Abstract

TFIIB-related factor Brf1 is essential for RNA polymerase (Pol) III recruitment and open-promoter formation in transcription initiation. We site specifically incorporated a nonnatural amino acid cross-linker into Brf1 to map its protein interaction targets in the preinitiation complex (PIC). Our cross-linking analysis in the N-terminal domain of Brf1 indicated a pattern of multiple protein interactions reminiscent of TFIIB in the Pol active-site cleft. In addition to the TFIIB-like protein interactions, the Brf1 cyclin repeat subdomain is in contact with the Pol III-specific C34 subunit. With site-directed hydroxyl radical probing, we further revealed the binding between Brf1 cyclin repeats and the highly conserved region connecting C34 winged-helix domains 2 and 3. In contrast to the N-terminal domain of Brf1, the C-terminal domain contains extensive binding sites for TBP and Bdp1 to hold together the TFIIIB complex on the promoter. Overall, the domain architecture of the PIC derived from our cross-linking data explains how individual structural subdomains of Brf1 integrate the protein network from the Pol III active center to the promoter for transcription initiation.

INTRODUCTION

Eukaryotic RNA polymerase (Pol) III transcribes precursor tRNAs, 5S rRNA, small nuclear RNAs such as U6 and 7SK RNAs, and a number of small nucleolar RNAs and microRNAs (1). In the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, the Pol III transcription apparatus consists of 17-subunit Pol III and three other transcription factors: single-polypeptide TFIIIA, three-subunit TFIIIB, and six-subunit TFIIIC (2, 3). TFIIIA and TFIIIC function as the promoter recognition factors, and TFIIIB is recruited to the promoter through TFIIIC. TFIIIB is composed of TFIIB-related factor Brf1, TATA box binding protein TBP, and SANT domain-containing subunit Bdp1. Previous biochemical studies indicated that Brf1 and TBP cooperatively assemble onto DNA upstream of the transcription start site and Bdp1 binds to the Brf1-TBP-DNA complex mainly through its SANT domain (4–10). The TFIIIB-DNA assembly is required for subsequent Pol III recruitment and transcript initiation. Both Brf1 and Bdp1 have been found to interact with Pol III and function in promoter opening (4, 11–14).

The N-terminal domain of yeast Brf1 (Brf1n; amino acids [aa] 1 to 286) contains a zinc ribbon fold (aa 3 to 34) and a cyclin fold repeat subdomain (aa 83 to 282) (Fig. 1A), both of which are homologous to those in the general transcription factor TFIIB of the Pol II system. On the basis of biochemical and structural analyses, TFIIB ribbon and cyclin fold repeats are, respectively, positioned in the RNA exit tunnel and in the wall domain of Pol II (15–20). In addition, the connecting region between the TFIIB ribbon and the cyclin repeat domain has been structurally resolved to contain B reader and B linker motifs that interact with the Pol active center. On the basis of sequence comparison, the connecting region in Brf1n, which we refer to as the N linker, contains low sequence homology with TFIIB. However, this region might also contribute to the binding of the Pol active center, as previous genetic analyses revealed the involvement of the ribbon and N linker in open-complex formation (11, 13).

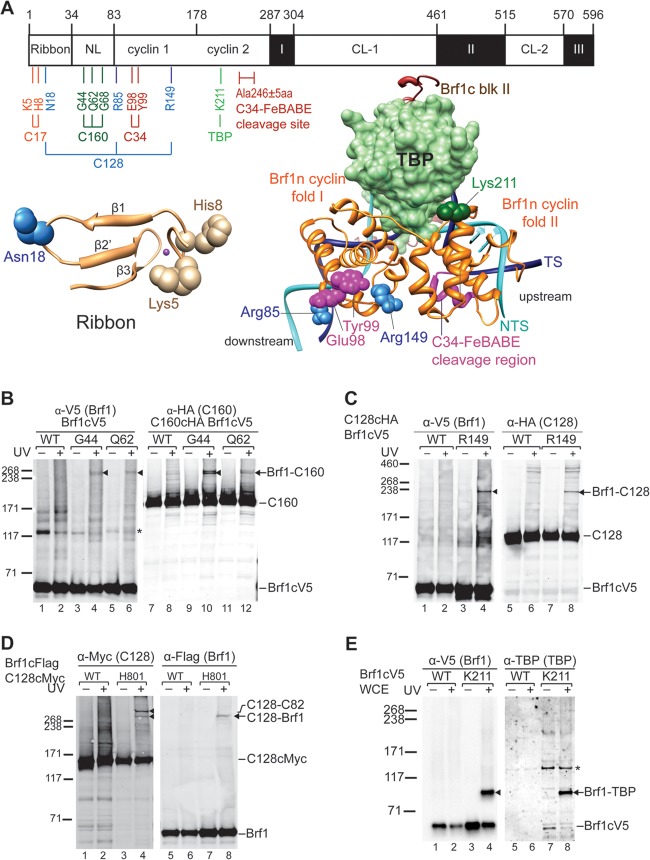

FIG 1.

Brf1n BPA photo-cross-linking. (A) Schematic of Brf1 domain architecture and summary of Brf1n BPA photo-cross-linking. Residue positions of the boundaries of individual subdomains are shown at the top. NL, N linker; CL-1 and CL-2, C linkers 1 and 2, respectively. BPA-substituted residues are color coded according to the respective cross-linked polypeptides indicated below the horizontal connecting lines. Below the schematic are models of the ribbon fold (left) and the Brf1c homology block II-TBP-DNA complex (right). The magenta sphere in the ribbon model represents the zinc ion. TBP is displayed as a molecular-surface model in light green. Others are shown as backbone traces with Brf1c homology block II in brown, Brf1n cyclin folds in orange, template DNA (TS) in dark blue, and nontemplate DNA (NTS) in cyan. BPA-substituted residues with confirmed cross-linking targets are shown as spheres. The C34-FeBABE hydroxyl radical cleavage site (Ala246 ± 5 aa) in Brf1n is indicated. (B) Western analysis of Brf1-C160 photo-cross-linking. BPA-substituted residues are indicated above the lanes. Brf1-C160 cross-linking was identified with anti-V5 antibodies (Brf1) (lanes 1 to 6) and confirmed with anti-HA antibodies (C160) (lanes 7 to 12), respectively. Triangles are placed next to the cross-linking gel bands. All cross-linking bands in subsequent figures are marked by triangles. UV + or −, with or without UV irradiation, respectively; WT, WT Brf1 with no BPA replacement; *, nonspecific background band. (C) Brf1-C128 photo-cross-linking. The Brf1-C128 cross-linking band was visualized with anti-V5 antibody (Brf1) (lanes 1 to 4) and confirmed with anti-HA antibody (C128) (lanes 5 to 8). (D) C128-Brf1 photo-cross-linking. The C128-Brf1 cross-linking band was visualized with anti-Myc antibody (C128) (lanes 1 to 4) and confirmed with anti-Flag antibody (Brf1) (lanes 5 to 8). The BPA position in C128 additionally cross-links to C82. (E) Brf1-TBP photo-cross-linking at BPA-substituted residue Lys211 in the second cyclin fold of Brf1. Cross-linked Brf1-TBP was probed with anti-V5 antibody (Brf1) (lanes 1 to 4) and confirmed by anti-TBP antibody (lanes 5 to 8). The values to the left of panels C to E are molecular sizes in kilodaltons.

The C-terminal half of Brf1 (Brf1c) is Pol III specific and is not conserved among the members of the TFIIB family, which, in addition to Brf1 and TFIIB, also includes Rrn7 (TAF1B in humans) in the Pol I system (21–24). Yeast Brf1c (aa 287 to 596) contains three homologous sequence blocks, I (aa 287 to 304), II (aa 461 to 515), and III (aa 570 to 596) (Fig. 1A), that are conserved in S. cerevisiae, Schizosaccharomyces pombe, Candida albicans, Kluyveromyces lactis, and Homo sapiens (22, 25). Brf1c exists mostly as a scaffold that holds together the three TFIIIB subunits (12, 26). In particular, structural analysis of the Brf1-TBP-DNA complex indicated that homology block II is positioned along the convex and lateral surfaces of TBP and that the block also interacts with Bdp1 (5, 6, 10, 22, 26–28). The homology blocks are separated by two nonconserved connecting regions that we refer to as C linkers 1 and 2 (Fig. 1A).

Previous genetic and pairwise protein-protein interaction analyses have identified Brf1-interacting partners. In addition to TBP and Bdp1 of the TFIIIB complex, Brf1 interacts with the τ131 (Tfc4) subunit of TFIIIC and two of the Pol III subunits, C34 and C17 (29–33). However, most of the previous studies involved large protein fragments of Brf1 and a detailed and more precise characterization of the Brf1 protein network is not yet available. In this study, we site specifically incorporated a nonnatural photoreactive amino acid, p-benzoyl-l-phenylalanine (BPA), into yeast Brf1 to map protein-protein interactions within the Pol III preinitiation complex (PIC). BPA incorporated in the amino acid sequence of Brf1n revealed cross-linking with TBP and the C160 and C128 subunits of the Pol III active-site cleft, as well as two smaller subunits, C34 and C17. The Brf1-C34 interaction was further analyzed by site-specific hydroxyl radical analysis, which revealed the connection between the Brf1 cyclin repeat subdomain and a conserved sequence C terminal to C34 winged-helix domain 2 (WH2). Our cross-linking results for Brf1c identified additional Bdp1 and TBP interactions in the C linker 1 region. Mutational analysis indicated that a Bdp1-binding block in C linker 1 is required for optimal cell growth and in vitro transcription activity. Overall, our work provides precise mapping of the network of protein-protein interactions for Brf1 and further elucidates the domain architecture of the Pol III PIC.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Yeast strains and plasmids.

The yeast strains used in this study were derived from BY4705 with chromosomal disruptions of individual genes by the KanMX4 cassette, yielding Brf1 shuffle strain YSK1 [MATα ade2::his3G his3Δ200 leu2Δ met15Δ lys2Δ trp1Δ63 ura3Δ (brf1::KanMX4) Brf1-pRS316 (URA3+)] and C34 shuffle strain YLy3 [MATα ade2::his3G his3Δ200 leu2Δ met15Δ lys2Δ trp1Δ63 ura3Δ (Rpc34::KanMX4) Rpc34-pRS316 (URA3+)] (34, 35). Brf1 and Rpc34 (C34) were separately cloned into yeast 2μ vector pRS425 with a LEU2 selection marker (36). Both genes were driven by the yeast ADH1 promoter. Brf1 was either V5 or 13-Myc epitope tagged at the C terminus via the QuikChange II site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene), yielding plasmids pSK1 (Adh1-Brf1c V5-pRS425) and pSK2 (Adh1-Brf1c 13Myc-pRS425), respectively. C34 was C terminally V5 tagged, yielding pYL5 (Rpc34c V5-pRS425). Each of the constructed plasmids was used to generate individual mutant plasmids containing single TAG (amber) nonsense codon substitutions at the intended amino acid positions. To generate yeast strains for incorporation of the nonnatural amino acid BPA into Brf1 and C34, we used plasmid shuffling to transform individual amber plasmids into yeast YSK1 together with the plasmid pLH157 encoding the suppressor tRNACUA (corresponding to the TAG amber codon) and a BPA-tRNA synthetase (16, 37).

For a Brf1 mutagenesis study, the gene encoding Brf1, along with its endogenous promoter, was cloned into the vector pRS315 with a single hemagglutinin (HA) epitope tag at the C terminus, yielding pSK3 (Brf1-HA ars cen LEU2) (38). All Brf1 mutant plasmids were generated on the basis of pSK3, and the plasmids were transformed into the Brf1 shuffle strain to generate mutant strains by the 5-fluoroorotic acid dropout method. For cell growth assays, both the wild-type (WT) and mutant strains were grown in YPD to an optical density at 600 nm of 1.0 and the cell cultures were subsequently diluted 10−2, 10−4, and 10−6. The diluted cells were spotted onto synthetic complete glucose plates lacking leucine, and their growth phenotypes at 16, 25, 30, and 37°C were monitored. The incubation time for cell growth at 30 and 37°C was 3 days. Yeast whole-cell extract (WCE) was prepared for subsequent biochemical studies. Detailed procedures for the preparation of WCE from individual yeast strains with BPA incorporated or mutant yeast strains have been described previously (14, 39).

PIC isolation and BPA photo-cross-linking.

The Pol III PIC was isolated with the immobilized template (IMT) assay with yeast WCE and template DNA containing either the U6 snRNA or SUP4 tRNA promoter immobilized on streptavidin magnetic (DynaI) beads as previously described (14, 39). For the BPA photo-cross-linking experiment, 800 μg of WCE was incubated with 4 μg of template DNA immobilized on 200 μg of DynaI beads (Invitrogen) at 30°C for 30 min. Each reaction mixture was washed three times with transcription buffer containing 20 mM K · HEPES (pH 7.9), 80 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EDTA, 2% (vol/vol) glycerol, and 0.01% Tween 20. After washing, the reaction mixture was divided into two fractions, one that would receive UV irradiation and another that would serve as a control. UV irradiation was conducted with a total energy of 6,500 μJ/cm2 in a Spectrolinker XL-1500 UV oven (Spectronics). The samples were then resuspended in NuPAGE sample buffer (Invitrogen) for SDS-PAGE and Western analysis. The Western blot was visualized with the LICOR Odyssey infrared imaging system with fluorescent-dye-labeled secondary antibodies.

In vitro transcription.

In vitro transcription was conducted with the IMT assay as described above. After washing, the isolated PICs were resuspended in 17 μl of transcription buffer containing 200 ng α-amanitin, 4 U of RNase inhibitor (Promega), and 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT). A mixture of nucleoside triphosphates (3 μl) was subsequently added, and the resulting reaction mixture contained 500 μM (each) ATP, UTP, and CTP; 50 μM GTP; and 0.16 μM [α-32P]GTP (3,000 Ci/mmol). After the reaction had been allowed to proceed at 30°C for 30 min, transcription was quenched by the addition of 180 μl of 0.1 M sodium acetate, 10 mM EDTA, 0.5% SDS, and 200 μg/ml glycogen. The transcripts were extracted with phenol-chloroform and ethanol precipitated, separated by 6% (wt/vol) denaturing urea-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, and visualized by autoradiography. Transcriptional activity was restored by the addition of recombinant Brf1 (160 ng) to Brf1 mutant WCE.

IP.

Brf1 WT and mutant WCEs containing a Bdp1 C-terminal Flag tag and a Brf1 C-terminal HA tag were used for immunoprecipitation (IP). WCE (1 mg) was mixed with 50 μl of anti-Flag antibody–agarose beads (Sigma) in extract dialysis buffer containing 20 mM K · HEPES (pH 7.9), 100 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EDTA, and 20% glycerol and incubated overnight at 4°C. Following three washes with 500 μl of extract dialysis buffer, the bound proteins were eluted by boiling the beads at 95°C for 5 min in 20 μl of 4× NuPAGE buffer (Invitrogen). The eluted proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by Western blotting with anti-Flag (probe for Bdp1), anti-HA (probe for Brf1), anti-TBP, and anti-τ131 (Tfc4; TFIIIC subunit) antibodies.

C34 purification and FeBABE conjugation.

Expression and purification of C34 were done as described previously (39). To avoid off-target FeBABE [an EDTA-chelated iron atom linked to a sulfhydryl-reactive moiety or Fe(III) (s)-1-(p-bromoacetamidobenzyl)EDTA] conjugation, three endogenous cysteines were altered to noncysteine residues as follows: Cys124Ala, Cys244Ala, and Cys260Ser. All single-cysteine C34 variants were derived from noncysteine C34. FeBABE conjugation was performed as described previously (14).

Hydroxyl radical cleavage with C34-FeBABE conjugate.

Hydroxyl radical probing in the Pol III PIC was conducted on the basis of the previously established protocol with a C82 mutant WCE allowing dissociation of the C82/34/31 subcomplex from the Pol core (39). In an IMT reaction, 400 μg of yeast WCE containing C-terminally Flag3-tagged Brf1 and the Δ(50-52) C82 deletion mutant was incubated with 0.72 μg of recombinant C31, 2 μg of recombinant C82, and 0.94 μg of C34-FeBABE conjugate in a 200-μl reaction mixture containing 2 μg of SUP4 tRNA promoter template DNA. The PICs on beads were washed three times with transcription buffer. After washing, samples were resuspended in 7.5 μl of transcription buffer. The following reagents were added sequentially: 2.5 μl of 50% (vol/vol) glycerol, 1.25 μl of 50 mM sodium ascorbate, and 1.25 μl of H2O2 mixture (0.24% [vol/vol] H2O2, 10 mM EDTA). The hydroxyl radical cleavage reaction was conducted at 30°C for 8 min and quenched by the addition of 4.5 μl of NuPAGE lithium dodecyl sulfate sample buffer (Invitrogen) and 1 μl of 1 M DTT. The protein cleavage sites in Brf1 were determined on the basis of the method described previously (14). In vitro transcription analysis was also conducted in parallel. The C34-FeBABE conjugates restored transcriptional activity similar to that of the WT (data not shown).

RESULTS

The Brf1 N-terminal domain interacts with Pol III in a mode similar to that of the TFIIB-Pol II complex.

To map the protein-protein interaction network of Brf1, we used the nonsense suppression method to incorporate BPA site specifically into the entire Brf1 sequence (37, 40). We generated individual yeast strains each containing a single TAG amber codon in the Brf1 coding sequence for BPA replacement at the designated amino acid positions. A total of 197 strains were created (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). We isolated yeast WCEs from these Brf1-BPA strains and conducted the IMT assay coupled with UV irradiation to allow site-specific photo-cross-linking in the isolated PICs. The cross-linking samples were subsequently subjected to SDS-PAGE and Western blotting analyses, and protein cross-links were determined on the basis of the appearance of additional low-mobility gel bands generated by UV irradiation. As demonstrated in the Western analysis (Fig. 1B), BPA substitution of residues Gly44 and Gln62 in the N linker region of Brf1 generated protein cross-links with a size of ∼240 kDa (Fig. 1B, lanes 4 and 6). By subtraction of the apparent molecular mass of Brf1, the polypeptide cross-linked to Brf1 was estimated to have a molecular mass in the range of 160 to 180 kDa. We confirmed this cross-linked polypeptide to be the largest subunit, C160, of Pol III by repeating the photo-cross-linking experiment with WCEs containing C-terminally HA-tagged C160 and probing with anti-HA antibody (Fig. 1B, lanes 10 and 12). Cross-linking to the second-largest subunit, C128, of Pol III was also observed for BPA substitution of residues Arg85 and Arg149 of the first cyclin fold and residue Asn18 of the ribbon fold (Fig. 1C; data not shown).

As summarized in Fig. 1A, Brf1-C160 and -C128 cross-links are distributed, respectively, in the N linker and ribbon/cyclin repeat subdomains. The cross-linking pattern suggests a TFIIB-like binding mode as in the Pol II-TFIIB structural model (20). In the Pol II-TFIIB model, the linker region of TFIIB, including B reader and B linker motifs, are positioned in the Pol active center contacting the lid, rudder, and clamp coiled-coil motifs of Rpb1 (homologous to C160). In addition, the first cyclin fold of TFIIB is in close contact with the wall and protrusion domains of Rpb2 (homologous to C128), and the ribbon fold of TFIIB contacts both Rpb1 and Rpb2 in the RNA exit tunnel (16, 20). To further investigate this TFIIB-like binding mode, we conducted another BPA cross-linking analysis in the wall domain of C128. As demonstrated in Fig. 1D, a BPA substitution at His801 of the wall domain generated a cross-link with Brf1, supporting the localization of Brf1 on C128. Although further structural and biochemical analyses are required to determine the structural region of Brf1 in contact with the wall domain of C128, our combined photo-cross-linking results with BPA-substituted C128 and Brf1 suggest that the Brf1 N-terminal domain likely has a TFIIB-Pol II binding mode in the PIC.

In addition to cross-linking with the two largest subunits of Pol III, we also observed Brf1-C17 cross-linking of residues Lys5 and His8 in the zinc-binding knuckle of the ribbon domain (Fig. 1A; data not shown). Since C17 dimerizes with C25 to form the stalk subcomplex that localizes adjacent to the RNA exit tunnel (41), the Brf1-C17 cross-link suggests a potential functional link between Brf1 and the stalk in transcription initiation. Furthermore, we observed a Brf1-TBP cross-link at Lys211 of the H2′ helix of the second cyclin fold (Fig. 1A and E). This cross-link supports the structural model of the binding of cyclin fold repeats with the TBP-DNA complex where the loop between the H2′ and H3′ helices of the second cyclin fold interacts with the C-terminal stirrup and the C terminus of TBP (42).

The Brf1 cyclin fold repeat subdomain connects with C34 for Pol III recruitment.

Our BPA cross-linking analysis of Brf1n revealed subdomain-specific interactions with C160, C128, and TBP, suggesting that Brf1n organizes TFIIB-like domain architecture in the PIC. On the basis of previous studies with yeast two-hybrid and pulldown analyses, Brf1 also contains a Pol III system-specific interaction with the C34 subunit of the Pol III complex. However, the interaction site for C34 was not precisely mapped as the studies were involved either with the full-length Brf1 protein or with the cyclin fold repeats (aa 90 to 262) (22, 43). Consistent with the low-resolution protein mapping data, we observed weak cross-linking between Brf1 and the C34 subunit of Pol III at residue Tyr99 of the H2 helix in the first cyclin fold (Fig. 2A).

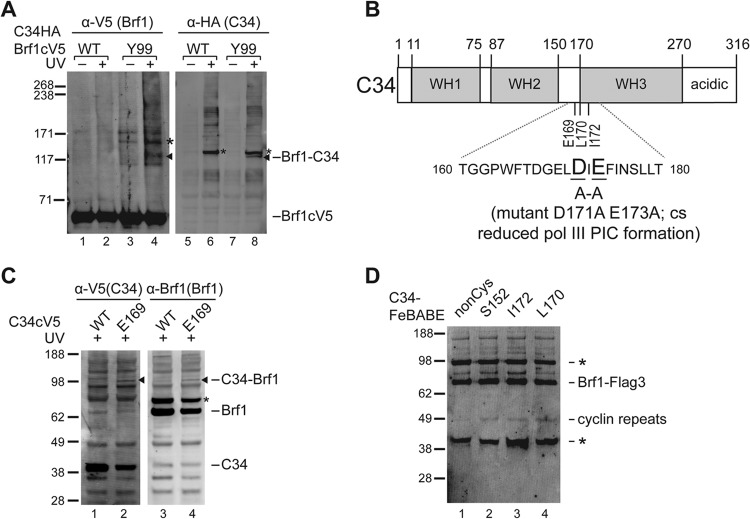

FIG 2.

Brf1n cyclin folds interact with C34. (A) Brf1-C34 photo-cross-linking from BPA substitution at residue Tyr99 of Brf1. Cross-linking was visualized with an antibody against V5 (Brf1) (left side) and verified with C34 antiserum (right side). Cross-linking bands are marked with triangles. The bands marked with asterisks are background bands, which appear to be UV specific. (B) Schematic of C34 domain architecture. As highlighted in the sequence of the connecting region between the WH2 and WH3 domains, Asp171 and Glu173 mutations affect transcription initiation. (C) Western analysis of C34-Brf1 cross-linking. BPA substitution is at residue Glu169 of C34. Cross-linking was visualized by probing with anti-V5 antibody (C34) (left side), and the identity of the C34-Brf1 cross-linking band was verified by probing with Brf1 antiserum (right side). The asterisk marks a nonspecific background band. (D) Determination of the C34-FeBABE hydroxyl radical cleavage site in Brf1. The hydroxyl radical cleavage peptide fragment was revealed with an anti-Flag antibody in the Western blot analysis shown, and the cleavage site was determined to be in the cyclin fold repeat subdomain of Brf1 as indicated. The noncysteine (nonCys) mutant form of C34 does not contain any cysteine residue for FeBABE conjugation and served as the negative control. Nonspecific bands are marked with asterisks. The values to the left of panels A, C, and D are molecular sizes in kilodaltons.

Our previous cross-linking analysis of Pol III identified intersubunit interactions that localize C34 N-terminal WH1 and WH2 above the Pol III active-center cleft and the C-terminal region beneath the Pol clamp domain (Fig. 2B). However, it remains unclear how C34 provides additional Pol III-Brf1 interaction for Pol III recruitment as indicated in previous studies (22, 29, 44). To address this, we incorporated BPA into C34 to map Brf1 binding sites. BPA substitution at Glu169, located in the connecting region between the WH2 domain and the predicted WH3 domain, resulted in weak cross-linking with Brf1 (Fig. 2C). Surprisingly, Glu169 is located near the Asp171-to-Glu173 amino acid stretch that is functionally important for Pol III recruitment (44).

To further characterize the C34-Brf1 interaction, we used site-directed hydroxyl radical analysis to probe the structural region of Brf1 near the C34 WH2-WH3 connecting region. We generated C34 single-cysteine mutants to conjugate the hydroxyl radical reagent FeBABE at amino acid positions Leu170 and Ile172. The FeBABE-conjugated C34 variants were subjected to the IMT assay for hydroxyl radical protein cleavage analysis in the PIC. In Fig. 2D, a Brf1 cleavage fragment was commonly generated by the C34-FeBABE conjugates (Fig. 2D, lanes 2 to 4). By comparison with the molecular weight ladder generated from in vitro-translated Brf1 peptide fragments, the cleavage site was determined to be in the H4′ helix of the Brf1n second cyclin fold. In summary, the combined cross-linking and hydroxyl radical analyses suggest an interaction between the WH2-WH3 connecting region of C34 and the cyclin fold repeats of Brf1n. As the biochemical probing results were weak, we suspect that C34 might not strongly interact with Brf1 in the PIC. However, as previous studies suggested that BPA is a less efficient cross-linking reagent because of its geometry requirement for hydrogen abstraction by benzophenone (45), the weak C34-Brf1 cross-linking seen could also be attributed to the poor cross-linking efficiency of BPA.

The Brf1 C-terminal domain contains extended Bdp1 and TBP binding regions.

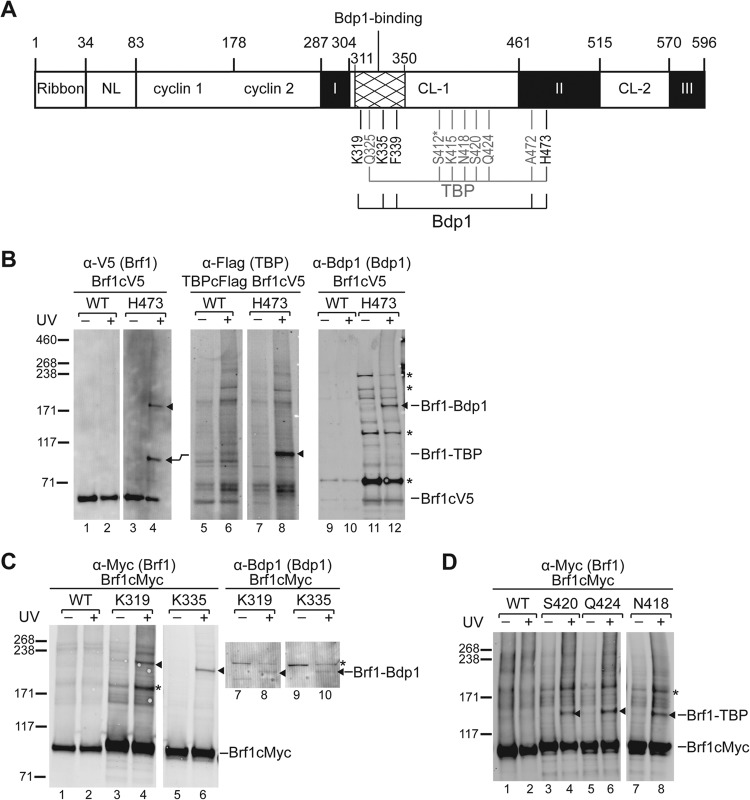

Homology block II of Brf1c serves as the dominant binding site for both TBP and Bdp1, and this block adopts a “vine-on-a-tree” conformation to interact with TBP from the convex surface to the lateral surface of the first structural repeat (6, 27, 28). Consistent with the protein interaction model, our BPA cross-linking analysis conducted in homology block II revealed cross-links with Bdp1 and TBP. As indicated in the summary of Brf1c cross-linking (Fig. 3A) and illustrated in Fig. 3B, BPA substitution at residue His473 generates two cross-links confirmed to be TBP and Bdp1, indicating simultaneous interactions with both proteins. Similar simultaneous cross-linking was also observed for BPA substitution of neighboring residue Ala472 (data not shown). In the homology block II-TBP-DNA ternary complex structure, His473 and Ala472 belong to helix H23, which interacts with the convex surface of the TBP first structural repeat. Our cross-linking results therefore further suggest the localization of Bdp1 on the TBP convex surface.

FIG 3.

BPA photo-cross-linking in Brf1c. (A) Summary of Brf1c BPA photo-cross-linking. (B) Western analysis of cross-linking for BPA substitution at His473 of Brf1. The cross-linking results were probed with anti-V5 antibody (Brf1) (left side), anti-Flag antibody (TBP) (middle), and anti-Bdp1 antibody (right side). The cross-linking bands are marked with triangles. The slight upward mobility shift of the Brf1-TBP cross-link in the middle assay was caused by the use of Flag epitope tagging in TBP. (C) Western analysis of Brf1-Bdp1 cross-linking at Lys319 and Lys335 in the C linker 1 region. The Western blot was probed with anti-Myc antibody for Myc epitope-tagged Brf1 and with an anti-Bdp1 antibody to confirm the Bdp1 polypeptide in the cross-linked fusion (lanes 8 and 10). (D) Western analysis of Brf1-TBP cross-linking after BPA substitution of residues Ser420, Gln424, and Asn418 of Brf1c. The values to the left of panels B to D are molecular sizes in kilodaltons.

Additional Bdp1 and TBP cross-links were also observed for BPA substitutions in the connecting region between homology blocks I and II, which we refer to as C linker 1. As shown in Fig. 3C and summarized in panel A, BPA incorporation at residues Lys319 and Lys335 generated Bdp1 cross-linking. In contrast to the Brf1-Bdp1 cross-links that are clustered closer to homology block I, Brf1-TBP cross-linking occurs at residues widely distributed in C linker 1 (Fig. 3D; summarized in panel A).

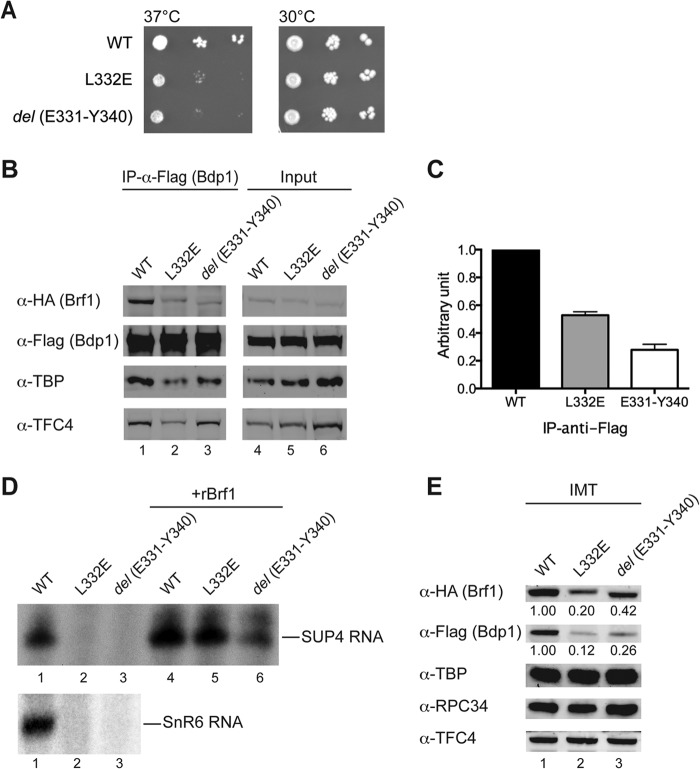

The Bdp1-binding block is important for transcription initiation.

On the basis of extensive TBP and Bdp1 interactions revealed by BPA cross-linking, we introduced a series of truncations and point mutations into Brf1c. Internal truncations and point mutations were initially introduced into homology block I, resulting in cell death. In contrast, most of the mutations in C linker 1 resulted in yeast strains without observable temperature-dependent growth defects. However, mutations in the Gln311-to-Arg350 sequence block, which provided multiple cross-linking with Bdp1 (Fig. 3A), conferred a temperature-sensitive growth phenotype. As demonstrated in Fig. 4A, the yeast strains with either a Leu332Glu point mutation or a del(Glu331-Tyr340) internal truncation showed slow cell growth at the nonpermissive temperature of 37°C. We isolated WCEs from these two mutant strains and conducted a coimmunoprecipitation assay to analyze Brf1-Bdp1 binding. As shown in Fig. 4B and C, both Brf1c mutations severely compromised binding with Bdp1, supporting our cross-link data. We further analyzed this newly identified Bdp1 binding block by in vitro transcription and PIC formation assays on the SUP4 template DNA. Both mutations severely compromised transcription activity (Fig. 4D, lanes 2 and 3). The mutations also caused reduced Bdp1 and Brf1 protein levels in the PICs isolated from the IMT assay (Fig. 4E, lanes 2 and 3), indicating that both mutations affect the stable association of Bdp1 and Brf1 in the PIC. Our results thus suggest that this Bdp1 binding block provides important structural support for the stabilization of Brf1 and Bdp1 in the PIC.

FIG 4.

Mutational analysis of Brf1c homology block I and C linker 1. (A) Cell growth phenotypes were analyzed by serial-dilution spot assay. Both the Leu332Glu and del(Glu331-Tyr340) mutants grew more slowly than the WT at 37°C. (B) Western blot analysis of coimmunoprecipitation for Brf1 Leu332Glu and del(Glu331-Tyr340) mutants. Coimmunoprecipitation was conducted with anti-Flag antibody–agarose beads to precipitate Flag-tagged Bdp1, and coimmunoprecipitated polypeptides were probed with the respective antibodies indicated on the left. (C) Anti-Flag IP results are quantified and plotted with WT signals set to 1. Errors bars indicate the standard errors of the means of four independent experiments. (D) Transcriptional activities of Brf1 mutants. As indicated, WCEs from WT and mutant yeast strains were used in an in vitro transcription assay. The autoradiograms show the SUP4 pre-tRNA transcript (top) and SnR6 transcript (bottom). rBrf1, recombinant WT Brf1. (E) IMT assay. Proteins in the isolated Pol III PICs from the IMT assay were probed with antibodies as indicated on the left. The relative Brf1 and Bdp1 protein levels are listed below the upper rows of gel bands.

DISCUSSION

In the Pol III transcription machinery, Brf1, together with TBP and Bdp1, constitutes transcription factor TFIIIB for Pol III recruitment and open-promoter complex formation. Using site-specific biochemical probing analyses, in this study, we precisely mapped the network of protein interactions for Brf1 in the PIC. Our cross-linking results suggest that the Brf1 N-terminal domain organizes a TFIIB-like domain architecture in the PIC. In contrast, the C-terminal half of Brf1 serves mainly as the interface to hold TBP and Bdp1 for the TFIIIB complex. An open-promoter model of the Pol III PIC is thus derived on the basis of the X-ray structures of the Pol II-TFIIB, TFIIB cyclin fold-TBP-DNA, and Brf1 homology block II-TBP-DNA complexes (Fig. 5) (20, 28, 46). In the model, the ribbon and cyclin fold repeat subdomains are, respectively, localized in the RNA exit tunnel and in the wall domain of the Pol. TBP contacts an 8-bp-long DNA sequence that starts 30 bases upstream of the transcription start site, and the Brf1 cyclin folds clamp the second stirrup of TBP and interact with DNA sequences flanking the TBP-binding region. The Brf1 N linker region was not modeled because of a lack of structural information. However, this region likely interacts with the open-promoter region, as well as structural motifs of the active center, on the basis of our Brf1-C160 cross-linking and its functional role, together with the ribbon subdomain, in DNA opening (11, 13, 47, 48).

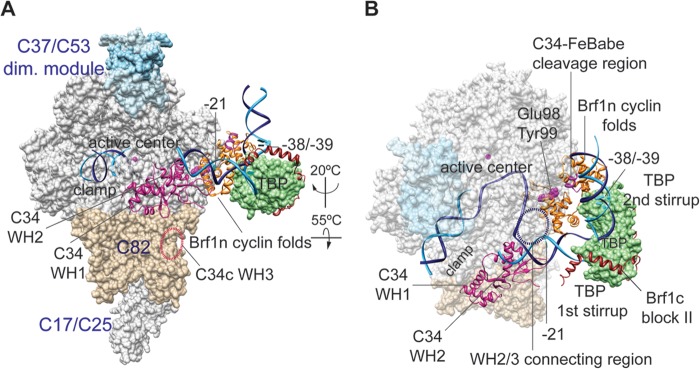

FIG 5.

Model of the Pol III open-promoter complex. (A) The structural model contains Pol III, Brf1, TBP, and open-promoter DNA on the basis of the Pol II-TFIIB-TBP open-promoter complex (19, 20) and the Brf1c homology block II-TBP-DNA structure (28). Subdomains of Brf1 are displayed with the backbone trace model and are color coded as follows: Brf1n cyclin repeats, orange; Brf1c homology block II, brown. The molecular surface model of TBP is pale green. The Pol III core structure is shown as the white molecular surface, and the magenta sphere in the active center represents the magnesium ion. Pol III-specific subunits are displayed as follows: C34 WH1 and WH2, magenta backbone trace; C82, tan molecular surface; C37/53 subcomplex, light blue molecular surface. DNA is represented by the phosphate backbone trace with the template strand in blue and the nontemplate strand in cyan. Positions of DNA base pairs −38/−39 and −21 on the nontemplate strand (relative to the transcription start site [designated +1]) are also indicated. The localization of the WH3 domain of C34 is indicated by the dashed oval line in black. The atomic coordinate file for the Pol III PIC model is available upon request. dim., dimer. (B) Same as in panel A with rotation as indicated. The molecular surfaces of the Pol III core, C37/53 subcomplex, and C82 are semitransparent. As highlighted with the spheres in the Brf1 cyclin repeat model, Glu98 and Tyr99 provide Brf1-C34 BPA cross-linking and Ala246 ± 5 aa is the FeBABE-conjugated C34 hydroxyl radical cleavage site. The dashed circle represents the potential localization of the connecting region between the WH2 and WH3 domains of C34.

The domain architecture of Pol III derived from our previous study localizes the TFIIE-like C82 and C34 subunits on the Pol clamp (Fig. 5). The WH2 domain of C34 is in close contact with the clamp coiled coil and further interacts with the upstream edge of the transcription bubble, which is a 10- to 12-base strand-separated promoter region spanning upstream beginning at the transcription start site (39). With the localization of the C34 WH2 domain, the functionally important connecting region immediately C terminal to WH2 is likely positioned adjacent to the Brf1 cyclin fold repeat subdomain. Our site-specific cross-linking and hydroxyl radical data support this interaction. Further, this C34 connecting region likely contributes to additional upstream C34-DNA interaction on the basis of the Pol III-DNA topography analysis indicating colocalization of C34 and Brf1 in the promoter region spanning ∼20 bases upstream of the transcription start site (49, 50). In the Pol II PIC, the TFIIB cyclin folds were found to interact with the Tfg1 and Tfg2 subunits of transcription factor TFIIF (15), which is positioned on the lobe and protrusion domains of Pol (40). In contrast to the localization of TFIIE, which also interacts with the Pol clamp, TFIIF is on the opposite side of the Pol cleft. Therefore, the cyclin repeats domain is involved in establishing specific interactions with polypeptides on the Pol active-center cleft for respective transcription systems.

Our cross-linking data indicate that Brf1c serves mainly as a bipartite interface for TBP and Bdp1. Specifically, our analysis extends the Bdp1 and TBP binding sites to the C linker 1 region, and we identified a functionally important Bdp1-binding sequence block. Although this Bdp1-binding block contains low sequence homology, secondary-structure analysis indicates consensus α-helical secondary structures in this region. Furthermore, this Bdp1-binding block contains the amino acid sequence Gly328-Glu329-Gln330-Glu331-Leu332 (GEXEL), which was previously reported to be a conserved short motif in Brf1c (25). The structural region of Bdp1 that interacts with this sequence block remains to be determined. In addition to TBP and Bdp1 interactions, we observed weak C34 cross-linking for BPA substitution of Gln549 adjacent to homology block III (data not shown). This C34 cross-link supports a previous genetic interaction analysis that mapped the Brf1-C34 interaction to homology blocks II and III (29).

The domain architecture of the PIC derived from this study explains respective functional roles in DNA opening for the ribbon and N linker and in organizing the TFIIIB-pol III-DNA complex for the cyclin fold repeat subdomain and the C-terminal domain. In the eukaryotic Pol I system, the TFIIB-related factors TAF1B in humans and Rrn7 in yeast also contain TFIIB-like ribbon and cyclin repeat subdomains in their N-terminal domains and unique C-terminal domains specific for respective Pols (23, 24). Genetic analysis for TAF1B indicated that the zinc ribbon and the connecting region (N-terminal linker) function mainly in a postrecruitment step(s), reminiscent of Brf1 (23). Although an analysis of domain localization is not available, a conserved binding mechanism may exist for these Pol I factors, as suggested by our study of Brf1.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank George Kassavetis (University of California San Diego) for advice on biochemical probing experiments. We thank Yue-Chang Chou for protein purification. We thank AndreAna Peña for English editing.

This work was supported by the grant NSC 100-2311-B-001-013-MY3 from the National Science Council, Republic of China, and a Career Development Award to H.-T.C. from Academia Sinica.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 25 November 2013

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/MCB.00910-13.

REFERENCES

- 1.Dieci G, Fiorino G, Castelnuovo M, Teichmann M, Pagano A. 2007. The expanding RNA polymerase III transcriptome. Trends Genet. 23:614–622. 10.1016/j.tig.2007.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Geiduschek EP, Kassavetis GA. 2001. The RNA polymerase III transcription apparatus. J. Mol. Biol. 310:1–26. 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schramm L, Hernandez N. 2002. Recruitment of RNA polymerase III to its target promoters. Genes Dev. 16:2593–2620. 10.1101/gad.1018902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ishiguro A, Kassavetis GA, Geiduschek EP. 2002. Essential roles of Bdp1, a subunit of RNA polymerase III initiation factor TFIIIB, in transcription and tRNA processing. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22:3264–3275. 10.1128/MCB.22.10.3264-3275.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kassavetis GA, Bardeleben C, Kumar A, Ramirez E, Geiduschek EP. 1997. Domains of the Brf component of RNA polymerase III transcription factor IIIB (TFIIIB): functions in assembly of TFIIIB-DNA complexes and recruitment of RNA polymerase to the promoter. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17:5299–5306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kassavetis GA, Driscoll R, Geiduschek EP. 2006. Mapping the principal interaction site of the Brf1 and Bdp1 subunits of Saccharomyces cerevisiae TFIIIB. J. Biol. Chem. 281:14321–14329. 10.1074/jbc.M601702200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kumar A, Grove A, Kassavetis GA, Geiduschek EP. 1998. Transcription factor IIIB: the architecture of its DNA complex, and its roles in initiation of transcription by RNA polymerase III. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 63:121–129. 10.1101/sqb.1998.63.121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kumar A, Kassavetis GA, Geiduschek EP, Hambalko M, Brent CJ. 1997. Functional dissection of the B″ component of RNA polymerase III transcription factor IIIB: a scaffolding protein with multiple roles in assembly and initiation of transcription. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17:1868–1880 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Librizzi MD, Brenowitz M, Willis IM. 1998. The TATA element and its context affect the cooperative interaction of TATA-binding protein with the TFIIB-related factor, TFIIIB70. J. Biol. Chem. 273:4563–4568. 10.1074/jbc.273.8.4563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saïda F. 2008. Structural characterization of the interaction between TFIIIB components Bdp1 and Brf1. Biochemistry 47:13197–13206. 10.1021/bi801406z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kassavetis GA, Kumar A, Letts GA, Geiduschek EP. 1998. A post-recruitment function for the RNA polymerase III transcription-initiation factor IIIB. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 95:9196–9201. 10.1073/pnas.95.16.9196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kassavetis GA, Kumar A, Ramirez E, Geiduschek EP. 1998. Functional and structural organization of Brf, the TFIIB-related component of the RNA polymerase III transcription initiation complex. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18:5587–5599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hahn S, Roberts S. 2000. The zinc ribbon domains of the general transcription factors TFIIB and Brf: conserved functional surfaces but different roles in transcription initiation. Genes Dev. 14:719–730 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC316465/ [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wu CC, Lin YC, Chen HT. 2011. The TFIIF-like Rpc37/53 dimer lies at the center of a protein network to connect TFIIIC, Bdp1, and the RNA polymerase III active center. Mol. Cell. Biol. 31:2715–2728. 10.1128/MCB.05151-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen HT, Hahn S. 2004. Mapping the location of TFIIB within the RNA polymerase II transcription preinitiation complex: a model for the structure of the PIC. Cell 119:169–180. 10.1016/j.cell.2004.09.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen HT, Hahn S. 2003. Binding of TFIIB to RNA polymerase II: mapping the binding site for the TFIIB zinc ribbon domain within the preinitiation complex. Mol. Cell 12:437–447. 10.1016/S1097-2765(03)00306-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bushnell DA, Westover KD, Davis RE, Kornberg RD. 2004. Structural basis of transcription: an RNA polymerase II-TFIIB cocrystal at 4.5 angstroms. Science 303:983–988. 10.1126/science.1090838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu X, Bushnell DA, Wang D, Calero G, Kornberg RD. 2010. Structure of an RNA polymerase II-TFIIB complex and the transcription initiation mechanism. Science 327:206–209. 10.1126/science.1182015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kostrewa D, Zeller ME, Armache KJ, Seizl M, Leike K, Thomm M, Cramer P. 2009. RNA polymerase II-TFIIB structure and mechanism of transcription initiation. Nature 462:323–330. 10.1038/nature08548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sainsbury S, Niesser J, Cramer P. 2013. Structure and function of the initially transcribing RNA polymerase II-TFIIB complex. Nature 493:437–440. 10.1038/nature11715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Colbert T, Hahn S. 1992. A yeast TFIIB-related factor involved in RNA polymerase III transcription. Genes Dev. 6:1940–1949. 10.1101/gad.6.10.1940 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Khoo B, Brophy B, Jackson SP. 1994. Conserved functional domains of the RNA polymerase III general transcription factor BRF. Genes Dev. 8:2879–2890. 10.1101/gad.8.23.2879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Naidu S, Friedrich JK, Russell J, Zomerdijk JC. 2011. TAF1B is a TFIIB-like component of the basal transcription machinery for RNA polymerase I. Science 333:1640–1642. 10.1126/science.1207656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Knutson BA, Hahn S. 2011. Yeast Rrn7 and human TAF1B are TFIIB-related RNA polymerase I general transcription factors. Science 333:1637–1640. 10.1126/science.1207699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Martinez MJ, Sprague KU. 2003. Cloning of a putative Bombyx mori TFIIB-related factor (BRF). Arch. Insect Biochem. Physiol. 54:55–67. 10.1002/arch.10120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kassavetis GA, Joazeiro CA, Pisano M, Geiduschek EP, Colbert T, Hahn S, Blanco JA. 1992. The role of the TATA-binding protein in the assembly and function of the multisubunit yeast RNA polymerase III transcription factor, TFIIIB. Cell 71:1055–1064. 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90399-W [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Colbert T, Lee S, Schimmack G, Hahn S. 1998. Architecture of protein and DNA contacts within the TFIIIB-DNA complex. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18:1682–1691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Juo ZS, Kassavetis GA, Wang J, Geiduschek EP, Sigler PB. 2003. Crystal structure of a transcription factor IIIB core interface ternary complex. Nature 422:534–539. 10.1038/nature01534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Andrau JC, Sentenac A, Werner M. 1999. Mutagenesis of yeast TFIIIB70 reveals C-terminal residues critical for interaction with TBP and C34. J. Mol. Biol. 288:511–520. 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ferri ML, Peyroche G, Siaut M, Lefebvre O, Carles C, Conesa C, Sentenac A. 2000. A novel subunit of yeast RNA polymerase III interacts with the TFIIB-related domain of TFIIIB70. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20:488–495. 10.1128/MCB.20.2.488-495.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moir RD, Puglia KV, Willis IM. 2000. Interactions between the tetratricopeptide repeat-containing transcription factor TFIIIC131 and its ligand, TFIIIB70. Evidence for a conformational change in the complex. J. Biol. Chem. 275:26591–26598. 10.1074/jbc.M003991200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moir RD, Puglia KV, Willis IM. 2002. Autoinhibition of TFIIIB70 binding by the tetratricopeptide repeat-containing subunit of TFIIIC. J. Biol. Chem. 277:694–701. 10.1074/jbc.M108924200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moir RD, Sethy-Coraci I, Puglia K, Librizzi MD, Willis IM. 1997. A tetratricopeptide repeat mutation in yeast transcription factor IIIC131 (TFIIIC131) facilitates recruitment of TFIIB-related factor TFIIIB70. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17:7119–7125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brachmann CB, Davies A, Cost GJ, Caputo E, Li J, Hieter P, Boeke JD. 1998. Designer deletion strains derived from Saccharomyces cerevisiae S288C: a useful set of strains and plasmids for PCR-mediated gene disruption and other applications. Yeast 14:115–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wach A, Brachat A, Pohlmann R, Philippsen P. 1994. New heterologous modules for classical or PCR-based gene disruptions in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 10:1793–1808. 10.1002/yea.320101310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Christianson TW, Sikorski RS, Dante M, Shero JH, Hieter P. 1992. Multifunctional yeast high-copy-number shuttle vectors. Gene 110:119–122. 10.1016/0378-1119(92)90454-W [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chin JW, Cropp TA, Anderson JC, Mukherji M, Zhang Z, Schultz PG. 2003. An expanded eukaryotic genetic code. Science 301:964–967. 10.1126/science.1084772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sikorski RS, Hieter P. 1989. A system of shuttle vectors and yeast host strains designed for efficient manipulation of DNA in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 122:19–27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wu CC, Herzog F, Jennebach S, Lin YC, Pai CY, Aebersold R, Cramer P, Chen HT. 2012. RNA polymerase III subunit architecture and implications for open promoter complex formation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 109:19232–19237. 10.1073/pnas.1211665109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen HT, Warfield L, Hahn S. 2007. The positions of TFIIF and TFIIE in the RNA polymerase II transcription preinitiation complex. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 14:696–703. 10.1038/nsmb1272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jasiak AJ, Armache KJ, Martens B, Jansen RP, Cramer P. 2006. Structural biology of RNA polymerase III: subcomplex C17/25 X-ray structure and 11 subunit enzyme model. Mol. Cell 23:71–81. 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.05.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nikolov DB, Chen H, Halay ED, Usheva AA, Hisatake K, Lee DK, Roeder RG, Burley SK. 1995. Crystal structure of a TFIIB-TBP-TATA-element ternary complex. Nature 377:119–128. 10.1038/377119a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Werner M, Chaussivert N, Willis IM, Sentenac A. 1993. Interaction between a complex of RNA polymerase III subunits and the 70-kDa component of transcription factor IIIB. J. Biol. Chem. 268:20721–20724 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brun I, Sentenac A, Werner M. 1997. Dual role of the C34 subunit of RNA polymerase III in transcription initiation. EMBO J. 16:5730–5741. 10.1093/emboj/16.18.5730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tate JJ, Persinger J, Bartholomew B. 1998. Survey of four different photoreactive moieties for DNA photoaffinity labeling of yeast RNA polymerase III transcription complexes. Nucleic Acids Res. 26:1421–1426. 10.1093/nar/26.6.1421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tsai FT, Sigler PB. 2000. Structural basis of preinitiation complex assembly on human pol II promoters. EMBO J. 19:25–36. 10.1093/emboj/19.1.25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kassavetis GA, Letts GA, Geiduschek EP. 1999. A minimal RNA polymerase III transcription system. EMBO J. 18:5042–5051. 10.1093/emboj/18.18.5042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kassavetis GA, Letts GA, Geiduschek EP. 2001. The RNA polymerase III transcription initiation factor TFIIIB participates in two steps of promoter opening. EMBO J. 20:2823–2834. 10.1093/emboj/20.11.2823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bartholomew B, Durkovich D, Kassavetis GA, Geiduschek EP. 1993. Orientation and topography of RNA polymerase III in transcription complexes. Mol. Cell. Biol. 13:942–952 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bartholomew B, Kassavetis GA, Geiduschek EP. 1991. Two components of Saccharomyces cerevisiae transcription factor IIIB (TFIIIB) are stereospecifically located upstream of a tRNA gene and interact with the second-largest subunit of TFIIIC. Mol. Cell. Biol. 11:5181–5189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.