Abstract

UL16 is a tegument protein of herpes simplex virus (HSV) that is conserved among all members of the Herpesviridae, but its function is poorly understood. Previous studies revealed that UL16 is associated with capsids in the cytoplasm and interacts with the membrane protein UL11, which suggested a “bridging” function during cytoplasmic envelopment, but this conjecture has not been tested. To gain further insight, cells infected with UL16-null mutants were examined by electron microscopy. No defects in the transport of capsids to cytoplasmic membranes were observed, but the wrapping of capsids with membranes was delayed. Moreover, clusters of cytoplasmic capsids were often observed, but only near membranes, where they were wrapped to produce multiple capsids within a single envelope. Normal virion production was restored when UL16 was expressed either by complementing cells or from a novel position in the HSV genome. When the composition of the UL16-null viruses was analyzed, a reduction in the packaging of glycoprotein E (gE) was observed, which was not surprising, since it has been reported that UL16 interacts with this glycoprotein. However, levels of the tegument protein VP22 were also dramatically reduced in virions, even though this gE-binding protein has been shown not to depend on its membrane partner for packaging. Cotransfection experiments revealed that UL16 and VP22 can interact in the absence of other viral proteins. These results extend the UL16 interaction network beyond its previously identified binding partners to include VP22 and provide evidence that UL16 plays an important function at the membrane during virion production.

INTRODUCTION

Infectious herpesviruses contain approximately 40 viral proteins and are produced when their DNA-containing capsids are wrapped with a cell-derived membrane in the cytoplasm (1). This envelopment process is driven by complex interactions that are still poorly understood but is known to involve bridging interactions provided by a growing list of tegument proteins, which provide linkages between the capsid and viral membrane proteins (1–3). The UL16 tegument protein of herpes simplex virus (HSV) is remarkable for its numerous interactions with several other viral proteins, namely, tegument protein UL21 (4, 5), membrane protein UL11 (4, 6–8), membrane glycoprotein E (gE) (4, 9), and an unidentified protein(s) that is associated with the capsid (10–12). UL16 is conserved among all the alpha-, beta-, and gammaherpesvirinae (2, 13, 14), but its actual function remains unknown.

There are several reasons for suggesting a role for UL16 in HSV envelopment. The earliest study showed that a UL16-null mutant (here named the ΔUL16B mutant) produces infectious virions at a level only one-tenth that of the wild-type virus (15). Also, UL16 has been shown to be bound in some manner to cytoplasmic capsids (10, 16, 17), and thus, its direct interactions with membrane proteins UL11 (8) and gE (9) suggest that UL16 might provide bridging functions that help drive virion production, as first proposed 10 years ago (7). This model is consistent with the observation that gE- and UL11-null mutants both exhibit reductions in the level of virion production (12, 18–22). Finally, studies of several UL16 homologs have revealed defects in virion production when they are absent. In particular, in the cases of human cytomegalovirus (23), mouse cytomegalovirus (MCMV) (24), and murine gammaherpesvirus 68 (13), electron microscopy of null mutants revealed that capsids were not associated with membranes, and hence, no enveloped virions were seen. However, these studies suggest that the block to virion production occurs prior to transport to the membrane for mutant viruses. In the case of alphaherpesviruses that lack UL16, reduced numbers of infectious virions are produced for HSV and pseudorabies virus (15, 25), but the location of the inefficient egress step has not been identified.

In this study, mutants lacking the UL16 gene of HSV-1 were studied in order to ascertain the effects on virion morphogenesis, composition, viral replication, and viral protein expression and packaging. The results revealed an inefficient envelopment step in the cytoplasm after capsids arrived at the membrane. Unexpectedly, a defect in virion packaging was found for another tegument protein, VP22, which is encoded by the UL49 gene (26). VP22 is a phosphorylated protein that is known to interact within a network that includes gE, gD, VP16, ICP0, and gM (8, 9, 26–35). It also binds to and negatively regulates “virion host shutoff” (VHS) protein, and thus, mutants that lack VP22 have defects in virus production and exhibit reduced protein synthesis (36, 37). Because no evidence to link the VP22 and UL16 interaction networks has been reported, we investigated the possibility that these two proteins interact. Here we report the first evidence that they can. Although these results add to the bewildering number of viral protein interactions that need to be studied in depth, it is clear that UL16 does play a role at the membrane during envelopment.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell lines.

Vero cells and HaCaT cells (human keratinocytes) were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM; Gibco) containing 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS; HyClone), 5% bovine calf serum (BCS; HyClone), and penicillin-streptomycin (Gibco). The complementing cell line G5 (38) was a generous gift from Prashant Desai (Johns Hopkins University) and was cultured and maintained in DMEM containing 10% FBS and 1 mg/ml G418 (Gibco). All infected cell lines were cultured in DMEM containing 2% FBS, 25 mM HEPES, glutamine (0.3 μg/ml), and penicillin-streptomycin.

Viruses.

Wild-type (WT) HSV-1 (KOS strain) was derived from a bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) containing the HSV-1 KOS genome (39). HSV-1 strain F lacking the UL16 gene (here designated the ΔUL16B strain) was a kind gift of Joel Baines (Cornell University) (15). The BAC.KOS plasmid was used to create deletion and recombinant viral genomes (Fig. 1) via homologous recombination in Escherichia coli by means of a galK selection method (40), as described previously (12). Presumptive clones were screened both by PCR and by HindIII digestion of purified BAC DNA, and DNA from positive clones was isolated by using the Large-Construct kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. To produce initial stocks of virus, Vero cells were transfected via the Lipofectamine 2000 method (Invitrogen). Viruses in these “transfection stocks” were amplified by infecting Vero cells (for the WT, ΔUL16S, ΔUL16B, ΔUL16Rev, ΔUL16Rev35, ΔVP22, and ΔVP22Rev strains) or G5 cells (for the ΔUL16S and ΔUL16B strains) at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.01, as described previously (12), and the titers of the resulting 1st-passage stocks (“P1 stocks”) were determined by plaque assays on Vero or G5 cells.

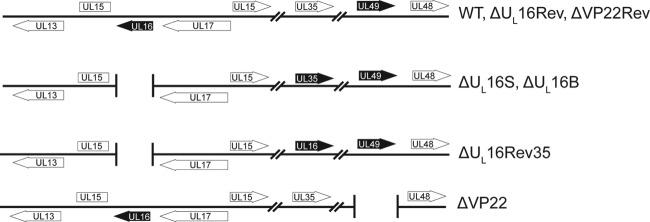

FIG 1.

Virus mutants. The relevant regions of the HSV-1 genome are shown. Black arrows represent altered genes. The ΔUL16S and ΔVP22 null mutants were generated by removal of their coding sequences (UL16 and UL49, respectively) from the wild-type BAC.KOS plasmid. The UL16 and VP22 coding sequences were restored to generate ΔUL16Rev and ΔVP22Rev, respectively. For the ΔUL16Rev35 strain, the UL35 coding sequence was replaced with that for UL16 in order to rule out context-specific defects associated with the deletion.

Antibodies.

UL16- and UL11-specific rabbit antisera have been described previously (7, 20). Antisera specific for VP5 (41) and VP22 (7) were kindly supplied by Richard Courtney (Pennsylvania State University). The rabbit anti-VP16 antibody was purchased from Clontech (product no. 3844-1). The rabbit polyclonal anti-gE antibody UP1725 (42) was generously provided by Harvey Friedman (University of Pennsylvania).

Growth curves and plaque assays.

Viral growth curves were performed as described previously (12). Briefly, Vero or G5 cells were infected with virus for 1 h at an MOI of 1 and were subsequently washed with an acid wash (135 mM NaCl, 10 mM KCl, 40 mM citric acid [pH 3.0]) followed by 1% FBS in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Then the cells were maintained in DMEM containing 2% FBS. At 0, 8, 12, 24, 36, and 48 h postinfection, infected cells and medium were harvested either together (total virus production) or separately (cell-associated and released virus, respectively), and the titers of virus collected from these samples were determined on Vero cells by plaque assays.

Packaging assay and viral protein expression.

The incorporation of viral proteins into extracellular virions and intracellular expression of viral proteins were measured as described previously (12). In brief, Vero or G5 cells were infected with virus at an MOI of 5, and at 18 to 24 h postinfection, extracellular virions were collected from the medium by centrifugation through a 30% sucrose cushion at 4°C for 1 h at 83,500 × g in a Beckman SW41 rotor. Total-cell lysates were prepared by resuspending infected cells in sample buffer, followed by sonication. Samples were adjusted to have equal amounts of VP5 (the major capsid protein) so as to ensure that equal numbers of virions and infected-cell lysates were present. All samples were resolved in 11% SDS-PAGE gels and were visualized by Western blotting using the antibodies specified in Fig. 6, 7, and 9. All experiments were repeated in triplicate. Films were scanned, and bands were subsequently quantified, on a densitometer using Quantity One software.

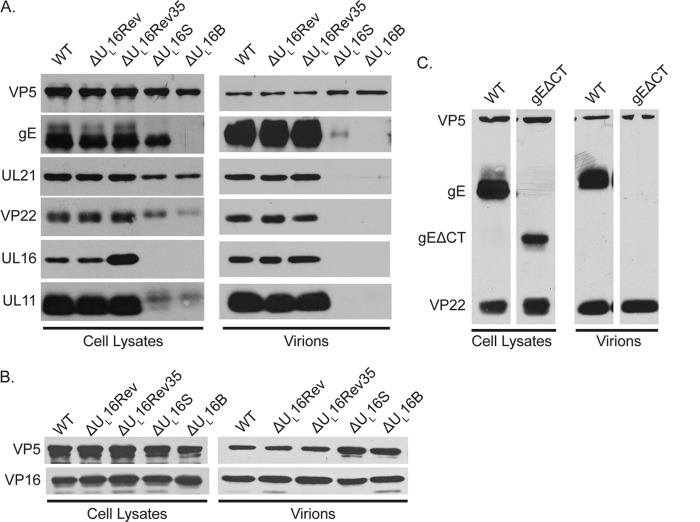

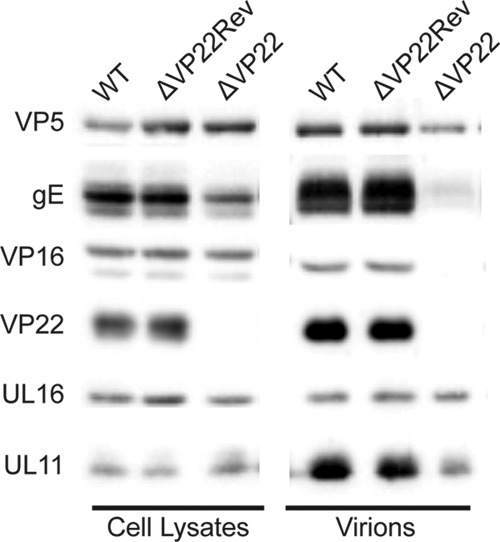

FIG 6.

Cellular expression and packaging of viral proteins. Vero cells were infected with the indicated viruses at an MOI of 5, and the cultures were harvested 18 to 24 h postinfection. Infected cells were directly dissolved in sample buffer (left side of each panel), while extracellular virions were first concentrated by pelleting through a 30% sucrose cushion and then dissolved in sample buffer (right side of each panel). The samples were analyzed by Western blotting with antibodies against the indicated viral proteins, and the amount of each sample loaded was normalized based on the amount of the major capsid protein, VP5. Blots from one of three independent experiments are shown. (A and B) Results for the ΔUL16 mutants and revertant viruses. (C) Results for the mutant lacking the cytoplasmic tail of gE (gEΔCT).

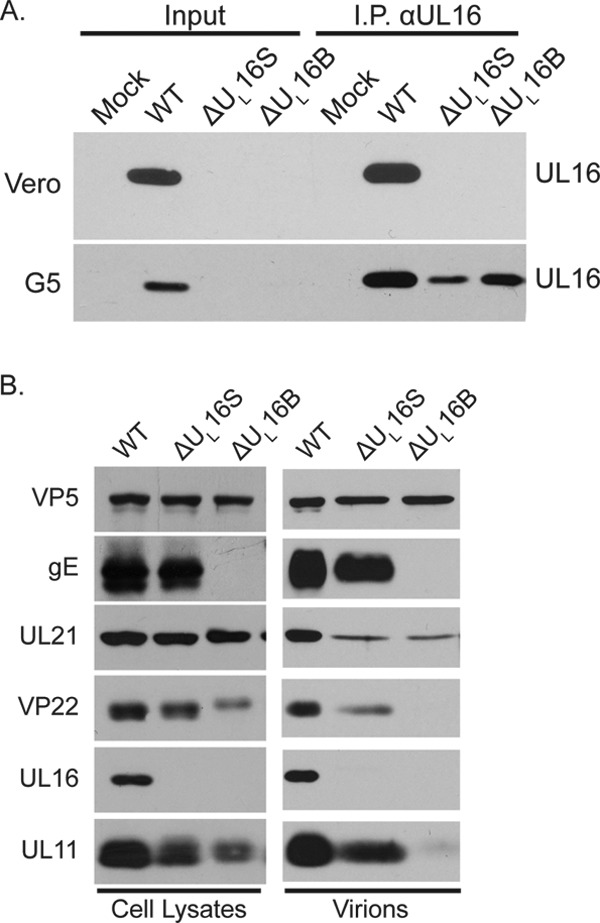

FIG 7.

Expression and packaging of viral proteins in complementing G5 cells. (A) Vero and G5 cells were infected with the indicated viruses, and cytoplasmic lysates were prepared 18 h postinfection. (Input lanes) A fraction of the total lysates was loaded as a control for protein expression. (I.P. lanes) Antibodies were used to immunoprecipitate UL16 and to subsequently detect UL16 expression by Western blot analysis. (B) Viral protein expression and packaging by UL16-deficient viruses in G5 cells.

FIG 9.

Expression and packaging of viral proteins by the VP22-null virus. Vero cells were infected with the indicated viruses (MOI, 5). The cultures were harvested 18 to 24 h postinfection, and the indicated viral proteins present in total-cell lysates (left) and virions (right) were detected by Western blotting.

Immunoprecipitation of UL16.

To detect the low levels of UL16 produced in G5 cells, the protein was concentrated and analyzed in a manner similar to that described previously (9). In brief, cells were infected at an MOI of 5, and after 18 h, they were lysed in a buffer containing 1% NP-40. The lysates were clarified by centrifugation and were subsequently incubated with rabbit anti-UL16 serum with rocking for 1 h at 4°C. Protein G-agarose (Roche) was added, and the solution was incubated for an additional 4 h with rocking at 4°C. Beads were washed 3 times in PBS and were resuspended in SDS sample buffer, and the proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE. UL16 was visualized with rabbit anti-UL16 serum and horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated rabbit IgG TrueBlot (eBioscience).

Electron microscopy.

Cells were seeded on 60-mm Permanox tissue culture dishes (Nalge Nunc International) 24 h prior to infection with either the WT, ΔUL16S, ΔUL16B, ΔUL16Rev, or ΔUL16Rev35 strain at an MOI of 5. At 20 to 24 h postinfection, cells were washed 3 times with ice cold 0.1 M sodium cacodylate and were fixed for 1 h at 4°C in fixation buffer (0.5% [vol/vol] glutaraldehyde, 0.04% [wt/vol] paraformaldehyde, 0.1 M sodium cacodylate). Fixed samples were washed 3 times with 0.1 M sodium cacodylate and were subsequently postfixed in 1% osmium–1.5% potassium ferrocyanide overnight at 4°C. Samples were then washed 3 times in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate, dehydrated with ethyl alcohol (EtOH), and embedded in Epon 812 prior to staining and sectioning. All samples were processed and sectioned in the Microscopy Imaging Facility (Pennsylvania State University College of Medicine) and were visualized using a JEOL JEM-1400 Digital Capture transmission electron microscope.

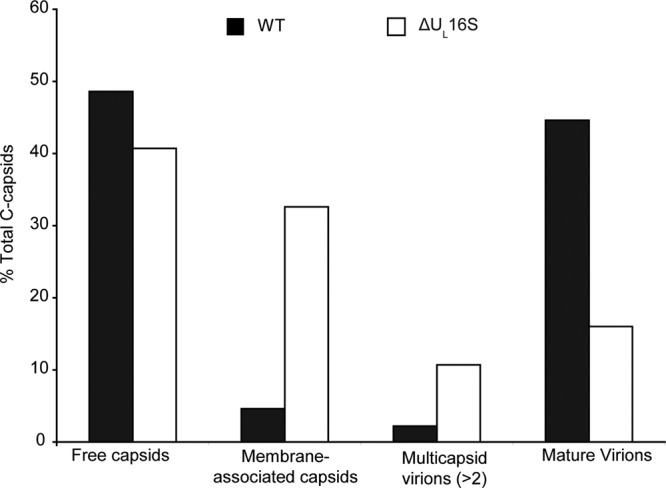

Electron micrographs of Vero cells infected with the WT or ΔUL16S strain were used to quantify and classify cytoplasmic HSV-1 capsids. At least 60 individual micrographs from 3 independent infections (see above) were used, and a total of 1,008 capsids for the WT and 607 capsids for the ΔUL16S mutant were observed and were classified as either naked, membrane associated, multicapsid, or mature virions.

Confocal microscopy.

Vero cells were transfected with the constructs described in the legend to Fig. 10 and were imaged by confocal microscopy with a Leica TCS SP8 microscope in the Microscopy Imaging Facility (Pennsylvania State University College of Medicine), as described previously (4, 20). The VP22 constructs used in these experiments (43) were a kind gift of Richard Courtney (Pennsylvania State University).

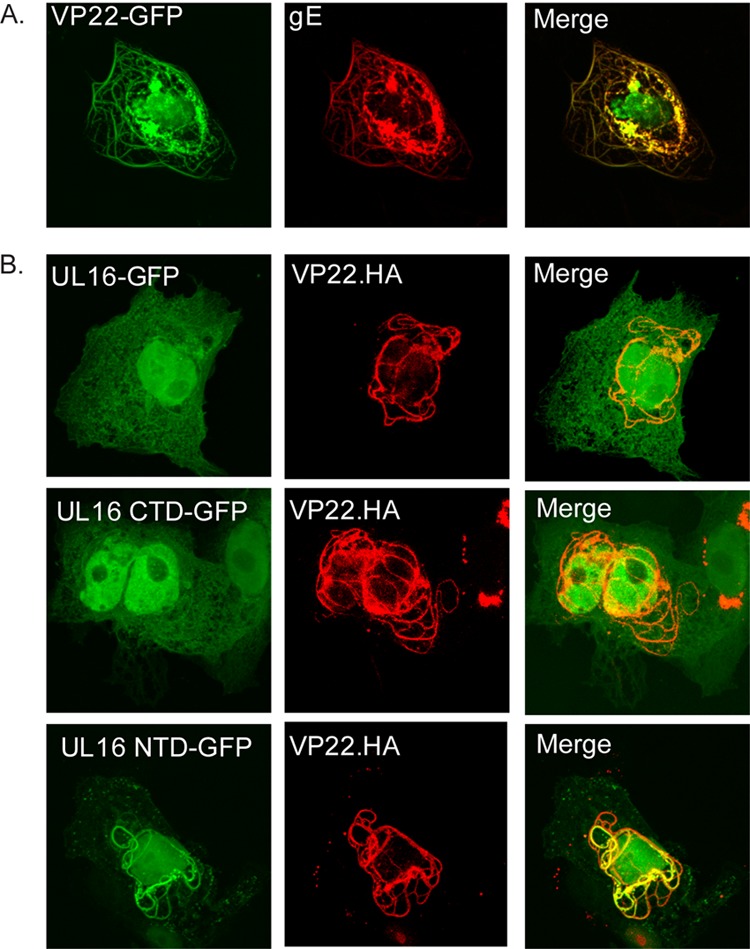

FIG 10.

Colocalization analysis of UL16 and VP22. (A) Vero cells were cotransfected with plasmids expressing VP22-GFP and its binding partner gE as a positive control. (B) Vero cells were cotransfected with HA-tagged, full-length VP22 and the indicated GFP-tagged UL16 constructs. All samples were viewed and imaged by confocal microscopy.

RESULTS

Ultrastructural characterization of UL16-null mutants.

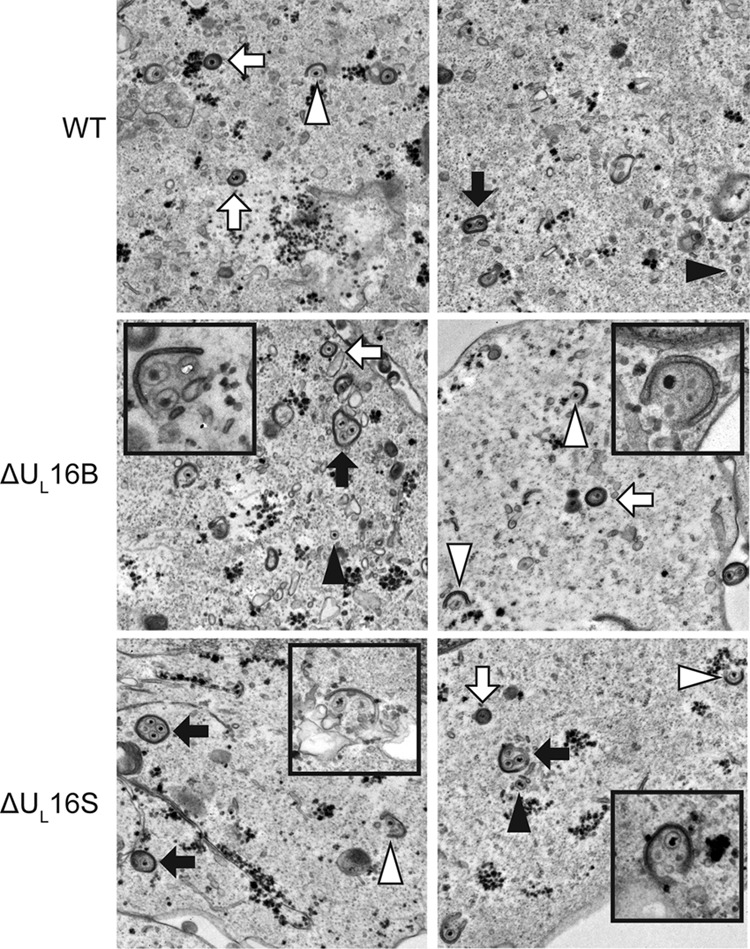

Previous studies have suggested a role for UL16 in virion production (15, 17); however, the nature of the block that occurs in its absence has not been defined. To address this, we closely examined the wild-type KOS strain and a ΔUL16 mutant of the F strain (the ΔUL16B virus) by electron microscopy (Fig. 2). To our surprise, large multicapsid structures were prevalent in Vero cells infected with the ΔUL16B mutant (Fig. 2, black arrows), along with virions of normal appearance (white arrows). These multicapsid structures were largely absent from WT-infected cells, although an occasional aberrant particle could be observed at an extremely low frequency (Fig. 2, WT, black arrow).

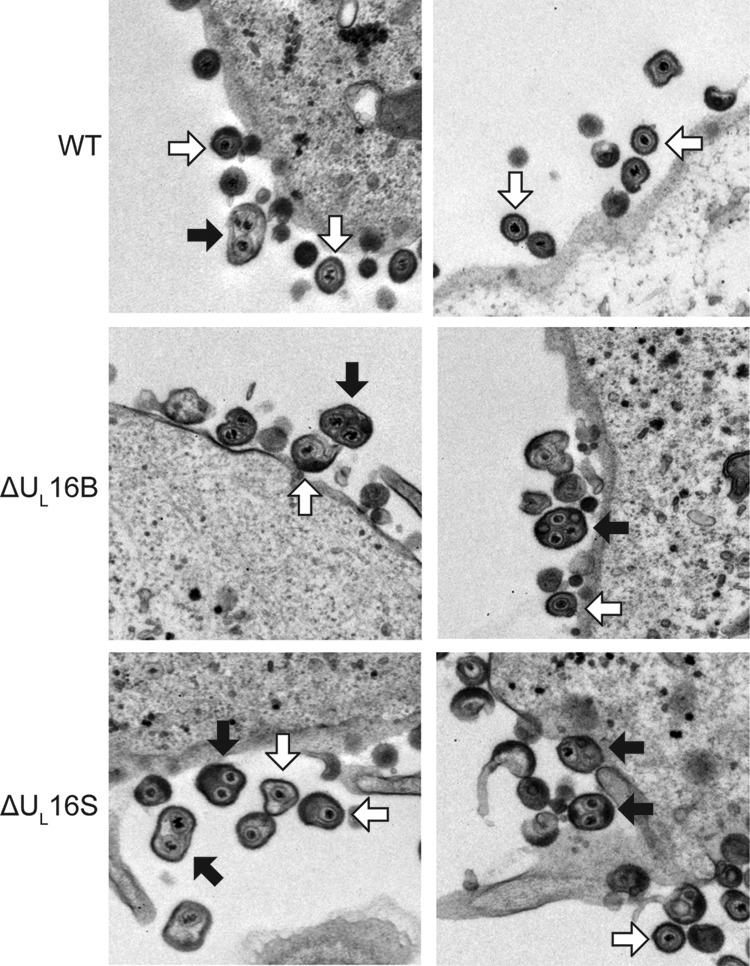

FIG 2.

Ultrastructural properties of extracellular ΔUL16 virions. Vero cells were infected with the indicated viruses (MOI, 1) 24 h prior to fixing and processing for thin-section electron microscopy. Examples of multicapsid virions (black arrows) and single-capsid virions (white arrows) are indicated.

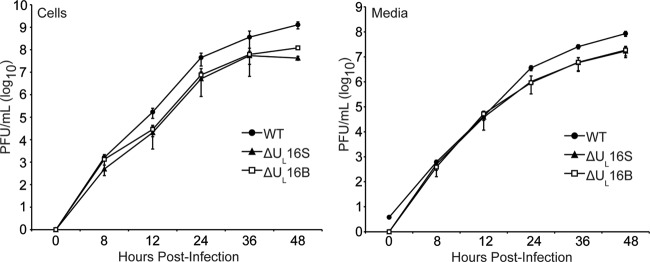

To ascertain whether the abnormal virion structures were HSV strain specific or were due to an unidentified secondary mutation in the ΔUL16B virus, another null mutant was made in the KOS strain (the ΔUL16S virus). To this end, the UL16 coding region was deleted from the BAC.KOS plasmid within E. coli, and the resulting genome was subsequently transfected into Vero cells to generate a virus stock. Unlike the ΔUL16B virus, which has an imprecise deletion (15), the ΔUL16S mutant lacks all of the UL16 coding sequence and nothing else. Moreover, the ΔUL16S virus was made with minimal passages (see Materials and Methods), whereas the ΔUL16B virus was made via traditional selection methods in Vero cells, followed by several rounds of plaque purification (15), a process that is likely to select unintended mutations. The two mutants produced similar levels of cell-associated and extracellular viruses, but these levels were one-tenth that of the WT at an MOI of 1 (Fig. 3). Similar growth kinetics were also observed for infections at MOIs of 0.01 and 5, indicating that the phenotype is not multiplicity dependent or due to a delay in viral growth (data not shown). Electron microscopy revealed that the ΔUL16S mutant also releases multicapsid virions (Fig. 2), suggesting that the aberrant particles form as a result of the UL16 deletion and that the phenotype is not strain specific. In addition, this phenotype does not appear to be cell type dependent, because multicapsid particles were readily observed in both ΔUL16S mutant- and ΔUL16B mutant-infected HaCaT cells (data not shown).

FIG 3.

Growth kinetics of ΔUL16 viruses. Intracellular (Cells) and extracellular (Media) viruses were harvested at the indicated times after infection of Vero cells (MOI, 1), and titers were determined by plaque assays on Vero cells. Each measurement was made in triplicate, and the error bars represent the standard errors of the means.

Within the cytoplasm, vesicles containing multicapsid structures were seen for both ΔUL16S virus- and ΔUL16B virus-infected Vero cells (Fig. 4, black arrows). An occasional aberrant particle could be observed in WT-infected cells (Fig. 4); however, the vast majority of the capsids were singly enveloped. No defects were observed in DNA packaging or in the egress of capsids from the nucleus. Moreover, no obvious accumulation of cytoplasmic capsids, as seen for mutants that lack UL11 (18) or UL36 (44), was observed. Instead, most of the individual capsids observed in cells infected with the ΔUL16S or ΔUL16B virus were only partially wrapped with a membrane and were presumably in the midst of secondary envelopment (Fig. 4). This finding was in contrast to that for WT-infected cells, where the majority of single capsids were observed to be completely enveloped. The various stages of capsid egress were classified and quantified (see Materials and Methods) (Fig. 5). The numbers of membrane-free capsids were similar for the WT (48%) and the ΔUL16S mutant (41%), but a large reduction was seen in the number of fully wrapped capsids for the mutant (16% versus 44%). Instead, 32% of the ΔUL16S capsids appeared to be in the process of acquiring an envelope, compared to only 5% for the WT. Importantly, clusters of capsids were not observed at positions distant from membranes, but many examples of capsid clusters apparently in the act of envelopment were found for the ΔUL16S and ΔUL16B mutants (Fig. 4). Thus, the formation of multicapsid virions appears to be the result of a low rate of envelopment after individual capsids arrive at the membrane.

FIG 4.

Multiple capsids are wrapped at once. Representative thin-section electron micrographs of WT- and ΔUL16 mutant-infected (MOI, 1) Vero cells are shown at 24 h postinfection. Simultaneous envelopment of several capsids at a time was detected in ΔUL16 mutant-infected Vero cells (insets). Examples of fully wrapped multicapsid virions (black arrows), single-capsid virions (white arrows), partially wrapped capsids (white arrowheads), and free capsids (black arrowheads) are indicated.

FIG 5.

Quantitation of the various species of intracellular capsids. Electron micrographs of Vero cells infected for 24 h with WT or ΔUL16S virus (MOI, 1) were obtained, and the DNA-filled capsids were counted and classified as either free capsids (not near membranes), membrane-associated capsids, multicapsid virions (2 or more capsids fully wrapped with a single envelope), or mature virions (completely wrapped with a single capsid). Micrographs from 3 independent experiments were used, yielding a total of 1,008 WT capsids and 607 ΔUL16S capsids.

Extensive attempts to quantify the amount of extracellular multicapsid virions biochemically proved unsuccessful. Two different approaches were employed in an effort to separate the multicapsid virions from single virions. Neither flotation nor sedimentation of concentrated extracellular virions through sucrose gradients yielded different separation profiles for WT and ΔUL16S virions (data not shown). Because it was necessary to pellet and resuspend the virions prior to these assays, we cannot rule out the possibility that the multicapsid virions are fragile and fell apart during the concentration steps, as was observed for MCMV (45, 46).

Expression and virion packaging of known UL16 binding partners.

UL16 has been proposed to exist in a complex with UL11, UL21, and gE, and recent cotransfection studies strongly support this model (4). Because it is well known that the elimination of one viral protein can change the expression and packaging of its binding partners (12, 31, 47–50), we examined the amounts of these proteins relative to that of the WT in cell lysates infected with the ΔUL16 mutants and in extracellular virions by Western blotting. At least three measurements were made for each protein (results of one experiment are shown in Fig. 6A). UL11 expression levels were notably reduced in the ΔUL16S and ΔUL16B mutants (down 57% ± 22% and 58% ± 22%, respectively), but the amounts that were packaged into virions were almost undetectable (reduced by 93% ± 7% and 95% ± 7%) and migrated more slowly than WT UL11 in the gel. No significant alteration in UL21 expression levels could be detected for the ΔUL16S and ΔUL16B mutants (present at 94% ± 36% and 98% ± 29% of WT levels); however, the levels of virion packaging were drastically reduced (down 89% ± 7% and 92% ± 11%).

For gE, the two UL16-null viruses produced results completely different from those for UL11 and UL21 (Fig. 6A). The gE expression level was reduced only slightly for the ΔUL16S mutant (present at 81% ± 33% of the WT level), but the amount packaged into virions was dramatically altered (down 91% ± 11%), providing further support for the recently described UL16–gE interaction (9). Moreover, cell-associated gE seemed to exhibit less of the slower-migrating, mature glycosylated forms, in agreement with the observation that this glycoprotein is not found on the surfaces of infected cells in the absence of UL16 (4). In contrast, gE levels in cells infected with the ΔUL16B virus were below the level of detection by Western blotting, although a very small amount of gE was detected by radiolabeling followed by immunoprecipitation (data not shown). Analysis of the gE coding sequence in the ΔUL16B virus revealed no changes, and therefore, at least one other mutation must exist somewhere in this virus. Examination of the parent virus from which the ΔUL16B mutant was generated (15, 17) demonstrated a similar reduction in the level of gE expression, suggesting that the mutation responsible for this defect existed prior to the deletion of UL16. In any case, the collective results for UL11, UL21, and gE were not surprising given the growing evidence that they form a complex with UL16.

Unexpected defects for VP22.

Another tegument protein that has long been known to interact with the cytoplasmic tail of gE is VP22 (33, 35, 43). VP22 also interacts with tegument protein VP16, the product of the UL48 gene, which is essential for virus replication and egress (28, 34, 51, 52). Because the level of gE packaging was reduced for the ΔUL16S virus, the expression and packaging of VP22 and VP16 were examined. Although no substantial changes were found for VP16 (Fig. 6B), VP22 expression was reduced by 38% ± 36% and 64% ± 25% in cells infected with the ΔUL16S and ΔUL16B viruses, respectively (Fig. 6A). Moreover, the gel migration of VP22 was slowed in a manner consistent with the previously described hyperphosphorylation state (29, 53). Unexpectedly, the packaging of VP22 into virions was also found to be greatly reduced, with levels approaching only 2% that of the WT, an reduction that can only partly be attributed to the decrease in protein expression. This result was unexpected, because the packaging of VP22 is not dependent on its phosphorylation state or its ability to interact with VP16 or gE (20, 34, 43, 53). In fact, deletion of the cytoplasmic tail of gE had no effect on the packaging of VP22 into the virus (Fig. 6C), as has been reported previously (20). Thus, VP22 appears to be highly dependent on UL16, although there have been no reports of an interaction (direct or indirect) between these two tegument proteins. This was investigated (see below), but before such investigation, it was essential to ascertain whether the defects we observed were due to the loss of the UL16 protein or were an unintentional consequence of a large deletion altering the expression of nearby genes.

cis- and trans-Complementation of ΔUL16 mutants.

In the making of HSV mutations, other, unwanted changes sometimes occur, as was found for the ΔUL16B mutant (see above). Worries about inadvertent effects are compounded by the fact that UL16 is located very near to the UL13 gene, which encodes a kinase that has been shown to modify VP22 (54–56). To test the possibility that unintended changes are responsible for the ΔUL16S phenotype, two different approaches were used. The first was to infect G5 cells, which contain a section of the HSV-1 genome spanning the region from UL16 through UL21 (57). To confirm that G5 cells can express UL16, they were infected with either the WT, ΔUL16S, or ΔUL16B viruses (Fig. 7A). UL16 was absent in control Vero cells, as expected, but it was also below the level of detection of simple immunoblot assays in infected G5 cells. Fortunately, UL16 was readily detected when the protein was concentrated by immunoprecipitation (Fig. 7A). Despite the low levels of UL16 expression, G5 cells were able to partially restore the composition of ΔUL16S virions (Fig. 7B). In particular, gE, UL21, VP22, and UL11 were readily detected (compare Fig. 7B and 6A). Moreover, VP22 no longer exhibited the slower-migrating species seen in the lysates from noncomplementing cells. In stark contrast, the only change observed for the ΔUL16B mutant in complementing cells was increased packaging of UL21, which provides additional evidence for an unidentified secondary mutation. Surprisingly, G5 cells were able to fully restore the titers of both UL16-null viruses, as measured in one-step growth curves (Fig. 8A), but the plaques produced by the ΔUL16B mutant remained small (Fig. 8B), providing still more evidence for a secondary mutation(s).

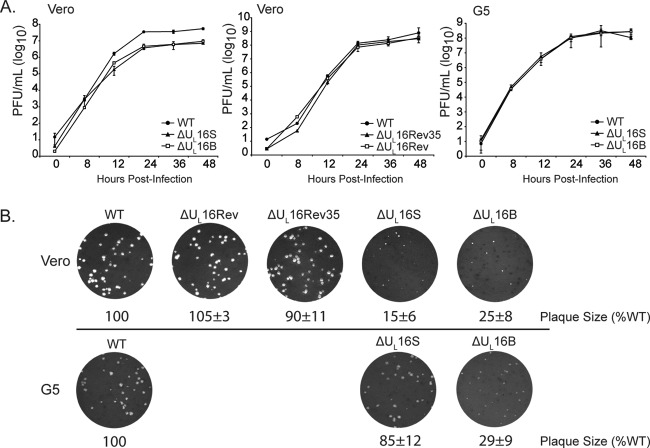

FIG 8.

Growth properties of complemented ΔUL16 viruses. (A) Cultures of Vero or G5 cells were infected with the indicated viruses at an MOI of 1. At various times after infection, the total amount of virus present in the cells and medium (combined) was measured by plaque assays on Vero cells. Measurements from three independent experiments were made, and the error bars represent standard errors of the means. (B) Vero or G5 cells were infected with dilutions of the indicated viruses and were overlaid with methylcellulose. Four days postinfection, the cells were fixed and stained, and plaque sizes relative to those of the wild-type virus were measured. Representative plates from three independent experiments are shown.

The second way in which the ΔUL16S mutant was analyzed for the presence of unintended alterations was to generate two revertant viruses (Fig. 1). The ΔUL16Rev virus is a true revertant in which the missing gene has been reinserted at its native position. In contrast, the ΔUL16Rev35 virus retains the original deletion but has the UL16 coding sequence inserted in the place of the nonessential UL35 gene. Except for a 5-fold increase in the expression of UL16 from the more-active UL35 promoter (12, 58), the two revertant viruses behaved like the WT with regard to their expression and packaging of viral proteins (Fig. 6A and B), one-step growth curves (Fig. 8A), and plaque size (Fig. 8B).

Electron microscopy was used to see whether the cis- or trans-complemented viruses produce multicapsid virions. No abnormal particles were found in G5 cells infected with either the ΔUL16S or ΔUL16B mutant, and none were seen in Vero cells infected with the ΔUL16Rev or ΔUL16Rev35 virus (data not shown). Taken together, all the complementation results demonstrate that the defects in viral replication observed for the ΔUL16S mutant—including the defects in VP22 migration and virion packaging—are due solely to the absence of the UL16 protein.

Interaction of UL16 with VP22.

The striking changes observed for VP22 when UL16 was absent suggested the possibility that these two tegument proteins interact. As a first step, the UL49 gene was deleted to create a VP22-null mutant (Fig. 1, ΔVP22) in order to see whether it would be capable of packaging UL16. Additionally, a true revertant (the ΔVP22Rev strain) was generated to control for any mutations that may have arisen during the recombination process. Previous studies have shown that viruses lacking VP22 replicate poorly and produce small plaques because unregulated VHS leads to altered protein expression (36, 37), and this was true for the mutant reported here (data not shown). However, although decreases in both gE and VP16 packaging were observed, the absence of VP22 did not affect the expression or packaging of UL16 (Fig. 9). Thus, it appears that VP22 and UL16 have nonreciprocal packaging requirements (i.e., VP22 is dependent on UL16, but not vice versa), as is the case for VP22 and gE (i.e., VP22 is not dependent on gE, but gE is dependent on VP22).

To look more directly for an interaction between UL16 and VP22, cotransfection assays were used. This method is based on the ability of VP22 to accumulate on microtubules (59–62). As a positive control, green fluorescent protein-tagged VP22 (VP22-GFP) was coexpressed with its known binding partner gE. As expected, in cells where VP22-GFP-marked filaments were found, gE was found to colocalize (Fig. 10A). In the test experiment, VP22 was tagged with an epitope from hemagglutinin (HA), and UL16 was tagged with GFP. When these two proteins were coexpressed, no colocalization was observed (Fig. 10B, top row); however, this was not a surprise. UL16 has been shown to be a regulated protein with an N-terminal domain (NTD; residues 1 to 155) that contains binding activities and a C-terminal domain (CTD; residues 156 to 373) that negatively regulates binding. Consequently, the full-length form of UL16 interacts poorly with UL11 and gE unless the CTD is removed (6, 9). Therefore, each portion of UL16 was individually cotransfected with VP22.HA. As expected, the CTD-GFP construct did not interact with VP22.HA (Fig. 10B, middle row), but the NTD-GFP construct did (bottom row). This suggests that the NTD of UL16 contains the VP22-binding activity, and we presume that it is normally induced when other viral proteins are present. For example, binding of UL21 to full-length UL16 has been shown to enable the UL11 interaction, but UL21 did not stimulate the UL16-VP22 interaction in this study (data not shown) or the interaction with gE (4). Moreover, several amino acid substitutions in the CTD of full-length UL16 have been shown to activate binding to UL11 in the absence of UL21, but these do not activate binding to VP22 (data not shown) or to gE (6). Nevertheless, the data provided in this report strongly support the hypothesis that UL16 and VP22 can interact in the absence of any other viral proteins, adding yet another member to this growing, but poorly understood, network of UL16 binding partners.

DISCUSSION

HSV-1 assembly brings together 6 capsid proteins, approximately 20 tegument proteins, and 15 membrane proteins (1–3) to create molecular machinery with moving parts that are precisely positioned and regulated to enable many difficult tasks, such as virus entry, delivery of the genome to the nucleus, cell-to-cell spread, and a reverse-signaling event that causes the tegument to be rearranged when the virus binds to its attachment receptors (16). Moreover, this machinery is adjustable, allowing the virus to meet the distinct challenges of replicating in both epithelial and neuronal cells during the course of its propagation from one individual to another (63). This complexity presents a daunting task to those who seek to elucidate how this machinery is put together and how it works. Here, two novel observations have been made regarding HSV assembly and the role of the tegument protein UL16.

The UL16–VP22 interaction.

The observation that virion packaging of VP22 is dependent on UL16 was unexpected. Indeed, VP22 packaging was found to be far more dependent on UL16 than on its other binding partners, gE (20, 64) and VP16 (34). This finding then led to the discovery, reported here, that these two molecules can interact in the absence of other viral proteins. In retrospect, it is interesting that in our original search for UL11 binding partners (7), we found variable data to suggest that a small amount of VP22 was obtained in the glutathione S-transferase (GST) pulldown experiments, but we reported only the most abundant and robust binding partner, UL16. Another hint for the interaction was provided by the reduction in the level of VP22 packaging seen when UL11 is absent, which presumably is due to the concomitant failure to package UL16 (20), since it is now quite clear that VP22 packaging does not require gE (20), as confirmed here. Also, the slower-migrating, apparently hyperphosphorylated forms of VP22 found in the absence of UL16 are also found in the absence of UL11 or the cytoplasmic tail of gE (20), providing further evidence that all these proteins work together in a complex. However, the discovery of the UL16–VP22 interaction offers no particular insight on how any of the viral machinery actually works. Rather, these findings emphasize how little is known about the parts and how they fit together.

Functions for UL16 in cytoplasmic envelopment.

The experiments described here show that the obstacle to virion production in the absence of UL16 is encountered after capsids reach cytoplasmic membranes for envelopment. Specifically, it appears that the rate of capsid wrapping is low, leading to the presence of multicapsid virions and a large percentage of membrane-associated, but incomplete, virions. The absence of capsid clusters at positions distant from membranes suggests that individual capsids are sequentially delivered to sites of envelopment, where they are occasionally wrapped as a bundle. This process differs greatly from that observed for the multicapsid virions of gK mutants, which appear to arise by self-fusion of singly enveloped virions within a cytoplasmic vesicle (65, 66). In those cases, groups of capsids being enveloped simultaneously were not reported. Thus, the findings presented here are consistent with the hypothesis that a bridging function is provided by the UL11–UL16 interaction, with weaker ties between the capsid and the membrane making the wrapping process more difficult.

In seeming contradiction to the bridging hypothesis, the ΔUL16 phenotype has not been observed for mutants that lack UL11. In that case, capsids accumulate free from membranes (reference 18 and data not shown). There are two ways to reconcile this discrepancy within the bridging hypothesis. First, UL16 has been shown to be associated with cytoplasmic capsids (10), and it may be that the unoccupied, possibly hydrophobic sites that are exposed when this tegument protein is absent result in capsids that are sticky. If so, then capsids would cluster only at cytoplasmic sites where they come together, such as after their individual transport to the membrane. Thus, no clustering would be observed in the absence of UL11, because UL16 would be present on the capsids to occupy the sticky sites.

A second possible explanation for the discrepancy between the ΔUL16 and ΔUL11 phenotypes is based on the observation that massive disruptions of tegument protein complexes occur when individual components are missing (12, 31, 47–50). The present study provides another clear example of this; namely, when UL16 is absent, the packaging of UL11, VP22, and gE is defective. This massive disruption in the molecular machinery could produce delays in capsid envelopment even if the UL11–UL16 interaction itself does not provide a bridging function. On the other hand, in the time since the bridging hypothesis was first put forth, UL16 has been discovered to have a second binding partner on the membrane, gE (9); moreover, UL11 and gE have been shown to interact (20). Consequently, it is difficult to sort out which interaction with UL16 is more important. In any case, it is quite clear that the primary block to envelopment observed in the absence of UL16 occurs after capsids arrive at the membrane.

Although the presumed bridging function(s) of UL16 is easy to envision, there is another, very different possibility for the role of UL16. This hypothesis is based on a similarity between UL16 and E. coli Hsp33, a chaperone protein that becomes active only when cells are under oxidative stress (67). Like UL16, Hsp33 has two primary domains. The chaperone activity is located in the N-terminal domain, while the C-terminal domain provides a negative regulatory function. Under oxidizing conditions, a zinc finger provided by four cysteine residues in the regulatory domain is lost, as two disulfide bonds are formed, and the resulting change in conformation activates the chaperone activity (68, 69). The zinc finger motif of Hsp33 is not found in eukaryotic proteins (70) but is similar to a cysteine motif in the regulatory domain of UL16 (6). Moreover, it is known that HSV infections induce and require oxidative stress for the production of infectious virions (71–78). But unlike those of Hsp33, the binding activities of the N-terminal portion of UL16 seem to be specific for particular viral proteins: UL11 (6), gE (9), and VP22 (this study). With these observations in mind, it has been proposed that UL16 might serve as a virus-specific chaperone rather than simply providing bridging interactions (6). This hypothesis is consistent with the observation made here that G5 cells can fully complement the ΔUL16S mutation, even though the amount of UL16 produced is below the level of detection by normal Western blotting methods. That is, only a small amount of UL16 might be needed to move from one binding partner to another as it helps weave together the structure of the virion. The need for such a chaperone activity seems likely given the very large number of proteins that must come together to create the complex machinery of the virion. In any case, the reduced packaging of UL16 binding partners into ΔUL16S virions from G5 cells is likely due to the limiting amount of this tegument protein available.

The UL16 chaperone hypothesis might also explain the difference in the location of the block to capsid egress between HSV (at the membrane) and human cytomegalovirus (23), murine cytomegalovirus (24), and murine gammaherpesvirus 68 (13), all of which have blocks prior to the transport of their capsids to membranes and are noninfectious as a result. In particular, these viruses may be more dependent on their UL16 homologs for the assembly of tegument proteins onto capsids than is HSV; if so, the misarranged molecules may obscure the sequences that are needed for transport to the membrane. Moreover, this hypothetical difficulty in assembly might explain why the UL16 homologs of beta- and gammaherpesviruses remain stably bound to capsids when their virions are disrupted with NP-40 (14, 79, 80), whereas the UL16 proteins of alphaherpesviruses do not (10, 16). Clearly, further studies of these complex tegument proteins are needed in order to sort out their important functions in the replication of herpesviruses.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank our coworker Carol B. Wilson for help and encouragement, Roland Myers and Thomas Abraham (Microscopy Imaging Facility, PSU College of Medicine) for expertise, technical skills, and advice, and Anne Stanley (Macromolecular Synthesis Facility, Pennsylvania State University College of Medicine) for generating the oligonucleotide primers used in this study. We also thank Richard Courtney (Pennsylvania State University College of Medicine), Craig Meyers (Pennsylvania State University College of Medicine), Prashant Desai (Johns Hopkins University), Joel Baines (Cornell University), and Harvey Friedman (University of Pennsylvania) for their generosity in providing the reagents necessary to complete this study.

This study was supported by a National Institutes of Health grant to J.W.W. (AI071286). J.L.S. was supported in part by a training grant from the NIH (T32 CA60395).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 16 October 2013

REFERENCES

- 1.Johnson DC, Baines JD. 2011. Herpesviruses remodel host membranes for virus egress. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 9:382–394. 10.1038/nrmicro2559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kelly BJ, Fraefel C, Cunningham AL, Diefenbach RJ. 2009. Functional roles of the tegument proteins of herpes simplex virus type 1. Virus Res. 145:173–186. 10.1016/j.virusres.2009.07.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mettenleiter TC, Klupp BG, Granzow H. 2009. Herpesvirus assembly: an update. Virus Res. 143:222–234. 10.1016/j.virusres.2009.03.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Han J, Chadha P, Starkey JL, Wills JW. 2012. Function of glycoprotein E of herpes simplex virus requires coordinated assembly of three tegument proteins on its cytoplasmic tail. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 109:19798–19803. 10.1073/pnas.1212900109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harper AL, Meckes DG, Jr, Marsh JA, Ward MD, Yeh PC, Baird NL, Wilson CB, Semmes OJ, Wills JW. 2010. Interaction domains of the UL16 and UL21 tegument proteins of herpes simplex virus. J. Virol. 84:2963–2971. 10.1128/JVI.02015-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chadha P, Han J, Starkey JL, Wills JW. 2012. Regulated interaction of tegument proteins UL16 and UL11 from herpes simplex virus. J. Virol. 86:11886–11898. 10.1128/JVI.01879-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Loomis JS, Courtney RJ, Wills JW. 2003. Binding partners for the UL11 tegument protein of herpes simplex virus type 1. J. Virol. 77:11417–11424. 10.1128/JVI.77.21.11417-11424.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yeh PC, Meckes DG, Jr., Wills JW. 2008. Analysis of the interaction between the UL11 and UL16 tegument proteins of herpes simplex virus. J. Virol. 82:10693–10700. 10.1128/JVI.01230-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yeh PC, Han J, Chadha P, Meckes DG, Jr, Ward MD, Semmes OJ, Wills JW. 2011. Direct and specific binding of the UL16 tegument protein of herpes simplex virus to the cytoplasmic tail of glycoprotein E. J. Virol. 85:9425–9436. 10.1128/JVI.05178-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meckes DG, Jr., Wills JW. 2007. Dynamic interactions of the UL16 tegument protein with the capsid of herpes simplex virus. J. Virol. 81:13028–13036. 10.1128/JVI.01306-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meckes DG, Jr, Marsh JA, Wills JW. 2010. Complex mechanisms for the packaging of the UL16 tegument protein into herpes simplex virus. Virology 398:208–213. 10.1016/j.virol.2009.12.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baird NL, Starkey JL, Hughes DJ, Wills JW. 2010. Myristylation and palmitylation of HSV-1 UL11 are not essential for its function. Virology 397:80–88. 10.1016/j.virol.2009.10.046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guo H, Wang L, Peng L, Zhou ZH, Deng H. 2009. Open reading frame 33 of a gammaherpesvirus encodes a tegument protein essential for virion morphogenesis and egress. J. Virol. 83:10582–10595. 10.1128/JVI.00497-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wing BA, Lee GC, Huang ES. 1996. The human cytomegalovirus UL94 open reading frame encodes a conserved herpesvirus capsid/tegument-associated virion protein that is expressed with true late kinetics. J. Virol. 70:3339–3345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baines JD, Roizman B. 1991. The open reading frames UL3, UL4, UL10, and UL16 are dispensable for the replication of herpes simplex virus 1 in cell culture. J. Virol. 65:938–944 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meckes DG, Jr., Wills JW. 2008. Structural rearrangement within an enveloped virus upon binding to the host cell. J. Virol. 82:10429–10435. 10.1128/JVI.01223-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nalwanga D, Rempel S, Roizman B, Baines JD. 1996. The UL 16 gene product of herpes simplex virus 1 is a virion protein that colocalizes with intranuclear capsid proteins. Virology 226:236–242. 10.1006/viro.1996.0651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baines JD, Roizman B. 1992. The UL11 gene of herpes simplex virus 1 encodes a function that facilitates nucleocapsid envelopment and egress from cells. J. Virol. 66:5168–5174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dingwell KS, Brunetti CR, Hendricks RL, Tang Q, Tang M, Rainbow AJ, Johnson DC. 1994. Herpes simplex virus glycoproteins E and I facilitate cell-to-cell spread in vivo and across junctions of cultured cells. J. Virol. 68:834–845 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Han J, Chadha P, Meckes DG, Jr, Baird NL, Wills JW. 2011. Interaction and interdependent packaging of tegument protein UL11 and glycoprotein E of herpes simplex virus. J. Virol. 85:9437–9446. 10.1128/JVI.05207-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Saldanha CE, Lubinski J, Martin C, Nagashunmugam T, Wang L, van Der Keyl H, Tal-Singer R, Friedman HM. 2000. Herpes simplex virus type 1 glycoprotein E domains involved in virus spread and disease. J. Virol. 74:6712–6719. 10.1128/JVI.74.15.6712-6719.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang F, Tang W, McGraw HM, Bennett J, Enquist LW, Friedman HM. 2005. Herpes simplex virus type 1 glycoprotein E is required for axonal localization of capsid, tegument, and membrane glycoproteins. J. Virol. 79:13362–13372. 10.1128/JVI.79.21.13362-13372.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Phillips SL, Bresnahan WA. 2012. The human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) tegument protein UL94 Is essential for secondary envelopment of HCMV virions. J. Virol. 86:2523–2532. 10.1128/JVI.06548-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maninger S, Bosse JB, Lemnitzer F, Pogoda M, Mohr CA, von Einem J, Walther P, Koszinowski UH, Ruzsics Z. 2011. M94 is essential for the secondary envelopment of murine cytomegalovirus. J. Virol. 85:9254–9267. 10.1128/JVI.00443-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Klupp BG, Bottcher S, Granzow H, Kopp M, Mettenleiter TC. 2005. Complex formation between the UL16 and UL21 tegument proteins of pseudorabies virus. J. Virol. 79:1510–1522. 10.1128/JVI.79.3.1510-1522.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Elliott GD, Meredith DM. 1992. The herpes simplex virus type 1 tegument protein VP22 is encoded by gene UL49. J. Gen. Virol. 73(Part 3):723–726. 10.1099/0022-1317-73-3-723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chi JH, Harley CA, Mukhopadhyay A, Wilson DW. 2005. The cytoplasmic tail of herpes simplex virus envelope glycoprotein D binds to the tegument protein VP22 and to capsids. J. Gen. Virol. 86:253–261. 10.1099/vir.0.80444-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Elliott G, Mouzakitis G, O'Hare P. 1995. VP16 interacts via its activation domain with VP22, a tegument protein of herpes simplex virus, and is relocated to a novel macromolecular assembly in coexpressing cells. J. Virol. 69:7932–7941 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Elliott G, O'Reilly D, O'Hare P. 1999. Identification of phosphorylation sites within the herpes simplex virus tegument protein VP22. J. Virol. 73:6203–6206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Elliott G, O'Hare P. 2000. Cytoplasm-to-nucleus translocation of a herpesvirus tegument protein during cell division. J. Virol. 74:2131–2141. 10.1128/JVI.74.5.2131-2141.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Elliott G, Hafezi W, Whiteley A, Bernard E. 2005. Deletion of the herpes simplex virus VP22-encoding gene (UL49) alters the expression, localization, and virion incorporation of ICP0. J. Virol. 79:9735–9745. 10.1128/JVI.79.15.9735-9745.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Farnsworth A, Wisner TW, Johnson DC. 2007. Cytoplasmic residues of herpes simplex virus glycoprotein gE required for secondary envelopment and binding of tegument proteins VP22 and UL11 to gE and gD. J. Virol. 81:319–331. 10.1128/JVI.01842-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maringer K, Stylianou J, Elliott G. 2012. A network of protein interactions around the herpes simplex virus tegument protein VP22. J. Virol. 86:12971–12982. 10.1128/JVI.01913-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.O'Regan KJ, Murphy MA, Bucks MA, Wills JW, Courtney RJ. 2007. Incorporation of the herpes simplex virus type 1 tegument protein VP22 into the virus particle is independent of interaction with VP16. Virology 369:263–280. 10.1016/j.virol.2007.07.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.O'Regan KJ, Bucks MA, Murphy MA, Wills JW, Courtney RJ. 2007. A conserved region of the herpes simplex virus type 1 tegument protein VP22 facilitates interaction with the cytoplasmic tail of glycoprotein E (gE). Virology 358:192–200. 10.1016/j.virol.2006.08.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Duffy C, Mbong EF, Baines JD. 2009. VP22 of herpes simplex virus 1 promotes protein synthesis at late times in infection and accumulation of a subset of viral mRNAs at early times in infection. J. Virol. 83:1009–1017. 10.1128/JVI.02245-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mbong EF, Woodley L, Dunkerley E, Schrimpf JE, Morrison LA, Duffy C. 2012. Deletion of the herpes simplex virus 1 UL49 gene results in mRNA and protein translation defects that are complemented by secondary mutations in UL41. J. Virol. 86:12351–12361. 10.1128/JVI.01975-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Person S, Desai P. 1998. Capsids are formed in a mutant virus blocked at the maturation site of the UL26 and UL26.5 open reading frames of herpes simplex virus type 1 but are not formed in a null mutant of UL38 (VP19C). Virology 242:193–203. 10.1006/viro.1997.9005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gierasch WW, Zimmerman DL, Ward SL, Vanheyningen TK, Romine JD, Leib DA. 2006. Construction and characterization of bacterial artificial chromosomes containing HSV-1 strains 17 and KOS. J. Virol. Methods 135:197–206. 10.1016/j.jviromet.2006.03.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Warming S, Costantino N, Court DL, Jenkins NA, Copeland NG. 2005. Simple and highly efficient BAC recombineering using galK selection. Nucleic Acids Res. 33:e36. 10.1093/nar/gni035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McNabb DS, Courtney RJ. 1992. Characterization of the large tegument protein (ICP1/2) of herpes simplex virus type 1. Virology 190:221–232. 10.1016/0042-6822(92)91208-C [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lin X, Lubinski JM, Friedman HM. 2004. Immunization strategies to block the herpes simplex virus type 1 immunoglobulin G Fc receptor. J. Virol. 78:2562–2571. 10.1128/JVI.78.5.2562-2571.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.O'Regan KJ, Brignati MJ, Murphy MA, Bucks MA, Courtney RJ. 2010. Virion incorporation of the herpes simplex virus type 1 tegument protein VP22 is facilitated by trans-Golgi network localization and is independent of interaction with glycoprotein E. Virology 405:176–192. 10.1016/j.virol.2010.06.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Desai PJ. 2000. A null mutation in the UL36 gene of herpes simplex virus type 1 results in accumulation of unenveloped DNA-filled capsids in the cytoplasm of infected cells. J. Virol. 74:11608–11618. 10.1128/JVI.74.24.11608-11618.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chong KT, Mims CA. 1981. Murine cytomegalovirus particle types in relation to sources of virus and pathogenicity. J. Gen. Virol. 57:415–419. 10.1099/0022-1317-57-2-415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hudson JB, Misra V, Mosmann TR. 1976. Properties of the multicapsid virions of murine cytomegalovirus. Virology 72:224–234. 10.1016/0042-6822(76)90325-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Michael K, Bottcher S, Klupp BG, Karger A, Mettenleiter TC. 2006. Pseudorabies virus particles lacking tegument proteins pUL11 or pUL16 incorporate less full-length pUL36 than wild-type virus, but specifically accumulate a pUL36 N-terminal fragment. J. Gen. Virol. 87:3503–3507. 10.1099/vir.0.82168-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Michael K, Klupp BG, Mettenleiter TC, Karger A. 2006. Composition of pseudorabies virus particles lacking tegument protein US3, UL47, or UL49 or envelope glycoprotein E. J. Virol. 80:1332–1339. 10.1128/JVI.80.3.1332-1339.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Michael K, Klupp BG, Karger A, Mettenleiter TC. 2007. Efficient incorporation of tegument proteins pUL46, pUL49, and pUS3 into pseudorabies virus particles depends on the presence of pUL21. J. Virol. 81:1048–1051. 10.1128/JVI.01801-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhang Y, McKnight JL. 1993. Herpes simplex virus type 1 UL46 and UL47 deletion mutants lack VP11 and VP12 or VP13 and VP14, respectively, and exhibit altered viral thymidine kinase expression. J. Virol. 67:1482–1492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mossman KL, Sherburne R, Lavery C, Duncan J, Smiley JR. 2000. Evidence that herpes simplex virus VP16 is required for viral egress downstream of the initial envelopment event. J. Virol. 74:6287–6299. 10.1128/JVI.74.14.6287-6299.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Weinheimer SP, Boyd BA, Durham SK, Resnick JL, O'Boyle DR. 1992. Deletion of the VP16 open reading frame of herpes simplex virus type 1. J. Virol. 66:258–269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Potel C, Elliott G. 2005. Phosphorylation of the herpes simplex virus tegument protein VP22 has no effect on incorporation of VP22 into the virus but is involved in optimal expression and virion packaging of ICP0. J. Virol. 79:14057–14068. 10.1128/JVI.79.22.14057-14068.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Asai R, Ohno T, Kato A, Kawaguchi Y. 2007. Identification of proteins directly phosphorylated by UL13 protein kinase from herpes simplex virus 1. Microbes Infect. 9:1434–1438. 10.1016/j.micinf.2007.07.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Geiss BJ, Cano GL, Tavis JE, Morrison LA. 2004. Herpes simplex virus 2 VP22 phosphorylation induced by cellular and viral kinases does not influence intracellular localization. Virology 330:74–81. 10.1016/j.virol.2004.08.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mouzakitis G, McLauchlan J, Barreca C, Kueltzo L, O'Hare P. 2005. Characterization of VP22 in herpes simplex virus-infected cells. J. Virol. 79:12185–12198. 10.1128/JVI.79.19.12185-12198.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Desai P, DeLuca NA, Glorioso JC, Person S. 1993. Mutations in herpes simplex virus type 1 genes encoding VP5 and VP23 abrogate capsid formation and cleavage of replicated DNA. J. Virol. 67:1357–1364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Desai P, DeLuca NA, Person S. 1998. Herpes simplex virus type 1 VP26 is not essential for replication in cell culture but influences production of infectious virus in the nervous system of infected mice. Virology 247:115–124. 10.1006/viro.1998.9230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Elliott G, O'Hare P. 1997. Intercellular trafficking and protein delivery by a herpesvirus structural protein. Cell 88:223–233. 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81843-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Elliott G, O'Hare P. 1998. Herpes simplex virus type 1 tegument protein VP22 induces the stabilization and hyperacetylation of microtubules. J. Virol. 72:6448–6455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yedowitz JC, Kotsakis A, Schlegel EF, Blaho JA. 2005. Nuclear localizations of the herpes simplex virus type 1 tegument proteins VP13/14, vhs, and VP16 precede VP22-dependent microtubule reorganization and VP22 nuclear import. J. Virol. 79:4730–4743. 10.1128/JVI.79.8.4730-4743.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Martin A, O'Hare P, McLauchlan J, Elliott G. 2002. Herpes simplex virus tegument protein VP22 contains overlapping domains for cytoplasmic localization, microtubule interaction, and chromatin binding. J. Virol. 76:4961–4970. 10.1128/JVI.76.10.4961-4970.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Smith G. 2012. Herpesvirus transport to the nervous system and back again. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 66:153–176. 10.1146/annurev-micro-092611-150051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Duffy C, Lavail JH, Tauscher AN, Wills EG, Blaho JA, Baines JD. 2006. Characterization of a UL49-null mutant: VP22 of herpes simplex virus type 1 facilitates viral spread in cultured cells and the mouse cornea. J. Virol. 80:8664–8675. 10.1128/JVI.00498-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Foster TP, Melancon JM, Baines JD, Kousoulas KG. 2004. The herpes simplex virus type 1 UL20 protein modulates membrane fusion events during cytoplasmic virion morphogenesis and virus-induced cell fusion. J. Virol. 78:5347–5357. 10.1128/JVI.78.10.5347-5357.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hutchinson L, Johnson DC. 1995. Herpes simplex virus glycoprotein K promotes egress of virus particles. J. Virol. 69:5401–5413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mayer MP. 2012. The unfolding story of a redox chaperone. Cell 148:843–844. 10.1016/j.cell.2012.02.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Graumann J, Lilie H, Tang X, Tucker KA, Hoffmann JH, Vijayalakshmi J, Saper M, Bardwell JC, Jakob U. 2001. Activation of the redox-regulated molecular chaperone Hsp33—a two-step mechanism. Structure 9:377–387. 10.1016/S0969-2126(01)00599-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ilbert M, Horst J, Ahrens S, Winter J, Graf PC, Lilie H, Jakob U. 2007. The redox-switch domain of Hsp33 functions as dual stress sensor. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 14:556–563. 10.1038/nsmb1244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Jakob U, Eser M, Bardwell JC. 2000. Redox switch of hsp33 has a novel zinc-binding motif. J. Biol. Chem. 275:38302–38310. 10.1074/jbc.M005957200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Fraternale A, Paoletti MF, Casabianca A, Nencioni L, Garaci E, Palamara AT, Magnani M. 2009. GSH and analogs in antiviral therapy. Mol. Aspects Med. 30:99–110. 10.1016/j.mam.2008.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gonzalez-Dosal R, Horan KA, Rahbek SH, Ichijo H, Chen ZJ, Mieyal JJ, Hartmann R, Paludan SR. 2011. HSV infection induces production of ROS, which potentiate signaling from pattern recognition receptors: role for S-glutathionylation of TRAF3 and 6. PLoS Pathog. 7:e1002250. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kavouras JH, Prandovszky E, Valyi-Nagy K, Kovacs SK, Tiwari V, Kovacs M, Shukla D, Valyi-Nagy T. 2007. Herpes simplex virus type 1 infection induces oxidative stress and the release of bioactive lipid peroxidation by-products in mouse P19N neural cell cultures. J. Neurovirol. 13:416–425. 10.1080/13550280701460573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Mathew SS, Bryant PW, Burch AD. 2010. Accumulation of oxidized proteins in Herpesvirus infected cells. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 49:383–391. 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.04.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Nucci C, Palamara AT, Ciriolo MR, Nencioni L, Savini P, D'Agostini C, Rotilio G, Cerulli L, Garaci E. 2000. Imbalance in corneal redox state during herpes simplex virus 1-induced keratitis in rabbits. Effectiveness of exogenous glutathione supply. Exp. Eye Res. 70:215–220. 10.1006/exer.1999.0782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Palamara AT, Perno CF, Ciriolo MR, Dini L, Balestra E, D'Agostini C, Di Francesco P, Favalli C, Rotilio G, Garaci E. 1995. Evidence for antiviral activity of glutathione: in vitro inhibition of herpes simplex virus type 1 replication. Antiviral Res. 27:237–253. 10.1016/0166-3542(95)00008-A [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Schachtele SJ, Hu S, Little MR, Lokensgard JR. 2010. Herpes simplex virus induces neural oxidative damage via microglial cell Toll-like receptor-2. J. Neuroinflammation 7:35. 10.1186/1742-2094-7-35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Vogel JU, Cinatl J, Dauletbaev N, Buxbaum S, Treusch G, Cinatl J, Jr, Gerein V, Doerr HW. 2005. Effects of S-acetylglutathione in cell and animal model of herpes simplex virus type 1 infection. Med. Microbiol. Immunol. 194:55–59. 10.1007/s00430-003-0212-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Johannsen E, Luftig M, Chase MR, Weicksel S, Cahir-McFarland E, Illanes D, Sarracino D, Kieff E. 2004. Proteins of purified Epstein-Barr virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 101:16286–16291. 10.1073/pnas.0407320101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Zhu FX, Chong JM, Wu L, Yuan Y. 2005. Virion proteins of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus. J. Virol. 79:800–811. 10.1128/JVI.79.2.800-811.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]