Abstract

Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Candida albicans are two pathogens frequently encountered in the intensive care unit microbial community. We have demonstrated that C. albicans airway exposure protected against P. aeruginosa-induced lung injury. The goal of the present study was to characterize the cellular and molecular mechanisms associated with C. albicans-induced protection. Airway exposure by C. albicans led to the recruitment and activation of natural killer cells, innate lymphoid cells (ILCs), macrophages, and dendritic cells. This recruitment was associated with the secretion of interleukin-22 (IL-22), whose neutralization abolished C. albicans-induced protection. We identified, by flow cytometry, ILCs as the only cellular source of IL-22. Depletion of ILCs by anti-CD90.2 antibodies was associated with a decreased IL-22 secretion and impaired survival after P. aeruginosa challenge. Our results demonstrate that the production of IL-22, mainly by ILCs, is a major and inducible step in protection against P. aeruginosa-induced lung injury. This cytokine may represent a clinical target in Pseudomonas aeruginosa-induced lung injury.

INTRODUCTION

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a Gram-negative bacterium frequently encountered in ventilator-associated pneumonia. Pseudomonas has a large number of virulence factors, some of which are already targeted as potential therapeutic alternatives (1, 2). Another interesting approach could be to identify a specific host response pattern that could similarly lead to therapeutic immunomodulation. This new approach is largely prompted by the evolution of the resistance profile toward increasing multiresistance, extreme resistance, or panresistance to conventional antibiotics (3).

Microbial communities associated with pneumonia and cystic fibrosis (CF) are more complex than once expected. These communities are frequently polymicrobial, including microorganisms originating from diverse ecological sources (4). Namely, microbial interactions have recently been demonstrated between typical pneumonia pathogens, such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Candida albicans, an endosaprophyte frequently isolated from tracheobronchial samples of CF and intensive care unit (ICU) patients. Indeed, several studies have reported the presence of C. albicans in tracheal aspirate (5), and the interactions between C. albicans and P. aeruginosa have various clinical impacts according to the status of the patient (6).

The major pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) of C. albicans recognized by the immune system are mannoproteins, glucans, and chitins (7–9). These patterns stimulate many different pathways through interactions with the mannose receptor, dectin-1, dectin-2 (7, 10), and galectin-3 (11). C. albicans mannan and (1→3)β-d-glucan PAMPs are responsible for the induction of a Th17 response (12). The Th17 response has been reported to be crucial for a C. albicans-induced host response. The interleukin-17 (IL-17) family of cytokines contains six sequence-related homologs: IL-17A through IL-17F (13). IL-17A and IL-17F, as well as the frequently associated cytokine IL-22, are major cytokines involved in the clearance of various pathogens (14). IL-17A has been recognized as a key mediator in host defense against C. albicans. In the context of C. albicans systemic infection, IL-17A receptor knockout mice exhibited dose-dependent reduced survival (15). Among the potential underlying mechanisms, IL-17-related cytokines have been shown to induce the recruitment of neutrophils (16) and the production of β-defensins by epithelial cells (17), which participate in the clearance of microbial pathogens. The cell source for IL-17 and IL-22 during infection by C. albicans has not been clearly identified. Recently, innate lymphoid cells (ILCs; including natural killer [NK] and ILC3 cells), as well as natural killer T (NKT) and Th cells, have been identified as an important source of these cytokines during infection in the gut and/or in the lung (18–20), although their role in the control of infection by P. aeruginosa has not yet been investigated.

We have previously shown that exposure with C. albicans could reduce P. aeruginosa-induced lung injury, as evaluated by lung lesion and bacterial burden (21). The goal of the present study was to characterize the cellular and molecular mechanisms of C. albicans-induced protection in P. aeruginosa lung injury. Our data show that C. albicans exposure reduces P. aeruginosa-induced lung injury by triggering the IL-17 pathway in innate lymphoid cells and stimulating the production of antimicrobial peptides.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals and products.

All chemicals and reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) unless specified otherwise. Plastics were purchased from Sarstedt (Numbrecht, Germany) unless specified otherwise.

Bacterial and fungal strains.

The P. aeruginosa PAO1 strain was used (22). Bacteria were grown overnight at 37°C in Luria-Bertani broth, with orbital shaking (400 rpm), harvested by centrifugation (2,000 × g, 5 min), and washed twice with sterile isotonic saline (SIS). Bacterial suspensions and inoculum standardization were then determined based on the optical density at 600 nm (Ultrospec 10 Cell Density Meter; General Electric, CT) and verified by serial dilution and plating on bromcresol purple agar (BCP; bioMérieux, Marcy l'Étoile, France).

Candida albicans SC5314 was used as a reference strain (23). The Saccharomyces cerevisiae S288C reference strain was kindly provided by Cécile Fairhead (Institut de Génétique et Microbiologie, UMR 8621, Université Paris Sud). The Schizosaccharomyces pombe SP972 reference strain was kindly provided by Pascal Bernard (Architecture et Dynamique Fonctionnelle des Chromosomes, UMR5239 CNRS/ENS-Lyon).

All strains were conserved long term in 40% glycerol medium. Yeasts were grown overnight on yeast-peptone-dextrose agar plus 0.015% amikacin (YPD) at 37°C. They were then harvested and washed twice with SIS. The yeast inoculum was determined by counting on a Mallassez hematocytometer and verified by serial dilution and plating on YPD agar.

Mouse model.

Six-week-old C57BL/6 mice were purchased from Janvier Laboratories (Le Genest Saint-Isle, Mayenne, France) and housed in the pathogen-free Lille 2 University animal care facility. Water and food were available ad libitum. All experiments had been approved by the Nord-Pas de Calais ethics committee for animal experiments. In compliance with French animal care and use in investigational research guidelines, mice were sacrificed by lethal intraperitoneal injection of 0.3 ml of 5.47% pentobarbital (Laboratoire CEVA, Libourne, France).

Pneumonia.

Mice were anesthetized briefly with inhaled sevoflurane (Sevorane; Abbott, Queensborough, United Kingdom), allowing maintenance of spontaneous breathing. Instillation was performed intranasally in spontaneously breathing anesthetized mice with 50 μl of the calibrated solution.

Lung injury.

Alveolocapillary membrane permeability was evaluated by measuring fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-labeled-albumin leakage from the vascular compartment to the alveolar-interstitial compartment, as previously described (24). Briefly, mice were sacrificed after FITC-albumin injection, blood was collected, and lungs were homogenized in 0.9% saline. The fluorescence ratio measured in serum and lung homogenate (excitation, 487 nm; emission, 520 nm; Mithras LB 940; Berthold Technologies, Bad Wildbad, Germany) reflects alveolocapillary permeability. Extravascular lung water was assessed by measuring the weight of the lung homogenate, both immediately and after 3 days of desiccation at 70°C.

Bacterial and fungal loads and translocation were evaluated by plating, after serial dilutions, in lung homogenate or blood on either BCP or YPD agar, respectively, overnight at 37°C. CFU were enumerated and indexed to the lung weight (whenever necessary, P. aeruginosa was identified by an oxidase test).

Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL).

After mouse euthanasia, the trachea was cannulated with a 20-gauge modified gavage needle. Lavage was performed by injection and aspiration 4 times with 0.5 ml of ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The supernatant was harvested by centrifugation and frozen at −80°C. The cells were enumerated and characterized after concentration on a slide with a cytospin (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA).

Drugs and administration schedules.

When necessary, mice were rendered neutropenic by three intraperitoneal injections of 75 mg of cyclophosphamide/kg in a 5% glucose solution 6, 4, and 2 days prior to P. aeruginosa pneumonia induction, as previously described (25). Anti-IL-22 antibodies were purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN), and 50 μg was intratracheally administered immediately before C. albicans or SIS instillation, as described by Aujla et al. (26). Anti-CD90.2 antibodies were purchased from BioXCell (West Lebanon, NH) and administered intraperitoneally every 3 days at a dose of 250 μg/mouse, starting 6 days before P. aeruginosa instillation, as described by Sonnenberg et al. (27). Anti-IL-17A polyclonal antibodies were kindly provided by Catherine Uyttenhove (Université Catholique de Louvain, Louvain, Belgium) and were administered intraperitoneally at a dose of 50 μg twice a day on day 0. Recombinant mouse IL-22 was purchased from R&D Systems. Mice were anesthetized briefly with inhaled sevoflurane, allowing maintenance of spontaneous breathing. Instillation was performed intranasally in spontaneously breathing anesthetized mice with 0.7 μg of IL-22 in 50 μl of SIS.

qPCR.

RNA extraction was performed using a GeneJET RNA purification kit (Fermentas, Glen Burnie, MD). RNA was retrotranscribed using an AffinityScript multiple-temperature cDNA synthesis kit (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). Quantitative PCR (qPCR) was performed using Agilent Brilliant II SYBR green qPCR master mix on Stratagene MX 3005p (Agilent Technologies). Cycle threshold (CT) was recorded. After amplification, a DNA melting-temperature curve was analyzed to verify the presence of a single amplicon. A β-actin gene was used as an internal reference for gene transcription normalization. Relative mRNA levels were determined according to the following formula: CT of actin was retrieved from the CT of the corresponding gene of interest (ΔCT = the gene-of-interest CT − the β-actin CT). The mean ΔCT for control groups (mΔCT) was then determined for each gene of interest. The relative mRNA expression, normalized on β-actin, and control basal expression were calculated as follows: ΔΔCT = 2gene-of-interest ΔCT − gene-of-interest mΔCT comparing the gene-of-interest PCR cycle threshold values (CT) for the gene of interest and β-actin (ΔCT) and the ΔCT values for the treated and control groups (ΔΔCT).

Hematopoietic lineage lung cell isolation and primary culture.

After euthanasia, mice were exsanguinated and perfused with 10 ml of ice-cold isotonic saline before their lungs were harvested. Lungs were minced using a razor blade and incubated for 30 min at 37°C in 1% collagenase. Digested tissues were then homogenized by repeatedly passing through a 20-gauge needle and filtered through a 100-μm-pore-size cell strainer (BD, Franklin Lakes, NJ). Cells with a hematopoietic lineage were separated from epithelial cells by a 20% Percoll gradient (1,500 × g, 10 min), and the remaining red blood cells were lysed by a 10-min incubation in a red blood cell lysis buffer (155.17 mM NH4Cl, 10 mM KHCO3, 308 μM EDTA). The cells were finally suspended in PBS and enumerated. Cells isolated from mouse lungs were resuspended in antibiotic-supplied complete Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM; Invitrogen/Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) at a concentration of 3 × 106/ml in 96-well culture plates (100 μl/well). Cells were stimulated during 24 h by either live or ethanol-killed C. albicans or P. aeruginosa (multiplicity of infection [MOI] = 1). Supernatants were harvested and frozen for secondary cytokine measurement. Cytokine levels were determined in the BAL fluid or culture supernatants by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), according to the manufacturer's instructions (R&D Systems).

Flow cytometry.

Antibodies and the permeation kit were purchased from BD. Cells harvested from BAL fluid and lungs were washed and incubated with appropriate dilutions of an antigen-presenting-cell antibody panel (FITC-conjugated anti-IAb, phycoerythrin [PE]-conjugated anti-F4/80, PerCP/Cy5-conjugated anti-CD103, PE/Cy7-conjugated anti-CD11c, allophycocyanin [APC]-conjugated anti-CCR2, Alexa 700-conjugated anti-CD86, APCH7-conjugated anti-LY6G, V450-conjugated anti-CD11b, V500-conjugated anti-CD45, ef605-conjugated anti-Ly6C) or a lymphoid-cell antibody panel (FITC-conjugated anti-CD5, PE-conjugated anti-CD1.d tetramer, PerCP/Cy5-conjugated anti-NK1.1, APC-conjugated anti-CD25, Alexa 700-conjugated anti-CD69, APCH7-conjugated anti-CD4, V450-conjugated anti-TCRb, V500-conjugated anti-CD8, and eF605-conjugated CD45) for 30 min in PBS and then washed twice and resuspended in PBS 2% fetal calf serum. For intracellular staining, cells harvested from lungs were washed and incubated during 4 h with 3 μg of brefeldin A (eBioscience, San Diego, CA)/ml, washed with PBS, and incubated with appropriate dilutions of an innate-lymphoid-cell antibody panel (FITC-conjugated anti-Lin [cd3, cd11b ly6c ly6g ly76 cd45/220], PerCP/Cy5-conjugated anti-NK1.1, PE/Cy7-conjugated anti-CD127, Alexa 700-conjugated anti-CD90.2, APC/H7-conjugated anti-CD4, ef605-conjugated anti-CD45) or lymphoid-cell antibody panel (PerCP/Cy5-conjugated anti-NK1.1, APC H7-conjugated anti-CD4, V450-conjugated anti-TCRb, V500-conjugated anti-CD8, ef605-conjugated anti-CD45) for 30 min in PBS. The cells were washed twice. Fixation and permeabilization for cytokine intracellular staining were performed according to the manufacturer's instruction. PE-conjugated anti-IL-22 and APC-conjugated anti-IL-17 were used (eBioscience). For each antibody, a control isotype was used for compensation. Cells were analyzed on an LSR Fortessa (BD Biosciences). Generated data were analyzed using FlowJo 8.7 (Tree Star, Stanford, CA).

Statistical analysis.

Quantitative variables were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), with a Mann-Whitney U post hoc test when appropriate. Survival was analyzed with a log-rank test. Statistics and graphs were performed using Prism 6 software (GraphPad, Inc., La Jolla, CA). Qualitative variables were analyzed with a χ2 test. A P value of <0.05 was considered significant. The results are expressed as means ± the standard error.

RESULTS

C. albicans airway exposure primes the innate immune response.

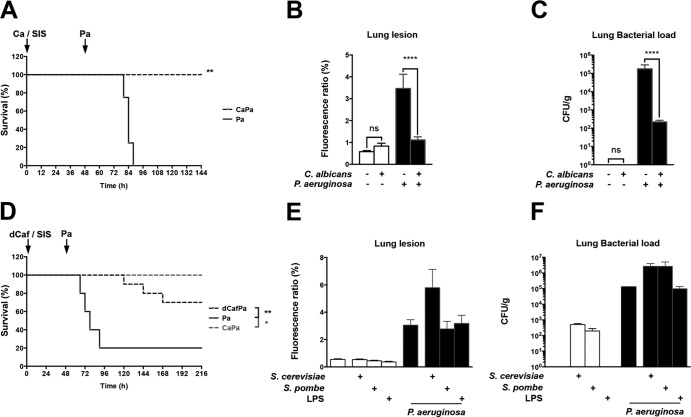

We exposed male C57BL/6 mice through intranasal instillation to 105 CFU of C. albicans SC5314 strain. Control mice were instilled with sterile isotonic saline (SIS). Using a subsequent lethal inoculum of P. aeruginosa PAO1 strain (5 × 107 CFU/mouse), 48 h after C. albicans exposure, we observed improved survival for C57BL/6 mice previously exposed to C. albicans (Fig. 1A). To study lung injury, a nonlethal P. aeruginosa inoculum (107 CFU) was used. Mice were sacrificed at 48 h after P. aeruginosa instillation. Lung injury was assessed based on the leakage of FITC-labeled serum albumin into the lungs, and the lung bacterial load was measured. As previously described (21), prior C. albicans exposure reduced Pseudomonas-induced lung injury, as well as the lung bacterial load (Fig. 1B and C). To assess whether this protection against P. aeruginosa lung injury was exclusively related to living C. albicans, control experiments were performed using mice exposed to Saccharomyces cerevisiae, to Schizosaccharomyces pombe, or to the instillation of either lipopolysaccharide (LPS) or heat-killed C. albicans. Whereas both fungi and LPS did not reduce lung injury and bacterial load associated with P. aeruginosa infection, heat-killed C. albicans significantly protected mice, but only with a charge equal to 100 times that of live C. albicans cells (Fig. 1D, E, and F).

FIG 1.

C. albicans airway exposure reduces P. aeruginosa-induced lung injury and mortality. C57BL/6 mice were intranasally instilled with either SIS or 105 CFU of strain SC5314. Forty-eight hours later, mice of each group were instilled with a lethal inoculum of P. aeruginosa. (A) Survival of P. aeruginosa-infected mice was assessed in SIS (Pa)- or C. albicans (CaPa)-treated mice. (B) Lung lesions were assessed 24 h after the instillation of SIS, C. albicans, or P. aeruginosa by measuring the leakage of FITC-labeled bovine serum albumin from the serum to the lung. (C) The lung bacterial load was assessed 24 h after the instillation of SIS, C. albicans, or P. aeruginosa after homogenization of the lungs in SIS and plating after serial dilutions. (D) Survival of P. aeruginosa-infected mice was assessed in SIS (Pa)-, C. albicans (CaPa)-, or ethanol-killed C. albicans (dCafPa)-treated mice. (E) Lung lesions were assessed 48 h after the instillation of SIS, S. cerevisiae, Schizosaccharomyces pombe, or LPS and 24 h after P. aeruginosa instillation in mice treated with SIS, S. cerevisiae, Schizosaccharomyces pombe, or LPS by measuring the leakage of FITC-labeled bovine serum albumin from the serum to the lung. (F) Lung bacterial loads 48 h after the instillation of SIS, S. cerevisiae, Schizosaccharomyces pombe, or LPS and 24 h after P. aeruginosa instillation in mice treated with SIS, S. cerevisiae, Schizosaccharomyces pombe, or LPS and after homogenization of the lungs in SIS and plating after serial dilutions. Each graph is representative of three independent experiments. n = 5 in each group of every experiment. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001.

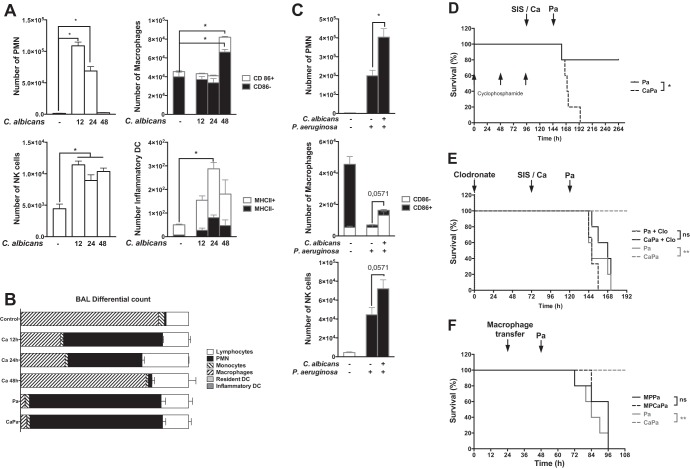

C. albicans-induced leukocyte cell recruitment was assessed in BAL fluid. Samples were drawn at 12, 24, and 48 h after exposure to C. albicans. The phenotype and the level of activation of inflammatory cells were assessed by flow cytometry. Polymorphonuclear neutrophils (PMNs) significantly increased at 12 h and then decreased to control values at 24 and 48 h (Fig. 2A). The number of natural killer (NK) cells also significantly increased at 12 h and remained stable at 24 and 48 h (Fig. 2A). Alveolar inflammatory dendritic cells and macrophages were significantly recruited and activated (as shown by the expression of major histocompatibility complex [MHC] class II and the costimulatory molecule CD86) at 24 and 48 h, respectively, in mice exposed to C. albicans (Fig. 2A).

FIG 2.

C. albicans airway exposure primes the innate immune response. (A) C. albicans-induced leukocyte cell recruitment was assessed in BAL samples drawn 12, 24, and 48 h after exposure to C. albicans. The cell phenotype was assessed by flow cytometry, and the levels of immune activation were determined based on the expression of coactivation molecules (CD86 and MHC II for macrophages and dendritic cells). (B) Leukocyte cell recruitment was assessed in BAL samples drawn from control mice or, 12 h postinfection with P. aeruginosa, in previously SIS-treated or C. albicans-exposed mice. The cell phenotype was assessed by flow cytometry, and the levels of immune activation were determined through the expression of coactivation molecules (CD86 and MHC II for macrophages). (C) The differential cell count was assessed in BAL samples drawn from SIS-treated mice and 12, 24, and 48 h after C. albicans exposure or 12 h after P. aeruginosa infection in SIS-treated or C. albicans-exposed mice. (D) Cyclophosphamide-induced neutropenia prior to C. albicans airway exposure was not associated with increased mortality in P. aeruginosa-infected C. albicans-exposed mice when the inoculum was lowered by 2 log (105 CFU). (E) Alveolar macrophage depletion prior to C. albicans airway exposure was associated with increased mortality in P. aeruginosa-infected C. albicans-exposed mice. (F) Instillation of C. albicans-activated macrophages (MP) was not associated with restoration of the protective effect. Each graph is representative of three independent experiments. n = 5 for each group of every experiment, except for panel E (where n = 6). *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001; ns, not significant.

Subsequent instillation of P. aeruginosa induced a recruitment of PMNs at 12 h postinfection in the BAL fluid and then decreased (Fig. 2C). Forty-eight hours postinfection, the percentages of each subpopulation count for the saline-treated controls and mice exposed to C. albicans remained comparable at this time point (Fig. 2B). Interestingly, the absolute number of macrophages and NK cells recruited 12 h after infection was significantly higher in Candida-exposed mice than in mice instilled with PAO1 alone (Fig. 2C). In the literature, depletion of macrophages by liposomal clodronate or of PMN by cyclophosphamide is associated with more severe infection (25, 28). However, PMN or macrophage recruitment alone was not sufficient to explain the difference in responses observed compared to mice exposed to C. albicans. Mice depleted of either PMNs or macrophages and infected with a lower inoculum of P. aeruginosa still had a better response than SIS-treated animals (Fig. 2D and E, respectively). Furthermore, macrophages and NK cells from mice receiving C. albicans were not sufficient to reproduce the protection in control mice (Fig. 2F and data not shown).

C. albicans exposure induces local secretion of IL-22.

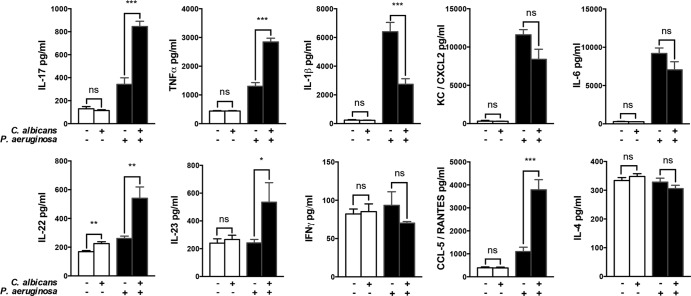

To assess the response induced by C. albicans lung exposure, we measured Th1 (gamma interferon [IFN-γ] and tumor necrosis factor alpha [TNF-α]), Th2 (IL-4), and Th17-like (IL-17, IL-22, and IL-23) cytokines, proinflammatory cytokines (IL-1β and IL-6), and chemokines (CCL-5/RANTES and CXCL2/KC) secreted in the BAL fluid 24 h after exposure of the airway to C. albicans. Among the various cytokines and chemokines, only the level of IL-22 was significantly increased after exposure to C. albicans in the BAL fluid (Fig. 3).

FIG 3.

C. albicans lung exposure induces local secretion of IL-22 and potentiates the cytokine burst in response to P. aeruginosa. BAL fluid samples were retrieved 24 h after SIS or C. albicans treatment and 12 h after P. aeruginosa infection from either SIS-treated or C. albicans-exposed mice. Th1 (IFN-γ and TNF-α), Th2 (IL-4), and Th17-like (IL-17, IL-22, and IL-23) cytokines, proinflammatory cytokines (IL-1β and IL-6), and chemokines (CCL-5/RANTES and CXCL2/KC) secreted in the BAL fluid were measured by ELISA. Each graph is representative of three independent experiments. n = 5 in each group of every experiment. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001.

C. albicans exposure potentiates the cytokine burst in response to P. aeruginosa.

P. aeruginosa alone was responsible for increased production of Th17-like cytokines (IL-17 and IL-22) and proinflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6), as well as chemokines (CXCL2 and CCL-5), a finding consistent with previous reports (29). Mice exposed to C. albicans prior to P. aeruginosa instillation had significantly more IL-17, IL-22, IL-23, TNF-α, and CCL-5 in their BAL fluid than did saline-treated controls infected with P. aeruginosa. Surprisingly, IL-1β was significantly decreased in the exposed group (Fig. 3), whereas CXCL2 and IL-6 were not affected.

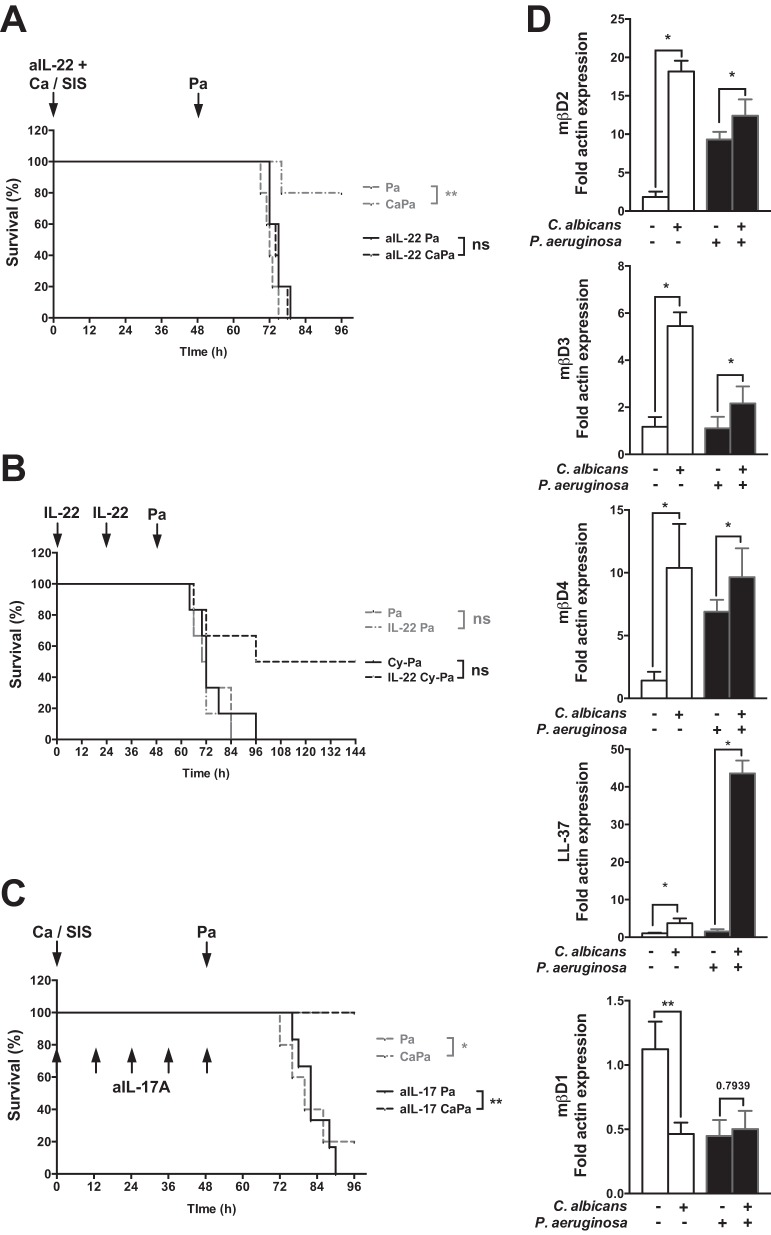

IL-22 primes a protective neutrophil-independent response.

IL-17 and IL-22 have been recently identified as a key factors in mucosal innate immunity, notably to maintain epithelial integrity and induce antimicrobial peptide production (26). Given that exposure with C. albicans primed IL-22 production, we hypothesized that IL-22 was a key mediator involved in the protection against lung injury. Intranasal instillation with neutralizing anti-IL-22 antibodies prior to C. albicans airway exposure was associated with increased mortality in P. aeruginosa-infected C. albicans-exposed mice (Fig. 4A). However, we failed to reproduce the protective effect of C. albicans using intranasal recombinant mouse IL-22 instillation (50 μg, 48 and 24 h before the infection) in mice subsequently infected by P. aeruginosa (Fig. 4B). C. albicans-induced protection remained unchanged after an anti-IL-17A antibody administration (Fig. 4C).

FIG 4.

IL-22 primes a protective neutrophil-independent response. (A) Intranasal instillation with neutralizing anti-IL-22 antibodies (aIL-22) prior to C. albicans airway exposure was associated with increased mortality in P. aeruginosa-infected, C. albicans-exposed mice. (B) Mice were rendered neutropenic by three intraperitoneal injections of 75 mg of cyclophosphamide (Cy)/kg in a 5% glucose solution at 6, 4, and 2 days prior to P. aeruginosa pneumonia induction. Intranasal instillation of recombinant mouse IL-22 (IL-22), 24 and 48 h before a sublethal P. aeruginosa instillation (105 CFU/mice), increased survival in neutropenic mice. (C) Intraperitoneal injection of 50 μg of purified murine anti-IL-17 antibodies, 2 h before C. albicans challenge and every 12 h until P. aeruginosa infection, was not associated with increased mortality in P. aeruginosa-infected C. albicans-exposed mice. (D) The expression of β-defensin (mβD)-1, -2, -3, and -4 and cathelicidin (LL-37) was assessed by reverse transcription (RT)-qPCR in RNA extracted from the lungs retrieved from SIS-treated mice 48 h after C. albicans exposure and 12 h after P. aeruginosa pneumonia induction after either SIS treatment or C. albicans exposure. The level of expression is relative to the expression of β-actin. Each graph is representative of three independent experiments. n = 5 in each group of every experiment, except for panel A and for aIL-17Pa in panel C (where n = 6). *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001.

Interestingly, intranasal instillation of recombinant mouse IL-22 increased survival in neutropenic mice receiving a sublethal P. aeruginosa inoculum (Fig. 4B). Thus, a neutrophil-independent response assessed in cyclophosphamide-treated mice can be promoted by supplementation with IL-22.

C. albicans-primed protection against P. aeruginosa lung injury involves IL-22-mediated production of antimicrobial peptides.

IL-22 is known to induce antimicrobial peptide production (30). We measured the expression of four inducible peptides shown to be important against Gram-negative pneumonia (β-defensin-2, -3, and -4 and cathelicidin [LL-37]) (31) and one noninducible antimicrobial peptide (β-defensin-1). The levels of inducible β-defensin-2, -3, and -4, as well as cathelicidin, increased after C. albicans exposure (Fig. 4D). P. aeruginosa infection only increased the expression of β-defensin-2 and -4, whereas prior exposure to C. albicans further increased the expression of β-defensin-2, -3, and -4, with a synergistic effect on cathelicidin.

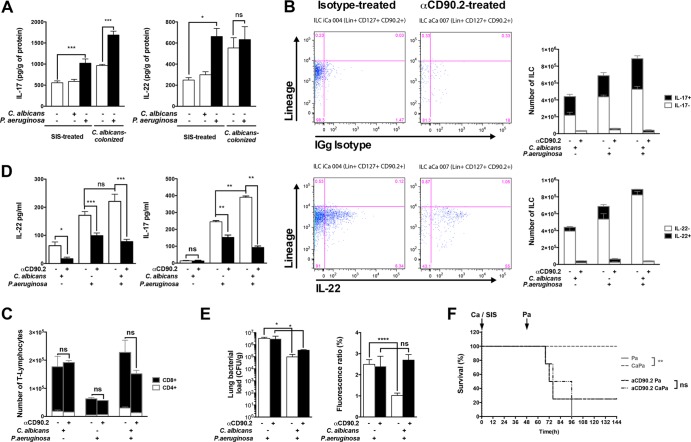

IL-22 and IL-17 are secreted by innate lymphoid cells.

The cellular sources of IL-22 and IL-17 in the lung have been described to be NK cells, NKT cells, and ILCs (30, 32). Immune cells isolated from the lungs of C. albicans-exposed mice produced higher levels of IL-22 and IL-17 than did cells isolated from the lungs of control mice at baseline (Fig. 5A). Surprisingly, immune cells isolated from the lungs of control mice were not able to produce IL-17 and IL-22 after ex vivo stimulation with C. albicans, whereas both cytokines were upregulated after infection with P. aeruginosa (Fig. 5A). Compared to control mice, the immune cells isolated from the lungs of Candida-exposed mice ex vivo secreted increased levels of IL-22 without further activation, whereas stimulation by P. aeruginosa only increased IL-17 secretion. These results indicate that IL-22 is probably produced by cells recruited in the lungs in response to C. albicans.

FIG 5.

IL-22 and IL-17 are secreted by innate lymphoid cells. (A) IL-22 is produced by cells recruited in the lungs in response to C. albicans exposure. Hematopoietic lineage lung cells were isolated after lung mechanic and enzymatic (collagenase) dissociation and separated from epithelial cells by a 20% Percoll gradient. The remaining red blood cells were lysed, and the total immune cells isolated were suspended in DMEM at a concentration of 3 × 106/ml. Cells isolated from SIS-treated or C. albicans-treated mice were stimulated either for 24 h by C. albicans or for 3 h by P. aeruginosa (MOI = 1). The cytokine levels were determined in BAL fluid or culture supernatants by ELISA. (B) IL-22 and IL-17 production was analyzed among these cell populations by flow cytometry. Intracellular labeling of lung cells with anti-IL-17 and anti-IL-22 antibodies was measured 24 h after C. albicans exposure in ILCs (Lin− CD127+ CD90.2+ CD25+). To further support the role of ILC in the protection, depletion was obtained by administration of anti-CD90.2 antibodies every 3 days, 6 days prior to C. albicans exposure or P. aeruginosa pneumonia. (C) T lymphocyte recruitment was assessed as a control in the same groups. (D) BAL fluid was retrieved in isotype- or anti-CD90.2 (αCD90.2)-treated mice at 24 h after SIS treatment or C. albicans exposure and 12 h after P. aeruginosa infection in SIS-treated and C. albicans-exposed mice. IL-17 and IL-22 secreted in the BAL fluid were then measured by ELISA. (E) Lung lesions and lung bacterial loads were assessed in isotype- or αCD90.2-treated mice at 24 h after SIS treatment or C. albicans exposure and at 12 h after P. aeruginosa infection in SIS-treated and C. albicans-exposed mice. (F) Survival was assessed in isotype- or αCD90.2-treated mice after P. aeruginosa infection in either SIS-treated or C. albicans-exposed mice. Each graph is representative of three independent experiments. n = 4 in each group of every experiment. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001.

IL-22 and IL-17 production was analyzed among these cell populations by flow cytometry. Intracellular labeling of lung cells with anti-IL-17 and anti-IL-22 antibodies was measured at 24 h after C. albicans exposure. ILCs (Lin− CD127+ CD90.2+ CD25+) were massively recruited to the lungs after C. albicans exposure, representing the vast majority (ca. 98%) of cells positive for IL-17 and IL-22 production (Fig. 5B). In contrast, no increase in the percentages of cells positive for these cytokines was detected in NK, NKT, and Th cells in exposed mice.

ILCs are essential to mediate C. albicans-induced protection.

To further support the role of ILC in the protection, depletion was obtained by the administration of anti-CD90.2 antibodies every 3 days, starting 6 days prior to C. albicans colonization or P. aeruginosa pneumonia (27). Anti-CD90.2-treated mice exhibited markedly decreased ILC recruitment and also a trend toward a decreased T lymphocyte count (Fig. 5C). The production of both IL-22 and IL-17 was also dramatically decreased both after C. albicans exposure and during P. aeruginosa pneumonia (Fig. 5D). This ILC depletion was associated with a loss of protection in mice exposed to C. albicans. Mortality and bacterial load for this group were significantly higher than in the control group, a result associated with increased PMN recruitment in anti-CD90.2-treated control mice (Fig. 5E and F). However, anti-CD90.2-treated mice previously exposed to C. albicans remained less susceptible to P. aeruginosa pneumonia than did anti-CD90.2-treated control mice (Fig. 5E).

DISCUSSION

P. aeruginosa is an opportunistic pathogen with a large panel of virulence factors and a growing number of resistance mechanisms. Innovative approaches are now mandatory in order to face the challenge of increasing multiresistance. We have already shown that Candida exposure could protect against P. aeruginosa-induced lung injury in a murine model (21). The characterization of the mechanisms involved in this protection could provide potential alternative therapeutic strategies in managing Pseudomonas infection. Our results show that C. albicans primes the lung innate immune response, inducing IL-22 and IL-17 secretion by recruiting innate lymphoid cells. This is associated with both moderate PMN recruitment and strong expression of antimicrobial peptides that may explain the protective effect associated with C. albicans airway exposure.

Protective priming of the lung mucosal innate immunity by inactivated bacterial pathogens against bacterial and fungal pathogens has been previously described (19). Evans et al. treated mice with an aerosolized lysate of killed Haemophilus influenzae and subsequently challenged these mice with a lethal dose of live Streptococcus pneumoniae. Protection was also obtained using this bacterial lysate against Pseudomonas (33). In our study, we found a protective effect using C. albicans; interestingly, this protection could not be reproduced with other innocuous fungal species, such as Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Moreover, this priming is more efficient with live C. albicans, since protection was only obtained with a 100-fold-higher dose of killed C. albicans. Individual extracted Candida cell wall components or their associations, as well as LPS, failed to reduce mortality, which potentially reflects the complexity of the host-pathogen interactions underlying the protective effect. According to these data, the single activation of a pathogen recognition receptor(s) did not allow us to elicit this protective effect.

Several authors have already described the alveolar innate immune cell response to P. aeruginosa, underlining the major role of PMNs and NK cells in this infection (20, 25). In our work, we observed that airway exposure to C. albicans was associated with an important recruitment of PMNs and NK cells, as well as macrophages, in the BAL fluid. Infection with P. aeruginosa potentiates this recruitment and the activation of macrophages and dendritic cells. Nevertheless, depletion of effector cells such as alveolar macrophages (AM) and neutrophils during the exposure did not abolish the protection induced by C. albicans. Adoptive transfer of activated cells did not restore the protection against P. aeruginosa. Since the depletion of these cell types increased the sensitivity to P. aeruginosa, it is difficult to completely eliminate their involvement in the protective effect of C. albicans. In addition, the persistence of a C. albicans-induced effect in this context suggests that AM and neutrophils have an accessory role in this protection.

We observed strong recruitment of ILCs in the lungs after exposure. This recruitment and the activation of these cells might be related to the mobilization of dendritic cells in the lung compartment. Interestingly, depletion of this cell population with anti-CD90.2 antibody completely abolished the effect of live Candida cells. Although the depletion also affects some T lymphocytes, among innate lymphocytes, ILCs are mainly targeted by this treatment. This is the first report showing the recruitment of this type of ILC during C. albicans exposure of the lung.

The major function of ILCs is to promptly produce immunoregulatory cytokines in response to environmental stimuli. Interestingly, analysis of the cytokine levels in BAL fluid showed that Candida exposure only increased the level of IL-22, whereas the production of both IL-22 and IL-17 is upregulated in lung cells after infection with P. aeruginosa. These cytokines might be produced by a variety of cells, including activated T cells (Th17 cells), γδ T cells, and NK and NKT cells (34–37). Identification of the cells producing these cytokines in the lungs revealed that ILCs represented the majority of IL-17- and IL-22-positive cells after C. albicans exposure. In addition, we were not able to detect significant upregulation of the numbers of cytokine-positive cells in other cell populations.

Using anti-CD90.2 antibodies, the depletion of ILCs is associated with a strong decrease of the secretion of IL-17 and IL-22, confirming the key role of these cells in the secretion of these cytokines. The relative specificity of the depletion was confirmed by the fact that this treatment did not decrease the absolute number in each cell population, as well as the number of cytokine-positive cells. Protection against P. aeruginosa was abolished in C. albicans-pretreated mice that received anti-CD90.2 antibodies. To our knowledge, our study is the first to provide evidence of a link between the production of Th17 cytokines by ILCs and of its protective effect in bacterial pneumonia.

IL-17 directly activates epithelial cells, and it was recently shown that the early production of IL-17 could protect against Pseudomonas-induced lung injury (38). This can be mediated by the increased recruitment of neutrophils (29) linked to the synergistic action of IL-17 and TNF-α on CXCL5 production. However, in our model, the protection persists after treatment with neutralizing anti-IL-17 antibodies and in neutrophil-depleted mice, suggesting that this mechanism is not essential. Since IL-22 production was only detected after exposure to C. albicans, our data suggest that IL-22 and IL-17 act sequentially and in an additive or a synergistic manner and that IL-22 boosts the lung defense mechanisms.

De Luca et al. showed that IL-22 production was induced in the intestine by C. albicans (39); we observed similar results following lung exposure. IL-22 has recently been implicated in the preservation of epithelial integrity through its action on intercellular junctions and the synthesis of antimicrobial peptides (26, 30). Among antimicrobial peptides, β-defensin-2 and cathelicidin have been reported to play a pivotal role in the control of P. aeruginosa infection (40–42). Since both antimicrobial peptides were strongly potentiated by C. albicans exposure, this mechanism could therefore participate in the protection. Moreover, pretreatment with C. albicans allows us to limit the alteration of lung permeability, a process involving the restoration of epithelial integrity.

Our study demonstrates that C. albicans primes the recruitment of ILCs to the lungs as a major source of Th17 inflammatory cytokine production. These cytokines allow the recruitment of phagocytic cells to the lungs and the production of antimicrobial peptides potentially by the respiratory epithelium. Through these mechanisms, priming of the alveolar innate immune response by C. albicans exposure protects against P. aeruginosa in a murine model of infection. Strategies to promote the Th17 pathway in the innate immune system have already been explored against Streptococcus pneumoniae infection and could represent an interesting path in Pseudomonas infection.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 28 October 2013

REFERENCES

- 1.Baer M, Sawa T, Flynn P, Luehrsen K, Martinez D, Wiener-Kronish JP, Yarranton G, Bebbington C. 2009. An engineered human antibody Fab fragment specific for Pseudomonas aeruginosa PcrV antigen has potent antibacterial activity. Infect. Immun. 77:1083–1090. 10.1128/IAI.00815-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kipnis E, Sawa T, Wiener-Kronish J. 2006. Targeting mechanisms of Pseudomonas aeruginosa pathogenesis. Med. Mal. Infect. 36:78–91. 10.1016/j.medmal.2005.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Magiorakos AP, Srinivasan A, Carey RB, Carmeli Y, Falagas ME, Giske CG, Harbarth S, Hindler JF, Kahlmeter G, Olsson-Liljequist B, Paterson DL, Rice LB, Stelling J, Struelens MJ, Vatopoulos A, Weber JT, Monnet DL. 2012. Multidrug-resistant, extensively drug-resistant, and pandrug-resistant bacteria: an international expert proposal for interim standard definitions for acquired resistance. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 18:268–281. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03570.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hibbing ME, Fuqua C, Parsek MR, Peterson SB. 2010. Bacterial competition: surviving and thriving in the microbial jungle. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 8:15–25. 10.1038/nrmicro2259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Delisle M-S, Williamson DR, Perreault MM, Albert M, Jiang X, Heyland DK. 2008. The clinical significance of Candida colonization of respiratory tract secretions in critically ill patients. J. Crit. Care 23:11–17. 10.1016/j.jcrc.2008.01.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Méar JB, Kipnis E, Faure E, Dessein R, Schurtz G, Faure K, Guery B. 2013. Candida albicans and Pseudomonas aeruginosa interactions: more than an opportunistic criminal association? Med. Mal. Infect. 43:146–151. 10.1016/j.medmal.2013.02.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van der Meer JWM, van de Veerdonk FL, Joosten LAB, Kullberg BJ, Netea MG. 2010. Severe Candida spp. infections: new insights into natural immunity. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 36:S58–S62. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2010.11.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Poulain D, Jouault T. 2004. Candida albicans cell wall glycans, host receptors and responses: elements for a decisive crosstalk. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 7:342–349. 10.1016/j.mib.2004.06.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gow NAR, van de Veerdonk FL, Brown AJP, Netea MG. 2012. Candida albicans morphogenesis and host defense: discriminating invasion from colonization. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 10:112–122. 10.1038/nrmicro2711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cheng SC, van de Veerdonk FL, Lenardon M, Stoffels M, Plantinga T, Smeekens S, Rizzetto L, Mukaremera L, Preechasuth K, Cavalieri D, Kanneganti TD, van der Meer JWM, Kullberg BJ, Joosten LAB, Gow NAR, Netea MG. 2011. The dectin-1/inflammasome pathway is responsible for the induction of protective T-helper 17 responses that discriminate between yeasts and hyphae of Candida albicans. J. Leukoc. Biol. 90:357–366. 10.1189/jlb.1210702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jouault T, Abed-El Behi El M, Martínez-Esparza M, Breuilh L, Trinel P-A, Chamaillard M, Trottein F, Poulain D. 2006. Specific recognition of Candida albicans by macrophages requires galectin-3 to discriminate Saccharomyces cerevisiae and needs association with TLR2 for signaling. J. Immunol. 177:4679–4687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van de Veerdonk FL, Marijnissen RJ, Kullberg BJ, Koenen HJPM, Cheng S-C, Joosten I, van den Berg WB, Williams DL, van der Meer JWM, Joosten LAB, Netea MG. 2009. The macrophage mannose receptor induces IL-17 in response to Candida albicans. Cell Host Microbe 5:329–340. 10.1016/j.chom.2009.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gaffen SL. 2009. Structure and signaling in the IL-17 receptor family. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 9:556–567. 10.1038/nri2586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cypowyj S, Picard C, Maródi L, Casanova J-L, Puel A. 2012. Immunity to infection in IL-17-deficient mice and humans. Eur. J. Immunol. 42:2246–2254. 10.1002/eji.201242605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huang W, Na L, Fidel PL, Schwarzenberger P. 2004. Requirement of interleukin-17A for systemic anti-Candida albicans host defense in mice. J. Infect. Dis. 190:624–631. 10.1086/422329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Laan M, Cui ZH, Hoshino H, Lötvall J, Sjöstrand M, Gruenert DC, Skoogh BE, Lindén A. 1999. Neutrophil recruitment by human IL-17 via C-X-C chemokine release in the airways. J. Immunol. 162:2347–2352 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kao C-Y, Chen Y, Thai P, Wachi S, Huang F, Kim C, Harper RW, Wu R. 2004. IL-17 markedly upregulates beta-defensin-2 expression in human airway epithelium via JAK and NF-κB signaling pathways. J. Immunol. 173:3482–3491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Paget C, Trottein F. 2013. Role of type 1 natural killer T cells in pulmonary immunity. Mucosal Immunol. 6:1054–1067. 10.1038/mi.2013.59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Clement CG, Evans SE, Evans CM, Hawke D, Kobayashi R, Reynolds PR, Moghaddam SJ, Scott BL, Melicoff E, Adachi R, Dickey BF, Tuvim MJ. 2008. Stimulation of lung innate immunity protects against lethal pneumococcal pneumonia in mice. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 177:1322–1330. 10.1164/rccm.200607-1038OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wesselkamper SC, Eppert BL, Motz GT, Lau GW, Hassett DJ, Borchers MT. 2008. NKG2D is critical for NK cell activation in host defense against Pseudomonas aeruginosa respiratory infection. J. Immunol. 181:5481–5489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ader F, Jawhara S, Nseir S, Kipnis E, Faure K, Vuotto F, Chemani C, Sendid B, Poulain D, Guery B. 2011. Short term Candida albicans colonization reduces Pseudomonas aeruginosa-related lung injury and bacterial burden in a murine model. Crit. Care 15:R150. 10.1186/cc10276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Winsor GL, Lam DKW, Fleming L, Lo R, Whiteside MD, Yu NY, Hancock REW, Brinkman FSL. 2011. Pseudomonas Genome Database: improved comparative analysis and population genomics capability for Pseudomonas genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 39:D596–D600. 10.1093/nar/gkq869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jones T, Federspiel NA, Chibana H, Dungan J, Kalman S, Magee BB, Newport G, Thorstenson YR, Agabian N, Magee PT, Davis RW, Scherer S. 2004. The diploid genome sequence of Candida albicans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 101:7329–7334. 10.1073/pnas.0401648101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Boutoille D, Marechal X, Pichenot M, Chemani C, Guery B, Faure K. 2009. FITC-albumin as a marker for assessment of endothelial permeability in mice: comparison with 125I-albumin. Exp. Lung Res. 35:263–271. 10.1080/01902140802632290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Koh AY, Priebe GP, Ray C, van Rooijen N, Pier GB. 2009. Inescapable need for neutrophils as mediators of cellular innate immunity to acute Pseudomonas aeruginosa pneumonia. Infect. Immun. 77:5300–5310. 10.1128/IAI.00501-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aujla SJ, Chan YR, Zheng M, Fei M, Askew DJ, Pociask DA, Reinhart TA, McAllister F, Edeal J, Gaus K, Husain S, Kreindler JL, Dubin PJ, Pilewski JM, Myerburg MM, Mason CA, Iwakura Y, Kolls JK. 2008. IL-22 mediates mucosal host defense against Gram-negative bacterial pneumonia. Nat. Med. 14:275–281. 10.1038/nm1710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sonnenberg GF, Monticelli LA, Alenghat T, Fung TC, Hutnick NA, Kunisawa J, Shibata N, Grunberg S, Sinha R, Zahm AM, Tardif MR, Sathaliyawala T, Kubota M, Farber DL, Collman RG, Shaked A, Fouser LA, Weiner DB, Tessier PA, Friedman JR, Kiyono H, Bushman FD, Chang K-M, Artis D. 2012. Innate lymphoid cells promote anatomical containment of lymphoid-resident commensal bacteria. Science 336:1321–1325. 10.1126/science.1222551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lavoie EG, Wangdi T, Kazmierczak BI. 2011. Innate immune responses to Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection. Microbes Infect. 13:1133–1145. 10.1016/j.micinf.2011.07.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu Y, Mei J, Gonzales L, Yang G, Dai N, Wang P, Zhang P, Favara M, Malcolm KC, Guttentag S, Worthen GS. 2011. IL-17A and TNF-α exert synergistic effects on expression of CXCL5 by alveolar type II cells in vivo and in vitro. J. Immunol. 186:3197–3205. 10.4049/jimmunol.1002016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sonnenberg GF, Fouser LA, Artis D. 2011. Border patrol: regulation of immunity, inflammation and tissue homeostasis at barrier surfaces by IL-22. Nat. Immunol. 12:383–390. 10.1038/ni.2025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bals R, Hiemstra PS. 2004. Innate immunity in the lung: how epithelial cells fight against respiratory pathogens. Eur. Respir. J. 23:327–333. 10.1183/09031936.03.00098803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Spits H, Di Santo JP. 2011. The expanding family of innate lymphoid cells: regulators and effectors of immunity and tissue remodeling. Nat. Immunol. 12:21–27. 10.1038/ni.1962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Evans SE, Tuvim MJ, Fox CJ, Sachdev N, Gibiansky L, Dickey BF. 2011. Inhaled innate immune ligands to prevent pneumonia. Br. J. Pharmacol. 163:195–206. 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01237.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yao Z, Painter SL, Fanslow WC, Ulrich D, Macduff BM, Spriggs MK, Armitage RJ. 1995. Human IL-17: a novel cytokine derived from T cells. J. Immunol. 155:5483–5486 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Infante-Duarte C, Horton HF, Byrne MC, Kamradt T. 2000. Microbial lipopeptides induce the production of IL-17 in Th cells. J. Immunol. 165:6107–6115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Aggarwal S, Ghilardi N, Xie M-H, de Sauvage FJ, Gurney AL. 2003. Interleukin-23 promotes a distinct CD4 T cell activation state characterized by the production of interleukin-17. J. Biol. Chem. 278:1910–1914. 10.1074/jbc.M207577200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fossiez F, Djossou O, Chomarat P, Flores-Romo L, Ait-Yahia S, Maat C, Pin JJ, Garrone P, Garcia E, Saeland S, Blanchard D, Gaillard C, Mahapatra Das B, Rouvier E, Golstein P, Banchereau J, Lebecque S. 1996. T cell interleukin-17 induces stromal cells to produce proinflammatory and hematopoietic cytokines. J. Exp. Med. 183:2593–2603. 10.1084/jem.183.6.2593 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu J, Feng Y, Yang K, Li Q, Ye L, Han L, Wan H. 2011. Early production of IL-17 protects against acute pulmonary Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection in mice. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 61:179–188. 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2010.00764.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.De Luca A, Zelante T, D'Angelo C, Zagarella S, Fallarino F, Spreca A, Iannitti RG, Bonifazi P, Renauld J-C, Bistoni F, Puccetti P, Romani L. 2010. IL-22 defines a novel immune pathway of antifungal resistance. Mucosal Immunol. 3:361–373. 10.1038/mi.2010.22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shu Q, Shi Z, Zhao Z, Chen Z, Yao H, Chen Q, Hoeft A, Stuber F, Fang X. 2006. Protection against Pseudomonas aeruginosa pneumonia and sepsis-induced lung injury by overexpression of beta-defensin-2 in rats. Shock 26:365–371. 10.1097/01.shk.0000224722.65929.58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kumar A, Zhang J, Yu F-SX. 2006. Toll-like receptor 2-mediated expression of beta-defensin-2 in human corneal epithelial cells. Microbes Infect. 8:380–389. 10.1016/j.micinf.2005.07.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cirioni O, Ghiselli R, Tomasinsig L, Orlando F, Silvestri C, Skerlavaj B, Riva A, Rocchi M, Saba V, Zanetti M, Scalise G, Giacometti A. 2008. Efficacy of LI-37 and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor in a neutropenic murine sepsis due to Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Shock 30:443–448. 10.1097/SHK.0b013e31816d2269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]