Abstract

Background and Aim:

To determine efficacy safety and the cost effectiveness, of the four most commonly prescribed statins (rosuvastatin, atorvastatin, pravastatin, and simvastatin) in the treatment of dyslipidemia among diabetic patients.

Materials and Methods:

This is a cohort, observational, population-based study conducted at diabetic clinics of the Hamad Medical Hospital and Primary Health Care Centers (PHCC) over a period from January 2007 to September 2012. The study included 1,542 consecutive diabetes patients above 18 years of age diagnosed with dyslipidemia and prescribed any of the indicated statins. Laboratory investigations were taken from the Electronic Medical Records Database (EMR-viewer). The sociodemographic, height, weight, and physical activities were collected from Patient's Medical Records. Information about statin was extracted from the pharmacy drug database. The effective reductions in total cholesterol using rosuvastatin with atorvastatin, simvastatin, and pravastatin in achieving cholesterol goals and improving plasma lipids in dyslipidemic diabetic patients were measured. Serum lipid levels measured a 1 week before the treatment and at the end 2nd year.

Results:

Rosuvastatin (10 mg) was the most effective in reducing low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C; 28.59%), followed by simvastatin 20 mg (16.7%), atorvastatin 20 mg (15.9%), and pravastatin 20 mg (11.59.3%). All statins were safe with respect to muscular and hepatic functions. Atorvastatin was the safest statin as it resulted in the least number of patients with microalbuminuria (10.92%) as compared to other statins. Treatment with rosuvastatin 10 mg was more effective in allowing patients to reach European and Adult Treatment Plan (ATP) III LDL-C goals as compared to other statins (P < 0.0001) and produced greater reductions in LDL-C, total cholesterol, and non-HDL-C, produced similar or greater reductions in triglycerides (TGs) and increased in HDL-C.

Conclusion:

Rosuvastatin 10 mg was the most effective statin in reducing serum lipids and total cholesterol in dyslipidemic diabetic patients.

KEY WORDS: Atorvastatin, cost effective, dyslipidemic diabetic patients, efficacy, pravastatin, rosuvastatin, safety of statin use in dyslipidemic diabetic patients, safety, simvastatin

Introduction

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is one of the major noncommunicable diseases with increasing prevalence in both the developed and developing world.[1] Middle East region has seen some of the largest growth in DM in the world. Diabetes is now commonly recognized as a ‘coronary heart disease risk equivalent’.[2,3,4] This is mainly attributed to the high rates of dyslipidemia among diabetic patients which is believed to be one of the major factors accounting for the high percentage of deaths among diabetics due to cardiovascular disease (CVD).[5]

Several studies[3,4,5,6] showed that the differences in the lipid profile between diabetics (especially type 2 diabetics) and non-diabetics account for the increased CVD risk. Naturally, type 2 DM (T2DM) lipid profiles consist of elevations in triglyceride (TG) levels (>2 mmol/l) and reductions in high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C). While low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) concentration levels are normal, the particles are denser and smaller in size, which is believed to enhance their atherogenic potential.[7] Statins are considered the first line pharmacological treatment of dyslipidemia in diabetic patients.[8] However, various studies reported randomized trials among various ethnicities have documented that rosuvastatin is the most effective statin at reducing LDL-C, TGs, and at raising HDL-C levels.[3,9,10,11] Although, previously atorvastatin was considered best potent in reducing LDL-C before the approval of rosuvastatin.[12]

Very few studies on the effects of statin treatment in altering lipid profiles in patients with the metabolic syndrome is available.[3] The aim of the present study was to determine efficacy, safety, and the cost effectiveness, of the four most commonly prescribed statins in treatment of dyslipidemia among diabetic patients.

Materials and Methods

This is a cohort, observational, population-based study conducted at diabetic clinics of the Hamad Medical Corporation (HMC) and Primary Health Care Centers (PHCC) from January 2007 to September 2013. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) and Medical Research Ethics Committee, HMC RP# 11212/11.

Study Population

A total of 1,542 diabetic patients with dyslipidemia above 18 years of age were included. These patients were prescribed of any of the four statins. The patients were diagnosed as diabetes if their venous blood glucose values were higher than or equal to 7 mmol/l or if they were taking medication for diabetes at the time of the study. All lipid parameters were quantified on samples collected in the fasting state. Cholesterol and TG quantization was determined by enzymatic assay. LDL-C was calculated using the Friedewald equation for patients with TG ≤ 400 mg/dl and measured by b-quantification for those with TG > 400 mg/dl. Levels of non-HDL-C were calculated by subtraction of HDL-C from total cholesterol.

Patient having genetic disorders, history of angina, severe vascular disease, or other life-threatening disease; nephropathy and/or hypothyroidism; or active liver and bile duct diseases were excluded. Patients with creatine kinase (CK) levels >10 of upper limit of normal (ULN); patients taking concurrent corticosteroids, ciclosporin, and/ or hormone replacement therapy; and history of drug or alcohol abuse and pregnant women were also excluded.

Data

A well-designed questionnaire was used to collect the data of the recruited patients retrospectively. The questionnaire included sociodemographic characteristics such as age, gender, nationality, height, weight, and consanguineous marriage. The second part included physical activity and lifestyle habits like smoking and alcohol. The third part included the details of statin prescribed for at least 2 years continuously and dose, type of DM, its duration, and clinical and biochemistry laboratory investigations such as fasting blood glucose, glycated hemoglobin (HbA1C), total cholesterol, HDL and LDL cholesterol levels, and TGs.

The data for these patients were obtained from the electronic medical database called (EMR-viewer) and the patients’ files from the Medical Records Department. Information about the type of statin (rosuvastatin, atorvastatin, pravastatin, and simvastatin) were taken from the pharmacy database. Baseline characteristics of the patients were collected from the database 1 week before the first use of statins. Again after using statins, biochemistry values were collected at 2nd year interval for comparison. Height and weight were measured using standardized method. The body mass index (BMI) was calculated as the weight in kilograms (with 1 kg subtracted to allow for clothing) divided by height in meters squared.

The prescribed doses in HMC and PHCC for diabetic patients with dyslipidemia were as follows:

Atorvastatin 10 mg (n = 150), 20 mg (n = 200), and 40 mg (n = 140); total N = 490

Pravastatin 20 mg (n = 174) and 40 mg (n = 160); total N = 274

Rosuvastatin 10 mg (n = 300) and 20 mg (n = 222); total N = 522

Simvastatin 20 mg; N = 196

Student's t-test was used to ascertain the significance of differences between mean values of two continuous variables and confirmed by nonparametric Mann-Whitney test. Chi-square and Fisher's exact tests (two-tailed) were performed to test for differences in proportions of categorical variables between two or more groups. Nonparametric statistical method, the Kruskal-Wallis one-way analysis of variance was performed to evaluate differences among different characteristics group. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

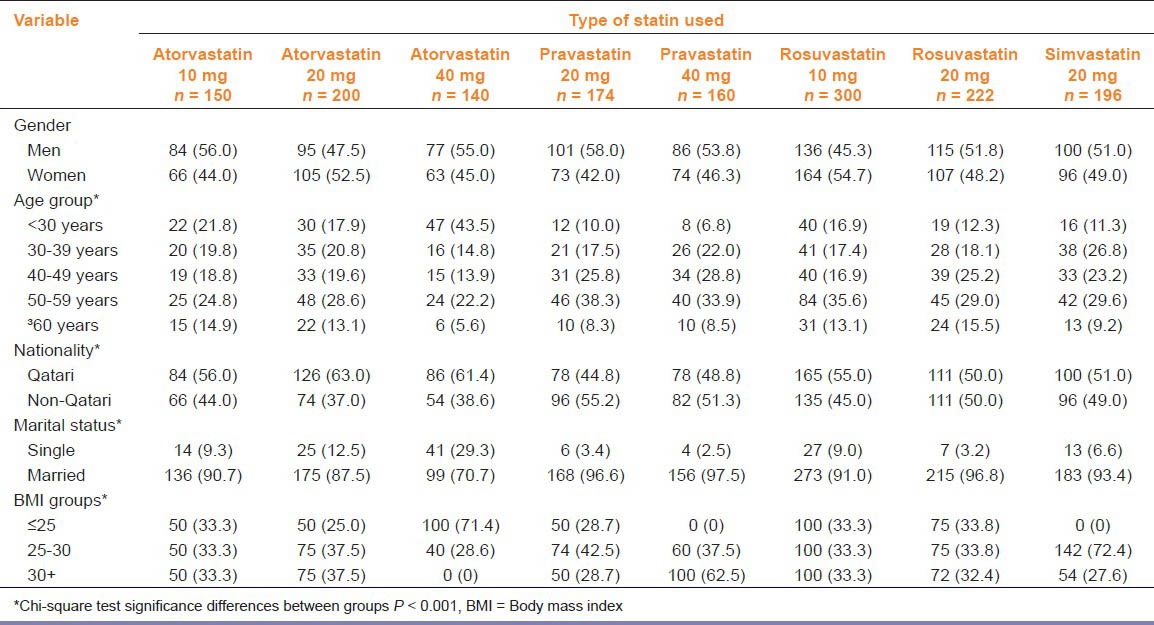

The socio-demographic characteristics of the study population is shown in Table 1. The majority of patients were Qatari, men, married, and had a BMI > 30 kg/m2 (P < 0.001).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of study population (n = 1,542)

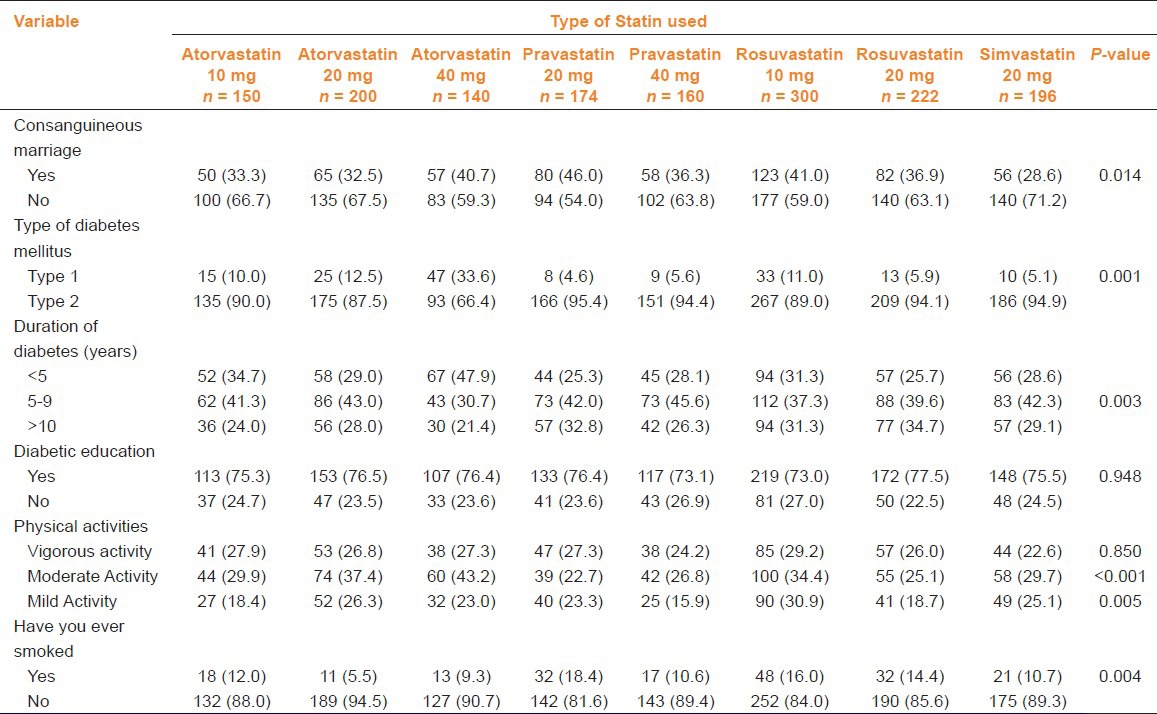

Table 2 gives clinical characteristics of the studied subjects by type of statin used. The majority had T2DM, duration of diabetes between 5 and 9 years; also, had diabetic education and moderate physical activity.

Table 2.

Clinical characteristics of patients as per statin used (n = 1,542)

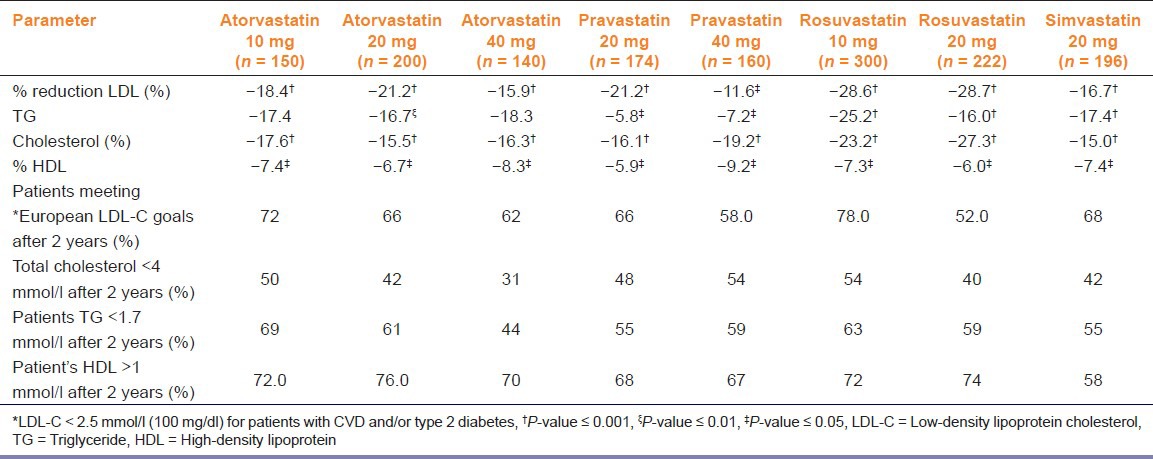

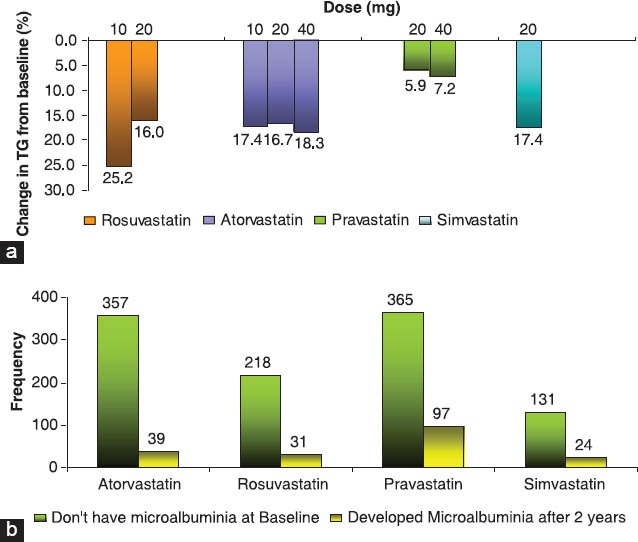

Comparison of the efficacy of each statin at each dose is shown in Table 3 and Figure 1a. Rosuvastatin (10 and 20 mg) was the most effective in reducing LDL-C (28.6 and 28.6%, respectively). Atorvastatin reduced LDL-C (P < 0.001) the most at a dose of 40 mg (15.9%) and pravastatin reduced LDL-C the most at a dose of 20 mg (21.2%). Moreover, rosuvastatin (10 mg) reduced TGs the most (-25.17%; P < 0.001). Further, it was observed that all of the statins reduced rather than raised HDL-C levels.

Table 3.

Comparison of the efficacy of various statins in different doses (10, 20, and 40 mg)

Figure 1.

(a) Rosuvastatin versus other statins, (b) Comparison of patients with pre-and posttreatment microalbuminuria at the end of 2 years

The percentage of patients with newly onset microalbuminuria was least with atorvastatin at the end of 2 years treatment (39, 10.9%) followed by rosuvastatin (31, 14.2%), pravastatin (97, 26.6%), and by simvastatin (24, 18.3%) [Figure 1b]. However, no case of microalbuminuria progressed to the more dangerous macroalbuminuria. No patients presented with Alanine Aminotransferase (ALT) > 3 × ULN or CK > 10 × ULN.

Furthermore, cost-effectiveness of statin showed that the yearly acquisition costs was lower for rosuvastatin 10 mg as compared to atorvastatin 20 mg (€758 Euro vs € 962 Euro) This was consistent and confirmative with the Western countries in both the US ($959.95 vs $1,204.50) and the UK (£235.03 vs £321.20).[13] Moreover, rosuvastatin 10 mg was more effective at a low cost than atorvastatin 20 mg both in terms of LDL-C reduction and achieving National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) ATP III or 2003 European LDL-C goals.

Discussion

The present study aims to build on this growing awareness of atherosclerosis-specific care of diabetes patients, by examining efficacy and safety of the four most commonly prescribed statins in the State of Qatar. The Middle East region is predicted to have one of the highest prevalence of T2DM in the world. However, data is lacking regarding the cost effectiveness, efficacy, and safety of the four most commonly prescribed statins (rosuvastatin, atorvastatin, pravastatin, and simvastatin) for managing dyslipidemia among diabetic patients.[8] In the current study, rosuvastatin (10 and 20 mg) was found to be the most effective statin at reducing LDL-C when compared with atorvastatin (10, 20, and 40 mg), pravastatin (20 and 40 mg), and simvastatin (20 mg). The present study is consistent with the previous reported studies[6,7,8,9,11,14,15] that rosuvastatin at its lowest dose in this study (10 mg) was more effective at reducing LDL-C levels than atorvastatin and pravastatin at their highest doses (40 mg). Indeed, it should be noted that rosuvastatin which is the latest statin to receive approved labeling by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA),[11] has been consistently found to be the most effective at reducing LDL-C levels in the most recent studies comparing its efficacy to other statins.[15] The present study revealed and confirmed that rosuvastatin is the most effective statin at reducing LDL-C, TGs, and total cholesterol, at the lowest dose (10 mg). Moreover, it reduced HDL-C the least in comparison to the other statins.

Measuring effective reductions in cholesterol using rosuvastatin therapy (MERCURY) trial,[3,15] Statin Therapies for Elevated Lipid Levels compared Across doses to Rosuvastatin (STELLAR) trial,[9,11,14] and Prospective study to evaluate the Use of Low doses of the Statins Atorvastatin and Rosuvastatin (PULSAR)[15] are the major open-label, randomized, multicenter trials to compare rosuvastatin (10, 20, 40, or 80 mg) with atorvastatin (10, 20, 40, or 80 mg), pravastatin (10, 20, or 40 mg), and simvastatin (10, 20, 40, or 80 mg) across dose ranges for reduction of LDL-C.[11] The results of the STELLAR trial revealed that rosuvastatin was consistently, across all doses, the most effective at reducing LDL-C levels in comparison to all of the other statins. The MERCURY[3,15] and STELLAR studies[9,11,14] reported that rosuvastatin 10 mg therapy is effective in allowing LDL-C goal achievement and improving the lipid profile in hypercholesterolemic and high-risk diabetic patients. This is confirmative with the current study performed in Qatar.

Although despite the proven benefits of LDL-C reduction, lipid management is suboptimal and many patients fail to achieve recommended LDL-C goals.[16,17,18] The most likely reason for this is the use of agents with a poor efficacy for LDL-C lowering and suboptimal dose titration. The most effective statin at the lowest dose would represent a simple, effective treatment strategy, enabling more patients to achieve goals without the need for dose titration.[15]

It has been reported by several studies[5,10,14] that the lowering of TGs is another important goal in reducing CVD risk among diabetic patients. In the current study, the greatest reduction in TGs (-25.17%; P < 0.001) was achieved by rosuvastatin (10 mg). Similar observations were made with high doses of rosuvastatin (20 mg) and atorvastatin (20 and 40 mg) and pravastatin (20 and 40 mg). However, it is important to note that atorvastatin (10, 20, and 40 mg) achieved the second highest reduction in TGs (-17.4%, P = not significant (NS); -16.7%, P < 0.01; and -18.3%, P = NS; respectively). These findings are similar to the existing literature.[3,14,9,11,14,15] Thus, it can be stated that rosuvastatin and atorvastatin are equally effective in reducing serum TGs.

Additionally, in most cases raising HDL-C levels is another major factor known to reduce CVD risk as reported by some studies.[7] In the current study, all of the statins appear to have reduced rather than raised HDL-C levels. Rosuvastatin (20 mg) had the least reduction of (-4.0%) and would thus be regarded as the most effective; however, none of the values for the statins were significant. The current study is consistent with the previous studies and trials that MERCURY trial,[3,15] STELLAR trial,[9,11,13,15] and PULSAR[15] study which investigated starting doses of rosuvastatin and atorvastatin, found that the increase in HDL-C was significantly greater statistically with rosuvastatin (10 mg) than with atorvastatin (20 mg).

Further, more recently VOYAGER database study[7] investigated the effects of different statins on HDL-C levels, relationships between changes in HDL-C and changes in LDL-C, and meta-analysis of 32,258 dyslipidemic patients included in 37 randomized studies using rosuvastatin, atorvastatin, and simvastatin. The HDL-C raising ability of rosuvastatin and simvastatin was comparable, with both being superior to atorvastatin. Increases in HDL-C were positively related to statin dose with rosuvastatin and simvastatin, but inversely related to dose with atorvastatin. The analysis also revealed that the HDL-C raising achieved by all three statins was totally independent of the reduction in LDL-C. And finally, it has been found that baseline concentrations of HDL-C and plasma TG and the presence of diabetes are robust, independent predictors of statin-induced elevations of HDL-C.[7,10]

Meanwhile, it seems that a number of factors could explain the discrepancy between the current study's results and existing literature. It is evident in the present study, patient characteristics had more than two risk factors for CVD like they were diabetic, and above 50 years age, and history of hypertension. In addition, over two-thirds of the patients were obese and Qatari. In other diabetic research studies conducted in Qatar, it was found that having Qatari ethnicity was correlated with poor lifestyle habits such as sedentary lifestyle and poor eating choices.[2]

Also, one of the most common complaints related to statin use is related to the effect of statins on muscular function. Muscle symptoms range from myalgia which includes muscle pain without CK elevations, to myositis which is muscle symptoms with CK elevations.[14] In general, elevations of CK > 10 × ULN are regarded as significant elevations justifying the discontinuation of statin treatment. In the current study, there were no cases of elevations of CK level > 10 × ULN, which all statins used, irrespective of dose, were regarded as safe in terms of myositis.

Hepatic function is also known to be affected by statin use.[14] This is mainly measured by asymptomatic elevations of the liver enzymes ALT and aspartate aminotransferase (AST), otherwise known as transaminitis.[13] In the current study, no patients had elevated ALT > 3 × ULN. Although, the incidence of hepatic failure in patients taking statins appears to be no different from that in the general population.[13]

The present study did not significantly affect the serum creatinine and glomerular filtration rate (GFR) after 2 years. In addition, the three statins appeared to be relatively safe for patients with microalbuminuria at baseline, as the number of those whose microalbuminuria increased was very minimal. In fact, pravastatin (40 mg) appeared to reduce the number of patients with baseline microalbuminuria. On the other hand, in patients without baseline microalbuminuria, there appeared to be relatively significant onset of microalbuminuria in patients taking pravastatin (22.6%), simvastatin (20.9%), and to a lesser degree rosuvastatin (10.7%) and atorvastatin (8.8%).

More recently, study[3,14] showed that patients with the metabolic syndrome had greater reductions in TGs and somewhat greater percentage increases in HDL-C with statin treatment, as expected. The comparisons between statin treatment groups showed consistent advantages to rosuvastatin 10 mg treatment in LDL-C goal achievement and in LDL-C, total cholesterol, and non-HDL-C reduction. It is worth noting that a pharmacoeconomic analysis of the primary MERCURY results[3,14] showed that treatment with rosuvastatin 10 mg was more cost-effective, compared to equivalent or higher doses of atorvastatin, simvastatin, and pravastatin; and that switching patients from a comparator statin to rosuvastatin improved LDL-C goal attainment at relatively little additional cost, with equivalent (or lower) associated drug costs.[3,13] Thus, rosuvastatin 10 mg may have pharmacoeconomic advantages, compared to atorvastatin 20 mg, while providing comparable efficacy.

Conclusion

The present study revealed that statin therapy is effective in allowing LDL-C goal achievement and improving the lipid profile in hypercholesterolemic and high-risk diabetic patients. Rosuvastatin 10 mg was the most effective statin in reducing LDL-C, TGs, and total cholesterol in dyslipidemic diabetic patients.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared

References

- 1.Wild S, Roglic G, Green A, Sicree R, King H. Global prevalence of diabetes: Estimates for the year 2000 and projections for 2030. Diab Care. 2004;27:1047–53. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.5.1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bener A, Zirie M, Janahi IM, Al-Hamaq AO, Musallam M, Wareham NJ. Prevalence of diagnosed and undiagnosed diabetes mellitus and its risk factors in a population-based study of Qatar. Diabetes Res Clin Prac. 2009;84:99–106. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2009.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stender S, Schuster H, Barter P, Watkins C, Kallend D MERCURY I Study Group. Comparison of rosuvastatin with atorvastatin, simvastatin and pravastatin in achieving cholesterol goals and improving plasma lipids in hypercholesterolaemic patients with or without the metabolic syndrome in the MERCURY I trial. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2005;7:430–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2004.00450.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults. Executive summary of the third report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) JAMA. 2001;285:2486–97. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.19.2486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brunzell JD, Davidson M, Furberg CD, Goldberg RB, Howard BV, Stein JH, et al. American Diabetes Association; American College of Cardiology Foundation. Lipoprotein management in patients with cardiometabolic risk: Consensus statement from the American Diabetes Association and the American College of Cardiology Foundation. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:811–22. doi: 10.2337/dc08-9018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McKenny JM. Efficacy and safety of rosuvastatin in treatment of dyslipidemia. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2005;62:1033–47. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/62.10.1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barter PJ, Brandrup-Wognsen G, Palmer MK, Nicholls SJ. Effect of statins on HDL-C: A complex process unrelated to changes in LDL-C: Analysis of the VOYAGER Database. J Lipid Res. 2010;51:1546–53. doi: 10.1194/jlr.P002816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barakat L, Jayyousi A, Bener A, Zuby B, Zirie M. Comparison of efficacy and safety of Rosuvastatin, Atorvastatin and Pravastatin among dyslipidemic diabetic patients. ISRN Pharmacol 2013. 2013 doi: 10.1155/2013/146579. 146579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jones PH, Davidson MH, Stein EA, Bays HE, McKenney JM, Miller E, et al. STELLAR Study Group. Comparison of the efficacy and safety of rosuvastatin versus atorvastatin, simvastatin, and pravastatin across doses (STELLAR* Trial) Am J Cardiol. 2003;92:152–60. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(03)00530-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Palmer MK, Nicholls SJ, Lundman P, Barter PJ, Karlson BW. Achievement of LDL-C goals depends on baseline LDL-C and choice and dose of statin: An analysis from the VOYAGER database. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2013;20:1087–7. doi: 10.1177/2047487313489875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McKenney JM, Jones PH, Adamczyk MA, Cain VA, Bryzinski BS, Blasetto JW STELLAR Study Group. Comparison of the efficacy of rosuvastatin versus atorvastatin, simvastatin, and pravastatin in achieving lipid goals: Results from the STELLAR trial. Curr Med Res Opin. 2003;19:689–98. doi: 10.1185/030079903125002405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brown AS, Bakker-Arkema RG, Yellen L, Henley RW, Jr, Guthrie R, Campbell CF, et al. Treating patients with documented atherosclerosis to National Cholesterol Education Program-recommended low-density-lipoprotein cholesterol goals with atorvastatin, fluvastatin, lovastatin and simvastatin. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998;32:665–72. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(98)00300-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Björnsson E, Jacobsen EI, Kalaitzakis E. Hepatotoxicity associated with statins: Reports of idiosyncratic liver injury post-marketing. J Hepatol. 2012;56:374–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schuster H, Barter PJ, Stender S, Cheung RC, Bonnet J, Morrell JM, et al. Effective Reductions in Cholesterol Using Rosuvastatin Therapy I study group. Effects of switching statins on achievement of lipid goals: Measuring Effective Reductions In Cholesterol Using Rosuvastatin Therapy (MERCURY I) study. Am Heart J. 2004;147:705–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2003.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clearfield MB, Amerena J, Bassand JP, Hernández García HR, Miller SS, Sosef FF, et al. Comparison of the efficacy and safety of rosuvastatin 10 mg and atorvastatin 20 mg in high-risk patients with hypercholesterolemia — Prospective study to evaluate the Use of Low doses of the Statins Atorvastatin and Rosuvastatin (PULSAR) Trials. 2006;7:35. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-7-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Foley KA, Simpson RJ, Jr, Crouse JR, 3rd, Weiss TW, Markson LE, Alexander CM. Effectiveness of statin titration on low-density lipoprotein cholesterol goal attainment in patients at high risk of atherogenic events. Am J Cardiol. 2003;92:79–81. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(03)00474-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pearson TA, Laurora I, Chu H, Kafonek S. The lipid treatment assessment project (L-TAP): A multicenter survey to evaluate the percentages of dyslipidemic patients receiving lipid-lowering therapy and achieving low-density lipoprotein cholesterol goals. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:459–67. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.4.459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gandhi SK, Jensen MM, Fox KM, Smolen L, Olsson AG, Paulsson T. Cost-effectiveness of rosuvastatin in comparison with generic atorvastatin and simvastatin in a Swedish population at high risk of cardiovascular events. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res. 2012;4:1–11. doi: 10.2147/CEOR.S26621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]