Abstract

The Ras-extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) cascade is an important signaling module in cells. One regulator of the Ras-ERK cascade is phosphatidic acid (PA) generated by phospholipase D (PLD) and diacylglycerol kinase (DGK). Using a newly developed PA biosensor, PASS (phosphatidic acid biosensor with superior sensitivity), we found that PA was generated sequentially by PLD and DGK in epidermal growth factor (EGF)-stimulated HCC1806 breast cancer cells. Inhibition of PLD2, one of the two PLD members, was sufficient to eliminate most of the PA production, whereas inhibition of DGK decreased PA production only at the later stages of EGF stimulation, suggesting that PLD2 precedes DGK activation. The temporal production of PA by PLD2 is important for the nuclear activation of ERK. While inhibition of both PLD and DGK had no effect on the overall ERK activity, inhibition of PLD2 but not PLD1 or DGK blocked the nuclear ERK activity in several cancer cell lines. The decrease of active ERK in the nucleus inhibited the activation of Elk1, c-fos, and Fra1, the ERK nuclear targets, leading to decreased proliferation of HCC1806 cells. Together, these findings reveal that PA production by PLD2 determines the output of ERK in cancer cell growth factor signaling.

INTRODUCTION

Phosphatidic acid (PA) has attracted increasing attention in recent years due to its roles as a signaling molecule and as a central intermediate in the synthesis of membrane lipids (1–3). PA can be produced by multiple enzymes, including two well-known families of enzymes: phospholipase D (PLD) and diacylglycerol (DAG) kinase (DGK) (4–7). In mammalian cells, there are two PLD family members, PLD1 and PLD2, which differ strikingly in subcellular localization and function (5, 7). The mammalian DGK family consists of 10 members, classified into five different subtypes characterized by different regulatory domains (6). It has been proposed that activation of distinct PA-generating enzymes at different times and in different subcellular compartments determines the specific cellular functions of PA, including cell proliferation, survival, and migration (1, 5).

One of the most important intracellular signaling pathways involves the cascade of Ras, Raf, MEK, and the extracellular signal-regulated kinases 1 and 2 (ERK1/2, referred to as ERK here) (8, 9). Activated ERK can either remain in the cytoplasm or translocate to the nucleus, where it phosphorylates and activates a number of proteins that control proliferation, differentiation, survival, apoptosis, and development (8–10). The precise outcome of stimulating the Ras-ERK cascade depends on the duration, strength, and localization of the signals (8, 10, 11). It has been reported that PA is involved in the regulation of the Ras-ERK pathway in fibroblasts and lymphocytes (4, 12–14). However, the mechanisms whereby PA regulates the Ras-ERK cascade appear to be very distinct in different cell types. Moreover, it remains unknown how growth factors activate different PA-generating enzymes, i.e., PLD and DGK, and whether PA generated from different sources regulates the Ras-ERK cascade in the same manner. Importantly, signaling by growth factors such as epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and the Ras-ERK cascade is frequently upregulated in many types of cancer (15, 16). Interestingly, the PA-generating enzymes, PLD and DGK, have also been reported to be critical for proliferation, migration, and survival of cancer cells (6, 7, 17). It is not clear how and why dysregulation of the Ras-ERK cascade by PA contributes to cancer initiation and progression.

To study the functions of PA, it is critical to faithfully monitor its spatiotemporal production. Traditionally, PA levels have been measured using biochemical methods such as thin-layer chromatography (TLC) and high-performance liquid chromatography (18). In recent years, identification and quantification of various lipids, including PA, have become more simple and sensitive with substantially improved mass spectrometry analyses (19, 20). However, all these biochemical techniques measure only the total cellular PA level and cannot reveal the intracellular locations of PA production. In addition, when PA is measured by biochemical methods, the relatively high level of PA on the surface of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), where it is used as a precursor for the synthesis of phospholipids and triglycerides (TAG) (3, 21), may mask the changes of the comparatively less abundant PA generated during signaling at the plasma membrane and other intracellular organelles. As an alternative method, changes in phospholipid levels can be detected by using fluorescently tagged protein domains that bind specifically to certain lipids. For example, PH domains from phospholipase Cδ (PLCδ) and AKT have been used widely to monitor phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate [PI(4,5)P2] and phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate [PI(3,4,5)P3], respectively (18, 22). Such reagents have greatly advanced our understanding of the dynamics and functions of phosphatidylinositides. However, despite great interest (23), we still lack a PA biosensor with the specificity and sensitivity comparable to those of the phosphatidylinositide probes.

In the present study, we report the development of a specific and sensitive PA biosensor. Using this new tool, we demonstrate that PA production is differentially controlled by PLD and DGK in epidermal growth factor (EGF) signaling and that PA generated by PLD2 is critical for the nuclear activity of ERK and proliferation in cancer cells. Our findings reveal that PLD2-generated PA determines the signaling output of ERK.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

General reagents and antibodies.

α-Tubulin, Flag, phospho- and total ERK1/2 antibodies, phosphatidylserine (PS), and the PLD inhibitor (PLDi) 5-fluoro-2-indolyl-deschlorohalopemide (FIPI) were from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) (24). The inhibitors for PLD1/2 (VU0155056), PLD1 (PLD1i, VU0359595), and PLD2 (PLD2i, VU0285655-1) were from Avanti Polar Lipids (Alabaster, AL) (25). The DGK inhibitor (DGKi) R59022 was from Calbiochem (La Jolla, CA). EGFR, phospho- and total Elk1, phospho- and total Fra1, total c-Fos, and phospho-Rsk antibodies were from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA). Mouse glutathione S-transferase (GST), phospho-c-Fos, and PLD1 rabbit monoclonal antibodies were from Abcam (Cambridge, MA). PLD2 rabbit polyclonal antibody was kindly provided by Y. Banno (Gifu University of Tokyo, Gifu, Japan). Goat anti-mouse and anti-rabbit IgGs conjugated with Alexa Fluor 680 were from Invitrogen. Goat anti-mouse and anti-rabbit IgGs conjugated with IRDye 800CW were from Rockland Immunochemicals (Gilbertsville, PA). 1,2-Dilauroyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphate (DLPA) was from Echelon (Salt Lake City, UT).

Construction of plasmids.

To generate enhanced green fluorescent protein-PA biosensor with superior sensitivity (EGFP-PASS), a nuclear export sequence (NES) derived from protein kinase A inhibitor α (PKI-α) (26) was added between EGFP and Spo20-PABD cloned in pEGFP-C1 (27, 28). PASS tagged with monomeric GFP or RFP (mGFP or mRFP) was generated by replacing EGFP in the EGFP-PASS with mGFP or mRFP using AgeI and BsrGI sites. Different tags did not change the localization of PASS. All PASS constructs used in the current study are tagged with monomeric GFP and RFP. GST-PASS-His was generated by inserting PASS and a pair of oligonucleotides encoding 6×His into the BamHI site of pGEX-4T1 from GE Healthcare Biosciences (Pittsburgh, PA). The 4E mutant was generated by site-directed mutagenesis using the QuikChange kit from Agilent Technologies (Santa Clara, CA). The lentiviral vectors carrying GFP-PASS and RFP-PASS were subcloned into the NheI and BamHI sites of pCDH-CMV-MCS and pCDH-CMV-MCS-EF1-Puro from System Biosciences (Mountain View, CA), respectively. The small hairpin RNAs (shRNAs) for PLD1 and PLD2 characterized in the previous publications (12, 28–31) were subcloned into the lentiviral vector pLKO.1.

Bacterial expression, purification of recombinant PASS, and liposome pulldown assay.

Expression and purification of GST-PASS-His using Ni2+-chelate chromatography from Qiagen (Valencia, CA) were performed as described before (32). All purified recombinant proteins used in our experiments are >95% pure, as judged by Coomassie blue-stained SDS-PAGE (polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis) gels. The purified proteins were used within 1 week. The preparation of liposomes has been previously described (32, 33). Phosphatidylcholine (POPC), phosphatidylethanolamine (DOPE), and phosphatidic acid (POPA) were from Avanti Polar Lipids, and phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate [PI(4,5)P2] and phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate [PI(3, 4,5)P3] were purchased from Matreya (Pleasant Gap, PA).

Cell culture and treatment.

Cell culture media were from Thermo Fisher (Waltham, MA). Sera were from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). All cell lines were from ATCC (Manassas, VA). CHO cells were grown in Ham's F-12 medium. HCC1806 and HCC827 cells were grown in RPMI 1640 medium. MDA-MB-468 and A431 cells were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium. BT-20 cells were grown in Eagle's minimum essential medium. All media were supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). For inhibitor treatment, cells were preincubated with dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) or inhibitors for 1 h. Transient transfection in CHO cells was done using the deacylated polyethylenimine (PEI) reagent (34). Unless specified, cells were serum starved overnight and then stimulated with 100 nM PMA, 100 μM PA (DLPA), 100 μM PS, or 100 ng/ml EGF for the indicated time. For cell proliferation measurements, cells were seeded in 6-well plates in RPMI 1640 medium containing 0.1% FBS and 5 ng/ml EGF in the presence of DMSO or inhibitors or in the presence of control and PLD shRNAs. Viable cells were measured by trypan blue exclusion.

Lentivirus production and transduction.

The delivery of expression constructs in HCC1806 cells was through lentiviral infection. Viruses were generated in TLA-293T cells from Thermo Fisher by cotransfecting four plasmids including the lentiviral vector, pMDLg/pRRE, pRSV-Rev, and pMD2.G using Lipofectamine and Plus reagent from Invitrogen. At 48 h and 72 h posttransfection, virus-containing supernatants were collected for infection. The cells were used for experiments 2 to 3 days postinfection.

Western blot analysis.

Fluorescently labeled secondary antibodies were used for Western blotting and detected by the Li-Cor Odyssey infrared imaging system from Li-Cor Biotechnology (Lincoln, NE). Band intensity was quantified using the program supplied by the manufacturer. The bands on Western blots were defined by identical region of interest and measured as integrated pixel intensity for all samples. The background was determined by measuring the average pixel intensity of a user-defined area.

Confocal microscopy.

All images were captured with a 60× oil-immersion objective on a Nikon A1 confocal microscope (Melville, NY). Fields with moderate cell confluence were selected for measurement. For visualizing GFP and RFP fluorescence of PASS, cells grown on coverslips were transiently transfected (CHO cells) or infected with lentiviruses (HCC1806 cells) and then directly fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 10 min at room temperature. After several PBS washes, the coverslips were mounted onto slides using 4% propyl gallate mounting solution. The fluorescent images of GFP and RFP of random fields were collected. For each treatment, at least five fields, including more than 50 cells, were quantified. Cells with saturated exposure were not used for quantification. The change in the plasma membrane localization was quantified using the line pixel intensity histogram in NIH Image J as described previously (22). A line was randomly drawn to span a large area of the cytoplasm but not the nucleus. The pixel intensity of the two most outside peaks represented the PASS on the plasma membrane, while the average value between represented that in the cytoplasm.

For pERK staining, cells were stained with a pERK1/2 antibody–Alexa Fluor 594-conjugated goat anti-mouse secondary antibody and 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) after cold methanol fixation at −20°C for 10 min. After the nuclei were defined with DAPI staining, the cytoplasmic and nuclear areas were manually marked and then measured for the fluorescent intensity of pERK staining using NIH Image J. The change of pERK localization was represented as the ratio of pERK in the nucleus and cytoplasm.

Statistics.

All statistical differences were evaluated between control and each of the treatments using two-tailed Student's t test. All data are shown as means ± standard deviations (SD).

RESULTS

Development of a sensitive PA biosensor.

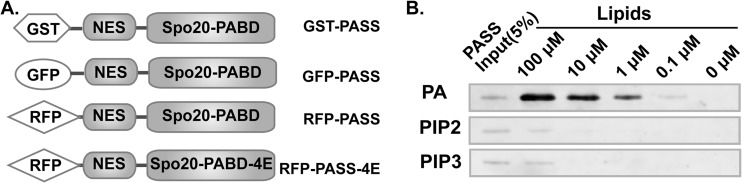

To study the regulation and functions of PA in distinct cellular compartments, it is important to precisely monitor the spatial and temporal production of PA. Currently, the most widely used PA biosensor is the PA-binding domain derived from Saccharomyces cerevisiae protein Spo20 (Spo20-PABD) (23, 28, 35). However, green fluorescent protein (GFP)-tagged Spo20-PABD responded only to strong stimuli such as phorbol-12-myristate-13-acetate (PMA) (24) and depolarizing concentrations of potassium (35) or some cellular processes such as cell replating (28). We were unable to detect changes of PA levels in cells stimulated with ligands for membrane receptors using this PA biosensor. Even in cells stimulated with PMA, a potent activator of PLD activity (36, 37), the membrane localization of GFP-Spo20-PABD was barely visible in most cells unless the images were overexposed. These results seem contradictory to the original reports that Spo20-PABD binds to PA with exceptional sensitivity and specificity in vitro (23, 38, 39). Since GFP-Spo20-PABD predominantly localizes to the nucleus, we reason that the nuclear localization prevents it from accessing PA molecules on the plasma membrane or other cytoplasmic organelles. To improve the sensitivity of Spo20-PABD, we added a nuclear export sequence (NES) derived from protein kinase A inhibitor α (PKI-α) (26) to the N terminus of the Spo20-PABD (Fig. 1A) and named the resulting construct PASS (phosphatidic acid biosensor with superior sensitivity) due to its exceptional sensitivity in detecting the cellular PA levels (further demonstrated in Fig. 2 and 3). We first tested whether the addition of NES affected the binding specificity of PA in vitro using recombinant PASS protein purified from Escherichia coli and synthetic liposomes. As controls, we also included liposomes containing PI(4,5)P2 or PI(3,4,5)P3, since the original Spo20-PABD also showed some binding to these lipids (23, 38). As expected, we found that PASS specifically bound to PA-containing liposomes in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 1B). In sharp contrast, PASS bound to PI(4,5)P2- or PI(3,4,5)P3-containing liposomes with much lower affinity (Fig. 1B). These results are consistent with the previous finding that Spo20-PABD binds to PA selectively and confirm that addition of the NES does not change the PA-binding specificity of PASS.

FIG 1.

Design of a new phosphatidic acid (PA) biosensor. (A) Schematic of the design of new PA biosensors. To improve the PA accessibility, a nuclear export sequence (NES) derived from protein kinase A inhibitor was added to the N terminus of Spo20-PABD, which was derived from yeast t-SNEAR Spo20 protein. The new NES-Spo20-PABD is named PASS (phosphatidic acid biosensor with superior sensitivity). PASS-4E is a mutant in which four lysine residues were mutated to glutamic acid (K66E, K68E, R71E, and K73E), which disrupted the PA binding of the original Spo20-PABD (38). (B) PASS specifically binds to PA. Purified GST-PASS-His was mixed with sucrose-loaded liposomes containing PA, phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate [PI(4,5)P2], and phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-bisphosphate [PI(3,4,5)P3]. After centrifugation, the pellets bound to liposomes were analyzed by Western blotting using a GST antibody.

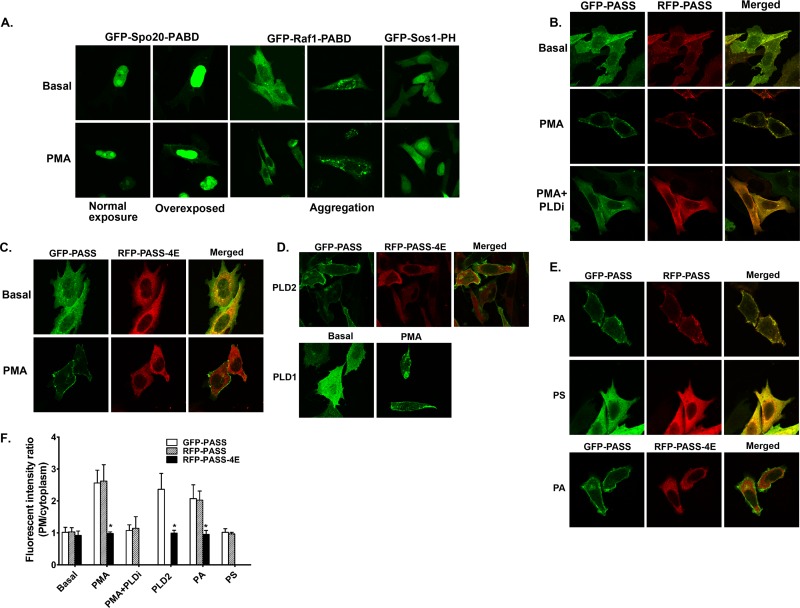

FIG 2.

PASS specifically monitors the changes in cellular PA levels. (A) Minimal membrane localization of previous PA biosensors (GFP-Spo20-PABD, GFP-Sos1-PH, and Raf1-PABD) in PMA-stimulated CHO cells. The original GFP-Spo20-PABD was dominantly localized in the nucleus, and its plasma membrane localization was observed only in PMA-stimulated cells when the images were overexposed. GFP-Raf1-PABD aggregates in some cells. (B) The majority of GFP- and RFP-PASS is translocated to the plasma membrane upon PMA stimulation, which can be inhibited by the PLD inhibitor FIPI (PLDi, 0.75 μM). (C) PMA stimulation recruited GFP-PASS but not RFP-PASS-4E to the plasma membrane. (D) Increased PLD activity recruited PASS to membranes. Overexpression of PLD2 recruited GFP-PASS but not RFP-PASS-4E to the plasma membrane in the same cells. Overexpression of PLD1 increased the localization of PASS on intracellular vesicles upon PMA stimulation (compared to panels B and C). (E) Delivery of synthetic PA (100 μM) but not PS (100 μM) recruited PASS to the plasma membrane. (F) Quantification of the fluorescent intensity of PASS at the plasma membrane relative to that of the cytoplasm in the experiment in panels B to E. n = 3. *, P < 0.001 versus GFP-PASS.

We next tested whether PASS can be used to measure PA levels in intact CHO cells when fused with either a green fluorescent protein (GFP) or a red fluorescent protein (RFP). PLD activity is very low to undetectable in unstimulated (basal) CHO cells but can be elevated by stimulation with PMA or by overexpression of PLD2 (24, 28, 40). As observed before, the original GFP-Spo20-PABD mainly localized to the nucleus under both basal and PMA-stimulated conditions (28, 35) (Fig. 2A). Two other PA biosensors, GFP-Raf1-PABD (27, 41) and GFP-Sos1-PH (12), localized to the cytoplasm under basal conditions and only partially translocated to membranes under PMA-stimulated conditions (Fig. 2A). In addition, GFP-Raf1-PABD often aggregated in some cells (Fig. 2A) and induced cell toxicity when it was expressed for more than 2 days (not shown). In contrast, both GFP- and RFP-tagged PASS localized diffusely in the cytoplasm under nonstimulatory conditions but translocated to the plasma membrane and endosome-like vesicles upon PMA stimulation (Fig. 2B) when PLD was activated (29, 33, 42). Furthermore, the plasma membrane translocation of PASS induced by PMA was blocked when PLD activity was inhibited by FIPI (24) (Fig. 2B). The mutation of four lysine residues to glutamic acid (K66E, K68E, R71E, and K73E, called 4E here) on the original Spo20-PABD disrupted its binding to PA (38). We generated the same 4E mutations in RFP-PASS. As expected, PMA stimulation caused the plasma membrane translocation of the wild-type GFP-PASS but not that of the PA-binding-deficient mutant RFP-PASS-4E (Fig. 2C). Another way to increase the cellular PA level is through overexpression of PLD2, which has a high basal activity (42, 43). As before, GFP-PASS, but not the RFP-PASS-4E mutant, was recruited to the plasma membranes in CHO cells stably overexpressing mouse PLD2 (29) (Fig. 2D). In contrast, PASS localized diffusely in the cytoplasm and translocated only to the plasma membrane and intracellular vesicles upon PMA treatment in CHO cells stably overexpressing human PLD1 (Fig. 2D), which has a low basal activity and is activated by external stimulation (30, 36). The increased PASS localization on intracellular vesicles in PLD1-overexpressing cells suggests the activation of PLD1 on these organelles, where the majority of PLD1 is localized (7, 33). Finally, we tested whether addition of exogenous PA to culture medium was able to recruit GFP-PASS to the plasma membrane; PA can be rapidly incorporated into the plasma membrane and can induce cellular responses (12, 44, 45). As expected, exogenously added PA stimulated translocation of GFP- and RFP-PASS to the plasma membrane but failed to induce the translocation of RFP-PASS-4E (Fig. 2E). In contrast, external addition of another negatively charged phospholipid, phosphatidylserine (PS), did not cause recruitment of GFP- and RFP-PASS to the plasma membrane (Fig. 2E), further supporting the specificity of this biosensor.

EGF regulation of temporal PA production in HCC1806 breast cancer cells.

Our ultimate goal was to study PA dynamics during the course of growth factor stimulation. Due to their poor sensitivity, we were not able to observe consistent membrane translocation of several previously generated PA biosensors, i.e., GFP-Raf1-PABD, GFP-SOS-PH, and GFP-Spo20-PABD, in cells stimulated with EGF or other growth factors. Having established the specificity and improved sensitivity of PASS, we used this probe to examine growth factor signaling in cancer cells. We initially used HCC1806 cells, a good experimental model for EGF signaling and aggressive triple-negative breast cancer (46, 47). GFP-PASS diffusely localized in the cytoplasm of serum-starved HCC1806 cells but quickly translocated to the plasma membrane within 1 min of EGF stimulation (Fig. 3A and B), reaching maximal levels at 3 min. Most of the GFP-PASS returned to the cytoplasm after 30 min (Fig. 3A and B). To our knowledge, PASS is the only probe capable of detecting such dynamic changes in PA subcellular distribution in response to physiological stimuli like growth factors.

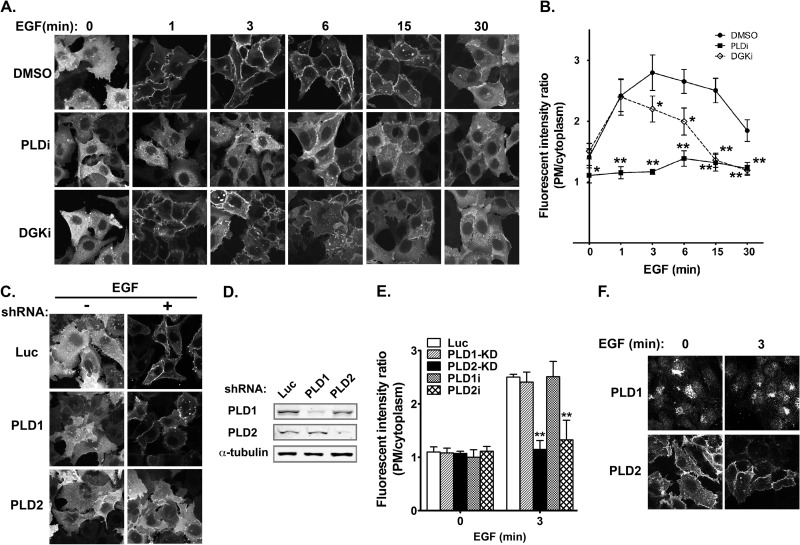

FIG 3.

Temporal production of PA by PLD and DGK in EGF-stimulated HCC1806 breast cancer cells. (A) Different effects of PLD and DGK inhibition on EGF-promoted plasma membrane translocation of GFP-PASS. Cells were preincubated with either DMSO, PLD inhibitor FIPI (PLDi, 0.75 μM), or DGK inhibitor (DGKi, 10 μM) for 1 h and then stimulated with EGF for the indicated time. (B) Quantification of the fluorescent intensity of GFP-PASS at the plasma membrane relative to that of the cytoplasm in the same experiment in panel A. n = 3. *, P < 0.01, and **, P < 0.001 versus DMSO treatment at the same time points. (C) PLD2 is responsible for the generation of PA on the plasma membrane. HCC1806 cells expressing GFP-PASS were infected with lentiviruses carrying luciferase (Luc) and PLD1 and PLD2 shRNAs and stimulated with EGF for 3 min. (D) Western blot analysis of PLD1 and PLD2 knockdown. (E) Quantification of the fluorescent intensity of GFP-PASS at the plasma membrane relative to that of the cytoplasm in the same experiment in panel C and those treated with PLD1 and PLD2 inhibitor (PLD1i, 5 μM; PLD2i, 5 μM). n = 3. **, P < 0.001 versus Luc shRNA or DMSO treatment. (F) PLD1 and PLD2 subcellular localization in HCC1806 cells. Cells expressing Flag-PLD1 or Flag-PLD2 stimulated with or without EGF were stained with an anti-Flag antibody.

Two major sources of PA are phosphatidylcholine and diacylglycerol (DAG), which are used as the substrates by PLD and DGK, respectively. To determine the source of PA in response to EGF, we treated cells with PLD or DGK inhibitors. Interestingly, PLD and DGK inhibitors showed different effects on the EGF-dependent translocation of GFP-PASS. The PLD inhibitor FIPI almost completely abolished the translocation of GFP-PASS to the membrane (Fig. 3A and B). In contrast, the DGK inhibitor R59022 blocked only the late (≥3-min) but not the early (1-min) component of GFP-PASS translocation (Fig. 3A and B). These results suggest that upon EGF stimulation, PA is sequentially generated by PLD and DGK. To determine the PLD isoform responsible for PA generation in response to EGF, we examined the localization of PASS in HCC1806 cells infected with lentiviruses carrying either control luciferase (Luc) small hairpin RNAs (shRNAs) or shRNA targeting PLD1 or PLD2 (12, 28, 29) or treated with PLD isoform-specific inhibitors (25). Only PLD2 shRNA or inhibitor, but not the control, PLD1 shRNA or inhibitor, blocked the plasma membrane translocation of PASS triggered by EGF stimulation (Fig. 3C to E). In addition, PLD2 was mainly localized on the plasma membrane in HCC1806 cells before and after EGF stimulation, whereas PLD1 was mainly localized to perinuclear vesicles (Fig. 3F). Taken together, these results suggest that PLD2 is the predominant source of PA.

PLD2-generated PA is important for EGF-triggered nuclear ERK activation.

Since PA regulates the Ras-ERK cascade in fibroblasts and lymphocytes (4, 12–14), we investigated whether PA generated from PLD and DGK also regulates ERK activation in cancer cells. ERK activity (as measured by phosphorylated ERK1/2 [pERK]) was low in nonstimulated HCC1806 cells and was not changed by treatments with the PLD and DGK inhibitors (Fig. 4A and B). EGF stimulation triggered a rapid increase in pERK levels, which reached a maximum at 3 min and was maintained for more than 2 h. However, inhibition of either PLD or DGK did not affect the formation of pERK level in EGF-stimulated HCC1806 cells, as measured by Western blotting (Fig. 4A and B). Downregulation of the expression of PLD isoforms using shRNAs also failed to affect ERK phosphorylation (Fig. 4C and D). We next assessed ERK activation and localization by monitoring pERK in the nucleus and cytoplasm using quantitative fluorescence microscopy. The staining of activated ERK (pERK) in untreated cells was already strong in the cytoplasm 3 min after EGF stimulation, and by 6 min, activated ERK became abundant in the nucleus (Fig. 4E and F). Addition of PLD and DGK inhibitors did not affect ERK activation or alter its kinetics of appearance in the cytoplasm. However, the PLD inhibitor significantly blocked the appearance of nuclear pERK staining after 3 min of EGF stimulation. In contrast, the DGK inhibitor only slightly decreased the nuclear pERK staining at all the time points tested (Fig. 4E and F).

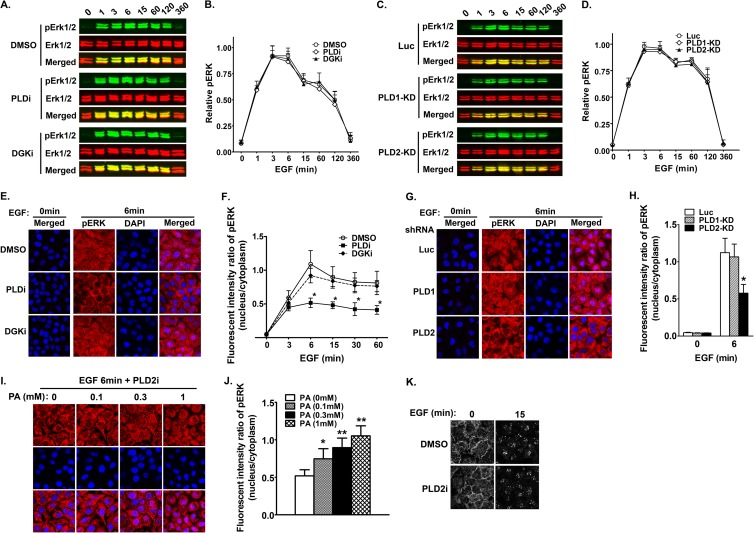

FIG 4.

PLD2 modulates the nuclear activity of ERK in EGF-stimulated cancer cells. (A) Inhibition of either PLD (PLDi, 0.75 μM) or DGK (DGKi, 10 μM) has no effect on the global phosphorylation of ERK in HCC1806 cells. Serum-starved cells were preincubated with inhibitors and then stimulated with EGF for the indicated time. Phospho-ERK1/2 (pERK) and total ERK1/2 were detected on the same membranes by the Li-Cor Odyssey infrared imaging system using a mouse monoclonal antibody and a rabbit polyclonal antibody, respectively. (B) Quantification of the relative pixel intensity of pERK levels in the same experiment in panel A. pERK levels were normalized by total ERK of the same samples. n = 3. (C) Downregulation of PLD1 and PLD2 by shRNAs does not affect the global activation of ERK. Serum-starved cells expressing luciferase (Luc), PLD1, or PLD2 were stimulated with EGF for the indicated time. Phospho-ERK1/2 (pERK) and total ERK1/2 were detected as described for panel A. (D) Quantification of the relative pixel intensity of pERK levels in the same experiment in panel C. pERK levels were normalized by total ERK of the same samples. n = 3. (E) PLD inhibitor decreases the nuclear translocation of pERK. Cells grown on coverslips were treated; stimulated for 0, 3, 6, 15, 30, and 60 min, as described for panel A; and stained for a pERK antibody (only the images at 6 min of EGF stimulation are shown). (F) Quantification of the fluorescent intensity of pERK in the nucleus relative to that of the cytoplasm in panel C. n = 3. *, P < 0.001 versus DMSO treatment at the same time points. (G) PLD2 knockdown decreases the nuclear translocation of pERK. Cells expressing shRNAs were grown on coverslips, stimulated with EGF for 6 min, and stained for a pERK antibody. (H) Quantification of the fluorescent intensity of pERK in the nucleus relative to that of the cytoplasm in panel E. n = 3. *, P < 0.001 versus Luc shRNA. (I) Exogenous PA rescues reduced nuclear pERK staining caused by PLD2 inhibitor (5 μM) in a dose-dependent manner. Serum-starved cells were pretreated by exogenous PA in indicated concentrations 20 min before EGF stimulation. (J) Quantification of the fluorescent intensity of pERK in the nucleus relative to that of the cytoplasm in panel I. n = 3. *, P < 0.01, and **, P < 0.001 versus cells without PA addition. (K) PLD2 inhibition does not affect EGFR internalization. 1806 cells pretreated with DMSO or PLD2 inhibitor (5 μM) were stimulated with EGF for 0, 3, 6, 15, and 30 min and then stained for EGFR antibody. There is no difference in the localizations of EGFR on the plasma membrane and endosomes. Only results from 0 and 15 min are shown.

We then examined which PLD isoform was responsible for regulating nuclear ERK activity using shRNAs. While expression of Luc and PLD1 shRNAs did not change the nuclear and cytoplasmic distribution of pERK in cells stimulated with EGF, PLD2 shRNA inhibited the appearance of nuclear pERK staining (Fig. 4G and H), as found in cells treated with pan-PLD inhibitor. To further confirm that PA is responsible for PLD2 regulation of nuclear ERK activity, we treated HCC1806 cells with both PLD2 inhibitor and different concentrations of PA. Addition of exogenous PA rescued the decrease in pERK staining in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 4I and J). These results suggest that PLD2 activity is required for the nuclear translocation of activated ERK. Activations of EGFR on the plasma membrane and endosomes lead to selective activation of ERK on different subcellular compartments or distinct biological activities (8, 10, 48, 49). Previous studies in fibroblasts found that overexpression of catalytically inactive mutants for PLD1 and PLD2 blocked the activation of ERK by inhibiting the endocytosis of EGFR (50). To determine if PLD2 regulates ERK activation in the nucleus through modulating EGFR endocytosis in HCC1806 cells, we also examined the localization of EGFR in the presence and absence of PLD2 inhibitor. PLD2 inhibitor treatment did not seem to affect the localization of EGFR before and after EGF stimulation (Fig. 4K). This result, together with the dominant plasma membrane localization of PLD2 and PASS (Fig. 3), suggests that PLD2 regulation of the nuclear ERK activity is independent of EGFR endocytosis.

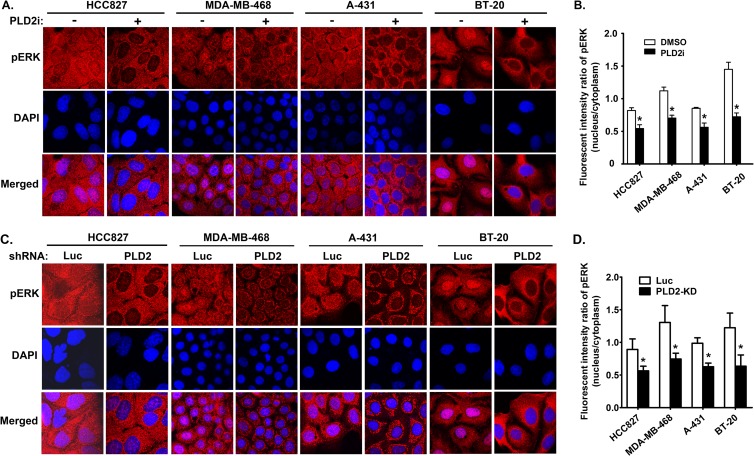

We then addressed the question whether PLD2 also controls the activation of ERK in the nucleus in other cancer cells treated with EGF. Both PLD2 inhibitor and shRNAs significantly blocked the nuclear staining of pERK in all four cancer cell lines that we tested: HCC827 (lung cancer), MDA-MB-468 and BT-20 (breast cancer), and A431 (skin cancer) (Fig. 5), suggesting that PLD2 regulation of nuclear ERK activity is a universal phenomenon in cancer cells.

FIG 5.

PLD2 regulation of the nuclear ERK activity is a common mechanism of modulating EGF signaling pathway in cancer cells. (A) Serum-starved cancer cells were preincubated with either DMSO or PLD2 inhibitor (5 μM) and then stimulated with EGF. The images shown were from the time points of EGF stimulation at which pERK reached to the maximal levels, which varied in different cancer cell lines, e.g., 6 min for HCC827, 6 min for MDA-MB-468, 3 min for A-431, and 3 min for BT-20. (C) Cancer cells expressing luciferase (Luc) control and PLD2 shRNAs were stimulated with EGF like those in panel A. (B and D) Quantification of the fluorescent intensity of pERK in the nucleus relative to that of the cytoplasm in panels A and C. n = 3. *, P < 0.001 versus DMSO or Luc shRNA control in the same cell lines.

Inhibition of PLD2 suppressed the activity of Elk1 and cell proliferation in HCC1806 cells.

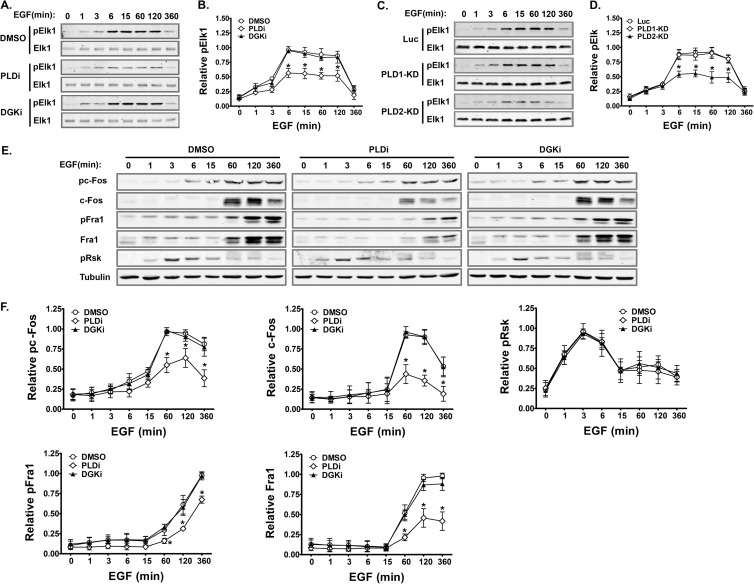

After translocation into the nucleus, active ERK phosphorylates several proteins involved in transcriptional regulation. One of the best-studied ERK targets in the nucleus is Elk1 (11, 51). Consistent with the decrease in pERK in the nucleus, we found that the PLD inhibitor caused a decrease in Elk1 phosphorylation, whereas the DGK inhibitor did not (Fig. 6A and B). Moreover, only PLD2 shRNA, not PLD1 shRNA, inhibited Elk1 phosphorylation (Fig. 6C and D), supporting our findings that PLD2 is specifically required for ERK activity in the nucleus in HCC1806 cells. We also checked the phosphorylation of other ERK substrates. Without phosphorylation, c-Fos and Fra1, the other two nuclear substrates of ERK, undergo rapid degradation; c-Fos and Fra1 are stabilized when phosphorylated by ERK (52–54). As expected, EGF stimulation increased both phosphorylation and total protein levels of c-Fos and Fra1, which were inhibited by PLD but not DGK inhibitor treatment (Fig. 6E and F). In contrast, inhibition of PLD and DGK had no effect on phosphorylation and total protein levels of a cytoplasmic substrate of ERK, Rsk (8, 11) (Fig. 6E and F).

FIG 6.

Inhibition of PLD2 decreases the phosphorylation and protein levels of ERK nuclear substrates. (A, C, and E) Serum-starved HCC1806 cells pretreated with inhibitors (A and E) or expressing shRNAs (C) were stimulated with EGF for the indicated time. Total cell lysates were collected for Western blot analyses of indicated proteins. (B, D, and F) Quantification of the relative pixel intensity of phosphorylated and total proteins in the same experiment in panels A, C, and E. pElk1 levels were normalized by total Elk of the same samples. Phosphorylated and total levels of other proteins were normalized by α-tubulin of the same samples. PLDi, 0.75 μM; DGKi, 10 μM. n = 3. *, P < 0.01 versus DMSO or Luc shRNA treatment at the same time points.

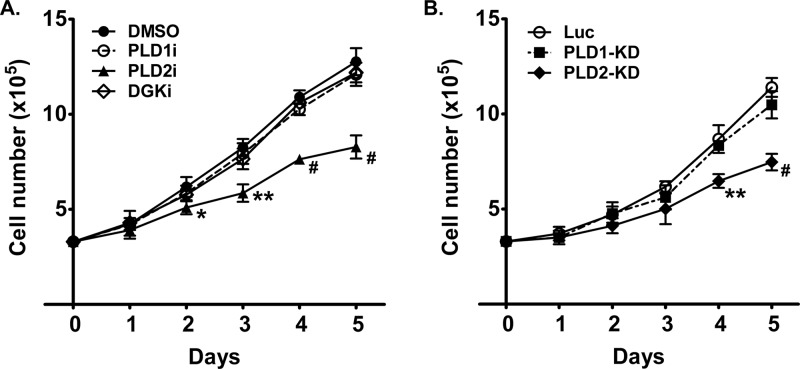

Phosphorylation of ERK nuclear targets increases their affinity for the serum response factor and thus enhances transcription of proliferation-promoting genes (16, 51). The observation that PLD2 inhibition decreased the activity of Elk1, c-Fos, and Fra1 implies that PLD2 activity is required for cell proliferation. To test this hypothesis, we examined cell proliferation in HCC1806 cells in the presence of inhibitors or shRNAs. As expected, the rate of cell proliferation corresponded to the phosphorylation and protein levels of Elk1, c-Fos, and Fra1. Cells treated with a PLD1 inhibitor or DGK inhibitor or expressing PLD1 shRNA showed proliferation rates similar to those of the controls (Fig. 7). However, cells treated with the PLD2 inhibitor or expressing PLD2 shRNA displayed marked decreases in cell proliferation (Fig. 7). These results suggest that PLD2 regulates cell proliferation through modulating the activity of nuclear ERK and its nuclear substrates in HCC1806 breast cancer cells.

FIG 7.

Inhibition of PLD2 decreases the proliferation of HCC1806 cells. (A) Inhibitor treatment. (B) PLD1 and PLD2 knockdown by shRNA expression. Cells were seeded in 6-well plates in RPMI 1640 medium containing 0.1% FBS and 5 ng/ml EGF in the presence of DMSO or inhibitors (PLD1i, 5 μM; PLD2i, 5 μM; DGKi, 10 μM) or in the presence of control and PLD shRNAs. Viable cells were measured by trypan blue exclusion. n = 3. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; #, P < 0.001; all are versus DMSO treatment or Luc shRNA at the same time points.

DISCUSSION

The new biosensor PASS offers a useful tool to study phospholipid signaling.

The ability to precisely monitor the dynamics of PA in different subcellular locations is important for understanding the role of PA signaling in cells. We and others have developed several PA biosensors, i.e., the PA-binding region of Raf-1 (Raf1-PABD) (41) and Spo20-PABD (28, 35), the Sos1 PH domain (12), and the Pii Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET) biosensors derived from Dock2 and Sos1-PH (55). However, compared to the phosphoinositide probes, none of these PA biosensors has been widely used, because they either lack sufficient sensitivity, require a special microscopy setup, or monitor PA production only in certain membrane compartments. The PA biosensor PASS developed in the current study has circumvented these problems. The specificity of PASS as a PA biosensor has been validated by a series of in vitro and in vivo experiments: (i) it bound to PA with high affinity and specificity, as shown by a liposome pulldown assay using the purified recombinant protein; (ii) increasing cellular PA levels by PMA stimulation, exogenous addition of PA, or overexpression of PLD2 promoted the plasma membrane binding of PASS tagged with either GFP or RFP; (iii) association of PASS with the membrane was abolished by treatment with PLD inhibitors and expression of PLD2 shRNA; (iv) point mutations that disrupt PA binding in vitro inhibited the recruitment of PASS to the membrane.

The most significant improvement of PASS is its exceptional sensitivity. We have attempted to use several previously developed PA biosensors, i.e., Raf1-PABD, Spo20-PABD, and Sos1-PH, to monitor PA levels in various cells. However, only a small fraction of these biosensors, if any, translocated to membranes upon PMA (Fig. 2A) and growth factor stimulation. PASS is by far the only PA biosensor that quickly responds to stimulation and binds to the plasma membrane of the various cell types that we have tested. In addition, GFP-Raf1-PABD also aggregates in cells and causes cell toxicity. The binding of Sos1-PH to both PI(4,5)P2 and PA also limits its use as a PA-specific biosensor (12). To increase PA detection, previous PA biosensors derived from Spo20-PABD contain tandem repeats of Spo20-PABD (35, 56). We find that PASS described in our current work (containing one copy of Spo20-PABD fused to NES) responds to stimulation equally well or better while having lower background membrane binding. In addition, we also observed that PASS labeling of some intracellular vesicles, presumably endosomes, is further increased by PLD1 overexpression in PMA-stimulated cells (Fig. 2). These results support the previous findings that PLD and DGK function on both the plasma membrane and endosomes (4–7). Moreover, a tandem repeat version of PASS labels also the endoplasmic reticulum in macrophages and HeLa and HEK293 cells (57). This is particularly interesting since PASS is the only PA biosensor currently known to label the PA pool at the endoplasmic reticulum, which is the site of phospholipid and triglyceride synthesis (3). Finally, when paired with specific membrane markers, the new biosensor may also be used for fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy-Förster resonance energy transfer (FLIM-FRET) or FRET analysis to examine the production of PA in different membrane domains. Compared to the Pii FRET sensors (55), the pairing of PASS with an independent membrane marker should provide a more reliable assessment of the sites of PA production. It is noteworthy that, to increase their sensitivity, the Pii biosensors are targeted to the plasma membrane through the C terminus of K-Ras (55). Since the C terminus of K-Ras resides only in a subdomain of the plasma membrane (58, 59), the Pii biosensors cannot, in principle, monitor the PA generated in other plasma membrane domains or in intracellular organelles.

Differential activation and functions of PLD and DGK in growth factor signaling in cancer cells.

In mammalian cells, there are two PLD family members and 10 members in the DGK family (4–7). It has been unclear how different PA-generating enzymes contribute to PA production upon activation of a particular signaling pathway and whether different sources of PA perform the same functions. An important finding from our experiments is that EGF triggers a sequential activation of PLD and DGK in distinct membrane nanodomains. Moreover, our results also suggest that DGK activation may be dependent on PLD activity. It is likely that, as an early event in EGF signaling, PLD2 activation is required for the activation of DGK or for the production of DAG, the substrate of DGK. More work is still needed to further investigate the cross talk between PLD and DGK. This includes monitoring the production of both PA and DAG using PASS and DAG biosensors and examining the spatiotemporal activation of their downstream signaling pathways, in cells where PLD or DGK is inhibited individually or simultaneously. In combination with small-molecule inhibitors and RNA interference, the newly developed PASS should be a useful tool in determining the regulation of individual PA-generating enzymes and of their cellular functions under different physiological and pathological conditions.

PLD and DGK differentially regulate Ras-ERK signaling in cancer cells.

Various mechanisms are thought to ensure the specific outcomes of Ras-ERK signaling (60). However, little is known about how and why the activation of the Ras-ERK components in separate cellular compartments might be regulated. Previous studies have suggested that the site where Ras is activated dictates the nature of the downstream signals and of subsequent biological outputs elicited (60–62). For example, Ras activated on the plasma membrane led to the translocation of activated ERK to the nucleus, whereas active ERK was restricted to the Golgi complex when Ras was activated in that compartment (63). These findings are also consistent with the observation that Ras activated on the Golgi complex was fully dispensable for proliferation and transformation (61). Interestingly, we found that PLD2 activity is important for the translocation of activated ERK to the nucleus in cancer cells upon growth factor stimulation. In this regard, it is important to note that at the early stages of EGF stimulation, PA is generated by PLD2 but not by DGK. Growth factor activation of ERK on the plasma membrane requires the binding of Raf, MEK, and ERK to the scaffold protein KSR1 (9, 64). However, only activated MEK and ERK transport to the nucleus (9, 64), suggesting that disassembly of the Raf/MEK/ERK/KSR1 complex is prerequisite to pERK nuclear translocation. It is therefore conceivable that the stability of the Raf/MEK/ERK/KSR1 complex determines the cytoplasmic and nuclear destination of the pERK, a mechanism similar to those used to retain pERK on the endosomes by β-arrestin-2 and on the Golgi complex by another scaffold protein, Sef (63, 64). Interestingly, PA binds to several components of the ERK cascade on the plasma membrane, such as Sos1, Raf1, and KSR1 (12, 41, 65). It is likely that PLD2-generated PA association with Raf1, KSR1, or other scaffold proteins potentially weakens their binding to MEK and ERK, therefore allowing MEK/ERK nuclear translocation in cancer cells.

There are clear differences between the mechanisms through which PLD2-generated PA regulates the Ras-ERK cascade in cancer cells and other cell types. In EGF-stimulated fibroblasts, PLD2-generated PA directly regulates the activity of total Ras and ERK levels though Sos1, a Ras guanine exchange factor (12), or Raf1 (41). In lymphocyte function-associated antigen-1-stimulated lymphocytes, PLD2-generated PA activates Ras indirectly when being converted to DAG by PA phosphatases, which then activate a different Ras guanine exchange factor, RasGRP1 (14). Our findings that the precise control of PA production by PLD2 is critical for the delivery of active ERK to the nucleus of cancer cells contribute a mechanistic insight into many previous observations. It is possible that different expression levels of mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) components, such as Sos1, Raf1, and scaffold proteins, and PA-generating enzymes, such as PLD and DGK, in different cell types affect the duration, magnitude, and compartmentalization of ERK, leading to different biological outcomes. PLD expression and activity are elevated in a variety of human cancer tissues (66–71) and human cancer cell lines (72–76). Interestingly, high levels of PLD2 activity also correlate with more aggressive cancer phenotypes (77). Moreover, it has been proposed that PLD2 could be a “driver” in breast tumorigenesis, based on the relatively high rate of somatic mutation of PLD2 found in a sequencing analysis of human breast cancer patients (78). Finally, consistent with elevated PLD expression and activity, PLD has been reported to be important for cell proliferation, survival, and migration in many cancer cell lines (79, 80). It is therefore important to clarify how upregulation of PLD2 expression and activity may “rewire” the MAPK pathway in cancer cells. Further understanding the unique role of PLD2 in cancer cell signaling may help us design strategies for the treatment of human malignancies.

In summary, the present studies demonstrate that the new PA biosensor PASS is capable of recognizing PA with unprecedented specificity and sensitivity, which allows us to monitor the spatiotemporal changes of PA at the single-cell level. Analysis of cellular PA with this biosensor revealed that EGF stimulation activates PLD2 and DGK sequentially. Because the spatiotemporal production of PA by PLD2 is important for the nuclear ERK activity and proliferation, the use of this novel probe should facilitate our research into the biology of both normal and cancerous cells.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the U.S. Army Medical Research and Materiel Command W81XWH-10-1-0624 (to G.D.) and the National Institutes of Health grant GM066717 (to J.F.H.).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 28 October 2013

REFERENCES

- 1.Wang X, Devaiah SP, Zhang W, Welti R. 2006. Signaling functions of phosphatidic acid. Prog. Lipid Res. 45:250–278. 10.1016/j.plipres.2006.01.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hancock JF. 2007. PA promoted to manager. Nat. Cell Biol. 9:615–617. 10.1038/ncb0607-615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carman GM, Han GS. 2011. Regulation of phospholipid synthesis in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 80:859–883. 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060409-092229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang Y, Du G. 2009. Phosphatidic acid signaling regulation of Ras superfamily of small guanosine triphosphatases. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1791:850–855. 10.1016/j.bbalip.2009.05.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Selvy PE, Lavieri RR, Lindsley CW, Brown HA. 2011. Phospholipase D: enzymology, functionality, and chemical modulation. Chem. Rev. 111:6064–6119. 10.1021/cr200296t [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shulga YV, Topham MK, Epand RM. 2011. Regulation and functions of diacylglycerol kinases. Chem. Rev. 111:6186–6208. 10.1021/cr1004106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peng X, Frohman MA. 2012. Mammalian phospholipase D physiological and pathological roles. Acta Physiol. 204:219–226. 10.1111/j.1748-1716.2011.02298.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Murphy LO, Blenis J. 2006. MAPK signal specificity: the right place at the right time. Trends Biochem. Sci. 31:268–275. 10.1016/j.tibs.2006.03.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McKay MM, Morrison DK. 2007. Integrating signals from RTKs to ERK/MAPK. Oncogene 26:3113–3121. 10.1038/sj.onc.1210394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ebisuya M, Kondoh K, Nishida E. 2005. The duration, magnitude and compartmentalization of ERK MAP kinase activity: mechanisms for providing signaling specificity. J. Cell Sci. 118:2997–3002. 10.1242/jcs.02505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mebratu Y, Tesfaigzi Y. 2009. How ERK1/2 activation controls cell proliferation and cell death: is subcellular localization the answer? Cell Cycle 8:1168–1175. 10.4161/cc.8.8.8147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhao C, Du G, Skowronek K, Frohman MA, Bar-Sagi D. 2007. Phospholipase D2-generated phosphatidic acid couples EGFR stimulation to Ras activation by Sos. Nat. Cell Biol. 9:706–712. 10.1038/ncb1594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rizzo MA, Shome K, Vasudevan C, Stolz DB, Sung T-C, Frohman MA, Watkins SC, Romero G. 1999. Phospholipase D and its product, phosphatidic acid, mediate agonist-dependent Raf-1 translocation to the plasma membrane and the activation of the MAP kinase pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 274:1131–1139. 10.1074/jbc.274.2.1131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mor A, Campi G, Du G, Zheng Y, Foster DA, Dustin ML, Philips MR. 2007. The lymphocyte function-associated antigen-1 receptor costimulates plasma membrane Ras via phospholipase D2. Nat. Cell Biol. 9:713–719. 10.1038/ncb1592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dhillon AS, Hagan S, Rath O, Kolch W. 2007. MAP kinase signalling pathways in cancer. Oncogene 26:3279–3290. 10.1038/sj.onc.1210421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roberts PJ, Der CJ. 2007. Targeting the Raf-MEK-ERK mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade for the treatment of cancer. Oncogene 26:3291–3310. 10.1038/sj.onc.1210422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Park JB, Lee CS, Jang JH, Ghim J, Kim YJ, You S, Hwang D, Suh PG, Ryu SH. 2012. Phospholipase signalling networks in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 12:782–792. 10.1038/nrc3379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rusten TE, Stenmark H. 2006. Analyzing phosphoinositides and their interacting proteins. Nat. Methods 3:251–258. 10.1038/nmeth867 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ivanova PT, Milne SB, Myers DS, Brown HA. 2009. Lipidomics: a mass spectrometry based systems level analysis of cellular lipids. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 13:526–531. 10.1016/j.cbpa.2009.08.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oliveira TG, Chan RB, Tian H, Laredo M, Shui G, Staniszewski A, Zhang H, Wang L, Kim TW, Duff KE, Wenk MR, Arancio O, Di Paolo G. 2010. Phospholipase d2 ablation ameliorates Alzheimer's disease-linked synaptic dysfunction and cognitive deficits. J. Neurosci. 30:16419–16428. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3317-10.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Athenstaedt K, Daum G. 1999. Phosphatidic acid, a key intermediate in lipid metabolism. Eur. J. Biochem. 266:1–16. 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1999.00822.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Balla T, Varnai P. 2002. Visualizing cellular phosphoinositide pools with GFP-fused protein-modules. Sci. STKE 2002(125):pl3. 10.1126/scisignal.1252002pl3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kassas N, Tryoen-Toth P, Corrotte M, Thahouly T, Bader MF, Grant NJ, Vitale N. 2012. Genetically encoded probes for phosphatidic acid. Methods Cell Biol. 108:445–459. 10.1016/B978-0-12-386487-1.00020-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Su W, Yeku O, Olepu S, Genna A, Park JS, Ren H, Du G, Gelb MH, Morris AJ, Frohman MA. 2009. 5-Fluoro-2-indolyl des-chlorohalopemide (FIPI), a phospholipase D pharmacological inhibitor that alters cell spreading and inhibits chemotaxis. Mol. Pharmacol. 75:437–446. 10.1124/mol.108.053298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Scott SA, Selvy PE, Buck JR, Cho HP, Criswell TL, Thomas AL, Armstrong MD, Arteaga CL, Lindsley CW, Brown HA. 2009. Design of isoform-selective phospholipase D inhibitors that modulate cancer cell invasiveness. Nat. Chem. Biol. 5:108–117. 10.1038/nchembio.140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Henderson BR, Eleftheriou A. 2000. A comparison of the activity, sequence specificity, and CRM1-dependence of different nuclear export signals. Exp. Cell Res. 256:213–224. 10.1006/excr.2000.4825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Corrotte M, Chasserot-Golaz S, Huang P, Du G, Ktistakis NT, Frohman MA, Vitale N, Bader MF, Grant NJ. 2006. Dynamics and function of phospholipase D and phosphatidic acid during phagocytosis. Traffic 7:365–377. 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2006.00389.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Du G, Frohman MA. 2009. A lipid-signaled myosin phosphatase surge disperses cortical contractile force early in cell spreading. Mol. Biol. Cell 20:200–208. 10.1091/mbc.E08-06-0555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Du G, Huang P, Liang BT, Frohman MA. 2004. Phospholipase D2 localizes to the plasma membrane and regulates angiotensin II receptor endocytosis. Mol. Biol. Cell 15:1024–1030. 10.1091/mbc.E03-09-0673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Su W, Chardin P, Yamazaki M, Kanaho Y, Du G. 2006. RhoA-mediated phospholipase D1 signaling is not required for the formation of stress fibers and focal adhesions. Cell. Signal. 18:469–478. 10.1016/j.cellsig.2005.05.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mor A, Wynne JP, Ahearn IM, Dustin ML, Du G, Philips MR. 2009. Phospholipase D1 regulates lymphocyte adhesion via upregulation of Rap1 at the plasma membrane. Mol. Cell. Biol. 29:3297–3306. 10.1128/MCB.00366-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Roach AN, Wang Z, Wu P, Zhang F, Chan RB, Yonekubo Y, Di Paolo G, Gorfe AA, Du G. 2012. Phosphatidic acid regulation of PIPKI is critical for actin cytoskeletal reorganization. J. Lipid Res. 53:2598–2609. 10.1194/jlr.M028597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Du G, Altshuller YM, Vitale N, Huang P, Chasserot-Golaz S, Morris AJ, Bader MF, Frohman MA. 2003. Regulation of phospholipase D1 subcellular cycling through coordination of multiple membrane association motifs. J. Cell Biol. 162:305–315. 10.1083/jcb.200302033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thomas M, Lu JJ, Ge Q, Zhang C, Chen J, Klibanov AM. 2005. Full deacylation of polyethylenimine dramatically boosts its gene delivery efficiency and specificity to mouse lung. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102:5679–5684. 10.1073/pnas.0502067102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zeniou-Meyer M, Zabari N, Ashery U, Chasserot-Golaz S, Haeberle AM, Demais V, Bailly Y, Gottfried I, Nakanishi H, Neiman AM, Du G, Frohman MA, Bader MF, Vitale N. 2007. Phospholipase D1 production of phosphatidic acid at the plasma membrane promotes exocytosis of large dense-core granules at a late stage. J. Biol. Chem. 282:21746–21757. 10.1074/jbc.M702968200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xiao N, Du G, Frohman MA. 2005. Peroxiredoxin II functions as a signal terminator for H2O2-activated phospholipase D1. FEBS J. 272:3929–3937. 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2005.04809.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Du G, Morris AJ, Sciorra VA, Frohman MA. 2002. G-protein-coupled receptor regulation of phospholipase D. Methods Enzymol. 345:265–274. 10.1016/S0076-6879(02)45022-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nakanishi H, de los Santos P, Neiman AM. 2004. Positive and negative regulation of a SNARE protein by control of intracellular localization. Mol. Biol. Cell 15:1802–1815. 10.1091/mbc.E03-11-0798 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu S, Wilson KA, Rice-Stitt T, Neiman AM, McNew JA. 2007. In vitro fusion catalyzed by the sporulation-specific t-SNARE light-chain Spo20p is stimulated by phosphatidic acid. Traffic 8:1630–1643. 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2007.00628.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Du G, Altshuller YM, Kim Y, Han JM, Ryu SH, Morris AJ, Frohman MA. 2000. Dual requirement for rho and protein kinase C in direct activation of phospholipase D1 through G protein-coupled receptor signaling. Mol. Biol. Cell 11:4359–4368. 10.1091/mbc.11.12.4359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rizzo MA, Shome K, Watkins SC, Romero G. 2000. The recruitment of Raf-1 to membranes is mediated by direct interaction with phosphatidic acid and is independent of association with Ras. J. Biol. Chem. 275:23911–23918. 10.1074/jbc.M001553200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jenkins GM, Frohman MA. 2005. Phospholipase D: a lipid centric review. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 62:2305–2316. 10.1007/s00018-005-5195-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Colley WC, Sung TC, Roll R, Jenco J, Hammond SM, Altshuller Y, Bar-Sagi D, Morris AJ, Frohman MA. 1997. Phospholipase D2, a distinct phospholipase D isoform with novel regulatory properties that provokes cytoskeletal reorganization. Curr. Biol. 7:191–201. 10.1016/S0960-9822(97)70090-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fang Y, Vilella-Bach M, Bachmann R, Flanigan A, Chen J. 2001. Phosphatidic acid-mediated mitogenic activation of mTOR signaling. Science 294:1942–1945. 10.1126/science.1066015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nishikimi A, Fukuhara H, Su W, Hongu T, Takasuga S, Mihara H, Cao Q, Sanematsu F, Kanai M, Hasegawa H, Tanaka Y, Shibasaki M, Kanaho Y, Sasaki T, Frohman MA, Fukui Y. 2009. Sequential regulation of DOCK2 dynamics by two phospholipids during neutrophil chemotaxis. Science 324:384–387. 10.1126/science.1170179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Volk-Draper LD, Rajput S, Hall KL, Wilber A, Ran S. 2012. Novel model for basaloid triple-negative breast cancer: behavior in vivo and response to therapy. Neoplasia 14:926–942. 10.1593/neo.12956 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lehmann BD, Bauer JA, Chen X, Sanders ME, Chakravarthy AB, Shyr Y, Pietenpol JA. 2011. Identification of human triple-negative breast cancer subtypes and preclinical models for selection of targeted therapies. J. Clin. Invest. 121:2750–2767. 10.1172/JCI45014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kranenburg O, Verlaan I, Moolenaar WH. 1999. Dynamin is required for the activation of mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase by MAP kinase kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 274:35301–35304. 10.1074/jbc.274.50.35301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vieira AV, Lamaze C, Schmid SL. 1996. Control of EGF receptor signaling by clathrin-mediated endocytosis. Science 274:2086–2089. 10.1126/science.274.5295.2086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shen Y, Xu L, Foster DA. 2001. Role for phospholipase D in receptor-mediated endocytosis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21:595–602. 10.1128/MCB.21.2.595-602.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Whitmarsh AJ, Shore P, Sharrocks AD, Davis RJ. 1995. Integration of MAP kinase signal transduction pathways at the serum response element. Science 269:403–407. 10.1126/science.7618106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Murphy LO, Smith S, Chen RH, Fingar DC, Blenis J. 2002. Molecular interpretation of ERK signal duration by immediate early gene products. Nat. Cell Biol. 4:556–564. 10.1038/ncb822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Okazaki K, Sagata N. 1995. The Mos/MAP kinase pathway stabilizes c-Fos by phosphorylation and augments its transforming activity in NIH 3T3 cells. EMBO J. 14:5048–5059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Basbous J, Chalbos D, Hipskind R, Jariel-Encontre I, Piechaczyk M. 2007. Ubiquitin-independent proteasomal degradation of Fra-1 is antagonized by Erk1/2 pathway-mediated phosphorylation of a unique C-terminal destabilizer. Mol. Cell. Biol. 27:3936–3950. 10.1128/MCB.01776-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nishioka T, Frohman MA, Matsuda M, Kiyokawa E. 2010. Heterogeneity of phosphatidic acid levels and distribution at the plasma membrane in living cells as visualized by a Foster resonance energy transfer (FRET) biosensor. J. Biol. Chem. 285:35979–35987. 10.1074/jbc.M110.153007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ariotti N, Liang H, Xu Y, Zhang Y, Yonekubo Y, Inder K, Du G, Parton RG, Hancock JF, Plowman SJ. 2010. Epidermal growth factor receptor activation remodels the plasma membrane lipid environment to induce nanocluster formation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 30:3795–3804. 10.1128/MCB.01615-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bohdanowicz M, Schlam D, Hermansson M, Rizzuti D, Fairn GD, Ueyama T, Somerharju P, Du G, Grinstein S. 2013. Phosphatidic acid is required for the constitutive ruffling and macropinocytosis of phagocytes. Mol. Biol. Cell 24:1700–1712. 10.1091/mbc.E12-11-0789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hancock JF. 2006. Lipid rafts: contentious only from simplistic standpoints. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 7:456–462. 10.1038/nrm1925 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Harding AS, Hancock JF. 2008. Using plasma membrane nanoclusters to build better signaling circuits. Trends Cell Biol. 18:364–371. 10.1016/j.tcb.2008.05.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Prior IA, Hancock JF. 2012. Ras trafficking, localization and compartmentalized signalling. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 23:145–153. 10.1016/j.semcdb.2011.09.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Matallanas D, Sanz-Moreno V, Arozarena I, Calvo F, Agudo-Ibanez L, Santos E, Berciano MT, Crespo P. 2006. Distinct utilization of effectors and biological outcomes resulting from site-specific Ras activation: Ras functions in lipid rafts and Golgi complex are dispensable for proliferation and transformation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 26:100–116. 10.1128/MCB.26.1.100-116.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cheng CM, Li H, Gasman S, Huang J, Schiff R, Chang EC. 2011. Compartmentalized Ras proteins transform NIH 3T3 cells with different efficiencies. Mol. Cell. Biol. 31:983–997. 10.1128/MCB.00137-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Torii S, Kusakabe M, Yamamoto T, Maekawa M, Nishida E. 2004. Sef is a spatial regulator for Ras/MAP kinase signaling. Dev. Cell 7:33–44. 10.1016/j.devcel.2004.05.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kolch W. 2005. Coordinating ERK/MAPK signalling through scaffolds and inhibitors. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 6:827–837. 10.1038/nrm1743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kraft CA, Garrido JL, Fluharty E, Leiva-Vega L, Romero G. 2008. Role of phosphatidic acid in the coupling of the ERK cascade. J. Biol. Chem. 283:36636–36645. 10.1074/jbc.M804633200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Noh D, Ahn S, Lee R, Park I, Kim J, Suh P, Ryu S, Lee K, Han J. 2000. Overexpression of phospholipase D1 in human breast cancer tissues. Cancer Lett. 161:207–214. 10.1016/S0304-3835(00)00612-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Uchida N, Okamura S, Kuwano H. 1999. Phospholipase D activity in human gastric carcinoma. Anticancer Res. 19:671–675 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yamada Y, Hamajima N, Kato T, Iwata H, Yamamura Y, Shinoda M, Suyama M, Mitsudomi T, Tajima K, Kusakabe S, Yoshida H, Banno Y, Akao Y, Tanaka M, Nozawa Y. 2003. Association of a polymorphism of the phospholipase D2 gene with the prevalence of colorectal cancer. J. Mol. Med. 81:126–131. 10.1007/s00109-002-0411-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zhao Y, Ehara H, Akao Y, Shamoto M, Nakagawa Y, Banno Y, Deguchi T, Ohishi N, Yagi K, Nozawa Y. 2000. Increased activity and intranuclear expression of phospholipase D2 in human renal cancer. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 278:140–143. 10.1006/bbrc.2000.3719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Buchanan FG, McReynolds M, Couvillon A, Kam Y, Holla VR, Dubois RN, Exton JH. 2005. Requirement of phospholipase D1 activity in H-RasV12-induced transformation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102:1638–1642. 10.1073/pnas.0406698102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Saito M, Iwadate M, Higashimoto M, Ono K, Takebayashi Y, Takenoshita S. 2007. Expression of phospholipase D2 in human colorectal carcinoma. Oncol. Rep. 18:1329–1334 http://www.spandidos-publications.com/or/18/5/1329/download. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zheng Y, Rodrik V, Toschi A, Shi M, Hui L, Shen Y, Foster DA. 2006. Phospholipase D couples survival and migration signals in stress response of human cancer cells. J. Biol. Chem. 281:15862–15868. 10.1074/jbc.M600660200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Iorio E, Mezzanzanica D, Alberti P, Spadaro F, Ramoni C, D'Ascenzo S, Millimaggi D, Pavan A, Dolo V, Canevari S, Podo F. 2005. Alterations of choline phospholipid metabolism in ovarian tumor progression. Cancer Res. 65:9369–9376. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Gadir N, Lee E, Garcia A, Toschi A, Foster DA. 2007. Suppression of TGF-beta signaling by phospholipase D. Cell Cycle 6:2840–2845. 10.4161/cc.6.22.4921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Shi M, Zheng Y, Garcia A, Xu L, Foster DA. 2007. Phospholipase D provides a survival signal in human cancer cells with activated H-Ras or K-Ras. Cancer Lett. 258:268–275. 10.1016/j.canlet.2007.09.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Chen Y, Zheng Y, Foster DA. 2003. Phospholipase D confers rapamycin resistance in human breast cancer cells. Oncogene 22:3937–3942. 10.1038/sj.onc.1206565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Fiucci G, Czarny M, Lavie Y, Zhao D, Berse B, Blusztajn JK, Liscovitch M. 2000. Changes in phospholipase D isoform activity and expression in multidrug-resistant human cancer cells. Int. J. Cancer 85:882–888 http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(20000315)85:6%3C882::AID-IJC24%3E3.0.CO;2-E/full [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wood LD, Parsons DW, Jones S, Lin J, Sjoblom T, Leary RJ, Shen D, Boca SM, Barber T, Ptak J, Silliman N, Szabo S, Dezso Z, Ustyanksky V, Nikolskaya T, Nikolsky Y, Karchin R, Wilson PA, Kaminker JS, Zhang Z, Croshaw R, Willis J, Dawson D, Shipitsin M, Willson JK, Sukumar S, Polyak K, Park BH, Pethiyagoda CL, Pant PV, Ballinger DG, Sparks AB, Hartigan J, Smith DR, Suh E, Papadopoulos N, Buckhaults P, Markowitz SD, Parmigiani G, Kinzler KW, Velculescu VE, Vogelstein B. 2007. The genomic landscapes of human breast and colorectal cancers. Science 318:1108–1113. 10.1126/science.1145720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Foster DA. 2009. Phosphatidic acid signaling to mTOR: signals for the survival of human cancer cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1791:949–955. 10.1016/j.bbalip.2009.02.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Rudge SA, Wakelam MJ. 2009. Inter-regulatory dynamics of phospholipase D and the actin cytoskeleton. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1791:856–861. 10.1016/j.bbalip.2009.04.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]