Abstract

Background:

Bronchiolitis is a self-limiting disease of children caused by viral infections of the small airways with a wide spectrum of illness severity. Search of the literature reveals a need for refinement of criteria for testing for concomitant severe bacterial infections as well as appropriate therapeutic interventions for patients <90-day-old diagnosed with clinical bronchiolitis. We believe that a better understanding of the disease spectrum will help optimize health-care delivery to these patients.

Aims:

The aim of this study was to determine the clinical profile at presentation, disease course and outcome of bronchiolitis in <3-month-old infants who presented to our Pediatric Emergency Department (PED) during one disease season.

Settings:

Retrospective chart review during one bronchiolitis season, from November 1, 2011 to April 20, 2012.

Subjects:

All <90-day-old infants presenting with clinical bronchiolitis presenting to Urban PED of a tertiary care university hospital during one bronchiolitis season.

Materials and Methods:

A retrospective chart review based on computer records of all emergency department visits of infants less than 90 days with a clinical diagnosis of bronchiolitis, covering the period between November 1, 2011 and April 30, 2012.

Results:

Out of the total of 1895 infants <90 days of age, 141 had a clinical diagnosis of bronchiolitis and 35 needed admission to hospital. Blood for culture was obtained from 47 infants, urine for culture was obtained from 46 infants and cerebrospinal fluid for culture was obtained from eight infants. One case of bacteremia was documented, but this was found to be a contaminant. No cases of meningitis occurred among these infants. However, one infant had a positive urine culture consistent with infection (Escherichia coli).

Conclusion:

Based on the results, it can be conclude that the risk of bacteremia or meningitis among infants <90 days of age with fever and bronchiolitis is low. The risk of urinary tract infection in this age group is also low, but it is higher than the risk for meningitis or bacteremia. Our data for admission and treatment guidelines are similar to those published from other countries.

Keywords: Bronchiolitis, septic screening, urinary tract infection

INTRODUCTION

Bronchiolitis is a self-limiting lower airway disease of infants and young children. It is usually caused by a viral infection of the small airways (bronchioles). Approximately, 75% of bronchiolitis cases occur in children younger than 1 year of age and 95% occur in children younger than 2 years of age, with peak incidence at 2-8 months of age. In the United States, the annual incidence is 11.4% in children below 1 year of age and 6% in those aged 1-2 years. Approximately, 23-31% cases of bronchiolitis are associated with fever.[1,2,3]

There is much controversy regarding the appropriateness and the extent of routine testing for bacterial infections that should be performed when evaluating febrile infants. Suggested clinical guidelines recommend testing of blood, urine and cerebrospinal fluid for most, if not all, of these infants if there is no obvious source of fever.[4,5]

Many risk factors for severe bronchiolitis in newborns have been proposed. However, the profile of these children requires further investigation to identify those at risk of severe illness or concomitant secondary infections in order to further refine diagnostic and therapeutic interventions for newborns with bronchiolitis.

Bronchiolitis leads to numerous hospital admissions for children under the age of 5.[6] World Health Organization statistics estimate the global burden of respiratory syncytial virus at 64 million cases, with around 16,000 deaths annually.[7]

A previous study on Saudi children conducted in this hospital showed that 79% of the children admitted with acute respiratory tract infections were diagnosed with respiratory syncytial virus infection.[8]

The aim of this study is to document the clinical profile of <90-day-old infants diagnosed with bronchiolitis at our emergency department and to follow their clinical course and outcome.

We believe that a better understanding of the clinical profile of the disease will help optimize health-care delivery to patients with bronchiolitis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We conducted a retrospective chart review based on computer records of all emergency department visits of infants less than 90 days with a clinical diagnosis of bronchiolitis, covering the period between November 1, 2011 and April 30, 2012. The institutional review board of King Saud University Hospital approved this study.

Our emergency department serves a diverse socioeconomic population, consisting of Saudi nationals and eligible multinational expatriates.

Charts were reviewed for documentation of presenting symptoms, vital signs and signs of upper respiratory tract infection as well as for findings of lower tract disease such as wheezing, bilateral rales and retractions. Those meeting the clinical definition of bronchiolitis, upper respiratory tract infection signs along with lower tract involvement, were eligible for analysis. Those charts with a treating physician's diagnosis of Bronchiolitis were selected.

Emergency department, hospital and laboratory records were reviewed and data were extracted and recorded on a standardized pro forma sheet. Demographic and historical data, such as history of prematurity, congenital heart disease, chronic medications, reported difficult or poor feeding, apnea, cyanosis and fever, were recorded. Collected clinical data included signs or symptoms of congestion, rhinorrhea, cough, temperature, tachypnea, respiratory distress, crackles, rales, wheezing and/or hypoxia as determined by pulse oximetry. Tachypnea was defined as a respiratory rate of >60/min while hypoxia was defined by oxygen saturation of 92% or less by pulse oximetry. Data regarding treatment given in the emergency department (bronchodilators/saline nebulizer/epinephrine/antibiotics) were also recorded as were the results of arterial blood gas, urinalysis and blood and/or cerebrospinal fluid culture along with the disposition of patients.

Patients deemed clinically fit for discharge directly from the emergency department were contacted by telephone 2 weeks after discharge to inquire whether they revisited an emergency department or pediatric clinic for the same illness and if any interventions were needed. Those patients who did not respond on the first call were called up again after 1 and 2 weeks before being reported as failed to contact.

RESULTS

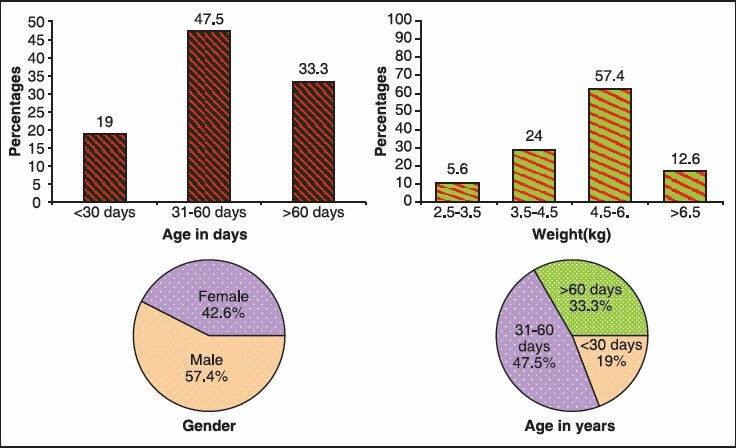

A total of 1895 infants aged 0-90 days presented to the emergency department during the study period. Of these, 141 infants were received an emergency department disposition diagnosis of bronchiolitis. 27 (19%) infants were <30 days of age while 67 (47.4%) and 47 (33%) were 30-60 and 60-90 days of age, respectively. There were 81 male and 60 female infants. Mean patient weight was 5.21 kg (±1.18). 35 patients (24%) required hospitalization for further management. Of these, 3 needed admission in the pediatric intensive care unit (PICU) and required ventilation. Overall, 104 patients (74%) were discharged home directly from the emergency department by the treating physician [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Characteristics of patients studied

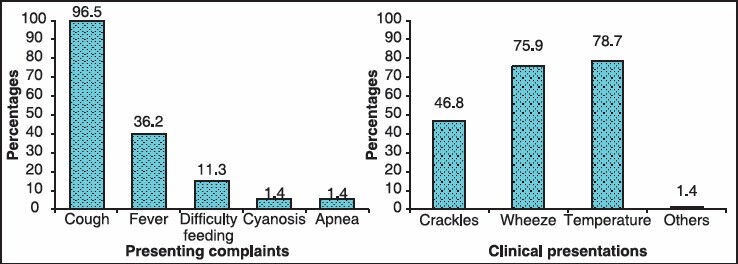

Almost all infants had cough (96%) as the chief presenting complaint, followed closely by tactile temperature and feeding difficulty. Two patients presented with a history of cyanosis as well as apnea. A respiratory rate of >60/min was noted in 12 patients (8.4%) and SpO2 of <90% was recorded in 6 (4.2%) patients. Crackles (47%) and wheezing (76%) were prominent clinical findings. A rectal temperature of ≥38°C was noted in 111 patients (78.7%) [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

Clinical presentation of patients studied

Four patients each had prematurity and congenital heart disease as a risk factor. One was a case of Downs's syndrome and seven had a previous diagnosis of reactive airway disease, two patients had a cleft lip + palate, one had gastroesophageal reflux disease and another one had Idiopathic Thrombocytopenia.

At our institution, we do not perform routine laboratory investigations for all patients with bronchiolitis. Patients less than 3 months who appear sick according to the treating physician or patients with documented temperatures of ≥38°C are screened for sepsis as per the Pediatric Emergency Department (PED) fever protocol.

Nasopharyngeal aspiration for diagnosis of viral infection is performed mainly on patients admitted for respiratory isolation. The nasopharyngeal aspirate was tested for respiratory syncytial virus in 83 patients, of which 45 (54%) yielded positive results. Of the 47 infants who had a blood culture drawn, only 1 (2%) indicated positive growth, which was found to be a contaminant.

Urine for culture was obtained from 46 patients by urethral catheterization. The cultures for five patients were contaminated. Escherichia coli was isolated as a pathogen in one urine sample only. None of the cultures from the eight cerebrospinal fluid samples obtained by lumbar puncture were positive for bacterial growth.

High flow oxygen with nebulization was used in 39 (27.7%) patients. Seven patients were given a trial with racemic epinephrine by treating physicians in the emergency room. Hypertonic Saline nebulization was used in 38 (26.9%) patients. Of the 141 patients, 111 (78%) were initially treated with inhaled bronchodilators and 25 (17%) received antibiotics empirically during their hospital admission.

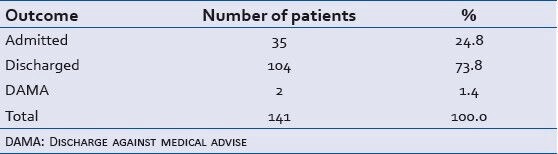

Mean duration of hospital stay for admitted patients was 7 ± 4.03 days. All three patients admitted to the PICU needed ventilatory support. No mortality occurred in the study population [Table 1].

Table 1.

Distribution of outcome of patients studied

We were able to contact the parents of 101 of 107 patients discharged directly from the emergency department for a telephone interview. Only four of these patients required a second hospital visit for the same illness and none required admission into a hospital.

DISCUSSION

Clinical management of <3-month-old febrile infants who have no focus of infection is variable and is determined by multiple patient- and clinician-specific factors.[9,10] Although bronchiolitis is a common disease among infants, little consensus exists regarding its optimal management. No specific treatment appears to have a clear beneficial effect on the course of the disease.

Infants with co-existing cardiac or respiratory disease and 1-3-month-old neonates are more likely to require hospital admission. The vast majority of children with bronchiolitis develop mild disease and can be treated at home. In the U.S., more than 700,000 infants visited emergency departments for treatment of lower respiratory tract infections during bronchiolitis season between years 1997 and 2000. Of these, 29% of infants were admitted for in-patient care.

Our hospitalization rate of 25.5% among infants evaluated in the emergency department for bronchiolitis is consistent with previously published statistics.[11,12,13,14]

Hospital admissions due to Bronchiolitis have increased considerably since 1980 and have become a problem of public health world-wide. This has led to overcrowding of PEDs especially in winters and uses a lot of hospital resources. Some studies have also shown an increase of visits to the PED by infants with acute bronchiolitis compared with previous decades.[15,16]

A cochrane review of eight randomized trials of bronchiolitis in a total of 394 children showed an improvement in clinical scores when bronchodilators were used. This improvement was not regarded as clinically significant; however, there was no associated improvement in oxygenation or rates of hospital admission.[17] The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends “bronchodilators should not be used routinely in the management of bronchiolitis.”[18] In our study, bronchodilators were used in 78.7% of patients, slightly higher than the percentage (˜64.1%) reported in other countries.[16]

This study was performed primarily to evaluate the effectiveness of sepsis evaluation in infants with clinical bronchiolitis. Previous studies have attempted to assess the likelihood of bacterial infections in patients with bronchiolitis. Kuppermann et al. analyzed data from 156 < 24-month-old children with fever and bronchiolitis. They found no cases of bacteremia and only 2% of these patients had a urinary tract infection.[19]

Liebelt et al. studied 211 consecutive infants aged 90 days or younger (median age, 54 days) with 216 episodes of bronchiolitis. Fever occurred in 72 of these children, none of whom had a urinary tract infection, bacteremia or meningitis.[20]

Melendez and Harper evaluated 329 < 90-day-old febrile infants with bronchiolitis over a 5-year period. None of these children had meningitis or bacteremia, but 6 male infants (2%) tested positive for a urinary tract infection.[21]

Our data reinforces the previous reports of concomitant urinary tract infections (URI) in children less than 90 days diagnosed with clinical Bronchiolitis, with 1 out of 46 patients testing positive on urine culture.

This being a single-center study is limited by institutional pattern of referral, presentation and practice. Retrospective chart reviews like ours are prone to uncertainty regarding both clinical factors (e.g., ill appearance) and selection or ascertainment (e.g., who gets diagnosed with URI, who gets diagnosed with fever, who gets diagnosed with bronchiolitis, who gets selected for infection testing, who gets selected for admission). However, our high rate of phone follow-up limits the issue of selective testing in patients missing infections.

CONCLUSION

Our study complements previously published data showing a low incidence of positive blood or spinal fluid cultures among infants with bronchiolitis. The risk of bacteremia or meningitis is low in <90-day-old infants with fever and bronchiolitis and the risk of urinary tract infection in this age group, though not negligible, is similarly low.

This study questions the utility of a full septic work-up in infants <3 months with bronchiolitis. However, urine screening should be done for infants with bronchiolitis. Our study is very small and a single center study to make any recommendation on clinical practice.

We conclude that the risk of bacteremia or meningitis among infants <90 days of age with fever and bronchiolitis is low. The risk of urinary tract infection in this age group is also low, but it is higher than the risk for meningitis or bacteremia. Our data for admission and treatment guidelines are similar to those published from other countries.

Whereas, we infer that further multicenter prospective studies need to be undertaken to investigate the role of routine septicemic screening in infants <90 days of age diagnosed with clinical bronchiolitis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors acknowledge the support provided by the Research Center of College of Medicine, King Saud University, in preparation of this article.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Research Centre of College of Medicine, King Saud University.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.El-Radhi AS, Barry W, Patel S. Association of fever and severe clinical course in bronchiolitis. Arch Dis Child. 1999;81:231–4. doi: 10.1136/adc.81.3.231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brandenburg AH, Jeannet PY, Steensel-Moll HA, Ott A, Rothbarth PH, Wunderli W, et al. Local variability in respiratory syncytial virus disease severity. Arch Dis Child. 1997;77:410–4. doi: 10.1136/adc.77.5.410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hall CB. Respiratory syncytial virus: A continuing culprit and conundrum. J Pediatr. 1999;135:2–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baraff LJ, Bass JW, Fleisher GR, Fleisher GR, Klein JO, McCracken GH, Jr, et al. Practice guideline for the management of infants and children 0-36 months of age with fever without source. Pediatrics. 1993;92:1–12. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(05)80991-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Levine DA, Platt SL, Dayan PS, Macias CG, Zorc JJ, Krief W, et al. Risk of serious bacterial infection in young febrile infants with respiratory syncytial virus infections. Pediatrics. 2004;113:1728–34. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.6.1728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hacking D, Hull J. Respiratory syncytial virus - Viral biology and the host response. J Infect. 2002;45:18–24. doi: 10.1053/jinf.2002.1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Acute Respiratory Infections. [Last update on 2009 September; Last accessed on 2013 Feb 18]. Available from: http://www.who.int .

- 8.Bakir TM, Halawani M, Ramia S. Viral aetiology and epidemiology of acute respiratory infections in hospitalized Saudi children. J Trop Pediatr. 1998;44:100–3. doi: 10.1093/tropej/44.2.100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smitherman HF, Macias CG. Evaluation and management of fever in the neonate and young infant (less than three months of age) UpToDate Version 19. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hernandez DA. Fever in infants <3 months old: What is the current standard? Pediatr Emerg Med Rep. 2011;Vol 16(Number 1):1–14. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shaw KN, Bell LM, Sherman NH. Outpatient assessment of infants with bronchiolitis. Am J Dis Child. 1991;145:151–5. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1991.02160020041012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schuh S, Coates AL, Binnie R, Allin T, Goia C, Corey M, et al. Efficacy of oral dexamethasone in outpatients with acute bronchiolitis. J Pediatr. 2002;140:27–32. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2002.120271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smyth RL, Openshaw PJ. Bronchiolitis. Lancet. 2006;368:312–22. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69077-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.King VJ, Viswanathan M, Bordley WC, Jackman AM, Sutton SF, Lohr KN, et al. Pharmacologic treatment of bronchiolitis in infants and children: A systematic review. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2004;158:127–37. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.158.2.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tinsa F, Ben Rhouma A, Ghaffari H, Boussetta K, Zouari B, Brini I, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of nebulized terbutaline for the first acute bronchiolitis in infants less than 12-months-old. Tunis Med. 2009;87:200–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sakellaropoulou A, Emporiadou M, Aivazis V, Mauromixalis J, Hatzistilianou M. Acute bronchiolitis in a paediatric emergency department of Northern Greece. Comparisons between two decades. Arch Med Sci. 2012;8:509–14. doi: 10.5114/aoms.2012.29279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kellner JD, Ohlsson A, Gadomski AM, Wang EE. Bronchodilators for bronchiolitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2000;(2):CD001266. Review. Update in: Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006;(3):CD001266. PubMed PMID: 10796626. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Leader S, Kohlhase K. Recent trends in severe respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) among US infants, 1997 to 2000. J Pediatr. 2003;143:S127–32. doi: 10.1067/s0022-3476(03)00510-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kuppermann N, Bank DE, Walton EA, Senac MO, Jr, McCaslin I. Risks for bacteremia and urinary tract infections in young febrile children with bronchiolitis. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1997;151:1207–14. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1997.02170490033006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liebelt EL, Qi K, Harvey K. Diagnostic testing for serious bacterial infections in infants aged 90 days or younger with bronchiolitis. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999;153:525–30. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.153.5.525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Melendez E, Harper MB. Utility of sepsis evaluation in infants 90 days of age or younger with fever and clinical bronchiolitis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2003;22:1053–6. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000101296.68993.4d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]