ABSTRACT

The innate immune response is the first line of defense against most viral infections. Its activation promotes cell signaling, which reduces virus replication in infected cells and leads to induction of the antiviral state in yet-uninfected cells. This inhibition of virus replication is a result of the activation of a very broad spectrum of specific cellular genes, with each of their products usually making a small but detectable contribution to the overall antiviral state. The lack of a strong, dominant function for each gene product and the ability of many viruses to interfere with the development of the antiviral response strongly complicate identification of the antiviral activity of the activated individual cellular genes. However, we have previously developed and applied a new experimental system which allows us to define a critical function of some members of the poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) family in clearance of Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus mutants from infected cells. In this new study, we demonstrate that PARP7, PARP10, and the long isoform of PARP12 (PARP12L) function as important and very potent regulators of cellular translation and virus replication. The translation inhibition and antiviral effect of PARP12L appear to be mediated by more than one protein function and are a result of its direct binding to polysomes, complex formation with cellular RNAs (which is determined by both putative RNA-binding and PARP domains), and catalytic activity.

IMPORTANCE

INTRODUCTION

Virus replication in infected cells is strongly determined by two competing processes: (i) the ability of cells to sense virus-specific molecules and complexes and (ii) the ability of viral proteins to interfere with the cellular response to viral infection. The balance between these two processes determines virus spread and outcome of the infection on cellular and organismal levels. The antiviral response depends on the cells' ability to detect distinct viral signatures, which are termed pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) (1), followed by activation of a wide combination of genes, whose products interfere with replication of specific viruses. The hallmark of this antiviral response is the secretion of type I interferon (IFN-α/β). The released IFN functions in both autocrine and paracrine modes through activation of interferon-stimulated genes (ISGs) in infected and yet-uninfected cells, respectively. The ISGs are represented by a very broad spectrum of specific cellular genes (2–12). The products of each individual gene, or subsets of these genes, demonstrate small but, in some cases, detectable antiviral activity. Thus, the antiviral response appears to be the sum of a large number of different protein activities, and so far none of the ISGs in isolation, with the exception of key transcriptional factors, have been observed to be capable of inhibiting viral replication to undetectable levels. The involvement of hundreds of cellular proteins, with each making small, virus-specific contributions to the overall cellular response, appears to make the system universally efficient against a wide variety of viral infections. The lack of a particular antiviral gene with dominant inhibitory function also prevents natural selection of viral mutants resistant to the overall antiviral response. On the other hand, the involvement of numerous contributors with redundant functions strongly complicates dissection of the mechanisms of their antiviral activities.

In our previous study (13), we applied a new experimental system to define cellular antiviral genes, whose products contribute to development of the antiviral state and, most importantly, to clearance of replicating Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus (VEEV) from infected cells (11). VEEV is a representative member of the New World alphaviruses (14, 15). In vertebrate hosts, it causes an acute infection, characterized by a high-titer viremia and ultimately virus replication in the brain, which leads to development of severe meningoencephalitis. The overall mortality rates among humans are not high, but this virus is universally lethal for mice and induces very high mortality rates in equids. Our data demonstrated that 98 cellular gene products are specifically expressed in cells during type I IFN-mediated clearance of VEEV mutants which were designed to be incapable of interfering with the development of the cellular antiviral response. However, these genes were not activated in murine fibroblasts which were defective in type I IFN signaling. The latter cells supported persistent, noncytopathic replication of the same VEEV mutant. For most of the products of identified genes activated during virus clearance, the antiviral functions have been previously suggested, but for some of them, the antiviral effects have not been described.

The poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase 12 (PARP12) gene, which is activated during VEEV clearance, attracted most of our attention. In the experiments that followed, expression of the corresponding protein demonstrated a very strong inhibitory effect on replication of both the wild-type (wt) and mutant VEEV variants in vertebrate cells. Moreover, the long isoform of PARP12 (PARP12L) served as a potent inhibitor of replication of a variety of alphaviruses and other RNA viruses, suggesting a broad-spectrum antiviral function via interference with common cellular processes involved in virus replication. A preliminary examination of other PARP family members showed that in addition to PARP12L, the PARP7 and PARP10 genes also encode the amino-terminal domains with putative RNA-binding motifs and are the ISGs. Expression of the last two proteins demonstrated an antiviral effect and inhibited alphavirus replication. Thus, the previous study suggested that the PARP family (16) contains several members involved in the antiviral response and that their function was previously unnoticed (11). Further analysis of the functions of PARPs is complicated, because almost all of these proteins are poorly studied in terms of their roles in cellular processes. Their possible involvement in the antiviral defense has not been investigated at all. The only known member of the PARP family with described antiviral activity is PARP13 (ZAP) (17, 18). This protein also exhibits a broad, potent inhibitory effect against numerous viruses, including Sindbis virus (SINV) (19). The mechanism of its function was proposed to be direction of virus-specific RNAs to the degradation pathway (20–22). However, as we show in Results, in contrast to PARP13, other PARPs used in the study most likely utilize different means to mediate their inhibitory effect on VEEV replication.

This study was aimed at further mechanistic understanding of the activities of PARPs in the antiviral response, with the main focus on the function of PARP12L. Our data demonstrate that PARP12L, PARP7, and PARP10 are very potent negative regulators of cellular translation. PARP12L was found to be involved in a variety of processes resulting in translation inhibition, with both its PARP domain and RNA-binding domains playing critical roles. Point mutations either in the catalytic site of the PARP domain or in its main autoribosylation site have deleterious effects on the PARP's ability to inhibit cellular translation. Thus, the accumulated data strongly suggest that the PARP family contains a group of IFN-inducible inhibitors of virus replication, whose importance has not been previously demonstrated.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell cultures.

The BHK-21 cells were kindly provided by Paul Olivo (Washington University, St. Louis, MO). These cell lines were maintained at 37°C in alpha minimum essential medium (αMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and vitamins.

Plasmid constructs.

Synthesis of PARP12L (NM_172893), PARP12S (also termed PARP12-N) (encoding the amino-terminal domain of PARP12L, amino acids [aa] 1 to 484), PARP7 (NM_178892), and PARP10 (NM_001163576) genes was described elsewhere (11). PARP12-C, encoding the carboxy-terminal domain of PARP12L (aa 483 to 711), was synthesized by PCR. Site-directed mutagenesis, fusion with 3× Flag-coding sequence, and other modifications (see Results for details) were performed using PCR-based approaches. The designed genes were cloned into VEEV replicons in direct or reverse (VEErep/PARPrev) orientation under the control of the subgenomic promoter. All of the VEEV replicons were also designed to express the Pac (puromycin N-acetyltransferase) gene from the second subgenomic promoter. The schematic representations of the constructs are presented in the corresponding figures. VEEV helper RNA-encoding plasmids and that encoding the VEEV genome, pVEEV/GFP/C1, were described elsewhere (13, 23). The capsid protein of this VEEV TC-83-based virus contained redundant mutations in the nuclear localization signal (NLS) and peptide connecting helix I and the NLS. These mutations made VEEV dramatically less cytopathic. All of the sequences and details of the cloning procedures can be provided upon request.

RNA transcriptions.

Replicon-, viral genome- and helper RNA-encoding plasmids were purified by centrifugation in CsCl gradients. They were linearized using the MluI restriction site located in all of the constructs downstream of the poly(A) sequence. RNAs were synthesized with SP6 RNA polymerase in the presence of a cap analog using previously described conditions (24). The yield and integrity of transcripts were analyzed by gel electrophoresis, and aliquots of transcription reaction mixtures were directly used for electroporation (25). Replicon RNAs were coelectroporated into the cells together with helper RNAs, and released viral particles were harvested at 24 h postelectroporation. Titers were determined by infecting BHK-21 cells with different dilutions of harvested particles and staining them with either VEEV nsP2-specific or Flag-specific monoclonal antibodies and secondary AlexaFluor555-labeled antibodies. Numbers of infected cells were assessed by fluorescence microscopy.

Analysis of protein synthesis.

BHK-21 cells in 6-well Costar plates (5 × 105 cells/well) were infected with packaged VEEV replicons encoding different Flag-PARP fusions, or PARP12L in reverse orientation, at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 20 infectious units per cell. At the indicated times postinfection, cells were extensively washed with PBS and then incubated for 30 min in methionine-deficient Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM) supplemented with 0.1% FBS and 20 μCi/ml of [35S]methionine (26). Cells were then scraped, pelleted, lysed in equal volumes of sample buffer, and analyzed by SDS-PAGE. Dried gels were first exposed to film and further analyzed on a Storm phosphorimager.

Analysis of viral replication.

Cells (5 × 105) were seeded into 6-well Costar plates and after incubation for 4 h at 37°C in a CO2 incubator were infected with the packaged replicons at an MOI of 20 infectious units per cell. At 1 h postinfection, they were superinfected with VEEV/GFP/C1 virus at an MOI of 1 PFU/cell. At the times after the second infection indicated in the corresponding figures, medium was replaced, and titers of the released virus were determined by plaque assay on BHK-21 cells (27).

Immunofluorescence analysis.

For confocal microscopy, cells were seeded onto 8-well μ-slides (Ibidi GmbH, Munich, Germany), infected at an MOI of 20 infectious units per cell, and incubated at 37°C in a CO2 incubator. At 6 h postinfection, they were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 20 min at room temperature, permeabilized, and blocked with PBS supplemented with 0.5% Triton X-100 and 5% goat serum for 30 min. They were then stained with mouse monoclonal antibodies (Sigma) specific to Flag tag and secondary goat anti-mouse antibodies labeled with Alexa Fluor 555 (Invitrogen) as described elsewhere (28). Images were acquired on a Zeiss LSM700 confocal microscope with a 63×, 1.4-numerical aperture (NA) PlanApochromat oil objective.

Immunoprecipitation.

BHK-21 cells (2.5 × 107) were infected at an MOI of 20 infectious units per cell with packaged VEEV replicons encoding different PARPs. At 6 h postinfection, cell monolayers were rinsed twice with ice-cold PBS and harvested. Cells were pelleted by centrifugation at 1,000 × g at 4°C for 10 min, resuspended in 1 ml of hypotonic buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 5 mM MgCl2, 10 mM NaCl, 1× protease inhibitor cocktail [Sigma-Aldrich]), and incubated on ice for 15 min. Then cells were broken with 40 strokes in a Dounce homogenizer (29). Nuclei were pelleted at 900 × g for 10 min at 4°C. The NaCl concentration in the supernatants was adjusted to 150 mM, and samples were treated with 1% Nonidet P-40 for 30 min on ice. Samples were additionally clarified by centrifugation at 15,000 × g at 4°C for 10 min. Supernatants were incubated with anti-Flag M2 magnetic beads (Sigma-Aldrich) for 2 h at 4°C. The beads were then thoroughly washed with 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5)–5 mM MgCl2–150 mM NaCl–1% NP-40–1× protease inhibitor cocktail, and proteins were eluted with the SDS-PAGE loading buffer. Equal volumes of the samples were loaded for 10% SDS-PAGE. After electrophoresis, the Coomassie blue-stained bands were excised and submitted for mass spectrometry analysis to the UAB Mass Spectrometry/Proteomics Shared Facility.

Fractionation of polysomes and PARP complexes.

BHK-21 cells (107) were infected with packaged VEEV replicons at an MOI of 20 infectious units per cell. At the times postinfection indicated in the figures, cells were incubated in complete medium supplemented with cycloheximide (CHX) at a concentration of 0.05 mg/ml for 10 min. They were then washed three times with cold PBS, harvested in ice-cold PBS supplemented with 0.1 mg/ml of CHX, and pelleted for 6 min at 1,000 × g at 4°C. Pellets were resuspended in 0.5 ml of lysis buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 25 mM KCl, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mg/ml CHX, 10 μl/ml of RNase OUT [Invitrogen], 1× protease inhibitor cocktail [Sigma-Aldrich], 1% Nonidet P-40 [Roche]). Lysis was carried out for 15 min on ice with occasional vortexing. Depending on the experiment, MgCl2 or RNase OUT in the lysis buffer was replaced with either 10 mM EDTA or 4 μg/ml of RNase A. Nuclei were pelleted at 15,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. The supernatants were layered on top of a continuous sucrose gradient (5% to 50% [wt/wt], containing 10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 25 mM KCl, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2 [or 5 mM EDTA]). Samples were centrifuged for 2 h in an SW-40 rotor (Beckman) at 39,000 rpm and 4°C (30). After centrifugation, the gradients were fractionated on a Fraction recovery system (Beckman). The A254 readings were monitored and recorded using an Econo system (Bio-Rad). Each fraction (0.7 ml) was collected into tubes with 600 μl of 50% (wt/wt) sucrose cushion and subjected to a second centrifugation for 1.5 h in a TLA 55 rotor (Beckman) at 54,000 rpm and 4°C. Pellets were resuspended in protein loading buffer and analyzed by Western blotting using anti-Flag M2 antibodies (Sigma-Aldrich), polyclonal rabbit anti-RPL7a antibodies (Bethyl), and infrared dye-labeled secondary antibodies and scanned on a Li-Cor imager.

RESULTS

PARP7, PAPR10, and PARP12L are potent inhibitors of cellular translation.

In our previous study (11), we demonstrated that expression of the long isoform of murine PARP12 (PARP12L) or PARP7 and PARP10 proteins strongly inhibited replication of a variety of RNA viruses. However, the mechanisms of the antiviral activities of these proteins were not further investigated. Moreover, in general, functions of these PARP family members, particularly their activities in inhibition of viral replication, are greatly understudied, and their mechanism of function in downregulation of virus replication has not been described in the literature.

The indirect data from the analysis of replication of VEEV variants expressing the GFP marker in the presence of PARP12L (11) suggested that the antiviral function of this protein might be in either the inhibition of translation of virus-specific RNAs or specific inhibition of synthesis of virus-specific RNAs. These were also the most plausible explanations for PARP12's inhibitory effect on replication of the broad spectrum of viruses it was tested against (11). To distinguish between these possibilities and further understand the function of the IFN-inducible PARP family members, we designed a set of VEEV-based replicons which encoded the full-length PARP7, PARP10, and PARP12L (Fig. 1A and B) fused with Flag tag at their amino termini. The common characteristics of these PARPs were the presence of putative RNA-binding motifs in their amino-terminal domains (Fig. 1A) (16) and the induction of their expression during type I IFN treatment (11). The control construct contained a PARP12L gene in reverse orientation (PARP12rev) downstream of the subgenomic promoter (Fig. 1B). Thus, the control VEErep/PARPrev replicon was of the same length as that encoding PARP12L and consequently was expected to demonstrate similar RNA replication efficiency. The VEEV replicon-based expression system was chosen instead of using a more widely used, transient, plasmid-based expression approach because of a number of important advantageous characteristics (23, 31). First, replicons can be packaged into infectious viral particles and then delivered into all of the cells, even into the cells which demonstrate very low efficiency of transfection by plasmid DNA, for expression of genes of interest. Second, upon delivery into the cells, replicons start to synchronously express cloned heterologous genetic material within the first hour postinfection, rather than after the 16- to 24-h period required to start expression from plasmid DNA. The lack of uninfected cells and resultant expression of the heterologous gene in the entire cell population allows for quantitative analysis of the effects of the expressed proteins on the main cellular functions. These features made VEEV replicons the only expression system which could be applied for this study. Third, in contrast to more widely used Old World alphavirus replicons, derived from SINV and Semliki Forest virus (SFV) (32–34), the VEEV-based expression systems do not noticeably affect either cellular transcription or translation (35–37), and thus their replication does not interfere with the effects of the expressed heterologous proteins (see Fig. 2 and subsequent figures).

FIG 1.

PARP7, PARP12L, and PARP10 fused with Flag tag efficiently inhibit VEEV replication. (A) Schematic representation of the PARP7, PARP12L, and PARP10 proteins. The amino-terminal, putative RNA-binding, and PARP domains are indicated. (B) Schematic representation of VEEV replicons encoding different PARPs under the control of the subgenomic promoter. The second promoter drives expression of the Pac gene. (C) BHK-21 cells were infected with the indicated packaged replicons at an MOI of 20 infectious units per cell. At 1 h postinfection, they were superinfected with VEEV/GFP/C1 virus (see Materials and Methods for details) at an MOI of 1 PFU/cell. At the indicated times after the second infection, medium was replaced, and titers of the released virus were determined by plaque assay on BHK-21 cells.

FIG 2.

Expression of PARP7, PARP10, and PARP12L strongly affects cellular translation. (A) BHK-21 cells in 6-well Costar plates (5 × 105 cells/well) were infected at an MOI of 20 infectious units per cell with packaged VEEV replicons encoding PARP7, PARP10, and PARP12L fused with Flag tag (see Materials and Methods for details) or VEErep, encoding PARP12L in reverse orientation. At the indicated times postinfection, proteins were metabolically pulse-labeled with [35S]methionine. Cell lysates were analyzed by SDS-PAGE followed by autoradiography. (B) Results of analysis of the same gels on a Storm phosphorimager. The radioactivity in the gel fragments containing cellular proteins of 15 to 42 kDa was measured and normalized to the levels from the same fragments in mock-infected cells. (C) Quantitative Western blot analysis of PARP7, PARP10, and PARP12L accumulation at 4 and 8 h postinfection (PI) by replicons. Protein levels were analyzed using a Flag-specific monoclonal antibody (MAb) and secondary infrared dye-labeled Abs. Images were acquired and processed on a Li-Cor imager.

Replicons were packaged into infectious virus particles using previously developed helper RNAs (23). BHK-21 cells were infected with the designed constructs at the same MOI and 1 h later were superinfected with one of the VEEV variants, VEEV/GFP/C1, encoding green fluorescent protein (GFP) under the control of the subgenomic promoter. A 1-h-long period between infections is insufficient for the replicon to induce superinfection exclusion (11). However, it provides an opportunity to initiate synchronous expression of heterologous, replicon-carried genes before the superinfecting virus begins to replicate. Replicons encoding PARP12L, PARP7, and PARP10 fused with Flag tag, but, importantly, not PARP12rev, demonstrated a strong negative effect on the following VEEV replication (Fig. 1C). At any time postinfection with VEEV/GFP/C1, titers of the virus released from the PARP-expressing cells remained a few orders of magnitude lower than those detected in the control cells containing VEErep/PARP12rev. These data suggested that (i) expression of the indicated PARPs has a profound inhibitory effect on VEEV replication and (ii) the presence of the Flag tag at the amino termini of the indicated PARPs does not make them incapable of inhibiting VEEV replication.

In the next experiments, we infected cells with packaged PARP7-, PARP10-, and PARP12L-encoding replicons and, at different times postinfection, metabolically labeled synthesized proteins with [35S]methionine to assess the effect of PARP expression on cellular translation. The results presented in Fig. 2A and B demonstrate that expression of any of the indicated PARPs had a deleterious effect on the cellular translational machinery. By 8 h postinfection, all of the expressed PARPs had globally downregulated cellular translation to almost undetectable levels. PARP12L, PARP10, and PARP7 not only inhibited translation of cellular proteins but also appeared to strongly downregulate their own expression and expression of other proteins encoded by the replicon genome (Fig. 2A, Pac expression). PARP expression from replicons was highest early postinfection but was significantly lower than we normally find for heterologous proteins expressed from VEEV replicons (data not shown). The results of quantitative Western blotting presented in Fig. 2C demonstrate that at 4 and 8 h postinfection, the levels of accumulated PARPs remained essentially the same, and no biologically irrelevant overproduction was achieved. The control replicon VEErep/PARP12rev did not noticeably interfere with cellular translation (Fig. 2A and B). Thus, in agreement with our previously published data, in contrast to the replicons derived from the Old World alphaviruses, such as SINV or SFV, replication of VEErep RNA itself had no profound negative effect on the cellular translational machinery (23, 31). Taken together, the data demonstrated that even low levels of PARP7, PARP10, and PARP12L expression from VEEV replicons strongly affect translation of both replicon genome-encoded and cellular proteins. This provides a plausible explanation for the previously detected negative effect of PARP expression on replication of VEEV and other RNA viruses (11).

The carboxy-terminal domain of PARP12L plays a critical role in translation inhibition and antiviral function.

As we indicated, the members of the PARP family which we used in the above-described and other experiments demonstrate a common structural characteristic, in that they contain a PARP catalytic domain and a large amino-terminal, putative RNA-binding domain (16). Previously published data about PARP13, another member of the PARP family (18), suggested that its short isoform, containing only the RNA-binding domain, was capable of exhibiting a broad antiviral effect, indicating that this domain, but not the PARP domain, plays a critical role in downregulation of virus replication. To understand whether this mechanism of function in the development of the antiviral effect is common for other PARPs, we selected PARP12 for further experiments. We separately expressed its short isoform PARP12S (termed PARP12-N), representing the amino-terminal, putative RNA-binding domain, and the carboxy-terminal PARP domain (PARP12-C) from VEEV replicons (Fig. 3A). In both constructs, the indicated domains were also fused with the Flag tag, which allowed us to monitor the expression levels and define the titers of packaged replicons. Replicons were packaged into infectious viral particles using helper RNAs. Cells infected with these particles demonstrated expression of both Flag fusions at notably higher levels than that of Flag-PARP12L (Fig. 3B). Surprisingly, PARP12-N exhibited no signs of translation inhibition, and only the PARP domain (PARP12-C) was able to downregulate cellular translation, albeit not as efficiently as did the full-length PARP12L (Fig. 3C and D). Next, cells were infected with the designed constructs at the same MOI and superinfected with replication-competent VEEV/GFP/C1 virus. In good correlation with translation-inhibitory function, PARP12-C (PARP domain), but not PARP12-N, negatively affected VEEV replication (Fig. 3E). These data suggested that (i) the presence of both domains is optimal for PARP12L to be a potent translation inhibitor and (ii) the PARP12-N domain appears either to have a less important function in viral replication inhibition or not to have a defined function in this process at all.

FIG 3.

The amino-terminal (PARP12-N) and carboxy-terminal (PARP12-C) domains, representing the natural short isoform of PARP12 and the PARP domain, respectively, are less efficient inhibitors of cellular translation. (A) Schematic representation of VEEV replicons encoding different fragments of PARP12 and PARP12L in reverse orientation. (B) Quantitative analysis of expression of different forms of PARP12. Cell lysates were prepared at 8 h postinfection with replicons. Protein levels were analyzed using a Flag-specific MAb and secondary infrared dye-labeled Abs. Images were acquired and processed on a Li-Cor imager. (C) BHK-21 cells in 6-well Costar plates (5 × 105 cells/well) were infected with packaged VEEV replicons encoding PARP12-N, PARP12-C, and PARP12L fused with Flag tag (see Materials and Methods for details) or VEErep, encoding PARP12L in reverse orientation, at an MOI of 20 infectious units per cell. At the indicated times postinfection, proteins were metabolically pulse-labeled with [35S]methionine. Cell lysates were analyzed by SDS-PAGE followed by autoradiography. (D) Results of analysis of the same gels on a Storm phosphorimager. The radioactivity in gel fragments containing cellular proteins of 15 to 42 kDa was measured and normalized to the levels from the same fragments in mock-infected cells. (E) BHK-21 cells were infected with the indicated packaged replicons at an MOI of 20 infectious units per cell. At 1 h postinfection, they were superinfected with VEEV/GFP/C1 virus at an MOI of 1 PFU/cell. At the indicated times after the second infection, medium was replaced, and titers of the released virus were determined by plaque assay on BHK-21 cells.

Translation-inhibitory functions of PARP12L depend on its catalytic activity and autoribosylation.

The ability of PARPs to cause a strong inhibitory effect on cellular translation upon their expression at low levels suggested a possibility of a catalytic rather than a stoichiometric mode of function. In contrast to the case for many other ISGs, information about biological activities of PARPs is very limited, and their effects on cellular translation and, thus, downregulation of virus replication have not been described. However, PARP10 (and most likely PARP7 and PARP12) is known to exhibit mono(ADP-ribose) transferase activity instead of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase activity, which results in transfer of a single ADP ribose rather than multiple ADP-ribose moieties (38). The crystal structure of the PARP domain in human PARP12 has also been resolved (PDB code 2PA9), and models of the PARP12 and PARP10 catalytic centers were developed. It has been experimentally demonstrated that an E882A mutation in PARP10 (corresponding to E569 in murine PARP12L) has the most prominent effect on autoribosylation of this protein, suggesting that it is positioned in the main acceptor site. Thus, based on the available structural and biochemical information, we introduced H574A and E569A mutations into PARP12L, which were expected to inactivate the protein's catalytic activity and strongly affect its autoribosylation, respectively. The corresponding replicons were termed VEErep/PARP12L-mCat and VEErep/PARP12L-mAcc (Fig. 4A). After packaging into infectious viral particles, they were used to infect cells. Mutated proteins were expressed from VEEV replicons more efficiently than the original Flag-PARP12L, and in the following experiments, PARP12L-mCat and PARP12L-mAcc were tested for their ability to affect cellular translation. Both mutations strongly reduced the ability of PARP12L to cause translational shutoff (Fig. 4C and D). The mutants caused translation inhibition only at late times postinfection. Nevertheless, both of them remained efficient in inhibition of VEEV/GFP/C1 virus replication (Fig. 4E). A potential explanation for this discrepancy between the rates of translational shutoff development and the ability of PARP12L mutants to inhibit virus replication may be that ribosylation and inhibition of cellular translation are different methods available to PARP12L to inhibit VEEV replication. Thus, the results suggest that similar to previously published PARP13-related data (22, 39, 40), PARP12L and the other PARPs used in this study apparently have a complicated mode of function utilizing more than one mechanism.

FIG 4.

Ribosylation of PARP12L is required for its translation inhibition functions. (A) Schematic representation of VEEV replicons encoding PARP12L in reverse orientation, Flag-PARP12L, or Flag-PARP12L with an H574A mutation in the catalytic site of the PARP domain (PARP12L-mCat variant) or an E569A mutation in its acceptor site (PARP12L-mAcc variant). (B) Quantitative analysis of expression of the indicated PARP12L mutants. Cell lysates were prepared at 8 h postinfection with replicons. The protein level was analyzed using a Flag-specific MAb and secondary infrared dye-labeled Abs. Images were acquired and processed on a Li-Cor imager. (C) BHK-21 cells in 6-well Costar plates (5 × 105 cells/well) were infected with packaged VEEV replicons encoding Flag-PARP12-mCat and Flag-PARP12L-mAcc at an MOI of 20 infectious units per cell. At the indicated times postinfection, proteins were metabolically pulse-labeled with [35S]methionine. Cell lysates were analyzed by SDS-PAGE followed by autoradiography. (D) Results of analysis of the same gels on a Storm phosphorimager. The radioactivity in gel fragments containing cellular proteins of 15 to 42 kDa was measured and normalized to the levels from the same fragments in mock-infected cells. (E) BHK-21 cells were infected with the indicated packaged replicons at an MOI of 20 infectious units per cell. At 1 h postinfection, they were superinfected with VEEV/GFP/C1 virus at an MOI of 1 PFU/cell. At the indicated times after the second infection, medium was replaced, and titers of the released virus were determined by plaque assay on BHK-21 cells.

In additional experiments, we tested whether the detected effects of PARP12 and its mutants on cellular translation are specific to BHK-21 cells. NIH 3T3 cells were infected with the packaged replicons indicated in Fig. 5, and the efficiency of cellular translation was evaluated at 7 h postinfection. As in BHK-21 cells, expression of PARP12L, PARP7, PARP10, and PARP12-C, but not other mutants, caused profound inhibition of cellular translation. Thus, the inhibitory functions of PARPs are not specific to BHK-21 cells only, and the data are likely applicable to other cell lines. However, it should be noted that the kinetics of shutoff induction might vary depending on the cell type.

FIG 5.

PARP proteins and their mutants cause translational shutoff in NIH 3T3 cells with efficiencies similar to those detected in BHK-21 cells. NIH 3T3 cells in 6-well Costar plates (5 × 105 cells/well) were infected with the indicated packaged VEEV replicons at an MOI of 20 infectious units per cell. At 7 h postinfection, proteins were metabolically pulse-labeled with [35S]methionine. Cell lysates were analyzed by SDS-PAGE followed by autoradiography. The radioactivity in gel fragments containing cellular proteins of 15 to 42 kDa was measured on a Storm phosphorimager and normalized to the levels from the same fragments in mock-infected cells.

Mutations in PARP12L affect its cytotoxicity.

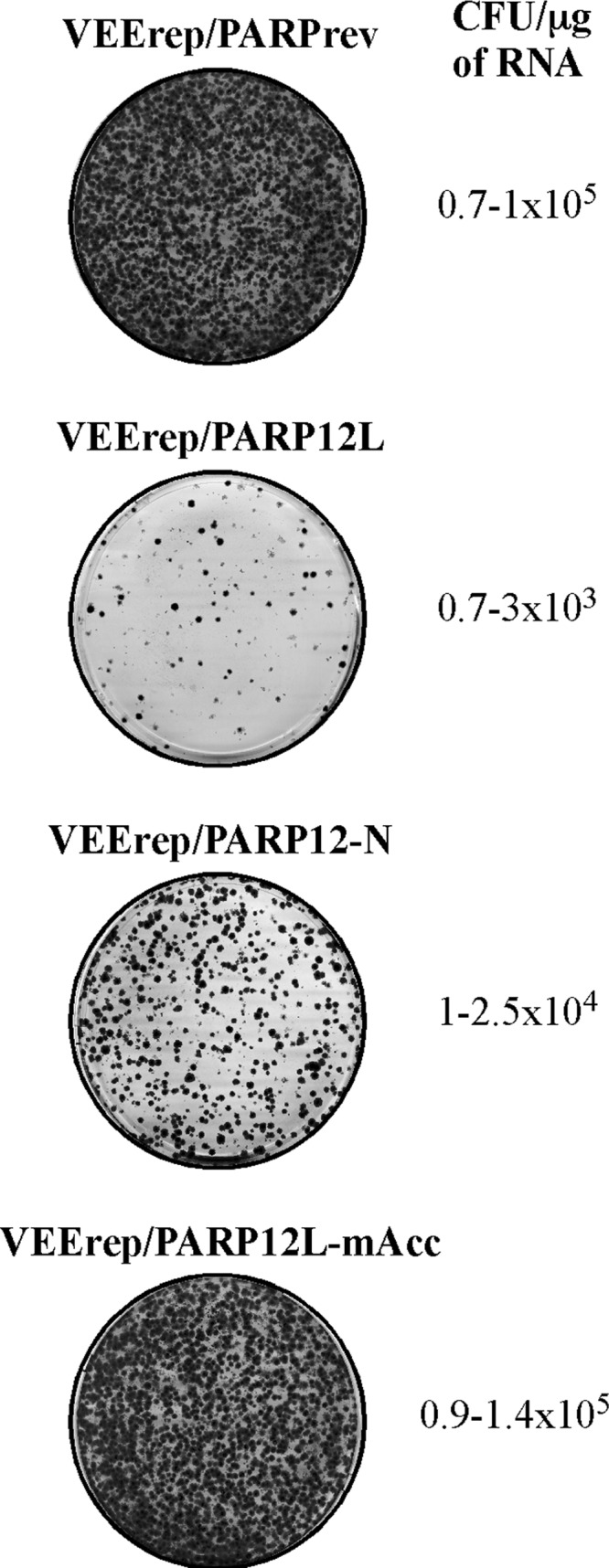

In additional experiments, we tested the cytotoxic effects of different forms of PARP12. In the applied cytotoxicity assay (41), we electroporated the designed in vitro-synthesized replicon RNAs, encoding different PARPs, and a Pac gene under the control of the subgenomic promoters into BHK-21 cells, seeded different numbers of cells into the dishes, and within a few days selected Purr colonies and evaluated their numbers (Fig. 6). In good correlation with our previous data, VEErep/PARPrev formed a very high number of colonies (105 colonies per μg of electroporated RNA), VEErep/PARP12L/Pac produced colonies 100-fold less efficiently, and other replicons demonstrated intermediate efficiencies of colony formation. The randomly selected colonies formed by VEErep/PARP12L/Pac contained replicon RNAs with point mutations in the PARP12L gene, which may have reduced the efficiency of the proteins' inhibitory functions. One of the identified mutations disrupted the open reading frame after aa 380, and another, V523M, could affect its catalytic activity. However, further investigation of its effect on cell metabolism was not in the scope of this study.

FIG 6.

PARP12L variants demonstrate different levels of cytotoxicity. Equal amounts of in vitro-synthesized RNAs representing VEEV replicons encoding PARP12 in reverse orientation, Flag-PARP12L, Flag-PARP12-N, and Flag-PARP12L-mAcc, were electroporated into BHK-21 cells. Different numbers of cells were then seeded into dishes, and colonies of Purr cells were selected. Stained colonies in the dishes, which initially contained equal numbers of electroporated cells, are presented. The efficiency of formation of Purr colonies was measured in CFU per μg of RNA used for electroporation.

PARP12L interacts with ribosomes.

The experiments described above strongly suggested that the long isoform of PARP12 and other studied PARPs are capable of strong modification of cellular translational machinery and thus might form complexes with cellular translation factors and/or ribosomes. To test this possibility, we infected BHK-21 cells with the packaged replicons encoding the Flag-PARP12L fusion and, at 6 h postinfection, immunoprecipitated protein complexes from cell lysates using magnetic beads loaded with anti-Flag monoclonal antibodies (see Materials and Methods for details). This particular time point was chosen because it is late enough to observe a strong inhibition of translation but is still early enough that the effect of this inhibition does not produce a strong secondary effect on the concentration of host proteins. The precipitated proteins were analyzed by SDS-PAGE, gel fragments were excised, and proteins were identified by mass spectrometry. Samples derived from the cells containing VEErep/PARP12L and VEErep/PARP12-N replicons demonstrated the presence of numerous ribosomal proteins and some translation initiation and elongation factors, suggesting a possibility of the direct interaction of PARP12 with the cellular translation apparatus (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Mass spectrometry-based identification and quantification of proteins interacting with PARP12

| Proteina | No. of spectral counts per sample |

|

|---|---|---|

| PARP12-N | PARP12L | |

| Ribosomal proteins | ||

| Rps3 | 91 | 92 |

| Rpl7a | 39 | 81 |

| Rplp0 | 21 | 60 |

| Rps6 | 25 | 48 |

| Rpl8 | 27 | 27 |

| Rps2 | 0 | 18 |

| Rpl3 | 0 | 15 |

| Rpl5 | 111 | 0 |

| Rps3a | 12 | 0 |

| Rpsa | 0 | 15 |

| Proteins involved in translation initiation and elongation | ||

| Pabp1 | 527 | 330 |

| Eef1a1 | 131 | 140 |

| Eef1g | 36 | 39 |

| Eef2 | 18 | 30 |

| Eif4b | 9 | 79 |

| Eif4a1 | 12 | 26 |

All proteins were identified by at least 4 unique peptides with a probability of >99%.

PARP12L and its domains form different types of complexes with cellular translational machinery.

The coimmunoprecipitation (co-IP) experiments indicated that PARP12L, which we were most interested in, might directly interact with the cellular translational machinery and with ribosomes in particular. Therefore, to experimentally test this possibility, in the next experiments we used ultracentrifugation in sucrose density gradients to fractionate the lysates of the cells expressing different forms of PARP12 and then analyzed the ribosome/polysome profiles and PARP distribution. Cells were infected by the PARP-encoding VEEV replicons, and lysates were prepared at 4 h postinfection (see Materials and Methods for details). Flag-PARP12L was detected mostly in the polysome-containing fractions (Fig. 7A). Addition of EDTA to cell lysates, which leads to ribosome disassembly, caused relocalization of PARP12L to fractions located higher in the sucrose gradients. A straightforward conclusion to draw from these observations is that PARP12L is capable of interacting with ribosomes in the polysome-containing fractions. However, following EDTA treatment, PARP12L was readily detectable in fractions which did not contain ribosome subunits (Fig. 7A). This result was further confirmed by treatment of the lysates with RNase A (Fig. 7B), which also resulted in distributions of Flag-PARP12L and 80S ribosomes in different fractions. Importantly, at later times postinfection with VEErep/PARP12L, both polysomes and PARP12L are no longer present in the low fractions (Fig. 8A). In the lysates prepared at 12 h postinfection, the main pool of PARP12L was found in the complexes which cosedimented with the 80S ribosomes. This synchronous disappearance of PARP12L and polysomes from the lower fractions of the gradients and the results presented in the following sections indicate that at least a fraction of PARP12L is associated with the polysomes. The control samples were prepared from cells infected with VEErep/PARPrev (Fig. 8B). As expected, replication of replicon RNA itself did not have a deleterious effect on the polysomes. They were readily detectable even in samples prepared at 12 h postinfection.

FIG 7.

Upon expression in BHK-21 cells, the long isoform of PARP12 (PARP12L) forms two types of complexes. (A) BHK-21 cells were infected with packaged replicon VEErep/PARP12L at an MOI of 20 infectious units per cell. At 4 h postinfection, cells were harvested and lysed with NP-40. After pelleting the nuclei, the lysates were either directly analyzed by ultracentrifugation in the sucrose gradients and fractionated as described in Materials and Methods or additionally incubated prior to ultracentrifugation in the presence of 10 mM EDTA to disassemble ribosomes. Ribosomes and their subunits and other protein complexes were pelleted by another round of ultracentrifugation and further analyzed by quantitative Western blotting using Flag-specific MAbs and antibodies specific to the ribosomal RPL7a protein, which is located in the 60S ribosomal subunit. Images were acquired and processed using a Li-Cor imager. The lower panel presents the results of quantitative analysis of Flag-PARP12L distribution in the sucrose gradient. The intensity of the signal in each fraction was normalized to the highest concentration of Flag-PARP12L. (B) Cells were infected and lysates were analyzed as described above except that before ultracentrifugation, they were treated with 4 μg/ml of RNase A to destroy polysomes. The lower panel presents the results of quantitative analysis of PARP12L and 60S ribosomal subunit distribution in the sucrose gradients. The intensity of the signal in each fraction was normalized to the signal detected in the fractions containing highest concentration of Flag-PARP12L or RPL7a. These experiments were repeated twice with essentially the same results.

FIG 8.

Expression of PARP12L, but not replication of VEErep itself, leads to destruction of polysomes. (A) BHK-21 cells were infected with packaged replicon VEErep/PARP12L at an MOI of 20 infectious units per cell. At 12 h postinfection, cells were harvested and lysed with NP-40, and the lysate was analyzed without additional treatment by ultracentrifugation in a sucrose gradient. Ribosomes, their subunits, and other protein complexes were pelleted from the fractions by additional ultracentrifugation and further analyzed by quantitative Western blotting using Flag-specific MAbs and antibodies specific to ribosomal RPL7a protein. Images were acquired and processed on a Li-Cor imager. The lower panel presents the results of quantitative analysis of Flag-PARP12L and 60S ribosomal subunit distribution in the sucrose gradient. The data were normalized to the signals detected in the fractions containing the highest concentrations of Flag-PARP12L and 60S subunit. (B) BHK-21 cells were infected with packaged VEErep/PARPrev replicon at an MOI of 20 infectious units per cell. At 4 and 12 h postinfection, cells were harvested and lysed with NP-40, and the lysates were analyzed without additional treatment by ultracentrifugation as described above for panel A.

Taken together, the data suggested that PARP12L was likely capable of forming two types of complexes. The first type is characterized by PARP interaction with ribosomes in the polysome fraction. The second has a different content, and the next experiments demonstrated that these complexes contain RNA rather than ribosomes.

In parallel experiments, we analyzed the distribution of Flag-PARP12-C and Flag-PARP12-N domains in the sucrose gradients (Fig. 9). The Flag-PARP-C domain was found to cosediment with the ribosomes and was located predominantly in the polysome-containing fractions (Fig. 8A). However, neither EDTA nor RNase A treatment led to its complete relocalization to the monosome or the ribosome subunit-containing fractions of the gradients. Importantly, in the cell lysates, the preformed complexes were sensitive to RNase A but not EDTA, and exposure to RNase detectably affected the rates of complex sedimentation. This was an indication that a large fraction of Flag-PARP12-C was present in complexes which were not associated with ribosomes but had an RNA component.

FIG 9.

The amino-terminal (PARP12-N) and the carboxy-terminal (PARP-C) domains of PARP12L form different complexes. BHK-21 cells were infected with packaged replicon VEErep/PARP12-C (A) or VEErep/PARP12-N (B) at an MOI of 20 infectious units per cell. At 4 h postinfection, cells were harvested and lysed with NP-40. After pelleting the nuclei, the lysates were either directly analyzed by ultracentrifugation in the sucrose gradients and fractionated as described in Materials and Methods or additionally incubated in the presence of 10 mM EDTA to disassemble ribosomes or with RNase A at concentration of 4 μg/ml for 15 min on ice to degrade polysomes. Ribosomes and their subunits and other protein complexes were pelleted by another round of ultracentrifugation as described in Materials and Methods and further analyzed by quantitative Western blotting using Flag-specific MAbs and antibodies specific to ribosomal RPL7a protein. Images were acquired and processed using a Li-Cor imager. The lower panels present the results of quantitative analysis of Flag-PARP12-C and Flag-PARP12-N distribution in the sucrose gradient. The intensity of the signal in each fraction was normalized to the highest concentration of Flag-PARP12L.

The amino-terminal PARP12-N domain, representing a natural short isoform of PARP12 (PARP12S), in contrast, was always found in the ribosome or ribosome subunit-containing fractions of the gradients (Fig. 9B). Fractionation of lysates derived from the cells infected with VEErep/PARP12-N revealed a strong colocalization of this protein with polysomes. Treatment of the lysates with RNase A or EDTA caused relocalization of PARP12-N to monosome and ribosome subunit-containing fractions, respectively.

The ribosylation mutant of PARP12L demonstrated a distribution in the sucrose gradients very similar to that described above for PARP12L. It also formed complexes which were present in the polysome-containing fractions, and after EDTA treatment, PARP12L-mCat complexes were located mostly in the upper fractions of the gradients (Fig. 10). Thus, mutation in the catalytic site strongly affected the rates of translational shutoff development (Fig. 4) but had only a minor effect on intracellular complex formation.

FIG 10.

Mutation in PARP12L catalytic site does not abrogate formation of protein complexes. BHK-21 cells were infected with packaged VEErep/PARP12L-mCat replicon at an MOI of 20 infectious units per cell. At 4 h postinfection, cells were harvested and lysed with NP-40. After pelleting the nuclei, the lysates were either directly analyzed by ultracentrifugation in sucrose gradients and fractionated as described in Materials and Methods or additionally incubated in the presence of 10 mM EDTA to disassemble ribosomes. Ribosomes and their subunits and other protein complexes were pelleted by another round of ultracentrifugation as described in Materials and Methods and further analyzed by quantitative Western blotting using Flag-specific MAbs and antibodies specific to ribosomal RPL7a protein. Images were acquired and processed using a Li-COR imager. The lower panel presents the results of quantitative analysis of Flag-PARP12L-mCat distribution in the sucrose gradient. The intensity of the signal in each fraction was normalized to the highest concentration of Flag-PARP12L-mCat.

The data from the immunostaining-based experiments (Fig. 11) were in good agreement with the above-described analysis of complex formation. Flag-PARP12L, Flag-PARP7, and Flag-PARP10 proteins were detected in the cells in small granules. In support of the previously published data, Flag-PARP10 was found to also form larger, spherical complexes (42). Flag-PARP12-C accumulated both in small granules and in larger complexes, and this likely explains the detection of high-molecular-weight complexes in the sucrose gradients even after RNase A or EDTA treatments. In contrast, Flag-PARP12-N, representing the natural short isoform of PARP12, demonstrated the most diffuse distribution, indicating a different mode of function from that of the other PARP domain-containing proteins. Flag-PARP12L-mAcc and Flag-PARP12L-mCat were distributed in the cells in a fashion similar to that for Flag-PARP12L. This was an additional indication that PARP12L-specific complexes and enzymatic activity of PARP12 function differently in mediating development of translational shutoff and inhibition of VEEV replication.

FIG 11.

PARPs and their mutants demonstrate different intracellular distributions. BHK-21 cells seeded in Ibidi 8-well μ-slides were infected with the indicated packaged replicons at an MOI of 20 infectious units per cell. At 6 h postinfection, cells were fixed, permeabilized, and stained with a Flag-specific MAb and an Alexa Fluor 555-labeled secondary antibody. Images are presented as maximum-intensity projections of 6 optical sections. Bars correspond to 10 μm.

Taken together, these data and the results of co-IP experiments suggest that PARP12L is capable of direct interaction with ribosomes, and this likely at least partially determines its inhibitory effect on cellular translation and its antiviral function. This binding is mediated mostly by the amino-terminal domain of PARP12L, which was previously proposed to contain RNA-binding motifs. The strong dependence of the rates of translational shutoff on the ribosylation function of the PARP domain and the ability of this domain and the entire PARP domain-containing protein to form additional RNA-containing complexes also suggest the possibility of more than one mechanism of PARP function in the development of the antiviral response.

DISCUSSION

Great progress has been made in understanding the mechanisms of the mammalian innate immune response during replication of numerous viruses (1). Infected cells rapidly sense virus replication and activate a very broad combination of genes whose products either directly function in downregulation of virus replication or mediate cell signaling (7). The highlight of the cell signaling is the release of type I IFN, which activates the antiviral state in uninfected cells and thus prevents the next rounds of infection. Moreover, the released type I IFN also functions in an autocrine fashion and activates additional ISGs in already-infected cells. The latter ISG products either downregulate virus replication or can even completely clear replicating virus from already-infected cells. The distinguishing characteristic of the type I IFN-induced antiviral response is its high level of redundancy, with more than 300 cellular genes activated (11). However, none of their products appear to have a dominant antiviral function. This high level of redundancy, with hundreds of genes involved, makes selection of resistant virus variants a highly unlikely event. Unfortunately for researchers, the redundancy of the ISG system, its virus-, host-, and cell type-dependent mode of function, and the small antiviral effects of each product make the dissection of the mechanism of function of each component a difficult task. An additional complication comes from the ability of many, if not all, viruses to interfere with the function of either particular key components or the entire host response by modifying individual signaling pathways or the entire intracellular environment (43–51).

In our previous studies, we have developed a variety of alphavirus-specific experimental systems which allow dissection of new processes in virus-host interactions (11, 13, 52) which play critical roles in infection development. We have used VEEV mutants which were incapable of inhibiting cellular transcription and cells defective in type I IFN signaling to define (i) cellular genes which were directly activated by replicating virus, (ii) cellular genes induced by IFN-β, and (iii) genes synergistically activated by IFN and virus replication (11). We also identified the spectrum of genes specifically activated during noncytopathic clearance of VEEV mutants from mouse fibroblasts but not activated during the persistent replication of the same mutants in IFN-α/βR−/− mouse embryo fibroblasts (MEFs), which are defective in type I IFN signaling. This reasonably small subset of ISGs contained a variety of genes, such as those for STAT1, PKR, RIG-I, and Toll-like receptor 3 (TLR3), whose products were already known to be involved in inhibition of replication of numerous viruses. However, some of the genes had not been previously implicated in exhibiting inhibitory antiviral functions. One of them, the long isoform of PARP12, attracted most of our attention due to a very strong effect on replication of not only alphaviruses but also viruses belonging to very distant families. Moreover, two other PARPs, PARP7 and PARP10, containing similar PARP domain and putative RNA-binding domain structures also exhibited a strong antialphavirus effect (11).

The results of this new study further demonstrate the previously unknown function of the indicated PARPs as antiviral proteins. PARP7, PARP10, and PARP12L were found to be very potent regulators of cellular translation. Their effect on translation was shown to be stronger than that described for a well-characterized ISG, the double-stranded RNA (dsRNA)-activated protein kinase PKR. PKR was one of the first antiviral proteins described. It interacts with virus-specific dsRNA, and this in turn leads to autophosphorylation and dimerization of PKR, making it capable of phosphorylating the α subunit of eukaryotic initiation factor 2 (eIF-2α) and thus inducing translation inhibition (53). However, PARP12L and most likely other PARPs (PARP7 and PARP10) appear to use a different mechanism to induce translational shutoff. The data suggest that PARP12L interacts directly with ribosomes. The ribosomal proteins were clearly determined by mass spectrometry in the protein complexes isolated from the Flag-PARP12L-expressing cells using Flag-specific antibodies (Abs). In other experiments, at early times postinfection with PARP12L-expressing replicons, PARP12L was found mostly in the polysome-containing fractions of the sucrose gradients. The amino-terminal domain of PARP12, representing its natural short isoform, was even more clearly associated with the ribosomes. Dissociation of the polysomes by EDTA treatment or their hydrolysis by RNase A resulted in PARP12-N relocalization to the ribosome subunit- and monosome-containing fractions, respectively. However, at later stages postinfection with the PARP12L-expressing replicons, polysomes are no longer detectable, and PARP12L is present in other complexes demonstrating sedimentation rates close to that of the 80S monosomes. Such complexes have a high A254 extinction, suggesting the presence of RNA, and are also sensitive to RNase A. The existence of this type of complex suggests that the mode of action of PARP12L and likely other PARPs used in this study is more complicated than simply interaction with the polysomes and is not limited to binding to ribosomes. In agreement with this hypothesis, the carboxy-terminal, PARP domain of PARP12 alone was sufficient to induce partial translational shutoff and inhibition of VEEV replication. However, the PARP domain itself did not demonstrate a detectable ability to interact with the ribosomal subunits and formed complexes which were almost certainly ribosome-free. Thus, the results of this study demonstrate that the antiviral function of PARP12L is mediated by its ability to interfere with cellular translation and that both domains of this protein are essential for rapid development of this phenomenon.

It is becoming more clear that PKR is not the only cellular protein involved in inhibiting cellular translation during virus replication. PARP7, PARP10, and PARP12L appear to also play a critical role in regulation of translation in virus-infected cells. Moreover, their ability to downregulate cellular translation does not necessarily mean that this is the only PARP-mediated antiviral mechanism. Their ability to form different types of complexes suggests other possibilities. Importantly, the catalytic ribosylation activity of the PARP domain plays a critical role in PARP12L function. Point mutations in the catalytic site and acceptor site strongly affect PARP12L's ability to cause translation inhibition (Fig. 4C and D), but the mutated protein remains capable of inhibiting VEEV replication (Fig. 4E).

Regulation of basic metabolism during virus replication and development of the antiviral response by ribosylation of critical host factors are likely to be relatively understudied processes. Most research efforts are now directed to understanding the regulation of cellular pathways via phosphorylation and dephosphorylation of the key components. However, the existence of a large family of PARPs and activation of at least some of its members by type I IFN and directly by viral RNA replication (11) highlight these proteins as important determinants of virus-host interactions and innate immune response development in particular. PARPs are already known to be involved in regulation of a number of critical processes, such as DNA repair, apoptosis, chromatin dynamics, cancer, and immune response development (54–57). Our results suggest that the list of their functions should also include regulation of cellular translation, at least during development of the antiviral response.

In summary, the results of this study provide new evidence that PARP7, PARP10, and the long isoform of PARP12 are ISGs which function in the development of the type I IFN-induced antiviral state and are important and very potent negative regulators of cellular translation during virus replication. The translation inhibition mediated by PARP12L appears to be a result of its direct binding to polysomes and complex formation with cellular RNAs. These interactions depend on the integrity of both the amino-terminal domain, containing a number of putative RNA-binding motifs, and the PARP domain. Importantly, the catalytic activity of the PARP domain also plays a critical role in translation inhibition. Based on the accumulated data, we hypothesize that type I IFN-specific induction of PARPs results in changes in cellular translation. These changes are likely not so severe as to threaten cell survival. However, as was previously demonstrated, even relatively small changes in translation efficiency have a dramatically more potent effect on the synthesis of virus-specific proteins rather than cellular proteins (58), thus making PARP-induced translational downregulation an important contributor to the overall development of the antiviral response. Our data also suggest a plausible explanation for the previously described PKR-independent component of the translational shutoff, which plays a critical role in regulation of alphavirus replication (26). The inability of PARP12L ribosylation mutants to efficiently interfere with cellular translation while retaining the ability to inhibit VEEV replication suggests the existence of more than one mechanism in the development of the latter phenomenon.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Niall J. Foy for helpful discussions and for critical reading and editing of the manuscript. We thank James Mobley and the members of the UAB CCC Bioanalytical and Mass Spectrometry Shared Facility for performing protein identification by mass spectrometry. We thank David McPherson, director of the molecular biology lab in the UAB Center for AIDS Research Virology Core, for technical assistance with ribosomal profiles.

This work was supported by NIH grants AI070207 and AI095449 (I.F.) and AI073301 (E.I.F.). The UAB CCC Bioanalytical and Mass Spectrometry Shared Facility is supported by NIH grant P30 CA013148 to the UAB Comprehensive Cancer Center. The UAB Center for AIDS Research Virology Core is supported by NIH grant P30 AI027767.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 11 December 2013

REFERENCES

- 1.Ramos HJ, Gale M., Jr 2011. RIG-I like receptors and their signaling crosstalk in the regulation of antiviral immunity. Curr. Opin. Virol. 1:167–176. 10.1016/j.coviro.2011.04.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Der SD, Yang YL, Weissmann C, Williams BR. 1997. A double-stranded RNA-activated protein kinase-dependent pathway mediating stress-induced apoptosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 94:3279–3283. 10.1073/pnas.94.7.3279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Der SD, Zhou A, Williams BR, Silverman RH. 1998. Identification of genes differentially regulated by interferon alpha, beta, or gamma using oligonucleotide arrays. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 95:15623–15628. 10.1073/pnas.95.26.15623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lenschow DJ, Giannakopoulos NV, Gunn LJ, Johnston C, O'Guin AK, Schmidt RE, Levine B, Virgin HW., IV 2005. Identification of interferon-stimulated gene 15 as an antiviral molecule during Sindbis virus infection in vivo. J. Virol. 79:13974–13983. 10.1128/JVI.79.22.13974-13983.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu SY, Sanchez DJ, Aliyari R, Lu S, Cheng G. 2012. Systematic identification of type I and type II interferon-induced antiviral factors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 109:4239–4244. 10.1073/pnas.1114981109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu SY, Sanchez DJ, Cheng G. 2011. New developments in the induction and antiviral effectors of type I interferon. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 23:57–64. 10.1016/j.coi.2010.11.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sadler AJ, Williams BR. 2008. Interferon-inducible antiviral effectors. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 8:559–568. 10.1038/nri2314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Silverman RH. 2007. Viral encounters with 2′,5′-oligoadenylate synthetase and RNase L during the interferon antiviral response. J. Virol. 81:12720–12729. 10.1128/JVI.01471-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Szretter KJ, Brien JD, Thackray LB, Virgin HW, Cresswell P, Diamond MS. 2011. The interferon-inducible gene viperin restricts West Nile virus pathogenesis. J. Virol. 85:11557–11566. 10.1128/JVI.05519-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thakur CS, Jha BK, Dong B, Das Gupta J, Silverman KM, Mao H, Sawai H, Nakamura AO, Banerjee AK, Gudkov A, Silverman RH. 2007. Small-molecule activators of RNase L with broad-spectrum antiviral activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104:9585–9590. 10.1073/pnas.0700590104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Atasheva S, Akhrymuk M, Frolova EI, Frolov I. 2012. New PARP gene with an anti-alphavirus function. J. Virol. 86:8147–8160. 10.1128/JVI.00733-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang Y, Burke CW, Ryman KD, Klimstra WB. 2007. Identification and characterization of interferon-induced proteins that inhibit alphavirus replication. J. Virol. 81:11246–11255. 10.1128/JVI.01282-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Atasheva S, Krendelchtchikova V, Liopo A, Frolova E, Frolov I. 2010. Interplay of acute and persistent infections caused by Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus encoding mutated capsid protein. J. Virol. 84:10004–10015. 10.1128/JVI.01151-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weaver SC, Ferro C, Barrera R, Boshell J, Navarro JC. 2004. Venezuelan equine encephalitis. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 49:141–174. 10.1146/annurev.ento.49.061802.123422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weaver SC, Frolov I. 2005. Togaviruses, p 1010–1024 In Mahy BWJ, ter Meulen V. (ed), Virology, vol 2 Hodder Arnold, Salisbury, United Kingdom [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schreiber V, Dantzer F, Ame JC, de Murcia G. 2006. Poly(ADP-ribose): novel functions for an old molecule. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 7:517–528. 10.1038/nrm1963 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kerns JA, Emerman M, Malik HS. 2008. Positive selection and increased antiviral activity associated with the PARP-containing isoform of human zinc-finger antiviral protein. PLoS Genet. 4:e21. 10.1371/journal.pgen.0040021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.MacDonald MR, Machlin ES, Albin OR, Levy DE. 2007. The zinc finger antiviral protein acts synergistically with an interferon-induced factor for maximal activity against alphaviruses. J. Virol. 81:13509–13518. 10.1128/JVI.00402-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bick MJ, Carroll JW, Gao G, Goff SP, Rice CM, MacDonald MR. 2003. Expression of the zinc-finger antiviral protein inhibits alphavirus replication. J. Virol. 77:11555–11562. 10.1128/JVI.77.21.11555-11562.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhu Y, Gao G. 2008. ZAP-mediated mRNA degradation. RNA Biol. 5:65–67. 10.4161/rna.5.2.6044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen S, Xu Y, Zhang K, Wang X, Sun J, Gao G, Liu Y. 2012. Structure of N-terminal domain of ZAP indicates how a zinc-finger protein recognizes complex RNA. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 19:430–435. 10.1038/nsmb.2243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhu Y, Chen G, Lv F, Wang X, Ji X, Xu Y, Sun J, Wu L, Zheng YT, Gao G. 2011. Zinc-finger antiviral protein inhibits HIV-1 infection by selectively targeting multiply spliced viral mRNAs for degradation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 108:15834–15839. 10.1073/pnas.1101676108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Volkova E, Gorchakov R, Frolov I. 2006. The efficient packaging of Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus-specific RNAs into viral particles is determined by nsP1-3 synthesis. Virology 344:315–327. 10.1016/j.virol.2005.09.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rice CM, Levis R, Strauss JH, Huang HV. 1987. Production of infectious RNA transcripts from Sindbis virus cDNA clones: mapping of lethal mutations, rescue of a temperature-sensitive marker, and in vitro mutagenesis to generate defined mutants. J. Virol. 61:3809–3819 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liljeström P, Lusa S, Huylebroeck D, Garoff H. 1991. In vitro mutagenesis of a full-length cDNA clone of Semliki Forest virus: the small 6,000-molecular-weight membrane protein modulates virus release. J. Virol. 65:4107–4113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gorchakov R, Frolova E, Williams BR, Rice CM, Frolov I. 2004. PKR-dependent and -independent mechanisms are involved in translational shutoff during Sindbis virus infection. J. Virol. 78:8455–8467. 10.1128/JVI.78.16.8455-8467.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lemm JA, Durbin RK, Stollar V, Rice CM. 1990. Mutations which alter the level or structure of nsP4 can affect the efficiency of Sindbis virus replication in a host-dependent manner. J. Virol. 64:3001–3011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Foy NJ, Akhrymuk M, Akhrymuk I, Atasheva S, Bopda-Waffo A, Frolov I, Frolova EI. 2013. Hypervariable domains of nsP3 proteins of New World and Old World alphaviruses mediate formation of distinct, virus-specific protein complexes. J. Virol. 87:1997–2010. 10.1128/JVI.02853-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gorchakov R, Garmashova N, Frolova E, Frolov I. 2008. Different types of nsP3-containing protein complexes in Sindbis virus-infected cells. J. Virol. 82:10088–10101. 10.1128/JVI.01011-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Johannes G, Sarnow P. 1998. Cap-independent polysomal association of natural mRNAs encoding c-myc, BiP, and eIF4G conferred by internal ribosome entry sites. RNA 4:1500–1513. 10.1017/S1355838298981080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Petrakova O, Volkova E, Gorchakov R, Paessler S, Kinney RM, Frolov I. 2005. Noncytopathic replication of Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus and eastern equine encephalitis virus replicons in mammalian cells. J. Virol. 79:7597–7608. 10.1128/JVI.79.12.7597-7608.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Frolov I, Schlesinger S. 1994. Comparison of the effects of Sindbis virus and Sindbis virus replicons on host cell protein synthesis and cytopathogenicity in BHK cells. J. Virol. 68:1721–1727 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Frolov I, Agapov E, Hoffman TA, Jr, Prágai BM, Lippa M, Schlesinger S, Rice CM. 1999. Selection of RNA replicons capable of persistent noncytopathic replication in mammalian cells. J. Virol. 73:3854–3865 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Frolov I, Schlesinger S. 1996. Translation of Sindbis virus mRNA: analysis of sequences downstream of the initiating AUG codon that enhance translation. J. Virol. 70:1182–1190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Volkova E, Frolova E, Darwin JR, Forrester NL, Weaver SC, Frolov I. 2008. IRES-dependent replication of Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus makes it highly attenuated and incapable of replicating in mosquito cells. Virology 377:160–169. 10.1016/j.virol.2008.04.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Garmashova N, Atasheva S, Kang W, Weaver SC, Frolova E, Frolov I. 2007. Analysis of Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus capsid protein function in the inhibition of cellular transcription. J. Virol. 81:13552–13565. 10.1128/JVI.01576-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Garmashova N, Gorchakov R, Volkova E, Paessler S, Frolova E, Frolov I. 2007. The Old World and New World alphaviruses use different virus-specific proteins for induction of transcriptional shutoff. J. Virol. 81:2472–2484. 10.1128/JVI.02073-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kleine H, Poreba E, Lesniewicz K, Hassa PO, Hottiger MO, Litchfield DW, Shilton BH, Luscher B. 2008. Substrate-assisted catalysis by PARP10 limits its activity to mono-ADP-ribosylation. Mol. Cell 32:57–69. 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.08.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Charron G, Li MM, MacDonald MR, Hang HC. 2013. Prenylome profiling reveals S-farnesylation is crucial for membrane targeting and antiviral activity of ZAP long-isoform. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 110:11085–11090. 10.1073/pnas.1302564110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Guo X, Carroll JW, Macdonald MR, Goff SP, Gao G. 2004. The zinc finger antiviral protein directly binds to specific viral mRNAs through the CCCH zinc finger motifs. J. Virol. 78:12781–12787. 10.1128/JVI.78.23.12781-12787.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Garmashova N, Gorchakov R, Frolova E, Frolov I. 2006. Sindbis virus nonstructural protein nsP2 is cytotoxic and inhibits cellular transcription. J. Virol. 80:5686–5696. 10.1128/JVI.02739-05 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kleine H, Herrmann A, Lamark T, Forst AH, Verheugd P, Luscher-Firzlaff J, Lippok B, Feijs KL, Herzog N, Kremmer E, Johansen T, Muller-Newen G, Luscher B. 2012. Dynamic subcellular localization of the mono-ADP-ribosyltransferase ARTD10 and interaction with the ubiquitin receptor p62. Cell Commun. Signal 10:28. 10.1186/1478-811X-10-28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bouloy M, Janzen C, Vialat P, Khun H, Pavlovic J, Huerre M, Haller O. 2001. Genetic evidence for an interferon-antagonistic function of Rift Valley fever virus nonstructural protein NSs. J. Virol. 75:1371–1377. 10.1128/JVI.75.3.1371-1377.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liu WJ, Chen HB, Wang XJ, Huang H, Khromykh AA. 2004. Analysis of adaptive mutations in Kunjin virus replicon RNA reveals a novel role for the flavivirus nonstructural protein NS2A in inhibition of beta interferon promoter-driven transcription. J. Virol. 78:12225–12235. 10.1128/JVI.78.22.12225-12235.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang X, Li M, Zheng H, Muster T, Palese P, Beg AA, Garcia-Sastre A. 2000. Influenza A virus NS1 protein prevents activation of NF-kappaB and induction of alpha/beta interferon. J. Virol. 74:11566–11573. 10.1128/JVI.74.24.11566-11573.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ruggli N, Tratschin JD, Schweizer M, McCullough KC, Hofmann MA, Summerfield A. 2003. Classical swine fever virus interferes with cellular antiviral defense: evidence for a novel function of N(pro). J. Virol. 77:7645–7654. 10.1128/JVI.77.13.7645-7654.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Munoz-Jordan JL, Sanchez-Burgos GG, Laurent-Rolle M, Garcia-Sastre A. 2003. Inhibition of interferon signaling by dengue virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100:14333–14338. 10.1073/pnas.2335168100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jennings S, Martinez-Sobrido L, Garcia-Sastre A, Weber F, Kochs G. 2005. Thogoto virus ML protein suppresses IRF3 function. Virology 331:63–72. 10.1016/j.virol.2004.10.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Billecocq A, Spiegel M, Vialat P, Kohl A, Weber F, Bouloy M, Haller O. 2004. NSs protein of Rift Valley fever virus blocks interferon production by inhibiting host gene transcription. J. Virol. 78:9798–9806. 10.1128/JVI.78.18.9798-9806.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Basler CF, Wang X, Muhlberger E, Volchkov V, Paragas J, Klenk HD, Garcia-Sastre A, Palese P. 2000. The Ebola virus VP35 protein functions as a type I IFN antagonist. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97:12289–12294. 10.1073/pnas.220398297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Basler CF, Mikulasova A, Martinez-Sobrido L, Paragas J, Muhlberger E, Bray M, Klenk HD, Palese P, Garcia-Sastre A. 2003. The Ebola virus VP35 protein inhibits activation of interferon regulatory factor 3. J. Virol. 77:7945–7956. 10.1128/JVI.77.14.7945-7956.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Frolov I, Akhrymuk M, Akhrymuk I, Atasheva S, Frolova EI. 2012. Early events in alphavirus replication determine the outcome of infection. J. Virol. 86:5055–5066. 10.1128/JVI.07223-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gale M, Jr, Katze MG. 1998. Molecular mechanisms of interferon resistance mediated by viral-directed inhibition of PKR, the interferon-induced protein kinase. Pharmacol. Ther. 78:29–46. 10.1016/S0163-7258(97)00165-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schreiber V, Ame JC, Dolle P, Schultz I, Rinaldi B, Fraulob V, Menissier-de Murcia J, de Murcia G. 2002. Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-2 (PARP-2) is required for efficient base excision DNA repair in association with PARP-1 and XRCC1. J. Biol. Chem. 277:23028–23036. 10.1074/jbc.M202390200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Poirier GG, de Murcia G, Jongstra-Bilen J, Niedergang C, Mandel P. 1982. Poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation of polynucleosomes causes relaxation of chromatin structure. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 79:3423–3427. 10.1073/pnas.79.11.3423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Virag L, Robaszkiewicz A, Vargas JM, Javier Oliver F. 2013. Poly(ADP-ribose) signaling in cell death. Mol. Aspects Med. 34:1153–1167. 10.1016/j.mam.2013.01.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rosado MM, Bennici E, Novelli F, Pioli C. 2013. Beyond DNA repair, the immunological role of PARP-1 and its siblings. Immunology 139:428–437. 10.1111/imm.12099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cherry S, Doukas T, Armknecht S, Whelan S, Wang H, Sarnow P, Perrimon N. 2005. Genome-wide RNAi screen reveals a specific sensitivity of IRES-containing RNA viruses to host translation inhibition. Genes Dev. 19:445–452. 10.1101/gad.1267905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]