Abstract

Plasmodium falciparum reticulocyte binding-like homologous protein 5 (PfRH5) is an essential merozoite ligand that binds with its erythrocyte receptor, basigin. PfRH5 is an attractive malaria vaccine candidate, as it is expressed by a wide number of P. falciparum strains, cannot be genetically disrupted, and exhibits limited sequence polymorphisms. Viral vector-induced PfRH5 antibodies potently inhibited erythrocyte invasion. However, it has been a challenge to generate full-length recombinant PfRH5 in a bacterial-cell-based expression system. In this study, we have produced full-length recombinant PfRH5 in Escherichia coli that exhibits specific erythrocyte binding similar to that of the native PfRH5 parasite protein and also, importantly, elicits potent invasion-inhibitory antibodies against a number of P. falciparum strains. Antibasigin antibodies blocked the erythrocyte binding of both native and recombinant PfRH5, further confirming that they bind with basigin. We have thus successfully produced full-length PfRH5 as a functionally active erythrocyte binding recombinant protein with a conformational integrity that mimics that of the native parasite protein and elicits potent strain-transcending parasite-neutralizing antibodies. P. falciparum has the capability to develop immune escape mechanisms, and thus, blood-stage malaria vaccines that target multiple antigens or pathways may prove to be highly efficacious. In this regard, antibody combinations targeting PfRH5 and other key merozoite antigens produced potent additive inhibition against multiple worldwide P. falciparum strains. PfRH5 was immunogenic when immunized with other antigens, eliciting potent invasion-inhibitory antibody responses with no immune interference. Our results strongly support the development of PfRH5 as a component of a combination blood-stage malaria vaccine.

INTRODUCTION

Malaria is a global infectious disease that accounts for around one million deaths across the world, primarily in children below the age of 5 years (1). The causative agent of the most severe form of malaria, which is responsible for maximum mortality, is the parasite Plasmodium falciparum. Invasion of human erythrocytes (RBCs) by P. falciparum is a critical process during the parasite's life cycle that leads to the development of blood-stage parasites, which are primarily responsible for malaria pathogenesis. P. falciparum has evolved a complex, multistep process of erythrocyte invasion that involves numerous ligand-receptor interactions (2–4). This molecular redundancy allows the parasite to use many alternate pathways for invasion, thus ensuring that the pathogen gains entry into its host erythrocyte (2–4).

The quest for developing a vaccine that targets blood-stage parasites has involved extensive studies on identifying and characterizing key parasite molecules that mediate erythrocyte invasion. Early efforts have focused on two leading candidates, MSP-142 and AMA-1, which play an essential role in erythrocyte invasion (2–4) but have unfortunately not generated optimal protection in field efficacy trials (5–7). Recently, the family of P. falciparum reticulocyte binding-like homologous proteins (PfRH) has attracted the most attention as key determinants of merozoite invasion (2–4, 8, 9). The PfRH family comprises of five members—PfRH1, PfRH2a, PfRH2b, PfRH4, and PfRH5—that bind with either sialic acid-dependent or sialic acid-independent erythrocyte receptors (10–22). However, most of these proteins are not essential for erythrocyte invasion and can be genetically disrupted (4, 8, 9), with the exception of PfRH5 (22).

PfRH5 (GenBank accession number, XP_001351544; PlasmoDB identification code, PF3D7_0424100) was first identified by genetic mapping as a key determinant of species-specific erythrocyte invasion (21). Genetic analysis of the progeny of a P. falciparum cross between two parental clones, 7G8 × GB4, had mapped the PfRH5 gene on chromosome 4 as the locus responsible for mediating invasion of Aotus nancymaae erythrocytes as well as infectivity of Aotus monkeys (21). It was also demonstrated that PfRH5 is an erythrocyte binding ligand in which single point mutations critically affected the specificity of its binding with Aotus erythrocytes (21). Recently, PfRH5 has also been shown to play a role in the invasion of both owl monkey and rat erythrocytes by P. falciparum (23). Further, PfRH5 was found to be unique in being the only erythrocyte binding ligand among the EBA/PfRH families that is essential for the parasite, as it cannot be genetically knocked out (22), suggesting a crucial role in erythrocyte invasion. PfRH5 is also exceptional compared to other PfRH homologues, as it is smaller (63 kDa) and lacks a transmembrane domain (21, 22). PfRH5 has been shown to be localized on the merozoite surface in association with another parasite molecule, PfRipr (P. falciparum PfRH5-interacting protein) (24). While PfRH proteins are differentially expressed among different P. falciparum clones that exhibit phenotypic variation in their invasion properties (11, 13, 16–19), the expression of PfRH5 was found to be consistent among these parasite clones (21, 22).

Recently, PfRH5 was reported to bind with the CD147 IgG superfamily member basigin (BSG) on the erythrocyte surface (25). For this study, a mutated version of PfRH5 was produced in mammalian HEK293 cells as a biotinylated fusion protein with CD4 domains 3 and 4 [CD4(d3 + 4)] of rat origin, which was found to bind with a pentamer of basigin (25). The mutations were necessary to produce a nonglycosylated protein in the mammalian cells similar to that of the native parasite protein, which, like P. falciparum native proteins, remains essentially unglycosylated. The significance of the PfRH5-BSG interaction was highlighted by the demonstration that anti-BSG antibodies blocked erythrocyte invasion by a large number of P. falciparum clones that were known to exhibit different invasion phenotypes (25). However, no data were reported in this elegant study on the interaction of native PfRH5 with basigin.

A heterologous prime-boost strategy based on the adenoviral-modified vaccinia Ankara (MVA) viral vector platform was used to generate anti-PfRH5 antibodies that efficiently inhibited erythrocyte invasion by multiple heterologous P. falciparum clones (26). It has also been recently reported that antibodies against a fusion protein comprising of a mutated PfRH5 with domains 3 and 4 of the rat CD4 protein exhibited potent inhibition of erythrocyte invasion (27). This study further substantiated the importance of the PfRH5-BSG interaction during erythrocyte invasion and strongly supported PfRH5 as a blood-stage vaccine candidate. However, polymorphisms in PfRH5 as well as other P. falciparum adhesins have been shown to induce changes in their receptor specificities (2, 3, 21, 23) and could also possibly alter native structure. Thus, the production of a functionally active recombinant wild-type full-length PfRH5 protein, which would elicit similar potent invasion-inhibitory antibodies, in a cell-based expression system that could be scalable for mass production still remained a challenge not only from a vaccine perspective but also to facilitate the basic structure-function analysis of PfRH5.

Also considering that the target population of a prophylactic malaria vaccine is young infants and children, it is important to test different expression platforms so as to identify the safest and most efficacious antigen or delivery mechanism that would be most feasible to administer as a vaccine for mass immunization. In this regard, the subunit vaccine approach based on formulations of recombinant proteins and adjuvant poses a safe and effective platform for administering a vaccine for large masses. However, the test here lies in being able to produce the recombinant protein with a structural integrity that yields potent neutralizing antibodies against the respective pathogens.

Expression in Escherichia coli provides a cost-effective method for production of recombinant proteins for use as biologics and vaccines. Previous studies on the production of recombinant proteins against PfRH5 in E. coli have focused on expressing smaller fragments of 143 to 168 amino acids (22, 28). Both these recombinant fragments failed to elicit invasion-inhibitory antibodies (22, 28). This is consistent with the recent study using the adenovirus-MVA prime-boost approach that demonstrated potent invasion-inhibitory antibodies only against full-length PfRH5 and not against the 168-amino-acid fragment of PfRH5 (26).

In light of these reports, in our study we have demonstrated that the full-length wild-type PfRH5 recombinant protein produced in E. coli was efficacious in eliciting potent invasion inhibition consistent with that observed with the viral vector delivery platform (26) or with the rat CD4(d3 + 4) fusion construct (27). In the current study, we have successfully produced full-length PfRH5 as a recombinant protein in E. coli that exhibits specific erythrocyte binding activity similar to that of the native PfRH5 parasite protein. We also demonstrated that antibasigin antibodies blocked the erythrocyte binding of both native and recombinant PfRH5 proteins, further confirming that basigin acts as their erythrocyte receptor. Our recombinant PfRH5 elicited potent strain-transcending invasion-inhibitory antibodies that blocked a number of heterologous parasite clones. Importantly, the PfRH5 antibodies produced additive invasion inhibition in combination with antibodies against other key merozoite antigens. Thus, our study strongly supports the development of PfRH5-based antigen combinations as malaria vaccine candidates.

(This work has been previously presented at the 24th National Congress of Parasitology in Jabalpur, Madhya Pradesh, India [27 to 29 April 2013], and the 2013 Malaria Gordon Research Conference in Tuscany, Italy [4 to 9 August 2013].)

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ethics statement.

The animal studies described below were approved by the International Centre for Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology (ICGEB) Institutional Animal Ethics Committee (IAEC) (reference no. MAL-51) according to the guidelines of the Department of Biotechnology, Government of India.

Cloning, expression, and purification of the full-length recombinant PfRH5.

The 1,500-bp PfRH5 gene that encodes the 500-amino-acid full-length parasite protein excluding the signal sequence (rPfRH563, Asp27-Gln526) was PCR amplified from the genomic DNA of the P. falciparum clone 3D7 using the following primers: RH5-Fwd:], 5′-ATATATAATTCATATGAATGCAATAAAAAAAACGAAGAAT-3′, and RH5-Rev, 5′-AGCACTCGAGTTGTGTAAGTGGTTTATTTTTTT-3′. The PCR product encoding rPfRH563 was digested with NdeI and XhoI (New England BioLabs, Beverly, MA) and inserted downstream of the T7 promoter in the E. coli expression vector pET-24b (Novagen, San Diego, CA) with a C-terminal 6-histidine (6-His) tag to obtain the plasmid pPfRH5-pET24b. Sequencing of the ligated plasmid confirmed the correct sequence of the PfRh5 gene and that the insertions were in the correct reading frame.

E. coli BL21(DE3) was transformed with pPfRH5-pET24b and was used to produce the recombinant protein rPfRH563. Transformed E. coli BL21(DE3) was cultured in superbroth at 37°C and later induced with 1 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) when the optical density at 600 nm (OD600) was around 0.8 to 0.9. Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 3,000 × g after 4 h of induction at 37°C. Cell pellets were lysed by sonication, and rPfRH563 was found to be expressed as inclusion bodies. The inclusion bodies were washed, collected by centrifugation at 15,000 × g, and solubilized in a buffer containing 20 mM Tris (pH 8.0), 6 M guanidium HCl, 300 mM NaCl, 10 mM imidazole, and 5 mM beta-mercaptoethanol. rPfRH563 was purified from solubilized inclusion bodies by metal affinity chromatography using Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid (NTA) resin. Metal affinity-purified rPfRH563 was refolded under redox conditions by rapid dilution (30-fold) in a 2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulfonic acid (MES)-based buffer (pH 6.5) comprising of 1 mM GSH (reduced glutathione), 0.1 mM GSSG (oxidized glutathione), and 440 mM sucrose. The refolded protein was dialyzed against 25 mM MES (pH 6.5)–200 mM sucrose and further purified to homogeneity by cation-exchange chromatography using an SP-Sepharose column (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ). The dialyzed protein was loaded on the SP-Sepharose column and eluted with an increasing concentration of NaCl (0 to 1 M) in the MES-based buffer. The purified recombinant rPfRH563 protein was characterized by SDS-PAGE, Western blotting, Edman degradation, liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) analysis (Orbitrap VELOS PRO; Thermo Fisher Scientific), reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (RP-HPLC; C8 column; Waters), and size exclusion chromatography (SEC; Superdex 75 10/300 GL; GE Healthcare).

Animal immunization and antibody generation.

Animal immunizations and total IgG purification were done as reported previously (29). Briefly, five rats and three rabbits were immunized intramuscularly with 50 μg and 100 μg of rPfRH563, respectively. The rPfRH563 protein was emulsified with complete Freund's adjuvant (CFA; Sigma, St. Louis, MO) for immunization on day 0, followed by two boosts emulsified with incomplete Freund's adjuvant (IFA) on days 28 and 56. The sera were collected on day 70. Antibody levels were measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA).

For coimmunogenicity, a group of six BALB/c mice were immunized with antigen mixtures PfF2-PfRH5-PfAARP and PfRH2-PfRH5-PfAARP as well as individual antigens emulsified with complete Freund's adjuvant on day 0, followed by two boosts emulsified with incomplete Freund's adjuvant on days 28 and 56. Seventeen micrograms of each antigen was immunized in each mouse, whether used alone or as a coimmunization triple-antigen mixture (total, 51 μg). Terminal bleeds were collected on day 70. Sera were tested for antibody titers and specific recognition of each recombinant protein by ELISA. For the growth inhibition assay (GIA), the sera from the six mice in each group were pooled for IgG purification.

Total IgG was purified from the mouse, rat, or rabbit sera using a protein G affinity column (GE Healthcare, Uppsala, Sweden), dialyzed with RPMI medium, and further tested in invasion inhibition assays as described below. As an adjuvant negative control, we also had raised antibodies in mice, rats, and rabbits against a nonrelated peptide (KESRAKKFQRKHITNTRDVD from human pancreatic RNase) that was also formulated with the same adjuvant (CFA or IFA) and injected in animals with the same schedule used for raising the PfRH5 antibodies as described above.

Erythrocytes and enzymatic treatment.

Packed RBCs were procured from the Rotary Blood Bank (Tughlaqabad), New Delhi, India. Erythrocytes were washed in RPMI medium and stored at 50% hematocrit. Enzymatic treatments of erythrocytes were done as stated previously (16, 20, 29).

Erythrocyte binding assays:.

Soluble parasite proteins were obtained from 3D7 culture supernatants as described previously (16, 20, 29). Briefly, 500 μl of culture supernatant was incubated with a 100-μl packed volume of human erythrocytes at 37°C, following which the suspension was centrifuged through dibutyl phthalate (Sigma). The supernatant and oil were removed by aspiration, and bound parasite proteins were eluted using 1.5 M NaCl. For rPfRH563 binding, 0.04 μM rPfRH5 was incubated with a 100-μl packed volume of human erythrocytes at 37°C in similar erythrocyte binding assays as described above. The eluate fractions were analyzed for the presence of native PfRH5 and rPfRH563 by immunoblotting using anti-rPfRH563 antibodies.

Invasion inhibition assays.

Invasion inhibition assays were performed as described previously (16, 29) using total IgG purified from the sera of different animals immunized with rPfRH563. Briefly, schizont-stage parasites at an initial parasitemia of 0.3% at 2% hematocrit were incubated with purified total IgG for one cycle of parasite growth (40 h postinvasion). The parasite-infected erythrocytes were stained with ethidium bromide dye and measured by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) as described previously (16, 29). The percent invasion inhibition for each immune IgG was calculated with respect to the control preimmune IgG from the same animal. As another negative control, we used immune IgG raised against a nonrelated peptide from human pancreatic RNase that was also immunized with the same adjuvant (CFA or IFA) as used for raising the PfRH5 antibodies. The results represent the averages of three independent experiments performed in duplicate, and the error bars represent the standard error of the mean. Statistical significance was calculated using the Student t test (Graph Pad Prism software, version 6.03). P values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Expression of the full-length recombinant PfRH5 protein and generation of specific PfRH5 antibodies.

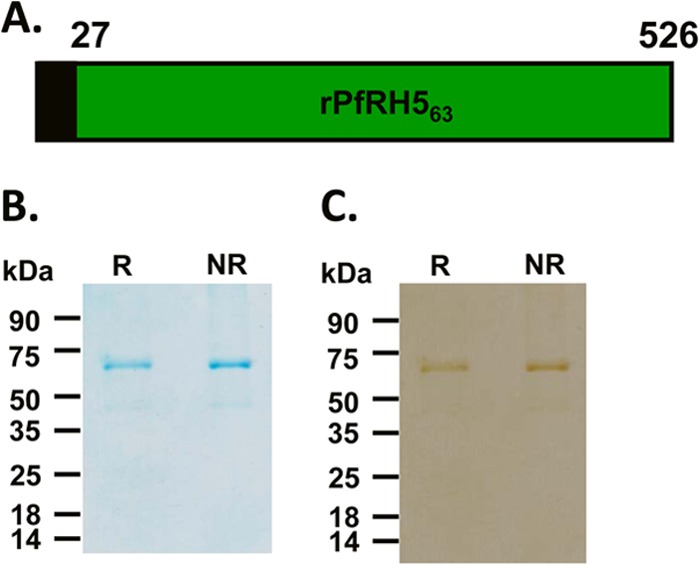

A 500-amino-acid sequence (Asn27-Gln526) of PfRH5 from the P. falciparum clone 3D7, comprising the full-length protein excluding the signal peptide, was chosen for recombinant protein expression in E. coli (Fig. 1A). The recombinant 63-kDa PfRH5 (rPfRH563) was expressed with a C-terminal 6-His tag. In E. coli, the rPfRH563 protein got expressed in inclusion bodies, which were then refolded after purification under denaturing conditions by metal affinity chromatography. rPfRH563 was further purified to homogeneity using ion-exchange chromatography (Fig. 1B).

FIG 1.

Production of the recombinant rPfRH563 protein. (A) Schematic representation of the PfRH5 parasite protein. The region in black denotes the signal peptide (residues 1 to 26), and the region in green (residues 27 to 526) was expressed in E. coli. (B) Purified rPfRH563 protein analyzed by 12% SDS-PAGE and stained with Coomassie blue. Two micrograms of rPfRH563 was loaded in each well. (C) Recombinant rPfRH563 protein detected in immunoblots using the anti-His tag antibody. R and NR, reducing and nonreducing conditions, respectively.

Recombinant rPfRH563 comprises of 6 cysteines that could lead to three potential disulfide linkages. Initial SDS-PAGE analysis of the purified protein on a 12% gel under both reducing and nonreducing conditions did not reflect a mobility shift (Fig. 1B). However, when the rPfRH563 protein was run on the same gel for a longer period such that the 35-kDa prestained marker protein reached the end of the gel, a mobility shift could be detected (see Fig. S1A in the supplemental material). The SDS-PAGE analysis was repeated with a highly cysteine-rich recombinant protein (rEBA-175 RII) that has 24 cysteines leading to 12 potential disulfide bonds (see Fig. S1B and C). rEBA-175 RII exhibited a significant mobility shift, in contrast to rPfRH563, which showed no shift when run normally on the 12% SDS-PAGE gel (see Fig. S1B). On running the gel for a longer time, the mobility shift increased for rEBA-175 RII and became detectable for rPfRH563 (see Fig. S1C). Edman degradation analysis of the full-length rPfRH563 protein yielded an N-terminal sequence (MNAIKK) that matched with the protein sequence of the PfRH5 native parasite protein after the signal sequence from amino acid Asn27 onwards (see Fig. S1C). Recombinant rPfRH563 was identified in immunoblots using a specific anti-His tag antibody (Fig. 1C), confirming expression of the full-length 500-amino-acid protein with the C-terminal His tag. While the SDS-PAGE analysis of the rPfRH563 protein showed a highly pure protein preparation with the predominant band at 63 kDa, traces of a smaller (45-kDa) protein were also faintly visible. These two protein bands were excised from the gel and subjected to trypsin digestion followed by LC-MS (liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry) analysis (Orbitrap VELOS PRO; Thermo Fisher Scientific). The LC-MS analysis revealed a large number of unique high-scoring peptides for both proteins (32 peptides for the 63-kDa protein; 31 peptides for the 45-kDa protein) that confirmed the identity of both proteins to be PfRH5 (see Tables S1 and S2 in the supplemental material). The detection of the smaller protein is consistent with previous reports on the production of recombinant PfRH5 in HEK293 cells (27) and that observed in the parasite lysate (22). We further analyzed the recombinant protein by size exclusion chromatography (SEC) and confirmed that our recombinant protein eluted at the expected molecular size with respect to the bovine serum albumin (BSA) standard protein, which also has a similar molecular mass (66 kDa) (see Fig. S1D in the supplemental material). The SEC profile also showed that our recombinant protein was primarily in a monomeric state. The recombinant rPfRH563 protein was further analyzed using reverse-phase HPLC (RP-HPLC), which showed a single symmetrical peak reflecting a highly pure protein preparation (see Fig. S1E).

Rats and rabbits were immunized with rPfRH563 to raise PfRH5-specific antibodies. High-titer antibodies against rPfRH563 were detected in both rats and rabbits, with endpoints observed at dilutions of 1:320,000 (data not shown). The specificity of the PfRH5 antibodies was analyzed by immunoblotting studies to detect the PfRH5 native protein in parasite lysates and localization studies in merozoites by immunofluorescence superresolution confocal microscopy (N-SIM; Nikon, Japan). Consistent with previous reports, native parasite PfRH5 was detected in immunoblots at the expected size for the full-length protein (63 kDa) only in the schizont stages and not in early rings or trophozoite stages (see Fig. S2A and B in the supplemental material). PfRH5 has been reported to be localized in the rhoptry bulb by immunoelectron microscopy (22). With our antibodies, PfRH5 was also found to colocalize with the known rhoptry bulb protein, PTRAMP (30) (see Fig. S3A in the supplemental material). On the other hand, there was no colocalization observed with the rhoptry neck protein, PfRH2 (see Fig. S3B), or the micronemal protein, PfEBA-175 (see Fig. S3C). Our data were consistent with previous reports (22) and confirmed the specificity of our PfRH5 antibodies.

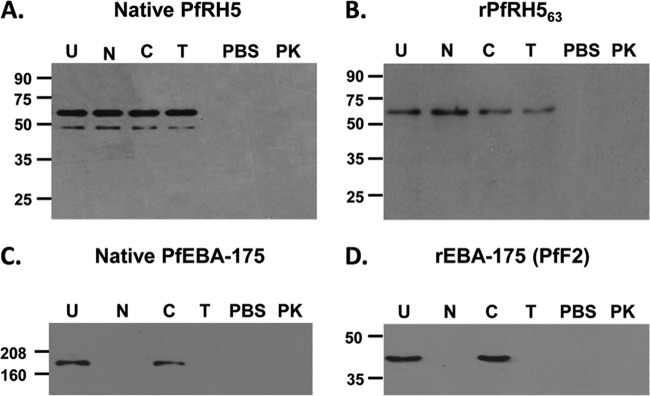

Recombinant PfRH5 exhibits specific erythrocyte binding activity.

Standard erythrocyte binding assays were performed with parasite culture supernatant (3D7) incubated with human erythrocytes as described previously (16, 20, 29). Native PfRH5 parasite protein (63 kDa) has been reported to be processed into smaller fragments of 45 kDa and 28 kDa (21, 22). The full-length native PfRH5 and its processed fragments bind erythrocytes with the same specificity (21, 22, 28). In our assay, we prepared 3D7 culture supernatants and observed that both the native 63-kDa full-length PfRH5 protein and the 45-kDa processed protein bound erythrocytes in a sialic acid-independent, trypsin- and chymotrypsin-resistant manner (Fig. 2A), which is consistent with previous reports (21, 22). While in this culture supernatant we did not observe the 28-kDa fragment, in another culture supernatant preparation in which the parasites were incubated for a longer period, we detected the 28-kDa fragment and observed it to bind erythrocytes with the same specificity (see Fig. S2C in the supplemental material). Culture supernatants are prepared in the absence of any protease inhibitors, as they would impede parasite egress itself, and this does lead to the possibility of parasite proteins undergoing proteolytic cleavage yielding fragments of different sizes (21, 22, 28).

FIG 2.

Erythrocyte binding activity of the native PfRH5 parasite protein and recombinant rPfRH563 protein. Anti-PfRH5 antibodies in immunoblots detected both native PfRH5 and rPfRH563 among the proteins that bound with the erythrocyte surface and got eluted off by 1.5 M NaCl. (A) Native PfRH5 from the 3D7 culture supernatant bound untreated (U) and all three enzymatically treated human erythrocytes (neuraminidase [N], trypsin [T], and chymotrypsin [C]) but failed to bind with proteinase K (PK)-treated erythrocytes. Thus, PfRH5 binds erythrocytes in a sialic acid-independent, trypsin- and chymotrypsin-resistant, proteinase K-sensitive manner. (B) rPfRH563 bound human erythrocytes with the same specificity as that of native PfRH5. (C and D) Native PfEBA-175 (C) and PfF2 (recombinant receptor binding domain of PfEBA-175) (D) were analyzed as a control with the same set of enzymatically treated erythrocytes. Both native PfEBA-175 and PfF2 bound erythrocytes in a neuraminidase-, trypsin-, and proteinase K-sensitive and chymotrypsin-resistant manner. PBS (pH 7.4) contained no protein. No specific protein was detected in the eluate fractions with the PBS control, suggesting that no nonspecific erythrocyte protein was being detected in the assay.

The full-length, wild-type PfRH5 recombinant protein, rPfRH563, expressed in E. coli also exhibited an erythrocyte binding specificity that matched that of the native parasite protein (Fig. 2B). rPfRH563 specifically bound erythrocytes in a sialic acid-independent, trypsin- and chymotrypsin-resistant manner (Fig. 2B). Since the native and recombinant PfRH5 proteins bound erythrocytes treated with each of the three enzymes (neuraminidase, trypsin, and chymotrypsin), we also tested the effect of proteinase K treatment and found that binding of both native and recombinant PfRH5 was sensitive to proteinase K (Fig. 2A and B; see also Fig. S2C in the supplemental material).

As controls, both native PfEBA-175 from the parasite culture supernatant and recombinant PfF2, the receptor-binding domain of PfEBA-175, were found to bind erythrocytes in a sialic acid-dependent, trypsin-sensitive and chymotrypsin-resistant manner (Fig. 2C and D; see also Fig. S2D in the supplemental material), consistent with previous reports (31–33). In addition, no bound proteins were detected when the erythrocytes were incubated with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) alone (Fig. 2), thus confirming that no nonspecific erythrocyte protein was being detected in our assay and that the binding of PfRH5 or PfEBA-175 was specific.

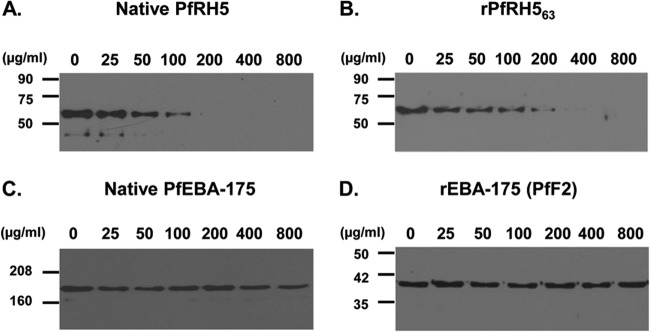

Antibodies against recombinant PfRH5 and basigin (BSG) block the erythrocyte binding activity of native PfRH5.

After demonstrating that rPfRH563 specifically bound erythrocytes, we determined whether anti-rPfRH563 antibodies could block the erythrocyte binding of native PfRH5 parasite protein. We demonstrated that total IgG purified from the sera of rabbits immunized with rPfRH563 blocked the erythrocyte binding of native PfRH5 (Fig. 3A). Total IgG containing anti-PfRH5 antibodies blocked binding of both the native and recombinant PfRH5 proteins with erythrocytes in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 3A and B). At a total IgG concentration of 200 μg/ml, the anti-PfRH5 IgG potently blocked the erythrocyte binding of both the native and recombinant PfRH5 proteins, whereas even at a concentration of 800 μg/ml the PfRH5 IgG had no effect on the erythrocyte binding of another parasite ligand, PfEBA-175 (Fig. 3C), or its recombinant receptor binding domain, PfF2 (Fig. 3D). This result clearly demonstrated that PfRH5 antibodies specifically recognized only PfRH5 and further abrogated its interaction with the erythrocyte surface.

FIG 3.

Antibodies against recombinant rPfRH563 blocked erythrocyte binding of both the native PfRH5 and rPfRH563 proteins. Purified total rabbit IgG against rPfRH563 blocked binding of native PfRH5 (A) and recombinant rPfRH563 (B) in a dose-dependent manner. The PfRH5 antibodies had no effect on the erythrocyte binding of native EBA-175 (C) or recombinant PfF2 (D) even at the maximum IgG concentration of 800 μg/ml.

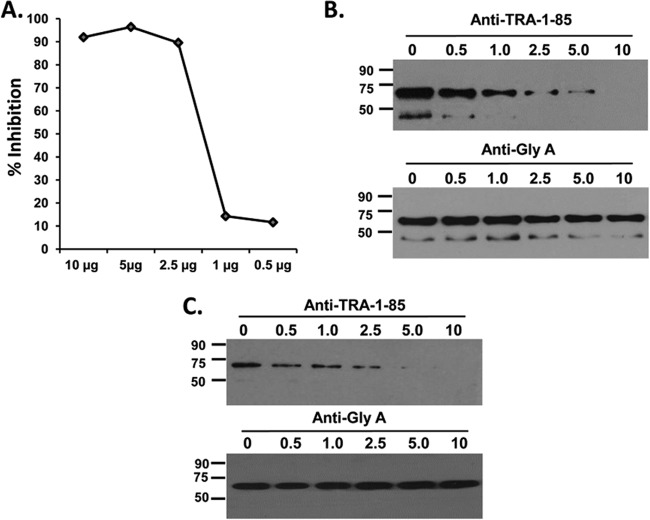

As described earlier, the erythrocyte receptor of PfRH5 was recently identified as the CD147 erythrocyte surface molecule, BSG (25). However, this elegant study had demonstrated this interaction with recombinant PfRH5 and not the native parasite protein. We tested the invasion-inhibitory activity of anti-BSG monoclonal antibodies (TRA-1-85; R&D Systems, USA) and found them to potently inhibit invasion, with 90% inhibition observed at a concentration of 2.5 μg/ml (Fig. 4A), consistent with the previous study (25). Further, we tested the ability of the anti-BSG monoclonal TRA-1-85 antibodies to block the erythrocyte binding of recombinant protein, rPfRH563, and native PfRH5 from parasite culture supernatants. Anti-BSG monoclonal TRA-1-85 antibodies potently blocked erythrocyte invasion from a minimum concentration of 2.5 μg/ml and from the same concentration, the binding of the native PfRH5 protein was also observed to be significantly reduced in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 4B). At 10 μg/ml, the anti-BSG monoclonal TRA-1-85 antibody completely abrogated the binding of both the native PfRH5 protein (Fig. 4B) and rPfRH563 (Fig. 4C). As a control, anti-glycophorin A monoclonal antibodies (Sigma-Aldrich) had no effect on the binding of the PfRH5 parasite protein (Fig. 4B and C), suggesting that the anti-BSG TRA-1-85 monoclonal antibodies were acting in a specific manner. This result substantiates the previous finding on PfRH5-BSG and demonstrates for the first time the interaction between BSG with the native PfRH5 parasite protein.

FIG 4.

Anti-basigin monoclonal antibodies blocked the erythrocyte binding of native and recombinant PfRH5. (A) Anti-basigin TRA-1-85 monoclonal antibodies potently inhibited invasion of human erythrocytes by the P. falciparum clone 3D7, with complete blockade of invasion observed at 5 μg/ml. At the same invasion-inhibitory IgG concentrations, the TRA-1-85 monoclonal antibodies potently blocked the erythrocyte binding of both the native PfRH5 protein (B) and recombinant rPfRH563 (C). Anti-glycophorin A monoclonal antibodies had no effect on the binding of either native (B) or recombinant (C) PfRH5.

Antibodies against recombinant PfRH5 potently block erythrocyte invasion by multiple P. falciparum clones.

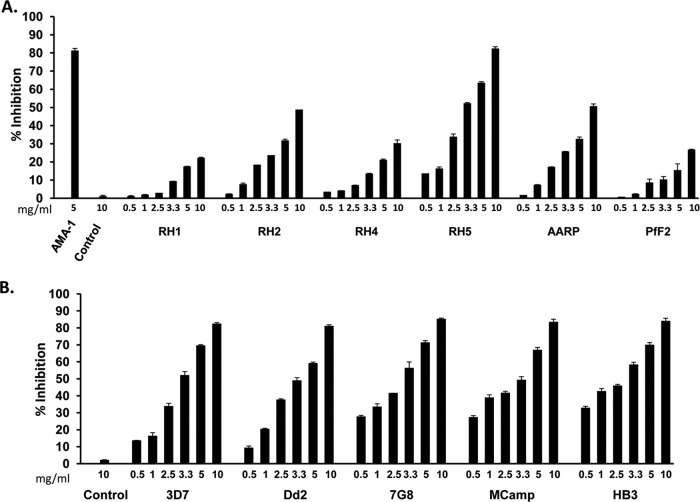

PfRH5 is the only parasite ligand among the EBA/PfRH families that is essential for erythrocyte invasion (21, 22). We thus compared the invasion-inhibitory activity of PfRH5 antibodies with that of antibodies raised against five other parasite ligands from our antigen portfolio—PfRH1, PfRH2, PfRH4, PfAARP (P. falciparum apical asparagine-rich protein), and PfF2 (F2 is the receptor binding domain of PfEBA-175)—as described previously (16, 20, 29, 32, 34). The total rabbit IgGs (0.5 to 10 mg/ml) purified from the sera of rabbits individually immunized with one of the six antigens were tested in standard one-cycle in vitro invasion inhibition assays (Fig. 5A) as described in our previous report (29). The invasion inhibition of the six antibodies was tested against the P. falciparum clone 3D7, which invades using both sialic acid-dependent and -independent pathways (Fig. 5A). All antibodies exhibited a dose-dependent inhibition that suggested a specific effect (Fig. 5A). The invasion inhibition for each IgG was calculated with respect to the preimmune IgG obtained from the same rabbit. In addition, as another negative control, we tested the invasion-inhibitory activity of purified rabbit total IgG against a nonrelated peptide from a human pancreatic RNase (HPR) that was also formulated with the same Freund's adjuvant. The anti-HPR IgG failed to exhibit any invasion inhibition at the maximum concentration of 10 mg/ml (Fig. 5A). The anti-HPR negative control has been tested in each assay reported in this article.

FIG 5.

Invasion-inhibitory activity of anti-PfRH5 rabbit antibodies. (A) Invasion-inhibitory activity of purified rabbit total IgG (0.5 to 10 mg/ml) against rPfRH563 and the receptor binding domains of other key merozoite ligands (PfRH1, PfRH2, PfRH4, PfAARP, and PfF2) against the P. falciparum clone 3D7. AMA-1 IgG (5 mg/ml) was used as a positive control. (B) Strain-transcending parasite neutralization activity of anti-PfRH5 total rabbit IgG (0.5 to 10 mg/ml) against five diverse P. falciparum clones. The control anti-HPR total IgG failed to exhibit any invasion inhibition at the maximum concentration of 10 mg/ml. The results represent the averages of three independent experiments performed in duplicate. The error bars represent the standard errors of the means.

Among all six antibodies, PfRH5 total IgG was found to elicit maximum inhibition of erythrocyte invasion, with ∼83% inhibition at 10 mg/ml, followed by PfAARP IgG (51%, 10 mg/ml) and PfRH2 IgG (49%, 10 mg/ml) (Fig. 5A). PfRH5 total IgG exhibited an invasion inhibition of 63% at 5 mg/ml and 52% at 3.3 mg/ml (Fig. 5A). The variation in inhibitory activity among the different antibodies could not be attributed to any disparity in their titers. The endpoint antibody titers against all the six proteins immunized in rabbits were in the range of 1:320,000 (data not shown). As mentioned above, we had raised antibodies against PfRH5 in three rabbits that had shown equivalent endpoint titers in the range of 1:320,000. The purified total IgG from the other two rabbits also exhibited a potent invasion inhibitory activity against the P. falciparum clone 3D7 (see Fig. S4A in the supplemental material), similar to that observed with the anti-PfRH5 IgG from rabbit 1 (Fig. 5A).

We further analyzed the strain-transcending invasion-inhibitory activity of the PfRH5 antibodies (rabbit 1) against five P. falciparum strains that originate from different regions of the world and express different polymorphic variants of the PfRH5 parasite protein (see Table S3 in the supplemental material) (21). In addition, these P. falciparum strains exhibit a variation in their invasion phenotype by utilizing different ligand receptor interactions and pathways for invading human erythrocytes (see Table S3) (2–4, 29, 33, 35). The invasion phenotypes of the P. falciparum clones are classified in the literature on the basis of their invasion sensitivity to enzymatic treatments of the target erythrocytes (2–4, 29, 33, 35). Thus, the five parasite clones represent diversity both at the level of PfRH5 antigenic polymorphisms and at the level of the phenotypic variation in the invasion properties of the parasite clones (see Table S3). The strains 3D7, HB3 and 7G8 are known to invade through sialic acid-independent pathways (3, 33, 35), whereas Dd2 and MCamp are completely dependent on sialic acids for erythrocyte invasion (3, 33, 35). The anti-PfRH5 antibodies (rabbit 1) were found to potently inhibit erythrocyte invasion of all five P. falciparum clones (Fig. 5B). The purified PfRH5 total IgG exhibited 81 to 85% invasion inhibition among the five parasite clones at a concentration of 10 mg/ml (Fig. 5B), which is comparable with the maximum inhibition that we recently reported with an antibody combination against three antigens, PfAARP-PfRH2-PfF2 (29). The invasion-inhibitory activity was dose dependent, as reported earlier, with inhibition rates of 60 to 71% at 5 mg/ml, 49 to 59% at 3.3 mg/ml, and 34 to 46% at 2.5 mg/ml (Fig. 5B). Similar potent strain-transcending invasion inhibition was also observed with total IgG purified from the sera of the other two rabbits immunized with rPfRH563 (data not shown). Our PfRH5 antibodies exhibited a 50% inhibition of erythrocyte invasion at a total IgG concentration (EC50) of ∼3 mg/ml, which is consistent with previous studies that have reported EC50s for anti-PfRH5 IgG obtained from different rabbits within a concentration range of 0.7 to 4 mg/ml against multiple P. falciparum strains (26, 27, 36).

The purified total IgG from five individual rats also exhibited a potent dose-dependent invasion inhibition of the P. falciparum clone 3D7, with the maximum inhibition of around 72 to 77% at a 10-mg/ml concentration (see Fig. S4B in the supplemental material). The specificity of the invasion inhibition by PfRH5 rat IgG was validated by reversing it with the addition of the recombinant rPfRH563 in the assay. Addition of rPfRH563 at a concentration of 50 μg/ml significantly reduced the invasion inhibition observed with 5 mg/ml of PfRH5 IgG, by 80% (see Fig. S4C). On the other hand, addition of PfF2 at the same concentration had no effect on the invasion-inhibitory activity of the PfRH5 antibodies (see Fig. S4C).

Thus, not only within the PfRH family but also compared to other major parasite ligands, PfRH5 is a potent target of specific antibody-mediated blockade of erythrocyte invasion and appears to have a dominant role in the erythrocyte invasion process. Therefore, antibodies raised against a functional recombinant protein expressed in E. coli representing the wild-type full-length sequence of PfRH5 have proven to be as potent in blocking parasite invasion as reported earlier with antibodies raised by adenoviral vectors (26, 36) or the mutated PfRH5-rat CD4(d3 + 4) fusion protein (27).

PfRH5-based antibody combinations produce an additive inhibition of erythrocyte invasion by P. falciparum.

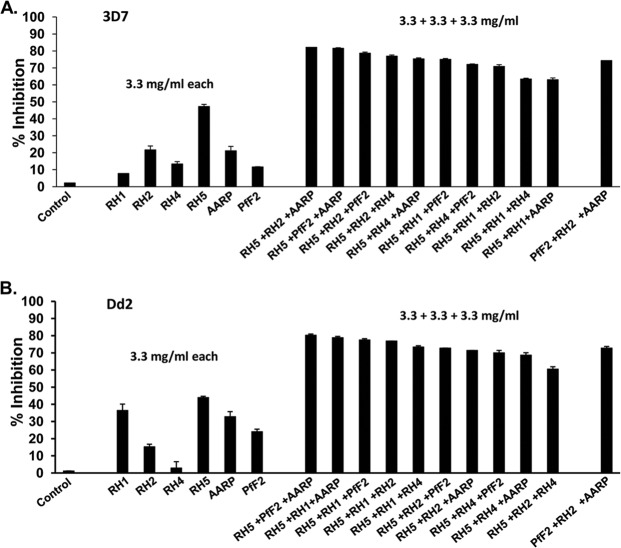

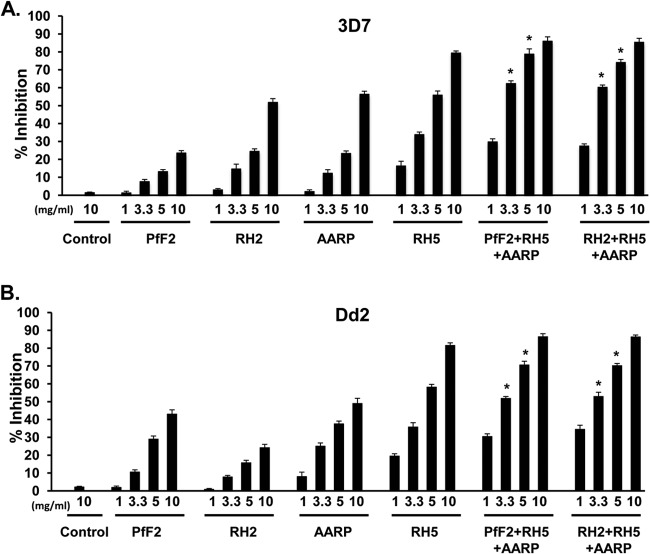

In a recent study, we identified a potent antigen combination (PfAARP-PfRH2-PfF2) that elicits strain-transcending invasion-inhibitory antibodies (29). Through this study, we had demonstrated that triple-antibody combinations were more efficacious in inhibiting erythrocyte invasion than double-antibody combinations (29). That study did not include PfRH5, so we wanted to now analyze whether PfRH5-based triple-antibody combinations would also be effective in producing additive inhibition of invasion at lower individual IgG concentrations. In this regard, we tested the invasion inhibition of 10 PfRH5-based triple-antibody combinations that comprised purified total IgG (3.3 mg/ml of each antigen; total, 10 mg/ml) against PfRH5 (rabbit 1) and two other antigens from our portfolio (PfRH1, PfRH2, PfRH4, PfAARP, and PfF2) generated previously (29). The invasion inhibition was first assessed against two P. falciparum strains (3D7 and Dd2) (Fig. 6), and then the six most efficacious antibody combinations were further analyzed against a total of five P. falciparum strains (3D7, Dd2, 7G8, MCamp, and HB3) (Fig. 7) to ascertain whether the antibody combinations elicited strain-transcending activity.

FIG 6.

Invasion-inhibitory efficacy of PfRH5-based antibody combinations against P. falciparum clones (3D7 and Dd2). Purified rabbit total IgG against the six individual antigens (PfRH1, PfRH2, PfRH4, PfRH5, PfAARP, and PfF2) were evaluated individually (3.3 mg/ml) as well as in all 10 possible PfRH5-based triple-antibody combinations (3.3 mg/ml each; total, 10 mg/ml) against the sialic acid-independent clone 3D7 (A) and the sialic acid-dependent clone Dd2 (B). The control anti-HPR total IgG failed to exhibit any invasion inhibition at the maximum concentration of 10 mg/ml. The results represent the averages of three independent experiments performed in duplicate. The error bars represent the standard errors of the means.

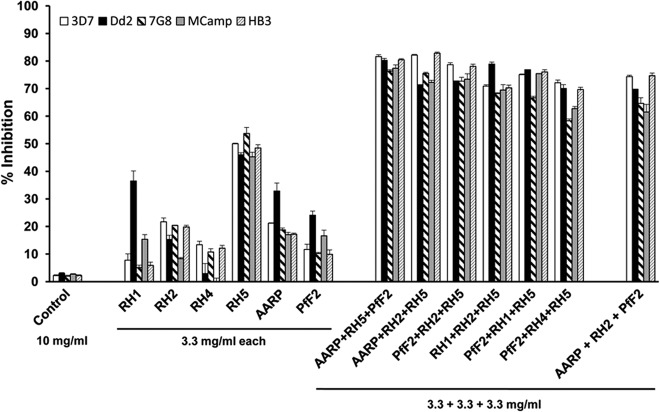

FIG 7.

Strain-transcending parasite neutralization of PfRH5-based antibody combinations. Purified rabbit total IgGs against the six individual antigens (PfRH1, PfRH2, PfRH4, PfRH5, PfAARP, and PfF2) were evaluated individually and in the six most potent PfRH5-based antibody combinations (identified from Fig. 6) against five diverse P. falciparum clones. The invasion-inhibitory activity of the antibody combination AARP-RH2-PfF2 was also analyzed in the assay. The control anti-HPR total IgG failed to exhibit any invasion inhibition at the maximum concentration of 10 mg/ml. Three independent assays were performed in duplicate. The error bars represent the standard errors of the means.

Individually, the six antibodies at 3.3 mg/ml exhibited a broad range of invasion inhibition, of 3 to 54%, against all five parasite clones (Fig. 6 and 7). As described above, anti-PfRH5 IgG displayed maximum inhibition against all strains (44 to 54%), followed by anti-PfAARP IgG (17 to 33%) (Fig. 6 and 7). Consistent with previous findings, anti-PfRH1 and anti-PfF2 IgG were more efficacious in blocking the sialic acid-dependent clones—Dd2 (24 to 36%) and MCamp (15 to 17%)—and not the sialic acid-independent clones—3D7 (8 to 12%), 7G8 (5 to 10%), and HB3 (5 to 10%) (Fig. 6 and 7). Similarly, PfRH2 IgG and PfRH4 IgG efficiently blocked only the sialic acid-independent clones and not the sialic acid-dependent clones, in which they are poorly expressed.

The different anti-PfRH5-based antibody combinations displayed potent inhibition of erythrocyte invasion by the 3D7 parasite clone (Fig. 6A), with the maximum inhibition observed with three antibody combinations, PfAARP-PfRH2-PfRH5 (82%), PfF2-PfRH5-PfAARP (82%), and PfF2-PfRH2-PfRH5 (79%). In line with the utilization and expression of the different PfRH ligands, we observed that the maximum inhibition with the Dd2 parasite clone was by the antibody combinations PfRH5-PfF2-PfAARP (81%), PfRH5-PfRH1-PfAARP (79%), and PfRH5-PfRH1-PfF2 (78%) (Fig. 6B). This is consistent with the higher expression and utilization of the sialic acid binding ligands (PfRH1, PfF2, and PfAARP) for erythrocyte invasion by sialic acid-dependent parasite clones such as Dd2. We further tested invasion inhibition of the six best PfRH5-based antibody combinations against five P. falciparum clones that originate from diverse regions of the world and exhibit different invasion phenotypes as well.

The six antibody combinations were potent in blocking invasion of all five parasite clones, with the antibody combinations PfRH5-PfF2-PfAARP (77 to 82%), PfRH5-PfRH2-PfAARP (71 to 83%), and PfF2-PfRH2-PfRH5 (72 to 79%) eliciting the most efficacious strain-transcending invasion-inhibitory activities (Fig. 7). We also tested as a control the PfAARP-PfF2-PfRH2 antibody combination, which we had previously reported (29) as our most efficacious antibody combination (Fig. 7). While this antibody combination does elicit strain-transcending activity, the combination PfRH5-PfF2-PfAARP appeared to be slightly more efficient in its overall strain-transcending activity against all five P. falciparum clones, which is consistent with the observation that PfRH5 antibodies individually were observed to be most efficient among the different parasite ligands in blocking erythrocyte invasion. However, the difference in invasion inhibitory activity between the PfRH5-PfF2-PfAARP and PfAARP-PfF2-PfRH2 antibody combinations was not statistically significant (P > 0.05).

Coimmunized antigen mixtures also elicit potent strain-transcending invasion-inhibitory antibodies.

After evaluating antibody combinations that were mixed in vitro for their invasion-inhibitory activities, we wanted to test whether the most potent combination identified would elicit similar invasion-inhibitory antibodies when coimmunized together as a single formulation. In this next step, the PfRH5-based triple-antigen mixtures (PfRH5-PfRH2-PfAARP and PfRH5-PfF2-PfAARP) were used to immunize mice (BALB/c). The individual antigens in each combination were also used to immunize mice separately. All antigens were formulated with CFA or IFA. The ELISA results (OD492) showed that the titers of antibody (endpoint 1:320,000) against each protein immunized individually were not significantly altered when the proteins were immunized as a mixture with the two other antigens (see Fig. S5 in the supplemental material). The immunogenicity curves for PfRH5, PfRH2, PfF2, and PfAARP were identical and overlapping whether the antigens were immunized alone or in their respective combinations (see Fig. S5). Thus, our recombinant antigens, including rPfRH563, were immunogenic and did not elicit any significant immune interference when immunized in combination.

Consistent with the invasion inhibition observed with the antibody combinations physically added in vitro, the antibodies raised against the antigen mixtures were highly potent and equally efficient in inhibiting erythrocyte invasion (Fig. 8; see also Fig. S6 in the supplemental material). The antibodies against the two antigen mixtures displayed 71 to 79% and ∼86% inhibition of the P. falciparum clones (3D7 and Dd2) at concentrations of 5 and 10 mg/ml, respectively (Fig. 8). The antibodies displayed a similar potent inhibition of three more parasite clones at an IgG concentration of 10 mg/ml (see Fig. S6). Thus, antibodies raised against coimmunized antigen mixtures were as potent in efficiently blocking erythrocyte invasion as antibodies physically combined (Fig. 6 and 7) in the in vitro invasion inhibition assays.

FIG 8.

Invasion-inhibitory activities of antibodies raised against the two coimmunized antigen formulations. Total IgG purified from mouse sera raised against the immunogens (RH5, RH2, PfF2, AARP, PfF2-RH5-AARP, and RH2-RH5-AARP) was evaluated for its invasion-inhibitory activity (at concentrations of 1, 3.3, 5, and 10 mg/ml) against the sialic acid-independent clone 3D7 (A) and the sialic acid-dependent clone Dd2 (B). The control anti-HPR total IgG failed to exhibit any invasion inhibition at the maximum concentration of 10 mg/ml. Two independent assays were performed in duplicate. The error bars show the standard errors of the mean. An asterisk denotes statistical significance between the invasion inhibition produced by the antibodies against the two antigen mixtures (PfF2-RH5-AARP and RH2-RH5-AARP) with respect to the individual PfRH5 antibodies at the same concentrations of purified total IgG, 3.3 mg/ml and 5 mg/ml (P < 0.05).

DISCUSSION

Parasite-neutralizing antibodies that block P. falciparum erythrocyte invasion are one of the key effector mechanisms known to mediate immunity against blood-stage malaria parasites and are the fundamental basis for the development of blood-stage malaria vaccines. The ability to impede erythrocyte invasion by P. falciparum merozoites can be quantitated in an in vitro invasion inhibition or growth inhibition assay (GIA) that has been widely reported in the field. A significant association of invasion inhibition measured in vitro with a reduced risk of malaria has also been reported previously (37, 38), and thus, in vitro invasion-inhibition appears to be a useful surrogate marker to predict the functional efficacy of antibodies induced by a blood-stage vaccine. In spite of the extensive research on the parasite biology of P. falciparum, it has been difficult to demonstrate potent invasion-inhibitory activity, with the exception of antibodies against apical membrane antigen 1 (AMA-1) (39, 40). The challenge in generating potent invasion-inhibitory antibodies that have hindered the development of blood-stage malaria vaccines against P. falciparum could be attributed to the enormous complexity of the parasite, which has evolved redundancy in parasite ligands that enables invasion of diverse types of human erythrocytes (2–4). As a result, no human erythrocyte is known to be totally refractory to invasion by P. falciparum. Another level of complexity is the high level of antigenic polymorphisms that mediates immune escape, which has proven to be a major impediment in developing leading antigens such as AMA-1 and MSP-142 as blood-stage vaccines (5–7). Both antigens have failed to elicit optimal efficacy in field trials (5, 6).

Thus, to fully realize the potential of a candidate blood-stage antigen, it is not sufficient to just show that the antigen elicits strong invasion-inhibitory antibodies that block the parasite in vitro. A good example is AMA-1, an essential parasite protein involved in the critical step of junction formation during erythrocyte invasion (41, 42), which has been demonstrated in vitro to induce potent invasion-inhibitory antibodies only against homologous parasite strains and not against heterologous strains (39, 40). This inability has been attributed to high levels of antigenic polymorphisms in AMA-1 among different parasite strains that render its antibodies to be ineffective against heterologous P. falciparum strains (39, 43, 44). Unfortunately, due to the problem of inducing allele-specific immunity, AMA-1 has not yielded protection against malaria in vaccine efficacy trials (7, 45).

Therefore, it is crucial that potent strain-transcending invasion inhibition be demonstrated with the antibodies against a particular antigen that is being considered for clinical development of a malaria vaccine. This problem has been reported to be overcome by targeting combinations of different conserved parasite antigens or a number of different AMA-1 allelic proteins that produce strong efficacious invasion inhibition in a strain-transcending manner (29, 46).

The disappointing results of a number of blood-stage vaccine trials has raised the concern of whether the in vitro invasion inhibition assay or GIA has any correlation with clinical protection or could predict vaccine efficacy in humans (47). Unfortunately, only a few blood-stage antigens have been tested in field efficacy trials. Due to the problems cited above, more studies with parasite antigens that induce potent strain-transcending invasion inhibition are thus required to validate the correlation of in vitro invasion-inhibitory activity with clinical protection in humans. It would thus be beneficial to validate the in vitro invasion inhibitory assay or GIA with in vivo controlled human malaria infection (CHMI) studies using either a sporozoite or blood-stage challenge model (47). However, the in vitro invasion-inhibitory assay or GIA remains as the only currently available laboratory assay to measure the functionality of antibodies to inhibit erythrocyte invasion by Plasmodium merozoites. In this regard, this assay has been successful in differentiating between invasion-inhibitory and noninhibitory antibodies against a number of P. falciparum antigens, as not all antibodies exhibit potent invasion inhibitory activity. Hence, the in vitro invasion inhibition or GIA clearly appears to be an informative assay which in preclinical studies can identify and validate novel, efficacious P. falciparum blood-stage targets that elicit strain-transcending invasion-inhibitory antibodies.

The past decade has seen a huge body of research conducted on understanding the molecular basis of erythrocyte invasion and characterizing numerous antigens from the large repertoire developed by P. falciparum (2–4, 8, 9). With respect to vaccine development, the goal to search for promising antigens has shifted to the identification of relatively conserved antigens that elicit potent strain-transcending invasion-inhibitory antibodies. Among the parasite's large molecular arsenal, the PfRH proteins have been identified as key determinants of different invasion pathways used by P. falciparum (2–4, 8, 9), of which PfRH5 is the only erythrocyte binding ligand known to be essential for the parasite, as its gene is refractory for disruption (22). The importance of PfRH5 has been substantiated by the fact that antibodies against both PfRH5 and its erythrocyte receptor, basigin, potently inhibit erythrocyte invasion by a number of P. falciparum strains from diverse worldwide locations that also exhibit different invasion phenotypes (25–27). The efficacious neutralization of heterologous parasite clones by PfRH5 antibodies raised first through a viral vector-based prime-boost strategy had demonstrated that PfRH5 is a highly promising blood-stage vaccine candidate (26). Our goal was to demonstrate the production of a potent functional wild-type full-length PfRH5 recombinant antigen that could be used for the development of a subunit blood-stage malaria vaccine which would have the potential to be tested individually as well as in combination with other blood-stage antigens and possibly even pre-erythrocytic malaria vaccines such as RTS,S (48). RTS,S is the most advanced malaria vaccine currently being tested in a phase III clinical trial in Africa (49, 50). It is a subunit recombinant vaccine based on the CSP-HbSAg fusion protein, which assembles into virus-like particles (48–50).

In this regard, we have produced the full-length, wild-type PfRH5 recombinant protein without making any alterations to its sequence in a bacterial organism, E. coli. The recombinant protein binds with erythrocytes with the same specificity as that of the native parasite protein and anti-basigin monoclonal antibodies specifically blocked the binding of the recombinant protein. This binding was unaffected by other monoclonal antibodies against another major erythrocyte receptor, glycophorin A. All these results strongly suggest that the recombinant PfRH5 was produced with a conformational integrity that mimics that of the native parasite protein. This work paves the way for a more detailed structure-function analysis of PfRH5 that would not only improve our understanding of its role in the basic biology of the parasite but also help in designing a more efficacious PfRH5 immunogen for vaccine development.

While it was very elegantly demonstrated that PfRH5 binds with basigin (25), this report did not show any data with regard to the interaction of the native PfRH5 parasite protein and based its inferences on the interaction with a pentamer of the biotinylated recombinant PfRH5-rat CD4(d3 + 4) fusion protein. In the present study, we have demonstrated that the basigin monoclonal antibodies at the same concentration at which they blocked erythrocyte invasion also completely inhibited the erythrocyte binding of the native PfRH5 parasite protein obtained from culture supernatants. Our data strongly support the previous study showing that the native PfRH5 parasite protein binds with the erythrocyte surface molecule basigin.

Further, most importantly, the antibodies raised against recombinant PfRH5 specifically inhibited erythrocyte invasion of heterologous P. falciparum strains, with potent efficiencies as high as 85% and 71% at total IgG concentrations of 10 mg/ml and 5 mg/ml, respectively. PfRH5 antibodies were observed to be most potent among a pool of antibodies (0.5 to 10 mg/ml of total IgG) tested against six antigens in our portfolio that included four PfRH proteins (PfRH1, PfRH2, PfRH4, and PfRH5), PfEBA-175 (PfF2), and PfAARP (29). The normal physiological total IgG concentration in human serum is in the range of 10 to 14 mg/ml (51). Thus, we have analyzed our antibodies at a maximum total IgG concentration of 10 mg/ml, which is on the lower end of the human physiological concentration. The specific component of the anti-PfRH5 IgG within the total serum IgG (10 mg/ml) would be a much smaller fraction and should be achievable through a human vaccine. In addition, PfRH5 antibodies exhibited the maximum cross-strain neutralizing activity, as they were efficacious in blocking a number of P. falciparum clones that display phenotypic variation in their invasion pathways. Our invasion inhibition results are consistent with previous reports of PfRH5 antibodies raised through viral vectors (26) or against the PfRH5-rat CD4(d3 + 4) fusion protein (27). In our assays, the rPfRH563 antibodies exhibited an EC50 of ∼3 mg/ml, whereas previous studies with viral vectors and PfRH5-rat CD4(d3 + 4) fusion protein have shown EC50s with anti-PfRH5 IgG obtained from different rabbits at a broad concentration range of 0.7 to 4 mg/ml against multiple P. falciparum strains (26, 27, 36). The difference in invasion-inhibitory activity could be attributed to the different nature of the PfRH5 immunogen used in the studies as well as the fact that different animals were used in the studies to raise the PfRH5-specific antibodies. Outbred animals are known to exhibit large differences in their immune responses and especially when located in different geographical areas.

As stated previously, achieving highly potent strain-transcending invasion-inhibitory antibodies against conserved functional domains of parasite antigens involved in invasion may be the key to the development of an effective blood-stage malaria vaccine. This has been difficult to achieve by targeting single antigens, with the exception of PfRH5 as reported here and in previous reports. Earlier potent strain-transcending invasion-inhibitory antibodies were demonstrated only by targeting combinations of key merozoite antigens involved in erythrocyte invasion (24, 29, 36, 46, 52).

In line with these reports, we feel that targeting single antigens may not be an effective long-term strategy for malaria vaccines, as the parasite has the strong ability to develop escape mechanisms to counter the immune pressure. This capability is well displayed in the rapid development of resistance in the parasite under drug pressure that has prompted only combinatorial antimalarial drug therapies. Moreso in combination, antibodies neutralize the parasite at lower individual IgG concentrations (3.3 mg/ml of total IgG each) that would be easier to achieve using human-compatible adjuvants or delivery platforms. PfRH5 antibodies in combination with those against PfRH2, PfAARP, and PfF2 produced an additive inhibition of erythrocyte invasion. Our data are consistent with a previous study that has reported a potent synergy in invasion inhibition by adenoviral vector induced antibodies against PfRH5 and other EBA/PfRH antigens (36). We have also demonstrated that these PfRH5-based coimmunized antigen mixtures induce balanced antibody responses against all three antigens with no immune interference. Purified total IgGs against the antigen mixtures were as potent in inhibiting erythrocyte invasion as the antibodies combined in vitro.

Thus, our study establishes a proof of principle for the production of full-length wild-type recombinant PfRH5 in a bacterial expression system that is known to be scalable for mass vaccine production and has the potential to be taken forward for its development as a component of a subunit blood-stage combination malaria vaccine. However, we have demonstrated potent invasion-inhibitory antibodies against PfRH5 raised through Freund's formulations that are known to induce very strong immune responses but are not safe for human vaccine applications. Thus, it is imperative for the clinical development of recombinant PfRH5 as a malaria vaccine to identify human-compatible adjuvants or delivery platforms that would also elicit similar highly potent neutralizing antibodies. Nevertheless, the production of the wild-type full-length recombinant PfRH5 protein with no amino acid modifications further enables the structure-function analysis of this highly efficacious and attractive blood-stage malaria vaccine candidate.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Louis Miller (NIH) for providing the P. falciparum clones used in this study and the rPfRH430 expression plasmid. We also thank Lee Hall and Annie Mo from the Parasitology and International Programs Branch (PIPB), NIAID, NIH, for providing the recombinant EBA-175 RII protein. The technical assistance of Alka Galav, Rakesh Kumar Singh, and Ashok Das from the ICGEB animal facility in performing the animal experiments is deeply appreciated. We thank Inderjeet Kaur at the mass spectrometry facility of the Malaria Group, ICGEB, for helping us with the LC-MS analysis. We appreciate Surbhi Dabral at the superresolution imaging facility of the Malaria Group, ICGEB, for technical help in our imaging study.

Deepak Gaur is the recipient of the Ramalingaswami Fellowship from the Department of Biotechnology, Government of India. Deepak Gaur is also the recipient of the Grand Challenges Exploration Grant from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. This work was supported by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation through the Grand Challenges Explorations Initiative (GCE OPP1007027 to D.G.); Department of Biotechnology (DBT), Government of India, through the Ramalingaswami fellowship program (BT/HRD/35/02/14/2008 to D.G.), Rapid Grant Scheme for Young Investigators (BT/PR13376/GBD/27/260/2009 to D.G.), and Vaccine Grand Challenges Program (ND/DBT/12/040 to D.G., C.E.C., and V.S.C.). K.S.R. and T.S. are recipients of Senior Research Fellowships of the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research, Government of India; A.K.P. is the recipient of a postdoctoral research associateship of the DBT; and H.S. is the recipient of a senior research fellowship of the DBT. A.E. is the recipient of an ICGEB international Ph.D. predoctoral fellowship. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

D.G., V.S.C., and C.E.C. are named on patent applications relating to PfRH5 and/or other malaria vaccines.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 14 October 2013

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/IAI.00970-13.

REFERENCES

- 1.Murray CJ, Rosenfeld LC, Lim SS, Andrews KG, Foreman KJ, Haring D, Fullman N, Naghavi M, Lozano R, Lopez AD. 2012. Global malaria mortality between 1980 and 2010: a systematic analysis. Lancet 379:413–431. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60034-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gaur D, Chitnis CE. 2011. Molecular interactions and signaling mechanisms during erythrocyte invasion by malaria parasites. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 14:422–428. 10.1016/j.mib.2011.07.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gaur D, Mayer DC, Miller LH. 2004. Parasite ligand-host receptor interactions during invasion of erythrocytes by Plasmodium merozoites. Int. J. Parasitol. 34:1413–1429. 10.1016/j.ijpara.2004.10.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cowman AF, Crabb BS. 2006. Invasion of red blood cells by malaria parasites. Cell 124:755–766. 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ogutu BR, Apollo OJ, McKinney D, Okoth W, Siangla J, Dubovsky F, Tucker K, Waitumbi JN, Diggs C, Wittes J, Malkin E, Leach A, Soisson LA, Milman JB, Otieno L, Holland CA, Polhemus M, Remich SA, Ockenhouse CF, Cohen J, Ballou WR, Martin SK, Angov E, Stewart VA, Lyon JA, Heppner DG, Withers MR. 2009. Blood stage malaria vaccine eliciting high antigen-specific antibody concentrations confers no protection to young children in Western Kenya. PLoS One 4:e4708. 10.1371/journal.pone.0004708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Spring MD, Cummings JF, Ockenhouse CF, Dutta S, Reidler R, Angov E, Bergmann-Leitner E, Stewart VA, Bittner S, Juompan L, Kortepeter MG, Nielsen R, Krzych U, Tierney E, Ware LA, Dowler M, Hermsen CC, Sauerwein RW, de Vlas SJ, Ofori-Anyinam O, Lanar DE, Williams JL, Kester KE, Tucker K, Shi M, Malkin E, Long C, Diggs CL, Soisson L, Dubois MC, Ballou WR, Cohen J, Heppner DG., Jr 2009. Phase 1/2a study of the malaria vaccine candidate apical membrane antigen-1 (AMA-1) administered in adjuvant system AS01B or AS02A. PLoS One 4:e5254. 10.1371/journal.pone.0005254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thera MA, Doumbo OK, Coulibaly D, Laurens MB, Ouattara A, Kone AK, Guindo AB, Traore K, Traore I, Kouriba B, Diallo DA, Diarra I, Daou M, Dolo A, Tolo Y, Sissoko MS, Niangaly A, Sissoko M, Takala-Harrison S, Lyke KE, Wu Y, Blackwelder WC, Godeaux O, Vekemans J, Dubois MC, Ballou WR, Cohen J, Thompson D, Dube T, Soisson L, Diggs CL, House B, Lanar DE, Dutta S, Heppner DG, Jr, Plowe CV. 2011. A field trial to assess a blood-stage malaria vaccine. N. Engl. J. Med. 365:1004–1013. 10.1056/NEJMoa1008115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tham WH, Healer J, Cowman AF. 2012. Erythrocyte and reticulocyte binding-like proteins of Plasmodium falciparum. Trends Parasitol. 28:23–30. 10.1016/j.pt.2011.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cowman AF, Berry D, Baum J. 2012. The cellular and molecular basis for malaria parasite invasion of the human red blood cell. J. Cell Biol. 198:961–971. 10.1083/jcb.201206112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rayner JC, Vargas-Serrato E, Huber CS, Galinski MR, Barnwell JW. 2001. A Plasmodium falciparum homologue of Plasmodium vivax reticulocyte binding protein (PvRBP1) defines a trypsin-resistant erythrocyte invasion pathway. J. Exp. Med. 194:1571–1581. 10.1084/jem.194.11.1571 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Triglia T, Duraisingh MT, Good RT, Cowman AF. 2005. Reticulocyte-binding protein homologue 1 is required for sialic acid-dependent invasion into human erythrocytes by Plasmodium falciparum. Mol. Microbiol. 55:162–174. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04388.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rayner JC, Galinski MR, Ingravallo P, Barnwell JW. 2000. Two Plasmodium falciparum genes express merozoite proteins that are related to Plasmodium vivax and Plasmodium yoelii adhesive proteins involved in host cell selection and invasion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97:9648–9653. 10.1073/pnas.160469097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Duraisingh MT, Triglia T, Ralph SA, Rayner JC, Barnwell JW, McFadden GI, Cowman AF. 2003. Phenotypic variation of Plasmodium falciparum merozoite proteins directs receptor targeting for invasion of human erythrocytes. EMBO J. 22:1047–1057. 10.1093/emboj/cdg096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaneko O, Mu J, Tsuboi T, Su X, Torii M. 2002. Gene structure and expression of a Plasmodium falciparum 220-kDa protein homologous to the Plasmodium vivax reticulocyte binding proteins. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 121:275–278. 10.1016/S0166-6851(02)00042-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gao X, Yeo KP, Aw SS, Kuss C, Iyer JK, Genesan S, Rajamanonmani R, Lescar J, Bozdech Z, Preiser PR. 2008. Antibodies targeting the PfRH1 binding domain inhibit invasion of Plasmodium falciparum merozoites. PLoS Pathog. 4:e1000104. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sahar T, Reddy KS, Bharadwaj M, Pandey AK, Singh S, Chitnis CE, Gaur D. 2011. Plasmodium falciparum reticulocyte binding-like homologue protein 2 (PfRH2) is a key adhesive molecule involved in erythrocyte invasion. PLoS One 6:e17102. 10.1371/journal.pone.0017102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Triglia T, Chen L, Lopaticki S, Dekiwadia C, Riglar DT, Hodder AN, Ralph SA, Baum J, Cowman AF. 2011. Plasmodium falciparum merozoite invasion is inhibited by antibodies that target the PfRh2a and b binding domains. PLoS Pathog. 7:e1002075. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stubbs J, Simpson KM, Triglia T, Plouffe D, Tonkin CJ, Duraisingh MT, Maier AG, Winzeler EA, Cowman AF. 2005. Molecular mechanism for switching of P. falciparum invasion pathways into human erythrocytes. Science 309:1384–1387. 10.1126/science.1115257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gaur D, Furuya T, Mu J, Jiang LB, Su XZ, Miller LH. 2006. Upregulation of expression of the reticulocyte homology gene 4 in the Plasmodium falciparum clone Dd2 is associated with a switch in the erythrocyte invasion pathway. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 145:205–215. 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2005.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gaur D, Singh S, Singh S, Jiang L, Diouf A, Miller LH. 2007. Recombinant Plasmodium falciparum reticulocyte homology protein 4 binds to erythrocytes and blocks invasion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104:17789–17794. 10.1073/pnas.0708772104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hayton K, Gaur D, Liu A, Henschen B, Singh S, Lambert L, Furuya T, Bouttenot R, Doll M, Nawaz F, Mu J, Jiang L, Miller LH, Wellems TE. 2008. Erythrocyte binding protein PfRH5 polymorphisms determine species-specific pathways of Plasmodium falciparum invasion. Cell Host Microbe 4:40–51. 10.1016/j.chom.2008.06.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baum J, Chen L, Healer J, Lopaticki S, Boyle M, Triglia T, Ehlgen F, Ralph SA, Beeson JG, Cowman AF. 2009. Reticulocyte-binding protein homologue 5—an essential adhesin involved in invasion of human erythrocytes by Plasmodium falciparum. Int. J. Parasitol. 39:371–380. 10.1016/j.ijpara.2008.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hayton K, Dumoulin P, Henschen B, Liu A, Papakrivos J, Wellems TE. 2013. Various PfRH5 polymorphisms can support Plasmodium falciparum invasion into the erythrocytes of owl monkeys and rats. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 187:103–110. 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2012.12.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen L, Lopaticki S, Riglar DT, Dekiwadia C, Uboldi AD, Tham WH, O'Neill MT, Richard D, Baum J, Ralph SA, Cowman AF. 2011. An EGF-like protein forms a complex with PfRh5 and is required for invasion of human erythrocytes by Plasmodium falciparum. PLoS Pathog. 7:e1002199. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Crosnier C, Bustamante LY, Bartholdson SJ, Bei AK, Theron M, Uchikawa M, Mboup S, Ndir O, Kwiatkowski DP, Duraisingh MT, Rayner JC, Wright GJ. 2011. Basigin is a receptor essential for erythrocyte invasion by Plasmodium falciparum. Nature 480:534–537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Douglas AD, Williams AR, Illingworth JJ, Kamuyu G, Biswas S, Goodman AL, Wyllie DH, Crosnier C, Miura K, Wright GJ, Long CA, Osier FH, Marsh K, Turner AV, Hill AV, Draper SJ. 2011. The blood-stage malaria antigen PfRH5 is susceptible to vaccine-inducible cross-strain neutralizing antibody. Nat. Commun. 2:601. 10.1038/ncomms1615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bustamante LY, Bartholdson SJ, Crosnier C, Campos MG, Wanaguru M, Nguon C, Kwiatkowski DP, Wright GJ, Rayner JC. 2013. A full-length recombinant Plasmodium falciparum PfRH5 protein induces inhibitory antibodies that are effective across common PfRH5 genetic variants. Vaccine 31(2):373–379. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.10.106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rodriguez M, Lustigman S, Montero E, Oksov Y, Lobo CA. 2008. PfRH5: a novel reticulocyte-binding family homolog of Plasmodium falciparum that binds to the erythrocyte, and an investigation of its receptor. PLoS One 3(10):e3300. 10.1371/journal.pone.0003300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pandey AK, Reddy KS, Sahar T, Gupta S, Singh H, Reddy EJ, Asad M, Siddiqui FA, Gupta P, Singh B, More KR, Mohmmed A, Chitnis CE, Chauhan VS, Gaur D. 2013. Identification of a potent combination of key Plasmodium falciparum merozoite antigens that elicit strain-transcending parasite-neutralizing antibodies. Infect. Immun. 81:441–451. 10.1128/IAI.01107-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Siddiqui FA, Dhawan S, Singh S, Singh B, Gupta P, Pandey A, Mohmmed A, Gaur D, Chitnis CE. 2013. A thrombospondin structural repeat containing rhoptry protein from Plasmodium falciparum mediates erythrocyte invasion. Cell. Microbiol. 15:1341–1356. 10.1111/cmi.12118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sim BK, Chitnis CE, Wasniowska K, Hadley TJ, Miller LH. 1994. Receptor and ligand domains for invasion of erythrocytes by Plasmodium falciparum. Science 264:1941–1944. 10.1126/science.8009226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pandey KC, Singh S, Pattnaik P, Pillai CR, Pillai U, Lynn A, Jain SK, Chitnis CE. 2002. Bacterially expressed and refolded receptor binding domain of Plasmodium falciparum EBA-175 elicits invasion inhibitory antibodies. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 123:23–33. 10.1016/S0166-6851(02)00122-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jiang L, Gaur D, Mu J, Zhou H, Long CA, Miller LH. 2011. Evidence for EBA-175 as a component of a ligand blocking blood stage malaria vaccine. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 108:7553–7558. 10.1073/pnas.1104050108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wickramarachchi T, Devi YS, Mohmmed A, Chauhan VS. 2008. Identification and characterization of a novel Plasmodium falciparum merozoite apical protein involved in erythrocyte binding and invasion. PLoS One 3:e1732. 10.1371/journal.pone.0001732 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gaur D, Storry JR, Reid ME, Barnwell JW, Miller LH. 2003. Plasmodium falciparum is able to invade erythrocytes through a trypsin-resistant pathway independent of glycophorin B. Infect. Immun. 71:6742–6746. 10.1128/IAI.71.12.6742-6746.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Williams AR, Douglas AD, Miura K, Illingworth JJ, Choudhary P, Murungi LM, Furze JM, Diouf A, Miotto O, Crosnier C, Wright GJ, Kwiatkowski DP, Fairhurst RM, Long CA, Draper SJ. 2012. Enhancing blockade of Plasmodium falciparum erythrocyte invasion: assessing combinations of antibodies against PfRH5 and other merozoite antigens. PLoS Pathog. 8(11):e1002991. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Crompton PD, Miura K, Traore B, Kayentao K, Ongoiba A, Weiss G, Doumbo S, Doumtabe D, Kone Y, Huang CY, Doumbo OK, Miller LH, Long CA, Pierce SK. 2010. In vitro growth-inhibitory activity and malaria risk in a cohort study in Mali. Infect. Immun. 78:737–745. 10.1128/IAI.00960-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rono J, Färnert A, Olsson D, Osier F, Rooth I, Persson KE. 2012. Plasmodium falciparum line-dependent association of in vitro growth-inhibitory activity and risk of malaria. Infect. Immun. 80:1900–1908. 10.1128/IAI.06190-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kennedy MC, Wang J, Zhang Y, Miles AP, Chitsaz F, Saul A, Long CA, Miller LH, Stowers AW. 2002. In vitro studies with recombinant Plasmodium falciparum apical membrane antigen 1 (AMA1): production and activity of an AMA1 vaccine and generation of a multiallelic response. Infect. Immun. 70:6948–6960. 10.1128/IAI.70.12.6948-6960.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Duan J, Mu J, Thera MA, Joy D, Kosakovsky Pond SL, Diemert D, Long C, Zhou H, Miura K, Ouattara A, Dolo A, Doumbo O, Su XZ, Miller L. 2008. Population structure of the genes encoding the polymorphic Plasmodium falciparum apical membrane antigen 1: implications for vaccine design. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105:7857–7862. 10.1073/pnas.0802328105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Srinivasan P, Beatty WL, Diouf A, Herrera R, Ambroggio X, Moch JK, Tyler JS, Narum DL, Pierce SK, Boothroyd JC, Haynes JD, Miller LH. 2011. Binding of Plasmodium merozoite proteins RON2 and AMA1 triggers commitment to invasion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 108:13275–13280. 10.1073/pnas.1110303108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lamarque M, Besteiro S, Papoin J, Roques M, Vulliez-Le Normand B, Morlon-Guyot J, Dubremetz JF, Fauquenoy S, Tomavo S, Faber BW, Kocken CH, Thomas AW, Boulanger MJ, Bentley GA, Lebrun M. 2011. The RON2-AMA1 interaction is a critical step in moving junction-dependent invasion by apicomplexan parasites. PLoS Pathog. 7(2):e1001276. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Healer J, Murphy V, Hodder AN, Masciantonio R, Gemmill AW, Anders RF, Cowman AF, Batchelor A. 2004. Allelic polymorphisms in apical membrane antigen-1 are responsible for evasion of antibody-mediated inhibition in Plasmodium falciparum. Mol. Microbiol. 52:159–168. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2003.03974.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dutta S, Lee SY, Batchelor AH, Lanar DE. 2007. Structural basis of antigenic escape of a malaria vaccine candidate. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104:12488–12493. 10.1073/pnas.0701464104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ouattara A, Takala-Harrison S, Thera MA, Coulibaly D, Niangaly A, Saye R, Tolo Y, Dutta S, Heppner DG, Soisson L, Diggs CL, Vekemans J, Cohen J, Blackwelder WC, Dube T, Laurens MB, Doumbo OK, Plowe CV. 2013. Molecular basis of allele-specific efficacy of a blood-stage malaria vaccine: vaccine development implications. J. Infect. Dis. 207:511–519. 10.1093/infdis/jis709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Miura K, Herrera R, Diouf A, Zhou H, Mu J, Hu Z, MacDonald NJ, Reiter K, Nguyen V, Shimp RL, Jr, Singh K, Narum DL, Long CA, Miller LH. 2013. Overcoming allelic specificity by immunization with five allelic forms of Plasmodium falciparum apical membrane antigen 1. Infect. Immun. 81:1491–1501. 10.1128/IAI.01414-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Duncan CJ, Hill AV, Ellis RD. 2012. Can growth inhibition assays (GIA) predict blood-stage malaria vaccine efficacy? Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 8:706–714. 10.4161/hv.19712 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Regules JA, Cummings JF, Ockenhouse CF. 2011. The RTS,S vaccine candidate for malaria. Expert Rev. Vaccines 10:589–599. 10.1586/erv.11.57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.White NJ. 2011. A vaccine for malaria. N. Engl. J. Med. 365:1926–1927. 10.1056/NEJMe1111777 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Daily JP. 2012. Malaria vaccine trials—beyond efficacy end points. N. Engl. J. Med. 367:2349–2351. 10.1056/NEJMe1213392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stoop JW, Zegers BJ, Sander PC, Ballieux RE. 1969. Serum immunoglobulin levels in healthy children and adults. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 4:101–112 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lopaticki S, Maier AG, Thompson J, Wilson DW, Tham WH, Triglia T, Gout A, Speed TP, Beeson JG, Healer J, Cowman AF. 2011. Reticulocyte and erythrocyte binding-like proteins function cooperatively in invasion of human erythrocytes by malaria parasites. Infect. Immun. 79:1107–1117. 10.1128/IAI.01021-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.