Abstract

The platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) receptors (PDGFRs) are central to a spectrum of human diseases. When PDGFRs are activated by PDGF, reactive oxygen species (ROS) and Src family kinases (SFKs) act downstream of PDGFRs to enhance PDGF-mediated tyrosine phosphorylation of various signaling intermediates. In contrast to these firmly established principles of signal transduction, much less is known regarding the recently appreciated ability of ROS and SFKs to indirectly and chronically activate monomeric PDGF receptor α (PDGFRα) in the setting of a blinding condition called proliferative vitreoretinopathy (PVR). In this context, we made a series of discoveries that substantially expands our appreciation of epigenetic-based mechanisms to chronically activate PDGFRα. Vitreous, which contains growth factors outside the PDGF family but little or no PDGFs, promoted formation of a unique SFK-PDGFRα complex that was dependent on SFK-mediated phosphorylation of PDGFRα and activated the receptor's kinase activity. While vitreous engaged a total of five receptor tyrosine kinases, PDGFRα was the only one that was activated persistently (at least 16 h). Prolonged activation of PDGFRα involved mTOR-mediated inhibition of autophagy and accumulation of mitochondrial ROS. These findings reveal that growth factor-containing biological fluids, such as vitreous, are able to tirelessly activate PDGFRα by engaging a ROS-mediated, self-perpetuating loop.

INTRODUCTION

Deregulation of receptors for platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) contributes to a variety of human pathologies. For instance, genetic lesions that result in point mutation or chromosomal translocation, which constitutively activate the intrinsic tyrosine kinase activity of the PDGF receptor (PDGFR), are tightly associated with gastrointestinal tumors (1, 2), myeloid disorders, and leukemias (3).

In addition to the above-mentioned diseases in which deregulation of PDGFR activity involves a genetic change, there is a growing appreciation that epigenetic-based mechanisms to activate PDGFRs both exist and drive pathology. Antibodies that activate PDGFRs are present in sera of patients with scleroderma and are implicated in facilitating the fibrotic component of this pathology (4). Growth factors outside the PDGF family (PDGFs) are present in vitreous (the viscous fluid that fills the space between the lens and retina) from patients with proliferative vitreoretinopathy (PVR) and trigger indirect activation of PDGF receptor α (PDGFRα), which is a key event in the pathogenesis of this fibroproliferative disease in animal models (5).

A recurring mediator of PDGFR-associated pathology is reactive oxygen species (ROS). PDGF-mediated activation of PDGFR results in activation of NADPH oxidases (Noxs), which increase the level of ROS (6–8). Under these conditions, the ROS effectors are protein tyrosine phosphatases (PTPs), which are inactivated by ROS (9). Such a lull in PTP activity favors accumulation of tyrosine-phosphorylated proteins that drive a variety of signaling events (10). This ROS-mediated boost in signaling is short-lived, at least in part due to enzymes such as peroxiredoxins (Prxs), which eliminate certain ROS species (11). The importance of regulating this plasma membrane-localized source of ROS is illustrated by exacerbated restenosis of the carotid artery in mice that lack Prx II (12).

In addition to acting downstream of PDGFR, ROS can also act upstream of it to promote the indirect mode of activating the PDGFRs mentioned above (13). Under these circumstances, the ROS effectors are Src family kinases (SFKs), which are activated by ROS (14–16) and promote autophosphorylation of monomeric PDGFRs (13, 17, 18). Thus, ROS can act either upstream or downstream of PDGFRs, and it does so by governing the activity of distinct types of signaling enzymes.

The cellular source of ROS that drives the indirect mode of activating PDGFR is unknown. Noxs are likely to be only a partial contributor, because the duration of activation of PDGFR engaged by the indirect mode persists well beyond the time frame of the Nox-mediated rise in ROS (12, 17, 19). A second and potentially enduring source of ROS is the electron transport chain within the mitochondria. This source of ROS is regulated by factors such as the cell's metabolic state. This parameter could be profoundly influenced by vitreous, because it contains a vast array of growth factors (non-PDGFs), which activate mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) and thereby suppress autophagy. This would reduce clearance of organelles, including mitochondria, and thereby result in prolonged elevation of ROS (20). Thus, vitreous is likely to increase mitochondrial ROS and thereby set the stage for enduring activation of PDGFR, which occurs in vitreous-stimulated cells (17).

The concept that SFKs act upstream of indirectly activated PDGFRα complements the well-established role of this class of signaling enzymes downstream of directly activated PDGFR. PDGF assembles PDGFRs into dimers and thereby promotes autophosphorylation of many tyrosine residues that either enhance the receptor's kinase activity or enable stable association with Src homology 2 (SH2) domain-containing signaling enzymes (21, 22). For instance, PDGF stimulates autophosphorylation of PDGFRα at Tyr 572 and 574 within the juxtamembrane domain, and this event allows stable association with SFKs (23, 24). Engaging the SH2 domain of SFKs activates its kinase (25), and SFKs contribute to the PDGF-induced rise in phosphotyrosine content of a variety of proteins (26). Thus, SFKs act either upstream or downstream of PDGFRs, depending on whether PDGFRα is activated indirectly or directly.

The goal of this study was to determine the mechanism by which vitreous, which is a rich source of non-PDGFs that activate PDGFRα indirectly, results in enduring activation of PDGFRα. Our results revealed the existence of a ROS-driven, self-perpetuating mechanism that was responsible for persistent activation of PDGFRα in cells exposed to vitreous.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Major reagents.

Antibodies against Akt, phosphorylated Akt (phospho-Akt [p-Akt]) S473, mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), phosphorylated mTOR (p-mTOR) (S2448), p70 S6 kinase (S6K), p-S6K (T389), Src, p-Src, insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor (IGF-1R), regulatory-associated protein of mTOR (Raptor), and autophagy 5 (Atg5) were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA). The antiphosphotyrosine antibody pY20 was from BD Transduction Laboratories (San Jose, CA), and human recombinant PDGF-A, epidermal growth factor (EGF), and insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) were from PeproTech Inc. (Rocky Hill, NJ). The horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG, goat anti-mouse IgG secondary antibodies, and antibodies against EGFR and p-PDGFRα (phospho-Y754) were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Enhanced chemiluminescent substrate for detection of HRP was from Pierce Protein Research Products (Rockford, IL). The anti-PDGFRα (27P) and Ras GTPase-activating protein (RasGAP) antibodies were produced and characterized as previously described (27). The phospho-Y742 PDGFRα antibody was raised against phosphopeptide KQADTTQY(phospho-Y742)VPMLDMK, which was synthesized by Tufts Medical School (Boston, MA) (17). Rabbits were immunized with this peptide by Alpha Diagnostic International Inc. (San Antonio, TX) by using the standard immunization procedure. Thirty percent H2O2, 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA), antimycin A, N-acetyl cysteine (NAC), diphenyleneiodonium chloride (DPI), and tetrahydrocanicabinol (THC) were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). SU6656 (C19H21N3O3S) was from Calbiochem (Billerica, MA).

Cell culture.

A spontaneously arising human retinal pigment epithelial cell line (ARPE19) was purchased from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA), and ARPE19α cells were ARPE19 cells that overexpressed human PDGFRα as previously described (28). Both ARPE19 and ARPE19α cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (DMEM) (45%) plus F-12 (45%) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). Primary human retinal pigment epithelial (RPE) cells from Lonza (Walkersville, MD) were cultured in the media of endothelial cell growth medium RtEGM BulletKit from Lonza.

F cells were generated as previously described (29). Briefly, F cells were mouse embryo fibroblasts derived from mice null for both pdgfr genes and then immortalized with simian virus 40 (SV40) T antigen. Fα cells were F cells that reexpressed human PDGFRα. F2 cells were F cells that reexpressed human mutant PDGFRα Y572F/Y574F, and R627 cells were F cells that reexpressed human mutant PDGFRα K627R as described previously (17). Primary human corneal fibroblasts (HCF) were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS.

GPG293 cells (30) were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 2 mM l-glutamine, 1 μg/ml tetracycline (Sigma), 2 μg/ml puromycin (Sigma), 0.3 mg/ml G418 (Sigma), and 16.7 mM HEPES (Invitrogen). The medium used during virus collection was DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 2 mM l-glutamine, and 16.7 mM HEPES. All the above cells were cultured at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere.

Phospho-RTK array.

Lysates of ARPE19α and primary RPE cells were subjected to a phospho-receptor tyrosine kinase (phospho-RTK) array (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) following the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, 1 mg of lysate prepared from cells treated with normal rabbit vitreous (RV) for 10 min, 2 h, and 16 h was incubated with the membranes at 4°C overnight with gentle shaking. The membrane was washed and then exposed to an antiphosphotyrosine antibody conjugated to HRP. Signals were detected by chemiluminescence.

Immunoprecipitation and Western blotting.

F, F2, Fα, and R627 cells were grown to 90% confluence and then incubated for 24 h in DMEM. The cells were exposed to the desired agents and then washed twice with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The cells were lysed in extraction buffer (EB buffer) (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.4], 5 mM EDTA, 50 mM NaCl, 50 mM NaF, 1% Triton X-100, 20 μg/ml aprotinin, 2 mM Na3VO4, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride), and the insoluble material was removed by centrifugation for 15 min at 13,000 × g at 4°C. Src was immunoprecipitated from clarified lysates as previously described using an anti-c-Src antibody. The immunoprecipitated proteins were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE, transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes, and then subjected to Western blot analysis using the antibodies indicated in the figures. At least three independent experiments were performed. Signal intensity was determined by densitometry using Quantity One software (Bio-Rad).

Suppression of Raptor and Atg5 expression by short hairpin RNA (shRNA).

An oligonucleotide (CCTTTCATTCAGAAGCTGTTT) corresponding to Atg5 cDNA nucleotides 915 to 925 (NM_004849, construct TRCN0000151474) and an oligonucleotide (CGAGTCCTCTTTCACTACAAT) corresponding to Raptor cDNA nucleotides 1238 to 1258 (NM_020761.2, TRCN0000332886), or a control oligonucleotide (ACAACAGCCACAACGTCTATA) corresponding to green fluorescent protein (GFP) nucleotides 437 to 457 (TRCN0000072181) in a hairpin-pLKO.1 retroviral vector, the packaging plasmid (pCMV-dR8.91 [CMV stands for cytomegalovirus]), the envelope plasmid (VSV-G/pMD2.G [VSV stands for vesicular stomatitis virus]), and 293T packaging cells were from Dana-Farber Cancer Institute/Harvard Medical School (Boston, MA).

To prepare GFP, Raptor, and Atg5 shRNA lentivirus, a mixture of packaging plasmid (0.9 μg), envelope plasmid (0.1 μg), hairpin-pLKO.1 vector (1 μg) (or a hairpin-pLKO.1 containing GFP, Raptor, or Atg5 shRNA oligonucleotide), and TransIT-LT1 were mixed and incubated at room temperature for 30 min. The transfection mixture was transferred to 293T cells that were approximately 70% confluent. After 18 h, the medium was replaced with growth medium modified to contain 30% serum, and virus was harvested 40 h after transfection. The viral harvest was repeated at 24-h intervals 3 times. The virus-containing media were pooled and centrifuged at 800 × g for 5 min, and the supernatant was used to infect ARPE19α cells. Successfully infected cells were selected on the basis of their ability to proliferate in media containing puromycin (1 μg/ml). The resulting cells were characterized by Western blotting using an antibody against Raptor or Atg5.

Dichlorofluorescein assay.

The level of intracellular H2O2 was determined by measuring the fluorescence of cells loaded with 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein diacetate as described previously (13). Briefly, cells were rinsed twice with Krebs-Ringer solution and incubated in Krebs-Ringer solution containing DCFH-DA (5 μM). DCFH-DA is nonpolar and readily diffuses into cells, where it is hydrolyzed to the nonfluorescent polar derivative DCFH, which cannot cross the cell membrane. In the presence of H2O2, DCFH is oxidized to the highly fluorescent 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein (DCF). Culture dishes were sealed with paraffin film and placed in a CO2 incubator at 37°C for 5 min, after which time they were rinsed three times with PBS and then the fluorescence was read with a Bio-Tek fluorescence plate reader at excitation and emission wavelengths of 485 and 528 nm, respectively.

Mitochondrion-localized redox-sensitive GFP mutant (Mito-RoGFP).

The mitochondrion-localized redox-sensitive GFP mutant (Mito-RoGFP) has been described previously (31). It contains two engineered cysteine thiols that were generated by introducing the following 4 point mutations in EGFP: C48S, Q80R, S147C, and Q204C. Localization to the mitochondria was achieved by appending a 48-bp region encoding the mitochondrial targeting sequence from cytochrome oxidase subunit IV to the 5′ end of the coding sequence. To stably express Mito-RoGFP in ARPE19α cells, the Mito-RoGFP cDNA was first subcloned as a KpnI-NotI fragment into a bacterial cloning vector (pVZ) that had also been digested with the pair of restriction enzymes. The Mito-RoGFP cDNA was moved from pVZ as a SalI-NotI fragment into a retroviral vector (pLNCX3) that was digested with the same pair of restriction enzymes. The resulting construct was transfected into 293GPG cells to obtain retrovirus, which was used to infect ARPE19α cells as previously described (32).

The ARPE19α cells that expressed Mito-RoGFP were selected in G418 (2 mg/ml) and then treated with dithiothreitol (DTT) (10 mM) or H2O2 (1 mM) for 1 h or RV for 10 min or 16 h. The treated cells were observed using a confocal microscope and photographed at excitation wavelengths of 408 and 490 nm and an emission wavelength of 525 nm. There were 5 photographs for each treatment, and the experiment was repeated three times. The pixel density of each photograph was quantitated.

Acid washing.

Acid washing to remove growth factors was performed as previously described (33). Briefly, serum-starved ARPE19α cells were treated with either PDGF-A (50 ng/ml) or RV (1: 2 dilution) for 10 min and washed twice with acid wash buffer (50 mM glycine [pH 2.8], 150 mM NaCl, 1 mg/ml polyvinylpyrrolidone). The cells were then washed once with PBS and cultured in starvation media for an additional 10 min or 16 h.

Kinase assay.

Serum-deprived cells (F, Fα, and F2) were treated with PDGF-A (10 ng/ml) or RV for 10 min and then lysed in EB buffer. PDGFRα was immunoprecipitated from clarified lysates with an antibody against PDGFRα (27P). The kinase activity of immunoprecipitated PDGFRα was assessed by its ability to phosphorylate 1 μg of a glutathione S-transferase (GST)–phospholipase Cγ (PLCγ) fusion protein that was previously described (34). In addition to the PDGFRα immunoprecipitate and GST-PLCγ fusion protein, 20 mM piperazine-N,N′-bis(2-ethanesulfonic acid) (PIPES) (pH 7.0), 10 mM MnCl2, 10 μM ATP, and 20 μg/ml aprotinin were included in the assay. The reactions were permitted to proceed for 10 min at 30°C, and they were stopped by adding 2× sample buffer (58). The extent of phosphorylation was determined by phosphotyrosine Western blot analysis.

Statistical analysis.

Data from three independent experiments were analyzed using the unpaired t test. P values of less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Vitreous promoted the formation of an SFK-PDGFRα complex that was required for activation of PDGFRα.

SFKs act downstream of PDGFRα that is activated by PDGF. Under these conditions, PDGF assembles receptor dimers, triggers autophosphorylation at many sites, including the pair of sites (Y572 and Y574) located in the juxtamembrane (JM) domain that are a key element of the docking site for the SH2 domains of SFKs (23, 24, 35, 36).

In cells exposed to non-PDGFs, SFKs act upstream of PDGFRα wherein they are essential for activating PDGFRα monomers (13, 17). The realization that SFKs act both upstream and downstream of PDGFRα suggested that the canonical PDGFRα-SFK relationship does not encompass the full spectrum of how these two signaling enzymes interact. In the studies described below, we investigated the nature of the SFK-PDGFRα relationship and its importance for signaling by the indirectly activated PDGFRα.

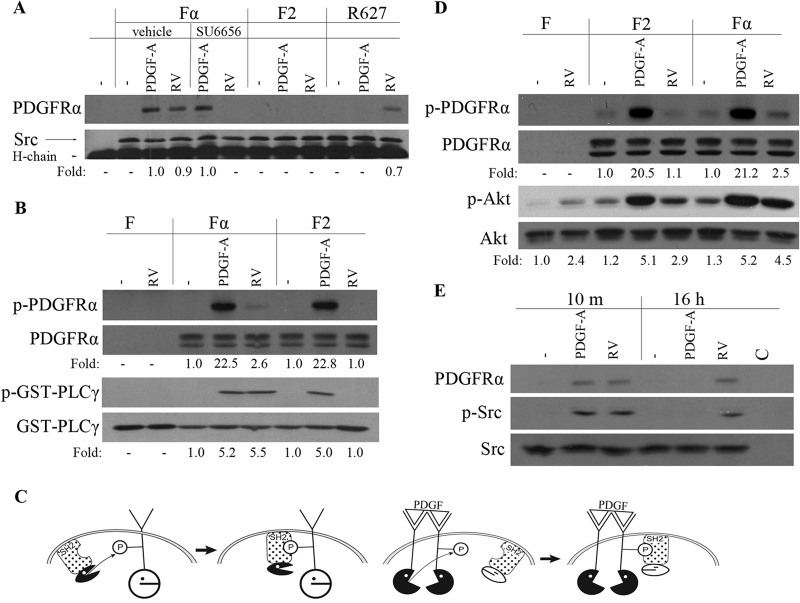

The first step in this series was to test whether vitreous (RV), which contains many non-PDGFs but only very low levels of PDGFs (37, 38), promoted association between SFKs and PDGFRα. As shown in Fig. 1A, it did; PDGFRα coprecipitated with SFKs from vitreous-stimulated cells but not from unstimulated cells. Furthermore, this complex was not detected in vitreous-stimulated cells expressing the F2 mutant, which has Phe in place of Tyr at residues 572 and 574 (Fig. 1A). These findings indicate that vitreous promoted association of SFKs and PDGFRα and that this complex was dependent on the JM tyrosine phosphorylation sites.

FIG 1.

RV induced a unique SFK-PDGFRα relationship, which was required for activation of PDGFRα and downstream signaling events. (A) Near-confluent, serum-starved Fα, F2, and R627 (a kinase inactive point mutant [74]) cells were stimulated with PDGF-A (50 ng/ml) or normal rabbit vitreous (RV) for 10 min. Where indicated, the cells were pretreated with vehicle or SU6656 for 30 min. The cells were lysed, the lysates were immunoprecipitated with an anti-Src antibody, and the resulting samples were subjected to Western blotting using an anti-PDGFRα antibody (27P) and an anti-Src antibody. The fold values are the PDGFRα/Src ratio or the p-Akt/Akt ratio. The position of the 50-kDa heavy chain of the immunoprecipitating antibody (H-chain) is indicated. The data presented are representative of three independent experiments. (B) Serum-deprived F, Fα, and F2 cells were treated with PDGF-A (50 ng/ml) or RV for 10 min and lysed, and PDGFRα was then immunoprecipitated with an anti-PDGFRα antibody (27P). The immunoprecipitates were subjected to an in vitro kinase assay in which the substrate was a GST-PLCγ fusion protein. The extent of phosphorylation was monitored by Western blotting using an antiphosphotyrosine antibody (pY20). The membranes were stripped and reprobed with antibodies against PDGFRα or GST. The experimental results presented are representative of three independent experiments. p-PDGFRα, phosphorylated PDGFRα. (C) (Left) SFKs act upstream of PDGFR; ROS-activated SFKs phosphorylate monomeric PDGFRα and subsequently associate with it. The kinase activity of SFKs is required for the formation of the complex. (Right) SFKs act downstream of PDGFR; PDGF dimerizes PDGFRs and thereby triggers autophosphorylation that enables stable association of SFKs. The kinase activity of PDGFRα is required for formation of the complex. P, phosphate group. (D) Serum-starved F, F2, and Fα cells were stimulated with PDGF-A (50 ng/ml) or RV for 10 min. Their lysates were subjected to Western blot analysis using the following antibodies: anti-PDGFRα pY742 for p-PDGFRα and anti-Akt pS473 for p-Akt. The fold values are the p-PDGFRα/PDGFRα ratio or the p-Akt/Akt ratio. The data presented are representative of three independent experiments. F cells express no PDGFRs. (E) Serum-deprived Fα cells were treated with PDGF-A (50 ng/ml) or RV for 10 min (10 m) or 16 h and lysed, and the resulting lysates were immunoprecipitated with an anti-Src antibody (mouse origin) or a nonimmune IgG as a control (C). The resulting immunoprecipitates were subjected to Western blot analysis using antibodies against phospho-Src or PDGFRα. The membrane was reprobed with an anti-Src antibody. The data presented are representative of three experiments.

Given that the substrate preferences of PDGFRα and SFKs are similar, we established which kinase was required for the SFK-PDGFRα complex that formed in vitreous-stimulated cells. Blocking SFK activity prevented recovery of the SFK-PDGFRα complex from vitreous-stimulated cells, whereas this complex still formed with a kinase inactive receptor mutant (Fig. 1A). We conclude that only the kinase activity of SFKs was required for the association between SFKs and PDGFRα in response to vitreous.

To test whether vitreous also activated the kinase activity of PDGFRα, we exposed cells to vitreous, immunoprecipitated PDGFRα, and monitored its ability to phosphorylate an exogenous substrate. As shown in Fig. 1B, vitreous increased the ability of PDGFRα to phosphorylate GST-PLCγ, one of the substrates that PDGFRα phosphorylates in an in vitro setting (39). Vitreous-mediated activation of PDGFRα was not observed for the F2 mutant (Fig. 1B). Thus, vitreous stimulated the kinase activity of monomeric PDGFRα, and this event was dependent on two tyrosine phosphorylation sites within the JM domain.

The left-hand panel of Fig. 1C summarizes the key principles gleaned from this series of studies. In vitreous-stimulated cells, SFKs phosphorylate PDGFRα and then associate with it. This event proceeds independently of the PDGFR's kinase activity. This previously unappreciated mechanism for association of SFKs with PDGFRα constitutes a typical relationship of an SH2 domain-containing kinase and its substrate; the kinase first phosphorylates the substrate and then associates with it because the peptide sequence preferred by the kinase matches the peptide sequence preferred by the SH2 domain (40). The sequence surrounding the two JM domain tyrosine residues of PDGFRα is optimal for both Src's kinase and its SH2 domain (41, 42). A plausible reason that vitreous also activates the kinase activity of PDGFRα is because phosphorylation of the JM tyrosines and/or binding of SFKs overcomes the inhibitory influence of the JM domain on the receptor's kinase activity (43).

This sequence of events, which occurs when PDGFRα is activated indirectly, is distinct from what proceeds in response to PDGF, which activates PDGFRα directly. While in both cases a complex assembles between SFKs and PDGFRα, PDGF stimulates the receptor's kinase activity, which results in autophosphorylation of the JM tyrosines that permits subsequent association of SFKs (right-hand panel of Fig. 1C). The kinase activity of SFKs is dispensable in this scenario (Fig. 1A). Thus, while PDGFRα and SFKs associate regardless of the type of agonist, the kinase that is required for the association is agonist dependent; SFKs appear to phosphorylate PDGFRα in vitreous-stimulated cells, whereas receptor autophosphorylation is the essential event in PDGF-stimulated cells.

Formation of the SFK-PDGFRα complex was required to mediate downstream signaling events.

To investigate the importance of the SFK-PDGFRα complex for downstream signaling events, we focused on vitreous-stimulated activation of Akt. Compared with cells expressing wild-type (WT) PDGFRα, vitreous-induced activation of Akt was substantially lower in F2 cells (Fig. 1D). In contrast, the magnitudes of Akt activation were similar in both cell lines exposed to PDGF (Fig. 1D). These results indicate that formation of the SFK-PDGFRα complex was more important for activating Akt in response to vitreous than was PDGF. This conclusion is consistent with a previous report that many PDGF-stimulated signaling events were unimpaired by genetic ablation of SFKs (44).

While vitreous-mediated activation of Akt in F2 cells was reduced compared to cells expressing WT PDGFRα, it was still clearly above the unstimulated level (Fig. 1D). This is because vitreous contains many growth factors (38), which presumably act via RTKs that are typically expressed by fibroblasts. Vitreous activated Akt in F cells (Fig. 1D), which contain no PDGFRs (29).

To investigate whether RV stimulated prolonged activation of SFK and association with PDGFRα, we assessed these parameters at both the 10-min and 16-h time points. As shown in Fig. 1E, RV induced enduring activation of SFKs and association with PDGFRα. In contrast, these events were short-lived in PDGF-stimulated cells (Fig. 1E).

The mechanism by which vitreous and non-PDGFs activated SFKs is by increasing the level of ROS (13). The fact that PDGF elevates ROS (just like many other ligands for RTKs) (19) begs the question of why PDGF failed to also induce the SFK-PDGFRα relationship observed in vitreous-stimulated cells. The answer emerged in our recently published studies revealing that dimerized receptors are poor substrates for ROS-activated SFKs (18). Thus, once PDGFRs are dimerized by PDGF, they are unable to engage in the SFK-PDGFRα relationship (left-hand panel of Fig. 1C), even though ROS accumulates and presumably activates SFKs in PDGF-stimulated cells (12, 19, 24).

In summary, these studies reveal that there are multiple kinases capable of phosphorylating tyrosine residues with the JM domain of PDGFRα and thereby triggering association with SFKs. This event is essential for activating signaling events, such as Akt in the indirect setting, whereas it is dispensable when PDGFRα is activated directly. We conclude that both the nature of the relationship between PDGFRα and SFKs and the consequences are unique to the mode by which PDGFRα is activated.

PDGFRα was the only RTK that was activated persistently in response to vitreous.

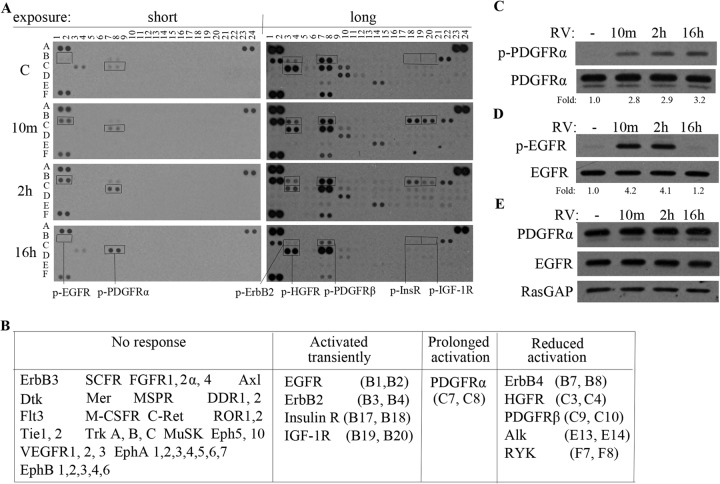

PVR develops at least in part because of a break in the retina that exposes the underlying retinal pigment epithelial (RPE) cells to vitreous (45). While vitreous contains a cornucopia of growth factors and cytokines and RPE cells express receptors for many of them, PDGFRα appears central to PVR pathogenesis (29). To begin to address the underlying basis of this phenomenon, we considered the spectrum and kinetics of RTK activation in RPE cells exposed to vitreous.

As expected, receptors for growth factors present in vitreous (such as fibroblast growth factor and IGF-1 [38]) were among the RTKs activated in response to vitreous (Fig. 2A and B). Activation of these RTKs was acute and transient, which reflects the fact that ligands for RTKs often not only activate them but also promote their internalization and degradation, thereby terminating their output (46). A ligand-induced decline in RTKs was not obvious under these experimental conditions, which did not inhibit the ongoing synthesis of RTKs. When this type of experiment is done in the presence of cycloheximide, a ligand-induced decline is readily apparent (17). Vitreous also activated PDGFRα, but the kinetics were unusual; phosphorylation increased gradually and persisted to the 16-h time point; at this time point, activation of all other vitreous-stimulated RTKs had subsided (Fig. 2A and B). This same phenomenon was observed when lysates from vitreous-stimulated cells were analyzed by immunoprecipitation/Western blotting instead of phospho-RTK array (Fig. 2C and D). The results of this analysis indicate that the kinetics of PDGFRα activation was persistent, which contrasted with the transient activation of four other RTKs.

FIG 2.

PDGFRα was the only RTK that was activated persistently in response to RV. (A) ARPE19α cells were cultured in medium containing 10% FBS until reaching 90% confluence and then starved in serum-free medium overnight. The cells were stimulated with vitreous from healthy rabbits (which contains low or undetectable levels of active PDGFs [37, 38]) for 10 min or 2 or 16 h. The lysates were subjected to a phospho-RTK array following the manufacturer's instructions. Short and long exposures are presented. C, control; p-HGFR, phosphorylated hepatocyte growth factor receptor; p-InsR, phosphorylated insulin receptor. (B) Summary of the results for all RTKs that were assayed. VEGFR1, vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 1; SCFR, stem cell growth factor receptor; M-CSFR, macrophage colony-stimulating factor receptor; FGFR1, fibroblast growth factor receptor 1; MSPR, macrophage-stimulating factor receptor; MuSK, muscle-specific kinase; DDR1, discoidin domain receptor kinase 1; ROR1, RTK-like orphan receptor 1; Insulin R, insulin receptor; HGFR, hepatocyte growth factor receptor; PYK, proline-rich tyrosine kinase. Coordinates in parentheses refer to the blot in panel A. (C and D) Lysates from cells treated as described above for panel A were immunoprecipitated with the indicated antibody and then subjected to Western blot analysis with an antibody recognizing the RTK (bottom blot) or antiphosphotyrosine (top blot). The fold values are the p-PDGFRα/PDGFRα ratio or the p-EGFR/EGFR ratio. The data presented are representative of three independent experiments. RV, rabbit vitreous. (E) Lysates from cells treated as described above for panel A were subjected to Western blotting using the indicated antibodies. RasGAP was included as a loading control.

Unmitigated activation of RTKs is one of the mechanisms that underlie pathology. For instance, a constitutively activated PDGFRα point mutant (D842V) is present in patients with gastrointestinal stromal tumors (1). Replacing one of the WT alleles of PDGFRα with the D842V mutant results in widespread organ fibrosis in adult mice (47). Since fibrosis is a quintessential feature of PVR pathogenesis, we sought to investigate the underlying mechanism by which vitreous activated PDGFRα persistently.

Several possibilities that we considered turned out to be poor explanations for how vitreous induced prolonged activation of PDGFRα. For instance, it did not seem to be due to vitreous-mediated increased expression of PDGFRα (Fig. 2E) or because vitreous promoted secretion of PDGF and thereby established an autocrine loop, since neutralizing PDGFs had no effect on this phenomenon (data not shown). Furthermore, it did not depend on overexpression of PDGFRα (which was the case for the RPE cells used in Fig. 2), because vitreous induced persistent activation of PDGFRα in unmanipulated primary RPE cells (data not shown).

A more productive line of inquiry focused on the mechanism by which vitreous activated PDGFRα. Vitreous from healthy rabbits contains very little PDGF (37, 38); it activates PDGFRα via non-PDGFs, which are growth factors outside the PDGF family such as basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF), insulin, hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), and epidermal growth factor (EGF) (5, 13). Non-PDGFs bind to their own receptors, increase the level of ROS, and activate SFKs, which promote activation of monomeric PDGFRα (13, 18). Importantly, this indirect, intracellular mode of activating PDGFRα does not prompt its internalization and degradation; consequently, vitreous-activated PDGFRs are long-lived (17, 18).

However, this explanation seems incomplete because PDGFRα remained activated well beyond the time frame that RTKs elevate ROS and activate SFKs (19, 24). While the established requirement for ROS and SFKs to indirectly activate PDGFRα provides a plausible explanation for the early activation of PDGFRα in response to vitreous, an additional mechanism seemed responsible for maintaining PDGFRα activity once non-PDGF-mediated elevation of ROS and activation of SFKs subsided. What is responsible for activating PDGFRα when all of the other vitreous-activated RTKs have returned to baseline? The search for an answer to this question led us to consider whether an alternative and enduring source of ROS was driving prolonged activation of PDGFRα.

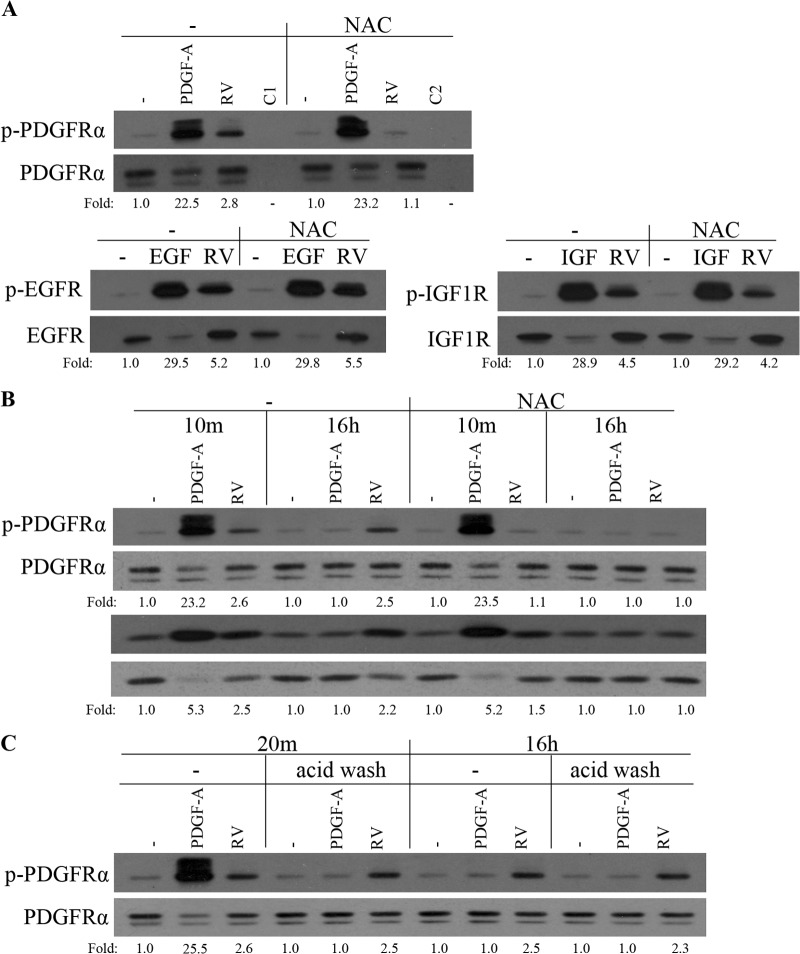

Vitreous-driven activation of PDGFRα was selective, prolonged, and dependent on ROS.

To begin to test whether vitreous-driven activation of PDGFRα was both selective and ROS dependent, we acutely stimulated cells with vitreous or ligands for specific RTKs (PDGF-A, EGF, and IGF-1), immunoprecipitated the corresponding RTK, and evaluated the extent of tyrosine phosphorylation. As shown in Fig. 3A, vitreous increased tyrosine phosphorylation of all three RTKs. Repeating the experiment in the presence of N-acetyl cysteine (NAC) revealed that vitreous-dependent phosphorylation of PDGFRα was largely eliminated, whereas phosphorylation of the other RTKs was unaffected (Fig. 3A). Ligand-mediated tyrosine phosphorylation of RTKs was insensitive to NAC in all cases (Fig. 3A). These results indicate that only phosphorylation of PDGFRα was dependent on ROS in vitreous-stimulated cells, whereas the other two RTKs were not. Similar results were observed when these experiments were repeated with primary human corneal fibroblasts, instead of ARPE19α cells, which were used for the experiments shown in Fig. 3A (data not shown).

FIG 3.

Vitreous-driven activation of PDGFRα was selective, prolonged, and dependent on ROS. (A) Serum-starved ARPE19α cells were pretreated with NAC (10 mM) for 30 min and then stimulated with buffer (−), with PDGF-A, EGF, or IGF-1 (IGF) (each at 50 ng/ml), or with RV for 10 min. The lanes designated C1 and C2 were stimulated with buffer and RV, respectively. The cells were lysed, and the resulting lysates were immunoprecipitated using antibodies against PDGFRα, EGFR, IGF-1R, or nonimmune IgG (C1 and C2). The resulting immunoprecipitates were subjected to Western blot analysis using an antiphosphotyrosine antibody (pY20). The membranes were reprobed with antibodies against PDGFRα, EGFR, or IGF-1R. The fold values are the p-PDGFRα/PDGFRα ratio, the p-EGFR/EGFR ratio, or the p-IGF-1R/IGF-1R ratio. The data are representative of three experiments; similar results were obtained when the experiment was repeated with primary human corneal fibroblasts instead of ARPE19α cells (data not shown). (B) Serum-deprived ARPE19α cells were pretreated with NAC (10 mM) for 30 min before stimulation with PDGF-A (50 ng/ml) or RV for 10 min. For the 16-h stimulation with PDGF-A or RV, the 30-min NAC (10 mM) treatment was from 15.5 to 16 h. Following stimulation, the cells were lysed and subjected to Western blotting using the indicated antibodies. The fold values are the p-PDGFRα/PDGFRα ratio or the p-Akt/Akt ratio. The blots presented are representative of three experiments. (C) Serum-starved ARPE19α cells were treated with PDGF-A (50 ng/ml) or RV for 10 min, acid washed (to remove the growth factors), and harvested either at 10 min or at 15 h and 50 min later. The lysates were subjected to Western blot analysis using a phospho-PDGFRα Y754 antibody. The membrane was reprobed with a PDGFRα antibody (27P). The fold values are the p-PDGFRα/PDGFRα ratio. The data presented are representative of three experiments.

We previously reported that acute, vitreous-stimulated phosphorylation of PDGFRα was dependent on ROS (13). The experimental results shown in Fig. 3B indicated that the same was true for prolonged activation of both PDGFRα and Akt.

To further characterize the nature of prolonged activation of PDGFRα in vitreous-stimulated cells, we considered whether it required continuous exposure to vitreous. To this end, cells were exposed to vitreous for 10 min, vitreous was removed by a previously established acid wash procedure (33), and the cells were harvested 10 min later (“20m” in Fig. 3C) or 15 h and 50 min later (“16h” in Fig. 3C). The abrupt and profound decline in PDGF-mediated PDGFRα phosphorylation was expected in light of the efficacy of the acid wash and the short half-life of PDGF-activated PDGFRα (33, 48). Removing the vitreous had no effect on the extent of PDGFRα phosphorylation (Fig. 3C), which indicates that enduring phosphorylation of PDGFRα is not dependent on continuing exposure to vitreous. Taken together, these results indicate that vitreous-mediated activation of PDGFRα was selective, prolonged, dependent on ROS, and self-perpetuating.

Vitreous stimulated mTOR complex 1 (mTORC1)-dependent elevation of ROS, which was required for persistent activation of PDGFRα.

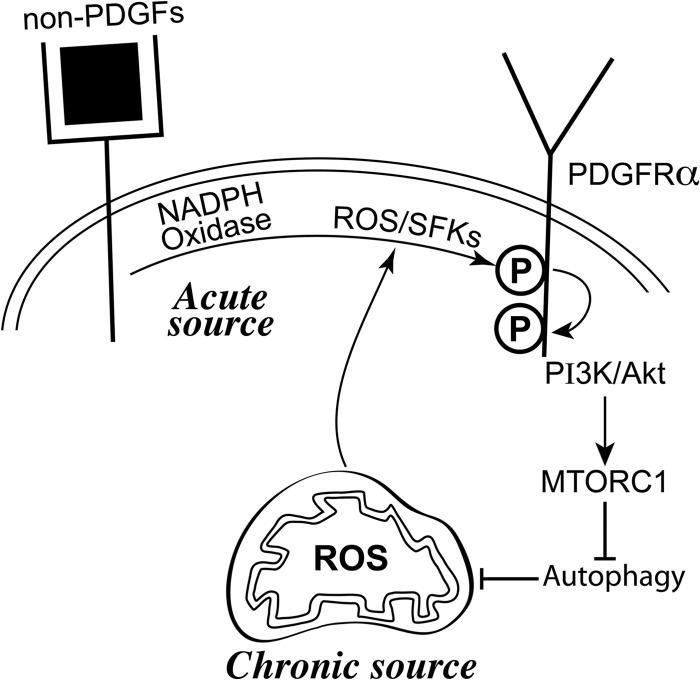

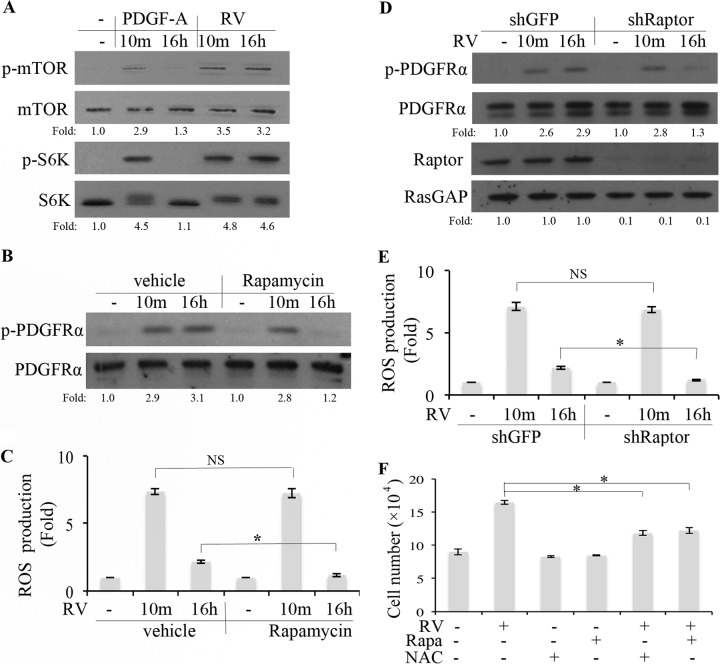

Reports from numerous labs indicate that activation of mTOR blocks autophagy and thereby allows accumulation of organelles, including mitochondria, which produce ROS (20, 49–51). Since vitreous-mediated activation of PDGFRα engages the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt pathway (17), which activates mTOR (52), we speculated that enduring activation of PDGFRα in vitreous-stimulated cells was dependent on an mTOR-mediated elevation in ROS (Fig. 4). Consistent with this idea was the observation that vitreous stimulated prolonged activation of mTOR and S6K (Fig. 5A). Furthermore, pharmacologically (addition of rapamycin) or molecularly (reducing expression of Raptor) suppressed mTOR activity and reduced the level of ROS and extent of PDGFRα phosphorylation in cells exposed to vitreous (Fig. 5B to E). Importantly, this effect was observed at the 16-h time point but not at the 10-min time point. Finally, rapamycin not only blocked vitreous-stimulated PDGFRα but also blocked its ability to promote proliferation (Fig. 5F). These data indicate that mTOR made an essential contribution to prolonged activation of PDGFRα and elevation of ROS, whereas it was dispensable for acute induction of these responses. The distinct requirement for mTOR suggested that the response to vitreous consisted of acute and prolonged phases that were dependent on nonidentical sets of signaling intermediates.

FIG 4.

Non-PDGFs in vitreous persistently activated PDGFRα by triggering a ROS-mediated self-perpetuating loop. Non-PDGFs in vitreous engage their own receptors and thereby acutely activate NADPH oxidase at the plasma membrane (19, 56, 57). The resulting rise in ROS activates SFKs (59, 60), which derepress the kinase activity of monomeric PDGFRα (13, 17). This priming event involves autophosphorylation of PDGFRα and activation of the PI3K/Akt pathway that engages mTORC1 and suppresses autophagy (17, 49, 50, 52). These events lead to an accumulation of ROS from mitochondrial sources, which sustain a pool of activated SFKs and thereby close an intracellular, ROS-driven autocrine loop that results in enduring activation of PDGFRα.

FIG 5.

RV stimulated mTORC1-dependent elevation of ROS, which was required for persistent activation of PDGFRα. (A and B) Near-confluent, serum-starved ARPE19α cells were pretreated with vehicle or rapamycin (100 nM) for 30 min and then stimulated with rabbit vitreous (RV) for 10 min or 16 h. The cells were harvested, and the resulting lysates were subjected to Western blot analysis with the following antibodies: pSer 2448 for p-mTOR and p-p70 S6 kinase for p-S6K. The fold values are the p-PDGFRα/PDGFRα ratio, the p-mTOR/mTOR ratio, or the p-S6K/S6K ratio. The data presented are representative of three independent experiments. (C) Cells were treated as described above for panel B and then washed, and the ROS level was determined as described in Materials and Methods. Values that are statistically significantly different (P < 0.05) are indicated by an asterisk and bar. Values that are not statistically significantly different are indicated by NS and a bar. (D) Near-confluent, serum-starved ARPE19α cells that stably expressed shRNA directed against gfp or raptor were treated with RV for 10 min or 16 h. The cells were lysed, and the resulting lysates were subjected to Western blot analyses using the indicated antibodies. The fold values are the p-PDGFRα/PDGFRα ratio or the Raptor/RasGAP ratio. The data presented are representative of three independent experiments. (E) Same as panel D, except that instead of lysing the cells for Western blot analysis, the level of ROS was determined as described in Materials and Methods. Values that are statistically significantly different (P < 0.05) are indicated by an asterisk and bar. Values that are not statistically significantly different are indicated by NS and a bar. (F) Serum-starved ARPE19α cells were cultured in medium containing RV, rapamycin (Rapa) (100 nM), or NAC (10 mM) for 3 days. The medium was refreshed daily, and the cells were counted at the end of day 3. These data are means ± standard deviations (SD) from three independent experiments. Values that are statistically significantly different (P < 0.05) are indicated by an asterisk and bar. Similar results were obtained when this experiment was repeated using primary human corneal fibroblasts instead of ARPE19α cells (data not shown).

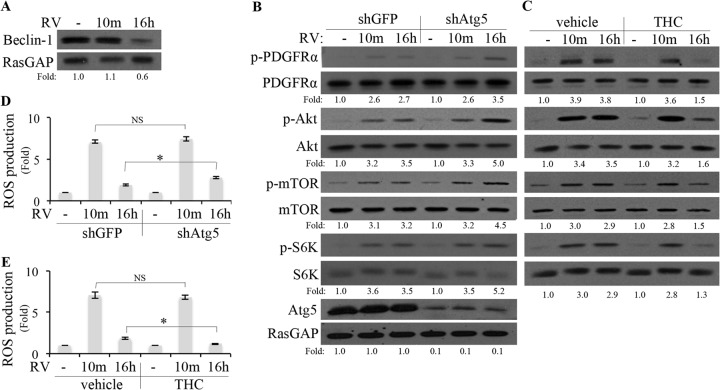

Inhibition of autophagy was necessary for vitreous-mediated, persistent activation of PDGFRα.

As mentioned above, mTOR-mediated suppression of autophagy is a plausible mechanism by which vitreous was elevating mitochondrial ROS and chronically activating PDGFRα. In support of this possibility, we observed that vitreous suppressed expression of beclin-1 (Fig. 6A), an indicator of autophagy (53). The timing of this change (16 h) corresponded to when mitochondrial ROS was elevated (see Fig. 7 below). Furthermore, antagonizing autophagy (by reducing the level of Atg5 [54]) enhanced vitreous-mediated elevation of ROS (albeit modestly) and activation of PDGFRα and downstream signaling events (Fig. 6B and D). The timing of this enhancement corresponded to when ROS was required from the mitochondria (16 h) and not the plasma membrane (via Nox at 10 min) (Fig. 7). Finally, activating autophagy (by exposing cells to tetrahydrocannabinol [THC] [55]) reduced vitreous-mediated elevation of ROS (albeit modestly) and activation of PDGFRα and downstream signaling events at the late, but not the early, time point (Fig. 6C). These results indicate that suppression of autophagy was required for the enduring elevation of ROS and activation of PDGFRα and downstream signaling events in cells exposed to vitreous.

FIG 6.

Inhibition of autophagy was necessary for RV-mediated, persistent activation of PDGFRα. (A) ARPE19α cells were permitted to reach 70% confluence, serum starved, exposed to RV for 10 min or 16 h, and then lysed. The resulting lysates were subjected to Western blot analysis using the indicated antibodies. RasGAP served as a loading control. The fold values are the beclin-1/RasGAP ratio. The data presented are representative of three independent experiments. (B) Near-confluent, serum-starved ARPE19α cells that stably expressed shRNA directed against gfp or atg5 were treated with RV for 10 min or 16 h. The cells were lysed, and the resulting lysates were subjected to Western blot analyses using the indicated antibodies. (C) Near-confluent, serum-starved ARPE19α cells were pretreated with THC (5 μM) for 110 min, after which time RV was added and the cells were lysed 10 min later; the cells were exposed to drug and RV for 120 and 10 min, respectively. To monitor the effect of THC at the 16-h time point, the cells were first exposed to RV for 14 h and then THC was added and the cells were lysed 120 min later; the cells were exposed to THC and RV for 120 min and 16 h, respectively. The lysates were subjected to Western blot analyses using the indicated antibodies. In panels B and C, the fold values are the p-PDGFRα/PDGFRα ratio, the p-Akt/Akt ratio, the p-mTOR/mTOR ratio, the p-S6K/S6K ratio, or the Atg5/RasGAP ratio. The data presented are representative of three independent experiments. (D and E) Same as panels B and C, respectively, except that instead of lysing the cells for Western blot analysis, the level of ROS was determined as described in Materials and Methods. Values that are statistically significantly different (P < 0.05) are indicated by an asterisk and bar. Values that are not statistically significantly different are indicated by NS and a bar.

FIG 7.

Mitochondrial ROS was required for persistent activation of PDGFRα in response to RV. (A and B) Near-confluent, serum-starved ARPE19α cells were pretreated with antimycin A (0.5 μM) (a mitochondrial electron transport inhibitor) or diphenyleneiodonium chloride (DPI) (5 μM) (an NADPH oxidase [NOX] inhibitor) for 20 min, after which time RV was added and the cells were lysed 10 min later; the cells were exposed to drug and RV for 30 and 10 min, respectively. To monitor the effects of the inhibitors at the 16-h time point, the cells were first exposed to RV for 15.5 h, the inhibitors were added, and the cells were lysed 30 min later; the cells were exposed to drug and RV for 30 min and 16 h, respectively. The lysates were subjected to Western blot analyses using the indicated antibodies. The fold values are the p-PDGFRα/PDGFRα ratio, the p-Akt/Akt ratio, the p-mTOR/mTOR ratio, or the p-S6K/S6K ratio. The data presented are representative of three independent experiments. Similar results were observed when carbonyl cyanide 3-chlorophenylhydrazone (CCCP) (50 μM) (a mitochondrial electron transport inhibitor) and acetovanillone (apocynin) (10 μM) (a NOX inhibitor) were used instead of antimycin and DPI (data not shown). (C) Near-confluent, serum-starved ARPE19α cells stably expressing a mitochondrion-localized redox-sensitive GFP mutant (31) were treated with DTT (1 mM) for 1 h, RV for 10 min or 16 h, or H2O2 (1 mM) for 30 min. The panels are photos of representative cells that were illuminated with an excitation wavelength of 400 nm or 484 nm and an emission wavelength of 525 nm. Five exposures were measured of different areas (consisting of the three to five cells) for each experimental condition. Values in the bar graph are means ± SD from at least 3 independent experiments. Values that are statistically significantly different (P < 0.05) are indicated by an asterisk and bar. Values that are not statistically significantly different are indicated by NS and a bar.

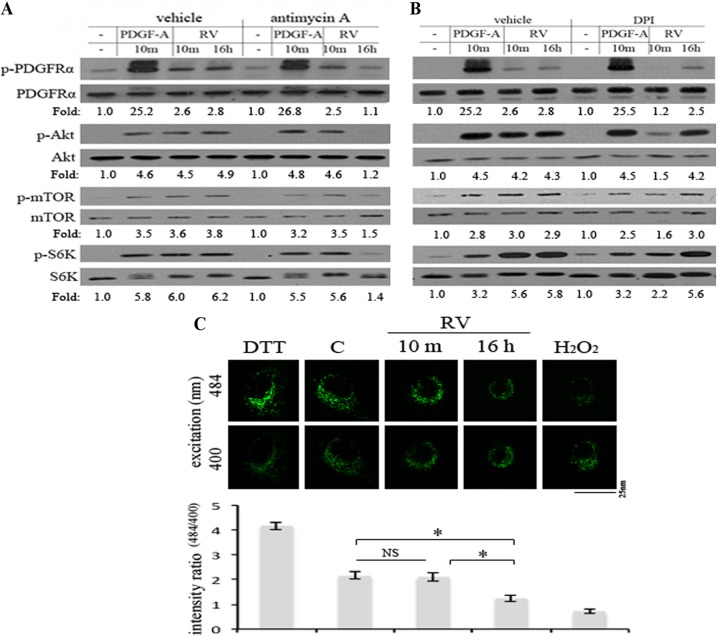

Mitochondrial ROS was required for persistent activation of PDGFRα in response to vitreous.

The acute (within minutes) rise in ROS seen in cells exposed to growth factors is due to Rac1-mediated activation of Nox (19, 56, 57). Consistent with these previous observations, we found that this source of ROS was required for early activation of PDGFRα and downstream signaling events (Akt, mTOR, and S6K) in vitreous-stimulated cells (Fig. 7B). In contrast, Nox inhibitors were ineffective on these events at the 16-h time point (Fig. 7B). Furthermore, mitochondrial inhibitors blocked vitreous-dependent activation of PDGFRα and downstream signaling events at the 16-h time point but had no effect at 10 min (Fig. 7A). Neither source of ROS was required for ligand-mediated activation of PDGFRα (Fig. 7A and B), which is consistent with our previous observation that antioxidants selectively interfered with the vitreous-mediated mode of activating PDGFRα (13, 58).

As a complementary approach to test the idea that the vitreous triggered a rise in mitochondrial ROS, we engineered cells to express a mitochondrion-localized redox-sensitive GFP mutant (31). As illustrated in Fig. 7C, increasing ROS (by adding H2O2) decreased the emission ratio measured at 484 and 400 nm, whereas the antioxidant dithiothreitol (DTT) increased this emission ratio. Figure 7C also shows that vitreous decreased the emission ratio and that this change was observed at 16 h but not at 10 min. This finding is consistent with the conclusions of the pharmacological approach, indicating that the mitochondria were the source of the ROS at the 16-h time point. The data in Fig. 7 support the idea that prolonged activation of PDGFRα in vitreous-stimulated cells is dependent on mitochondrial ROS.

The results presented herein, along with the references cited, support the working hypothesis diagrammed in Fig. 4 for the mechanism by which PDGFRα is steadfastly activated in cells exposed to vitreous. Non-PDGFs in vitreous engage their own receptors and thereby acutely activate Nox in the plasma membrane (19, 56, 57). The resulting rise in ROS activates SFKs (59, 60), which derepress the kinase activity of monomeric PDGFRα (13, 17). This priming event involves autophosphorylation of PDGFRα and activation of the PI3K/Akt pathway that engages mTORC1 and suppresses autophagy (17, 49, 50, 52). These events lead to an accumulation of ROS from mitochondria, which sustain a pool of activated SFKs and thereby close an intracellular, ROS-driven loop that results in enduring activation of PDGFRα.

The mechanism outlined in Fig. 4 provides a plausible explanation for the antifibrotic action of rapamycin in both experimental animals and patients (61–63). By inhibiting mTOR, rapamycin increases autophagy and thereby reduces the level of ROS emanating from mitochondria (20). This line of reasoning depends on the assumption that indirect activation of PDGFRα is an epigenesis-based mechanism that contributes to fibrotic diseases other than PVR. Support for this concept stems from the observation that mice harboring the D842V PDGFRα mutant, which engages signaling events that are preferentially engaged by the indirectly activated PDGFRα (17), develop fibrosis in multiple organs (47). Ongoing investigation is focused on testing this possibility.

While inhibition of autophagy and subsequent accumulation of ROS from the mitochondria were the emphasis of this study, there are additional mechanisms that may contribute to sustaining activation of PDGFRα in cells exposed to vitreous. For instance, activation of the PI3K/Akt pathway enhances glucose uptake and thereby elevates ROS (64, 65). Since vitreous activates the PI3K/Akt pathway (17), it may also deregulate glucose metabolism and thereby increase and sustain an elevated level of ROS. Alternatively, or perhaps in addition, since vitreous potently reduces the level of p53 (17), this change may contribute to a rise in ROS by depressing expression of antioxidant genes (66).

Like these intracellular changes, the composition of growth factors to which cells are exposed is likely to be a relevant variable in determining the duration of PDGFRα activation. PDGFs and non-PDGFs trigger acute or enduring activation of PDGFRα, respectively. When saturating levels of both PDGF and non-PDGFs are present, then acute activation predominates because PDGF induces dimerization of PDGFRα and thereby both shortens the half-life of PDGFRα and makes it a poor substrate for SFKs (67). Surprisingly, when vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) is also present, then indirect activation of PDGFRα predominates. This is because VEGF binds to monomeric PDGFRα and not only prevents PDGF from dimerizing it but also enables its activation by SFKs (18). Finally, since activating mTORC1 can increase the level of hypoxia-inducible factor 1α (HIF1α), which promotes synthesis of VEGF (68), chronically activated PDGFRα may increase the level of VEGF by this mTORC1-driven route and thereby perpetuate its activation. We conclude that both the composition of growth factors that cells encounter and the intracellular signaling events that they initiate conspire to chronically activate PDGFRα.

Our findings that antagonizing autophagy is essential for prolonged activation of PDGFRα suggest that autophagy promotes tumorigenesis (69) at least in part by chronically activating PDGFRα. This possibility is supported by the observation that constitutive activation of PDGFRα is associated with a subset of solid tumors (3, 70–72). While genetic changes or coexpression with PDGF is often observed and therefore the presumed mechanism driving pathology, our findings suggest that the mitochondrial ROS-driven mechanism may also contribute. Furthermore, reducing the level of p53, which the chronically activated PDGFRα does very effectively (17), may predispose cells to secondary events that promote cancer progression (73). Additional studies are necessary to further consider these possibilities.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Paul Schumacker (Northwestern University, Chicago, IL) for the Mito-RoGFP cDNA plasmid and James Zieske (Schepens Eye Research Institute/Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary) for primary human corneal fibroblasts. We also thank Sarah Jacobo and Guoxiang Ruan for critical input on the manuscript and Steven Pennock for guidance establishing the acid washing procedure.

Funding for this work was provided by NIH grant EY012509.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 4 November 2013

REFERENCES

- 1.Heinrich MC, Corless CL, Duensing A, McGreevey L, Chen CJ, Joseph N, Singer S, Griffith DJ, Haley A, Town A, Demetri GD, Fletcher CD, Fletcher JA. 2003. PDGFRA activating mutations in gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Science 299:708–710. 10.1126/science.1079666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hirota S, Ohashi A, Nishida T, Isozaki K, Kinoshita K, Shinomura Y, Kitamura Y. 2003. Gain-of-function mutations of platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha gene in gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Gastroenterology 125:660–667. 10.1016/S0016-5085(03)01046-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andrae J, Gallini R, Betsholtz C. 2008. Role of platelet-derived growth factors in physiology and medicine. Genes Dev. 22:1276–1312. 10.1101/gad.1653708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baroni SS, Santillo M, Bevilacqua F, Luchetti M, Spadoni T, Mancini M, Fraticelli P, Sambo P, Funaro A, Kazlauskas A, Avvedimento EV, Gabrielli A. 2006. Stimulatory autoantibodies to the PDGF receptor in systemic sclerosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 354:2667–2676. 10.1056/NEJMoa052955 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lei H, Velez G, Hovland P, Hirose T, Gilbertson D, Kazlauskas A. 2009. Growth factors outside the PDGF family drive experimental PVR. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 50:3394–3403. 10.1167/iovs.08-3042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clempus RE, Griendling KK. 2006. Reactive oxygen species signaling in vascular smooth muscle cells. Cardiovasc. Res. 71:216–225. 10.1016/j.cardiores.2006.02.033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lambeth JD. 2004. NOX enzymes and the biology of reactive oxygen. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 4:181–189. 10.1038/nri1312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oakley FD, Abbott D, Li Q, Engelhardt JF. 2009. Signaling components of redox active endosomes: the redoxosomes. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 11:1313–1333. 10.1089/ars.2008.2363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meng TC, Fukada T, Tonks NK. 2002. Reversible oxidation and inactivation of protein tyrosine phosphatases in vivo. Mol. Cell 9:387–399. 10.1016/S1097-2765(02)00445-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tonks NK. 2005. Redox redux: revisiting PTPs and the control of cell signaling. Cell 121:667–670. 10.1016/j.cell.2005.05.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rhee SG, Kang SW, Jeong W, Chang TS, Yang KS, Woo HA. 2005. Intracellular messenger function of hydrogen peroxide and its regulation by peroxiredoxins. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 17:183–189. 10.1016/j.ceb.2005.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Choi MH, Lee IK, Kim GW, Kim BU, Han YH, Yu DY, Park HS, Kim KY, Lee JS, Choi C, Bae YS, Lee BI, Rhee SG, Kang SW. 2005. Regulation of PDGF signalling and vascular remodelling by peroxiredoxin II. Nature 435:347–353. 10.1038/nature03587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lei H, Kazlauskas A. 2009. Growth factors outside of the platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) family employ reactive oxygen species/Src family kinases to activate PDGF receptor alpha and thereby promote proliferation and survival of cells. J. Biol. Chem. 284:6329–6336. 10.1074/jbc.M808426200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Giannoni E, Buricchi F, Raugei G, Ramponi G, Chiarugi P. 2005. Intracellular reactive oxygen species activate Src tyrosine kinase during cell adhesion and anchorage-dependent cell growth. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25:6391–6403. 10.1128/MCB.25.15.6391-6403.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kemble DJ, Sun G. 2009. Direct and specific inactivation of protein tyrosine kinases in the Src and FGFR families by reversible cysteine oxidation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106:5070–5075. 10.1073/pnas.0806117106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yoo SK, Starnes TW, Deng Q, Huttenlocher A. 2011. Lyn is a redox sensor that mediates leukocyte wound attraction in vivo. Nature 480:109–112. 10.1038/nature10632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lei H, Velez G, Kazlauskas A. 2011. Pathological signaling via platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha involves chronic activation of Akt and suppression of p53. Mol. Cell. Biol. 31:1788–1799. 10.1128/MCB.01321-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pennock S, Kazlauskas A. 2012. Vascular endothelial growth factor A competitively inhibits platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF)-dependent activation of PDGF receptor and subsequent signaling events and cellular responses. Mol. Cell. Biol. 32:1955–1966. 10.1128/MCB.06668-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bae YS, Sung JY, Kim OS, Kim YJ, Hur KC, Kazlauskas A, Rhee SG. 2000. Platelet-derived growth factor-induced H2O2 production requires the activation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 275:10527–10531. 10.1074/jbc.275.14.10527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gottlieb RA, Carreira RS. 2010. Autophagy in health and disease. 5. Mitophagy as a way of life. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 299:C203–C210. 10.1152/ajpcell.00097.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kazlauskas A. 1994. Receptor tyrosine kinases and their targets. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 4:5–14. 10.1016/0959-437X(94)90085-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Claesson-Welsh L. 1994. Platelet-derived growth factor receptor signals. J. Biol. Chem. 269:32023–32026 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hooshmand-Rad R, Yokote K, Heldin CH, Claesson-Welsh L. 1998. PDGF alpha-receptor mediated cellular responses are not dependent on Src family kinases in endothelial cells. J. Cell Sci. 111:607–614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gelderloos JA, Rosenkranz S, Bazenet C, Kazlauskas A. 1998. A role for Src in signal relay by the platelet-derived growth factor alpha receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 273:5908–5915. 10.1074/jbc.273.10.5908 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sicheri F, Kuriyan J. 1997. Structures of Src-family tyrosine kinases. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 7:777–785. 10.1016/S0959-440X(97)80146-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Blake RA, Broome MA, Liu X, Wu J, Gishizky M, Sun L, Courtneidge SA. 2000. SU6656, a selective src family kinase inhibitor, used to probe growth factor signaling. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20:9018–9027. 10.1128/MCB.20.23.9018-9027.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bazenet C, Kazlauskas A. 1994. The PDGF receptor alpha subunit activates p21ras and triggers DNA synthesis without interacting with rasGAP. Oncogene 9:517–525 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lei H, Rheaume MA, Velez G, Mukai S, Kazlauskas A. 2011. Expression of PDGFRalpha is a determinant of the PVR potential of ARPE19 cells. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 52:5016–5021. 10.1167/iovs.11-7442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Andrews A, Balciunaite E, Leong FL, Tallquist M, Soriano P, Refojo M, Kazlauskas A. 1999. Platelet-derived growth factor plays a key role in proliferative vitreoretinopathy. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 40:2683–2689 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ory DS, Neugeboren BA, Mulligan RC. 1996. A stable human-derived packaging cell line for production of high titer retrovirus/vesicular stomatitis virus G pseudotypes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 93:11400–11406. 10.1073/pnas.93.21.11400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Waypa GB, Marks JD, Guzy R, Mungai PT, Schriewer J, Dokic D, Schumacker PT. 2010. Hypoxia triggers subcellular compartmental redox signaling in vascular smooth muscle cells. Circ. Res. 106:526–535. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.206334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lei H, Venkatakrishnan A, Yu S, Kazlauskas A. 2007. Protein kinase A-dependent translocation of Hsp90 alpha impairs endothelial nitric-oxide synthase activity in high glucose and diabetes. J. Biol. Chem. 282:9364–9371. 10.1074/jbc.M608985200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jones SM, Kazlauskas A. 2001. Growth-factor-dependent mitogenesis requires two distinct phases of signalling. Nat. Cell Biol. 3:165–172. 10.1038/35055073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.DeMali KA, Whiteford CC, Ulug ET, Kazlauskas A. 1997. PDGF-dependent cellular transformation requires either PLC gamma or PI3K. J. Biol. Chem. 272:9011–9018. 10.1074/jbc.272.14.9011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kypta RM, Goldberg Y, Ulug ET, Courtneidge SA. 1990. Association between the PDGF receptor and members of the src family of tyrosine kinases. Cell 62:481–492. 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90013-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Baxter RM, Secrist JP, Vaillancourt RR, Kazlauskas A. 1998. Full activation of the platelet-derived growth factor beta-receptor kinase involves multiple events. J. Biol. Chem. 273:17050–17055. 10.1074/jbc.273.27.17050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lei H, Hovland P, Velez G, Haran A, Gilbertson D, Hirose T, Kazlauskas A. 2007. A potential role for PDGF-C in experimental and clinical proliferative vitreoretinopathy. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 48:2335–2342. 10.1167/iovs.06-0965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pennock S, Rheaume MA, Mukai S, Kazlauskas A. 2011. A novel strategy to develop therapeutic approaches to prevent proliferative vitreoretinopathy. Am. J. Pathol. 179:2931–2940. 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.08.043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bazenet CE, Gelderloos JA, Kazlauskas A. 1996. Phosphorylation of tyrosine 720 in the platelet-derived growth factor alpha receptor is required for binding of Grb2 and SHP-2 but not for activation of Ras or cell proliferation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16:6926–6936 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Songyang Z, Carraway KLI, Eck MJ, Harrison SC, Feldman RA, Mohammadi M, Schlessinger J, Hubbard SR, Smith DP, Eng C, Lorenzo MJ, Ponder BAJ, Mayer BJ, Cantley LC. 1995. Catalytic specificity of protein-tyrosine kinases is critical for selective signalling. Nature 373:536–539. 10.1038/373536a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Songyang Z, Blechner S, Hoaglund N, Hoekstra MF, Piwnica-Worms H, Cantley LC. 1994. Use of an oriented peptide library to determine the optimal substrates of protein kinases. Curr. Biol. 4:973–982. 10.1016/S0960-9822(00)00221-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Songyang Z, Shoelson SE, Chaudhuri M, Gish G, Pawson T, Haser WG, King F, Roberts T, Ratnofsky S, Lechleider RJ, Neel BJ, Birge RB, Fajardo J, Chou MM, Hanafusa H, Schaffhausen B, Cantley LC. 1993. SH2 domains recognize specific phosphopeptide sequences. Cell 72:767–778. 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90404-E [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hubbard SR. 2004. Juxtamembrane autoinhibition in receptor tyrosine kinases. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 5:464–471. 10.1038/nrm1399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Klinghoffer RA, Sachsenmaier C, Cooper JA, Soriano P. 1999. Src family kinases are required for integrin but not PDGFR signal transduction. EMBO J. 18:2459–2471. 10.1093/emboj/18.9.2459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lei H, Rheaume MA, Kazlauskas A. 2010. Recent developments in our understanding of how platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) and its receptors contribute to proliferative vitreoretinopathy. Exp. Eye Res. 90:376–381. 10.1016/j.exer.2009.11.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sorkin A, Goh LK. 2009. Endocytosis and intracellular trafficking of ErbBs. Exp. Cell Res. 315:683–696. 10.1016/j.yexcr.2008.07.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Olson LE, Soriano P. 2009. Increased PDGFRalpha activation disrupts connective tissue development and drives systemic fibrosis. Dev. Cell 16:303–313. 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.12.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rosenkranz S, Ikuno Y, Leong FL, Klinghoffer RA, Miyake S, Band H, Kazlauskas A. 2000. Src family kinases negatively regulate platelet-derived growth factor alpha receptor-dependent signaling and disease progression. J. Biol. Chem. 275:9620–9627. 10.1074/jbc.275.13.9620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lee JH, Budanov AV, Park EJ, Birse R, Kim TE, Perkins GA, Ocorr K, Ellisman MH, Bodmer R, Bier E, Karin M. 2010. Sestrin as a feedback inhibitor of TOR that prevents age-related pathologies. Science 327:1223–1228. 10.1126/science.1182228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Guertin DA, Sabatini DM. 2005. An expanding role for mTOR in cancer. Trends Mol. Med. 11:353–361. 10.1016/j.molmed.2005.06.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lee J, Giordano S, Zhang J. 2012. Autophagy, mitochondria and oxidative stress: cross-talk and redox signalling. Biochem. J. 441:523–540. 10.1042/BJ20111451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Manning BD, Cantley LC. 2003. Rheb fills a GAP between TSC and TOR. Trends Biochem. Sci. 28:573–576. 10.1016/j.tibs.2003.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Li ZY, Yang Y, Ming M, Liu B. 2011. Mitochondrial ROS generation for regulation of autophagic pathways in cancer. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 414:5–8. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.09.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kuma A, Hatano M, Matsui M, Yamamoto A, Nakaya H, Yoshimori T, Ohsumi Y, Tokuhisa T, Mizushima N. 2004. The role of autophagy during the early neonatal starvation period. Nature 432:1032–1036. 10.1038/nature03029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Salazar M, Carracedo A, Salanueva IJ, Hernandez-Tiedra S, Lorente M, Egia A, Vazquez P, Blazquez C, Torres S, Garcia S, Nowak J, Fimia GM, Piacentini M, Cecconi F, Pandolfi PP, Gonzalez-Feria L, Iovanna JL, Guzman M, Boya P, Velasco G. 2009. Cannabinoid action induces autophagy-mediated cell death through stimulation of ER stress in human glioma cells. J. Clin. Invest. 119:1359–1372. 10.1172/JCI37948 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sundaresan M, Yu ZX, Ferrans VJ, Sulciner DJ, Gutkind JS, Irani K, Goldschmidt-Clermont PJ, Finkel T. 1996. Regulation of reactive-oxygen-species generation in fibroblasts by Rac1. Biochem. J. 318(Part 2):379–382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Suh YA, Arnold RS, Lassegue B, Shi J, Xu X, Sorescu D, Chung AB, Griendling KK, Lambeth JD. 1999. Cell transformation by the superoxide-generating oxidase Mox1. Nature 401:79–82. 10.1038/43459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lei H, Velez G, Cui J, Samad A, Maberley D, Matsubara J, Kazlauskas A. 2010. N-acetylcysteine suppresses retinal detachment in an experimental model of proliferative vitreoretinopathy. Am. J. Pathol. 177:132–140. 10.2353/ajpath.2010.090604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hardwick JS, Sefton BM. 1995. Activation of the Lck tyrosine protein kinase by hydrogen peroxide requires the phosphorylation of Tyr-394. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 92:4527–4531. 10.1073/pnas.92.10.4527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Abe J, Takahashi M, Ishida M, Lee JD, Berk BC. 1997. c-Src is required for oxidative stress-mediated activation of big mitogen-activated protein kinase 1. J. Biol. Chem. 272:20389–20394. 10.1074/jbc.272.33.20389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yoshizaki A, Yanaba K, Yoshizaki A, Iwata Y, Komura K, Ogawa F, Takenaka M, Shimizu K, Asano Y, Hasegawa M, Fujimoto M, Sato S. 2010. Treatment with rapamycin prevents fibrosis in tight-skin and bleomycin-induced mouse models of systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Rheum. 62:2476–2487. 10.1002/art.27498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pontrelli P, Rossini M, Infante B, Stallone G, Schena A, Loverre A, Ursi M, Verrienti R, Maiorano A, Zaza G, Ranieri E, Gesualdo L, Ditonno P, Bettocchi C, Schena FP, Grandaliano G. 2008. Rapamycin inhibits PAI-1 expression and reduces interstitial fibrosis and glomerulosclerosis in chronic allograft nephropathy. Transplantation 85:125–134. 10.1097/01.tp.0000296831.91303.9a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rangan GK, Coombes JD. 2007. Renoprotective effects of sirolimus in non-immune initiated focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 22:2175–2182. 10.1093/ndt/gfm191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.DeBerardinis RJ, Lum JJ, Hatzivassiliou G, Thompson CB. 2008. The biology of cancer: metabolic reprogramming fuels cell growth and proliferation. Cell Metab. 7:11–20. 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Vander Heiden MG, Cantley LC, Thompson CB. 2009. Understanding the Warburg effect: the metabolic requirements of cell proliferation. Science 324:1029–1033. 10.1126/science.1160809 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Vousden KH. 2010. Alternative fuel–another role for p53 in the regulation of metabolism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107:7117–7118. 10.1073/pnas.1002656107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Pennock S, Kim D, Mukai S, Kuhnle M, Chun DW, Matsubara J, Cui J, Ma P, Maberley D, Samad A, Van Geest RJ, Oberstein SL, Schlingemann RO, Kazlauskas A. 2013. Ranibizumab is a potential prophylaxis for proliferative vitreoretinopathy, a nonangiogenic blinding disease. Am. J. Pathol. 182:1659–1670. 10.1016/j.ajpath.2013.01.052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Brugarolas J, Kaelin WG., Jr 2004. Dysregulation of HIF and VEGF is a unifying feature of the familial hamartoma syndromes. Cancer Cell 6:7–10. 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.06.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wang RC, Wei Y, An Z, Zou Z, Xiao G, Bhagat G, White M, Reichelt J, Levine B. 2012. Akt-mediated regulation of autophagy and tumorigenesis through Beclin 1 phosphorylation. Science 338:956–959. 10.1126/science.1225967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ozawa T, Brennan CW, Wang L, Squatrito M, Sasayama T, Nakada M, Huse JT, Pedraza A, Utsuki S, Yasui Y, Tandon A, Fomchenko EI, Oka H, Levine RL, Fujii K, Ladanyi M, Holland EC. 2010. PDGFRA gene rearrangements are frequent genetic events in PDGFRA-amplified glioblastomas. Genes Dev. 24:2205–2218. 10.1101/gad.1972310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Feng H, Hu B, Liu KW, Li Y, Lu X, Cheng T, Yiin JJ, Lu S, Keezer S, Fenton T, Furnari FB, Hamilton RL, Vuori K, Sarkaria JN, Nagane M, Nishikawa R, Cavenee WK, Cheng SY. 2011. Activation of Rac1 by Src-dependent phosphorylation of Dock180(Y1811) mediates PDGFRalpha-stimulated glioma tumorigenesis in mice and humans. J. Clin. Invest. 121:4670–4684. 10.1172/JCI58559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Liu KW, Feng H, Bachoo R, Kazlauskas A, Smith EM, Symes K, Hamilton RL, Nagane M, Nishikawa R, Hu B, Cheng SY. 2011. SHP-2/PTPN11 mediates gliomagenesis driven by PDGFRA and INK4A/ARF aberrations in mice and humans. J. Clin. Invest. 121:905–917. 10.1172/JCI43690 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Levine AJ. 1997. p53, the cellular gatekeeper for growth and division. Cell 88:323–331. 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81871-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Rosenkranz S, DeMali KA, Gelderloos JA, Bazenet C, Kazlauskas A. 1999. Identification of the receptor-associated signaling enzymes that are required for platelet-derived growth factor-AA-dependent chemotaxis and DNA synthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 274:28335–28343. 10.1074/jbc.274.40.28335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]