Abstract

Objectives

Our objective was to estimate the percentage of patients with incident rheumatoid arthritis (RA) who were seen by a rheumatologist within 3, 6 and 12 months of suspected diagnosis by a family physician, and assess what factors may influence the time frame with which patients are seen.

Setting

Ontario, Canada.

Participants

Over 2000–2009, we studied patients with incident RA who were initially diagnosed by a family physician.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

We assessed secular trends in rheumatology encounters and differences between patients who received versus did not receive rheumatology care. We performed hierarchical logistic regression analyses to determine whether receipt of rheumatology care was associated with patient, primary care physician and geographical factors.

Results

Among 19 760 patients with incident RA, 59%, 75% and 84% of patients were seen by a rheumatologist within 3, 6 and 12 months, respectively. The prevalence of initial consultations within 3 months did not increase over time; however, access within 6 and 12 months increased over time. Factors positively associated with timely consultations included higher regional rheumatology supply (adjusted OR (aOR) 1.35 (95% CI 1.13 to 1.60)) and higher patient socioeconomic status (aOR 1.18 (95% CI 1.07 to 1.30)). Conversely, factors inversely associated with timely consultations included remote patient residence (aOR 0.51 (95% CI 0.41 to 0.64)) and male family physicians (aOR 0.88 (95% CI 0.81 to 0.95)).

Conclusions

Increasing access to rheumatologists within 6 and 12 months occurred over time; however, consultations within 3 months did not change over time. Measures of poor access (such as proximity to and density of rheumatologists) were negatively associated with timely consultations. Additional factors that contributed to disparities in access included patient socioeconomic status and physician sex.

Keywords: Rheumatology

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Strengths of our study include its large sample and the use of a validated population-based rheumatoid arthritis (RA) cohort.

Our main limitation is that our cohort definition requires patients whose family physician strongly suspects that the patient has RA; thus, our analyses are likely restricted to patients with a more homogeneous clinical presentation (such as rheumatoid factor positive patients) or those with more active disease.

Owing to the absence of symptom onset and date of referral in health administrative databases, we have only studied a proportion of the total delay to rheumatology consultations.

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a progressive inflammatory arthritis associated with joint damage and functional deterioration, work disability and premature mortality.1 At disease onset, RA is considered as an urgent medical condition1 2 requiring prompt referral to a rheumatologist.3–5 Timely rheumatology care is important as it increases early exposure to treatment,6 improves patient outcomes,7 8 decreases the need for costly surgical interventions9 and thus reduces the global disease burden. Furthermore, the sooner a patient is seen and managed by rheumatologists results in superior clinical responses and increases the chance of disease remission10–14 than if the same care is administered later in the disease course.15

In Canada, access to specialists often depends on referral by a family physician. For optimal RA care to occur, a patient must seek care by a family physician, who, in turn, must suspect RA and initiate referral to a rheumatologist, who will undertake the appropriate diagnostic tests and initiate early treatment.16 Delays that occur at any of these stages prevent patients from receiving timely care.

Ontario has approximately 13 million residents and 10 000 family physicians.17 There are approximately 150 rheumatologists (1.5 rheumatologists per 100 000 population); however, they are concentrated most heavily in southern Ontario,18 which may be a potential barrier to equitable, timely rheumatology care.19 Accordingly, we set out to determine the percentage of patients with incident RA who consulted a rheumatologist within 3, 6 and 12 months of suspected diagnosis by a family physician, and assessed what factors may influence the time frame within which patients are seen.

Subjects and methods

Setting and design

We performed a retrospective, population-based cohort study of newly diagnosed patients with RA within Ontario, in which all residents are covered by universal public health insurance for physician and hospital services.

Data sources

We used the Ontario Rheumatoid Arthritis Administrative Database (ORAD), a population-based RA cohort generated from health administrative databases using a validated case definition. Patients with RA are included in ORAD if they have three Ontario Health Insurance (OHIP) physician service claims over a 2-year period in which RA is the recorded diagnosis, with at least one of these claims made by a musculoskeletal specialist. ORAD has been validated and shown to have a high sensitivity (78%), specificity (100%) and positive predictive value (78%) for identifying patients with RA based on medical record reviews.20 21 Validation of RA onset within administrative data has also shown to be highly accurate.21 Records for individuals in ORAD are also linked to the following administrative datasets. The Ontario Registered Persons Database was used to identify demographic information on age, sex, place of residence, death and emigration. Physician specialty was obtained by linking the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences (ICES) Physician Database with the OHIP database.22 We used the Client Agency Program Enrolment Database to identify the primary care delivery model of the family physician at the time the patient entered the cohort. These datasets are linked in an anonymous fashion using encrypted health insurance numbers for residents and encrypted license numbers for physicians, and they have very little missing information.23

Cohort definition

We identified all incident patients with RA from 1 April 2000 to 31 March 2010. Analyses were restricted to patients whose initial RA diagnosis codes were assigned by a family physician in an outpatient setting. Cohort entry (suspected RA diagnosis date) was the date of the first RA diagnosis code, and patients were followed up until 1 year or until outmigration, death or the end of study period.

Covariate information

Covariates for patient demographics included age, sex, socioeconomic status (SES) and year of suspected diagnosis. SES was defined as the patient's neighbourhood median household income quintile from the Statistics Canada Census. We also identified whether patients were subsequently admitted to hospital with an RA diagnosis following a primary care diagnosis, as patients who are seen in a hospital setting for their RA may have poorer access to healthcare providers and/or more severe disease. As a measure of comorbidity, we used the Johns Hopkins Adjusted Diagnostic Groups (ADG) Case-Mix System derived from outpatient and inpatient data in 2 years preceding cohort entry.24 We categorised ADGs into low (<5), moderate (5–9) and high comorbidity (10+). We chose this risk adjustment method as patients using the most healthcare resources are not typically those with single diseases but rather those with multiple and sometimes unrelated conditions. This clustering of morbidity can be a better predictor of healthcare use than the presence of specific diseases.25 Geographical characteristics included patient residence, regional health service planning areas (Local Health Integration Networks, LHINs26), rheumatology supply and distance to the closest rheumatologist. Rurality was based on each patient's postal code and a community population size of less than 10 000. Rheumatology supply was defined as the number of rheumatologists per 100 000 adults in the planning area (LHIN) of patient residence, and distance to the closest rheumatologist was the linear distance from the centre of patient's postal code area to that of the closest rheumatologist, with ‘remote residence’ defined as 100 or more kilometres to the nearest rheumatologist. Family physician characteristics included sex, years since graduation (as a proxy for experience) and type of primary care delivery model the family physician was working in at the time of patient's cohort entry. We categorised each practice type as (1) blended capitation models (Family Health Networks (FHNs), Family Health Organisations (FHOs), Family Health Teams (FHTs)) and (2) either traditional or enhanced fee-for-service models (Family Health Groups or FHGs).27 The main difference between the models is how physicians are reimbursed (eg, through age-adjusted and sex-adjusted capitation payments versus being paid on a per visit basis). Capitation models often include interdisciplinary teams involving allied healthcare providers and require physicians to maintain a list or ‘roster’ of enrolled patients to whom they are committed to providing primary care.28 Including primary care model type enabled us to explore if there was an effect regarding different primary care practice models and/or how the physicians are paid as a facilitator to timely rheumatology care.

Outcome measurements

We followed incident patients, determining whether they had a visit to a rheumatologist at 3, 6 and 12 months of cohort entry.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to characterise the study population. We assessed secular trends (as the percentage of each annual incident RA cohort who consulted a rheumatologist within each time period) and differences among patients who received versus did not receive rheumatology care. We performed hierarchical logistic regression analyses to determine whether receipt of rheumatology care was associated with patient demographics, comorbidity, geographical characteristics and family physician characteristics. Crude and adjusted OR (aOR) estimates with 95% CIs were generated. Separate analyses were performed for each outcome end date (benchmarks): 3, 6 and 12 months.

All analyses were performed at the ICES on anonymised data using SAS V.9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, USA).

Results

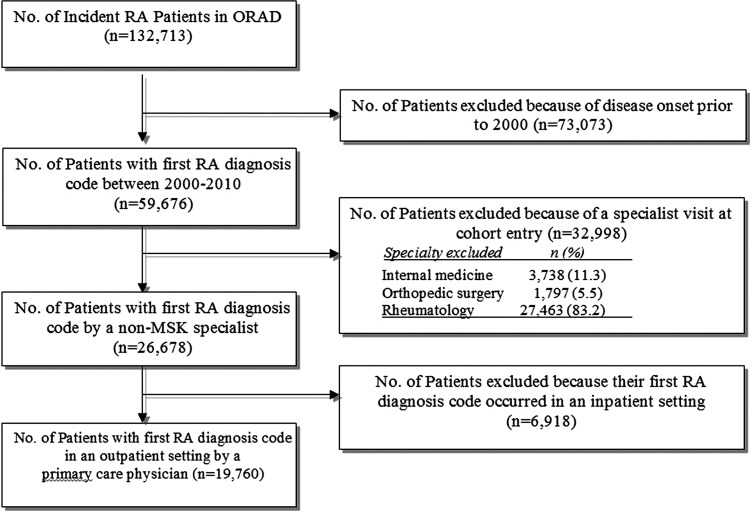

Between 2000 and 2009, we identified 19 670 patients with incident RA (figure 1). Overall, the mean (SD) age at the time of cohort entry was 54 (16) years, 71% were women, 16% resided in rural areas and 5% resided in areas remote (≥100 km) from the nearest rheumatologist (table 1). Most patients were seen by male family physicians (70%). Few (5%) physicians were practising under a newer capitation model.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of selection of study participants.

Table 1.

Selected cohort characteristics of 19 670 newly diagnosed patients with RA that met our criteria

| Characteristic | Newly diagnosed RA n=19 670 |

|---|---|

| Patient demographics | |

| Age at cohort entry, mean (SD) | 53.7 (16.3) |

| Female, n (%) | 14 091 (71.1) |

| Rural residence, n (%) | 3196 (16.2) |

| Patient comorbidity | |

| Number of Hopkins ADGs* in the 2 years prior to entry, n (%) | |

| <5 | 5229 (26.5) |

| 5–9 | 9790 (49.5) |

| 10+ | 4741 (24.0) |

| Rheumatology access measures | |

| Time (days) from first diagnosis code to first rheumatologist visit, mean (SD) | 76.7 (76.9) |

| Time (days) from first diagnosis code to first rheumatologist visit, median (IQR) | 50 (22–104) |

| Rheumatology supply per 100 000 adults†, mean (SD) | 1.5 (1.1) |

| Distance to closest rheumatologist | |

| Kilometres, mean (SD) | 24.2 (69.7) |

| Remote (≥100 km), n (%) | 1047 (5.3) |

| Primary care physician's characteristics | |

| Male, n (%) | 13 872 (70.2) |

| Years since graduation, mean (SD) | 24.5 (10.5) |

| Practice type, n (%) | |

| Blended capitation models‡ (FHO/FHN) | 976 (4.9) |

| Traditional fee-for-service and enhanced fee-for-service (FHG/other) | 18 784 (95.1) |

*Ambulatory diagnostic groups.

†In patient LHINs (regional health service planning areas).

‡Practice types: blended capitation models (FHNs, FHOs, FHTs, an interprofessional team model composed of FHNs and FHOs), enhanced fee-for-service models (FHGs and other groups).

ADG, Adjusted Diagnostic Groups; FGH, Family Health Group; FHN, Family Health Network; FHO, Family Health Organisation; FHT, Family Health Team; LHIN, Local Health Integration Network; RA, rheumatoid arthritis.

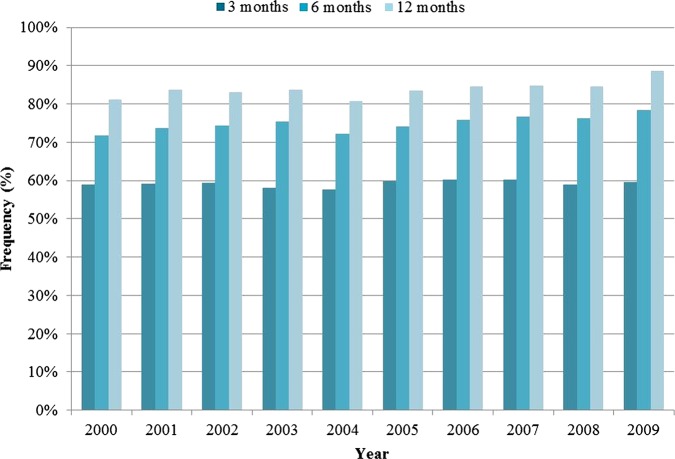

Over 1 year of follow-up, the average time from the first RA diagnosis code to first rheumatologist visit was 77 days (table 1). Overall, 59%, 75% and 84% of patients consulted a rheumatologist within 3, 6 and 12 months, respectively. The prevalence of initial rheumatology encounters within 3 months did not increase over the study period. However, the percentage of patients who consulted a rheumatologist within 6 and 12 months increased gradually over time, from 72% and 81% in 2000 to 81% and 89% in 2009, respectively (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Percentage of patients with newly diagnosed rheumatoid arthritis who are seen by a rheumatologist within 3, 6 and 12 months of suspected diagnosis by a primary care physician.

Table 2 compares the characteristics of patients who consulted versus did not consult a rheumatologist within 3 months of cohort entry. More patients who were not seen by a rheumatologist lived in a rural area (19% vs 14%) and remote areas.

Table 2.

Descriptive characteristics for patients with RA that do and do not receive rheumatology care and influence of various factors on receipt of rheumatology care within 3 months of suspected diagnosis by a primary care physician

| Characteristic | Seen by a rheumatologist |

Multivariate analysis |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Crude OR | Adjusted*OR | |

| n=11 694 | N=8066 | (95% CI) | (95% CI) | |

| Demographics | ||||

| Age, mean (SD) | 53.8 (15.9) | 53.6 (16.7) | 1.00 (1.00 to 1.00) | 1.00 (1.00 to 1.00) |

| Male sex, n (%) (REF=female) | 3341 (28.6) | 2328 (28.9) | 1.01 (0.95 to 1.07) | 1.04 (0.97 to 1.11) |

| Income quintile, n(%) (REF=1—low) | 59 (0.5) | 50 (0.6) | REF | REF |

| 2 | 2197 (18.8) | 1693 (21) | 1.10 (1.00 to 1.20) | 1.08 (0.98 to 1.18) |

| 3 | 2359 (20.2) | 1657 (20.5) | 1.12 (1.03 to 1.23) | 1.11 (1.01 to 1.22) |

| 4 | 2407 (20.6) | 1627 (20.2) | 1.12 (1.02 to 1.23) | 1.09 (0.99 to 1.20) |

| 5 | 2305 (19.7) | 1581 (19.6) | 1.22 (1.11 to 1.34) | 1.18 (1.07 to 1.30) |

| Calendar-year of cohort entry (REF=2000) | ||||

| 2000 | 1110 | 774 | REF | REF |

| 2001 | 1110 | 768 | 0.99 (0.87 to 1.13) | 0.99 (0.87 to 1.14) |

| 2002 | 1074 | 736 | 1.00 (0.87 to 1.14) | 1.00 (0.87 to 1.15) |

| 2003 | 1154 | 830 | 0.96 (0.85 to 1.10) | 0.99 (0.87 to 1.13) |

| 2004 | 1187 | 872 | 0.94 (0.83 to 1.08) | 0.99 (0.87 to 1.14) |

| 2005 | 1231 | 828 | 1.05 (0.92 to 1.20) | 1.12 (0.98 to 1.28) |

| 2006 | 1179 | 782 | 1.07 (0.94 to 1.22) | 1.13 (0.98 to 1.29) |

| 2007 | 1237 | 818 | 1.07 (0.94 to 1.23) | 1.14 (0.99 to 1.31) |

| 2008 | 1268 | 885 | 1.01 (0.89 to 1.16) | 1.10 (0.96 to 1.26) |

| 2009 | 1144 | 773 | 1.03 (0.90 to 1.18) | 1.10 (0.95 to 1.27) |

| Comorbidity: number of Hopkins ADGs in the 2 years prior to entry, n (%) (REF=<5) | ||||

| <5 | 3031 (25.9) | 2198 (27.3) | REF | REF |

| 5–9 | 5802 (49.6) | 3988 (49.4) | 1.04 (0.97 to 1.12) | 1.04 [0.97 to 1.12] |

| 10+ | 2861 (24.5) | 1880 (23.3) | 1.08 (0.99 to 1.18) | 1.07 [0.98 to 1.17] |

| Hospitalisation for RA prior to rheumatologist visit/end of study period, n(%) | 71 (0.6) | 41 (0.5) | 1.24 (0.84 to 1.84) | 1.34 [0.89 to 2.02] |

| Geographic | ||||

| Patient rural residence, n(%); (REF=urban) | 1636 (14.0) | 1560 (19.3) | 0.70 (0.64 to 0.76) | 0.92 (0.83 to 1.01) |

| Rheumatology supply per 100 000 adults, mean (SD) | 1.6 (1.1) | 1.4 (1.0) | 1.16 (1.12 to 1.19) | 1.35 (1.13 to 1.60) |

| Distance to rheumatologist (km), mean (SD) | 17.8 (64.24) | 33.6 (75.89) | n/a | n/a |

| Remote distance (≥100 km to rheumatologist), n(%) | 312 (2.7) | 735 (9.1) | 0.29 (0.25 to 0.34) | 0.51 (0.41 to 0.64) |

| Primary care physician | ||||

| Male sex, n (%) (REF=female) | 8069 (69.0) | 5803 (71.9) | 0.83 (0.77 to 0.89) | 0.87 (0.81 to 0.95) |

| Years since graduation, mean (SD) | 24.3 (10.48) | 24.6 (10.53) | 1.00 (0.99 to 1.00) | 1.00 (0.99 to 1.00) |

| Practice type†, n (%) (REF=fee-for-service) | ||||

| Traditional and enhanced fee-for-service | 11 085 (94.8) | 7699 (95.5) | REF | REF |

| Blended capitation models | 609 (5.2) | 367 (4.5) | 1.14 (0.98 to 1.32) | 1.15 (0.99 to 1.34) |

*Adjusted for all covariates including: patient demographics, clinical factors, primary care physician characteristics, provider continuity and geographic characteristics (including regional variation by regional health service planning areas LHINs not reported here).

†Practice types: blended capitation models (FHNs, FHOs, FHTs, an interprofessional team model composed of FHNs and FHOs), enhanced fee-for-service models (FHGs and other groups) and solo fee-for-service practitioners (those who did not belong to a model).

ADG, Adjusted Diagnostic Groups; FGH, Family Health Group; FHN, Family Health Network; FHO, Family Health Organisation; FHT, Family Health Team; LHIN, Local Health Integration Network; RA, rheumatoid arthritis.

Independent determinants of receiving rheumatology care within 3 months of RA diagnosis are reported in table 2. Factors associated with prompt rheumatology care included increasing rheumatology supply (aOR 1.35 (95% CI 1.13 to 1.60)) and higher patient SES (aOR 1.18 (95% CI 1.07 to 1.30)). The strongest independent factor negatively associated with lower frequency of rheumatology visits was for patients who lived at remote distances to rheumatologists (aOR 0.51 (95% CI 0.41 to 0.64)). The likelihood of not having prompt rheumatology consultations was also reduced for patients of male family physicians (aOR 0.87 (95% CI 0.81 to 0.95)). There was no calendar-year effect illustrating an increasing likelihood of seeing a rheumatologist within 3 months over time. However, improvements over time were demonstrated for patients being seen by a rheumatologist within 6 and 12 months (table 3).

Table 3.

Influence of patient demographics, comorbidity, geographic characteristics and primary care physician characteristics on receipt of rheumatology care within 6 and 12 months

| Characteristic | 6 months |

12 months |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude OR (95% CI) | Adjusted‡ OR (95% CI) | Crude OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR [95% CI] | |

| Demographics | ||||

| Age, mean (± SD) | 1.00 (1.00 to 1.00) | 1.00 (1.00 to 1.00) | 1.00 (1.00 to 1.00) | 1.00 (1.00 to 1.00) |

| Male sex (REF=female) | 0.97 (0.90 to 1.04) | 0.98 (0.91 to 1.06) | 0.92 (0.85 to 1.00) | 0.94 (0.86 to 1.02) |

| Income quintile (REF=1—low) | REF | REF | REF | REF |

| 2 | 1.15 (1.04 to 1.27) | 1.14 (1.03 to 1.26) | 1.07 (0.96 to 1.21) | 1.06 (0.94 to 1.20) |

| 3 | 1.22 (1.10 to 1.35) | 1.20 (1.08 to 1.33) | 1.17 (1.04 to 1.32) | 1.16 (1.03 to 1.31) |

| 4 | 1.15 (1.04 to 1.27) | 1.11 (1.00 to 1.24) | 1.15 (1.02 to 1.30) | 1.12 (0.99 to 1.27) |

| 5 | 1.30 (1.17 to 1.44) | 1.26 (1.13 to 1.40) | 1.35 (1.19 to 1.53) | 1.31 (1.15 to 1.49) |

| Calendar-year of cohort entry (REF=2000) | REF | REF | REF | REF |

| 2001 | 1.07 (0.92 to 1.23) | 1.07 (0.92 to 1.24) | 1.13 (0.96 to 1.34) | 1.13 (0.95 to 1.35) |

| 2002 | 1.12 (0.97 to 1.30) | 1.12 (0.96 to 1.31) | 1.12 (0.95 to 1.33) | 1.14 (0.95 to 1.36) |

| 2003 | 1.19 (1.02 to 1.38) | 1.22 (1.04 to 1.42) | 1.18 (0.99 to 1.40) | 1.21 (1.01 to 1.44) |

| 2004 | 1.01 (0.87 to 1.17) | 1.04 (0.89 to 1.21) | 0.97 (0.82 to 1.15) | 1.01 (0.84 to 1.20) |

| 2005 | 1.15 (1.00 to 1.34) | 1.21 (1.04 to 1.41) | 1.22 (1.02 to 1.45) | 1.30 (1.08 to 1.56) |

| 2006 | 1.25 (1.07 to 1.45) | 1.30 (1.11 to 1.52) | 1.28 (1.07 to 1.53) | 1.33 (1.10 to 1.60) |

| 2007 | 1.29 (1.11 to 1.50) | 1.37 (1.17 to 1.60) | 1.33 (1.11 to 1.59) | 1.42 (1.18 to 1.72) |

| 2008 | 1.26 (1.09 to 1.47) | 1.35 (1.16 to 1.58) | 1.30 (1.09 to 1.55) | 1.41 (1.17 to 1.70) |

| 2009 | 1.42 (1.21 to 1.66) | 1.49 (1.26 to 1.76) | 1.83 (1.51 to 2.22) | 1.96 (1.60 to 2.40) |

| Comorbidity | ||||

| Number of Hopkins ADGs (REF≤5) | REF | REF | REF | REF |

| 5–9 | 1.02 (0.94 to 1.10) | 1.03 (0.95 to 1.12) | 1.03 (0.94 to 1.13) | 1.07 (0.97 to 1.18) |

| 10+ | 1.02 (0.93 to 1.12) | 1.05 (0.95 to 1.16) | 1.04 (0.93 to 1.16) | 1.09 (0.97 to 1.23) |

| Hospitalisation for RA prior to rheumatologist visit/end of study period | 0.60 (0.42 to 0.85) | 0.63 (0.44 to 0.91) | 0.51 (0.36 to 0.71) | 0.54 (0.38 to 0.76) |

| Geographic | ||||

| Patient rural residence (REF=urban) | 0.74 (0.68 to 0.81) | 1.00 (0.89 to 1.11) | 0.80 (0.72 to 0.89) | 1.09 (0.96 to 1.24) |

| Rheumatology supply per 100 000 adults | 1.15 (1.11 to 1.20) | 1.19 (0.97 to 1.45) | 1.16 (1.11 to 1.22) | 1.25 (0.98 to 1.61) |

| Remote distance (≥100 km to rheumatologist) | 0.28 (0.24 to 0.33) | 0.46 (0.36 to 0.59) | 0.26 (0.22 to 0.31) | 0.33 (0.26 to 0.43) |

| Primary care physician | ||||

| Male sex (REF=female) | 0.81 (0.74 to 0.89) | 0.89 (0.81 to 0.97) | 0.81 (0.73 to 0.90) | 0.91 (0.81 to 1.01) |

| Years since graduation | 1.00 (0.99 to 1.00) | 0.99 (0.99 to 1.00) | 1.00 (0.99 to 1.00) | 0.99 (0.99 to 1.00) |

| Practice type†(REF=fee-for-service) | ||||

| Capitation model | 1.22 (1.01 to 1.47) | 1.13 (0.93 to 1.36) | 1.22 (0.99 to 1.51) | 1.09 (0.87 to 1.35) |

*Adjusted for all covariates including: patient demographics, clinical factors, primary care physician characteristics, provider continuity and geographical characteristics (including regional variation by regional health service planning areas LHINs not reported here).

†Practice types: blended capitation models (FHNs, FHOs, FHTs, an interprofessional team model composed of FHNs and FHOs), enhanced fee-for-service models (FHGs and other groups) and traditional fee-for-service.

ADG, Adjusted Diagnostic Groups; FGH, Family Health Group; FHN, Family Health Network; FHO, Family Health Organisation; FHT, Family Health Team; LHIN, Local Health Integration Network.

We observed similar associations when we studied the effects of factors on the odds of receiving rheumatology care within 6 and 12 months (table 3). The effect of proximity on access became stronger as the time to rheumatology visit was lengthened: 6 months (aOR 0.56 (95% CI 0.36 to 0.59) and 12 months (aOR 0.33 (95% CI 0.26 to 0.43). Patients who were hospitalised for RA subsequent to an initial diagnosis in an outpatient primary care setting were almost half as likely to been seen by a rheumatologist at 6 and 12 months.

Discussion

In a publicly funded universal healthcare system, we studied trends in encounters with rheumatologists over the past decade and observed increasing rates of access to rheumatologists within 6 and 12 months after diagnosis by a family physician. However, no such improvements were observed among patients seen within 3 months, a more favourable benchmark. We also explored whether receipt of rheumatology care was associated with patient and family physician characteristics, and measures of rheumatology supply. We found that patients of higher SES were more likely to receive timely rheumatology care, which has also been demonstrated in other Canadian provinces.29 30 Further, proximity to and density of rheumatologists were important determinants of timely rheumatology care.

While our results appear encouraging, 41% of patients are still not seen within 3 months of a primary care diagnosis as recommended by current guidelines. Thus, an important proportion of patients are not receiving optimal care. When interpreting the results it is important to recognise that the delay in rheumatology consultation being studied represents only a proportion of the total delay from the onset of the patients’ symptoms. While a previous study reported that the patient delay is very small relative to the family physician delay,31 in our study, it is unknown how long patients have symptoms before seeking medical care, or remain in primary care before their RA is recognised. Therefore, the delays between onset of symptoms to rheumatology care may be larger than that reported here. Conversely, we are also unaware of the disease activity and functional status of the subgroup of patients who do not receive timely rheumatology care within 3 months. Recent data from a large early arthritis clinic indicated that 60% of patients had self-limited symptoms.32 Therefore, a delay of 3 months in receipt of rheumatology care may not always be as deleterious to the likelihood of a good response or remission.33

Given the high economic impact of RA,34 rheumatologists are key to an integrated healthcare delivery system.35 However, not all patients are receiving the right care at the right time. Delays in timely consultations may reflect the growing burden of RA relative to rheumatology supply. During our study period, the number of rheumatologists in Ontario remained relatively stable (1.5 rheumatologists per 100 000 population).18 36 While most patients with RA were seen by a rheumatologist within 1 year, delays in more timely benchmarks may also be indicative of the need to educate primary care physicians to initiate rheumatology referrals sooner. Ultimately, delays in access to timely quality care and treatment result in increasing disability for patients with RA as well as increasing costs to the healthcare system.34

Geographical variation in receipt of timely rheumatology care may be indicative of problems with access. Considering the geographical size and features of Ontario, approximately one-quarter of Ontarians reside in communities with 30 000 or fewer residents.37 However, few rheumatologists practice in rural communities.18 Consequently, the threshold for referral to rheumatologists may be higher in remote versus urban communities (ie, rural patients who are referred have substantially more active disease than their urban counterparts).6 36 Thus, there is a need to address the low rheumatology supply among remote communities.

In addition, there was a low likelihood of being seen by a rheumatologist within 6 or 12 months subsequent to a hospital encounter for RA after a patient was initially diagnosed in a primary care setting. In areas with few rheumatologists, family physicians may have no choice but to encourage patients to seek hospital-based specialty care. Also, while most rheumatologists have a hospital appointment, not all hospitals have rheumatologists.38 Thus, our findings reinforce the need for strategies to not only improve access to rheumatologists but also to encourage proper follow-up for these patients.

Our results showed that patients of female family physicians were more likely to receive rheumatology care earlier. While there are conflicting data on the influence of physician gender on practice styles,39 40 female physicians have been shown to engage in more preventive services and to communicate differently with their patients.41 Male physicians may have more confidence in managing RA in primary care, such as starting glucocorticoids prior to rheumatology encounters. Similarly, patients have also reported to have more confidence in male physicians,42 and thus may be more hesitant to seek secondary care. Together, this may explain why patients with RA of female family physicians are more likely to be seen by rheumatologists earlier and that the influence of physician gender was attenuated at 1-year postinitial RA diagnosis.

We also sought to evaluate the influence of primary care models on rheumatology encounters. We hypothesised that patients of capitation models, which involve interdisciplinary teams, allied health providers and where patient enrolment is most strongly encouraged, could improve continuity of care with their patients that could ultimately affect the quality of care that these patients receive. While we found no association, it may be too soon to determine an effect as many physicians changed models over time and few physicians were practising under a capitation model during the study period.43

Strengths of our study include its large sample and the use of a validated population-based RA cohort.21 Our main limitation is that our cohort definition requires patients to have had their first RA diagnosis code provided by a family physician (ie, those whose physician strongly suspects that the patient has RA). While others have used this approach,9 our analyses are likely restricted to patients with a more homogeneous clinical presentation (such as rheumatoid factor positive patients) or those with more active disease in which the family physician was able to accurately diagnose the condition and/or more likely to use an RA billing code as a reason for visit. Therefore, we may be overestimating the proportion of patients with timely rheumatology encounters. These related caveats are owing to the absence of symptom onset and date of referral in health administrative databases. Future research is required to develop and validate algorithms to better predict RA onset from administrative data. However, previous researchers have also used physician service claims to sample patients with RA from rheumatology practices in order to calculate wait times on a smaller scale, and these studies may be subjected to similar biases (inclusion of early patients with RA with a more homogenous clinical presentation).9 44

In conclusion, we found increasing access to rheumatologists within 6 and 12 months over time; however, rheumatology encounters within 3 months did not change over time. Measures of poor access negatively impacted rates of encounters with a rheumatologist. Factors that contributed to disparities in rheumatology access included patient SES and physician's gender. Strategies to facilitate more timely access, such as improving proximity to and density of rheumatologists along with family physician education on initiating more timely referrals, are acutely needed.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors contributed substantially to conception and design, or acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data and were involved in drafting the article and gave final approval of the version to be published.

Funding: Financial support provided by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR operating grant 119348). This study was also supported by the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences (ICES), a non-profit research corporation funded by the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care (MOHLTC). The opinions, results, and conclusions herein are those of the authors and are independent from the funding sources. No endorsement by the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences or the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care is intended or should be inferred. This study was performed in the context on the Ontario Best Practices Research Initiative (OBRI), a unique collaboration of rheumatologists, primary care physicians, researchers, patients and other stakeholders seeking to improve the quality of care and clinical outcomes of patients with arthritis across the spectrum of care.

Competing interests: KT holds a CIHR Fellowship Award in Primary Care Research (2011–2013). NI holds a CIHR Fellowship Award in Clinical Research and a Fellowship Award from the Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of Toronto. CB holds a Canada Research Chair in Knowledge Transfer for Musculoskeletal Care (2002–2016) and a Pfizer Research Chair in Rheumatology.

Ethics approval: The study was approved by the Research Ethics Board at Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre, Toronto, Canada.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: There are no additional unpublished data other than that presented in the manuscript. Questions regarding the data presented in the manuscript can be directed to the corresponding author.

References

- 1.Pincus T. Rheumatoid arthritis: a medical emergency? Scand J Rheumatol Suppl 1994;100:21–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moreland LW, Bridges SL., Jr Early rheumatoid arthritis: a medical emergency? Am J Med 2001;111:498–500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Emery P, Breedveld FC, Dougados M, et al. Early referral recommendation for newly diagnosed rheumatoid arthritis: evidence based development of a clinical guide. Ann Rheum Dis 2002;61:290–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Combe B, Landewe R, Lukas C, et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of early arthritis: report of a task force of the European Standing Committee for International Clinical Studies Including Therapeutics (ESCISIT). Ann Rheum Dis 2007;66:34–45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bykerk V. Canadian consensus statement on early optimal therapy in early rheumatoid arthritis. J Can Rheumatol Assoc 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Widdifield J, Bernatsky S, Paterson JM, et al. Quality care in seniors with new-onset rheumatoid arthritis: a Canadian perspective. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2011;63:53–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nell VPK, Machold KP, Eberl G, et al. Benefit of very early referral and very early therapy with disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2004;43:906–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kyburz D, Gabay C, Michel BA, et al. The long-term impact of early treatment of rheumatoid arthritis on radiographic progression: a population-based cohort study. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2011;50:1106–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Feldman DE, Bernatsky S, Houde M, et al. Early consultation with a rheumatologist for RA: does it reduce subsequent use of orthopaedic surgery? Rheumatology (Oxford) 2013;52:452–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van Nies JAB, Krabben A, Schoones JW, et al. What is the evidence for the presence of a therapeutic window of opportunity in rheumatoid arthritis? A systematic literature review. Ann Rheum Dis 2013. Published Online First 9 Apr 2013. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-203130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mierau M, Schoels M, Gonda G, et al. Assessing remission in clinical practice. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2007;46:975–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Emery P, Breedveld FC, Hall S, et al. Comparison of methotrexate monotherapy with a combination of methotrexate and etanercept in active, early, moderate to severe rheumatoid arthritis (COMET): a randomised, double-blind, parallel treatment trial. Lancet 2008;372:375–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Emery P, Salmon M. Early rheumatoid arthritis: time to aim for remission? Ann Rheum Dis 1995;54:944–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sokka T, Hetland ML, Mäkinen H, et al. Remission and rheumatoid arthritis: data on patients receiving usual care in twenty-four countries. Arthritis Rheum 2008;58:2642–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boers M. Understanding the window of opportunity concept in early rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2003;48:1771–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li LC, Badley EM, MacKay C, et al. An evidence-informed, integrated framework for rheumatoid arthritis care. Arthritis Rheum 2008;59:1171–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kralj B, Kantarevic J. Primary care in Ontario: reforms, investments and achievements. 2012. Ontario Medical Review. https://wwwomaorg/Resources/Documents/PrimaryCareFeaturepdf [Google Scholar]

- 18.Widdifield J, Paterson JM, Bernatsky S, et al. The Rising Burden of Rheumatoid Arthritis Surpasses Rheumatology Supply in Ontario. Can J Public Health 2014; in press [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tepper J, Schultz S, Rothwell D, et al. Physician services in rural and Northern Ontario. ICES investigative report. Toronto, ON: Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences, 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Widdifield J, Bombardier C, Bernatsky S, et al. Accuracy of Canadian Health Administrative Databases for identifying patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a validation study using the Medical Records of Primary Care Physicians. 2012 ACR Annual Scientific Meeting [Abstract #926] Arthritis Care Res 2012;65:1582–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Widdifield J, Bernatsky S, Paterson JM, et al. Accuracy of Canadian health administrative databases in identifying patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a validation study using the medical records of rheumatologists. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2013;65:1582–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chan B, Schultz S. Supply and utilization of general practitioner and family physician services in Ontario. Toronto, ON: Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences, 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Improving health care data in Ontario ICES Investigative Report. Toronto: Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences, 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 24.The Johns Hopkins Adjusted Clinical Group (ACG) Case-Mix System. http://acg.jhsph.edu. Secondary The Johns Hopkins Adjusted Clinical Group (ACG) Case-Mix System. http://acg.jhsph.edu

- 25.Starfield B. Primary care: balancing health needs, services and technology. New York: Oxford University Press, 1998:35–54 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care M Local health integration networks. Secondary Local Health Integration Networks, 2006. http://www.lhins.on.ca/ [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care M Health Force Ontario: family practice models. Secondary Health Force Ontario: Family Practice Models, 2013. http://www.healthforceontario.ca/en/Home/Physicians/Training_%7C_Practising_in_Ontario/Physician_Roles/Family_Practice_Models [Google Scholar]

- 28.Glazier R, Zagorski B, Rayner J. Comparison of Primary Care Models in Ontario by Demographics, Case Mix and Emergency Department Use, 2008/09 to 2009/10. ICES Investigative Report. Toronto: Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lacaille D, Anis AH, Guh D, et al. Gaps in care for rheumatoid arthritis: a population study. Arthritis Rheum 2005;53:241–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Feldman DE, Bernatsky S, Haggerty J, et al. Delay in consultation with specialists for persons with suspected new-onset rheumatoid arthritis: a population-based study. Arthritis Rheum 2007;57:1419–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.van der Linden MPM, le Cessie S, Raza K, et al. Long-term impact of delay in assessment of patients with early arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2010;62:3537–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Visser H, le Cessie S, Vos K, et al. How to diagnose rheumatoid arthritis early: a prediction model for persistent (erosive) arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2002;46:357–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Puolakka K, Kautiainen H, Mottonen T, et al. Impact of initial aggressive drug treatment with a combination of disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs on the development of work disability in early rheumatoid arthritis: a five-year randomized followup trial. Arthritis Rheum 2004;50:55–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bombardier C, Hawker G, Mosher D. The impact of arthritis in Canada: today and over the next 30 years. Arthritis Alliance of Canada, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gabriel S, Wagner J, Zinsmeister A, et al. Is rheumatoid arthritis care more costly when provided by rheumatologists compared with generalists? Arthritis Rheum 2001;44:1504–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Widdifield J, Paterson JM, Bernatsky S, et al. Epidemiology of rheumatoid arthritis in Ontario, Canada. Arthritis & Rheumatism, 2013;[in press]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Glazier R, Gozdyra P, Yeritsyan N. Geographic access to primary care and hospital services for rural and northern communities. Toronto, ON: Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hawker G, Badley E, Jaglal S, et al. Project for an Ontario women's health evidence-based report: musculoskeletal conditions. In: Bierman A, ed. Toronto: St. Michael's Hospital and the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Badley E, Veinot P, Ansari H, et al. Arthritis Community Research and Evaluation Unit 2007 survey of rheumatologists in Ontario. 2008. http://www.acreu.ca/pdf/pub5/08-03.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 40.Meeuwesen L, Schapp C, Van der Staak C. Verbal analysis of doctor-patient communication. Soc Sci Med 1991;32:1143–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bensing JM, van den Brink-Muinen A, de Bakker DH. Gender differences in practice style: a Dutch study of general practitioners. Med Care 1993;31:219–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bertakis KD, Helms LJ, Callahan EJ, et al. The influence of gender on physician practice style. Med Care 1995;33:407–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hall JA, Blanch-Hartigan D, Roter DL. Patients’ satisfaction with male versus female physicians: a meta-analysis. Med Care 2011;49:611–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jamal S, Alibhai SMH, Badley EM, et al. Time to treatment for new patients with rheumatoid arthritis in a major metropolitan city. J Rheumatol 2011;38:1282–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.