Abstract

Advanced heart failure represents a leading public health problem in the developed world. The clinical syndrome results from the loss of viable and/or fully functional myocardial tissue. Designing new approaches to augment the number of functioning human cardiac muscle cells in the failing heart serve as the foundation of modern regenerative cardiovascular medicine. A number of clinical trials have been performed in an attempt to increase the number of functional myocardial cells by the transplantation of a diverse group of stem or progenitor cells. Although there are some encouraging suggestions of a small early therapeutic benefit, to date, no evidence for robust cell or tissue engraftment has been shown, emphasizing the need for new approaches. Clinically meaningful cardiac regeneration requires the identification of the optimum cardiogenic cell types and their assembly into mature myocardial tissue that is functionally and electrically coupled to the native myocardium. We here review recent advances in stem cell biology and tissue engineering and describe how the convergence of these two fields may yield novel approaches for cardiac regeneration.

Introduction

Heart failure is a leading cause of death and hospitalization in the developed world (1–3). The clinical syndrome of heart failure arises when cardiac output cannot meet the metabolic demands of affected individuals. Most commonly this supply/demand mismatch results from a loss of fully functional myocardial tissue and an inability of the heart to meet physiologic demands (4). Current therapies of heart failure focus on symptomatic treatment of volume overload, prevention of ventricular remodeling, modulation of maladaptive neurohumoral responses, or device-based mechanical and electrical support (5). Of great significance, however, these therapies are not directly aimed at correcting the underlying pathophysiology of an inadequate number of normally organized functional myocardial cells. Cell based therapy aimed at replacing or augmenting the number of functional myocardial cells therefore represents an attractive therapeutic approach for heart failure. For such a cell-based approach to be successful, several major hurdles will have to be overcome. The optimum cell type(s) will have to be purified and expanded to result in a sufficient number of mature cardiomyocytes for robust myocardial regeneration. These cells will have to be assembled into an effective three-dimensional pumping machinery. This grafted tissue will then have to be electrically and functionally integrated with native myocardium in order to be capable of significantly augmenting the cardiac output of the failing heart, without resulting in arrhythmias or rejection. In this review we will explore the various stem cells populations thus far utilized in cardiac regeneration, the different tissue engineering approaches that have been employed to assemble functional myocardial tissue, and the future work that lies ahead.

I. The Human Experience: Clinical trials of cell therapy

After initial promising results of bone marrow stem cells therapy in animal studies, clinical trials in patients with acute myocardial infarction (MI) were initiated (Table 1). The first study, Transplantation Of Progenitors Cells and Regeneration Enhancement in Acute Myocardial Infarction (TOPCARE-AMI), was performed more than a decade ago. This phase-1 study allocated 20 patients with acute MI to receive either bone marrow-derived stem cells or circulating blood-derived progenitor cells into the infarct related artery (6). In this open label, uncontrolled trial, left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) and myocardial viability in the infarct zone improved significantly in both groups. After these promising initial results, several mid-sized randomized studies demonstrated a modest but statistically significant improvement in LVEF in post-MI patients, including the BOOST and REPAIR-AMI trial (7, 8). A post-hoc sub-group analysis of the REPAIR-AMI trial showed that bone marrow stem cell therapy was most effective in patients with a clearly depressed left ventricular (LV) function, which might prevent adverse ventricular remodeling to some extend and improve quality of life. Unfortunately, 5-year follow-up of the BOOST trial revealed that the improvement in LVEF was transient (9). These early results were subsequently confirmed by several international trials that did not find a beneficial long-term effect of bone marrow-derived stem cell therapy, including the REGENT trial, ASTAMI and the trial by Janssens et. al. (10–12). More recently yet, similar negative results were observed in the HEBE trial (13). In this multicenter trial, 200 patients with large first MI were randomized to mononuclear bone marrow cells, mononuclear peripheral blood cells or standard medical therapy. After 4-months of follow-up, there was no difference in regional myocardial function as assessed by Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) between the three different groups. In addition three randomized phase-2 multicenter studies, performed by the Cardiovascular Cell Therapy Research Network (CCTRN), did not find any beneficial effect of cell therapy in different patient groups and at various time points (14, 15). The FOCUS-CCTRN study explored transendocardial delivery of bone marrow mononuclear cell (BMMNC) in patients with chronic ischemic heart disease and LV dysfunction who had no revascularization options. In this double-blinded placebo controlled study transendocardial BMMNC injections were compared to injections of a cell-free substrate. BMMNCs did not improve myocardial perfusion, maximal oxygen consumption or LV end-systolic diameter compared to control (16). Two additional randomized placebo-controlled studies were geared at determining the optimum timing of BMMC coronary infusion after a myocardial infarction. The TIME trial compared intra-coronary cell infusion at 3 and 7 days after acute MI to placebo, and the LateTIME trial compared BMMNC coronary infusion to cell-free carrier control 2 to 3 weeks after acute MI. Neither of these two phase-2 CCTRN studies showed any beneficial effect of BMMC infusion on either global or regional LV-function (14, 15).

Table 1.

Selected large scale (patients > 50) Randomized Controlled Trials of Intracoronary Bone Marrow Derived Cell Infusion after Myocardial Infarction

| Trial | Year | No. of Patients | Study design | Effect (BM vs. control) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boost | 2004 | 60 | BMC injection vs. no therapy 5 days after acute MI | LVEF + 6% (P<0.05) in BMC group at 6 months, no significant difference after 5 years f/u | (7, 9) |

| REPAIR-AMI | 2006 | 204 | BMC injection vs. placebo 3–7 days of reperfusion therapy for acute MI | LVEF +2,5% (P=0.01) in BMC group at 4 months f/u | (8) |

| ASTAMI | 2006 | 100 | BMC injection vs. no therapy 4–8 days of reperfusion therapy for acute MI | No difference in LVEF between groups at 6 months f/u | (12) |

| Janssens et al. | 2006 | 67 | BMC inection vs. placebo within 24 hours of reperfusion therapy for acute MI | No difference in LVEF between groups at 4 months f/u | (11) |

| REGENT | 2009 | 200 | BMC injection vs. no therapy 3–12 days of reperfusion therapy for acute MI | No difference in LVEF between groups at 6 months f/u | (10) |

| HEBE | 2010 | 200 | BMC injection vs. no therapy within 8 days of reperfusion therapy for acute MI | No difference in LVEF between groups at 4 months | (13) |

| Late-TIME | 2011 | 87 | BMC inection vs. placebo within 2–3 weeks of reperfusion therapy for acute MI | No difference in LVEF between groups at 6 months f/u | (14) |

| TIME | 2012 | 120 | BMC injection vs. no therapy 3 or 7 days of reperfusion therapy for acute MI | No difference in LVEF between groups at 6 months f/u | (15) |

LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; BMC, bone marrow cells; MI, myocardial infarction; f/u, follow-up

Whereas the above-mentioned trials were performed in acute MI, Strauer et al. performed a study in patients with chronic heart failure (17). 391 patients with an ischemic etiology of heart failure were included, and 191 of these patients received an intracoronary bone marrow cell infusion. Patients treated with bone marrow stem cells had improved LV-function and reduced mortality compared to untreated controls. Although the study is the largest of its kind, it needs to be emphasized that the study was open label and was not randomized: Patients who refused to undergo bone marrow cell infusion were included in the control group. This could well have lead to a significant patient-selection bias and therefore severely limits the value of this trial.

A recent meta-analysis included 2625 patients with acute MI or ischemic heart disease from 50 trials (18). This study estimated the mean weighted differences for changes in LV ejection fraction, infarct size, LV end-systolic volume and LV end-diastolic volume in all individuals. Taking together, the selected studies in this meta-analysis showed an modest improvement in LV ejection fraction (3.96%), smaller infarct size (4.03%) and decreased end-systolic and end- diastolic volumes, in patients treated with BMC therapy compared to untreated controls.

Even this modest improvement, however, is undermined by the fact that the largest published trails to date, the REGENT, HEBE and TIME did not find a beneficial effect of bone marrow derived stem cell therapy and were not included in this meta-analysis. Thus, studies bone marrow derived stem cells have shown at best ambiguous results with no evidence of engraftment of transplanted cells.

As a result of these findings, it has been proposed that transplanted bone marrow derived stem cells engraft transiently while exerting paracrine effects and releasing growth factors promoting angiogenesis and endogenous cardiac repair (19). This hypothesis is supported by a study in a large animal model of acute MI that showed that the injection of bone marrow derived stem cells increased capillary density and improved collateral perfusion and regional cardiac function (20). Furthermore, fate-mapping studies in transgenic mouse models showed that after MI endogenous stem cells refresh adult cardiomyocytes (21). This endogenous repair mechanism of the mammalian heart could be enhanced through injection of bone marrow derived c-kit+ cells (22) or cardiac derived cells (23). Despite these disappointing initial results bone marrow cells remain the safest and source of human cells with the largest clinical experience (24). As a result, several trials including BAMI and RENEW are now entering phase-3.

The finding that paracrine factors secreted by transiently engrafted cells mediate most (if not all) of the clinical benefit, has generated new interest in the use of allogenic cell sources for cardiac regeneration. Despite the promise of this approach, the specific cytokines and growth factors secreted by transplanted cells and their mechanism of action remain unknown. Collectively these studies highlight the fact that future research should be aimed at developing a mechanistic understanding of any putative beneficial effects of bone marrow derived stem cell therapy for the treatment of heart failure. Future advances in this field could cover the delivery of genetically or pharmacologically modified bone marrow cells or the direct application of a cell-derived cocktail of paracrine and/or growth factors, and therefore facilitate the use of these cell types in cardiac regenerative medicine. .

Mesenchymal Stem Cell Therapy

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) are multipotent stromal cells with a predominantly mesodermal origin. MSC possess the capacity for self-renewal and the potential to phenotypic adopt a spectrum of different somatic cell types. Most of the reported in vitro data on MSC differentiation into cardiac like cell types relied on the exposure to the DNA demethylating chemical 5-azacytidine. The endogenous roles described for MSC are maintenance of the hematopoietic stem cell niche, organ homeostasis, wound healing and aging. Therefore bone marrow-derived MSCs appeared as an appealing cell source for cardiac regeneration (25–27). In the past decade a number of phase-1/2 trials were introduced. In an open-label randomized trial 96 patients were included who underwent primary percutaneous coronary intervention within 12 hours after acute MI. Patients received either autologous bone marrow derived MSCs or saline intracoronary infusion. LV ejection fraction was significantly improved by 8% in patients treated with MSCs compared to saline infusion (28). To investigate the safety and efficacy of intravenous allogeneic MSCs after acute MI a double-blinded placebo controlled trial was set up. Up to 6 months no difference in adverse cardiac events was observed, and renal, hepatic, and hematologic laboratory indexes were similar between groups. Additionally, MSC treated patients showed a 6% increase in ejection fraction at 3 months (29). The on going trail, Percutaneous Stem Cell Injection Delivery Effects on Neomyogenesis (POSEIDON) trial aims to compare the difference between transendocardial injection of autologous and allogenice MSCs in patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy. The first analyses revealed that both autologous and allogenic MSC treatment have low rates of serious adverse events (30). Furthermore, the Mesenchymal Stromal Cells in chronic ischemic Heart Failure (MSC-HF Trial) and Transendocardial Injection of Autologous Human Cells (bone marrow or mesenchymal) in Chronic Ischemic Left Ventricular Dysfunction and Heart Failure Secondary to Myocardial Infarction (TAC-HFT) trials are underway to examine the efficacy of MSC therapy in patients with chronic heart failure.

Cardiac Progenitor Cell therapy

Work from multiple laboratories has shown that resident cardiac progenitor cells (CPCs) (c-kit+, Sca-1+) isolated from adult heart auricles or heart biopsies can become functional cardiomyocytes through co-culture or epigenetic manipulation (with 5-Azacitidine) followed by TGF-β stimulation (31–33). This opened up the strategy of autologous CPC-based therapy for the injured heart. The CADUCEUS (CArdiosphere-Derived aUtologous stem CElls to reverse ventricular dysfunction) study was designed to evaluate cardiac stem cell infusions in patients after acute MI. In the treatment group, infarct-size-reduction and an increased LV ejection fraction were observed up to 1-year after treatment (34). Similar beneficial effects were found in the initial analysis of the still running SCIPIO (Stem Cell Infusion in Patients with Ischemic cardiomyopathy) trial. In this randomized open study design 20 patients received coronary infusion of 1 million CPCs 4 months after CABG. In the treatment group, infarct-size-reduction and an increased LVEF were observed up to 1-year after treatment (35, 36).

Currently, the AutoLogous Human CArdiac-Derived Stem Cell to Treat Ischemic cArdiomyopathy (ALCADIA) study is aiming to evaluate the safety and efficacy on the transplantation of autologous human cardiac-derived stem cells with the controlled release of basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) in patients with severe refractory heart failure. The first results of the ALCALDIA trial are expected later this year. Further th ALLSTRAR trail will be the forst phase-2 trail to examine the safety of cardiac-derived cell therapy in a phase 2 trial. Thus, although the early results show the promise of autologous CPC infusion therapy, the long-term benefits remain uncertain. Furthermore, it remains unclear if the observed improvements in cardiac function are due to true regeneration or to cardio-protective or paracrine effects as a result of transient engraftment (as earlier discussed for bone marrow cells).

Potential of Skeletal Myoblast in cell therapy

Skeletal muscle has the intrinsic capacity of repair and regeneration via the proliferation and differentiation of skeletal myoblasts. Since this tissue can be acquired in an autologous manner, it lacks the risk of immunological rejection (37, 38). Although, early trials demonstrated an improvement in LV-function as well as an improvement of symptoms (39–42), this effect was not observed in the follow-up double-blinded placebo-controlled trial (MAGIC Trial). In contrast, there was evidence of early postoperative arrhythmic events and poor engraftment and/or survival of injected cells (43). Thus, despite the theoretical appeal of skeletal myoblasts as a cell source for regenerative myocardial therapy, the clinical outcomes severely limit their applicability (37, 38).

II. From Embryos to Embryonic Stem Cells: Lessons from development

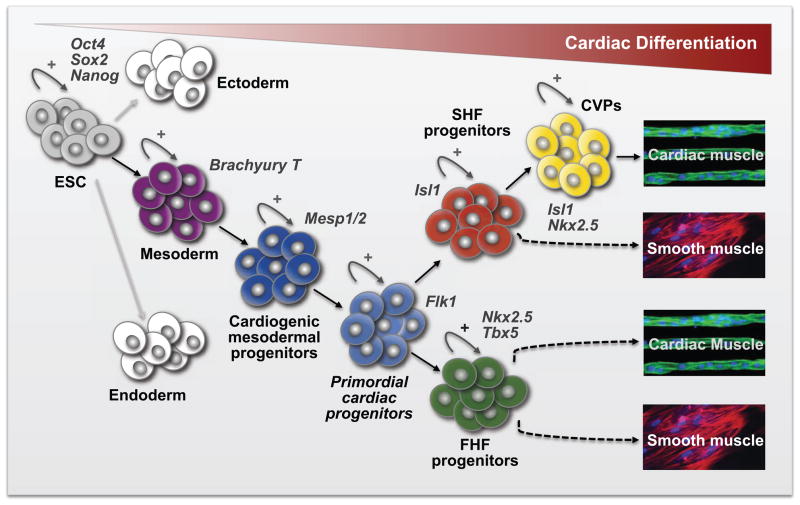

Understanding the normal cellular differentiation of cardiac progenitors and the assembly of their differentiated progeny into the highly specialized 3-dimensional structure of the four- chambered mammalian heart will likely represent a key milestone in the quest for genuine cardiac regeneration. In this regard, recent studies have uncovered a series of early heart progenitors that bring about the generation of the diverse cell types that constitute the mature mammalian heart (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Cardiac Lineage Commitment and Differentiation: The generation of Cardiac myocytes from embryonic stem cells.

ESC are pluripotent stem cells that express the transcription factors Oct4, Sox2, and Nanog and can give rise to the three embryonic germ layers; ectoderm, mesoderm and endoderm. Differentiation of ESC along the cardiac lineage results in the sequential generation of mesodrmal progenitors (Brachyury T+), cardiogenic mesodermal progenitors (Mesp1/2+), multipotent cardiovascular progenitors (Flk1+), multipotent FHF (Nkx2.5+/Tbx5+) and SHF (Isl1+) progenitors, and committed ventricular progenitors (CVPs, Isl1+/Nkx2.5+). The differentiated progeny give rise to functional cardiomyocytes and smooth muscle cells.

ESC, Embryonic Stem Cells; FHF, First Heart Field; SHF, Second Heart Field; CVP, Committed Ventricular Progenitors. Capacity for expansion or self-renewal is indicated with a circular arrow and + sign.

The early heart arises from primordial cardiogenic mesoderm progenitors that express the related transcription factors Mesp1/2. These progenitors give rise to multipotent progenitors in the first-heart-field (FHF) and the second-heart-field (SHF), a closely related set of cells in the developing mesoderm (48–50). The FHF arises from the anterior lateral mesoderm and forms the cardiac crescent in early embryogenesis. Later in development, these cells coalesce into the linear heart tube and ultimately give rise to the left ventricle of the mature 4-chambered mammalian heart. Progenitors of the SHF arise in the pharyngeal and splanchnic mesoderm and subsequently migrate into the developing heart to give rise to the right ventricle (RV), the outflow tract (OFT), and portions of the inflow tract (IFT). The LIM-homeodomain transcription factor Islet1 (Isl1) appears to mark these early cardiac progenitors and to be functionally important for their specification and differentiation (51–53), whereas the T-box transcription factor Tbx5 appears to mark the early progenitors of the FHF (54–56). In contrast to murine cardiogenesis, human cardiac development occurs over a considerably longer period of time and requires several orders of magnitude more cells. Accordingly, the period of cardiac progenitor expansion and lineage diversification must also be extended. Nonetheless, recent work has identified human multipotent fetal Isl1 positive cardiovascular progenitor populations that give rise to the cardiomyocyte, smooth muscle, and endothelial lineages in the developing heart. A subset of these early cardiac progenitor populations expressing Isl1 are localized to the fetal atria and proximal/medial OFT and gives rise to lineage-restricted intermediates marked by Isl1 in combination with Nkx2-5 or other cardiac differentiation markers (57).

Non-cell autonomous cues in embryonic development

The early cardiac progenitors of the developing heart are subject to a continuously changing microenvironment within the developing embryo. Changes in the activation of cell signaling pathways, cell migration, as well as changes of the three-dimensional architecture during the morphogenesis of the primitive heart form the dynamics. The developing cardiac progenitor populations are therefore exposed to significant temporally and spatially regulated non-cell autonomous signaling molecules. During the later cardiac development, the robust expansion of cardiac progenitors is critical for the ventricular chamber to achieve sufficient muscle mass necessary for the mechanical work to maintain adequate blood flow for the exponentially growing embryo. This increase in muscle mass has to be coordinated between the different chambers of the mammalian heart in order to avoid congenital malformations. Recent advances have suggested that canonical Wnt signaling appears to play a critical role in the expansion of Isl1+ SHF cardiac progenitors and their differentiated progeny (58, 59). Gain of function mutations of β-catenin that result in the constitutive activation of canonical Wnt signaling in E8.5-9.5 SHF progenitors results in robust expansion and inhibition of differentiation of these cell populations both in vitro and in vivo (59–62). Interestingly, recent work now also suggests that Hippo/Yap signaling, which is well recognized to control organ size in Drosophila (63), may control mammalian heart size by suppressing Wnt signaling and thereby restricting cardiomyocyte proliferation (64–66). Similarly, stage specific expression of the Activin A and BMP4 signaling proteins appear to be critical in mesodermal and cardiac differentiation during normal in vivo cardiac development as well as in vitro cellular differentiation (67–70). Thus, defining the cell autonomous and non-cell autonomous cues that control cardiac progenitor expansion and differentiation will be critical to understanding normal development and generating the cell populations necessary for regenerative cardiovascular medicine (62, 64, 67, 68, 70).

Proliferation of post-natal cardiac myocytes

Annual cardiomyocyte turnover in the mammalian heart was estimated between 1 and 4% and predominantly occurs through renewal of preexisting cardiac myocytes (44). Unlike the adult mammalian heart, certain fish and amphibians retain the capacity to regenerate from cardiac damage throughout life (45). And while the adult mammalian myocardium has almost no capacity to refresh the cardiac myocytes lost after injury, it was shown that the early neonatal myocardium has an intrinsic capacity to regenerate. When hearts of 1-day old mice were cryo-injured at the apex, a regenerative response was characterized by proliferation of preexisting cardiomyocytes resulting in minimal formation of fibrotic tissue. This capacity of cardiomyocytes (as opposed to progenitor cells) to proliferate is lost 7 days after birth. This neonatal intrinsic cardiomycte regenerative response is similar to the sustained regenerative capacity of zebrafish hearts (46, 47).

Pluripotent embryonic stem cells as model systems for cardiac development

The capacity of embryonic stem cell (ESC) lines to differentiate in vitro and to recapitulate many of the in vivo developmental programs provides an attractive model system for studying lineage commitment (Figure 1). Significantly, ESC in vitro differentiation can be scaled up to generate large numbers of cardiac progenitors or myocytes.

Major challenges for the use of pluripotent stem cells in cardiac tissue regeneration has been the isolation of large numbers of cardiac progenitors from the heterogeneous products of ESC in vitro differentiation, robustly controlling cardiac lineage differentiation and purifying of differentiated cardiomyocytes. Recently, purified populations of cells that express Isl1 and the VEGF Receptor (KDR) have been shown to give rise to endothelial, smooth muscle, and cardiac muscle cells of the SHF (52, 68, 71). Similarly, the cardiac-specific Nkx2.5 enhancer has been used to isolate bipotential progenitors from murine embryos as well as murine ESCs (72), and the mesoderm marker Brachyury T in combination with a VEGF Receptor cell surface marker (Flk1/KDR) was used to successfully isolate multipotent cardiac progenitors from human and murine ESCs (67, 68).

Unlike Isl1+ progenitors, both Nkx2.5+ and Flk1+ progenitors likely represent a heterogeneous mix of FHF and SHF progenitors. In order to distinguish between these two progenitor populations, the cardiac specific enhancer of the Nkx2.5 gene driving the expression of green fluorescent protein (eGFP) along with a SHF specific enhancer of the Mef2C gene driving the expression of red fluorescent protein (dsRed), were used to generate a double color murine transgenic system (56). For the first time, this allowed for the isolation of purified populations of FHF and SHF cardiac progenitors. A subset of these SHF progenitors appeared to be completely committed to the ventricular myogenic cell fate and at the same time be capable of limited expansion prior to differentiation.

Current understanding of the molecular pathways that control in vivo cardiogenesis have facilitated the development of several different approaches for in vitro directed differentiation of pluripotent stem cells toward the cardiac cell fate. These approaches have largely relied on varying the timing of signaling proteins and small molecules to yield higher numbers of cardiac lineage committed cells. The Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway, for example, has a biphasic role during differentiation. Early developmental stage Wnt signaling, via Wnt3a and GSK-3-inhibition, and late stage down regulation, via Dkk1, are associated with enhanced cardiac differentiation (73). Similarly, a recent report demonstrates that stage specific Activin A/Nodal and BMP4 signaling may direct early cardiac mesoderm specification and late cardiac myocyte differentiation (70). Related directed differentiation approaches have relied on small non-coding regulatory micro-RNAs (miRNAs). In mouse and human miR-1 and -133 have been shown to promote mesoderm formation from ESC, but have opposing functions during further differentiation into cardiac muscle progenitors (74). Further cardiomyocyte differentiation of ESCs or cardiac derived stem cells can be improved through the overexpression of miR-1 and miR-499 (75, 76). Despite these advances in promoting cardiac differentiation from ESC, cell line specific optimization of the concentration and timing of signaling molecules remains essential for successful directed differentiation. In addition to ESC-derivates, the isolation of parthenogenetic (uniparental parthernodes) stem cells (PSCs) derived from murine oocytes forms a potential source of autologous pluripotent stem cells (77, 78). In a recent report, oocyte-derived PSCs were efficiently differentiated into beating cardiomyocytes, and subsequently applied in pre-clinical cardiac regenerative approaches (79). Future work on PSCs should aim to translate ESC findings for humans in an autologous manner.

Induced pluripotent stem cells and direct reprogramming

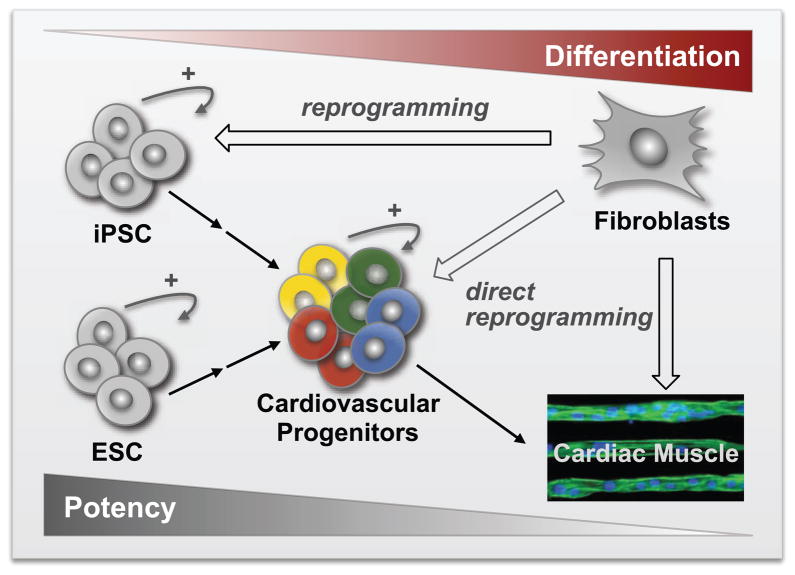

Until recently, the derivation of a pluripotent stem cell line was thought to require the use of discarded embryos from fertility treatment. Remarkably, by the introduction of only four factors (Oct3/4, Sox2, Klf4, and c-Myc) into mouse and human embryonic fibroblasts, successfully generated induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) lines that showed features similar to normal ESCs (Figure 2) (80, 81). In a similar approaches, it has now also been possible to generate iPS cells by the expression of specific non-coding regulatory miRNAs (82), synthetic modified mRNA (83), purified recombinant proteins (84), whole-cell extracts from ESCs (85) or from genetically engineered HEK293 cells (86). While these types of approaches represent an attractive option for the generation of transgene-free iPSCs, their efficiency remains low. Taken together, these studies point to a novel and evolving approach of generating patient-specific iPSC lines.

Figure 2. Biologic Sources of Cardiac Myocytes for Cardiac Regeneration.

There are several theoretically possible ways of generating cardiac myoctes from patient specific somatic cells (such as skin fibroblasts). First it is possible to reprogram somatic fibroblasts to a pluripotent state and generate iPSC (80, 81). iPSC can then be induced to differentiate into cardiac progenitor cells (such as the unipotent ventricular progenitors (56)) and ultimately into functional cardiac myocytes. Alternatively fibroblasts could be directly reprogrammed into functional cardiac myocytes (87). Finally, fibroblasts could, in principle, be reprogrammed into cardiac progenitor cells that are capable of limited expansion before terminal differentiation.

ESC, Embryonic Stem Cells; CVP, Committed Ventricular Progenitors; iPSC, induced Pluripotent Stem Cells. Capacity for expansion or self-renewal is indicated with a circular arrow and + sign.

The postnatal human heart contains a large pool of fibroblasts. The reprogramming of these cells into functional cardiac myocytes that are electrically and functionally coupled to the normal heart therefore represents an attractive approach for cardiac regeneration. Recent reports have in fact demonstrated the direct reprogramming of mouse somatic cells into ventricular myocytes in vitro (87) and vivo (88, 89), using a vector based approach to overexpress a group of cardiac transcription factors (Gata4, Mef2c, Tbx5 and/or Hand2). Although this early work clearly shows the induction of functional ventricular myocytes from fibroblasts, it remains an rare event (90). Remarkable, this efficiency is enhanced when direct reprogramming occurs in vivo, raising the possibility for clinically useful cardiac regeneration (Figure 2).

III. ESC in Cardiac Regeneration: The early animal experience

The ability of ESC lines to differentiate in vitro into cardiac lineages raised the question of whether these cells and their derivates may be suitable for repairing the injured heart. To assess this possibility, undifferentiated mouse ESCs were transplanted into the hearts of adult mice. ESC transplants did not lead to the generation or engraftment of ESC-derived cardiomyocytes but did lead to teratoma formation within 4 weeks, highlighting an important potential pitfall for the use of pluripotent stem cells in regenerative cardiovascular medicine (91–94). Moreover, the syngenic but not the allogenic mouse ESC transplants were detectable at 8 weeks post-transplantation suggesting that innate host immunity resulted in the rejection of allogenic mouse ESC and their differentiated progeny (94).

This early work underscored several requirements for successful cardiac regeneration: Transplanted cells must be able to survive and differentiate into clinically relevant cell types in vivo, they must be able to undergo electromechanical coupling with the host myocardium, they must lead to measurable functional improvement in myocardial function, and they must not result in teratoma formation, arrhythmias, or other adverse clinical outcomes. Given that undifferentiated ESC satisfied none of these requirements, follow-up experiments explored the use of cardiac-enriched differentiated human ESC. Work from several laboratories demonstrated that the direct intramyocardial injection of such cardiac-enriched human ESC derivatives into rodent hearts resulted in the generation of human ESC-derived myocardial grafts (95–98). However, injection of ESC derivates only transiently improved LV-function (98).

More recent progress has allowed for the isolation of a highly purified population of human cardiomyocytes from human ESC via directed-differentiation and an improvement of the survival of these cells by a pro-survival cocktail that limits cardiomyocyte death after transplantation (99). These improvements allowed for the consistent formation of human ESC-derived myocardial grafts in infracted mouse and rat hearts. The engrafted human myocardium attenuated ventricular dilation and preserved regional and global contractile function after myocardial infarction compared with controls. Thus human ESC-derived cardiomyocytes appear to partially remuscularize myocardial infarcts and augment heart muscle in rodent model systems (98–100). It remains uclear, however, if engrafted ESC-derived cardiomyocytes cause adverse arrhythmic side effects, since both anti-arrhythmic (101) and pro-arrhythmic (102) effects were described for mouse cardiac myocyte grafts in injured mouse hearts. Recent work has demonstrated that human ESC-derived cardiomyocytes engraft in a guinea pig MI model, electromechanically integrate with host myocardium, contract synchronously with host hearts, and significantly reduce the incidence of spontaneous and induced ventricular tachycardia (103). This shows the potential for transplantation of human cardiomyocytes derived from a renewable cell source.

As noted above, clinically meaningful engraftment of transplanted myocardial tissue requires proper electromechanical coupling with the host heart. This in turn requires the formation of the intercalated discs to allow the electrophysiological coupling of transplanted cardiomyocytes to host cardiomyocytes. During normal development, postnatal remodelling and adaptation of the ventricular myocardium to the hemodynamic changes leads to localization of the gap-junctions to the transverse terminals of the cells. This allows for the rapid spread of action potentials necessary for normal cardiac conduction. Adherens-junctions anchor sarcomeric actin filaments between myocytes and are required for correct gap-junction formation (104, 105). Cadherins are an important functional component of these junctions. Transplanted ESC-derived cardiomyocytes did show a pattern of diffuse N-Cadherin (adherens-junction) expression but no Connexin-43 (gap-junction) expression (95, 98).

The in vivo differentiation of hESC-derived myocytes into engrafted tissue points to the promise of pluripotent stem cells for regenerative medicine. Nonetheless, the existing body of literature does not support the hypothesis that the direct intramyocardial injection of cardiogenic cells will result in sarcomeric aligned, fully electromechanically-coupled tissue that can result in long-term improvement in myocardial function. Indeed, current evidence would seem to suggest that augmenting the advances in cell biology with tissue engineering technologies may be necessary to meet these functional requirements.

IV. Generating Myocardium In Vitro: Engineering cardiac tissue

Even optimum cardiogenic cell populations are unlikely to result in mature functional myocardial tissue in the absence of appropriate cellular and sarcomeric alignment. It will therefore be important to define the 3-dimensional structure to guide cell growth, differentiation, and maturation (106). While reconstructing the entire 4-chambered mammalian heart may be difficult, recent advances raise the possibility of engineering specific cardiac components such as ventricular myocardium, heart valves, pacemaker conduction systems, and coronary vasculature. In the future, these heart parts could be used as replacement parts for diseased hearts. Coupled with advances in delivery systems, such a piecemeal approach may provide an alternative to direct cell transplantation (33).

Sources of cardiomyocytes for cell and tissue engineering applications

To date, most attempts at engineering ventricular myocardial tissue have relied on rat neonatal cardiomyocytes as a cell source (Table 2). This is largely due to the wide availability of these cells, and to their capacity to proliferate and differentiate into functional cardiac myocytes ex vivo (107). In the absence of external stimuli, however, the in vitro organizational capacity of neonatal rat cardiomyocytes is limited and does not result in the sarcomeric alignment nor in myofibrillar organization like in myocardium of the native heart (108). While useful for developing novel tissue engineering based platforms for cardiac regeneration, rodent cardiac myocytes will not have a role in cardiac regeneration in humans. It will therefore be necessary to adapt tissue-engineering advances from rodent neonatal cardiac myocytes to cardiac myocytes derived from renewable human patient-specific cell sources.

Table 2.

Recent In Vitro Strategies in Cardiac Cell and Tissue Engineering

| Approach | Results | In vivo Application | Ref | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Engineering | ||||

| Microcontact Printing | Rat neonatal CM/mouse ESC-CVP seeded on patterned on PDMS surface | Strong 2D (<0.1mm) microscopic anisotropic cellular alignment | n/a | (113, 114, 151) |

| Muscular Thin Film | Rat neonatal CM/mouse ESC-CVP seeded on patterned on PDMS thin film | 2D anisotropic alignment, force measurement of contractile thin film | n/a | (56, 115) |

| Tissue Engineering | ||||

| Polymer Scaffold | Rat neonatal CM seeded on laminin/fibronectin/gelatin-coated degradable PLGA polymer scaffold; bioreactor set-up | 3D (1–5mm) organized tissue, macroscopic contraction of constructs | Avascular muscle graft | (119, 120, 123–127) |

| Honeycomb Scaffold | Rat neonatal CM seeded on accordion like honeycomb scaffold, to provide 3D cell alignment | 3D multilayered tissue, macroscopic contraction | Avascular muscle graft | (128) |

| Proangiogenic Scaffold | Chicken/human ESC-CM seeded on pHEMA-co-MAA coated micropore scaffold, to induce in growth in vivo | 3D (0,3 / 0,6mm) bundled CMs, contractile proteins* | Acellular proangiogenic functional template | (150) |

| Cotton Candy Scaffold | Rat neonatal CM grown on a spanned out sucrose PLGA coated scaffold | 3D configuration, improved macroscopic contraction | Avascular muscle graft | (130) |

| Cell Sheet | Combining single layers of neonatal rat cultured CM on temperature related de-attachable PNIPA polymer surfaces | 3D (≈0,1–0,2mm) multilayered pulsatile tissue | Avascular multilayered graft | (131) |

| Myotubular Cell Sheet | Wrapping of single layers of neonatal rat CM Cell Sheets** on a sticky fibrogen roller to create 6 cell layer thick tissue | 3D configuration, macroscopic contracting tube / vessel-like | Circulatory support device | (133, 134) |

| Hydrogel Ring Technique | Rat neonatal CM / chick embryonic CM / mouse ESC-CM cultured in circular mold containing hydrogel (collagen type I + matrigel); training of rings via cyclic stretch (8–10%, 0,5–2Hz) | 3D (0,1–0,8mm) circular isotropic alignment, homogeneous contractions | Avascular muscle graft | (107, 137, 142, 152) |

| Hydrogel Pouch Technique | Rat neonatal CM on a spherical hydrogel (collagen type I + matrigel) mold; subjection of pouch to auxotonic stretch | Auxotonic alignment and contracting of pouch | Avascular graft Bio VAD | (140) |

| Vascularized Tissue | ||||

| Decellularized Heart | Decellularization of cadaveric heart; re-seeding of neonatal rat CM and endothelial cells via perfusion of matrix in a Langendorf set-up | 3D (0,5–1mm), LVEF 2% of a rat adult heart | Whole bioartificial organ | (143) |

| Multicellular Scaffold | Multiple cell types (human ESC-CM and fibroblasts) on a mixed PGLA and PLLA (1:1) polymer scaffold | 3D (0,2–0,6mm) macroscopic contraction, vascularization | Vascularized muscle graft | (146) |

| Multicellular Patch | Adhesion of human and mouse cell sources (Human ESC-CM, HUVECS and mouse embryonic fibroblasts) in low attachment plates to form patches | 3D Beating vascularized tissue, in vivo anastomosis | Vascularized muscle graft | (147) |

ESC-CM, embryonic stem cell derived cardiac myocytes; CVP, committed ventricular progenitors; 2D, 2-dimensional; 3D, 3-dimensional; HUVEC, human umbilical vein endothelial cells; Bio VAD, biological ventricular assist device; PDMS, Polydimethylsiloxane; PLGA, polylactic-glycolic acid; pHEMA-co-MAA, poly(2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate-co-methacrylic acid); PLLA, poly-L-lactic acid; PNIPA, poly(N-isopropylacrylamide); MTF, muscular thin film; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; n/a, not applicable.

Abundance of cytoplasmic troponin T and β-myosin heavy chain protein.

Same technique used for the cell layers as in the Cell Sheet approach.

2-Dimensional cell engineering

The emergence of micro-fabrication and micropatterning techniques in the early 1990's, allowed for novel cell engineering approaches to investigate of the interaction between cell shape and function (109–111). Photolithography was initially used to generate cell culture surfaces with alternating lines of high and low cell-adhesion potential (112). This approach was refined by micro-contact printing techniques that allowed extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins to be imprinted on a polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) coated surface. This allowed for electromechanical coupling between cardiac myocytes and the generation of anisotropic cardiac tissue (113, 114).

In a powerful proof-of-principle series of experiments, it was demonstrated that it is possible to manipulate cell shape and 2-dimensional myofibrillar organization of rat cardiomyocytes by culturing them on PDMS thin films micro-patterned with fibronectin in specific shapes such as triangles, rectangles, and star shapes. These constructs, called muscular thin films (MTF), adopted functional, 3-dimensional conformations when released from the temperature responsive polymer poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) (PIPAAm) (115). This work demonstrated that there is a direct correlation between sarcomeric alignment, force generation, and work performed.

As discussed above, recent advances have allowed for the isolation of so-called mouse ESC- derived ventricular progenitors (56). When the ventricular progenitors were cultured on micropatterned lines of fibronectin, their differentiated progeny aligned spontaneously to form anisotropic 2-dimensional myocardial tissue with uniaxial sarcomeric alignment (115). Of great importance is the finding that the generation of force generating 2-dimensional myocardial tissue was only possible from cells that were completely committed to the ventricular cell fate, underscoring the importance of isolating highly purified populations of ventricular progenitors for the generation of tissue engineering constructs (56).

Biodegradable scaffolds

Although micro-patterning approaches have been used to promote cellular alignment and generate 2-dimensional muscular constructs, they have not yet been successfully used to generate the 3-dimensional constructs required for adequate force generation. In order to overcome this barrier, a number of laboratories have attempted to use biodegradable scaffolds to generate 3-dimensional cardiac tissue (116–118). Early efforts focused on the generation of disk-shaped poly(lactic-co-glycolic) acid (PLGA) scaffolds that could serve as a 3-dimensional substrate for cell adhesion in vitro and, at the same time, could be gradually absorbed in vivo (119, 120). PLGA is metabolized into glycolic acid monomers and these have been shown to stimulate collagen synthesis (121, 122). PLGA scaffolds were coated with ECM proteins such as laminin (123), gelatin (124, 125) and collagen (126) and seeded with rat neonatal cardiac myocytes. This resulted 3-dimensional multilayered (1–5 millimeter thickness) cardiomyocyte tissue within one week of implantation of (119, 120, 126). Electrophysiological studies revealed local functional coupling and alignment by cellularity, conduction velocity, signal amplitude, capture rate, and excitation threshold measurements of PLGA scaffold based constructs (123). When electrically stimulated for extended periods of time, the PLGA constructs had improved tissue morphology and contractile function compared to non-stimulated controls (127). Subcutaneous implanted engineered tissue survived and formed beating vascularized grafts. Engraftment upon 3 week old cardiac cryoinjury scars showed a 5 week survival of patches (124).

In a similar series of experiments, an accordion-like honeycomb scaffold was designed to replicate the structural and mechanical properties of the native heart (128). A specific pore micro-architecture design of the scaffold generated directionally dependent structural and mechanical properties. The mechanical properties of these scaffolds were shown to closely match those of native heart tissue: the scaffold was stiffer when stretched circumferentially as compared to longitudinally (116, 117, 128). Although the scaffold provided mechanical anisotropy, it resulted in more isolated compartments of myocytes that were not electrically coupled over the whole construct. In addition, the bioreactor culture conditions did provide improved oxygenation, but the absence of vasculature of the new tissue dictated an upper limit on the thickness of the 3-dimensional tissue (126, 129).

Further steps in the field were made with the so called "cotton-candy technique". Sucrose was melted in a cotton candy machine, spun out to an optimum fiber length and thickness, and coated with a fibronectin-PLGA polymer. Cardiac myocytes cultured on this substrate aligned into unidirectional 3-dimensional tissue with macroscopic anisotropy (130).

Cell Sheets

In an effort to fabricate 3-dimensional pulsatile cardiac grafts without the use of scaffolds, a novel technology that layers cell sheets 3-dimensionally was developed. Rat cardiomyocytes were cultured on a polystyrene surface coated with the temperature-responsive polymer PIPAAm. When the cultured cells had coalesced into a confluent layer, the temperature was reduced thereby detaching the cardiac myocytes as a thin cell sheet without the scaffold backbone. Multiple sheets were then overlaid to generate 3-dimensional heart muscle constructs (131, 132). These constructs became electrically coupled via connexin-43 and began to pulse simultaneously (133–135). Although conceptually appealing, at this point it remains unclear as to whether these constructs can be engineered to replicate the 3-dimensional organization of the native heart.

Hydrogels

An alternate approach for the fabrication of myocardial tissue consists of culturing cardiac myocytes in hydrogels consisting of extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins to provide the 3- dimensional environment for cell growth. Rat neonatal cardiomyocytes were cultured in circular hydrogel molds to generate spontaneously contracting muscular rings that could be attached directly to mechanical force transducers (136, 137). Interestingly, cyclical stretch of these engineered heart muscle rings resulted in myocyte hypertrophy and increased force generation (137–142). Similarly, when electrically stimulated for extended periods of time cardiac muscle constructs had improved tissue morphology and contractile function compared to non-stimulated controls (127). Thus, it appears that both electric stimulation and mechanical stretch may be able to improve cardiac myocyte function although at this point it is unclear whether this occurs through the same or related pathways.

Bioartificial Hearts

Perhaps the most ambitious approach to date involves the generation of a bioartificial hearts. This approach has the tremendous appeal of capitalizing on the intrinsic 3-dimensional architecture of the native heart (143). Rat hearts were decellularized by the infusion of the coronary vasculature with detergents resulting in an acellular perfusable natural scaffold for cell culture. These natural scaffolds were then reseeded with rat neonatal heart cells and within 1-week after reseeding, macroscopic contractions were visible, and constructs could generate force equivalent to approximately 2% of adult hearts. An important limitation of this approach, was the failure of the re-seeded cardiomyocytes to completely recapitulate the micro architecture of the native heart (143). Nonetheless, the successful decellularization of porcine hearts raises the intriguing possibility that such an approach may yet be adapted to the treatment of human disease (144, 145).

Human cardiac myocytes in tissue engineering

Until recently, the use of human cardiac myocytes to generate tissue engineered myocardial tissue has been hindered by the lack of renewable sources of human cardiomyocytes. Initial attempts focused on the generation of synchronously contracting myocardial tissue from human embryonic stem cells containing endothelial vessel networks (146). In a related series of experiments, human ESCs were differentiated to cardiomyocytes and cultured with endothelial cells, and fibroblasts in a rotating orbital shaker to create vascularized human cardiac tissue patches. Implantation of these patches resulted in better cell grafts compared with patches composed only of cardiomyocytes (147). When cardiac derived stem cells were combined with bio-printing technology it increased expression of the cardiac genes in the 3-dimensional macroscopic generated tissue (148). In addition, when cultured in a 3-dimensional collagen matrix, uniaxial mechanical stress conditioning promoted myofibrillogenesis, sarcomeric banding, and cardiomyocyte matrix fiber alignment. Furthermore, the addition of endothelial cells markedly increased proliferation of myocytes by 20%. Thus, controlling the mechanical load as well as vascular cell contact will be necessary for engineering human myocardium (149).

In order to promote 3-dimensional cardiomyocyte alignment microtemplating techniques were used to micropattern a poly(2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate-co-methacrylic acid) (pHEMA-co-MAA) based hydrogel to generate tissue-engineering scaffolds. The constructs contained parallel channels designed to augment the formation of aligned cardiomyocyte bundles, supported by spherical interconnected pores intended to enhance angiogenesis and reduce scar formation. Cardiomyocytes survived for about 2 weeks in vitro on these scaffolds and proliferated to approximate the cell densities of the adult heart. Implantation of acellular pore scaffolds resulted in angiogenesis as well as a reduced fibrotic response (150). The advances made in human cardiac tissue engineering illustrate the potential for novel cardiac regenerative therapies. Future work should attempt to unravel what cues are necessary to design heart tissue meeting the functional properties and electromechanical requirements for permanent engraftment in native myocardium.

V. From Here to There: Combining stem cell biology and tissue engineering technology

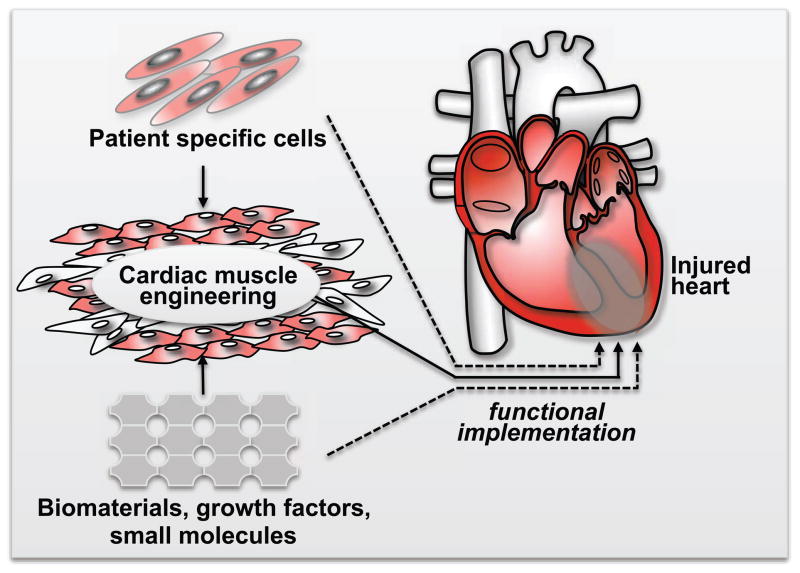

Thus, despite nearly a decade of intensive research and millions of dollars of public money, at this point in time there is no clinically accepted therapy aimed at replacing the loss of functional cardiac myocytes and repairing failing myocardial tissue. Many hurdles remain, including the isolation of committed ventricular progenitors from patient specific cell sources, the differentiation and assembly of these progenitors into 3-dimensional myocardial tissue with sufficient mass to achieve hemodynamically significant force generation, the production of an adequate blood supply for this tissue, and the electrical coupling of the tissue to the native myocardium (figure 3). Nonetheless, the recent advances in stem cell biology when coupled to the remarkable progress in tissue engineering technology, point to a powerful emerging approach for regenerative cardiovascular medicine.

Figure 3. Schematic Representation of Potential Clinical Ways of Combining Stem Cell Biology with Cardiac Tissue Engineering in Order to Repair the Injured Myocardium.

Patient specific cells, like iPSC (described in section II above) or their derivates can be combined with tissue engineering technologies (described in section IV) to generate functional cardiac muscle patches. These patches could then be transplanted into injured hearts for cardiac regeneration. Such patches will need to be functionally integrated into the injured native myocardium or alternatively to function as biological ventricular assist devices. In principle, it may be possible to implant of a cellular biomaterials that could be then seeded by cells from the native myocardium. Alternatively it may be possible to inject patient specific cardiac myocytes in the hopes of electrical and functional integration with the native myocardium. Defining the optimum strategy for cardiac regeneration (including the role of patient specific cells and biomaterials) remains a key objective for cardiac regenerative therapy.

iPSC, induced Pluripotent Stem Cells; CVP, Committed Ventricular Progenitors; CM, cardiac myocytes.

References

- 1.Lloyd-Jones DM, Leip EP, Larson MG, D’Agostino RB, Beiser A, Wilson PW, Wolf PA, Levy D. Prediction of lifetime risk for cardiovascular disease by risk factor burden at 50 years of age. Circulation. 2006;113:791–798. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.548206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Levy D, Kenchaiah S, Larson MG, Benjamin EJ, Kupka MJ, Ho KK, Murabito JM, Vasan RS. Long-term trends in the incidence of and survival with heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1397–1402. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ford ES, Ajani UA, Croft JB, Critchley JA, Labarthe DR, Kottke TE, Giles WH, Capewell S. Explaining the decrease in U.S. deaths from coronary disease, 1980–2000. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:2388–2398. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa053935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.De Boer RA, Pinto YM, Van Veldhuisen DJ. The imbalance between oxygen demand and supply as a potential mechanism in the pathophysiology of heart failure: the role of microvascular growth and abnormalities. Microcirculation. 2003;10:113–126. doi: 10.1038/sj.mn.7800188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dickstein K, Vardas PE, Auricchio A, Daubert JC, Linde C, McMurray J, Ponikowski P, Priori SG, Sutton R, van Veldhuisen DJ. 2010 focused update of ESC Guidelines on device therapy in heart failure: an update of the 2008 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure and the 2007 ESC Guidelines for cardiac and resynchronization therapy. Developed with the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association and the European Heart Rhythm Association. Eur J Heart Fail. 2010;12:1143–1153. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfq192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Assmus B, Schachinger V, Teupe C, Britten M, Lehmann R, Dobert N, Grunwald F, Aicher A, Urbich C, Martin H, et al. Transplantation of Progenitor Cells and Regeneration Enhancement in Acute Myocardial Infarction (TOPCARE-AMI) Circulation. 2002;106:3009–3017. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000043246.74879.cd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wollert KC, Meyer GP, Lotz J, Ringes-Lichtenberg S, Lippolt P, Breidenbach C, Fichtner S, Korte T, Hornig B, Messinger D, et al. Intracoronary autologous bone-marrow cell transfer after myocardial infarction: the BOOST randomised controlled clinical trial. Lancet. 2004;364:141–148. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16626-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schachinger V, Erbs S, Elsasser A, Haberbosch W, Hambrecht R, Holschermann H, Yu J, Corti R, Mathey DG, Hamm CW, et al. Intracoronary bone marrow-derived progenitor cells in acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1210–1221. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa060186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meyer GP, Wollert KC, Lotz J, Pirr J, Rager U, Lippolt P, Hahn A, Fichtner S, Schaefer A, Arseniev L, et al. Intracoronary bone marrow cell transfer after myocardial infarction: 5-year follow-up from the randomized-controlled BOOST trial. Eur Heart J. 2009;30:2978–2984. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tendera M, Wojakowski W, Ruzyllo W, Chojnowska L, Kepka C, Tracz W, Musialek P, Piwowarska W, Nessler J, Buszman P, et al. Intracoronary infusion of bone marrow-derived selected CD34+CXCR4+ cells and non-selected mononuclear cells in patients with acute STEMI and reduced left ventricular ejection fraction: results of randomized, multicentre Myocardial Regeneration by Intracoronary Infusion of Selected Population of Stem Cells in Acute Myocardial Infarction (REGENT) Trial. Eur Heart J. 2009;30:1313–1321. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Janssens S, Dubois C, Bogaert J, Theunissen K, Deroose C, Desmet W, Kalantzi M, Herbots L, Sinnaeve P, Dens J, et al. Autologous bone marrow-derived stem-cell transfer in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: double-blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2006;367:113–121. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67861-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lunde K, Solheim S, Aakhus S, Arnesen H, Abdelnoor M, Egeland T, Endresen K, Ilebekk A, Mangschau A, Fjeld JG, et al. Intracoronary injection of mononuclear bone marrow cells in acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1199–1209. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hirsch A, Nijveldt R, van der Vleuten PA, Tijssen JG, van der Giessen WJ, Tio RA, Waltenberger J, Ten Berg JM, Doevendans PA, Aengevaeren WR, et al. Intracoronary infusion of mononuclear cells from bone marrow or peripheral blood compared with standard therapy in patients after acute myocardial infarction treated by primary percutaneous coronary intervention: results of the randomized controlled HEBE trial. Eur Heart J. 2011 doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Traverse JH, Henry TD, Ellis SG, Pepine CJ, Willerson JT, Zhao DX, Forder JR, Byrne BJ, Hatzopoulos AK, Penn MS, et al. Effect of intracoronary delivery of autologous bone marrow mononuclear cells 2 to 3 weeks following acute myocardial infarction on left ventricular function: the LateTIME randomized trial. JAMA. 2011;306:2110–2119. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Traverse JH, Henry TD, Pepine CJ, Willerson JT, Zhao DX, Ellis SG, Forder JR, Anderson RD, Hatzopoulos AK, Penn MS, et al. Effect of the use and timing of bone marrow mononuclear cell delivery on left ventricular function after acute myocardial infarction: the TIME randomized trial. JAMA. 2012;308:2380–2389. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.28726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Perin EC, Willerson JT, Pepine CJ, Henry TD, Ellis SG, Zhao DX, Silva GV, Lai D, Thomas JD, Kronenberg MW, et al. Effect of transendocardial delivery of autologous bone marrow mononuclear cells on functional capacity, left ventricular function, and perfusion in chronic heart failure: the FOCUS-CCTRN trial. JAMA. 2012;307:1717–1726. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Strauer BE, Yousef M, Schannwell CM. The acute and long-term effects of intracoronary Stem cell Transplantation in 191 patients with chronic heARt failure: the STAR-heart study. Eur J Heart Fail. 2010;12:721–729. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfq095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jeevanantham V, Butler M, Saad A, Abdel-Latif A, Zuba-Surma EK, Dawn B. Adult bone marrow cell therapy improves survival and induces long-term improvement in cardiac parameters: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Circulation. 2012;126:551–568. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.086074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gnecchi M, Zhang Z, Ni A, Dzau VJ. Paracrine mechanisms in adult stem cell signaling and therapy. Circ Res. 2008;103:1204–1219. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.176826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kamihata H, Matsubara H, Nishiue T, Fujiyama S, Amano K, Iba O, Imada T, Iwasaka T. Improvement of collateral perfusion and regional function by implantation of peripheral blood mononuclear cells into ischemic hibernating myocardium. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2002;22:1804–1810. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.0000039168.95670.b9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hsieh PC, Segers VF, Davis ME, MacGillivray C, Gannon J, Molkentin JD, Robbins J, Lee RT. Evidence from a genetic fate-mapping study that stem cells refresh adult mammalian cardiomyocytes after injury. Nat Med. 2007;13:970–974. doi: 10.1038/nm1618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Loffredo FS, Steinhauser ML, Gannon J, Lee RT. Bone marrow-derived cell therapy stimulates endogenous cardiomyocyte progenitors and promotes cardiac repair. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;8:389–398. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2011.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Malliaras K, Zhang Y, Seinfeld J, Galang G, Tseliou E, Cheng K, Sun B, Aminzadeh M, Marban E. Cardiomyocyte proliferation and progenitor cell recruitment underlie therapeutic regeneration after myocardial infarction in the adult mouse heart. EMBO Mol Med. 2012;5:191–209. doi: 10.1002/emmm.201201737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mohsin S, Siddiqi S, Collins B, Sussman MA. Empowering adult stem cells for myocardial regeneration. Circ Res. 2011;109:1415–1428. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.243071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Psaltis PJ, Zannettino AC, Worthley SG, Gronthos S. Concise review: mesenchymal stromal cells: potential for cardiovascular repair. Stem Cells. 2008;26:2201–2210. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2008-0428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rose RA, Jiang H, Wang X, Helke S, Tsoporis JN, Gong N, Keating SC, Parker TG, Backx PH, Keating A. Bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stromal cells express cardiac-specific markers, retain the stromal phenotype, and do not become functional cardiomyocytes in vitro. Stem Cells. 2008;26:2884–2892. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2008-0329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Williams AR, Hare JM. Mesenchymal stem cells: biology, pathophysiology, translational findings, and therapeutic implications for cardiac disease. Circ Res. 2011;109:923–940. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.243147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen SL, Fang WW, Ye F, Liu YH, Qian J, Shan SJ, Zhang JJ, Chunhua RZ, Liao LM, Lin S, et al. Effect on left ventricular function of intracoronary transplantation of autologous bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 2004;94:92–95. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2004.03.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hare JM, Traverse JH, Henry TD, Dib N, Strumpf RK, Schulman SP, Gerstenblith G, DeMaria AN, Denktas AE, Gammon RS, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-escalation study of intravenous adult human mesenchymal stem cells (prochymal) after acute myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:2277–2286. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.06.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hare JM, Fishman JE, Gerstenblith G, DiFede Velazquez DL, Zambrano JP, Suncion VY, Tracy M, Ghersin E, Johnston PV, Brinker JA, et al. Comparison of allogeneic vs autologous bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells delivered by transendocardial injection in patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy: the POSEIDON randomized trial. JAMA. 2012;308:2369–2379. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.25321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bearzi C, Rota M, Hosoda T, Tillmanns J, Nascimbene A, De Angelis A, Yasuzawa-Amano S, Trofimova I, Siggins RW, Lecapitaine N, et al. Human cardiac stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:14068–14073. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706760104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Goumans MJ, de Boer TP, Smits AM, van Laake LW, van Vliet P, Metz CH, Korfage TH, Kats KP, Hochstenbach R, Pasterkamp G, et al. TGF-beta1 induces efficient differentiation of human cardiomyocyte progenitor cells into functional cardiomyocytes in vitro. Stem Cell Res. 2007;1:138–149. doi: 10.1016/j.scr.2008.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Messina E, De Angelis L, Frati G, Morrone S, Chimenti S, Fiordaliso F, Salio M, Battaglia M, Latronico MV, Coletta M, et al. Isolation and expansion of adult cardiac stem cells from human and murine heart. Circ Res. 2004;95:911–921. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000147315.71699.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Makkar RR, Smith RR, Cheng K, Malliaras K, Thomson LE, Berman D, Czer LS, Marban L, Mendizabal A, Johnston PV, et al. Intracoronary cardiosphere-derived cells for heart regeneration after myocardial infarction (CADUCEUS): a prospective, randomised phase 1 trial. Lancet. 2012;379:895–904. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60195-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bolli R, Chugh AR, D’Amario D, Loughran JH, Stoddard MF, Ikram S, Beache GM, Wagner SG, Leri A, Hosoda T, et al. Cardiac stem cells in patients with ischaemic cardiomyopathy (SCIPIO): initial results of a randomised phase 1 trial. Lancet. 2011;378:1847–1857. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61590-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 36.Chugh AR, Beache GM, Loughran JH, Mewton N, Elmore JB, Kajstura J, Pappas P, Tatooles A, Stoddard MF, Lima JA, et al. Administration of cardiac stem cells in patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy: the SCIPIO trial: surgical aspects and interim analysis of myocardial function and viability by magnetic resonance. Circulation. 2012;126:S54–64. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.092627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Menasche P. Cardiac cell therapy: lessons from clinical trials. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2011;50:258–265. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2010.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Menasche P. Skeletal myoblasts and cardiac repair. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2008;45:545–553. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2007.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dib N, Michler RE, Pagani FD, Wright S, Kereiakes DJ, Lengerich R, Binkley P, Buchele D, Anand I, Swingen C, et al. Safety and feasibility of autologous myoblast transplantation in patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy: four-year follow-up. Circulation. 2005;112:1748–1755. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.547810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gavira JJ, Herreros J, Perez A, Garcia-Velloso MJ, Barba J, Martin-Herrero F, Canizo C, Martin-Arnau A, Marti-Climent JM, Hernandez M, et al. Autologous skeletal myoblast transplantation in patients with nonacute myocardial infarction: 1-year follow-up. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2006;131:799–804. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2005.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hagege AA, Marolleau JP, Vilquin JT, Alheritiere A, Peyrard S, Duboc D, Abergel E, Messas E, Mousseaux E, Schwartz K, et al. Skeletal myoblast transplantation in ischemic heart failure: long-term follow-up of the first phase I cohort of patients. Circulation. 2006;114:I108–113. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.000521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Siminiak T, Kalawski R, Fiszer D, Jerzykowska O, Rzezniczak J, Rozwadowska N, Kurpisz M. Autologous skeletal myoblast transplantation for the treatment of postinfarction myocardial injury: phase I clinical study with 12 months of follow-up. Am Heart J. 2004;148:531–537. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2004.03.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Menasche P, Alfieri O, Janssens S, McKenna W, Reichenspurner H, Trinquart L, Vilquin JT, Marolleau JP, Seymour B, Larghero J, et al. The Myoblast Autologous Grafting in Ischemic Cardiomyopathy (MAGIC) trial: first randomized placebo-controlled study of myoblast transplantation. Circulation. 2008;117:1189–1200. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.734103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Senyo SE, Steinhauser ML, Pizzimenti CL, Yang VK, Cai L, Wang M, Wu TD, Guerquin-Kern JL, Lechene CP, Lee RT. Mammalian heart renewal by pre-existing cardiomyocytes. Nature. 2013;493:433–436. doi: 10.1038/nature11682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Poss KD, Wilson LG, Keating MT. Heart regeneration in zebrafish. Science. 2002;298:2188–2190. doi: 10.1126/science.1077857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jopling C, Sleep E, Raya M, Marti M, Raya A, Izpisua Belmonte JC. Zebrafish heart regeneration occurs by cardiomyocyte dedifferentiation and proliferation. Nature. 2010;464:606–609. doi: 10.1038/nature08899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kikuchi K, Holdway JE, Werdich AA, Anderson RM, Fang Y, Egnaczyk GF, Evans T, Macrae CA, Stainier DY, Poss KD. Primary contribution to zebrafish heart regeneration by gata4(+) cardiomyocytes. Nature. 2010;464:601–605. doi: 10.1038/nature08804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Buckingham M, Meilhac S, Zaffran S. Building the mammalian heart from two sources of myocardial cells. Nat Rev Genet. 2005;6:826–835. doi: 10.1038/nrg1710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Martin-Puig S, Wang Z, Chien KR. Lives of a heart cell: tracing the origins of cardiac progenitors. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;2:320–331. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Laugwitz KL, Moretti A, Caron L, Nakano A, Chien KR. Islet1 cardiovascular progenitors: a single source for heart lineages? Development. 2008;135:193–205. doi: 10.1242/dev.001883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Laugwitz KL, Moretti A, Lam J, Gruber P, Chen Y, Woodard S, Lin LZ, Cai CL, Lu MM, Reth M, et al. Postnatal isl1+ cardioblasts enter fully differentiated cardiomyocyte lineages. Nature. 2005;433:647–653. doi: 10.1038/nature03215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Moretti A, Caron L, Nakano A, Lam JT, Bernshausen A, Chen Y, Qyang Y, Bu L, Sasaki M, Martin-Puig S, et al. Multipotent embryonic isl1+ progenitor cells lead to cardiac, smooth muscle, and endothelial cell diversification. Cell. 2006;127:1151–1165. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cai CL, Liang X, Shi Y, Chu PH, Pfaff SL, Chen J, Evans S. Isl1 identifies a cardiac progenitor population that proliferates prior to differentiation and contributes a majority of cells to the heart. Dev Cell. 2003;5:877–889. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00363-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mori AD, Zhu Y, Vahora I, Nieman B, Koshiba-Takeuchi K, Davidson L, Pizard A, Seidman JG, Seidman CE, Chen XJ, et al. Tbx5-dependent rheostatic control of cardiac gene expression and morphogenesis. Dev Biol. 2006;297:566–586. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Moskowitz IP, Pizard A, Patel VV, Bruneau BG, Kim JB, Kupershmidt S, Roden D, Berul CI, Seidman CE, Seidman JG. The T-Box transcription factor Tbx5 is required for the patterning and maturation of the murine cardiac conduction system. Development. 2004;131:4107–4116. doi: 10.1242/dev.01265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Domian IJ, Chiravuri M, van der Meer P, Feinberg AW, Shi X, Shao Y, Wu SM, Parker KK, Chien KR. Generation of functional ventricular heart muscle from mouse ventricular progenitor cells. Science. 2009;326:426–429. doi: 10.1126/science.1177350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bu L, Jiang X, Martin-Puig S, Caron L, Zhu S, Shao Y, Roberts DJ, Huang PL, Domian IJ, Chien KR. Human ISL1 heart progenitors generate diverse multipotent cardiovascular cell lineages. Nature. 2009;460:113–117. doi: 10.1038/nature08191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gessert S, Kuhl M. The multiple phases and faces of wnt signaling during cardiac differentiation and development. Circ Res. 2010;107:186–199. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.221531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tzahor E. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling and cardiogenesis: timing does matter. Dev Cell. 2007;13:10–13. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kwon C, Arnold J, Hsiao EC, Taketo MM, Conklin BR, Srivastava D. Canonical Wnt signaling is a positive regulator of mammalian cardiac progenitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:10894–10899. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704044104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lin L, Cui L, Zhou W, Dufort D, Zhang X, Cai CL, Bu L, Yang L, Martin J, Kemler R, et al. Beta-catenin directly regulates Islet1 expression in cardiovascular progenitors and is required for multiple aspects of cardiogenesis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104:9313–9318. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700923104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Qyang Y, Martin-Puig S, Chiravuri M, Chen S, Xu H, Bu L, Jiang X, Lin L, Granger A, Moretti A, et al. The renewal and differentiation of Isl1+ cardiovascular progenitors are controlled by a Wnt/beta-catenin pathway. Cell Stem Cell. 2007;1:165–179. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Dong J, Feldmann G, Huang J, Wu S, Zhang N, Comerford SA, Gayyed MF, Anders RA, Maitra A, Pan D. Elucidation of a universal size-control mechanism in Drosophila and mammals. Cell. 2007;130:1120–1133. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.07.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Heallen T, Zhang M, Wang J, Bonilla-Claudio M, Klysik E, Johnson RL, Martin JF. Hippo pathway inhibits Wnt signaling to restrain cardiomyocyte proliferation and heart size. Science. 2011;332:458–461. doi: 10.1126/science.1199010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.von Gise A, Lin Z, Schlegelmilch K, Honor LB, Pan GM, Buck JN, Ma Q, Ishiwata T, Zhou B, Camargo FD, et al. YAP1, the nuclear target of Hippo signaling, stimulates heart growth through cardiomyocyte proliferation but not hypertrophy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:2394–2399. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1116136109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Xin M, Kim Y, Sutherland LB, Qi X, McAnally J, Schwartz RJ, Richardson JA, Bassel-Duby R, Olson EN. Regulation of insulin-like growth factor signaling by Yap governs cardiomyocyte proliferation and embryonic heart size. Sci Signal. 2011;4:ra70. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2002278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yang L, Soonpaa MH, Adler ED, Roepke TK, Kattman SJ, Kennedy M, Henckaerts E, Bonham K, Abbott GW, Linden RM, et al. Human cardiovascular progenitor cells develop from a KDR+ embryonic-stem-cell-derived population. Nature. 2008;453:524–528. doi: 10.1038/nature06894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kattman SJ, Huber TL, Keller GM. Multipotent flk-1+ cardiovascular progenitor cells give rise to the cardiomyocyte, endothelial, and vascular smooth muscle lineages. Dev Cell. 2006;11:723–732. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Adler ED, Chen VC, Bystrup A, Kaplan AD, Giovannone S, Briley-Saebo K, Young W, Kattman S, Mani V, Laflamme M, et al. The cardiomyocyte lineage is critical for optimization of stem cell therapy in a mouse model of myocardial infarction. FASEB J. 2009 doi: 10.1096/fj.09-135426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kattman SJ, Witty AD, Gagliardi M, Dubois NC, Niapour M, Hotta A, Ellis J, Keller G. Stage-specific optimization of activin/nodal and BMP signaling promotes cardiac differentiation of mouse and human pluripotent stem cell lines. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;8:228–240. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wu SM, Fujiwara Y, Cibulsky SM, Clapham DE, Lien CL, Schultheiss TM, Orkin SH. Developmental origin of a bipotential myocardial and smooth muscle cell precursor in the mammalian heart. Cell. 2006;127:1137–1150. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wu SM, Chien KR, Mummery C. Origins and fates of cardiovascular progenitor cells. Cell. 2008;132:537–543. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Naito AT, Shiojima I, Akazawa H, Hidaka K, Morisaki T, Kikuchi A, Komuro I. Developmental stage-specific biphasic roles of Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in cardiomyogenesis and hematopoiesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:19812–19817. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605768103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ivey KN, Muth A, Arnold J, King FW, Yeh RF, Fish JE, Hsiao EC, Schwartz RJ, Conklin BR, Bernstein HS, et al. MicroRNA regulation of cell lineages in mouse and human embryonic stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;2:219–229. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wilson KD, Hu S, Venkatasubrahmanyam S, Fu JD, Sun N, Abilez OJ, Baugh JJ, Jia F, Ghosh Z, Li RA, et al. Dynamic microRNA expression programs during cardiac differentiation of human embryonic stem cells: role for miR-499. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2010;3:426–435. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.109.934281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sluijter JP, van Mil A, van Vliet P, Metz CH, Liu J, Doevendans PA, Goumans MJ. MicroRNA-1 and -499 regulate differentiation and proliferation in human-derived cardiomyocyte progenitor cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2010;30:859–868. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.109.197434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Allen ND, Barton SC, Hilton K, Norris ML, Surani MA. A functional analysis of imprinting in parthenogenetic embryonic stem cells. Development. 1994;120:1473–1482. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.6.1473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Cibelli JB, Grant KA, Chapman KB, Cunniff K, Worst T, Green HL, Walker SJ, Gutin PH, Vilner L, Tabar V, et al. Parthenogenetic stem cells in nonhuman primates. Science. 2002;295:819. doi: 10.1126/science.1065637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Didie M, Christalla P, Rubart M, Muppala V, Doker S, Unsold B, El-Armouche A, Rau T, Eschenhagen T, Schwoerer AP, et al. Parthenogenetic stem cells for tissue-engineered heart repair. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:1285–1298. doi: 10.1172/JCI66854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Takahashi K, Tanabe K, Ohnuki M, Narita M, Ichisaka T, Tomoda K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from adult human fibroblasts by defined factors. Cell. 2007;131:861–872. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Takahashi K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell. 2006;126:663–676. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Miyoshi N, Ishii H, Nagano H, Haraguchi N, Dewi DL, Kano Y, Nishikawa S, Tanemura M, Mimori K, Tanaka F, et al. Reprogramming of Mouse and Human Cells to Pluripotency Using Mature MicroRNAs. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;8:633–638. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2011.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Warren L, Manos PD, Ahfeldt T, Loh YH, Li H, Lau F, Ebina W, Mandal PK, Smith ZD, Meissner A, et al. Highly efficient reprogramming to pluripotency and directed differentiation of human cells with synthetic modified mRNA. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;7:618–630. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]