SUMMARY

Pediatric gliomas are a heterogeneous group of diseases, ranging from relatively benign pilocytic astrocytomas with >90% 5-year survival, to glioblastomas and diffuse intrinsic pontine gliomas with <20% 5-year survival. Chemotherapy plays an important role in the management of these tumors, particularly in low-grade gliomas, but many high-grade tumors are resistant to chemotherapy. A major obstacle and contributor to this resistance is the blood–brain barrier, which protects the CNS by limiting entry of potential toxins, including chemotherapeutic agents. Several novel delivery approaches that circumvent the blood–brain barrier have been developed, including some currently in clinical trials. This review describes several of these novel approaches to improve delivery of chemotherapeutic agents to their site of action at the tumor, in attempts to improve their efficacy and the prognosis of children with this disease.

Practice Points.

The role of chemotherapy for pediatric glioma depends on tumor type.

Chemotherapy efficacy in pediatric gliomas differs from that in adult gliomas.

A major limitation to chemotherapy is getting enough active drug delivered to the tumor site.

The blood–brain barrier limits delivery of agents to the CNS.

Local delivery of chemotherapy directly to the tumor can bypass the blood–brain barrier, but efficacy and risk–benefit analyses are ongoing.

Gliomas are the most common pediatric CNS tumor. These tumors are heterogeneous and, in contrast to adults, the majority are low-grade astrocytomas. However, high-grade gliomas and diffuse intrinsic pontine gliomas (DIPG) represent a significant proportion and are a leading cause of cancer-related death in children. Treatment approaches differ according to tumor grade. For children with low-grade gliomas, complete surgical resection is the treatment of choice. Chemotherapy is generally used in cases of incomplete resection and has been demonstrated to be efficacious [1,2]. By contrast, the mainstay of therapy for children with malignant gliomas involves a multidisciplinary approach with surgical resection, radiation therapy and chemotherapy. However, the role of chemotherapy in this population is unclear [3–6]. Most physicians incorporate some form of adjuvant chemotherapy, although no standard of care exists [7]. For DIPG, radiation therapy is the standard treatment; although many receive chemotherapy despite the lack of any demonstrated efficacy [8].

While in vitro evidence suggests that chemotherapy is capable of killing malignant glioma cells [9], in vivo activity is hindered by limited drug delivery to its active site. For an agent to be effective, it must reach its target in its active form (free and unbound), in adequate concentrations and for long enough periods of time (i.e., have adequate exposure) (Box 1). Delivery of systemically administered agents to a CNS tumor site is primarily hindered by the blood–brain barrier (BBB), although the blood–tumor barrier, abnormal tumor vasculature, increased interstitial pressure and secondary effects of the tumor such as edema and cyst formation also play roles [10,11].

Box 1. . Factors affecting drug exposure at the tumor site.

Concentration of drug in the bloodstream

Protein and tissue binding (free, unbound drug)

Blood–brain barrier

Rate of blood flow to the tumor

Diffusion of drug across the brain parenchyma

Drug metabolism

The BBB is comprised of a neurovascular unit, which includes a single layer of specialized capillary endothelial cells lining brain microvessels, and associated neighboring cells, including pericytes, astrocytes and microglia [11]. The capillary endothelial cells of the BBB differ from those outside the CNS in that they have extended tight junctions, lack fenestrations, lack pinocytotic vesicles and express specific transport mediators. Consequently, diffusion of large and/or water-soluble substances does not occur unless specific transporters are present. With the protective mechanisms of the BBB intact, nearly all systemically administered agents, especially hydrophilic or high-molecular weight drugs, fail to penetrate the BBB effectively. In CNS tumors with evidence of BBB disruption (as indicated by contrast enhancement on MRI), drug penetration is inadequate because malignant invasive tumor cells extend beyond the areas of enhancement. Attempts at improving drug delivery to the tumor site have focused on overcoming the BBB, utilizing a number of strategies including systemic administration of high-dose chemotherapy, identification of drugs that penetrate the BBB, rationally synthesized drugs, disruption of the BBB and regional chemotherapy. For pediatric supratentorial malignant gliomas, CNS dissemination to distant sites is relatively uncommon and local delivery is justifiable. For children with DIPG, dissemination throughout the CNS at some point within the disease course is not uncommon [12], and spinal dissemination should be ruled out prior to proceeding with local delivery options as local delivery will probably not control metastatic disease. This review will focus on novel regional delivery techniques under, or close to, clinical investigation in children with malignant gliomas.

Regional drug delivery is a pharmacokinetic approach to increase a drug's therapeutic index by delivering the agent directly to its site of action. With any type of regional drug delivery, the pharmacologic advantage results from the first passage of the drug through the target site. As higher drug concentrations are achieved at the target site, lower doses can be administered, resulting in potentially less systemic toxicity. Once the drug reaches the systemic circulation it follows intravenous distribution [13].

Intra-arterial delivery

Intra-arterial delivery of chemotherapeutic agents has been studied over the past 50 years. Although associated with a survival benefit for patients with retinoblastoma and hepatic tumors [14,15], the utility of intra-arterial delivery for malignant gliomas remains uncertain despite evidence that tumor exposure is higher compared with nontarget tissue [13]. For example, an early study in rodent xenograft models demonstrated that intra-arterial melphalan increased intratumoral tissue concentrations by fourfold and surrounding tissue concentrations by up to 20-fold compared with intravenous delivery [16]. Ideal agents for intra-arterial delivery include lipophilic agents (enough drug must be delivered to the tissue at first passage) in their active form, and the major pharmacologic advantage is achieved during the first passage of the drug through the tissue being supplied by the selected infused artery. Circulation (blood flow and blood volume), blood–tissue exchange and pharmacology of the selected agent influence the overall pharmacologic benefit of intra-arterial delivery [13].

Intra-arterial delivery is performed either alone or in conjunction with hyperosmolar BBB disruption using mannitol [17], and leads to augmented local peak drug concentrations and exposure [18]. Typically, the carotid or vertebral artery is cannulated and the catheter tip advanced into specific branches feeding the tumor [19]. Nitrosoureas and platinum compounds were the initial agents studied using this approach. While early studies suggested that intra-arterial 1,3-bis(2-chloroethyl)-1-nitrosourea (BCNU) may be beneficial, subsequent studies revealed severe neurotoxicity [20,21]. A randomized Phase III trial comparing intra-arterial versus intravenous BCNU demonstrated that intra-arterial BCNU was neither safe nor effective [20,21]. Patients on the intra-arterial arm had a 9.5% incidence of fatal leukoencephalopathy and a shorter survival (11.2 vs 14.0 months) compared with those treated intravenously [15]. A Phase III study comparing intra-arterial versus intravenous administration of ACNU, a nitrosourea with fewer expected side effects, in 43 adults with newly diagnosed supratentorial glioblastoma showed no statistical difference in median time to progression (6 vs 4 months) or survival (17 vs 20 months, respectively) [22]. Intra-arterial administration of platinum compounds was better tolerated with less neurotoxicity and some evidence of efficacy [23,24]. However, a randomized Phase III trial comparing intra-arterial cisplatin with intravenous PCNU in patients with recurrent disease reported shorter survival as well as a 7.2% incidence of ocular toxicities in the intra-arterial arm [25].

As mentioned, a major issue with intra-arterial delivery is technique-related side effects. Following intra-arterial administration, there is nonuniform drug distribution within the brain, poor mixing and a streaming effect [26], resulting in areas with high, potentially toxic concentrations and areas with low, subtherapeutic concentrations. Establishing safe dosing based on intracarotid administration may not be appropriate for posterior fossa tumors. In adults, most tumors are supratentorial and supplied by the carotids, which are diverging vessels. In children, ≥50% of tumors are infratentorial and supplied by the vertebrobasilar arteries, which are converging. Flow mechanics, drug mixing and tissue distribution can differ significantly [26]. More recently, a selective intra-arterial cerebral infusion technique specifically targeting tumor vessels has been employed. This has advantages over carotid or vertebral artery infusions because the drug is delivered specifically to the tumor area, avoiding normal tissue and potentially reducing neurotoxicity [27]. However, a recent study reported that only 6% of patients with glioblastoma have a single vessel supplying the tumor [28]. The selective intra-arterial technique has been performed in concert with selective infusion of mannitol; although permeability of the BBB is increased, disruption is nonspecific. Normal brain tissue (with intact BBB) may have a higher increase in disruption compared with tumor tissue (with an already partially disrupted BBB) [29].

Very few intra-arterial studies for administration of chemotherapeutic agents to children with brain tumors have been performed. Dahlborg et al. reported on their institutional experience of 34 children with nonglial tumors who were treated with intra-arterial administered carboplatin or methotrexate, along with osmotic disruption of the BBB [30]. They reported no mortality after 645 procedures (range: 2–58 per patient; mean: 19; median: 21) in this group, with a 4% incidence of seizures, and objective responses in 82% of patients. In a report of four patients with brainstem glioma treated with intravertebral artery infusion of ACNU, cisplatin or carboplatin, concurrently with oral etoposide and intravenous IFN-β after initial radiation therapy, patients tolerated the infusions well with no neurotoxicity [31]. Two complete responses and two partial responses were reported. The patients included two pediatric patients (aged 5 and 18 years) who had biopsies demonstrating low-grade glioma (survival: 36 and 15 months, respectively), and two adult patients (aged 59 and 39 years) who had biopsies demonstrating malignant astrocytoma and well-differentiated glial tumor, respectively (survival: 14 and more than 24 months, respectively). Although the tolerability of intravertebral drug administration is of interest, it is important to note that none of these patients had a typical DIPG. A clinical trial evaluating the feasibility and efficacy of intra-arterial melphalan in children with progressive DIPG is currently underway.

In summary, intra-arterial delivery of chemotherapeutic agents has a pharmacologic advantage in that more drug is delivered to the tumor site during the first passage, but assessing safety and efficacy is difficult given variability in drug doses, administration techniques, response assessment, study design and tumor characteristics. In experienced hands, intra-arterial delivery for CNS tumors appears to be relatively safe; although vascular and neurologic side effects have limited routine expansion to the clinic. Definitive clinical benefit in comparison to intravenous therapy for the treatment of recurrent malignant gliomas has not been clearly demonstrated, and no trial demonstrating safety and efficacy in pediatric glioma has been reported. Currently, the role of intra-arterial therapy for pediatric glioma remains limited to investigational trials.

Direct intratumoral/intracavitary placement

Placement of chemotherapeutic agents directly at the tumor site has been executed using a number of techniques. These have taken the form of direct injection into the surgical bed and resected margins, or placement of wafers, gels, micro- and nano-carrier systems, beads, spheres and microchips. While the pharmacological advantage is circumvention of the BBB, dispersion of drug beyond the site of infusion/placement is based on the principles of diffusion.

Drug-impregnated polymers placed in a surgical cavity are able to achieve high local concentrations of the drug. Initial studies were performed using nonbiodegradable wafers but the rate of drug release from the wafer was inconsistent and decreased over time [32]. Development of biodegradable polymers that allow sustained release of drugs via surface erosion created a resurgence of interest in this technique [32]. Preclinical and clinical studies have demonstrated that biodegradable polymers impregnated with drugs such as 1,3- BCNU allow local sustained release, prolonged local exposure, minimal systemic exposure and improved survival [33–35].

Preclinical and clinical investigations of local delivery to supratentorial malignant gliomas utilizing a BCNU-loaded wafer have led to US FDA approval of Gliadel® (Arbor Pharmaceuticals, GA, USA). These wafers contain 7.7 mg of carmustine within a biodegradable polymer, are generally implanted at the time of surgical resection and are capable of delivering BCNU in a controlled-release manner for 3–6 weeks [34]. In a randomized, placebo-controlled study in adults with recurrent malignant gliomas requiring reoperation, patients were randomized to receive surgically implanted biodegradable discs with or without 3.85% carmustine [36]. The group receiving the carmustine had a longer median survival (31 vs 23 weeks) and 6 month survival was 56 vs 47%, respectively (p = 0.061) [32,36,37]. Subsequent studies demonstrated a modest but significant benefit for patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma [38]. Toxicities and complications particularly at higher dose levels include wound healing, cerebrospinal fluid leaks, seizures, intracranial hypertension, edema, treatment-related necrosis, cyst formation and infection [32,37,39].

Studies combining polymers with radiation therapy and chemotherapeutic agents have demonstrated potential efficacy. In a study involving 92 adults with newly diagnosed malignant glioma (80% of patients had glioblastoma) treated with surgical resection, implantation of Gliadel wafers, followed by chemoradiotherapy with temozolomide, progression-free survival was 10.5 months and overall survival was 18 months [40], which compared favorably with historical controls. Similar results, including an overall survival of 19 months, were reported in a study of 24 adults with glioblastoma [41].

As with other local delivery methods that rely on diffusion, one disadvantage of wafers is limited diffusion across tissue [42]. Initial studies performed in rabbits utilizing radiolabeled techniques indicated that BCNU could be distributed up to 12 mm from the wafer [43], but subsequent pharmacokinetic studies in nonhuman primates showed significant decrease in exposure over distance and time. BCNU concentration measured 3 mm from the site of implantation was less than a third of that at the implantation site; within 1 week, only the site within 0.5 mm of implant had significant concentrations [44].

Although promising, the results of these clinical trials are not clearly interpretable. Survival benefits are relatively modest and adverse events more frequent. The more recent studies appear matched in their control arms, but combine multiple therapies, making the added benefit of Gliadel difficult to interpret. Although there appears to be a role for Gliadel, no study has reported on its safety and efficacy in children with gliomas.

Convection-enhanced delivery

CNS delivery techniques including intrathecal or intraventricular administration and polymer implantation, are diffusion dependent and limited by nontargeted distribution, inhomogeneous dispersion and ineffective volumes of distribution. Diffusion of a compound depends on compound-specific factors, such as the diffusion coefficient and free drug concentration gradient [45]. By contrast, convection or bulk flow of an agent depends on pressure gradients. Initial investigations showed that maintaining a positive pressure gradient during infusion to brain tissue establishes convection of the fluid within the brain and results in enhanced distribution of both small and large molecules, including high-molecular weight proteins [45].

Convection-enhanced delivery (CED) is a means to improve delivery and distribution of molecules to targeted sites within the CNS. Successful convection of fluids in the brain is dependent on the infusion rate; rates that are too low result in diffusion-mediated dispersion, while rates that are too high result in leakage back through the cannula track. Distribution of the convected agent also depends on its pharmacologic properties, such as half-life and surface-binding properties, as well as anatomic features, such as anisotropy [46]. Initial agents administered via CED for clinical use were immunotoxins such as diphtheria toxin conjugated to transferrin (TF-CRM107) and the pseudomonas exotoxin conjugated to human IL13-PE38QQR (cintredekin besudotox) [47], while subsequent trials have used nonspecific agents such as topotecan [48].

CED has been performed for delivery to both supratentorial tumors and brainstem tumors including DIPG [49]. Preclinical and early clinical trials of CED for the treatment of malignant gliomas have demonstrated feasibility, safety and lack of systemic toxicity [49–52]. Efficacy have been mixed. A Phase I study of topotecan administered via CED to patients with recurrent glioblastoma demonstrated tumor regression in more than two-thirds of patients and minimal drug-related systemic toxicity [48]. A large Phase III trial comparing CED of cintredekin besudotox versus placement of Gliadel wafers was performed in adults with glioblastoma at the time of first recurrence [53]. Two hundred and ninety six patients, balanced for demographic and baseline characteristics, were randomized. Median survival between the two groups was not statistically significant (9.1 vs 8.8 months, respectively). The efficacy of CED for the treatment of malignant gliomas continues to be evaluated and several clinical trials assessing safety and efficacy of different agents at different points in the disease course of children with supratentorial or brainstem tumors are ongoing.

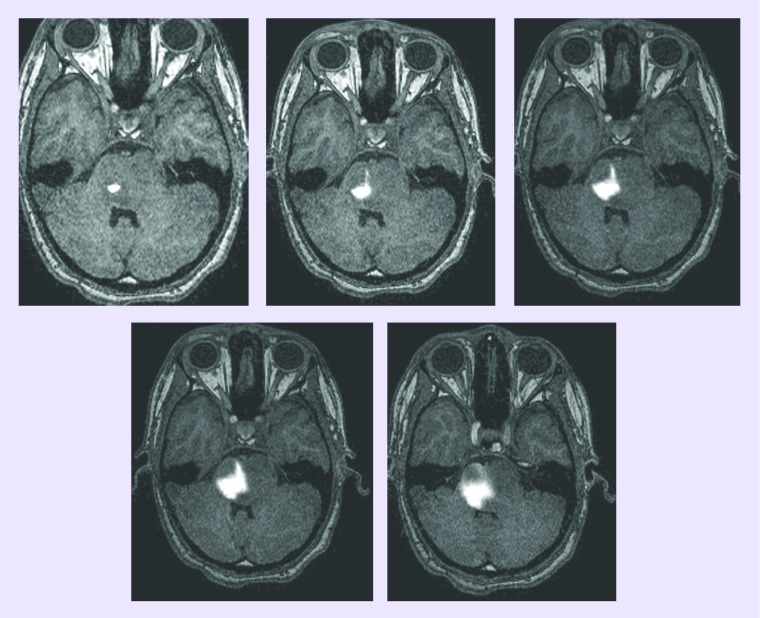

Not all CED studies incorporate analysis of drug distribution, which is an important consideration when determining efficacy. Image analyses of pediatric patients with DIPG suggest some efficacy in the area of the tumor infused with the drug [Warren KE, Unpublished Data]; although tumor progression in untreated areas masked potential efficacy. Drug distribution analysis can be performed by coinfusing a surrogate tracer (gadolinium-DTPA) and monitoring its distribution by MRI. Preclinical and clinical studies have shown that use of gadolinium-DTPA, a widely used and US FDA-approved intravenous contrast agent, helps ensure that the target region is exposed to the agent while minimizing exposure of normal CNS tissues [49,54]. Real-time MRI of CED assists in defining factors such as infusion rate, the relationship between volume infused and distribution that influence convective distribution and give direct insight into the safety/efficacy of CED of putative therapeutic agents [49,55]. Conclusions about efficacy will require continued clinical investigations that take into account identification of tumor and drug distribution (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Axial T1-weighted MRI images acquired at various time points over the course of a single Il13-PE338QQR infusion in a child with diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma.

Note increasing distribution of enhanced areas corresponding to drug infusion, demonstrating the ability to follow a convection-enhanced delivery infusion.

Intranasal drug delivery

Intranasal administration has been widely used as a means to deliver drugs for local internasal and systemic applications in noncancer settings. Recently, intranasal delivery has been studied as a means to carry agents directly to the CNS for treatment of dementia and neurological disorders, and is being investigated as a means to bypass the BBB for chemotherapeutic delivery. The nasal mucosa is particularly suited because of its high blood flow and a direct connection to the CNS via olfactory cells [56,57]. Ideal agents for intranasal delivery include those with increasing partition coefficients [58].

The nasal mucosa consists of the highly vascularized respiratory epithelium, covering most of the nasal concha, and the olfactory mucosa, located on the roof of the nasal cavity [57]. Drugs administered intranasally can enter the CNS in a number of ways, including absorption by the respiratory epithelium and entry into the systemic circulation, and via vascular, lymphatic, cerebrospinal fluid and neural mechanisms [59,60]. Drugs may be directly transported along cranial nerve pathways as the maxillary and ophthalmic branches of the trigeminal cranial nerve innervate the nasal mucosa and link the nasal passages with the brainstem [61]. This direct connection between the nasal mucosa and the CNS allows direct delivery of substances [62]; there is a great deal of interest in this means of delivery for children with DIPG.

Preclinical studies have documented entry of biologic and chemotherapeutic compounds into the CNS of animal models after intranasal drug delivery [59,61,63–66]. The telomerase inhibitor GRN163 was administered intranasally to rats bearing intracerebral human glioblastoma xenografts implanted within the basal ganglia [66]. Intranasally delivered GRN163 preferentially accumulated within the tumors and survival was significantly prolonged compared with the control group (median survival: 75.5 vs 35 days, p < 0.01).

Very few clinical trials using intranasal chemotherapeutic drug delivery have been reported and none have been performed for children; although the technique appears promising. In a Phase II trial, the Ras inhibitor, perillyl alcohol, was administered intranasally to 67 adults with recurrent malignant glioma [67]. Interestingly, those patients with deep midline tumors (11 glioblastoma and two anaplastic astrocytoma) had a longer survival than those with cortical lesions (p = 0.0093). A number of issues need to be addressed to adequately design a pediatric clinical trial and assess intranasal drug delivery of chemotherapeutic agents. Although preclinical studies in rodent and nonhuman primate models have demonstrated that intranasal delivery of agents leads to increased CNS delivery, the nasal mucosa of these animals has a larger proportion of olfactory mucosa than humans, in whom the olfactory region makes up approximately 10% of the surface area of the nasal cavity [58]. In addition, we need to determine how to identify the olfactory mucosa, develop a technique for directed administration to that area and create a formulation that will enhance brain targeting.

Conclusion

Malignant gliomas continue to be a leading cause of cancer death in children and little, if any, progress has been made in the past few decades. These tumors are not responsive to chemotherapeutic agents, and a major reason for their lack of efficacy is poor drug delivery. A number of alternate delivery techniques applicable to pediatric patients are under clinical investigation, and several others, such as focused ultrasound and drug-loaded nanoparticle delivery, are under early investigation. It is imperative that techniques are safe and efficacious, that preclinical and clinical study designs be sound, and that children with malignant gliomas be included in early investigational trials as their tumor location and biology differ from adults, and anatomic and developmental characteristics may have an effect on the pharmacokinetics of administered agents.

Future perspective

Future clinical trials for pediatric gliomas will probably be rationally guided by more comprehensive preclinical in vivo pharmacologic testing of new agents to determine CNS penetration of agents. If it is determined preclinically that agents do not adequately penetrate the BBB, alternate delivery methods, such as those outlined here, may be used. The method of delivery chosen must always take into consideration the risk:benefit ratio for the patient. Higher risk procedures, such as CED and intra-arterial delivery methods, will probably be limited to children with high-grade gliomas while less risky procedures, such as intranasal delivery, may play a key role in both high- and low-grade gliomas.

Footnotes

Financial & competing interests disclosure

The author has no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

References

- 1.Ater J, Zhou T, Holmes E, et al. Randomized study of two chemotherapy regimens for treatment of low-grade glioma in young children: a report from the Children's Oncology Group. J. Clin. Oncol. 2012;30(21):2641–2647. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.36.6054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Packer R, Ater J, Allen J, et al. Carboplatin and vincristine chemotherapy for children with newly diagnosed progressive low-grade gliomas. J. Neurosurg. 1997;86(5):747–754. doi: 10.3171/jns.1997.86.5.0747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sposto R, et al. The effectiveness of chemotherapy for treatment of high grade astrocytoma in children: results of a randomized trial. A report from the Children's Cancer Study Group. J. Neurooncol. 1989;7(2):165–177. doi: 10.1007/BF00165101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pendergrass T, Milstein J, Geyer J, et al. Eight drugs in one day chemotherapy for brain tumors: experience in 107 children and rationale for pre-radiation chemotherapy. J. Clin. Oncol. 1987;5:1221–1231. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1987.5.8.1221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Finlay J, Boyett J, Yates A, et al. Randomized Phase III trial in childhood high-grade astrocytoma comparing vincristine, lomustine, and prednisone with the eight drugs-in-1-day regimen. Childrens Cancer Group. J. Clin. Oncol. 1995;13:112–123. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1995.13.1.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Finlay J, Zacharoulis S. The treatment of high grade gliomas and diffuse intrinsic pontine tumors of childhood and adolescence: a historical – and futuristic – perspective. J. Neurooncol. 2005;75:253–266. doi: 10.1007/s11060-005-6747-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fangusaro J, Warren K. Unclear standard of care for pediatric high grade glioma patients. J. Neurooncol. 2013;113(2):341–342. doi: 10.1007/s11060-013-1104-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Warren K. Diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma: poised for progress. Front. Oncol. 2012;2:205. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2012.00205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Veringa S, Biesmans D, Van Vuurden D, et al. In vitro drug response and efflux transporters associated with drug resistance in pediatric high grade glioma and diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma. PLoS One. 2013;8(4):e61512. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Siegal T. Which drug or drug delivery system can change clinical practice for brain tumor therapy? Neuro. Oncol. 2013;15(6):656–669. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/not016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abbott N. Blood–brain barrier structure and function and the challenges for CNS drug delivery. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2013;36:437–449. doi: 10.1007/s10545-013-9608-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sethi R, Allen J, Donahue B, et al. Prospective neuraxis MRI surveillance reveals a high risk of leptomeningeal dissemination in diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma. J. Neurooncol. 2011;102(1):121–127. doi: 10.1007/s11060-010-0301-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eckman W, Patlak C, Fenstermacher J. A critical evaluation of the principles governing the advantages of intra-arterial infusions. J. Pharmacokinet. Biopharm. 1974;2:257–285. doi: 10.1007/BF01059765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liapi E, Geschwind J. Intra-arterial therapies for hepatocellular carcinoma: where do we stand? Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2010;17:1234–1246. doi: 10.1245/s10434-010-0977-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shields C, Shields J. Retinoblastoma management: advances in enucleation, intravenous chemoreduction, and intra-arterial chemotherapy. Curr. Opin. Ophthalmol. 2010;21:203–212. doi: 10.1097/ICU.0b013e328338676a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Neuwelt E, Frenkel E, D'Agostino A, et al. Growth of human lung tumor in the brain of nude rat as a model to evaluate antitumor agent delivery across the blood brain barrier. Cancer Res. 1985;45:2827–2833. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Iwadate Y, Namba H, Saegusa T, et al. Intra-arterial mannitol infusion in the chemotherapy for malignant brain tumors. J. Neurooncol. 1993;15:185–193. doi: 10.1007/BF01053940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hori T, Muraoka K, Saito Y, et al. Influence of modes of ACNU administration on tissue and blood drug concentration in malignant brain tumors. J. Neurosurg. 1987;66:372–378. doi: 10.3171/jns.1987.66.3.0372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Basso U, Lonardi S, Brandes A. Is intra-arterial chemotherapy useful in high-grade gliomas? Expert Rev. Anticancer Ther. 2002;2(5):507–519. doi: 10.1586/14737140.2.5.507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shapiro W, Green S, Burger P, et al. A randomized comparison of intra-arterial versus intravenous BCNU, with or without intravenous 5-fluorouracil, for newly diagnosed patients with malignant glioma. J. Neurosurg. 1992;76:772–781. doi: 10.3171/jns.1992.76.5.0772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Feun L, Lee Y, Yung W, et al. Phase II trial of intracarotid BCNU and cisplatin in primary malignant brain tumors. Cancer Drug Deliv. 1986;3:147–156. doi: 10.1089/cdd.1986.3.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Imbesi F, Marchioni E, Benericetti E, et al. A randomized Phase III study: comparison between intravenous and intraarterial ACNU administration in newly diagnosed primary glioblastomas. Anticancer Res. 2006;26:553–558. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cloughesy T, Gobin Y, Black K, et al. Intra-arterial carboplatin chemotherapy for brain tumors: a dose escalation study based on cerebral blood flow. J. Neurooncol. 1997;35:121–131. doi: 10.1023/a:1005856002264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Clocchlatti L, Cartei G, Lavaroni A, et al. Intra-arterial chemotherapy with carboplatin (CBDCA) and vepesid (VP16) in primary malignant brain tumours. Preliminary findings. Interv. Neuroradiol. 1996;2:277–281. doi: 10.1177/159101999600200405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hiesiger E, Green S, Shapiro W, et al. Results of a randomized trial comparing intra-arterial cisplatin and intravenous PCNU for the treatment of primary brain tumors in adults: Brain Tumor Cooperative Group Trial 8420A. J. Neurooncol. 1995;25(2):43–54. doi: 10.1007/BF01057758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lutz R, Warren K, Balis F, Patronas N, Dedrick R. Mixing during intravertebral arterial infusions in an in vitro model. J. Neurooncol. 2002;58(2):95–106. doi: 10.1023/a:1016034910875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Riina H, Knopman J, Greenfield J, et al. Balloon-assisted superselectve intra-arterial cerebral infusion of bevacizumab for malignant brainstem glioma. A technical note. Interv. Neuroradiol. 2010;16:71–76. doi: 10.1177/159101991001600109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yohay K, Wolf D, Aronson L, Duus M, Melhem E, Cohen K. Vascular distribution of glioblastoma multiforme at diagnosis. Interv. Neurorad. 2013;19(1):127–131. doi: 10.1177/159101991301900119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Neuwelt E, Howieson J, Frenkel E, et al. Therapeutic efficacy of multiagent chemotherapy with drug delivery enhancement by blood–brain barrier modification in glioblastoma. Neurosurgery. 1986;19:573–582. doi: 10.1227/00006123-198610000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dahlborg S, Petrillo A, Crossen J, et al. The potential for complete and durable response in nonglial primary brain tumors in children and young adults with enhanced chemotherapy delivery. Cancer J. Sci. Am. 1998;4(2):110–124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fujiwara T, Ogawa T, Irie K, Tsuchida T, Nagao S, Ohkawa M. Intra-arterial chemotherapy for brain stem glioma: report of four cases. Neuroradiology. 1994;36:74–79. doi: 10.1007/BF00599203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nagpal S. The role of BCNU polymer wafers (Gliadel) in the treatment of malignant glioma. Neurosurg. Clin. N. Am. 2012;23:289–295. doi: 10.1016/j.nec.2012.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tamargo R, Myseros J, Epstein J, et al. Interstitial chemotherapy of the 9L gliosarcoma: controlled release polymers for drug delivery in the brain. Cancer Res. 1993;53:329–333. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brem H, Langer R. Polymer-based drug delivery to the brain. Sci. Am. Sci. Med. 1996;3:52–61. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brem H, Mahaley M, Vick N, et al. Interstitial chemotherapy with drug polymer implants for the treatment of recurrent gliomas. J. Neurosurg. 1991;74:441–446. doi: 10.3171/jns.1991.74.3.0441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brem H, Piantadosi S, Burger P, et al. Placebo-controlled trial of safety and efficacy of intraoperative controlled delivery by biodegradable polymers of chemotherapy for recurrent gliomas. The Polymer-brain Tumor Treatment Group. Lancet. 1995;345(8956):1008–1012. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)90755-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Olivi A, Grossman S, Tatter S, et al. Dose escalation of carmustine in surgically implanted polymers in patients with recurrent malignant glioma: a new approaches to Brain Tumor Therapy CNS Consortium Trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2003;21(9):1845–1849. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.09.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Valtonen S, Timonen U, Toivanen P, et al. Interstitial chemotherapy with carmustine-loaded polymers for high-grade gliomas: a randomized double-blind study. Neurosurgery. 1997;41:44–49. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199707000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kleinberg L, Weingart J, Burger P, et al. Clinical course and pathologic findings after Gliadel and radiotherapy for newly diagnosed malignant glioma: implications for patient management. Cancer Invest. 2004;22(1):1–9. doi: 10.1081/cnv-120027575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Duntze J, Litre C, Eap C, et al. Implanted carmustine wafers followed by concomitant radiochemotherapy to treat newly diagnosed malignant gliomas: prospective, observational, multicenter study on 92 cases. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2013;20(6):2065–2072. doi: 10.1245/s10434-012-2764-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Miglierini P, Bouchekoua M, Rousseau B, Hieu P, Malhaire J, Pradier O. Impact of the per-operatory application of Gliadel wafers (BCNU, carmustine) in combination with temozolomide and radiotherapy in patients with glioblastoma multiforme: efficacy and toxicity. Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 2012;114(9):1222–1225. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2012.02.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sawyer A, Piepmeier J, Saltzman W. New methods for direct delivery of chemotherapy for treating brain tumors. Yale J. Biol. Med. 2006;79(3–4):141–152. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Grossman S, Reinhard C, Colvin O, et al. The intracerebral distribution of BCNU delivered by surgically implanted biodegradable polymers. J. Neurosurg. 1992;76(4):640–647. doi: 10.3171/jns.1992.76.4.0640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fung L, Ewend M, Sills A, et al. Pharmacokinetics of interstitial delivery of carmustine, 4-hydroperoxycyclophosphamide, and paclitaxel from a biodegradable polymer implant in the monkey brain. Cancer Res. 1998;58(4):672–684. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bobo R, Laske D, Akbasak A, Morrison P, Dedrick R, Oldfield E. Convection-enanced delivery of macromolecules in the brain. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1994;91:2076–2080. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.6.2076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chen M, Lonser R, Morrison P, Governale L, Oldfield E. Variables affecting convection-enhanced delivery to the striatum: a systematic examination of rate of infusion, cannula size, infusate concentration, and tissue-cannula sealing time. J. Neurosurg. 1999;90:315–320. doi: 10.3171/jns.1999.90.2.0315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Laske D, Youle R, Oldfield E. Tumor regression with regional distribution of the targeted toxin TF-CRM107 in patients with malignant brain tumors. Nat. Med. 1997;3(12):1362–1368. doi: 10.1038/nm1297-1362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bruce J, Fine R, Canoll P, et al. Regression of recurrent malignant gliomas with convection-enhanced delivery of topotecan. Neurosurgery. 2011;69:1272–1279. doi: 10.1227/NEU.0b013e3182233e24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lonser R, Warren K, Butman J, et al. Real-time image-guided direct convective perfusion of intrinsic brainstem lesions. Technical note. J. Neurosurg. 2007;107(1):190–197. doi: 10.3171/JNS-07/07/0190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kunwar S. Convection-enhanced delivery of IL13-PE38QQR for treatment of recurrent malignant glioma: presentation of interim findings from ongoing Phase 1 studies. Acta Neurochir. Suppl. 2003;88:105–111. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-6090-9_16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lidar Z, Mardor Y, Jonas T, Al E. Convection-enhanced delivery of paclitaxel for the treatment of recurrent malignant glioma: a Phase I/II clinical study. J. Neurosurg. 2004;100:472–479. doi: 10.3171/jns.2004.100.3.0472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sampson J, Akabani G, Archer G, et al. Progress report of a Phase I study of the intracerebral microinfusion of a recombinant chimeric protein composed of transforming growth factor (TGF)-α and a mutated form of the Pseudomonas exotoxin termed PE-38 (TP-38) for the treatment of malignant brain tumors. J. Neurooncol. 2003;65:27–35. doi: 10.1023/a:1026290315809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kunwar S, Chang S, Westphal M, et al. Phase III randomised trial of CED of IL13-PE38QQR vs Gliadel wafers for recurrent glioblastoma. Neuro. Oncol. 2010;12(8):871–881. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nop054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Voges J, Reszka R, Grossman A, et al. Imaging-guided convection-enhanced delivery and gene therapy of glioblastoma. Ann. Neurol. 2003;54(4):479–487. doi: 10.1002/ana.10688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Asthagiri A, Walbridge S, Heiss J, Lonser R. Effect of concentration on the accuracy of convective imaging distribution of gadolinium-based surrogate tracer. J. Neurosurg. 2011;115(3):467–473. doi: 10.3171/2011.3.JNS101381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Illum L. Transport of drugs from the nasal cavity to the central nervous system. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2000;11:1–18. doi: 10.1016/s0928-0987(00)00087-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wu H, Hu K, Jiang X. From nose to brain: understanding transport capacity and transport rate of drugs. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 2008;5(10):1159–1168. doi: 10.1517/17425247.5.10.1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pardeshi C, Belgamwar V. Direct nose to brain drug delivery via integrated nerve pathways bypassing the blood–brain barrier: an excellent platform for brain targeting. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 2013;10(7):957–972. doi: 10.1517/17425247.2013.790887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Thorne R, Hanson L, Ross T, et al. Delivery of interferon-beta to the monkey nervous system following internasal administration. Neuroscience. 2008;152:785–797. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dhuria S, Hanson L, Frey W. Intranasal delivery to the central nervous system: mechanisms and experimental considerations. J. Pharmaceut. Sci. 2010;99(4):1654–1673. doi: 10.1002/jps.21924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Thorne R, Pronk G, Padmanabhan V, Frey WN. Delivery of insulin-like growth factor-I to the rat brain and spinal cord along olfactory and trigeminal pathways following intranasal administration. Neuroscience. 2004;127:481–496. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Thorne R, Emory C, Ala A, Frey W. Quantitative analysis of the olfactory pathway for drug delivery to the brain. Brain Res. 1995;692(1–2):278–282. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)00637-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Shingaki T, Inoue D, Furubayashi T, et al. Transnasal delivery of methotrexate to brain tumors in rats: a new strategy for brain tumor chemotherapy. Mol. Pharm. 2010;7(5):1561–1568. doi: 10.1021/mp900275s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wang F, Jiang X, Lu W. Profiles of methotrexate in blood and CSF following intranasal and intravenous administration in rats. Int. J. Pharm. 2003;263:1–7. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5173(03)00341-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sakane T, Yamashita S, Yata N, Sezaki H. Transnasal delivery of 5-fluorouracil to the brain in the rat. J. Drug Target. 1999;7:233–240. doi: 10.3109/10611869909085506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hashizume R, Ozawa T, Gryaznov S, et al. New therapeutic approach for brain tumors: intranasal delivery of telomerase inhibitor GRN163. Neuro. Oncol. 2008;10(2):112–120. doi: 10.1215/15228517-2007-052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Da Fonseca C, Silva J, Lins I, et al. Correlation of tumor topography and peritumoral edema of recurrent malignant gliomas with therapeutic response to intranasal administration of perillyl alcohol. Invest. New Drugs. 2009;27:557–564. doi: 10.1007/s10637-008-9215-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]