | YP_003758320 | 437 | 3.9 | 2 | 2 | 4,237.7 | Diaminopimelate decarboxylase | |

| Dehly_0726 | YP_003758353 | 480 | 3.5 | 2 | 2 | 3,858.1 | Nickel-dependent hydrogenase large subunit |

Gel slice 4 was further separated by SDS-PAGE into gel slices N1, N2, and N3. Proteins are listed in order of decreasing spectral counts. Data for DcpA are indicated in bold. In the N1 gel slice, protein levels were too low for confident identification, and no data for N1 are included in the table.

NSAF stands for “normalized spectral abundance factor” and is used for quantitative proteomic analysis by taking the MS/MS spectral counts of a matching peptide from a protein and dividing it by its length (number of amino acids), resulting in a spectral abundance factor (SAF). The SAF is normalized against the sum of all SAFs for the sample, resulting in the NSAF value. Adjusted NSAF values allow for direct comparison of a protein's abundance between individual runs and samples.

Primer walking and characterization of dcpAB gene cassette.

Since the degenerate primer pair B1R and RRF2 did not amplify the complete dcpA and dcpB gene sequences, the entire dcpAB genes from strains D. mccartyi RC and KS were obtained using primer walking approaches. The application of primers dcp_up120F and dcpA-1449R yielded ∼1,569-bp PCR products and extended the sequence 89 bp upstream of the ATG start codon (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). The final and complete assembly of the dcpA gene sequences derived from D. mccartyi strains RC and KS were nearly identical (99.8% nt sequence identity), and the translated protein sequence differed by only a single aa, at position 85 (i.e., a serine [S] in strain RC was replaced by a leucine [L] in strain KS). Inspection of the region upstream of the start codon identified the putative ribosome binding site (RBS or Shine-Dalgarno sequence) AGAGG, starting 9 nt upstream of the dcpA start codon, and a putative dehalobox (37) was identified 67 nt upstream of dcpA. Primer walking procedures also extended dcpB through the TAA stop codon (an additional 184 bp). The final assembly of the dcpB genes of D. mccartyi strains RC and KS revealed that both sequences shared 99% sequence identity and their corresponding proteins differed in only one aa, with glutamine (Q) replaced by a glutamic acid (E) in strain RC at position 11 (see Fig. S3). Therefore, the WYXW motif, which is conserved in other RDase B proteins, is present in the form WYEW in D. mccartyi strain RC and in the form WYQW in D. mccartyi strain KS and D. lykanthroporepellens strain BL-DC-9 (see Fig. S3). The final assembly of the dcpAB gene cassette of D. mccartyi strains RC and KS consisted of a 1,455-nt (484 aa) dcpA gene and a 219-nt (73 aa) dcpB gene separated by an 18-nt spacer.

Computational characterization of DcpA and DcpB.

The Tat signal peptide RRDFMK, starting at position 9 and with a predicted peptide cleavage site between aa positions 30 and 31, was identified (see Fig. S4 in the supplemental material). The mature DcpA protein (i.e., after cleavage of the signal peptide) in D. mccartyi strain RC and strain KS had a predicted isoelectric point (pI) of 5.99 and a molecular mass of 50.8 kDa. The corrinoid binding motif DXHXXG-X41–42-SXL-X24–28-GG, found in several corrinoid-containing enzymes from prokaryotes (38), was not present in DcpA, but a putative corrinoid binding sequence (DHXG-X39-S-X32-G) close to the C terminus was identified (see Fig. S4). The DcpA proteins of both D. mccartyi strain RC and strain KS share two identical iron-sulfur cluster binding motifs (FCX2CX2CX3CP and CX2CX3C) (Fig. 1; see Fig. S4).

The topology of the DcpB protein revealed two predicted transmembrane regions, spanning from positions 12 to 32 and 41 to 61 (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). Additional characteristics included two inside loops (i.e., facing the cytoplasm), from aa positions 1 to 11 and 62 to 73, and one outside loop (i.e., facing the periplasm), from positions 33 to 40 (see Fig. S3). Furthermore, a putative RBS (AGAGG) for initiation of translation was detected in the small 18-nt intergenic region separating dcpA and dcpB.

dcpA sequence similarity to other RDase genes.

The dcpA genes of D. mccartyi strains RC and KS and D. lykanthroporepellens strain BL-DC-9 (Dehly_1524) shared 60% overall nt identity to the pseudogene DET0162, identified in the genome of D. mccartyi strain 195, and an even greater sequence identity (66%; 260 of 395 nt) occurred near the 3′ end. The DET0162 pseudogene is 1,464 nt long and has a point mutation that results in a premature stop codon leading to a truncated, 59-aa-long polypeptide. If completely translated, the gene would encode a putative RDase of approximately 486 aa with all the common RDase features, including the Tat RRDFMK motif near the N terminus and the FCX2CX2CX3CP and CX2CX3C iron-sulfur cluster binding motifs near the C terminus. The 486-aa protein would have 45% aa identity to the DcpA proteins of strain RC and strain KS and 46% identity to DcpA of strain BL-DC-9. Located 129 bp downstream of the 3′ end of the DET0162 pseudogene is a characteristic B gene (DET0163). This B gene also shared 55 to 56% nt sequence identity (44 to 47% aa sequence identity) with the dcpB genes of D. lykanthroporepellens strain BL-DC-9 (Dehly_1525) and D. mccartyi strains RC and KS.

The D. mccartyi DcpA proteins shared 92% sequence identity and 95% sequence similarity with the D. lykanthroporepellens strain BL-DC-9 DcpA protein (Dehly_1524). DcpA shared no more than 34% aa sequence identity with other Chloroflexi RDases and other RDase sequences deposited in databases. Inspection of the recently closed genome of the 1,2-D-to-propene-dechlorinating Desulfitobacterium dichloroeliminans strain DCA1 (LMG P-21439) (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genome/?term=txid871963) revealed no RDase with >18% aa sequence identity to DcpA. Recently, a nomenclature for RDases was proposed (39), and DcpA clusters nearest to the RD_OG20 group, which is composed of BAV1_0104, cbdbA88, and DET0311. This ortholog group shares only 31 to 34% aa identity and no more than 45% similarity with DcpA, suggesting that the D. lykanthroporepellens and D. mccartyi DcpA sequences form a separate cluster (see Fig. S5 in the supplemental material).

dcpA-targeted PCR and qPCR.

PCR with primers dcpA-360F and dcpA-1449R produced a single amplicon of the expected size (1,089 bp) when applied to genomic DNAs from cultures RC and KS and D. lykanthroporepellens strain BL-DC-9. No amplicons were obtained with template DNA from D. mccartyi strain GT, which cannot dechlorinate 1,2-D. qPCR standard curves generated with primers dcpA-1257F and dcpA-1449R, using SYBR green reporter chemistry, exhibited linear amplification ranging from 1.7 to 1.7 × 108 16S rRNA gene copies per μl of template DNA (e.g., slope = −3.4, y intercept = 36.6, and R2 = 0.999). Melting curve analyses of amplicons generated with genomic DNAs from D. mccartyi culture RC and culture KS and D. lykanthroporepellens strain BLDC-9 showed single, symmetric peaks (suggesting single PCR products), with average melting temperatures (Tm) of 78.5 ± 0.1°C, 79.2 ± 0.1°C, and 78.6 ± 0.1°C, respectively (see Fig. S6 in the supplemental material). TaqMan qPCR assays with the same primer pair combined with the dcpA-1426 probe also exhibited linear amplification over the same range of template DNA concentrations (e.g., slope = −3.5, y intercept = 39.5, and R2 = 0.997) (see Fig. S7).

TaqMan qPCR demonstrated that D. mccartyi cell numbers increased during cultivation with 1,2-D as an electron acceptor. Cultures RC and KS produced 1.8 × 107 ± 0.1 × 107 and 1.4 × 107 ± 0.5 × 107 D. mccartyi cells per μmol of Cl− released. The enumeration of dcpA and the D. mccartyi 16S rRNA gene in replicate cultures of D. mccartyi strains RC and KS demonstrated that both gene targets occurred at similar abundances. In KS cultures, 6.6 × 107 ± 0.4 × 107 D. mccartyi 16S rRNA gene copies and 6.2 × 107 ± 0.4 × 107 dcpA genes were detected per ml of culture suspension. Culture RC produced 6.1 × 107 ± 0.2 × 107 16S rRNA genes and 5.2 × 107 ± 0.3 × 107 dcpA genes per ml of culture. These findings indicate that both D. mccartyi genomes harbor a single dcpA gene. The dcpA-targeted primers dcpA-1257F and dcpA-1449R were also used to quantify the dcpA transcript abundances in D. mccartyi cultures RC and KS. The RT-qPCR results showed the upregulation of dcpA gene transcription in actively dechlorinating RC and KS cultures compared to cultures that had consumed all 1,2-D (Fig. 3).

FIG 3.

Relative transcript copy abundances in cells growing with 1,2-D. dcpA transcript levels were normalized to rpoB or to dcpA gene copy numbers. Triplicate samples were analyzed, and the reported values represent the averages for at least three independent biological cultures. Error bars depict standard errors. Negative numbers represent downregulated target genes, while positive numbers represented upregulated genes. A ratio near unity (close to 1) indicates an insignificant change in the number of dcpA transcripts per rpoB transcript or the ratio of dcpA to D. mccartyi (Dhc) gene copy numbers.

Application of dcpA PCR and qPCR assays to microcosm and environmental samples.

Propene was detected in 1,2-D-amended microcosms established with 5 of the 13 sample materials tested (Table 1). In contaminated sediments from Third Creek, TN, the dcpA gene increased from below the quantification limit to 5.6 × 106 ± 0.1 × 106 copies per ml in propene-producing sediment-free enrichment cultures. Nested PCR assays detected both D. lykanthroporepellens and D. mccartyi 16S rRNA genes in the initial Third Creek sediment samples. qPCR assays indicated that D. mccartyi and D. lykanthroporepellens populations also increased from below the quantification limit in the initial samples to 5.6 × 106 ± 0.6 × 106 and 9.7 × 103 ± 0.3 × 103 gene copies per ml of sediment-free enrichment culture, respectively.

Nested PCR detected the dcpA gene in all aquifer and sediment samples that yielded 1,2-D-dechlorinating microcosms. The only microcosms with positive dcpA detection but without propene formation were established with aquifer materials from the site at Barra Mansa, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. The dcpA gene was not detected in site materials collected from the Waynesboro site and in Ft. Pierce groundwater samples collected outside a 1,2-D plume. Consistent with the absence of the dcpA gene, the microcosms established with these materials failed to dechlorinate 1,2-D (Table 1). Interestingly, three of four wells collected inside the 1,2-D plume at the Ft. Pierce site tested positive for dcpA, consistent with the detection of propene at these well locations.

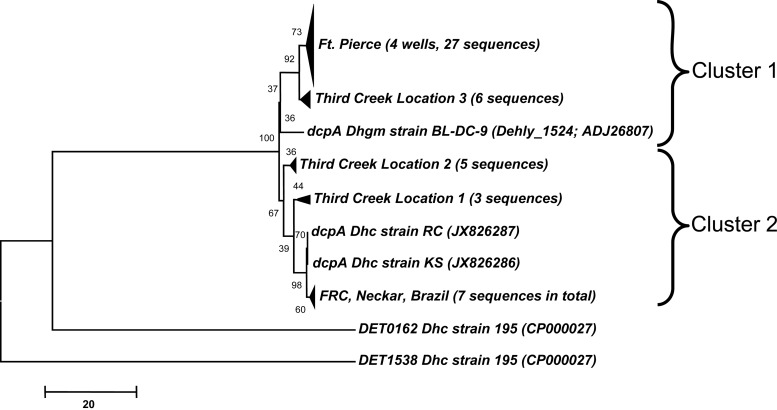

dcpA gene diversity.

The primer pair dcpA-360F and dcpA-1449R retrieved nearly complete (∼1 kb) dcpA amplicons with template DNAs extracted from seven distinct sample materials, and cloning and sequencing efforts generated 48 dcpA sequences (Fig. 4). Distance analysis of the DcpA sequences (a total of 247 aa was analyzed) and high bootstrap values indicated that the sequences formed two distinct phylogenetic clusters. Cluster 1 included 33 environmental DcpA sequences most similar (93 to 95%) to D. lykanthroporepellens DcpA (Dehly_1524), and cluster 2 comprised 15 DcpA sequences most similar (95 to 99%) to the DcpA proteins of D. mccartyi strains RC and KS. All but one of the 48 DcpA sequences contained both of the characteristic iron-sulfur cluster binding motifs (FCX2CX2CX3CP and CX2CX3C) (see Fig. S8 in the supplemental material). Overall, the translated environmental dcpA sequences differed by 5 to 7% from the DcpA gene of D. lykanthroporepellens strain BL-DC-9 and by 1 to 8% from the DcpA genes of D. mccartyi strains KS and RC. Interestingly, the deduced DcpA sequences from different continents (i.e., Europe and South America) shared >98% sequence identity, indicating that this RDase either is highly conserved or was recently disseminated.

FIG 4.

Phylogenetic tree of DcpA sequences. The neighbor-joining tree is drawn to scale, with branch lengths in the same units as those of the evolutionary distances used to infer the phylogenetic relationships. All positions containing gaps and missing data were eliminated, and a total of 247 aa positions were included in the final data set. Evolutionary distances were computed using the number of differences method, and the scale bar indicates the number of amino acid differences per sequence. Samples that clustered together were grouped, and numbers in parentheses indicate the number of sequences of each group. The RDase DET1538 of D. mccartyi strain 195 served as an outgroup to root the tree. Cluster 1 shares highest aa sequence identity to DcpA of D. lykanthroporepellens strain BL-DC-9 (93 to 95%), while cluster 2 comprises sequences with higher sequence identity to DcpA of D. mccartyi strains KS and RC (95 to 99%).

DISCUSSION

D. lykanthroporepellens and D. mccartyi populations have been implicated in 1,2-D-to-propene reductive dechlorination (7, 10). Since the D. mccartyi 16S rRNA gene provides insufficient resolution to distinguish strains with the ability to transform 1,2-D from strains lacking this trait, a functional biomarker was sought to support site assessment (i.e., are 1,2-D-dechlorinating populations present?) and bioremediation monitoring (i.e., are 1,2-D-dechlorinating populations active?). An integrated approach combining gene presence, transcription, and enzyme activity implicated dcpA in 1,2-D dichloroelimination to propene. dcpA was cotranscribed with the associated dcpB gene, indicating that polycistronic mRNA was generated (a feature shared with other D. mccartyi RDase genes); a putative RBS preceded both the dcpA and dcpB genes (allowing for translation initiation at multiple sites); and a single chromosomal copy was identified in D. mccartyi strains RC and KS as well as D. lykanthroporepellens strain BL-DC-9. Also, the presence of transcriptional regulatory elements (e.g., a ribosomal binding site and a putative dehalobox box upstream of the dcpA gene start codon) and the results of the experimental transcription studies (cDNA library and RT-qPCR analyses) suggest that dcpA gene activity is regulated, presumably by the presence of 1,2-D.

The gene most similar to dcpA is the pseudogene DET0162, identified in the genome of D. mccartyi strain 195. This pseudogene may be a vestigial remnant of a functional gene that shared a common ancestor with dcpA. Interestingly, the DET0162 pseudogene has the RBS AGGAG and a possible dehalobox, suggesting that this gene is under regulatory control; however, this pseudogene has an alternate GTG start codon, which is less effective than ATG (40). Transcriptional studies targeting the 19 RDase genes of D. mccartyi strain 195 demonstrated that pceA (encoding a PCE RDase), tceA (encoding a trichloroethene [TCE]-to-vinyl chloride [VC] RDase), and DET0162 were the only RDase genes upregulated during growth with PCE or TCE (24). Similar results were reported with PCE-dechlorinating mixed cultures containing D. mccartyi strain 195, where the DET0162 pseudogene and tceA were highly upregulated (26). This pseudogene, along with pceA, exhibited high transcript levels in D. mccartyi strain 195 cultures grown with 2,3-dichlorophenol (24). Although the transcript levels of the pseudogene significantly increased when PCE, TCE, or 2,3-dichlorophenol was provided as an electron acceptor to strain 195 cultures, the translated product was never detected (24), probably because of the premature stop codon and ensuing proteolysis. The original function of this pseudogene remains speculative.

The abundances of D. mccartyi strain RC and strain KS grown with 1,2-D as an electron acceptor (1.8 × 107 ± 0.1 × 107 and 1.4 × 107 ± 0.5 × 107 cells per ml, respectively) were similar to values reported for D. lykanthroporepellens (1.5 × 107 cells per ml) (12). Standard Gibbs free energy calculations indicate that 1,2-D dichloroelimination (the removal of two chlorine substituents from adjacent carbon atoms) yields less energy per chlorine atom released than stepwise hydrogenolysis. 1,2-D dichloroelimination is associated with a change in Gibbs free energy of −183 kJ/mol, which is less than the free energy change associated with stepwise hydrogenolysis (262.5 kJ/mol) (41). Theoretically, organisms capable of 1,2-D hydrogenolysis to a monochlorinated propane consume the same amount of H2 but gain less energy than organisms catalyzing dichloroelimination. Organisms capable of two-step hydrogenolysis to propane would gain more energy but would require twice as much H2. Therefore, organisms capable of 1,2-D dihaloelimination may have an advantage under H2-limiting conditions, but all cultivation efforts yielded cultures performing dichloroelimination even when ample H2 was provided.

Analysis of the D. mccartyi RC cDNA clone library revealed two active RDase genes: RCRdA02 and dcpA. D. lykanthroporepellens strain BL-DC-9 does not possess a homolog of RCRdA02 but does have a highly similar dcpA gene. Furthermore, the RCRdA02 gene has nearly identical orthologs in several D. mccartyi strains that cannot grow with 1,2-D (i.e., strains CBDB1, FL2, and GT). These findings corroborate that dcpA is the 1,2-D RDase gene and also indicate that RCRdA02 is not directly involved in 1,2-D reductive dechlorination. Interestingly, the ortholog of RCRdA02 in strain FL2 (FL2RdhA6) was one of multiple RDase genes transcribed in strain FL2 cultures grown with TCE, cis-1,2-dichloroethene (cis-DCE) (42), and trans-DCE (unpublished results), suggesting that RCRdA02 is not induced by a specific chloro-organic substrate. In previous studies, the RCRdA02 homolog KB1RdhAB5 was transcribed in consortium KB-1 exposed to TCE, cis-DCE, or VC (42), while in the enrichment culture TUT2264, the RCRdA02 homolog TUT2264_rdhA2 was highly transcribed in cultures spiked with PCE (43). Additionally, transcripts of the FtL-RDase-1638 gene (99% nt identity to RCRdA02) were recovered in cDNA libraries established with RNAs extracted from chlorinated ethene-contaminated groundwater (44). Another RDase gene, DET1545, which is 86% identical to RCRdA02 (and whose translated product is 94% identical and 97% similar to the protein encoded by RCRdA02), was highly expressed during the transition to stationary phase (45) and in pseudo-steady state (46) in cultures containing D. mccartyi strain 195. Overall, these findings suggest that the RCRdA02 gene is constitutively transcribed in metabolically active D. mccartyi strains. The quantification of RCRdA02 transcripts in environmental samples may serve as an indicator of general D. mccartyi activity; however, RCRdA02 transcription appears not to be linked to specific reductive dechlorination reactions. Recent studies have demonstrated that stress conditions (i.e., oxygen exposure, heat, or starvation) influence RDase gene transcription, and RDase transcripts can be measured in D. mccartyi cultures not exhibiting reductive dechlorination activity (47, 48). These findings emphasize that D. mccartyi RDase gene activity and/or transcript turnover is poorly understood, and regulatory controls have yet to be identified and verified. Nevertheless, transcriptional analysis applied to cultures amended with a growth-supporting chloro-organic substrate contributed to the identification of RDase genes, including dcpA (this study); bvcA, encoding a DCE and VC RDase (18); and mbrA, encoding a PCE-to-trans-DCE RDase (25).

RDase characterization has been challenging due to the difficulty in obtaining biomass from D. mccartyi and D. lykanthroporepellens pure cultures, the sensitivity of RDases to oxygen, and the lack of a genetic system to heterologously express functional RDases. The utility of the BN-PAGE approach coupled with LC-MS/MS analysis to assign function to RDases has been demonstrated (33, 49); however, functional assignment based solely on in vitro enzyme assays can potentially be misleading because the reduced corrinoid cofactor associated with the RDase can autonomously reductively dechlorinate compounds that are not RDase substrates (50). To assign specific function to the RDase capable of 1,2-D dichloroelimination, an approach involving multiple lines of evidence was employed that combined qPCR and RT-qPCR analyses, BN-PAGE, enzyme activity assays, and SDS-PAGE followed by LC-MS/MS analysis. With available genome sequence information for organohalide-respiring bacteria rapidly increasing, such an approach is recommended for assigning function(s) to as yet undescribed RDase genes.

Protein assays combined with BN-PAGE and LC-MS/MS confirmed that DcpA catalyzed 1,2-D dichloroelimination to propene. The 1,2-D dechlorination activity was detected in gel slice 4, representing the 37- to 75-kDa size range. A recent study found a dominant reductive dechlorination activity associated with the high-molecular-mass fraction near the 242-kDa size marker following BN-PAGE separation (33). RDases with assigned function range in size between 49.7 and 57.7 kDa, suggesting that protein association can occur, resulting in protein complexes that migrate with a larger-than-expected size fraction. Interestingly, some of the peptides that comigrated with DcpA (e.g., the chaperonin GroEL, hydrogenase subunits, and the elongation translation factor Tu) have been shown to be abundant proteins in active D. mccartyi cells (51, 52). The comigration of RDases with GroEL and hydrogenase proteins in BN-PAGE is not unprecedented (33, 49) and could suggest a possible association of these proteins to form an RDase complex. The interaction of RDases with hydrogenases is intriguing, because such complexes could enable direct electron transfer from the hydrogen-oxidizing hydrogenase to the RDase, which then transfers the electrons to the chlorinated electron acceptor. Direct hydrogenase-RDase electron transfer would be consistent with the absence of electron carriers, which have not been identified in D. mccartyi. The chaperonin GroEL may aid in the folding and stabilization of such a hydrogenase-RDase complex. EF-Tu (elongation factor thermo unstable) is a GTP-binding protein involved in protein translation and is abundant in active bacterial cells (53), implying that active protein biosynthesis occurs in 1,2-D-dechlorinating cells. Although RDases are the most direct indicators for reductive dechlorination reactions, general RDase-associated proteins may serve as additional biomarkers for monitoring metabolically active D. mccartyi and D. lykanthroporepellens populations.

Previous studies investigated the environmental distribution of RDase genes with assigned functions (e.g., bvcA, vcrA, and tceA) in sample materials retrieved from aquifers contaminated with chlorinated ethenes (54, 55). The recovered RDase sequences exhibited >95% and 98% identity with known tceA and vcrA genes, respectively, even in samples collected from geographically distinct locations (54–57). Similar results were found in this study, where dcpA sequences retrieved from geographically distinct samples shared >98% sequence identity with D. mccartyi strains RC and KS and the D. lykanthroporepellens BL-DC-9 dcpA sequences. Of course, it is expected that similar RDase gene sequences would be recovered with PCR primers targeting conserved RDase gene motifs. Nevertheless, the primer pair dcpA-360F and dcpA-1449R amplified 1,089-bp dcpA gene fragments with identifiable sequence variability between the conserved primer binding sites, which was useful to improve the understanding of dcpA sequence diversity. This approach revealed two dcpA clades, both of which were captured with the dcpA-targeted PCR approach described herein.

The utility of dcpA-specific nested PCR and qPCR assays for the sensitive detection and enumeration of dcpA genes, respectively, in environmental samples was demonstrated, and the presence and abundance of dcpA correlated with propene formation. Only in the samples from the Barra Mansa site in Brazil was dcpA detected but no 1,2-D dechlorination activity observed in the microcosms. Groundwater from this site contained up to 7,860 μg/liter chloroform (CF) as well as carbon tetrachloride (CT) and 1,1,1-trichloroethane (1,1,1-TCA), which have all been described as potent D. mccartyi inhibitors (58). The microcosms did not produce methane, further supporting the hypothesis that CT, CF, and/or 1,1,1-TCA affected microbial activity, including the 1,2-D-dechlorinating population(s). This observation suggests that 1,2-D bioremediation may require prior removal of inhibitory cocontaminants.

Although other 1,2-D RDases exist (e.g., Desulfitobacterium dichloroeliminans strain DCA1 does not harbor the dcpA gene but dechlorinates 1,2-D to propene), 1,2-D-respiring Chloroflexi organisms appear to be major contributors to this activity at the sites investigated, and the dcpA-targeted PCR assays augment the available toolbox for site assessment and bioremediation monitoring. Carbon stable isotope enrichment factors associated with 1,2-D dichloroelimination in cultures RC and KS harboring the dcpA gene have been determined (59), and a comprehensive molecular biological tool approach can now be applied to tackle 1,2-D-contaminated sites. The application of environmental molecular diagnostics promises to identify sites amenable to bioremediation and to achieve cleanup goals faster, leading to early site closures and realizing significant cost savings to the site owner(s), which will ultimately determine the value of these molecular tools for remediation practice.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by the Strategic Environmental Research and Development Program (SERDP). E.P.-C. acknowledges support through an NSF IGERT fellowship (grant DGE 0114400) and has been a recipient of an NSF Graduate Research Fellowship.

We thank Youlboong Sung, Dora Ogles (Microbial Insights), Renata Ferreira-Lagoa, and Shandra Justicia-Leon for providing sample materials and site information.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 15 November 2013

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/AEM.02927-13.

REFERENCES

- 1.Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR) 1989. Toxicological profile for 1,2-dichloropropane. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Atlanta, GA [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nijhuis TA, Makkee M, Moulijn JA, Weckhuysen BM. 2006. The production of propene oxide: catalytic processes and recent developments. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 45:3447–3459. 10.1021/ie0513090 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zogorski JS, Carter JM, Ivahnenko T, Lapham WW, Moran MJ, Rowe BL, Squillace PJ, Toccalino PL. 2006. Volatile organic compounds in the nation's ground water and drinking-water supply wells. U.S. Geol. Surv. Circ. 129:101. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pacific Biomedical Research Center 1975. Hawaii epidemiologic studies program annual report no. 8, p 176 University of Hawaii, Honolulu, HI [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schlötelburg C, von Wintzingerode C, Hauck R, von Wintzingerode F, Hegemann W, Göbel UB. 2002. Microbial structure of an anaerobic bioreactor population that continuously dechlorinates 1,2-D. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 39:229–237. 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2002.tb00925.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.De Wildeman S, Diekert G, Van Langenhove H, Verstraete W. 2003. Stereoselective microbial dehalorespiration with vicinal dichlorinated alkanes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:5643–5647. 10.1128/AEM.69.9.5643-5647.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moe WM, Yan J, Nobre MF, da Costa MS, Rainey FA. 2009. Dehalogenimonas lykanthroporepellens gen. nov., sp. nov., a reductively dehalogenating bacterium isolated from chlorinated solvent-contaminated groundwater. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 59:2692–2697. 10.1099/ijs.0.011502-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bowman KS, Nobre MF, da Costa MS, Rainey FA, Moe WM. 2013. Dehalogenimonas alkenigignens sp. nov., a chlorinated-alkane-dehalogenating bacterium isolated from groundwater. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 63:1492–1498. 10.1099/ijs.0.045054-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Löffler FE, Champine JE, Ritalahti KM, Sprague SJ, Tiedje JM. 1997. Complete reductive dechlorination of 1,2-dichloropropane by anaerobic bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:2870–2875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ritalahti KM, Löffler FE. 2004. Populations implicated in the anaerobic reductive dechlorination of 1,2-dichloropropane in highly enriched bacterial communities. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:4088–4095. 10.1128/AEM.70.7.4088-4095.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Löffler FE, Yan J, Ritalahti KM, Adrian L, Edwards EA, Konstantinidis KT, Müller JA, Fullerton H, Zinder SH, Spormann AM. 2013. Dehalococcoides mccartyi gen. nov., sp. nov., obligately organohalide-respiring anaerobic bacteria relevant to halogen cycling and bioremediation, belong to a novel bacterial class, Dehalococcoidia classis nov., order Dehalococcoidales ord. nov. and family Dehalococcoidaceae fam. nov., within the phylum Chloroflexi. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 63:625–635. 10.1099/ijs.0.034926-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yan J, Rash BA, Rainey FA, Moe WM. 2009. Isolation of novel bacteria within the Chloroflexi capable of reductive dechlorination of 1,2,3-trichloropropane. Environ. Microbiol. 11:833–843. 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2008.01804.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.He J, Sung Y, Dollhopf ME, Fathepure BZ, Tiedje JM, Löffler FE. 2002. Acetate versus hydrogen as direct electron donors to stimulate the microbial reductive dechlorination process at chloroethene-contaminated sites. Environ. Sci. Technol. 36:3945–3952. 10.1021/es025528d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Löffler FE, Sanford RA, Tiedje JM. 1996. Initial characterization of a reductive dehalogenase from Desulfitobacterium chlororespirans Co23. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 62:3809–3813 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wolin EA, Wolin MJ, Wolfe RS. 1963. Formation of methane by bacterial extracts. J. Biol. Chem. 238:2882–2886 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Amos BK, Christ JA, Abriola LM, Pennell KD, Löffler FE. 2007. Experimental evaluation and mathematical modeling of microbially enhanced tetrachloroethene (PCE) dissolution. Environ. Sci. Technol. 41:963–970. 10.1021/es061438n [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ritalahti KM, Cruz-García C, Padilla-Crespo E, Hatt JK, Löffler FE. 2010. RNA extraction and cDNA analysis for quantitative assessment of biomarker transcripts in groundwater, p 3671–3685 In Timmis KN. (ed), Handbook of hydrocarbon and lipid microbiology. Springer, Berlin, Germany [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krajmalnik-Brown R, Hölscher T, Thomson IN, Saunders FM, Ritalahti KM, Löffler FE. 2004. Genetic identification of a putative vinyl chloride reductase in Dehalococcoides sp. strain BAV1. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:6347–6351. 10.1128/AEM.70.10.6347-6351.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hatt JK, Löffler FE. 2012. Quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) detection chemistries affect enumeration of the Dehalococcoides 16S rRNA gene in groundwater. J. Microbiol. Methods 88:263–270. 10.1016/j.mimet.2011.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ritalahti KM, Amos BK, Sung Y, Wu Q, Koenigsberg SS, Löffler FE. 2006. Quantitative PCR targeting 16S rRNA and reductive dehalogenase genes simultaneously monitors multiple Dehalococcoides strains. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72:2765–2774. 10.1128/AEM.72.4.2765-2774.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.ABI 2005. Applied Biosystems 7900HT fast real-time PCR system and 7300/7500 real-time PCR systems: chemistry guide 4348358, revision E. ABI, Foster City, CA. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bustin SA, Benes V, Garson JA, Hellemans J, Huggett J, Kubista M, Mueller R, Nolan T, Pfaffl MW, Shipley GL, Vandesompele J, Wittwer CT. 2009. The MIQE guidelines: minimum information for publication of quantitative real-time PCR experiments. Clin. Chem. 55:611–622. 10.1373/clinchem.2008.112797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johnson DR, Lee PK, Holmes VF, Alvarez-Cohen L. 2005. An internal reference technique for accurately quantifying specific mRNAs by real-time PCR with application to the tceA reductive dehalogenase gene. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:3866–3871. 10.1128/AEM.71.7.3866-3871.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fung JM, Morris RM, Adrian L, Zinder SH. 2007. Expression of reductive dehalogenase genes in Dehalococcoides ethenogenes strain 195 growing on tetrachloroethene, trichloroethene, or 2,3-dichlorophenol. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73:4439–4445. 10.1128/AEM.00215-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chow WL, Cheng D, Wang S, He J. 2010. Identification and transcriptional analysis of trans-DCE-producing reductive dehalogenases in Dehalococcoides species. ISME J. 4:1020–1030. 10.1038/ismej.2010.27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rahm BG, Morris RM, Richardson RE. 2006. Temporal expression of respiratory genes in an enrichment culture containing Dehalococcoides ethenogenes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72:5486–5491. 10.1128/AEM.00855-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thompson JD, Higgins DG. 1994. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix. Nucleic Acids Res. 22:4673–4680. 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tamura K, Peterson D, Peterson N, Stecher G, Nei M, Kumar S. 2011. MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol. Biol. Evol. 28:2731–2739. 10.1093/molbev/msr121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Saitou N, Nei M. 1987. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol. Biol. Evol. 4:406–425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nei M, Kumar S. 2000. Molecular evolution and phylogenetics. Oxford University Press, New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 31.Felsenstein J. 1985. Confidence limits on phylogenies: an approach using the bootstrap. Evolution 39:783–791. 10.2307/2408678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Seshadri R, Adrian L, Fouts DE, Eisen JA, Phillippy AM, Methe BA, Ward NL, Nelson WC, Deboy RT, Khouri HM, Kolonay JF, Dodson RJ, Daugherty SC, Brinkac LM, Sullivan SA, Madupu R, Nelson KE, Kang KH, Impraim M, Tran K, Robinson JM, Forberger HA, Fraser CM, Zinder SH, Heidelberg JF. 2005. Genome sequence of the PCE-dechlorinating bacterium Dehalococcoides ethenogenes. Science 307:105–108. 10.1126/science.1102226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tang S, Chan WW, Fletcher KE, Seifert J, Liang X, Löffler FE, Edwards EA, Adrian L. 2013. Functional characterization of reductive dehalogenases by using blue native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 79:974–981. 10.1128/AEM.01873-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tabb DL, Fernando CG, Chambers MC. 2007. MyriMatch: highly accurate tandem mass spectral peptide identification by multivariate hypergeometric analysis. J. Proteome Res. 6:654–661. 10.1021/pr0604054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Holman JD, Ma ZQ, Tabb DL. 2012. Identifying proteomic LC-MS/MS data sets with Bumbershoot and IDPicker. Curr. Protoc. Bioinformatics Chapter 13:Unit13.17. 10.1002/0471250953.bi1317s37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Smidt H, van Leest M, van Der Oost J, de Vos WM. 2000. Transcriptional regulation of the cpr gene cluster in ortho-chlorophenol-respiring Desulfitobacterium dehalogenans. J. Bacteriol. 182:5683–5691. 10.1128/JB.182.20.5683-5691.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gábor K, Veríssimo CS, Cyran BC, Ter Horst P, Meijer NP, Smidt H, de Vos WM, van der Oost J. 2006. Characterization of CprK1, a CRP/FNR-type transcriptional regulator of halorespiration from Desulfitobacterium hafniense. J. Bacteriol. 188:2604–2613. 10.1128/JB.188.7.2604-2613.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ludwig ML, Matthews RG. 1997. Structure-based perspectives on B12-dependent enzymes. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 66:269–313. 10.1146/annurev.biochem.66.1.269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hug LA Maphosa F, Leys D, Löffler FE, Smidt H, Edwards EA, Adrian L. 2013. Overview of organohalide-respiring bacteria and a proposal for a classification system for reductive dehalogenases. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 368:20120322. 10.1098/rstb.2012.0322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Reddy P, Peterkofsky A, McKenney K. 1985. Translational efficiency of the Escherichia coli adenylate cyclase gene: mutating the UUG initiation codon to GUG or AUG results in increased gene expression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 82:5656–5660. 10.1073/pnas.82.17.5656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dolfing J, Janssen DB. 1994. Estimates of Gibbs free energies of formation of chlorinated aliphatic compounds. Biodegradation 5:21–28 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Waller AS, Krajmalnik-Brown R, Löffler FE, Edwards EA. 2005. Multiple reductive-dehalogenase-homologous genes are simultaneously transcribed during dechlorination by Dehalococcoides-containing cultures. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:8257–8264. 10.1128/AEM.71.12.8257-8264.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Futamata H, Kaiya S, Sugawara M, Hiraishi A. 2009. Phylogenetic and transcriptional analyses of a tetrachloroethene-dechlorinating “Dehalococcoides” enrichment culture TUT2264 and its reductive-dehalogenase genes. Microbes Environ. 24:330–337. 10.1264/jsme2.ME09133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lee PK, Macbeth TW, Sorenson KJS, Deeb RA, Alvarez-Cohen L. 2008. Quantifying genes and transcripts to assess the in situ physiology of “Dehalococcoides” spp. in a trichloroethene-contaminated groundwater site. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74:2728–2739. 10.1128/AEM.02199-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Johnson DR, Brodie EL, Hubbard AE, Andersen GL, Zinder SH, Alvarez-Cohen L. 2008. Temporal transcriptomic microarray analysis of “Dehalococcoides ethenogenes” strain 195 during the transition into stationary phase. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74:2864–2872. 10.1128/AEM.02208-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rahm BG, Richardson RE. 2008. Correlation of respiratory gene expression levels and pseudo-steady-state PCE respiration rates in Dehalococcoides ethenogenes. Environ. Sci. Technol. 42:1599. 10.1021/es071455s [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Amos BK, Ritalahti KM, Cruz-Garcia C, Padilla-Crespo E, Löffler FE. 2008. Oxygen effect on Dehalococcoides viability and biomarker quantification. Environ. Sci. Technol. 42:5718–5726. 10.1021/es703227g [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fletcher KE, Costanza J, Cruz-Garcia C, Ramaswamy NS, Pennell KD, Löffler FE. 2011. Effects of elevated temperature on Dehalococcoides dechlorination performance and DNA and RNA biomarker abundance. Environ. Sci. Technol. 45:712–718. 10.1021/es1023477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tang S, Edwards EA. 2013. Identification of Dehalobacter reductive dehalogenases that catalyse dechlorination of chloroform, 1,1,1-trichloroethane and 1,1-dichloroethane. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 368:20120318. 10.1098/rstb.2012.0318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Neumann A, Siebert A, Trescher T, Reinhardt S, Wohlfarth G, Diekert G. 2002. Tetrachloroethene reductive dehalogenase of Dehalospirillum multivorans: substrate specificity of the native enzyme and its corrinoid cofactor. Arch. Microbiol. 177:420–426. 10.1007/s00203-002-0409-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Morris RM, Sowell S, Barofsky D, Zinder S, Richardson R. 2006. Transcription and mass-spectroscopic proteomic studies of electron transport oxidoreductases in Dehalococcoides ethenogenes. Environ. Microbiol. 8:1499–1509. 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2006.01090.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Morris RM, Fung JM, Rahm BG, Zhang S, Freedman DL, Zinder SH, Richardson RE. 2007. Comparative proteomics of Dehalococcoides spp. reveals strain-specific peptides associated with activity. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73:320–326. 10.1128/AEM.02129-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Furano AV. 1975. Content of elongation factor Tu in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 72:4780–4784. 10.1073/pnas.72.12.4780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Müller JA, Rosner BM, Von Abendroth G, Meshulam-Simon G, McCarty PL, Spormann AM. 2004. Molecular identification of the catabolic vinyl chloride reductase from Dehalococcoides sp. strain VS and its environmental distribution. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:4880–4888. 10.1128/AEM.70.8.4880-4888.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Krajmalnik-Brown R, Sung Y, Ritalahti KM, Saunders FM, Löffler FE. 2007. Environmental distribution of the trichloroethene reductive dehalogenase gene (tceA) suggests lateral gene transfer among Dehalococcoides. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 59:206–214. 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2006.00243.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sung Y, Ritalahti KM, Apkarian RP, Löffler FE. 2006. Quantitative PCR confirms purity of strain GT, a novel trichloroethene (TCE)-to-ethene-respiring Dehalococcoides isolate. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72:1980–1987. 10.1128/AEM.72.3.1980-1987.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.McMurdie PJ, Hug LA, Edwards EA, Holmes S, Spormann AM. 2011. Site-specific mobilization of vinyl chloride respiration islands by a mechanism common in Dehalococcoides. BMC Genomics 12:287. 10.1186/1471-2164-12-287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Duhamel M, Wehr SD, Yu L, Rizvi H, Seepersad D, Dworatzek S, Cox EE, Edwards EA. 2002. Comparison of anaerobic dechlorinating enrichment cultures maintained on tetrachloroethene, trichloroethene, cis-dichloroethene and vinyl chloride. Water Res. 36:4193–4202. 10.1016/S0043-1354(02)00151-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fletcher KE, Löffler FE, Richnow HH, Nijenhuis I. 2009. Stable carbon isotope fractionation of 1,2-dichloropropane during dichloroelimination by Dehalococcoides populations. Environ. Sci. Technol. 43:6915–6919. 10.1021/es900365x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.He J, Ritalahti KM, Aiello MR, Löffler FE. 2003. Complete detoxification of vinyl chloride (VC) by an anaerobic enrichment culture and identification of the reductively dechlorinating population as a Dehalococcoides species. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:996–1003. 10.1128/AEM.69.2.996-1003.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yan J, Rash BA, Rainey FA, Moe WM. 2009. Detection and quantification of Dehalogenimonas and “Dehalococcoides” populations via PCR-based protocols targeting 16S rRNA genes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75:7560–7564. 10.1128/AEM.01938-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.