Abstract

The clinical usefulness of detecting telaprevir-resistant variants is unclear. Two hundred fifty-two Japanese patients infected with hepatitis C virus (HCV) genotype 1b received triple therapy with telaprevir–peginterferon (PEG-IFN)–ribavirin and were evaluated for telaprevir-resistant variants by direct sequencing at baseline and at the time of reelevation of the viral load. An analysis of the entire group indicated that 76% achieved a sustained virological response. Multivariate analysis identified a PEG-IFN dose of <1.3 μg/kg of body weight, an IL28B rs8099917 genotype (genotype non-TT), detection of telaprevir-resistant variants of amino acid (aa) 54 at baseline, nonresponse to prior treatment, and a leukocyte count of <5,000/mm3 as significant pretreatment factors for detection of telaprevir-resistant variants at the time of reelevation of the viral load. In 63 patients who showed nonresponse to prior treatment, a higher proportion of patients with no detected telaprevir-resistant variants at baseline (54%) achieved a sustained virological response than did patients with detected telaprevir-resistant variants at baseline (0%). Furthermore, 2 patients who did not have a sustained virological response from the first course of triple therapy with telaprevir received a second course of triple therapy with telaprevir. These patients achieved a sustained virological response by the second course despite the persistence of very-high-frequency variants (98.1% for V36C) or a history of the emergence of variants (0.2% for R155Q and 0.2% for A156T) by ultradeep sequencing. In conclusion, this study indicates that the presence of telaprevir-resistant variants at the time of reelevation of viral load can be predicted by a combination of host, viral, and treatment factors. The presence of resistant variants at baseline might partly affect treatment efficacy, especially in those with nonresponse to prior treatment.

INTRODUCTION

New strategies have been introduced recently for the treatment of chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection based on the inhibition of protease in the nonstructural 3 (NS3)/NS4 region of the HCV polyprotein. Of the new agents currently available, telaprevir (VX-950) is used for the treatment of chronic HCV infection (1). Three studies (PROVE1, PROVE2, and a Japanese study [2–4]) showed that a 24-week regimen of triple therapy (telaprevir, peginterferon [PEG-IFN], and ribavirin) for 12 weeks followed by dual therapy (PEG-IFN and ribavirin) for 12 weeks (also called the T12PR24 regimen) achieved sustained virological response (SVR) (negative for HCV RNA for >24 weeks after the withdrawal of treatment) rates of 61%, 69%, and 73%, respectively, in patients infected with HCV genotype 1 (HCV-1). However, another study (PROVE3) found lower SVR rates to the T12PR24 regimen (39%) in nonresponders to previous PEG-IFN–ribavirin therapy infected with HCV-1 who did not achieve HCV RNA negativity during or at the end of the initial triple therapy course (5).

Telaprevir-based therapy is reported to induce resistant variants of HCV (6, 7). A recent report indicated that resistant variants are observed in most patients after failure to achieve an SVR by telaprevir-based treatment and that they tend to be replaced with wild-type viruses over time, presumably due to the lower fitness of those variants (8). However, the clinical usefulness of detecting telaprevir-resistant variants is still unclear. First of all, pretreatment factors associated with the detection of telaprevir-resistant variants at the time of reelevation of viral load have not been investigated. Furthermore, it is not clear at this stage whether the detection of telaprevir-resistant variants at baseline is useful for predicting the efficacy of telaprevir-based treatment and whether a history of the emergence of telaprevir-resistant variants affects treatment efficacy with the second course of telaprevir-based treatment.

Based on the above background, there is a need to investigate the clinical usefulness of detecting telaprevir-resistant variants. The aim of this study was to determine the pretreatment factors associated with the subsequent detection of telaprevir-resistant variants at the time of reelevation of viral load and the importance of telaprevir-resistant variants for predicting the efficacy of telaprevir-based treatment in patients infected with HCV-1b.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study population.

From May 2008 through August 2013, 340 consecutive patients infected with HCV were selected for triple therapy with telaprevir (MP-424 or Telavic; Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, Osaka, Japan), PEG-IFN-α2b (PegIntron; MSD, Tokyo, Japan), and ribavirin (Rebetol; MSD, Tokyo) at the Department of Hepatology, Toranomon Hospital (located in metropolitan Tokyo, Japan). Subsequently, 252 of these patients received the triple therapy based on the following inclusion and exclusion criteria: (i) diagnosis of chronic hepatitis C, (ii) HCV-1b confirmed by sequence analysis, (iii) HCV RNA level of ≥5.0 log IU/ml as determined by the Cobas TaqMan HCV test (Roche Diagnostics, Tokyo, Japan), (iv) follow-up duration of ≥24 weeks after the completion of triple therapy, (v) no history of treatment with NS3/4A protease inhibitors, (vi) absence of decompensated liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), (vii) negative for hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg), (viii) no evidence of human immunodeficiency virus infection, (ix) negative history of autoimmune hepatitis, alcohol liver disease, hemochromatosis, and chronic liver disease other than chronic hepatitis C, (x) negative history of depression, schizophrenia, or suicide attempts, angina pectoris, cardiac insufficiency, myocardial infarction, severe arrhythmia, uncontrolled hypertension, uncontrolled diabetes, chronic renal dysfunction, cerebrovascular disorders, thyroidal dysfunction uncontrolled by medical treatment, chronic pulmonary disease, allergy to medication, or anaphylaxis at baseline, and (xi) pregnant or breastfeeding women or those willing to become pregnant during the study and men with a pregnant partner were excluded. The study protocol was in compliance with the guidelines for good clinical practice and the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the institutional review board of the Toranomon Hospital. Each patient received ample information about the goals and potential side effects of the treatment and their right to withdraw from the study at any time. Each patient provided a signed consent form before participating in this trial.

The efficacy of treatment was evaluated by the presence or absence of an HCV RNA-negative result at 24 weeks after the completion of therapy (i.e., SVR), as determined by the Cobas TaqMan HCV test (Roche Diagnostics). Furthermore, failure to achieve an SVR was classified as nonresponse (HCV RNA detected during or at the end of treatment) or relapse (at the time of reelevation of viral load after the end of treatment, even when HCV RNA result was negative at the end of treatment).

Twenty patients (8%) were assigned to a 12-week regimen of triple therapy (the T12PR12 group) and were randomly divided into two groups (10 patients each) treated with either 1,500 mg/day or 2,250 mg/day of telaprevir to evaluate the treatment efficacy during 12 weeks on treatment. Sixty patients (24%) were allocated to a 24-week regimen of the same triple therapy described above followed by dual therapy of PEG-IFN and ribavirin for another 12 weeks (the T12PR24 group) to evaluate treatment efficacy according to the response to prior treatment, and they were treated with 2,250 mg/day of telaprevir. Another group of 172 patients (68%) was treated as described above for the T12PR24 group except for the dosages of telaprevir; this group was divided into two groups treated with either 1,500 mg/day (111 patients) or 2,250 mg/day (61 patients) of telaprevir, as selected by the attending physician. Table 1 summarizes the profiles and laboratory data of the entire group of 252 patients at the commencement of treatment. They included 155 males and 97 females 21 to 73 years of age (median, 58 years). At the start of treatment, telaprevir was administered at a median dose of 30.8 mg/kg of body weight (range, 14.1 to 59.2 mg/kg) daily. One hundred thirty-one patients (52%) were treated with 2,250 mg/day of telaprevir, while the other 121 patients (48%) were treated with 1,500 mg/day of telaprevir. PEG-IFN-α2b was injected subcutaneously at a median dose of 1.5 μg/kg (range, 0.7 to 1.8 μg/kg) once a week. Ribavirin was administered at a median dose of 10.9 mg/kg (range, 4.3 to 15.8 mg/kg) daily. Each drug was discontinued or its dose reduced as required per the judgment of the attending physician, in response to a fall in hemoglobin level, leukocyte count, neutrophil count, or platelet count, or the appearance of side effects. The triple therapy was discontinued when the leukocyte count decreased to <1,000/mm3, the neutrophil count decreased to <500/mm3, the platelet count decreased to <5.0 × 104/mm3, or when hemoglobin decreased to <8.5 g/dl.

TABLE 1.

Profile and laboratory data at commencement of telaprevir, peginterferon, and ribavirin triple therapy in patients infected with HCV genotype 1b

| Variable | Patient data |

|---|---|

| Patient demographics | |

| No. of patients | 252 |

| Sex (no. of males/no. of females) | 155/97 |

| Median age (yr) (range) | 58 (21–73) |

| Median body mass index (kg/m2) (range) | 22.8 (16.0–36.7) |

| Laboratory data (median [range]) | |

| Level of viremia (log IU/ml) | 6.7 (5.0–7.8) |

| Aspartate aminotransferase (IU/liter) | 37 (15–624) |

| Alanine aminotransferase (IU/liter) | 42 (11–525) |

| Albumin (g/dl) | 3.9 (2.5–4.7) |

| Gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase (IU/liter) | 34 (3–319) |

| Leukocyte count (/mm3) | 4,700 (2,000–8,400) |

| Hemoglobin (g/dl) | 14.3 (12.1–17.6) |

| Platelet count (104/mm3) | 16.5 (8.5–33.8) |

| Treatment | |

| Median PEG-IFN-α2b dose (μg/kg) (range) | 1.5 (0.7–1.8) |

| Median ribavirin dose (mg/kg) (range) | 10.9 (4.3–15.8) |

| Median telaprevir dose (mg/kg) (range) | 30.8 (14.1–59.2) |

| No. of patients with telaprevir dose of 1,500/2,250 mg/day | 121/131 |

| No. of patients on T12PR12/T12PR24 treatment regimen | 20/232 |

| Response to prior treatment | |

| No. of treatment-naive patients/no. of patients with relapse to prior treatment/no. of patients with nonresponse to prior treatment (IFN monotherapy/ribavirin combination therapy)/unknown | 79/109/63 (16/47)/1 |

| Amino acid substitutions in HCV genotype 1b | |

| Core aa 70 (arginine/glutamine [histidine]/NDa) | 162/88/2 |

| Core aa 91 (leucine/methionine/ND) | 139/111/2 |

| ISDR of NS5A (wild type/non-wild type/ND) | 199/24/29 |

| IRRDR of NS5A (≤5/≥6/ND) | 180/69/3 |

| V3 of NS5A (≤2/≥3/ND) | 64/185/3 |

| IL28B genotype | |

| rs8099917 genotype (TT/non-TT/ND) | 181/69/2 |

| ITPA genotype | |

| rs112735 genotype (CC/non-CC) | 186/65/1 |

| NS3/4A protease inhibitor-resistant variants by direct sequencingb | |

| V36/T54/Q80/R155/A156/D168/V170 | 1/7/55/1/2/26/0 |

Follow-up.

Clinical and laboratory assessments were performed at least once every month before, during, and after treatment. They were performed every week in the initial 12 weeks of treatment. Adverse effects were monitored clinically by careful interviews and a medical examination at least once every month. Compliance with treatment was evaluated by a questionnaire.

Measurement of HCV RNA.

The antiviral effects of the triple therapy on HCV were assessed by measuring blood plasma HCV RNA levels. In this study, HCV RNA levels during treatment were evaluated at least once every month before, during, and after therapy. HCV RNA concentrations were determined using the Cobas TaqMan HCV test (Roche Diagnostics). The linear dynamic range of the assay was 1.2 to 7.8 log IU/ml, and undetectable samples were defined as negative.

Determination of IL28B and ITPA genotypes.

The IL28B rs8099917 and ITPA rs112735 genotypes have been reported as predictors of treatment efficacy and side effects to PEG-IFN–ribavirin dual therapy, and they were genotyped by using the Invader assay, TaqMan assay, or direct sequencing, as described previously (9–13).

Detection of amino acid substitutions in core and NS5A regions of HCV-1b.

With the use of HCV-J (GenBank accession no. D90208) as a reference type (14), the sequence of amino acids (aa) 1 to 191 in the core protein of HCV-1b was determined and then compared with the consensus sequence constructed in a previous study to detect substitutions at aa 70 of arginine (Arg70) or glutamine/histidine (Gln70/His70) and at aa 91 of leucine (Leu91) or methionine (Met91) (15). The sequence of aa 2209 to 2248 in the NS5A of HCV-1b (the interferon sensitivity-determining region [ISDR]) reported by Enomoto and coworkers (16) was determined, and the number of amino acid substitutions in the ISDR was defined as wild type (≤1) or non-wild type (≥2) compared to that of HCV-J. Furthermore, the sequence of aa 2334 to 2379 in the NS5A region of HCV-1b (the IFN/ribavirin resistance-determining region [IRRDR]) reported by El-Shamy and coworkers (17), including the sequence of aa 2356 to 2379 referred to as the variable region 3 (V3), was determined and then compared with the consensus sequence constructed in a previous study. The numbers of amino acid substitutions in the IRRDR and V3 regions were divided into two groups for analysis (those with ≤5 and ≥6 aa substitutions in the IRRDR, and those with ≤2 and ≥3 aa substitutions in the V3). In the present study, the amino acid substitutions of the core region and the NS5A-ISDR/IRRDR/V3 of HCV-1b were analyzed by direct sequencing.

Assessment of NS3/4A protease inhibitor-resistant variants.

The genome sequence of 609 nucleotides (203 amino acids) in the N terminal of the NS3 region of HCV isolates from the patients was examined. HCV RNA was extracted from 100 μl of blood serum sample, and the nucleotide sequences were determined by direct sequencing and deep sequencing. The primers used to amplify the NS3 region were NS3-F1 (5′-ACA CCG CGG CGT GTG GGG ACA T-3′, nucleotides 3295 to 3316) and NS3-AS2 (5′-GCT CTT GCC GCT GCC AGT GGG A-3′, nucleotides 4040 to 4019) as the first (outer) primer pair and NS3-F3 (5′-CAG GGG TGG CGG CTC CTT-3′, nucleotides 3390 to 3407) and NS3-AS2 as the second (inner) primer pair (18). Thirty-five cycles of first and second amplifications were performed as follows: denaturation for 30 s at 95°C, annealing of primers for 1 min at 63°C, extension for 1 min at 72°C, and final extension at 72°C for 7 min. The PCR-amplified DNA was purified after agarose gel electrophoresis and then used for direct sequencing and ultradeep sequencing.

Patients were examined for NS3/4A protease inhibitor-resistant variants by direct sequencing at baseline and at the time of reelevation of viral loads. Furthermore, patients who did not have an SVR with the first course of triple therapy with telaprevir and received the second course of the triple therapy with telaprevir were analyzed for telaprevir-resistant variants by ultradeep sequencing at baseline and at the time of reelevation of viral loads. NS3/4A protease inhibitor-resistant variants included V36A/C/M/L/G, T54A/S, Q80K/R/H/G/L, R155K/T/I/M/G/L/S/Q, A156V/T/S/I/G, D168A/V/E/G/N/T/Y/H/I, and V170A. Telaprevir-resistant variants (at aa 36, aa 54, aa 155, aa 156, and aa 170) and TMC435-resistant variants (at aa 80, aa 155, and aa 168) were evaluated (19, 20).

Direct sequencing was analyzed by the Dye Terminator method. Dideoxynucleotide termination sequencing was performed with the BigDye deoxy terminator version 1.1 cycle sequencing kit (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) (18). The sequence data were deposited in GenBank. Also, ultradeep sequencing was performed using the Ion Personal Genome Machine (PGM) sequencer (Life Technologies). An Ion Torrent adapter-ligated library was prepared using an Ion Xpress Plus fragment library kit (Life Technologies). Briefly, 100 ng of fragmented genomic DNA was ligated to the Ion Torrent adapters P1 and A. The adapter-ligated products were nick translated and PCR amplified for a total of 8 cycles. Subsequently, the library was purified using AMPure beads (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA) and the concentration determined using the StepOnePlus real-time PCR (Life Technologies) and Ion Library quantitation kit, according to the instructions provided by the manufacturers. Emulsion PCR was performed using the Ion OneTouch (Life Technologies) in conjunction with the Ion OneTouch 200 template kit version 2 (Life Technologies). Enrichment for templated Ion Sphere particles (ISPs) was performed using the Ion OneTouch enrichment system (Life Technologies) according to the instructions provided by the manufacturer. Templated ISPs were loaded onto an Ion 314 chip and subsequently sequenced using 130 sequencing cycles according to the Ion PGM 200 sequencing kit user guide. The total output read length per run was >10 Mb (0.5 million tags, 200-base read) (21). The results were analyzed with the CLC Genomics Workbench software (CLC bio, Aarhus, Denmark) (22).

We also included a control experiment to validate the error rates in ultradeep sequencing of the viral genome. In this study, the amplification products of the second-round PCR were ligated with a plasmid and transformed in Escherichia coli by using a cloning kit (TA Cloning; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). A plasmid-derived NS3 sequence was determined as the template, in a control experiment. The fold coverages evaluated per position for aa 36, aa 54, aa 155, aa 156, and aa 170 in the NS3 region were 359,379×, 473,716×, 106,435×, 105,979×, and 49,058×, respectively. Thus, using the control experiment based on a plasmid carrying the HCV NS3 sequence, amino acid mutations were defined as amino acid substitutions at a frequency of >0.2% among the total coverage. This frequency ruled out putative errors caused by the ultradeep sequence platform used in this study (23).

Statistical analysis.

Nonparametric variables were compared between the groups by the chi-square and Fisher's exact probability tests. Univariate and multivariate analyses for factors affecting the presence of telaprevir-resistant variants by direct sequencing at the reelevation of viral load were performed by the chi-square test and logistic regression, respectively. Patients who achieved an SVR were said to have no detection of resistant variants at the reelevation of viral load. The sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV) were calculated to determine the reliability of the predictors of the response to therapy.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The N-terminal sequences of the NS3 regions of the telaprevir-resistant variant isolates were deposited in GenBank under accession numbers AB709241, AB709263, AB709264, AB709276, AB709279, AB709283, AB709286, AB709289, AB709295, AB709296, AB709300, AB709303, AB709307, AB709310, AB709311, AB709312, AB709317, AB709319, AB709321, AB709322, AB709345, AB709348, AB709352, AB709353, AB709354, AB709356, AB709357, AB709358, AB709360, AB709370, AB709377, AB709382, AB709383, AB709384, AB709388, AB709390, AB709392, AB709396, AB709398, AB709399, AB709401, AB709405, AB709409, AB709410, AB709414, AB709418, AB709422, AB709426, AB709437, AB709444, AB709445, AB709451, AB709456, AB709461, AB709474, AB709476, AB709481, AB709484, AB709485, AB709486, AB709488, AB709489, AB709490, AB709491, AB709492, AB709493, AB709502, AB709507, AB709508, AB709514, AB709515, AB709525, AB709526, AB709527, and AB826566 to AB826684.

RESULTS

Virological response to therapy.

An analysis of the entire group showed that 76% (192 of 252 patients) achieved an SVR. According to the treatment regimen, an SVR was achieved by 45% (9 of 20 patients) and 79% (183 of 232 patients) of the T12PR12 and T12PR24 groups, respectively. Taking into consideration the response to prior treatment, an SVR was achieved by 86% (68 of 79 patients), 84% (91 of 109 patients), and 35% (32 of 63 patients) of the treatment-naive patients, patients who showed relapse following prior treatment, and nonresponders to prior treatment, respectively. In the 231 patients of the T12PR24 group, an SVR was achieved by 88% (61 of 69 patients), 85% (89 of 105 patients), and 56% (32 of 57 patients) of the treatment-naive patients, patients who showed relapse following prior treatment, and nonresponders to prior treatment, respectively. Furthermore, an SVR was achieved by 86% (12 of 14 patients) and 47% (20 of 43 patients) of the nonresponders to prior IFN monotherapy and ribavirin combination therapy, respectively.

NS3/4A protease inhibitor-resistant variants detected by direct sequencing at baseline and at the time of reelevation of viral loads.

All of the 252 patients were evaluated for resistant variants by direct sequencing at baseline. Sixty patients who did not achieve an SVR were also analyzed for resistant variants by direct sequencing at the time of reelevation of viral load. One hundred ninety-two patients who achieved SVR were said to have no detection of resistant variants as determined by direct sequencing at the reelevation of viral load.

As a whole, the frequency of the subjects in whom telaprevir-resistant variants were detected increased from 5% (12 of 252 patients) at baseline to 18% (45 of 252 patients) at the time of reelevation of viral load. On the other hand, the frequency of the subjects in whom TMC435-resistant variants were detected decreased from 31% (78 of 252 patients) at baseline to 6% (14 of 252 patients) at the time of reelevation of viral load. Table 2 shows the frequencies of subjects in whom resistant variants were detected at baseline and at the time of reelevation of viral load per position for aa 36, aa 54, aa 80, aa 155, aa 156, aa 168, and aa 170 in the NS3 region.

TABLE 2.

Frequencies of the subjects in whom NS3/4A protease inhibitor-resistant variants were detected by direct sequencing at baseline and at the time of reelevation of viral loadsa

| Time of variant detection | % (n) by aa positionb: |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 36 | 54 | 80 | 155 | 156 | 168 | 170 | |

| Baseline | 0.4 (1) | 3 (7) | 22 (55) | 0.4 (1) | 0.8 (2) | 10 (26) | 0 (0) |

| Reelevation of viral load | 7 (18) | 12 (30) | 5 (11) | 0.4 (1) | 4 (10) | 1.2 (3) | 0.4 (1) |

NS3/4A protease inhibitor-resistant variants included V36A/C/M/L/G, T54A/S, Q80K/R/H/G/L, R155K/T/I/M/G/L/S/Q, A156V/T/S/I/G, D168A/V/E/G/N/T/Y/H/I, and V170A (19, 20).

The data represent the percentages (n) of patients in whom NS3/4A protease inhibitor-resistant variants were detected by direct sequencing. Patients who achieved a sustained virological response were said to have no detection of resistant variants by direct sequencing at the time of reelevation of the viral load.

Pretreatment factors associated with detection of telaprevir-resistant variants by direct sequencing at the time of reelevation of viral load.

Univariate analysis of the data of the entire group identified eight pretreatment factors that were significantly associated with the detection of telaprevir-resistant variants by direct sequencing at the time of reelevation of viral load: IL28B rs8099917 genotype (genotype non-TT) (P < 0.001), nonresponse to prior treatment (P < 0.001), PEG-IFN dose of <1.3 μg/kg (P = 0.001), detection of variants at aa 54 at baseline (P = 0.002), Gln70/His70 substitution of aa 70 (P = 0.003), gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT) level of ≥50 IU/liter (P = 0.006), leukocyte count of <5,000/mm3 (P = 0.026), and ribavirin dose of <8.0 mg/kg (P = 0.026). Multivariate analysis that included the above variables identified five pretreatment factors that were independently associated with the detection of telaprevir-resistant variants at the time of reelevation of viral load: PEG-IFN dose of <1.3 μg/kg (odds ratio [OR], 9.71; P < 0.001), IL28B rs8099917 genotype (genotype non-TT) (OR, 8.61; P < 0.001), detection of variants at aa 54 at baseline (OR, 33.4; P = 0.002), nonresponse to prior treatment (OR, 2.66, P = 0.018), and leukocyte count of <5,000/mm3 (OR, 2.46; P = 0.042) (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Multivariate analysis of factors associated with detection of telaprevir-resistant variants by direct sequencing at the reelevation of viral load, to telaprevir, peginterferon, and ribavirin triple therapy in patients infected with HCV genotype 1b

| Detection factors | Category | Odds ratio (95% CIa) | Pb |

|---|---|---|---|

| PEG-IFN-α2b dose (μg/kg) | ≥1.3 | 1 | |

| <1.3 | 9.71 (3.23–29.4) | <0.001 | |

| IL28B rs8099917 genotype | TT genotype | 1 | |

| Non-TT genotype | 8.61 (3.48–21.3) | <0.001 | |

| Variants of aa 54 at baseline | No detection | 1 | |

| Detection | 33.4 (3.77–295) | 0.002 | |

| Response to treatment | Naive or relapse | 1 | |

| Nonresponse | 2.66 (1.18–5.96) | 0.018 | |

| Leukocyte count (/mm3) | ≥5,000 | 1 | |

| <5,000 | 2.46 (1.03–5.85) | 0.042 |

CI, confidence interval.

Only variables that achieved statistical significance (P < 0.05) on multivariate logistic regression analysis are shown.

Prediction of treatment efficacy by the combination of response to prior treatment and presence of telaprevir-resistant variants by direct sequencing at baseline.

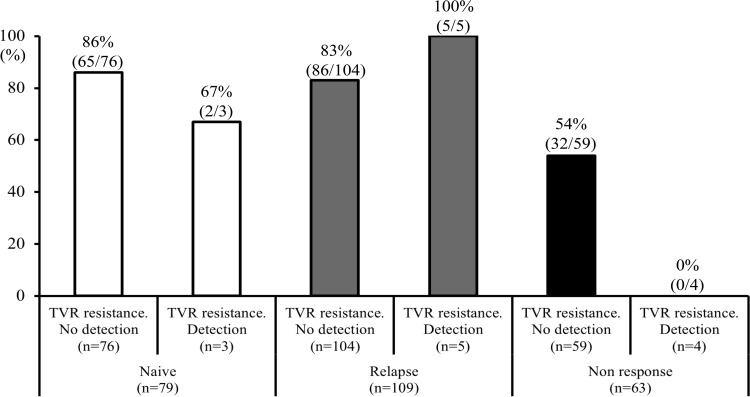

The SVR rates based on the combination of response to prior treatment and the presence of telaprevir-resistant variants by direct sequencing at baseline are shown in Fig. 1. In 79 treatment-naive patients, the SVR rates were not different between those patients in whom there were no detected telaprevir-resistant variants (86% [65 of 76 patients]) and those in whom variants were detected (67% [2 of 3 patients]). In 109 patients who showed relapse following prior treatment, the SVR rates were not different between those patients in whom there were no detected variants (83% [86 of 104 patients]) and those in whom variants were detected (100% [5 of 5 patients]). In contrast, in 63 patients who showed nonresponse to prior treatment, a higher proportion of patients with undetected telaprevir-resistant variants (54% [32 of 59 patients]) achieved an SVR than did patients in whom telaprevir-resistant variants were detected (0% [0 of 4 patients]) (P = 0.053). Thus, with the combination of nonresponse to prior treatment and detection of telaprevir-resistant variants, the sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV for those with non-SVR were 7% (4 of 60 patients), 100% (191 of 191 patients), 100% (4 of 4 patients), and 77% (191 of 247 patients), respectively. These results indicated that the use of the combination of the above two factors has high specificity and PPV for the prediction of a non-SVR.

FIG 1.

The rates of sustained virological response by the combination of response to prior treatment and presence of telaprevir (TVR)-resistant variants by direct sequencing at baseline are shown. Of those who showed nonresponse to prior treatment, a higher proportion of patients with undetected TVR-resistant variants (54%) achieved a sustained virological response than patients with detected TVR-resistant variants (0%) (P = 0.053).

Table 4 summarizes the profiles of 4 patients with nonresponse to prior treatment and in whom telaprevir-resistant variants were detected by direct sequencing at baseline. All of these 4 patients did not achieve an SVR with triple therapy. Interestingly, both T54S as a telaprevir-resistant variant and Q80L as a TMC435-resistant variant (19) were detected by direct sequencing at baseline.

TABLE 4.

Profiles of 4 patients with nonresponse to prior treatment and detection of telaprevir-resistant variants by direct sequencing at baseline

| Case no. | Sex | Age (yr) | Response to prior treatmenta | Amino acid detected at aa position: |

Time of HCV RNA-negative result during treatment (wks) | Efficacy of triple therapy | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 36 | 54 | 80 | 155 | 156 | 168 | 170 | ||||||

| 1 | Male | 70 | Nonresponse to IFN monotherapy | V | S | L | R | A | D | I | 2 | Non-SVR |

| 2 | Male | 47 | Nonresponse to IFN monotherapy | V | S | L | R | A | D | I | 4 | Non-SVR |

| 3 | Male | 61 | Nonresponse to RBV combination therapy | V | S | L | R | A | D | I | 3 | Non-SVR |

| 4 | Female | 60 | Nonresponse to RBV combination therapy | V | S | L | R | A | D | I | 4 | Non-SVR |

RBV, ribavirin.

Evolution of telaprevir-resistant variants over time as investigated by ultradeep sequencing in patients who received the second course of triple therapy.

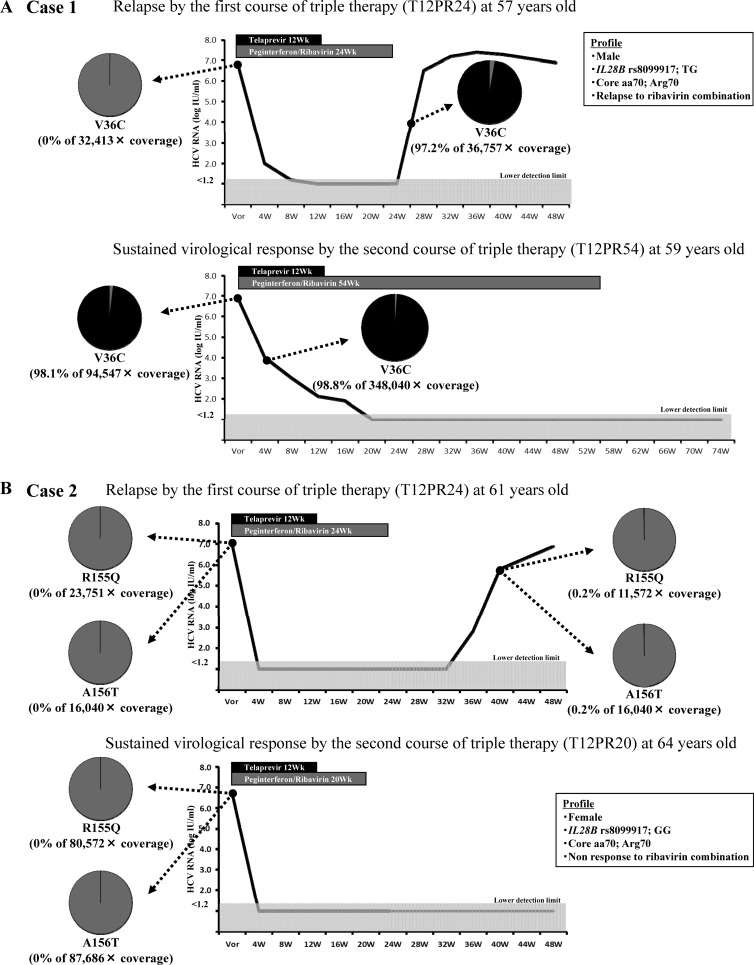

Two of 60 patients who did not achieve an SVR with the first course of triple therapy with telaprevir received the second course of triple therapy with telaprevir. They were analyzed for telaprevir-resistant variants by ultradeep sequencing at baseline and at the time of reelevation of viral loads.

Figure 2A shows the clinical course of case 1. In the first course of triple therapy with telaprevir (T12PR24) in a 57-year-old, V36C (0% of 32,413× coverage) was not detected by ultradeep sequencing at baseline of the first course, but very-high-frequency variants of V36C (97.2% of 36,757× coverage) were detected at the time of reelevation of viral loads. In the second course of triple therapy with telaprevir (T12PR54) when the patient was 59 years old, very-high-frequency variants of V36C (98.1% of 94,547× coverage) persisted at baseline of the second course, despite the passing of 2 years after cessation of the first therapy course. Case 1 achieved HCV RNA-negative status at 20 weeks after the start of the second course (late virological response), so PEG-IFN and ribavirin therapy was extended to 54 weeks. In conclusion, case 1 achieved an SVR after the second course of triple therapy with telaprevir, despite the persistence of very-high-frequency variants.

FIG 2.

Two patients who did not achieve a sustained virological response with the first course of triple therapy with telaprevir received the second course of the triple therapy with telaprevir. They were analyzed for telaprevir-resistant variants by ultradeep sequencing at baseline and at the time of reelevation of viral loads. (A) Case 1 achieved a sustained virological response with the second course of therapy despite the persistence of very-high-frequency variants. (B) Case 2 achieved a sustained virological response with the second course of therapy despite the history of the emergence of variants.

Figure 2B shows the clinical course of case 2. In the first course of triple therapy with telaprevir (T12PR24) in a 61-year-old patient, R155Q (0% of 23,751× coverage) and A156T (0% of 16,040× coverage) were not detected by ultradeep sequencing at baseline of the first course, but very-low-frequency variants of R155Q (0.2% of 11,572× coverage) and A156T (0.2% of 16,040× coverage) were detected at the time of reelevation of viral loads. In the second course of triple therapy with telaprevir (T12PR20) when the patient was 64 years old, R155Q (0% of 80,572× coverage) and A156T (0% of 87,686× coverage) were not detected by ultradeep sequencing at baseline of the second course, which was 2 years after cessation of the first course. In conclusion, case 2 achieved an SVR by the second course of triple therapy with telaprevir, despite the history of the emergence of variants.

DISCUSSION

Patients who fail to achieve an SVR to triple therapy need to be identified to avoid unnecessary side effects, high costs, and the emergence of telaprevir-resistant variants. Host genetic factors (e.g., IL28B genotype), and viral factors (e.g., amino acid substitutions in the core/NS5A region) have often been used as pretreatment predictors of poor virological response to PEG-IFN–ribavirin dual therapy (9–11, 15, 17) and telaprevir–PEG-IFN–ribavirin triple therapy (24–26). However, the pretreatment factors associated with the detection of telaprevir-resistant variants at the time of reelevation of viral load are still unknown. The present study identified that the detection of telaprevir-resistant variants at the time of reelevation of viral load can be predicted by a combination of host (IL28B rs8099917 genotype and leukocyte count), viral (variants of aa 54 at baseline), and treatment factors (PEG-IFN dose). All of the 4 patients with nonresponse to prior treatment and in whom telaprevir-resistant variants were detected at baseline did not achieve an SVR with triple therapy, and the use of the combination of nonresponse to prior treatment and the detection of telaprevir-resistant variants at baseline had high specificity and PPV for the prediction of a non-SVR. This finding suggests that there is a complex relationship between host susceptibility to IFN and viral sensitivity to NS3/4A protease inhibitors in determining treatment efficacy. Interestingly, in all of the 4 patients, both T54S as a telaprevir-resistant variant and Q80L as a TMC435-resistant variant (19) were detected by direct sequencing at baseline. This result suggests that patients with the above two factors should be carefully introduced to NS3/4A protease inhibitors besides telaprevir because of the high risk of the emergence of resistant variants. However, the present study was performed with a small number of patients, so further studies based on a larger number of patients should be performed.

In the present study employing ultradeep sequencing technology, 2 patients who did not achieve an SVR with the first course of triple therapy with telaprevir received the second course of the triple therapy with telaprevir. They achieved an SVR with the second course, despite the persistence of very-high-frequency variants (case 1, 98.1% for V36C) or a history of the emergence of variants (case 2, 0.2% for R155Q and 0.2% for A156T) as determined by ultradeep sequencing. This finding may be due to one or more reasons. One reason is probably related to the high susceptibility of telaprevir-resistant variants to IFN. One previous study indicated that mice infected with the resistant strain (A156F [99.9%]) developed only low-level viremia, and the virus was successfully eliminated with IFN therapy (27). In the other clinical report, telaprevir-resistant variants that emerged during 24-week telaprevir monotherapy were eliminated by the combination therapy of PEG-IFN plus ribavirin (28). Furthermore, this finding probably suggests that a small number of mutant-type viral RNAs may be incomplete or defective, since a large proportion of viral genomes are thought to be defective due to their high replication and mutation rates (29). Further studies employing ultradeep sequencing should be performed to evaluate whether a history of the emergence of NS3/4A protease inhibitor-resistant variants, besides telaprevir-resistant variants, affects the efficacy of a second course of NS3/4A protease inhibitor-based treatment.

The results of the present study should be interpreted with caution, since the study was performed with a small number of Japanese patients infected with HCV-1b. Any generalization of the results should await confirmation by a multicenter randomized trial based on a larger number of patients, including patients of other races and those infected with HCV-1a. Furthermore, the other limitation of the present study is that the loss of telaprevir-resistant variants was not investigated long after the cessation of therapy. Further large-scale studies should be performed to investigate the impacts of telaprevir-resistant variants on the response to treatment using new drugs, including direct-acting antiviral agents.

In conclusion, this study based on Japanese patients infected with HCV-1b indicates that telaprevir-resistant variants at the time of reelevation of viral load can be predicted by a combination of host, viral, and treatment factors. In those patients with no response to prior treatment, the present results suggest that telaprevir-resistant variants at baseline might partly affect the efficacy of triple therapy treatment. This finding indicates the clinical utility of detecting telaprevir-resistant variants to predict treatment efficacy, and it suggests a complex relationship between host susceptibility to IFN and viral sensitivity to NS3/4A protease inhibitors in determining treatment efficacy. Further large-scale prospective studies are needed to investigate the clinical usefulness of telaprevir-resistant variants and to develop more effective therapeutic regimens in patients infected with HCV-1.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported in part by a grant-in-aid from the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare, Japan.

Norio Akuta received honoraria from MSD K.K. and Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma and holds a right for royalty from SRL, Inc. Hiromitsu Kumada received honoraria from MSD K.K., Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, Dainippon Sumitomo Pharma, and Bristol-Myers Squibb and holds a right for royalty from SRL, Inc. The other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 6 November 2013

REFERENCES

- 1.Lin C, Kwong AD, Perni RB. 2006. Discovery and development of VX-950, a novel, covalent, and reversible inhibitor of hepatitis C virus NS3.4A serine protease. Infect. Disord. Drug Targets 6:3–16. 10.2174/187152606776056706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McHutchison JG, Everson GT, Gordon SC, Jacobson IM, Sulkowski M, Kauffman R, McNair L, Alam J, Muir AJ, PROVE1 Study Team 2009. Telaprevir with peginterferon and ribavirin for chronic HCV genotype 1 infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 360:1827–1838. 10.1056/NEJMoa0806104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hézode C, Forestier N, Dusheiko G, Ferenci P, Pol S, Goeser T, Bronowicki JP, Bourlière M, Gharakhanian S, Bengtsson L, McNair L, George S, Kieffer T, Kwong A, Kauffman RS, Alam J, Pawlotsky JM, Zeuzem S, PROVE2 Study Team 2009. Telaprevir and peginterferon with or without ribavirin for chronic HCV infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 360:1839–1850. 10.1056/NEJMoa0807650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kumada H, Toyota J, Okanoue T, Chayama K, Tsubouchi H, Hayashi N. 2012. Telaprevir with peginterferon and ribavirin for treatment-naive patients chronically infected with HCV of genotype 1 in Japan. J. Hepatol. 56:78–84. 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.07.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McHutchison JG, Manns MP, Muir AJ, Terrault NA, Jacobson IM, Afdhal NH, Heathcote EJ, Zeuzem S, Reesink HW, Garg J, Bsharat M, George S, Kauffman RS, Adda N, Di Bisceglie AM, PROVE3 Study Team 2010. Telaprevir for previously treated chronic HCV infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 362:1292–1303. 10.1056/NEJMoa0908014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lin C, Gates CA, Rao BG, Brennan DL, Fulghum JR, Luong YP, Frantz JD, Lin K, Ma S, Wei YY, Perni RB, Kwong AD. 2005. In vitro studies of cross-resistance mutations against two hepatitis C virus serine protease inhibitors, VX-950 and BILN 2061. J. Biol. Chem. 280:36784–36791. 10.1074/jbc.M506462200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kieffer TL, Sarrazin C, Miller JS, Welker MW, Forestier N, Reesink HW, Kwong AD, Zeuzem S. 2007. Telaprevir and pegylated interferon-alpha-2a inhibit wild-type and resistant genotype 1 hepatitis C virus replication in patients. Hepatology 46:631–639. 10.1002/hep.21781 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sullivan JC, De Meyer S, Bartels DJ, Dierynck I, Zhang EZ, Spanks J, Tigges AM, Ghys A, Dorrian J, Adda N, Martin EC, Beumont M, Jacobson IM, Sherman KE, Zeuzem S, Picchio G, Kieffer TL. 2013. Evolution of treatment-emergent resistant variants in telaprevir phase 3 clinical trials. Clin. Infect. Dis. 57:221–229. 10.1093/cid/cit226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ge D, Fellay J, Thompson AJ, Simon JS, Shianna KV, Urban TJ, Heinzen EL, Qiu P, Bertelsen AH, Muir AJ, Sulkowski M, McHutchison JG, Goldstein DB. 2009. Genetic variation in IL28B predicts hepatitis C treatment-induced viral clearance. Nature 461:399–401. 10.1038/nature08309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Suppiah V, Moldovan M, Ahlenstiel G, Berg T, Weltman M, Abate ML, Bassendine M, Spengler U, Dore GJ, Powell E, Riordan S, Sheridan D, Smedile A, Fragomeli V, Müller T, Bahlo M, Stewart GJ, Booth DR, George J. 2009. IL28B is associated with response to chronic hepatitis C interferon-alpha and ribavirin therapy. Nat. Genet. 41:1100–1104. 10.1038/ng.447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tanaka Y, Nishida N, Sugiyama M, Kurosaki M, Matsuura K, Sakamoto N, Nakagawa M, Korenaga M, Hino K, Hige S, Ito Y, Mita E, Tanaka E, Mochida S, Murawaki Y, Honda M, Sakai A, Hiasa Y, Nishiguchi S, Koike A, Sakaida I, Imamura M, Ito K, Yano K, Masaki N, Sugauchi F, Izumi N, Tokunaga K, Mizokami M. 2009. Genome-wide association of IL28B with response to pegylated interferon-alpha and ribavirin therapy for chronic hepatitis C. Nat. Genet. 41:1105–1109. 10.1038/ng.449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ohnishi Y, Tanaka T, Ozaki K, Yamada R, Suzuki H, Nakamura Y. 2001. A high-throughput SNP typing system for genome-wide association studies. J. Hum. Genet. 46:471–477. 10.1007/s100380170047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Suzuki A, Yamada R, Chang X, Tokuhiro S, Sawada T, Suzuki M, Nagasaki M, Nakayama-Hamada M, Kawaida R, Ono M, Ohtsuki M, Furukawa H, Yoshino S, Yukioka M, Tohma S, Matsubara T, Wakitani S, Teshima R, Nishioka Y, Sekine A, Iida A, Takahashi A, Tsunoda T, Nakamura Y, Yamamoto K. 2003. Functional haplotypes of PADI4, encoding citrullinating enzyme peptidylarginine deiminase 4, are associated with rheumatoid arthritis. Nat. Genet. 34:395–402. 10.1038/ng1206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kato N, Hijikata M, Ootsuyama Y, Nakagawa M, Ohkoshi S, Sugimura T, Shimotohno K. 1990. Molecular cloning of the human hepatitis C virus genome from Japanese patients with non-A, non-B hepatitis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 87:9524–9528. 10.1073/pnas.87.24.9524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Akuta N, Suzuki F, Sezaki H, Suzuki Y, Hosaka T, Someya T, Kobayashi M, Saitoh S, Watahiki S, Sato J, Matsuda M, Kobayashi M, Arase Y, Ikeda K, Kumada H. 2005. Association of amino acid substitution pattern in core protein of hepatitis C virus genotype 1b high viral load and non-virological response to interferon-ribavirin combination therapy. Intervirology 48:372–380. 10.1159/000086064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Enomoto N, Sakuma I, Asahina Y, Kurosaki M, Murakami T, Yamamoto C, Ogura Y, Izumi N, Marumo F, Sato C. 1996. Mutations in the nonstructural protein 5A gene and response to interferon in patients with chronic hepatitis C virus 1b infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 334:77–81. 10.1056/NEJM199601113340203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.El-Shamy A, Nagano-Fujii M, Sasase N, Imoto S, Kim SR, Hotta H. 2008. Sequence variation in hepatitis C virus nonstructural protein 5A predicts clinical outcome of pegylated interferon/ribavirin combination therapy. Hepatology 48:38–47. 10.1002/hep.22339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Suzuki F, Sezaki H, Akuta N, Suzuki Y, Seko Y, Kawamura Y, Hosaka T, Kobayashi M, Saito S, Arase Y, Ikeda K, Kobayashi M, Mineta R, Watahiki S, Miyakawa Y, Kumada H. 2012. Prevalence of hepatitis C virus variants resistant to NS3 protease inhibitors or the NS5A inhibitor (BMS-790052) in hepatitis patients with genotype 1b. J. Clin. Virol. 54:352–354. 10.1016/j.jcv.2012.04.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Romano KP, Ali A, Royer WE, Schiffer CA. 2010. Drug resistance against HCV NS3/4A inhibitors is defined by the balance of substrate recognition versus inhibitor binding. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107:20986–20991. 10.1073/pnas.1006370107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barbotte L, Ahmed-Belkacem A, Chevaliez S, Soulier A, Hézode C, Wajcman H, Bartels DJ, Zhou Y, Ardzinski A, Mani N, Rao BG, George S, Kwong A, Pawlotsky JM. 2010. Characterization of V36C, a novel amino acid substitution conferring hepatitis C virus (HCV) resistance to telaprevir, a potent peptidomimetic inhibitor of HCV protease. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54:2681–2683. 10.1128/AAC.01796-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Elliott AM, Radecki J, Moghis B, Li X, Kammesheidt A. 2012. Rapid detection of the ACMG/ACOG-recommended 23 CFTR disease-causing mutations using ion torrent semiconductor sequencing. J. Biomol. Tech. 23:24–30. 10.7171/jbt.12-2301-003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vogel U, Szczepanowski R, Claus H, Jünemann S, Prior K, Harmsen D. 2012. Ion torrent personal genome machine sequencing for genomic typing of Neisseria meningitidis for rapid determination of multiple layers of typing information. J. Clin. Microbiol. 50:1889–1894. 10.1128/JCM.00038-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Akuta N, Suzuki F, Seko Y, Kawamura Y, Sezaki H, Suzuki Y, Hosaka T, Kobayashi M, Hara T, Kobayashi M, Saitoh S, Arase Y, Ikeda K, Kumada H. 2013. Emergence of telaprevir-resistant variants detected by ultradeep sequencing after triple therapy in patients infected with HCV genotype 1. J. Med. Virol. 85:1028–1036. 10.1002/jmv.23579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Akuta N, Suzuki F, Hirakawa M, Kawamura Y, Yatsuji H, Sezaki H, Suzuki Y, Hosaka T, Kobayashi M, Kobayashi M, Saitoh S, Arase Y, Ikeda K, Chayama K, Nakamura Y, Kumada H. 2010. Amino acid substitution in hepatitis C virus core region and genetic variation near the interleukin 28B gene predict viral response to telaprevir with peginterferon and ribavirin. Hepatology 52:421–429. 10.1002/hep.23690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chayama K, Hayes CN, Abe H, Miki D, Ochi H, Karino Y, Toyota J, Nakamura Y, Kamatani N, Sezaki H, Kobayashi M, Akuta N, Suzuki F, Kumada H. 2011. IL28B but not ITPA polymorphism is predictive of response to pegylated interferon, ribavirin, and telaprevir triple therapy in patients with genotype 1 hepatitis C. J. Infect. Dis. 204:84–93. 10.1093/infdis/jir210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Akuta N, Suzuki F, Fukushima T, Kawamura Y, Sezaki H, Suzuki Y, Hosaka T, Kobayashi M, Hara T, Kobayashi M, Saitoh S, Arase Y, Ikeda K, Kumada H. 2013. Prediction of treatment efficacy and telaprevir-resistant variants after triple therapy in patients infected with hepatitis C virus genotype 1. J. Clin. Microbiol. 51:2862–2868. 10.1128/JCM.01129-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hiraga N, Imamura M, Abe H, Hayes CN, Kono T, Onishi M, Tsuge M, Takahashi S, Ochi H, Iwao E, Kamiya N, Yamada I, Tateno C, Yoshizato K, Matsui H, Kanai A, Inaba T, Tanaka S, Chayama K. 2011. Rapid emergence of telaprevir resistant hepatitis C virus strain from wild type clone in vivo. Hepatology 54:781–788. 10.1002/hep.24460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ozeki I, Akaike J, Karino Y, Arakawa T, Kuwata Y, Ohmura T, Sato T, Kamiya N, Yamada I, Chayama K, Kumada H, Toyota J. 2011. Antiviral effects of peginterferon alpha-2b and ribavirin following 24-week monotherapy of telaprevir in Japanese hepatitis C patients. J. Gastroenterol. 46:929–937. 10.1007/s00535-011-0411-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bartenschlager R, Lohmann V. 2000. Replication of hepatitis C virus. J. Gen. Virol. 81:1631–1648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]