Abstract

Besides an essential transcriptional factor for B cell development and function, cellular interferon regulatory factor 4 (c-IRF4) directly regulates expression of the c-Myc gene, which is not only associated with various B cell lymphomas but also required for herpesvirus latency and pathogenesis. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV), the etiological agent of Kaposi's sarcoma and primary effusion lymphoma, has developed a unique mechanism to deregulate host antiviral innate immunity and growth control by incorporating four viral homologs (vIRF1 to -4) of cellular IRFs into its genome. Previous studies have shown that several KSHV latent proteins, including vIRF3, vFLIP, and LANA, target the expression, function, and stability of c-Myc to establish and maintain viral latency. Here we report that the KSHV vIRF4 lytic protein robustly suppresses expression of c-IRF4 and c-Myc, reshaping host gene expression profiles to facilitate viral lytic replication. Genomewide gene expression analysis revealed that KSHV vIRF4 grossly affects host gene expression by upregulating and downregulating 118 genes and 166 genes, respectively, by at least 2-fold. Remarkably, vIRF4 suppressed c-Myc expression by 11-fold, which was directed primarily by the deregulation of c-IRF4 expression. Real-time quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR), single-molecule in situ hybridization, and chromatin immunoprecipitation assays showed that vIRF4 not only reduces c-IRF4 expression but also competes with c-IRF4 for binding to the specific promoter region of the c-Myc gene, resulting in drastic suppression of c-Myc expression. Consequently, the loss of vIRF4 function in the suppression of c-IRF4 and c-Myc expression ultimately led to a reduction of KSHV lytic replication capacity. These results indicate that the KSHV vIRF4 lytic protein comprehensively targets the expression and function of c-IRF4 to downregulate c-Myc expression, generating a favorable environment for viral lytic replication. Finally, this study further reinforces the important role of the c-Myc gene in KSHV lytic replication and latency.

INTRODUCTION

Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV), or human herpesvirus 8, is a lymphotropic γ2-herpesvirus that is the etiologic agent of Kaposi's sarcoma (KS) and two lymphoproliferative disorders: primary effusion lymphomas (PELs) (1) and multicentric Castleman's diseases (MCDs) (2). KS and PEL cells are predominantly infected with the latent form of KSHV, expressing only a few latent genes (1, 3) whose proteins subvert various cellular pathways in order to increase the proliferation and survival of virus-infected tumor cells. Thus, understanding the KSHV-mediated regulation of host gene expression for its life cycle is the crux of this study.

The proto-oncogene c-Myc is a basic helix-loop-helix-leucine zipper transcriptional factor that regulates expression of more than 15% of all host genes, ultimately controlling proliferation, differentiation, and death. In particular, c-Myc expression is frequently deregulated in a large proportion of aggressive lymphomas, due to chromosomal translocation (e.g., Burkitt's lymphoma), gene amplification (e.g., non-Hodgkin lymphomas), or abnormal stabilization (4–7). Interestingly, to maintain herpesvirus latency and oncogenesis, c-Myc protein is frequently stabilized and functionally activated in PELs by the KSHV-encoded latency-associated nuclear antigen (LANA) and viral interferon regulatory factor 3 (vIRF3), respectively (8–11). Thus, c-Myc is a key cellular factor coupling KSHV latency with growth transformation.

The cellular interferon regulatory factor (c-IRF) family of transcription factors, which are characterized by a unique tryptophan pentad repeat DNA-binding domain (DBD), is important in the regulation of interferons (IFNs) and IFN-inducible genes in response to viral infections. Among this family's members, c-IRF4 is a lymphoid tissue-specific transcription factor that plays crucial roles in the development and functions of immune cells: it controls B-cell proliferation and differentiation and proliferation of mitogen-activated T cells. In addition, c-IRF4 binds to the IFN-stimulated response element (ISRE) of the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I promoter and the immunoglobulin lambda light chain enhancer together with PU.1, and it positively regulates the biosynthetic processes of interleukin-2 (IL-2), IL-4, IL-10, and IL-13. On the other hand, c-IRF4 negatively regulates Toll-like receptor signaling by competing with c-IRF5, and it inhibits proinflammatory cytokine production. Emerging evidence has indicated that c-IRF4 is also a pivotal factor that directly targets c-Myc gene expression, generating an autoregulatory feedback loop for cell growth in myeloma cells, as well as acting as a tumor suppressor in early B-cell development (12, 13). Notably, several studies have shown that c-IRF4 activation is critical for the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-mediated transformation of B lymphocytes (14, 15). On the other hand, it also acts as a negative regulator of KSHV replication and transcription activator (RTA) expression upon induction of KSHV lytic reactivation (16). Taken together, the data indicate that c-IRF4 plays multiple roles in the regulation of host and viral gene expression.

The KSHV genome carries at least 90 genes that are expressed during the latent and lytic phases of the viral life cycle. While KSHV shares the majority of its genes with other herpesviruses, KSHV also carries unique genes that are homologues of cellular genes involved in immune modulation, cell death, growth, and differentiation. These viral homologues play critical roles in subverting host antiviral immune responses (17). In particular, four viral interferon regulatory factors (vIRFs) bear significant homology with c-IRFs and counteract IFN- and tumor suppressor-mediated innate antiviral defenses by either subverting IFN production or deregulating p53 tumor suppressor function (17, 18). Specifically, vIRF4 has been shown to antagonize p53-mediated tumor suppressor activity by regulating two crucial components of the p53 pathway: the human double minute 2 (HDM2; also called MDM2) E3 ubiquitin ligase and the herpesvirus-associated ubiquitin-specific protease (HAUSP; also known as USP7) deubiquitylating enzyme (19, 20). In addition, vIRF4 was found to interact with CSL (RBP-Jκ), a cellular transcriptional factor that acts as a critical coregulator of RTA, a master regulator of KSHV reactivation (21). While the biological consequences are still not clear, vIRF4 has been shown to compete with the Notch receptor for CSL binding to modulate Notch signaling (21). vIRF4 also interacts with the poly(A)-binding protein, potentially interfering with host translation (22). Finally, vIRF4 was recently found to be a positive regulator of RTA function itself (23). These observations indicate that vIRF4 potentially functions as a regulator by cooperation with either host or viral proteins to promote an efficient KSHV life cycle.

To further delineate the role of vIRF4 in host-virus interaction, we examined the potential effects of vIRF4 on host gene expression in KSHV-infected PELs. This study reveals that the KSHV vIRF4 lytic protein specifically targets c-IRF4 expression and function to downregulate c-Myc expression, generating a favorable environment for viral lytic replication. Real-time quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR), single-molecule in situ hybridization, and chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays showed that KSHV vIRF4 targets c-IRF4 in two independent ways: it suppresses c-IRF4 expression and competes with c-IRF4 for binding to the specific promoter region of the c-Myc gene, resulting in a drastic suppression of c-Myc gene expression. By utilizing recombinant KSHV, we also show that the loss of vIRF4 function in the downregulation of c-IRF4 and c-Myc expression leads to a reduction of KSHV lytic replication. These results indicate that the KSHV vIRF4 lytic protein is a critical factor that robustly suppresses c-IRF4 and c-Myc expression, generating a favorable environment for viral lytic replication.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture and transfection reagents.

Tetracycline-inducible TRExBCBL-1 and TRExBJAB cells (24) and H929 cells were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (P/S) (Gibco-BRL). 293T and TREx293T cells (24) were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% P/S (Gibco-BRL). The iSLK cell line was a generous gift from Jinjong Myung (UCSF, San Francisco, CA) (25). iSLKBAC16, iSLK-vIRF4ΔDBDBAC16, and iSLKR-vIRF4ΔDBDBAC16 cell lines were grown in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 1% P/S, 1 μg/ml puromycin, 250 μg/ml G418, and 1.2 mg/ml hygromycin B. Transient transfections were performed with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) and Effectin (Qiagen) according to the manufacturers' instructions.

Plasmid construction.

All constructs for transient and stable expression in mammalian cells were derived from the pcDNA5/FRT/To-Hygro and pcDH-CMV-Puro expression vectors. DNA fragments corresponding to the coding sequences of the wild-type (WT) vIRF4 gene were amplified from template DNA (kindly provided by Jürgen Hass) by PCR and then subcloned into pcDNA5/FRT/To-Hygro at the BamHI and NotI restriction sites and into pcDH-CMV-Puro at the EcoRI and BamHI restriction sites. C-terminally Flag-tagged c-IRF4 was expressed from a modified pcDH-CMV-Puro vector. The vIRF4ΔDBD mutant was generated via PCR. All constructs were sequenced using an ABI Prism 377 automatic DNA sequencer to verify 100% correspondence with the original sequence.

Cell line construction.

To establish KSHV-infected BCBL-1 cells expressing WT or mutant vIRF4 in a tetracycline-inducible manner, pcDNA/FRT/To-vIRF4/Au or pcDNA/FRT/To-vIRF4ΔDBD/Au was transfected via electroporation along with the pOG44 Flp recombinase expression vector. Twenty-four hours after electroporation, cells were selected using 200 μg/ml of hygromycin B (Invitrogen) for 3 weeks. The detailed procedure has been described previously (20). BAC16, vIRF4ΔDBD-BAC16, or R-vIRF4ΔDBD-BAC16 DNA was transfected via Lipofectamine along with Effectin into iSLK cells. Twenty-four hours after transfection, cells were selected using 1 μg/ml puromycin, 250 μg/ml G418, and 1.2 mg/ml hygromycin B.

Chemicals and antibodies.

Selected cells were treated with 1 μg/ml of doxycycline (Doxy) (Sigma) or 1 mM sodium butyrate (NaB) (Sigma) for the indicated periods. Primary antibodies were purchased from the following sources: IRF4 (D43H10) and β-catenin antibodies from Cell Signaling, c-Myc (N-262) antibody from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, tubulin antibody from Sigma, Au antibody from Covance, histone H3 (ab1791) antibody from Abcam, and viral IL-6 (vIL-6) antibody from Advanced Biotechnologies. K8.1, LANA, and K5 antibodies have been described previously (24). RTA rabbit polyclonal antibody was a generous gift from Yoshihiro Izumiya and Hsing-Jien Kung (University of California, Davis, Sacramento, CA). Polyclonal anti-vIRF4 antibody was generated against the region of vIRF4 encompassing amino acids 235 to 490.

RNA isolation and RT-qPCR.

Total RNAs were extracted using Tri reagent (Sigma) and then reverse transcribed using an iScript cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad). The resultant cDNAs were measured by either conventional PCR or qPCR. Real-time PCR was performed using Sybr Green-based detection methods in a CFX96 real-time system (Bio-Rad) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The 18S rRNA gene was used as a normalization control. RT-PCR graphs were made based on the averages for at least two independent experiments.

Microarray analysis.

Total RNAs were isolated using Tri reagent (Sigma), and microarray analysis was performed using GeneChip Human Gene 2.0 ST arrays. Data were normalized between groups with Affymetrix Expression Console software, and the Benjamini and Hochberg algorithm was used to control the false discovery rate (FDR) of duplicate testing (FDR-adjusted P value of <0.01, selected for genes showing a >2-fold change; Parteck Genomic Suite, Partek Incorporated). Heat maps for gene expression were created using Spotfire DecisionSite 9.1.1.

ChIP assays.

Detailed descriptions of the ChIP assays have been published previously (26). Briefly, chromatin containing 10 μg of DNA was treated with 1 to 2 μg of antibodies overnight at 4°C for immunoprecipitation. On the next day, to pull down the DNA-protein complexes, protein A/G agarose was added for 4 h. Immunoprecipitation complexes were washed sequentially with RIPA buffer, LiCl buffer, and, finally, Tris-EDTA (TE) buffer. The DNA-protein-protein A/G agarose complex was resuspended in 100 μl of TE buffer containing 50 μg/μl RNase A and incubated for 30 min at 37°C. Proteinase K treatment, cross-link reversal, and DNA purification were done to prepare input DNA. Both input and ChIP DNAs were measured by qPCR. Based on the standard curve for each primer pair, the enrichment of proteins and histone modifications on specific genomic regions was calculated as the percentage of immunoprecipitated DNA compared to input DNA. Each data point in the ChIP figures is the average for at least three independent ChIP assays using three independent chromatin samples.

Lentivirus transduction.

Gene expression constructs were prepared using the pcDH lentiviral vector. Supernatants from 293T cells transfected with either pcDH-vIRF4-Au or pcDH-IRF4-Flag together with packaging vectors were collected at 72 h posttransfection, followed by concentration of the viruses (2,400 rpm, 3 h, 4°C). One million TREx293, H929, or TRExBCBL-1 cells were used for spinning infections (1,800 rpm, 45 min, 30°C) in the presence of 10 μg/ml Polybrene. At 5 days postinfection, cells were harvested for immunoblotting and RT-qPCR analysis.

Construction of vIRF4 DNA-binding domain-deficient KSHV (BAC16-vIRF4ΔDBD virus).

The vIRF4 DBD-deficient KSHV strain was generated by deleting the coding sequence of vIRF4 exon 1, resulting in vIRF4ΔDBD. Mutagenesis was performed in the Escherichia coli GS1783 strain by using “scarless” mutagenesis, as previously described (27). The vIRF4ΔDBD mutant was generated by amplifying a Kanr I-SceI cassette from the pEP-Kan-S plasmid, using the following primers: forward primer, CAAACCTCACACCCCCTTCCCCGAGTTACATACCTAGTGTCACTCATGGTCCGACACAGAAACCGATCaggatgacgataagtaggg; and reverse primer, TGTGCCTCAAAGACGAACGCCGATCGGTTTCTGTGTCGGACCATGAGTGACACTAGGTATGTAACTCaaccaattctgattag. Uppercase letters in primer sequences indicate the KSHV genomic sequences that were used for homologous recombination, whereas the sequences given in lowercase letters were used to PCR amplify the Kanr I-SceI cassette from the pEP-Kan-S plasmid. NheI and AseI restriction enzyme digestions of bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) DNAs, followed by either conventional agarose gel electrophoresis or pulsed-field gel electrophoresis, were used to verify specific mutations without genetic rearrangements of the vIRF4ΔDBDBAC16 mutant compared to WTBAC16 and revertant vIRF4ΔDBDBAC16.

smFISH.

Single-molecule fluorescence in situ hybridization (smFISH) experiments were performed according to the protocol of Raj et al. (28). TRExBCBL-1 pcDNA and TRExBCBL-1 vIRF4/Au cells were treated with Doxy (1 μg/ml) for 24 h and sequentially fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde. After fixation, chambers were kept in 70% ethanol (EtOH) at −20°C for at least overnight to permeabilize and store the cells until use. Cells were then rehydrated in a solution of 10% formamide and 2× SSC ((1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate) for 5 min before hybridization. Hybridization reactions were carried out overnight at 37°C in 100 μl of hybridization buffer containing 10% dextran sulfate, 2 mM vanadyl-ribonucleoside complex, 0.02% RNase-free bovine serum albumin (BSA), 50 μg E. coli tRNA, 2× SSC, 10% formamide, and FISH probes targeting c-Myc, c-IRF4, and vIRF4, labeled with Cy3, Alexa Fluor 594, and Cy5, respectively. After hybridization, the cells were washed twice for 30 min at 37°C, using a wash buffer containing 10% formamide and 2× SSC. An oxygen-scavenging mounting medium containing 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 2× SSC, 1% glucose, glucose oxidase, and catalase was used during imaging. Images were acquired with a Zeiss Axiovert 200M inverted fluorescence microscope with an Apotome Structured Illumination optical sectioning system, equipped with a 100× 1.46-numerical-aperture (NA) oil-immersion objective and a Cascade 512b EMCCD camera. Thirty z stacks were taken automatically, with 0.3 μm between the z slices and an exposure time of 0.5 s. To quantify the number of spots, each of which corresponds to a single mRNA, we used the method and MATLAB code described and provided by Raj et al. (28).

Microarray data accession number.

Microarray data are available at the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database under accession number PRJNA214053.

RESULTS

vIRF4 robustly downregulates c-Myc gene expression.

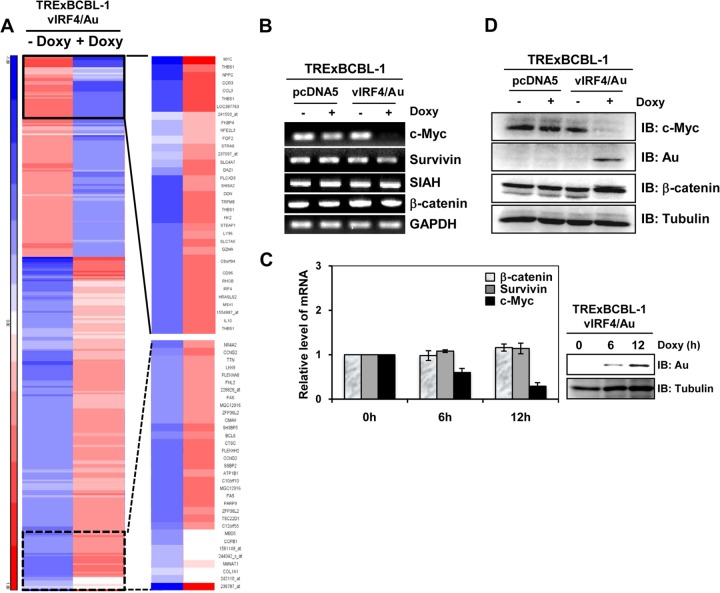

KSHV-infected BCBL-1 cells ectopically expressing carboxyl-terminal Au-tagged vIRF4 in a tetracycline-inducible manner (20) were utilized to study the effect of vIRF4 on host gene expression. TRExBCBL-1 pcDNA5 and TRExBCBL-1 vIRF4/Au cells were incubated with or without Doxy for 24 h, and their mRNAs were subjected to Affymetrix expression microarray analysis. This analysis showed that vIRF4 expression grossly affected host gene expression by upregulating 118 cellular genes and downregulating 166 genes at least 2-fold. The gene expression clusters of the 280 differentially regulated genes are depicted in Fig. 1A and in Table S1 in the supplemental material. We also used the Ingenuity pathway analysis platform to analyze the networking and biological functions of those genes that were affected by vIRF4. This showed that vIRF4 expression primarily affected the expression profiles of genes involved in the apoptosis pathway and the cell cycle regulation pathway (see Table S2 in the supplemental material).

FIG 1.

vIRF4 robustly downregulates c-Myc gene expression in KSHV-infected PEL cells. (A) Genomewide analysis of vIRF4 effects on host gene expression. The heat map represents expression profiles of cellular mRNAs upon vIRF4 expression and represents averages for two independent experiments. The values were normalized, clustered on the basis of a Euclidean metric, and represented on a log2 scale. (B) Validation of microarray data by RT-PCR. The blots show the results of RT-PCR assays of c-Myc, Survivin, SIAH, β-catenin, and GAPDH expression in TRExBCBL-1 pcDNA or TRExBCBL-1 vIRF4/Au cells upon Doxy (1 μg/ml) treatment. (C) vIRF4-mediated suppression of c-Myc expression in a time-dependent manner. TRExBCBL-1 vIRF4/Au cells were treated with Doxy (1 μg/ml) for the indicated times, and the c-Myc, Survivn, and β-catenin mRNA levels were analyzed by RT-qPCR. (D) c-Myc expression in Doxy-induced TRExBCBL-1 vIRF4/Au cells. Upon Doxy (1 μg/ml) stimulation, equal amounts of total proteins were analyzed by immunoblotting (IB) with an anti-Myc antibody or anti-β-catenin antibody. Anti-tubulin and anti-Au antibodies were used to monitor protein amounts and vIRF4 expression, respectively.

Microarray analysis showed that c-Myc was remarkably downregulated (11-fold) upon vIRF4 expression (Fig. 1A). To confirm this result, TRExBCBL-1 pcDNA and TRExBCBL-1 vIRF4/Au cells were incubated with or without Doxy for 24 h, followed by RT-PCR analysis with human c-Myc-specific primers. Since the c-Myc gene is a target of β-catenin-mediated activation of TCF-dependent transcriptional factors, we also included primers specific for the Survivin, SIAH, and β-catenin genes and the GAPDH (glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase) gene, as a loading control. This showed that vIRF4 expression dramatically downregulated the c-Myc mRNA level, but not the Survivin, SIAH, or β-catenin mRNA level, in a time-dependent manner (Fig. 1B and C). These results were further confirmed by immunoblot analysis with specific antibodies. Endogenous c-Myc dramatically decreased in TRExBCBL-1 vIRF4/Au cells compared to that in TRExBCBL-1 pcDNA cells (Fig. 1D). In contrast, vIRF4 expression showed little or no change in tubulin and β-catenin protein levels under the same conditions, while a slow-migrating β-catenin protein was detected upon vIRF4 expression (Fig. 1D). Collectively, these results indicate that vIRF4 expression hugely affects the expression profiles of host genes, among which c-Myc expression is most affected.

vIRF4 downregulates c-Myc gene expression in a c-IRF4-dependent manner.

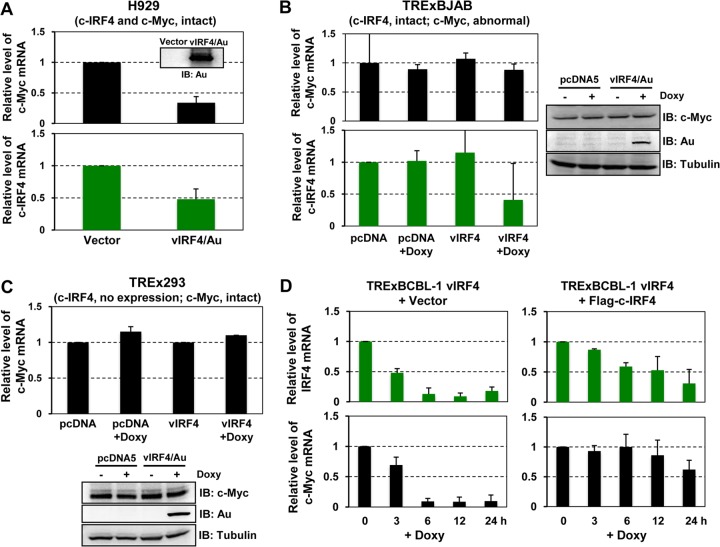

c-IRF4 expression is restricted to the lymphoid and myeloid lineages and is frequently deregulated in lymphoma cells (13, 29). Additionally, a recent study showed that c-IRF4 is critical for the induction of c-Myc expression in multiple myeloma cells, playing a crucial role for their survival and expansion (13). Microarray analysis showed that c-IRF4 was also downregulated 3-fold upon vIRF4 expression. Given that c-IRF4 directly regulates c-Myc gene expression (13), we postulated that vIRF4 suppressed c-IRF4 expression, leading to the reduction of c-Myc expression. To investigate this, we utilized three different cell lines that harbor different c-Myc and c-IRF4 expression levels and promoter structures. First, H929 cells, which carry the authentic forms of the c-Myc and c-IRF4 genes (30), were transduced with a lentivirus carrying vIRF4 or GFP for 48 h and then subjected to RT-qPCR. Consistent with the microarray analysis data (Fig. 1A), we were able to observe the vIRF4-mediated downregulation of c-Myc and c-IRF4 gene expression (Fig. 2A). Next, we used BJAB Burkitt's lymphoma cells, in which the c-IRF4 gene is intact but the c-Myc gene is translocated to the IgG promoter region (31). TRExBJAB cells expressing vector (pcDNA) or vIRF4 in a tetracycline-inducible manner were treated with or without Doxy and then subjected to RT-qPCR and immunoblot analyses (Fig. 2B). These analyses showed that while vIRF4 expression led to a significant reduction of the c-IRF4 mRNAs, it showed little or no effect on the c-Myc mRNA and protein levels (Fig. 2B, left panel). Third, when 293 cells, which carry an intact c-Myc gene but do not express c-IRF4 expression, were used, tetracycline-inducible vIRF4 expression led to no reduction of the c-Myc mRNAs (Fig. 2C). Finally, the c-Myc and c-IRF4 expression kinetics were compared in TRExBCBL-1 vIRF4/Au cells versus TRExBCBL-1 vIRF4/Au&Flag-c-IRF4 cells, carrying cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter-mediated expression of the Flag-tagged c-IRF4 gene. These cells were harvested at various time points of Doxy treatment and used for RT-qPCR analysis. This showed that Doxy-induced vIRF4 expression in TRExBCBL-1 vIRF4/Au cells led to a rapid decrease of c-IRF4 mRNAs along with a marked reduction of c-Myc mRNAs (Fig. 2D, left panel). In contrast, Doxy-induced vIRF4 expression in TRExBCBL-1 vIRF4/Au&Flag-c-IRF4 cells showed a weak reduction of c-IRF4 mRNAs, with delayed kinetics, but little or no reduction of c-Myc mRNAs (Fig. 2D, right panel), indicating that ectopic expression of the c-IRF4 gene blocks the vIRF4-mediated suppression of c-Myc expression (Fig. 2D, right panel). These results collectively indicate that vIRF4 suppresses c-Myc expression in a c-IRF4-dependent manner.

FIG 2.

vIRF4 downregulates c-Myc gene expression in a c-IRF4-dependent manner. (A) Effect of vIRF4 on expression of c-Myc and c-IRF4 in H929 cells. H929 cells were transduced by a lentivirus carrying either GFP (control) or vIRF4/Au. At 3 days postinfection, cell lysates were used for either IB with anti-Au antibody or RT-qPCR analyses with c-Myc-, c-IRF4-, and 18S specific primers. (B and C) Effects of vIRF4 on expression of c-Myc and c-IRF4 in BJAB (B) and 293T (C) cells. Twenty-four hours after treatment of TRExBJAB pcDNA and TRExBJAB vIRF4/Au cells (B) or TREx293T pcDNA and TREx293T vIRF4/Au cells (C) with Doxy, equal amounts of cell lysates were used for RT-qPCR and IB, as indicated. (D) c-Myc and c-IRF4 expression kinetics upon vIRF4 expression. (Left) TRExBCBL-1 vIRF4/Au cells were induced with Doxy treatment for the indicated times, and equal amounts of total RNAs were analyzed by RT-qPCR. (Right) TRExBCBL-1 vIRF4/Au cells were transduced by a lentivirus carrying c-IRF4/Flag and incubated for 48 h, followed by Doxy stimulation. Cells were harvested at the indicated times and used for RT-qPCR analysis.

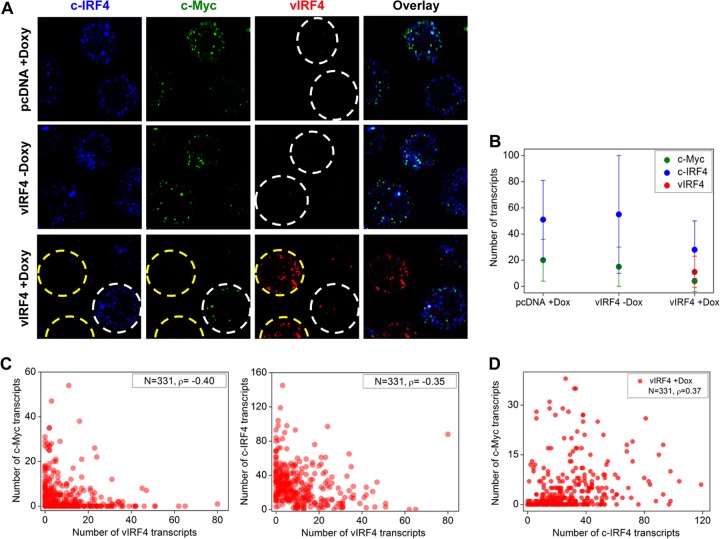

vIRF4-mediated reduction of c-IRF4 and c-Myc mRNAs at single-cell level.

We used the smFISH technique to quantify mRNA levels of the c-Myc, c-IRF4, and vIRF4 genes at the single-cell level (28). TRExBCBL-1 pcDNA cells (Doxy-treated conditions) contained, on average, ∼51 and ∼22 copies of the c-IRF4 and c-Myc mRNAs per cell, respectively, and TRExBCBL-1 vIRF4/Au cells (Doxy-untreated conditions) contained, on average, ∼54 and ∼18 copies of the c-IRF4 and c-Myc mRNAs per cell, respectively (Fig. 3A and B). In striking contrast, Doxy-induced vIRF4 expression (average of ∼11 mRNA copies per cell) led to a marked reduction of c-IRF4 and c-Myc mRNAs: on average, there were ∼28 and ∼4 copies of the c-IRF4 and c-Myc mRNAs per cell, respectively (Fig. 3A, yellow circles, and B). The smFISH experiments also revealed the heterogeneity of vIRF4 expression: upon Doxy treatment, a few TRExBCBL-1 vIRF4/Au cells showed nearly no vIRF4 expression, which led to no detectable reductions of the c-IRF4 and c-Myc mRNAs (Fig. 3A, white circles). By analyses of single cells, we obtained negative Spearman's correlation coefficients for the c-Myc and vIRF4 transcripts (ρ = −0.40) and for the c-IRF4 and vIRF4 transcripts (ρ = −0.35), showing that vIRF4 expression suppresses c-IRF4 and c-Myc transcription at the single-cell level (Fig. 3C and D). In contrast, the c-Myc and c-IRF4 transcripts were positively correlated with each other in TRExBCBL-1 vIRF4 cells (Doxy-treated conditions) (ρ = 0.37) (Fig. 3D). Overall, these results show that increased vIRF4 expression results in decreased c-IRF4 and c-Myc expression in individual cells, further supporting the hypothesis of vIRF4-mediated suppression of c-IRF4 and c-Myc expression.

FIG 3.

vIRF4-mediated reduction of c-IRF4 and c-Myc mRNAs at the single-cell level. (A) c-Myc, c-IRF4, and vIRF4 mRNAs were individually codetected in TRExBCBL-1 pcDNA and TRExBCBL-1 vIRF4/Au cells with or without Doxy treatment. Cell boundaries are indicated by dashed lines. (B) Average numbers of c-Myc, c-IRF4, and vIRF4 transcripts (± standard deviations [SD]) in TRExBCBL-1 pcDNA and TRExBCBL-1 vIRF4/Au cells with or without Doxy treatment. (C) Scatter plots of numbers of c-Myc versus vIRF4 and c-IRF4 versus vIRF4 transcripts in individual TRExBCBL-1 vIRF4 cells upon Doxy treatment (N, sample size; ρ, Spearman's correlation coefficient). (D) Pairwise Spearman's correlation coefficients for c-Myc versus c-IRF4 in TRExBCBL-1 pcDNA and TRExBCBL-1 vIRF4/Au cells with or without Doxy treatment.

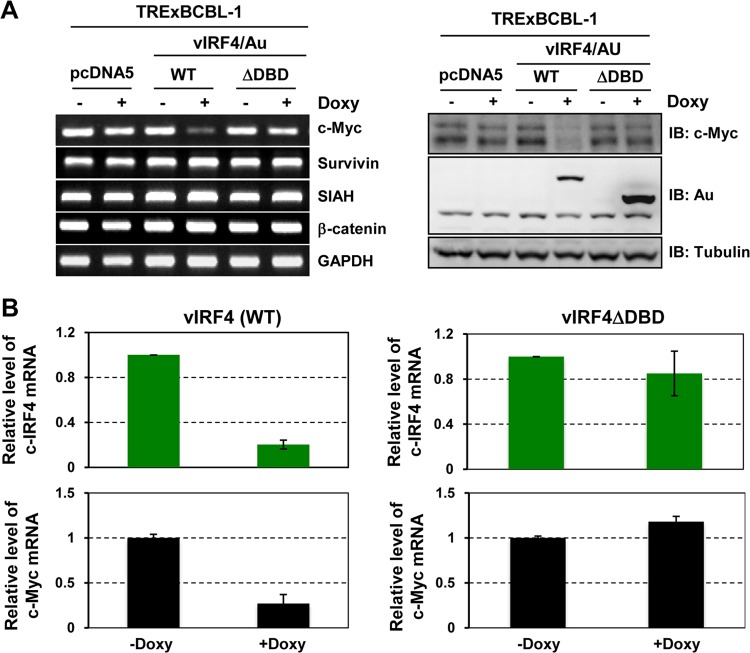

vIRF4 DBD is necessary to suppress c-Myc gene expression.

To date, 9 IRF genes have been identified in the human genome and each IRF has a well-conserved N-terminal DBD containing a tryptophan pentad repeat and a central IRF association domain (IAD) (18). In line with this, vIRF4 also contains a potential DBD within its N-terminal region. To test whether the vIRF4 DBD plays roles in the suppression of c-IRF4 and c-Myc expression, we constructed TRExBCBL-1 cells expressing a vIRF4 mutant (vIRF4ΔDBD) lacking the N-terminal 151 residues. TRExBCBL-1 pcDNA, TRExBCBL-1 vIRF4/Au, and TRExBCBL-1 vIRF4ΔDBD/Au cells were treated with or without Doxy for 24 h, and levels of the c-Myc, Survivin, SIAH, β-catenin, and GAPDH mRNAs were then examined by RT-PCRs using specific primers. This showed that unlike the WT, the vIRF4ΔDBD mutant was not capable of suppressing c-Myc expression (Fig. 4A, right panel). Immunoblotting also showed that WT vIRF4 led to a marked reduction of endogenous c-Myc expression, whereas the vIRF4ΔDBD mutant did not (Fig. 4A, left panel). Furthermore, RT-qPCR analysis confirmed that WT vIRF4 expression led to a marked reduction of the c-IRF4 and c-Myc mRNAs, whereas vIRF4ΔDBD mutant expression did not (Fig. 4B). These results suggest that the DBD of vIRF4 is necessary for its activity to suppress c-IRF4 and c-Myc expression.

FIG 4.

vIRF4 DNA-binding domain is necessary to suppress c-Myc gene expression. (A) vIRF4ΔDBD mutant fails to suppress c-Myc expression. Twenty-four hours after treatment with Doxy (1 μg/ml), TRExBCBL-1 pcDNA, TRExBCBL-1 vIRF4/Au, and TRExBCBL-1 vIRF4ΔDBD/Au cell lysates were used for RT-qPCR (left) and IB (right). (B) vIRF4ΔDBD mutant fails to suppress c-IRF4 expression. TRExBCBL-1 vIRF4/Au and TRExBCBL-1 vIRF4ΔDBD/Au cells were stimulated with Doxy (1 μg/ml) for 24 h and then used for RT-qPCR analysis.

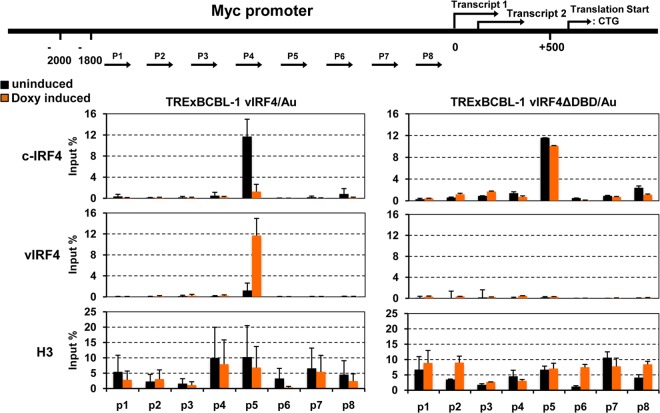

vIRF4 competes with c-IRF4 by binding to the same c-Myc promoter region.

To reveal the underlying mechanism of the vIRF4-mediated suppression of c-Myc expression, TRExBCBL-1 vIRF4/Au and TRExBCBL-1 vIRF4ΔDBD/Au cells were treated with or without 1 μg/ml of Doxy for 24 h and then subjected to a ChIP assay with anti-Au, anti-c-IRF4, or anti-histone 3 (H3) antibody, followed by elution of the immunoprecipitated chromatins. Subsequently, the ChIP DNAs were measured by qPCRs using specific primers corresponding to the promoter (P1 to P8) regions of the c-Myc gene (Fig. 5, top diagram). This showed that c-IRF4 was enriched on the P5 promoter region of the c-Myc gene, but its occupancy of the P5 promoter was dramatically reduced upon vIRF4 expression (Fig. 5, left panels). Remarkably, similar to c-IRF4, vIRF4 was also enriched on the P5 region of the c-Myc promoter (Fig. 5, left panels). In striking contrast, the vIRF4ΔDBD mutant did not bind to the P5 region of the c-Myc promoter, resulting in no effect on c-IRF4 enrichment on the P5 region of the c-Myc promoter (Fig. 5, right panels). ChIP and qPCR with anti-H3 antibody were included as controls (Fig. 5, bottom panels). These data collectively indicate that since both c-IRF4 and vIRF4 appear to bind to the same region of the c-Myc promoter, vIRF4 competes with c-IRF4 for binding to the c-Myc promoter.

FIG 5.

vIRF4 competes with c-IRF4 for binding to the c-Myc promoter region. TRExBCBL-1 vIRF4/Au and TRExBCBL-1 vIRF4ΔDBD/Au cells were mock treated or treated with Doxy for 24 h. Au, c-IRF4, and histone 3 (H3) antibodies were used for ChIP assay, and ChIP DNAs were subjected to RT-qPCRs using primers for the c-Myc promoter regions.

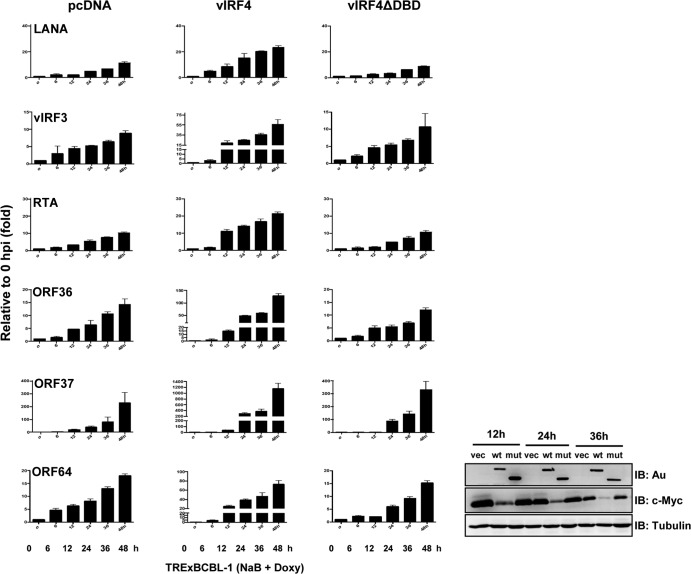

vIRF4-mediated downregulation of c-Myc expression contributes to efficient KSHV lytic replication.

Since depletion of c-Myc expression leads to the induction of KSHV reactivation in an RTA-dependent manner (32), we hypothesized that ectopic expression of vIRF4 contributes to efficient KSHV lytic replication through the downregulation of c-Myc expression. To assess this hypothesis, TRExBCBL-1 pcDNA, TRExBCBL-1 vIRF4/Au, and TRExBCBL-1 vIRF4ΔDBD/Au cells were treated with 1 μg/ml of Doxy together with sodium butyric acid (NaB; 1 mM) for various periods and subjected to RT-PCR analyses with specific primers against several KSHV genes (Fig. 6). RT-PCR analysis revealed that Doxy-induced exogenous vIRF4 expression greatly accelerated the induction of an immediate early gene (RTA), early genes (ORF36 and ORF57), late genes (ORF25 and ORF64), and latent genes (LANA and vIRF3), while vIRF4ΔDBD mutant expression did not (Fig. 6). Under these conditions, endogenous c-Myc protein levels were considerably reduced in TRExBCBL-1 vIRF4/Au cells, whereas this reduction was not observed in TRExBCBL-1 pcDNA and TRExBCBL-1 vIRF4ΔDBD/Au cells (Fig. 6, right panel). These results suggest that the vIRF4-mediated downregulation of c-Myc expression contributes to efficient KSHV lytic replication.

FIG 6.

The vIRF4-mediated downregulation of c-Myc expression contributes to efficient KSHV lytic replication. (Left) TRExBCBL-1 pcDNA, TRExBCBL-1 vIRF4/Au, and TRExBCBL-1 vIRF4ΔDBD/Au cells were treated with Doxy (1 μg/ml) for the indicated times, and cell lysates were used for RT-qPCR using specific primers for KSHV genes. (Right) Cell lysates were used for IB with anti-Au, anti-Myc, and anti-tubulin. vec, TRExBCBL-1 pcDNA cell lysates; wt, TRExBCBL-1 vIRF4/Au cell lysates; mut, TRExBCBL-1 vIRF4ΔDBD/Au cell lysates.

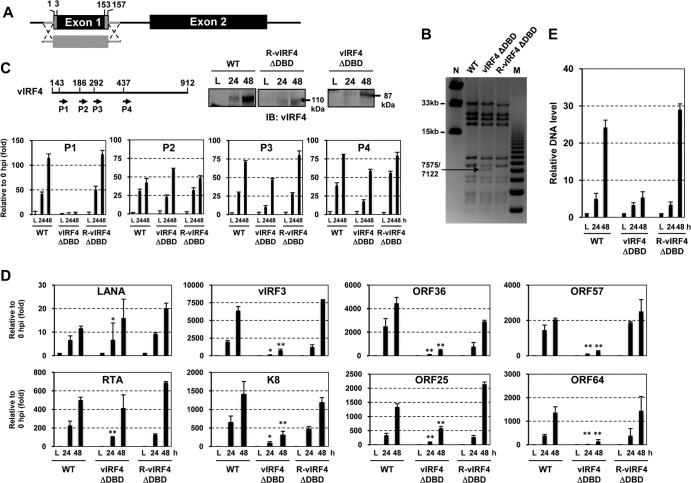

vIRF4ΔDBD KSHV mutant shows reduced lytic replication.

In order to examine the effect of vIRF4-mediated c-Myc suppression on viral lytic replication in the context of the KSHV genome, we first generated the vIRF4ΔDBD KSHV mutant by using BAC16 as a template for mutagenesis. A majority of the coding sequence of vIRF4 exon 1 was deleted from BAC16 by “scarless” mutagenesis (Fig. 7A) (27). To confirm that the recombinant BAC16 clones contained the vIRF4ΔDBD mutation, the DNA fragments containing the mutated allele were directly sequenced, and the restriction endonuclease digestion patterns of the WT and vIRF4ΔDBD BAC16 clones were also compared (Fig. 7B). Based on the DNA sequence results and the NheI and AseI enzyme digestion patterns, we selected an appropriate clone and designated it vIRF4ΔDBD. In order to rule out the presence of a second-site mutation within the BAC16-vIRF4ΔDBD genome, revertant clones were generated by homologous recombination with the PCR amplicon containing vIRF4 exon 1 and coding target sequences from the WTBAC16 and kanamycin resistance cassette portion. After confirming revertant clones via NheI and AseI enzyme digestion and DNA sequencing, we selected an appropriate clone and named it R-vIRF4ΔDBD (Fig. 7B). Next, purified WTBAC16, vIRF4ΔDBDBAC16, and R-vIRF4ΔDBDBAC16 DNAs from E. coli were transfected into the recombinant SLK cell line iSLK, which was engineered to express RTA in a tetracycline-inducible manner (25). Following selection for hygromycin resistance (Hygr), cells were treated with 1 mM NaB together with Doxy for 24 h and 48 h to induce viral lytic replication. To ascertain that the deletion of a large part of the exon 1 sequence did not affect vIRF4 splicing, we performed RT-qPCR with specific primers to amplify four different regions of the vIRF4 cDNA. This showed that the deletion of the DBD coding sequence of vIRF4 did not affect its splicing (Fig. 7C). Furthermore, immunoblotting with an anti-vIRF4 antibody showed expression of the vIRF4ΔDBD mutant in iSLK-vIRF4ΔDBDBAC16 cells (Fig. 7C, bottom left panel). We also examined the accumulation of latent (LANA), immediate early (RTA and K8), early (ORF36, vIRF3, and ORF57), and late (ORF25 and ORF64) transcripts in iSLK-WTBAC16, iSLK-vIRF4ΔDBDBAC16, and iSLK-R-vIRF4ΔDBDBAC16 cells. This showed that while the levels of LANA transcripts were similar in all three cell lines, the levels of ORF36, vIRF3, ORF57, ORF25, and ORF64 transcripts were considerably lower in iSLK-vIRF4ΔDBDBAC16 cells than in iSLK-WTBAC16 and iSLK-R-vIRF4ΔDBDBAC16 cells (Fig. 7D and E). It should be noted that the similar levels of RTA transcripts were likely due to the Doxy-mediated ectopic RTA expression (Fig. 7D). In summary, these results show that the loss of vIRF4 DBD activity led to a reduction of KSHV lytic replication.

FIG 7.

vIRF4ΔDBD KSHV mutant shows reduced lytic replication. (A and B) Construction of vIRF4ΔDBD KSHV BAC16. (A) Schematic of vIRF4ΔDBD KSHV BAC16. (B) NheI restriction enzyme digestion of WT, vIRF4ΔDBD, and R-vIRF4ΔDBD BAC16 clones. Lanes M and N indicate the midrange PFGF DNA marker and the 1-kb DNA marker, respectively. (C) WT vIRF4 or vIRF4ΔDBD mutant expression. iSLKWTBAC16, iSLKvIRF4ΔDBDBAC16, and iSLKR-R-vIRF4ΔDBDBAC16 cells were treated with Doxy (1 μg/ml) and 1 mM NaB. At 24 h and 48 h poststimulation, cell extracts were used for either RT-PCRs with four different vIRF4-specific primer pairs (P1 to P4) or IB with anti-vIRF4 antibody. (D) RT-qPCR analysis of KSHV viral gene expression. Twenty-four and 48 h after stimulation of iSLKWTBAC16, iSLKvIRF4ΔDBDBAC16, and iSLKR-R-vIRF4ΔDBDBAC16 cells with Doxy (1 μg/ml) and 1 mM NaB, KSHV gene expression was determined by RT-qPCR. The induction levels of each viral gene were calculated by comparing Doxy- and NaB-treated cells with mock-treated cells. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.001. (E) Viral genomic DNA copy numbers. Genomic DNAs were prepared from iSLKWTBAC16, iSLKvIRF4ΔDBDBAC16, and iSLKR-R-vIRF4ΔDBDBAC16 cells either mock treated (0 h; latency) or treated with 1 mM NaB (24 and 48 h). The levels of viral genomic DNA were determined by RT-qPCR and were calculated relative to those of the mock-treated samples (0 h; latency).

DISCUSSION

c-Myc is a major transcriptional factor that is involved in cell growth and proliferation and also plays an important role in the development of B-cell lymphomas (33, 34). For instance, c-Myc overexpression as a consequence of reciprocal translocation to the immunoglobulin loci has been found in various B-cell lymphomas (35). Although there are currently no reports of any c-Myc mutations or its locus rearrangements in KSHV-associated KS and PEL, growing evidence indicates that c-Myc is an important host factor in the development of KSHV-associated malignancy. Hence, it is not surprising that KSHV has evolved various mechanisms to modulate c-Myc expression to promote and regulate its own life cycle. Specifically, two KSHV latent proteins, LANA and vIRF3, have been shown to enhance the stability and function of c-Myc to enhance its transactivation activity, thereby inducing target gene expression (8–10, 36, 37). Furthermore, short hairpin RNA (shRNA)-mediated depletion of c-Myc gene expression breaks the KSHV latency program and facilitates progression into the lytic phase in an RTA-dependent manner, suggesting that c-Myc plays an important role in maintaining KSHV latency (32). Forero et al. recently reported that c-IRF4 also participates in the maintenance of KSHV latency by acting as a negative regulator of KSHV lytic gene expression (16). In this study, we identified KSHV vIRF4 as a negative regulator of c-IRF4 and c-Myc gene expression, which ultimately contributes to efficient KSHV lytic reactivation. Specifically, KSHV vIRF4 not only suppresses c-IRF4 expression but also competes with c-IRF4 for binding to the c-Myc promoter, resulting in the comprehensive suppression of c-Myc expression. These results indicate that the KSHV vIRF4 lytic protein specifically targets the expression and function of c-IRF4 to downregulate c-Myc gene expression, generating a favorable genetic environment for viral lytic replication. Thus, KSHV vIRF4 is included in the ever-growing list of viral genes that affect c-Myc expression and function, further emphasizing the important role of the c-Myc gene in the herpesviral life cycle.

Despite various approaches, including microarray, RT-qPCR, smFISH, ChIP, and immunoblot analyses, the details of how vIRF4 suppresses c-IRF4 expression are still elusive. There are several potential mechanisms that may explain how vIRF4 contributes to the deregulation of c-IRF4. c-IRF4 has been shown to bind to its promoter element, providing a positive-feedback signal to its own gene expression (38). Since KSHV vIRF4 exhibits the highest homology with c-IRF4 among nine c-IRFs, we hypothesize that vIRF4 may function as a decoy of c-IRF4 by disturbing c-IRF4's positive-feedback signal, which ultimately suppresses c-IRF4 gene expression. As shown in Fig. 1 and in Table S1 in the supplemental material, vIRF4 expression grossly affects host gene expression profiles, further supporting the role of vIRF4 as a potential transcriptional regulator. Indeed, we attempted to test whether vIRF4 competes with c-IRF4 for binding to the c-IRF4 promoter as seen with the c-Myc promoter competition. However, due to an extremely weak binding ability of c-IRF4 to its own promoter, we were not able to test this hypothesis in detail. Furthermore, we did not detect a specific interaction between vIRF4 and c-IRF4, suggesting that vIRF4 may not directly affect the interactions of c-IRF4 with other transcription factors (unpublished data). Since c-IRF4 expression is under the control of various transcription factors, such as STAT, MITF, and NF-κB (39–42), vIRF4 may suppress c-IRF4 expression indirectly, by affecting functions of other host genes, including those encoding the STAT, MITF, or NF-κB transcription factor. Additional studies should be directed toward identifying the particular mode(s) of vIRF4-mediated suppression of c-IRF4 expression.

Several recent reports have described a network of transcriptional promiscuity between c-IRF4 and c-Myc in different lineage cells or cancer cells (13, 43). In line with this, our ChIP assay identified a novel function of c-IRF4 as a transcriptional regulator of c-Myc expression in PELs. Under normal conditions, c-IRF4 was enriched on the P5 region of the c-Myc promoter, likely serving as a transcriptional activator of c-Myc expression (Fig. 5). Remarkably, vIRF4 effectively competed with c-IRF4 for occupancy on the P5 region of the c-Myc promoter (Fig. 5). This suggests that KSHV vIRF4 employs two complementary means to robustly block c-Myc gene expression: vIRF4 lowers the c-IRF4 protein level and also inhibits c-IRF4 binding to the c-Myc promoter. Interestingly, the vIRF4ΔDBD mutant demonstrated loss of function in the downregulation of c-IRF4 and c-Myc expression, suggesting that the DNA-binding activity of vIRF4 is important for these functions, although, to date, none of the KSHV vIRF1 to -4 proteins has been shown to possess a functional DNA-binding activity. However, Hew et al. recently showed the crystal structure of the vIRF1 DBD in complex with DNA, establishing vIRF1 as a potential DNA-binding protein (44). This also shows that the vIRF1 DBD binds DNA, whereas full-length vIRF1 does not, suggesting a potential cis-acting regulatory mechanism similar to that of host IRFs (44). Thus, it is worth considering that vIRF4 may directly bind unique DNA elements in a certain context of transcriptional regulation, ultimately orchestrating cellular and viral gene expression for KSHV lytic reactivation.

We showed that WT vIRF4 greatly accelerated the induction of an immediate early gene (RTA), early genes (ORF36 and ORF57), late genes (ORF25 and ORF64), and latent genes (LANA and vIRF3), while the vIRF4ΔDBD mutant did not (Fig. 6). This observation was further confirmed by using recombinant KSHV strains, i.e., WTBAC16, vIRFΔDBDBAC16, and R-vIRFΔDBDBAC16, in iSLK cells, where expression of the immediate early, early, and late genes was considerably lower with vIRFΔDBDBAC16 than with WTBAC16 and R-vIRFΔDBDBAC16 (Fig. 7). Furthermore, endogenous c-Myc protein levels were considerably reduced upon WT vIRF4 expression but not upon vIRF4ΔDBD mutant expression (Fig. 6). These data suggest a reverse correlation between the vIRF4-mediated downregulation of c-Myc expression and the vIRF4-mediated upregulation of KSHV lytic gene expression. However, it should be noted that the ΔDBD mutant loses functions other than its activity to downregulate c-Myc expression, which may also affect KSHV reactivation. Further detailed analysis is necessary to elucidate the vIRF4-mediated regulation of the KSHV life cycle. In summary, our findings presented here strongly indicate that similar to its cellular counterpart, vIRF4 works as a potential viral transcription factor to modulate host gene expression to build favorable environments for the KSHV lytic life cycle. This also suggests that KSHV has evolved novel mechanisms to maintain the fine balance between latency and viral reactivation by regulating two host factors, namely, c-Myc and c-IRF4.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This project was supported in part by NIH award CA014089 to H.-R.L.; by awards CA082057, CA31363, CA115284, CA180779, AI073099, AI105809, DE023926, and HL110609 and grants from the Hastings Foundation and the Fletcher Jones Foundation to J.U.J.; by awards DE021445 and CA134421 to P.F.; and by a grant from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute to T.H.

We thank Y. Izumiya, H. Kung, J. Myung, and J. Hass for providing reagents and also thank the Jung lab members for their support and discussions.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 11 December 2013

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/JVI.02106-13.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cesarman E, Chang Y, Moore PS, Said JW, Knowles DM. 1995. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-like DNA sequences in AIDS-related body-cavity-based lymphomas. N. Engl. J. Med. 332:1186–1191. 10.1056/NEJM199505043321802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dupin N, Diss TL, Kellam P, Tulliez M, Du MQ, Sicard D, Weiss RA, Isaacson PG, Boshoff C. 2000. HHV-8 is associated with a plasmablastic variant of Castleman disease that is linked to HHV-8-positive plasmablastic lymphoma. Blood 95:1406–1412 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sarid R, Flore O, Bohenzky RA, Chang Y, Moore PS. 1998. Transcription mapping of the Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (human herpesvirus 8) genome in a body cavity-based lymphoma cell line (BC-1). J. Virol. 72:1005–1012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bhatia K, Huppi K, Spangler G, Siwarski D, Iyer R, Magrath I. 1993. Point mutations in the c-Myc transactivation domain are common in Burkitt's lymphoma and mouse plasmacytomas. Nat. Genet. 5:56–61. 10.1038/ng0993-56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dalla-Favera R, Bregni M, Erikson J, Patterson D, Gallo RC, Croce CM. 1982. Human c-myc oncogene is located on the region of chromosome 8 that is translocated in Burkitt lymphoma cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 79:7824–7827. 10.1073/pnas.79.24.7824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rao PH, Houldsworth J, Dyomina K, Parsa NZ, Cigudosa JC, Louie DC, Popplewell L, Offit K, Jhanwar SC, Chaganti RS. 1998. Chromosomal and gene amplification in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Blood 92:234–240 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yano T, Sander CA, Clark HM, Dolezal MV, Jaffe ES, Raffeld M. 1993. Clustered mutations in the second exon of the MYC gene in sporadic Burkitt's lymphoma. Oncogene 8:2741–2748 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bubman D, Guasparri I, Cesarman E. 2007. Deregulation of c-Myc in primary effusion lymphoma by Kaposi's sarcoma herpesvirus latency-associated nuclear antigen. Oncogene 26:4979–4986. 10.1038/sj.onc.1210299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu J, Martin HJ, Liao G, Hayward SD. 2007. The Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus LANA protein stabilizes and activates c-Myc. J. Virol. 81:10451–10459. 10.1128/JVI.00804-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lubyova B, Kellum MJ, Frisancho JA, Pitha PM. 2007. Stimulation of c-Myc transcriptional activity by vIRF-3 of Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus. J. Biol. Chem. 282:31944–31953. 10.1074/jbc.M706430200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nador RG, Cesarman E, Chadburn A, Dawson DB, Ansari MQ, Sald J, Knowles DM. 1996. Primary effusion lymphoma: a distinct clinicopathologic entity associated with the Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpes virus. Blood 88:645–656 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Acquaviva J, Chen X, Ren R. 2008. IRF-4 functions as a tumor suppressor in early B-cell development. Blood 112:3798–3806. 10.1182/blood-2007-10-117838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shaffer AL, Emre NC, Lamy L, Ngo VN, Wright G, Xiao W, Powell J, Dave S, Yu X, Zhao H, Zeng Y, Chen B, Epstein J, Staudt LM. 2008. IRF4 addiction in multiple myeloma. Nature 454:226–231. 10.1038/nature07064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aldinucci D, Celegato M, Borghese C, Colombatti A, Carbone A. 2011. IRF4 silencing inhibits Hodgkin lymphoma cell proliferation, survival and CCL5 secretion. Br. J. Haematol. 152:182–190. 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2010.08497.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xu D, Zhao L, Del Valle L, Miklossy J, Zhang L. 2008. Interferon regulatory factor 4 is involved in Epstein-Barr virus-mediated transformation of human B lymphocytes. J. Virol. 82:6251–6258. 10.1128/JVI.00163-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Forero A, Moore PS, Sarkar SN. 2013. Role of IRF4 in IFN-stimulated gene induction and maintenance of Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus latency in primary effusion lymphoma cells. J. Immunol. 191:1476–1485. 10.4049/jimmunol.1202514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee HR, Brulois K, Wong L, Jung JU. 2012. Modulation of immune system by Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus: lessons from viral evasion strategies. Front. Microbiol. 3:44. 10.3389/fmicb.2012.00044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee HR, Kim MH, Lee JS, Liang C, Jung JU. 2009. Viral interferon regulatory factors. J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 29:621–627. 10.1089/jir.2009.0067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee HR, Choi WC, Lee S, Hwang J, Hwang E, Guchhait K, Haas J, Toth Z, Jeon YH, Oh TK, Kim MH, Jung JU. 2011. Bilateral inhibition of HAUSP deubiquitinase by a viral interferon regulatory factor protein. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 18:1336–1344. 10.1038/nsmb.2142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee HR, Toth Z, Shin YC, Lee JS, Chang H, Gu W, Oh TK, Kim MH, Jung JU. 2009. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus viral interferon regulatory factor 4 targets MDM2 to deregulate the p53 tumor suppressor pathway. J. Virol. 83:6739–6747. 10.1128/JVI.02353-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heinzelmann K, Scholz BA, Nowak A, Fossum E, Kremmer E, Haas J, Frank R, Kempkes B. 2010. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus viral interferon regulatory factor 4 (vIRF4/K10) is a novel interaction partner of CSL/CBF1, the major downstream effector of Notch signaling. J. Virol. 84:12255–12264. 10.1128/JVI.01484-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kanno T, Sato Y, Sata T, Katano H. 2006. Expression of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-encoded K10/10.1 protein in tissues and its interaction with poly(A)-binding protein. Virology 352:100–109. 10.1016/j.virol.2006.04.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xi X, Persson LM, O'Brien MW, Mohr I, Wilson AC. 2012. Cooperation between viral interferon regulatory factor 4 and RTA to activate a subset of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus lytic promoters. J. Virol. 86:1021–1033. 10.1128/JVI.00694-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nakamura H, Lu M, Gwack Y, Souvlis J, Zeichner SL, Jung JU. 2003. Global changes in Kaposi's sarcoma-associated virus gene expression patterns following expression of a tetracycline-inducible Rta transactivator. J. Virol. 77:4205–4220. 10.1128/JVI.77.7.4205-4220.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Myoung J, Ganem D. 2011. Generation of a doxycycline-inducible KSHV producer cell line of endothelial origin: maintenance of tight latency with efficient reactivation upon induction. J. Virol. Methods 174:12–21. 10.1016/j.jviromet.2011.03.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Toth Z, Maglinte DT, Lee SH, Lee HR, Wong LY, Brulois KF, Lee S, Buckley JD, Laird PW, Marquez VE, Jung JU. 2010. Epigenetic analysis of KSHV latent and lytic genomes. PLoS Pathog. 6:e1001013. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brulois KF, Chang H, Lee AS, Ensser A, Wong LY, Toth Z, Lee SH, Lee HR, Myoung J, Ganem D, Oh TK, Kim JF, Gao SJ, Jung JU. 2012. Construction and manipulation of a new Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus bacterial artificial chromosome clone. J. Virol. 86:9708–9720. 10.1128/JVI.01019-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Raj A, van den Bogaard P, Rifkin SA, van Oudenaarden A, Tyagi S. 2008. Imaging individual mRNA molecules using multiple singly labeled probes. Nat. Methods 5:877–879. 10.1038/nmeth.1253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gauzzi MC, Purificato C, Conti L, Adorini L, Belardelli F, Gessani S. 2005. IRF-4 expression in the human myeloid lineage: up-regulation during dendritic cell differentiation and inhibition by 1alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3. J. Leukoc. Biol. 77:944–947. 10.1189/jlb.0205090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hollis GF, Gazdar AF, Bertness V, Kirsch IR. 1988. Complex translocation disrupts c-myc regulation in a human plasma cell myeloma. Mol. Cell. Biol. 8:124–129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bemark M, Neuberger MS. 2000. The c-MYC allele that is translocated into the IgH locus undergoes constitutive hypermutation in a Burkitt's lymphoma line. Oncogene 19:3404–3410. 10.1038/sj.onc.1203686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li X, Chen S, Feng J, Deng H, Sun R. 2010. Myc is required for the maintenance of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus latency. J. Virol. 84:8945–8948. 10.1128/JVI.00244-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Barrios C, Castresana JS, Ruiz J, Kreicbergs A. 1994. Amplification of the c-myc proto-oncogene in soft tissue sarcomas. Oncology 51:13–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Keller UB, Old JB, Dorsey FC, Nilsson JA, Nilsson L, MacLean KH, Chung L, Yang C, Spruck C, Boyd K, Reed SI, Cleveland JL. 2007. Myc targets Cks1 to provoke the suppression of p27Kip1, proliferation and lymphomagenesis. EMBO J. 26:2562–2574. 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Adams JM, Harris AW, Pinkert CA, Corcoran LM, Alexander WS, Cory S, Palmiter RD, Brinster RL. 1985. The c-myc oncogene driven by immunoglobulin enhancers induces lymphoid malignancy in transgenic mice. Nature 318:533–538. 10.1038/318533a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Baresova P, Pitha PM, Lubyova B. 2012. Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus vIRF-3 protein binds to F-box of Skp2 protein and acts as a regulator of c-Myc protein function and stability. J. Biol. Chem. 287:16199–16208. 10.1074/jbc.M111.335216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fujimuro M, Wu FY, ApRhys C, Kajumbula H, Young DB, Hayward GS, Hayward SD. 2003. A novel viral mechanism for dysregulation of beta-catenin in Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus latency. Nat. Med. 9:300–306. 10.1038/nm829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lehtonen A, Veckman V, Nikula T, Lahesmaa R, Kinnunen L, Matikainen S, Julkunen I. 2005. Differential expression of IFN regulatory factor 4 gene in human monocyte-derived dendritic cells and macrophages. J. Immunol. 175:6570–6579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Grumont RJ, Gerondakis S. 2000. Rel induces interferon regulatory factor 4 (IRF-4) expression in lymphocytes: modulation of interferon-regulated gene expression by rel/nuclear factor kappaB. J. Exp. Med. 191:1281–1292. 10.1084/jem.191.8.1281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gupta S, Jiang M, Anthony A, Pernis AB. 1999. Lineage-specific modulation of interleukin 4 signaling by interferon regulatory factor 4. J. Exp. Med. 190:1837–1848. 10.1084/jem.190.12.1837 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Saito M, Gao J, Basso K, Kitagawa Y, Smith PM, Bhagat G, Pernis A, Pasqualucci L, Dalla-Favera R. 2007. A signaling pathway mediating downregulation of BCL6 in germinal center B cells is blocked by BCL6 gene alterations in B cell lymphoma. Cancer Cell 12:280–292. 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.08.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shaffer AL, Wright G, Yang L, Powell J, Ngo V, Lamy L, Lam LT, Davis RE, Staudt LM. 2006. A library of gene expression signatures to illuminate normal and pathological lymphoid biology. Immunol. Rev. 210:67–85. 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2006.00373.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pathak S, Ma S, Trinh L, Eudy J, Wagner KU, Joshi SS, Lu R. 2011. IRF4 is a suppressor of c-Myc induced B cell leukemia. PLoS One 6:e22628. 10.1371/journal.pone.0022628 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hew K, Dahlroth SL, Venkatachalam R, Nasertorabi F, Lim BT, Cornvik T, Nordlund P. 2013. The crystal structure of the DNA-binding domain of vIRF-1 from the oncogenic KSHV reveals a conserved fold for DNA binding and reinforces its role as a transcription factor. Nucleic Acids Res. 41:4295–4306. 10.1093/nar/gkt082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.