Abstract

BACKGROUND

Alcohol consumption and its interaction with disease, medication use, and functional status may result in serious health problems, but little information exists about the national prevalence of alcohol-related health risk in older adults.

OBJECTIVE

To estimate the prevalence of harmful and hazardous alcohol use and the prevalence of consumption in excess of National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) recommendations, in people aged 65 and older, and by sex and race/ethnicity sub-group.

DESIGN

Cross-sectional, using data from the 2005–2008 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey of the non-institutionalized U.S. population.

PARTICIPANTS

One thousand and eighty-three respondents aged 65 and older who consume alcohol.

MAIN MEASURES

Participants’ alcohol consumption was classified as Harmful, Hazardous, or Healthwise, in the context of their specific health status, using the Alcohol-Related Problems Survey classification algorithm.

KEY RESULTS

Overall, 14.5 % of older drinkers (95 % CI: 12.1 %, 16.8 %) consumed alcohol above the NIAAA’s recommended limits. However, when health status was taken into account, 37.4 % of older drinkers (95 % CI: 34.9 %, 40.0 %) had Harmful consumption and 53.3 % (95 % CI: 50.1 %, 56.6 %) had either Hazardous or Harmful consumption. Among light/moderate drinkers, the proportions were 17.7 % (95 % CI: 14.7 %, 20.7 %) and 28.0 % (95 % CI: 24.8 %, 31.1 %), respectively. Male drinkers had significantly greater odds of Hazardous/Harmful consumption than female drinkers (OR = 2.14 [95 % CI: 1.77, 2.6]). Black drinkers had worse health status and significantly greater odds of Hazardous/Harmful consumption than white drinkers (OR = 1.49; 95 % CI: 1.02, 2.17), despite having no greater prevalence of drinking in excess of NIAAA-recommended limits.

CONCLUSION

Most older Americans who drink are light/moderate drinkers, yet substantial proportions of such drinkers drink in a manner that is either harmful or hazardous to their health. Older adults with risky alcohol consumption are unlikely to be identified by health care providers if clinicians rely solely on whether patient consumption exceeds the NIAAA-recommended limits.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s11606-013-2577-z) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

KEY WORDS: aging, epidemiology, alcohol-related risk

Many older adults have chronic health conditions and functional limitations.1 Despite evidence supporting the health benefits of light to moderate alcohol consumption,2,3 some chronic illnesses become more difficult to treat or are worsened by alcohol consumption.4,5 Further, polypharmacy is common among older adults, and alcohol can either enhance or diminish the effects of different medications and contribute to adverse drug events, falls, and accidental injuries.6,7 The National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) identifies people aged 65 and older as a special population for whom alcohol consumption, and in particular binge drinking, may pose an increased risk of significant health problems.8

The NIAAA also recommends that men aged 65 and younger consume no more than 14 alcoholic drinks (e.g., 5 fl. oz. wine, 12 fl. oz. beer, or 1.5 fl. oz. spirits) per week and no more than four per day.9 For women of all ages and men older than 65, the NIAAA recommends consuming no more than seven alcoholic drinks per week and no more than three per day.9 The NIAAA recommends that the risks posed by alcohol consumption, especially in older adults, should be evaluated by the patient’s physician in light of the individual’s pattern of consumption and health status.9

Scant information is currently available about the prevalence of alcohol-related health risk among older adults when individual comorbidities, medication use, functional status, and recent symptoms are also considered. In two reports of older primary care patients who consumed alcohol, the prevalence of alcohol-related health risk was approximately 46–47 %,10,11 but national-level data about risk prevalence do not exist. Instead, most estimates of alcohol-related problems in older adults focus on binge drinking, come from hospital admissions or psychiatric patient data, or are based on criteria for alcohol abuse and dependence.12–14

This study was designed to estimate the prevalence of alcohol-related health risk among U.S. drinkers aged 65 and older, and more specifically, the prevalence of alcohol-related health risk in older adults whose consumption was light/moderate (i.e., did not exceed the NIAAA’s general recommendations for those aged 65 and older). Its secondary purpose was to examine sex and racial/ethnic differences in prevalence. Women have been shown to experience negative effects of alcohol consumption at lower levels than men,15,16 and there are racial/ethnic disparities in the prevalence of chronic conditions, such as hepatitis17,18 and high blood pressure, that can be worsened by alcohol use.19

METHODS

Additional methodology details are available in the online appendix.

National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES)

NHANES is an ongoing national survey 20 that uses a well-described, complex, multistage probability sampling design and weighting methodology to obtain prevalence estimates and measures of association that represent the civilian, non-institutionalized US population.21 Data are collected by interview, physical examination, and blood and urine sample analyses. NHANES contains detailed information on respondents’ self-reported medical diagnoses, medications, symptoms, functional status, and risk behaviors such as smoking and alcohol consumption.

For this study, we combined the 2005–2006 and 2007–2008 NHANES cycles, which provided the most complete data relevant to the evaluation of alcohol-related risk. Inclusion criteria were adults aged 65 and older who reported consuming at least one alcoholic drink in the past 12 months.

The Alcohol-Related Problems Survey (ARPS) Risk Classification Algorithm

The ARPS is an alcohol-related health risk education system for use in screening older patients for potentially hazardous and harmful alcohol consumption. It identifies the specific sources of that risk and can provide personalized reports to individual and their physicians.11,22,23 Its development, psychometric properties, and research use are well-documented.10,11,22–26 Briefly, Moore and colleagues used the Longitudinal Expert All Data (LEAD) standard27 to evaluate the concurrent validity of ARPS, and found in one study that the ARPS had a sensitivity of 0.93 and a specificity of 0.66 for hazardous or harmful alcohol consumption,22 and in another study, a sensitivity of 0.82 and specificity of 0.82.23

The ARPS uses World Health Organization terminology 28,29 to classify alcohol-related health risk into three categories: Harmful (consumption that may exacerbate or complicate existing alcohol-related problems), Hazardous (consumption that poses risks of future harm for individuals with specific medical condition[s], functional status, or symptoms, taking specific medication[s], or engaging in risky behaviors such as smoking), and Healthwise (neither Harmful nor Hazardous and potentially beneficial).

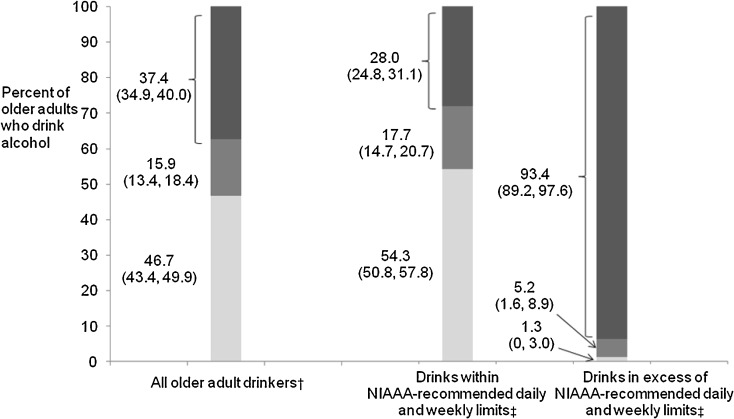

The ARPS algorithm first considers a person’s reported quantity and frequency of consumption in relation to each of 63 factors, including medical problems, medication use, symptoms, binge drinking, sex, and functional status. Figure 1 illustrates the consumption patterns (quantity and frequency) that are considered to be harmful, hazardous, or healthwise if an individual has hypertension. Alternatively, a different set of consumption patterns is considered for an individual with mouth/throat cancer, for whom any alcohol consumption is considered harmful. The specific consumption patterns that confer risk vary substantially depending on the factor being considered.

Figure 1.

Example of two-step ARPS classification of risk* for an individual with hypertension. * hw=healthwise, hz=hazardous, hm=harmful.

The factor-specific risk classifications are then aggregated to obtain an overall alcohol-related risk classification for an individual. A classification of harmful on ≥ 1 factor results in an overall classification of an individual’s alcohol consumption as Harmful, as does a classification of hazardous on ≥ 3 specific factors. A classification of hazardous on ≤ 2 factors, with no harmful classification, results in an individual’s overall classification as Hazardous. Otherwise, the individual’s consumption is classified as Healthwise.

Application of the ARPS Algorithm to NHANES Data

NHANES questions ALQ120Q, ALQ120U, and ALQ130 provided data on consumption quantity and frequency within the past 12 months. We used this information to determine conformance to NIAAA’s recommended consumption limits. Data from questions ALQ140Q and ALQ140U, which asked about frequency of consuming five alcoholic drinks on at least 1 day in the past 12 months, were used to identify binge drinking.

The 2005–2008 NHANES provided information on 47 of the 63 ARPS factors. Sensitivity analyses were conducted to assess the impact on prevalence estimates of the lack of information on those factors not available in NHANES. Additional details about the sensitivity analyses are presented in the online appendix.

Statistical Analysis

The national prevalence of Healthwise, Hazardous and Harmful alcohol consumption was estimated using the 4-year Mobile Examination Center (MEC) weights, the appropriate weights for our analytic subpopulation per NHANES guidelines.22 Prevalence estimates were calculated for the elderly drinking population as a whole and for specific sub-groups defined by age (65–69 years, 70–74 years, 75–79 years, and ≥ 80 years), sex, and race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic black and non-Hispanic white), and also for the four race-sex categories of non-Hispanic white and black, male and female drinkers. Differences in the sampling of Hispanic respondents between the 2005–2006 and 2007–2008 cycles make it impossible to examine differences in risk classification for Hispanics overall, or for specific Hispanic sub-groups.30

Risk classification prevalence was also estimated among those who consumed alcohol within the NIAAA limits. Prevalence odds ratios (and 95 % CI) were estimated due to the cross-sectional nature of NHANES, adjusted for age, sex, and race/ethnicity, for: 1) the odds of being classified as having either Hazardous or Harmful (Hazardous/Harmful) alcohol consumption and 2) the odds of being classified as having Harmful alcohol consumption, among those classified as having Hazardous/Harmful consumption,.

All analyses were executed using the SURVEYFREQ and SURVEYLOGISTIC procedures in SAS Version 9.0. Group differences were evaluated using α = 0.05. Variance estimates were adjusted to account for the complex survey design using the Taylor Series Linearization method within SAS. No unreliable estimates were found; all relative standard errors of the estimates were < 30 %, per NHANES guidelines.

RESULTS

Demographic Characteristics

Of the 2,593 NHANES respondents who were aged 65 and older in 2005–2008, 1,083 (weighted n = 16,771,716 or 46.4 %) reported consuming at least one alcoholic drink in the past year. Men comprised 51.1 % of older drinkers; 88.8 % were white and non-Hispanic (Table 1). The proportion of current drinkers in the population decreased in each successive 5-year age group. More than half of those 65–69 years old were drinkers, compared with one-third of those who were at least 80 years old.

Table 1.

Characteristics of U.S. Adults Aged 65 and Older, by Drinking Status, N = 36,136,889,* NHANES, 2005–2008

| Characteristic | All adults aged 65 and older N = 36,136,889 | Non-drinkers aged 65 and older N = 19,365,173† | Drinkers aged 65 and older N = 16,771,716‡ |

|---|---|---|---|

| Percent (No. in thousands) | Percent (No. in thousands) | Percent (No. in thousands) | |

| Sex | |||

| Women | 57.5 (20,791) | 65.0 (12,586) | 48.9 (8,206) |

| Men | 42.5 (15,345) | 35.0 (6,779) | 51.1 (8,566) |

| Race | |||

| White | 83.0 (29,982) | 77.9 (15,090) | 88.1 (14,892) |

| Black | 8.3 (2,991) | 11.1 (2,150) | 5.0 (840) |

| Hispanic | 5.8 (2,081) | 6.6 (1,284) | 4.8 (797) |

| Other | 3.0 (1,082) | 4.3 (841) | 1.4 (241) |

| Age, y | |||

| 65–69 | 29.9 (10,791) | 24.4 (4,726) | 36.2 (6,064) |

| 70–74 | 24.4 (8,801) | 22.5 (4,365) | 26.5 (4,436) |

| 75–79 | 19.8 (7,169) | 21.0 (4,076) | 18.4 (3,093) |

| ≥80 | 25.9 (9,376) | 32.0 (6,198) | 18.9 (3,177) |

| Heavy drinking | |||

| No | 93.3 (33,707) | N/A§ | 85.5 (14,341) |

| Yes | 6.7 (2,427) | 14.5 (2,427) | |

| Binge drinking | |||

| No | 94.5 (34,118) | N/A§ | 88.3 (14,753) |

| Yes | 5.4 (1,954) | 11.7 (1,954) | |

| Frequency of alcohol consumption in past 12 months | |||

| Never | 53.6 (19,365) | 100 (1,936) | 0 (0) |

| ≤1 time a month | 18.1(6,557) | 0 (0) | 39.1 (6,557) |

| 2–4 times a month | 8.3 (2,995) | 0 (0) | 17.9 (2,995) |

| 2–3 times a week | 7.5 (2,710) | 0 (0) | 16.2 (2,710) |

| 4–5 times a week | 4.2 (1,514) | 0 (0) | 9.0 (1,514) |

| Daily/almost daily | 8.3 (2,995) | 0 (0) | 17.9 (2,995) |

| Quantity consumed on the days they drank | |||

| ≤1 drink | 63.5 (10,644) | ||

| 2 drinks | 23.7 (3,980) | ||

| 3 drinks | N/A§ | N/A§ | 7.3 (1,218) |

| 4 drinks | 3.3 (560) | ||

| ≥5 drinks | 2.2 (369) | ||

| Education | |||

| < High school | 28.5 (10,268) | 37.5 (7,242) | 18.0 (3,025) |

| High school | 29.8 (10,738) | 31.0 (5,989) | 44.2 (4,749) |

| > High school | 41.7 (15,056) | 31.4 (6,059) | 53.6 (8,997) |

| Missing | 0.2 (75) | 0.4 (75) | 0 (0) |

| Household income | |||

| ≤$19,999 | 25.9 (8,692) | 34.6 (6,142) | 16.2 (2,550) |

| $20,000–$34,999 | 29.7 (9,936) | 31.2 (5,540) | 27.9 (4,396) |

| $35,000–$54,999 | 23.1 (7,725) | 18.7 (3,325) | 27.9 (4,400) |

| $55,000–$74,999 | 8.4 (2,818) | 6.7 (1,181) | 10.4 (1,638) |

| $75,000 and over | 12.9 (4,322) | 8.8 (1,555) | 17.6 (2,767) |

| Missing | 7.3 (2,643) | 8.4 (1,622) | 6.1 (1,020) |

| Health insurance coverage | |||

| No | 1.6 (582) | 1.8 (347) | 1.4 (235) |

| Yes | 98.4 (35,490) | 98.2 (18,974) | 98.6 (16,517) |

| Missing | 0.2 (65) | 0.2 (45) | 0.2 (20) |

| Type of health insurance | |||

| Private only | 7.5 (2,640) | 7.8 (1,481) | 7.0 (1,159) |

| Public§ only | 40.5 (14,330) | 43.7 (8,260) | 36.8 (6,070) |

| Both | 52.1 (18,433) | 48.5 (9,167) | 56.2 (9,265) |

| Missing | 0.2 (734) | 0.3 (456) | 0.1 (277) |

| No. of current prescription medications, mean (SD) | 4.14 (0.08) | 4.50 (0.10) | 3.72 (0.11) |

* Unweighted sample size of adults ≥ 65 years old, n = 2,593

† Unweighted sample size of adults ≥ 65 who did not report drinking, n = 1,510

‡ Unweighted sample size of adults ≥ 65 who reported drinking, n = 1,083

§ Public insurance defined as Medicare (HIQ031B), Medi-Gap (HIQ031C), Medicaid (HIQ031D), Military (HIQ031F), Indian Health Service (HIQ031G), state (HIQ031H), and other government-provided health insurance (HIQ031I)

Prevalence of Hazardous and Harmful Alcohol Consumption

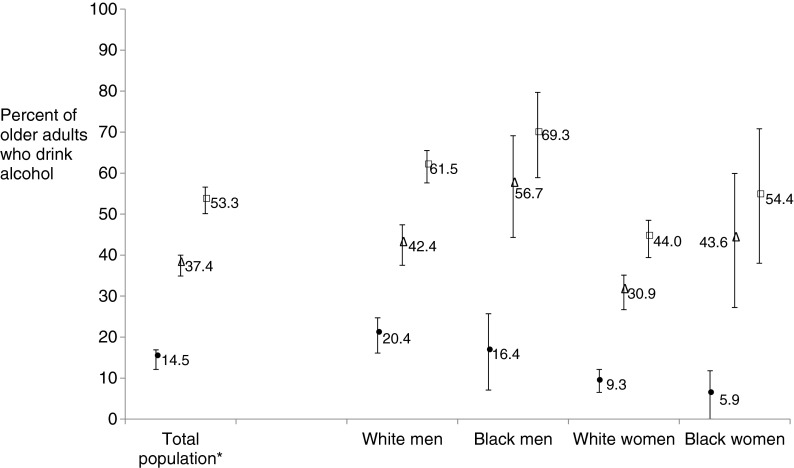

In the context of their medical problems, functional status, medications, and other health risks, 37.4 % of older adult drinkers (95 % CI: 34.9 %, 40.0 %) were classified as having Harmful consumption and 53.3 % (95 % CI: 50.1 %, 56.6 %) as having either Harmful or Hazardous consumption (Fig. 2). These proportions represented 17.3 % and 24.8 %, respectively, of the older US adult population in 2005–2008.

Figure 2.

Prevalence of alcohol consumption classified as Healthwise, Hazardous, and Harmful among adults aged 65 and older who drink alcohol (N = 16,771,716), overall and according to NIAAA-recommended limits, * NHANES 2005–2008.  * The NIAAA recommends daily and weekly alcohol consumption limits for men and women. For men aged 65 years and younger, the NIAAA recommends drinking no more than four alcoholic drinks in a day and no more than 14 drinks in a week. For women of all ages and men older than 65 years, the NIAAA recommends drinking no more than three alcoholic drinks a day and no more than seven drinks in a week.9 † Based on unweighted sample of

n

= 1,083 individuals ≥ 65 years old who drank alcohol, including

n = 917 older adults who drank alcohol within

the limits and

n

= 165 older adults who drank in excess of the limits. ‡ N

= 14,341,531 (85.5 %) of adults ≥ 65 years old who consume alcohol drank within the NIAAA-recommended daily and weekly limits. N

= 2,426,913

(14.5 %) of adults ≥ 65 years old who consume alcohol reported drinking more than the NIAAA-recommended daily or weekly limit.

* The NIAAA recommends daily and weekly alcohol consumption limits for men and women. For men aged 65 years and younger, the NIAAA recommends drinking no more than four alcoholic drinks in a day and no more than 14 drinks in a week. For women of all ages and men older than 65 years, the NIAAA recommends drinking no more than three alcoholic drinks a day and no more than seven drinks in a week.9 † Based on unweighted sample of

n

= 1,083 individuals ≥ 65 years old who drank alcohol, including

n = 917 older adults who drank alcohol within

the limits and

n

= 165 older adults who drank in excess of the limits. ‡ N

= 14,341,531 (85.5 %) of adults ≥ 65 years old who consume alcohol drank within the NIAAA-recommended daily and weekly limits. N

= 2,426,913

(14.5 %) of adults ≥ 65 years old who consume alcohol reported drinking more than the NIAAA-recommended daily or weekly limit.

Alcohol Consumption and Alcohol-Related Health Risk

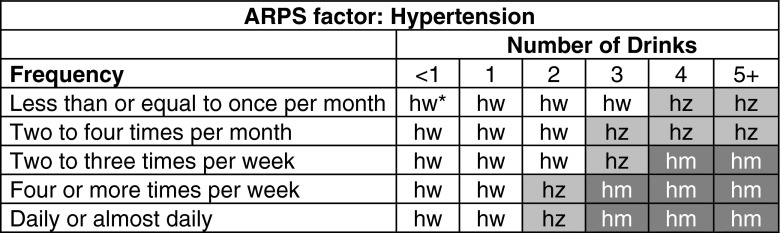

Most older adult drinkers consumed alcohol once a week or less (57.0 %), while 17.9 % drank daily or almost daily. On the days they consumed alcohol, the majority (63.5 %) consumed less than one drink. An estimated 14.5 % of older adult drinkers consumed alcohol in excess of the NIAAA-recommended limits. Approximately 11.7 % had at least one episode of binge drinking in the past 12 months. However, when considered in the context of their health status, the proportion whose alcohol consumption was classified as Hazardous/Harmful to their health (53.3 %) was nearly four-fold greater than the proportion whose consumption exceeded recommended limits (Fig. 3). Thirty-nine percent (39 %) of those whose consumption was classified as Hazardous/Harmful, including 24 % who already showed clinical signs of harm, would not be identified as having any risk if consumption in excess of NIAAA recommendations was the only factor considered (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Proportions and 95 % CIs of older adults drinking more than the NIAAA-recommended daily or weekly limit, and of older adults with an alcohol consumption classification of Harmful and Hazardous or Harmful, among adults aged 65 and older who drink alcohol, overall and by specific race-sex sub-groups, NHANES, 2005–2008.* * Based on unweighted sample of

n

= 1,083 individuals ≥ 65 years old who drank alcohol, including

n

= 450 white male drinkers, n

= 88 black male

drinkers, n

= 326 white female drinkers, and

n

= 53 black female drinkers.

* Based on unweighted sample of

n

= 1,083 individuals ≥ 65 years old who drank alcohol, including

n

= 450 white male drinkers, n

= 88 black male

drinkers, n

= 326 white female drinkers, and

n

= 53 black female drinkers.

Although 85.5 % of older adult drinkers (95 % CI: 83.2 %, 87.9 %) did not exceed the NIAAA daily or weekly recommended limits (Fig. 2), the alcohol consumption of nearly half of these moderate drinkers (45.7 %; 95 % CI: 42.1 %, 49.2 %) was still considered Harmful (28 %) or Hazardous (17.7 %) because of their health status. Further, 16.9 % of older adults who drank once a month or less and 35.1 % of those who consumed one drink or less on the days they drank were classified as having either Hazardous/Harmful consumption because of their health status.

Factors Associated with Hazardous or Harmful Alcohol Consumption

The factors most commonly responsible for the overall classification of individuals’ alcohol consumption as Hazardous/Harmful were the use of anti-hypertensive medications (51 %), recent depression/anxiety symptoms (25.7 %), physical limitations in dressing/bathing (25.5 %), and the quantity and frequency of alcohol consumption (25.2 %). The unique Healthwise, Hazardous, and Harmful consumption alcohol consumption patterns for these factors are detailed in the online appendix.

Sub-Group Differences

Prevalence

Male drinkers had a greater prevalence of Hazardous or Harmful consumption compared to female drinkers. The alcohol consumption of 43.4 % (95 % CI: 38.5 %, 48.3 %) of male drinkers was classified as Harmful, compared with 31.2 % among female drinkers (95 % CI: 27.5 %, 35.0 %). The alcohol consumption of an additional 19.1 % of men (95 % CI: 15.9 %, 22.3 %) and 12.6 % of women (95 % CI: 8.9 %, 16.3 %) was classified as Hazardous (overall p < 0.0001).

Just over half (50.6 %) of older black drinkers (95 % CI: 42.9 %, 58.3 %) had Harmful consumption, and their adjusted odds of a Hazardous/Harmful consumption classification was 1.5 times that of white drinkers (95 % CI: 1.02, 2.17; p = 0.04). Among those with Hazardous/Harmful consumption, black drinkers had 1.83 times the adjusted odds of being classified as having Harmful consumption (95 % CI: 1.03, 3.26; p = 0.04).

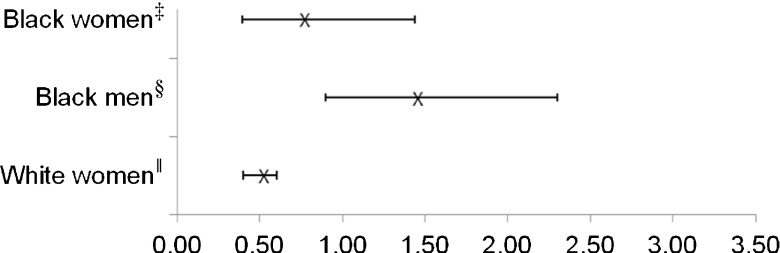

When stratified into four race-sex sub-groups, white female drinkers had half the adjusted odds of white male drinkers of having a Hazardous/Harmful consumption classification (Fig. 4). There were no race-sex subgroup differences in the odds of having Harmful consumption, among those with Hazardous/Harmful consumption. See the online appendix for more details.

Figure 4.

Adjusted odds ratios (OR) and 95 % CI for Hazardous or Harmful alcohol consumption, among adults aged 65 and older who drink alcohol, by race-sex sub-group (ref=white male drinkers), NHANES 2005–2008. *† *Multivariate models adjusted for age, race, and sex. † Based on unweighted sample size of n = 1,083 adults ≥ 65 years old who drink alcohol, including n = 450 white male drinkers, n = 88 black male drinkers, n = 326 white female drinkers, and n = 53 black female drinkers. ‡ OR Black female drinkers (OR) = 0.75 (95 % CI: 0.40, 1.44), p = 0.39. § OR Black male drinkers = 1.44 (95 % CI: 0.90, 2.30), p = 0.13. || OR White female drinkers = 0.49 (0.40, 0.60), p < 0.0001.

ARPS factors

Symptoms of depression/anxiety was a more prevalent factor in female drinkers (white and black) with Hazardous/Harmful consumption, and hepatitis was a more prevalent factor in black male drinkers with Hazardous/Harmful consumption (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

This report is the first to use information about older adults’ chronic conditions, prescription medication use, functional status, and recent symptoms to estimate the national prevalence of harmful and hazardous alcohol use in older US drinkers. In the period 2005–2008, nearly half of all older adult drinkers in the US, approximately 16.8 million adults, reported consuming alcohol, and 14.5 % of those drank in excess of the recommended limits. Using a risk screening algorithm that considers multiple health status indicators, we found a nearly four-fold greater number of older adults at risk for alcohol-related health problems than were identified by alcohol consumption that exceeds recommended limits for older adults. Moreover, the discrepancy between the proportion of heavy drinkers and the proportion whose alcohol consumption poses a health risk is especially marked in non-Hispanic black drinkers. The estimated more than six million older adult drinkers whose alcohol use was classified as Harmful constitute nearly one in five of all older adults (17 %) in the U.S.

These results are consistent with, and if anything more concerning, than the levels of risk found in studies that have used the ARPS screening algorithm in local, clinical populations. In 667 older adults in a study of the ARPs screening and education system in three large primary care group practices in Santa Monica, CA.,10,11 baseline alcohol consumption was Hazardous in 16.2 % and Harmful in 29.1 % of alcohol drinkers—a total of 45.3 % with Hazardous/Harmful consumption. The percentage who drank in excess of NIAAA-recommended limits for males and females ≥ 65 years in that population was only 3.9 %.

Significance of Findings

The present study confirms the general conclusion of the earlier studies that there is substantial alcohol-related harm and health risk in older adults, even among light-moderate drinkers. Older adults are infrequently screened for alcohol use,31 and when screened, are usually only queried about quantity and frequency and possibly indicators of alcohol abuse. The present results suggest that a very large proportion of older adults with alcohol-related health risk are unlikely to be identified as such by their physicians if that identification relies solely on whether their consumption exceeds the NIAAA-recommended limits. We found that consumption criteria alone can identify the estimated 36 % of drinkers with Harmful consumption who also drink more than the recommended limits, but they miss the 64 % whose drinking is harmful because of their hepatitis, depression, hypertension, inability to walk a block, etc., and miss 95 % of those whose alcohol consumption is hazardous because of those or other health considerations.

The critical importance of considering health status is further illustrated by our finding that alcohol-related health risk in is greater among black men and women who drink, despite their lower levels of consumption relative to white men and women, respectively. Health disparities between older black and white adults (e.g., in rates of hepatitis infection, hypertension, etc.), rather than differences in the quantity of alcohol consumption, underlie the racial disparity in alcohol-related risk.

Strengths and Limitations

The use of a carefully developed alcohol-related health risk screening tool for older adults, coupled with the use of NHANES data to obtain national population estimates, is the major strength of this study. We chose the ARPS risk classification algorithm for its rigorous development, evidence of construct validity, unique ability to consider a full range of relevant health indicators, and clinical use. The ARPS’ high sensitivity (0.88–0.93) but moderate specificity (0.66–0.88) reflects its intent as a screening, rather than a diagnostic, tool. Further, it was developed as part of a broader education program intended for use in a clinical setting where the clinician can confirm the patient’s risk classification and provide tailored explanatory information about the patient’s individual risk profile. Consequently, these findings are merely a beginning. Other approaches are needed to confirm and/or refine these estimates, and to evaluate such measures as predictors of future health status, adverse drug interactions, accidental injuries, and exacerbation of medical conditions.

NHANES is a cross-sectional survey, and as such, there are inherent limitations in interpreting prevalence estimates and prevalence odds ratios. And while NHANES provides the most appropriate, nationally representative source of data for our purpose, information was not available from either cycle on several factors that are relevant to identifying alcohol-related health risk, including information relevant to detecting alcohol abuse disorders. The sensitivity analyses suggest that, as would be expected, the lack of this information likely results in a modest underestimate of the extent of Harmful consumption—on the order of three percentage points. Even so, differences may exist in health characteristics between NHANES respondents and the Santa Monica trial participants 10 used for these analyses, and make it difficult to more precisely characterize the misestimation.

This study’s methods, and any alternative algorithms, can potentially be applied to the most recent and future NHANES survey cycles to track changes over time. Such algorithms necessarily must evolve as new drugs are developed that may interact with alcohol, other drugs are taken off the market or fall into disuse, or evidence is found of alcohol-related risks that were not previously appreciated. Such changes reflect the dynamic nature of medical science and clinical care and are arguably strengths in that they provide estimates that better reflect the potential for adverse effects of alcohol at any given point in time.

Implications

The present study has documented a substantial level of hazardous and harmful alcohol consumption among older adults, most of which goes undetected clinically due to the failure to consider individual health status in assessing risk. Research is needed to substantiate or refine the present estimates and to evaluate the efficacy and effectiveness of interventions such as the ARPS screening and education system or other approaches.

Evidence, based on the use of a modified ARPS system, suggests that providing information on recommended drinking limits to older adults may be enough to cause large reductions in both at-risk drinking and amount of alcohol use,32 and similar results were found in the Santa Monica trial of the ARPS system.10

There are many reasons why physicians do not screen their older patients for alcohol misuse or, if they do, why they rely primarily on self-reported alcohol consumption. Alcohol-related problems can appear to be caused by other medical problems, and most screening measures focus on abuse and dependence and were not specifically developed for the elderly. Further, physicians lack training for appropriate inquiry, and there are obvious limitations on physician time to evaluate and counsel patients, especially those with many other health issues to attend to, as well as limitations on options for referral for further counseling, when that is indicated.33,34 Online systems like the ARPS are efficient because screening can be done without physician assistance and the resulting immediate feedback can be used as a basis for deciding if follow-up is appropriate.

Electronic supplementary material

(PDF 252 kb)

Acknowledgments

Contributors

The authors gratefully acknowledge the insight and contributions of John C. Beck, MD, David Geffen School of Medicine, UCLA, Emeritus, and the Langley Research Institute; and Philip W. Lavori, PhD, Department of Health Policy and Research, Stanford University School of Medicine, in their review of draft of this manuscript.

Funders

This work was supported by the Palo Alto Medical Foundation Research Institute and the Langley Research Institute.

Prior Presentations

Results from this paper were presented at the 2012 National Conference for Health Statistics in Washington, D.C. (SRW), the 2012 meeting of the Australasian Professional Society on Alcohol and Drugs (APSAD) (AF), and at the 2013 annual conference of the HMO Research Network in April, 2013 (SK).

Conflict of Interest

Sandra R. Wilson, PhD had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Authors Sandra R. Wilson, PhD; Sarah B. Knowles, PhD; and Qiwen Huang, MS report no conflicts of interest. The ARPS is copyrighted by Arlene Fink Associates, Inc. (AFA), 2012, but, with permission, is available for research use at no cost. AFA has received licensing fees from the use of the ARPS by non-profit entities in the U.S., Australia and France.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anderson G. Chronic Care: Making the Case for Ongoing Care. Princeton: Robert Wood Johnson Foundation; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mukamal KJ, Chen CM, Rao SR, Breslow RA. Alcohol consumption and cardiovascular mortality among U.S. adults, 1987 to 2002. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:1328–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.10.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mukamal KJ, Kuller LH, Fitzpatrick AL, Longstreth WT, Jr, Mittleman MA, Siscovick DS. Prospective study of alcohol consumption and risk of dementia in older adults. JAMA. 2003;289:1405–13. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.11.1405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chermack ST, Blow FC, Hill EM, Mudd SA. The relationship between alcohol symptoms and consumption among older drinkers. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1996;20:1153–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1996.tb01104.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moos RH, Brennan PL, Schutte KK, Moos BS. Older adults’ health and changes in late-life drinking patterns. Aging Ment Health. 2005;9:49–59. doi: 10.1080/13607860412331323818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moore AA, Whiteman EJ, Ward KT. Risks of combined alcohol/medication use in older adults. Am J Geriatr Phamacother. 2007;5:64–74. doi: 10.1016/j.amjopharm.2007.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Adams WL. Potential for adverse drug-alcohol interactions among retirement community residents. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1995;43:1021–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1995.tb05567.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Special populations and co-occurring disorders: older adults. [cited 2012 May 29]; Available from: http://www.niaaa.nih.gov/alcohol-health/special-populations-co-occurring-disorders/older-adults.

- 9.Helping patients who drink too much: A clinician’s guide. Bethesda: National Institutes of Health, US Department of Health and Human Services; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fink A, Elliott MN, Tsai M, Beck JC. An evaluation of an intervention to assist primary care physicians in screening and educating older patients who use alcohol. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:1937–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.00476.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fink A, Morton SC, Beck JC, Hays RD, Spritzer K, Oishi S, et al. The alcohol-related problems survey: identifying hazardous and harmful drinking in older primary care patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50:1717–22. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50467.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Adams WL, Yuan Z, Barboriak JJ, Rimm AA. Alcohol-related hospitalizations of elderly people. Prevalence and geographic variation in the United States. JAMA. 1993;270:1222–5. doi: 10.1001/jama.1993.03510100072035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tobias CR, Lippmann S, Pary R, Oropilla T, Embry CK. Alcoholism in the elderly. How to spot and treat a problem the patient wants to hide. Postgrad Med. 1989;86(67–70):5–9. doi: 10.1080/00325481.1989.11704411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dufour M, Fuller R. Alcohol in the elderly. Ann Rev Med. 1995;46:123–32. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.46.1.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blow FC, Barry KL. Alcohol and substance misuse in older adults. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2012;14:310–9. doi: 10.1007/s11920-012-0292-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Blow FC, Barry KL. Use and misuse of alcohol among older women. Alcohol Res Health. 2002;26:308–15. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Armstrong GL, Wasley A, Simard EP, McQuillan GM, Kuhnert WL, Alter MJ. The prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection in the United States, 1999 through 2002. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144:705–14. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-144-10-200605160-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Perz JF, Armstrong GL, Farrington LA, Hutin YJ, Bell BP. The contributions of hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus infections to cirrhosis and primary liver cancer worldwide. J Hepatol. 2006;45:529–38. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2006.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, Cushman WC, Green LA, Izzo JL, Jr, et al. Seventh report of the Joint National Committee on prevention, detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure. Hypertension. 2003;42:1206–52. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000107251.49515.c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.National Center for Health Statistics. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Hyattsville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2012 [cited 2010]; Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes.htm.

- 21.National Center for Health Statistics. Analytic and Reporting Guidelines: The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). In: US Department of Health and Human Services, editor. Hyattsville, MD: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2006.

- 22.Moore AA, Beck JC, Babor TF, Hays RD, Reuben DB. Beyond alcoholism: identifying older, at-risk drinkers in primary care. J Stud Alcohol. 2002;63:316–24. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2002.63.316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moore AA, Hays RD, Reuben DB, Beck JC. Using a criterion standard to validate the Alcohol-Related Problems Survey (ARPS): a screening measure to identify harmful and hazardous drinking in older persons. Aging (Milano) 2000;12:221–7. doi: 10.1007/BF03339839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fink A, Tsai MC, Hays RD, Moore AA, Morton SC, Spritzer K, et al. Comparing the alcohol-related problems survey (ARPS) to traditional alcohol screening measures in elderly outpatients. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2002;34:55–78. doi: 10.1016/S0167-4943(01)00198-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wilson SR, Fink A, Verghese S, Beck JC, Nguyen K, Lavori P. Adding an alcohol-related risk score to an existing categorical risk classification for older adults: sensitivity to group differences. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55:445–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01072.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moore AA, Morton SC, Beck JC, Hays RD, Oishi SM, Partridge JM, et al. A new paradigm for alcohol use in older persons. Med Care. 1999;37:165–79. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199902000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kranzler HR, Tennen H, Babor TF, Kadden RM, Rounsaville BJ. Validity of the longitudinal, expert, all data procedure for psychiatric diagnosis in patients with psychoactive substance use disorders. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1997;45:93–104. doi: 10.1016/S0376-8716(97)01349-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Saunders JB, Aasland OG. World Health Organization collaborative project on the identification and treatment of persons with harmful alcohol consumption: report on Phase I development of a screening instrument. Geneva, Switzerland, 1987.

- 29.Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor TF, de la Fuente JR, Grant M. Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): WHO Collaborative Project on Early Detection of Persons with Harmful Alcohol Consumption–II. Addiction. 1993;88:791–804. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.National Center for Health Statistics. Analytic Note Regarding 2007–2010 Survey Design Changes and Combining Data Across other Survey Cycles. In: US Department of Health and Human Services, editor. Hyattsville, MD: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2010.

- 31.D'Amico EJ, Paddock SM, Burnam A, Kung FY. Identification of and guidance for problem drinking by general medical providers: results from a national survey. Med Care. 2005;43:229–36. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200503000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moore AA, Blow FC, Hoffing M, Welgreen S, Davis JW, Lin JC, et al. Primary care-based intervention to reduce at-risk drinking in older adults: a randomized controlled trial. Addiction. 2011;106:111–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03229.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Friedmann PD, McCullough D, Chin MH, Saitz R. Screening and intervention for alcohol problems. A national survey of primary care physicians and psychiatrists. J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15:84–91. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2000.03379.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kuehn BM. Despite benefit, physicians slow to offer brief advice on harmful alcohol use. JAMA. 2008;299(7):751–3. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.7.751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(PDF 252 kb)