Abstract

Asymptomatic bacteriuria (ASB) is a condition in which bacteria are present in a noncontaminated urine sample collected from a patient without signs or symptoms related to the urinary tract. ASB must be distinguished from symptomatic UTI by the absence of signs and symptoms compatible with UTI or by clinical determination that a nonurinary etiology accounts for the patient's symptoms. ABU is a very common condition that is often treated unnecessarily with antibiotics. Pregnant women and persons undergoing urologic procedures expected to cause mucosal bleeding are the only two groups with convincing evidence that screening for and treating ASB is beneficial. Randomized, controlled trials of ASB screening and/or treatment have established the lack of efficacy in premenopausal adult women, diabetic women, patients with spinal cord injury, catheterized patients, older adults living in the community, and elderly institutionalized adults. The overall purpose of this review is to promote an awareness of ASB as a distinct condition from UTI and to empower clinicians to withhold antibiotics in situations in which antimicrobial treatment of bacteriuria is not indicated.

Keywords: Asymptomatic bacteriuria, urinary tract infection, anti-bacterial agents, guidelines implementation

Introduction

Definition of ASB

In most patient populations, interpretation of a positive urine culture depends upon the presence or absence of associated symptoms. The definitions that we will use in this review are those of the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) guidelines concerning ASB (2005) and catheter-associated urinary tract infection, or CAUTI (2010).1-2 In a patient without signs and symptoms of urinary origin, the presence of bacteria in a non-contaminated urine specimen is defined as asymptomatic bacteriuria (ASB). 3 In contrast, urinary tract infection (UTI) requires the presence of urinary-specific symptoms or signs in a patient who has both bacteriuria and no other identified source of infection.1,4 The definition of ASB requires isolation of the same organism in two consecutive voided urine specimens for women, one voided urine specimen for men, and, in addition, from a single urine specimen collected via urinary catheter in both sexes.2 Neither the type of bacterial species isolated from the urine nor presence of pyuria can be used to determine whether the patient has ASB or UTI. Available evidence supports screening for and treatment of ASB in pregnant women and in patients undergoing invasive urologic procedures.3 In most other patient groups, there is convincing evidence that neither screening nor treatment lead to improved clinical outcomes.3 Unnecessary antibiotics given to treat ASB can cause harm in terms of antibiotic resistance, adverse drug effects, and wasted expense.5

These definitions are hard to apply in clinical settings, particularly in the patient populations in which ASB is most common—catheterized patients, nursing home patients, and patients in intensive care units. The lack of specific diagnostic tests to distinguish UTI from ASB means that the diagnosis of ASB entirely on clinical assessment of the patient's symptoms or lack thereof. Many hospitalized or institutionalized patients may be unable to express their symptoms, and non-urinary symptoms are often attributed to bacteriuria in such patients.6-8 Another challenge is that the diagnosis of ASB requires that the clinician ignore powerful stimuli for the use of antimicrobial agents, namely a positive urine culture result and pyuria. Other incorrect mental cues, such as reliance on urine color or urine odor, may also lead to misdiagnosis.9 Human microbiome studies are disproving the dictum that normal bladders are sterile,10 but the conviction that untreated bacteriuria will lead to harm persists.11

This review will focus on the epidemiology of ASB and its clinical significance. The review will cover appropriate management of ASB in various patient populations, delineating where evidence is not adequate to support recommendations and discussing what evidence is able to guide the clinician in these areas of uncertainty. We will also summarize the growing body of published interventions that have been employed to prevent overtreatment of ASB. We will not address ASB in children, as the pathogenesis differs from that of ASB in the adult.12 Furthermore, this review does not discuss symptomatic UTI or acute cystitis, which requires treatment with antibiotics to relieve symptoms13 and can lead to pyelonephritis when untreated.14 Asymptomatic funguria, management of ASB in patients undergoing urologic surgery, and management of ASB in renal transplant patients will be addressed in other chapters in this issue. The overall purpose of this review is to promote an awareness of ASB as a distinct condition and to empower clinicians to withhold antibiotics in situations in which antimicrobial treatment of bacteriuria is not indicated.

Epidemiology and Significance of ASB

ASB is very common

In 2008 the Centers for Disease Control published new surveillance definitions for CAUTI to be used by the National Healthcare Safety Network (NHSN), the United States' most widely used healthcare-associated infection (HAI) tracking system. In keeping with the increased awareness of the distinction between UTI and ASB, ASB was excluded from urologic conditions to detect and report, in contrast to earlier definitions.15 Presumably, the decision to exclude ASB was based on the growing awareness that ASB is not a clinically relevant condition in most populations. Changing the definition, however, was not accompanied by any change in the proportion of positive urine cultures treated with antibiotics in a large, academic medical center; such change is unlikely without an active intervention.16 Unfortunately, the current lack of standards for detecting and reporting ASB means that published epidemiology of this condition in the United States is based on data collected prior to 200817-18 or is from smaller studies.19-20 Prior to this definition change, a point prevalence study in Veterans Affairs nursing homes in 2007 found that ASB accounted for 10% of all nursing home acquired infections, second only to UTI and skin infections.17 National surveillance data from 1990 through 2007 showed a significant decline in ASB rates in all ICU types.18 Estimated declines in ASB incidence ranged from 28.5% (95% CI, 20.1%-35.9%; medical/surgical without a major teaching affiliation) to 71.8% (95% CI 68.0%-75.2%; medical/surgical with a major teaching affiliation). These declines suggest that CAUTI prevention efforts in some ICUs may reduce ASB as well as CAUTI.

Risk factors for asymptomatic bacteriuria include older age, female sex, and abnormalities of the genitourinary tract (Box 1). For example, the prevalence of ASB in healthy young women is 1-5%, while women older than 70 years living in the community have a risk > 15%.21 Genetic factors may predispose certain women to ASB.22 In men, a higher post void residual is associated with asymptomatic bacteriuria, and older men are at higher risk for prostatic enlargement, which in turn creates a higher post void residual.23 Whether diabetes itself creates a predisposition to ASB is not entirely clear. A single center study in 511 diabetic and 97 non-diabetic subjects (97) found a similar incidence of ASB in both groups.24 However, a meta-analysis of 22 studies of ASB in diabetic versus non-diabetic subjects brought more depth to this topic. The point prevalence of ASB was higher in both women (14.2 vs. 5.1%; 2.6[1.6–4.1]) and men (2.3 vs. 0.8%; 3.7[1.3–10.2]) with diabetes than in healthy control subjects.25

Box 1. Risk Factors for bacteriuria in general21.

| Sexual activity* |

| Use of diaphragm with spermicide* |

| Older age |

| Female sex |

| Diabetes mellitus |

| Neurogenic bladder |

| Hemodialysis |

| Urinary retention |

| Urinary catheter use |

| Indwelling |

| Intermittent |

| External (condom) |

| *In sexually active, non-pregnant women ages 18-40.29 |

In patients with indwelling urinary catheters, the most important risk factor for bacteriuria is the duration of catheterization.26 Antimicrobial agents decrease the risk of bacteriuria for initial 4 days of catheterization but are not of benefit and predispose to resistant organisms in patients catheterized longer than 4 days.27 Since NHSN surveillance for CAUTI by definition includes only patients with indwelling catheters (Foley catheters), the risk of bacteriuria with other catheter types is not well-documented. A study in 7,866 inpatients on acute medicine and nursing home units over the course of one year documented 1,009 catheter-associated, positive urine cultures. Of these, 376 (37.3%) were from external (condom) catheters, and more of the urine cultures collected from condom catheters were positive than those collected from indwelling catheters (77.1% versus 55%, respectively, P<0.001).28 Strategies to reduce CAUTI by substituting external catheters for indwelling catheters could inadvertently lead to increased antimicrobial overuse for ASB if the risk of bacteriuria with condom catheters proves to be a general phenomenon.

Clinical outcomes associated with ASB

Studies of the clinical impact of ASB are often confounded by the differences between persons who do and who do not have ASB at baseline. For example, 490 generally healthy women were included in a prospective study to assess the association between bacteriuria and renal function; of these, 48 had E. coli bacteriuria at baseline. Over a mean of 12 years of follow-up, no association was found between E. coli bacteriuria and a decline in renal function.30 A subsequent analysis in generally the same cohort found that E. coli bacteriuria at baseline was associated with development of hypertension, but even at baseline, the E. coli bacteriuria group had a higher incidence of hypertension.31

Application of modern molecular typing techniques to samples from a prior trial of treatment versus non-treatment of ASB in diabetic women32 offers insight on why treatment of ASB is ineffective and even potentially harmful in this population.33 Women with diabetes and E. coli bacteriuria were randomized to treatment for ASB (every 3 months) or no treatment. Among the 57 women in the treatment group, 76% treatment regimens were followed by recurrent E. coli bacteriuria, most of which(64%) involved a new strain of E. coli. Women in the treatment group received an average of 3 courses of antimicrobial therapy, but some were treated up to 15 times. Antimicrobial treatment did not prevent recurrence but instead resulted in strain change over. A similar phenomenon was reported in a prospective study of 330 community dwelling women ≥ 80 years old, followed with serial urine cultures.34 40% of women with ASB carried the same strain of E. coli for 18 months, but antibiotic treatment led to strain turnover. Spontaneous strain turnover was also common, suggesting re-colonization. In this study, the women with ASB at baseline were more likely to have symptomatic UTI over the following 24 months than those without ASB (P=0.019), but the only confounding variable explicitly considered in analysis was age.

Overtreatment of ASB is very common

Failure to recognize ASB as a distinct condition from UTI has negative clinical consequences, namely overuse of antibiotics. These consequences include “collateral damage” or ecological adverse effects of antibiotic use, as well as the risks of cumulative antibiotic exposure to the individual patient.5,35-36 In 2013 the American Board of Internal Medicine identified treatment of ASB as one of the top 5 excessive healthcare practices in the field of geriatrics in its “Choosing Wisely” campaign.37 The CDC “Get Smart: Know When Antibiotics Work” campaign promotes conservative use of antibiotics, including using antibiotics to treat infection but not colonization; ASB in this context would be considered bladder colonization.38 The cumulative impact of antimicrobial overuse on the antimicrobial susceptibility of human pathogens impairs the effectiveness of current and future antimicrobial agents.39 In a two-year Swedish community study, restriction of trimethoprim-containing drugs did not lead to any change in the trimethoprim resistance rate in E. coli, thus raising the ominous concern that antimicrobial resistance may be irreversible.40

Unfortunately, mismanagement of ABU—or inappropriate treatment with antibiotics—is an epidemic condition.41 Multiple studies from the United States and Canada have evaluated how often patients with ASB receive antimicrobial agents for suspected UTI (Table 1). All have found substantial rates of overtreatment, ranging from 20% in an emergency room study42 to 83% in a nursing home setting.43 A number of these studies reported high rates of overtreatment in catheterized patients, illustrating how difficult it is to interpret a positive urine culture in this population. Another concern is that many of the days of antimicrobial therapy given for ASB are unnecessary. In one study in catheterized inpatients, 201 (69%) of 293 days of antibiotic therapy to treat the urine were unnecessary.44 A three-year retrospective study of patients with vancomycin-resistant enterococci in their urine documented that over 200 days of antimicrobial therapy were not indicated, resulting in $50,000 in unnecessary antimicrobial costs.45

Table 1. Studies documenting widespread inappropriate use of antibiotics for ASB.

| Reference | Country | Study design | Study population | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hecker et al.89 (2003) | USA | Prospective, observation over 14 days | 129 inpatients | 99 of 576 (17%) unnecessary days of antibiotics were for ABU |

| Dalen et al.90 (2005) | Canada | Prospective, observation over 26 days | 29 inpatients with urinary catheters, positive urine cultures and no symptoms of UTI | 15 (52%) were prescribed unnecessary antimicrobials |

| Cope et al.19 (2009) | USA | Retrospective review over 3 months | 197 inpatients with urinary catheters and positive urine cultures | Of 169 treated episodes of bacteriuria 53 (31%) were ASB |

| Gandhi et al.91 (2009) | USA | Retrospective review over 3 months | 414 inpatients | Of 49 patients who were treated for UTI, 13 (26%) had ASB |

| Silver et al.6 (2009) | Canada | Prospective, observation over 1 year | 137 inpatients with positive urine cultures | 43 (64%) patients with ASB were treated |

| Khawcharoenporn et al.42 (2011) | USA | Retrospective review over 8 months | 676 emergency department patients with positive urine cultures | 37 (20%) of 184 patients with ASB were treated with antibiotics |

| Werner et al.87 (2011) | USA | Prospective, observation over 6 weeks | 226 inpatients who received fluoroquinolones | Of 690 days of unnecessary fluoroquinolone therapy, 158 (23%) were for ABU |

| Lin et al. (2012)20 | USA | Retrospective review over 3 months | 339 inpatients, outpatients and emergency department patients with enterococcal bacteriuria | 60 (32.8%) of 183 episodes of ASB inappropriately treated with antibiotics |

| Philips et al (2012)43 | USA | Retrospective review over 6 months | 16 catheterized nursing home patients | 19 (83%) of 23 treated episodes were asymptomatic |

| Chiu et al. (2013)44 | Canada | Retrospective review over 6 months. | 80 inpatients with indwelling urinary catheters | 23 (58%) of 40 patients with a positive culture result were prescribed unnecessary antimicrobials |

| D'Agata et al.(2013)61 | USA | Prospective over 12 months | 72 nursing home residents with dementia | 82 (75%) of 110 episodes of suspected UTI were prescribed unnecessary antibiotics |

| Heintz et al(2013)45 | USA | Retrospective review over 3 years | 252 patients with vancomycin-resistant enterococci in urine | 33 (21.3%) of 155 asymptomatic patients were treated |

Abbreviations: ASB asymptomatic bacteriuria. USA: United States of America

Management of ASB

Patient groups with ASB who should be routinely be treated

Current guidelines recommend ASB screening and treatment in pregnant women and patients undergoing selected urologic procedures.2,46 A recent meta-analysis comparing antibiotics versus no treatment for pregnant women with ASB found that the treatment substantially reduced the risk of pyelonephritis.47 The relationship between ASB, low birth weight and preterm delivery is less well established.48 In a Cochrane review, antibiotic treatment was associated with a reduction in the incidence of low birth weight but not with preterm delivery.47 However, poor methodological quality of studies included limits the strength of conclusions from this meta-analysis. Moreover, the definition of prematurity has changed since the 1960s, when the majority of these studies were conducted. Three more recent observational studies reported an increased risk of preterm birth with ASB in pregnancy.49-51 An ongoing Dutch trial is evaluating whether nitrofurantoin treatment of low-risk, pregnant women with ASB is effective in reducing the risk of preterm delivery and/or pyelonephritis and adverse neonatal outcome.52

There is no consensus in the literature on screening frequency, the duration of therapy or the choice of antibiotic for ASB in pregnancy.48 A Cochrane Review of different antibiotic regimens to treat ASB in pregnancy found five comparative trials, four of which tested currently used antimicrobial agents: fosfomycin, cefuroxime, pivmecillinam, ampicillin, cephalexin, and nitrofurantoin.53 Each trial examined a different antibiotic regimen, so no conclusions can be drawn about the most effective antibiotic regimen for ASB of pregnancy. However, in the most recent and largest of these five studies a 7-day course of nitrofurantoin was shown to be more effective at achieving bacteriologic cure at 14 days post-treatment than a 1-day course of nitrofurantoin.54 In another Cochrane review on the treatment duration for ASB, the cure rate was higher for the four-to seven-day treatment than for the one-day treatment.55

Patient groups with ASB who should not be treated

Non-pregnant women

Diabetic women

Elderly persons living in the community

Persons with spinal cord injury

Catheterized patients while the catheter remains in place

Several prospective studies had established that ASB in premenopausal, non-pregnant women is not associated with long-term adverse outcomes and treatment of ASB neither decreases the frequency of symptomatic infection nor prevents further episodes of ASB.2 More recently, a randomized, non-placebo controlled trial studied ASB specifically in women with recurrent UTI. This study enrolled 673 women ages 18-40 with recurrent UTI and ASB at baseline.56 Women were split into two groups, treated with a single course of antibiotics or not treated, and followed for 12 months. At the last follow-up, 41 (13.1%) in the untreated group and 169 (46.8%) in the treated group had a symptomatic UTI (RR, 3.17; 95% CI, 2.55–3.90; P < .0001). This finding is in line with a prior observational cohort study that reported women who had received antimicrobials during the previous 15-28 days were at higher risk for UTI.57 A plausible explanation is that antibiotics may predispose to UTI by altering the flora colonizing the vagina.

Randomized, controlled trials of ASB screening and/or treatment have established the lack of efficacy in diabetic women, patients with spinal cord injury, catheterized patients, and older adults.2 In randomized, controlled trials including patients with spinal cord injury, rates of symptomatic urinary infection and recurrence of bacteriuria were similar in patients receiving antibiotics and those who did not.58-59 Antibiotic treatment in catheterized patients did not decrease symptomatic episodes and increased emergence of more resistant organisms.2

Patient groups in which ASB is particularly hard to diagnose

Nursing home patients

Clinical trials in elderly nursing home residents have consistently found no benefits with treatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria.46 The minimum clinical criteria to initiate antimicrobial therapy in the general nursing home population were established in 2001.60 Despite extensive research demonstrating a lack of benefit and a potential for harm for antibiotic use for ASB, nursing home residents frequently receive an antibiotic for ASB. In a recent study investigating antibiotic use among residents in four nursing homes, half of the antibiotic prescriptions were for residents with no documented UTI symptoms.43 In another study, only 11% of suspected UTI episodes in nursing home residents with advanced dementia had both the symptoms and laboratory criteria necessary for diagnosis of UTI; 82 (75%) of the 110 episodes that did not meet the minimum criteria for treatment were treated with antimicrobials.61 The usefulness of urinary specimens in diagnosing UTI was questionable, because the proportion of episodes with a positive urinalysis and culture was similar for those that met (83%) and did not meet (78%) minimum clinical criteria (P=0.06).61

Intensive Care Unit (ICU) patients

ICU patients and older institutionalized patients have in common a limited ability to communicate. Most patients who are hospitalized in ICUs receive an indwelling urinary catheter to monitor urine output; many are also on ventilators and have centrally-placed vascular catheters. Thus, determining the source of fever in an ICU patient with an indwelling catheter is particularly difficult, particularly as catheter-associated bacteriuria is so common. A study in a French ICU of two different urinary catheter types found that 9.6% of patients developed bacteriuria on day 12 ± 7, although these study catheters had been placed under ideal conditions.62 In a trauma ICU study in 510 patients, the tendency to blame fever on bacteriuria was not supported by evidence. Although there was a significant association between having a urine culture and having a fever (P<0.001), bacteriuria was not associated with fever, leukocytosis, or the combination of fever and leukocytosis.63 A systematic review and meta-analysis of 11 studies in adult ICU patients with catheter-associated bacteriuria (with or without symptoms of CAUTI) found that bacteriuria was associated with increased mortality in unadjusted analysis. However, after restricting the analysis to studies that adjusted for other outcome predictors, bacteriuria was no longer associated with mortality but was possibly related to a small increase in length of stay (mean difference +2.6 days; 95% CI 2.3-3.0).64 This finding is in accord with the results of a randomized clinical trial in 60 patients on ICUs who were asymptomatic and catheterized with positive urine cultures.65 Treatment of the bacteriuria with antibiotics and catheter exchange did not reduce the rate of urosepsis, bacteremia, or positive urine cultures on day 15 after enrolment.

Patient groups with ASB and inadequate evidence to guide management

Evidence to guide management of preoperative ASB before nonurologic procedures is limited. A recent study addressed whether preoperative screening for and treatment of ASB in patients undergoing cardiovascular, orthopedic, or vascular procedures confers benefits.66 Among patients with a preoperative culture, patients with bacteriuria and those without bacteriuria were compared for postoperative complications. Surgical site infection was similarly frequent among patients with bacteriuria versus those without, while postoperative UTI was more frequent among patients with bacteriuria (9% vs. 2%, P=0.01). Among the 54 patients with a positive screening culture, a greater proportion of treated patients developed a surgical site infection compared to untreated patients (45% vs. 14%, P=0.03 P). However, the findings from this small observational study should be interpreted with caution because of the high likelihood of confounding factors.

Few studies have evaluated the impact of bacteriuria in patients undergoing major joint replacement surgery.67 The majority of these studies had retrospective design and were published over a decade ago.67 In one prospective study of hip and knee arthroplasty, preoperative bacteriuria was not associated with subsequent joint infection at one year after the procedure.68 However, all patients in this study had received preoperative cefuroxime therapy. In a recent prospective randomized study including 471 patients, ASB occurred in 8 (3.5%) of 228 patients undergoing total hip arthroplasty and in 38 (15.6%) of 243 patients undergoing hemiarthroplasty.69 Patients were randomized to receive specific antibiotic treatment or no treatment. No case of prosthetic joint infection from urinary origin was identified in any study group in this trial. However, the sample size might have been too small to detect an effect in this trial. Whether screening for and treating bacteriuria prior to prosthetic joint implantation confers any clinical benefit is unknown.

Another area lacking definitive evidence in the IDSA guidelines how to manage existing bacteriuria at the time of removal of a urinary catheter. Since publication of the guidelines, additional literature on this topic provided enough data to perform a meta-analysis.70-72 In a systematic review and meta-analysis of pooled data from seven studies, antibiotic prophylaxis was beneficial with an absolute reduction in risk symptomatic UTI of 5.8% between intervention and control groups and a risk ratio of 0.45 (95% 0.28 to 0.72).73 One obvious practical consideration is that to implement this approach, testing of urine prior to catheter removal would need to be performed in time to have urine culture results at catheter removal or shortly thereafter.

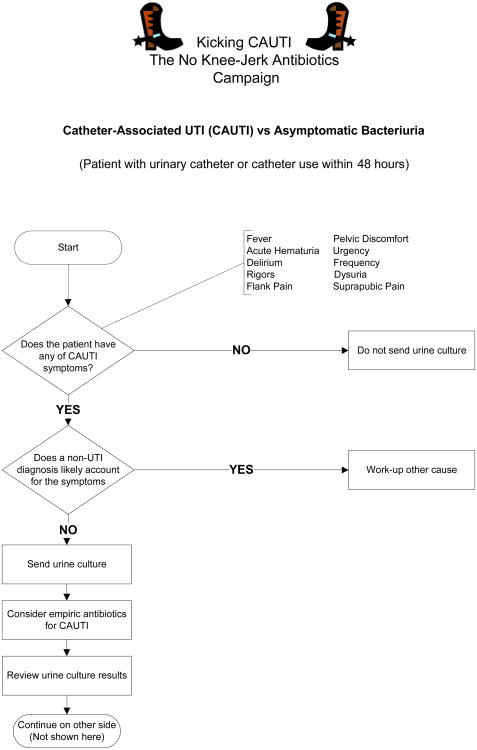

Prevention of inappropriate treatment of ASB

Several interventional studies have addressed the issue of inappropriate treatment of ASB (Table 2). 74-80 These guidelines implementation interventions were heterogeneous and measured different outcomes. However, all strategies went beyond passive education, many incorporating audit and feedback or interactive learning, and all reported a decrease in antibiotic use. One common theme of these diverse and successful strategies is that they engendered medical mindfulness, or making a thoughtful clinical decision, rather than reflexive use of antibiotics.81-82 Our ongoing intervention, entitled “Kicking CAUTI: the No Knee-Jerk Antibiotics Campaign,” encourages clinicians to stop and think before ordering cultures and prescribing antibiotics for catheter-associated bacteriuria.83 The two main tools used in the intervention are (1) an evidence based, actionable algorithm that distills the guidelines into a streamlined clinical pathway and encourages a mindful pause (Figure 1),9 and (2) case-based audit and feedback to train clinicians to use the algorithm. This algorithm was developed with input from the authors of the IDSA ASB and CAUTI guidelines, and use of this algorithm improved non-experts diagnostic accuracy of ASB versus CAUTI when applied retrospectively to actual cases.9 Overall, these interventional studies offer hope that guidelines implementation can decrease antimicrobial overuse for ASB. The design of interventions to reduce overutilization for ASB should integrate behavioral theory so that the underlying cognitive, behavioral, and financial drivers are addressed.84 Interventions should to be tailored to fit specific goals and also need to address the root causes of inappropriate prescribing.85

Table 2. Interventional Studies to Decrease ASB Overtreatment.

| Reference | Study setting | Study design | Intervention | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Loeb et al.74 (2005) | Nursing homes | Cluster randomized controlled trial | Multifaceted, algorithm use taught by case scenarios in interactive sessions | Fewer courses of antimicrobials for suspected UTI in intervention homes (1.17/1000 resident days) than in control homes (1.59/1000 resident days) |

| Bonnal et al.75 (2008) | University-affiliated geriatric hospital | Audit before and after intervention | Pocket card plus post-prescription audit and feedback for positive urine cultures managed inappropriately | Antibiotic use for ASB decreased from 196 days during the pre-intervention year to 150 days during the intervention year, P = 0.007 |

| Zabarsky et al.78 (2008) | Veterans Affairs long-term care facility | Audit before and after intervention | Pocket cards, educational sessions, audit and feedback | Decrease in urine cultures sent, reduction in treatment of ASB and in total days of antimicrobial therapy (from 168 to 117 per 1000 patient-days, P <0.001) |

| Pavese et al.79 (2009) | University-affiliated hospital | Controlled audit before and after intervention | Distribution of guidelines and report plus a 1 hour interactive educational session | Antibiotic use for ASB in intervention group decreased from 74% before intervention to 17% afterwards (P = 0.01) |

| Linares et al.80 (2011) | Veterans Affairs hospital | Audit before and after intervention | Memorandum placed in electronic medical record if antibiotics were inappropriate | Mean duration of treatment of ASB decreased from 6.3 days in control group to 2.2 days in intervention group (P <0.001) |

| Egger et al (2013)76 | Teaching hospital | Before and after | Multifaceted, implementation of guidelines, catheter reminders, and internet-based teaching cases | ASB treatment dropped significantly from 22 to 10 treatment days per 1,000 patient days (incidence rate ratio 0.46, 95%CI 0.33-0.63) |

| Pettersson et al (2011)77 | Nursing homes | Cluster randomized controlled trial | Education about UTI with feedback on baseline antibiotic prescription data | The proportion of overall infections treated with an antibiotic decreased significantly by -0.124 (95%CI -0.228, -0.019) compared with the control group |

Abbreviations: ASB, asymptomatic bacteriuria; UTI, urinary tract infection

Figure 1.

Validated algorithm to assist in clinical decision making about positive urine cultures in cahteterized patients. The focus of the algorithm is on reminding the clinician to stop and think about two key questions before reflexively prescribing antibiotics for bacteriuruia. Reprinted here with permission from BioMed Central.9

Summary

The most important and far-reaching consequences of ASB are not the impact of this condition per se on the individual patient but the negative consequences of overtreatment of ASB in terms of antimicrobial resistance, suprainfections, and unnecessary costs. Increasing awareness that ASB usually does not require treatment led to eliminating ASB from infection control surveillance programs, but this change in surveillance definitions will not in itself change clinical practice.86 Likewise, although the epidemic of overtreatment of ASB has been thoroughly documented, these descriptions in themselves will not lead to a solution unless their data serve as a foundation for interventions to optimize management of ASB. Unfortunately, awareness that overtreatment of ASB is a problem has preceded any immediate widespread solutions; currently many of the episodes diagnosed and treated as CAUTI in the hospital are really ASB.20,44,87 In the future, perhaps some of the resources that have been channeled into reducing CAUTI and other healthcare-associated infections88 can be used to support effective ASB guidelines implementation programs.

Review criteria

We developed a search strategy that covers the main subject area of the review (asymptomatic bacteriuria) and performed systematic literature search in the Medline database. The search was limited to articles published in English between 2002-2013. We searched initially using the following search strategy: “Asymptomatic bacteriuria AND (Anti-bacterial agents OR antimicrobial OR antimicrobials OR anti-microbial OR anti-microbials OR antibiotic OR antibiotics OR anti-bacterial OR antibacterial OR antibacterials).”

We used the following abstract appraisal criteria:

Title or abstract addresses one or more of the study questions

Title or abstract identifies primary research or systematically conducted secondary research

We also searched reference lists of retrieved articles (particularly older literature) and hand searched abstracts from key journals. We used additional search strategies for each subtopic, including the following search terms “catheter-associated urinary tract infection,” “bacteriuria and diabetes,” “bacteriuria and non-pregnant,” “bacteriuria and spinal cord injury,” “bacteriuria and intensive care OR ICU OR critically ill,” “bacteriuria in elderly,” “bacteriuria and nursing home,” “antibiotic overuse,” “performance measures,” “Escherichia coli and bacteriuria,” “bacteriuria and pregnancy,” “bacteriuria and preoperative,” “bacteriuria and urinary catheter removal,” “Escherichia coli,” and “bacteriuria and anti-bacterial agents,” among others.

Key points.

Asymptomatic bacteriuria (ASB) is defined by the presence of bacteria in an uncontaminated urine sample collected from a patient without signs or symptoms referable to the urinary tract.

ASB is distinguished from symptomatic UTI by the absence of signs and symptoms of UTI or by determination that a nonurinary etiology accounts for the patient's symptoms.

ABU is a very common condition in diverse patient groups.

Overtreatment of ASB with antibiotics is also very common, particularly in patients who are hospitalized, have urinary catheters, or live in a nursing home setting.

Unnecessary antimicrobial treatment of ASB confers harm to the individual and to society.

Acknowledgments

Disclosure Statement: This work was supported by grants from the Department of Veterans Affairs [VA RR&D VA HSR&D IIR 09-104 and QUERI RRP 12-443] and the National Institutes of Health [NIH DK092293] to BW Trautner. This manuscript is the result of work supported with resources and use of facilities at the Houston VA Health Services Research and Development Center of Excellence [HFP90-020] at the Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center, Houston, TX. The opinions expressed reflect those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Department of Veterans Affairs, the US government, the NIH or Baylor College of Medicine.

L. Grigoryan's research activities were supported by National Research Service Award # 5 T32 HP10031.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Hooton TM, et al. Diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of catheter-associated urinary tract infection in adults: 2009 International Clinical Practice Guidelines from the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50:625–663. doi: 10.1086/650482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nicolle LE, et al. Infectious Diseases Society of America guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria in adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;40:643–654. doi: 10.1086/427507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lin K, Fajardo K. Screening for asymptomatic bacteriuria in adults: evidence for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force reaffirmation recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149:W20–24. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-149-1-200807010-00009-w1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Horan T, Andrus M, Dudeck M. CDC/NHSN surveillance definition of healthcare-associated infection and criteria for specific types of infections in the acute care setting. 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gupta K, et al. International clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of acute uncomplicated cystitis and pyelonephritis in women: A 2010 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the European Society for Microbiology and Infectious Diseases. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52:e103–120. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciq257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Silver SA, Baillie L, Simor AE. Positive urine cultures: A major cause of inappropriate antimicrobial use in hospitals? Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol. 2009;20:107–111. doi: 10.1155/2009/702545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Walker S, McGeer A, Simor AE, Armstrong-Evans M, Loeb M. Why are antibiotics prescribed for asymptomatic bacteriuria in institutionalized elderly people? A qualitative study of physicians' and nurses' perceptions. CMAJ. 2000;163:273–277. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Drinka PJ, Crnich CJ. Diagnostic accuracy of criteria for urinary tract infection in a cohort of nursing home residents. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56:76–377. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01533.x. author reply 378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Trautner BW, et al. Development and validation of an algorithm to recalibrate mental models and reduce diagnostic errors associated with catheter-associated bacteriuria. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2013;13:48. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-13-48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fouts DE, et al. Integrated next-generation sequencing of 16S rDNA and metaproteomics differentiate the healthy urine microbiome from asymptomatic bacteriuria in neuropathic bladder associated with spinal cord injury. Journal of translational medicine. 2012;10:174. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-10-174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Drekonja DM, et al. A survey of resident physicians' knowledge regarding urine testing and subsequent antimicrobial treatment. Am J Infect Control. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2013.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Montini G, Tullus K, Hewitt I. Febrile urinary tract infections in children. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:239–250. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1007755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Little P, et al. Effectiveness of five different approaches in management of urinary tract infection: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2010;340:c199. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Falagas ME, Kotsantis IK, Vouloumanou EK, Rafailidis PI. Antibiotics versus placebo in the treatment of women with uncomplicated cystitis: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Infect. 2009;58:91–102. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2008.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Surveillance definition of healthcare-associated infection and criteria for specific types of infection in the acute care setting [Google Scholar]

- 16.Press MJ, Metlay JP. Catheter-associated urinary tract infection: does changing the definition change quality? Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2013;34:313–315. doi: 10.1086/669525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tsan L, et al. Nursing home-associated infections in Department of Veterans Affairs community living centers. Am J Infect Control. 2010;38:461–466. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2009.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Burton DC, Edwards JR, Srinivasan A, Fridkin SK, Gould CV. Trends in catheter-associated urinary tract infections in adult intensive care units-United States, 1990-2007. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2011;32:748–756. doi: 10.1086/660872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cope M, et al. Inappropriate treatment of catheter-associated asymptomatic bacteriuria in a tertiary care hospital. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48:1182–1188. doi: 10.1086/597403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lin E, Bhusal Y, Horwitz D, Shelburne SA, 3rd, Trautner BW. Overtreatment of enterococcal bacteriuria. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:33–38. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Colgan R, Nicolle LE, McGlone A, Hooton TM. Asymptomatic bacteriuria in adults. Am Fam Physician. 2006;74:985–990. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hawn TR, et al. Genetic variation of the human urinary tract innate immune response and asymptomatic bacteriuria in women. PLoS One. 2009;4:e8300. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Truzzi JC, Almeida FM, Nunes EC, Sadi MV. Residual urinary volume and urinary tract infection--when are they linked? The Journal of urology. 2008;180:182–185. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.03.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Matteucci E, Troilo A, Leonetti P, Giampietro O. Significant bacteriuria in outpatient diabetic and non-diabetic persons. Diabet Med. 2007;24:1455–1459. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2007.02294.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Renko M, Tapanainen P, Tossavainen P, Pokka T, Uhari M. Meta-analysis of the significance of asymptomatic bacteriuria in diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2011;34:230–235. doi: 10.2337/dc10-0421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shuman EK, Chenoweth CE. Recognition and prevention of healthcare-associated urinary tract infections in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2010;38:S373–379. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181e6ce8f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Garibaldi RA, Burke JP, Dickman ML, Smith CB. Factors predisposing to bacteriuria during indwelling urethral catheterization. N Engl J Med. 1974;291:215–219. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197408012910501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Trautner BW, et al. Quality gaps in documenting urinary catheter use and infectious outcomes. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2013;34:793–799. doi: 10.1086/671267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hooton TM, et al. A prospective study of asymptomatic bacteriuria in sexually active young women. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:992–997. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200010053431402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Meiland R, et al. Association between Escherichia coli bacteriuria and renal function in women: long-term follow-up. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:253–257. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.3.253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Meiland R, et al. Escherichia coli bacteriuria in female adults is associated with the development of hypertension. Int J Infect Dis. 2010;14:e304–307. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2009.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harding G, Zhanel G, Nicolle L, Cheang M. Antimicrobial treatment in diabetic women with asymptomatic bacteriuria. NEJM. 2002;347:1576–1583. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dalal S, et al. Long-term Escherichia coli asymptomatic bacteriuria among women with diabetes mellitus. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49:491–497. doi: 10.1086/600883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rodhe N, et al. Asymptomatic bacteriuria in the elderly: high prevalence and high turnover of strains. Scand J Infect Dis. 2008;40:804–810. doi: 10.1080/00365540802195242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Paterson DL. “Collateral damage” from cephalosporin or quinolone antibiotic therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;38(4):S341–345. doi: 10.1086/382690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stevens V, Dumyati G, Fine LS, Fisher SG, van Wijngaarden E. Cumulative Antibiotic Exposures Over Time and the Risk of Clostridium difficile Infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53:42–48. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.ABIM Foundation. Choosing Wisely: An initiative of the ABIM foundation. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Get Smart: Know When Antibiotics Work [Google Scholar]

- 39.Spellberg B, et al. The epidemic of antibiotic-resistant infections: a call to action for the medical community from the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46:155–164. doi: 10.1086/524891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sundqvist M, et al. Little evidence for reversibility of trimethoprim resistance after a drastic reduction in trimethoprim use. The Journal of antimicrobial chemotherapy. 2010;65:350–360. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkp387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gross PA, Patel B. Reducing antibiotic overuse: a call for a national performance measure for not treating asymptomatic bacteriuria. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45:1335–1337. doi: 10.1086/522183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Khawcharoenporn T, Vasoo S, Ward E, Singh K. Abnormal urinalysis finding triggered antibiotic prescription for asymptomatic bacteriuria in the ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2011.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Phillips CD, et al. Asymptomatic bacteriuria, antibiotic use, and suspected urinary tract infections in four nursing homes. BMC Geriatr. 2012;12:73. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-12-73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chiu J, et al. Antibiotic prescribing practices for catheter urine culture results. The Canadian journal of hospital pharmacy. 2013;66:13–20. doi: 10.4212/cjhp.v66i1.1207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Heintz BH, Cho S, Fujioka A, Li J, Halilovic J. Evaluation of the treatment of vancomycin-resistant enterococcal urinary tract infections in a large academic medical center. Ann Pharmacother. 2013;47:159–169. doi: 10.1345/aph.1R419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nicolle LE. Asymptomatic bacteriuria: review and discussion of the IDSA guidelines. International journal of antimicrobial agents. 2006;28(1):S42–48. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2006.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Smaill F, Vazquez JC. Antibiotics for asymptomatic bacteriuria in pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007:CD000490. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000490.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schnarr J, Smaill F. Asymptomatic bacteriuria and symptomatic urinary tract infections in pregnancy. European journal of clinical investigation. 2008;38(2):50–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2008.02009.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sheiner E, Mazor-Drey E, Levy A. Asymptomatic bacteriuria during pregnancy. The journal of maternal-fetal & neonatal medicine: the official journal of the European Association of Perinatal Medicine, the Federation of Asia and Oceania Perinatal Societies, the International Society of Perinatal Obstet. 2009;22:423–427. doi: 10.1080/14767050802360783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Marahatta R, Dhungel BA, Pradhan P, Rai SK, Choudhury DR. Asymptomatic bacteriurea among pregnant women visiting Nepal Medical College Teaching Hospital, Kathmandu, Nepal. Nepal Medical College journal: NMCJ. 2011;13:107–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ullah MA, Barman A, Siddique MA, Haque AK. Prevalence of asymptomatic bacteriuria and its consequences in pregnancy in a rural community of Bangladesh. Bangladesh Medical Research Council bulletin. 2007;33:60–64. doi: 10.3329/bmrcb.v33i2.1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kazemier BM, et al. Costs and effects of screening and treating low risk women with a singleton pregnancy for asymptomatic bacteriuria, the ASB study. BMC pregnancy and childbirth. 2012;12:52. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-12-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Guinto VT, De Guia B, Festin MR, Dowswell T. Different antibiotic regimens for treating asymptomatic bacteriuria in pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010:CD007855. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007855.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lumbiganon P, et al. One-day compared with 7-day nitrofurantoin for asymptomatic bacteriuria in pregnancy: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113:339–345. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318195c2a2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Widmer M, Gulmezoglu AM, Mignini L, Roganti A. Duration of treatment for asymptomatic bacteriuria during pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011:CD000491. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000491.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cai T, et al. The role of asymptomatic bacteriuria in young women with recurrent urinary tract infections: to treat or not to treat? Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55:771–777. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Smith HS, et al. Antecedent antimicrobial use increases the risk of uncomplicated cystitis in young women. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;25:63–68. doi: 10.1086/514502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mohler JL, Cowen DL, Flanigan RC. Suppression and treatment of urinary tract infection in patients with an intermittently catheterized neurogenic bladder. The Journal of urology. 1987;138:336–340. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)43138-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Maynard FM, Diokno AC. Urinary infection and complications during clean intermittent catheterization following spinal cord injury. The Journal of urology. 1984;132:943–946. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)49959-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Loeb M, et al. Development of minimum criteria for the initiation of antibiotics in residents of long-term-care facilities: results of a consensus conference. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2001;22:120–124. doi: 10.1086/501875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.D'Agata E, Loeb MB, Mitchell SL. Challenges in assessing nursing home residents with advanced dementia for suspected urinary tract infections. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61:62–66. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Leone M, et al. Risk factors of nosocomial catheter-associated urinary tract infection in a polyvalent intensive care unit. Intensive Care Med. 2003;29:1077–1080. doi: 10.1007/s00134-003-1767-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Golob JF, Jr, et al. Fever and leukocytosis in critically ill trauma patients: it's not the urine. Surg Infect (Larchmt) 2008;9:49–56. doi: 10.1089/sur.2007.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chant C, Smith OM, Marshall JC, Friedrich JO. Relationship of catheter-associated urinary tract infection to mortality and length of stay in critically ill patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Crit Care Med. 2011;39:1167–1173. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31820a8581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Leone M, et al. A randomized trial of catheter change and short course of antibiotics for asymptomatic bacteriuria in catheterized ICU patients. Intensive Care Med. 2007;33:726–729. doi: 10.1007/s00134-007-0534-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Drekonja DM, Zarmbinski B, Johnson JR. Preoperative Urine Cultures at a Veterans Affairs Medical Center. Arch Intern Med. 2012:1–2. doi: 10.1001/2013.jamainternmed.834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rajamanickam A, Noor S, Usmani A. Should an asymptomatic patient with an abnormal urinalysis (bacteriuria or pyuria) be treated with antibiotics prior to major joint replacement surgery? Cleve Clin J Med. 2007;74(1):S17–18. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.74.electronic_suppl_1.s17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wymenga AB, van Horn JR, Theeuwes A, Muytjens HL, Slooff TJ. Perioperative factors associated with septic arthritis after arthroplasty. Prospective multicenter study of 362 knee and 2,651 hip operations. Acta Orthop Scand. 1992;63:665–671. doi: 10.1080/17453679209169732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Cordero-Ampuero J, Gonzalez-Fernandez E, Martinez-Velez D, Esteban J. Are Antibiotics Necessary in Hip Arthroplasty With Asymptomatic Bacteriuria? Seeding Risk With/Without Treatment. Clinical orthopaedics and related research. 2013 doi: 10.1007/s11999-013-2868-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.van Hees BC, et al. Single-dose antibiotic prophylaxis for urinary catheter removal does not reduce the risk of urinary tract infection in surgical patients: a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Clinical microbiology and infection: the official publication of the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases. 2011;17:1091–1094. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2010.03447.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Pinochet R, et al. Role of short-term antibiotic therapy at the moment of catheter removal after laparoscopic radical prostatectomy. Urologia internationalis. 2010;85:415–420. doi: 10.1159/000321094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Pfefferkorn U, et al. Antibiotic prophylaxis at urinary catheter removal prevents urinary tract infections: a prospective randomized trial. Ann Surg. 2009;249:573–575. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31819a0315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Marschall J, Carpenter CR, Fowler S, Trautner BW Program, C.D.C.P.E. Antibiotic prophylaxis for urinary tract infections after removal of urinary catheter: meta-analysis. BMJ. 2013;346:f3147. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f3147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Loeb M, et al. Effect of a multifaceted intervention on number of antimicrobial prescriptions for suspected urinary tract infections in residents of nursing homes: cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2005;331:669. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38602.586343.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bonnal C, et al. Bacteriuria in a geriatric hospital: impact of an antibiotic improvement program. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2008;9:605–609. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2008.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Egger M, Balmer F, Friedli-Wuthrich H, Muhlemann K. Reduction of urinary catheter use and prescription of antibiotics for asymptomatic bacteriuria in hospitalised patients in internal medicine: before-and-after intervention study. Swiss medical weekly. 2013;143:w13796. doi: 10.4414/smw.2013.13796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Pettersson E, Vernby A, Molstad S, Lundborg CS. Can a multifaceted educational intervention targeting both nurses and physicians change the prescribing of antibiotics to nursing home residents? A cluster randomized controlled trial. The Journal of antimicrobial chemotherapy. 2011;66:2659–2666. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkr312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Zabarsky TF, Sethi AK, Donskey CJ. Sustained reduction in inappropriate treatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria in a long-term care facility through an educational intervention. Am J Infect Control. 2008;36:476–480. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2007.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Pavese P, et al. Does an educational session with an infectious diseases physician reduce the use of inappropriate antibiotic therapy for inpatients with positive urine culture results? A controlled before-and-after study. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2009;30:596–599. doi: 10.1086/597514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Linares LA, Thornton DJ, Strymish J, Baker E, Gupta K. Electronic memorandum decreases unnecessary antimicrobial use for asymptomatic bacteriuria and culture-negative pyuria. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2011;32:644–648. doi: 10.1086/660764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Epstein RM. Mindful practice. JAMA. 1999;282:833–839. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.9.833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Flanders SA, Saint S. Enhancing the safety of hospitalized patients: who is minding he antimicrobials? Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:38–40. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Trautner BW, et al. A hospital-site controlled intervention using audit and feedback to implement guidelines concerning inappropriate treatment of catheter-associated asymptomatic bacteriuria. Implement Sci. 2011;6:41. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-6-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Naik AD, Hinojosa-Lindsey M, Arney J, El-Serag HB, Hou J. Choosing wisely and the perceived drivers of endoscopy use. Clinical gastroenterology and hepatology: the official clinical practice journal of the American Gastroenterological Association. 2013;11:753–755. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Hulscher ME, van der Meer JW, Grol RP. Antibiotic use: how to improve it? nternational journal of medical microbiology: IJMM. 2010;300:351–356. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2010.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Cabana MD, et al. Why don't physicians follow clinical practice guidelines? A framework for improvement. JAMA. 1999;282:1458–1465. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.15.1458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Werner NL, Hecker MT, Sethi AK, Donskey CJ. Unnecessary Use of Fluoroquinolone Antibiotics in Hospitalized Patients. BMC Infect Dis. 2011;11:187. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-11-187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Saint S, Meddings JA, Calfee D, Kowalski CP, Krein SL. Catheter-associated urinary tract infection and the Medicare rule changes. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:877–884. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-12-200906160-00013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Hecker MT, Aron DC, Patel NP, Lehmann MK, Donskey CJ. Unnecessary use of antimicrobials in hospitalized patients: current patterns of misuse with an emphasis on the antianaerobic spectrum of activity. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:972–978. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.8.972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Dalen DM, Zvonar RK, Jessamine PG. An evaluation of the management of asymptomatic catheter-associated bacteriuria and candiduria at The Ottawa Hospital. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol. 2005;16:166–170. doi: 10.1155/2005/868179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Gandhi T, Flanders SA, Markovitz E, Saint S, Kaul DR. Importance of urinary tract infection to antibiotic use among hospitalized patients. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2009;30:193–195. doi: 10.1086/593951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]