Abstract

Purpose

The primary objective was to evaluate safety of 3-(1’-hexyloxyethyl)pyropheophorbide-a (HPPH) photodynamic therapy (HPPH-PDT) for dysplasia and early squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck (HNSCC). Secondary objectives were the assessment of treatment response and reporters for an effective PDT reaction.

Experimental Design

Patients with histologically proven oral dysplasia, carcinoma in situ (CiS ) or early stage HNSCC were enrolled in two sequentially conducted dose escalation studies with an expanded cohort at the highest dose level. These studies employed an HPPH dose of 4 mg/m2 and light doses from 50 to 140 J/cm2. Pathologic tumor responses were assessed at 3 months. Clinical follow up range was 5 to 40 months. PDT induced cross-linking of signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) were assessed as potential indicators of PDT effective reaction.

Results

Forty patients received HPPH-PDT. Common adverse events were pain and treatment site edema. Biopsy proven complete response rates were 46% for dysplasia and CiS, and 82% for SCCs lesions at 140 J/cm2. The responses in the CiS/dysplasia cohort are not durable. The PDT induced STAT3 cross-links is significantly higher (P=0.0033) in SCC than in CiS/dysplasia for all light-doses.

Conclusion

HPPH-PDT is safe for the treatment of CiS/dysplasia and early stage cancer of the oral cavity. Early stage oral HNSCC appears to respond better to HPPH-PDT in comparison to premalignant lesions. The degree of STAT3 cross-linking is a significant reporter to evaluate HPPH-PDT mediated photoreaction.

Introduction

The Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) report that the incidence rates of cancer of the oral cavity is 5.7 per 100,000 in the US (1). In India the incidence rate is as high as 20 per 100,000 population (2). Every year, more than 17,000 new cases of lip and oral cavity cancer are diagnosed in the United States.

Surgery and radiotherapy are the standard treatment modalities for T1 squamous cells carcinoma (SCC) of the oral cavity (3). Several studies demonstrated that surgery is the preferred treatment for these tumors, yielding superior 5-Year survival rates when compared to radiation therapy (3, 4). However, effective surgical treatment requires wide local resection of the primary tumor with clear surgical margins. In order to secure tumor free margins, excision of adjacent normal functional tissue is performed, often affecting speech and swallow function. On the other hand, radiation therapy can induce significant treatment-related adverse events (AEs) such as xerostomia, chronic dental decay and risk of mandibular osteonecrosis, which remain long after the patient is cured ,and has shown to reduce patients’ quality of life (QoL)(5). Patients who are cured with standard therapies also have a significant life-long risk of developing second primary tumors in the oral cavity, which has been associated with poor prognosis (6–8). Although patients with superficially invasive tumors (equal or less than 4 mm in thickness) have a relatively low risk for local recurrence and metastasis (9–11), the treatment options have been limited to surgery or radiation therapy. There is a need to offer these patients a curative therapy that is safe, repeatable and has no long-term toxicities.

Photodynamic therapy (PDT) is a minimally invasive treatment that involves the activation by light of a drug (photosensitizer) that generates cytotoxic reactive oxygen species, resulting in direct damage to tumor cells (12). PDT has proven to be an effective local treatment for a range of solid tumors (13). It has the potential to become an effective first line treatment modality for early stage SCC of the oral cavity because it is associated with minimal short-term side-effects, nominal scarring, and sparing of healthy vital structures such as nerves and major blood vessels (14–16). Importantly, PDT may be used with standard therapies.

The photosensitizers porfimer sodium (Photofrin®), US FDA approved for esophageal and endobronchial cancer, and mTHPC (Foscan®), approved in Europe for the palliative use in HNSCC, have shown promise for the treatment of oral cancers (17). While Photofrin® or Foscan® mediated PDT is effective, the persistence of the photosensitizer in skin necessitates protection of patients from sunlight and other sources of bright light for long periods (30 to 90 days). Given this prolonged phototoxicity, there has been widespread interest in the development of newer photosensitizers with more favorable photophysical and pharmacokinetic properties. The chlorin-based compound, 3-(1’-hexyloxyethyl) pyropheophorbide a (HPPH) is one such photosensitizer (18) that has been shown to exhibit potent antitumor activity in a number of experimental tumor models (19). Clinical studies conducted in lung and esophageal cancer patients have also revealed good responses (16, 20). We have shown that HPPH at clinically effective antitumor doses is associated with significantly reduced cutaneous photosensitivity that rapidly declines over several days (21). Additionally, we developed an approach that allows the assessment of the PDT reaction, within 48 hours, through the analysis of PDT-induced cross-linking of the signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3)(22). We have hypothesized that STAT3 cross-linking will serve as a molecular reporter for accumulated PDT dose in the treated oral lesions and have predictive value for treatment outcome. We have undertaken two Phase I dose escalation trials to test this hypothesis, to determine the safety profile of HPPH-PDT for precancerous and early staged SCC of the oral cavity, and to a gain preliminary indication of efficacy.

Materials and Methods

Study design

These are the first Phase I, dose finding, open label, non-comparative studies of HPPH-PDT in high risk dysplasias, carcinoma in situ (CiS) and SCC of the oral cavity. The trials were carried out at RPCI from April 2008 to June 2012. HPPH was used at a fixed, previously determined, dose of 4 mg/m2 administered systemically 22–26 hours before light delivery (23). The studies had identical 3+3 dose-escalation scheme with an expanded cohort at the highest light dose. This design is a special case of the A + B design described by Lin et al. 2001 (24). Rationale behind the design is nested in the assumption that both the probabilities of toxicity and efficacious response are continuous monotonic non decreasing functions of the dose. Three courses of treatment were allowed for each oral lesion, with at least 6 weeks between treatments. Patients could have more than one lesion treated. In the first trial (NCI-2010-02401) the light dose was escalated from 50 J/cm2 to 75, 100 and 125 J/cm2. A second trial (NCI-2010-01493) with amended exclusion criteria was initiated with light dose ranging from 100 to 125 and 140 J/cm2 for each course.

The primary objective was to establish the safety profile, and to determine the dose-limiting toxicity (DLT) and the maximum tolerated light dose (MTD). Secondary objectives were assessments of HPPH levels in blood and in the tumor tissue at the time of light treatment, the extent of HPPH-PDT-mediated STAT3 cross-linking in the treated tissue, and the pathological treatment response as determined by biopsy at 3 months post treatment and clinical follow-up.

Written informed consent was obtained from all patients and all protocol related procedures were approved by the RPCI Institutional Review Board and overseen by the RPCI Data and Safety Monitoring Board.

Patient selection

Patient eligibility criteria included: biopsy-proven moderate to severe dysplasia, CiS or T1 SCC of the oral cavity, tumor thickness 4 mm or less, primary or recurrent, any type of prior therapy allowed, age at least 18 years, male or non-pregnant female using medially acceptable birth control, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) score 0–2, signed informed consent.

Patients were excluded because of: T2 or greater SCC, primary tongue base tumors, porphyria or hypersensitivity to porphyrins or porphyrin-like agents, impaired hepatic alkaline phosphatase or SGOT >3 times the upper normal limits, minimal impairment of renal function (total serum bilirubin >2 mg/dl, serum creatinine > 2 mg/dl), concurrent chemotherapy or radiation therapy less than 4 weeks after the last dose of such therapies. In the second trial severe pre-existing trismus was added as exclusion criterion.

Patients underwent a pre-treatment evaluation that included history and physical examination, palpation of the index lesion, baseline biopsy that was submitted to pathological examination, performance status and laboratory studies. If clinically indicated, patients received an electrocardiography, chest x-ray and/or computed tomography (CT) scan of the neck to exclude the presence of nodal disease.

Photodynamic therapy

All patients received PDT in the operating room under general anesthesia to eliminate pain and to facilitate the collection of tissue biopsies, and the performance of non-invasive spectroscopic measurements, before and after treatment. Tissue outside the intended treatment field was shielded from the laser light. Each lesion was illuminated with light of 665 nm wavelength, delivered by a tunable dye laser via optical fibers with an in–house manufactured gradient index lens. The power output was measured with an integrating sphere. The treatment field included one to two centimeter margins around the index lesion. In patients with multi-centric disease, more than one lesion could be treated during one treatment session. However, the total area of direct light exposure did not exceed 25 cm2. Following treatment, patients were monitored in the Ambulatory Center by a physician until ready for release, or hospitalized overnight for observation if deemed advisable. All patients were given prednisone for 9 days, starting 1 day after treatment, to control swelling. Pain was treated with oral narcotics and Fentanyl patch. All patients were instructed to avoid exposure to sunlight or bright indoor light for at least 7 days by wearing protective clothing and specific sunglasses provided by the RPCI PDT Center. They were also advised to expose small areas of skin to sunlight on Day 8 for 10 minutes to detect any remaining photosensitivity.

Patient follow-up

Patients were seen at 1 week and 1 month after treatment to assess treatment-related toxicities and clinical response. At 3 months, patients had a 3 mm punch biopsy within the treated field for pathological response verification. Thereafter, patients were examined at 3–6 months intervals.

Assessments

Safety

Patients were monitored for systemic toxicity at the time of HPPH administration, laser treatment and at each follow-up visit. Safety was determined by recording the occurrence of serious AEs during the first 30 days post-treatment using the revised NCI Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) version 4.0. At each clinic visit patients were examined for local normal tissue toxicity, performance status, pain level and skin phototoxicity. All AEs and serious adverse events (SAEs) were documented as to onset and resolution date, classification of intensity, relationship to treatment, action taken and outcome. AEs and SAEs were recorded as per MedDRA coding (Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities).

Response

Responses reported here are based on the 3 months biopsy results and/or subsequent clinical observation. All biopsies were reviewed and interpreted by the study head and neck pathologist. Tumor and lesion response to therapy was graded as follows:

Complete response (CR): complete absence of visible lesion and negative biopsy, or absence of visible lesion only (1 case).

Partial response (PR): volume reduction of the lesion by 50% or more.

Stable disease (SD): all responses <PR.

Progressive disease (PD): any increase in lesion size or increase in grade of the treated lesion.

HPPH fluorescence assays

HPPH serum levels were determined based on fluorescence (18). Coagulated blood was collected within 2 hours before light treatment, in anticoagulant-free tubes and centrifuged (Centrific 228; Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA). Serum was analyzed by recording the amplitude of the fluorescence emission maximum (λex = 412 nm, λem = 670 nm) followed by baseline correction.

In vivo fluorescence spectroscopy was used to assess HPPH tissue levels at the lesion surface. The details of the clinical spectroscopy instrument and the analysis method have been described previously (25, 26). Briefly, one source-detector pair (0.8 mm separation) of a custom, optical-fiber-based probe was used for fluorescence detection and another pair (1.6 mm separation) for reflectance measurements to allow fluorescence normalization. Five independent measurements were carried out from the index lesion. The HPPH peak at ~670 nm of the normalized signal is reported as in vivo tissue fluorescence values.

STAT3 cross-linking

One 3–5 mm punch biopsy was taken from the treatment site before treatment and one immediately after completion of treatment. Biopsies were immediately transferred to the Department of Pathology, where each sample was divided in two equal parts, one was submitted for routine processing for histopathologic examination, the other was snap-frozen on dry ice and processed for determining STAT3 cross-linking. Samples were thawed on wet ice in the presence of ~ 3-fold volume of RIPA buffer containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors for 5 min and ultra-sonicated with a micro steel tipped cell disruptor (Heat Systems-Ultrasonics, Inc). The homogenate was centrifuged at 15,000 rpm. Replicate aliquots of the supernatant, containing 20 µg protein, were boiled in SDS-sample buffer and electrophoresed on a 6% SDS-polyacrylamide gels. The separated proteins were analyzed by Western blotting for STAT3 and epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) as described, previously (27, 28). Immunoblot signals for STAT3 were quantified and expressed as percent conversion of monomeric into covalently cross-linked dimeric STAT3. In a subset of patients, we also assessed PDT-induced loss of EGFR expression (28).

Statistical analysis

The data from patient populations in both trials were combined for evaluation. Statistical analyses were primarily descriptive. Calculated P values were based on the unpaired t-test, ANOVA, or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. For all tests, a P value of <0.05 was considered significant. Statistical calculations and analyses were done using GraphPad InStat (ver. 3.10; GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA). Data in Figures 2, 3 and 5 are summarized as quartile (box-and-whisker) plots. Lower box boundary=25th percentile, upper box boundary=75th percentile, solid line within box=median, dotted line within box=mean, solid dot=outlying value, upper and lower whiskers=90th and 10th percentile, respectively. Graphing and analysis were performed using SigmaPlot software (version 11.2.0.5; Systat Software, San Jose, CA)

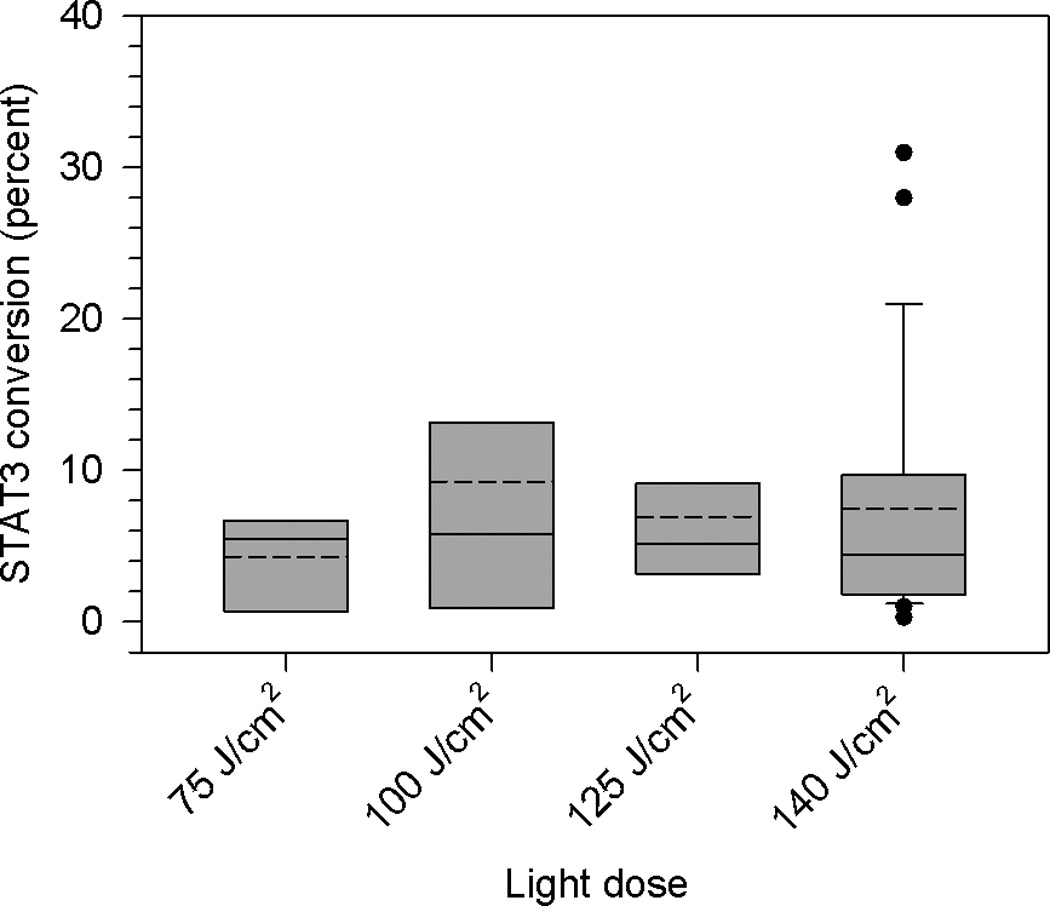

Figure 2.

Percent conversion of STAT3 monomer to cross-linked STAT3 in biopsies of dysplasia/CIS and SCC lesions obtained immediately following HPPH-PDT as a function of light dose. Data are derived from immunoblots and summarized as quartile (box-and-whisker) plots as described in Methods.

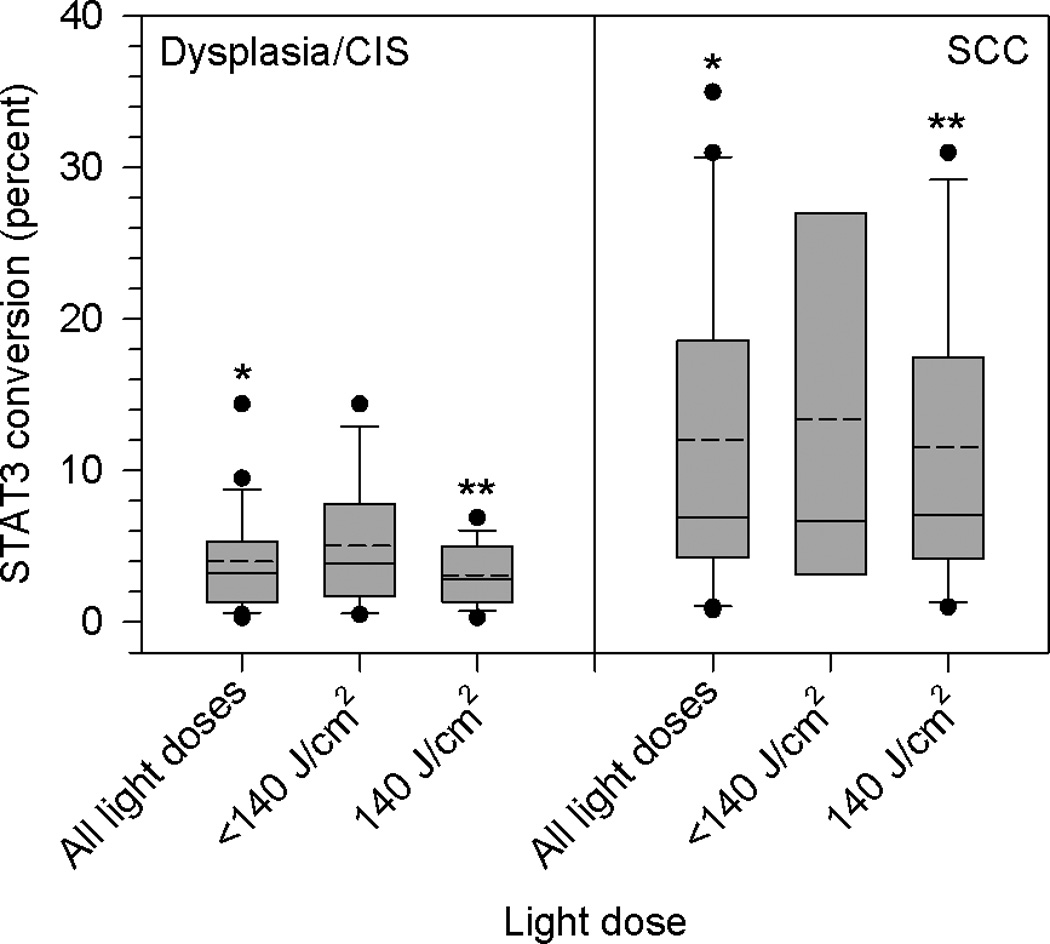

Figure 3.

Percent conversion of STAT3 monomer to cross-linked STAT3 in biopsies of dysplasia/CIS and SCC lesions obtained immediately following HPPH-PDT, grouped according to light dose. Data are derived from immunoblots and summarized as quartile (box-and-whisker) plots as described in Methods. Asterisks indicate significant differences between groups.

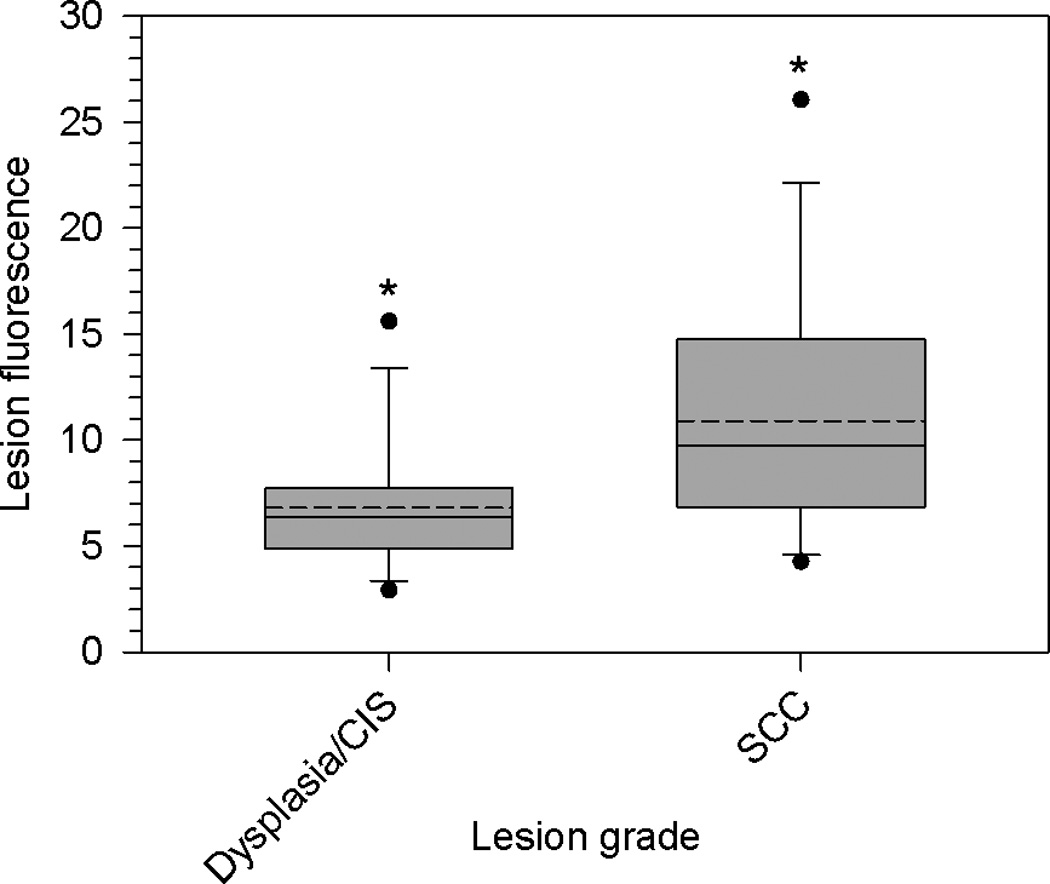

Figure 5.

HPPH fluorescence, in arbitrary units, in dysplasia/CIS and SCC lesions as determined by non-invasive fluorescence spectroscopy. Data are summarized as quartile (box-and-whisker) plots as described in Methods. Asterisks indicate significant differences between groups.

Results

Patient and lesion baseline characteristics

Details of patient and lesion characteristics are presented in Table 1. A total of 41 patients and 51 lesions were accrued, with 40 patients receiving at least one session of PDT. One patient received HPPH, but was not treated due to unrelated cardiac complications encountered during anesthesia induction. For analysis, the patients’ lesions were grouped into two categories: dysplasia and CiS, including moderate, severe dysplasia and CiS (28 lesions), and SCC, including all invasive tumors as well as CiS with microinvasion (23 lesions). In all, 5 patients presented with Lichen planus, 17 with leukoplakia and 5 with erythroplakia. Six patients had more than 1 lesion treated. Five lesions were treated twice, 1 lesion was treated 3 times. Ten patients had been previously treated; one patient with SCC and 4 patients with dysplasia/CiS had been treated with surgery alone, 1 SCC patient had received radiation and 4 SCC patients had received surgery and concurrent chemoradiotherapy.

Table 1.

Patient and lesion characteristics

| Patient characteristics | Patients ( N = 41a) |

| Median age (range) | 65 (39–88) |

| Male/female | 28/13 |

| Smoking history | |

| Non-smoker | 7b |

| Former smoker | 22 |

| Smoker | 12 |

| Prior treatment | |

| Surgery | |

| Dysplasia/CIS | 4 |

| SCC | 1 |

| Radiation | |

| SCC | 1 |

| Surgery + chemoradiation | |

| SCC | 4 |

| Lesion characteristics | Lesions (N=51) |

| Lesion type: | |

| Dysplasia | 19 |

| CIS | 9 |

| CIS with microinvasion | 3 |

| SCC | 20 |

| Lesion location: | |

| Soft palate | 6 |

| Hard palate | 1 |

| Buccal mucosa | 14 |

| Tongue | 15 |

| Gingiva | 5 |

| Floor of mouth | 8 |

| Retromolar trigone | 1 |

| Buccal commisure | 1 |

1 patient had HPPH only

1 patient reported smoking marijuana

Adverse events

All patients reported the expected pain and edema at the treatment site, with pain peaking after approximately 1 week and lasting up to 4 weeks.

There was one DLT encountered at a light dose of 125 J/cm2with a patient developing grade 3 edema at the treatment site, which led to respiratory distress requiring a tracheostomy. This patient had been treated previously with radiotherapy and multiple surgical procedures and consequently suffered from severe trismus, which compromised accurate light delivery to the index lesion located on the hard palate. Although the patient recovered rapidly without sequelae, this event led to the closing of the protocol and addition of severe trismus as an exclusion criterion to a replacement protocol. Four more patients that also had prior radiotherapy had grade 1 edema. Three more patients who had grade 3 edema had no prior radiotherapy. Thus, our data suggests that there was no correlation between edema and prior radiotherapy.

No further airway obstruction due to edema was encountered at any of the light doses. Another patient in the 125 J/cm2cohort experienced a grade 3 edema of 12 hour duration after the 3rd PDT treatment. Two patients in the expanded 140 J/cm2cohort experienced treatment site grade 3 edema that resolved within 24 to 36 hours.

Fifteen mostly elderly patients were hospitalized overnight for observation and released. Most patients took a full liquid/pureed diet due to pain for several days after treatment, but no medical alimentation support was needed. Four patients experienced mild sunburn reactions of short duration due to non-compliance with instructions.

An MTD was not reached at the highest planned light dose level of 140 J/cm2, but further escalation was forgone due to the danger of unacceptable swelling and the risk of airway obstruction.

Response

Details of outcomes, at 3 months post treatment, by light dose and lesion type are shown in Table 2. Forty nine of 51 lesions treated, 26 dysplasia/CiS and 23 SCC, were evaluable for response. All but 1 lesion (evaluated clinically) were evaluated at 3 months by biopsy. Two patients died from unrelated causes before the 3 months follow-up. Given the small numbers and heterogeneity of lesions in each light dose cohort, no light dose dependence is discernible.

Table 2.

Lesion responses by treatment light dose and lesion type

| Light Dose J/cm2 |

No. of Dysplasia/CIS Lesions (Responses) | No. of SCC Lesions (Responses) |

|---|---|---|

| 50 | 2 (1 CR, 1 PR) | 1 (1 PRb) |

| 75 | 2 (2 PR) | 2 (1 CR, 1 SD) |

| 100 | 6 (1 CR, 2 PR) | 2 (2 CR) |

| 125 | 3 (2 CR, 1 PD) | 1 (1 CR) |

| 140 | 13 (6 CR, 2 PR, 3 SD, 2 PD) | 17 (14 CRa, 1 PRb, 2 SDc) |

3 lesions had complete disappearance of carcinoma, but had minor remaining focal dysplasia that was resected

Patients had previous surgery and adjuvant chemoradiation

One patient had previous surgery and adjuvant chemoradiation, one patient had radiation only.

Only the expanded 140 J/cm2 cohort was large enough to give some insight into the response rates. In this cohort, a difference in outcome between dysplasia/CiS and SCC is strongly suggested, although this difference is not quite significant (P=0.0562) with a CR rate of 46% for dysplasia/CiS and 82% for SCC. Of the 6 dysplasia/CiS lesions with CRs, only 2 responses (33%) were durable with 15 months and 9 months, respectively. One of these patients had leukoplakia, the other had erythroplakia. Retreatment of partially responding dysplasia/CiS lesions did not achieve lasting complete responses. Of the 14 SCC lesions with CR, 2 had complete disappearance of SCC, but some remaining minor focal dysplasia, which was locally excised. Two patients died disease-free of unrelated causes at 19 and 5 months. Eight SCC patients with CR are still disease-free (disease-free intervals 6–40 months). Of these, 3 were leukoplakia-free, 3 had leukoplakia, 1 had Lichen planus and 1 had erythroplakia. Excluding the SCC patients that had excision of minor focal dysplasia and the patients that died disease-free, the lasting CR rate for the 140 J/cm2 cohort is 80%. Table 3 lists the CRs in the 140 J/cm2 cohort by lesion location, suggesting that for both dysplasia/CiS and SCC, those on the tongue and floor of mouth responded best.

Table 3.

Complete responses by lesion location in the 140 J/cm2 cohort

| Lesion Location | Dysplasia-CIS /CR | SCC/CR |

|---|---|---|

| Soft palate | 1/1 | 2/1 |

| Buccal mucosa | 4/1 | 4/2 |

| Tongue | 4/3 | 4/4 |

| Gingiva | 2/0 | 3/3 |

| Floor of mouth | 1/1 | 3/3 |

| Oral commisure | 1/0 | - |

| Retromolar trigone | - | 1/1 |

Across all light dose cohorts, among the 5 SCC lesions that did not achieve CR, 3 were in patients who had received prior surgery plus chemoradiotherapy. All lesions that achieved less than CR were successfully treated surgically.

The majority of the lesions were non-confluent. Hence, it was difficult to evaluate the lesion size. A representative example of a lesion that was treated in this study is shown in Figure 1. This was a high grade dysplasia with microinvasion. The entire lesion and margins were illuminated with a 4 cm in diameter spot size. The PDT induced necrosis was observed 7 days post therapy (Figure 1 B). Complete clinical disappearance of the lesion, without scarring, was seen 9 months post PDT (Figure 1 C). The complete clinical response was confirmed with pathological evaluation at 3 months post therapy.

Figure 1.

(A) High grade dysplasia with micro invasion (within the ellipse) prior to therapy. (B) Response to PDT at 7 days post treatment. (C) Complete clinical disappearance of the target lesion at 9 months post PDT.

Molecular assessment of STAT3 cross-linking

Earlier in vitro and in vivo studies have shown that covalent STAT3 cross-linking is proportional to the extent of the photoreaction that is a function of the amount of photosensitizer and light received by the target tissue and the tissue oxygenation status. Hence, the extent of STAT3 cross-linking is a metric for the cumulative PDT reaction (22, 27).

A total of 46 lesions, having received 75, 100, 125 or 140 J/cm2, were evaluable for STAT3 cross-linking, of which 26 were dysplasia/CiS and 20 were SCC. None of the biopsies obtained before illumination showed any STAT3 cross-links. The percent conversion of monomeric to cross-linked STAT3 for all lesions combined as a function of light dose is shown in Figure 2. This non-discriminatory comparison did not indicate any notable light dose dependence.

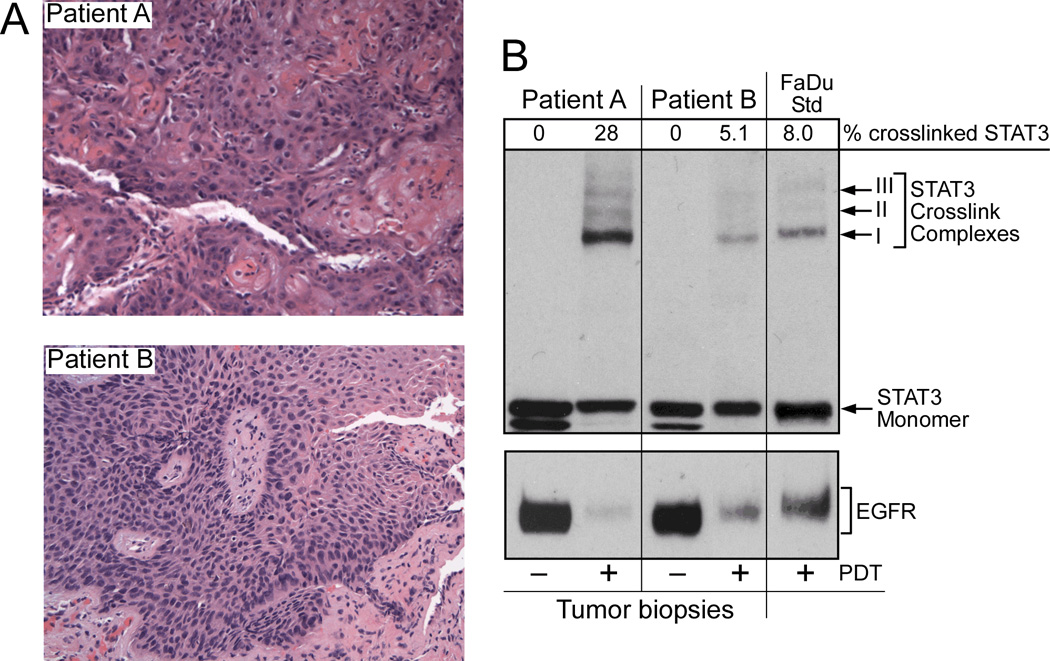

When the data analysis focused on lesion type at diagnosis, a significant pattern emerged – dysplasia/CiS lesions had lower median and mean percent STAT3 conversion than SCC (Figure 3). Data were analyzed for the following groups: all light doses, doses <140 J/cm2 and 140 J/cm2. The difference between dysplasia/CiS and SCC for all doses and 140 J/cm2 is highly significant (P=0.0006 and P=0.0033, respectively). SCC samples for doses <140 J/cm2 were too few for statistical analysis. Two instructive examples for low and high STAT3 cross-linking and corresponding biopsy pathology are shown in Figure 4. It should be noted that not all of the samples for STAT3 cross-link analysis contained SCC histology but included various degrees of dysplasia, likely due to geographic misses in obtaining the biopsies. These samples contributed to the low STAT3 cross-link levels and large variations in the SCC groups in Fig.2. Nevertheless, all histologically proven SCCs registered STAT3 conversion above 10%. Two samples in the SCC category from lesions initially characterized as CiS with microinvasion showed very high STAT3 cross-link levels. All 10 SCCs (1 at 100 J/cm2, 1 at 125 J/cm2, 7 at 140 J/cm2) with STAT3 cross-link levels > 10 (range 12.3% to 36%), except one previously chemo/irradiated lesion, achieved CR. Twenty three dysplasia/CiS and SCC lesions treated with 140 J/cm2 were also analyzed for changes in EGFR expression. Of these, 20 showed an immediate loss of EGFR expression ranging from 15% to 98% (median 81.5%, mean 74.4%). A representative example is shown in Figure 4. Three lesions showed increased EGFR expression of 9%, 28% and 270%, respectively. No correlation with lesion type or response could be found.

Figure 4.

Lesion pathology (A) and STAT3 crosslinking (B) in corresponding halves of biopsies obtained immediately after HPPH-PDT at 140 J/cm2. A) H&E stained biopsy section (100X) of lesions immediately after PDT. Patient A = SCC, Patient B = severe dysplasia. B) Adjacent portion of biopsy samples shown in A was extracted for determination of STAT3 cross-linking and loss or EGFR by immunoblot analyses. The percentage of STAT3 cross-linking was quantified and is listed above the STAT3 immunoblot. Extract of HPPH-PDT treated hypopharyngeal human SCC FaDu served as Western blot reference.

HPPH blood and tissue levels

HPPH serum levels, assessed by fluorescence assay of 40 evaluable patient samples revealed a normal distribution and there was no significant difference between HPPH levels from patients with dysplasia/CiS and SCC (data not shown).

Non-invasive fluorescence spectroscopy assessed HPPH content of the lesions. Twelve dysplasia/CiS and 14 SCC lesions could be analyzed (Figure5). Fluorescence values were significantly (P=0.0431) higher in SCC (median 9.73, mean 10.91) than in dysplasia and CiS (median 6.38, mean 6.80). Although this assessment does not provide the absolute concentration of HPPH in the tissue, it does suggest higher HPPH content in SCC compared to dysplasia and CiS.

Discussion

This report allows the following conclusions: 1) HPPH-PDT in the oral cavity can be safely delivered; 2) early stage oral SCC appears to respond better to HPPH-PDT in comparison to Cis/dysplasia lesions; 3) the extent of PDT induced STAT3 cross-linking was significantly higher in SCC when compared to CiS/dysplasia lesions; 4) the level of STAT3 cross-linking is a significant reporter for evaluating the extent of HPPH-PDT mediated photoreaction.

Although no MTD was reached in these studies, pain and edema could be severe, as was also reported for other PDT agents (29, 30). We effectively relieve those symptoms with proactive administration of tapering dose of steroids, Fentanyl patch and oral narcotics for breakthrough pain for 2 to 3 weeks. Interestingly, PDT of the tongue and floor of mouth, which produced the best responses, consistently was more painful and produced more tissue edema than other oral subsites. Special caution needs to be exercised in the treatment of patients with severe secondary trismus, particularly when accurate light delivery may be compromised. Scar formation leading to trismus, burns and alimentation difficulties have been reported with the use of Foscan® (30), but no such adverse events occurred with HPPH- PDT. General phototoxicity in this study was minimal and limited to erythema, which is in agreement with our previous studies (21).

The complete response rate of 82% for SCC compares well with CR rates reported in the literature for Photofrin® (17, 31, 32) and Foscan®(33). Biel reported clinical CR rates of over 90% (14) and Schweitzer et al. reported clinical CR rates of 80% in retrospective studies with Photofrin-PDT in the treatment of CiS and early stage oral cancers (34). A recent retrospective study with Foscan-PDT reported a CR rate of 71% in 170 patients with oral cavity primary and recurrent tumors. They reported higher overall response in previously untreated neoplasms (30). In our study we also observed a higher CR rate in previously untreated cancers. Interestingly, tumors located on the tongue or floor of mouth seemed to respond best, as was also reported by Karakullukcu et al. (30). The presence of leukoplakia or erythroplakia did not seem to affect outcome.

The CR rate of oral dysplasias and CiS was less to that of SCC, as previously observed by Rigual et al. (29) with Photofrin-PDT. This result appears counterintuitive because of the limited tissue depth of these lesions. An explanation for this outcome might be found in lower HPPH levels in premalignant lesions suggested by non-invasive fluorescence measurements. The reasons for the higher HPPH accumulation in tumor lesions are likely twofold: better drug delivery due to a well-established vasculature and enhanced retention of HPPH by tumor cells. The importance of vascularity and photosensitizer uptake in small tumor nodules has been emphasized by Menon et al. (35). Also, earlier fluorescence spectroscopy studies with Photofrin® (36) and HPPH (37) aimed at tumor diagnosis, have demonstrated increasing lesion fluorescence with progression from premalignant to malignant disease in a hamster buccal cheek pouch tumor model. Fluorescence values showed a high correlation with drug concentrations as determined by chemical drug extraction (38). Enhanced retention of HPPH by tumor cells has been clearly demonstrated for the first time by Tracy et al.(28) in primary human lung and H&N tumor cells, maintained in the presence of corresponding stromal cells.

The better response of SCC to HPPH-PDT is proportionally reflected in the higher levels of STAT3 cross-links compared to dysplasia and CiS. This held true whether data from all light doses or from only the 140 J/cm2 cohort were examined. We had hypothesized that the light dose escalation would be manifested in the level of STAT3 cross-links detectable in biopsies collected following PDT. This was not the case. One could assume that this lack of dose response might be due to the cross-linking reaction having reached a saturation point. This, however, is unlikely since there was a large spread of STAT3 cross-link levels in all three cohorts (100–140 J/cm2) ranging from 0.5% to 36% STAT3 monomer conversion to cross-links. Interestingly, a dose analysis undertaken by Davidson et al. (39) in patients undergoing PDT with the photosensitizer TOOKAD for prostate cancer found that the threshold dose for PDT-induced damage was highly heterogeneous among patients. They speculated that this heterogeneity was due to varying amounts of photosensitizer or oxygen in the tissue.

Activated STAT3 has been implicated in the loss of growth control in HNSCC through anti-apoptotic mechanisms (40). However, there is no evidence that cross-linking of a fraction of STAT3 per se affects cell survival (22). Earlier studies have demonstrated that PDT causes the loss of EGFR (41, 42). The current analyses confirmed the PDT-associated reduction of EGFR in oral lesion. Studies on cultured cells have indicated that restoration of full EGF responsiveness can require several days. This may contribute to a transient reduction in growth stimulation and delayed recovery.

STAT3 cross-linking was found only in biopsies collected after PDT. The level of STAT3 crosslinking was significantly higher (P=0.0033) in SCC when compared to CiS/dysplasia lesions for all levels of light doses, and the fluorescence values of HPPH were significantly higher (P=0.0431) in SCC than in dysplasia and CiS. Therefore, our data suggests that the level of STAT3 cross-linking is a significant reporter for evaluating HPPH-PDT mediated photoreaction. Additional studies are required to assess the use of STAT3 crosslinking assay as a prognostic biomarker for evaluating tumor response.

Surgery and radiotherapy are currently considered effective treatment modalities for early stage oral cancer (3, 43). However, surgery removes vital tissue and radiotherapy has lasting sequelae that have shown to impair QoL, long after the patients were cured. Therefore, targeted therapies which are repeatable and spare vital tissue are necessary. In this study, HPPH-PDT was found to be a promising therapy for the treatment of early stage oral cancers in that the majority of patients had a pathologic CR or a PR in which invasive disease was downgraded to dysplasia and treated effectively with minimal surgery. This is of clinical importance since the effective surgical treatment of dysplasia may be accomplished with a more limited resection of vital oral tissue than the surgical treatment of early stage oral SCC. HPPH-PDT treatment also resulted in good tissue healing. This outcome is in agreement with observations in our recent intraoperative HPPH-PDT study, where we reported excellent secondary healing of skin burns in two patients due to phototoxicity (16). The good healing could be explained by the fact that HPPH is not retained in fibroblasts (28). Thus, the HPPH-PDT induced damage cells are replaced by native tissue that regains its normal functions, significantly limiting function loss and minimized scar formation. These promising results warrant the design of a Phase II study.

Translational Relevance.

This study is the first to explore HPPH PDT for the treatment of HNSCC and the first to use STAT 3 cross-linking as a molecular marker for the evaluation of PDT mediated photoreaction in the treated lesion.

Acknowledgements

We thank Drs. Thomas Foster and Sandra Gollnick for their critical review of this manuscript.

This study was supported by NCI grants PO1CA55791 (to BWH) and Roswell Park Cancer Institute Support Grant P30CA16056.

References

- 1.SEER. Cancer Statistics Review. 2013 [Updated June 14, 2013]. Available from: http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2010/.

- 2.Kekatpure V, Kuriakose A. Oral Cancer in India: Learning from Different Populations. Prevention. 2012;14:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Day TA, Davis BK, Gillespie MB, Joe JK, Kibbey M, Martin-Harris B, et al. Oral cancer treatment. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2003;4:27–41. doi: 10.1007/s11864-003-0029-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Umeda M, Komatsubara H, Ojima Y, Minamikawa T, Shibuya Y, Yokoo S, et al. A comparison of brachytherapy and surgery for the treatment of stage I-II squamous cell carcinoma of the tongue. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2005;34:739–744. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2005.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thomas L, Moore EJ, Olsen KD, Kasperbauer JL. Long-term quality of life in young adults treated for oral cavity squamous cell cancer. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2012;121:395–401. doi: 10.1177/000348941212100606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Castro G, Jr, Awada A. Second primary cancers in head and neck cancer patients: a challenging entity. Curr Opin Oncol. 2012;24:203–204. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0b013e3283519183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Digonnet A, Hamoir M, Andry G, Haigentz M, Jr, Takes RP, Silver CE, et al. Post-therapeutic surveillance strategies in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2013;270:1569–1580. doi: 10.1007/s00405-012-2172-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hsu SH, Wong YK, Wang CP, Wang CC, Jiang RS, Chen FJ, et al. Survival analysis of patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma with simultaneous second primary tumors. Head Neck. 2013 doi: 10.1002/hed.23242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jerjes W, Upile T, Petrie A, Riskalla A, Hamdoon Z, Vourvachis M, et al. Clinicopathological parameters, recurrence, locoregional and distant metastasis in 115 T1–T2 oral squamous cell carcinoma patients. Head Neck Oncol. 2010;2:9. doi: 10.1186/1758-3284-2-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shim SJ, Cha J, Koom WS, Kim GE, Lee CG, Choi EC, et al. Clinical outcomes for T1-2N0-1 oral tongue cancer patients underwent surgery with and without postoperative radiotherapy. Radiat Oncol. 2010;5:43. doi: 10.1186/1748-717X-5-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li Y, Bai S, Carroll W, Dayan D, Dort JC, Heller K, et al. Validation of the risk model: High-risk classification and tumor pattern of invasion predict outcome for patients with low-stage oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma. Head Neck Pathol. 2012 doi: 10.1007/s12105-012-0412-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Henderson BW, Dougherty TJ. How does photodynamic therapy work? Photochem Photobiol. 1992;55:145–157. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1992.tb04222.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Agostinis P, Berg K, Cengel KA, Foster TH, Girotti AW, Gollnick SO, et al. Photodynamic therapy of cancer: An update. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011 doi: 10.3322/caac.20114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Biel M. Advances in photodynamic therapy for the treatment of head and neck cancers. Lasers Surg Med. 2006;38:349–355. doi: 10.1002/lsm.20368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lou PJ, Jager HR, Jones L, Theodossy T, Bown SG, Hopper C. Interstitial photodynamic therapy as salvage treatment for recurrent head and neck cancer. Br J Cancer. 2004;91:441–446. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rigual N, Shafirstein G, Frustino J, Seshadri M, Cooper M, Wilding G, et al. Adjuvant intraoperative photodynamic therapy in head and neck cancer. JAMA Otolaryngology-Head & Neck Surgery. 2013;139(7):706–711. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2013.3387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Biel MA. Photodynamic therapy treatment of early oral and laryngeal cancers. Photochem Photobiol. 2007;83:1063–1068. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.2007.00153.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bellnier DA, Greco WR, Loewen GM, Nava H, Oseroff AR, Pandey RK, et al. Population pharmacokinetics of the photodynamic therapy agent 2-[-1-hexyloxyethyl]-2-devinyl pyropheophorbide-a in cancer patients. Can Res. 2003;63:1806–1813. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Henderson BW, Bellnier DA, Greco WR, Sharma A, Pandey RK, Vaughan LA, et al. An in vivo quantitative structure-activity relationship for a congeneric series of pyropheophorbide derivatives as photosensitizers for photodynamic therapy. Cancer Res. 1997;57:4000–4007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Loewen GM, Pandey R, Bellnier D, Henderson B, Dougherty T. Endobronchial photodynamic therapy for lung cancer. Lasers Surg Med. 2006;38:364–370. doi: 10.1002/lsm.20354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bellnier DA, Greco WR, Nava H, Loewen GM, Oseroff AR, Dougherty TJ. Mild skin photosensitivity in cancer patients following injection of Photochlor (2-1-[1-hexyloxyethyl]-2-devinylpyropheophorbide-a) for photodynamic therapy. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2005;57:40–45. doi: 10.1007/s00280-005-0015-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu W, Oseroff AR, Baumann H. Photodynamic therapy causes cross-linking of signal transducer and activator of transcription proteins and attenuation of interleukin-6 cytokine responsiveness in epithelial cells. Cancer Res. 2004;64:6579–6587. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nava HR, Allamaneni SS, Dougherty TJ, Cooper MT, Tan W, Wilding G, Henderson BW. Photodynamic Therapy (PDT) Using HPPH for the Treatment of Precancerous Lesions Associated With Barrett's Esophagus. Lasers in Surgery and Medicine. 2011;43:705–712. doi: 10.1002/lsm.21112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lin Y, Shih WJ. Statistical properties of the traditional algorithm-based designs for phase I cancer clinical trials. Biostatistics. 2001;2:203–215. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/2.2.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rohrbach DJ, Rigual N, Tracy E, Kowalczewski A, Keymel KL, Cooper MT, et al. Interlesion differences in the local photodynamic therapy response of oral cavity lesions assessed by diffuse optical spectroscopies. Biomed Opt Express. 2012;3:2142–2153. doi: 10.1364/BOE.3.002142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sunar U, Rohrbach D, Rigual N, Tracy E, Keymel KR, Cooper M, et al. Monitoring photobleaching and hemodynamic responses to HPPH-mediated photodynamic therapy of head and neck cancer:a case report. Optics Express. 2010;18:14969–14978. doi: 10.1364/OE.18.014969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Henderson BW, Daroqui C, Tracy E, Vaughan L, Loewen GM, Cooper M. Cross-linking of signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) - A molecular marker for the photodynamic reaction in cells and tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:3156–3163. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tracy EC, Bowman MJ, Pandey RK, Henderson BW, Baumann H. Cell-type selective phototoxicity achieved with chlorophyll-a derived photosensitizers in a co-culture system of primary human tumor and normal lung cells. Photochem Photobiol. 2011;87:1405–1418. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.2011.00992.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rigual NR, Thankappan K, Cooper M, Sullivan MA, Dougherty T, Popat SR, et al. Photodynamic therapy for head and neck dysplasia and cancer. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2009;135:784–788. doi: 10.1001/archoto.2009.98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Karakullukcu B, van OK, Copper MP, Klop WM, Van VR, Wildeman M, et al. Photodynamic therapy of early stage oral cavity and oropharynx neoplasms: an outcome analysis of 170 patients. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2011;268:281–288. doi: 10.1007/s00405-010-1361-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Santos O, Perez LM, Briggle TV, Boothman DA, Greer SB. Radiation, pool size and incorporation studies in mice with 5- chloro-2'-deoxycytidine. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1990;19:357–365. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(90)90544-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schweitzer VG, Somers ML. PHOTOFRIN-mediated photodynamic therapy for treatment of early stage (Tis-T2N0M0) SqCCa of oral cavity and oropharynx. Lasers Surg Med. 2010;42:1–8. doi: 10.1002/lsm.20881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Copper MP, Tan IB, Oppelaar H, Ruevekamp MC, Stewart FA. Meta-tetra(hydroxyphenyl) chlorin photodynamic therapy in early-stage squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2003;129:709–711. doi: 10.1001/archotol.129.7.709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schweitzer VG. PHOTOFRIN-mediated photodynamic therapy for treatment of early stage oral cavity and laryngeal malignancies. Lasers Surg Med. 2001;29:305–313. doi: 10.1002/lsm.1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Menon C, Kutney SN, Lehr SC, Hendren SK, Busch TM, Hahn SM, et al. Vascularity and uptake of photosensitizer in small human tumor nodules: implications for intraperitoneal photodynamic therapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7:3904–3911. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mang T, Kost J, Sullivan M, Wilson BC. Autofluorescence and Photofrin-induced fluorescence imaging and spectroscopy in an animal model of oral cancer. Photodiagnosis Photodyn Ther. 2006;3:168–176. doi: 10.1016/j.pdpdt.2006.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Furukawa K, Crean EA, Manganiello LOJ, Kato H, Dougherty T. Fluorescence detection of premalignant, malignant, and micrometastatic disease using hexylpyropheophorbide. 5th International Photodynamic Association Biennial Meeting. 1994 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Crean DH. PhD Thesis. State University of New York at Buffalo; 1993. An Evaluation of Photofrin-Induced Fluorescence in Detecting Developing Malignancies. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Davidson SR, Weersink RA, Haider MA, Gertner MR, Bogaards A, Giewercer D, et al. Treatment planning and dose analysis for interstitial photodynamic therapy of prostate cancer. Phys Med Biol. 2009;54:2293–2313. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/54/8/003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Grandis JR, Drenning SD, Zeng Q, watkins SC, Melhem MF, Endo S, et al. Constitutive activation of Stat3 signaling abrogates apoptosis in squamous cell carcinogenesis in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:4227–4232. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.8.4227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ahmad N, Kalka K, Mukhtar H. In vitro and in vivo inhibition of epidermal growth factor receptor-tyrosine kinase pathway by photodynamic therapy. Oncogene. 2001;20:2314–2317. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liu W, Oseroff AR, Baumann H. Photodynamic therapy causes cross-linking of signal transducer and activator of transcription proteins and attenuation of interleukin-6 cytokine responsiveness in epithelial cells. Cancer Res. 2004;64:6579–6587. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nyst HJ, Tan IB, Stewart FA, Balm AJ. Is photodynamic therapy a good alternative to surgery and radiotherapy in the treatment of head and neck cancer? Photodiagnosis Photodyn Ther. 2009;6:3–11. doi: 10.1016/j.pdpdt.2009.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]