Abstract

Bullet embolism is a rare phenomenon following gunshot injuries. We present a case of a 25-year-old male who sustained a gunshot wound to his left globe with the bullet initially lodged in his right transverse sinus. The bullet ultimately embolized to a left lower lobe pulmonary artery resulting in a pulmonary infarct. A discussion of select prior cases, pathophysiology, and management strategies follows.

Keywords: Bullet embolism, cranial venous sinus, gunshot wound, pulmonary infarct

INTRODUCTION

Gunshot injuries to the head pose many unique challenges. In cases were a penetrating projectile is retained intracranially, migration or embolization of the missile can occur. To date, there have been fewer than 200 published cases of a bullet embolism of which only a few occurred following a gunshot wound to the head. The first report of a bullet embolism from a cranial venous sinus to the heart occurred in 1964 and was published by Hiebert et al. in 1974.[1] Since, four additional cases of bullet emboli originating after a gunshot to the head and traveling to the heart or pulmonary arteries have been described.[2,3,4] We present a case of a pulmonary infarction following a bullet embolism originating from a cranial venous sinus.

CASE REPORT

A 25-year-old male was brought to the emergency department after being found at the side of the road. At presentation, the patient was unconscious. His vital signs were: blood pressure of 145 mmHg systolic over 122 mmHg diastolic, heart rate of 130 beats/min, respiratory rate of 24, and peripheral oxygen saturation of 91% on room air. Physical exam was notable for facial lacerations and a ruptured left globe related to a gunshot entrance wound. No exit wound was identified. A head computed tomography (CT) demonstrated the trajectory of the bullet, which had ruptured his left globe, travelled along the skull base fracturing his carotid canals bilaterally, and was located in the right transverse sinus [Figure 1a]. The bullet was round and measured approximately 5 mm in diameter, the characteristic size and shape of a BB gun bullet.

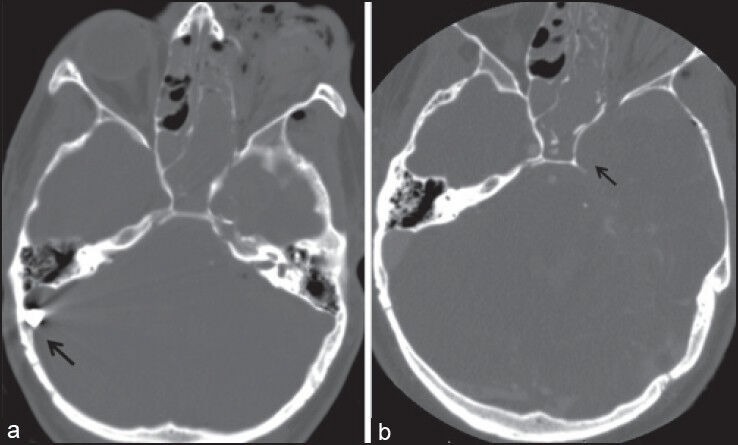

Figure 1.

(a) Admission head computed tomography demonstrates a metallic foreign body projecting in the region of the right transverse sinus (arrow) (b) the bullet previously seen in the right transverse sinus is no longer evident on the follow-up head computed tomography angiography

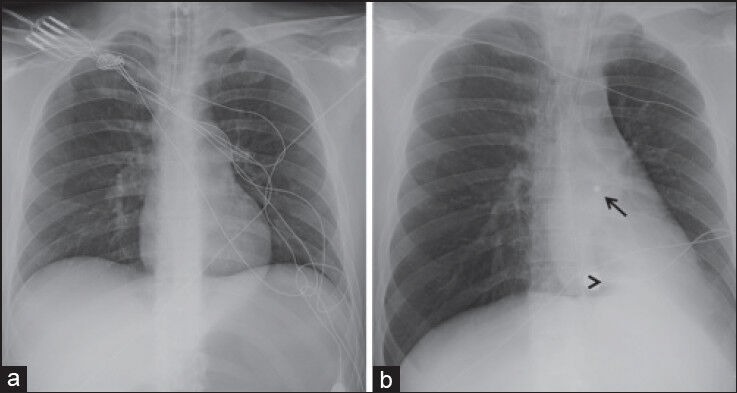

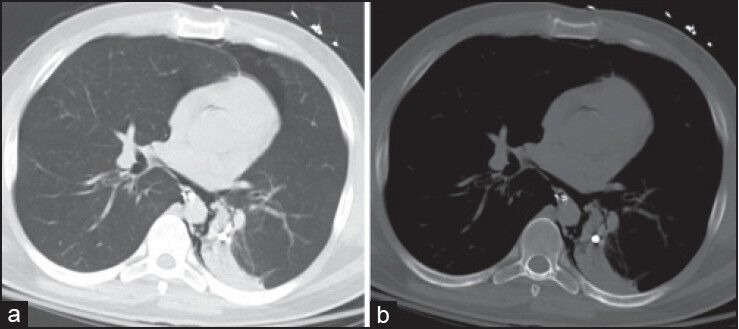

Due to extensive intracranial haemorrhage, the patient was taken to the operating room for placement of an external ventriculostomy shunt catheter. Post-operatively, contrast enhanced computed tomography angiography of the head was performed, which demonstrated occlusion of the left internal carotid artery [Figure 1b]. However, it was also noted that the previously identified bullet was no longer located in the right transverse sinus. At admission, a portable chest radiograph had been unremarkable [Figure 2a]. Approximately 2.5 h later, a repeat post-operative chest radiograph showed a new round foreign body resembling a BB that projected over the left hilum with interval development of a wedge shaped pulmonary opacity silhouetting the left hemidiaphragm [Figure 2b]. It was suspected that the BB had embolized through the right jugular vein to the patient's heart and to a peripheral branch of a left lower lobe pulmonary artery. Chest CT confirmed that the bullet was now located in a left lower lobe with an associated pulmonary infarct, a small left-sided pneumothorax, and extensive pneumomediastinum [Figure 3a and 3b]. The patient was admitted to the intensive care unit and evaluated by cardiothoracic surgery. No intervention to remove the bullet was performed as the patient was critically ill from a neurological perspective.

Figure 2.

Chest radiograph obtained at admission (a) demonstrates no cardiopulmonary abnormality. A follow-up chest radiograph (b) shows a 5 mm round metallic foreign body projecting over the left hilum (open arrow) with interval development of a wedge shaped pulmonary opacity a the left lung base (arrow head)

Figure 3.

Lung and bone windows (3a and 3b respectively) again show the 5 mm rounded metallic foreign body in the left lower lobe with an associated pulmonary infarct. A small left anterior pneumothorax and pneumomediastinum are also seen

DISCUSSION

The scenario for bullet embolism is set up when a low-velocity projectile consumes enough kinetic energy on the initial tissue penetration such that it only penetrates a single wall of a vessel, coming to rest within the lumen.[5] This occurs most commonly with small-caliber, relatively low-powered projectiles such as BBs, 0.22 caliber bullets, airgun pellets or shotguns ammunition, which scatters multiple small metallic pellets. Forces, which then influence the migration of an intravascular foreign body include: Hydrostatic pressure from blood flow, gravity, patient body position, and vascular anatomy.[5] The diagnosis of bullet embolism is often demonstrated on serial imaging evaluations as occurred in the presented case. Bullet embolism may also be suspected when there is no exit wound and the expected location of a missile, based on its projected trajectory, is discordant with the radiographic findings. In the past, arteriography has been used to increase diagnostic confidence.[5]

Both venous and arterial emboli have been sporadically reported. Arterial emboli typical migrate peripherally to an extremity and present early with limb or end-organ ischemia. Thus, operative management with embolectomy is generally agreed upon for arterial bullet emboli. Venous emboli typically travel centrally to the heart or pulmonary arteries; although, retrograde emboli have also been reported. The management of venous emboli, which are more commonly asymptomatic, remains controversial. Some authors have argued that operative management of a bullet in the heart or pulmonary arteries is necessary.[5,6,7] A review of seventeen patients with bullet emboli in the pulmonary arteries by Stephenson et al. found that seven out of nine patients died when embolectomy was not performed, compared to no deaths in eight patients who underwent surgical embolectomy.[7] However, it is not clear whether the deceased patients were too ill for surgery and if operative management would have affected the outcome. Moreover, all of the deaths reported by Stephenson et al. occurred prior to 1942 and complications requiring a second thoracotomy were presented in half of the cases where surgical management was employed.[7] Due to the morbidity associated with embolectomy, conservative management has also been proposed for pulmonary arterial emboli, citing numerous cases that were managed by observation alone resulting in few complications and no deaths.[8] The recent evolution of endovascular techniques for bullet retrieval has decreased the need for open thoracotomy and anecdotally reduced the complications associated with embolectomy. Therefore, a more recent review by Miller et al. advocates the retrieval of all intracardiac missile emboli and those pulmonary arterial emboli, which are easily accessible through an endovascular approach, even in the absence of symptoms, to prevent delayed complications.[9]

CONCLUSION

Bullet embolization is a rare complication of gunshot injuries to the head and requires a high index of suspicion for prompt diagnosis. Treatment of venous bullet emboli remains controversial.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hiebert CA, Gregory FJ. Bullet embolism from the head to the heart. JAMA. 1974;229:442–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goldman RL, Carmody RF. Foreign body pulmonary embolism originating from a gunshot wound to the head. J Trauma. 1984;24:277–9. doi: 10.1097/00005373-198403000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nehme AE. Intracranial bullet migrating to pulmonary artery. J Trauma. 1980;20:344–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hughes BD, Vender JR. Delayed lead pulmonary emboli after a gunshot wound to the head. Case report. J Neurosurg. 2006;105:233–4. doi: 10.3171/ped.2006.105.3.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Symbas PN, Harlaftis N. Bullet emboli in the pulmonary and systemic arteries. Ann Surg. 1977;185:318–20. doi: 10.1097/00000658-197703000-00012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.John LC, Edmondson SJ. Bullet pulmonary embolus and the role of surgery. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1991;39:386–8. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1020007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stephenson LW, Workman RB, Aldrete JS, Karp RB. Bullet emboli to the pulmonary artery: A report of 2 patients and review of the literature. Ann Thorac Surg. 1976;21:333–6. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(10)64322-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kortbeek JB, Clark JA, Carraway RC. Conservative management of a pulmonary artery bullet embolism: Case report and review of the literature. J Trauma. 1992;33:906–8. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199212000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miller KR, Benns MV, Sciarretta JD, Harbrecht BG, Ross CB, Franklin GA, et al. The evolving management of venous bullet emboli: A case series and literature review. Injury. 2011;42:441–6. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2010.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]