Mutational analysis of maize genes encoding a plastidial pyrophosphorylase demonstrates that cytosolic and amyloplast enzymes both contribute to endosperm starch content.

Abstract

ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase (AGPase) provides the nucleotide sugar ADP-glucose and thus constitutes the first step in starch biosynthesis. The majority of cereal endosperm AGPase is located in the cytosol with a minor portion in amyloplasts, in contrast to its strictly plastidial location in other species and tissues. To investigate the potential functions of plastidial AGPase in maize (Zea mays) endosperm, six genes encoding AGPase large or small subunits were characterized for gene expression as well as subcellular location and biochemical activity of the encoded proteins. Seven transcripts from these genes accumulate in endosperm, including those from shrunken2 and brittle2 that encode cytosolic AGPase and five candidates that could encode subunits of the plastidial enzyme. The amino termini of these five polypeptides directed the transport of a reporter protein into chloroplasts of leaf protoplasts. All seven proteins exhibited AGPase activity when coexpressed in Escherichia coli with partner subunits. Null mutations were identified in the genes agpsemzm and agpllzm and shown to cause reduced AGPase activity in specific tissues. The functioning of these two genes was necessary for the accumulation of normal starch levels in embryo and leaf, respectively. Remnant starch was observed in both instances, indicating that additional genes encode AGPase large and small subunits in embryo and leaf. Endosperm starch was decreased by approximately 7% in agpsemzm- or agpllzm- mutants, demonstrating that plastidial AGPase activity contributes to starch production in this tissue even when the major cytosolic activity is present.

Plant ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase (AGPase) catalyzes the production of ADP-glucose (ADPGlc) and inorganic pyrophosphate (PPi) from Glc-1-P and ATP, thus generating the nucleotide sugar used by starch synthases to incorporate glucosyl units into starch. ADPGlc formation is an important metabolic control point and thus has been a genetic engineering target for crop improvement. Altering AGPase activity by transgenic means resulted in elevated yields in several starch-producing crops, including rice (Oryza sativa), maize (Zea mays), wheat (Triticum aestivum), and potato (Solanum tuberosum), although the precise nature of the metabolic and developmental changes that result remains to be elucidated (Stark et al., 1992; Greene and Hannah, 1998; Smidansky et al., 2002, 2003, 2007; Hannah et al., 2012).

AGPase localization appears to be strictly plastidial in most plant tissues, whereas in cereal endosperms, the majority of the enzyme is cytosolic and a minor form resides within amyloplasts (for review, see Comparot-Moss and Denyer, 2009; Hannah and Greene, 2009; Geigenberger, 2011). Such an arrangement necessitates distinct modes of regulation and metabolic control of starch biosynthesis compared with other plants, including transport of ADPGlc and Glc phosphate (Glc-1-P and/or Glc-6-P) from the cytosol into the amyloplast. Subcellular fractionation revealed that 85% to 95% of total AGPase activity is cytosolic in endosperms of rice, maize, and barley (Hordeum vulgare) at mid development and in wheat early in development (Denyer et al., 1996; Thorbjornsen et al., 1996; Shannon et al., 1998; Sikka et al., 2001; Tetlow et al., 2003; Rösti et al., 2006). AGPase distribution between cellular compartments changes over development in wheat endosperm, where at later stages up to 40% was plastidial (Tetlow et al., 2003). Null mutations in genes encoding cytosolic AGPase are known in maize, barley, and rice, and these all cause reduction in total endosperm starch in the range of 20% to 70% of normal, but not complete deficiency (Tester et al., 1993; Johnson et al., 2003; Rösti et al., 2006; Lee et al., 2007). Total endosperm AGPase activity is reduced in such mutants, although approximately 12% to 25% remains (Dickinson and Preiss, 1969; Johnson et al., 2003). These observations indicate that separate genes have been maintained in the Poaceae to encode both cytosolic and plastidial AGPases and suggest that both forms contribute to the production of endosperm starch. Mutations that affect plastidial AGPase in endosperm have not been described, however, so whether this form of the enzyme contributes to starch accumulation in nonmutant tissue remains to be determined.

Biochemical analyses have sought to identify the cytosolic and plastidial forms of AGPase in endosperm and other tissues of cereals. The plant enzyme is an α2β2 heterotetramer of approximately 210 kD, comprising two structurally related polypeptides designated as the large subunit (LS) and the small subunit (SS; Morell et al., 1987; Lin et al., 1988; Okita et al., 1990; Preiss et al., 1990). Two genes encode AGPase SS proteins in barley, rice, and wheat, classified as type 1 and type 2 (Rösti and Denyer, 2007). Type 1 genes generate two different transcripts referred to as type 1a and type 1b (Thorbjornsen et al., 1996; Burton et al., 2002; Ohdan et al., 2005). Type 1a transcripts encode a cytosolic protein that was directly identified as the extraplastidial AGPase SS from endosperm (Burton et al., 2002; Johnson et al., 2003; Lee et al., 2007). Type 1b transcript accumulates in endosperm and is predicted to encode a plastidial protein, but the AGPase SS purified from wheat or barley amyloplasts did not match the amino acid sequence predicted by this mRNA (Burton et al., 2002; Johnson et al., 2003). Rather, plastidial AGPase SS from barley endosperm matches the sequence predicted by the type 2 gene (Johnson et al., 2003). Type 1b transcripts are also present in leaf and embryo. Mutations of the barley or rice type 1 gene cause major reductions in leaf enzyme activity, thus identifying one of the transcripts encoding leaf AGPase SS as type 1b (Rösti et al., 2006; Lee et al., 2007). However, loss of type 1b transcript in barley embryo did not affect total AGPase activity, even though the mRNA is highly abundant (Rösti et al., 2006). A minor amount of type 2 transcript was also present in barley embryo, and presumably this specifies AGPase SS in this tissue.

Less information is available about the identities of the plastidial AGPase LS in cereals. Mutational analyses have identified the genes that encode the AGPase LS in endosperm cytosol of maize (Bae et al., 1990) and rice (Lee et al., 2007). Three additional genes encoding plastidial AGPase LS exist in rice and maize (Giroux and Hannah, 1994; Giroux et al., 1995; Lee et al., 2007; Yan et al., 2009; Huang et al., 2010), but the tissue-specific functions of this gene family have not been comprehensively established.

Functional analysis of endosperm plastidial AGPase will benefit from mutations that eliminate each subunit expressed in the tissue. Classical mutations at the shrunken2 (sh2) and brittle2 (bt2) loci led to the identification and cloning of the genes encoding cytosolic AGPase LS and SS, respectively (Bae et al., 1990; Bhave et al., 1990). The type 1 gene bt2 generates two transcripts (Rösti and Denyer, 2007), referred to as BT2a and BT2b. A complementary DNA (cDNA) from a type 2 gene encoding AGPase SS, termed agpsemzm (formerly referred to as agp2), was cloned from embryo tissue (Giroux and Hannah, 1994; Giroux et al., 1995). In addition, a third gene encoding AGPase SS, termed agpslzm (formerly referred to as L2), is present in maize owing to a duplication of the ancestral type 1 gene (Prioul et al., 1994; Hannah et al., 2001; Rösti and Denyer, 2007; Cossegal et al., 2008). Maize differs from other cereals in which type 1a and 1b transcripts from the same gene specify AGPase SS in endosperm cytosol and leaf plastids, respectively. In maize, the type 1a transcript from bt2 operates in endosperm, whereas a different gene, namely agpslzm, generates a separate type 1b transcript that specifies AGPase SS in leaf (Rösti and Denyer, 2007; Slewinski et al., 2008).

Given this complexity, the genetic specification of AGPase in maize endosperm beyond the cytosolic form encoded by sh2 and bt2 is not known. Three such transcripts encoding AGPase SS, namely BT2b, AGPSLZM, and AGPSEMZM, have been detected in maize endosperm and could specify plastidial proteins (Giroux and Hannah, 1994; Rösti and Denyer, 2007; Cossegal et al., 2008). Two transcripts other than SH2 that encode AGPase LS, namely AGPLEMZM (formerly referred to as agp1; Giroux and Hannah, 1994; Giroux et al., 1995) and AGPLLZM (for AGPase large subunit from a leaf cDNA of Zea mays; previously referred to as Zmagpl1 or AGPL4; Yan et al., 2009; Huang et al., 2010), are present in maize endosperm. To better clarify the genetic specification of AGPase in maize endosperm and other tissues, this study characterized the expression levels, enzymatic activities, and subcellular localizations of this suite of AGPase SS and LS proteins. Null mutations were identified in apgsemzm and agpllzm and used to test gene function in endosperm, embryo, and leaf. The genes apgsemzm and agpllzm were each required for the production of approximately 7% of the total endosperm starch, demonstrating that nonmutant tissue relies on contributions from both plastidial and cytosolic AGPase. The genetic analyses also showed that multiple genes encode AGPase subunits in leaf and embryo, in addition to endosperm.

RESULTS

Maize AGPase Gene List and Nomenclature

Maize AGPase genes have been designated in previous literature using various conventions. This study uses the terminology of Hannah et al. (2001), in which the SS or LS is designated as “agps” or “agpl,” respectively, and the tissue from which the cDNA was originally cloned is indicated as “l” for leaf or “em” for embryo, with “zm” appended to indicate the species as maize. As an example, agpsemzm indicates a gene encoding a transcript isolated from maize embryo that codes for AGPase SS. Although the convention refers to the tissue from which the transcript was first isolated, it does not imply that gene expression or function is necessarily specific to that tissue. Exceptions to the convention are sh2 and bt2, which were defined by classical mutations (Tsai and Nelson, 1966; Bae et al., 1990; Bhave et al., 1990), and AGPL3, whose sequence was originally obtained through a bioinformatic approach (Yan et al., 2009). Table I specifies by gene model the seven loci encoding AGPase LS or SS that have been identified in the maize reference genome of inbred line B73 (www.maizegdb.org).

Table I. Maize genes encoding AGPase LS or SS.

| Gene Name | Previous Designations | Subunit Encoded | Gene Modela | Sequence Referencesb,c | Mutation Referencesb,c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| sh2 | LS | GRMZM2G429899 | 1, 2 | 11, 12 | |

| bt2 | SS | GRMZM2G068506 | 3 | 13, 14 | |

| agplemzm | agp1 | LS | GRMZM2G027955 | 4, 5 | None |

| agpsemzm | agp2 | SS | GRMZM2G106213 | 4, 6 | This study |

| agpllzm | ZmagpL1, AGPL4 | LS | GRMZM2G391936 | 7, 8, 9 | This study |

| agpslzm | L2 | SS | GRMZM2G163437 | 3, 10 | 15 |

| AGPL3 | LS | GRMZM2G144002 | 8 | None |

Gene models at www.maizegdb.org indicate chromosome coordinates and identify corresponding cDNA and EST clones. bListed references describe the first identification of the gene by cDNA cloning and nucleotide sequence determination and the original description of mutations in that gene, if available. cReferences are as follows: 1, Bhave et al. (1990); 2, Shaw and Hannah (1992); 3, Hannah et al. (2001); 4, Giroux and Hannah (1994); 5, Giroux et al. (1995); 6, Hannah et al. (2001), GenBank identifier no. AY032604; 7, Rosti and Denyer (2007), GenBank identifier no. DQ406819; 8, Yan et al. (2009); 9, Huang et al. (2010); 10, Prioul et al. (1994); 11, Mains (1949); 12, Tsai and Nelson (1966); 13, Teas and Teas (1953); 14, Bae et al. (1990); 15, Slewinski et al. (2008).

AGPase Transcript Abundance

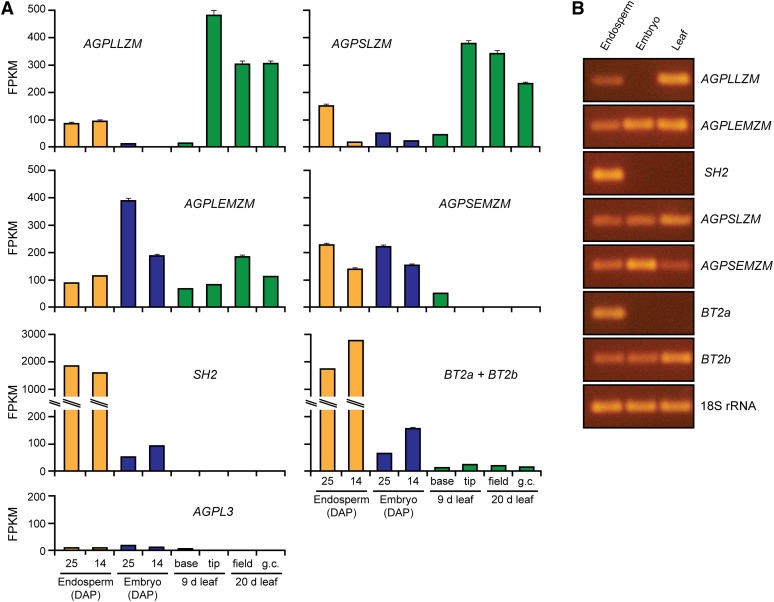

Transcript abundance in specific tissues was surveyed comprehensively to identify all candidate genes that potentially could encode plastid-localized AGPase LS and SS. Publicly available whole-transcriptome RNA sequencing data (RNA-Seq; Li et al., 2010; Davidson et al., 2011; Waters et al., 2011) provided a quantitative measure of the steady-state levels of specific mRNAs in endosperm as well as embryo and leaf (www.qTeller.com; Fig. 1A). Transcripts from agpllzm, agpslzm, agplemzm, and agpsemzm were all detected in endosperm in addition to the highly abundant SH2 and BT2 mRNAs. Embryo contained AGPLEMZM, AGPSEMZM, and AGPSLZM mRNAs, whereas little or no AGPLLZM mRNA was detected in that tissue by RNA-Seq at either 14 or 25 d after pollination (DAP). Mature leaf tissue contained AGPLLZM, AGPSLZM, and AGPLEMZM mRNAs but lacked AGPSEMZM transcript. The latter mRNA was present, however, in immature leaf tissue at the base of the blade. SH2 and BT2 mRNAs were detected by RNA-Seq in developing embryo, and a low level of transcript from the bt2 locus was also observed in leaf. For the bt2 locus, the RNA-Seq technique as applied in the surveyed data sets does not distinguish between the BT2a and BT2b mRNAs, so the data shown in Figure 1A are the sum of those two transcripts. Finally, the levels of AGPL3 transcript in endosperm, embryo, and leaf were very low compared with any of the others, and based on this criterion, that gene was not examined further in this study.

Figure 1.

Transcript abundance. A, RNA-Seq. Whole-transcriptome sequence data sets from Li et al. (2010; immature tissue from the base of 9-d seedling leaves and mature tissue from the tip of 9-d seedling leaves), Davidson et al. (2011; 25-DAP embryo, 25-DAP endosperm, field-grown 20-d whole seedling leaf, and growth chamber [g.c.]-grown 20-d whole seedling leaf), and Waters et al. (2011; 14-DAP embryo and 14 DAP endosperm) were analyzed for specific transcript abundance using the qTeller algorithm (www.qTeller.com). FPKM, Fragments per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads. Error bars indicate the 95% confidence interval for transcript abundance calculations in each data set. If the error bars are not shown, they are too small to be discerned at this scale. B, RT-PCR. mRNA from 20-DAP embryos, 20-DAP endosperm, or 30-d whole seedling leaves was amplified using primers specific for the indicated transcript or 18S ribosomal RNA (rRNA). Amplifications used 30 PCR cycles, except for AGPSLZM, which used 35 cycles. Amplified fragments were separated by agarose gel electrophoresis and visualized by ethidium bromide staining. [See online article for color version of this figure.]

To confirm the RNA-Seq results, reverse transcription (RT)-PCR was used to test for the presence of particular mRNAs in endosperm or embryo from kernels harvested 20 DAP or whole seedling leaf. Primers were designed to specifically amplify each mRNA, including separate sets to individually assay the BT2a and BT2b transcripts from the bt2 locus (Supplemental Table S1). The sequences of the amplified fragments were determined to confirm that each pair of oligonucleotides specifically amplified the expected transcript (data not shown). The RT-PCR data collected here (Fig. 1B), together with previously published RNA gel-blot and RT-PCR analyses of some of these gene/tissue combinations (Giroux and Hannah, 1994; Rösti and Denyer, 2007; Cossegal et al., 2008; Yan et al., 2009; Huang et al., 2010), agree closely with the RNA-Seq results. AGPLLZM, AGPLEMZM, and SH2 mRNAs encoding AGPase LS and AGPSLZM, AGPSEMZM, BT2a, and BT2b transcripts encoding AGPase SS were all detected in endosperm by RT-PCR. The presence of multiple transcripts in leaf and embryo, as well as the absence of AGPLLZM from embryo and the low level of AGPSEMZM in leaves, were also confirmed by the RT-PCR results. The RT-PCR and RNA-Seq results were discrepant regarding the specificity of SH2 and BT2a mRNA accumulation. These transcripts appeared to be exclusive to endosperm based on the RT-PCR data but were detected in embryo and leaf by RNA-Seq (Fig. 1). Contamination of the embryo sample analyzed by RNA-Seq with endosperm tissue could explain this discrepancy, and in the case of bt2, the inability of RNA-Seq to distinguish between BT2a and BT2b might, in part, be responsible.

Taken together, these data indicate that agpsemzm, agplemzm, agpslzm, agpllzm, and one of the two transcripts from bt2 must all be considered as potential sources of plastidial AGPase in endosperm. mRNA measurements also revealed that multiple AGPase genes are transcribed in embryo and leaf and, thus, potentially could specify enzyme activity in those tissues. Proteomic data confirm that, in seedling leaves, multiple genes specify both AGPase SS and LS, from direct observation of the polypeptide products of agpllzm, agpslzm, and agplemzm (Majeran et al., 2010). Proteomic analysis also identified the agpslzm product in embryo (Huang et al., 2012). Finally, it should be noted that lack of transcript accumulation does not, by itself, rule out activity of that gene in endosperm, embryo, or leaf, because tissue was not sampled throughout the diurnal cycle or the progression of seed development; thus, the analyses may have missed transcripts that are present only in a limited time frame.

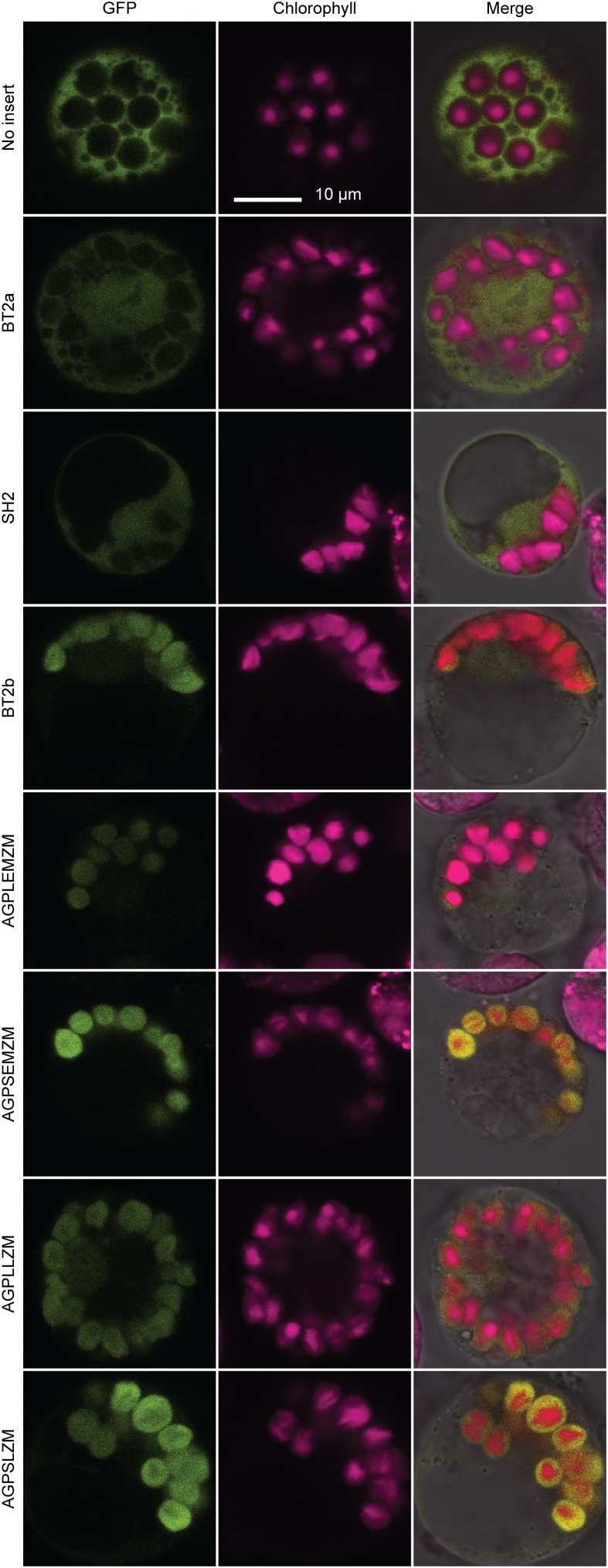

Plastidial Localization of AGPase LS and SS

The ChloroP algorithm (Emanuelsson et al., 1999) predicted plastidial localization of AGPLLZM, AGPSLZM, AGPLEMZM, AGPSEMZM, and BT2b. These predictions were tested by transient expression of fusion proteins comprising the N-terminal 98 or 99 amino acids from each AGPase subunit and GFP at the C terminus (Chiu et al., 1996). Recombinant genes encoding such fusion proteins were expressed from the cauliflower mosaic virus 35S-maize C4, pyruvate phosphate dikinase gene hybrid promoter (Sheen, 1993) in protoplasts prepared from etiolated maize seedling leaves. Transformed cells were observed by confocal fluorescence microscopy to detect the subcellular location of GFP and to identify the positions of chloroplasts by chlorophyll autofluorescence (Fig. 2). Expressing GFP without any fusion protein portion at its N terminus resulted in diffuse signal throughout the cell but not in the chloroplast regions, thus marking a cytosolic protein. Maize BT2a had been shown previously to be located in the cytosol both by biochemical fractionation (Denyer et al., 1996) and fluorescence microscopy (Choi et al., 2001), and that result was repeated here to confirm the accuracy of the protoplast method. As expected, SH2-GFP also exhibited an exclusively cytosolic localization (Fig. 2). The remainder of the maize AGPase subunits tested all colocalized with chlorophyll autofluorescence and appeared to be lacking in the cytosol, indicating import into plastids. Confirmation of this result for AGPLLZM and AGPSLZM is provided by a proteomics study in which both proteins were identified directly in isolated maize leaf plastids (Majeran et al., 2005). Further support comes from a proteomics analysis that identified the orthologs of AGPSLZM and AGPLEMZM in wheat amyloplasts (Balmer et al., 2006) and by fluorescence localization of GFP fusions to the AGPase SS and LS orthologs of rice (Lee et al., 2007).

Figure 2.

Subcellular localization of AGPase LS-GFP and AGPase SS-GFP fusion proteins in maize leaf protoplasts. Fusions proteins comprising the first 98 or 99 amino acids of the full-length sequence of the indicated protein at the N terminus and GFP at the C terminus were expressed in transiently transformed maize leaf protoplasts. Confocal fluorescence microscopy revealed the locations of GFP as green color and chlorophyll as magenta color. Each set of three images shows the same cell. All images were recorded at the same sensitivity and scale.

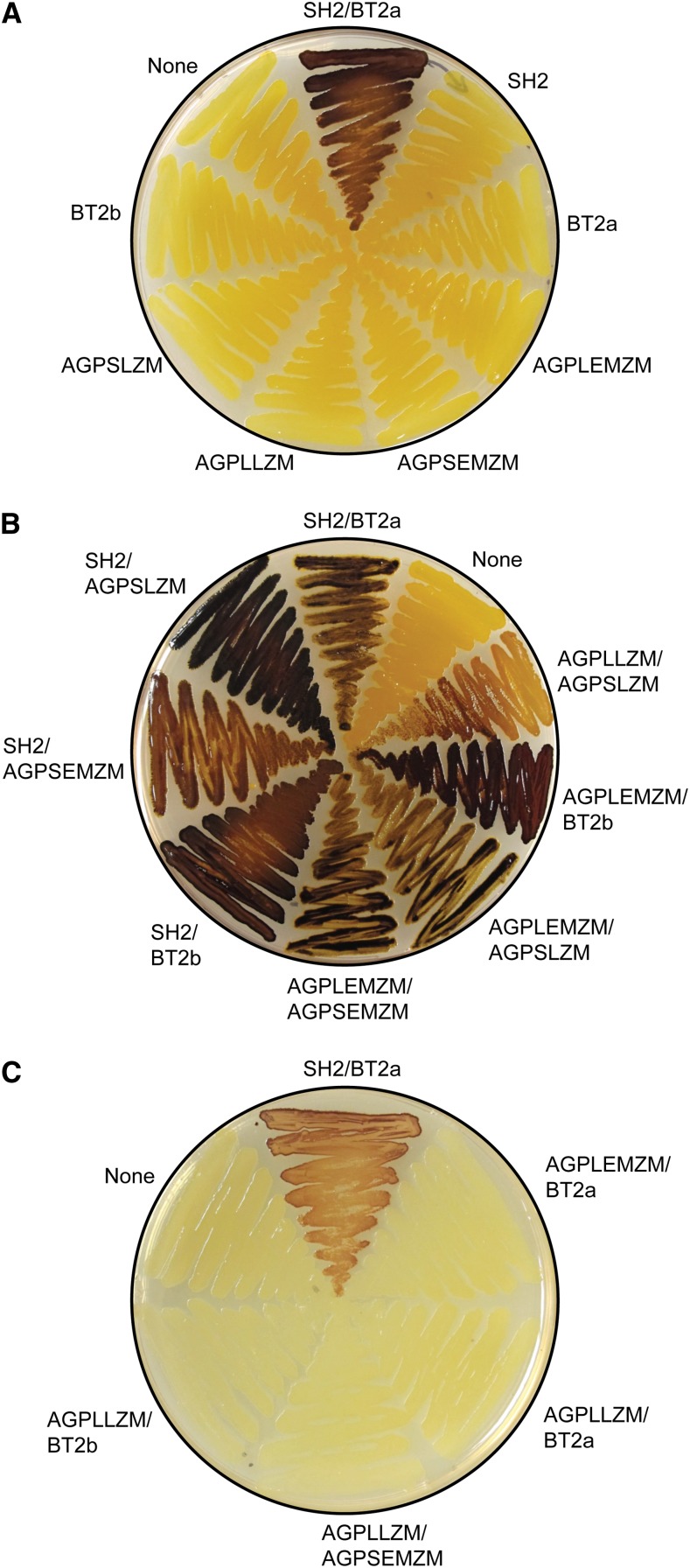

Expression and in Vivo Function of Maize AGPase Subunits in Escherichia coli

The presence of multiple transcripts encoding plastid-targeted AGPase SS and LS in maize tissues raises the possibility that various combinations of LS and SS could constitute enzyme activity within amyloplasts or chloroplasts. To test this hypothesis, AGPase LS and SS were expressed pairwise in E. coli. The coding regions of seven maize AGPase transcripts were synthesized with codon usage optimized for E. coli, and these DNA fragments were amplified by PCR and cloned into expression vectors. In some instances, the N terminus of the expressed protein was adjusted by adding or removing codons in the upstream amplification primer. Supplemental Figure S1 indicates the specific residues that constituted the AGPase subunits tested and the position of the N terminus of each protein relative to the predicted transit peptide cleavage site. Two different expression vectors with compatible replication origins and selectable markers were used for coexpression of one AGPase SS and one AGPase LS in the same cells. The E. coli host strain AC70R1-504 carries a glycogen accumulation C– (glgC–) mutation and thus lacks endogenous AGPase, so the activity of the plant genes could be detected by the restoration of glycogen accumulation, as revealed by staining with iodine vapor (Iglesias et al., 1993; Giroux et al., 1996; Greene and Hannah, 1998).

The results are shown in Figure 3 and summarized in Table II. In all instances, multiple colonies of each AGPase SS/LS combination were tested, with consistent results between the biological replicates. None of the AGPase subunits expressed alone restored glycogen accumulation, whereas coexpression of SH2 and BT2a yielded dark iodine vapor staining, as observed previously (Greene and Hannah, 1998; Fig. 3A). The following combinations of maize proteins yielded a dark iodine stain indicating functional AGPase: AGPLLZM/AGPSLZM, AGPLEMZM/BT2b, AGPLEMZM/AGPSLZM, AGPLEMZM/AGPSEMZM, SH2/BT2b, SH2/AGPSEMZM, and SH2/AGPSLZM (Fig. 3B). Combinations that failed to yield positive iodine staining were AGPLEMZM/BT2A, AGPLLZM/BT2a, AGPLLZM/AGPSEMZM, and AGPLLZM/BT2b (Fig. 3C). The negative results cannot be explained by the lack of expression, because all subunits tested were functional in at least one combination. The results demonstrate that AGPLLZM, AGPSLZM, AGPLEMZM, AGPSEMZM, and BT2b all encode AGPase subunits capable of functioning to generate active enzyme.

Figure 3.

Maize AGPase function in E. coli. The host strain lacking endogenous AGPase was transformed with one plasmid to express the indicated individual subunit or cotransformed with two plasmids to generate the indicated AGPase SS/LS pair. Cell patches were spread from freshly transformed single colonies, grown overnight at 37°C, and then stained by exposure to iodine vapor. A, Individual subunits. B, Active subunit pair combinations. C, Inactive subunit pair combinations. [See online article for color version of this figure.]

Table II. Activity of AGPase SS/LS pairs in E. coli.

Activity was judged by positive iodine stain as shown in Figure 3. Numbers in parentheses indicate the codons of each full-length coding sequence that were expressed in E. coli.

Some of the AGPase subunits were capable of functioning with multiple partners, whereas others were active only in specific combinations (Table II). For example, SH2 and AGPSLZM both generated enzyme activity in combination with all of the partner subunits tested, in contrast to BT2a and AGPLLZM, which functioned only when coexpressed with one particular partner. BT2b, AGPSEMZM, and AGPLEMZM were intermediate in the sense that each of them restored glycogen accumulation when combined with more than one partner but did not do so with every partner tested.

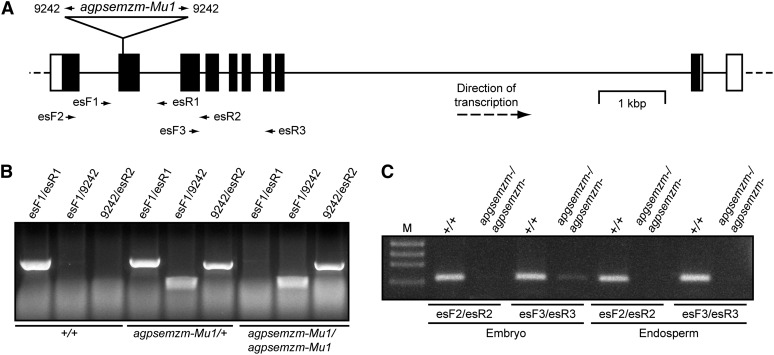

Mutations of agpsemzm and agpllzm and Effects on AGPase Activity

AGPase gene functions were investigated using mutations in agpsemzm and agpllzm. The allele agpsemzm-Mutator1 (Mu1) was present in the UniformMu maize population (McCarty et al., 2005; Settles et al., 2007). UniformMu lines are isogenic in the W22-ACR inbred background and contain sequence-indexed insertions of Mu transposable elements. Seeds from a self-pollinated ear containing agpsemzm-Mu1 were planted, and homozygous progeny were identified by PCR-based genotype determination using leaf DNA (Fig. 4, A and B). Sequencing of the PCR products verified the Mu insertion site in exon 2. The effect of the insertion on gene activity was tested by RT-PCR amplification of AGPSEMZM mRNA in embryo or endosperm of wild-type and homozygous agpsemzm-Mu1 kernels harvested 20 DAP. Gene-specific primers that span the Mu insertion site failed to detect AGPSEMZM mRNA in mutant embryo or endosperm but readily detected the transcript in wild-type tissues (Fig. 4C). A primer set spanning a region of the mRNA downstream of the transposon insertion detected a trace amount of transcript in mutant embryo but not in endosperm. The remnant mRNA in homozygous mutant embryo presumably results from transcription initiation within the Mu transposon and, thus, is not expected to encode a functional polypeptide.

Figure 4.

Characterization of the agpsemzm locus and the null allele agpsemzm-Mu1. A, Gene map. The region shown corresponds to gene model GRMZM2G106213 (www.maizegdb.org). White boxes represent 5′ or 3′ untranslated region exons, black boxes indicate coding region exons, solid lines indicate introns, and dotted lines indicate genomic sequence adjacent to the transcribed region. The map is drawn to scale. The position of the Mu transposon insertion in agpsemzm-Mu1 is indicated. Small arrows indicate the positions of primer sequences used for genotype determination or transcript analysis. B, Genotype determination. The indicated primer pairs shown in A were used for PCR amplification of seedling genomic DNA from progeny of a self-pollinated agpsemzm-Mu1/+ heterozygote. C, Transcript analysis. mRNA from the indicated tissues of nonmutant or agpsemzm-Mu1 homozygous mutant plants was amplified by RT-PCR using the indicated primer pairs. “M” indicates DNA standards of known molecular mass.

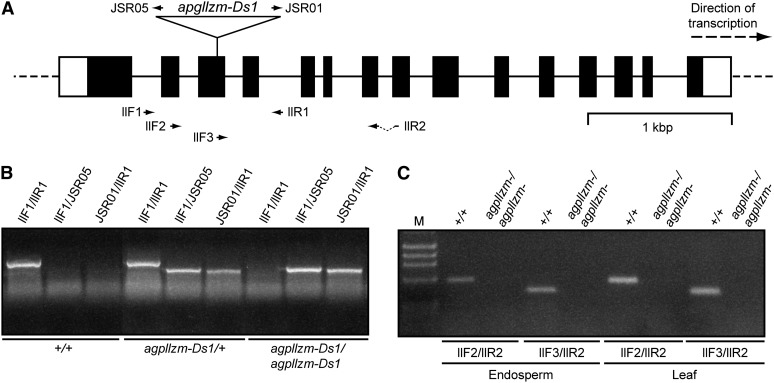

The mutant allele agpllzm-Ds1 (for Dissociation1) was isolated from a sequence-indexed population of maize plants containing randomly inserted Ds transposable elements in the inbred background designated here as W22D (Ahern et al., 2009; Vollbrecht et al., 2010). Homozygous mutant plants were identified by PCR amplification of leaf genomic DNA, and sequences of the products confirmed the insertion site within exon 3 (Fig. 5, A and B). RT-PCR using primer sets either spanning the Ds insertion or downstream of that location detected AGPLLZM transcript in wild-type leaf and endosperm but failed to generate any product in either mutant tissue (Fig. 5C). Thus, RT-PCR data indicate that both agpsemzm-Mu1 and agpllzm-Ds1 are null mutations.

Figure 5.

Characterization of the agpllzm locus and the null allele agpllzm-Ds1. A, Gene map. The region shown corresponds to gene model GRMZM2G391936 (www.maizegdb.org). Notations are as for Figure 4. The position of the Ds transposon insertion in agpllzm-Ds1 is indicated. B, Genotype determination. The indicated primer pairs shown in A were used for PCR amplification of seedling genomic DNA from progeny of a self-pollinated agpllzm-Ds1/+ heterozygote. C, Transcript detection. mRNA from the indicated tissues of wild-type or agpllzm-Ds1 homozygous mutant plants was amplified by RT-PCR using the indicated primer pairs. “M” indicates DNA standards of known molecular mass.

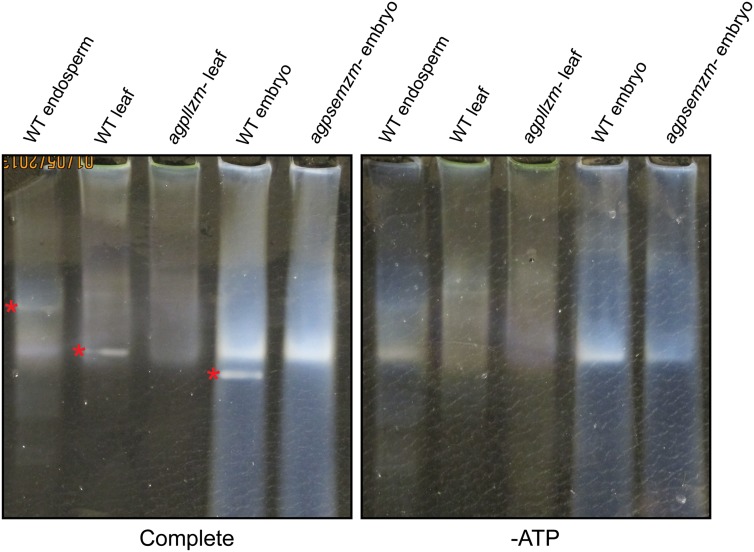

In-gel enzyme activity assays (i.e. zymograms) tested whether AGPase activities were affected by the mutations. Proteins in total soluble extracts from seedling leaf harvested 30 d after emergence, 20-DAP embryo, or 20-DAP endosperm were separated by native-PAGE. The gels were then incubated in the presence of ATP, Glc-1-P, and the positive regulator 3-phosphoglyceric acid (3-PGA), so that bands of AGPase activity would produce localized regions of high PPi concentration. Divalent cations in the incubation mixture caused PPi to precipitate, producing visible bands. Control assays in which ATP or Glc-1-P was omitted identified precipitate bands that arose from an activity(s) other than AGPase. Nonmutant endosperm, embryo, and leaf extracts all generated a single ATP-dependent activity, each with distinct mobility in native-PAGE (Fig. 6). These precipitate bands also required Glc-1-P in the incubation mixture (data not shown). The AGPase activity band from embryo extracts was not observed in agpsemzm-Mu1 homozygous mutants, and the AGPase band in leaf extracts was absent from agpllzm-Ds1 homozygotes. These data support the conclusion that agpsemzm and agpllzm both encode polypeptides that are capable of forming active AGPase enzymes in vivo.

Figure 6.

AGPase activity in zymograms. Soluble extracts from endosperm or embryos from kernels harvested 20 DAP, or from 30-d seedling leaves, were fractionated by native-PAGE. Gels were incubated in reaction buffer including ATP and Glc-1-P (Complete) in the presence of divalent cations or in the same buffer lacking ATP (−ATP) and then photographed on a black background. White bands indicate regions of precipitated material. Asterisks indicate precipitate bands that require ATP and thus indicate AGPase activity. Homozygous mutants of the indicated genotype were compared with nonmutant wild-type standards (WT). [See online article for color version of this figure.]

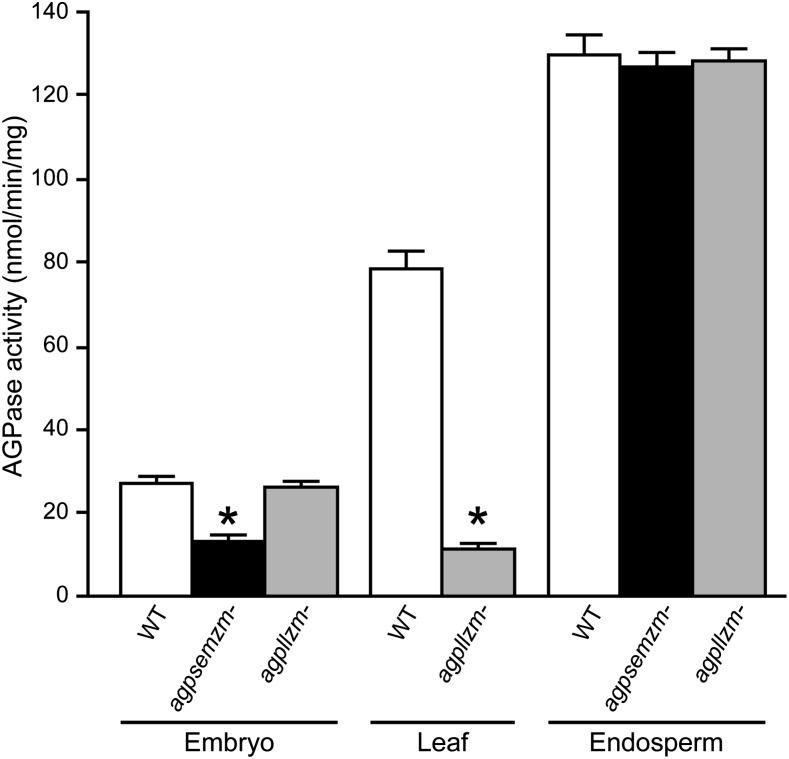

Total AGPase in soluble extracts was quantified by enzymatic assay to provide further evidence that particular subunits contribute to the activity in a given tissue (Fig. 7). Total activity in homozygous agpsemzm-Mu1 embryos harvested 20 DAP was reduced by approximately 50% compared with the nonmutant standard. Embryo AGPase activity in total extracts was not affected by the agpllzm-Ds1 mutation, as expected from the low level or absence of AGPLLZM mRNA in that tissue (Fig. 1). Leaf extracts from agpllzm-Ds1 were strongly reduced in total AGPase activity, retaining only approximately 15% of the nonmutant value. The total AGPase activity in 20-DAP endosperm extracts was not affected by either agpsemzm-Mu1 or agpllzm-Ds1. These results confirm that agpllzm and agpsemzm both encode proteins that function physiologically to generate AGPase activity and also imply that additional AGPase LS and SS proteins function in the leaf and embryo, respectively.

Figure 7.

AGPase activity in total soluble extracts. Soluble extracts of the indicated homozygous mutants and the isogenic nonmutant wild-type reference strain (WT) were assayed for AGPase activity in the Glc-1-P-forming direction. Values are means ± sd from three biological replicates each assayed twice. Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences from the nonmutant standard (P < 0.001).

Effects of AGPase Mutations on Starch Content

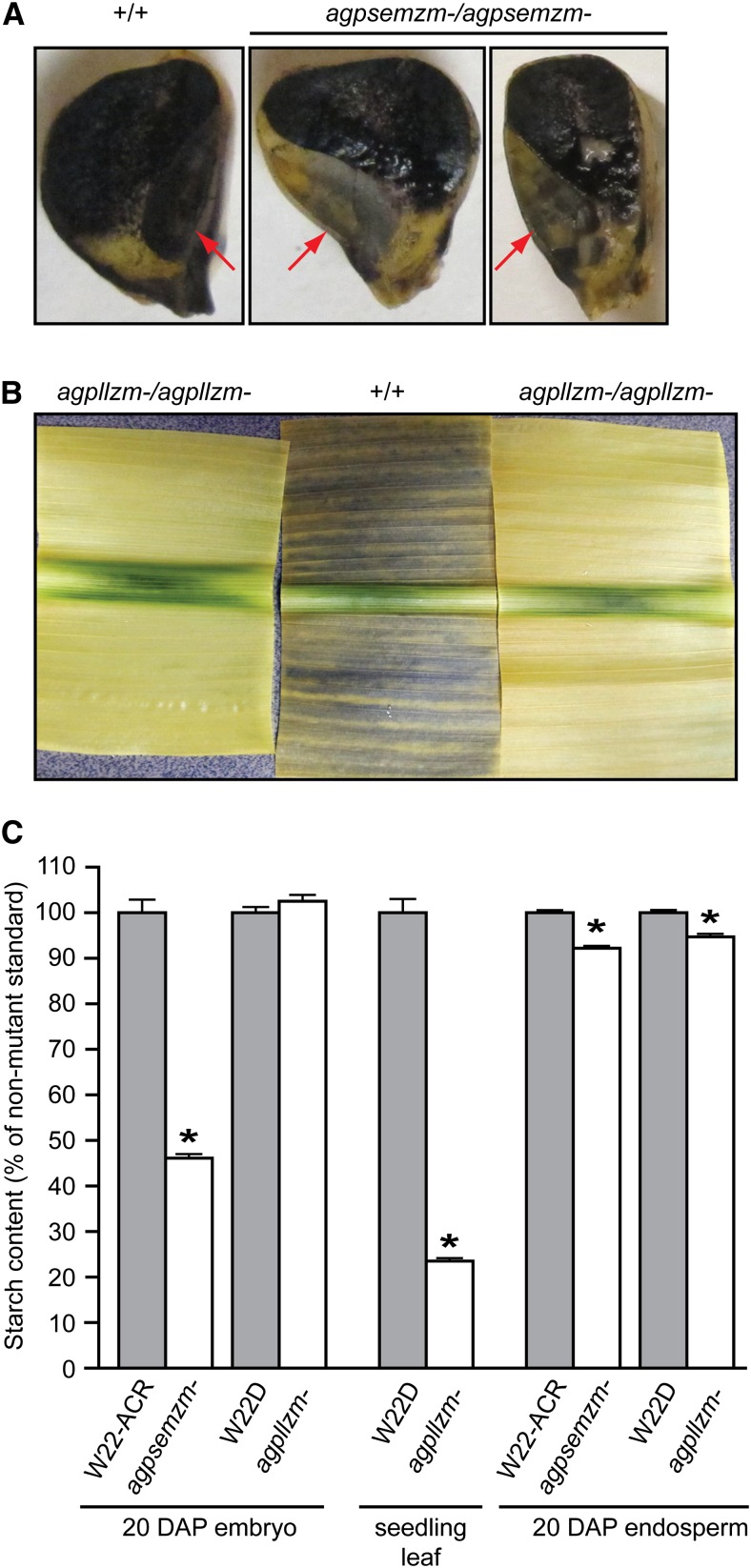

Potential effects of eliminating particular AGPase subunits on starch accumulation were tested by tissue staining with iodine/potassium iodide (I2/KI) solution. Nonmutant embryo and endosperm in kernels harvested 20 DAP both stained darkly; however, the embryo stain was markedly less intense in agpsemzm-Mu1 homozygous mutant kernels (Fig. 8A). The agpllzm-Ds1 mutation did not affect iodine staining of either endosperm or embryo (data not shown). Seedling leaves harvested at the end of the light period were tested similarly after decolorization by boiling in ethanol. Nonmutant tissue exhibited a dark stain, whereas agpllzm-Ds1 homozygous mutant leaves did not stain appreciably with iodine (Fig. 8B). Homozygous agpsemzm-Mu1 mutant leaves stained darkly with iodine and were not distinguishable from the nonmutant standard in this assay (data not shown).

Figure 8.

Starch content. A, Embryo and endosperm staining. Kernels of the indicated genotype were harvested 20 DAP, sliced longitudinally, submerged in I2/KI solution, and then destained in water. Red arrows indicate the embryo. B, Leaf staining. Seedling leaves were decolorized by boiling in ethanol, submerged in I2/KI solution, and then destained in water. C, Starch quantification in homozygous tissues. Values are mean percentages of the nonmutant standard starch content ± se. Absolute values were 72.3 mg g−1 dry weight for W22-ACR embryos, 71.3 mg g−1 dry weight for W22D embryos, 8.57 mg g−1 fresh weight for W22D leaves, 784 mg g−1 dry weight for W22-ACR endosperm, and 677 mg g−1 dry weight for W22D endosperm. Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences from the nonmutant standard. Biological replicates and statistical significance values are described in the text.

Starch contents in leaf, embryo, and endosperm were quantified in homozygous mutants to test further for requirements of agpllzm and agpsemzm function (Fig. 8C). The starch content of agpllzm-Ds1 homozygous mutant leaves was approximately 23% of the amount in the isogenic nonmutant inbred. The se among biological replicate measurements of four individuals of each genotype was low (Fig. 8C), and the difference between mutant and nonmutant was highly statistically significant (P < 0.0001). Embryo starch content was quantified in separate pools of 20 embryos from at least three individual ears of self-pollinated homozygous plants of each genotype. The agpsemzm-Mu1 mutation resulted in a decrease in embryo starch to approximately 46% of the nonmutant level, whereas agpllzm-Ds1 did not affect the starch content in embryo. Again, the se among biological replicate pools was low (Fig. 8C), and the difference between the mutants and the nonmutant standard was statistically significant (P < 0.0004).

The potential effects of agpllzm-Ds1 or agpsemzm-Mu1 on endosperm starch content in homozygous mutants were also tested (Fig. 8C). Endosperm from 12 single kernels harvested 20 DAP, from three different homozygous parent plants, was analyzed individually for both mutants and the isogenic nonmutant standards. Homozygous agpllzm-Ds1 mutant endosperm showed a small but statistically significant reduction (P = 0.016) of approximately 5% from the nonmutant starch content. Similarly, agpsemzm-Mu1 homozygous mutant endosperm contained approximately 8% less starch than the nonmutant standard, with the differences exhibiting high statistical significance (P < 0.0001).

Such differences in endosperm starch content potentially could have arisen owing to a biochemical defect within endosperm tissue and/or as a result of the AGPase lesion in the parent plant that might affect photosynthate supply to the seed or some other aspect of metabolism. To distinguish between these possibilities, heterozygous agpsemzm-Mu1/+ or agpllzm-Ds1/+ plants were self-pollinated, and endosperm starch content in individual sibling kernels on the same ear was quantified. These populations contain homozygous mutants at a frequency of approximately 25%, with the remaining kernels either heterozygous or homozygous for the nonmutant allele. Potential maternal differences are not a factor in this instance, because all individuals are progeny of the same parent. Either the embryo or a portion of the endosperm was used to extract genomic DNA, and the genotype of that individual was determined by PCR analysis as in Figures 4 and 5. Endosperm starch was then quantified, and the levels were compared between homozygous mutants as a class and pooled homozygous nonmutants and heterozygotes as the reference (Table III). Homozygous agpsemzm-Mu1 endosperm from kernels harvested 20 DAP contained approximately 7% less starch than the nonmutant siblings, in close agreement with the results from the comparison between kernels of homozygous mutant and nonmutant plants. Statistical significance was again strongly indicated (P < 0.0001). Similar results were also observed in agpsemzm-Mu1 homozygous endosperm from mature kernels. Endosperm from mature sibling kernels segregating for agpllzm-Ds1 showed a 7% starch content reduction in homozygous mutants compared with the nonmutant pool, which was also statistically significant (P = 0.0004) and agreed closely with the results from kernels grown on separate homozygous plants.

Table III. Endosperm starch content in sibling kernels from the same ear.

Endosperms from individual kernels on an ear of self-pollinated heterozygous plants were compared. Values indicate means ± se for the indicated number of biological replicates. Nonmutant kernels include both homozygous wild-type and heterozygous individuals. P values indicate the results of two-tailed Student’s t tests between mutant and nonmutant endosperms on the same ear. n.d., Not determined.

| Genotype | Developmental Stage |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20 DAP |

Mature |

|||||

| mg g−1 dry wt | n | P | mg g−1 dry wt | n | P | |

| Nonmutant | 775 ± 31 | 37 | <0.0001 | 794 ± 5 | 12 | <0.0001 |

| agpsemzm-/agpsemzm- | 722 ± 9 | 11 | 734 ± 4 | 4 | ||

| Nonmutant | n.d. | 693 ± 7 | 12 | 0.0004 | ||

| agpllzm-/agpllzm- | n.d. | 643 ± 10 | 9 | |||

The minor differences in starch content between agpllzm-Ds1 and agpsemzm-Mu1 mutant endosperm were not reflected in other parameters of kernel yield. Protein content was estimated by determining total nitrogen atom abundance in single endosperms of mutant or isogenic nonmutant standard, with the result that significant differences between the mutant and the wild type were not detected (Table IV). The average weights of mature agpllzm-Ds1 homozygous mutant seeds and isogenic nonmutant seeds, determined from pools of 50 seeds from four separate ears of each genotype, were not significantly different (Table IV). The seed weight of mature homozygous agpsemzm-Mu1 mutants was measured on single kernels identified by PCR in segregating populations of self-pollinated heterozygotes and compared with homozygous nonmutant siblings from the same ear. Again, the mutant and wild-type seed weights were not significantly different (Table IV).

Table IV. Seed weight and protein content.

Values indicate means ± sd for the indicated number of biological replicates.

| Genotype | Seed Weight |

Endosperm Protein Content |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mg kernel−1 | n | P | % protein | n | P | |

| Nonmutant | 264 ± 12 | 19a | 0.62 | 12.8 ± 0.74 | 12b | 0.14 |

| agpsemzm-/agpsemzm- | 261 ± 14 | 10a | 13.2 ± 0.40 | 12b | ||

| Nonmutant | 193 ± 13 | 4c | 0.23 | 10.7 ± 0.55 | 12d | 0.12 |

| agpllzm-/agpllzm- | 180 ± 10 | 4c | 11.2 ± 1.00 | 11d | ||

Biological replicates are individual mature kernels from a single ear of a self-pollinated agpsemzm-Mu1/+ heterozygote. bBiological replicates are individual kernels harvested 20 DAP from a homozygous mutant or the isogenic nonmutant inbred. cBiological replicates are average seed weights calculated by measuring pools of 50 mature kernels from separate ears. dBiological replicates are individual mature kernels from a homozygous mutant or the isogenic nonmutant inbred.

DISCUSSION

This study provides clarification about which AGPase subunits function physiologically in maize endosperm, leaf, and embryo. Functional complementation of an E. coli AGPase mutation demonstrated that AGPLLZM, AGPLEMZM, AGPSLZM, AGPSEMZM, and BT2b all are capable of generating enzymatic activity when combined with at least one partner subunit, and transient expression of GFP fusion proteins showed that all five proteins are imported into plastids. Genetic analyses then proceeded to eliminate either AGPLLZM or AGPSEMZM and to test for effects on AGPase activity and net starch content in the various tissues. The conclusions for each tissue are as follows.

Embryo

AGPSEMZM provides a large portion of the AGPase SS in embryo plastids, and in addition, at least one other gene contributes to this function. About half of the AGPase enzyme activity is lost when AGPSEMZM is absent, and starch content is also decreased by about 50%, which implies that another AGPase SS must be present in embryo. Consistent with this conclusion, AGPSLZM was detected in maize embryos by proteomic analysis (Huang et al., 2012). The presence of BT2b transcript in embryo raises the possibility that it also may provide AGPase SS in that tissue, although the protein has not yet been detected.

By deduction, the agplemzm locus appears to be the major contributor of AGPase LS in embryo, although genetic analyses using agplemzm- mutations will be needed to confirm this conclusion. Neither AGPLLZM nor SH2 is likely to be present in embryos, because the corresponding transcripts were not detected by RNA gel-blot hybridization (Giroux and Hannah, 1994) or RT-PCR (Fig. 1B). This is consistent with the fact that the agpllzm- null mutation did not affect total embryo AGPase activity. A relatively small quantity of transcript from the uncharacterized gene agpl3 was detected in embryo by RNA-Seq (Fig. 1A), so this locus remains as a potential contributor to AGPase LS in this tissue. E. coli complementation showed that AGPLEMZM functions in combination with AGPSEMZM, AGPSLZM, or BT2b, consistent with the conclusion that AGPSEMZM and at least one other AGPase SS accounts for enzyme activity in embryos.

A discrepancy in these considerations is that the remnant AGPase activity in embryo extracts of agpsemzm-Mu1 mutants was not discerned by zymogram even though it was detected by quantitative assay. Possibly another band of AGPase activity is present on the zymogram but is masked by an ATP-independent precipitable compound on the same region of the native-PAGE gel. Another potential explanation is that some AGPase activities are not stable throughout the zymogram procedure.

Two additional considerations should be noted. First, the data described here pertain to a limited period of kernel development, with most detail obtained at 20 DAP, so the possibility remains that the constitution of AGPase subunits changes over the course of development. A second possibility consistent with the fact that multiple genes specify AGPase in embryo is that different AGPase SS polypeptides might function in the same enzyme complex (e.g. with α2βγ quaternary structure, where two copies of AGPLEMZM combine with one AGPSEMZM subunit and one AGPSLZM subunit). Further biochemical analyses will be necessary to test this possibility.

Leaf

AGPase LS appears to be provided by both agpllzm and agplemzm, and AGPase SS apparently is encoded by a single gene, namely agpslzm. AGPLLZM and AGPLEMZM mRNAs are both present in leaf, and loss of agpllzm function caused major reductions in both AGPase activity and starch accumulation. Remnant AGPase activity and starch content were both clearly detected in agpllzm-Ds1 mutants, however, indicating by deduction that AGPLEMZM is also active in leaf. BT2b likely does not contribute to leaf AGPase SS, because total AGPase activity was not reduced in bt2- mutants (Rösti and Denyer, 2007), and AGPSEMZM mRNA is not present in mature leaf tissue (Fig. 1A). The agpslzm gene, therefore, remains as the only candidate for the coding of AGPase SS in leaf, consistent with a relatively high level of AGPSLZM transcript. Furthermore, an agpslzm- null mutation caused a loss of AGPase activity detected by zymogram and resulted in the absence of iodine stain in leaves (Slewinski et al., 2008). Consistent with the conclusion that mature leaf AGPase is provided by AGPSLZM together with either AGPLLZM or AGPLEMZM, both of these AGPase SS/LS combinations were active in E. coli. Once again, the data are consistent with the possibility of active AGPase complexes with three different subunits, in this instance two different AGPase LS polypeptides combining with a single AGPase SS.

Again, there is a potential discrepancy between the genetic data and the AGPase zymogram, because remnant enzyme activity could not be discerned in leaf extracts of the agpllzm- homozygous mutant. Such an activity does exist, however, because approximately 15% of the total AGPase activity in leaf extracts remained when AGPLLZM was eliminated by mutation. A possible explanation, again, is that some forms of AGPase are unstable through the zymogram assay or that the sensitivity of the assay is insufficient. Also, it should be noted that potential changes in AGPase gene expression over the diurnal cycle have not been ruled out.

Endosperm

The fact that a large majority of AGPase in cereal endosperm is located in the cytosol raises the question of whether a plastidial form contributes to starch biosynthesis in nonmutant tissue. The data presented here answer this question by showing that elimination of either AGPLLZM or AGPSEMZM in endosperm caused statistically significant reductions in starch content both at mid development and maturity. Comparison of mutant and nonmutant sibling kernels on the same ear ruled out the possibility that reduced endosperm starch resulted from compromised metabolism in the parent plant. In addition, AGPSEMZM mRNA does not accumulate in mature leaf, which is inconsistent with a maternal effect causing endosperm starch reduction in progeny kernels. Thus, the data demonstrate that plastidial and cytosolic forms of AGPase function together to generate normal levels of endosperm starch. Total endosperm AGPase activity was not reduced by the agpsemzm- or agpllzm- mutation, even though starch content was reduced by more than 7% in mature kernels in both instances. The magnitude of the effect is consistent with the observation that approximately 95% of the total AGPase in maize endosperm is extraplastidial (Denyer et al., 1996). Thus, loss or reduction of plastidial AGPase in the mutants may not have been detected as a statistically significant difference from the nonmutant activity level.

The genetic data implicate both AGPSEMZM and AGPLLZM as functioning in amyloplasts, although in vivo complementation in E. coli found that these two subunits together did not constitute functional AGPase. Thus, it is likely that one or more AGPase subunits from among AGPSLZM, BT2b, and AGPLEMZM also functions in endosperm to generate combinations of subunits that, together, constitute functional enzyme when expressed in E. coli. Alternatively, it is possible that some combinations of AGPase subunits are active in planta, even though they fail to restore glycogen accumulation in the heterologous E. coli system. Future genetic analyses will be needed to address this question. Mutation of agpslzm appeared to have no effect on endosperm starch content (Schlosser et al., 2012). The starch level in that study was estimated indirectly from near-infrared (NIR) spectroscopy, however, so the possibility remains that direct chemical quantification may reveal relatively small reductions in agpslzm- endosperm. Analysis of mutations in agplemzm are also needed to fully define which proteins in addition to those identified here, namely AGPSEMZM and AGPLLZM, provide plastidial AGPase activity in maize endosperm. A specific allele of bt2 that eliminates BT2b while allowing continued function of BT2a would also be required to test for endosperm function of the plastidial form.

The extent of the plastidial AGPase contribution to total endosperm starch accumulation remains to be determined. One possibility is that loss of either AGPSEMZM or AGPLLZM causes complete deficiency of the plastid form, so that the 7% reduction in starch represents the maximum plastid contribution. Alternatively, multiple plastidial AGPase SS and LS proteins may be expressed in endosperm, as they are in embryo and leaf, and the agpsemzm- and agpllzm- mutations do not completely eliminate the amyloplast enzyme. Double mutant combinations, therefore, will be required in order to test whether multiple plastidial AGPase isoforms function in amyloplasts.

Potential Metabolic Roles of Plastidial AGPase in Endosperm

Cytosolic AGPase is proposed to have evolved in Poaceae species owing to the metabolic advantage of locating the enzyme in the subcellular compartment with the highest availability of the ATP substrate (Comparot-Moss and Denyer, 2009). In contrast to chloroplasts, which produce ATP in the stroma, nonphotosynthetic plastids in endosperm import ATP from the cytosol, where its concentration is approximately 6- to 7-fold higher than in the organelle (Tiessen et al., 2012). Despite these considerations, cereals appear to have maintained selection not only for the cytosolic AGPase but also for the plastidial form(s) of the enzyme. This suggests a metabolic advantage to having AGPase in two compartments. The data presented here support this conclusion by showing that starch accumulation decreases if the plastidial AGPase is compromised.

A potential selective advantage of plastidial AGPase is to mediate the balance between necessary plastidial metabolic functions and starch deposition. Glc-1-P and/or Glc-6-P are imported into amyloplasts, as shown by the remnant starch levels in mutants lacking cytosolic AGPase or the ADPGlc transporter. The fate of imported Glc-1-P and Glc-6-P must be split between the starch sink and nonstarch metabolism that occurs within the plastid, including glycolytic steps, amino acid biosynthesis, the pentose phosphate pathway, etc. AGPase in the stroma could function to convert hexose phosphate that accumulates in excess of other metabolic requirements into ADPGlc and thus increase total starch content. This is consistent with the observed reduction in starch when plastidial AGPase was affected by the agpsemzm- or agpllzm- mutation. Additionally, plastidial AGPase may provide a means of modulating metabolism during endosperm development as needs change (e.g. the decrease in the starch deposition rate in maize endosperm at approximately 20 DAP; Prioul et al., 1994). The concentrations of the AGPase products and substrates in barley amyloplasts at mid development are such that the plastidial enzyme operates near equilibrium (Tiessen et al., 2012). Thus, plastidial AGPase potentially could respond to the metabolic environment so that, in some conditions, it catalyzes the reverse reaction and generates Glc-1-P from imported ADPGlc. Such a system would allow cytosolic AGPase to be adapted for maximal ADPGlc formation, with subsequent modulation of the net reaction within the amyloplast, and this may provide flexibility to endosperm metabolism that is evolutionarily advantageous.

CONCLUSION

The genes agplemzm, agpsemzm, agpllzm, and agpslzm encode AGPase subunits that are functional for enzyme activity when combined with appropriate partner subunits. The plastid-targeted transcript generated from bt2 also encodes an enzymatically functional protein. Full-length proteins encoded by agpsemzm, agplemzm, agpllzm, agpslzm, and the BT2b transcript are all capable of transport into plastids. Amyloplast AGPase is required for the normal level of starch accumulation in cereal endosperms even when the cytosolic form of the enzyme is fully functional. The genes agpllzm and agpsemzm both contribute to plastidial AGPase activity in endosperm and also function in plastids within leaf tissue and embryo, respectively. At least one additional AGPase LS gene functions in leaf, and one additional AGPase SS gene functions in embryo.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant Materials and Maize Genetic Nomenclature

Maize (Zea mays) plants were grown during summer field seasons at Iowa State University Curtiss Farm. Developing kernels from self-pollinated ears were collected 20 DAP. The sixth, seventh, eighth, and ninth vegetative leaves from greenhouse- or field-grown plants were harvested at midday about 1 month after planting for starch content and transcript analyses. Immature kernels or leaf samples were frozen in liquid N2 and stored at −80°C until use. The mutation agpsemzm-Mu1 was isolated in the purple-seeded inbred line W22-ACR that was used to generate the UniformMu transposon insertion population (McCarty et al., 2005). Heterozygous plants containing agpsemzm-Mu1 were backcrossed at least four times to the nonmutant parent inbred, after which homozygous mutants were obtained by self-pollination. Similarly, agpllzm-Ds1 was isolated by Ds transposon mutagenesis in a separately maintained, yellow-seeded W22 inbred, referred to here as W22D (Ahern et al., 2009). Heterozygotes were again backcrossed at least four times to the nonmutant inbred parent prior to isolating homozygous mutants after self-pollination.

Genetic nomenclature follows the published standard for maize (http://www.maizegdb.org/maize_nomenclature.php). Gene loci are designated in italic lowercase letters (e.g. agpsemzm). Wild-type alleles are designated with an uppercase first letter (e.g. Agpsemzm) or by the symbol +. Specific mutations are designated by the locus name followed by a dash and a unique allele name (e.g. agpsemzm-Mu1), and unspecified nonfunctional mutations are indicated by the locus name with an undesignated dash (e.g. agpsemzm-). mRNA or cDNA produced from a locus is indicated by italic uppercase letters (e.g. AGPSEMZM mRNA). Polypeptide products of genes are indicated by uppercase letters without italics (e.g. AGPSEMZM).

Transcript Level Measurement by RT-PCR and RNA-Seq

Total RNA was isolated using the Plant RNA Easy Kit (Qiagen; catalog no. 74904) and the RNase-Free DNase Set (Qiagen; catalog no. 79254). RT employed the SuperScript III First-Strand Synthesis System (Invitrogen; catalog no. 18080-051). RT-PCR was in a 25-μL total volume, including 1× Green GoTaq Flexi buffer, 1.5 mm MgCl2, 1.25 units of GoTaq DNA polymerase (Promega; catalog no. M8298), 0.2 mm each deoxyribonucleotide triphosphate, 1 μm each primer, and 1.5 ng of cDNA. Thirty PCR cycles were used for the amplifications, except for AGPSLZM, which was amplified by 35 PCR cycles. The nucleotide sequences of all fragments generated by RT-PCR were determined to confirm that the expected region of the cDNA was amplified.

Transcript levels measured by RNA-Seq were extracted from the qTeller analysis (J. Schnable, personal communication; www.qTeller.com) of publicly available data sets containing raw whole-transcriptome sequence data (Li et al., 2010; Davidson et al., 2011; Waters et al., 2011). qTeller uses the GSNAP algorithm (Wu and Nacu, 2010) to map sequence reads to gene models in the inbred B73 reference genome and the CUFFLINKS algorithm (Trapnell et al., 2010) to quantify transcript abundance based on counts of aligned reads. qTeller quantifies transcript abundance by counting sequence reads that map to a unique genomic locus within a gene model or to two distinct locations and discards any read that maps to more than two locations. Reads that map to two locations are distributed for quantification between the two loci based on a weighted factor determined from the ratio of unique read abundances for those gene models.

Genotype Determination and Transcript Detection in Mutant Lines

Genomic DNA was isolated from lyophilized maize leaves using the cetyl-trimethyl-ammonium bromide method (Saghai-Maroof et al., 1984) or from mature seeds using the following procedure. Kernels were imbibed overnight at 42°C in 0.3% (w/v) sodium metabisulfite and 1% (w/v) lactic acid, pH 3.8. Pericarp was removed, and the embryo and a portion of the endosperm were ground with a mortar and pestle in 1 mL of extraction buffer (100 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8, 50 mm EDTA, 500 mm NaCl, and 10 mm β-mercaptoethanol). After homogenization, 100 μL of 20% (w/v) SDS was added. The homogenate was incubated at 65°C for 40 min and then centrifuged for 10 min at 10,000g. The supernatant was removed, and 500 μL of 5 m potassium acetate was added. The sample was centrifuged again in the same conditions, and the supernatant was collected and processed further according to the cetyl-trimethyl-ammonium bromide method beginning with chloroform-octanol extraction.

PCR amplification of genomic DNA revealed the presence or absence of specific alleles of either agpsemzm or agpllzm. Gene-specific primer sequences are listed in Supplemental Table S1, and their locations are shown in Figures 4 and 5. Primer 9242 (5′-AGAGAAGCCAACGCCAWCGCCTCYATTTCGTC-3′) is located within the Mu transposon family inverted repeat sequence. Primers from the Ds transposon left border and right border were JSR05 and JSR01, respectively (Ahern et al., 2009). Additional primer sets (Figs. 4 and 5) were used to detect AGPSEMZM or AGPLLZM mRNA in wild-type or mutant plants by RT-PCR as described in the preceding section.

AGPase Zymograms

The following method was used for in-gel assay of AGPase activity (D. Braun, personal communication). Five grams of leaf tissue, 20 pooled embryos, or single endosperms were ground in extraction buffer (100 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7, 40 mm β-mercaptoethanol added fresh, 10 mm MgCl2, 100 mm KCl, and 15% glycerol) using a prechilled mortar and pestle on ice. The homogenate was centrifuged at 40,000g for 30 min at 4°C, and the supernatant was stored at −80°C or used immediately. Equal amounts of protein (80 μg) were loaded onto a 7.5% (w/v) native acrylamide gel (Bio-Rad; catalog no. 161-1100) and electrophoresed in Laemmli buffer lacking SDS at 4°C at 90 V for 2 to 4 h. The gel was then incubated overnight at 37°C in 100 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8, 5 mm β-mercaptoethanol, 5 mm CaCl2, 10 mm MgCl2, 5 mm Glc-1-P, 5 mm ATP, and 10 mm 3-PGA. Gels were photographed on a dark background to visualize white precipitate bands. Control assays omitted either ATP or Glc-1-P.

Quantitative AGPase Assays

Tissue was ground in lysis buffer (50 mm potassium phosphate, pH 7, 5 mm MgCl2, and 0.5 mm EDTA) in a prechilled mortar and pestle. The homogenate was centrifuged at 10,000g for 10 min at 4°C, and the supernatant was passed through a 0.45-μm filter. Filtered crude lysate (130 μL) was loaded onto a 0.5-mL Zebra Spin Desalting Column (Thermo Scientific; catalog no. 89882) and eluted into 100 mm MOPS-HCl, pH 7.4. Bovine serum albumin (BSA) was added to a final concentration of 0.5 mg mL−1. Desalted lysates were prepared from three biological replicates for each tissue and genotype, and each lysate was assayed in duplicate.

AGPase activity was measured in the direction of ATP and Glc-1-P formation following a previously published method with minor modifications (Boehlein et al., 2005). Reactions in 100-μL volumes contained 100 mm MOPS-HCl, pH 7.4, 0.4 mg mL−1 BSA, 7 mm MgCl2, 1 mm ADPGlc, 20 mm 3-PGA, and 1 mm sodium pyrophosphate. Preliminary experiments confirmed that activity increased linearly with time and the amount of enzyme added (data not shown). Reactions were incubated at 37°C for 10 min, boiled for 1 min, and centrifuged at 12,000g for 2 min at room temperature. The supernatant was transferred to a fresh tube and brought to a total volume of 500 μL of development mix to quantify Glc-1-P. This reaction contained 100 mm MOPS-HCl, pH 7.4, 0.1 mg mL−1 BSA, 7 mm MgCl2, 0.6 mm NAD+, 1 unit of Glc-6-P dehydrogenase (Sigma; catalog no. G-7877), and 1 unit of phosphoglucomutase (Sigma; catalog no. P-3397). After incubation, the reaction was centrifuged at 12,000g for 5 min at room temperature, and then the absorbance of the supernatant was measured at 340 nm to quantify NADH and consequently Glc-1-P.

Qualitative and Quantitative Determination of Starch and Protein Content

Qualitative Analysis of Starch Content

Seedling leaves were harvested at the end of the light phase of the diurnal cycle and decolorized by boiling in 80% ethanol for 30 min. Decolorized leaves were immersed in freshly prepared I2/KI solution (1% (w/v) potassium iodide, 0.1% (w/v) iodine) for 5 min and then destained in water for 1 to 2 h. Starch content in embryo and endosperm was estimated qualitatively by thawing frozen kernels harvested 20 DAP on ice, slicing them longitudinally with a fresh scalpel blade, then staining and destaining in I2/KI solution as was done for leaves.

Quantitative Analysis of Embryo Starch Content

For each assay, 20 dissected embryos were pooled from sibling kernels of a single ear harvested 20 DAP. Tissue was homogenized in water with a mortar and pestle, and then duplicate starch samples were collected by centrifugation from a known volume of the crude lysate. A third sample of the crude homogenate was dried at 80°C to determine the dry weight of the tissue analyzed. Starch in each duplicate sample was completely hydrolyzed to Glc by treatment with amyloglucosidase and then quantified by a colorimetic assay as described previously with minor but significant modifications (Lin et al., 2012). One difference was that the starch pellet was washed twice by suspension in cold 80% (v/v) ethanol. A second difference was that starch pellets from a single pool were dissolved in 1 mL of dimethyl sulfoxide rather than the 1.5-mL volume used previously. Finally, an important aspect of the assay was to titrate the amount of hydrolyzed starch added to the GOPOD Glc detection assay (Megazyme; catalog no. K-GLUC) in order to ensure linearity. The Glc measurement saturated and even declined in efficiency as the sample volume was increased. Using the volumes noted here, linear quantification of Glc content was achieved using only 2 μL of the amyloglucosidase digest added to 150 μL of GOPOD reagent.

Quantitative Analysis of Leaf Starch Content

Approximately 500 mg of leaf tissue from a single greenhouse-grown seedling was harvested at the end of the light phase of the diurnal cycle, weighed, and decolorized by boiling in 80% (v/v) ethanol. This tissue was homogenized in water, and starch content was quantified as described for embryo tissue. Four individual plants were analyzed independently for each genotype, with two technical repeats each.

Quantitative Analysis of Endosperm Starch Content

Starch was quantified from single endosperms of 20-DAP kernels or mature kernels as described for embryos. Four kernels from each of three different parent ears were analyzed for each genotype to compare the starch contents of agpllzm-/agpllzm- or agpsemzm-/agpsemzm- endosperm and isogenic wild-type tissue. In addition, mature endosperm tissue was analyzed from individual kernels of a self-pollinated ear of an agpllzm-Ds1/+ heterozygous parent. This allowed comparison of endosperm starch content between agpllzm-Ds1 homozygous mutants and heterozygous or homozygous wild-type kernels, all of which developed on the same ear. Mature kernels were imbibed by soaking overnight at 50°C in 0.3% (w/v) sodium metabisulfate and 1% (w/v) lactic acid, pH 3.8, prior to dissecting the endosperm.

Quantitative Analysis of Total Endosperm Protein Content

Endosperms were dissected from 20-DAP kernels or mature kernels that had been imbibed as described for starch content analysis. These were ground in water and then dried in air. Known amounts of dried endosperm were applied to a LECO TruSpec CN analyzer for the determination of percentage total nitrogen content according to the American Association of Cereal Chemists International-approved method 46-30.01 (http://dx.doi.org/10.1094/AACCIntMethod-46-30.01). Conversion from percentage total nitrogen to percentage total protein was estimated using the conversion factor 6.25.

Expression of AGPase LS and SS in Escherichia coli

cDNAs including the predicted mature coding regions of BT2b, AGPLEMZM, AGPLLZM, AGPSEMZM, and AGPSLZM were synthesized commercially (Genscript). These sequences were amplified by PCR using oligonucleotide primers that introduced NcoI sites at the 5′ end of the coding region and SacI sites at the 3′ end. In some instances, the N-terminal coding regions were modified by adding or subtracting codons in the 5′ end primer used for PCR amplification. The specific codons included in each expressed protein are indicated in Supplemental Figure S1.

Tests for in vivo AGPase activity in E. coli employed an expression system described previously for potato (Solanum tuberosum) tuber or maize endosperm cytosolic AGPase (Iglesias et al., 1993; Giroux et al., 1996; Greene and Hannah, 1998). cDNAs encoding AGPase LS were cloned into the spectinomycin resistance vector pMON17336, and those encoding AGPase SS were ligated into the kanamycin resistance vector pMON17335 (Iglesias et al., 1993). Expression of AGPase LS was from the isopropylthio-β-galactoside-inducible tryptophan operon-lactose operon hybrid promoter (de Boer et al., 1983), and AGPase SS expression was directed by the nalidixic acid-inducible recombination deficient A promoter of E. coli (Feinstein et al., 1983). Plasmids were transformed singly or in pairwise combination into the E. coli glgC− mutant AC70R1-504 (Iglesias et al., 1993), grown overnight on induction medium containing 0.2 mm isopropylthio-β-galactoside and 20 μg mL−1 nalidixic acid (Sigma; catalog no. N4382), and then tested for glycogen accumulation by exposure to iodine vapor for 30 s at room temperature.

Expression of AGPase LS-GFP and AGPase SS-GFP Fusion Proteins in Leaf Protoplasts

Plasmids for the transient expression of GFP fusion proteins were constructed as follows. Oligonucleotide primers were designed to introduce a BamHI cloning site immediately upstream of the initiation codon and downstream of codon 98 or 99 in each of the AGPase subunit mRNA sequences. Two upstream primers were designed for bt2, one targeted to the first exon that initiates the BT2a protein and the other to the second exon that initiates the BT2b protein (Rösti and Denyer, 2007). Fragments were amplified by PCR from endosperm or leaf cDNA, which were then digested with BamHI and cloned into the expression vector HBT-sGFP(S65T) (Chiu et al., 1996). This vector provides a hybrid promoter containing the control regions of the cauliflower mosaic virus 35S gene fused to the TATA box, transcription initiation site, and 5′ untranslated region of the C4ppdk1 gene (Sheen, 1993), the BamHI cloning site, and then an optimized GFP coding sequence. The insert in each plasmid was sequenced in its entirety to verify that the expected fragment had been cloned free of PCR errors.

Protoplasts were isolated from the middle portion of the second leaves of dark-grown maize seedlings as described (J. Sheen; http://genetics.mgh.harvard.edu/sheenweb/) and suspended in 0.6 m mannitol, 4 mm MES, pH 5.7, and 20 mm KCl. Approximately 50 μg of plasmid DNA was added to 200 μL of protoplast suspension. An equal volume of 40% (w/v) polyethylene glycol 4000, 0.3 m mannitol, and 100 mm CaCl2 was added, and the mixture was incubated for 7 min at room temperature. Protoplasts were collected by centrifugation at 50g for 5 min at room temperature and suspended gently in 0.5 mL of 0.6 m mannitol, 4 mm MES, pH 5.7, and 4 mm KCl. The protoplasts were then incubated at room temperature in the dark with shaking at 40 rpm for 20 to 24 h. The transformed protoplasts were visualized with a Leica SP2 confocal microscope. The excitation wavelength for observation of GFP was 488 nm, and the emission filter range was 500 to 550 nm. For the detection of chlorophyll autofluorescence, the excitation wavelength was 558 nm and the emission filter range was 606 to 770 nm.

Supplemental Data

The following materials are available in the online version of this article.

Supplemental Figure S1. Alignment of AGPase SS and LS amino acid sequences.

Supplemental Table S1. Oligonucleotide primer sequences.

Acknowledgments

We thank James Schnable (Danforth Plant Science Center), who contributed to this study by developing the qTeller software algorithm, using it to measure transcript abundance from published, raw RNA-Seq data, making those results publicly available at the qTeller Web site, and providing explanations of the operation of the software. Maize lines with sequence-indexed transposon insertions were provided from the UniformMu project or the Ac/Ds genome-wide transposon tagging project through the Maize Genetics Cooperation Stock Center (http://maizecoop.cropsci.uiuc.edu/). The Iowa State University DNA Sequencing and Synthesis Facility provided DNA sequencing and oligonucleotide synthesis services. Total protein content was estimated by elemental analysis using a LECO TruSpec CN instrument at the Iowa State University Soil and Plant Analysis Laboratory. Confocal microscopy instrumentation was provided by the Iowa State University Confocal Microscopy and Multiphoton Facility. We thank Margie Carter for providing her expertise and assistance for confocal microscopy observations, Dr. Jen Sheen for providing advice regarding maize protoplast transfection, and Dr. Susan Boehlein for providing assistance to implement the AGPase enzyme assay.

Glossary

- PPi

inorganic pyrophosphate

- LS

large subunit

- SS

small subunit

- cDNA

complementary DNA

- DAP

days after pollination

- RT

reverse transcription

- 3-PGA

3-phosphoglyceric acid

- I2/KI

iodine/potassium iodide

- BSA

bovine serum albumin

References

- Ahern KR, Deewatthanawong P, Schares J, Muszynski M, Weeks R, Vollbrecht E, Duvick J, Brendel VP, Brutnell TP. (2009) Regional mutagenesis using Dissociation in maize. Methods 49: 248–254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bae JM, Giroux M, Hannah LC. (1990) Cloning and characterization of the brittle-2 gene of maize. Maydica 35: 317–322 [Google Scholar]

- Balmer Y, Vensel WH, DuPont FM, Buchanan BB, Hurkman WJ. (2006) Proteome of amyloplasts isolated from developing wheat endosperm presents evidence of broad metabolic capability. J Exp Bot 57: 1591–1602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhave MR, Lawrence S, Barton C, Hannah LC. (1990) Identification and molecular characterization of shrunken-2 cDNA clones of maize. Plant Cell 2: 581–588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boehlein SK, Sewell AK, Cross J, Stewart JD, Hannah LC. (2005) Purification and characterization of adenosine diphosphate glucose pyrophosphorylase from maize/potato mosaics. Plant Physiol 138: 1552–1562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burton RA, Johnson PE, Beckles DM, Fincher GB, Jenner HL, Naldrett MJ, Denyer K. (2002) Characterization of the genes encoding the cytosolic and plastidial forms of ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase in wheat endosperm. Plant Physiol 130: 1464–1475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu WL, Niwa Y, Zeng W, Hirano T, Kobayashi H, Sheen J. (1996) Engineered GFP as a vital reporter in plants. Curr Biol 6: 325–330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi SB, Kim KH, Kavakli IH, Lee SK, Okita TW. (2001) Transcriptional expression characteristics and subcellular localization of ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase in the oil plant Perilla frutescens. Plant Cell Physiol 42: 146–153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comparot-Moss S, Denyer K. (2009) The evolution of the starch biosynthetic pathway in cereals and other grasses. J Exp Bot 60: 2481–2492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cossegal M, Chambrier P, Mbelo S, Balzergue S, Martin-Magniette ML, Moing A, Deborde C, Guyon V, Perez P, Rogowsky P. (2008) Transcriptional and metabolic adjustments in ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase-deficient bt2 maize kernels. Plant Physiol 146: 1553–1570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson RM, Hansey CN, Gowda M, Childs KL, Lin H, Vaillancourt B, Sekhon RS, de Leon N, Kaeppler SM, Jiang N, et al. (2011) Utility of RNA sequencing for analysis of maize reproductive transcriptomes. Plant Genome 4: 191–203 [Google Scholar]

- de Boer HA, Comstock LJ, Vasser M. (1983) The tac promoter: a functional hybrid derived from the trp and lac promoters. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 80: 21–25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denyer K, Dunlap F, Thorbjørnsen T, Keeling PL, Smith AM. (1996) The major form of ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase in maize endosperm is extra-plastidial. Plant Physiol 112: 779–785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson DB, Preiss J. (1969) Presence of ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase in shrunken-2 and brittle-2 mutants of maize endosperm. Plant Physiol 44: 1058–1062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emanuelsson O, Nielsen H, von Heijne G. (1999) ChloroP, a neural network-based method for predicting chloroplast transit peptides and their cleavage sites. Protein Sci 8: 978–984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinstein SI, Chernajovsky Y, Chen L, Maroteaux L, Mory Y. (1983) Expression of human interferon genes using the recA promoter of Escherichia coli. Nucleic Acids Res 11: 2927–2941 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geigenberger P. (2011) Regulation of starch biosynthesis in response to a fluctuating environment. Plant Physiol 155: 1566–1577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giroux M, Smith-White B, Gilmore V, Hannah LC, Preiss J. (1995) The large subunit of the embryo isoform of ADP glucose pyrophosphorylase from maize. Plant Physiol 108: 1333–1334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giroux MJ, Hannah LC. (1994) ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase in shrunken-2 and brittle-2 mutants of maize. Mol Gen Genet 243: 400–408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giroux MJ, Shaw J, Barry G, Cobb BG, Greene T, Okita T, Hannah LC. (1996) A single mutation that increases maize seed weight. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93: 5824–5829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene TW, Hannah LC. (1998) Enhanced stability of maize endosperm ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase is gained through mutants that alter subunit interactions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95: 13342–13347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannah LC, Futch B, Bing J, Shaw JR, Boehlein S, Stewart JD, Beiriger R, Georgelis N, Greene T. (2012) A shrunken-2 transgene increases maize yield by acting in maternal tissues to increase the frequency of seed development. Plant Cell 24: 2352–2363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannah LC, Greene T (2009) The complexities of starch biosynthesis in cereal endosperms. In AL Kriz, BA Larkins, eds, Molecular Genetic Approaches to Maize Improvement. Springer-Verlag, Berlin, pp 287–301 [Google Scholar]

- Hannah LC, Shaw JR, Giroux MJ, Reyss A, Prioul JL, Bae JM, Lee JY. (2001) Maize genes encoding the small subunit of ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase. Plant Physiol 127: 173–183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang B, Chen J, Zhang J, Liu H, Tian M, Gu Y, Hu Y, Li Y, Liu Y, Huang Y. (2010) Characterization of ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase encoding genes in source and sink organs of maize. Plant Mol Biol Rep 29: 563–572 [Google Scholar]

- Huang H, Møller IM, Song SQ. (2012) Proteomics of desiccation tolerance during development and germination of maize embryos. J Proteomics 75: 1247–1262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iglesias AA, Barry GF, Meyer C, Bloksberg L, Nakata PA, Greene T, Laughlin MJ, Okita TW, Kishore GM, Preiss J. (1993) Expression of the potato tuber ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase in Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem 268: 1081–1086 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson PE, Patron NJ, Bottrill AR, Dinges JR, Fahy BF, Parker ML, Waite DN, Denyer K. (2003) A low-starch barley mutant, risø 16, lacking the cytosolic small subunit of ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase, reveals the importance of the cytosolic isoform and the identity of the plastidial small subunit. Plant Physiol 131: 684–696 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SK, Hwang SK, Han M, Eom JS, Kang HG, Han Y, Choi SB, Cho MH, Bhoo SH, An G, et al. (2007) Identification of the ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase isoforms essential for starch synthesis in the leaf and seed endosperm of rice (Oryza sativa L.). Plant Mol Biol 65: 531–546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li P, Ponnala L, Gandotra N, Wang L, Si Y, Tausta SL, Kebrom TH, Provart N, Patel R, Myers CR, et al. (2010) The developmental dynamics of the maize leaf transcriptome. Nat Genet 42: 1060–1067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Q, Huang B, Zhang M, Zhang X, Rivenbark J, Lappe RL, James MG, Myers AM, Hennen-Bierwagen TA. (2012) Functional interactions between starch synthase III and isoamylase-type starch-debranching enzyme in maize endosperm. Plant Physiol 158: 679–692 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin TP, Caspar T, Somerville CR, Preiss J. (1988) A starch deficient mutant of Arabidopsis thaliana with low ADPglucose pyrophosphorylase activity lacks one of the two subunits of the enzyme. Plant Physiol 88: 1175–1181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mains EB. (1949) Heritable characters in maize: linkage of a factor for shrunken endosperm with the a1 factor for aleurone color. J Hered 40: 21–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majeran W, Cai Y, Sun Q, van Wijk KJ. (2005) Functional differentiation of bundle sheath and mesophyll maize chloroplasts determined by comparative proteomics. Plant Cell 17: 3111–3140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majeran W, Friso G, Ponnala L, Connolly B, Huang M, Reidel E, Zhang C, Asakura Y, Bhuiyan NH, Sun Q, et al. (2010) Structural and metabolic transitions of C4 leaf development and differentiation defined by microscopy and quantitative proteomics in maize. Plant Cell 22: 3509–3542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarty DR, Settles AM, Suzuki M, Tan BC, Latshaw S, Porch T, Robin K, Baier J, Avigne W, Lai J, et al. (2005) Steady-state transposon mutagenesis in inbred maize. Plant J 44: 52–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morell MK, Bloom M, Knowles V, Preiss J. (1987) Subunit structure of spinach leaf ADPglucose pyrophosphorylase. Plant Physiol 85: 182–187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohdan T, Francisco PB, Jr, Sawada T, Hirose T, Terao T, Satoh H, Nakamura Y. (2005) Expression profiling of genes involved in starch synthesis in sink and source organs of rice. J Exp Bot 56: 3229–3244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okita TW, Nakata PA, Anderson JM, Sowokinos J, Morell M, Preiss J. (1990) The subunit structure of potato tuber ADPglucose pyrophosphorylase. Plant Physiol 93: 785–790 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preiss J, Danner S, Summers PS, Morell M, Barton CR, Yang L, Nieder M. (1990) Molecular characterization of the brittle-2 gene effect on maize endosperm ADPglucose pyrophosphorylase subunits. Plant Physiol 92: 881–885 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prioul JL, Jeannette E, Reyss A, Grégory N, Giroux M, Hannah LC, Causse M. (1994) Expression of ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase in maize (Zea mays L.) grain and source leaf during grain filling. Plant Physiol 104: 179–187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rösti S, Denyer K. (2007) Two paralogous genes encoding small subunits of ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase in maize, Bt2 and L2, replace the single alternatively spliced gene found in other cereal species. J Mol Evol 65: 316–327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]