ABSTRACT

One question that continues to challenge influenza A research is why some strains of virus are so devastating compared to their more mild counterparts. We approached this question from an immunological perspective, investigating the CD8+ T cell response in a mouse model system comparing high- and low-pathological influenza virus infections. Our findings reveal that the early (day 0 to 5) viral titer was not the determining factor in the outcome of disease. Instead, increased numbers of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells and elevated effector function on a per-cell basis were found in the low-pathological infection and correlated with reduced illness and later-time-point (day 6 to 10) viral titer. High-pathological infection was associated with increased PD-1 expression on influenza virus-specific CD8+ T cells, and blockade of PD-L1 in vivo led to reduced virus titers and increased CD8+ T cell numbers in high- but not low-pathological infection, though T cell functionality was not restored. These data show that high-pathological acute influenza virus infection is associated with a dysregulated CD8+ T cell response, which is likely caused by the more highly inflamed airway microenvironment during the early days of infection. Therapeutic approaches specifically aimed at modulating innate airway inflammation may therefore promote efficient CD8+ T cell activity.

IMPORTANCE

INTRODUCTION

Clearance of virus-infected cells is the raison d'etre of the CD8+ T cell. However, CD8+ T cells can also contribute significant immunopathology (1), which may partially account for the wide range of disease severity seen during influenza virus infection. Yet in the absence of CD8+ T cells, virus clearance is delayed, which may lead to exacerbated morbidity and mortality (2, 3). Disparate pathologies can be observed when comparing multiple strains of influenza virus and even when comparing the same strain in two different individuals. Identifying the mechanism of CD8+ T cell-induced immunopathology therefore remains an important area of focus (4).

Epithelial cells at the site of influenza virus infection in the airway microenvironment initiate an early and rapid cascade of cytokine production, followed by local inflammation and ensuing responses (5). Nevertheless, some strains are able to subvert these early responses, which may result in prolonged or increased inflammation and excessive production of cytokines and chemokines. This is exemplified by the hypercytokinemia seen in highly pathogenic H5N1 avian influenza infection (6–8). Although highly pathogenic H5N1 avian influenza viruses have been unable to efficiently cross over to the human population thus far, mortality continues to hover around 60% (http://www.who.int/csr/disease/avian_influenza/en/). In addition, the H1N1 swine-origin influenza virus (SOIV) pandemic of 2009 has also been marked by elevated proinflammatory cytokine production in patients who suffered severe infections (9).

It has been established that initiation of the adaptive response is heavily influenced by innate immunity (10). CD8+ T cell activation in its most general terms requires dendritic cell (DC) ligation and assistance from T helper cells. Other reports have shown that NK cell activity during the immune response can affect CD8+ T cells (11) and that even the specific type of target cell can regulate CD8+ T cell effector function (12). With time, as demonstrated in chronic infections, CD8+ T cells can become exhausted and lose their functionality (13). This exhaustion is defined by upregulation of PD-1 on the cell surface (14). More recently, PD-1 upregulation during acute infection has also been described (15). Blockade of PD-L1, one of two known ligands for PD-1, restores CD8+ T cell functionality and wholly improves the response to chronic lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV) infection. Little work has investigated the role of PD-1 during influenza virus infection. Increased expression of PD-1 on DbNP366-specific CD8+ T cells was briefly shown during acute infection, and cells expressing PD-1 exhibited impaired gamma interferon (IFN-γ) production and degranulation at day 14, but not at day 7, postinfection (15). This expression was reversed by anti-PD-L1 treatment. Another study used a self-antigen system to show that PD-1 was expressed early on hemagglutinin-specific CD8+ T cells, and blockade of PD-L1 at the time of self-antigen encounter led to development of functional CD8+ T cells (16). However, that work used strains of Listeria monocytogenes that expressed an epitope from the influenza virus hemagglutinin protein rather than actual influenza virus infection.

Some influenza A viruses are much more virulent than others, and apart from possible early effects of the cytokine storm, we do not fully understand why. To answer this question, we have compared the immune responses of mice after high- and low-pathological (high- and low-path) influenza virus infections. The airway microenvironment was more highly inflamed early during high-path infection. However, low-path infection induced a robust CD8+ T cell response characterized by significantly increased numbers of influenza virus-specific CD8+ T cells that exhibited greater functional activity and were more polyfunctional than those from mice with high-path infection. The attenuated CD8+ T cell response in high-path infection was associated with increased PD-1 expression, and in vivo blockade of PD-L1 improved CD8+ T cell numbers and decreased viral titers but failed to improve overall illness or rescue CD8+ T cell function. These data suggest that a dysregulated airway microenvironment may abrogate CD8+ T cell function and thus contribute to the phenotype of high-path influenza virus infection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice.

All mice were cared for under specific-pathogen-free conditions in an approved animal facility at St. Jude Children's Research Hospital (SJCRH). All animal work was reviewed and approved by the appropriate institutional animal care and use committee at SJCRH (protocol number 098) following guidelines established by the Institute of Laboratory Animal Resources and approved by the Governing Board of the U.S. National Research Council. Severe morbidity in infected animals was assessed daily using a body index score and humane euthanasia applied according to the standards of our approved protocol (greater than 30% weight loss combined with a threshold body index score indicating moribundity). Pathogen-free wild-type (WT) C57BL/6 female mice, B6.129S7-IFNgtm1Ts/J mice (IFN-γ deficient [IFN-γ−/−]), B6;129S-Tnftm1Gkl/J mice (tumor necrosis factor [TNF] deficient [TNF−/−]), and B6.129S2-Il6tm1Kopf/J mice (interleukin-6 deficient [IL-6−/−]) were purchased from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME). Experiments were performed with age-matched groups.

Viruses and infections.

All infections were performed with either A/Puerto Rico/8/34 (PR8) or A/HKx31 (x31). The x31 virus contains the six internal genes of PR8 but expresses H3N2 surface proteins, whereas PR8 expresses H1N1 surface proteins (17, 18). In one set of experiments, the high-path ΔVn1203 virus was used as a control for high-path PR8 infection. ΔVn1203 is a recombinant virus with the six internal PR8 genes and surface H5N1 proteins from A/Vietnam/1203/04, constructed using reverse genetics (19, 20). The polybasic cleavage site in the H5 was modified to restrict its cleavage to trypsin-like proteases. The N1 protein was unchanged. The ΔVn1203 virus was a gift from Richard J. Webby of SJCRH. Antibody against PD-1L (clone 10F.9G2; BioXCell) was administered intraperitoneally (i.p.) in 200-μg doses every other day, beginning the day before infection. Antibody against keyhole limpet hemocyanin (KLH) (clone LTF-2; BioXCell) was used as an isotype control. Antibody against granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) (clone 67604; R & D Systems) was administered i.p. in 200-μg doses at days 1, 3, and 5 after infection. Mice were chemically restrained with 2,2,2-tribromoethanol (avertin) prior to intranasal (i.n.) challenge with 104 50% egg infective doses (EID50) of either PR8 or x31 in one set of experiments. In other experiments, mice were infected with 103 EID50 of PR8 or 106 EID50 of x31. Illness was monitored by daily weighing after virus challenge.

Plaque assays.

Mice were sacrificed and lung tissue removed after collection of bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid. Lungs were then stored at −80°C prior to the assay. Monolayers of Madin-Darbin canine kidney (MDCK) cells in six-well plates were infected with serial dilutions of 1 ml of lung supernatants after homogenization. The infected monolayers were incubated for 1 h at 37°C and then washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). After washing, the cells were treated with 0.8% agarose in minimal essential medium (MEM) containing 1 mg/ml trypsin. The infected cells were incubated at 37°C for 72 h. Plates were then transferred to 4°C for at least 10 min, the agar was gently removed, and the monolayers were stained with crystal violet to visualize influenza virus plaques.

Synthetic peptides and tetramers.

All peptides were synthesized by the Hartwell Center at SJCRH. Peptides corresponding to influenza CD8+ T cell epitopes NP366-374 (ASNENMETM) (NP366), PA224-233 (SSLENFRAYV) (PA224), and PB1-F262-70 (SSLENFRAYV) (F262) are all H-2Db restricted. PB1703-711 (SSYRRPVGI) (PB1703) is H-2Kb restricted. The OVA257-264 peptide (SIINFEKL) (OVA257) is H-2Kb restricted and was used as a negative control in all experiments. Class I major histocompatibility complex (MHC) tetramers were constructed by combining H-2Db or H-2Kb with the aforementioned immunogenic peptides. Tetramer staining was done as described previously (21).

Flow cytometry and intracellular cytokine staining (ICS).

Mice were sacrificed and BAL fluid, mesenteric lymph nodes (MLN), and spleens harvested after challenge. MLN and spleens were manually disrupted by grinding organ tissue between the frosted ends of two sterile glass microscope slides in sterile PBS containing 2% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (2% PBS). Red cell lysis was performed for spleen cells. Cells were then stained with allophycocyanin (APC)- or phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated influenza virus tetramers for 1 h at room temperature. After washing, cells were stained with fluorescently labeled antibodies against CD8α (clone 53-6.7), CD4 (clone GK1.5), CD27 (clone LG.3A10), the activated isoform of CD43 (clone 1B11), PD-1 (clone J43), PD-1L (clone 10F.9G2), Tim-3 (clone 215008; R&D Systems), PD-L2 (clone TY25), CD45 (clone 104), MHC class II (clone 2G9), CTLA-4 (clone UC10-4B9), and unlabeled anti-CD16/CD32 (clone 2.4G2) to block nonspecific Fc receptor-mediated binding. CD8+ T cells were distinguished from antigen-presenting cell populations by using antibodies against CD45R/B220 (clone RA3-6B2), F4/80 (clone CI:A3-1), CD11b (clone M1/70), and CD11c (clone N418).

For ICS, lymphocytes were cultured in 96-well round bottom plates for 5 h at 37°C in 200 μl RPMI containing 10% FCS (10% RPMI). To promote antiviral cytokine production, the cells were also supplemented with 1 μM NP366 and PA224 peptides, brefeldin A, and anti-CD28 antibody for costimulation. Positive controls were stimulated with 1 μg/ml of phorbol myristate acetate (PMA) and ionomycin instead of influenza virus peptides. After in vitro stimulation, the cells were washed, fixed, and permeabilized according to the manufacturer's protocol (BD PharMingen Cytofix/Cytoperm kit). Cells were then stained with the antibodies listed above and TNF (clone MP6-XT22), IFN-γ (clone XMG1.2), and CD107a/b (clones 1D4B and ABL-93, respectively). After staining, cells were resuspended in 2% PBS plus azide and detected using an LSRII flow cytometer (BD Biosciences). Data were analyzed using FlowJo software (Tree Star, San Carlos, CA). Antibodies were purchased from BioLegend, BD PharMingen, and Life Technologies.

Surface staining was performed as described previously. For bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) staining, the BrdU kit from BD PharMingen was used according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, x31 and PR8 (104 EID50)-infected mice received i.p. injection of BrdU (1 mg/mouse) at 14 to 15 h before termination of mice. BAL fluid, draining MLN, and spleen cells were stained first with PA and NP tetramers and then with anti-CD8 and subsequently were labeled with anti-BrdU monoclonal antibody (MAb). Samples were acquired on LSRII flow cytometer (BD Biosciences). Data were analyzed using FlowJo software (Tree Star, San Carlos, CA).

Detection of antiviral cytokine production.

Cytokine and chemokine production in the BAL fluid supernatants of infected mice was quantified using Milliplex MAP kits in 96-well assays from Millipore (Mouse Panel I). Plates were analyzed on a Bio-Rad Bioplex HTF system using Luminex xMAP technology to measure the levels of 32 different cytokines and chemokines included in the panel. Additional cytokine production was measured in commercially available enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits (R&D Systems).

In vitro activation.

Spleens were harvested from naive WT C57BL/6 mice, and CD8+ T cells were isolated by magnetic bead separation (Miltenyi Biotech). CD8+ T cells were cultured in 96-well plates that were precoated with 4 μg/ml anti-mouse CD3 (clone 17A2, BioLegend). All cells were incubated for 72 h at 37°C in 10% RPMI medium supplemented with 1 μg/ml anti-mouse CD28 (BD PharMingen) and 1 μg/ml recombinant human IL-2 (rhIL-2) (R&D Systems). Cells were coincubated in triplicate wells with 5 ng/ml recombinant murine IL-6, recombinant murine G-CSF (both from Peprotech), or both cytokines together. Control wells had no cytokine added. After 72 h, cells were washed and incubated with brefeldin A for an additional 4 h prior to treatment for ICS, as described above. Activation was confirmed by flow cytometry after cells were stained for surface CD27 and CD43 expression and also intracellular production of IFN-γ.

Statistical analysis.

The Student t test or the Mann-Whitney test for unpaired, nonparametric analysis was used to assess statistical significance in all experiments. Cox proportional hazards survival regression was used to assess statistical significance in survival experiments. P values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Clinical profiles of high- and low-path influenza A virus infections.

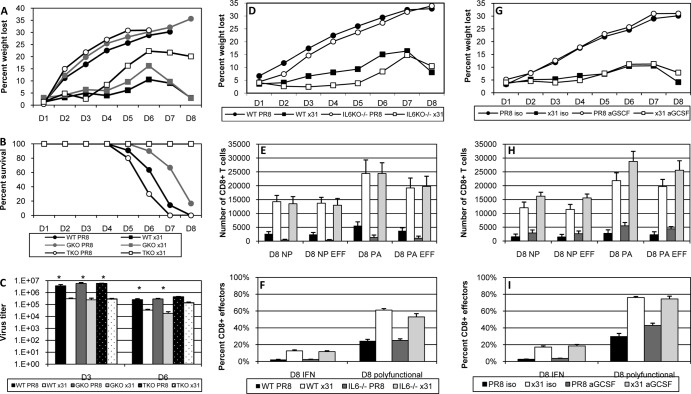

PR8 is a mouse-adapted H1N1 influenza virus that is known to cause severe infection in mice. In contrast, x31 is an H3N2 influenza virus that causes mild to moderate illness in mice, despite containing the six internal genes of PR8. Mice were infected with 104 EID50 of PR8 or x31 and were assessed for illness and mortality. The 104-EID50 dose is slightly higher than the 50% minimal lethal dose (MLD50) for PR8. As a control for high-path PR8 infection, a third group of mice was infected with 104 EID50 of ΔVn1203, a genetically modified H5N1 virus known to cause terrible illness in humans as well as mice (22). As expected, mice that were infected with PR8 or ΔVn1203 exhibited severe illness that also manifested very early after infection (Fig. 1A). In contrast, x31-infected mice displayed a very mild illness profile. Differences in survival were equally dramatic, with nearly 80% of PR8-infected mice succumbing to infection by day 9, compared to complete survival of the x31-infected group in all experiments (Fig. 1B). All mice infected with ΔVn1203 were dead by day 7. Viral titers were similar in all three groups through day 6, though titers in the lungs of x31-infected mice were slightly reduced (Fig. 1C). At day 8, virus could no longer be detected in the lungs of x31-infected mice, whereas titers were still measurably high in the PR8-infected mice that had managed to survive the infection to that point. All ΔVn1203-infected mice had succumbed prior to day 8. These data demonstrate that PR8 and x31 can be used to compare high- and low-path influenza virus infections, and the disparities in the clinical outcomes cannot be sufficiently explained by differences in early viral replication in the lungs.

FIG 1.

Clinical profiles of high- and low-path influenza A virus infection. Mice were infected i.n. with 104 EID50 of the PR8, x31, or ΔVn1203 influenza A virus, and illness (A), survival (B), and virus titers (C) were measured at intervals. Panels A and C show results from a representative of five experiments (n = 4 or 5 mice per group). Panel B shows survival from four combined experiments using between 20 (ΔVn1203) and 55 total mice per group. *, P < 0.05 for comparisons between PR8 and x31 at days 2, 4, and 8 and between x31 and ΔVn1203 on day 2.

The composition of the airway microenvironment trends toward increased inflammation in high-path influenza A virus infection.

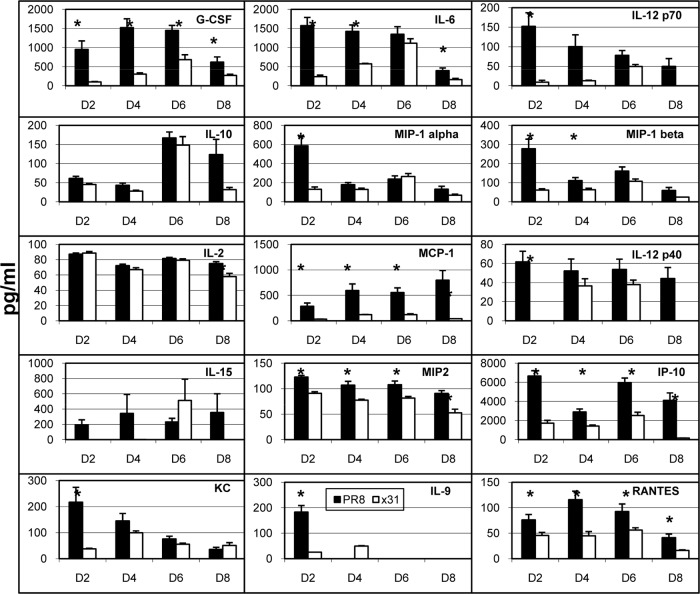

High-path influenza A virus infections are often defined by an overeffulgent cytokine storm (6–8). Because we observed severe illness only in mice infected with PR8, we asked whether hypercytokinemia was contributing to high-path PR8 infection. We investigated cytokine and chemokine levels using multiplex bead assays on supernatants from BAL fluid taken on days 2 through 8 postinfection to obtain a broad snapshot of the airway microenvironment after infection. Overall there was a trend toward increased cytokine levels in the BAL fluid during high-path infection, especially at early time points (Fig. 2). While some of the cytokines typically associated with the cytokine storm were also upregulated in our experiments, some were not, while others were not consistently elevated across multiple experiments. In this study, IL-6 and G-CSF showed the most robust and consistent responses across multiple experiments. G-CSF is not a member of the IL-6 superfamily, but the complex formed by G-CSF and its receptor is similar to that of IL-6, IL-6Rα, and gp130 (23). These data demonstrate that the airway microenvironment is more inflammatory in high-path PR8 infection, although not as inflammatory as the level generally associated with hypercytokinemia reported in other high-path influenza virus studies.

FIG 2.

Cytokine and chemokine production in the airway microenvironment after influenza virus infection. Mice were infected as described for Fig. 1. At days 2, 4, 6, and 8 after infection, BAL fluid wash supernatants were collected and analyzed by multiplex cytokine bead analysis. The data set shows cytokines and chemokines that were consistently measured above the limit of detection across multiple experiments. The data show results from a representative experiment of five with 4 or 5 mice per group. *, P < 0.05 for comparisons between PR8 and x31 at each time point.

Low-path infection is associated with a more stout CD8+ T cell response.

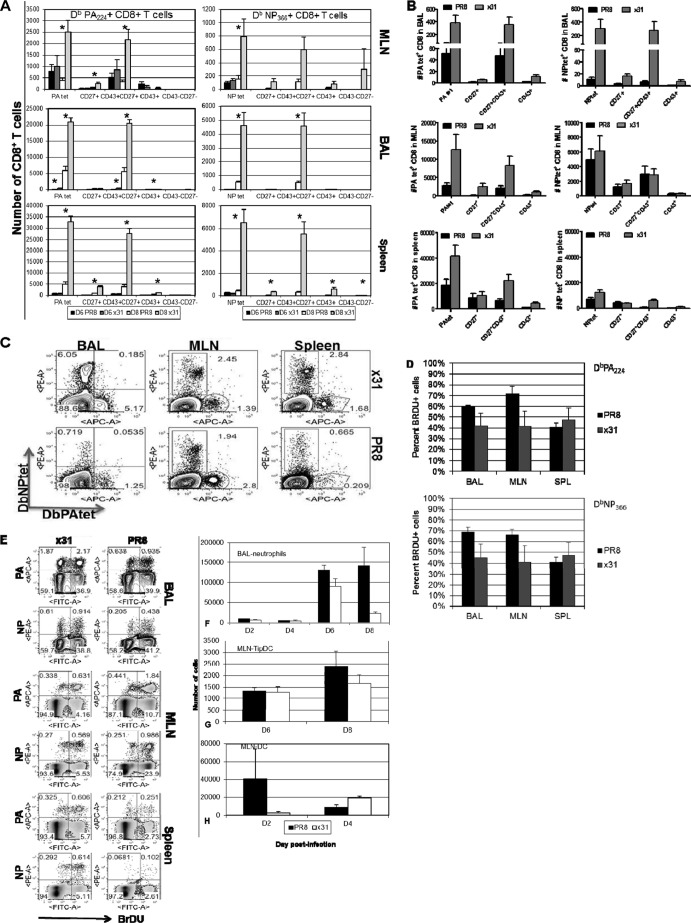

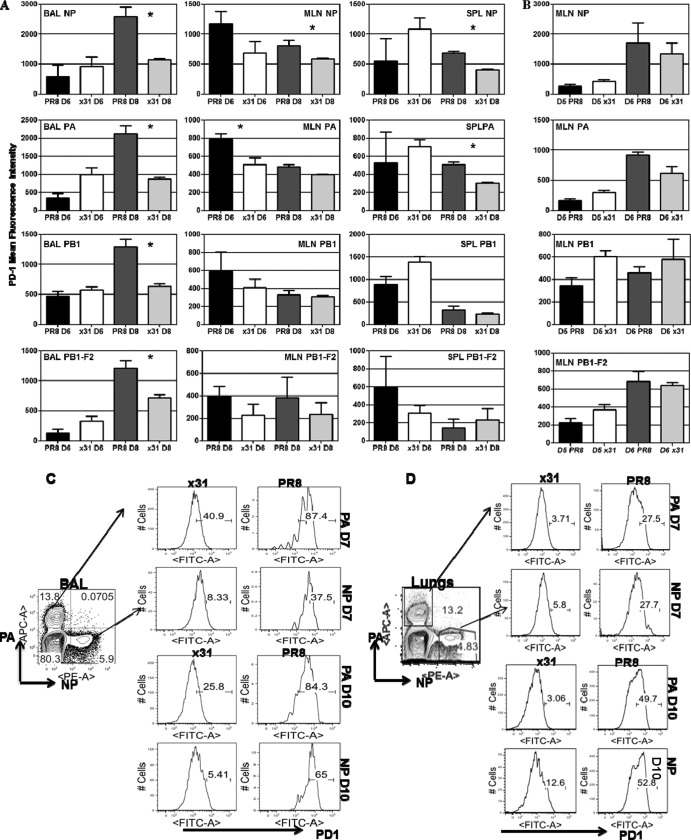

Since an innate inflammatory milieu can influence adaptive immunity, we asked if there were differences in the CD8+ T cell responses to PR8 and x31 infections. Using tetramer staining to enumerate influenza virus-specific CD8+ T cells at days 6 and 8 postinfection, we found that mice infected with x31 had significantly increased numbers of PA224- and NP366-specific CD8+ T cells in the BAL fluid at day 8 postinfection, and this was true in all experiments (Fig. 3A). Differences were not significant at day 6, and numbers were also much lower, which is expected since the peak of the CD8+ T cell response in the lung and airways does not begin until days 8 to 10 following influenza virus infection. However, because of the extensive mortality in PR8-infected mice, we could not examine the response beyond day 8. To ensure that the differences seen at day 8 were not biased by the fact that we could only analyze mice that had survived PR8 infection to that point, we also examined the T cell response at day 7 (Fig. 3B and C). Here again we observed a significant increase in the number of tetramer-positive CD8+ T cells in low-path x31-infected mice compared to high-path PR8-infected mice. These same trends were also recognized in the MLN and spleen at days 6, 7, and 8; however, differences were not as profound or significant, suggesting that the local lung airway microenvironment may be the cause of the reduced response during PR8 infection. Additional experiments showed that tetramer-positive CD8+ T cells were incorporating BrdU at similar levels at day 7 during high- and low-path infections (Fig. 3D and E), indicating that there is no difference in proliferation between the two groups. From these data, we conclude that influenza virus-specific CD8+ T cells are profoundly and significantly increased in low-path infections.

FIG 3.

Influenza virus-specific effector CD8+ T cells are more numerous in low-path infection. (A and B) Mice were infected as for Fig. 1, and tetramer staining was used to enumerate influenza virus-specific DbPA224+ and DbNP366+ CD8+ T cells in the BAL fluid, MLN, and spleen at days 6 and 8 postinfection (A), as well as at day 7 (B). After gating on tetramer-positive cells, expression of CD27 and CD43 was examined, and each subpopulation is shown to the right of the tetramer-positive bars. (C) Representative dot plots of the data from panel B. (D) Proliferation of DbPA224+ and DbNP366+ CD8+ T cells in the BAL fluid, MLN, and spleen at day 7 was measured by incorporation of BrdU. (E) Representative dot plots for panel D. (F) Neutrophils were isolated by gating on CD11b+ CD11c− cells and then counting MHCII− GR1+ cells. (G) TipDCs were identified as MCHII+ GR1high cells. (H) Classical DCs in the MLN were identified by gating on CD11b+ CD11c− cells and then counting MHCII+ GR1− cells. The data are from a single representative of more than five experiments with 4 or 5 mice per group. *, P < 0.05.

Given the disparity in the numbers of tetramer-positive cells at day 8, we next compared cell surface phenotypes that reflect CD8+ T cell differentiation states. Recent studies have highlighted the distinction of short-lived effector cells (SLEC) (KLRG1high CD127lo) from memory precursor effector cells (MPEC) (KLRG1lo CD127 high) in LCMV and Listeria infections (24–26). However, other research groups, including ours, have found that the KLRG1/CD127 divergence does not comfortably translate to all models, including influenza A virus infection (3, 27). It therefore appears that the MPEC/SLEC classification system may not be feasible in the C57BL/6 murine influenza virus infection model. For this reason, we investigated CD8+ T cell activation phenotypes based on CD27 and CD43 expression. This classification scheme has been informative in Sendai virus infections and has also been extended to CD8+ T cell memory in influenza virus infections (28, 29). We found that the majority of influenza virus-specific CD8+ T cells expressed the CD27+ CD43+ effector phenotype (Fig. 3A to C). This was true for both DbPA224- and DbNP366-specific CD8+ T cells in the BAL fluid, MLN, and spleen at days 7 and 8 postinfection in all experiments. At day 6, numbers were much lower and differences between PR8 and x31 were small. Not surprisingly, we did not see high numbers of memory precursors (CD27+ CD43−) in the BAL fluid at any time point, and other subpopulations had extremely low numbers as well. These data show that almost all of the tetramer-positive cells fell within the effector subpopulation in the BAL fluid, MLN, and spleen. Although numbers of influenza virus-specific CD8+ T cells differ significantly in high- and low-path infections, the differentiation of the cells determined by this surface phenotype schema is unaffected.

Interestingly, we did not notice increased recruitment of cells associated with the innate response, despite the increased inflammation that was presented in Fig. 2. G-CSF is a known chemoattractant for neutrophils (30), but we saw no difference in neutrophil numbers until day 8 (Fig. 3F). Cells infected with influenza virus are also known to produce proinflammatory cytokines such as MCP-1/CCL-2 (31). CCL-2 recruits dendritic cell (DC) populations to sites of inflammation, but under these specific experimental conditions, we did not see significantly elevated TNF/inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS)-producing DC (TipDC) or DC numbers early in the MLN of PR8-infected animals (Fig. 3G and H). Overall, though the numbers of influenza virus epitope-specific CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) differ substantially for high-path and low-path infections, the distributions of the various CD27/CD43 phenotypes within those sets are essentially comparable.

CD8+ T cells are more activated and polyfunctional in mice after low-path infection.

Influenza virus-specific CD8+ T cell numbers were significantly elevated during low-path infection with x31. We followed this observation by evaluating the effector activity of influenza virus-specific CD8+ T cells after infection. Cells were isolated from the indicated organs and stimulated in vitro with PA224 and NP366 together prior to intracellular cytokine staining. Because CD8+ T cells do not become activated and infiltrate the airway microenvironment very early after infection, we limited our analysis of intracellular cytokine production to days 6 and 8 postinfection.

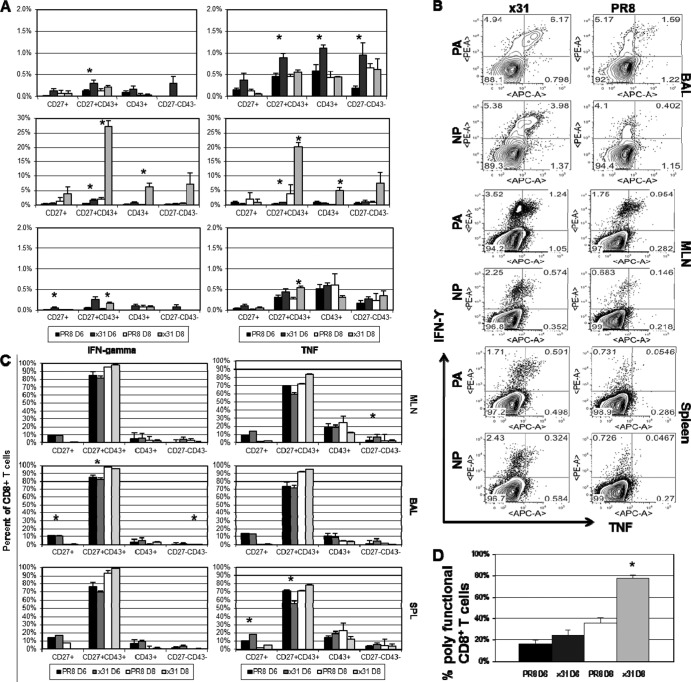

We began by determining the magnitude of functionality within each subpopulation. Each CD27/CD43 subpopulation was examined after gating on CD8+ T cells. We then calculated the percentage of cells that were producing cytokine within each subpopulation. At day 8, effector CD8+ T cells isolated from the BAL fluid of x31-infected mice exhibited impressively robust and significant increases in IFN-γ and TNF production compared to those from PR8-infected mice (Fig. 4A). We also observed increased cytokine production by effectors at day 6, but levels were much lower than at day 8. Again, to ensure that the disparity in CD8+ T cell effector function at day 8 was not a result of being able to analyze only mice that had survived PR8 infection to that point, we also examined the T cell response at day 7 (Fig. 4B). As expected, CD8+ T cells isolated from mice with high-path infection were strikingly and significantly depressed in their ability to produce antiviral cytokines compared to CD8+ T cells isolated from mice with low-path infection. CD8+ T cells isolated from the MLN after x31 infection also showed elevated antiviral cytokine production at days 6, 7, and 8 compared to CD8+ T cells from PR8-infected mice. These trends were also present in other CD27/CD43 subpopulations but at greatly reduced magnitudes. The overwhelming majority of cytokine-producing CD8+ T cells were CD27+ CD43+ effectors at days 6 and 8 postinfection in all three organs (Fig. 4C). Additionally, there was essentially no difference between low- and high-path infection, demonstrating that the responding cells in high-path infection were not part of an aberrant subpopulation but were normally differentiated effectors. These results suggest that effector function appears to be somewhat divorced from surface phenotype classifications.

FIG 4.

Activated influenza virus-specific CD8+ T cells are almost uniformly CD27+ CD43+ effectors. (A) Peptide-induced cytokine production profiles for the different IFN-γ+ and/or TNF+ CD27/CD43 subsets shown in Fig. 3. Cells were first gated on CD27/CD43 subsets, and the proportion making IFN-γ or TNF was calculated. (B) Representative dot plots of antiviral cytokine production by DbPA224+ and DbNP366+ CD8+ T cells at day 7 postinfection are shown to confirm that the responses seen at day 8 are under way at day 7. These plots are from the same experiments shown in Fig. 3D and E. (C) Cells isolated from the mice sampled for Fig. 3 were assayed for IFN-γ and TNF production by ICS. Cells were analyzed by gating first on the cytokine-positive CD8+ sets followed by CD27 and CD43 staining. (D) The percentage of CD8+ IFN-γ+ TNF+ cells was then divided by the percentage of CD8+ IFN-γ+ cells to give the percentage of polyfunctional (IFN-γ+ TNF+) cells within the IFN-γ+ set. The data show results from a representative experiment of five with 4 or 5 mice per group. *, P < 0.05.

It was next important to ask whether CD8+ T cells from x31-infected mice displayed greater polyfunctionality than CD8+ T cells from PR8-infected mice. It has been shown that during influenza virus infection, CD8+ T cells begin producing IFN-γ upon activation, followed by TNF production as they become more activated and thus polyfunctional (32). We therefore calculated the percentage of IFN-γ+ CD8+ effector T cells that also produced TNF to determine polyfunctionality in the BAL fluid. At day 6, there was a slight increase in the percentage of IFN-γ+ CD8+ T cells producing TNF in the x31-infected mice (Fig. 4D), yet by day 8, this difference became dramatic and significant, with nearly 80% of the IFN-γ+ CD8+ T cells also producing TNF, compared to only 35% in PR8-infected mice. These data show that CD8+ T cells in low-path infection are more polyfunctional and thus are more highly activated than their counterparts in high-path infection. Moreover, cytokine production by the CD8+ T cell effector population is much more efficient during infection with x31, and these CD8+ T cells also produce more cytokines per cell than their PR8 counterparts, suggesting that x31 infection is defined by an incredibly robust yet efficient CD8+ T cell response that leads to a low-path infection.

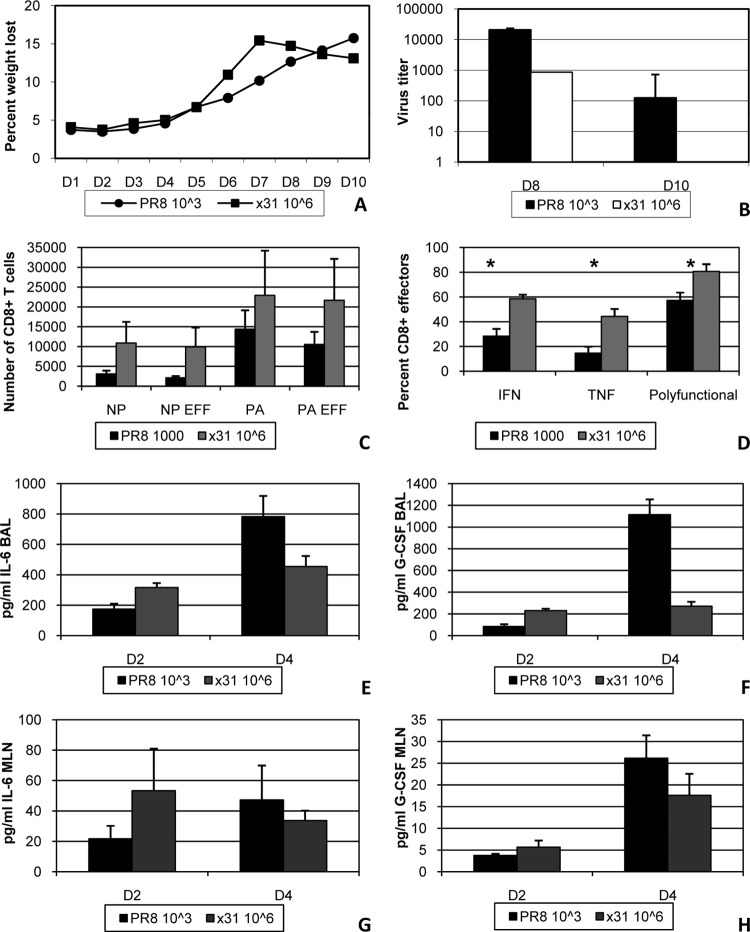

The previous experiments showed that high-path infection was accompanied by reduced numbers of activated, antigen-specific CD8+ T cells, which were also defined by reduced effector activity and polyfunctionality. In additional experiments, we changed the infectious doses so that illness would be similar in both groups. This was accomplished by infecting two groups of mice with 103 EID50 PR8 or 106 EID50 x31 (Fig. 5A). Importantly, all of our assays revealed the same trends in these experiments that we observed in our comparisons with 104 EID50. Virus titers were again slightly reduced in x31-infected mice, confirming that virus titer was not the sole factor in determining the severity of influenza virus-associated illness (Fig. 5B). At day 8, increased numbers of DbPA224- and DbNP366-specific CD8+ T cells were seen in the BAL fluid during x31 infection, and nearly all of these cells were CD27+ CD43+ effectors (Fig. 5C). In addition, CD8+ T cells from the BAL fluid of x31-infected mice produced significantly more cytokine and were more polyfunctional by ICS (Fig. 5D). When we repeated our multiplex cytokine bead analysis, we again found elevated levels of IL-6 and G-CSF in the airway microenvironment of PR8-infected mice at day 4 (Fig. 5E and F). Cytokine levels were roughly equivalent in the MLN at the same time point (Fig. 5G and H). Together, these results clearly show that x31 infection is defined by an incredibly robust yet efficient CD8+ T cell response, regardless of the input virus dose.

FIG 5.

Equalizing the illness outcome does not alter the CD8+ T cell response to high- and low-path influenza virus infection. (A to D) Mice were infected i.n. with 103 EID50 of PR8 or 106 EID50 of x31 to monitor illness by daily weight change (A) and viral titer (B) and for the analysis of BAL fluid populations taken on day 8 for tetramer-positive CD8+ CTL numbers (C) and functional activation (D). EFF, tetramer-positive CD27+ CD43+. (E to H) Multiplex cytokine bead analysis was used to assess the concentrations of IL-6 and G-CSF in supernatants from the BAL fluid (E and F) and MLN (G and H) at days 2 and 4 postinfection. The data are from a representative experiment of three with 4 or 5 mice per group. *, P < 0.05.

Individual cytokines and the CD8+ T cell response.

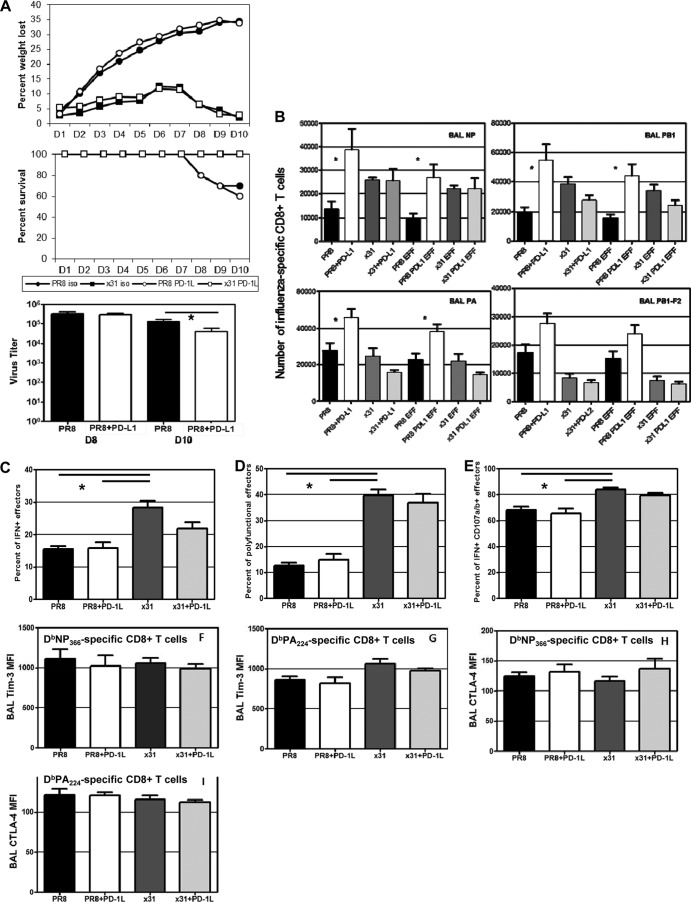

The augmented CD8+ T cell polyfunctionality we saw in x31-infected mice led us to ask if we could reduce the disparity in pathology of PR8 and x31 infections in the absence of IFN-γ or TNF. IFN-γ−/− and TNF−/− mice were thus infected with 104 EID50 of either PR8 or x31 and then monitored for illness and survival. Illness profiles for IFN-γ−/− and TNF−/− mice were similar to those for WT controls for both PR8 and x31 infections (Fig. 6A). Interestingly, illness was slightly augmented in x31-infected TNF−/− mice, suggesting a protective role for TNF in response to x31 infection. However, the increased illness did not correlate with a change in mortality, as all x31-infected groups presented with 100% survival (Fig. 6B). On the other hand, extreme mortality defined all groups infected with PR8. There were slight differences in the kinetics of PR8-induced mortality when comparing WT PR8 infection to infection of IFN-γ−/− and TNF−/− mice with PR8, and the differential kinetics of survival between IFN-γ−/− and TNF−/− mice was significant after PR8 infection. Viral titers in IFN-γ−/− and TNF−/− mice also followed the pattern seen in WT mice (Fig. 6C), again indicating that early differences in viral replication were insufficient to explain the disparities in morbidity and mortality. It therefore appears that the quality and efficiency of the response differs in the two infections and is the result of differential regulation of the development of CD8+ T cells by the early responses to PR8 and x31.

FIG 6.

High- and low-path infection in IFN-γ−/−, TNF−/−, IL-6−/−, and anti-G-CSF-treated mice. (A to C) WT B6, IFN-γ−/−, and TNF−/− mice were infected i.n. with 104 EID50 of PR8 or x31 to determine illness (A), survival (B), and lung virus titers (C) on days 3 and 6. (D to F) WT B6 or IL-6−/− mice were infected i.n. with 104 EID50 of PR8 or x31. (G to I) In separate experiments, WT B6 mice were treated with 200 μg anti-G-CSF antibody or isotype control on days 1, 3, and 5. (D and G) Mice were weighed daily to monitor illness. (E and H) Tetramer-positive CD8+ CTLs were enumerated on day 8, and the numbers of influenza virus-specific CD27+ CD43+ effector CD8+ T cells were also calculated. (F and I) ICS was used to measure the percentage of CD27 CD43+ effector CD8+ T cells that were producing IFN-γ and also to measure polyfunctionality. The data show results from a representative experiment of three (A to F) or two (G to I) with 4 or 5 mice per group. *, P < 0.05 for all comparisons between PR8-infected groups and their x31-infected counterparts in panels E, F, H, and I.

Next, we investigated the roles of IL-6 and G-CSF, as these two cytokines were consistently elevated in our multiplex analyses (Fig. 2). Illness was not dramatically altered in IL-6−/− mice after infection, although there was a slight improvement that was more obvious in x31-infected IL-6−/− mice (Fig. 6D). In addition, survival was not consistent across three independent experiments, only one of which was significant by Cox proportional hazards survival regression analysis. As always, no x31-infected mice succumbed to infection. Cellular analysis showed that there was still a disparity in CD8+ T cell effector numbers between x31- and PR8-infected mice in the BAL fluid of IL-6−/− mice at day 8 (Fig. 6E). As with WT mice, CD8+ effector T cells from the BAL fluid of IL-6−/− mice exhibited increased cytokine production and polyfunctionality after low-path infection (Fig. 6F). In our experiments, functionality was always significantly impaired in high-path infection, but the disparity between high- and low-path infections was not always as severe in IL-6−/− mice as in WT mice. While these results suggest a role for the pleiotropic IL-6 during influenza virus infection, they do not demonstrate that IL-6 alone is responsible for the high-path phenotype of PR8 infection.

We also attempted to elucidate the role of G-CSF in vivo during high- and low-path influenza virus infection. We used a purified neutralizing antibody against mouse G-CSF to deplete the cytokine at days 1, 3, and 5 postinfection. Pilot studies showed that administration of this antibody depleted G-CSF levels in the BAL fluid of a PR8-infected mouse by approximately half (data not shown). In subsequent experiments, depletion of G-CSF did not affect the illness profiles after high- and low-path infection (Fig. 6G). On the other hand, our cellular assays revealed that anti-G-CSF treatment did show signs of improving the CD8+ T cell response during high-path infection, although the responses still did not begin to approach the levels seen in low-path x31-infected mice (Fig. 6H and I).

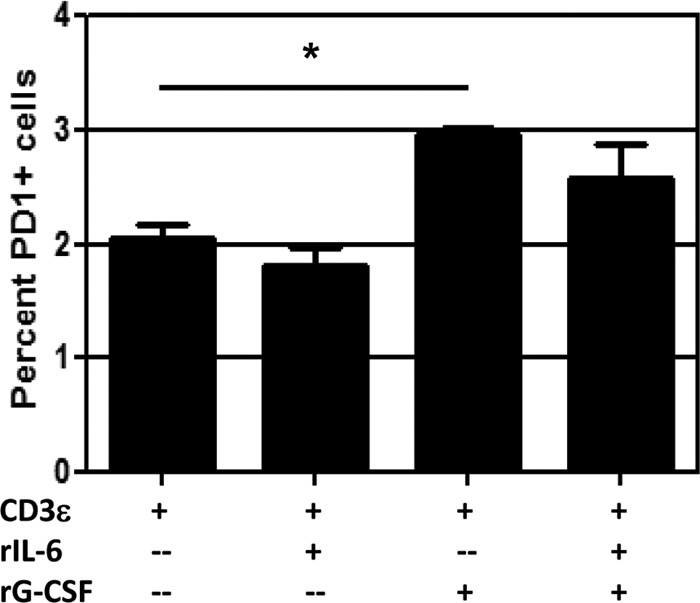

These experiments suggested a possible role for IL-6 and G-CSF in influenza virus pathogenesis. Of course, both cytokines are pleiotropic, and other factors can potentially compensate for their absence. We therefore performed a small in vitro experiment to isolate the potential effects of IL-6 and G-CSF on the CD8+ T cell response. CD8+ T cells from the spleens of naive WT mice were stimulated by plate-bound anti-mouse CD3 as well as anti-CD28 antibody for 72 h in the presence of 5 ng/ml recombinant IL-6, G-CSF, or both. Activation was confirmed by CD27+ CD43+ coexpression and intracellular staining for IFN-γ, and other markers associated with CD8+ T cell function were examined. Our data revealed that treatment with recombinant G-CSF led to significant upregulation of the activation marker PD-1 (Fig. 7). PD-1 expression was not affected by the addition of IL-6 to the culture during stimulation, nor did IL-6 affect the ability of G-CSF to induce PD-1 expression. Two other markers associated with CD8+ T cell activation, Tim-3 and CTLA-4, were unchanged by the presence of IL-6 and G-CSF in vitro (data not shown). Although the differences are small, they are significant and were consistently observed across five experiments, suggesting that G-CSF may specifically influence PD-1 expression and thus affect CD8+ T cell function.

FIG 7.

G-CSF induces PD-1 expression on activated CD8+ T cells in vitro. CD8+ T cells were isolated from spleens of naive WT mice and cultured in 96-well plates precoated with 4 μg/ml anti-mouse CD3 and 1 μg/ml anti-mouse CD28 and rhIL-2. Triplicate wells were supplemented with 5 ng/ml recombinant mouse IL-6 or G-CSF as indicated. After 72 h, cells were treated with brefeldin A for 4 h, followed by intracellular cytokine staining for IFN-γ to confirm that cells had been activated (not shown). Surface staining for PD-1 is shown. The data are from a single representative of more than five experiments. *, = P < 0.05 for comparison between CD3ε alone and CD3ε plus rG-CSF.

CD8+ T cells upregulate PD-1 expression in vivo during high-path infection.

Our previous data revealed the possibility that PD-1 expression may be linked to the debilitated CD8+ T cell response during high-path infection. We revisited our 104 EID50 infection model and found significantly increased PD-1 staining by mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) on CD8+ T cells in the BAL fluid of PR8-infected mice at day 8 compared to cells isolated from x31-infected mice (Fig. 8A). This was true for CD8+ T cells specific for all 4 major class I MHC epitopes, indicating that PD-1 expression was not restricted to a subset of influenza virus-specific cells. Furthermore, PD-1 expression was not increased in the BAL fluid at day 6, although there was a trend toward elevated PD-1 staining on high-path CD8+ T cells in the MLN at day 6. Additional experiments that included day 5 showed that this staining was not present at early time points in the MLN (Fig. 8B), indicating that PD-1 upregulation was not originating prior to migration into the airway. Further analysis of PD-1 expression at day 7 showed that PD-1 expression in the BAL fluid was significantly increased on DbPA224- and DbNP366-specific CD8+ T cells after high-path infection (Fig. 8C). Furthermore, this discrepancy was even more pronounced in the lung tissue (Fig. 8D). These data unambiguously demonstrate that PD-1 expression is significantly increased on influenza virus-specific CD8+ T cells during high-path infection.

FIG 8.

PD-1 expression is upregulated on effector CD8+ T cells in the BAL fluid after high-path infection. Mice were infected as described for Fig. 1. (A) At days 6 and 8 postinfection, cells isolated from the BAL fluid, MLN, and spleen were assessed by flow cytometry. Influenza virus-specific CD8+ T cells were identified by tetramer staining for all 4 epitopes recognized during primary infection. PD-1 expression on tetramer-positive/CD8+ T cells was measured by mean fluorescence intensity. (B) PD-1 expression in the MLN at days 5 and 6 in a separate experiment to assess the likelihood of exhaustion occurring in the MLN before CD8+ T cells migrated into the airway. (C and D) Representative dot plots and histograms illustrating the percentages of DbPA224+ and DbNP366+ CD8+ T cells that express PD-1 at days 7 and 10 in the BAL fluid (C) and lung (D). The data are a single representative of more than five experiments with 4 or 5 mice per group. *, P < 0.05.

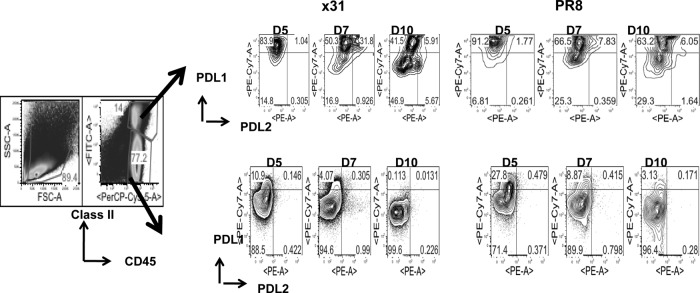

PD-1 has two known ligands, PD-L1 and PD-L2. We repeated our 104 EID50 comparison and looked at expression of PD-L1 and PD-L2 on target cells in the airway (i.e., BAL fluid). It has been shown in situ that CD45+ CD11c+ DCs that infiltrated the lungs stimulated CD8+ T cell cytolytic activity and cytokine release, but CD45− respiratory epithelium stimulated only cytolytic activity (12). Our data show that in mice infected with 104 EID50 of PR8, PD-L1 expression on MHCII+ CD45+ cells is elevated throughout the infection compared to that in x31-infected mice (Fig. 9). PD-L1 expression is also elevated on CD45+ MHCII− cells during infection with 104 EID50 of PR8. Interestingly, we found that at day 7, coexpression of PD-L1 and PD-L2 on MHCII+ CD45+ cells was spectacularly increased in x31-infected mice compared to PR8-infected mice. However, CD45+/MHCII− cells expressed significantly higher PD-L1 levels in the BAL fluid (Fig. 9) at almost all the time points tested after PR8 infection.

FIG 9.

PD-L1 expression is upregulated on target cells during high-path infection. Mice were infected with 104 EID50 of PR8 or x31 and sacrificed at days 5, 7, and 10 to assess expression of PD-L1 and PD-L2 on cells targeted by CD8+ T cells in the BAL fluid. Target cells were defined by expression of class II MHC, and CD45.2 PD-L1 and PD-L2 expression was examined after gating on CD45+ class II MHC+ and CD45+ class II MHC− cells. The data show dot plots from a representative experiment of two with 4 or 5 mice per group.

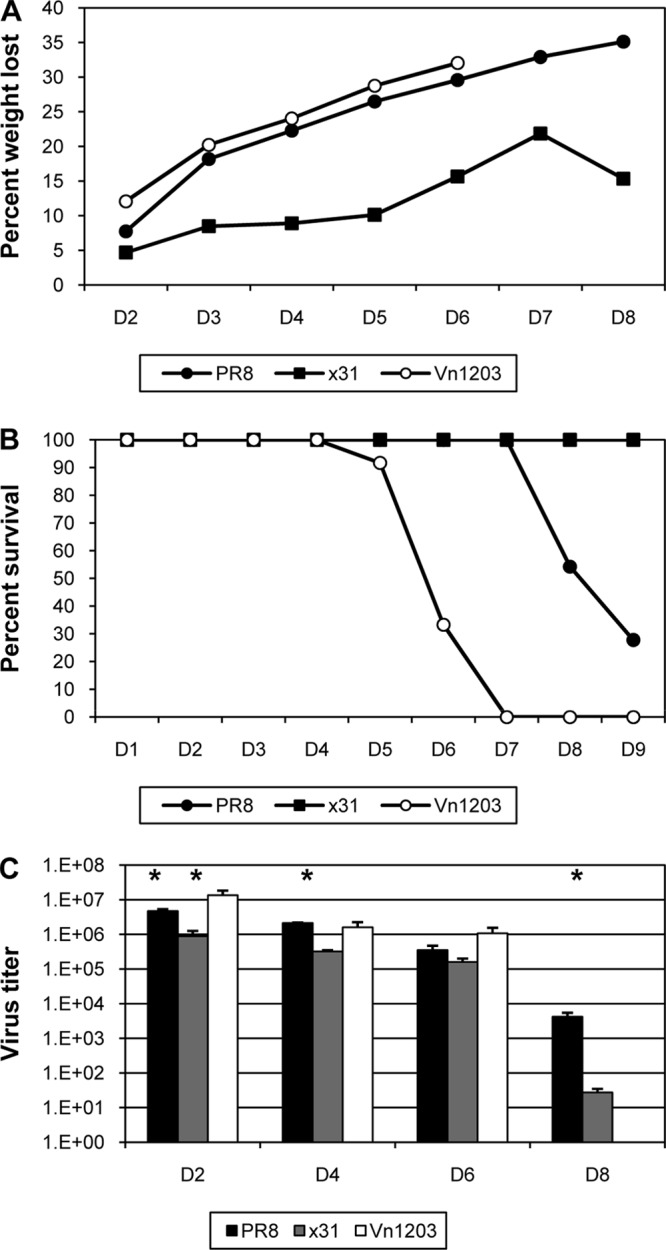

To see if we could rescue the high-path phenotype and correlate PD-1 with reduced CD8+ T cell function, we treated mice with antibody against PD-L1 during infection to block the PD-1/PD-1L interaction. Treatment with anti-PD-L1 antibody alone has been shown to rescue PD-1-induced exhaustion (14). Our data revealed that anti-PD-L1 treatment had no effect on illness or survival in three separate experiments (Fig. 10A). However, anti-PD-L1 treatment did lead to a significant reduction in virus titers at day 10 in mice with high-path infection (P = 0.043). In this case, titers in x31-infected mice had already fallen below the level of detection by day 8. Analysis of the CD8+ T cell response showed that influenza virus-specific CD8+ T cell numbers were significantly increased in anti-PD-L1-treated mice with high-path infection at day 8 postinfection compared to isotype control-treated mice (Fig. 10B). This general trend was repeated in three separate experiments, although with a slight delay in one experiment. It was notable that anti-PD-L1 treatment had minimal effect on CD8+ T cell numbers during x31 infection and that CD8+ T cell functionality was still diminished in mice with high-path infection after anti-PD-L1 treatment (Fig. 10C to E). The percentage of CD8+ T cells producing cytokine was unchanged after anti-PD-L1 treatment in both infections. We also expanded upon our assessment of polyfunctionality by examining the percentage of IFN-γ+ CD8+ effectors that also stained positive for the degranulation markers CD107a/b, and we saw no changes with anti-PD-L1 treatment (Fig. 10E). When we looked at other phenotypic markers that have been associated with diminished CD8+ T cell activity, we saw no significant differences between any groups, suggesting that our experimental outcomes are restricted to effects mediated by PD-1 (Fig. 10F to I). These data clearly demonstrate that upregulation of PD-1 during high-path infection correlates with reduced CD8+ T cell numbers and activity. However, blockade of PD-L1 led to recovery of CD8+ T cell numbers and reduced viral titers, indicating that although functionality was not rescued during high-path infection, the increased numbers did lead to better control of the infection. In summary, blocking the PD-1/PD-L1 interaction increases the numbers of epitope-specific CD8+ CTLs that can be recovered from the respiratory tract in high-path versus low-path influenza A virus infection, but this has no effect either on the diminished cytokine response profile for individual responding CD8+ T cells or on the overall severity of the disease process.

FIG 10.

Administration of anti-PD-L1 rescues CD8+ T cell numbers but not functionality or illness. Mice infected i.n. with a dose of 104 EID50 of PR8 or x31 were treated with 200 μg anti-PD-L1 antibody or isotype control antibody starting the day before infection and continuing every other day thereafter. (A) Illness and survival were assessed daily. Viral titers were measured by plaque assay at the indicated days. (B) Tetramer-positive CD8+ T cells in the BAL fluid at day 8 postinfection (left graphs). After gating on tetramer-positive populations, activation phenotypes were measured, and the number of CD27+ CD43+ influenza virus-specific CD8+ T cells was calculated (EFF) (right graphs). (C to E) Activation and effector function was measured by ICS after ex vivo stimulation with PA224 and NP366 peptides. The percentages of IFN-γ+ effectors (C) and polyfunctional effectors (D) were determined as described for Fig. 5. (E) The percentage of CD107a/b+ effectors was determined by calculating the percentage of effectors that were IFN-γ+/CD107a/b+ and dividing that percentage by the total percentage of IFN-γ+ effectors. (F to I) Cells from the mice used for Fig. 7 and 8 were also assayed for Tim-3 (F and G) and CTLA-4 (H and I) expression by flow cytometry. The day 8 BAL fluid CTLs were analyzed by MFI for Tim-3 and CTLA-4 staining of tetramer-positive CD8+ TLs. The data show a representative experiment of two with 4 or 5 mice per group. *, P < 0.05.

DISCUSSION

The history of influenza is dominated by routine pandemics that devastate the human population (33–36). Tremendous effort has been made to discover why these pandemic viruses are so severe, but the answer remains incomplete. In the current study, we have shown that high-path influenza virus infection is the result of a blunted CD8+ T cell response characterized by reduced numbers and functionality. The diminished CD8+ T cell response during high-path infection coincided with increased PD-1 expression. Anti-PD-L1 treatment rescued influenza virus-specific CD8+ T cell numbers and enhanced virus clearance, but CD8+ T cell functionality was not restored. Other studies have confirmed that CD8+ T cell exhaustion is a contributing factor to depressed immunity in chronic infections such as LCMV (13, 14) and in some acute lower respiratory tract infections (15). In contrast to these and other studies, we did not observe a full reversal of CD8+ T cell functionality by blocking the PD-1/PD-L1 interaction.

Several factors may contribute to the depressed CD8+ T cell response during PR8 infection. We observed a much more proinflammatory airway microenvironment, suggesting that this milieu promotes abnormal development of the CD8+ T cell response and high-path infection. Our analysis of the airway microenvironment revealed that several cytokines were dramatically increased at early time points during PR8 infection. Among the elevated cytokines was MCP-1/CCL2, which has been shown to recruit TipDCs to the site of infection and promote CD8+ expansion and survival (37). It is interesting to note that in our study, the elevated CCL2 response during high-path infection actually appears to prevent PR8-infected mice from suffering even more severe illness than we observed. IL-12p70 production was also increased in the airway microenvironment of PR8-infected mice. The role of IL-12 in the induction of T cell responses is well established (38). As with IL-12p70, we saw early, increased production of IL-6 and G-CSF in PR8-infected mice, whereas levels in x31-infected mice started much lower and gradually increased to coincide with the peak of the CD8+ T cell response. In vitro experiments suggested that G-CSF may be able to induce PD-1 expression on activated CD8+ T cells, just as we observed in vivo. The sum of our data therefore leads us to hypothesize that high-path influenza virus infection is defined by a highly inflammatory airway microenvironment at early time points, and these proinflammatory factors, including G-CSF and others, induce PD-1 expression on CD8+ T cells as they infiltrate the airway. Although these CD8+ T cells cannot be said to be exhausted based on the currently accepted definition, it is unambiguously clear that debilitated effector functionality in acute, high-path influenza A virus infection is associated with increased PD-1 expression on virus-specific CD8+ T cells.

Based on these results, depletion of CD8+ T cells in the low-path infection might be expected to generate the high-path phenotype. However, numerous studies in x31-infected mice have demonstrated that CD8 T cell depletion does not cause severe mortality, though it does delay viral clearance. This is likely due to a highly effective compensating antibody response in these animals (39–41).

Costimulatory roles for PD-1 have been described. Experiments on tolerance induction showed that lymphatic endothelial cells upregulate PD-1 in the absence of costimulation through 4-1BB (42). Increased PD-1 expression led to reduced expression of the IL-2 receptor and reduced CD8+ T cell survival. Another recent study revealed that inhibition of PD-L1 activity compromised CTL expansion during Listeria infection but not during vesicular stomatitis virus infection (43). These studies are consistent with a costimulatory role for PD-1 in acute influenza virus infection that leads to the canonical exhaustion phenotype and functionality seen in chronic infections.

Infection of primary cultures of human airway epithelia has shown that PR8 was more infectious than x31 (44). This early, increased replication may be propelling the genesis of a highly proinflammatory milieu that ablates CD8+ T cell function during acute influenza virus infection. In contrast, the slower replication of x31 during the earliest stages of infection may allow for a more methodical and efficient development of airway inflammation and the ensuing CD8+ T cell response. Previously referenced studies of PD-1 have shown that anti-PD-L1 treatment reversed the exhausted phenotype and restored CD8+ T cell functionality through blockade of the PD-1/PD-L1 interaction. While we saw increased numbers after blocking PD-L1 in vivo, CD8+ T cell function was not restored in high-path infection, compared to no apparent effect in low-path infection. The inability to rescue effector function suggests that the airway microenvironment in high-path infection may overwhelm the CD8+ T cell to the point that effector function cannot be rescued, even when PD-L1 -mediated suppression has been abrogated. The anti-PD-L1 treatment thus rescues CD8+ T cell numbers in high-path influenza virus infection, but not functionality. Additional studies to address this disparity are under way.

The slight differences that we saw in virus titers early after infection were not sufficient to wholly explain the mechanism of high-path infection. Because PR8 and x31 express different surface hemagglutinin and neuraminidase proteins, there may be any number of effects on attachment, fusion, or release of progeny virions that are magnified early, only to equilibrate later. Some viruses demonstrate a reduced ability to infect certain cell types (45), although recent mathematical modeling studies suggest that infectivity does not affect peak viral load (46). The influenza virus NS1 protein counters innate and adaptive immunity by inhibiting type I IFN production (47), but in our model both viruses contain the same NS1 gene. It is also known that increased cytokine production is associated with more pathogenic strains, even in cases of similar viral replication (5).

IL-6 and G-CSF both signal through Jak1-mediated phosphorylation of STAT3, which then dimerizes and acts as a transcription factor. We observed that infection of IL-6−/− mice failed to rescue the high-path phenotype. However, all cytokines in the IL-6 superfamily employ the gp130 receptor (48). Many of these cytokines are pleiotropic and have overlapping functions, making it difficult to discern individual contributions from any one family member to sophisticated networks and responses. To assess any effects from this family of cytokines, be it individually or the family as a whole, it may be more informative to target the common gp130 receptor. Like that of IL-6, G-CSF-mediated signaling depends on Jak1, although Jak2 and Tyk2 can also be used (23, 49, 50). In fact, the three-dimensional atomic structures of the human G-CSF/G-CSFR, IL-6/IL-6Rα/gp130, and IL-12/IL-12R complexes are all similar (48, 51, 52). It is therefore not surprising that signaling through the G-CSFR initiates the same signaling pathways as the IL-6 family of cytokines. Our in vivo data showed a slight improvement in effector CD8+ T cell responses after anti-G-CSF treatment during high-path infection. We therefore speculate that the highly proinflammatory nature of the airway microenvironment during PR8 infection may be the result of dysregulation of gp130-mediated signaling or the common Jak2/STAT3 signaling pathway initiated by the IL-6 superfamily receptors and the G-CSF receptor.

Suppressor of cytokine signaling 3 (SOCS3) inhibits STAT3-mediated proinflammatory signaling (23, 52–54). SOCS3 is upregulated by several cytokines, including IL-6, IL-10, and G-CSF, all of which induce STAT3 activation. SOCS3 then acts in a negative feedback loop to suppress IL-6 and G-CSF activity (55, 56), but does not inhibit IL-10. SOCS3 targets specific residues in gp130 and G-CSFR to disrupt signaling through STAT3 (53, 54, 57). This raises the possibility that disruption of SOCS3-mediated inhibition of proinflammatory responses may be a contributing factor to high-path influenza virus infection. It has been suggested that IL-7 can suppress SOCS3 in T cells, leading to IL-6 production (58). This allowed for extensive expansion of naive and effector T cells, which was at least partially dependent on IL-6. Our multiplex data from the airway microenvironment did not reveal consistent results with IL-7, but we did see expansion of CD8+ T cell numbers after anti-PD-L1 treatment and reduced viral titers in mice with high-path infection. One might therefore hypothesize a potential mechanism by which PD-L1 also promotes SOCS3 activity, which may explain the elevated IL-6 and reduced numbers we saw in high-path infection.

Certainly, any number of proteins associated with immune modification could be contributing to the disparate outcomes of high- and low-path influenza virus infection. One protein of interest might be T cell immunoglobulin and mucin protein-3 (Tim-3). Recently, it was shown that blocking the interaction of Tim-3 with its ligand, galectin-9, increased the CD8+ T cell response to influenza virus infection (21). Another study has shown that the most severely exhausted CD8+ T cells during chronic LCMV infection coexpress Tim-3 and PD-1 (59). During acute LCMV infection, Tim-3 was temporally expressed but eventually downregulated by day 30. However, we did not see any difference in Tim-3 expression in any of our experiments. Similarly, we saw no changes in expression of the T cell inhibitor CTLA-4. While it may not be surprising that observations associated with PD-1 and PD-L1 in chronic infection do not necessarily correlate to acute influenza virus infection, it is intriguing that we have found a strong relationship between PD-1 expression and high-path influenza virus infection that does not seem to respond to the same treatments that rescue CD8+ T cell exhaustion in chronic LCMV infection.

Our data suggest that dysregulation of the early immune response after high-path infection manifests as a highly proinflammatory airway microenvironment that induces CD8+ T cell exhaustion, defined by increased PD-1 expression. Blockade of the PD-1/PD-L1interaction did rescue CD8+ T cell numbers and improved virus clearance, but it failed to restore effector function on a per-cell basis. These data provide insight into the mechanism of high-path influenza virus infection and may identify potential therapeutic targets, should another devastating pandemic on the level of the 1918 Spanish flu assail mankind.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Scott Brown and Vandana Chaturvedi for insightful suggestions and invaluable discussion.

This work was supported by NIH grants AI065097 (P.G.T) and RO170251 (P.C.D.) and the NIH/NIAID St. Jude Center of Excellence for Influenza Research and Surveillance (HHSN266200700005C) and American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities at St. Jude Children's Research Hospital.

We have no financial conflicts of interest or competing interests.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 20 November 2013

REFERENCES

- 1.Moskophidis D, Kioussis D. 1998. Contribution of virus-specific CD8+ cytotoxic T cells to virus clearance or pathologic manifestations of influenza virus infection in a T cell receptor transgenic mouse model. J. Exp. Med. 188:223–232. 10.1084/jem.188.2.223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thomas PG, Keating R, Hulse-Post DJ, Doherty PC. 2006. Cell-mediated protection in influenza infection. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 12:48–54. 10.3201/eid1201.051237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Valkenburg SA, Rutigliano JA, Ellebedy AH, Doherty PC, Thomas PG, Kedzierska K. 2011. Immunity to seasonal and pandemic influenza A viruses. Microbes Infect. Inst. Pasteur 13:489–501. 10.1016/j.micinf.2011.01.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim TS, Sun J, Braciale TJ. 2011. T cell responses during influenza infection: getting and keeping control. Trends Immunol. 32:225–231. 10.1016/j.it.2011.02.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sanders CJ, Doherty PC, Thomas PG. 2011. Respiratory epithelial cells in innate immunity to influenza virus infection. Cell Tissue Res. 343:13–21. 10.1007/s00441-010-1043-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chan MC, Cheung CY, Chui WH, Tsao SW, Nicholls JM, Chan YO, Chan RW, Long HT, Poon LL, Guan Y, Peiris JS. 2005. Proinflammatory cytokine responses induced by influenza A (H5N1) viruses in primary human alveolar and bronchial epithelial cells. Respir. Res. 6:135. 10.1186/1465-9921-6-135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cheung CY, Poon LL, Lau AS, Luk W, Lau YL, Shortridge KF, Gordon S, Guan Y, Peiris JS. 2002. Induction of proinflammatory cytokines in human macrophages by influenza A (H5N1) viruses: a mechanism for the unusual severity of human disease? Lancet 360:1831–1837. 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11772-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lipatov AS, Andreansky S, Webby RJ, Hulse DJ, Rehg JE, Krauss S, Perez DR, Doherty PC, Webster RG, Sangster MY. 2005. Pathogenesis of Hong Kong H5N1 influenza virus NS gene reassortants in mice: the role of cytokines and B- and T-cell responses. J. Gen. Virol. 86:1121–1130. 10.1099/vir.0.80663-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.To KKW, Hung IFN, Li IWS, Lee K-L, Koo C-K, Yan W-W, Liu R, Ho K-Y, Chu K-H, Watt C-L, Luk W-K, Lai K-Y, Chow F-L, Mok T, Buckley T, Chan JFW, Wong SSY, Zheng B, Chen H, Lau CCY, Tse H, Cheng VCC, Chan K-H, Yuen K-Y. 2010. Delayed clearance of viral load and marked cytokine activation in severe cases of pandemic H1N1 2009 influenza virus infection. Clin. Infect. Dis. 50:850–859. 10.1086/650581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Iwasaki A, Medzhitov R. 2004. Toll-like receptor control of the adaptive immune responses. Nat. Immunol. 5:987–995. 10.1038/ni1112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vankayalapati R, Garg A, Porgador A, Griffith DE, Klucar P, Safi H, Girard WM, Cosman D, Spies T, Barnes PF. 2005. Role of NK cell-activating receptors and their ligands in the lysis of mononuclear phagocytes infected with an intracellular bacterium. J. Immunol. 175:4611–4617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hufford MM, Kim TS, Sun J, Braciale TJ. 2011. Antiviral CD8+ T cell effector activities in situ are regulated by target cell type. J. Exp. Med. 208:167–180. 10.1084/jem.20101850 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zajac AJ, Blattman JN, Murali-Krishna K, Sourdive DJ, Suresh M, Altman JD, Ahmed R. 1998. Viral immune evasion due to persistence of activated T cells without effector function. J. Exp. Med. 188:2205–2213. 10.1084/jem.188.12.2205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barber DL, Wherry EJ, Masopust D, Zhu B, Allison JP, Sharpe AH, Freeman GJ, Ahmed R. 2006. Restoring function in exhausted CD8 T cells during chronic viral infection. Nature 439:682–687. 10.1038/nature04444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Erickson JJ, Gilchuk P, Hastings AK, Tollefson SJ, Johnson M, Downing MB, Boyd KL, Johnson JE, Kim AS, Joyce S, Williams JV. 2012. Viral acute lower respiratory infections impair CD8+ T cells through PD-1. J. Clin. Invest. 122:2967–2982. 10.1172/JCI62860 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goldberg MV, Maris CH, Hipkiss EL, Flies AS, Zhen L, Tuder RM, Grosso JF, Harris TJ, Getnet D, Whartenby KA, Brockstedt DG, Dubensky TW, Jr, Chen L, Pardoll DM, Drake CG. 2007. Role of PD-1 and its ligand, B7-H1, in early fate decisions of CD8 T cells. Blood 110:186–192. 10.1182/blood-2006-12-062422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kilbourne ED. 1969. Future influenza vaccines and the use of genetic recombinants. Bull. World Health Organ. 41:643–645 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lamb RA, Krug RM. 1996. Orthomyxoviridae: the viruses and their replication. Lippincott-Raven Publishers, Philadelphia, PA [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hoffmann E, Krauss S, Perez D, Webby R, Webster RG. 2002. Eight-plasmid system for rapid generation of influenza virus vaccines. Vaccine 20:3165–3170. 10.1016/S0264-410X(02)00268-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Webby RJ, Andreansky S, Stambas J, Rehg JE, Webster RG, Doherty PC, Turner SJ. 2003. Protection and compensation in the influenza virus-specific CD8+ T cell response. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S. 100:7235–7240. 10.1073/pnas.1232449100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sharma S, Sundararajan A, Suryawanshi A, Kumar N, Veiga-Parga T, Kuchroo VK, Thomas PG, Sangster MY, Rouse BT. 2011. T cell immunoglobulin and mucin protein-3 (Tim-3)/Galectin-9 interaction regulates influenza A virus-specific humoral and CD8 T-cell responses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 108:19001–19006. 10.1073/pnas.1107087108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rutigliano JA, Morris MY, Yue W, Keating R, Webby RJ, Thomas PG, Doherty PC. 2010. Protective memory responses are modulated by priming events prior to challenge. J. Virol. 84:1047–1056. 10.1128/JVI.01535-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Panopoulos AD, Watowich SS. 2008. Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor: molecular mechanisms of action during steady state and “emergency” hematopoiesis. Cytokine 42:277–288. 10.1016/j.cyto.2008.03.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hand TW, Morre M, Kaech SM. 2007. Expression of IL-7 receptor α is necessary but not sufficient for the formation of memory CD8 T cells during viral infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104:11730–11735. 10.1073/pnas.0705007104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Joshi NS, Cui W, Chandele A, Lee HK, Urso DR, Hagman J, Gapin L, Kaech SM. 2007. Inflammation directs memory precursor and short-lived effector CD8(+) T cell fates via the graded expression of T-bet transcription factor. Immunity 27:281–295. 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.07.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sarkar S, Kalia V, Haining WN, Konieczny BT, Subramaniam S, Ahmed R. 2008. Functional and genomic profiling of effector CD8 T cell subsets with distinct memory fates. J. Exp. Med. 205:625–640. 10.1084/jem.20071641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Trobaugh DW, Yang L, Ennis FA, Green S. 2010. Altered effector functions of virus-specific and virus cross-reactive CD8+ T cells in mice immunized with related flaviviruses. Eur. J. Immunol. 40:1315–1327. 10.1002/eji.200839108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hikono H, Kohlmeier JE, Takamura S, Wittmer ST, Roberts AD, Woodland DL. 2007. Activation phenotype, rather than central- or effector-memory phenotype, predicts the recall efficacy of memory CD8+ T cells. J. Exp. Med. 204:1625–1636. 10.1084/jem.20070322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Roberts AD, Ely KH, Woodland DL. 2005. Differential contributions of central and effector memory T cells to recall responses. J. Exp. Med. 202:123–133. 10.1084/jem.20050137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lieschke GJ, Stanley E, Grail D, Hodgson G, Sinickas V, Gall JA, Sinclair RA, Dunn AR. 1994. Mice lacking both macrophage- and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor have macrophages and coexistent osteopetrosis and severe lung disease. Blood 84:27–35 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hofmann P, Sprenger H, Kaufmann A, Bender A, Hasse C, Nain M, Gemsa D. 1997. Susceptibility of mononuclear phagocytes to influenza A virus infection and possible role in the antiviral response. J. Leukoc. Biol. 61:408–414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.La Gruta NL, Turner SJ, Doherty PC. 2004. Hierarchies in cytokine expression profiles for acute and resolving influenza virus-specific CD8+ T cell responses: correlation of cytokine profile and TCR avidity. J. Immunol. 172:5553–5560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brockwell-Staats C, Webster RG, Webby RJ. 2009. Diversity of influenza viruses in swine and the emergence of a novel human pandemic influenza A (H1N1). Influenza Other Respir. Viruses 3:207–213. 10.1111/j.1750-2659.2009.00096.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Claas EC, Osterhaus AD, van Beek R, De Jong JC, Rimmelzwaan GF, Senne DA, Krauss S, Shortridge KF, Webster RG. 1998. Human influenza A H5N1 virus related to a highly pathogenic avian influenza virus. Lancet 351:472–477. 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)11212-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Johnson NPAS, Mueller J. 2002. Updating the accounts: global mortality of the 1918-1920 “Spanish” influenza pandemic. Bull. Hist. Med. 76:105–115. 10.1353/bhm.2002.0022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Subbarao K, Klimov A, Katz J, Regnery H, Lim W, Hall H, Perdue M, Swayne D, Bender C, Huang J, Hemphill M, Rowe T, Shaw M, Xu X, Fukuda K, Cox N. 1998. Characterization of an avian influenza A (H5N1) virus isolated from a child with a fatal respiratory illness. Science 279:393–396. 10.1126/science.279.5349.393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Aldridge JR, Moseley CE, Boltz DA, Negovetich NJ, Reynolds C, Franks J, Brown SA, Doherty PC, Webster RG, Thomas PG. 2009. TNF/iNOS-producing dendritic cells are the necessary evil of lethal influenza virus infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106:5306–5311. 10.1073/pnas.0900655106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Trinchieri G. 2003. Interleukin-12 and the regulation of innate resistance and adaptive immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 3:133–146. 10.1038/nri1001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Eichelberger M, Allan W, Zijlstra M, Jaenisch R, Doherty PC. 1991. Clearance of influenza virus respiratory infection in mice lacking class I major histocompatibility complex-restricted CD8+ T cells. J. Exp. Med. 174:875–880. 10.1084/jem.174.4.875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Epstein SL, Lo CY, Misplon JA, Lawson CM, Hendrickson BA, Max EE, Subbarao K. 1997. Mechanisms of heterosubtypic immunity to lethal influenza A virus infection in fully immunocompetent, T cell-depleted, beta2-microglobulin-deficient, and J. chain-deficient mice. J. Immunol. 158:1222–1230 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sarawar SR, Carding SR, Allan W, McMickle A, Fujihashi K, Kiyono H, McGhee JR, Doherty PC. 1993. Cytokine profiles of bronchoalveolar lavage cells from mice with influenza pneumonia: consequences of CD4+ and CD8+ T cell depletion. Reg. Immunol. 5:142–150 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tewalt EF, Cohen JN, Rouhani SJ, Guidi CJ, Qiao H, Fahl SP, Conaway MR, Bender TP, Tung KS, Vella AT, Adler AJ, Chen L, Engelhard VH. 2012. Lymphatic endothelial cells induce tolerance via PD-L1 and lack of costimulation leading to high-level PD-1 expression on CD8 T cells. Blood 120:4772–4782. 10.1182/blood-2012-04-427013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Xu D, Fu H-H, Obar JJ, Park J-J, Tamada K, Yagita H, Lefrançois L. 2013. A potential new pathway for PD-L1 costimulation of the CD8-T cell response to Listeria monocytogenes infection. PLoS One 8:e56539. 10.1371/journal.pone.0056539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Slepushkin VA, Staber PD, Wang G, McCray PB, Jr, Davidson BL. 2001. Infection of human airway epithelia with H1N1, H2N2, and H3N2 influenza A virus strains. Mol. Ther. J. Am. Soc. Gene Ther. 3:395–402. 10.1006/mthe.2001.0277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Reading PC, Whitney PG, Pickett DL, Tate MD, Brooks AG. 2010. Influenza viruses differ in ability to infect macrophages and to induce a local inflammatory response following intraperitoneal injection of mice. Immunol. Cell Biol. 88:641–650. 10.1038/icb.2010.11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Miao H, Hollenbaugh JA, Zand MS, Holden-Wiltse J, Mosmann TR, Perelson AS, Wu H, Topham DJ. 2010. Quantifying the early immune response and adaptive immune response kinetics in mice infected with influenza A virus. J. Virol. 84:6687–6698. 10.1128/JVI.00266-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Garcia-Sastre A, Egorov A, Matassov D, Brandt S, Levy DE, Durbin JE, Palese P, Muster T. 1998. Influenza A virus lacking the NS1 gene replicates in interferon-deficient systems. Virology 252:324–330. 10.1006/viro.1998.9508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Taga T, Kishimoto T. 1997. Gp130 and the interleukin-6 family of cytokines. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 15:797–819. 10.1146/annurev.immunol.15.1.797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shimoda K, Feng J, Murakami H, Nagata S, Watling D, Rogers NC, Stark GR, Kerr IM, Ihle JN. 1997. Jak1 plays an essential role for receptor phosphorylation and Stat activation in response to granulocyte colony-stimulating factor. Blood 90:597–604 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Guschin D, Rogers N, Briscoe J, Witthuhn B, Watling D, Horn F, Pellegrini S, Yasukawa K, Heinrich P, Stark GR. 1995. A major role for the protein tyrosine kinase JAK1 in the JAK/STAT signal transduction pathway in response to interleukin-6. EMBO J. 14:1421–1429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tamada T, Honjo E, Maeda Y, Okamoto T, Ishibashi M, Tokunaga M, Kuroki R. 2006. Homodimeric cross-over structure of the human granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (GCSF) receptor signaling complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103:3135–3140. 10.1073/pnas.0511264103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Aritomi M, Kunishima N, Okamoto T, Kuroki R, Ota Y, Morikawa K. 1999. Atomic structure of the GCSF-receptor complex showing a new cytokine-receptor recognition scheme. Nature 401:713–717. 10.1038/44394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nicholson SE, De Souza D, Fabri LJ, Corbin J, Willson TA, Zhang JG, Silva A, Asimakis M, Farley A, Nash AD, Metcalf D, Hilton DJ, Nicola NA, Baca M. 2000. Suppressor of cytokine signaling-3 preferentially binds to the SHP-2-binding site on the shared cytokine receptor subunit gp130. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97:6493–6498. 10.1073/pnas.100135197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lehmann U, Schmitz J, Weissenbach M, Sobota RM, Hortner M, Friederichs K, Behrmann I, Tsiaris W, Sasaki A, Schneider-Mergener J, Yoshimura A, Neel BG, Heinrich PC, Schaper F. 2003. SHP2 and SOCS3 contribute to Tyr-759-dependent attenuation of interleukin-6 signaling through gp130. J. Biol. Chem. 278:661–671. 10.1074/jbc.M210552200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yasukawa H, Ohishi M, Mori H, Murakami M, Chinen T, Aki D, Hanada T, Takeda K, Akira S, Hoshijima M, Hirano T, Chien KR, Yoshimura A. 2003. IL-6 induces an anti-inflammatory response in the absence of SOCS3 in macrophages. Nat. Immunol. 4:551–556. 10.1038/ni938 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kimura A, Kinjyo I, Matsumura Y, Mori H, Mashima R, Harada M, Chien KR, Yasukawa H, Yoshimura A. 2004. SOCS3 is a physiological negative regulator for granulopoiesis and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor receptor signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 279:6905–6910. 10.1074/jbc.C300496200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Irandoust MI, Aarts LHJ, Roovers O, Gits J, Erkeland SJ, Touw IP. 2007. Suppressor of cytokine signaling 3 controls lysosomal routing of G-CSF receptor. EMBO J. 26:1782–1793. 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601640 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pellegrini M, Calzascia T, Toe JG, Preston SP, Lin AE, Elford AR, Shahinian A, Lang PA, Lang KS, Morre M, Assouline B, Lahl K, Sparwasser T, Tedder TF, Paik J-H, DePinho RA, Basta S, Ohashi PS, Mak TW. 2011. IL-7 engages multiple mechanisms to overcome chronic viral infection and limit organ pathology. Cell 144:601–613. 10.1016/j.cell.2011.01.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jin H-T, Anderson AC, Tan WG, West EE, Ha S-J, Araki K, Freeman GJ, Kuchroo VK, Ahmed R. 2010. Cooperation of Tim-3 and PD-1 in CD8 T-cell exhaustion during chronic viral infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107:14733–14738. 10.1073/pnas.1009731107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]