Abstract

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) core protein is essential for virus assembly. HCV core protein was expressed and purified. Aptamers against core protein were raised through the selective evolution of ligands by the exponential enrichment approach. Detection of HCV infection by core aptamers and the antiviral activities of aptamers were characterized. The mechanism of their anti-HCV activity was determined. The data showed that selected aptamers against core specifically recognize the recombinant core protein but also can detect serum samples from hepatitis C patients. Aptamers have no effect on HCV RNA replication in the infectious cell culture system. However, the aptamers inhibit the production of infectious virus particles. Beta interferon (IFN-β) and interferon-stimulated genes (ISGs) are not induced in virally infected hepatocytes by aptamers. Domains I and II of core protein are involved in the inhibition of infectious virus production by the aptamers. V31A within core is the major resistance mutation identified. Further study shows that the aptamers disrupt the localization of core with lipid droplets and NS5A and perturb the association of core protein with viral RNA. The data suggest that aptamers against HCV core protein inhibit infectious virus production by disrupting the localization of core with lipid droplets and NS5A and preventing the association of core protein with viral RNA. The aptamers for core protein may be used to understand the mechanisms of virus assembly. Core-specific aptamers may hold promise for development as early diagnostic reagents and potential therapeutic agents for chronic hepatitis C.

INTRODUCTION

Around 170 million people worldwide are infected with hepatitis C virus (HCV), and persistent virus infection causes chronic hepatitis, liver cirrhosis, and even hepatocellular carcinoma (1). The transfusion of HCV-contaminated blood is mainly responsible for the epidemic of HCV, and the accurate, sensitive identification of HCV in blood samples is critical.

Current diagnosis methods include nucleic acid testing and detection of core antigen and antibodies against HCV protein. Nucleic acid assays are labor-intensive, expensive, and prone to contamination. Detection of antibodies has some limitations, such as lack of antibodies during the early stage of infection and in immunodeficient patients, thereby leading to false-negative results (2). It is difficult to generate high-quality antibodies against core protein, although detection of HCV core antigen present in serum is highly sensitive and specific (3).

Alpha interferon (IFN-α)-based therapy is the current treatment for patients with chronic hepatitis C. Many patients do not respond to the therapy. Development of safe, effective, and well-tolerated drugs against HCV infection has been a strong motivation in academy and industry (4).

HCV is an enveloped, single-positive-strand RNA virus whose genome carries an open reading frame that is translated as a single polyprotein, which is cleaved into 10 structural and nonstructural proteins. The structural proteins including core and the envelope proteins E1 and E2 form the viral particles. The nonstructural proteins include p7, NS2, NS3, NS4A, NS4B, NS5A, and NS5B proteins. HCV core is cleaved by signal peptidase, thereby producing the 191-amino-acid (aa) immature form of core. The immature core is cleaved by a signal peptide peptidase generating a 173- to 179-amino-acid mature form of core and is trafficked from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) membrane to lipid droplets (LD). The association of the mature core protein with LD is directly related to the intracellular transport of this protein to the perinuclear area (5). HCV core protein has three functional domains: the highly basic N-terminal domain I (DI, aa 1 to 120) is involved in the interaction with HCV RNA; domain II (DII, aa 121 to 173) mediates the binding of core to LD; domain III (aa 174 to 191) is a signal peptide that is cleaved during the formation of mature core protein (6). One recent study showed that heparan sulfate attaches to core proteins to form heparan sulfate proteoglycans core proteins on the cell surface, which is important for attachment of HCV to the surfaces of hepatocytes (7). The essential role of core in the assembly of virion and other stages of virus life cycle makes this protein an attractive target for the development of effective direct-acting drugs (8). The recent development of an infectious HCV cell culture system, taking advantage of a genotype 2a patient isolate, JFH1, provides a tool for the study of the role of core in the viral life cycle and for discovery of inhibitors of viral infection (9–11).

The selective evolution of ligands by the exponential enrichment approach (SELEX) allows the isolation of aptamers that display high affinity and specificity for plenty of targets (12, 13). Aptamers can specifically recognize their targets or regulate their functions. Aptamers possess many advantages over antibodies as diagnosis reagents and therapeutic agents, including convenient synthesis, easy modification with high batch fidelity, and lack of immunogenicity (14).

In this study, we obtained aptamers for HCV core using in vitro SELEX. The selected aptamers against HCV core specifically recognize the recombinant core protein and the serum samples of hepatitis C patients but also inhibit the assembly of virion. Further study shows that these aptamers exert antiviral activity through disruption of the localization of core with lipid droplets and NS5A and blockage of core protein binding to viral RNA.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and reagents.

Huh7.5 cells and mouse monoclonal anti-NS2 antibody were kindly provided by Charles Rice (Rockefeller University, NY) (15). pJFH1 and pJFH1/GND plasmids were generously provided by Takaji Wakita (National Institute of Infectious Diseases, Tokyo, Japan) (10). Mouse monoclonal anti-NS5A antibody was from Chen Liu (University of Florida).

Expression and purification of core protein.

The protein expression vector of full-length core was constructed by PCR amplification using pJFH1 plasmid as the template. The full-length core sequence tagged with 6 His molecules at the N terminus was PCR amplified with primers, digested with NdeI and EcoRI, and inserted into pLM1 to produce pLM1-core. Core protein was expressed in Escherichia coli BL21(DE3) cells (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and purified. The protein was identified using anti-His antibody (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) via Western blotting.

In vitro selection of aptamer against core protein.

The synthesized DNA library pool with an overall complexity of ∼1014 was used for in vitro selection. The sequence of the random DNA is 5′-ACGCTCGGATGCCACTACAG(N40)CTCATGGACGTGCTGGTGA-3′, where N40 represents 40 nucleotides with equimolar incorporation of A, G, C, and T at each position. The selection and amplification procedure was performed as previously described (16, 17). After 8 rounds of selection, the amplified DNA was cloned and several clones were sequenced.

ELONA.

For enzyme-linked oligonucleotide assay (ELONA), streptavidin-precoated microtiter plates were coated with biotin-labeled aptamer. Serial dilutions of His-tagged core protein or patient serum were added into the plates and incubated at 37°C for half an hour. After washing to remove the unbound target protein, mouse monoclonal anti-His or core antibody was added into the plates at 37°C for 1 h. Peroxidase-labeled goat anti-mouse IgG was added and incubated at 37°C for 30 min. Color development was performed by addition of freshly prepared substrate solution for 10 min at room temperature. After stopping the reaction with stopping buffer, the plates were read with an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) reader and the absorbance of each sample was measured at 450 nm.

Serum samples.

The sera from HCV-infected patients, hepatitis B virus (HBV)-infected patients, or healthy donors were collected from 2009 to 2012 in Hunan Provincial Tumor Hospital. The experiments were done with the approval of the Ethics Committee of Hunan Provincial Tumor Hospital.

MTS assay.

For the MTS [3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-5-(3-carboxymethoxyphenyl)-2-(4-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium] assay, the protocol was performed as published previously (18).

Selection of resistance-conferring mutations.

HCV-infected Huh7.5 cells were treated with 100 nM C4 for 3 weeks. Control cells were maintained with 100 nM library. HCV core cDNA was recovered from cells by reverse transcription (RT)-PCR. The oligonucleotide primers used to amplify JFH1 Core cDNA were GTAGCGTTGGGTTGCGAAAG (forward) and TGGTCACCATGTAGCTGCTAC (reverse). Core amplicons were used for direct population sequencing and to generate cDNA clones with a TOPO TA Cloning kit (Invitrogen). The substitution V31A was introduced into pJFH1 plasmid by using the QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene). In vitro transcripts of wild-type JFH1 and selected mutated V31A JFH1 were generated and transfected into Huh7.5 cells, separately.

Real-time PCR assays.

Total cellular RNA was isolated using TRIzol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). The primers targeting HCV, IFN-β, G1P3, 1-8U, and GAPDH (glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase) have been reported, and real-time PCR was performed as described previously (19). Quantitative PCR (qPCR) primers for HBV DNA detection were as follows: forward, 5-GGCTTTCGGAAAATTCCTATG-3; reverse, 5-AGCCCTACGAACCACTGAAC-3.

Immunofluorescence.

Cells were seeded on glass coverslips and fixed with ice-cold acetone for 10 min at −20°C. The cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), blocked with 1:50 goat serum for 30 min at room temperature, and then incubated for 1 h with primary antibody. The cells were stained with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-labeled or Texas Red-labeled goat anti-mouse IgG for 45 min at room temperature. Lipid content was detected with the Bodipy 493/503 dye (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) for 1 h after core staining. The coverslips were extensively washed, and the nuclei were counterstained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; Vector Laboratories Inc., Burlingame, CA). Fluorescent images were obtained under a fluorescence microscope (Olympus, Japan).

Western blot analysis.

The Western blotting procedure was described previously (18). Briefly, cells were washed with PBS and lysed in radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer. Twenty micrograms of protein was resolved by SDS-PAGE, transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane, and probed with appropriate primary and secondary antibodies. The bound antibodies were detected by ECL reagent (Pierce, Rockford, IL).

ELISA.

HCV core protein was determined using the HCV core antigen ELISA kit (Ortho Clinical Diagnostics, Raritan, NJ) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, cell culture supernatants were harvested and serially diluted 1:10. The diluted supernatants were applied to the plates coated with anti-HCV core antibody. HCV core antigen was detected by addition of horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibody. The absorbance of each sample was measured at 450 nm. Core was quantified and compared to the standard curve assayed in parallel. Mean values and standard deviations (SD) for three independent experiments performed in triplicate are shown.

Co-IP and immunoblotting.

HCV-infected Huh7.5 cells were washed thrice with ice-cold PBS and lysed in lysis buffer supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktail. Cell lysates were incubated at 4°C for 30 min and centrifuged at 12,000 × g at 4°C for 15 min. The lysate was diluted before beginning coimmunoprecipitation (co-IP) to 2 μg/μl total cell protein with PBS. Two hundred micrograms of lysates was immunoprecipitated with anticore antibody. The immunocomplex was captured by adding protein G agarose bead slurry. The proteins binding to the beads were boiled in 2× Laemmli sample buffer and then subjected to SDS–12% PAGE. The protocol for immunoblotting is described above.

Intracellular virus preparation.

At the indicated time postinfection, cells were washed thrice with PBS and incubated with 0.25% of trypsin-EDTA for 2 min at 37°C. Cells were suspended in PBS and collected by centrifugation at 2,000 rpm for 3 min. The cell pellet was resuspended in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (DMEM)–10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and lysed by four freeze-thaw cycles in liquid nitrogen and a 37°C water bath, respectively. Cell debris was pelleted by centrifugation for 5 min at 4,000 rpm. The supernatant was collected and used for the focus-forming unit (FFU) assay described below.

Focus-forming assay.

The protocol for the FFU assay was performed as published previously (11). Briefly, cell supernatants were serially diluted 10-fold in complete DMEM and used to infect 104 naive Huh7.5 cells per well in 96-well plates (Corning). The inoculums were incubated with cells for 1 h at 37°C and then supplemented with fresh DMEM. The level of HCV infection was determined 3 days postinfection by immunofluorescence staining for HCV NS5A. The viral titer is expressed as focus-forming units per milliliter of supernatant (FFU/ml), determined by the average number of NS5A-positive foci detected at the highest dilutions.

Immunoprecipitated real-time PCR.

The IP protocol is described above. Protein-RNA complexes binding to beads were eluted in PBS at 70°C for 45 min. The eluted material was lysed in ice-cold TRIzol reagent, and RNA was isolated. RNA was used as the template for viral RNA detection by real-time PCR as described above.

Statistical analysis.

Differences between means of reading were compared using the Student t test. Error bars represent standard deviations.

RESULTS

Cloning and purification of HCV core.

HCV core gene was amplified and cloned into the expression vector pLM1. Core protein was expressed and purified by its N-terminal His tag. The purified core protein and control LacZ protein were detected by immunoblot analysis (Fig. 1A).

FIG 1.

Selection of aptamers against HCV core protein and binding affinity of the aptamers. (A) His-tagged core was expressed by IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside) induction in E. coli BL21(DE3). The core protein and control protein LacZ were separated on SDS-PAGE gel and stained using mouse anti-His monoclonal antibody via Western blotting. (B) FITC-labeled DNA pools from library round 1 and round 8 were incubated with agarose beads conjugated with HCV core or control protein LacZ in binding buffer. The density of the fluorescence was measured and normalized to library. (C) Binding affinity of core aptamers. Each biotin-labeled aptamer was added to the microtiter plate, and an ELONA was performed. Purified His-tagged core, NS5A, or control protein LacZ was added to the plates. Mouse monoclonal anti-His antibody and HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG were used as primary and secondary antibodies, respectively. Color development was performed, and the plates were read with an ELISA reader. The absorbance of each sample was measured at 450 nm and normalized to library. The data represent the averages of five different experiments. **, P < 0.01 versus library. (D) Binding affinity of core aptamers to core protein from lysates of HCV-infected hepatocytes. Biotin-labeled library, Cnew, C4, C7, C42, C97, C103, or C104 was added to the microtiter plate previously coated with streptavidin. Lysates of HCV-infected Huh7.5 or noninfected Huh7.5 cells were added to the plates. After washing, mouse anti-HCV core, NS2, or NS5A monoclonal antibody was added and incubated at 37°C for 1 h. HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG was added to the plates. The data were obtained as described for panel C and represent the means of 3 different experiments. **, P < 0.01 versus library.

Selection of aptamers against HCV core protein.

A nucleotide library was obtained from a pool of ∼1014 single-stranded DNA molecules containing a random fragment of 40 nucleotides flanked by 5′ and 3′ common primers as conserved linkers to amplify the selection process. The DNA library was mixed with beads conjugated with His-tagged core protein. Core-DNA complexes were precipitated with beads, and pellets were washed. DNAs were recovered, amplified with PCR, and used for the next rounds of selection. To remove the nonspecifically bound DNA, we applied the counterselection step using control protein LacZ in each cycle. After 8 rounds of selection, there was an increase in the binding of round 8 DNA pools to core protein compared to that of the round 1 pools (Fig. 1B). The selected aptamers were cloned and sequenced. We selected some aptamers and named them Cnew, C4, C7, C42, C97, C103, and C104. Their sequences are listed in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Sequences of core aptamers

| Aptamer designation | Sequence |

|---|---|

| Cnew | AGTGATGGTTGTTATCTGGCCTCAGAGGTTCTCGGGTGTGGTCA |

| C4 | GCACGCCAGACCAGCCGTCCTCTCTTCATCCGAGCCTTCACCGAGC |

| C42 | CATATCAGACACAACACAACAAAACACATACATACAACGCC |

| C97 | TAACACACACAACTTAAAATCATACAAAAAAGAGTAAATGC |

| C104 | CCAAATACTACCGCAAAAACCACCTCCCCCTCGATAATAGC |

| C7 | ACTATACACAAAAATAACACGACCGACGAAAAAACACAACC |

| C103 | TACCACACATGCAGACCCACACAAATACATACTAGAGACAC |

Analysis of binding affinity of aptamers for HCV core protein.

An ELONA was performed to show the binding affinity of aptamers for core protein. Aptamers Cnew, C4, C7, C42, C97, C103, and C104 showed a higher affinity for recombinant core protein than control library, while they did not display apparent binding affinity for recombinant LacZ or NS5A protein (Fig. 1C). Various aptamers bound to core protein, and this interaction was retained in the presence of excess yeast tRNA in the binding buffer, suggesting that their binding to core was specific. We examined whether the aptamer for core could bind core protein in lysates of HCV-infected hepatocytes. The aptamers showed specific binding affinity to core protein from lysates of virally infected cells in comparison with the control library, while they displayed no binding affinity for NS2 or NS5A protein from lysates of virally infected cells (Fig. 1D).

Detection of core protein in serum samples from HCV-infected patients by core aptamer.

A standard curve for core detected by ELONA or ELISA is shown in Fig. 2A. Next, we examined whether the selected aptamer could detect the serum samples from hepatitis C patients. Streptavidin-precoated microtiter plates were coated with biotin-labeled C7 aptamer. The serum samples from hepatitis C, hepatitis B, or healthy donors were added into the plates. Mouse monoclonal anti-HCV core antibody was added into the plates, followed with HRP-labeled secondary antibody incubation. While negative results were shown in serum samples from 105 HBV-infected patients and 125 healthy donors, serum samples in 412 of 441 HCV-infected patients were identified as positive. When HCV RNA copies in the sera were plotted against core protein concentration in the samples, we observed that the core protein concentration was proportional to the number of copies of viral RNA in the samples (Fig. 2B).

FIG 2.

Detection of HCV core in serum samples from HCV-infected patients by core aptamer. (A) A standard curve for core detected by ELONA or ELISA is shown. Both ELONA and ELISA were performed to determine the detection limitation of HCV core protein using C7 aptamer. The absorbance of each sample was measured at 450 nm. A standard curve was created by plotting the mean absorbance for each standard concentration (y axis) against the core protein concentration (x axis). Mean values and standard deviations for three independent experiments performed in triplicate are shown. (B) Detection of core in the serum samples from hepatitis C patients by core aptamer and HCV viral titer is proportional to core protein concentration in the samples. Streptavidin-precoated microtiter plates were coated with biotin-labeled core aptamer C7. The serum samples from HCV-infected patients, HBV-infected patients, or healthy donors were added into the plates. Color development was performed, and the absorbance of each sample was measured at 450 nm. HCV RNA copy numbers in the sera measured by quantitative real-time PCR were plotted against core concentration in serum samples.

Inhibition of infectious virus production by core-specific aptamers.

Our data showed that core aptamers specifically bind to core protein, so we decided to test whether the aptamers have an effect on HCV infection in an infectious cell culture system. There was no significant difference in the intracellular and extracellular viral RNA levels between aptamer-treated cells and the control library group (Fig. 3A and B). Uptake efficiency for C4 and C7 by HCV-infected Huh7.5 cells is shown in Fig. 3C. Colocalization of core-specific aptamers with core protein in the HCV-infected hepatocytes was demonstrated in Fig. 3D.

FIG 3.

Inhibition of infectious virus production by aptamers against core. (A and B) Effects of core aptamers on the intracellular (A) or extracellular (B) viral RNA level in hepatocytes. JFH1 virus suspension at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.1 was used to infect Huh7.5 cells for 3 days. The cells were treated by aptamer or library for 72 h. Intracellular or extracellular HCV RNA was measured by real-time PCR. The data represent the means of 3 different experiments. (C) Uptake efficiency of core-specific aptamers by HCV-infected hepatocytes. HCV-infected Huh7.5 cells were inoculated with different doses of Cy5-labeled aptamers. At the indicated time points, the virus-containing supernatant and the cells were collected separately. The cells were suspended in 1 ml fresh DMEM and then were subjected to four freeze-and-thaw cycles to collect the intracellular Cy5-labeled aptamers. The intracellular and extracellular supernatants were transported to the black 96-well plate at 100-μl volume per well. Then, the extracellular and intracellular Cy5 signal absorbances at 647 nm were measured by microplate reader. The percentages of the intracellular and the extracellular efficiencies were relative to the positive ones, which were the fresh culture media to which were added the Cy5-labeled aptamers at the same concentration. The data represent three independent experiments performed in triplicate. (D) Colocalization of core-specific aptamers with HCV core protein in the HCV-infected hepatocytes. HCV-infected Huh7.5 cells were treated with Cy5-labeled aptamers for 24 h. The cells were fixed with ice-cold acetone for 10 min at −20°C. The cells were washed with PBS, blocked with 1:50 goat serum for 30 min at room temperature, and then incubated for 1 h with mouse monoclonal anticore antibody. The cells were stained with Texas Red-labeled goat anti-mouse antibody for 45 min at room temperature. The nuclei were counterstained with DAPI. Fluorescent images were obtained under a fluorescence microscope. (E and F) Effects of core aptamers on the extracellular (E) or intracellular (F) core protein level in HCV-infected hepatocytes. The cells were treated as described for panel A. Core protein in cell culture supernatant or inside the cells was measured by core protein-specific ELISA. Means and standard deviations of three independent experiments performed at least in triplicate are shown. (G) Titration of infectious virus particles produced in the presence of core aptamers by focus-forming unit assay. The cells were treated with 10 nM or 100 nM aptamer or library for 72 h. The extracellular and intracellular virus particles were harvested 72 h postinfection, and titers were determined by FFU assay on naive Huh7.5 cells. The data represent the averages of three different experiments. (H) Effects of core aptamer on viability of HCV-infected Huh7.5 cells. HCV-infected Huh7.5 cells were treated by aptamers for 72 h. The effect of aptamer on viability of the cells was measured by MTS assay. The data were normalized with the control and represent means of three independent experiments. *, P < 0.05 versus library-treated cells. (I) Core-specific aptamers do not affect hepatitis B viral DNA replication. HepG2.2.15 cells were inoculated with different doses of aptamers for 72 h. Intracellular HBV DNA was detected with real-time PCR and normalized with GAPDH. The data represent three independent experiments.

As a surrogate for virus production, we quantified the secretion of core protein into the culture medium of virus-infected cells in either aptamer-treated cells or the control group using ELISA. There were no differences in the levels of extracellular core protein between aptamer-treated cells and the control group (Fig. 3E). To determine whether the secreted core protein was consistent with the expression of intracellular core protein, we measured the intracellular core protein using ELISA. No difference in the intracellular core protein level between the aptamer-treated and the control groups was observed (Fig. 3F). The release efficiency (the percentage of extracellular core over total core protein) for the aptamer-treated cells was comparable to that of the library-treated group.

HCV core protein plays an essential role in infectious virus production (20). To determine whether core aptamers affect infectious virus production, we collected the supernatants of virus-infected Huh7.5 cells in the presence of core aptamers or library and used them to infect naive Huh7.5 cells. The titers of infectious viruses in the supernatants of naive Huh7.5 cells were determined. The levels of extracellular infectious viruses were reduced in the cells with aptamer treatment in comparison with library-treated cells (Fig. 3G). To examine whether a decrease in infectious HCV in the supernatants was attributable to defective virion assembly, we determined cell-associated infectivity. Intracellular infectious virions in aptamer-treated cells were lower than those in library-treated cells (Fig. 3G). The concentration of aptamers used in the study showed no apparent toxic effect to the cells (Fig. 3H). All the data indicate that core-specific aptamers inhibit the infectious virus production by suppressing the assembly of infectious virus particles. Aptamers did not affect hepatitis B viral DNA infection (Fig. 3I), implying that aptamers against core specifically inhibit HCV infection.

HCV core aptamers do not induce IFN-β and interferon-stimulated genes (ISGs) in virus-infected hepatocytes.

Our data showed that aptamer against core inhibits the assembly of infectious viral particles. The presence of DNA molecules inside or outside the cells may cause a nonspecific induction of IFN, which is likely to lead to an antiviral effect. To exclude the possibility that inhibition of infectious virus production by core aptamers is due to the aptamer-induced innate response, we examined the expression of IFN-β in aptamer- or library-treated cells. IFN-β was not induced in aptamer-treated hepatocytes (Fig. 4A). Core-specific aptamers did not induce G1P3 and 1-8U in HCV-infected hepatocytes (Fig. 4B and C). All the data suggest that the inhibition of infectious virus production by core aptamers is not due to aptamer-induced innate response.

FIG 4.

Core aptamers do not stimulate innate immunity in HCV-infected human hepatocytes. A JFH1 virus suspension at an MOI of 0.1 was used to infect Huh7.5 cells for 3 days. The cells were treated by 100 nM aptamer or library. Total cellular RNA was isolated. The levels of IFN-β (A), G1P3 (B), and 1-8U (C) mRNA were examined by real-time PCR and normalized with GAPDH. The data represent means of three different experiments.

Domain I and domain II of core protein are involved in the antiviral effects mediated by core-specific aptamers.

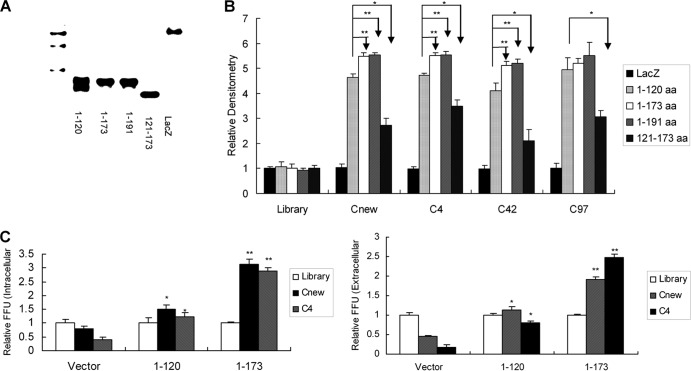

To identify the residues of core protein involved in aptamer binding and inhibition of virus assembly, we generated different truncated versions of core. The expression of different truncated versions of core protein was confirmed using Western blotting (Fig. 5A). ELONA was used to determine the truncated version to which the aptamers bind. Deletion of domain III of core did not affect the affinity for core aptamers. Domain I and domain II of core are involved in the binding of aptamers to the protein (Fig. 5B). The data suggest that the binding region of aptamers may localize inside domains I and II of core protein. To further confirm that core aptamers bind to domains I and II of core protein and inhibit the production of infectious viral particles, we conducted competition experiments. The levels of both extracellular and intracellular infectious viruses in cells transfected with plasmid containing domains I and II of core with aptamer treatment were markedly higher than those in control cells (Fig. 5C). All the data suggested that domain I and domain II of core protein are involved in the inhibition of virus assembly by core-specific aptamers.

FIG 5.

Domain I and domain II of core protein are involved in the inhibition of infectious virus production by core-specific aptamers. (A) Confirmation of the expression of different domains of core protein by Western blotting. Different domains of core gene were cloned into expression vector separately. Different truncated versions of core protein were expressed and purified. The purified protein was detected by Western blotting. (B) Binding affinity of core aptamers to domain I or domain II of core protein. Biotin-labeled core aptamer or library was added to the microtiter plate previously coated with streptavidin, and ELONA was performed. Purified different truncated versions of core protein were added to the plates. LacZ protein was used as a control. ELONA was performed as described for Fig. 1C. Results are the averages of three independent experiments performed in triplicate. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01. (C) Domains I and II of core protein are involved in the inhibition of infectious virus production by aptamers. A JFH1 virus suspension at an MOI of 0.1 was used to infect Huh7.5 cells for 3 days, and the cells were transfected with plasmids containing different truncated versions of core. The cells were then treated by 100 nM aptamer or library for 72 h. The supernatants and intracellular virus particles were harvested, and titers were determined by FFU assay. The infectivity titers in the supernatant or inside the cells with aptamer treatment were normalized to the library-treated group, and the data represent 3 different infections. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01 versus vector-transfected cells.

Core aptamers disrupt the localization of core with lipid droplets and block the interaction between core and NS5A protein.

The region of core required for associated with lipid droplets, a prerequisite of virion production, is located in domain II. Localization of core protein with lipid droplets is critical for infectious HCV production (21). Disrupting the interaction between core and lipid droplet may prevent virion production. To address this hypothesis, we examined the subcellular localization of core protein with lipid droplets in HCV-infected Huh7.5 cells with aptamer treatment by immunofluorescence analysis. Core colocalized with lipid droplets in cells with library treatment, whereas their localization was decreased in aptamer-treated cells (Fig. 6A). Interaction of core with NS5A protein is critical for infectious virus production (20). Disruption of the interaction of core with NS5A protein may decrease infectious virus production. To prove this, we analyzed the interaction of core with NS5A protein by co-IP experiments. The amounts of core or NS5A protein were comparable in aptamer-treated or library-treated cells (Fig. 6B, lower panel). Core protein in immunoprecipitates with an equal amount of NS5A protein in aptamer-treated HCV-infected Huh7.5 cells was lower than that in the library group (Fig. 6B, upper panel). The data showed that core-specific aptamers blocked the interaction between core and NS5A protein in HCV-infected hepatocytes. All the data suggested that core-specific aptamers inhibit HCV infection by disrupting the localization of core with lipid droplets and blocking the interaction of core with NS5A protein.

FIG 6.

Core aptamers disrupt the localization of core with lipid droplets and block the interaction between core and NS5A protein. (A) Subcellular localization of core protein with lipid droplets in HCV-infected hepatocytes with library or aptamer treatment. Seventy-two hours after library or core aptamer treatment, the cells were fixed with ice-cold acetone and stained with antibody against core (red). Lipid droplets were detected with the Bodipy 493/503 dye (green), followed by nuclear counterstaining with DAPI. An identical setting was maintained for image capture. Representative images are shown. (B) Effects of aptamer on the interaction between core and NS5A protein. Protein was isolated from the HCV-infected Huh7.5 cells with aptamer or library treatment and immunoprecipitated with antibodies against NS5A or mouse IgG conjugated with agarose beads, respectively. The proteins binding to the beads were boiled and subjected to SDS-PAGE. The proteins were transferred onto PVDF membrane and allowed to react with primary and secondary antibodies. Core protein was detected with Western blotting and quantified by densitometry in comparison with NS5A protein in the immunoprecipitates. Protein from HCV-infected Huh7.5 with aptamer or library treatment used for equal loading is shown as the input. The input core or NS5A protein was detected with Western blotting and quantified by densitometry. The data represent the means of 3 independent experiments. *, P < 0.05 versus library-treated cells.

Core-specific aptamers block the association of core protein with viral RNA.

To further define the mechanisms of inhibition of infectious virus production by core-specific aptamers, we analyzed the association of core protein with viral RNA in HCV-infected hepatocytes with aptamer or library treatment by IP real-time PCR. The cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-core protein antibody or control IgG. Total RNA prepared from each immunoprecipitate was subjected to real-time PCR to detect viral RNA. The levels of HCV RNA from cell lysates were comparable in aptamer- and library-treated cells. However, viral RNA binding to core protein in aptamer-treated cells was much lower than that in the library-treated group (Fig. 7). These data demonstrate that core-specific aptamers disrupt the association between core protein and viral RNA, thereby inhibiting the assembly of infectious viral particles.

FIG 7.

Core-specific aptamers block the association of core protein with viral RNA. IP real-time PCR for HCV RNA in virus-infected hepatocytes with aptamer or library treatment was performed to examine the association between core protein and viral RNA. A JFH1 virus suspension at an MOI of 0.1 was used to infect Huh7.5 cells for 3 days. The cells were treated by 100 nM each aptamer or library for 72 h. After IP with mouse monoclonal anticore antibody or mouse control IgG, immunoprecipitates were eluted. RNA in the immunocomplexes was isolated, and real-time PCR was carried out as described in Materials and Methods. The data represent the means of three different experiments. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001 versus library.

Isolation and characterization of JFH1-resistant variants.

Viral target-based inhibitor allows for the selection of resistant viruses. To identify amino acid mutations that confer resistance to core aptamer, JFH1-infected Huh7.5 cells were treated with 100 nM C4 for 3 weeks. Control cells were maintained with 100 nM library. Mutations within core associated with reduced susceptibility to C4 were selected and identified by sequence analysis of core cDNA isolated by RT-PCR from control and aptamer-treated cells. The substitution at core residue 31 (V31A substitution) was identified.

To evaluate the contribution of the selected specific amino acid substitution to resistance, the V31A substitution was introduced into JFH1. The sensitivity of the variant to C4 was assessed in the infectious cell culture system. The V31A substitution caused a decrease in C4 potency (Fig. 8). The data suggested that the selected V31A substitution within core is the major resistance substitution identified.

FIG 8.

The V31A substitution in core is the major selective resistance mutation identified. Selection of resistance-conferring mutations was performed. Huh7.5 cells were infected with medium of Huh7.5 cells transfected with RNA from wild-type (WT) or the selected V31A viral clone. The effect of C4 on the intracellular and extracellular infectious FFU of the wild-type and the selected V31A virus was examined as described for Fig. 3E. The infectivity titers inside the cells (A) and the supernatant (B) with C4 treatment were normalized to the control group. The data represent 3 independent infections. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01 versus control cells.

DISCUSSION

Although the common serological tests to detect HCV infection rely on the detection of antibodies against the virus, these tests cannot distinguish between individuals who have resolved their infection and those who remain actively infected with the virus. The HCV core antigen test detects circulating core protein and identifies individuals who are actively infected with HCV. Moreover, the HCV core antigen test can be utilized to detect the early phase of HCV infection prior to the development of antibodies, both in the blood bank setting and in the diagnostic laboratory (22). However, it is difficult to generate high-quality antibodies against core protein, although detection of HCV core present in serum is highly sensitive and specific (3). An aptamer-based detection assay is recognized as a promising molecular diagnostic method (23).

Many chronic hepatitis C patients do not respond to the current therapy. Future regimens will incorporate multiple new agents directly targeting the virus to increase the efficacy of treatment. The protease inhibitors have entered into the clinic for HCV-infected individuals recently (24). There will be plenty of patients resistant to the current therapy (25, 26). It is desirable to seek a combination therapy for HCV infection that targets different steps of the virus life cycle. It is logical to design antiviral therapies targeting the viral core protein critical for the virus assembly.

Here, we reported the selection of aptamers against HCV core protein, the detection of HCV infection, and the suppression of infectious virus production by these aptamers. Our aptamers have sequences that are different from other recently described RNA aptamers selected for core (23). The difference might be due to the selection technique used. We used SELEX to select DNA aptamers against core protein in our study, while the RNA aptamers for core were used in their study. Moreover, the differences may be attributed to the source of core protein, since our aptamers were selected by using the core (aa 1 to 191) from genotype 2a JFH1, whereas those obtained in the other study were isolated by using the core protein (aa 2 to 114) of genotype 1a. RNA aptamer is more unstable than DNA aptamer and is particularly susceptible to nuclease degradation.

This study showed that our aptamers bound core protein of genotype 2a. Importantly, the core-specific aptamers can detect the virus in serum samples from patients infected by HCV with different genotypes, suggesting that different genotypes of HCV share aptamers binding sites. This method is highly consistent with the detectable result of HCV RNA in the serum samples of HCV patients. The data indicate that our aptamers may be utilized to diagnose early HCV infection by detecting core antigen present in the serum during the early stage of infection and before virus clearance.

Our data showed that core-specific aptamers disrupt the localization of core with lipid droplets and prevent the association of core protein with viral RNA. Although the aptamers against core were found to bind core protein, the details of the residues involved in the interaction between aptamers and core protein remain to be explored. Determination of these residues may provide information about the essential functional regions of core protein. In addition, the aptamers can be used with core protein to understand the mechanisms of virus assembly and the interaction between core and cellular proteins. Anti-HIV Gag protein aptamers can be used to examine the Gag-HIV RNA interactions (27). The interaction between the aptamers for HIV reverse transcriptase and reverse transcriptase provides a model for the study of the mechanisms of how these aptamers act as broad-spectrum inhibitors of HIV reverse transcriptase (28). All these examples illustrate the potential use of aptamers in virology.

One recent study reported that inhibition of viral infection by aptamers might be due to the aptamer-induced innate immune response (29). However, most studies suggest that inhibition of virus infection by aptamers targeting different viral proteins can be attributed to suppression of viral protein by the aptamers themselves (30–33). Consistent with these reports, our study showed that the aptamers for core protein do not induce IFN-β and ISGs, indicating that inhibition of infectious virus production by core aptamers is not due to the innate immune response.

In summary, our study provides the first evidence of direct antiviral activity of aptamers for HCV core protein in the infectious cell culture system. These results demonstrate the power of the SELEX approach for the selection of inhibitors for viral infection and the exploration of the mechanisms of viral replication. The data suggest that aptamers against core protein inhibit the production of infectious viral particles by disrupting the localization of core with lipid droplets and preventing the association of core protein with viral RNA. Core-specific aptamers may hold promise for development as early diagnostic reagents for HCV infection and potential therapeutic agents for hepatitis C patients.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge Charles Rice for the gift of Huh7.5 cells and Takaji Wakita for pJFH1 and pJFH1/GND plasmids. We thank Chen Liu for helpful discussions.

This work was supported by a National Science and Technology Major Project of the Ministry of Science and Technology of China (2009ZX10004-312) and by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81271885).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 4 December 2013

REFERENCES

- 1.Lavanchy D. 2009. The global burden of hepatitis C. Liver Int. 29(Suppl 1):74–81. 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2008.01934.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gaudy C, Thevenas C, Tichet J, Mariotte N, Goudeau A, Dubois F. 2005. Usefulness of the hepatitis C virus core antigen assay for screening of a population undergoing routine medical checkup. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43:1722–1726. 10.1128/JCM.43.4.1722-1726.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bouvier-Alias M, Patel K, Dahari H, Beaucourt S, Larderie P, Blatt L, Hezode C, Picchio G, Dhumeaux D, Neumann AU, McHutchison JG, Pawlotsky JM. 2002. Clinical utility of total HCV core antigen quantification: a new indirect marker of HCV replication. Hepatology 36:211–218. 10.1053/jhep.2002.34130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rice CM. 2011. New insights into HCV replication: potential antiviral targets. Top. Antivir. Med. 19:117–120 http://www.iasusa.org/sites/default/files/tam/19-3-117.pdf [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yi M, Ma Y, Yates J, Lemon SM. 2009. Trans-complementation of an NS2 defect in a late step in hepatitis C virus (HCV) particle assembly and maturation. PLoS Pathog. 5:e1000403. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cerutti A, Maillard P, Minisini R, Vidalain PO, Roohvand F, Pecheur EI, Pirisi M, Budkowska A. 2011. Identification of a functional, CRM-1-dependent nuclear export signal in hepatitis C virus core protein. PLoS One 6:e25854. 10.1371/journal.pone.0025854 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shi Q, Jiang J, Luo G. 2013. Syndecan-1 serves as the major receptor for attachment of hepatitis C virus to the surfaces of hepatocytes. J. Virol. 87:6866–6875. 10.1128/JVI.03475-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Strosberg AD, Kota S, Akahashi TV, Snyder JK, Mousseau G. 2010. Core as a novel viral target for hepatitis C drugs. Virus 2:1734–1751. 10.3390/v2081734 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lindenbach BD, Evans MJ, Syder AJ, Wolk B, Tellinghuisen TL, Liu CC, Maruyama T, Hynes RO, Burton DR, McKeating JA, Rice CM. 2005. Complete replication of hepatitis C virus in cell culture. Science 309:623–626. 10.1126/science.1114016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wakita T, Pietschmann T, Kato T, Date T, Miyamoto M, Zhao Z, Murthy K, Habermann A, Krausslich HG, Mizokami N, Bartenschlager R, Liang TJ. 2005. Production of infectious hepatitis C virus in tissue culture from a cloned viral genome. Nat. Med. 11:791–796. 10.1038/nm1268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhong J, Gastaminza P, Cheng G, Kapadia S, Kato T, Burton DR, Wieland SF, Uprichard SL, Wakita T, Chisari FV. 2005. Robust hepatitis C virus infection in vitro. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102:9294–9299. 10.1073/pnas.0503596102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ellington AD, Szostak JW. 1990. In vitro selection of RNA molecules that binds specific ligands. Nature 346:818–822. 10.1038/346818a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tuerk C, Gold L. 1990. Systematic evolution of ligands by exponential enrichment: RNA ligands to bacteriophage T4 DNA polymerase. Science 249:505–510. 10.1126/science.2200121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Keefe AD, Pai S, Ellington A. 2010. Aptamers as therapeutics. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 9:537–550. 10.1038/nrd3141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blight KJ, McKeating JA, Marcotrigiano J, Rice CM. 2002. High permissive cell lines for subgenomic and genomic hepatitis C virus RNA replication. J. Virol. 76:13001–13014. 10.1128/JVI.76.24.13001-13014.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tan W, Wang H, Chen Y, Zhang X, Zhu H, Yang C, Yang R, Liu C. 2011. Molecular aptamers for drug delivery. Trends Biotechnol. 29:634–640. 10.1016/j.tibtech.2011.06.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang Z, Zhao Z, Xu L, Wu X, Zhu H, Tan W, Fang X. 2011. Hepatitis C virus core protein detection by DNA aptamer. Scientia Sinica Chimica 41:1312–1318. 10.1360/032011-198 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang D, Xue B, Wang X, Yu X, Liu N, Gao Y, Zhu H. 2013. 2-Octynoic acid inhibits hepatitis C virus infection through activation of AMP-activated protein kinase. PLoS One 8:e64932. 10.1371/journal.pone.0064932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang D, Liu N, Zuo C, Lei S, Wu X, Zhou F, Liu C, Zhu H. 2011. Innate immune response of primary human hepatocytes with hepatitis C viral infection. PLoS One 6:e27552. 10.1371/journal.pone.0027552 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Masaki T, Suzuki R, Murakami K, Aizaki H, Ishii K, Murayama A, Date T, Matsuura Y, Miyamura T, Wakita T, Suzuki T. 2008. Interaction of hepatitis C virus nonstructural protein 5A with core protein is critical for the production of infectious virus particles. J. Virol. 82:7964–7976. 10.1128/JVI.00826-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Counihan NA, Rawlison SM, Lindenbach BD. 2011. Trafficking of hepatitis C virus core protein during virus particle assembly. PLoS Pathog. 7:e1002302. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dawson GJ. 2012. The potential role of HCV core protein antigen testing in diagnosing HCV infection. Antivir. Ther. 17:1431–1435. 10.3851/IMP2463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee S, Kim YS, Jo M, Jin M, Lee DK, Kim S. 2007. Chip-based detection of hepatitis C virus using RNA aptamers that specifically bind to HCV core protein. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 358:47–52. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.04.057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gottwein JM, Scheel TK, Jensen TB, Ghanem L, Bukh J. 2011. Differential efficacy of protease inhibitors against HCV genotypes 2a, 3a, 5a, and 6a NS3/4A protease recombinant virus. Gastroenterology 141:1067–1079. 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Halfon P, Locarnini S. 2011. Hepatitis C virus resistance to protease inhibitors. J. Hepatol. 55:192–206. 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.01.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shindo H, Maekawa S, Komase K, Sueki R, Miura M, Kadokura M, Shindo K. 2012. Characterization of naturally occurring protease inhibitor-resistance mutations in genotype 1b hepatitis C virus patients. Hepatol. Int. 6:482–490. 10.1007/s12072-011-9306-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ramalingam D, Duclair S, Datta SAK, Ellington A, Rein A, Prasad VR. 2011. RNA aptamers directed to human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Gag protein bind to matrix and nucleocapsid domains and inhibit virus production. J. Virol. 85:305–314. 10.1128/JVI.02626-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ditzler MA, Bose D, Shkriabai N, Marchand B, Sarafiano SG, Kvaratskhelia G, Burke DH. 2011. Broad-spectrum aptamer inhibitors of HIV reverse transcriptase closely mimic natural substrates. Nucleic Acids Res. 39:8237–8247. 10.1093/nar/gkr381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hwang SY, Sun HY, Lee KH, Oh BH, Cha YJ, Kim BH, Yoo JY. 2012. 5-Triphosphate-RNA-independent activation of RIG-I via RNA aptamer with enhanced antiviral activity. Nucleic Acids Res. 40:2724–2733. 10.1093/nar/gkr1098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bentham M, Holmes K, Forrest S, Rowlands DJ, Stonehouse NJ. 2012. Formation of higher-order foot-and-mouth disease virus 3Dpol complexes is dependent on elongation activity. J. Virol. 86:2371–2374. 10.1128/JVI.05696-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moore MD, Cookson J, Coventry VK, Sproat B, Rabe L, Cranston RD, McGowan I, James W. 2011. Protection of HIV neutralizing aptamers against rectal and vaginal nucleases: implications for RNA-based therapeutics. J. Biol. Chem. 286:2526–2535. 10.1074/jbc.M110.178426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Van Melckebeke H, Devany M, Di Primo C, Beaurain F, Toulme JJ, Bryce DL, Boisbouvier J. 2008. Liquid-crystal NMR structure of HIV TAR RNA bound to its SELEX RNA aptamer reveals the origins of the high stability of the complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105:9210–9215. 10.1073/pnas.0712121105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wheeler LA, Trifonova R, Vrbanac V, Basar E, McKernan S, Xu Z, Seung E, Deruaz M, Dudek T, Einarsson JI, Yang L, Allen TM, Luster AD, Tager AM, Dykxhoorn DM, Lieberman J. 2011. Inhibition of HIV transmission in human cervicovaginal explants and humanized mice using C4 aptamer-siRNA chimeras. J. Clin. Invest. 121:2401–2412. 10.1172/JCI45876 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]