ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND

Although considered a key driver of racial disparities in healthcare, relatively little is known about the extent of interpersonal racism perpetrated by healthcare providers, nor is there a good understanding of how best to measure such racism.

OBJECTIVES

This paper reviews worldwide evidence (from 1995 onwards) for racism among healthcare providers; as well as comparing existing measurement approaches to emerging best practice, it focuses on the assessment of interpersonal racism, rather than internalized or systemic/institutional racism.

METHODS

The following databases and electronic journal collections were searched for articles published between 1995 and 2012: Medline, CINAHL, PsycInfo, Sociological Abstracts. Included studies were published empirical studies of any design measuring and/or reporting on healthcare provider racism in the English language. Data on study design and objectives; method of measurement, constructs measured, type of tool; study population and healthcare setting; country and language of study; and study outcomes were extracted from each study.

RESULTS

The 37 studies included in this review were almost solely conducted in the U.S. and with physicians. Statistically significant evidence of racist beliefs, emotions or practices among healthcare providers in relation to minority groups was evident in 26 of these studies. Although a number of measurement approaches were utilized, a limited range of constructs was assessed.

CONCLUSION

Despite burgeoning interest in racism as a contributor to racial disparities in healthcare, we still know little about the extent of healthcare provider racism or how best to measure it. Studies using more sophisticated approaches to assess healthcare provider racism are required to inform interventions aimed at reducing racial disparities in health.

KEY WORDS: healthcare; racism; bias; measurement, systematic review

BACKGROUND

The existence of racial disparities in medical treatment, health service utilization and patient–provider interactions is supported by a large body of research from around the world.1–4 Although research on healthcare provider racism was first conducted over 30 years ago,5 it was not until the publication of the landmark report ‘Unequal Treatment’6 that racism was recognized as a key driver of racial/ethnic disparities in healthcare. Over a decade later, there now exists a substantial body of literature devoted to this topic,7 including reviews on perceptions of racial discrimination in healthcare8 and the impact of racism for racial/ethnic minority patients in the U.S.9

Racism can be defined as phenomena that maintain or exacerbate avoidable and unfair inequalities in power, resources or opportunities across racial, ethnic, cultural or religious groups. Racism can be expressed through beliefs (e.g. negative and inaccurate stereotypes), emotions (e.g. fear or hatred) or behaviors/practices (e.g. discrimination or unfair treatment) and can occur at three levels: internalized (incorporating racist beliefs into one’s worldview); interpersonal (racist interactions between individuals); and systemic/institutional (racism occurring through policies, practices or processes within organizations/institutions).10

The National Research Council recognized that: “no single approach to measuring racial discrimination allows researchers to address all the important measurement issues or to answer all the questions of interest”.11 Leading scholars in the study of healthcare provider racism have also noted the need for multi-method studies.7,12

Focusing on interpersonal racism rather than internalized or systemic/institutional racism, this paper reviews worldwide evidence (from 1995) for racism among healthcare providers, while also comparing existing measurement approaches to emerging best practice. Notwithstanding the need to understand and address systemic/institutional and internalized racism within healthcare provision,13,14 methods to measure these levels of racism, as well as mechanisms of influence, are heteregeneous14 and require separate consideration. Systemic racism within healthcare9,14 and the health effects of internalized racism15,16 have been the focus of previous reviews.

OBJECTIVES

To systematically review and appraise evidence of healthcare provider racism and assess current approaches to measuring racism amongst healthcare providers.

METHODS

Data Sources

The following databases and electronic journal collections were searched for studies published between January 1995 and June 2012: Medline, CINAHL, PsycInfo, Sociological Abstracts. Authors’ own reference databases and reference lists of included studies were also searched (see Appendix for details).

Study Selection

Types of Studies

Published empirical studies of any design measuring healthcare provider racism in the English language (including theses and dissertations).

Racism as reported by patients is beyond the scope of this review. Also excluded are studies focused on knowledge of minority group patients, cultural difference, cross-cultural practice and cultural competence. Moreover, because a range of factors drive racial disparities in health, we only consider disparities to be indicative of racism when found in experimental studies that are robust to alternative explanations. This includes disparities in provider diagnosis; treatment recommendations; behavior/communication; and patient satisfaction, adherence or utilization.

Types of Participants

Healthcare providers included physicians, nurses and allied healthcare professions (such as physiotherapists, social workers) and support staff (e.g. nursing aides and attendants, allied health assistants) involved in direct patient care. Reception and administration staff with direct patient contact were also included. Studies solely focused on medical or allied health students and/or their teaching staff were excluded. Health students and their teaching staff are considerably different from each other, as well as from providers themselves. Students are likely to be negotiating formation of their own individual and professional provider identity; both of which are likely to influence race-related attitudes, beliefs and behaviors.17

Titles and abstracts of all identified studies were screened for inclusion by the second and third authors, with the first author independently screening a 5 % random sample. There was no difference in inclusion/exclusion agreement between reviewers.

Data Extraction

Data were extracted for each eligible study by the second author and by the first author on a random selection of 10 %, with full agreement between authors observed. Variables for data extraction from each study were:

Study design and objectives;

Method of measurement, constructs measured, type of tool;

Healthcare provider and patient characteristics using PROGRESS-PLUS18 (Place of residence, Race/ethnicity, Occupation, Gender, Religion, Education, Socio-economic status, Social capital/networks and age, disability and sexual orientation)

Healthcare setting (e.g. primary care, tertiary);

Country and language of study; and

Study outcomes (reporting of PROGRESS-PLUS at outcome).

Quality Assessment

The quality of each eligible study was assessed by the second author (and 10 % by the first author) using the Health Evidence Bulletin Wales critical appraisal tool adapted from the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) (http://hebw.cf.ac.uk/projectmethod/appendix5.htm#top). This tool assesses key domains of study quality, including clarity of aims, appropriateness and rigor of design and analysis, including risk of bias, and relevance of results.19 The first author also reviewed each completed critical appraisal tool for accuracy. Differences in assessment were resolved by discussion between the two reviewers.

RESULTS

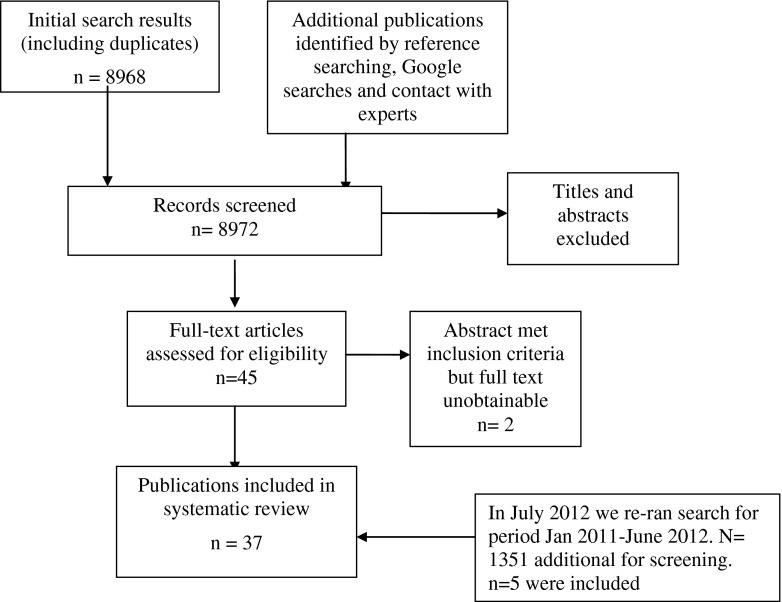

A total of 37 studies published between January 1995 and June 2012 met the inclusion criteria (asterisked in the reference list). See Figure 1 for flow chart of search. A summary of the key characteristics of each study is detailed in Table 1, including study design, country, healthcare setting, provider profession and racial/ethnic background of provider and patient (where applicable). Statistically significant evidence of racist beliefs, emotions or practices among healthcare providers in relation to minority groups was evident in 26 of these studies. No particular patterns emerged by country, study population, healthcare setting or measurement approach.

Figure 1.

Systematic review flowchart—initial search conducted December 2010.

Table 1.

Characteristics of 37 Studies of Reported Healthcare Provider Racism in Relation to Minority Groups

| Author | Country | Healthcare setting | Provider profession | No. of health care providers | Provider racial/ethnic background | Patient racial/ethnic background (real or hypothetical) | Provider measurement approach | Main findings/outcomes + evidence of racism ø no evidence of racism |

Limitations | Study quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abreu71 | USA | Veterans Administration Medical Center, community college, state-supported university | Therapists, psychology interns, advanced psychology graduate students | 60 | White, Chinese, Japanese, African American, Hispanic, other | African American | Vignette with stereotype priming procedure followed by questionnaire of clinical diagnostic impressions | (+) Results indicate that participants primed with stereotype words rated the hypothetical African American patient significantly less favorably than did participants primed with neutral words. | Small sample size. 25 % percent of the sample were not licensed therapists. Internal validity threat through changes between the race undisclosed and race Black conditions. | Moderate |

| Al-Khatib60 | USA | Academic, government or other (solo, group, private, HMOa) | Physicians (electrophysiologists, general cardiologists, pediatric cardiologists, other) | 1,127 | White, Asian, other | White and Black | Vignette followed by questionnaire regarding likelihood to recommend implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) therapy | (ø) Physicians were equally willing to offer an ICD to men and women and to Whites and Blacks, but were less likely to offer an ICD to an older patient, even when indicated by practice guidelines. | 12 % response rate. Self-report survey. Bivariate analysis only. Not all confounding and bias considered. | Moderate |

| Balsa et al.72 | USA | HMOs, large multi-speciality groups, solo practices | Physicians, internists | 523 (11,664 patients) | Not reported | White, Black, Hispanic, Asian, Native, other minorities | Tests of statistical discrimination based on the comparison of a traditional disparities regression | (+) There is evidence consistent with statistical discrimination for doctors’ diagnoses of hypertension, diabetes and depression for Whites and minorities. Furthermore, in the case of depression, there is evidence that race affects decisions through communication. | Potential bias and confounding in the model and data. | High |

| Barnhart & Wassertheil-Smoller62 | USA | Academic setting or private practice | Family medicine physicians, internists, cardiologists, and cardiothoracic surgeons | 544 | Black, White, Asian, Hispanic | Black and White | Vignettes followed by questionnaire regarding treatment decisions related to coronary revascularization | (ø) The patient’s race/ethnicity and sex did not significantly affect the physicians’ treatment preferences. Significant differences were found according to the social circumstances such as family demands. | Participants only given one vignette. Responses stratified by race/ethnicity and sex might have limited power to detect significant differences in revascularization preferences. | Moderate |

| Bogart et al.59 | USA | Hospitals, research institutions, private practice, medical teaching facility | Infectious disease physicians | 495 | Majority White (86 %), other unspecified | African American and White | Vignettes followed by questionnaire regarding adherence and treatment decisions related to patients with HIV disease | (+) Physicians perceived both men and women who had contracted HIV as a result of prior injection drug use to be less likely to adhere to therapy, and they perceived African American men to be less adherent than White men. | 53 % response rate. Not all confounding and bias considered. | Moderate |

| Burgess et al.54 | USA | Not reported | Primary care physicians | 375 | White, African American, Asian/Pacific Islander, Native American, Hispanic, other | Black and White | Vignettes followed by questionnaires regarding treatment change, concerns about the use of opioids for chronic pain and perceptions of patients | (+) There was a significant interaction between patient verbal behavior and patient race on physicians’ decisions to prescribe opioids. Among black patients, physicians were more likely to state that they would switch to a higher dose or stronger opioid for patients exhibiting ‘challenging’ behaviors compared to those exhibiting “non-challenging” behaviors. For White patients, there was an opposite pattern of results. | 40 % response rate. Not all confounding and bias considered. | Moderate |

| Cabral et al.61 | Brazil | Public dentistry, military dentistry, company dentistry, and private dentistry | Dentist | 297 | White and Mulatto | Black (dark-skinned patient) and White (fair-skinned patient) | Vignettes followed by questionnaire on dentists’ decision regarding tooth extraction | (+) The dentist’s decision varied significantly according to the patient’s race, with dentists deciding to extract more frequently for the black patient than for the White patient. | Not all confounding and bias considered. Bivariate analysis only. | Moderate |

| Constantine et al.27 | USA | Not reported | Marital and family therapists | 113 | White, other non-specified | Not applicable | Questionnaires: Multicultural Counseling Knowledge & Awareness Scale (MCKAS), New Racism Scale (NRS), Marlowe-Crowne Social Desirability Scale (SDS), White Racial Identity Attitude Scale(WRIAS), Visible Racial/Ethnic Identity Attitude Scale | Reported findings not specific to racism/prejudice | Not applicable | Moderate |

| Cooper et al.69 | USA | Urban, community based practices | Physician, nurse practitioner | 40 (269 patients) | White, Black, Asian (including Indian subcontinent) | White, Black | IAT;b medical visit audio recording, questionnaire regarding preferences or feelings toward and perceived cooperativeness of Whites and Blacks | (+) Among Black patients, general race bias was associated with more clinician verbal dominance, lower patient positive affect, and poorer ratings of interpersonal care; race and compliance stereotyping was associated with longer visits, slower speech, less patient centeredness, and poorer ratings of interpersonal care. | Non-random and small sample size. | Moderate |

| Di Caccavo et al.58 | UK | Not reported | General practitioners | 18 | White | African Caribbean, Asian, White | Vignettes followed by questionnaires regarding diagnostic and treatment decisions for patients with anxiety | (+) Results indicated that White patients were more likely to be correctly diagnosed as having anxiety than any other complaint. Asians were just as likely to receive a physical diagnosis as they were to receive one of anxiety. | Small sample size. 18 % response rate. Not all confounding and bias considered. | Low-Moderate |

| Drwecki65 | USA | Not applicable (laboratory study) | Nurses | 40 | White, African American, Asian, Latino, multiracial | Black and White | Vignettes followed by questionnaire regarding pain assessment and treatment (Pain Treatment Scale, Empathic Concern Scale); IAT. | (+) Experiment 4 relevant: participants exhibited a significant pro-White pain treatment bias and implicit racial drug abuse stereotypes. Prejudice was relatively unrelated to racial pain treatment bias. | Small sample size. Pain cues used were limited. | Moderate |

| Green et al.36 | USA | Academic medical centers | Internal & emergency medicine residents | 287 | White, Black, Hispanic, Asian, other | Black and White | Vignettes followed by questionnaire regarding preferences for White vs. Black patients and perceptions of cooperativeness; IATs | (+) Physicians reported no explicit preference for White versus Black patients or differences in perceived cooperativeness. In contrast, IATs revealed implicit preference favoring White Americans and implicit stereotypes of Black Americans as less cooperative. As physicians’ pro-White implicit bias increased, so did their likelihood of treating White patients and not treating Black patients with thrombolysis. | 50.6 % response rate (only 28.4 % included in the analysis). Participants only given one vignette. | Moderate |

| Green et al.32 | USA | Administrator/manager, planner, supervisor, direct service, policy analyst/lobbyist, consultant, educator, other. | Social workers | 257 | White | People of Color | Questionnaire: Cognitive and Affective Racial Attitudes Scales of the Quick Discrimination Index (QDI) | (+) Social workers’ cognitive attitudes were more positive than their affective attitudes. They possess the same ambivalence and social distance about race that characterizes contemporary American society, and 12 % do not believe racism is a major social problem in the United States. | 43 % response rate (White-only participants included in analysis). Social desirability a possible influence. | Moderate |

| Hirsh et al.49 | USA | Critical care, primary care, oncology | Nurses | 54 | 93 % White | Caucasian, African American | Vignettes using virtual human (VH) technology followed by questionnaires regarding pain assessment and treatment decisions | (+) None of the participants reported using VH sex, race, or age in their decision process. However, statistical modeling indicated that 28–54 % of participants (depending on the decision) used VH demographic cues, including race. | Small sample size. Non-random sample. | Moderate |

| Joseph31 | USA | Army hospital | Nurses | 86 | White European American, Black/African American/African Caribbean, Hispanic, Asian, other | African American, Hispanic | Vignettes followed by questionnaires regarding attitudes toward African American and Hispanic patients (Ethnic Attitude Assessment survey) | (+) Attitudes were statistically more positive toward the African American patient than toward the Hispanic patient. Females had more positive attitudes than males but only toward African American patients. | Small sample size. Vignette did not include a White scenario. Limited statistical analysis. | Low-Moderate |

| Kales et al.51 | USA | Urban practice location, other | Psychiatrists | 329 | White, Asian, African American, Hispanic, other | White, African American | Vignettes followed by questionnaires regarding diagnosis/treatment decisions of patients with depression and perceptions of patient characteristics | (ø) Patients’ race and gender was not associated with significant differences in the diagnoses of major depression, assessment of most patient characteristics, or recommendations for managing the disorder. | Participants only given one vignette. Not all confounding and bias considered. | Moderate |

| Kales et al.50 | USA | Urban practice location, other | Primary care physicians | 178 | White, Asian, African American, Hispanic, other | White, African American | Vignettes followed by questionnaires regarding diagnosis/treatment decisions of patients with depression and perceptions of patient characteristics | (ø) There were no significant differences in the diagnosis of depression, treatment recommendations, or physician assessment of most patient characteristics by the race or sex of the patient/actor in the vignette. | Participants only given one vignette. Participants may have been primed to diagnosis of depression by being aware of the study’s focus on mental health. | Moderate |

| McKinlay et al.52 | USA | Physician office | Physicians (surgeons, gynecologists, oncologists) | 128 | White | Black and White | Vignettes followed by questionnaire regarding treatment decisions of unknown and known breast cancer cases | (ø) Physicians displayed considerable variability in clinical decision making in response to several patient-based factors, including race, age and socioeconomic status. | Only physicians trained in USA were included. | Moderate-high |

| McKinlay et al.64 | USA | Not reported | Doctors in family practice and internal medicine | 128 | White, African American | Black and White | Vignettes followed by questionnaire regarding diagnosis, level of certainty, number of tests ordered for patients with depression and polymyalgia rheumatica | (ø) Patient attributes (age, race, gender, and socioeconomic status), had no influence on the clinical decision-making. Physician attributes (medical specialty, race and age) interactively influenced decision-making. | Presentation of vignettes was not randomized. The same study participants were used for both health conditions. | Moderate |

| Michaelsen et al.25 | Denmark | Hospital | Doctors, nurses, assistant nurses | 516 | Danish | Immigrants | Questionnaire regarding knowledge, attitudes and experiences regarding immigrants | (+) Doctors and nurses showed the most positive attitudes towards different statements about immigrants, and assistant nurses the most negative. | 43 % response rate for assistant nurses compared to 52 % for nurses and 56 % for physicians. A non-standardized survey was utilized. | Moderate |

| Middleton et al.26 | USA | Private, university, community agency, school, government, hospital, independent | Clinical psychologists, counseling psychologists, counselors | 412 | European American | Not applicable | Questionnaires: White Racial Identity Attitude Scale, Multicultural Counseling Inventory. | Reported findings not specific to racism/prejudice | Not applicable | Moderate |

| Mitchell & Sedlacek29 | USA | Not reported | Executive directors, hospital educators, business/financial affairs, procurement coordinators, public relations | 51 | White, African American, Asian, Latin, Native American | Blacks, Hispanics | Questionnaire: Situational Attitude Scale (SAS) | (+) Findings showed that participants favored the person of color over the neutral, race-unspecified person when the person of color was in a subservient role. | Small sample size. Items in survey not specific to health care. Limited statistical analysis. Not all confounding and bias considered. | Low |

| Moskowitz et al.34 | USA | Outpatient practice | Doctor, nurse practitioner, physician assistant | 61 | White, non-White | African American, White, Latino, other. | Questionnaire: Physician Trust in the Patient Scale (PTPS) | (+) Reported current illicit drug use and prescription opioid misuse were similar across patients’ race or ethnicity. However, both patient illicit drug use and patient non-White race/ethnicity were associated with lower Physician Trust in Patient Scale scores. | Small sample size. Social marginalization of patients limits generalizability to other populations. | Moderate |

| Moskowitz et al.70 | USA | Hospital | Doctors | Study 1 = 3, study 2 = 11 | White | White, African American | Stereotype priming followed by IAT | (+) When primed with an African American face, doctors reacted more quickly for stereotypical diseases, indicating an implicit association of certain diseases, conditions and social behaviors with African Americans. | Small sample size. Not all confounding and bias considered. Limited statistical analysis. | Low-moderate |

| Noble et al.30 | Israel | Academic tertiary care health facility | Midwives | 30 | Israeli, North American, North African, Asian, European | Ultra-Orthodox, Religious, Traditional, or Secular Israeli Jews | Questionnaire: Inventory for Assessing the Process of Cultural Competence (IAPCC-R), Ethnic Attitude Scale-Adapted | (+) Midwives’ ethnic attitude differed significantly among Secular, Traditional, Religious, and Ultra-Orthodox Jewish patient scenarios. The most positive attitudes and lowest bias scores occurred for midwives when the patient scenarios were similar to or congruent with their religious identification. | Small sample size. Not all confounding and bias considered. Limited statistical analysis. | Moderate |

| Paez et al.28 | USA | Community-based primary care clinics | Family physicians, internal medicine physicians, nurse practitioners | 49 | White, Black, Asian, East Indian, Hispanic | Not applicable | Questionnaire: 6 items from Dogra’s Cultural Awareness Questionnaire & Godkin’s Modified-Cultural Competence Self-Assessment Questionnaire; Cultural Competency Assessment Instrument (CCA): 5 items on attitude, 5 items on behavior. | (+) Providers with attitudes reflecting greater cultural motivation to learn were more likely to work in clinics with a higher percent of non-White staff, and those offering cultural diversity training and culturally adapted patient education materials. More culturally appropriate provider behavior was associated with a higher percent of non-White staff in the clinic, and culturally adapted patient education materials. | Small sample size. Non-randomized sample. Standardized measure of provider cultural competence not utilized. | Moderate |

| Pagotto et al.33 | Italy | Hospitals | Nurses | 167 | Italian | Immigrants | Questionnaire regarding contact at work, empathy and anxiety at work, empathy and anxiety at group level, contact outside the workplace, contact though mass media, prejudice indexes | (+) Hospital workers’ interactions with immigrants were associated with lower levels of prejudice towards immigrants in general. | Non-standardized survey instrument used. Not all confounding and bias considered. | Moderate |

| Penner et al.24 | USA | Inner city primary care clinic | Family medicine residents | 15 (150 patients) | White, Indian, Pakistani, Asian | Black | Pre-consultation with patient: 25-item questionnaire and IAT; post-consultation: 2-item questionnaire. | (+) Black patients had less positive reactions to medical interactions with physicians relatively low in explicit bias but relatively high in implicit bias than to interactions with physicians who were either: (a) low in both explicit and implicit bias, or (b) high in both explicit and implicit bias. | Small sample size. Low proportion of White physicians. | Moderate |

| Sabin et al.37 | USA | Not reported | Medical doctors | 2,535 | White, African American, Asian, Hispanic | White and Black | IAT; 1-item questionnaire | (+) Medical doctors showed an implicit preference for White Americans relative to Black Americans. African American MDs, on average, did not show an implicit preference for either Blacks or Whites, and women showed less implicit bias than men. | Non-random self-selected sample. Survey completed via the internet. Not all confounding and bias considered. | Moderate |

| Sabin et al.35 , 110 | USA | Large, urban research university | Academic pediatricians | 95 | White, non-White | White and Black | IAT; questionnaire regarding racial bias/attitudes; vignettes with questionnaires regarding quality of pediatric care | (+) There was an implicit preference for European Americans relative to African Americans. Medical care differed by patient race for the management of urinary tract infection, pain management following surgery and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) treatment. | 53 % response rate (all measures completed). Female gender response bias. Specific IATs used had not been validated. | Moderate |

| Schulman et al.56 | USA | Full time clinical practice | Family physicians, internists | 720 | White, Black, Hispanic, Asian, Aleut | White and Black | Vignettes followed by questionnaires regarding patient referrals for cardiac catheterization | (+) Race and sex of the patient affected the physicians’ decisions about whether to refer patients with chest pain for cardiac catheterization. | Participants only given one vignette. | Moderate- high |

| Stepanikova53 | USA | Group practice, solo practice, academic practice, HMO, government practice | Family physicians & general internists | 7213 | White, Black, Hispanic, Asian | Hispanics, Blacks, Whites | Implicit priming task then vignettes followed by questionnaire regarding diagnosis and treatment of patient with chest pain | (+) Under high stress, physicians whose implicit cognitions about Blacks or Hispanics were activated by subliminal exposure to Black or Hispanic stimuli evaluated a hypothetical patient’s condition as less serious compared to physicians subliminally exposed to White or neutral stimuli. | Sampling frame limited to privately insured adults receiving healthcare in a 12-month period. | High |

| Thamer et al.57 | USA | Hospital, free standing facility | Nepthrologists | 271 | White, Asian, African American | White, African American, Asian | Vignettes followed by questionnaire regarding recommendations for renal transplantation | (+) Female gender, and Asian but not Black race, were associated with a decreased likelihood that nephrologists would recommend renal transplantation for patients with end stage renal disease. | 53 % response rate. Not all confounding and bias considered. | Moderate |

| Todd et al.48 | USA | Urban emergency department | Doctors | 37 (217 patient cases) | Not reported | White and Black | Medical chart abstraction and analysis regarding treatment of bone fractures with analgesics | (+) White patients were significantly more likely than Black patients to receive ED analgesics, despite similar records of pain complaints in the medical record. | Retrospective design. Potential misclassification of outcomes, demographic details and potential confounders. | Moderate |

| Van Ryn & Burke23 | USA | State hospitals | Cardiologists, cardiac surgeons | 193 (618 patient–physician encounters) | White, African American, Asian, Hispanic, Other | White, African American | Questionnaire regarding physicians’ perceptions of patients’ abilities and personality characteristics, physicians’ feeling of affiliation toward the patient, perceived behavioral likelihoods and role demand | (+) Physicians’ perceptions of patients were influenced by patients’ sociodemographic characteristics. For example, patient race was associated with physicians’ assessment of patient intelligence, feelings of affiliation toward the patient, and beliefs about patient’s likelihood of risk behavior and adherence with medical advice. | Not all confounding and bias considered. Non-standardized survey instrument. | Moderate |

| Weisse et al.63 | USA | Not reported | Attending physicians, residents | 712 | White, Black, Hispanic, Asian/Pacific Islander, other | White and Black | Vignettes followed by questionnaire regarding assessment and management of pain | (ø) No overall differences by patient gender or race were found in decisions to treat or in maximum permitted doses. | 28 % response rate. Not all confounding and bias considered. Limited statistical analysis. | Moderate |

| Weisse et al.55 | USA | Not reported | Attending physicians, residents | 111 | White, Black, Hispanic, Asian/Pacific Islander, other | White and Black | Vignettes followed by questionnaire regarding assessment and management of pain | (ø) No overall differences with respect to patient gender or race in decisions to treat or in the maximum permitted doses. | Convenience sample. 50 % response rate. Not all confounding and bias considered. Limited statistical analysis. | Moderate |

a HMO Health Maintenance Organization

b IAT Implicit Association Test

Measurement of Racism

Direct measures of racism occur when the attribute being assessed is asked about specifically, while indirect measures require inference from collected data.20,21 Although the terms direct and indirect are utilized in this review, various other terms are commonly used, including: automatic vs. controlled, spontaneous vs. deliberate, implicit vs. explicit, impulsive vs. reflective and associative vs. rule-based/propositional.22

Direct Measures

Self-completed surveys were the most commonly utilized direct measurement approach.23–37 Van Ryn & Burke23 assessed beliefs about patient abilities and personality characteristics through physicians rating a series of semantic differentials (intelligent-unintelligent; self-controlled-lacking self-control; pleasant-unpleasant; educated-uneducated; rational-irrational; independent-dependent; and responsible-irresponsible). Providers rated patients on stereotypes in terms of how likely they were to: lack social support; exaggerate discomfort; fail to comply with medical advice; abuse drugs, including alcohol; desire a physically active lifestyle; participate in cardiac rehabilitation (if it were prescribed); try to manipulate physicians; initiate a malpractice suit; have major responsibility for the care of a family member(s); and have significant career demands/responsibilities.23

Van Ryn & Burke23 also assessed social distance with one item (‘this patient is the kind of person I could see myself being friends with’), while Green et al.32 utilized the 7-item Affective Racial Attitudes Scale38 to assess social distance and inter-group contact (e.g. ‘my friendship network is very racially mixed’). Sabin et al.35 and Green et al.36 assessed feelings of warmth towards African and European American (0 cold to 10 warm), while Sabin et al.35 also assessed stereotypes of compliance by asking providers whether African or European Americans were more generally likely to be compliant patients. Sabin et al.35 asked whether Blacks or Whites were more likely to receive appropriate treatment generally, and in the providers’ own workplace. Sabin et al.37 and Green et al.36 directly assessed racial preference (e.g. ‘I like White Americans and African Americans equally’ to ‘I moderately/strongly prefer African Americans to White Americans’).

Mitchell & Sedlacek29 used the 100-item semantic differential Situational Attitude Scale39 to assess ten emotional reactions relating to Hispanics, African Americans and people of an unspecified racial group across ten social situations controlling for social desirability (e.g. for the situation ‘New family next door’, the items are: good-bad, safe-unsafe, angry-not angry, friendly-unfriendly, sympathetic-not sympathetic, nervous-calm, happy-sad, objectionable-acceptable, desirable-undesirable, suspicious-trusting).

The 20-item Ethnic Attitude Scale40,41 assessed beliefs in response to a clinical scenario/vignette,30 while Constantine et al.27 measured racism towards Blacks using the 7-item New Racism Scale42 as well as views of White privilege using the Awareness subscale of the Multicultural Counseling Knowledge and Awareness Scale.43 Constantine et al.27 also utilized the 43-item Visible Racial/Ethnic Identity Attitude Scale44 and 50-item White Racial Identity Attitude Scale45 to assess a range of race-related beliefs, emotions and behaviors, while Michaelsen et al.25 assessed knowledge of and attitudes towards immigrants with 29 items. Penner et al.24 utilized a 25-item scale46,47 and Green et al.32 a 9-item scale38 to measure beliefs about to race-related policies, including awareness of contemporary racism.

Paez et al.28 used one item each to assess belief in race-based meritocracy, White privilege and assimilationist ideology. Middleton et al.26 assessed self-perceptions of racism among providers (‘When working with minority individuals, I am confident that my conceptualization of client problems do not consist of stereotypes and biases’ and ‘When working with minority clients, I perceive that my race causes clients to mistrust me’) within the 40-item Multicultural Counseling Inventory.

Indirect Measures

Vignettes are indirect measures that infer bias in diagnosis, recommended treatment or patient characteristics (i.e. practices/behaviors) from differential response to hypothetical situations that are identical except for the race/ethnicity of the patients involved. Vignettes are primarily based on brief written scenarios, but can also include more detailed approaches such as medical chart abstraction48 and audio-visual material. For example, Hirsh et al.49 utilized 20-second audio-visual clips of virtually generated characters along with vignettes to examine the influence of contextual information (i.e. sex, race and age) on pain-related decisions among nurses. Vignettes, as an indirect approach to measuring racism, were more commonly utilized than self-completed surveys among studies included in this review.35,36,49–65,70

A range of computer-based indirect measures were also used, notably several versions of the Implicit Association Test (IAT).66 In the studies reviewed here, the IAT involved a comparison of two target objects that produced a measure of relative preference for one race over another. Participants are required to categorize a set of names or faces in terms of their membership in a relevant category (e.g., a race/ethnicity). The IAT differs from priming tasks (semantic or evaluative/affective) in which participants are not explicitly required to process the category membership of the presented stimuli. Instead, primes (either words or images) relating to particular racial/ethnic groups are presented very briefly (80–300 ms), such that they are not consciously recalled by participants. This can be preceded by a cover-up task to allay suspicion. A neutral mask (also a word or image) before and/or after can also be used to reduce visibility of the prime. While there is some evidence that indirect measures are correlated,67 it is likely that measures using different underlying mechanisms such as IATs and priming tasks produce distinct results.68

The IATs reviewed here evaluated Black-White race generally;24,35–37,65,69,70 stereotypes about Blacks being uncooperative;36 stereotypes about Blacks being medically uncooperative;36 race in relation to compliant patients;35 and race in relation to the quality of medical care.35 Affective (also known as evaluative) priming tasks were also utilized.53,70,71 Stepanikova53 used racial labels (African American and Hispanic) and one Black stereotype-related word (i.e. rap) along with an initial cover-up task and a mask presented after each prime, while Abreu71 used stereotypes (Negroes, Blacks, lazy, blues, rhythm, Africa, stereotype, ghetto, welfare, basketball, unemployed, and plantation) with a mask presented after each prime. Moskowitz70 used stereotyped African American diseases such as HIV, hypertension and drug abuse mixed with non-stereotyped diseases such as chicken pox, leukemia and Crohn’s disease.

As an alternative method indirect measure, Balsa et al.72 tested for statistical discrimination in relation to survey and interview data. This study examined the extent to which doctors’ rational behavioral reactions to clinical uncertainty explained racial differences in the diagnosis of depression, hypertension and diabetes.

Studies Utilizing Both Direct and Indirect Measures

Five studies used both direct and indirect measures of racism.24,31,35,37,69 Cooper et al.69 used both the IAT and self-reported measures (designed to assess concepts in the IATs, including preferences or feelings toward and perceived cooperativeness of Whites and Blacks). Sabin et al.35,37 and Penner24 utilized explicit measures of racial attitudes/prejudice in addition to the IAT. Joseph31 used a vignette and questions about the patient care situation, followed by three questions related to cultural diversity.

Extent of Racism

Eleven vignette-based studies found that race influences the medical decision making of healthcare practitioners in relation to minority groups,35,36,49,53,54,56–59,61,65 whereas eight studies found no association.50–52,55,60,62–64 For example, Schulman et al.56 found that physicians were less likely to refer Black women for cardiac catheterization, even after adjusting for symptoms, the physicians’ estimates of the probability of coronary disease and clinical characteristics. In contrast, Weisse et al.55,63 found that physician decisions related to pain management were not influenced by race.

Four studies24,35–37 utilizing the IAT found that implicit racial bias existed among healthcare providers in the absence of explicit bias. In Stepanikova’s53 study, physicians’ medical decisions were influenced when subliminally exposed to Black and Hispanic stimuli. In Abreu’s71 study, participants primed with stereotypes related to African Americans rated a hypothetical patient more negatively.

Four studies using direct measures showed evidence of racism,23,29,31,34 while two studies did not find such evidence.32,35 Van Ryn & Burke23 found that physicians were less likely to have positive perceptions of Black than White patients across several dimensions, including compliance with medical advice and level of intelligence. Moskowitz et al.34 found that physicians had lower trust in non-White, compared with White, patients. In contrast, Sabin et al.35 found no significant differences in reported feelings towards European Americans and African Americans.

Pagotto et al.33 found that hospital workers’ interactions with immigrants were associated with lower levels of prejudice towards immigrants in general. Green et al.32 found that social workers possess the same ambivalence and social distance about race as the broader U.S. population, while Noble et al.30 found increased religiosity among hypothetical Jewish patients in clinical scenarios was associated with more racism against them. Balsa et al.72 found that physicians’ perceptions about the prevalence of disease across racial groups was associated with racial differences in the diagnosis of hypertension and diabetes. Although measuring healthcare provider racism, neither Middleton et al.26 nor Constantine et al.27 reported specifically on these findings.

Study Quality

Study quality was assessed in relation to the following areas: clarity of aims, appropriateness and rigor of design and analysis, including risk of bias, and relevance of results.19 The majority of studies were of moderate quality. All studies were cross-sectional, therefore limiting causal inference. Major methodological limitations of studies were: small sample sizes (e.g. n = 11,70n = 1524),28–31,34,36,49,58,65,69,71 low response rates (e.g. 1–2 %,53 11 %26),25,32,35,54,57,60,63 non-representative samples (e.g. army nurses working in one hospital,31 infectious disease physicians59),52,71 threats to internal validity due to social desirability (e.g. Constantine et al.,27 Weisse et al.63),32,50 not controlling for confounders (e.g. gender),23,29,33,37,51,54,55,57–61,63,70,72 using non-randomised samples,28,37,49,55,69 and utilizing limited statistical analysis.29,31,55,63,70 Thirty of the thirty-seven studies were conducted in the United States, limiting generalizability of results.

DISCUSSION

Over two-thirds of studies included in this review found evidence of racism among healthcare providers. This includes racist beliefs, emotions and behaviors/practices relating to minority patients. No particular patterns emerged by country, study population, healthcare setting or measurement approach. A plethora of measurement approaches were used with little consistency across the included studies. Self-completed surveys were the most commonly utilized direct measurement approach, including assessment of patient abilities and characteristics, stereotypes, social distance, intergroup contact, perception of appropriate treatment, racial preference, emotional reactions and feelings of warmth towards racial/ethnic groups, as well as race-related beliefs and attitudes including White privilege and awareness of contemporary racism. Indirect measures consisted predominantly of clinical scenario vignettes or computer-based versions of the Implicit Association Test (IAT). Five studies used both direct and indirect measures. Eleven vignette-based studies found that race influences the medical decision making of healthcare practitioners, whereas eight studies found no association. Four studies utilizing the IAT found that implicit racial bias existed among healthcare providers in the absence of explicit bias. Four studies using direct measures showed evidence of racism, while two studies did not find such evidence. Findings of this review have substantial relevance to medical and healthcare provision, and highlight an ongoing need to recognize and counter racism among healthcare providers. A critical starting point in such endeavors is a more rigorous, sophisticated and systematic approach to monitoring racism among healthcare providers. Concurrently, the implementation and evaluation of multi-strategy, evidence-based, anti-racism approaches that dispel false beliefs and counter stereotypes, build empathy and perspective taking, develop personal responsibility and positive group norms, as well as promote intergroup contact and intercultural understanding73 within healthcare settings is also required.

Studies included in this review were almost solely conducted with physicians in the U.S. As a result meaningful comparison of differences in racism between provider categories was not possible. Further research is required to examine and compare racism among healthcare providers from other professional backgrounds (although, see Halanych et al.),74 and in countries outside of the U.S. The literature also suffers from limited information on racism experienced by patients of non-African American backgrounds (although, see Blair et al.).75

Although studies in this review used a number of measurement approaches (surveys, vignettes and computer-based indirect measures), the range of constructs measured was limited. Furthermore, only five studies utilized both direct and indirect approaches. Direct and indirect measures each have limitations that can be minimized by including both approaches in the same study.11 Self-completed surveys are subject to a range of biases, particularly social desirability.76 They are also unable to provide direct evidence of impact as the extent to which racist attitudes or beliefs translate into poorer healthcare varies. Vignettes can also subject to social desirability bias if participants are aware of the study aims. Physicians may respond differently to vignette than to actual clinical encounters. In addition, written vignettes may be less accurate than audio-visual recordings (although subtle differences between actors’ appearances and non-verbal cues may also affect audio-visual approaches). The majority of vignettes included factors such as age, gender and race/ethnicity. However, other factors such as socioeconomic status, employment status, and family situation can influence study findings.

Studies predominantly assessed general knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, emotions and behaviors towards racial groups, without detailing specific constructs or distinguishing between in-group favoritism and out-group derogation. In-group favoritism is defined as positive orientations towards one’s own racial/ethnic group, while out-group derogation constitutes negative orientations towards other racial/ethnic groups. Empirical evidence demonstrates that associations between in-group favoritism and out-group derogation can be negative, zero, or positive.77 As such, studies that do not differentiate between these constructs may be misleading, in that efforts to address prejudice against specific minority groups will differ from those aimed at reducing favored treatment for one’s own ethnic/racial group.78 Although central to social identity theory (a key psychological theory of racism)79 and despite calls to study in-group favoritism among healthcare providers,74 only one study included in this review assessed both in-group favoritism and out-group derogation.23

Unlike the Implicit Association Test, priming tasks are able to distinguish between in-group favoritism and out-group derogation.80 Moreover, priming tasks may more accurately capture associations in memory because they are designed to operate subliminally beyond conscious intention.67 This is especially the case when masks (i.e. symbols unrelated to the study topic) are used before and after the prime to reduce the visibility of the prime. It is notable that the two studies in this review using affective priming tasks only masked after (rather than also before) the prime,53,71 possibly compromising prime ‘invisibility’.

Despite a long history in other settings such as employment and housing,81 and calls for adoption in healthcare settings,9 no identified studies utilized paired-audit studies. Such studies could involve, for example, patients of different race/ethnicity (indicated by accent), but matched on other relevant characteristics such as phoning an emergency medicine department/hotline and enacting a set script. Any differences in provider behavior would then be attributable to ‘patient’ race/ethnicity.

Asking healthcare providers to assess their own level of racism through items such as ‘When working with minority individuals, I am confident that my conceptualization of client problems do not consist of stereotypes and biases’26 is likely to trigger strong social desirability bias that threatens response validity. It may be possible to minimize social desirability bias using computer-based speeded self-report tasks to assess ‘gut reaction’ to a particular topic (e.g. where participants are required to indicate negative or positive responses to questions within 700 milliseconds). After responding to questions on unrelated topics or completing other tasks (e.g., scenario responses), questions focused on the same topic (with no response deadline) can be asked, comparing these considered answers with ‘gut reactions’.22

Recent scholarship has identified warmth/good-naturedness towards, and perceived competence/capability of, racial/ethnic groups as key dimensions driving emotions that, in turn, drive racism.82 However, only two studies included in this review assessed warmth towards minority groups,35,36 with none assessing perceived competence. Future studies should utilize validated scales to assess good-naturedness/warmth, competence/capability, as well as the consequent emotions of admiration/ pride, envy/jealousy, pity/sympathy and contempt/disgust.83

Although no measures identified in this review assessed this, stereotyping is a cognitive process that can’t be effectively suppressed or denied, but rather needs to be recognized and accepted to avoid discriminatory behavior.84,85 Example items used to measure this understanding include: ‘It’s OK to have prejudicial thoughts or racial stereotypes’ and ‘When I evaluate someone negatively, I am able to recognize that this is just a reaction, not an objective fact’.86

Explicit prejudice reduction requires cognitive change through egalitarianism-related, non-prejudicial goals and increased awareness of contemporary racism,87 whereas implicit prejudice reduction requires decreased fear of, and positive contact with, members of a specific group.87 However, only two reviewed studies assessed awareness of contemporary racism, fear/anxiety and intergroup contact,23,32 with no studies examining egalitarianism or motivation to respond without prejudice. Meritocracy, just-world beliefs88 and White racial identity, privilege and guilt89 are also important constructs that were assessed in only two of the included studies.27,28

Other important constructs that remain unexamined to date include ideologies such as color-blindness (i.e., treating everyone the same regardless of their race/ethnicity), multiculturalism (i.e., recognition and celebration of racial/ethnic difference) and anti-racism (i.e., targeted efforts to address racial disparities through, for example, affirmative action),90 genetic determinism (i.e., genes determine life chances)91 and essentialism (i.e., differences between racial/ethnic groups are natural and inherent),92 perceived status differences (i.e., prestige/success of racial/ethnic groups),93 medical authoritarianism (i.e., belief in hierarchical relationships between providers and patients),94 social dominance orientation (i.e., belief that some racial/ethnic groups are or should be superior to others)95 and materialism (i.e., the important of acquiring and owning possessions),96 as well as realistic threat (e.g., migrants ‘stealing’ jobs) and symbolic threat (e.g., migrants jeopardizing national values).97

Given the extensive research conducted on patient–provider communication,13,98,99 the relationship between racism and communication requires investigation (e.g., Hagiwara).100 Such research should examine evaluative concerns (e.g., when anxiety about appearing prejudiced is interpreted as prejudice itself) and stereotype threat (e.g., when thinking about common stereotypes, such as being a non-compliant patient, inadvertently causes behavior that aligns with these stereotypes).101–103 This could include emerging research on the counter-intuitive effects of complimentary stereotypes and positive feedback.104,105 Furthermore, a virtual immersive environment (i.e. an audio-visual virtual reality simulation in which providers can interact with computer-generated characters and manipulate objects) could increase realism of vignettes.106

It is also notable that none of the included studies examined a combination of racist beliefs, emotions and behaviors/practices. Although two experimental studies suggest causal relationships between stereotypes, emotions and behaviors,82 two meta-analyses and a study utilizing multiple national probability samples reveal only moderate correlations (0.32–0.49) between racist beliefs, emotions and behavior.107–109 Such findings indicates the need to explore how, and to what extent, racist attitudes and beliefs drive healthcare provider behavior and decision-making.9

Despite a burgeoning interest in racism as a contributor to these disparities, we still know relatively little about the extent of healthcare provider racism or how best to measure it. This review provides evidence that healthcare provider racism exists, and demonstrates a need for more sophisticated approaches to assessing and monitoring it.

Acknowledgements

Contributors

Ms Kaitlin Lauridsen assisted in preparing this paper.

Funders

Naomi Priest is supported by an NHMRC postdoctoral training fellowship (#628897) and by the Victorian Health Promotion Foundation (VicHealth).

Prior Conference Presentations

a) Science of Discrimination and Health Meeting, National Institute of Health, Washington DC, USA, 2011; b) Science of Eliminating Health Disparities Summit, Maryland, USA, 2012.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that they do not have any conflicts of interest.

Appendix

Table 2.

Example of Search Strategy for Electronic Databases. The Following Search Strategy Was Modified for Use in Other Databases, Where Appropriate. Medline (ISI):

| Order | Search terms |

|---|---|

| 1. | TI = (doctor* or physician* or nurs* or clinician* or provider* or pracitioner* or therapist*) |

| 2. | MH = (“allied health personnel” OR “dental staff” OR dentists OR health educators“ OR infection control practitioners” OR “medical staff” OR “nurses” OR “nursing staff” OR “personnel, hospital” OR pharmacists OR physicians) |

| 3. | TI = (Racis* OR Discrimin* or Prejudic* or Belief* or Attitud* or Stereotyp*) |

| 4. | TI = (rac* or cultur* or religio* or ethnic*) |

| 5. | 1 or 2 |

| 6. | 3 and 4 |

| 7. | 5 and 6 |

Contributor Information

Yin Paradies, Phone: +61-3-92443873, Email: yin.paradies@deakin.edu.au.

Mandy Truong, Phone: +61-3-93482832.

Naomi Priest, Phone: +61-3-93482832.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bhopal R. Chronic diseases in Europe’s migrant and ethnic minorities: challenges, solutions and a vision. Eur J of Public Health. 2009;19(2):140–143. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckp024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Frohlich KL, Ross N, Richmond C. Health disparities in Canada today: some evidence and a theoretical framework. Health Policy. 2006;79:132–143. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2005.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nazroo JY, Karlsen S. Ethnic inequalities in health: social class, racism and identity. In Research Findings from the Health Variations Program. 2001 September.

- 4.Takeuchi DT, WIlliams DR. Past insights, future promises: race and health in the twenty-first century. Du Bois Rev. 2011;8(1):1–3. doi: 10.1017/S1742058X11000154. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Larson PA. Nurse perceptions of patient characteristics. Nurs Res. 1977;26(6):416–421. doi: 10.1097/00006199-197711000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR. Unequal treatment: Confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care. Report of the Committee on Understanding Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Klonoff EA. Disparities in the provision of medical care: an outcome in search of an explanation. J Behav Med. 2009;32(1):48–63. doi: 10.1007/s10865-008-9192-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kressin NR, Raymond KL, Manze M. Perceptions of race/ethnicity-based discrimination: a review of measures and evaluation of their usefulness for the health care setting. J Health Poor U. 2008;19(3):697–730. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shavers VL, Fagan P, Jones D, al. E. The state of research on racial/ethnic discrimination in the receipt of health care. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(5):953–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Berman G, Paradies Y. Racism, disadvantage and multiculturalism: towards effective anti-racist praxis. Ethn Racial Stud. 2010;33(2):214–232. doi: 10.1080/01419870802302272. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blank RM, Dabady M, Citro CF. Measuring racial discrimination. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Van Ryn M. Research on the provider contribution to race/ethnicity disparities in medical care. Med Care. 2002;40(1):140–150. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200201001-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Van Ryn M, Fu SS. Paved with good intentions: do public health and human service providers contribute to racial/ethnic disparities in health? Am J Public Health. 2003;93(2):248–255. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.93.2.248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gee GC, Ford CL. Structural racism and health inequities, old issues, new directions. Du Bois Rev. 2011;8(1):115–132. doi: 10.1017/S1742058X11000130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Paradies Y. A systematic review of empirical research on self-reported racism and health. Int J Epidemiol. 2006;35(4):888–901. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyl056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Williams DR, Mohammed SA. Discrimination and racial disparities in health: evidence and needed research. J Behav Med. 2009;32(1):20–47. doi: 10.1007/s10865-008-9185-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Monrouxe LV. Identity, identification and medical education: why should we care? Med Educ. 2010;44:40–49. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2009.03440.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kavanagh J, Oliver S, Lorenc T. Reflections on developing and using PROGRESS-PLUS. Equity Update. 2008:1–3.

- 19.Cardiff University. Health Evidence Bulletins Wales: Critical appraisal checklists. Cardiff University, Cardiff, Wales. 2008. http://hebw.cf.ac.uk/projectmethod/appendix5.htm#top. 2011. Last accessed 14 June 2013.

- 20.De Houwer J, Moors A. Implicit measures: Similarities and differences. In: Gawronski B, Payne BK, editors. Handbook of implicit social cognition: measurement, theory, and applications. New York: The Guilford Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Strack F, Deutsch R. Reflective and impulsive determinants of social behavior. Pers Soc Psychol Rev. 2004;8(3):220–247. doi: 10.1207/s15327957pspr0803_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ranganath KA, Smith CT, Nosek BA. Distinguising automatic and controlled components of attitudes from direct and indirect measurement methods. J Exp Soc Psychol. 2008;44(2):386–396. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2006.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *23.Van Ryn M, Burke J. The effect of patient race and socio-economic status on physicians’ perceptions of patients. Soc Sci Med. 2000;50(6):813–828. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(99)00338-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *24.Penner LA, Dovidio J, et al. Aversive racism and medical interactions with Black patients: a field study. J Exp Soc Psychol. 2010;46:436–440. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2009.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *25.Michaelsen J, Krasnik A, Nielsen A, Norredam M, Torres AM. Health professionals’ knowledge, attitudes, and experiences in relation to immigrant patients: a questionnaire study at a Danish hospital. Scand J Public Health. 2004;32(4):287–295. doi: 10.1080/14034940310022223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *26.Middleton RA, Stadler HA, Simpson C, et al. Mental health practitioners: the relationship between white racial identity attitudes and self-reported multicultural counseling competencies. J Couns Dev. 2005;83:444–456. doi: 10.1002/j.1556-6678.2005.tb00366.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- *27.Constantine MG, Juby HL, Liang JJ. Examining multicultural counseling competence and race-related attitudes among white marital and family therapists. J MaritalFam Ther. 2001;27(3):353–388. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-0606.2001.tb00330.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *28.Paez KA, Allen JK, Carson KA, Cooper LA. Provider and clinic cultural competence in a primary care setting. Soc Sci Med. 2008;66(5):1204–1216. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.11.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *29.Mitchell AA, Sedlacek WE. Ethnically sensitive messengers: an exploration of racial attitudes of health-care workers and organ procurement officers. J Natl Med Assoc. 1996;88(6):349–352. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *30.Noble A, Engelhardt K, Newsome-Wicks M, Woloski-Wruble AC. Cultural competence and ethnic attitudes of midwives concerning jewish couples. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2009;38(5):544–555. [DOI] [PubMed]

- *31.Joseph HJ. Attitudes of army nurses toward African American and Hispanic patients. Mil Med. 1997;162(2):96–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *32.Green RG, Kiernan-Stern M, Baskind FR. White social workers’ attitudes about people of color. J Ethn Cultural Divers Soc Work. 2005;14(1–2):47–68. doi: 10.1300/J051v14n01_03. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- *33.Pagotto L, Voci A, Maculan V. The effectiveness of intergroup contact at work: mediators and moderators of hospital workers’ prejudice towards immigrants. J Community Soc Psychol. 2010;20:317–330. doi: 10.1002/casp.1038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- *34.Moskowitz D, Thom DH, Guzman D, Penko J, Miaskowski C, Kushel M. Is primary care providers’ trust in socially marginalized patients affected by race? J Genl Intern Med. 2011;26(8):846–851. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1672-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *35.Sabin JA, Rivara FP, Greenwald AG. Physician implicit attitudes and steretypes about race and quality of medical care. Med Care. 2008;46(7):678–685. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181653d58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *36.Green AR, Carney DR, Pallin DJ, et al. Implicit bias among physicians and its prediction of thrombolysis decisions for black and white patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(9):1231–1238. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0258-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *37.Sabin JA, Nosek BA, Greenwald AG, Rivara FP. Physicians’ implicit and explicit attitudes about race by md race, ethnicity, and gender. J Health Poor U. 2009;20:896–913. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ponterotto JG, Potere JC, Johansen SA. The quick discrimination index: normative data and user guidelines for counseling researchers. J Multicultural Couns D. 2002;30:192–207. doi: 10.1002/j.2161-1912.2002.tb00491.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sedlacek W, Brooks G., Jr Measuring racial attitudes in a situational context. Psychol Rep. 1970;27:971–980. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1970.27.3.971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bonaparte B. Ego defensiveness, open-closed mindedness, and nurses’ attitudes toward culturally different patients. Nurs Res. 1979;28(3):166–172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rooda LA. Knowledge an attitudes of nurses towards culturally diverse patients. [Dissertation] West Layfayette: Purdue University; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jacobson CK. Resistance to affirmative action: self-interest or racism? J Confl Resolut. 1985;29(2):306–329. doi: 10.1177/0022002785029002007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ponterotto JG, Gretchen D, Utsey SO, Rieger BP, Austin R. A revision of the Multicultural Counseling Awareness Scale. J Multicult Couns D. 2002;30:153–180. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jetten PJ, Ellemers N. Minority hostility and resistance: The interplay between majority rejection and minority goals. The University of Queensland 2010–2012.

- 45.Hornsey MJ, Wohl MJ. Promoting intergroup forgiveness: The benefits and pitfalls of apologies and invocations of shared humanity. The University of Queensland 2010–2012.

- 46.Brigham J. College students’ racial attitudes. J App Psychol. 1993;23:1933–1967. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-1816.1993.tb01074.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.McConahay AR. Modern racism, ambivalence, and the modern racism scale. In: Dovidio JF, Gaertner SL, editors. Prejudice, discrimination, and racism. Orlando: Academic Press; 1986. pp. 91–125. [Google Scholar]

- *48.Todd KH, Deaton C, D’Adamo AP, Goe L. Ethnicity and analgesic practice. Ann Emerg Med. 2000;35(1):11–16. doi: 10.1016/S0196-0644(00)70099-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *49.Hirsh AT, Jensen MP, Robinson ME. Evaluation of nurses’ self-insight into their pain assessment treatment decisions. J Pain. 2010;11(5):454–461. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2009.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *50.Kales HC, Neighbors HW, Valenstein M, et al. Effect of race and sex on primary care physicians’ diagnosis and treatment of late-life depression. J Am Geriar Soc. 2005;53(5):777–784. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53255.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *51.Kales HC, Neighbors HW, Blow FC, et al. Race, gender, and psychiatrists’ diagnosis and treatment of major depression among elderly patients. Psychiatr Serv. 2005;56(6):721–728. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.56.6.721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *52.McKinlay JB, Burns RB, Durante R, et al. Patient, physician and presentational influences on clinical decision making for breast cancer: results from a factorial experiment. J Eval Clin Pract. 1997;3(1):23–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.1997.tb00067.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *53.Stepanikova I. Inequality in quality: toward a better understanding of micro-mechanisms underlying racial/ethnic dispartiies in American health care [Dissertation]. Standford University 2006.

- *54.Burgess DJ, Crowley-Matoka M, Phelan S, et al. Patient race and physicians’ decisions to prescribe opioids for chronic lower back pain. Soc Sci Med. 2008;67:1852–1860. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *55.Weisse CS, Sorum PC, Sanders KN, Syat BL. Do gender and race affect decisions about pain management? J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:211–217. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016004211.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *56.Schulman KA, Berlin JA, Harless W, et al. The effect of race and sex on physicians’ recommendations for cardiac catherization. New Engl J Med. 1999;340(8):618–626. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199902253400806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *57.Thamer M, Hwang W, Fink NE, et al. U.S. Nephrologists’ attitudes towards renal transplantation: results from a national survey. Transplantation. 2001;71(2):281–288. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200101270-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *58.Di Caccavo A, Fazal-Short N, Moss TP. Primary care decision making in response to psychological complaints: The influence of patient race. J Community Appl Psychol. 2000;10(1):63–67. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1298(200001/02)10:1<63::AID-CASP533>3.0.CO;2-J. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- *59.Bogart LM, Catz SL, Kelly JA, Benotsch EG. Factors influencing physicians’ judgments of adherence and treatment decisions for patients with HIV disease. Med Decis Mak. 2001;21:28–36. doi: 10.1177/0272989X0102100104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *60.Al-Khatib SM, Sanders GD, O’Brien SM, et al. Do physicians’ attitudes toward implantable cardioverter defibrillator therapy vary by patient age, gender, or race? Ann Noninvasive Electrocardiol. 2011;16(1):77–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1542-474X.2010.00412.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *61.Cabral ED, Caldas AF, Jr, Cabral HAM. Influence of the patient’s race on the dentist’s decision to extract or retain a decayed tooth. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2005;33:461–466. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2005.00255.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *62.Barnhart JM, Wassertheil-Smoller S. The effect of race/ethnicity, sex, and social circumstances on coronary revascularization preferences. A vignette comparison. Cardiol Rev. 2006;14(5):215–222. doi: 10.1097/01.crd.0000214180.24372.d5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *63.Weisse CS, Sorum PC, Dominguez RE. The influence of gender and race on physicians’ pain management decisions. J Pain. 2003;4(9):505–510. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2003.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *64.McKinlay J, Lin T, Freund K, Moskowitz M. The unexpected influence of physician attributes on clinical decisions: results of an experiment. J Health Soc Behav. 2002;43:92–106. doi: 10.2307/3090247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *65.Drwecki B. An experimental investigation of the causes of and solutions to racial pain treatment bias [dissertation]. University of Wisconsin-Madison; 2011.

- 66.Greenwald AG, McGhee DE, Schwartz JLK. Measuring individual differences in implicit cognition: The Implicit Association Test. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1998;74:1464–1480. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.74.6.1464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gawronski B, Deutsch R, Banse R. Response interference tasks as indirect measures of automatic associations. In: Klauer KC, Voss A, Stahl C, editors. Cognitive methods in social psychology. New York: Guilford Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Degner J, Wentura D. Automatic prejudice in childhood and early adolescence. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2010;98(3):356–374. doi: 10.1037/a0017993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *69.Cooper LA, Roter D, Carson K, Beach M, Sabin J, Greenwald AG. The associations of clinicians’ implicit attitudes about race with medical visit communication and patient ratings of interpersonal care. Am J Public Health. 2012;Online:e1-e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- *70.Moskowitz GB, Stone J, Childs A. Implicit stereotyping and medical decisions: unconscious stereotype activation in practitioners’ thoughts about African Americans. Am J Public Health. 2012;Online:e1-e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- *71.Abreu JM. Conscious and nonconscious African American stereotypes: impact on first impression and diagnostic ratings by therapists. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1999;67(3):387–393. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.67.3.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *72.Balsa AI, McGuire TG. Testing for statistical discrimination in health care. Health Serv Res. 2005;40(1):227–252. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2005.00351.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Paradies Y, Chandrakumar L, Klocker N, et al. Building on our strengths: a framework to reduce race-based discrimination and support diversity in Victoria. Melbourne: Victorian Health Promotion Foundation; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Halanych JH, Andreae L, Prince CP. The role of ancillary staff in perceived discrimination in medical care. The Science of Research on Discrimination and Health; Washington DC 2011.

- 75.Blair IV, Hayranek EP, PRice DW, et al. An assessment of biases against Latinos and African Americans among primary care providers and community members. The Science of Research on Discrimination and Health; Washington DC 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 76.Steenkamp J-BEM, de Jong MG, Baumgartner H. Socially desirable response tendencies in survey research. Journal of Marketing Research. 2010;XLVII:199–214.

- 77.Tausch N, Hewstone M, Kenworthy JB, et al. Secondary transfer effects of intergroup contact: Alternative accounts and underlying processes. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2010;99(2):282–302. doi: 10.1037/a0018553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Duckitt J, Callaghan J, Wagner C. Group identification and outgroup attitudes in four South African Ethnic Groups: A multidimensional approach. Pers Soc Psychol B. 2005;31(5):633–646. doi: 10.1177/0146167204271576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Al Ramiah A, Hewstone M, Dovidio J, Penner LA. The social psychology of discrimination: Theory, measurement and consequences In: Bond L, McGinnity F, Russell H, editors. Making equality count: Irish and international research measuring equality and discrimination. Dublin: Liffey Press; 2010. p. 84–112.

- 80.Gawronski B, LeBel EP, Peters KR. What do implicit measures tell us? Scrutinizing the validity of three common assumptions. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2007;2(2):181–193. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6916.2007.00036.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Rich J. Measuring discrimination: What do field experiments of markets tell us? In: Bond L, McGinnity F, Russell H, editors. Making equality count: Irish and international research measuring equality and discrimination. Dublin: LIffey Press; 2010. pp. 48–63. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Cuddy AJC, Fiske ST, Glick P. Behaviors from intergroup affect and stereotypes: the BIAS Map. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2007;92(4):631–648. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.92.4.631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Caprariello PA, Cuddy AJC, Fiske ST. Social structure shapes cultural stereotypes and emotions: A causal test of the stereotype content model. Group Process Intergr Relat. 2009;12(2):147–155. doi: 10.1177/1368430208101053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Burgess D, Van Ryn M, Dovidio J, Saha S. Reducing racial bias among health care providers: lessons from social-cognitive psychology. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(6):882–887. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0160-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kowal E, Franklin H, Paradies Y. Exploring reflexive antiracism as an approach to diversity training. Ethnicities. 2013;13(3):316–336. doi: 10.1177/1468796812472885. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Lillis J, Hayes SC. Applying acceptance, mindfulness, and values to the reduction of prejudice. Behavior Modif. 2007;31(4):389–411. doi: 10.1177/0145445506298413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Gawronski B, Brochu PM, Sritharan R, Strack F. Cognitive consistency in prejudice-related belief systems: Integrating old-fashioned, modern, aversive, and implicit forms of prejudice. In: Gawnronski B, Strack F, editors. Cognitive consistency: a fundamental principle in social cognition. New York: Guilford Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Ecclesston CP, Kaiser CR, Kraynak LR. Shifts in justice beliefs induced by Hurricane Katrina: The impact of claims of racism. Group Processes Intergr. 2010;13(5):571–584. doi: 10.1177/1368430210362436. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Pinterits EJ, Poteat VP, Spanierman LB. The White Privilege Attitudes scale: development and initial validation. J Couns Psychol. 2009;56(3):417–429. doi: 10.1037/a0016274. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Plaut VC. Diversity science: Why and how difference makes a difference. Psychol Inq. 2010;21:77–99. doi: 10.1080/10478401003676501. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Keller J. In genes we trust: The biological component of psychological essentialism and its relationship to mechanisms of motivated social cognition. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2005;88(4):686–703. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.88.4.686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Bastian B, Haslam N. Psychological essentialism and stereotype endorsement. J Exp Soc Psychol. 2009;42:228–235. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2005.03.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Fiske ST, Cuddy AJC, Glick P, Xu J. A model of (often mixed) stereotype content: Stereotype competence and warmth respectively follow from perceived status and competition. J Pers Soc Psych. 2002;82(6):878–902. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.82.6.878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Burgess DJ, Dovidio J, Phelan S, Van Ryn M. The effect of medical authoritarianism on physicians’ treatment decisions and attitudes regarding chronic pain. J Appl Soc Psychol. 2011;41:1399–1420. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-1816.2011.00759.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Sidanius J, Pratto F. Social dominance: An intergroup theory of social hierarchy and oppression. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Roets A, Van Hiel A, Cornelis I. Does materialism predict racism? Materialism as a distinctive social attitude and a predictor of prejudice. Euro J Personality. 2006;20:155–168. doi: 10.1002/per.573. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Riek BM, Mania EW, Gaertner SL. Intergroup threat and outgroup attitudes: A meta-analytic review. Pers Soc Psychol B. 2006;10(4):336–353. doi: 10.1207/s15327957pspr1004_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Gordon HS, Street RL, Jr, Sharf BF, Souchek J. Racial differences in doctors’ information-giving and patients’ participation. Cancer. 2006;107(6):1313–1320. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Johnson RL, Roter DL, Powe NR, Cooper LA. Patient race/ethnicity and quality of patient-physician communication during medical visits. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(12):2084–2090. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.94.12.2084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Hagiwara N, Penner LA, Eggly S, Albrecht TL. Perceived discrimination, implicit bias, and adherence to physician recommendations. The Science of Research on Discriminiation and Health; Washington DC 2010.