Abstract

We assessed trajectories of children's internalizing symptoms, indexed through anxiety and depression, with a focus on the role of interactions between interparental marital conflict, children's sympathetic nervous system activity indexed by skin conductance level (SCL), and parasympathetic nervous system activity indexed by respiratory sinus arrhythmia (RSA) as predictors of growth. Children participated in 3 waves of data collection with a 1-year lag between each wave. At T1, 128 girls and 123 boys participated (M age = 8.23 years; SD = 0.73). The most important findings reveal that girls with either low RSA in conjunction with low SCL (i.e., coinhibition) at baseline or with increasing RSA and decreasing SCL in response to a challenging task (i.e., reciprocal parasympathetic activation) are susceptible to high or escalating anxiety and depression symptoms, particularly in the context of marital conflict. Findings support the importance of concurrent examinations of environmental risk factors and physiological activity for better prediction of the development of anxiety and depression symptoms.

Keywords: marital conflict, skin conductance, respiratory sinus arrhythmia, depression, anxiety

Internalizing symptoms, including feelings of anxiety and depression (our two indices of internalizing symptoms), involve significant distress and can interfere with concurrent and long-term social and psychological adjustment (Caspi, Bem, & Elder, 1989). The development of internalizing symptoms in late childhood may set the stage for more significant problems in early adolescence, when internalizing symptoms and disorders increase, especially among girls (Barber & Olson, 2004; Graber, 2004; Graber & Sontag, 2009; Twenge & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2002). However, risk factors for escalating anxiety and depression symptoms in middle to late childhood are not well understood.

Converging environmental and individual vulnerabilities likely contribute to the development of internalizing symptoms in childhood (see Ingram & Luxton, 2005). One well-established environmental risk factor for symptoms of anxiety and depression is exposure to parental marital conflict (for reviews, see Cummings & Davies, 2002; Repetti, Taylor, & Seeman, 2002; Zahn-Waxler, Race, & Duggal, 2005). Marital conflict has been linked with children's anxiety and depression symptoms in numerous cross-sectional and longitudinal studies, across types of measures and informants (e.g., Cummings & Davies, 2010; El-Sheikh, Keller, & Erath, 2007; Shelton & Harold, 2008). Mechanisms linking marital conflict and children's internalizing symptoms include emotional insecurity, indicated by emotional and behavioral reactivity and negative representation of the marital relationship (Cummings & Davies, 2010); negative cognitive representations about marital conflict, including attributions of threat and self-blame (Grych & Fincham, 1990); and spillover of negative feelings and behaviors into the parent–child relationship (Erel & Burman, 1995).

Among individual vulnerabilities, recent conceptual and empirical work suggest that certain profiles of parasympathetic (PNS) and sympathetic (SNS) nervous system activity may increase or decrease vulnerability to psychopathology, including internalizing problems (Beauchaine, 2001; Porges, 2007). Respiratory sinus arrhythmia (RSA) and skin conductance level (SCL), in particular, have moderated the association between marital conflict and internalizing symptoms in prior research (El-Sheikh & Erath, 2011).

In this study, we employed growth curve modeling to examine whether interactions between RSA and SCL confer protection against or vulnerability to increasing internalizing symptoms from ages 8–10 years in the context of marital conflict. Methodologically, Cole et al. (2002) contend that such “dynamic assessment” is likely more reliable than approaches that simply control for prior levels of internalizing symptoms. Conceptually, identifying the progression of internalizing symptoms is likely a better indicator of subsequent maladjustment than symptoms at a single time point (see Graber, 2004, p. 595). Indeed, internalizing problems in early adolescence may not reflect new disorders arising but, rather, the exacerbation or continued development of internalizing symptoms from childhood (see Bandura, 1964; Ingram & Luxton, 2005).

In the current study, we tested whether interactions among marital conflict, RSA, and SCL differentially predict internalizing symptoms depending on child sex (see Bell, Foster, & Mash, 2005). Girls face higher risk for anxiety and depression throughout adolescence (see Weissman et al., 1996; Zahn-Waxler et al., 2005), but evidence for sex differences during childhood is sparse (Cole et al., 2002; Crawford, Cohen, Midlarsky, & Brook, 2001; Graber, 2004; Zahn-Waxler et al., 2005). Although girls and boys may report similar levels of internalizing symptoms during childhood, individual or environmental factors that produce greater risk in a subset of boys or girls are poorly understood. Crawford et al. (2001), for example, suggested that girls may be more vulnerable to marital conflict because it is a “network event” (i.e., an event occurring within an individual's social network) to which girls may be more attuned (Kessler & McLeod, 1984).

The Autonomic Nervous System and Internalizing Problems

The autonomic nervous system (ANS) is composed of the PNS and SNS branches, which generally perform opposing functions. The PNS facilitates “rest and digest” functions, decelerates heart rate and may support social engagement via its overlap with neural networks that govern facial orienting, facial expressions, vocalizations, and listening (Porges, 2007). RSA is a well-validated and commonly used measure of PNS activity (Grossman & Taylor, 2007). In community samples, higher RSA in normal (i.e., safe) conditions and moderate reductions in RSA (i.e., withdrawal of PNS influence) in challenging or threatening conditions are conceptualized as adaptive and linked with various indices of social and emotional competence (Porges, 2007), although excessive reductions in RSA may be linked with anxiety (Beauchaine, 2001; Gazelle & Druhen, 2009).

The SNS, on the other hand, fosters mobilization (i.e., the “fight or flight” response), promoting vigilance, increasing heart rate, and sweat gland secretion, while simultaneously decreasing activity of systems unrelated to mobilization. Activation of the SNS and deactivation of the PNS in threatening situations is considered adaptive, as this response enables individuals to attend and respond to potentially threatening cues. Although typically adaptive in the face of danger, frequent or extreme SNS activation is metabolically costly and may lead to wear and tear on the body (McEwen, 1998). SCL is a well-validated and commonly used measure of SNS activity. Moderate baseline SCL in normal situations and moderate SCL increases in threatening situations is generally considered adaptive.

Internalizing symptoms have been associated separately with lower baseline RSA (Dietrich et al., 2007) and greater SCL reactivity (Weems, Zakem, Costa, Cannon, & Watts, 2005). Furthermore, higher baseline RSA and reductions in RSA during stress may protect children against internalizing (and externalizing) problems in the context of marital conflict (El-Sheikh, Harger, & Whitson, 2001; El-Sheikh & Whitson, 2006; Katz & Gottman, 1995, 1997). In studies that examined SCL reactivity to stressors (SCL-R) as a moderator of marital conflict, higher SCL-R operated as a vulnerability factor for internalizing symptoms among girls but not among boys (El-Sheikh, 2005; El-Sheikh et al., 2007).

Both SCL and RSA have been useful as predictors of child adjustment and as moderators of child maladjustment in the context of marital conflict (El-Sheikh et al., 2001; El-Sheikh et al., 2007). However, the specificity of hypotheses that can be drawn on the basis of much of this research has been limited to predicting positive or negative outcomes in association with the activity of each ANS branch separately (Beauchaine, 2001). Increasingly, research suggests that it may be important to consider the synergistic effects of PNS and SNS activity on psychological functioning (El-Sheikh et al., 2009). For example, Beauchaine (2001) explained that low RSA is linked with a range of negative child outcomes, including internalizing and externalizing problems; to predict whether low RSA will manifest as an externalizing or internalizing problem, considering the SNS can be informative because the SNS (measured by SCL) is linked with the neural network that governs behavioral inhibition. Considering both branches may allow for more specific and sophisticated understanding of children's adaptation in relation to ANS activity and family risk.

Drawing from multisystem psychophysiological models (e.g., Beauchaine, 2001; Berntson, Cacioppo, & Quigley, 1991; Porges, 2007), El-Sheikh et al. (2009) tested interactions among exposure to marital conflict and children's RSA and SCL as concurrent predictors of their externalizing behavior. Analyses revealed that coinhibition (low SCL and low RSA) and coactivation (high SCL and high RSA) operated as vulnerability factors for externalizing behavior in the context of marital conflict. In contrast, reciprocal parasympathetic activation (low SCL and high RSA) and reciprocal sympathetic activation (high SCL and low RSA) operated as protective factors. Gordis, Feres, Olezeski, Rabkin, and Trickett (2010) also reported that coinhibition and coactivation, measured with RSA and SCL, operated as vulnerability factors for aggressive behavior among girls in the context of child maltreatment. Notably, as in the current study, interactions between indices of the SNS and PNS in El-Sheikh et al. (2009) and Gordis et al. (2010) were informed by the autonomic space model (Berntson et al., 1991) but diverged from the autonomic space model by examining SCL rather than SNS-linked cardiac activity (e.g., cardiac preejection period).

The Present Study: Marital Conflict × RSA × SCL

In the present study, we expand on earlier research, by examining interactions among marital conflict, SCL, and RSA as predictors of internalizing symptoms across three waves of assessment from middle to late childhood. Given the common comorbidity of internalizing and externalizing problems in childhood, as well as partially overlapping risk factors (Keiley, Loft-house, Bates, Dodge, & Pettit, 2003), we expect that the predictors of internalizing problems may be similar to the predictors of externalizing problems documented in prior research on interactions between family conflict, RSA, and SCL (El-Sheikh et al., 2009; Gordis et al., 2010). More specifically, we hypothesize that either a profile of low RSA and low SCL (coinhibition) or a profile of high RSA and high SCL (coactivation) will operate as a vulnerability factor for high and increasing internalizing symptoms in the context of marital conflict. We anticipate that these profiles (coinhibition or coactivation) will operate as vulnerability factors based on baseline or reactivity measures of RSA and SCL (El-Sheikh et al., 2009; Gordis et al., 2010).

Sex differences in autonomic correlates of child psychological adjustment are often found (Beauchaine, 2009). Although this hypothesis is relatively tentative, we expect that the vulnerability function of coinhibition or coactivation may be exacerbated among girls (see Gordis et al., 2010), who exhibit a greater increase in internalizing symptoms around the transition to adolescence, compared with boys (Hankin & Abramson, 2001). Different autonomic correlates of anxiety and depression have been proposed but empirical evidence remains equivocal (Beauchaine, 2001; Greaves-Lord et al., 2007); thus, we examine anxiety and depression as separate outcomes but do not specify different hypotheses.

Method

Participants

Children and their parents participated in three waves of data collection, with a 1-year interval between each wave. At T1, 128 girls and 123 boys participated; average age was 8.23 years (SD = 0.72). The majority of children were classified as prepubertal (M = 1.39, SD = 0.33), based on mothers’ reports on the Pubertal Development Scale (Petersen, Crockett, Richards, & Boxer, 1988). Children were recruited through public school systems located in the southeastern United States. Using telephone numbers provided by schools, we contacted families. To reduce potential confounds, children with diagnosed disorders of ADHD, learning disabilities, or mental retardation were not eligible to participate; mothers reported on these diagnoses. To further reduce potential confounds, children had to have lived with the two participating parents for two or more years to be eligible for participation. Specifically, 73% of children lived with their biological mother and father, 24% lived with a mother and a partner (e.g., mother's boyfriend or stepfather of child), and the remaining 3% lived mostly with their biological father and a stepmother; the two parents with whom the child resided lived together for an average of 10 years (SD = 5.67 years).1

Sampling procedures were structured to include European American and African American families across a wide range of socioeconomic levels, and median family income was in the $35,000–$50,000 range. Most parents had completed high school (76%), with almost half (45%) having graduated from college. Mirroring the demographics of the community, 64% of participants were European American and 36% were African American. Socioeconomic status (SES) was based on the Hollingshead (1975) criteria ranging from Level 1 (e.g., unskilled workers) to Level 5 (e.g., professional). Families represented the complete spectrum of SES backgrounds (M = 3.21, SD = 0.91).

Retention rates over the 3 years were relatively high given the diverse nature of the sample in terms of ethnicity and economic background. Of children who participated at T1, 86% participated at T2 (M age = 9.3 years, SD = 0.79). Of those who participated at T2, 87% participated at T3. The overall retention rate (Time 1–3) was 75%. Reasons for attrition included moving out of the study area, declining to participate because of busy schedules, and failing to respond to phone and letter requests to participate. No significant differences existed between those who dropped out and those who did not on any of the study variables.

Procedures and Measures

This study is based on a component of a larger longitudinal investigation and only pertinent procedures are discussed. Whereas several publications have stemmed from this large and rich data set, the research questions addressed in this article are novel and make a unique contribution to the literature. The study was approved by the University's Institutional Review Board; consent and assent for participation were obtained from parents and children, respectively, during each study wave. Unless otherwise noted, all procedures and measures were identical at each wave of data collection. Data were collected at a university research laboratory, where all participants (children, mothers, and fathers) visited during the same session. Mothers and fathers completed questionnaires in separate lab rooms. In another room, the child participated in a psychophysiological assessment session and completed questionnaires via verbal interview with a research assistant.

Children's physiological responses (i.e., RSA and SCL) were measured during resting conditions (baseline assessments) and in the context of a star-tracing task. For brevity, baseline RSA and SCL are referred to as RSA-B and SCL-B, respectively; RSA and SCL reactivity are referred to as RSA-R and SCL-R, respectively. The star-tracing task is a well-established, cognitively challenging stressor (Lafayette Instrument Company, Mirror Tracer) that typically induces RSA (El-Sheikh, 2005) and SCL reactivity (El-Sheikh, 2005; El-Sheikh et al., 2007). Further, children's physiological responses during this task have been associated with marital conflict and child internalizing and externalizing problems (El-Sheikh et al., 2007).

Because physiological data collection was often novel to the child and family, steps were taken to reduce parent and child anxiety. Parents were present while the electrodes were attached (for more detail about the procedures, refer to El-Sheikh, Keiley, & Hinnant, 2010). After the researcher and parent departed the room, a 6-min adaptation period followed during which the child was asked to sit quietly. Then a 3-min baseline assessment followed while the child was seated and asked to be quiet. Following the baseline, children engaged in the star-tracing task for 3 min (these procedures are described in more detail in El-Sheikh et al., 2009).

RSA data acquisition and reduction

Following standard guidelines (Berntson et al., 1991), RSA was assessed by placing one electrocardiography (ECG) electrode on the center of the child's chest to ground the signal while two electrodes were placed on each rib cage about 10–15 cm below the armpits. A pneumatic bellows was placed around the child's chest and fastened with a beaded chain to measure respiratory changes (chest expansion and compression during breathing). A custom bioamplifier from SA Instruments (San Diego, CA) was used during data collection, and the signal was digitized with the Snap-Master Data Acquisition System (HEM Corporation, Southfield, MI) at a sampling rate of 1,000 readings per second. To examine ECG, the bioamplifier was set for bandpass filtering with half power cutoff frequencies of 0.1 and 1,000 Hz, and the signal was amplified with a gain of 500. The ECG signal was processed using the Interbeat Interval (IBI) Analysis System (James Long Company, Caroga Lake, NY). A pressure transducer with a bandpass of DC to 4,000 Hz was used with the bellows to minimize phase or time shifts in the measurement of respiration.

The rhythmic fluctuations in heart rate that are accompanied by phases of the respiratory cycle were used to calculate RSA (Grossman, Karemaker, & Wieling, 1991). RSA was determined by the peak-to-valley method, and all the units were in seconds; this methodology has been validated for the quantification of RSA (Berntson et al., 1997). RSA was computed by using the difference in IBI readings from inspiration to expiration onset.

SCL data acquisition

SCL was measured by attaching two Ag-AgCl skin conductance electrodes (filled with BioGel, an isotonic NaCl electrolyte gel) to the volar surfaces of the distal phalanges of the second and third fingers of the child's non-dominant hand (Scerbo, Freedman, Raine, Dawson, & Venables, 1992). Double-sided adhesive collars with a 1-cm hole were placed on each finger to control the area of gel contact, and a constant sinusoidal voltage (i.e., 0.5 V/ms) was used. The signals were digitized and amplified using a 16 channel A/D converter (bio amplifier Model MME-4; James Long Company, Caroga Lake, NY), and SCL was computed using the James Long Company Software. SCL is expressed in microSiemens (μS). Seven participants were eliminated from the current analyses because of abnormally high baseline SCL levels (>4 standard deviations from the mean). These high baseline levels are likely due to SCL assessment problems (i.e., SCL electrode problems).

Marital conflict

At T1, the Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS2; Straus, Hamby, Boney-McCoy, & Sugarman, 1996) was used to measure verbal/psychological and physical aggression. Rather than relying on a spouse's reports of their own aggression (which is likely downwardly biased), mothers’ report of aggression perpetrated against them by fathers and fathers’ report of aggression perpetrated against them by mothers were used for analyses (e.g., Ehrensaft & Vivian, 1996). The CTS2 is frequently used and has well-established reliability and validity (Straus et al., 1996). At T1, internal consistency for this measure was .88 for mothers and .92 for fathers. Based on at least one partner's report, 29% of families experienced marital physical aggression within the past year. Of those experiencing such aggression, 16% reported a resulting injury. Averaging mother and father reports, the mean verbal/psychological aggression was 13.15 (SD = 7.32), indicating a wide range in the sample.

The children also reported on interparental conflicts via the Destructive Conflict scale of the Children's Perceptions of Interparental Conflict Scale (CPIC; Grych, Seid, & Fincham, 1992). This is a 19-item scale designed to assess child perceptions of the frequency, intensity, and resolution of marital conflict, with higher scores indicating more frequent and intense conflict that is not well resolved. Children reported a wide range of parental marital conflict (M = 13.67, SD = 7.03). The CPIC has demonstrated good internal consistency and test–retest reliability and is considered appropriate for school-aged children (Grych et al., 1992). Internal consistency in this study was .82 at T1.

Mother, father, and child reports of marital conflict were all significantly correlated (rs ranged from .27 to .28). To reduce the number of analyses and likelihood of Type I error, parent reports on the CTS and child reports on the CPIC were standardized and summed to create a marital conflict composite score.2

Child internalizing symptoms

Children's depression and anxiety symptoms were measured by the Trauma Symptoms Checklist for Children (TSCC; Briere, 1996), administered to all children via interview during the three waves of assessment. Because of their more private nature, children's reports of internalizing symptoms are reliable indicators of the construct (Angold, 1988; see also Ialongo, Edelsohn, Werthamer-Larsson, Crockett, & Kellam, 1995). The TSCC has high internal consistency across normative and clinical samples (e.g., Elliott & Briere, 1994; Lanktree & Briere, 1995) and is convergent with children's reports on widely used measures of anxiety and depression in normative samples (El-Sheikh, Cummings, Kouros, Elmore-Staton, & Buckhalt, 2008; Ozer, 2005). This questionnaire contains several sub-scales designed to examine several symptom domains; depression and anxiety were pertinent. The depression subscale is composed of nine items including “feeling lonely,” and “feeling sad or unhappy.” The anxiety subscale is composed of nine items including “feeling afraid something bad might happen.” Children rate how often they experience each item on a scale from 0 (never) to 3 (almost all of the time). Mean scores on depression and anxiety subscales in the current sample are consistent with mean scores in large, normative samples (Briere, 1996). In this sample during T1, the internal consistency was .73 for depression symptoms and .74 for anxiety.

Analysis Plan

Following guidelines established for growth modeling (Singer & Willet, 2003), we fit two separate unconditional linear growth models with the measures of depression or anxiety at ages 8, 9, and 10 as the observed variables. For both unconditional models, time was centered at age 10 because we were interested in how our predictors explained change in trajectories of depression and anxiety (slope), as well as how they indicated levels of children's anxiety and depression at age 10 (intercept); that is, latent slope regression parameters were fixed at –2, –1, and 0. The latent intercept is therefore interpreted as the mean value of depression or anxiety symptoms at age 10. Because we only had 3 time points, a quadratic model was not tested (Singer & Willett, 2003, p. 217).

After determining that significant individual differences existed in the growth parameters of the two domains (anxiety, depression), predictors were added one at a time to the unconditional models to answer our overarching question about the coordination of boys’ and girls’ PNS and SNS functioning in the context of parents’ marital conflict. The significance of each predictor's effect on the growth parameters (separately or together) was determined by fitting a reduced model and conducting a chi-square test (Keiley, Martin, Liu, & Dolbin-MacNab, 2005; Singer & Willett, 2003). We used the conventional level of alpha (.05) in our chi-square tests, except in testing the significance of four-way interactions (described below). Because our study is breaking new ground and our models are quite complex with four-way interactions, which require increased power, we relaxed the alpha level to .10 when adding those interactions (Lipsey, 1998).

For the two domains of depression or anxiety, we fit two separate series of conditional models. We first added the main effect of sex and marital conflict to each model. We then added two different sets of main effects, two-way interactions, three-way interactions, and a final four-way interaction to answer two different questions in each of the domains (depression, anxiety). With the first set of main effects and interactions, we investigated the question of whether the effects of sex and marital conflict on depression or anxiety were different depending on the baseline levels of PNS (RSA-B) and SNS (SCL-B) activity; that is, we ultimately added a four-way interaction between sex, marital conflict, RSA-B, and SCL-B (referred to as “Baseline × Baseline” models). With the second set of main effects and interactions, we investigated the question of whether the effects of sex and marital conflict on depression or anxiety symptoms were different depending on the reactivity levels of PNS (RSA-R) and SNS (SCL-R) activity; that is, we ultimately added a four-way interaction between sex, marital conflict, RSA-R, and SCL-R (referred to as “Reactivity × Reactivity” models). For the Reactivity × Reactivity models, when RSA or SCL were added, their baseline and reactivity scores were entered simultaneously. Thus, analyses of reactivity control for baseline levels in accord with the law of initial values, which proposes that reactivity levels are influenced by baseline levels of physiological arousal (Wilder, 1967). For the Baseline × Baseline models, this was not necessary. Because we were interested in concurrent coordination across these systems, we focused on the same measures (baseline or reactivity) across systems, rather than Baseline × Reactivity interactions. In addition, because of our substantive interest and the complexity of the models, the four-way interactions were allowed to predict only one growth parameter at a time in each domain.

In the final step for each conditional model in the two domains described above (depression and anxiety), demographic and individual differences (SES, child body mass index [BMI], and child race) variables that are commonly linked with either marital conflict, ANS activity, or internalizing symptoms were entered as a block; child height and weight were measured in the lab to compute BMI, based on Must, Dallal, and Dietz's (1991) criteria. Because of the paucity of research of the type we are presenting, we added our major predictors first, then tested whether these findings disappeared when we then controlled for the demographics used in our analyses. This is a common procedure in testing models for innovative research areas (Singer & Willett, 2003). If a demographic variable did not significantly predict the growth parameters (based on the Wald chi-square for that variable) it was, for the sake of parsimony, removed from the model (Keiley et al., 2005). The fit of these growth models was assessed using the chi-square statistic, the comparative fit index (CFI), the Tucker–Lewis index (TLI), and the root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA). Hu and Bentler (1999) suggested that a well-fitting model has a CFI or TLI greater than .95 and an RMSEA less than .06. Aside from these fit indices, Singer and Willett (2003) suggested that the R2 statistics and the residual variances be used, when possible, to quantify the “correspondence between the fitted model and sample data” (p. 47). Thus, these statistics are also reported.

Mplus (Version 5.2), which manages missing data using a full information maximum likelihood method (FIML; B. O. Muthén & Muthén, 2007), was used to fit the models. FIML has been found to be superior to other common methods of handling missing data (e.g., listwise deletion, pattern response imputation; see Enders & Bandalos, 2001). For measures of depression and anxiety symptoms, the percentage of missing data ranged from 1% (age 8) to 27% (age 10). The percentage of missing data for the predictors (all collected at age 8) ranged from 0% to 6%. In the covariance coverage matrix (a matrix of missingness for all pairs of variables), the highest percentage of missing data was 32%, well within acceptable limits (less than 90% is recommended; L. K. Muthén & Muthén, 2003). Differences were not found on demographic, predictor, or outcome variables between respondents who were missing data at T3 and those who were not.

When using FIML estimation for a general multilevel model, Snijders and Bosker (1999) considered samples of 30 or more to be large. Therefore, our sample size of 244 is adequate to address our research questions. But the question of how large is large enough in longitudinal analyses is complex. When longitudinal data are balanced and time structured and the same predictors are used in each part of the Level 2 models, which is the case with our sample and models, the parameter estimates with FIML, although asymptotic and approximate, can be considered to represent adequately the population parameters (Singer & Willett, 2003). Although this is true, we have noted in the limitation section that the p values should be treated circumspectly.

Prototypical plots are the preferred method for presenting growth results (Singer & Willett, 2003). The effects of the predictors on the growth parameters in the final fitted models can best be illustrated by “identifying a prototypical individual/child distinguished by particular predictor values” (Singer & Willett, 2003, p. 60). We do this by selecting meaningful values of the predictors to substitute into the fitted final models, obtaining the estimated value for the outcome (anxiety, depression), and plotting those trajectories, which gives us trajectories that would be typical for children in the population with those characteristics. These meaningful values of predictors represent prototypical children who are “high” (mean + 1 SD) or “low” (mean – 1 SD) on the variable of interest (e.g., SCL, RSA, marital conflict). In other words, the sample was not divided into groups to illustrate the findings; we are presenting the fitted “true” or “population” trajectories of children with high and low levels of the predictor variables similar to those in our sample.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Variable means, standard deviations, and correlations are shown in Table 1. Mean depression and anxiety symptoms decreased from T1 to T3. Marital conflict was significantly correlated with depression symptoms at all three time points and with anxiety symptoms during the first time point. Neither RSA nor SCL (either baseline or reactivity) was correlated significantly with depression or anxiety symptoms at any of the three time points. Race/ethnicity was significantly correlated with all RSA and SCL variables as well as marital conflict; however, it was not correlated with either anxiety or depression symptoms. SES was correlated significantly with marital conflict. BMI and sex were correlated significantly with baseline SCL.

Table 1.

Estimated Means, Standard Deviations, and Correlations Among Model Variables (N = 244)

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Depression T1 | — | ||||||||||||||

| 2. | Depression T2 | .47*** | — | |||||||||||||

| 3. | Depression T3 | .33*** | .37*** | — | ||||||||||||

| 4. | Anxiety T1 | .66*** | .34*** | .22*** | — | |||||||||||

| 5. | Anxiety T2 | .35*** | .67*** | .30*** | .45*** | — | ||||||||||

| 6. | Anxiety T3 | .30*** | .32*** | .68*** | .30*** | .47*** | — | |||||||||

| 7. | Marital Conflict | .26*** | .16* | .24*** | .23*** | .11 | .16 | — | ||||||||

| 8. | Baseline RSA | .01 | .01 | .07 | .07 | - .03 | .03 | .19** | — | |||||||

| 9. | RSA Reactivity | .01 | .02 | –.04 | –.09 | –.05 | –.09 | –.10 | –.44*** | — | ||||||

| 10. | Baseline SCL | .03 | –.02 | –.11 | .01 | .01 | –.06 | .01 | –.09 | .01 | — | |||||

| 11. | SCL Reactivity | –.03 | –.09 | –.06 | –.03 | –.06 | .03 | .06 | .01 | –.12† | .33*** | — | ||||

| 12. | Sexa | .02 | .04 | .09 | .13* | .14 | .12 | –.08 | –.01 | –.09 | –.15* | –.01 | — | |||

| 13. | SES | –.05 | .02 | –.05 | .00 | .06 | –.02 | –.17** | –.08 | –.05 | .07 | .10 | –.03 | — | ||

| 14. | Raceb | .03 | –.05 | .16 | .02 | –.02 | .11 | .16** | .28*** | –.13* | –.37*** | –.28*** | .04 | –.21*** | — | |

| 15. | BMI | –.01 | .00 | –.12 | –.00 | .03 | –.12 | .07 | .03 | –.11 | .14* | .07 | .09 | .00 | .12 | — |

| M | 5.67 | 4.73 | 3.79 | 7.31 | 5.83 | 5.11 | .02 | .15 | –.03 | 5.79 | 2.99 | 37.38 | 18.98 | |||

| SD | 4.33 | 4.20 | 3.23 | 4.98 | 4.60 | 3.91 | .77 | .08 | .06 | 4.48 | 2.70 | 9.92 | 3.75 | |||

Note. RSA = respiratory sinus arrhythmia; SCL = skin conductance level; SES = socioeconomic status; BMI = body mass index.

Sex is coded 1 = girls, 0 = boys.

Race is coded 1 = African American, 0 = European American.

p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Unconditional Models

Depression symptoms

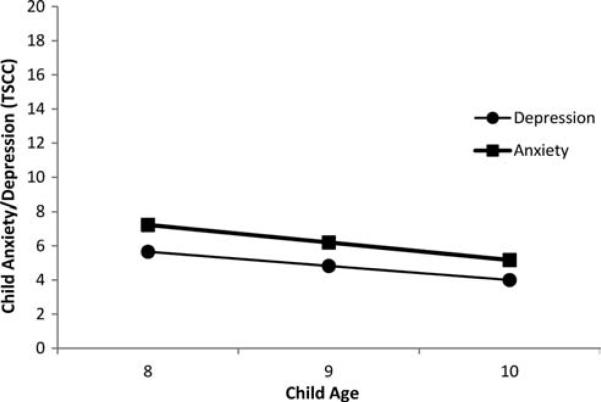

The unconditional depression symptoms model fit the data well (see Table 2 for the fit statistics and the variance of the slope and intercept). Means for both intercept and slope were significant (intercept M = 4.04, p < .001; slope M = –0.81, p < .001) indicating that at age 10, depression symptoms were significantly above zero and that they had been significantly decreasing since age 8 (see Figure 1). The correlation between the intercept and slope was nonsignificant (r = .13, p > .10), indicating that the change in depression symptoms was not related to symptom levels at age 10. The variance of the intercept (S2 = 6.35, p < .01) and slope (S2 = 1.98, p < .06) indicated that we could add our substantive predictors.

Table 2.

Fit Statistics and Variance of Slope and Intercept for Unconditional Models (N = 244)

| Depression |

Anxiety |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Estimate | SE | Estimate | SE |

| Intercept mean | 4.04*** | .24 | 5.20*** | .29 |

| Intercept variance | 6.35** | 2.02 | 10.99*** | 2.53 |

| Slope mean | –0.81*** | .15 | – 1.01 *** | .19 |

| Slope variance | 1.98† | 1.01 | 3.59** | 1.30 |

| Intercept and slope r | .13 | .27 | .39** | .14 |

| x2(1) | 0.04 | 1.79 | ||

| CFIa | 1.00 | 0.99 | ||

| TLIb | 1.00 | 0.97 | ||

| RMSEAc | .00 | .06 | ||

Note. CFI = comparative fit index; TLI = Tucker-Lewis index; RMSEA = root-mean-square error of approximation.

p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Figure 1.

Unconditional fitted models for depression and anxiety symptoms; both significantly decrease over time (p < .001). TSCC = Trauma Symptoms Checklist for Children (Briere, 1996).

Anxiety symptoms

The unconditional anxiety symptoms model fit the data well. The fit statistics and the variance of the slope and intercept are presented in Table 2. Means for both the intercept and slope were significant (intercept M = 5.20, p < .001; slope M = –1.01, p < .01), indicating that, on average, anxiety symptoms decreased over time (see Figure 1), and anxiety level at age 10 was greater than zero. The correlation between the slope, and the intercept was significant and positive (r = .39, p < .01), indicating that, on average, the higher the levels of anxiety symptoms at age 10, the more steep the slope was for anxiety symptoms over time. The variance of the intercept (S2 = 10.99, p < .001) and slope (S2 = 3.59, p < .01) were significant.

Conditional Models: Depression Symptoms

Examinations of interactions between baseline RSA and baseline SCL

For the RSA-B × SCL-B interaction model, marital conflict was significant in predicting growth in depression symptoms (Δχ2 = 21.98, Δdf = 2, p < .001; see Table 3). When the child sex, RSA-B, SCL-B, two-way interactions, and three-way interaction were each entered separately, they did not predict growth. The four-way interaction only marginally predicted the slope (Δχ2 = 3.05, Δdf = 1, p < .08). However, this interaction term did increase the amount of variance predicted in the slope to 16.2% from only 11.9% in the previous model without the four-way interaction. In many growth models, we often do not predict a large amount of variance in the slope (El-Sheikh et al., 2010; Keiley et al., 2005), but here we predict a substantial amount of variance in the slope and a similar amount in the intercept (17.3%). Because none of the child characteristics/demographic variables significantly predicted the growth parameters, they were not included in the final model (see Table 3). Parameter estimates for the final fitted model are presented in Table 4.

Table 3.

Depression Symptoms: Fit Statistics of and Delta-Chi-Square Statistics Testing for Predictor Significance (N = 244)

| Fit statistic | Uncond. | + Sex | + Marital Conflict | + RSA | + SCL | + 2-way | + 3-way | + 4-way on intercept | + 4-way on slope | + Demographics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline × Baseline | ||||||||||

| Χ2(df) | 0.036 | 0.03 (2) | 2.48 (3) | 2.49 (4) | 2.46 (5) | 5.49 (11) | 13.30(15) | 18.77 (17) | 15.72 (16) | 20.21 (19) |

| δΧ2(δdf) | 1.40 (2) | 21.98 (2)*** | .77 (2) | 1.39 (2) | 10.17 (12) | 9.82 (8) | 0.11 (1) | 3.05 (1)† | 4.47 (6) | |

| CFI | 1.000 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.98 | 1.00 | 0.99 |

| TLI | 1.03 | 1.07 | 1.02 | 1.05 | 1.08 | 1.18 | 1.05 | 0.95 | 1.00 | 0.96 |

| RMSEA | .00 | .00 | .00 | .00 | .00 | .00 | .00 | .02 | .00 | .02 |

| Intercept R2 | 1.2% | 9.2% | 9.2% | 9.2% | 10.9% | 16.6% | 16.6% | 17.3% | 19.4% | |

| Slope R2 | 0.4% | 1.5% | 2.2% | 3.2% | 7.9% | 11.9% | 11.9% | 16.2% | 14.5% | |

| Reactivity × Reactivity | ||||||||||

| Χ2(df) | 0.036 | 0.03 (2) | 2.48 (3) | 2.68 (5) | 3.42 (7) | 14.20 (13) | 22.67 (17) | 27.22 (19) | 26.72 (18) | 29.07 (21) |

| δΧ2(δdf) | 1.40 (2) | 21.98 (2)*** | 0.99 (4) | 6.75 (4) | 25.42 (12)* | 13.25 (8) | 4.67 (1)* | 0.50 (1) | 3.46 (6) | |

| CFI | 1.000 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.99 | 0.96 | 0.94 | 0.93 | 0.94 |

| TLI | 1.03 | 1.07 | 1.02 | 1.07 | 1.11 | 0.97 | 0.87 | 0.82 | 0.80 | 0.81 |

| RMSEA | .00 | .000 | .00 | .000 | .00 | .02 | .04 | .04 | .05 | .04 |

| Intercept R2 | 1.2% | 9.2% | 9.2% | 11.8% | 24.2% | 28.8% | 28.9% | 29.1% | 30.9% | |

| Slope R2 | 0.4% | 1.5% | 2.3% | 3.7% | 7.3% | 9.9% | 8.2% | 8.4% | 10.1% | |

Note. RSA = respiratory sinus arrhythmia; SCL = skin conductance level; CFI = comparative fit index; TLI = Tucker-Lewis index; RMSEA = root-mean-square error of approximation.

p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .001.

Table 4.

Depression Symptoms: Parameters Estimates for the Effects of Sex, Marital Conflict, RSA-B, SCL-B, RSA-R, SCL-R, and Their Interactions on Growth Factors, the Residual Variance of the Growth Factors, and the Amount of Variance Predicted in Each Growth Factor (N = 244)

| Baseline × Baseline |

Reactivity × Reactivity |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept (M = 5.30***, SE = 1.18) |

Slope (M = 0.08***, SE = 0.75) |

Intercept (M = 3.90***, SE = 0.42) |

Slope (M = –0.65*, SE = 0.29) |

|||||

| Predictors | B | SE | B | SE | B | SE | B | SE |

| Main effects | ||||||||

| Sex | 2.09 | 2.03 | 0.04 | 1.33 | 0.61 | 0.78 | –0.40 | 0.55 |

| Marital conflict | –0.36 | 2.54 | –1.03 | 1.52 | 1.93* | 0.89 | 0.15 | 0.58 |

| RSA-B | 5.24 | 8.76 | 5.34 | 5.71 | –1.24 | 3.16 | –0.25 | 2.28 |

| SCL-B | 0.31 | 0.23 | 0.16 | 0.15 | 0.06 | 0.08 | –0.05 | 0.06 |

| RSA-R | –8.60 | 7.67 | –5.37 | 5.53 | ||||

| SCL-R | –0.26† | 0.16 | –0.04 | 0.11 | ||||

| 2-way interactions | ||||||||

| RSA × SCL | – 2.13 | 1.43 | –1.28 | 0.90 | 1.37 | 2.97 | 2.54 | 2.07 |

| RSA × MC | 11.06 | 14.49 | 8.67 | 8.38 | 14.98 | 19.00 | 4.92 | 12.71 |

| RSA × Sex | –7.47 | 11.54 | 3.28 | 7.63 | 4.55 | 12.27 | –2.81 | 8.82 |

| SCL × MC | 0.23 | 0.41 | 0.28 | 0.24 | –0.11 | 0.20 | –0.02 | 0.13 |

| SCL × Sex | –0.54 | 0.36 | –0.03 | 0.23 | –0.11 | 0.24 | 0.06 | 0.16 |

| MC × Sex | 3.41 | 3.31 | 0.95 | 2.06 | 0.03 | 1.12 | –0.64 | 0.75 |

| 3-way interactions | ||||||||

| RSA × SCL × MC | - 2.11 | 2.23 | –2.22† | 1.31 | 1.22 | 4.82 | –1.37 | 3.16 |

| RSA × SCL × Sex | 3.36 | 2.12 | –0.38 | 1.38 | –3.79 | 3.93 | –1.96 | 2.75 |

| RSA × MC × Sex | - 25.26 | 18.45 | –14.24 | 11.29 | 33.67 | 21.73 | 9.67 | 14.83 |

| SCL × MC × Sex | - 0.57 | 0.68 | – 0.46 | 0.42 | –0.09 | 0.36 | 0.01 | 0.23 |

| 4-way interaction | ||||||||

| RSA × SCL × MC × Sex | 5.03 | 3.75 | 4.16† | 2.36 | –14.08* | 6.43 | –3.05 | 4.34 |

| Residual variance | 6.05** | 2.21* | 6.30*** | 3.23*** | ||||

| R 2 | 17.3% | 16.2% | 29.1% | 8.4% | ||||

Note. RSA = respiratory sinus arrhythmia; SCL = skin conductance level; RSA-B = RSA during baseline; RSA-R = RSA reactivity; SCL-B = SCL during baseline; SCL-R = SCL reactivity; MC = marital conflict.

p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Examinations of interactions between RSA reactivity and SCL reactivity

In addition to marital conflict significantly predicting growth (Δχ2 = 21.98, Δdf = 2, p < .001), the two-way interactions (e.g., RSA-R × SCL-R; RSA-R × Marital Conflict) also significantly predicted growth (Δχ2 = 25.42, Δdf = 12, p < .05). Further, the four-way interaction (i.e., Sex × Marital Conflict × RSA-B × SCL-B) significantly predicted the intercept (Δχ2 = 4.67, Δdf = 1, p < .05). Demographics did not significantly predict growth (see Table 3). Parameter estimates for the final fitted model are presented in Table 4. This model explains 29.1% of the intercept's variance and 8.4% of the slope's variance.

Conditional Models: Anxiety Symptoms

Examinations of interactions between baseline RSA and baseline SCL

As with depression symptoms, marital conflict significantly predicted growth in anxiety symptoms (Δχ2 = 16.24, Δdf = 2, p < .001; see Table 5). Sex also significantly predicted growth (Δχ2 = 6.54, Δdf = 2, p < .05), as did the four-way interaction between sex, marital conflict, RSA-B, and SCL-B on the slope (Δχ2 = 3.81, Δdf = 1, p < .05) and the intercept (Δχ2 = 4.07, Δdf = 1, p < .05). Demographics did not significantly predict growth (see Table 5). Parameter estimates for the final fitted model are in Table 6. This model explains 18.9% of the intercept's variance and 11.6% of the slope's variance.

Table 5.

Anxiety Symptoms: Fit Statistics of Models and Delta-Chi-Square Statistics Testing for Predictor Significance (N = 244)

| Fit statistics | Uncond. | + Sex | + Marital Conflict (MC) | + RSA | + SCL | + 2-way: All 2-way interactions of Sex, MC, RSA, SCL on both intercept and slope: 12 parametersa | + 3-way: All 3-way interactions of Sex. MC, RSA, SCL on both intercept and slope: 8 parametersa | + 4-way on intercept: One 4-way interaction of Sex, MC, RSA, SCL: 1 parametera | + 4-way on slope: One 4-way interaction of Sex, MC, RSA, SCL: 1 parametera | + Demographics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline × Baseline | ||||||||||

| Χ2(df) | 0.04 (1) | 1.76(2) | 4.69 (3) | 5.83 (4) | 5.91 (5) | 12.32(11) | 17.22 (15) | 19.90 (17) | 16.09 (16) | 19.34 (19) |

| δΧ2(δdf) | 6.54 (2)* | 16.24 (2)*** | 0.42 (2) | 2.04 (2) | 10.08 (12) | 11.46 (8) | 4.07 (1)* | 3.81 (1)* | 8.29 (6) | |

| CFI | 0.99 | 1.00 | 0.99 | 0.98 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.98 | 0.97 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| TLI | 0.98 | 1.01 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.98 | 0.96 | 0.94 | 0.93 | 1.00 | 0.99 |

| RMSEA | .02 | .00 | .05 | .04 | .03 | .02 | .03 | .03 | .01 | .01 |

| Intercept R2 | 2.7% | 6.1% | 6.3% | 6.7% | 12.4% | 17.1% | 17.2% | 18.9% | 23.2% | |

| Slope R2 | 0.1% | 1.5% | 1.8% | 2.1% | 5.2% | 9.1% | 8.6% | 11.6% | 13.8% | |

| Reactivity × Reactivity | ||||||||||

| Χ2(df) | 0.04 (1) | 1.76(2) | 4.688 (3) | 5.838 (5) | 7.34 (7) | 17.10 (13) | 20.44 (17) | 24.80 (19) | 21.40(18) | 23.40 (21) |

| δΧ2(δdf) | 6.54 (2)* | 16.24 (2)*** | 1.60 (4) | 7.00 (4) | 12.43 (12) | 10.05 (8) | 3.91 (1)* | 3.40 (1)† | 4.31 (6) | |

| CFI | 0.99 | 1.00 | 0.985 | 0.992 | 1.00 | 0.96 | 0.97 | 0.95 | 0.97 | 0.98 |

| TLI | 0.98 | 1.01 | 0.954 | 0.977 | 0.99 | 0.89 | 0.91 | 0.86 | 0.91 | 0.94 |

| RMSEA | .02 | .00 | .048 | .026 | .01 | .04 | .03 | .04 | .03 | .02 |

| Intercept R2 | 2.7% | 6.1% | 6.9% | 8.2% | 15.5% | 22.1% | 22.1% | 23.0% | 24.0% | |

| Slope R2 | 0.1% | 1.5% | 1.9% | 3.0% | 9.4% | 14.1% | 13.5% | 15.7% | 16.9% | |

Note. RSA = respiratory sinus arrhythmia; SCL = skin conductance level; CFI = comparative fit index; TLI = Tucker-Lewis index; RMSEA = root-mean-square error of approximation.

See Table 6 for the actual interactions that were added at each step.

p<.10.

p < .05.

p < .001.

Table 6.

Anxiety Symptoms: Parameters Estimates for the Effects of Sex, Marital Conflict, RSA-B, SCL-B, RSA-R, SCL-R, and Their Interactions on Growth Factors, the Residual Variance of the Growth Factors, and the Amount of Variance Predicted in Each Growth Factor (N = 244)

| Baseline × Baseline |

Reactivity × Reactivity |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept (M = 5.93***, SE = 1.40) | Slope (M =–0.01, SE = 0.91) | Intercept (M = 4.95***, SE =0.53) | Slope (M = –0.77*, SE =0.35) | |||||

| Predictor | B | SE | B | SE | B | SE | B | SE |

| Main effects | ||||||||

| Sex | 2.59 | 2.40 | 0.62 | 1.62 | 0.90 | 0.98 | –0.09 | 0.65 |

| MC | –0.88 | 3.04 | –1.05 | 1.87 | 1.93† | 1.14 | –0.27 | 0.71 |

| RSA-B | –2.98 | 10.35 | 0.21 | 6.95 | –6.69† | 4.02 | –3.89 | 2.74 |

| SCL-B | 0.27 | 0.28 | 0.15 | 0.18 | 0.12 | 0.10 | –0.06 | 0.07 |

| RSA-R | –14.49 | 9.90 | –2.62 | 6.67 | ||||

| SCL-R | –0.28 | 0.20 | 0.08 | 0.13 | ||||

| 2-way interactions | ||||||||

| RSA × SCL | –1.77 | 1.71 | –1.15 | 1.10 | 1.78 | 3.86 | 1.25 | 2.52 |

| RSA × MC | 13.63 | 17.36 | 5.25 | 10.30 | 27.17 | 24.82 | 3.61 | 15.66 |

| RSA × Sex | –11.38 | 13.65 | – 3.24 | 9.27 | –1.65 | 15.80 | –6.87 | 10.63 |

| SCL × MC | 0.42 | 0.50 | 0.29 | 0.30 | 0.11 | 0.26 | 0.16 | 0.16 |

| SCL × Sex | –0.81* | 0.42 | –0.36 | 0.28 | –0.17 | 0.31 | –0.21 | 0.20 |

| MC × Sex | 5.70 | 3.93 | 1.63 | 2.51 | –0.48 | 1.44 | –0.22 | 0.91 |

| 3-way interactions | ||||||||

| RSA × SCL × MC | –2.67 | 2.68 | –1.74 | 1.61 | 1.78 | 6.32 | 3.22 | 3.91 |

| RSA × SCL × Sex | 6.15* | 2.50 | 2.03 | 1.67 | –4.28 | 5.10 | –2.12 | 3.34 |

| RSA × MC × Sex | –43.62* | 22.00 | –18.19 | 13.82 | 11.04 | 27.93 | 12.26 | 17.94 |

| SCL × MC × Sex | –1.18 | 0.80 | –0.60 | 0.51 | –0.49 | 0.46 | –0.21 | 0.29 |

| 4-way interaction | ||||||||

| RSA × SCL × MC × Sex | 9.05* | 4.41 | 5.62* | 2.85 | –16.09* | 8.23 | –9.71† | 5.24 |

| Residual variance | 9.84*** | 3.56** | 9.65*** | 3.52** | ||||

| R 2 | 18.9% | 11.6% | 23.0% | 15.7% | ||||

Note. RSA = respiratory sinus arrhythmia; SCL = skin conductance level; RSA-B = RSA during baseline; RSA-R = RSA reactivity; SCL-B = SCL during baseline; SCL-R = SCL reactivity; MC = marital conflict.

p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Examinations of interactions between RSA reactivity and SCL reactivity

Aside from sex (Δχ2 = 6.54, Δdf = 2, p < .05) and marital conflict (Δχ2 = 16.24, Δdf = 2, p < .001), the addition of other predictors (i.e., RSA, SCL, all two- and three-way interactions, and demographics) did not significantly predict growth in anxiety symptoms (see Table 5). However, when added, the four-way interaction between sex, marital conflict, RSA-R, and SCL-R was a significant predictor of the intercept (Δχ2 = 3.91, Δdf = 1, p < .05) and a marginally significant predictor of the slope (Δχ2 = 3.40, Δdf = 1, p < .07). However, once again, an increase existed in the amount of variance predicted in the slope upon the inclusion of the four-way interaction term, from 13.5% to 15.7%. In addition, 23.0% of the intercepts’ variance was predicted. Parameter estimates for the final fitted model are in Table 6.

Prototypical Plots

The four-way interactions can best be illustrated by using the well-established procedure of constructing prototypical plots (Singer & Willett, 2003). To do this, we begin by identifying a prototypical individual distinguished by particular predictor values. We select meaningful values of the predictors to substitute into the fitted final model, obtain the estimated value for the outcomes (depression and anxiety symptoms), and plot trajectories. This provides trajectories that would be typical for individuals in the population with those characteristics. In other words, we present the fitted “true” or “population” trajectories of depression and anxiety symptoms in children similar to those in our sample. The meaningful values chosen for prototypical individuals were 0 or 1 for sex (boy or girl), and ±1 standard deviation from the mean for “high” and “low” levels of marital conflict, RSA-B, RSA-R, SCL-B, and SCL-R.

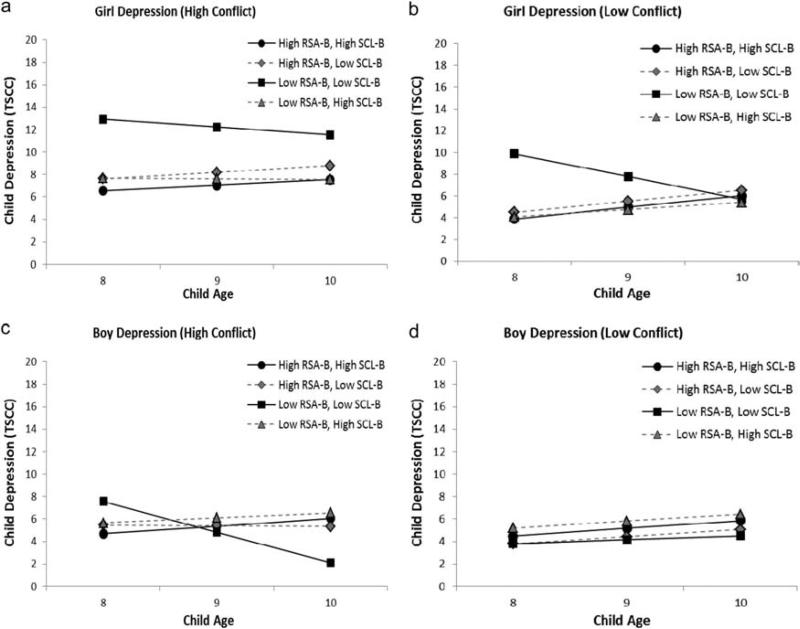

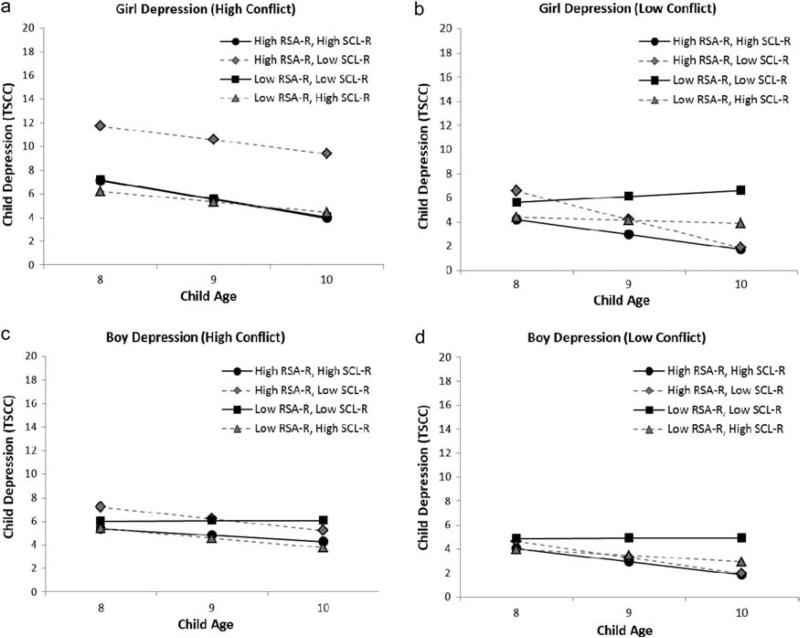

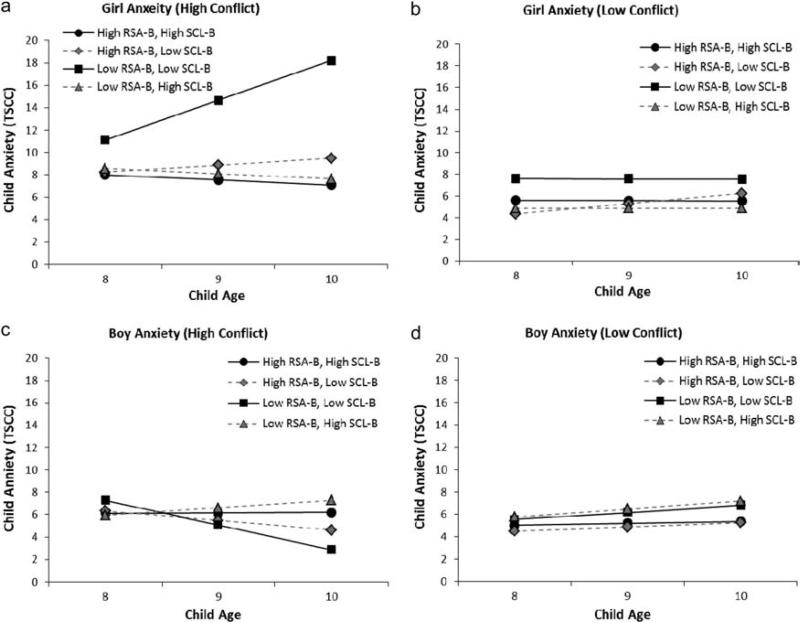

For each of the four final models, the various combinations of sex and high or low levels of RSA (baseline or reactivity), SCL (baseline or reactivity), and marital conflict result in 16 prototypical individuals (see Figures 2–5). For example, plots in Figure 2a are of prototypical girls from high conflict homes who have one of the following sets of characteristics: high RSA-B and high SCL-B, high RSA-B and low SCL-B, low RSA-B and low SCL-B, or low RSA-B and high SCL-B.

Figure 2.

Change in depressive symptoms over time for prototypical boys and girls in the population at high and low values (M ± 1 SD) of RSA-Baseline, SCL-Baseline, and marital conflict. The four-way interaction (RSA- Baseline × SCL-Baseline × Marital Conflict × Sex) predicts the slope (p < .08). RSA = respiratory sinus arrhythmia; SCL = skin conductance level; TSCC = Trauma Symptoms Checklist for Children (Briere, 1996).

Figure 5.

Anxiety symptoms over time for prototypical boys and girls in the population at high and low values (M ± 1 SD) of RSA-Reactivity, SCL-Reactivity, and marital conflict. The four-way interaction (RSA-Reactivity × SCL- Reactivity × Marital Conflict × Sex) predicts the slope (p < .07). RSA = respiratory sinus arrhythmia; SCL = skin conductance level; TSCC = Trauma Symptoms Checklist for Children (Briere, 1996).

Children with high RSA-R and low SCL-R have a “reciprocal parasympathetic” profile. Children with low RSA-R and high SCL-R have a “reciprocal sympathetic” profile. Those with low RSA-R and low SCL-R are referred to as “coinhibitors,” and those with high RSA-R and high SCL-R are “coactivators.” Although the terms “reciprocal parasympathetic,” “reciprocal sympathetic,” “coinhibition,” and “coactivation” are most accurately applied to reactivity (Berntson et al., 1991), for the sake of simplicity, we also use them to refer to baseline levels (El-Sheikh et al., 2009). Thus, a high RSA-B and low SCL-B is referred to as “reciprocal parasympathetic,” low RSA-B and high SCL-B is referred to as “reciprocal sympathetic,” etc.3

We also examined whether the slopes of the prototypical trajectories were significantly different from zero. Although it is not a customary or necessary step for interpreting differences between prototypical growth trajectories (see Singer & Willett, 2003), it is of conceptual interest to us in this newly developing area of inquiry whether children with certain RSA, SCL, marital conflict, and sex characteristics significantly change in depression or anxiety symptoms over time. We therefore tested whether the slope of each prototypical trajectory was significantly different from zero. In reporting the results, we first present findings based on prototypical plots and follow established guidelines of reporting such results.

Depression symptoms: Baseline RSA × Baseline SCL

Figures 2a–2d present prototypical plots of growth in depression symptoms for girls and boys exposed to lower and higher levels of parental marital conflict. As indicated earlier, the chi-square test indicated the four-way interaction significantly predicted the slope. Although the majority of slopes in these figures are flat or slightly positive, the slopes are negative for all coinhibitors (i.e., low RSA and low SCL profiles; see Figures 2a–2c), except for boys from low conflict homes (see Figure 2d). These coinhibitors begin at the highest risk for depression symptoms at 8 years but then decrease in risk over time to more typical depression levels by age 10 (although boys from high-conflict homes at 10 years have much lower depression symptoms). In addition, as depicted in Figure 2a, girl coinhibitors experiencing higher marital conflict have the highest levels of depression symptoms at each time point. However, it is important to note that the four-way interaction was not significant on the intercept (i.e., depression at T3). For boys in high-conflict homes, those with a reciprocal parasympathetic pattern have decreasing symptoms over time, whereas those with a reciprocal sympathetic pattern have increasing symptoms longitudinally; the opposite is true for girls in high-conflict homes.

Again, although not necessary for comparisons, the significance of each prototypical slope was tested. Only coinhibiting boys in high conflict families approached conventional levels of statistical significance (p < .09) for their depressive symptoms slope (decreasing).

Depression symptoms: RSA Reactivity × SCL Reactivity

The four-way interaction significantly predicted the intercept (i.e., depression at age 10) for the RSA-R by SCL-R model. As depicted in Figure 3a, girls with a reciprocal parasympathetic pattern of responding (i.e., higher RSA-R with lower SCL-R) in higher conflict homes are at highest risk for depression symptoms across time, being at least four points above other girls in similar homes. Yet girls with the same physiological profile in lower conflict homes have next to lowest depression symptoms at 10 years (see Figure 3b). Coinhibiting girls in low-conflict homes slightly increase in depression symptoms over time until they have the highest depression symptom levels at 10 years. For boys, the various RSA-R and SCL-R configurations are not particularly telling of their depression symptom trajectories (see Figures 3c and 3d); however, it is notable that boys with a coinhibition pattern have the highest stable depression symptoms across time, whereas others declined.

Figure 3.

Depressive symptoms over time for prototypical boys and girls in the population at high and low values (M ± 1 SD) of RSA-Reactivity, SCL-Reactivity, and marital conflict. The four-way interaction (RSA-Reactivity × SCL-Reactivity × Marital Conflict × Sex) predicts the intercept (p < .05). RSA = respiratory sinus arrhythmia; SCL = skin conductance level; TSCC = Trauma Symptoms Checklist for Children (Briere, 1996).

In examining changes over time, girls from higher conflict homes (see Figure 3a) all significantly decrease in depression symptoms over time (p < .05), except those with a reciprocal parasympathetic profile. In lower conflict homes (see Figure 3b), girls with a coactivating and reciprocal parasympathetic pattern of responding decreased in depression symptoms over time, whereas the others did not. For boys, only those from higher conflict homes with reciprocal parasympathetic or sympathetic profile had declining symptoms over time.

Anxiety symptoms: Baseline RSA × Baseline SCL

For Baseline × Baseline interactions (see Figures 4a–4d), the chi-square test indicated that the four-way interaction predicted the slope. Coinhibiting girls in higher conflict homes are at highest risk for anxiety symptoms, demonstrating the highest level of anxiety symptoms at age 8 and increasing considerably over time. Conversely, coinhibiting boys show the opposite trend, starting out highest at age 8 and declining to the lowest levels of anxiety symptoms at age 10. For boys in high-conflict homes, those with a reciprocal parasympathetic pattern decrease over time, whereas those with a reciprocal sympathetic pattern increase with development. However (as with depression baseline by baseline interactions), the opposite is true for girls in high-conflict homes. In examining the significance of the prototypical plot slopes, none were significantly different from zero.

Figure 4.

Anxiety symptoms over time for prototypical boys and girls in the population at high and low values (M ± 1 SD) of RSA-Baseline, SCL-Baseline, and marital conflict. The four-way interaction (RSA-Baseline × SCL-Baseline × Marital Conflict × Sex) predicts the slope (p < .05). RSA = respiratory sinus arrhythmia; SCL = skin conductance level; TSCC = Trauma Symptoms Checklist for Children (Briere, 1996).

Anxiety symptoms: RSA Reactivity × SCL Reactivity

As with baseline results, the chi-square indicated that the four-way interaction significantly predicted the slope. Of girls in higher conflict homes, only those with the reciprocal parasympathetic profile did not decrease in anxiety symptoms over time (see Figure 5a), maintaining higher symptoms throughout. Of girls in lower conflict homes, those with a coinhibiting profile increased in anxiety symptoms over time, and those with a reciprocal sympathetic response remained relatively stable. Boys from higher conflict homes appear relatively similar, except for those with a coactivation profile who remain stable in anxiety symptoms across time. In lower conflict homes, boys with a coactivation profile are stable (although lowest at each wave) and boys with a coinhibiting profile increase slightly over time. Boys with reciprocal profiles decrease in both high- and low-conflict homes. Only boys from lower conflict homes with reciprocal parasympathetic profiles have a slope that significantly differs from zero.

Discussion

We examined marital conflict and interactions between RSA and SCL as predictors of the development of depression and anxiety symptoms from middle to late childhood. Analyses indicated that marital conflict, child sex, RSA, and SCL interact to create differential risk for internalizing symptoms over time. Growth curve analyses illustrated that average levels of internalizing symptoms were relatively low and decreased from middle to late childhood. However, the most notable findings reveal that girls with low RSA and low SCL (i.e., coinhibition) at baseline, or girls with high RSA and low SCL during a challenging task (i.e., reciprocal parasympathetic activation), are susceptible to high or escalating internalizing symptoms, particularly in the context of higher marital conflict. Results suggest that concurrent examinations of environmental risk factors and multiple indices of physiological activity may enhance understanding of the development of internalizing symptoms.

Baseline RSA and SCL

Girls with lower RSA and lower SCL (i.e., coinhibition) at baseline reported high-stable depression symptoms and high-increasing anxiety symptoms in the context of marital conflict, whereas their boy counterparts reported decreasing levels of depression and anxiety from middle to late childhood. Notably, coinhibited girls with high exposure to marital conflict reported levels of anxiety by age 10 that were more than triple the overall age 10 mean, suggesting continuing influences of marital conflict, RSA, and SCL over time. Children with other profiles of marital conflict and ANS activity reported relatively low and similar levels of depression and anxiety symptoms from middle to late childhood, with the exception of girls with a coinhibited ANS profile and low marital conflict, who reported decreasing depression levels from age 8 to age 10.

Low baseline RSA is considered a marker of poor emotion regulation at the physiological level. Lower RSA has been linked with symptoms of anxiety and depression, although, like the present study, bivariate associations are sometimes null, modest in magnitude, or characterized by sex differences (Beauchaine, 2001; Greaves-Lord et al., 2007). More relevant to the present study, and consistent with our findings, several studies have identified lower RSA as a moderator, or vulnerability factor, which exacerbates the association between marital conflict and internalizing problems (El-Sheikh et al., 2001; Katz & Gottman, 1997). Children with lower baseline RSA may respond more negatively (e.g., angrily) or cope less effectively with the stress of marital conflict. Lower SCL among girls with elevated internalizing symptoms in the present study is somewhat surprising given existing evidence but also must be considered in conjunction with other environmental (i.e., marital conflict) and individual (i.e., sex, RSA) variables.

The results of several recent studies suggest that the risk for externalizing problems (El-Sheikh et al., 2009; Gordis et al., 2010) and internalizing problems (the current study) in the context of family conflict is exacerbated among children with a combination of lower baseline RSA and lower baseline SCL. The apparent ambivalence of low RSA (i.e., low PNS activation) and the absence of corresponding high SCL (i.e., high SNS activation) may reflect poor readiness to respond to marital conflict among girls, potentially increasing risk for both internalizing and externalizing behaviors. Other research suggests that marital conflict increases risk for both internalizing and externalizing problems (Davies, Harold, Goeke-Morey, & Cummings, 2002), which often co-occur. The fact that coinhibition was maladaptive only among girls is consistent with the heightened risk of emerging anxiety and depression among girls compared with boys around the transition to adolescence (Hankin & Abramson, 2001; Van Oort, Greaves-Lord, Verhulst, Ormel, & Huizink, 2009) and suggests that the same physiological response is differentially influential depending on child sex. Results of the current study suggest that it may be possible to identify girls at risk for escalating internalizing problems earlier in development, by considering both family risk and multiple indices of physiological functioning. Linking profiles of physiological activity with behavioral and psychological factors amenable to intervention (e.g., coping) is an important direction for future research.

RSA and SCL Reactivity

In analyses with RSA and SCL reactivity, girls with increasing RSA and decreasing SCL in response to a lab challenge (i.e., reciprocal parasympathetic activation) reported the highest levels of anxiety and depression symptoms from middle through late childhood in the context of higher marital conflict. Their internalizing symptoms did not increase from age 8 to age 10 but remained elevated compared with children with other combinations of sex, marital conflict, RSA, and SCL. Thus, it appears that the risk associated with marital conflict and reciprocal parasympathetic activation among girls had taken effect by middle childhood.

Higher RSA and lower SCL should be adaptive under normal circumstances (e.g., at baseline), because higher RSA is believed to support or indicate emotion regulation and lower SCL may reflect lower trait anxiety (Beauchaine, 2001; Porges, 2007). However, in response to challenge or stress, a calm or passive physiological response may not support active and engaged coping responses. Active coping (e.g., problem solving, cognitive restruc turing) and seeking social support, for example, may protect children (particularly girls) from feelings of depression and low self-esteem in the context of marital conflict, whereas avoidance coping may operate as a vulnerability factor for behavioral and psychological maladjustment (Nicolotti, El-Sheikh, & Whitson, 2003). More generally, engaged coping responses appear protective in a variety of stressful circumstances for which there is a viable coping response that can alleviate the problem or regulate upset feelings associated with the problem (Compas, Connor-Smith, Saltzman, Thomsen, & Wadsworth, 2001). Instead of supporting engaged coping, these physiological responses (e.g., higher RSA and lower SCL in response to stress) appear more consistent with disengaged responses to challenge or stress or a failure to adapt to the demands of the situation (e.g., passive exposure). Inconsistent with our general line of reasoning, however, is evidence that some forms of engaged coping (e.g., involvement in parental marital conflict) may be maladaptive responses to stressors, like marital conflict, over which children may have little control (Shelton & Harold, 2008). Thus, our interpretation of findings should be viewed as tentative pending replication and explicit measurement of children's coping behaviors and other psychological characteristics (e.g., perceived control) in conjunction with ANS activity.

Unlike baseline findings in the present study, reactivity results are not consistent with earlier work that predicted child externalizing behavior (El-Sheikh et al., 2009; Gordis et al., 2010). Thus, whereas the relative risk associated with marital conflict and certain baseline levels of RSA and SCL may not differ across internalizing and externalizing behavior, RSA and SCL reactivity to challenge or stress may differentially predict these outcomes. Coactivation and coinhibition in response to stress (reactivity) may incur risk for externalizing behavior in the context of marital conflict (El-Sheikh et al., 2009), whereas reciprocal parasympathetic activation in response to stress (reactivity) may increase risk for internalizing problems (but not externalizing problems), perhaps in part because this physiological response may limit the likelihood of angry or aggressive responses associated with externalizing problems. In future research, it will be important to examine the unique and shared variance of internalizing and externalizing symptoms to provide a more comprehensive picture of family and ANS influences.

Limitations

It is important to note that the current research cannot answer questions regarding marital conflict's effects on the ANS. Psycho-physiological response patterns are likely susceptible to environmental influence. For instance, educational, social-emotional, and health enrichment in early childhood have been linked with adaptive SNS arousal in response to laboratory tasks (i.e., increased amplitude and speed of electrodermal responding) during preadolescence in a controlled, experimental trial (Raine et al., 2001). Further, boys with a strong RSA suppression to lab stressors who experienced higher marital conflict showed decreases in resting RSA over time (El-Sheikh & Hinnant, 2011). Despite some malleability, baseline and reactivity levels of ANS parameters are moderately stable in middle to late childhood (Bornstein & Suess, 2000; Calkins & Keane, 2004; Doussard-Roosevelt, Montgomery, & Porges, 2003; El-Sheikh, 2005; El-Sheikh et al., 2007) and, thus, may function primarily as moderators of environmental stress by late childhood. It will be important for future research to examine the etiology of ANS profiles and to consider the potential reciprocal relationship between ANS functioning and environmental stressors.

Regarding model complexity and the examination of multiple moderators of risk, one potentially beneficial methodology is a “person-centered” approach (Hagenaars & McCucheon, 2002; McLachlan & Peel, 2000). This would allow researchers to extract ANS profiles that exist in the samples rather than relying on rules of thumb (e.g., one standard deviation above and below the mean) to create profiles. This more deductive method may provide more meaningful groupings of children and identify ANS profiles not typically considered.

Although several inclusion/exclusion criteria were implemented (e.g., no attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder or learning or intellectual disability) and several variables were controlled in analyses to reduce potential confounds, it is plausible that third variables may have been operative (e.g., prior diagnoses of mood and anxiety disorders among children and parents). Further, the community sample may limit generalizability of findings to children with clinically significant internalizing symptoms. Inconsistent with some studies, we did not observe direct effects between our physiological parameters and internalizing symptoms (Dietrich et al., 2007; Weems et al., 2005). Nevertheless, this is consistent with other studies in which predominantly moderation effects were found in these associations illustrative of aggregation of risk for children with less optimal physiological regulation in conjunction with family risk (El-Sheikh et al., 2001; El-Sheikh & Whitson, 2006). In addition, although examining our research questions with three waves of data is an advance in the field, this did not enable the assessment of nonlinear trajectories of internalizing symptoms that may indeed characterize the course of development. In a newly developing area of inquiry such as the one addressed in our study, concern for Type II error is as serious as that for the Type I error, and there is typically more allowance for reporting marginal effects. However, we consider these higher order interactions that approached conventional level of statistical significance preliminary pending replication. Finally, extending the age range across the transition to adolescence will likely enhance understanding of developmental trajectories of internalizing symptoms, especially as they may differ for boys and girls. Another fruitful direction for future research is to examine changes in marital conflict and ANS functioning over time as they relate to internalizing symptoms.

Despite these limitations, the current study provides novel evidence about interactions between marital conflict and ANS functioning as differential predictors of internalizing problems among boys and girls. Findings suggest that sex of child should not be overlooked as a risk factor for internalizing problems in childhood. Identification of risk in middle and late childhood is particularly important as children approach the emotional volatility of adolescence, when more significant internalizing problems often emerge.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant R01-HD046795 to Mona El-Sheikh. We wish to thank the staff of our research laboratory, most notably Lori Staton and Bridget Wingo, for data collection and preparation. We also thank school personnel, children, and parents who participated.

Footnotes

We examined the estimated correlations among duration of cohabitation and biological versus step-parents and all of our other study variables. For neither duration of cohabitation nor biological versus not-biological-parent status was any of the estimated correlations with any anxiety, depression, RSA baseline, RSA reactivity, SCL baseline, SCL reactivity variable at Times 1, 2, or 3 significant (i.e., had a p <.05). At Time 1, marital conflict was related to cohabitation (r = –.14, p = .03), but the relation was weak. We also examined the relations among cohabitation and biological parent status and the control predictors. They were not related to BMI or child sex, but they were related only to two of the control variables, SES and race, at Time 1 (ps <.01). Given that we had controlled for SES and race in all analyses, cohabitation and biological parent status were not associated with either any ANS parameter or adjustment outcome variables, we decided that it was not necessary to add two additional controls in what are already complex models.

To insure that this composite was the best way to examine the effects of marital conflict, we refit all of the conditional models separately for child reports, mother reports, and father reports of marital conflict. Breaking marital conflict out by reporter basically did not change the results. Hence, we report only the series of models in which marital conflict is measured as a composite of child, mother, and father reports. Given that the marital composite used in this study is the same as that used in several other studies stemming from this data set (e.g., El-Sheikh et al., 2009), maintaining the same variable across studies facilitates comparison of findings.

Important to note is that the “low” value for SCL-R is small but positive. Thus, the coinhibiting profile may more accurately be labeled “uncoupled parasympathetic withdrawal” and reciprocal sympathetic be labeled “uncoupled parasympathetic activation.”

Contributor Information

Mona El-Sheikh, Department of Human Development and Family Studies, Auburn University.

Margaret Keiley, Department of Human Development and Family Studies, Auburn University.

Stephen Erath, Department of Human Development and Family Studies, Auburn University.

W. Justin Dyer, Department of Human Development and Family Studies, Brigham Young University..

References

- Angold A. Childhood and adolescent depression. I. Epidemiological and aetiological aspects. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1988;152:601–617. doi: 10.1192/bjp.152.5.601. doi:10.1192/bjp.152.5.601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. The stormy decade: Fact or fiction? Psychology in the Schools. 1964;1:224–231. [Google Scholar]

- Barber BK, Olson JA. Assessing the transitions to middle and high school. Journal of Adolescent Research. 2004;19:3–30. doi:10.1177/0743558403258113. [Google Scholar]

- Beauchaine TP. Vagal tone, development, and Gray's Motivational Theory: Toward an integrated model of autonomic nervous system functioning in psychopathology. Development and Psychopathology. 2001;13:183–214. doi: 10.1017/s0954579401002012. doi:10.1017/S0954579401002012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beauchaine TP. Some difficulties in interpreting psychophysio-logical research with children. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 2009;74:80–88. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5834.2009.00509.x. doi:10.1111/j.1540-5834.2009.00509.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell DJ, Foster SL, Mash EJ, editors. Handbook of behavioral and emotional problems in girls. Kluwer Academic/Plenum Press; New York, NY: 2005. doi:10.1007/b107822. [Google Scholar]

- Berntson GG, Bigger JT, Jr., Eckberg DL, Grossman P, Kauf-mann PG, Malik M, van der Molen MW. Heart rate variability: Origins, methods, and interpretive caveats. Psychophysiology. 1997;34:623–648. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1997.tb02140.x. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8986.1997.tb02140.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berntson GG, Cacioppo JT, Quigley KS. Autonomic determinism: The modes of autonomic control, the doctrine of autonomic space, and the laws of autonomic constraint. Psychological Review. 1991;98:459–487. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.98.4.459. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.98.4.459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein MH, Suess PE. Child and mother cardiac vagal tone: Continuity, stability, and concordance across the first 5 years. Developmental Psychology. 2000;36:54–65. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.36.1.54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briere J. Trauma Symptom Checklist for Children (TSCC): Professional manual. Psychological Assessment Resources; Odessa, FL: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Calkins SD, Keane SP. Cardiac vagal regulation across the preschool period: Stability, continuity, and implications for childhood adjustment. Developmental Psychobiology. 2004;45:101–112. doi: 10.1002/dev.20020. doi:10.1002/dev.20020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, Bem DJ, Elder G. Continuities and consequences of interactional styles across the life course. Journal of Personality. 1989;57:375–406. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1989.tb00487.x. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6494.1989.tb00487.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole DA, Tram JM, Martin JM, Hoffman KB, Ruiz MD, Jacquez FM, Maschman TL. Individual differences in the emergence of depressive symptoms in children and adolescents: A longitudinal investigation of parent and child reports. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2002;111:156–165. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.111.1.156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compas BE, Connor-Smith JK, Saltzman H, Thomsen AH, Wadsworth ME. Coping with stress during childhood and adolescence: Problems, progress, and potential theory in and research. Psychological Bulletin. 2001;127:87–127. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.127.1.87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford TN, Cohen P, Midlarsky E, Brook JS. Internalizing symptoms in adolescents: Gender differences in vulnerability to parental distress and discord. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2001;11:95–118. doi:10.1111/1532-7795.00005. [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Davies P. Marital conflict and children: An emotional security perspective. Guilford Press; New York, NY: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Davies PT, Harold GT, Goeke-Morey MC, Cummings EM. Child emotional security and interparental conflict. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 2002;67 (Serial No. 270) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietrich A, Riese H, Sondeijker FEPL, Greaves-Lord K, van Roon AM, Ormel J, Rosmalen JGM. Externalizing and internalizing problems in relation to autonomic function: A population-based study in preadolescents. Journal of American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2007;46:378–386. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e31802b91ea. doi:10.1097/CHI.0b013e31802b91ea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doussard-Roosevelt JA, Montgomery LA, Porges SW. Short-term stability of physiological measures in kindergarten children: Respiratory sinus arrhythmia, heart period, and cortisol. Developmental Psychobiology. 2003;43:231–242. doi: 10.1002/dev.10136. doi:10.1002/dev.10136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrensaft MK, Vivian D. Spouses’ reasons for not reporting existing marital aggression as a marital problem. Journal of Family Psychology. 1996;10:443–453. doi:10.1037/0893-3200.10.4.443. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott DM, Briere J. Forensic sexual abuse evaluations of older children: Disclosures and symptomatology. Behavioral Sciences & the Law. 1994;12:261–277. doi:10.1002/bsl.2370120306. [Google Scholar]