Abstract

Differentiation of mammary secretory epithelium during pregnancy is characterized by sequential activation of genes over several orders of magnitude. Although the transcription factor STAT5 is key to alveolar development, it is not clear to what extent it controls temporal activation of genetic programs in secretory epithelium. To uncover molecular mechanisms effecting progressive differentiation, we explored genome-wide STAT5 binding and H3K4me3 (i.e., trimethylated histone H3 at K4) marks in mammary tissues at early and midpregnancy and at parturition. STAT5 binding to genes induced during pregnancy was low in immature mammary tissue but increased with epithelial differentiation. Increased STAT5 binding was associated with the establishment of H3K4me3 marks and transcriptional activation. STAT5 binding preceded the formation of H3K4me3 marks in some mammary-specific genes. De novo STAT5 binding was also found at distal sites, indicating enhancers. Furthermore, we established an exhaustive mammary transcriptome. Through integration of RNA-seq and STAT5 and H3K4me4 ChIP-seq data, we discovered novel mammary-specific alternative promoters and genes, including noncoding RNAs. Our findings suggest that STAT5 is an early step in establishing transcription complexes on genes specifically expressed in mammary epithelium. This is the first study in an organ that links progressive chromatin occupancy of STAT5 to the acquisition of H3K4me3 marks and transcription during hormone-induced differentiation.

INTRODUCTION

The establishment of distinct differentiation programs, as reflected by the sequential activation of cell-specific gene sets, is a hallmark of many cell types, including those of the immune system, the erythroid lineage, and mammary secretory epithelium. Development and differentiation of these cells are controlled by cytokines through transcription factors of the family of signal transducers and activators of transcription (STAT). Establishment of the mammary alveolar epithelial lineage, including its expansion and differentiation during pregnancy followed by attaining a functional status at parturition, as reflected by the production and secretion of milk, is largely controlled by progesterone and prolactin through transcription factors, such as ELF5, C/EBPβ, and STAT5A and STAT5B (1–9). Experimental mouse genetics has demonstrated that low concentrations of STAT5 can promote proliferation of mammary alveolar epithelium during pregnancy, but higher concentrations are required to execute the differentiation program (10). RNA-seq analyses further supported the concept of a STAT5 dose-dependent activation of STAT5 target genes. While some gene sets were activated already in the presence of one Stat5 allele, others required at least two Stat5 alleles. These findings suggest that a gene-specific differential affinity for STAT5 may contribute to the temporal activation of distinct biological programs during pregnancy.

Alveolar differentiation during pregnancy is characterized by the chronological activation of distinct gene sets encompassing approximately 750 genes, whose expression is under strict control of STAT5 (10). While some of these genes are activated in early pregnancy, expression of others is induced just prior to parturition. In lactating mammary tissue, the majority of these genes are bound by STAT5 within 5 kbp of their respective transcription start sites (TSS) (10), and they can be placed into at least four distinct categories. Genes such as Csn2 and Wap are active almost exclusively in mammary tissue, and their expression is induced more than 1,000-fold during pregnancy. Genes such as Sftpd are also expressed in other cell types and are activated in mammary epithelium during pregnancy. Bona fide STAT5 target genes, such as Cish and Socs2, although expressed, are not under overt pregnancy or STAT5 control. Finally, there are the genes that are not regulated by STAT5 in any cell type.

H3K4me3 (i.e., trimethylated histone H3 at K4) marks are found not only at TSSs of actively transcribed genes (11) but also at genes primed for subsequent downstream expression in specific cell lineages (12). Not surprisingly, genes strongly induced during pregnancy are bound by STAT5 and carry H3K4me3 marks at the onset of lactation (10). However, the relation between establishment of H3K4me3 marks and STAT5 binding is not clear.

The presence of distinct gene sets that are recognized to a similar degree by STAT5 in fully differentiated mammary epithelium but are subject to differential induction during pregnancy (10) provides a unique opportunity to explore the underlying regulatory mechanism. At day 6 of pregnancy (p6), immature alveolar epithelium has already been established, but differentiation is still in its infancy, as evidenced by moderate and low expression of Csn2 and Wap, respectively, and the absence of Csn1s2b transcripts. In contrast, at day 1 of lactation (L1), all STAT5-dependent differentiation-specific genes are expressed at high levels. It can be proposed that activation of these prolactin-induced genes during pregnancy and their ultimate expression levels during lactation depend on the degree of STAT5 binding to regulatory sequences and polymerase II loading, guided by histone modifications at the respective promoters. To address this hypothesis, we analyzed genome-wide STAT5A binding and H3K4me3 marks in mammary tissue at p6 and p13 and integrated them with previously obtained data from L1 and gene expression at the corresponding stages. Moreover, this study also permitted us to address the question whether STAT5 binding to mammary-specific genes precedes or trails the establishment of H3K4me3 marks.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

RNA-seq analysis.

To identify novel transcripts with our previous RNA-seq (whole-transcriptome shotgun sequencing) data (GEO accession no. GSE37646) (10), we decided to add a deep-sequencing data set obtained from a single mouse at parturition (L1). Poly(A) RNA was purified twice from 1 μg total RNA of wild-type mammary gland tissues, and cDNA was synthesized using SuperScript II (Invitrogen). Sequencing libraries were prepared using the TruSeq RNA sample preparation kit (Illumina). More than 190 million single-end reads were obtained as the output of HiSeq 2000 (Illumina) and aligned to the mouse reference genome (mm9) using the TopHat program (13). We assembled a mammary transcriptome by using Cufflinks with our previous p6 (day 6 of pregnancy) and L1 (day 1 of lactation) RNA-seqs as well as this additional deep L1 RNA-seq (10, 14). We also downloaded an available RNA-seq data set (accession no. GSE29278), which consists of 10 different cell types (bone marrow, cerebellum, cortex, heart, kidney, lung, liver, mouse embryonic fibroblasts, embryonic stem cells, and spleen) and assembled a unified transcriptome for comparison (15). Cuffdiff estimated the abundance of transcripts by means of fragments per kilobase of exon per million fragments mapped (FPKM). DESeq was used to calculate P values for differential expression between p6 and L1 (16).

ChIP-seq analysis.

For chromatin immunoprecipitation coupled with parallel sequencing (ChIP-seq) analysis, frozen-stored wild-type mammary tissues (p6) were broken into powder with a mortar and pestle and then cross-linked with 1% formaldehyde for 10 min. Nuclei were fractionated by sucrose density gradient centrifugation. Chromatin was fragmented to 200 to 300 bp by sonication using a Misonix sonicator 3000 (QSonica). Antibodies against STAT5A (sc-1081; Santa Cruz) and histone H3K4me3 (17-614; Millipore) were used for ChIP. The chromatin immunoprecipitated (ChIPed) DNA fragments were blunt-ended and ligated to the Illumina indexed DNA adaptors using NEBNext ChIP-seq library prep master mix set (E6240; New England BioLabs). The prepared library was sequenced using the Illumina HiSeq 2000. Single-end reads were aligned to the mouse reference genome (mm9) using the Bowtie program (17). We also integrated our previous STAT5 and H3K4me3 ChIP-seqs (L1) for comparison (GEO accession no. GSE40930). The mapped reads of samples and corresponding input controls were analyzed using the HOMER peak calling program with a false discovery rate (FDR) threshold of 0.001 (18). For visualization, the total number of mapped reads in each sample was normalized to 10 million. We used the integrative genomics viewer (IGV) to visualize the normalized ChIP-seq reads (19).

Additional ChIP-seq analysis.

To validate the above ChIP-seq data, we performed STAT5 (p13 and L1) and H3K4me3 (L1) ChIP-seqs with mammary tissues as the biological replicate. We also performed H3K4me3 (p13) ChIP-seq with mammary epithelial cells (MECs), which were isolated from mammary tissues. Briefly, frozen-stored mammary tissues were broken into powder with mortar and pestle. Then cells were cross-linked with 1% formaldehyde for 10 min at room temperature. Nuclei were extracted in Farnham lysis buffer: 5 mM PIPES [piperazine-N,N′-bis(2-ethanesulfonic acid), pH 8.0], 85 mM KCl, 0.5% NP-40, and protease inhibitor. Chromatin was fragmented to 200 to 300 bp by sonication using Misonix sonicator 3000 (QSonica, Newtown, CT). Antibodies against STAT5 (10 μg; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and H3K4me3 (5 μg; Millipore) were used for ChIP. The ChIPed DNA fragments were blunt ended and ligated to the Illumina indexed DNA adaptors and sequenced using the Illumina HiSeq 2000. Single-end reads were aligned to the mouse reference genome (mm9) using the Bowtie program (17).

Quantification of H3K4me3 levels.

The identified H3K4me3 regions at p6 and L1 were merged for comparison. The number of reads on the merged regions was counted and quantile normalized. To identify highly induced H3K4me3 regions between p6 and L1, average mapped tags of H3K4me3 ChIP-seq per 1 bp in each region at p6 were calculated and converted to a z score. We discarded regions showing a z score above or equal to −1, since these regions already have H3K4me3 marks at p6. Highly induced regions were defined as the regions showing 2-fold changes of H3K4me3 levels between p6 and L1.

Promoter identification.

With the assembled transcriptome, active promoters were defined as 300-bp flanking regions of transcription start sites (TSSs) of transcripts, which are associated with H3K4me3 marks. Overlapping promoters were regarded as one. Cuffcompare assigned a class code to each identified transcript based on types of exon/intron match between the transcript and the known reference transcript (14). The class codes are as follows: =, complete match; c, contained in the reference; e, possible pre-mRNA fragment; i, fragment falling into an intron of the reference; j, novel isoform; o, generic overlap with the reference; p, possible polymerase run-on fragment; u, unknown intergenic transcript; r, repeat; s, likely read mapping errors; and x, exonic overlap with the reference on the opposite strand. Alternative promoters were defined as promoters with the class codes c and j. Novel promoters were defined as promoters with the class codes x, o, and u. Promoters with a single exon fragment (except with the class code =) were discarded.

Motif analysis.

MEME-ChIP was used to identify significantly overrepresented motifs around the centers of top 600 STAT5 binding sites (by peak height) with the default setting (http://meme.nbcr.net/meme) (20). The top two predicted motifs determined by the E value, which is an estimate of the expected number of motifs in a similarly sized set of random sequences, are shown in Fig. 2B.

FIG 2.

Progressive STAT5 binding during pregnancy. (A) A Venn diagram shows the number of overlapping STAT5 binding sites between p6 and L1. (B) The top two most significantly overrepresented motifs over 51,609 STAT5 binding sites at L1 are shown. (C) The expression levels of generic (n = 78) and mammary-specific (n = 1,109) STAT5 target genes between p6 and L1 were compared. Extremely highly expressed genes, such as Wap and Csn3, which skew the results for genes expressed at a lower level, were discarded. P values were determined by paired two-sample t test. (D) Three representative loci of the generic and mammary-specific STAT5 target genes are shown. Bars in the GAS track represent GAS (TTCNNNGAA) and half-GAS (TTC or GAA) motifs. Asterisks indicate the half-GAS motifs. Promoter-proximal STAT5 binding sites are shown in black boxes. (E) Peaks on the casein locus indicate levels of STAT5 binding at p6, p13, and L1. Gray-shaded boxes denote promoters (kbp −10 ∼ TSS ∼ kbp +10). (F) Expression levels of six genes in the casein locus are shown in bar graphs. Numbers in parentheses indicate the y-axis scale.

Gene ontology analysis.

The top 300 STAT5 binding peaks and H3K4me3-enriched regions determined by peak height were analyzed by using the Cytoscape network analysis platform with the GeneMANIA plugin (21, 22). The top five significant ontology terms determined by FDR are shown in Fig. 3D.

FIG 3.

Dynamic changes in H3K4me3 levels during pregnancy. (A) A Venn diagram shows the number of overlapping H3K4me3-enriched regions between p6 and L1. (B) The scatter plot shows the quantile normalized sequenced tags on regions either gaining or losing H3K4me3 marks as spots (left). Box plots were used to compare the levels of normalized tags on the H3K4me3-enriched regions (right). P values were determined by paired two-sample t test. (C) The locus view depicts relative levels of H3K4me3 on promoters of the Impa2, Cidea (black box), and Tubb6 genes. (D) Gene ontology analysis by GeneMANIA reveals functions of STAT5 target genes and the genes gaining H3K4me3 (21). FDR, false discovery rate.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The deep L1 RNA-seq, the ChIP-seq, and the additional ChIP-seq data sets have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) under accession no. GSE48685.

RESULTS

Localization of phosphorylated STAT5 in mammary tissue.

In this study, we explored mechanisms controlling the progressive differentiation of mammary epithelium during pregnancy. To achieve this, we investigated four parameters, histological markers, genome-wide STAT5 binding, H3K4me3, and global gene expression. Immature mammary alveoli have formed already at day 6 of pregnancy (p6), followed by extensive proliferation and differentiation as pregnancy progresses through p13 to parturition (L1) (Fig. 1A). To assess STAT5 activity at the cellular level, we performed immunofluorescence for phosphorylated STAT5 (pSTAT5) at p6, p13, and L1 (Fig. 1A). Nuclear accumulation of pSTAT5 was observed in many, but not all, alveolar cells at p6 with a further increase at p13 and homogeneous staining at L1. As judged by E-cadherin (E-cad) expression, only epithelial cells were positive for pSTAT5.

FIG 1.

STAT5 activation in mammary tissue and reproducibility of ChIP-seq data. (A) Nuclear accumulation of phosphorylated STAT5 (arrows; red fluorescence) is present at pregnancy day 6 (p6) and increases at pregnancy day 13 (p13) and lactation day 1 (L1). The cell adhesion molecule E-cadherin reveals the cell membrane in green, and nuclei are stained blue by DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole). (B and C) Normalized mapped reads by reads per kilobase per million mapped reads (RPKM) on 51,609 STAT5 binding sites (B) as well as 15,447 H3K4me3-enriched regions (C) between two biological replicates were compared. r, Pearson's correlation coefficient. (D) The Socs2 locus, which contains several STAT5 binding sites and H3K4me3 marks, shows the same pattern of ChIPed signals between biological replicates. The number in each track indicates the maximum height of normalized reads by reads per million mapped reads (RPM).

Reproducibility of ChIP-seq experiments.

As the interpretation of biological experiments is frequently based on complex ChIP-seq experiments and only single biological samples are available in some cases, we investigated the robustness and variability of ChIP-seq experiments performed on intact mammary tissue. We previously performed ChIP-seq experiments to capture genome-wide STAT5 binding and establish H3K4me3 patterns in mouse mammary tissue at parturition (L1) (10). We now conducted a second ChIP-seq study using a different batch of mammary tissue (L1), different batches of anti-STAT5 and anti-H3K4me3 antibodies, and a different experimental investigator (K. H. Yoo). The correlation between two data sets as determined by Pearson's correlation method is very high (Fig. 1B and C). Manual investigation of many loci, such as Socs2, confirmed that our ChIP-seq experimental method on mammary tissue is robust and highly reproducible (Fig. 1D).

Genome-wide STAT5 binding in developing mammary tissue.

Expression of most mammary differentiation-specific genes is either low or absent at p6 (10). Based on current knowledge, it is reasonable to assume that genes whose expression is largely confined to the functional mammary gland are poised in immature mammary epithelium by H3K4me3 marks but are not bound by the transcription factor STAT5. To explore this hypothesis, we established genome-wide maps of STAT5 binding and H3K4me3 marks in mammary tissue at p6 and p13 by ChIP-seq. These genome-wide structural data were integrated with gene expression results.

A total of approximately 8,800 STAT5 peaks were detected using the HOMER peak detection program, with a false discovery rate (FDR) threshold of 0.001 (Fig. 2A) (18). While 6,129 of these peaks coincided with STAT5 peaks detected at day one of lactation (L1), 2,693 were apparently specific to p6 mammary tissue. However, based on visual inspection of the peak shape and location, most, if not all, were false positives. Out of the 6,129 STAT5 peaks detected at both p6 and L1, 997 were located within 5 kbp of transcriptional start sites (TSSs) of genes. These peaks were again vetted by visual inspection. STAT5 recognized GAS motifs with the consensus sequence TTCNNNGAA, and a de novo motif analysis of in vivo STAT5 binding sites verified this for all sites unique to L1 and those shared at p6 but not p6-specific sites (Fig. 2B). Although the majority of STAT5 binding sites (79%) at L1 contained the conventional GAS motifs, approximately 20% of the sites only harbored half-GAS motifs. For instance, a half-GAS motif coincided with STAT5 binding in the body of the Socs2 gene (Fig. 2D). The level of STAT5 binding to half-GAS motifs upstream of Glycam1 is similar to that of nearby strong STAT5 binding sites. These differences in affinity may reflect the STAT5 status, such as phosphorylated, unphosphorylated, and multimerized forms or various interacting proteins (23). In summary, most, if not all in vivo STAT5 binding sites at p6 coincided with STAT5 binding sites at L1, and they contained either the canonical GAS motif or the half-GAS motif. Similarly, the STAT5 binding pattern at p13 reflected that seen at L1, and the peak sizes were between those determined at p6 and L1 (Fig. 2D and E).

We recently identified a distinct cis-regulatory module (CRM) in genes recognized by all STATs and in all cell types tested (24). ChIP-seq data confirmed the same extent of STAT5 binding to these generic STAT5-dependent genes in mammary tissue at p6, p13, and L1 (Fig. 2D; see Table S1 in the supplemental material). Depending on the gene, the extent of STAT5 binding at p6 was less than half of that seen at L1. For example, compared to the STAT5 occupancy at L1, binding to the Bcl6, Cish, and Socs2 promoters was around 20% at p6 and 40% at p13.

We next focused on representative genes from two distinct classes, genuine STAT5 target genes that are expressed in mammary tissue at similar levels throughout pregnancy, and differentiation-associated genes, whose expression is strongly induced. The first group is exemplified by Cish and Socs2, while Wap and Glycam1 are in the second category (Fig. 2C and D). Strong STAT5 binding to GAS motifs in promoter sequences of the Cish and Socs2 genes was already present at p6. In contrast, less STAT5 binding was observed over the promoter-proximal GAS site in the Wap gene promoter and no binding over the promoter-distal GAS motif and a putative upstream enhancer. In contrast, these sites were strongly bound at L1. Similarly, little STAT5 binding was observed in the genes encoding Glycam1 and the pregnancy-induced long noncoding RNA, PINC (25), at p6, but binding increased sharply over promoter-bound GAS motifs at L1. The approximately 10-fold increase in STAT5 binding to milk protein gene promoters between p6 and L1 corresponds to up to 1,000-fold elevated levels of the respective mRNAs. Moreover, STAT5 binding to the promoter-proximal GAS motif in the Wap gene at p6 does not correlate with its expression, and gene activation seems to require the additional occupation at promoter-distal and enhancer sites observed at L1 (Fig. 2D). In this regard, the degree of STAT5 binding to promoter-proximal and -distal regions of genes in the casein locus (Csn1s1, Csn2, Csn1s2a, Csn1s2b, Odam, and Csn3) at p6 reflects their expression levels (Fig. 2E and F). For instance, the Csn1s2b and Odam genes were not expressed significantly at p6, which correlates with a lack of STAT5 binding in their promoter regions. In contrast, the Csn2 gene was already expressed at p6, and STAT5 binding was observed.

Establishment of H3K4me3 marks in differentiating mammary tissue.

In order to gain biologically relevant information on known genes that are activated during pregnancy in addition to discovering additional promoters or even novel transcripts, we decided to determine the genome-wide H3K4me3 pattern in mammary tissue at p6 and p13 and compare it with that at L1. Using ChIP-seq, we identified a total of approximately 14,500 H3K4me3 marks at p6 (Fig. 3A); approximately 11,800 and 1,700 coincided with known gene promoter sequences and STAT5A binding sites, respectively. Out of the approximately 15,000 H3K4me3 marks in mammary tissue at L1 (10), 13,500 overlapped with marks at p6 (Fig. 3A). The pattern observed at p13 fell between those observed at p6 and L1.

To investigate genes exhibiting dynamic changes in H3K4me3 levels during pregnancy, we focused on the ones that gained H3K4me3 marks between p6 and L1, as they might be under STAT5 control and contribute to the differentiation of mammary tissue. H3K4me3 marks increased more than 2-fold over approximately 1,000 regions (Fig. 3B). For example, Cidea gained H3K4me4 marks (Fig. 3C) during pregnancy, whereas the extent of H3K4me3 remained steady on the flanking genes Impa2 and Tubb6, whose expression does not change during pregnancy. Since STAT5 controls genes associated with the differentiation of mammary tissue (6, 10), we asked whether genes acquiring H3K4me3 marks displayed functions similar to STAT5 target genes. Functional annotations inferred by GeneMANIA (21) confirmed that both gene sets fall into classes linked to cell differentiation associated with mammary gland development (Fig. 3D).

Establishing the mammary transcriptome.

To further explore whether gain of H3K4me3 marks between p6 and L1, in particular those outside known genes, was paralleled by transcriptional activation, we determined gene expression by RNA-seq, including one deep RNA-seq experiment (more than 190 million mapped reads) performed at L1 by using Cufflinks (14). Integrating this de novo transcriptome with the genome-wide H3K4me3 marks enabled us to identify novel promoters and transcripts. As a result, we identified a total of approximately 20,700 promoters, of which 66% coincided with H3K4me3 marks (Fig. 4A). Notably, we identified 972 novel alternative promoters of known genes and 220 promoters of novel genes (see Table S2 in the supplemental material). To assess the cellular activity of these novel promoters, we assembled a transcriptome from available RNA-seqs of 10 different cell types and compared it with the mammary gland transcriptome (10, 15). We identified many genes with different usages of alternative promoters resulting in expressions of tissue-specific isoforms. For instance, the Elf5 gene has two isoforms, but only one (NM_010125) was detected in mammary tissue (Fig. 4B, #1). In the Rab18 gene, additional exons were detected upstream of the known promoter (Fig. 4B, #2), and these sequences coincide with H3K4me3 marks only found in L1 mammary tissue. Activation of Rab18 expression is also reflected by a sharp increase of H3K4me3 levels over the alternative promoter (Fig. 4C). Alternative promoter sequences used at p6 and L1 were also identified in the Shank2 gene (Fig. 4B, #4). In addition to the alternative promoters, novel promoters associated with uncharacterized transcripts were detected (Fig. 4B, #5). Since none of the transcripts obtained from nonmammary tissues (Fig. 4B, “Shen et al.” track) coincided with these novel promoters, we suggest that they are expressed specifically in mammary tissue. Significantly associated known features of the genes with novel alternative promoters were phosphoprotein, GTPase regulator activity, and regulation of transcription, highlighting the importance of studying differential promoter usages of these genes in mammary development (Fig. 4D). Overall, our approach of integrating H3K4me3 ChIP-seq and the de novo assembly of a mammary transcriptome led to the discovery of novel promoters, as well as alternative promoters of known genes, which yielded diverse mammary-specific transcripts.

FIG 4.

De novo assembly of mammary gland transcriptome. (A) A transcriptome was assembled by using Cufflinks with RNA-seqs of mammary gland tissues at p6 and L1 (14). Novel alternative promoters and promoters of novel genes were identified. (B) Assembled transcripts coupled with H3K4me3 marks discovered active alternative promoters and novel genes that are mammary tissue specific. Transcripts assembled with RNA-seq of 10 different cell types (15) are shown in the “Shen et al.” track. Gray boxes denote promoter regions (kbp −10 ∼ TSS ∼ kbp +10). (C) A bar graph indicates the fold change (L1 over p6) of H3K4me3 levels on the five promoters. (D) Functions of the genes with novel alternative promoters were predicted by DAVID (41).

STAT5 binding can precede H3K4me3 and transcription.

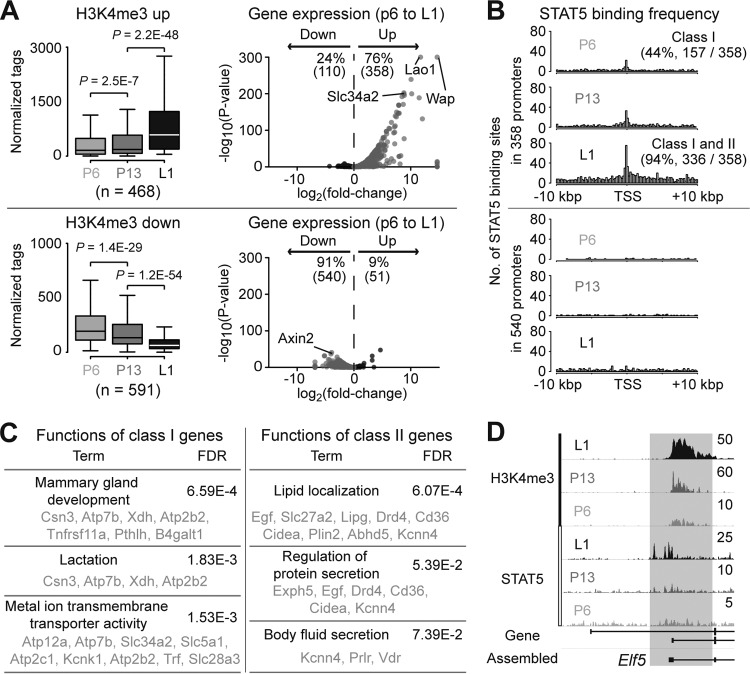

Poised genes, even if they are inactive, are frequently characterized by H3K4me3 marks. Our results suggested that dynamic changes in STAT5 binding, H3K4me3 levels, and gene expression occurred in mammary tissue during pregnancy. The availability of genome-wide data sets allowed us to explore the question whether the binding of STAT5 precedes the establishment of H3K4me3 marks and the activation of the corresponding gene. For this purpose, we focused on p6 mammary tissue, where some of the differentiation-associated genes are expressed at baseline levels. As expected, 76% (358 out of 468) of genes that significantly gained H3K4me3 marks were highly induced (Fig. 5A). In contrast, expression of 91% (540 out of 591) of genes losing their H3K4me3 marks was reduced. The H3K4me3 marks at p13 showed an intermediate level between p6 and L1. Intriguingly, STAT5 binding at p6 and L1 is only associated with genes acquiring H3K4me3 marks but not with genes losing H3K4me3 marks (Fig. 5B). Among the 358 genes, 44% of them (class I [i.e., mammary specific and highly activated during pregnancy]) were already recognized by STAT5 prior to the establishment of H3K4me3 marks at p6. This result illustrates a mechanism that STAT5 binding precedes H3K4me3 marks to activate transcription. Common functions of the class I genes are significantly associated with mammary gland development and transmembrane transporter activity, suggesting that an intrinsic program of mammary gland development that is initiated by STAT5 begins as early as the p6 stage (Fig. 5C). Similarly, functions of the class II genes, which are activated by STAT5 at later pregnancy, are associated with lipid localization and secretion. Notably, the Elf5 gene, encoding a key transcription factor required for mammary gland development, is active at p6, as determined by the enrichment of H3K4me3 marks (Fig. 5D). In addition, this study further reveals that progressive STAT5 binding to a mammary-specific promoter region of Elf5 contributes to a gradual increase of H3K4me3 marks, which seems to boost the expression of the Elf5 gene at L1 (see Table S1 in the supplemental material).

FIG 5.

STAT5 precedes the establishment of H3K4me3 marks on a set of STAT5 target genes at p6. (A) Enrichment levels of H3K4me3 on promoters of genes either gaining (n = 468) or losing (n = 591) H3K4me3 marks were compared by means of quantile normalized tags from ChIP-seq (left). P values were determined by paired two-sample t test. Volcano plots show expression levels of the genes (right). The P values were calculated by DESeq for differential expression (7). Each dot indicates a gene. (B) Distributions of STAT5 binding within promoter regions were calculated. We defined class I genes as genes with STAT5 binding at p6 and class II genes as genes with STAT5 binding at L1 but not p6. (C) Functional annotation analysis by GeneMANIA (21) predicted significantly associated functions with class I and II genes. (D) H3K4me3 and STAT5 ChIP-seq peaks near the mammary-specific promoter of Elf5 (gray box) are shown.

STAT5 activates mammary-specific genes and noncoding RNAs through known and alternative promoters.

Our results demonstrated that class I genes are activated by STAT5 binding around the p6 stage and immediately gain H3K4me3 marks. To determine whether these features are mammary specific, we integrated H3K4me3 ChIP-seq conducted in various tissues (15). A comparison by heat mapping demonstrated that the majority of these genes are indeed mammary specific (Fig. 6A). To determine whether H3K4me3 levels in these genes are regulated in a STAT5 dosage-dependent manner, we integrated our previous H3K4me3 ChIP-seq data sets from Stat5a−/− mice, which still carry both copies of Stat5b (BB track) and express only 30% of total STAT5 (10). The levels of H3K4me3 on the majority of the class I genes, including Lao1 and Wap (Fig. 6D), decreased to a degree seen at p6 in wild-type tissue. Therefore, the establishment of H3K4me3 marks on most, if not all, mammary-specific genes depended on STAT5 binding. Our approach also identified several noncoding RNAs, including PINC (25), which coincided with STAT5 binding at p6 and gradually gained H3K4me3 marks (Fig. 6B; see Table S3 in the supplemental material). The same pattern was observed in many genes, including Stk25, Ggt1, Atp7b, and Atp2b2 (Fig. 6D). However, their activation did not proceed through STAT5 binding to known promoters but through novel alternative promoters (Fig. 6C).

FIG 6.

H3K4me3 levels are dependent on STAT5 binding. We integrated available H3K4me3 ChIP-seq data obtained in various tissues (15) and our previous STAT5A (5A), STAT5B (5B), and H3K4me3 ChIP-seq data from experiments conducted in L1 mammary gland of wild-type and BB (Stat5a−/−) mice (10) as well as wild-type p6 mammary tissue. The known transcriptome (Refseq track [gray]) was also compared with our de novo-assembled transcriptome (assembled track [black]). Open ovals in the tracks indicate the first exons. (A) The heat map shows H3K4me3 levels on promoters of the class I genes (n = 157 columns) across tissues. Black and white areas indicate enrichment and depletion of H3K4me3 marks, respectively. MEF, mouse embryonic fibroblasts; BM, bone marrow; CB, cerebellum. (B) Three loci (chromosome 1 ([chr1], 139,626,057 to 139,652,466; chr11, 109,618,732 to 109,636,572; and chr19, 45,613,519 to 45,638,935) encoding novel noncoding RNAs are shown. (C) Alternative promoters (assembled track) of four genes specific to mammary gland development are shown with one control gene (Socs2). (D) Milk protein gene loci are shown. Boxes indicate promoters that gain H3K4me3 marks during pregnancy. Asterisks pinpoint STAT5 binding sites that occur prior to the establishment of H3K4me3 marks at p6.

Milk protein genes are developmental biomarkers for mammary tissue. While highly expressed at L1, Lao1, the gene encoding l-amino oxidase 1, is virtually silent at p6, making it an ideal candidate to further explore the above question. Although no H3K4me3 was detected over the Lao1 gene at p6, STAT5 binding was observed (Fig. 6D). The same holds true for the Wap gene, various casein genes, and other milk protein genes (Fig. 6D). In contrast, STAT5 binding and H3K4me3 coincided for other genuine, but noninducible STAT5 targets, such as Socs2 (Fig. 6C). Overall, these results highlight tissue-specific roles of STAT5 as a master regulator for mammary gland development.

DISCUSSION

The approximately 1,100 genes bound by STAT5 in mammary tissue during lactation can be placed into two functional groups: genes that are expressed specifically in mammary epithelium and are highly activated during the course of pregnancy and those expressed in several cell types and not regulated during pregnancy. While the former group includes genes associated with the differentiation of mammary epithelium, the second group includes bona fide STAT5 target genes, such as Cish and Socs2. Comparison of STAT5 binding to these gene sets and their H3K4me3 status in immature and functional mammary tissue provided novel mechanistic insight into the temporal regulation of mammary-specific genes during pregnancy. Notably, STAT5 binding to regulatory sequences can precede the establishment of H3K4me3 marks, suggesting that STAT5 access is required and responsible for mammary-specific gene expression. The integration of data obtained from RNA-seq and STAT5 and H3K4me3 ChIP-seq experiments resulted in the identification of novel mammary-specific promoters.

Since this study is based on genome-wide analyses of total mouse mammary tissue, the cell heterogeneity and biological variability have to be taken into account for the interpretation of the results. Mammary tissue not only is composed of ductal and alveolar epithelium but also contains myoepithelial, hematopoietic, and endothelial cells and fibroblasts, among others. While epithelial cells vastly outnumber these “contaminating” cells in lactating tissue, they are less abundant in early stages of pregnancy. As this study focused on genes whose expression is almost exclusively restricted to differentiating mammary alveolar epithelium, the gain of STAT5 binding to respective regulatory sequences and the acquisition of H3K4me3 marks occur most likely within the epithelial genome. STAT5 binding to these mammary-restricted genes has only been observed in native mammary epithelium and not in other cell types (24). Investigation of STAT5 binding from primary mammary cells is not an option as genomic binding of transcription factors is lost during the preparation of epithelial cells. Moreover, primary mammary cells have lost their prolactin receptor, and the reactivation of STAT5 by prolactin stimulation is not possible. Finally, studies with intact liver, a tissue also composed of different cell types, have yielded robust data sets on STAT5 binding to the hepatocyte genome (26), substantiating the approach of using total tissue. Biological variability also does not appear to be an issue. STAT5 and H3K4me3 ChIP-seq experiments on L1 mammary tissue were performed independently by two scientists 18 months apart, and the results were superimposable.

The sequence of molecular events leading to the STAT5-mediated activation of the approximately 700 specific gene loci during pregnancy is not fully understood (10). Although active STAT5 is present in immature mammary tissue at early pregnancy, many of these genes are silent or their expression is barely detectable. This study has demonstrated little STAT5 binding to mammary-specific genes in immature tissue and a lack of H3K4me3 marks. As pregnancy progresses, STAT5 occupancy increases, and H3K4me3 marks are acquired, coinciding with the activation of these differentiation-specific genes. Increased STAT5 occupancy probably also reflects an increased pool of cells that responds to prolactin (Fig. 7). In contrast, a number of genes, including Socs2 and Cish, display extensive H3K4me3 marks and STAT5 binding in their promoter region already in immature mammary tissue. Although these genes are occupied by STAT5, their expression is largely independent of pregnancy status. These two gene classes differ in the complexity of STAT5 binding sites in vivo and the temporal order by which they are occupied. Common STAT5 target genes mostly contain only one or two promoter-bound STAT5 binding sites, as exemplified by Socs2 and Cish. In contrast, mammary differentiation-specific genes exhibit a more complex STAT5 binding landscape with promoter-bound as well as upstream STAT5 binding sites, which may coincide with enhancers (27, 28). In the immature mammary alveolar epithelium, promoter-bound sites are frequently occupied by STAT5. This, however, is not associated with H3K4me3 modification and transcriptional activity. H3K4me3 and transcriptional activation are only observed upon complete STAT5 loading. These findings demonstrate that chromatin of differentiation-specific genes is accessible to STAT5 in immature cells. This, however, does not translate into any significant transcription. Cues that facilitate additional STAT5 binding during pregnancy are required for the activation of these loci. We propose that STAT5 affinity for complex sites is lower than that for the simple sites and that low-affinity sites are only occupied as pregnancy progresses. Notably, there is evidence to suggest that the combination of low- and high-affinity STAT5 binding sites, possibly in conjunction with other transcription factors (TFs), controls the expression of mammary-specific genes (27, 29–31).

FIG 7.

Changes in chromatin landscape during mammary development. Basal STAT5 (ovals) binding occurs at promoters (P) of STAT5-dependent genes in early pregnancy. As pregnancy progresses, STAT5 activity and STAT5 binding increase at promoters and putative enhancer (E) regions in mammary-specific genes, and gene transcription is induced. H3K4me3 marks (solid circles) in these genes are acquired during pregnancy. In contrast, H3K4me3 marks at STAT5 target genes that are expressed in multiple cell types are present throughout pregnancy, and STAT5 binding is unaltered. Alveolar development and nuclear STAT5 levels during pregnancy are illustrated on the left.

In general, H3K4me3 has been associated with actively transcribed and also poised genes. Globally, the establishment of this mark appears to parallel the transcriptional activation of genes as cell lineages are established and cells undergo differentiation (32, 33). In the hematopoietic system, lineage differentiation-specific genes are primed already with H3K4me3 marks in stem and progenitor cells and even in embryonic stem cells, prior to their expression in differentiated lineages (12). We have found that mammary differentiation-specific genes generally do not acquire significant H3K4me3 marks prior to their expression. Notably, binding of the transcription factor STAT5 to promoter sequences can precede the establishment of H3K4me3 marks and transcriptional activation. Thus, STAT5 binding to promoter sequences in vivo does not appear to be sufficient for their activation in mammary tissue, and the occupation of upstream sites that could constitute enhancers is required for the activation of these loci. In support of this, a DNase I-hypersensitive site has been detected in the Wap gene promoter in immature cells, while a hypersensitive site colocalized with the upstream STAT5 binding site is restricted to mature epithelium (34), coinciding with maximal transcription. It remains to be determined whether STAT5 participates in the recruitment of histone methyltransferases at mammary-specific promoters. A precedent for this comes from a study demonstrating that the transcription factor USF1 guides the methyltransferase HSET1A to distinct promoters, thus regulating lineage-specific differentiation (35).

A view emerges that the hormone-sensing transcription factor STAT5 gradually occupies gene promoters and enhancers in mammary epithelium during pregnancy and thereby controls the differentiation process that leads to lactation. An increasing concentration of prolactin during pregnancy and a concomitant increase in STAT5 activity lead to progressive STAT5 binding to genes that control functional alveolar differentiation. In addition to these hormone-responsive genes, whose expression is largely restricted to mammary epithelium and can exceed 4 orders of magnitude, STAT5 also occupies promoter sequences of gene sets that are expressed in other tissues. However, STAT5 binding to these genes is largely independent of pregnancy status, as is their expression. We suggest that genes progressively activated during pregnancy contain complex enhancers that differentially respond to increased levels of phosphorylated STAT5. In contrast, STAT5 appears to have rather unrestricted access to promoter sequences of genes that are widely expressed and whose expression is only slightly modulated by cytokines. A recent study identified two distinct epithelial cell populations in mouse mammary tissue: hormone-sensing and milk-producing cells (36). At this point, STAT5 targets specific to hormone-sensing cells are not known. A key role for STAT5 in the activation of cell-specific enhancers has also been shown for sex-biased genes in liver tissue (37), and STAT4 and -6 determine enhancer activity in Th1 and Th2 cells (28). A defining role of STAT5 in controlling enhancer function, and to a lesser extent promoter function, has also been revealed using transgenic animals (29, 38–40). Further comparative analyses of genome-wide binding of different STAT family members (24, 26, 28) should provide a molecular understanding of the cell- and development-specific contributions of these ubiquitous environmental sensors in controlling promoter and enhancer functions.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

High-throughput sequencing was performed by the NIDDK Genomics Core (Harold Smith).

This work was supported by the Intramural Program of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, NIH.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 25 November 2013

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/MCB.00988-13.

REFERENCES

- 1.Seagroves TN, Krnacik S, Raught B, Gay J, Burgess-Beusse B, Darlington GJ, Rosen JM. 1998. C/EBPbeta, but not C/EBPalpha, is essential for ductal morphogenesis, lobuloalveolar proliferation, and functional differentiation in the mouse mammary gland. Genes Dev. 12:1917–1928. 10.1101/gad.12.12.1917 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee HJ, Ormandy CJ. 2012. Elf5, hormones and cell fate. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 23:292–298. 10.1016/j.tem.2012.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oakes SR, Naylor MJ, Asselin-Labat ML, Blazek KD, Gardiner-Garden M, Hilton HN, Kazlauskas M, Pritchard MA, Chodosh LA, Pfeffer PL, Lindeman GJ, Visvader JE, Ormandy CJ. 2008. The Ets transcription factor Elf5 specifies mammary alveolar cell fate. Genes Dev. 22:581–586. 10.1101/gad.1614608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhou J, Chehab R, Tkalcevic J, Naylor MJ, Harris J, Wilson TJ, Tsao S, Tellis I, Zavarsek S, Xu D, Lapinskas EJ, Visvader J, Lindeman GJ, Thomas R, Ormandy CJ, Hertzog PJ, Kola I, Pritchard MA. 2005. Elf5 is essential for early embryogenesis and mammary gland development during pregnancy and lactation. EMBO J. 24:635–644. 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.LaMarca HL, Visbal AP, Creighton CJ, Liu H, Zhang Y, Behbod F, Rosen JM. 2010. CCAAT/enhancer binding protein beta regulates stem cell activity and specifies luminal cell fate in the mammary gland. Stem Cells 28:535–544. 10.1002/stem.297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hennighausen L, Robinson GW. 2005. Information networks in the mammary gland. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 6:715–725. 10.1038/nrm1714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hughes K, Watson CJ. 2012. The spectrum of STAT functions in mammary gland development. JAK-STAT 1:151–158. 10.4161/jkst.19691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brisken C, O'Malley B. 2010. Hormone action in the mammary gland. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2:a003178. 10.1101/cshperspect.a003178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Robinson GW, Johnson PF, Hennighausen L, Sterneck E. 1998. The C/EBPbeta transcription factor regulates epithelial cell proliferation and differentiation in the mammary gland. Genes Dev. 12:1907–1916. 10.1101/gad.12.12.1907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yamaji D, Kang K, Robinson GW, Hennighausen L. 2013. Sequential activation of genetic programs in mouse mammary epithelium during pregnancy depends on STAT5A/B concentration. Nucleic Acids Res. 41:1622–1636. 10.1093/nar/gks1310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guenther MG, Levine SS, Boyer LA, Jaenisch R, Young RA. 2007. A chromatin landmark and transcription initiation at most promoters in human cells. Cell 130:77–88. 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abraham BJ, Cui K, Tang Q, Zhao K. 2013. Dynamic regulation of epigenomic landscapes during hematopoiesis. BMC Genomics 14:193. 10.1186/1471-2164-14-193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim D, Pertea G, Trapnell C, Pimentel H, Kelley R, Salzberg SL. 2013. TopHat2: accurate alignment of transcriptomes in the presence of insertions, deletions and gene fusions. Genome Biol. 14:R36. 10.1186/gb-2013-14-4-r36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roberts A, Pimentel H, Trapnell C, Pachter L. 2011. Identification of novel transcripts in annotated genomes using RNA-Seq. Bioinformatics 27:2325–2329. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shen Y, Yue F, McCleary DF, Ye Z, Edsall L, Kuan S, Wagner U, Dixon J, Lee L, Lobanenkov VV, Ren B. 2012. A map of the cis-regulatory sequences in the mouse genome. Nature 488:116–120. 10.1038/nature11243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Anders S, Huber W. 2010. Differential expression analysis for sequence count data. Genome Biol. 11:R106. 10.1186/gb-2010-11-10-r106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Langmead B, Trapnell C, Pop M, Salzberg SL. 2009. Ultrafast and memory-efficient alignment of short DNA sequences to the human genome. Genome Biol. 10:R25. 10.1186/gb-2009-10-3-r25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heinz S, Benner C, Spann N, Bertolino E, Lin YC, Laslo P, Cheng JX, Murre C, Singh H, Glass CK. 2010. Simple combinations of lineage-determining transcription factors prime cis-regulatory elements required for macrophage and B cell identities. Mol. Cell 38:576–589. 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.05.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Robinson JT, Thorvaldsdottir H, Winckler W, Guttman M, Lander ES, Getz G, Mesirov JP. 2011. Integrative genomics viewer. Nat. Biotechnol. 29:24–26. 10.1038/nbt.1754 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Machanick P, Bailey TL. 2011. MEME-ChIP: motif analysis of large DNA datasets. Bioinformatics 27:1696–1697. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Warde-Farley D, Donaldson SL, Comes O, Zuberi K, Badrawi R, Chao P, Franz M, Grouios C, Kazi F, Lopes CT, Maitland A, Mostafavi S, Montojo J, Shao Q, Wright G, Bader GD, Morris Q. 2010. The GeneMANIA prediction server: biological network integration for gene prioritization and predicting gene function. Nucleic Acids Res. 38:W214–W220. 10.1093/nar/gkq537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saito R, Smoot ME, Ono K, Ruscheinski J, Wang PL, Lotia S, Pico AR, Bader GD, Ideker T. 2012. A travel guide to Cytoscape plugins. Nat. Methods 9:1069–1076. 10.1038/nmeth.2212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mandal M, Powers SE, Maienschein-Cline M, Bartom ET, Hamel KM, Kee BL, Dinner AR, Clark MR. 2011. Epigenetic repression of the Igk locus by STAT5-mediated recruitment of the histone methyltransferase Ezh2. Nat. Immunol. 12:1212–1220. 10.1038/ni.2136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kang K, Robinson GW, Hennighausen L. 2013. Comprehensive meta-analysis of signal transducers and activators of transcription (STAT) genomic binding patterns discerns cell-specific cis-regulatory modules. BMC Genomics 14:4. 10.1186/1471-2164-14-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shore AN, Kabotyanski EB, Roarty K, Smith MA, Zhang Y, Creighton CJ, Dinger ME, Rosen JM. 2012. Pregnancy-induced noncoding RNA (PINC) associates with polycomb repressive complex 2 and regulates mammary epithelial differentiation. PLoS Genet. 8:e1002840. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002840 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang Y, Laz EV, Waxman DJ. 2012. Dynamic, sex-differential STAT5 and BCL6 binding to sex-biased, growth hormone-regulated genes in adult mouse liver. Mol. Cell. Biol. 32:880–896. 10.1128/MCB.06312-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Burdon TG, Maitland KA, Clark AJ, Wallace R, Watson CJ. 1994. Regulation of the sheep beta-lactoglobulin gene by lactogenic hormones is mediated by a transcription factor that binds an interferon-gamma activation site-related element. Mol. Endocrinol. 8:1528–1536. 10.1210/me.8.11.1528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vahedi G, Takahashi H, Nakayamada S, Sun HW, Sartorelli V, Kanno Y, O'Shea JJ. 2012. STATs shape the active enhancer landscape of T cell populations. Cell 151:981–993. 10.1016/j.cell.2012.09.044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li S, Rosen JM. 1995. Nuclear factor I and mammary gland factor (STAT5) play a critical role in regulating rat whey acidic protein gene expression in transgenic mice. Mol. Cell. Biol. 15:2063–2070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kabotyanski EB, Rijnkels M, Freeman-Zadrowski C, Buser AC, Edwards DP, Rosen JM. 2009. Lactogenic hormonal induction of long distance interactions between beta-casein gene regulatory elements. J. Biol. Chem. 284:22815–22824. 10.1074/jbc.M109.032490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kabotyanski EB, Huetter M, Xian W, Rijnkels M, Rosen JM. 2006. Integration of prolactin and glucocorticoid signaling at the beta-casein promoter and enhancer by ordered recruitment of specific transcription factors and chromatin modifiers. Mol. Endocrinol. 20:2355–2368. 10.1210/me.2006-0160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.De Gobbi M, Garrick D, Lynch M, Vernimmen D, Hughes JR, Goardon N, Luc S, Lower KM, Sloane-Stanley JA, Pina C, Soneji S, Renella R, Enver T, Taylor S, Jacobsen SE, Vyas P, Gibbons RJ, Higgs DR. 2011. Generation of bivalent chromatin domains during cell fate decisions. Epigenetics Chromatin 4:9. 10.1186/1756-8935-4-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cui K, Zang C, Roh TY, Schones DE, Childs RW, Peng W, Zhao K. 2009. Chromatin signatures in multipotent human hematopoietic stem cells indicate the fate of bivalent genes during differentiation. Cell Stem Cell 4:80–93. 10.1016/j.stem.2008.11.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rijnkels M, Freeman-Zadrowski C, Hernandez J, Potluri V, Wang L, Li W, Lemay DG. 2013. Epigenetic modifications unlock the milk protein gene loci during mouse mammary gland development and differentiation. PLoS One 8:e53270. 10.1371/journal.pone.0053270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Deng C, Li Y, Liang S, Cui K, Salz T, Yang H, Tang Z, Gallagher PG, Qiu Y, Roeder R, Zhao K, Bungert J, Huang S. 2013. USF1 and hSET1A mediated epigenetic modifications regulate lineage differentiation and HoxB4 transcription. PLoS Genet. 9:e1003524. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tarulli GA, De Silva D, Ho V, Kunasegaran K, Ghosh K, Tan BC, Bulavin DV, Pietersen AM. 2013. Hormone-sensing cells require Wip1 for paracrine stimulation in normal and premalignant mammary epithelium. Breast Cancer Res. 15:R10. 10.1186/bcr3381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sugathan A, Waxman DJ. 2013. Genome-wide analysis of chromatin states reveals distinct mechanisms of sex-dependent gene regulation in male and female mouse liver. Mol. Cell. Biol. 33:3594–3610. 10.1128/MCB.00280-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pittius CW, Hennighausen L, Lee E, Westphal H, Nicols E, Vitale J, Gordon K. 1988. A milk protein gene promoter directs the expression of human tissue plasminogen activator cDNA to the mammary gland in transgenic mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 85:5874–5878. 10.1073/pnas.85.16.5874 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gordon K, Lee E, Vitale JA, Smith AE, Westphal H, Hennighausen L. 1992. Production of human tissue plasminogen activator in transgenic mouse milk. 1987. Biotechnology 24:425–428 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McKnight RA, Spencer M, Wall RJ, Hennighausen L. 1996. Severe position effects imposed on a 1 kb mouse whey acidic protein gene promoter are overcome by heterologous matrix attachment regions. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 44:179–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Huang DW, Sherman BT, Lempicki RA. 2009. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat. Protoc. 4:44–57. 10.1038/nprot.2008.211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.