Abstract

Mental health problems disproportionately affect Afghan refugees and asylum seekers who continue to seek international protection with prolonged exposure to war. We performed a systematic review aimed at synthesizing peer-reviewed literature pertaining to mental health problems among Afghans resettled in industrialized nations. We used five databases to identify studies published between 1979 and 2013 that provided data on distress levels, and subjective experiences with distress. Seventeen studies met our inclusion criteria consisting of 1 mixed-method, 7 qualitative, and 9 quantitative studies. Themes from our qualitative synthesis described antecedents for distress being rooted in cultural conflicts and loss, and also described unique coping mechanisms. Quantitative findings indicated moderate to high prevalence of depressive and posttraumatic symptomatology. These findings support the need for continued mental health research with Afghans that accounts for: distress among newly resettled groups, professional help-seeking utilization patterns, and also culturally relevant strategies for mitigating distress and engaging Afghans in research.

Keywords: Afghan, Depression, Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), Qualitative, Refugee, Trauma

Introduction

Afghanistan stands as one of few countries to have observed a drastic decline in its population [1]. For over three decades political turmoil has displaced Afghans both internally within Afghanistan’s borders, and externally to neighboring and other foreign countries. The Afghan exodus represents the largest refugee population in modern history. In the 1980s, nearly 6 million Afghan refugees sought international protection mainly in Iran and Pakistan [2]. A fraction of this figure resettled in India, the European Union (EU), and the United States (US) [3]. The US Census Bureau indicates that nearly 90,000 people of Afghan ancestry currently reside in the US [4] of which 65,000 are foreign born [5]. The US Office of Refugee Resettlement (2012) indicates that since 9/11 nearly 8,000 Afghan refugees have been resettled in the US [6]. Afghanistan continues to represent a major source country for refugees. While millions have been repatriated back to Afghanistan, by the end of 2009 approximately 2.6 million Afghans continued to seek international protection in Iran and Pakistan [7]. Additionally, due to ongoing security concerns Afghanistan was cited as “the most important source country of asylum-seekers” in 2011 with 35,700 asylum claims [8]. This represents a 34 % increase from the previous year as a majority of these claims (93 %) have been lodged in member and non-member countries of the EU.

Research with refugees shows their high vulnerability to psychological distress. This encompasses sadness, frustration, anxiety, and symptoms related to normal emotional responses to adversity [9]. Studies have described psychological distress as mood and anxiety disorders including depressive and posttraumatic symptomatology, respectively. Three meta-analyses pooling data from research with refugees originating from multiple countries resettling in western and non-western nations [10–12] have shown that refugee populations report disproportionately lower mental health status in comparison to economic migrants, and to the general populations in their host countries. Poor mental health outcomes have been linked to a host of pre-migration traumas (e.g., imprisonment, physical and emotional torture, loss of family members due to dis-placement and death) and post-migration stressors (cultural adjustment difficulties and the loss of social support) [13].

Psychological distress levels in Afghan refugees may parallel outcomes from studies with other refugee populations. However, there are multiple reasons to examine Afghan refugees specifically. First, Afghans continue to resettle in the US and other western nations at an unprecedented rate with prolonged exposure to war. Secondly, many have not received any prior psychological support in Afghanistan given the country’s weak mental health infrastructure [14]. Thirdly, there is indication from prior studies of migrant populations that help-seeking behaviors are tied to explanatory models about mental health that are tied to culture [15–17]. Given Afghanistan’s rich cultural and historical heritage, little research has been conducted on Afghan refugees that explore this. Much remains to be learned about their needs and the most effective ways to address them.

The current systematic review aims to appraise and summarize findings from peer-reviewed studies pertaining to the mental health of Afghan refugees resettled in western countries, as most psychiatric surveys of refugees (including Afghans) have been done in these regions [10]. Findings from this review have the potential to guide the development of more targeted, and ultimately, more effective interventions for Afghan refugees.

The following research questions guided this study:

What are Afghan refugees’ experiences with psychological distress, their emotional reactions to daily hassles, coping mechanisms, and help-seeking behaviors?

What is known about the prevalence of psychological distress among Afghan refugees and risk factors for distress?

Methods

Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

We included peer-reviewed qualitative, quantitative, and mixed-method studies that specifically focused on the mental health of Afghan refugees of all age groups and were conducted between 1979, marking the start of the protracted Afghan refugee crisis, and 2013. In this review, we broadly define mental health problems as (1) psychological distress or symptoms related to anxiety, depression, or post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) assessed through diagnostic tools or self-report questionnaires in quantitative studies; and (2) subjective experiences with psychological distress, coping mechanisms, emotional reactions to daily hassles, and help-seeking behaviors. We limited our sample to Afghans resettled in industrialized nations, which includes member states of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development [18]. We not only sought to include studies with refugees, but also studies including other forced migrant groups including asylum seekers, who face severe stressors post-migration and access limitations to healthcare and social services given their legal status [19]. This review excluded studies which were conducted with Afghans resettled in Iran, Pakistan and other neighboring countries; internally displaced persons; studies focusing solely on physical health matters (e.g. malaria, tuberculosis, war-related injuries); book chapters, editorials/commentaries, and grey literature sources.

Search Strategy

Relevant peer-reviewed studies (published in the English language) were identified through electronic sources including PubMed, all EbscoHost databases, Web of Science, PILOTS (Published International Literature on Traumatic Stress), and Google Scholar between June 2012 and April 2013. We applied combinations of search terms (using the ‘AND’ operator) relating to psychological distress as informed by previous systematic reviews [10, 11] (i.e., anxiety, depress*, mental, psych*, PTSD, stress, trauma*); and to the population, their legal status, and research design (i.e. Afghan*, asylum seeker, focus group, interview, migrant, qualitative, refugee). Given the abundance of articles relating to the mental health of U.S. military personnel, key terms relating to this domain (i.e. combat, deploy*, military, veterans) were combined with the above mentioned search terms along with the ‘NOT’ operator to exclude such articles.

All potentially relevant titles were screened for inclusion. Abstracts of retained articles were then independently reviewed by two raters to further ensure proper inclusion. Discrepancies in decisions related to inclusion/exclusion of studies were reconciled through mutual agreement [20]. Studies were subsequently subjected to a full-text review for data extraction purposes.

Data Extraction and Synthesis

We extracted data from relevant studies relating to the following: source, setting, study purpose/aim(s), methods (i.e. research design, data sources, and sampling strategy), sample size and characteristics, and results (see Table 1). Results from qualitative and quantitative articles were synthesized separately [21, 22]. Data from qualitative studies was drawn out by themes consistent with our first research question. For quantitative studies, we summarized prevalence rates and risk factors for various mental health outcomes. This extraction process also served as a secondary screening stage of studies, and led to the exclusion of studies initially retained based only on abstract contents (detailed in Results section).

Table 1.

Summary of studies (n = 17)

| Reference | Setting | Purpose/aims | Design and data sources | Sampling method | Sample size and characteristics |

Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bronstein and Montgomery [90]; Bronstein et al. [91] |

UK | To provide an estimate for probable PTSD and to investigate relationship of PTSD symptom levels with pre-migration cumulative trauma, immigration status, social care living arrangements; and to investigate the relationship between sleep patterns and PTSD |

Quantitative: Cross-sectional SLE: cumulative stress/ premigrat-ion traumatic events; RATS: PTSD symptoms |

Convenience: Participants recruited through local authority social services |

N = 222 unaccompanied asylum-seeking children (UASC); Age: M = 16.3 (SD = 1.0); Age range: 13–18; Gender: all male; Living arrangement: 62.6 % in foster care, 37.4 % in semi- independent accommodation, 3.2 % emergency accommodation; Time in host country: M = 572 days (SD = 391), range: 3–1,776 days |

Prevalence: Cumulative stress (M = 6.6, SD = 2.7), 34.3 % reported scores above the suggested cutoff for probable PTSD; RATS (M = 45.7, SD = 10.9), subscale means of 12.7 (SD = 4.0) for intrusion, M = 20.0 (SD = 5.0) for numbing, and M = 13.0 (SD = 4.3) for hyperarousal Risk factors: Cumulative trauma correlated with higher levels of PTSD symptoms (ρ = .40, p < .001); PTSD symptoms correlated with semi-independent accommodation compared to those living in foster care, F(l, 217) = 11.08, p = .001; M = 48.75, SD = 11.04 versus M = 43.83, SD = 10.33; Multivariate analysis: SLE total score and living in foster care predictive of higher RATS scores; Other associations with PTSD: on school nights, UASC with PTSD reported later bed times compared to those without PTSD [F(l,218) = 8.810, p = .03], longer time to fall asleep [F(l,197) = 15.09, p < .001], less total sleep time [F (1,195) = 19.64, p < .001]; On weekends, UASC with PTSD took longer to fall asleep [F(1,200) = 8.83, p = .03], less total sleep time [V(l,103.348) = 4.562, p = .035], higher frequency of nightmares [V(l,115.159) = 12.75, p = .001] |

| Sulaiman-Hill and Thompson [42, 101] |

Australia and New Zealand |

To explore resettlement experiences and mental health outcomes, and to examine ongoing sources of stress |

Mixed-method Kessler-10: psychological distress In-depth interviews |

Snowball: Use of multiple community entry points |

N = 90 refugees; Age range: 18–60+; Education: 43 secondary school, 33 university, 9 primary, 5 none; English language proficiency: 76 % proficient; Gender: 50 % male; Time in host country: M = 2.8 years (SD = 1.2) |

Prevalence: M = 19.8 (SD = 7.6) indicating moderate levels of distress consistent with a diagnosis of moderate depression and/or anxiety disorder Risk factors: Female gender, inability to speak English, lower education, previously married, unemployment Themes (major sources of distress): 1. Thinking too much due to past experiences and current reminders; 2. Separation from past lifestyle, feeling homesick; 3. Feeling overwhelmed due to hopelessness; 4. Relationship challenges due to family tensions and acceptance into host society; 5. Status dissonance as a result of unemployment and social position; 6. Disempowerment due to welfare dependency; 7. Social isolation due to language barriers and old age; 8. Cultural/social change due to cultural literacy; 9. Other, e.g. cultural clashes, economic hardship |

| Seglem et al. [100] |

Norway | To investigate depressive symptom levels |

Quantitative: Longitudinal CES-D: depressive symptomatology |

Convenience: Participants approached through community locations familiar with youth |

N = 116 refugee minors (demographics not provided) |

Prevalence: M = 21.51 (SD = 8.44) falling below cut-off score of 24, suggesting less than moderate levels of depressive symptoms Risk factors: Specific sub-group relationships not provided for Afghan subsample |

| de Anstiss and Ziaian [82] |

Australia | To describe use of informal supports, as well as actual and perceived barriers to mental health services |

Qualitative Focus group discussions |

Convenience and snowball: Community organizations and social gatherings |

N = 16 refugees; Age range: 14–17; Gender: 8 males |

Themes: 1. Informal help-seeking: adolescents more likely to seek help for psychosocial problems from friends than from any other source; 2. Formal help-seeking: adolescents not willing to venture beyond informal networks for professional help given low priority placed on mental health, distrust and poor knowledge of mental health services, stigma associated with help-seeking |

| Welsh and Brodsky [89] |

US- East coast |

To contextualize coping skills and situational mediators that affect transient stress reactions and support adaptive mental health outcomes |

Qualitative In-depth interviews |

Snowball: Recruitment through key-informants |

N = 8 refugees; Age: M = 43 (SD = 15.5); Age at displacement: M = 21.6 (SD = 14.1); Education: 6 college and beyond; Gender: all female; Marital status: 6 married |

Themes (related to coping): Coping strategies include: helping others including family members, seeking social support through family, maintaining hope, shifting present difficulties to future, expressing gratitude for current situation, engaging in religious activities, searching in meaning in adversity |

| Haasen et al. [94] |

Germany | To investigate a potential correlation between acculturation stress and alcohol use prior to accessing treatment |

Quantitative: Cross-sectional MAP (mental health subscale): mental complaints |

Snowball: Recruitment through 2nd author contacts |

N = 50 migrants; Age: M = 42.6 (SD = 9.2); Age range: 22–64; Age at migration: M = 31.7 (SD = 9.2); Education: all high school diploma; Gender: 92 % male; Marital status: 88 % married; Time in host country: M = 10.9 years |

Prevalence: Mental complaints: M = 9.5 (SD = 4.9); Range = 2–23; Acculturation stress: M = 11.3 (SD = 3.2) Risk factors: Significant correlation between mental distress and problematic alcohol use (r = 0.29, p < 0.05), and acculturation stress (r = 0.45, p < 0.05) |

| Feldmann et al. [83] |

Nether- lands |

To elicit refugees’ views on the way the healthcare system serves them, in order to learn about their frames of reference, expectations and experiences concerning health and healthcare |

Qualitative In-depth interviews |

Convenience: Participants approached through refugee agencies, personal networks |

N = 36 refugees; Age range: 18–66; Education: 16 secondary or lower vocational training; Employment status: 16 unemployed; Gender: 15 females; Legal status: 23 Dutch nationals, 13 humanitarian residence permit; Time in host country: 3 to 13 years |

Themes: 1. Causes of illness a result of mental worries, which include ‘thinking too much’ due to loneliness, unemployment, war experiences, loss of family members, being separated from family; 2. Strategies for coping with worries and bad memories include indulging in activities, praying, physical activity, talking with friends or family; 3. GPs primarily expected to address physical complaints, onus on individual to fight stress by keeping oneself busy |

| Gerritsen et al. [58, 93] |

Nether- lands |

To estimate prevalence rates of depression/anxiety, and PTSD symptoms, and to identify the risk factors for these complaints |

Quantitative: Cross-sectional HSCL-25: depressive symptomatology/anxiety; HTQ: traumatic experiences and symptomatology |

Random: Recruitment via sampling frame from refugee reception center |

N = 206, 90 refugees and 116 asylum seekers; Time in host country: M = 2.8 years (SD = 1.2) |

Prevalence: Depression reported in 54.7 % of respondents; Anxiety: 39.3 %; PTSD: 25.4 %; Depression/anxiety (Adjusted Odds Ratio): 2.89; PTSD symptoms (Adjusted OR): 3.08; M = 7.1 (SD = 3.5) traumatic events experienced by asylum seekers out of 17 events Risk factors: Legal status (asylum seekers), female gender, post- migration stress, and lower social support |

| Ichikawa et al. [59, 95] |

Japan | To examine the adverse effects of post-migration detention on mental health by comparing asylum seekers who had once been detained and those never detained |

Quantitative: Cross-sectional HSCL-25: Depressive symptomatology//anxiety; HTQ: traumatic experiences and symptomatology |

Convenience: Recruitment through attorneys representing asylum seekers |

N = 55 asylum seekers (18 previously detained); Age: M = 30.2 (SD = 6.9); Education: 31 secondary/ high school, 18 primary school or none, 6 university; Ethnicity: 78 % Hazara; Gender: 96 % male; Marital status: 35 unmarried; Time in host country: M = 24.4 months (SD = 15.6) |

Prevalence: 1. Detained: Anxiety (M = 2.91), Depression (M = 2.75), PTSD (M = 2.90); 2. Non-detained: Anxiety (M = 2.30), Depression (M = 2.41), PTSD (M = 2.34) Risk factors: Post-migration detention and trauma exposure significantly associated with anxiety, depression, and PTSD with estimated score increase (B coefficients) of 0.68, 0.43, and 0.47, respectively; Living alone also significantly associated with higher anxiety (0.54) and depression (0.50) |

| Omeri et al. [87, 88] |

Australia | To explore and describe health and resettlement issues and barriers; To investigate access to, and appropriateness of, mental and physical health services for the Afghan community |

Qualitative Focus group discussions and semi-structured interviews |

Convenience: Recruitment through community- based agency and informants in community |

N = 38 refugees; Age range: 20–80; Gender: 16 female and 9 male general informants, 7 female and 6 male key-informants; Time in host country: 1 to 16 years |

Themes: 1. Emotional Responses to Trauma: shame, sadness, guilt, anger, fear, grief and loss, hopelessness, frustration, dispossession, and displacement; 2. Contributory factors identified: gender role and career changes, isolation from family and friends, loss of country and identity, financial and housing difficulties, discrimination, culturally incongruent health care services, lack of health related information in Dari and Pashtu languages, lack of familiarity with the health care system in Australia |

| Morioka- Douglas et al. [86] |

US- SF Bay Area |

To increase the information available for clinicians and educators to care for, and educate others to care for, elders from Afghan backgrounds more effectively |

Qualitative Focus group discussion |

Convenience: Recruitment through community senior center |

N = 9 refugees; Gender: all female; Time in host country: 10–21 years |

Themes: 1. Conceptions of health: health status and effective treatments identified with faith in, and practice of Islam (e.g. Afghans seek prayer for good health); 2. Lifestyle and health: subjects noted enduring depression and boredom – suggested the creation of elderly organization and day care; 3. Mental illness: subjects suggested no shame or negative association with depression as mental health problems known to Afghan society and considered natural phenomena |

| Gemaat et al. [92] |

Nether- lands |

To assess the prevalence of psychiatric disorders and help-seeking behaviors |

Quantitative: Cross-sectional CIDI: depression and PTSD diagnosis |

Snowball | N = 51 refugees; Employment: 88 % unemployed; Language proficiency: 92 % moderate to poor language skills; Time in host country: M = 4 years |

Prevalence: Psychiatric disorders prevalence 65 %; Depressive disorder diagnosis: 57 %; PTSD diagnosis: 35 %; Anxiety diagnosis: 12 % Risk factors: Poor language skills, lower education level, and unemployment |

| Mghir et al. [98, 99] |

US- Seattle, WA Area |

To determine the prevalence of PTSD, depression, and other psychiatric disorders among adolescents and young adults by ethnic group and other socio- demographic variables |

Quantitative: Cross-sectional BDI: Depressive symptomatology; CAPS-1: PTSD diagnosis; HTQ: traumatic experiences; SCED |

Convenience: Recruitment through Afghan community leader |

N = 38 refugees; Age: M = 18 (SD = 3.14); Age range: 12–24; Ethnicity: 60 % Tajik, 40 % Pashtun; Gender: 55 % male; Father’s education: 60 % some college, mothers education: 78 % less than high school; No. of months in Afghanistan during war: Pashtuns: 72 months, Tajiks: 53 months; Time in host country: M = 4.6 years (SD = 2.7) |

Prevalence: 45 % met criteria for life-time diagnosis of depression; 1/3 met criteria for major depression, PTSD, or both; Being close to death most common war trauma reported (59.5 %), followed by forced separation of family members (29.7 %); Pashtuns showed greater evidence of PTSD and depression than Tajiks Risk factors (PTSD, depression, or both) : Pashtun ethnicity, age (r = 0.47, p < 0.01), age arrived in US (r = 0.52, p < 0.01), amount of English spoken by mother (r = 0.44, p < 0.01), mothers’ HSCL-25 total score (r = 0.35, p < 0.05), total number of traumatic events experienced (r = 0.48, p > 0.05) |

| Lipson and Omidian [85]; Lipson [3] |

US- SF Bay Area |

To describe mental health problems, their antecedents, ongoing everyday hassles that characterize interactions between community members and service providers |

Qualitative Ethnography- participant observation and open-ended interviews |

Network sampling techniques: Initiated by two Afghan research assistants |

N = 60 refugees; Age range: 21–73; Gender: 32 females; Education: none to doctorate; Marital status: 53 % married; Time in host country: 5 months to 14 years |

Themes: 1. Antecedents for mental health problems/stress include experiences in Afghanistan, i.e. imprisonment, observing atrocities, losing family members; 2. Escape/transit experiences while fleeing homeland and in refugee camps; 3. Continuing stressors in the US include: survivor guilt, news from media, telephone, and mail from friends and family in Afghanistan; 4. Views on health care more positive than views on social services, problems of access and communicating needs persist due to lack of language and culturally-appropriate mental health services |

| Malekzai et al. [97] |

US- SF Bay Area |

To develop a diagnostic instrument for assessment of PTSD and to provide baseline assessment of need |

Quantitative: Validation study CAPS-1: PTSD diagnosis |

Snowball | N = 30 refugees; Age: M = 42; Age range: 19–75; Gender: 50 % male |

Prevalence: 50 % met CAPS-1 criteria for a current diagnosis of PTSD, including 52 % of the male participants and 44 % of the female participants Risk factors: Age (incidence of PTSD increased from 10 % in the 19 to 30 years age group to 100 % in the 61 to 75 years age group) (r = 0.65, p < 0.005) |

| Lipson et al. [69, 96] |

US- SF Bay Area |

To assess the health concerns and needs for health education |

Quantitative: Cross-sectional Ad-hoc 96-item survey: psychosocial stress |

Snowball | N = 196 refugee families, representing 951 individuals; Age: M = 43.5 (SD = 13); Gender: 59 % female; Education: M = 15.3 years (SD = 2.7) for males, M = 10.3 years (SD = 5.6) for females; English proficiency: 61 % poor to no English ability; Household size: M = 4.9 (SD = 1.8); Time in host country: M = 8.2 years (SD = 4.1), range: 6 months to 17 years |

Prevalence: 63 % of families reported stress problems; 17 % mental health utilization rate Risk factors: Stress in family members significantly associated with inadequate income, occupational problems, and loss of culture and traditions (p < 0.00 1); Current stressors significantly related to work problems, property loss, and status loss |

| Lipson [84] | US- SF Bay Area |

To describe social and cultural stressors experienced and health problems and patterns |

Qualitative Ethnography- participant observation and open–ended interviews |

Convenience: Recruitment through pre-established community contacts |

N = 29 refugees; Age: M = 40; Age range: 16–70; Gender: 17 females; Education: M = 10 years, range: none to high school; Employment status: 24 % employed; Time in host country: M = 3.4 years, range: 4 months to 6 years |

Themes: 1. Community and Resettlement Stressors: lack of social support particularly affect women and elderly; elderly face severe isolation, depression; 2. Culture Conflict, Language, & Employment Stressors: men endure stressors associated with loss of social status, unemployment, dependency on public assistance— a source of self-esteem problems and depression; 3. Mental Health Sequelae: informants reported recurrent nightmares, becoming easily upset |

Quality Appraisal

We appraised methodological quality to assess for risk of bias and presence of confounding factors, which might explain differences in study results. The methodological quality of our sample of qualitative studies was appraised through the 10-item Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) appraisal tool [23], which ensures consideration of several fundamental areas ideally reported in qualitative reports. For example, items included: appropriateness of the research design, data collection and sampling strategies, rigor in data analysis, and ethical issues. Quantitative studies were appraised using Fowkes and Fulton’s [24] critical appraisal tool developed for various types of observational study designs including cross-sectional studies. Checklist items pertain to study-design suitably in light of research objectives, study sample representativeness, quality of measurements and outcomes, completeness (e.g. handling of missing data), and distorting influences (e.g. assessment and control of confounding factors). Both instruments were applied to the qualitative and quantitative aspects of mixed-method studies. Consistency in appraisals was assured by independent review of four randomly chosen studies from our sample (two from each design) by two raters. Discrepancies in findings were reconciled through mutual agreement.

Results

Study Selection Process

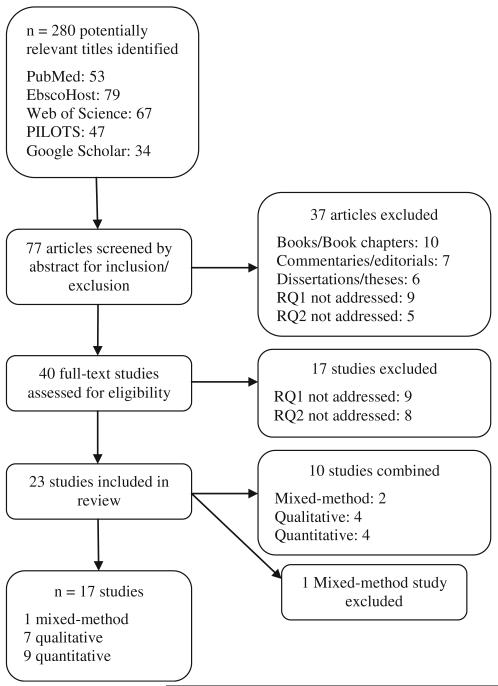

Figure 1, adapted from PRISMA [25], provides the outlay for our study selection process. Search parameters returned hundreds of articles; however, only a fraction of these references were deemed potentially relevant to our research questions. This included 280 titles of which 53 were found in PubMed, 79 in EbscoHost, 67 in Web of Science, 47 in PILOTS, and 34 in Google Scholar. After titles were evaluated, 77 articles were retained for further review. Abstract contents were screened, which subsequently lead to the elimination of 37 articles. These sources included 10 books/book chapters [26–35], seven commentaries/editorials [36–42], six doctoral dissertations/master’s theses [43–48]; nine studies were irrelevant to our first research question [49–57], and five determined irrelevant to our second research question [58–62].

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of study selection process

After full-text reviews of the remaining 40 studies, nine qualitative studies were eliminated because they contained no substantive mental health focus [63–71]. Eight quantitative studies were eliminated on grounds that prevalence rates for outcomes of interest were not specifically reported for Afghans [72–79]. Of the 23 remaining studies, two were mixed-method [80, 81], nine qualitative [3, 82–89], and 12 quantitative [90–101]. One quantitative study [95] was published in the Dutch language; however, the articles’ English language abstract provided relevant information with relation to answering our second research question, and was therefore retained in our final sample. Ten studies were combined as they essentially used the same sample in separate publications. These combinations were as follows: one mixed-method [81] and one quantitative (validation) study [101] (the other mixed-method study [80] was later eliminated as findings were reported for only a subset (one-third) of the entire sample); four qualitative studies [3, 85, 87, 88]; and four quantitative studies [90, 91, 98, 99]. This subsequently resulted in a total sample size (n) of 17 studies (one mixed-method, seven qualitative, nine quantitative).

Sample Population Characteristics

Three studies were conducted with Afghans resettled in Australia and three in the Netherlands. The United Kingdom (UK), Germany, Norway, and Japan accounted for one study each. Seven studies were conducted in the US of which five originated from the San Francisco (SF) Bay Area. Among our entire sample of studies, participants generally included refugees with the exception of two quantitative studies solely including asylum seekers [90, 91, 95] and another including both groups [93]. Slight differences in the ratio of men to women were found in heterogeneous samples; however, one study reported a disproportionately higher number of males [94]. One quantitative study [90, 91] only included male youth, and two qualitative studies purpose-fully included women only [86, 89].

Participants ranged in age from 12 to 75 years, with 3 days to 21 years of host country residence as reported in 13 studies. Three studies—two qualitative [83, 84], one quantitative [92]—reported on unemployment rates. Rates were exceptionally high, ranging from 44 to 88 % for the three samples. Educational levels ranged from none to college and beyond with males generally reporting higher levels of educational attainment. Notably, not a single study in our entire sample queried participants about their household income. Only two quantitative studies assessed ethnicity with one reporting a majority (78 %) Hazara [95]; another study reported a slightly higher proportion of Tajiks (60 %) than Pashtuns [98, 99]. Select demographic characteristics are reported here; see Table 1 for a detailed account.

Study Design Features

Qualitative Studies

U.S.-based studies include ground-breaking research (i.e. the first documented accounts of mental health problems among Afghans resettling in western countries) that describes types and sources of mental health problems [3, 84, 85]. Subsequent qualitative investigations in the U.S. and abroad (Australia and the Netherlands) have further expanded the knowledge base by contextualizing coping strategies [83, 87–89] and help-seeking views and experiences [82, 83, 86–88]. Data collection methods included ethnography, in-depth interviews, and focus group discussions (FGDs). Purposive sampling techniques provided sample sizes ranging from as little as 8–62 participants. Ninety participants were recruited in the qualitative portion of the mixed-method study in our sample [81].

Quantitative Studies

Samples in quantitative studies were obtained through nonprobability sampling techniques with one exception [93] that used random sampling through a refugee reception center. Another study [101] used snowball sampling and limited selection bias by accessing multiple community entry points. Sample sizes across studies ranged from 30 to 222 participants. Seven studies used a cross-sectional design, two were validation studies [98, 101], and one reported results from the first wave of an ongoing longitudinal study [100]. Standardized instruments to measure depressive and posttraumatic symptomatology included self-report questionnaires developed in refugee health research (e.g. Harvard Trauma Questionnaire/HTQ [102]) and those adapted for use in refugee research (e.g. Hopkins Symptom Checklist-25/HTQ [103], Beck Depression Inventory/BDI [104]); Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale/CES-D [105]; Kessler-10 [106]; the Maudsley Addiction Profile [107]; the Stressful Life Event Questionnaire/SLE [108]; and the Reactions of Adolescents to Traumatic Stress Questionnaire/RATS [109]. Three studies used clinical diagnostic tools [92, 97–99] including: Clinician Administered PTSD Scale-1/CAPS-1 [110], Composite International Diagnostic Interview/CIDI [111] for depression and PTSD, and the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM disorders/SCID [112] for depression, dysthymia, generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, and phobias.

Quality Appraisal

Qualitative Studies

Qualitative methodology was deemed appropriate for illuminating the subjective experiences of participants in our sample of qualitative studies, as maintained by the CASP appraisal tool. However, with regard to the use of specific data collection methods; two qualitative studies using focus groups [82, 86] and one using interviews [83] as a main data source did not provide a rationale for their procedures. A few studies omitted a discussion around data saturation or how sample sizes were determined [3, 82, 84, 85]. Three studies [82, 83, 86] did not address ethical issues surrounding data collection including the consent process or institutional review board (IRB) approvals. Overall, most studies demonstrated rigor in the data analysis process (e.g. in-depth description of the analysis process, how themes were derived from the data). However, only one study [87,88] addressed the investigator’s (own) potential bias during data analysis and selection of data for presentation.

Quantitative Studies

Fowkes and Fulton’s quantitative study appraisal tool supported the use of cross-sectional designs to assess disease prevalence and risk. However, most studies in the sample of quantitative studies relied on nonprobability sampling methods and small sample sizes, both posing a challenge to the external validity of the findings. With regard to the quality of measures used, all studies validated self-report questionnaires through rigorous translation-back-translation techniques, and diagnostic interviews were usually conducted by bilingual staff fluent in English and Dari or Pashto. However, only three reported psy-chometric properties such as reliability and validity coefficients [90, 91, 95, 101] and handling of missing data [95,100]. Studies took into account confounding variables through data analysis; however, few studies actually assessed plausible and distorting influences such as acculturative stress [94], employment status [81, 92, 101], and social support levels [93, 95].

Synthesis of Data

Qualitative Studies (Research Question 1)

Qualitative research described Afghans’ emotional responses to the adversity induced by traumatic war experiences as irritability, recurrent nightmares, becoming easily upset [84]; survivor’s guilt, avoidance of hearing news from back home [3, 85]; as well as frustration, hopelessness, and sadness [87, 88]. Antecedents for distress, according to SF Bay Area Afghans include events experienced while living in and subsequently escaping Afghanistan (e.g. imprisonment, losing family members). Stressors occurring post-resettlement related to cultural adjustment difficulties. These were linked to discord between parents and their children who adopt new (western) values that contradict Afghan familial values, gender role changes stemming from perceived losses of social status among men, English language conflicts often associated with unemployment and financial hardship [3, 85]. Many of the sources of stress (e.g. cultural changes, isolation, loss of social status, “thinking too much”) noted in the SF Bay Area have also been described in the qualitative portion of a mixed-method study recently conducted in Australia and New Zealand [81].

Moreover, Afghans in the Netherlands also linked the persistent nature of mental health problems to ‘thinking too much’ as a result of joblessness, loneliness and separation from family [83]. Participants indicated the need for self-care to combat stressors by “keeping oneself busy”, praying, and talking with friends as physicians were perceived to only address physical health problems. Among younger Afghans in Australia, investigators found that participants sought help for psychosocial problems from friends/informal networks—partly due to their lack of knowledge regarding mental health services [82]. The integral role of engaging with friends as a means of coping was confirmed by Afghan women at the East Coast U.S. [89]. Additionally, these women referred to engaging in religious activities for coping with stressors as did elderly women in the Bay Area. Participants suggested that improving English proficiency could mitigate feelings of isolation and depression, as well as improving access to mental health care. The lack of language-appropriate care and culturally congruent mental health care services was cited by larger-scale studies in the SF Bay Area [3, 85] and Australia [87, 88] as a barrier to obtaining help.

Quantitative Studies (Research Question 2)

Of the 196 families taking part in a seminal broad community-based health survey, 63 % reported stress problems [96]. Factors predictive of psychological well-being in this study were linked to loss of culture and values. Investigators also linked stress problems to concerns over money, education, and English language conflicts. Stressors associated with changes in culture and English language conflicts or acculturative stress have been shown to positively correlate with mental complaints (r = 0.45, p <0.05) and alcohol abuse among 50 Afghans (largely composed of men) in Germany. English language conflicts and less education have also been associated with moderate psychological distress levels (consistent with depression/anxiety diagnosis) among 90 Afghans in Australia and New Zealand [101]. Similarly, an earlier Netherlands-based study found that these same variables were risk factors for the disproportionately high depressive (57 %) and PTSD diagnosis (35 %) rates as measured by the CIDI among a sample of 51 Afghan refugees [92]. High PTSD diagnosis rates were also observed in a (CAPS-1) validation study inclusive of 30 participants in the SF Bay Area [97]. Investigators observed that 50 % of respondents met CAPS-1 criteria for a PTSD diagnosis. PTSD incidence increased from 10 % in the 19–30 years age group to 100 % in the 61–75 years age group. The authors suggest that the lower incidence of PTSD in the younger age group could be due to a strong protective effect of parental support and the fulfillment of basic needs.

Positive mental health outcomes were more recently observed among 116 Afghan minors in Norway [100]. Afghans here showed better depressive symptomatology outcomes than refugees originating from other nations as indicated by mean depressive symptomatology scores (M = 21.51), which fell below the pre-determined CES-D cut-off score of ‘24’. However, the authors do not provide any speculation as to why lower scores were observed among the Afghan subsample. In contrast, an earlier study conducted with 38 young adults in Seattle indicated a high risk of depression and PTSD. Nearly half of all participants reported having major depression (lifetime) while one-third reported having PTSD and major depression based on the SCID, CAPS, and HTQ [98, 99]. Pashtun ethnicity, amount of English spoken by their mothers, and the total number of traumatic events experienced significantly predicted these outcomes. Sixty-percent (60 %) cited being close to death and 30 % cited being forcibly separated from family members as the most common war traumas experienced. More recently, among 222 unaccompanied minors in the UK seeking asylum 61 % reported being separated from family while the majority (80 %) reported losing loved ones [90, 91]. These experiences along with the combination of other pre-migration traumas were highly predictive of PTSD symptoms.

Moreover, adults in the Netherlands also referred to ‘forced separation from family members’ as the most common traumatic experience [93]. Results indicated that the sample of 206 Afghan participants had poorer mental health outcomes than the Somali reference group. Depression, anxiety, and PTSD rates were 55, 39, and 25 % as indicated by the HSCL-25 and HTQ, respectively. Factors including female gender, post-migration stress, lower social support, and legal status (being an asylum seeker) were found to put Afghans at higher risk for these outcomes. These risk factors, in addition to the effects of post-migration detention were tested among 55 Afghan asylum seekers residing in Japan [95]. Indices of anxiety (M = 2.91), depression (M = 2.75), and PTSD (M = 2.90) symptoms exceeded pre-determined HSCL-25 and HTQ scale cut-off scores and were considerably higher in Afghans who were previously detained. However, across the entire sample trauma exposure was significantly associated with worsened mental health status; while living alone was associated with higher anxiety and depression.

Discussion

Summary of Evidence

The aim of this systematic review was to summarize published research pertaining to mental health problems affecting Afghan refugees resettled in industrialized nations. As expected, Afghans are greatly affected by psychological distress including depressive and posttraumatic symptomatology, with outcomes being highly comorbid. Quantitative studies in our sample showed that the pervasive mental health problems Afghans experience (along with various risk factors) converge with findings from studies with other refugee groups as cited in previously published systematic reviews [10–13]. Afghans’ vulnerability to psychological distress, described through much of the qualitative research is innately rooted in traumas encountered while living in and subsequently fleeing their homelands. Our findings indicate that many experienced observing atrocities, losing family members, and enduring stressful escape and transit experiences in which some were forced to live in refugee camps in Pakistan [3, 84, 85]. More recent qualitative research suggests that memories of traumatic war experiences are rekindled through current reminders that are associated with the rumination that is inextricably linked with isolation and loneliness affecting many even after long-term resettlement [80, 83].

With relation to this, four studies in our quantitative sample demonstrate a dose–response relationship between traumas encountered and psychological distress levels [90,91, 93, 95, 98, 99]. These studies mainly include newly resettled refugees and asylum seekers who reported similar war-related traumatic experiences through standardized measures. While studies conducted with Afghan asylum seekers are limited, the data here illustrates the detrimental effects of pre-migration traumas on both adults and children. While studies assessing the extent of trauma are limited, traumas encountered by Afghans may not be as distinguishable when compared to other refugee groups that also face political violence. For example, the impact of losing family due to displacement and death may be similar among various Muslim refugee groups including Afghans who value the institution of family as an integral facet to their culture [41]. Additionally, with regard to family-related issues, qualitative studies with Afghan refugees suggest that mental health problems may be amplified due to eroding cultural values that dictate family affairs [3, 85]. For example, this includes the lack of respect children show towards elders, their indifference to the culture, and their newfound sense of identity and independence.

Data synthesis further demonstrates that psychological distress is more associated with the long-term effects of being uprooted. The process of being uprooted has been described to create culture shock, a stress response to a new situation in which former patterns of behavior are ineffective [113]. Culture shock may also lead to a sense of cultural confusion, feelings of alienation, isolation, and depression [114]. Studies in our sample show that the elderly are perhaps the most vulnerable to a deep sense of being uprooted. Across all age groups the overall burden of mental health problems appears to be mediated by cultural barriers, notably language conflicts. Language conflicts among Afghans have shown to deter adjustment, and are partly responsible for the low mental health care utilization rates described in various qualitative studies here.

Low utilization could also be attributed to stigma as found among younger Afghans [82], distrust of western medical methods [115], and because psychotherapy is a uniquely western phenomenon [30]. Little data exists about mental health service use rates, and this is an area that deserves further investigation. However, qualitative studies in our sample illuminate unique help-seeking experiences of specific subgroups including young adults, the elderly, and women. These include religious activities, seeking support from family and friends, and expressing gratitude for ones current situation. It was also observed that Afghans in Germany resorted to alcohol abuse in order to cope with stressors associated with the acculturation process [94]. Qualitative studies justify the need for not only improving access and quality of services provided to Afghan refugees, but for public health professionals to increase cognizance of Afghans’ responses to stress, their current support systems, and coping strategies—all of which may be shaped by cultural and religious norms. Such information could provide practitioners a sense of how to respond to culturally salient family conflicts [15–17] and issues of self-care that can affect the biomedical regimens used in treating disorders such as depression [116].

Other stressors stemming from language conflicts include unemployment and financial hardship. With relation to this, Afghan men especially perceive tremendous losses in social status upon resettlement as reciprocity is not given to professions earned in Afghanistan. Status loss, in particular for men means losing their “traditional breadwinner role” [3, 85], which forces many to end up seeking public assistance to support their families, under-mining their self-esteem and dignity. Afghans, akin to many other refugee populations, have left behind many of the social and occupational roles they previously played, which once gave them a sense of purpose and identity [30]. Identity, or the totality of one’s perception of self [117], is cited as being intimately related to an individual’s personal and professional roles [118]. The notion of cultural bereavement or the diminished sense of self-identity, structures, and cultural values [119], taken together, epitomizes the plight of Afghan refugees.

Limitations

This systematic review has some limitations. First, the frequency of psychological distress is generally based on non-representative samples obtained through cross-sectional designs, limiting generalizability and causal inferences. Additionally, several measures were not previously validated for research with Afghans, which could either exaggerate or underestimate psychological distress levels in this population. Also, inconsistent methods used for collecting, analyzing, and reporting data—a problem common to research on refugee trauma [120]—made meta-analysis difficult to conduct, therefore necessitating this narrative summary. Moreover, this review was limited to studies conducted with Afghans residing in industrialized nations, and similar to other systematic reviews, it focused on the peer-reviewed literature and excluded unpublished studies that should be considered in conducting future research with Afghans. Also, one quantitative study [92] was written in Dutch; therefore, limiting extraction to its English abstract and preventing a quality appraisal from being carried-out.

Conclusions and Recommendations for Future Studies

Our systematic review calls for future research with Afghan refugees and asylum seekers as critical areas remain understudied. Findings from our sample of studies, a majority of which have been published after 9/11, and that consist of Afghans arriving beyond this period, underscore the need for more research on such groups as current evidence points toward severe negative mental health out-comes. In light of the protracted violence in Afghanistan, this post 9/11 resettlement wave may conceivably be composed of large, economically disadvantaged, single-parent families representative of repressed minority groups (e.g. Hazaras). Ethnicity is a factor that should be assessed in future studies, which in the case of Hazaras could provide better understanding as to how resilience along with the protective effects of strong ethno-religious linkages and community supports within this subpopulation in particular influences psychological distress. More empirical attention is also needed on unaccompanied asylum seeking children and adolescents who are at great risk of developing psychological disorders given the absence of the buffering effect that parental support may have on adjustment. Longitudinal cohort studies that include newly resettled Afghans that are followed years after resettlement could be effective in identifying the various socio-cultural and -economic factors related to the long-term impacts of trauma and depression. Such studies are needed in member (e.g. Germany, Sweden) as well as non-member countries (e.g. Turkey and Serbia) of the EU, in which thousands of asylum claims have been lodged by Afghans in the last few years. While some studies with Afghans have originated from this region, many Afghans in the countries cited above have been neglected relative to their unprecedented growth rates.

Research with Afghans suggests that an effective means of mitigating distress may rest in teaching English as quickly as possible for newly resettled refugees [85].

Language has been cited as the most important behavioral indicator of acculturation [121], and possibly a protective factor against negative mental health outcomes for specific subgroups receptive to such strategies. Refugee-serving organizations, especially in the US, ought to consider these factors in light of promoting federal mandates requiring strict job placement for preventing welfare dependency [122]. Newly resettled Afghans may also increasingly share commonalities with other refugee groups given limited English speaking abilities, possession of fewer job skills [123], as well as transportation and child care challenges. The psychological effects of war traumas could limit one’s motivation for work [124], and strict job placement requirements take away from refugees’ abilities to seek treatment for mental health problems.

The propensity to utilize professional care for mental health problems could be further illuminated through the application of prominent health care utilization models such as Andersen’s Model [125]. This model is particularly useful for understanding various ecological and need factors in relation to mental health care utilization. Such models could also provide policy makers insights for improving access to services through understanding the barriers and facilitators associated with professional help-seeking decisions. This requires culturally sensitizing clinicians and tailoring interventions accordingly to the unique needs of Afghan clients based on their explanatory models of distress. Various unpublished studies provide valuable information for mental health professionals working with Afghan clients [43], while others give context to somatization surrounding posttraumatic [34] and depressive [44] symptomatology, all of which are needed for better understanding how Afghan clients attribute mental health problems. Other more “ecological” approaches call for the integration of interventions into non-stigmatizing/existing community settings and activities, in order to enhance participation [30]. For example, Afghan religious leaders could address distress in sermons, and possibly facilitate and/or lead workshops and group therapy sessions with lay community members [30].

Future studies with Afghans ought to consider validated measures of acculturation and acculturative stress as this factor has not been definitively evaluated. For acculturation, this would include more comprehensive scales used with other populations [126] that incorporate proxy measures to assess language, identity, and behavioral preferences. Beyond these factors, there are challenges to gaining access to Afghans for carrying-out mental health research. Miller [127] cites such methodological constraints stemming from the general mistrust that Afghan refugees have in outsiders that are similarly observed among refugees from Bosnia and Guatemala. Cultural sensitivity issues also pose a challenge in terms of recruiting subgroups such as women, who Miller observed to be essentially guarded by male counterparts and family members during interviews [127].

Therefore, the hard-to-reach nature of this cultural subpopulation calls for the continued application of qualitative research. For example, Smith [46] discovered that in-depth interviews with key-informants and community gatekeepers helped build knowledge of various community dynamics and facilitated access to the larger community in a study conducted with SF Bay Area Afghans. According to Smith [46], key-informants also assisted in rapport building with lay community members by defining best practices in gaining informed consent in a non-intrusive manner (i.e. verbally). In addition, qualitative research could help sensitize quantitative measures originally developed for use with western populations. Based on the qualitative studies included in this review, focus groups have shown promise for effectively gaining feedback from lay Afghans and could therefore be used as an efficient means of developing and pilot testing measures, interpreting findings, and arriving at strategies for data dissemination. Involving Afghan community members in various phases of the research process is vital and could thereby lead to the development and implementation of culturally sensitive intervention programs for reducing mental health problems.

Acknowledgments

This manuscript was supported in part by the Sigma Xi dissertation scholarship, Loma Linda University (recipient Q. Alemi) and by NIMH K01 MH077732-01A1 (PI: S. James).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest None

Contributor Information

Qais Alemi, Department of Social Work and Social Ecology, School of Behavioral Health, Loma Linda University, Loma Linda, CA, USA; 1898 Business Center Drive, San Bernardino, CA 92408, USA qalemi05p@llu.edu.

Sigrid James, Department of Social Work and Social Ecology, School of Behavioral Health, Loma Linda University, Loma Linda, CA, USA.

Romalene Cruz, Department of Social Work and Social Ecology, School of Behavioral Health, Loma Linda University, Loma Linda, CA, USA.

Veronica Zepeda, Department of Social Work and Social Ecology, School of Behavioral Health, Loma Linda University, Loma Linda, CA, USA.

Michael Racadio, Department of Social Work and Social Ecology, School of Behavioral Health, Loma Linda University, Loma Linda, CA, USA.

References

- 1.Nyrop RF, Seekins DF. Afghanistan: a country study. Foreign area studies. The American University; Washington, DC: 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 2.UNHCR [Date last Accessed 12 May 2011];Refugees, asylum seekers, returnees, internally displaced and stateless persons 2009 global trends. 2010 http://www.unhcr.org/4c11f0be9.html.

- 3.Lipson JG. Afghan refugees in California: mental health issues. Issues Mental Health Nurs. 1993;14(4):411–23. doi: 10.3109/01612849309006903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.US Census Bureau [Date last Accessed 3 Apr 2013];Selected population profile in the United States. 2011 http://factfinder2.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?pid=ACS_11_1YR_S0201&prodType=table.

- 5.US Census Bureau [Date last Accessed 3 Apr 2013];Place of birth for the foreign-born population in the United States. 2011 http://factfinder2.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?pid=ACS_11_1YR_B05006&prodType=table.

- 6.US Department of Health and Human Services (USDHHS) [Date last Accessed 3 Apr 2013];Office of Refugee Resettlement. Refugee arrival data. 2012 http://www.acf.hhs.gov/programs/orr/resource/refugee-arrival-data.

- 7.UNHCR [Date last Accessed 12 May 2011];Asylum-Seekers. 2011 http://www.unhcr.org/pages/49c3646c137.html.

- 8.UNHCR [Date last Accessed 11 Apr 2013];Asylum levels and trends in industrialized countries, first half. 2011 http://www.unhcr.org/4e9beaa19.html.

- 9.Carney R, Freedland K. Psychological distress as a risk factor for stroke-related mortality. Stroke. 2002;33(1):5–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fazel M, Wheeler J, Danesh J. Prevalence of serious mental disorder in 7,000 refugees resettled in western countries: a systematic review. Lancet. 2005;365(9467):1309–14. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)61027-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lindert J, Ehrenstein OS, Priebe S, Mielck A, Brähler E. Depression and anxiety in labor migrants and refugees—a systematic review and meta-analysis. Soc Sci Med. 2009;69(2):246–57. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.04.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Porter M, Haslam N. Predisplacement and postdisplacement factors associated with mental health of refugees and internally displaced persons. JAMA. 2005;294(5):602–12. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.5.602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Keyes EF. Mental health status in refugees: an integrative review of current research. Issues Mental Health Nurs. 2000;21(4):397–410. doi: 10.1080/016128400248013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.World Health Organization [Date last Accessed 25 Oct 2011];Section II. Mental health atlas. 2005 http://www.who.int/mental_health/evidence/atlas/profiles_countries_a_b.pdf.

- 15.Chung R, Lin K. Help-seeking behavior among Southeast Asian refugees. J Commun Psychol. 1994;22(2):109–20. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Furnham A, Malik RR. Cross-cultural beliefs about ‘depression’. Int J Soc Psychiatr. 1994;40(2):106–23. doi: 10.1177/002076409404000203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Luu TD, Leung PP, Nash SG. Help-seeking attitudes among Vietnamese Americans: the impact of acculturation, cultural barriers, and spiritual beliefs. Soc Work Ment Health. 2009;7(5):476–93. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) [Date last Accessed 10 Oct 2012];2012 http://www.oecd.org/about/membersandpartners/

- 19.Silove D, Sinnerbrink I, Field A, Manicavasagar V, Steel Z. Anxiety, depression and PTSD in asylum-seekers: associations with pre-migration trauma and post-migration stressors. Br J Psychiatr. 1997;170:351–7. doi: 10.1192/bjp.170.4.351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wright RW, Brand RA, Dunn W, Spindler KP. How to write a systematic review. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2007;455(1):23–9. doi: 10.1097/BLO.0b013e31802c9098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pluye P, Gagnon M, Griffiths F, Johnson-Lafleur J. A scoring system for appraising mixed methods research, and concomitantly appraising qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods primary studies in mixed studies reviews. Int J Nurs Stud. 2009;46(4):529–46. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2009.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Teddlie C, Tashakkori A. Foundations of mixed methods research: integrating quantitative and qualitative approaches in the social and behavioral sciences. Sage Publications; Thousand Oaks: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) [Date last Accessed 10 Oct 2012];2010 http://www.casp-uk.net/

- 24.Fowkes FGR, Fulton PM. Critical appraisal of published research: introductory guidelines. Br Med J. 1991;302(6785):1136–40. doi: 10.1136/bmj.302.6785.1136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Plos Clin Trials. 2009;6(7):1–6. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bowles R, Mehraby N. Lost in limbo: cultural dimensions in psychotherapy and supervision with a temporary protection visa holder from Afghanistan. In: Drozbek B, Wilson JP, editors. Voices of trauma. Treating survivors across cultures. Springer Science and Business Media; New York: 2007. pp. 295–320. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Feldmann CT, Bensing JM, Boeije HR. Afghan refugees in the Netherlands and their general practitioners; to trust or not to trust? In: Feldmann CT, editor. Refugees and general practitioners. Partners in care? Dutch University Press; Amsterdam: 2006. pp. 47–65. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hafshejani A. Relationship between meaning in life and post-traumatic stress disorder among Iranians and Afghans. In: Barnes D, editor. Asylum seekers and refugees in Australia: issues of mental health and wellbeing. Transcultural Mental Health Centre; Sydney: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lipson J, Omidian P. Health and the transnational connection: Afghan refugees in the United States. In: Rynearson A, Phillips J, editors. Selected Papers on Refugee Issues. American Anthropological Association; Washington, DC: 1996. pp. 2–17. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miller KE, Rasco LM. An ecological framework for addressing the mental health needs of refugee communities. In: Miller KE, Rasco LM, editors. The mental health of refugees: Ecological Approaches to Healing and Adaptation. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Mah Wah, NJ: 2004. pp. 1–64. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Omidian PA. Qualitative measures in refugee research. The case of Afghan refugees. In: Ahearn FL, editor. Psychosocial wellness of refugees: issues in qualitative and quantitative research, studies in forced migration. Bergahn Books; Oxford: 2000. pp. 41–66. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Omidian P. Aging and family in an Afghan refugee community. Garland; New York: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Omidian P, Lipson J. Selected papers on refugee issues. American Anthropology Association; Washington, DC: 1992. Elderly Afghan refugees: tradition and transition in Northern California; pp. 27–39. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Renner W, Salem I, Ottomeyer K. Posttraumatic stress in asylum seekers from Chechnya, Afghanistan, and West Africa: differential findings obtained by quantitative and qualitative methods in three Austrian samples. In: Wilson J, Tang C, editors. Cross-cultural assessment of psychological trauma and PTSD. Springer; New York: 2007. pp. 239–75. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zulfacar M. Afghan immigrants in the USA and Germany: a comparative analysis of the use of ethnic social capital. International Specialized Book Service Inc; Portland: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Edwards DB. Marginality and migration: cultural dimensions of the Afghan refugee problem. Int Migr Rev. 1986;20(2):313–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Firling K. The Afghan refugee client. J Couns Dev. 1988;67(1):31–4. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gerritsen AM, Bramsen I, Devillé W, van Willigen LM, Hovens JE, Van der Ploeg HM. Health and health care utilisation among asylum seekers and refugees in the Netherlands: design of a study. BMC Public Health. 2004;4(7):1–10. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-4-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mehraby N. Counselling Afghanistan torture and trauma survivors. Psychother Aust. 2002;8(3):12. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mehraby N. Unaccompanied child refugees: a group experience. Psychother Aust. 2002;4:30–6. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lipson JG, Omidian PA. Health issues of Afghan refugees in California. West J Med. 1992;157(3):271–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sulaiman-Hill CR, Thompson SC. Sampling challenges in a study examining refugee resettlement. BMC Int Health Human Rights. 2011;11(2):1–10. doi: 10.1186/1472-698X-11-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Aziz N, United States International University . Cultural sensitization and clinical guidelines for mental health professionals working with Afghan immigrant/refugee women in the United States. Dissertation Abstracts International; USA: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Iqbal RA. Somatization underlying depression as related to acculturation among Afghan women in the San Francisco Bay Area. Alliant International University; San Francisco Bay: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Omidian P. Aging and intergenerational conflict: Afghan refugee families in transition. University of California; San Francisco: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Smith V. The information needs of female Afghan refugees: recommendations for service providers. Department of Communication, California State University, East Bay; Hayward, CA: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Welsh EA. After every darkness is light: the experiences of Afghan women coping with violence and immigration. University of Maryland; Baltimore County: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yusuf M. The potential for transformation in second generation Afghan women through graduate education. Dissertation Abstracts International; USA: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cherry L, Redmond S. A social marketing approach to involving Afghans in community-level alcohol problem prevention. J Prim Prev. 1994;14(4):289–310. doi: 10.1007/BF01324451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dossa P. Creating politicized spaces: Afghan immigrant women’s stories of migration and displacement. Affilia. 2008;23(1):10–21. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kanji Z, Drummond J, Cameron B. Resilience in Afghan children and their families: a review. Paediatr Nurs. 2007;19(2):30–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Khanlou N, Koh JG, Mill C. Cultural identity and experiences of prejudice and discrimination of Afghan and Iranian immigrant youth. Int J Ment Health Addict. 2008;6(4):494–513. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Perry CM, Shams M, DeLeon CC. Voices from the Afghan community. J Cult Divers. 1998;5(4):127–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sadat M. Hyphenating Afghaniyat (Afghan-ness) in the Afghan diaspora. J Muslim Minor Aff. 2008;28(3):329–42. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Smith VJ. Ethical and effective ethnographic research methods: a case study with Afghan refugees in California. J Empir Res Human Res Ethics. 2009;4(3):59–72. doi: 10.1525/jer.2009.4.3.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Stack JC, Iwasaki Y. The role of leisure pursuits in adaptation processes among Afghan refugees who have immigrated to Winnipeg, Canada. Leis Stud. 2009;28(3):239–59. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Taherpoor F, Zamani R, Mohseni N. Comparative study of individual, cognitive, and motivational bases of prejudice towards Afghan immigrants. Psychol Res. 2006;8(3-4):9–29. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gerritsen AM, Bramsen II, Devillé WW, van Willigen L, Hovens JE, Ploeg H. Use of health care services by Afghan, Iranian, and Somali refugees and asylum seekers living in The Netherlands. Eur J Public Health. 2006;16(4):394–9. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckl046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ichikawa M, Nakahara S, Wakai S. Cross-cultural use of the predetermined scale cutoff points in refugee mental health research. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2006;41(3):248–50. doi: 10.1007/s00127-005-0016-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Manneschmidt S, Griese K. Evaluating psychosocial group counseling with Afghan women: is this a useful intervention? Torture. 2009;19(1):41–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Miles M. Afghan children and mental retardation: information, advocacy and prospects. Disabil Rehabil. 1997;19(11):496–500. doi: 10.3109/09638289709166848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Osman M, Hornblow A, Macleod S, Coope P. Christchurch earthquakes: how did former refugees cope? N Z Med J. 2012;125(1357):113–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bhatia R, Wallace P. Experiences of refugees and asylum seekers in general practice: a qualitative study. BMC Fam Pract. 2007;8(48):81–9. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-8-48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Casimiro S, Hancock P, Northcote J. Isolation and insecurity: resettlement issues among Muslim refugee women in Perth, Western Australia. Aust J Soc Issues. 2007;42(1):55–69. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Feldmann CT, Bensing JM, de Ruijter A, Boeije HR. Afghan refugees and their general practitioners in the Netherlands: to trust or not to trust? Sociol Health Illn. 2007;29(4):515–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9566.2007.01005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kanji Z, Cameron BL. Exploring the experiences of resilience in Muslim Afghan refugee children. J Muslim Ment Health. 2010;5:22–40. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lindgren T, Lipson JG. Finding a way: Afghan women’s experience in community participation. J Transcult Nurs. 2004;15(2):122–30. doi: 10.1177/1043659603262490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lipson JG, Miller S. Changing roles of Afghan refugee women in the United States. Health Care Women Int. 1994;15(3):171–80. doi: 10.1080/07399339409516110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lipson JG, Hosseini T, Kabir S, Omidian PA, Edmonston F. Health issues among Afghan women in California. Health Care Women Int. 1995;6(4):279–86. doi: 10.1080/07399339509516181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Neale A, Abu-Duhou J, Black J, Biggs B. Health services: knowledge, use and satisfaction of Afghan, Iranian and Iraqi settlers in Australia. Divers Health Soc Care. 2007;4(4):267–76. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sulaiman-Hill CR, Thompson SC. Learning to fit in: an exploratory study of general perceived self efficacy in selected refugee groups. J Immigr Minor Health. 2013;15(1):125–31. doi: 10.1007/s10903-011-9547-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Masmas TN, Møller E, Buhmann C, Bunch V, Jensen JH, Hansen TN, Jørgensen LM, Kjær C, Mannstaedt M, Oxholm A, Skau J, Theilade L, Worm L, Ekstrøm M. Asylum seekers in Denmark—a study of health status and grade of traumatization of newly arrived asylum seekers. Torture. 2008;18(2):77–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.McCaw BR, DeLay P. Demographics and disease prevalence of two new refugee groups in San Francisco. The Ethiopian and Afghan refugees. West J Med. 1985;143(2):271–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Miremadi S, Ganesan S, McKenna M. Pilot study of the prevalence of alcohol, substance use and mental disorders in a cohort of Iraqi, Afghani, and Iranian refugees in Vancouver. Asia-Pac Psychiatr. 2011;3(3):137–44. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Renner W. The effectiveness of psychotherapy with refugees and asylum seekers: preliminary results from an Austrian study. J Immigr Minor Health. 2009;11(1):41–5. doi: 10.1007/s10903-007-9095-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Renner W, Salem I. Post-traumatic stress in asylum seekers and refugees from Chechnya, Afghanistan, and West Africa: gender differences in symptomatology and coping. Int J Soc Psychiatr. 2009;55(2):99–108. doi: 10.1177/0020764008092341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Renner W, Laireiter AR, Maier MJ. Social support from sponsorships as a moderator of acculturative stress: predictors of effects on refugees and asylum seekers. Soc Behav Pers. 2012;40(1):129–46. doi: 10.2224/sbp.2012.40.1.129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Renner W, Salem I, Ottomeyer K. Cross-cultural validation of measures of traumatic symptoms in groups of asylum seekers from Chechnya, Afghanistan, and West Africa. Soc Behav Pers. 2006;34(9):1101–14. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Steel Z, Momartin S, Silove D, Coello M, Aroche J, Tay K. Two year psychosocial and mental health outcomes for refugees subjected to restrictive or supportive immigration policies. Soc Sci Med. 2011;72(7):1149–56. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Sulaiman-Hill CR, Thompson SC. Afghan and Kurdish refugees, 8-20 years after resettlement, still experience psychological distress and challenges to well being. Aust NZ J Public Health. 2012;36(2):126–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-6405.2011.00778.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Sulaiman-Hill CR, Thompson SC. Thinking too much—psychological distress, sources of stress and coping strategies of resettled Afghan and Kurdish refugees. J Muslim Ment Health. 2011;6(2):63–86. [Google Scholar]

- 82.de Anstiss H, Ziaian T. Mental health help-seeking and refugee adolescents: qualitative findings from a mixed-methods investigation. Aust Psychol. 2010;45(1):29–37. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Feldmann CT, Bensing J, Ruijter A. Worries are the mother of many diseases: general practitioners and refugees in the Netherlands on stress, being ill and prejudice. Patient Educ Couns. 2007;65(3):369–80. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2006.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Lipson JG. Afghan refugee health: some findings and suggestions. Qual Health Res. 1991;1(3):349–69. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Lipson J, Omidian PA. Afghan refugee issues in the US social environment. West J Nurs Res. 1997;19(1):110–9. doi: 10.1177/019394599701900108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Morioka-Douglas N, Sacks T, Yeo G. Issues in caring for Afghan American elders: insights from literature and a focus group. J Cross-Cult Gerontol. 2004;2004(19):27–40. doi: 10.1023/B:JCCG.0000015015.63501.db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Omeri A, Lennings C, Raymond L. Beyond asylum: implications for nursing and health care delivery for Afghan refugees in Australia. J Transcult Nurs. 2006;17(1):30–9. doi: 10.1177/1043659605281973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Omeri A, Lennings C, Raymond L. Hardiness and transformational coping in asylum seekers: the Afghan experience. Divers Health Soc Care. 2004;1:21–30. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Welsh EA, Brodsky AE. After every darkness is light: resilient Afghan women coping with violence and immigration. Asian Am J Psychol. 2010;1(3):163–74. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Bronstein I, Montgomery P. Sleeping patterns of Afghan unaccompanied asylum-seeking adolescents: a large observational study. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(2):e56156. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0056156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Bronstein I, Montgomery P, Dobrowolski S. PTSD in asylum-seeking male adolescents from Afghanistan. J Trauma Stress. 2012;25(5):551–7. doi: 10.1002/jts.21740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Gernaat HB, Malwand AD, Laban CJ, Komproe I, de Jong JT. Many psychiatric disorders in Afghan refugees with residential status in Drenthe, especially depressive disorder and post-trau-matic disorder. Nederlands Tijdschr Geneeskd. 2002;146(24):127–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Gerritsen A, Bramsen I, Devillé W, van Willigen L, Hovens J, Ploeg H. Physical and mental health of Afghan, Iranian and Somali asylum seekers and refugees living in the Netherlands. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2006;41(1):18–26. doi: 10.1007/s00127-005-0003-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Haasen C, Sinaa M, Reimer J. Alcohol use disorders among Afghan migrants in Germany. Subst Abus. 2008;29(3):65–70. doi: 10.1080/08897070802218828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Ichikawa M, Nakahara S, Wakai S. Effect of post-migration detention on mental health among Afghan asylum seekers in Japan. Aust NZ J Psychiatr. 2006;40(4):341–6. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2006.01800.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Lipson J, Omidian P, Paul S. Afghan health education project: a community survey. Public Health Nurs. 1995;12(3):143–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1446.1995.tb00002.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Malekzai A, Niazi JM, Paige SR, Hendricks SE, Fitzpatrick D, Leuschen M, Millimet C. Modification of CAPS-1 for diagnosis of PTSD in Afghan refugees. J Trauma Stress. 1996;9(4):891–8. doi: 10.1007/BF02104111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Mghir R, Raskin A. The psychological effects of the war in Afghanistan on young Afghan refugees from different ethnic backgrounds. Int J Soc Psychiatr. 1999;45(1):29–40. doi: 10.1177/002076409904500104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Mghir R, Freed W, Raskin A, Katon W. Depression and post-traumatic stress disorder among a community sample of adolescent and young adult Afghan refugees. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1995;183:24–30. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199501000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Seglem KB, Oppedal B, Raeder S. Predictors of depressive symptoms among resettled unaccompanied minors. Scand J Psychol. 2011;52:457–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9450.2011.00883.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Sulaiman-Hill CR, Thompson SC. Selecting instruments for assessing psychological wellbeing in Afghan and Kurdish refugee groups. BMC Res Notes. 2010;3(237):1–9. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-3-237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Mollica RF, Caspi-Yavin Y, Bollini P, Truong T, Tor S, Lavelle J. The Harvard Trauma Questionnaire: validating a cross-cultural instrument for measuring torture, trauma, and post-traumatic stress disorder in Indochinese refugees. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1992;180:111–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Mollica RF, Wyshak G, de-Marnaffe D, Khuon F, Lavelle J. Indochinese versions Hopkins Symptom Checklist-25: a screening instrument for the psychiatric care of refugees. Am J Psychiatr. 1987;144:497–500. doi: 10.1176/ajp.144.4.497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1961;4:561–71. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1(3):385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 106.Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, Walters EE. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of twelve-month DSM-I disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R) Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):617–27. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]