Abstract

Context

Contraceptive discontinuation is a common event. We hypothesize that a significant proportion of contraceptive discontinuations are associated with low motivation to avoid pregnancy; this will be reflected in a significant proportion of pregnancies following discontinuation being reported as intended.

Methods

We use Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) data from 6 countries to explore the extent to which women report pregnancies following contraceptive discontinuation as intended and to identify the characteristics of women who report pregnancies following contraceptive failure or discontinuation for non-pregnancy reasons as intended.

Results

We found that relatively high percentages of births are reported as intended following contraceptive failure and discontinuation for non-pregnancy reasons (16–50% for failure and around 40% for discontinuation for reasons other than desire for pregnancy). While there were few consistent patterns in socio-economic factors associated with reporting births following discontinuation and failure as intended, stronger and more consistent associations were found with variables expected to be linked to motivation such as number of living children, reason for discontinuation, and the time elapsed between discontinuation and pregnancy.

Conclusions

These findings suggest that underlying variation in motivation to avoid pregnancy is an important factor in contraceptive discontinuation.

INTRODUCTION

The extent to which couples who adopt a contraceptive method continue to use it, or another method, is critical for the prevention of unwanted and mistimed births and the avoidance of induced abortions. (1, 2) However, research based on survey data confirms that contraceptive discontinuation is a common event. (3–5) In a comparative analysis of contraceptive histories collected in Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) from 15 developing countries Blanc et al. found the rate of discontinuation of any method due to quality related reasonsa varied from 9 to 34% over a cumulative 12 month period and rose to 17–42% by 24 months. (6) Discontinuations for quality-related reasons exceeded those due to reduced needb in every country. Other researchers have found similarly high rates of discontinuation. (2, 3, 5)

Contraceptive discontinuation is the result of an interplay between motivation to avoid pregnancy and the acceptability of contraceptive options. The decision to continue or discontinue contraception involves the weighing of advantages and disadvantages--the consideration of current and future circumstances and fertility desires. (2) Despite the apparent significance of fertility desires in contraceptive decision making, the majority of contraceptive discontinuation is not due to the desire to get pregnant. According to DHS data collected in the last five years, the percentage of discontinuations that were due to desire to get pregnant ranges from 11.5% in Azerbaijan to 40% in Zimbabwe. (2, 7)

High rates of discontinuation for reasons other than the desire for pregnancy are problematic because of their association with several negative reproductive health outcomes. In countries with moderate-high contraceptive prevalence the majority of unintended pregnancy is the result of contraceptive discontinuation or failure. (2, 4, 8, 9) Blanc et al. found that more than half of recent unwanted fertility was the result of births that were preceded by contraceptive failure or discontinuation in 14 of the 15 countries examined. (6) Contraceptive discontinuation for reasons other than desire to get pregnant was also found to be strongly associated with mistimed and unwanted pregnancy in Guatemala.(10) Additional research has associated contraceptive discontinuation for reasons other than the desire to become pregnant with unmet need for contraception and induced abortion. (8, 9) Unintended pregnancy has been associated with increased risk of maternal morbidity, health behaviors during pregnancy that are associated with adverse maternal health, and adverse fetal, infant and child health outcomes. (11–13) Additionally, unintended pregnancy has been associated with negative psychological effects on women and their children. (14)

Discontinuation is closely linked to demographic characteristics with factors such as fertility intentions, age, parity, and marital status most consistently related to continuity of contraceptive use. (3, 5, 15, 16) Socio-economic factors such as women’s education and socio-economic status tend to be less strongly associated with discontinuation. (3, 16, 17) Knowledge of the factors that lead to contraceptive discontinuation remains incomplete, hampered by the lack of a comprehensive framework that acknowledges the multiple and complex reasons that influence the decision to switch methods or stop using altogether. (18) While many studies conclude that a large amount of unexplained variation in the duration of contraceptive use remains after controlling for factors about which information is available, underlying variation in the motivation to avoid pregnancy is likely a factor in discontinuation. (3, 17, 19)

Some insights on variation in motivation to avoid pregnancy come from United States literature on unintended pregnancy. Data from the US finds that women do not necessarily report pregnancies following contraceptive failure or discontinuation (for reasons other than desire to get pregnant) as unintended. For example, in the US, Trussell, Vaughan, and Stanford (20) found that only 68% of contraceptive failures were reported as unintended pregnancies. Trussell et al. also found that women do not necessarily report that they are unhappy about unintended pregnancies. For example, only 59% of women in the US reporting a pregnancy following a contraceptive failure as an unintended pregnancy reported that they felt unhappy or very unhappy about the pregnancy. (20) The relationship between women’s feelings concerning pregnancy and their contraceptive use is further illustrated by the fact that inconsistent contraceptive use or no contraceptive use has been found to be more common among women who reported that they would be happy about an unintended pregnancy than among those who said that they would be neutral or unhappy about it. (21)

There is less research on different dimensions of pregnancy intentions in developing countries. A study of women’s ambivalence about pregnancy intentions in Burkina Faso, Ghana, and Kenya using data from recent DHS surveys found that around a quarter of married women in Burkina Faso and Ghana who stated that they wanted to delay or stop childbearing reported that it would be no problem or a small problem if they got pregnant in the next few weeks (defined as ambivalent intentions in the study). This percentage was much higher in Kenya at 42.9%. (22)

The findings on women’s feelings towards pregnancies reported as unintended as well as the fact that many pregnancies following contraceptive failures are reported as intended suggests that there is considerable ambivalence toward avoiding pregnancy with many women expressing both positive and negative feelings toward pregnancy simultaneously. (23) This has led Bachrach and Newcomer to argue that pregnancy intentions fall along a continuum with multiple dimensions. (24) Further evidence for a continuum of fertility intentions comes from the work of Schoen et al. which found a strong, monotonic decline in the probability of a subsequent birth as the reported intention for another birth went from yes, very sure, through yes, unsure and no, unsure, to no, very sure.(25) . More recently, Santelli and colleagues demonstrate that more nuanced indicators of pregnancy intentions that capture different dimensions of intentions and strength of intentions were strongly associated with the decision to have an abortion compared to a live birth, also in the US. (26) These studies provide further evidence that fertility intentions fall along a continuum and that the intensity of those intentions is an important factor in subsequent fertility behavior, and therefore by implication, in subsequent contraceptive adoption and discontinuation. Given a continuum of fertility intentions, contraceptive continuation is likely to be an indicator of a strong motivation to avoid pregnancy while discontinuation conversely may reflect low levels of motivation.

While the extent to which pregnancies following contraceptive failure are reported as unintended has been explored in the United States, no studies in developing countries have directly explored this concern, although Barden-O’Fallon et al. document that 7.3% of live births reported as intended followed recent contraceptive discontinuation for reasons other than desire for pregnancy in Guatemala. (10) Furthermore, there is little research in developing countries on the effects of motivation to avoid pregnancy on contraceptive discontinuation, other than indirectly through desire to space or limit future pregnancies. Using DHS data from 6 countries, this study explores the extent to which women report pregnancies following discontinuation as unintended and attempts to identify the characteristics of women who report pregnancies following contraceptive failure or discontinuation for other reasons as intended. We hypothesize that a significant proportion of contraceptive discontinuations are associated with low motivation to avoid pregnancy; this will be reflected in a significant proportion of pregnancies following discontinuation being reported as intended. Furthermore, it is predicted that the proportion of pregnancies following discontinuation that are reported as intended will be most strongly associated with variables likely to be associated with motivation such as family formation stage (e.g. age, number of living children or whether a woman has reached her ideal family size), and contraceptive behavior (e.g. the reason for discontinuation, method used, or time elapsed between discontinuation and the birth).

METHODS

Data and Variables

This study uses data from six Demographic and Health Surveys, nationally representative household surveys that collect data on a wide range of indicators in the areas of health and reproductive behavior. The surveys employ national probability samples of households and, in general, use a two stage sampling strategy. The DHS offers advantages for comparative analysis because they use standardized instruments and standardized training, data collection and data processing procedures. For this study, we selected surveys from Bangladesh, the Philippines, Kazakhstan, the Dominican Republic, Kenya and Zimbabwe. These countries were chosen to achieve wide geographic coverage and variation in the family planning environment. Survey years range from 1999 to 2003c and sample sizes range from 4800 to 23384 women.

With the exception of Bangladeshd, the surveys collected information on pregnancies, births and contraceptive use from both married and unmarried women between the ages of 15 and 49. The contraceptive histories are collected through a “calendar” that records monthly contraceptive use, pregnancy and birth status as well as the reason for discontinuing contraceptive use for five calendar years before the survey.(27) The calendar data enables identification of the timing of contraceptive behavior prior to each live birthe.

Using data from the contraceptive calendar, the most recent contraceptive behavior in the pregnancy interval before each live birth was categorized as follows: contraceptive failure, discontinuation of contraceptive use to get pregnant, discontinuation for other reasonsf or no use of contraception. Our rationale for this categorization of previous contraceptive behavior is that women who discontinue for reasons other than desire to get pregnant actively discontinued (unlike women who failed) but did not express a desire for pregnancy (unlike women who discontinued to get pregnant). For a woman’s first birth the contraceptive behavior between marriage and the first pregnancy was identified. In this analysis, each live birth is treated as a separate observation. Thus, the analysis is birth-based rather than woman-based; individual women may contribute more than one live birth to the sample.

Demographic and Health Surveys also provide information on pregnancy intentions for all live births and current pregnancies in the five years preceding the survey. Pregnancy intentions are defined as whether the child was wanted at the time of pregnancy (defined as wanted then), wanted later, or not wanted at any time. In this study, births reported as wanted later or not at all were classified as unintended births. Births reported as wanted at the time of the pregnancy were classified as intended. Information on intentions was extracted from the maternity history and matched with the calendar data on preceding contraceptive behavior for each live birth.

Descriptive, bivariate and multivariate analyses were performed. Cross-tabulations were used to examine the bivariate relationship between preceding contraceptive behavior and reported intention by country. Next, we conducted multivariate logistic regression analysis to assess the association between selected explanatory variables and the probability of reporting a birth following discontinuation or failure as intended. Only births following contraceptive failure or discontinuation for reasons other than to get pregnant were included in the multivariate analysis since this is the subset of births we would expect to be unintended.

Covariates for the multivariate analysis were selected to identify key characteristics of women expected to be associated with motivation to avoid pregnancy. Variables were selected based on theoretical association with contraceptive discontinuation or because previous analyses have shown them to be significant determinants of discontinuation behavior. (3, 16, 28) Socio-demographic variables included in the multivariate analysis were: woman’s age, marital statusg, and number of living children (all three defined at the time of the index conception), area of residence, women’s education, and religionh. To capture women’s family formation stage a variable was constructed to identify whether she had exceeded her ideal family size. This was derived from the reported total desired family size and the number of surviving children prior to the index birth. From those two variables, a three-fold classification was made: desired number greater than, equal to, or less than actual number.

The multivariate models also included reason for discontinuation, defined as discontinuation due to contraceptive failure or discontinuation for other reasons, type of contraception used prior to the index birth, and the time elapsed between the preceding discontinuation and the index conception. Women who experience a contraceptive failure did not actively discontinue which we hypothesize will be indicative of higher motivation to avoid pregnancy and higher probability of reporting the subsequent birth as intended. A longer period between a discontinuation and subsequent conception is expected to be associated with changes in personal circumstances and motivations to avoid pregnancy. Consequently, the discontinuation of the previous methods is expected to be less relevant to the intention status of the subsequent birth the longer the time elapsed between the two events.

All analyses were conducted using the STATA statistical package (Stata Corp, College Station, Texas). The survey sample weights for each birth were applied. Robust standard errors were estimated to take into account the cluster design of the survey and the fact that women can contribute more than one birth to the sample.

FAMILY PLANNING CONTEXT

Table 1 presents selected standard fertility and family planning indicators for the six countries as background on their fertility and family planning contexts. All six countries included in this study display moderate-high contraceptive use with prevalence of any contraceptive method among married reproductive age women ranging from a low of 39.3% in Kenya to a high of 69.8% in the Dominican Republic. Method mix varies across countries: oral contraceptive pills are the most common method in both Zimbabwe and Bangladesh, injections are most popular in Kenya, while long-acting and permanent methods are the most common Kazakhstan (IUDs) and in the Dominican Republic (female sterilization). In the Philippines traditional and folk methods are the most common method while the pill is the most common modern method (data not shown). (7) Among the study countries, the total fertility rate is lowest in Kazakhstan with just 2.0 children born to each woman. Kenya has the highest total fertility rate at 4.9 children per woman.

Table 1.

Selected Family Planning Indicators in Study Countries

| Country and date of DHS |

% of currently married women ages 15–49 currently using any form of contraception |

Total fertility rate for women ages 15–49 |

First year discontinuation rate (all methods)i |

% births in the 5 years prior to the survey that were unintended |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zimbabwe (1999) | 53.5 % | 4.0 | 20.2% | 37.4 % |

| Kenya (2003) | 39.3 % | 4.9 | 37.6% | 44.5 % |

| Bangladesh (1999/2000) | 54.3 % | 3.3 | 48.3% | 32.8 % |

| Philippines (2003) | 48.9 % | 3.5 | 39.1% | 44.3 % |

| Kazakhstan (1999) | 66.1 % | 2.0 | 38.5% | 17.2 % |

| Dominican Republic (2002) | 69.8 % | 3.0 | 47.5% | 43.2 % |

Source: DHS Statcompiler (7).

Contraceptive discontinuation rates are high in all study countries. The percentage of women discontinuing a method in the first year of use for any reason ranges from 20.2% in Zimbabwe to 47.5% of women in the Dominican Republic. (See Table 1) In every country, except the Philippines and Kazakhstan, the desire to become pregnant was one of the two most common reasons for discontinuation of specific methods. Side effects were another major cause of discontinuation in every country except for Zimbabwe and Kazakhstan. Discontinuation due to contraceptive failure was a top reason in Zimbabwe, the Philippines, and Kazakhstan. (7, 29) Only in Kazakhstan was switching to a more effective method a top reason for discontinuing another method. (7, 29, 30)

Unintended births are common in most of the countries included in this study. The percentage of births in the five years prior to the DHS Survey that were wanted later or not wanted at all ranges from a low of 17.2% in Kazakhstanj to a high of 44.5% in Kenya. Aside from Kazakhstan, all five of the other study countries reported at least a third of births as unintended. (See Table 1)

RESULTS

Descriptive Analysis

The distribution of live births according to preceding contraceptive behavior is summarized in Table 2. Approximately half to three-quarters of all live births in each country occurred after contraceptive non-use. In every country except the Philippines and the Dominican Republic discontinuation to get pregnant was the next most common contraceptive behavior prior to a live birth. Nearly 19% of live births in the Dominican Republic occurred following discontinuation for reasons other than to get pregnant, while the corresponding percentage was relatively low in Kazakhstan desire for (7.0%). The proportion of live births preceded by contraceptive failure was generally relatively low ranging from 6.8 % in Kenya to over 11% in the Dominican Republic and the Philippines.

Table 2.

Percent Distribution of Live Births by Preceding Contraceptive Behavior

| Contraceptive failure |

Discontinuati on to get pregnant |

Discontinuation for other reasons |

Non -use |

Total | N | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bangladesh | 7.8 | 16.6 | 11.5 | 64.1 | 100.0 | 6881 |

| Dominican Republic | 11.1 | 16.0 | 18.9 | 54.0 | 100.0 | 10733 |

| Kazakhstan | 8.0 | 16.4 | 6.9 | 68.7 | 100.0 | 1420 |

| Kenya | 6.8 | 9.3 | 8.5 | 75.4 | 100.0 | 6001 |

| Philippines | 11.4 | 7.0 | 8.8 | 72.9 | 100.0 | 6898 |

| Zimbabwe | 8.2 | 23.6 | 11.9 | 56.3 | 100.0 | 3504 |

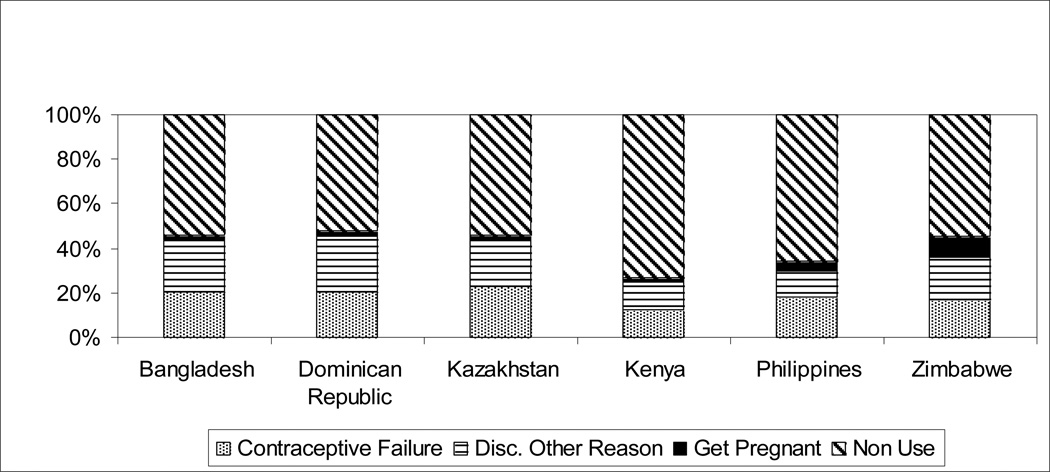

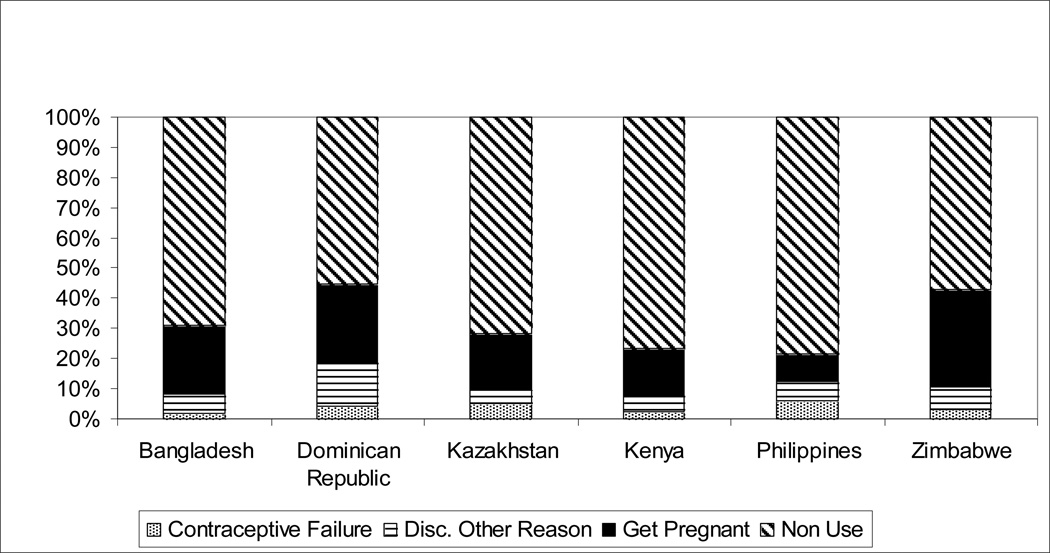

Figures 1 and 2 show the distribution of preceding contraceptive behavior separately for intended and unintended births. As expected, a much higher percentage of unintended births are preceded by contraceptive discontinuation or failure than are intended births in all six countries. The percentage of unintended births that followed a contraceptive failure ranges from 13% in Kenya to 23% in Kazakhstan, while the percentage that followed discontinuation for reasons other than desire to get pregnant ranges from 12% in Kenya and the Philippines to 25% in the Dominican Republic. In each study country at least half of all births reported as unintended occurred after no contraceptive use. With the exception of Zimbabwe, less than 4 percent of births classified as unintended occurred after discontinuation due to desire for pregnancy. The majority of births reported as intended followed either no use of contraception or discontinuation to get pregnant in all 6 countries (Figure 2). The percentage of intended births that followed discontinuation for reasons other than desire for pregnancy ranged from 4% in Kazakhstan to 14% in the Dominican Republic, while the percentage of intended births that followed contraceptive failure ranged from 2% in Bangladesh to 6% in the Philippines.

Figure 1.

Percentage Distribution of Unintended Live Births by Preceding Contraceptive Behavior

Figure 2.

Percentage Distribution of Intended Live Births by Preceding Contraceptive Behavior

Bivariate Analysis

Table 3 explores the intention status reported for births following each type of contraceptive behavior in each country. Large, statistically significant differences in the distribution of births by reported intention exist for each contraceptive behavior in all countries. With the exception of Kazakhstan, the remaining five countries show high proportions of live births following either contraceptive failure or discontinuation for reasons other than desire for pregnancy are reported as unintended (wanted later or not wanted). Nevertheless, the percentage of live births reported as intended following contraceptive failure ranges from 16% in Bangladesh to 54% in Kazakhstan, while the percentage of live births reported as intended following discontinuation for reasons other than desire for pregnancy ranges from 37% in Kenya to 51% in Kazakhstan. The relatively high percentage of births reported as intended following contraceptive failure or discontinuation for reasons other than desire for pregnancy in Kazakhstan is likely the result of liberal abortion laws there; pregnancies that were strongly not wanted are likely to result in abortion so the pregnancies carried to term in Kazakhstan selectively reflect more ambivalent fertility preferences. Kazakhstan also has the highest percentage of live births reported as intended following discontinuation due to desire for pregnancy and non-use.

Table 3.

Percent Distribution of Intention Status of Live Births by Preceding Contraceptive Behavior and Country

| Contraceptive Behavior | N | Intention of Live Birth | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intended | Unintended | |||

| Wanted Then |

Wanted Later |

Not Wanted |

||

| Contraceptive Failure | ||||

| Bangladesh | 538 | 15.6 | 45.0 | 39.4 |

| Philippines | 781 | 29.5 | 36.5 | 34.0 |

| Kazakhstan | 113 | 53.5 | 26.8 | 19.7 |

| Dominican Republic | 1186 | 21.2 | 57.1 | 21.7 |

| Kenya | 409 | 17.7 | 43.4 | 38.9 |

| Zimbabwe | 287 | 24.2 | 63.6 | 12.2 |

| Discontinuation for Reasons Other Than Desire for Pregnancy | ||||

| Bangladesh | 789 | 37.7 | 30.2 | 32.1 |

| Philippines | 604 | 38.6 | 29.1 | 32.3 |

| Kazakhstan | 98 | 51.4 | 15.9 | 32.6 |

| Dominican Republic | 2013 | 43.9 | 37.9 | 18.2 |

| Kenya | 510 | 36.8 | 31.9 | 31.3 |

| Zimbabwe | 416 | 39.7 | 46.4 | 13.9 |

| Discontinuation to get Pregnant | ||||

| Bangladesh | 1141 | 94.2 | 4.0 | 1.8 |

| Philippines | 481 | 72.4 | 16.2 | 11.5 |

| Kazakhstan | 232 | 97.6 | 0.8 | 1.6 |

| Dominican Republic | 1699 | 93.3 | 5.1 | 1.6 |

| Kenya | 560 | 91.6 | 4.9 | 3.5 |

| Zimbabwe | 824 | 85.5 | 11.1 | 3.4 |

| Non use | ||||

| Bangladesh | 4400 | 73.2 | 17.0 | 9.8 |

| Philippines | 4991 | 59.1 | 22.3 | 18.6 |

| Kazakhstan | 971 | 87.2 | 6.3 | 6.4 |

| Dominican Republic | 5760 | 58.7 | 28.3 | 13.0 |

| Kenya | 4502 | 56.7 | 24.5 | 18.8 |

| Zimbabwe | 1969 | 63.7 | 31.0 | 5.3 |

As expected, births following discontinuation due to desire to get pregnant are the most likely to be reported as intended in all 6 countries, while those following contraceptive failure are the least likely to be reported as intended, except in Kazakhstan where births following discontinuation for reasons other than desire for pregnancy are slightly less likely to be reported as intended than births following contraceptive failure. Births following non-use are more likely to be reported as intended than births following discontinuation for reasons other than desire to get pregnant. This is consistent with our hypothesis because non-users include women who did not initiate contraceptive use because they want to get pregnant and women who did not want to get pregnant but whose fertility preferences were not sufficient to motivate them to initiate contraception (i.e. who likely had more ambivalent preferences than women who initiated contraceptive use).

Multivariate Analysis

The multivariate analysis focuses only on births following contraceptive failure and discontinuation for reasons other than desire for pregnancy to explore factors associated with reporting these births as intended. We hypothesize that such apparently inconsistent reporting is indicative of ambivalent motivation to avoid pregnancy among users. Results of the multivariate analysis show a number of factors are significant independent predictors of births being reported as intended following either contraceptive failure or discontinuation for reasons other than the desire for pregnancy (See Table 4). However, there is variation in the effect and significance of socio-demographic characteristics across countries. Only age, number of living children, reason for discontinuation and the number of months between discontinuation and the index birth are significant in at least half of the countries examined.

Table 4.

Odds Ratios of Births Reported as Intended Following Contraceptive Failure and Discontinuation for Reasons Other Than Desire for Pregnancy, by Country

| Characteristics | Bangladesh | Dominican Republic |

Kazakhstan | Kenya | Philippines | Zimbabwe |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | ||||||

| Under 25a | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 25–34 | 1.23† | 1.23† | 0.84 | 1.96** | 1.21 | 1.64† |

| 35–49 | 0.95 | 1.65* | 0.80 | 2.18* | 1.02 | 2.59* |

| Education | ||||||

| Nonea | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Primary | 0.71* | 0.69 | n/a | 0.54 | 0.80 | 1.82† |

| Secondary + | 0.66* | 0.63† | n/a | 0.44 | 0.61 | 1.91† |

| Place of Residence | ||||||

| Urbana | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Rural | 1.10 | 0.86 | 1.10 | 1.58* | 0.84 | 1.12 |

| Religion | ||||||

| Other Religiona | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Christian | n/a | 1.01 | n/a | 0.71† | 1.00 | 0.97 |

| Muslim | 0.93 | n/a | 1.14 | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Marital Status | ||||||

| Never Marrieda | n/a | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Married | n/a | 1.42 | 0.42 | 2.16* | 0.92 | 1.90* |

| Number of living Children | ||||||

| 0–2 | 2.09* | 1.23 | 1.52 | 2.28** | 1.45† | 0.96 |

| 3–4a | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 5 or more | 0.18** | 0.26** | 0.40 | 0.24** | 0.71 | 0.60 |

| Achieved Family Size | ||||||

| Less than Desireda | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Same as Desired | 0.67† | 0.60** | 0.47 | 0.64† | 0.93 | 0.58† |

| Exceeds Desired Size | 0.85 | 0.45** | 0.41 | 0.99 | 0.83 | 0.21** |

| Method | ||||||

| Pill | 0.93 | 1.17 | 1.51 | 0.73 | 0.75† | 1.60* |

| Other Moderna | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Reasons for Discontinuation | ||||||

| Failure | 0.48** | 0.41** | 1.59 | 0.53** | 0.73* | 0.34** |

| Other reason than pregnancya | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Months between discontinuation & preg. | ||||||

| 1–3 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 4–6 | 1.43† | 1.23 | 2.08 | 1.14 | 0.71 | 0.88 |

| 7–12 | 1.85** | 1.81** | 1.96 | 2.52** | 1.65† | 0.37* |

| 13+ | 2.94** | 2.09** | 2.27 | 3.30** | 1.53† | 0.82 |

| N | 1,282 | 3,243 | 202 | 805 | 1,373 | 716 |

Note:

Denotes reference category;

p< 0.01

p< 0.05

p< 0.10

Older women are more likely than younger women to report births as intended following discontinuation (other than to get pregnant) or failure in Dominican Republic, Kenya, and Zimbabwe. In Bangladesh, Dominican Republic, and Kenya the odds of reporting births following contraceptive failure and discontinuation (other than to get pregnant) as intended decreases as the number of living children increases. A similar pattern is seen in Kazakhstan and the Philippines but the relationship is not statistically significant. In all countries except Kazakhstan women reporting method failure were less likely to report the birth as intended compared to those discontinuing for reasons other than the desire for pregnancy. The number of months between the preceding discontinuation and the index conception also emerges as significant in four of the six countries. In Bangladesh, Dominican Republic, and Kenya a longer duration between discontinuation and the index conception is associated with increased odds of reporting a birth following failure or discontinuation (other than to get pregnant) as intended, as expected. However, in Zimbabwe a duration of 7–12 months between discontinuation and the index conception is associated with lower odds of reporting the birth as intended.

DISCUSSION

DHS data from six developing countries with moderate to high levels of contraceptive use were used to investigate whether live births following contraceptive failure and discontinuation for reasons other than desire for pregnancy were reported as intended. Our main hypotheses were 1) a significant proportion of contraceptive discontinuations are associated with low motivation to avoid pregnancy which will be reflected in a significant proportion of pregnancies following discontinuation being reported as intended; and 2) the proportion of pregnancies following discontinuation that are reported as intended will be most strongly associated with variables likely to be associated with motivation such as family formation stage or contraceptive behavior.

The study findings support our two hypotheses. We found that relatively high percentages of births are reported as intended following contraceptive failure and discontinuation for reasons other than pregnancy (16–50% for failure and around 40% for discontinuation for reasons other than desire for pregnancy). While there were few consistent patterns in socio-economic factors associated with reporting births following discontinuation and failure as intended, stronger and more consistent associations were found with variables expected to be linked to motivation such as number of living children, the reason for discontinuation, and the time elapsed between discontinuation and the index conception. These findings suggest that underlying variation in motivation to avoid pregnancy is an important factor in contraceptive discontinuation. It is relevant to note that Strickler et al. found that reported reason for discontinuation was the least reliable variable collected in the calendar in Morocco. (31) Inconsistent reporting could result if multiple factors play into the decision to discontinue use; which one gets reported on a given day may vary. Desire for pregnancy, or at least lack of strong desire to avoid pregnancy, could be an underlying factor in discontinuation even if it is not reported as the primary reason for discontinuation.

Although we find relatively high proportions of births following contraceptive failure and discontinuation for reasons other than desire for pregnancy are reported as intended, our findings also demonstrate an expected and consistent relationship between preceding contraceptive behavior and unintended births, with births following discontinuation to get pregnant being the least likely to be reported as unintended and births following contraceptive failure generally being the most likely to be reported as unintended. These findings are consistent with the findings of Barden-O’Fallon at al. in Guatemala. (10) Overall, these findings support the idea of a continuum of motivation to avoid pregnancy underlying contraceptive discontinuation behavior.

Although some studies have found evidence of program effects in reducing contraceptive discontinuation, (32–35) other research has found that discontinuation may not be readily amenable to existing programmatic interventions. (36–39) Our findings highlight the role of the strength of individual fertility desires as an important factor in the dynamics of contraceptive use even among women who express a desire to space or limit childbearing sufficient to initiate contraceptive use. Understanding better the strength of motivation of women and couples to avoid pregnancy may aid in helping them to define appropriate reproductive health strategies. Studies of contraceptive discontinuation consistently find lower discontinuation among users of long acting methods that require passive use and active discontinuation such as IUDs and implants than among users of other reversible methods that require active use and passive discontinuation (e.g. pills, condoms). (2, 3, 5, 28) Ease of maintaining use is a factor to consider in the context of how strongly women and couples want to avoid pregnancy.

There are some limitations of the current study to note. The study relies on retrospective reports of women on the intention status of pregnancies. Such reports are known to be subject to recall bias and post-event rationalization, although the extent of these problems is generally not deemed sufficient to invalidate the use of retrospective reports.(13, 40) More nuanced measures of pregnancy intentions that capture the multiple dimensions and intensity of pregnancy intentions, such as those explored by Santelli and colleagues, would allow more thorough analysis of the apparent inconsistency between contraceptive discontinuation and reported intention status of live births among some women. (26) Calendar data are also subject to recall bias, particularly for the reasons for discontinuation as noted above. (31) Nevertheless, this study points to strong internally-consistent relationships between contraceptive behavior and unintended pregnancy at the population level.

Another limitation is that our study focuses only on the intention status of live births. Women who are most motivated to avoid a pregnancy following discontinuation will be more likely to terminate their pregnancies than other women.26This selection bias means that we will likely underestimate the extent of unintended pregnancy following contraceptive failure and discontinuation for reasons other than desire for pregnancy. Evidence of this effect is seen in the results for Kazakhstan where abortion is legal and widely used; the relatively low levels of unintended births reported following failure and discontinuation for reasons other than desire for pregnancy there compared to other countries in this study is likely due to the widespread use of induced abortion among women who were the most strongly motivated to avoid pregnancy. The extent of this selection effect will depend on the level of induced abortion in the population, which in turn will depend on the legal status and social acceptability of abortion in that population. DHS does not collect data on the intention status of non-live births, however, and in general does not distinguish between induced and spontaneous abortions except in countries where abortion is legal and widely used. Therefore, it is not possible to include non-live births in this analysis. However, the objective of this study is not to examine the full continuum of motivation to avoid pregnancy, but rather to examine what insights into the role of motivation in discontinuation can be obtained by looking at how women report the intention status of live births following failure and discontinuation. The fact that a significant number of women go on to have births that they report as intended following contraceptive failure and discontinuation for reasons other than desire for pregnancy even in Kazakhstan where abortion is legal and widespread supports our hypothesis that a portion of contraceptive discontinuation is associated with ambivalent fertility preferences.

To conclude, contraceptive discontinuation is a complex process in which the strength of fertility preferences plays an important role. Individual women and couples must weigh their feelings about their chosen contraceptive method with their feelings about pregnancy. While contraceptive discontinuation is clearly an important factor in unintended pregnancy, not all discontinuation results in unintended pregnancy and reducing contraceptive discontinuation will be challenging in light of ambivalence both about contraceptive options and pregnancy intentions. Ultimately unintended pregnancy will be reduced by identifying those women who strongly want to avoid pregnancy and finding ways to help them successfully initiate and maintain contraceptive use.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to acknowledge Mr. Paul Brodish for his STATA programming assistance. Support for this research was provided by the US Agency for International Development (USAID) through the MEASURE Evaluation Project (GPO-A-00-03-00003-00). The author’s views expressed in this article do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the US Government.

Footnotes

Quality related reasons defined by the authors include method failure, side effects, partner disapproval, health concerns and cost

Reduced need defined by the authors includes desire for pregnancy, marital dissolution or menopause

More recent DHS surveys have become available in all countries except Kazakhstan since these analyses were first conducted. Updating the analysis to include these more recent surveys would mean that the surveys included would span the period 1999–2007. We decided to include surveys that relate to a similar time period (1999–2003) rather than use the most recent surveys in these cases since the relevance of the findings of this study are not dependent on the currency of the survey data.

Due to cultural sensitivities regarding interviewing never married women about sexual behavior and contraceptive use, the Bangladesh DHS interviewed only ever-married women. In Bangladesh, the contraceptive calendar includes contraceptive use before marriage for women who married during the calendar period, but no information is available on contraceptive use or discontinuation among never-married women.

Methodological studies have shown contraceptive use histories collected through the calendar format to be more complete, internally consistent and accurate than data collected in a traditional approach with structured questions. (41, 42) Curtis and Blanc found evidence that heaping of reported durations of use on preferred digits was not severe enough to significantly affect estimates of discontinuation. (3) Further, they demonstrate that estimates of contraceptive prevalence from the calendar data and current status data at corresponding points in time were very close. Using data for overlapping time periods from the 1992 Morocco DHS and 1995 Morocco Panel Survey, Strickler et al. found that reporting of contraceptive behavior at the aggregate level was fairly reliable. However, there was unreliability in individual level responses particularly for complex histories. (31)

Other reasons include: side effects, health problems, partner disapproved, access/availability, want more effective method, inconvenient to use, infrequent sex, cost, separated/widowed, fatalistic, difficult to get pregnant, marital dissolution, don’t know and others. In this study, no distinction is made between reasons that suggest reduced need (such as infrequent sex, separation/widowhood) and reasons that do not suggest reduced need (e.g. side effects) in this other category. While this is often an important distinction, it is less important in this study because we focus on women who subsequently became pregnant and were consequently exposed to the risk of pregnancy at some point following discontinuation.

The marital status variable was not included in the model for Bangladesh because the sample included only ever-married women.

Due to the differences between the six countries, the most prevalent religion for each country were assigned as the religion dummy variable. The reference category was then an affiliation to other religion or no-religion. Muslim was the majority religion for Bangladesh and Kazakhstan while the other countries had Christian as the majority religion.

This is the percent of contraceptive users who discontinue any reversible method of contraception due to method failure, desire for pregnancy, health reasons or other reasons in the first twelve months of use. Switching from one method to another method is considered a discontinuation of the original method.

High rates of abortion contribute to the relatively low prevalence of unintended births in Kazakhstan.

Contributor Information

Siân Curtis, Carolina Population Center and Dept Maternal and Child Health, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (UNC).

Emily Evens, Family Health International and Dept. Maternal and Child Health, UNC.

William Sambisa, Management Sciences for Health.

References

- 1.Cleland J, Ali M. Reproductive consequences of contraceptive failure in 19 developing countries. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2004 Aug;104(2):314–320. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000134789.73663.fd. 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blanc A, Curtis S, Croft T. Monitoring contraceptive continuation: links to fertility outcomes and quality of care. Stud Fam Plan. 2002;33(2):127–140. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2002.00127.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Curtis SL, Blanc AK. DHS Analytical Reports No. 6. Calverton, Maryland: Macro International Inc.; 1997. Determinants of contraceptive failure, switching, and discontinuation: an analysis of DHS contraceptive histories. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blanc A, Curtis S, Croft T. Monitoring contraceptive continuation: links to fertility outcomes and quality of care. Stud Fam Plan. 2002;33(2):127–140. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2002.00127.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ali M, Cleland J. Contraceptive discontinuation in six developing countries: a cause-specific analysis. International Family Planning Perspectives. 1995;21(3):92–97. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blanc A, Curtis S, Croft T. Quality of care and fertility consequences. Chapel Hill, NC: MEASURE Evaluation, Carolina Population Center and University of North Carolina; 1999. Does contraceptive discontinuation matter? [Google Scholar]

- 7.MEASURE DHS. [cited 2007];STATCompiler. 2006 Available from: http://www.statcompiler.com/statcompiler/. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Casterline J, El-Zanaty F, El-Zeini L. Unmet need and unintended fertility: longitudinal evidence from upper egypt. International Family Planning Perspectives. 2003;29(4):158–166. doi: 10.1363/ifpp.29.158.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jain A. Should eliminating unmet need for contraception continue to be a program priority? Intl Fam Plan Persp. 1999;25(Suppl):S39–S43. S9. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barden-O'Fallon J, Speizer I, White J. Association between contraceptive discontinuation and pregnancy intentions in Guatemala. 6. Vol. 23. Rev Panam Salud Publica.; 2008. pp. 410–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Division of Reproductive Health National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Unintended Pregnancy. [cited 2006 October 30];2006 Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/UnintendedPregnancy/index.htm.

- 12.Division of Reproductive Health National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Pregnancy risk assessment monitoring system (PRAMS): PRAMS and unintended pregnancy. [cited 2006 October 31];2006 Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/PRAMS/UP.htm.

- 13.Santelli J, Rochat R, Hatfield-Timajchy K, Colley Gilbert B, Curtis K, Cabral R, et al. The measurement and meaning of unintended pregnancy. Perps Sexual and Repro Health. 2003;35(2):94–101. doi: 10.1363/3509403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hardee K, Eggleston E, Wong EL, Hull T IRWANTO. Unintended pregnancy and women’s psychological well-being in Indonesia. J biosoc Sci. 2004;36:617–626. doi: 10.1017/s0021932003006321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ali M, Cleland J. Determinants of contraceptive discontinuation in six developing countries: A discrete event history analysis approach. Annual Meeting of the Population Association of America; May 9–11; New Orleans. 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ali M, Cleland J. Determinants of contraceptive discontinuation in six developing countries. J Bios Sci. 1999;31:343–360. doi: 10.1017/s0021932099003430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang F, Tsui A, Suchindran C. The determinants of contraceptive discontinuation in northern india: a multilevel analysis of calendar data. Chapel Hill: MEASURE Evaluation; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Blanc AK, RamaRao S, Curtis S. Contraceptive discontinuation: a proposal for a new framework and research agenda. 2005 Unpublished draft. [Unpublished project document]. In press. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Steele F, Diamond I, Wang D. The determinants of the duration of contraceptive use in China: A multilevel multinomical discrete-hazards modeling approach. Demography. 1996;33(1):12–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Trussell J, Vaughan B, Stanford J. Are all contraceptive failures unintended pregnancies? evidence from the 1995 national survey of family growth. Fam Plan Persp. 1999;31(5):246–247. 60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sable M, Libbus M. Pregnancy intention and pregnancy happiness: are they different? Mat and Child Health J. 2000;4(3):191–196. doi: 10.1023/a:1009527631043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Speizer I. Using strength of fertility motivations to identify program strategies. Intl Fam Plan Perspec. 2005 Dec;32(4):185–191. doi: 10.1363/3218506. 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zabin L. Ambivalent Feelings about parenthood may lead to inconsistant contraceptive use--and pregnancy. Fam Plan Persp. 1999;31(5):250–251. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bachrach C, Newcomer S. Intended pregnancies and unintended pregnancies: distinct categories or opposite ends of a continuum? Fam Plan Persp. 1999;31(5):251–252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schoen R, Astone N, Kim Y, Nathanson C, Fields J. Do fertility intentions affect fertility behavior? J Marriage and Fam. 1999;61(3):790–799. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Santelli JDL, Lindberg MG, Orr LB, Speizer I. Towards a multidimensional measure of pregnancy intentions: evidence from the united states. Stud Fam Plan. 2009 Jun;40(2):87–100. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2009.00192.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.MEASURE DHS. Calverton, MD: ORC Macro; 2001. DHS Model Questionnaire with Commentary - Phase 4 (1997–2003) [Google Scholar]

- 28.Steele F, Curtis S. Appropriate methods for analyzing the effect of method choice on contraceptive discontinuation. Demography. 2003;40(1):1–22. doi: 10.1353/dem.2003.0009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS) [Kenya], Ministry of Health (MOH) [Kenya], ORC Macro. Kenya Demographic and Health Survey. Calverton, MD: CBS, MOH and ORC Macro; 2003. 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Academy of Preventive Medicine [Kazakhstan], Macro International Inc. Kazakhstan Demographic and Health Survey 1999. Calverton, MD: Academy of Preventive Medicine and Macro International Inc.; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Strickler J, Magnani R, McCann H, Brown L, Rice J. The reliability of reporting of contraceptive behavior in DHS calendar data: evidence from Morocco. Stud Fam Plan. 1997;28(1):44–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Koenig M, Hossain M, Whittaker M. The influence of quality of care upon contraceptive use in rural Bangladesh. Stud Fam Plan. 1997 Dec;28(4):278–289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pariani S, Heer D, Van Arsdol M., Jr Does choice make a difference to contraceptive use? evidence from east java. Stud Fam Plan. 1991;22(6):384–390. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.RamaRao S, Lacuesta M, Costello M, Jones H. The link between quality of care and contraceptive use. Intl Fam Plan Persp. 2003;29(2):76–83. doi: 10.1363/ifpp.29.076.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cotton NSJ, Maidouka H, Taylor-Thomas JT, Turk T. Early discontinuation of contraceptive use in Niger and the Gambia. Int Fam Plan Perspect. 1992;18(4):145–149. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Frontiers in Reproductive Health. OR Summary 30: Services improve quality of care but fail to increase FP continuation. Washington, DC: Population Council; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Aradhya K. Improving Contraceptive Continuation: Partnering to Generate and Apply Knowledge for Better Results. Washington, DC: Family Health International; 2005. Nov 29–30, Improving contraceptive continuation: focus on hormonal methods: a review of the literature. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Leon F, Rios Z, Zumaran A. Final Report: Improving provider-client interactions at Peru MOH clinics: extent, benefit, cost. Washington, DC: Fronteirs in Reproductive Health, Population Council; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Costello M, Sanogo D, Townsend T. Final Report 33: Documenting impact of quality of care on women's reproductive health, Philippines and Senegal. Washington, DC: Frontiers in Reproductive Health, Population Council; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bankole A, Westoff C. The consistancy and validity of reproductive attitudes: evidence from morocco. J Bios Sci. 1998;30(4):439–455. doi: 10.1017/s0021932098004398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Goldman N, Moreno L, Westoff C. Peru experimental study: an evaluation of fertility and child health information. Columbia, MD: Office of Population Research, Princeton University and Institute for Resources Development (IRD) Macro System Inc.; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Westoff C, Goldman N, Moreno L. Dominican Republic experimental study: an evaluation of fertility and child health information. Columbia, MD: Office of Population Research, Princeton University and Institute for Resources Development (IRD) Macro System Inc.; 1990. [Google Scholar]