Abstract

Background

The Omaha System (OS) is one of the oldest of the American Nurses Association recognized standardized terminologies describing and measuring the impact of healthcare services. This systematic review presents the state of science on the use of the OS in practice, research, and education.

Aims

(1) To identify, describe and evaluate the publications on the OS between 2004 and 2011, (2) to identify major trends in the use of the OS in research, practice, and education, and (3) to suggest areas for future research.

Methods

Systematic search in the largest online healthcare databases (PUBMED, CINAHL, Scopus, PsycINFO, Ovid) from 2004 to 2011. Methodological quality of the reviewed research studies was evaluated.

Results

56 publications on the OS were identified and analyzed. The methodological quality of the reviewed research studies was relatively high. Over time, publications’ focus shifted from describing clients’ problems toward outcomes research. There was an increasing application of advanced statistical methods and a significant portion of authors focused on classification and interoperability research. There was an increasing body of international literature on the OS. Little research focused on the theoretical aspects of the OS, the effective use of the OS in education, or cultural adaptations of the OS outside the USA.

Conclusions

The OS has a high potential to provide meaningful and high quality information about complex healthcare services. Further research on the OS should focus on its applicability in healthcare education, theoretical underpinnings and international validity. Researchers analyzing the OS data should address how they attempted to mitigate the effects of missing data in analyzing their results and clearly present the limitations of their studies.

Keywords: Nursing Informatics, Terminology as Topic, Data Mining, Omaha System, Nursing Classification

Introduction

For more than four decades, the Omaha System (OS) served healthcare providers in diverse settings as a standardized terminology for documentation of clinical information and to support healthcare research. First developed in the early 1970s by practitioners at the Visiting Nurse Association (VNA) of Omaha as a system for documentation and management of home care services, the applicability and validity of the OS increased steadily through the decades. Currently, the OS—one of the oldest of the American Nurses Association recognized nursing standardized terminologies—is widely applied across healthcare disciplines and settings in the USA and internationally.1

The aim of this paper is to report on a systematic review of the recent publications on the OS. A previous review on the topic was published 8 years ago.2 With the recent flurry of progress in electronic health records (EHRs) and informatics research, there is a critical need to identify the evidence that was published since then. Recent publications on the OS should be reviewed and analyzed to identify ways in which clinical data produced by nurses and other healthcare professionals might be meaningfully used from EHRs. Appropriate presentation of this information may enable healthcare providers, researchers, and other stakeholders to further understand how standardized EHR data may lead to improved quality of care and decreased costs.

Background

Historic development of the OS

Early in the 1970s, the VNA of Omaha practitioners, managers, and administrators recognized the growing need to quantify professional healthcare practice. The VNA developed a vision of building a system that will use standardized terminology to describe and operationalize the nursing process. This vision and the combined efforts of the VNA and several academic institutions resulted in the creation of the OS. Between the 1970s and late 1990s, researchers, educators, and managers from diverse healthcare disciplines received several federal grants to further develop and expand the usefulness, validity, and reliability of the OS.1 Today, the OS is a comprehensive standardized terminology designed to generate comprehensive data for the description and evaluation of client care.

The OS structure

The OS model, originally based on the problem-solving approach proposed by Weed,3 includes three basic steps: problem–intervention–outcome.4 In the first step, also called the Problem Classification Scheme (PCS), healthcare practitioners collect assessment data, such as signs and symptoms, to identify patients’ problems and to formulate diagnoses. The PCS consists of four domains: environmental, psychosocial, physiological, and health-related behaviors. Forty-two problems are categorized under one of the four domains, and are identified by the signs and symptoms of the problem, the focus of the problem (individual, family, or community), and whether the problem is actual, potential, or encompasses the clients’ needs for health-promotion. During the second step, or the Intervention Scheme, the actual intervention is implemented by the provider. There are four intervention categories: health teaching, guidance, and counseling; treatments and procedures; case management; and surveillance. Specific nursing interventions are further delineated through the use of 75 targets (eg, ‘cardiac care’ or ‘dietary management’). In the final step, Problem Rating Scale for Outcomes, the provider evaluates the care process by measuring its outcomes on a Likert scale in the area of knowledge, behavior, and status of each problem.1

Developers of the OS emphasized the importance of a multidisciplinary team approach and generated the standardized terminology to encompass terms used by diverse healthcare professionals. The OS is recognized by national organizations in the USA and integrated into the National Library of Medicine's Unified Medical Language System (UMLS) Metathesaurus; Logical Observation Identifiers, Names, and Codes (LOINC); and Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine–Clinical Terms (SNOMED CT). The OS is available in the public domain at http://www.omahasystem.org.

Theoretical framework

Several theoretical frameworks influenced the development of the OS. First, the OS is rooted in the Donabedian healthcare quality model.5 According to this model, healthcare quality might be explained and evaluated by taking into consideration three aspects: (1) structure (characteristics of the care providers, their tools and resources, and the physical/organizational setting); (2) process (both interpersonal and technical aspects of the treatment process); and (3) outcome (change in the patient's symptoms and functioning). The Neuman Systems Model is a nursing theoretical model that affected the development of the OS. According to this model, the nursing process might be represented by three consecutive steps: (1) nursing diagnosis, (2) nursing goals, and (3) nursing outcomes.6 Additionally, the OS structure supports the critical thinking process; it starts with seeking information and describing the existing situation, continues to the identification of the problem and intervention, and ends with the evaluation of the effectiveness of the applied steps.7 8

Aims

The goals of this systematic review on the OS were: (1) to identify, describe, and evaluate the publications on the OS between 2004 and 2011; (2) to identify major trends in the use of the OS in research, practice, and education; and (3) to suggest areas for future research.

Methods

The previous literature review on the OS included articles published between the years 1983 and 2003.2 To build on this work and create a current state of the science, this review included articles published between 1 January 2004 and 31 December 2011. We decided to review articles published in English to enable a thorough understanding of the included manuscripts. To find the relevant literature, the keyword ‘OS’ was used to conduct a computerized search in the major biomedical and behavioral databases, namely PUBMED, CINAHL, Scopus, PsycINFO, and Ovid. The search was conducted with free text and used major terms, when applicable (eg, MeSH categories in PUBMED). Moreover, reference lists of the relevant articles and the OS website were reviewed to identify additional publications.

Articles were included in this review if they discussed, presented, or analyzed the OS and were written in English between 2004 and 2011. After being selected for the review, each article was read completely and then categorized to one of five categories independently by the two authors. The categories were compared and discussed until 100% agreement was reached.

Categories

In the previous review on the OS, Bowles2 used eight categories to classify the existing literature. In the present review, these categories were revised to better represent the scope of the recent publications. Relevant articles were classified to one of the five categories based on the article's purpose: (1) analyze client problems; (2) analyze clinical process; (3) analyze client outcomes; (4) advance classification research; and (5) other. Four categories presented in the previous review—namely, ‘explain healthcare resource utilization’, ‘involve students’, ‘report on the Community Nurse Organization project’, and ‘report on unpublished Master's and Doctoral dissertations’— were collapsed into a new category ‘other’ because of the low numbers of these types of publications. Also, the ‘other’ category included non-research publications on the OS describing how the OS might be applied in healthcare practice and research. Finally, one category was renamed to better represent the included literature, namely ‘describe clinical practice’ was changed to ‘analyze clinical process’.

One example that illustrates the current categorization process is an article titled ‘Family home visiting outcomes for mothers with and without intellectual disabilities’,9 which was categorized as ‘analyze client outcomes’ because its main goal was to evaluate the impact of homecare nursing interventions on mothers’ outcomes. Another example is a non-research article titled ‘The OS: coded data that describe patient care’ that was categorized as ‘other’ because its main goal was to describe the structure, aims, and capabilities of the OS for the use by healthcare professionals.10

Methodological quality evaluation

For research manuscripts reporting results of experimental, quasi-experimental, and observational studies, we evaluated the methodological quality using three validated and widely applied tools:

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) criteria11 for randomized controlled trials. CONSORT checklist includes 25 items evaluating the content of the title, abstract, introduction, methods, results, discussion, and other information presented in clinical trials. To construct a methodological quality index, each of the 25 items was given a score of one point if it was fully addressed; half a point if it was partially addressed; and zero points if it was not addressed. For example, the article was given one point if a table showing baseline demographic and clinical characteristics for each group was present in the study Results section (item 15 in the CONSORT checklist11).

Downs and Black's checklist for non-randomized studies.12 Downs and Black's checklist consists of 27 items that relate to the methods and findings of non-randomized studies. To construct a methodological quality index, each of the 27 items was given a score of one point if it was fully addressed; half a point if it was partially addressed; and zero points if it was not addressed. For example, the article was given one point if the characteristics of patients lost to follow-up were fully described (item 9 in Downs and Black's checklist12).

Strengthening the Reporting of Observational studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) criteria13 for observational analytical studies. The STROBE statement consists of a checklist of 22 items, which relate to the title, abstract, introduction, methods, results, and discussion sections of articles. To construct a methodological quality index, each of the 22 items14 was given a score of one point if it was fully addressed; half a point if it was partially addressed; and zero points if it was not addressed. For example, the article was given one point if specific objectives, including any prespecified hypotheses, were fully addressed in the Objectives or Background sections (item 3 in the STROBE checklist14).

Since there is a lack of accepted standardized tools to evaluate the methodological quality of descriptive studies, we modified the STROBE checklist14 to exclude items that were not applicable to descriptive studies. For example, the case–control study specific item (item #6) of the original STROBE checklist, ‘Give the eligibility criteria, and the sources and methods of case ascertainment and control selection and give the rationale for the choice of cases and controls’ was removed since it is not applicable to descriptive studies. Overall, five items of the original STROBE checklist were removed (items 7, 11, 15–17); the final modified STROBE checklist included 17 items. To construct a methodological quality index, each of the 17 items was given a score of one point if it was fully addressed; half a point if it was partially addressed; and zero points if it was not addressed. Higher score indicated higher methodological quality of the reviewed article.

Since some of the included articles were authored by the second author of this review, to avoid conflict of interest, we invited an additional reviewer to validate the methodological quality evaluation. Methodological quality evaluation was performed by the first author and the second reviewer independently. Disagreements were discussed and 100% agreement was achieved on the methodological quality checklists.

Results

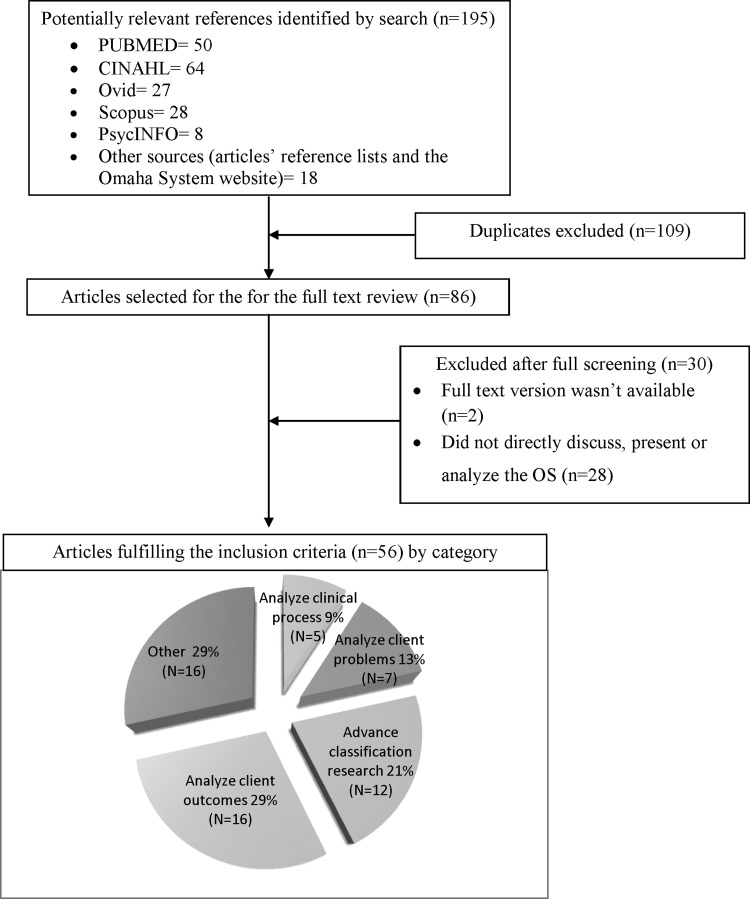

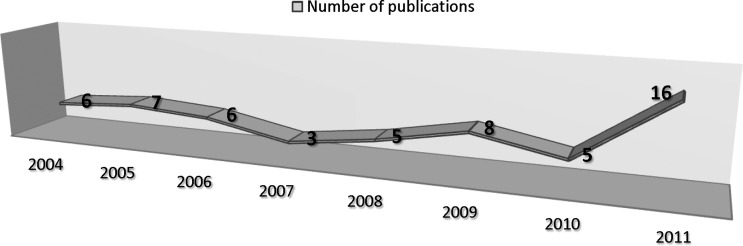

Figure 1 presents the search strategy and results. Overall, 195 articles were found in major biomedical and nursing literature databases using the key words ‘OS’. An additional 18 publications were identified using the articles’ reference lists and the OS website's publications list. Non-duplicated references (n=86) were then hand searched and relevant articles were identified based on the inclusion criteria presented in the methods section. The total number of publications included in this review is 56. Figure 2 represents the time-trends in scientific publications on the OS. It is evident that, in general, the number of publications is increasing over time: the previous review on the use of the OS2 conducted in 2004, included 41 publications over the time period of more than two decades (1982–2003), while this review identified 56 relevant publications over the last 7 years. This is a more than four-fold increase in the average number of articles per year. Moreover, the number of publications grew steadily through the last years, peaking with 16 articles published in 2011.

Figure 1.

Distinct phases in the process of collecting relevant publications on the Omaha System and their results.

Figure 2.

Time-trends in number of publications on the Omaha System.

Figure 1 presents the percentage of articles in each of the five primary categories. As reflected in figure 1, about one third of the publications focused on the analysis of client outcomes (29%). One-fifth of the identified literature analyzed either client problems (13%) or clinical process (9%). Another 21% of the articles were focused on advancing the classification research. The rest of the literature (29%) was categorized as ‘other’ and included literature reviews, practical guidelines on the applications of the OS in community settings, and publications reflecting the importance and growing need for application of standardized terminologies in clinical practice. Table 1 presents the number of articles in each category.

Table 1.

Publications on the Omaha System (OS) by category

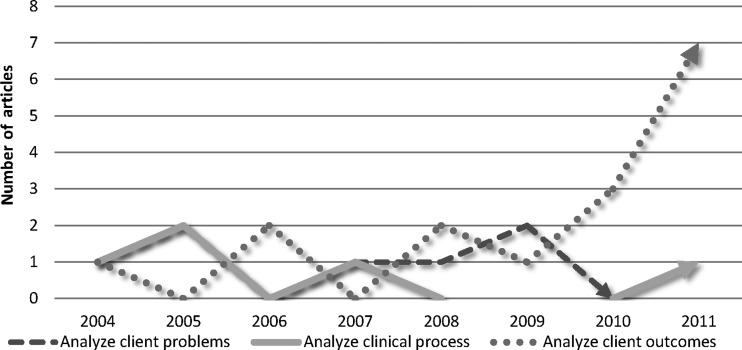

Figure 3 depicts the change in focus of research literature. Over the years, there was an increasing number of articles published that either analyzed client outcomes or advanced classification research. On the other hand, the number of articles that focused on the analysis of clinical processes or the analysis or client problems remained low or decreased during the presented time period.

Figure 3.

Time-trends in articles’ focus.

Additional trends were captured by a detailed article analysis. For example, the first studies that applied data mining techniques to analyze OS data were published in 2008.37 Since then, the use of data and text mining (or machine learning) has steadily grown.28 29 34 37 47 Also, the number of articles focused on patients’ outcomes increased significantly. On the other hand, the number of research projects that involved students remained stable during 2004 to 2006, but since 2007 no publications related to this category were identified.20 40 41 43 64 67 There is significant growth in the number of studies conducted by international authors (N=9, 17% of total number of articles).19 21 23 24 31 35 36 43 46 Additionally, four studies were focused on the interoperability between the electronic records in different settings.42 44 46 49

Four articles were authored by non-nurses (first author),46 48 51 53 while several others (especially studies conducted by the ‘OS Partnership for Knowledge Discovery and Health Care Quality’ at the University of Minnesota) included interdisciplinary co-authors. Most of the papers authored by non-nurses focused on classification research. Only one study was conducted in inpatient settings (medical-surgical unit).53 Finally, seven studies explicitly reported that they used OS coded data from EHRs.23 25 29 30 34 37 38

Methodological quality evaluation

Online supplementary table II presents a short description of the included articles by category. Forty (71%) of the reviewed articles were research studies, however the study designs and methodological approaches varied significantly.

One randomized controlled trial was identified35; its quality was relatively high (21/25 points using the CONSORT11 checklist). We identified one quasi-experimental study31 (non-randomized one-group pre-test and post-test); its methodological quality was intermediate (22.5/27 points using Downs and Black's checklist12). Seven observational studies used correlational design (six of them were in the ‘Analyze client outcomes’ category).9 28–30 37 38 52 The overall methodological quality of these articles was relatively high; using the STROBE criteria,13 the average score was 18/22 (range 17–20). The most common issue was the lack of reporting on what was done to mitigate the effects of missing data (items 12 and 14 in the STROBE checklist). Finally, 31 studies used descriptive design.15–26 32–34 36 39–44 46–48 50 51 53 64 67 The overall methodological quality of these articles was also relatively high; using the modified STROBE criteria, the average score was 14.6/17 (range 12–16.5). The most common issues were the lack of description of the efforts to address potential sources of bias and insufficient or lacking discussion of the limitations of the study (items 9 and 19 in the original STROBE checklist14). Methodological quality scores are presented in online supplementary table II, when relevant.

Discussion

Improving the quality of healthcare and enhancing meaningful use of novel information technologies are complex tasks that require interdisciplinary collaboration of researchers, educators, practitioners, and other stakeholders. This systematic review aimed to describe and analyze recent literature to identify trends and patterns of a scientific inquiry on the OS, one the most frequently used standardized terminologies for the documentation and provision of community healthcare services.

The results of this review indicate that, in general, there is an increasingly growing body of literature on the OS; there is a more than fourfold increase in the average number of articles published each year compared with a previous systematic review on the topic.2 According to the OS website http://www.omahasystem.org, there are currently more than 9000 multidisciplinary practitioners, educators, and researchers using the OS in point-of-care software in the USA and other countries. As shown in figure 2, publications on the OS describe and explain a wide range of healthcare phenomena. About half of the publications on the OS were focused on the analysis of client outcomes (29%), clinical processes (9%), or client problems (13%).

The presentation of the number of articles by primary category (figure 3) on the timescale identified an interesting transition: the number of articles that analyzed client outcomes increased over time, whereas the number of articles analyzing client problems gradually decreased over the last 8 years. This shift was predicted in the previous review on the OS2 and might represent the transition from a basic description of the client's health problems to a more complex understanding of outcomes related to those conditions achieved through healthcare interventions. These trends are also consistent with recent literature indicating that nursing and other healthcare researchers are moving towards analysis of clinical outcomes.69–71 The overall methodological quality of the reviewed studies was relatively high, indicating that OS coded data is currently used to produce robust research findings. One persistent methodological issue identified in observational studies was related to missing data; researchers using the OS coded data should pay more attention to addressing the nature and the quality of missing data in their research projects. Researchers conducting descriptive studies using the OS data should pay more attention to describing their efforts to address potential sources of bias and clearly present the limitations of their studies.

Although the number of articles that primarily focused on the analysis of clinical process remained low during the presented time period, the application of novel statistical methods (such as data mining) enabled OS researchers to start exploring the complex interplay between patient characteristics, clinical process, and outcomes. For example, Monsen et al47 compared deductive and inductive approaches to group nursing interventions in a homecare setting. Deductive approaches included several conventional methods (such as clinical expert consensus, an approach in which clinical expertise guides the identification of meaningful intervention groups) while the inductive approach was based on data mining. Application of the data mining methods helped researchers to group co-occurring interventions inductively based on the existing data. After analyzing a large computerized dataset that included OS data on 2862 patients from 15 homecare agencies, Monsen et al47 concluded that compared to the deductive approaches, the ‘approach based on data mining generated more intervention groups that represented nursing care provided to complex homecare patients’. Afterwards, Monsen et al28 used these intervention grouping approaches to explain hospitalization outcomes for frail and non-frail elders. These examples illustrate novel methodological ways in which OS data might be meaningfully used for the identification of client and process characteristics leading to specific outcomes. More research is needed to explore further opportunities using novel and standard statistical methods to analyze large databases from EHRs.

Classification research on the OS is an additional constantly growing field of research. Classification research is necessary to enhance the validity and applicability, and further develop the OS and integrate it into diverse national and international healthcare environments. The findings of this review indicate that there is a growing body of literature on how to further enhance the semantic structure29 and other aspects of the OS.42 45 47–49 Moreover, several recent authors, focusing on interoperability of the OS across settings and with other standardized terminologies, proposed ways to improve the comprehensive application of the OS.44 46 49 Recommendations suggested by these researchers should guide the future revision of the OS and might serve as a lens to examine other standardized terminologies. Additionally, researchers should pay more attention to translational research that aims to understand the implementation of healthcare research and novel technologies into clinical practice. For example, this review identified no studies on integration of decision support tools based on the OS or OS based EHRs usability testing.

With only few exceptions, most of the publications identified in this review were published on nursing topics and by nurses. Recently, there has been an emerging trend of interdisciplinary collaboration when performing research on the OS. The results of this work are highly important as they produce a platform for healthcare researchers and practitioners to apply diverse research methods or to use different epistemological and philosophical approaches when understanding healthcare services. One example is an interdisciplinary team of researchers based at the University of Minnesota School of Nursing. This group, called ‘OS Partnership for Knowledge Discovery and Health Care Quality’, consists of a diverse group of researchers from nursing, medicine, computer science, and biostatistics. Although relatively new, the group produced a large bulk of recent publications on the OS.26 30 33 34 50–52 More interdisciplinary partnerships like this are needed to further develop the potential of the OS.

The OS can be further developed to meet the needs of diverse clients in different healthcare environments. For example, even though there is evidence of application of the OS in clinical settings other than community and public health,72 this review identified only one publication53 describing OS data in acute care settings. This lacking evidence is critical to further advance the meaningful use of standardized terminologies. Furthermore, the most recent report by the National Academies of Science and Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality73 suggested ways to improve care provided in people's homes by formal and informal caregivers (such as family members). The authors of the report recognized the critical need for research on how health outcomes of homecare patients related to the home environment (especially physical) and different parameters of the informal caregivers (such as the level of stress). This area of research is particularly suitable for the OS researchers because of the focus on home and outpatient environments, but more tools addressing those issues should be developed, validated, and incorporated into the OS. Also, as suggested in the previous OS review,2 the OS might incorporate data that can lead to understanding healthcare expenditures and service costs. This review identified only limited evidence on the development of additional scales/measures/tools that might be incorporated into future revisions of the OS.

The OS is rooted in several theoretical models and might even be considered as an independent conceptual model. Some suggest that in order to explain new phenomena and evidence, theoretical frameworks should be frequently reexamined and, if needed, revised.74 With a growing body of critique of the models that underpin the OS, some of the relations and assumptions underlying the OS should be reevaluated. For example, several authors find difficulties in relating outcomes directly to services and critique the Donabedian framework of structure–process–outcomes (which is one of the theoretical models the OS is rooted in) for its over-simplistic representation of the quality of healthcare.75 76 Presentation of the structure–process–outcomes model in a linear fashion might mis-specify the actual linkages between components of quality that serve as mediators or moderators in the healthcare delivery process.77 Unfortunately, no publications evaluating the theoretical framework of OS were identified in the presented time period.

The OS can be used to structure and analyze the outcomes of nursing education, as presented by Elfrink and Davis,67 that used the OS data to understand the educational needs and progress of their students. Although others also addressed the use of the OS by students,20 41 43 57 64 this review identified no articles on the topic since 2007. As informatics became one of the core competencies that healthcare graduates should have,78 the absence of evidence about the effective educational approaches might hinder the production of comprehensive data from EHRs or even decrease the quality of the care provided. Also, some researchers reported that nurses working with EHRs based on the OS did not use it appropriately and produced large amounts of missing data and duplicate entries.49 51 Unfortunately, very little evidence was identified about what type of education is effective for the users of the OS in real settings. Lack of research in this critical field might hinder the ability of the next generation of healthcare specialists to provide appropriate care and meaningfully use the existing systems.

The OS system has a long history of international adoption and implementation.1 This review identified a significant number of articles (17% of the total number of publications) written by researchers from China, Italy, South Korea, and Turkey.21 36 43 46 These publications represent the adoption of the OS in a global and interdependent world. The trends in publications of international researchers are similar to the general trends presented previously in this review: over time, there is a shift from describing clients’ problems toward outcomes research. Surprisingly, although a significant number of international healthcare providers apply the OS, very little evidence exists on cultural and population tailoring and validation of the OS, even though it was created and tested in the USA. The issue of cultural appropriateness is highly important because the healthcare systems and their clients in other countries might have different sets of problems than those that the OS addresses. For example, Taiwanese authors indicated that because ‘…health concepts of most of Taiwan's older people are rooted in traditional Chinese medicine… Omaha Classification Scheme is less relevant to their health needs’.79 Other standardized terminologies started to develop processes of cultural adaptation. For example, Taiwanese researchers80 have recently described how they used a modified Delphi strategy (using forward translation and expert consensus) to facilitate semantic and cultural translation and validation of the International Classification for Nursing Practice (ICNP). This suggests that more research is needed to effectively translate and validate the concepts of the OS in other countries.

Finally, this review identified a growing body of literature that indicates the applicability of the OS in healthcare settings among diverse populations. For example, OS data were used to describe and analyze the problems and outcomes of elderly persons with and without cognitive impairment in homecare and hospices, pregnant and postpartum women, teenagers and toddlers.15 16 28 Moreover, the OS was applicable to represent and understand the needs of ethnic minorities, such as Latinos20 and Native Americans.18 Further research based on the OS should address healthcare disparities and might be used to represent the needs and voices of other unprivileged populations.

The results of this review suggest that further research is needed in the following areas:

Education: (1) Describe, understand, and identify the effective applications of the OS in healthcare education. (2) Find effective educational approaches for ongoing instruction of healthcare providers that use the OS in practice.

International users: (1) Validate the cultural appropriateness of the OS outside the USA. (2) Conduct international studies using the OS data to compare and analyze health outcomes.

Theoretical framework: (1) Examine and revise, if necessary, theoretical frameworks that underpin the OS. (2) Examine the possibility of including new theoretical models to expand the ability of the OS to describe and explain new healthcare phenomena (eg, outcomes combined with healthcare costs).

Classification research: (1) Examine the need and develop, if necessary, additional scales/measures/tools that might be incorporated into future revisions of the OS (eg, evidence based decision support tools at the point of care). (2) Increase the interoperability of the OS between clinical settings, providers, and other medical terminologies.49 (3) Improve the semantic structure of the OS.48 50 51

Other: (1) Understand factors affecting successful implementation of the OS in real settings (such as organizational and provider characteristics). (2) Analyze the applicability and validity of the OS to represent data needed for comparative effectiveness research, patient-centered outcomes research, and medical home research.

Limitations

Although the search for publications was performed in the largest healthcare databases, it is possible that some of the literature sources were not identified. Furthermore, all the reviewed literature was written in English and publications in other languages were not included. The modified STROBE checklist for methodological quality evaluation was not used or validated in previous studies. We did not evaluate the methodological quality of some of the presented articles since not all the publications presented results of primary research. Also, this review is focused on the OS and conducting comparisons with other standardized terminologies is beyond the scope of this review. Lastly, some of the trends presented in this review might be misidentified because of personal or publication bias.

Conclusion

With the rapid advancements in technology, healthcare systems in the developed and developing countries rely more and more on EHRs to store and analyze clinical data. Therefore, there is a critical need to understand how standardized terminologies might be meaningfully adopted and used in healthcare settings. This systematic review focused on the OS, one of the oldest and most widely used standardized terminologies in community-based care, and identified recent trends that advance its meaningful application in the USA and internationally.

In this review, we presented the most recent ways in which the OS provides comprehensive and high quality information about complex healthcare systems and services, especially when incorporated into EHRs. Analysis of this information has a proven potential to advance our understanding of clinical processes leading to health outcomes in diverse populations. Moreover, the example of the OS illustrates that applying standardized terminologies helps nurses and other healthcare professionals to better represent the impact of their care and further enhances the understanding of their clients’ needs. Due to the non-proprietary nature of the OS, it may be used free of charge by the global healthcare community. Further research on the OS should focus on its applicability in healthcare education, theoretical underpinnings, and international validity. Researchers analyzing the OS data should pay more attention to addressing the nature and the quality of missing data in their publications and clearly present the limitations of their studies.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks are extended to O Jarrín, PhD, RN, Post-Doctoral fellow at the University of Pennsylvania, School of Nursing, for her expertise on issues related to methodological quality assessment.

Footnotes

Contributors: MT and KHB designed the methods, examined the findings, interpreted the results, and wrote the paper. MT and NG carried out the methodological quality evaluation. All authors have attributed to, seen, and approved the manuscript.

Competing interests: KHBauthored several manuscripts included in this review; she did not evaluate the methodological quality of the literature and an additional reviewer was invited.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Martin KS. The Omaha System: a key to practice, documentation, and information management. St Louis, MO: Elsevier Saunders, 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bowles KH. Use of the Omaha Systemin research. In: Martin KS. The Omaha System: a key to practice, documentation, and information management. 2nd edn. St Louis, MO: Elsevier Saunders, 2005:105–33 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weed L. Medical records that guide and teach. N Engl J Med 1968;278:652–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Martin KS, Scheet NJ. The Omaha System: applications for community health nursing. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders, 1992 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Donabedian A. Evaluating the quality of medical care. Milbank Memorial Bank Q 1966;44:166–206 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Neuman B, Fawcett J. The Neuman systems model. 5th edn. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Finkelman AW. Problem-solving, decision-making, and critical thinking: how do they mix and why bother? Home Care Provid 2001;6:194–7; quiz 198–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lunney M. Critical thinking and accuracy of nurses’ diagnoses. Part I: risk of low accuracy diagnoses and new views of critical thinking. Rev Esc Enferm USP 2003;37:17–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Monsen KA, Sanders A, Yu F, et al. Family home visiting outcomes for mothers with and without intellectual disabilities. J Intellect Disabil Res 2011;55:484–99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garvin JH, Martin KS, Stassen DL, et al. The Omaha System. Coded data that describe patient care. J AHIMA 2008;79:44–9; quiz 51–2 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schulz K, Altman D, Moher D. CONSORT 2010 Statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMJ 2010;340:c332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Downs SH, Black N. The feasibility of creating a checklist for the assessment of the methodological quality both of randomised and non-randomised studies of health care interventions. J Epidemiol Community Health 1998;52:377–84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. BMJ 2007;335:806–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vandenbroucke JP, von Elm E, Altman D, et al. Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE): explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med 2007;4:e297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Caley LM, Winkelman T, Mariano K. Problems expressed by caregivers of children with fetal alcohol spectrum disorder. Int J Nurs Terminol Classif 2009;20:181–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weiss M, Fawcett J, Aber C. Adaptation, postpartum concerns, and learning needs in the first two weeks after caesarean birth. J Clin Nurs 2009;18:2938–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brooten D, Youngblut JM, Donahue D, et al. Women with high-risk pregnancies, problems, and APN interventions. J Nurs Scholarsh 2007;39:349–57 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Neff DF, Kinion ES, Cardina C. Nurse managed center: access to primary health care for urban Native Americans. J Community Health Nurs 2007;24:19–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wong FKY, Liu CF, Szeto Y, et al. Health problems encountered by dying patients receiving palliative home care until death. Cancer Nurs 2004;27:244–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McEwen MM, Slack MK. Factors associated with health-related behaviors in Latinos with or at risk of diabetes. Hispanic Healthc Int 2005;3:143–52 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yoo IY, Cho WJ, Chae SM, et al. Community health service needs assessment in Korea using OMAHA Classification System. Int J Nurs Stud 2004;41:697–702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marek KD, Jenkins ML, Stringer M, et al. Classifying perinatal advanced practice data with the Omaha System. Home Health Care Manag Pract 2004;16:214–21 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lu K.PhD dissertation. Columbia, South Carolina: University of South Carolina Press, 2005. Health problems and nursing interventions records of elderly with hypertension, high blood sugar, and high cholesterol levels in Taiwan.

- 24.Erci B. Global case management: impact of case management on client outcomes. Lippincotts Case Manag 2005;10:32–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hong WHS. Evidence-based nursing practice for health promotion in adults with hypertension in primary health care settings. Milwaukee, WI: The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Monsen KA, Newsom ET. Feasibility of using the Omaha System to represent public health nurse manager interventions. Public Health Nurs 2011;28:421–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Resick LK, Leonardo ME, McGinnis KA, et al. A retrospective data analysis of two academic nurse-managed wellness center sites. J Gerontol Nurs 2011;37:42–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Monsen KA, Westra BL, Oancea SC, et al. Linking home care interventions and hospitalization outcomes for frail and non-frail elderly patients. Res Nurs Health 2011;34:160–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Westra BL, Savik K, Oancea C, et al. Predicting improvement in urinary and bowel incontinence for home health patients using electronic health record data. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2011;38:77–87 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Monsen KA, Radosevich DM, Kerr MJ, et al. Public health nurses tailor interventions for families at risk. Public Health Nurs 2011;28:119–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Erci B. The effectiveness of the Omaha System intervention on the women's health promotion lifestyle profile and quality of life. J Adv Nurs 2011;68:898–907 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.O'Sullivan CK, Bowles KH, Jeon S, et al. Psychological distress during ovarian cancer treatment: improving quality by examining patient problems and advanced practice nursing interventions. Nurs Res Pract 2011;2011:351642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Monsen KA, Fulkerson JA, Lytton AB, et al. Comparing maternal child health problems and outcomes across public health nursing agencies. Matern Child Health J 2010;14:412–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Monsen KA, Banerjee A, Das P. Discovering client and intervention patterns in home visiting data. West J Nurs Res 2010;32:1031–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wong FKY, Chow SKY, Chan TMF. Evaluation of a nurse-led disease management programme for chronic kidney disease: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Nurs Stud 2010;47:268–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chow SKY, Wong FKY, Chan TMF, et al. Community nursing services for postdischarge chronically ill patients. J Clin Nurs 2008;17:260–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Choromanski L, Westra B, Oancea C, et al. Predictive modeling for improving incontinence and pressure ulcers in homecare patients. AMIA Annu Symp Proc 2008;2:908. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yu F, Lang NM. Using the Omaha system to examine outpatient rehabilitation problems, interventions, and outcomes between clients with and without cognitive impairment. Rehabil Nurs 2008;33:124–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Westra BL, Solomon D, Ashley DM. Use of the Omaha System data to validate Medicare required outcomes in home care. J Healthc Inf Manag 2006;20:88–94 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Connolly PM, Mao C, Yoder M, et al. Evaluation of the Omaha System in an academic Nurse Managed Center. Online J Nurs Inform 2006;10 [Google Scholar]

- 41.Barton AJ, Clark L, Baramee J. Tracking outcomes in community-based care. Home Health Care Manag Pract 2004;16:171–6 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Choi J, Jenkins M, Cimino J, et al. Toward semantic interoperability in home health care: formally representing OASIS items for integration into a concept-oriented terminology. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2005;12:410–17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Erdogan S, Esin NM. The Turkish version of the Omaha System: its use in practice-based family nursing education. Nurse Educ Today 2006;26:396–402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Orlygsdottir B. Use of NIDSEC-compliant CIS in community-based nursing-directed prenatal care to determine support of nursing minimum data set objectives. Comput Inform Nurs 2007;25:283–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Anderson CA, Keenan G, Jones J. Using bibliometrics to support your selection of a nursing terminology set. Comput Inform Nurs 2009;27:82–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vittorini P, Tarquinio A, di Orio F. XML technologies for the Omaha System: a data model, a Java tool and several case studies supporting home healthcare. Comput Methods Programs Biomed 2009;93:297–312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Monsen KA, Westra BL, Yu F, et al. Data management for intervention effectiveness research: comparing deductive and inductive approaches. Res Nurs Health 2009;32:647–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Melton GB, Westra BL, Raman N, et al. Informing standard development and understanding user needs with Omaha system signs and symptoms text entries in community-based care settings. AMIA Annu Symp Proc 2010;2010:512–16 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Westra BL, Oancea C, Savik K, et al. The feasibility of integrating the Omaha System data across home care agencies and vendors. Comput Inform Nurs 2010;28:162–71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Monsen KA, Melton-Meaux G, Timm J, et al. An empiric analysis of Omaha System targets. Appl Clin Inform 2011;2:317–30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Farri O, Monsen KA, Westra BL, et al. Analysis of free text with Omaha System targets in community-based care to inform practice and terminology development. Appl Clin Inform 2011;2:304–16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Monsen KA, Farri O, McNaughton DB, et al. Problem stabilization: a metric for problem improvement in home visiting clients. Appl Clin Inform 2011;2:437–46 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhang Y, Monsen KA, Adam TJ, et al. Systematic refinement of a health information technology time and motion workflow instrument for inpatient nursing care using a standardized interface terminology. AMIA Annu Symp Proc 2011;2011:1621–9 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Conrad D, Schneider J. Enhancing the visibility of NP practice in electronic health records. J Nurse Pract 2011;7:832–8 [Google Scholar]

- 55.Martin KS, Monsen KA. 2011 Omaha System international conference. Cin Comput Inform Nurs 2011;29:430–0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bowles KH. Achieving meaningful use with standardized data. Online J Nurs Inform 2011;15:3p [Google Scholar]

- 57.Martin KS, Monsen KA, Bowles KH. The Omaha system and meaningful use: applications for practice, education, and research. Comput Inform Nurs 2011;29:52–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Monsen KA, Martin KS, Christensen JR, et al. Omaha System data: methods for research and program evaluation. Stud Health Technol Inform 2009;146:783–4 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Correll PJ, Martin KS. The Omaha System helps a public health nursing organization find its voice. Comput Inform Nurs 2009;27:12–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Canham D, Mao CL, Yoder M, et al. The Omaha System and quality measurement in academic nurse-managed centers: ten steps for implementation. J Nurs Educ 2008;47:105–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bowles KH, Martin KS. Three decades of Omaha System research: providing the map to discover new directions. Stud Health Technol Inform 2006;122:994. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Martin KS, Elfrink VL, Monsen KA, et al. Introducing standardized terminologies to nurses: magic wands and other strategies. Stud Health Technol Inform 2006;122:596–9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Monsen KA, Fitzsimmons LL, Lescenski BA, et al. A public health nursing informatics data-and-practice quality project. Comput Inform Nurs 2006;24:152–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Plowfield LA, Hayes ER, Hall-Long B. Using the Omaha system to document the wellness needs of the elderly. Nurs Clin North Am 2005;40:817–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Chambers M. A new primary care electronic record. What's in it for you?. Community Pract 2005;78:426–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Leonardo ME, Resick LK, Bingman CA, et al. The alternatives for wellness centers: drown in data or develop a reasonable electronic documentation system. Home Health Care Manag Pract 2004;16:177–84 [Google Scholar]

- 67.Elfrink VL, Davis LS. Using Omaha system data to improve the clinical education experiences of nursing students: the University of Cincinnati project. Home Health Care Manag Pract 2004;16:185–91 [Google Scholar]

- 68.Monsen KA, Kerr MJ. Mining quality documentation data for golden outcomes. Home Health Care Manag Pract 2004;16:192–9 [Google Scholar]

- 69.Scholes J. Research in nursing in critical care 1995–2009: a cause for celebration. Nurs Crit Care 2010;15:20–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Saranto K, Kinnunen UM. Evaluating nursing documentation—research designs and methods: systematic review. J Adv Nurs 2009;65:464–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kane RL, Radosevich DM. Conducting health outcomes research. Burlington, MA: Jones & Bartlett Publishers, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 72.Omaha System Omaha System Overview 2011. http://www.omahasystem.org (accessed 10-7-2011).

- 73.National Research Council Health care comes home: the human factors. Washington, DC: Committee on the Role of Human Factors in Home Health Care, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 74.Meleis A. Theoretical nursing: development and progress. 4th edn. Philadelphia: Lippincott, 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 75.Salzer M. Quality as relationship between structure, process, and outcome: a conceptual framework for evaluating quality. Expanding the Research Base—Proceedings of the Annual Research Conference; 1996 [Google Scholar]

- 76.McDonald KM, Sundaram V, Bravata DM, et al. Closing the quality gap a critical analysis of quality improvement strategies. Tech Rev, Stanford-UCSF Evid Based Pract Center 2007;4:51–7 [Google Scholar]

- 77.Unruh L, Wan TTH. A systems framework for evaluating nursing care quality in nursing homes. J Med Syst 2004;28:197–214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Greiner AC, Knebel E. Health professions education: a bridge to quality. Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2003 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Shih SN, Gau ML, Tsai JC, et al. A Health Need Satisfaction Instrument for Taiwan's single-living older people with chronic disease in the community. J Clin Nurs 2008;17:67–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hou IC, Chang P, Chan HY, et al. A modified Delphi translation strategy and challenges of International Classification for Nursing Practice (ICNP). Int J Med Inform 2012;82:418–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]