Keywords: Endemism, Genome size, Island flora, Low-copy nuclear markers, Molecular dating

Highlights

-

•

Analyses showed resolution among 1/3 of the Diospyros species form NC clade III.

-

•

Some morphological distinct species could not be discriminated with the markers used.

-

•

Diospyros arrived relative recently (5–20 mya) in New Caledonia.

-

•

Chromosome counts confirmed the investigated species to be diploid.

-

•

Genome sizes varied nearly fourfold among species examined.

Abstract

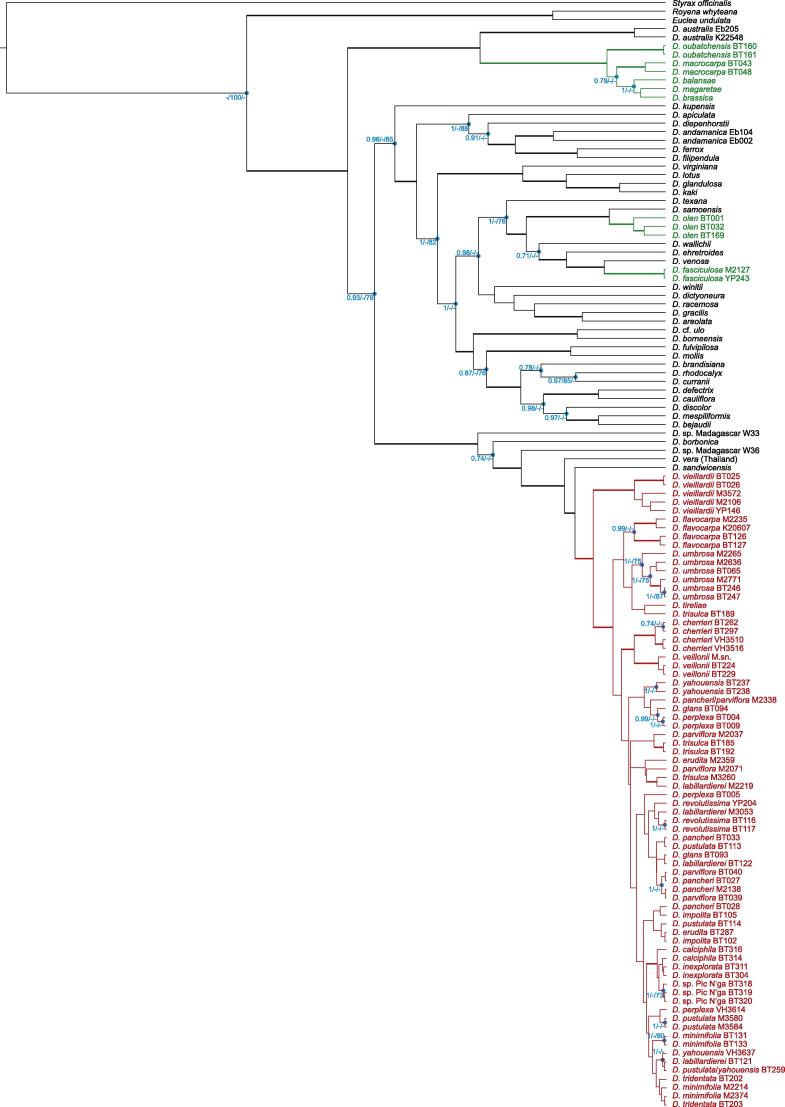

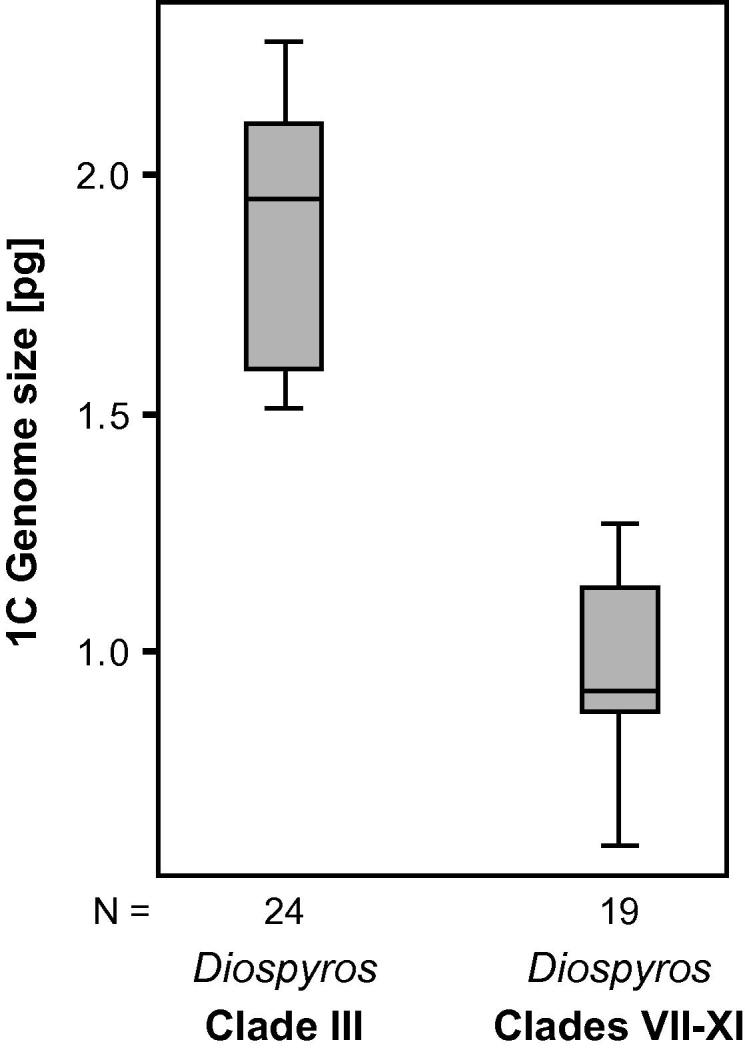

To clarify phylogenetic relationships among New Caledonian species of Diospyros, sequences of four plastid markers (atpB, rbcL, trnK–matK and trnS–trnG) and two low-copy nuclear markers (ncpGS and PHYA) were analysed. New Caledonian Diospyros species fall into three clades, two of which have only a few members (1 or 5 species); the third has 21 closely related species for which relationships among species have been mostly unresolved in a previous study. Although species of the third group (NC clade III) are morphologically distinct and largely occupy different habitats, they exhibit little molecular variability. Diospyros vieillardii is sister to the rest of the NC clade III, followed by D. umbrosa and D. flavocarpa, which are sister to the rest of this clade. Species from coastal habitats of western Grande Terre (D. cherrieri and D. veillonii) and some found on coralline substrates (D. calciphila and D. inexplorata) form two well-supported subgroups. The species of NC clade III have significantly larger genomes than found in diploid species of Diospyros from other parts of the world, but they all appear to be diploids. By applying a molecular clock, we infer that the ancestor of the NC clade III arrived in New Caledonia around 9 million years ago. The oldest species are around 7 million years old and the youngest ones probably much less than 1 million years.

1. Introduction

New Caledonia is an island group located in the southwestern Pacific about 1300 km east of Australia, ranging from around 19° to 23° south with an land area of ca. 19,000 km2. It consists of the main island Grande Terre (ca. 16,000 km2), Iles Belep (in the north), Ile des Pins (in the south), Loyalty Islands (in the east) and several other smaller islands. The continental part of New Caledonia (mainly Grande Terre) separated from Gondwanan during late Cretaceous (ca. 80 million years ago, mya; McLoughlin, 2001). During the Palaeocene to late Eocene, this continental sliver was submerged for at least 20 million years (myr), and a thick layer of oceanic mantle accumulated (Pelletier, 2006). After Grande Terre re-emerged in the late Eocene (37 mya), this heavy-metal rich oceanic material covered most of the land. Today, around 1/3 of the main island is still covered with ultramafic substrates. Because Grande Terre was totally submerged, it is highly unlikely that lineages that were already present in this area before the split from Gondwanan could have survived locally. Current hypotheses suggest that biota present today are derived from elements/ancestors that reached New Caledonia via long distance dispersal (e.g. Morat et al., 2012; Pillon, 2012; Grandcolas et al., 2008) mainly from Australia, New Guinea and Malaysia. Hypotheses of other islands between Australia and New Caledonia having served as stepping stones or refuges for Gondwanan taxa now endemic (e.g. Amborella) have been proposed by a few authors (Ladiges and Cantrill, 2007), but there is no consensus of when they existed or how large and numerous they might have been. The New Caledonian climate is tropical to subtropical. The main island is split by a mountain range into a humid eastern portion (2000–4000 mm precipitation per year) and a dry western part (1000 mm precipitation per year) with prevailing winds and rain coming from the south east. New Caledonia is one of the 34 biodiversity hotspots (Mittermeier et al., 2004; Myers et al., 2000), and nearly 75% of the native flora is endemic (Morat et al., 2012), which is the fourth highest for an island (Lowry, 1998). Among these endemic taxa are 98 genera and three families, Amborellaceae, Oncothecaceae and Phellinaceae (Morat et al., 2012). One of the reasons hypothesised for the high level of endemism found in New Caledonia is the ultramafic substrates, which have acted as a filter for colonising species that were already pre-adapted to this special soil (Pillon et al., 2010).

Ebenaceae are pantropical and belong to the order Ericales (APG, 2009); the majority of species occur in Africa (incl. Madagascar) and the Indo-Pacific region. Duangjai et al. (2006) divided Ebenaceae into two sub families, Lissocarpoideae and Ebenoideae. Lissocarpoideae are monogeneric (Lissocarpa, 8 species in northwestern South America), and Ebenoideae include Diospyros, Euclea (18 species in Africa) and Royena (17 species in Africa). This classification of Ebenaceae in two subfamilies and four genera has been also supported by palynological data (Geeraerts et al., 2009).

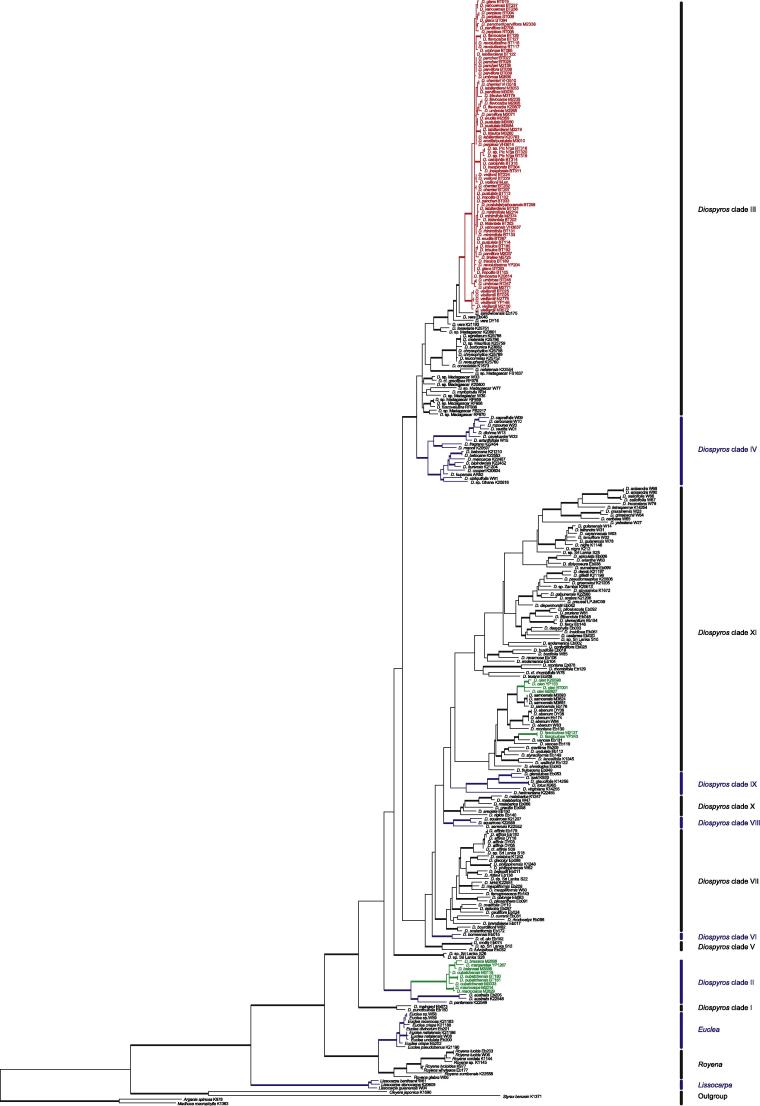

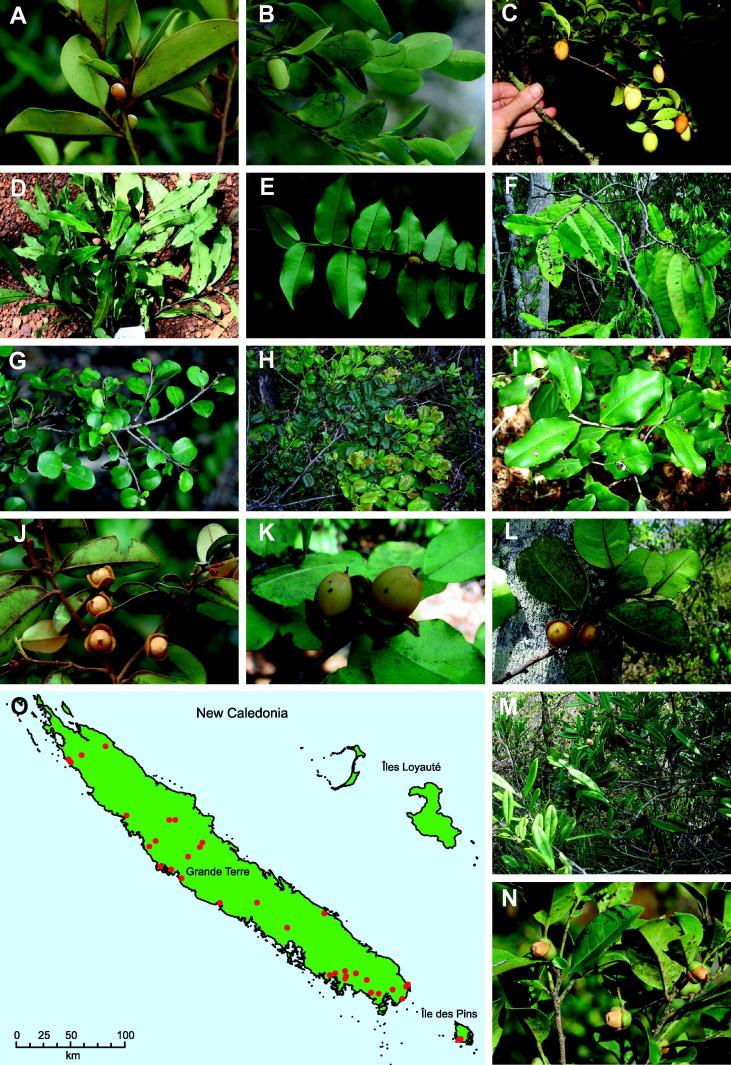

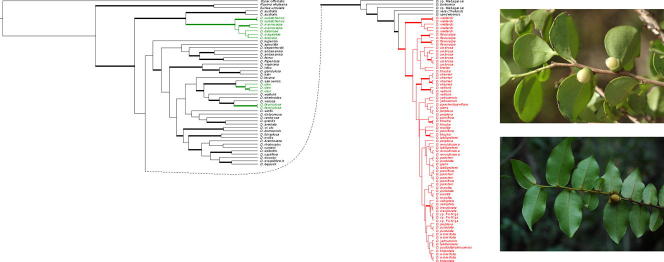

In this paper, we use the circumscription of Diospyros as proposed by Duangjai et al. (2006). Diospyros is the largest genus of Ebenaceae with more than 500 species, making it also one of the largest angiosperm genera. The greatest species of diversity is in Asia and the Pacific region (∼300 species). Fruits of some species (persimmons; e.g. D. kaki, D. lotus and D. virginiana) are edible, and ebony wood (e.g. D. ebenum) is one of the most expensive timbers. Species of Diospyros are shrubs or trees that occur in most tropical and subtropical habitats, where they are often important and characteristic elements. Duangjai et al. (2009) found 11 mostly well-resolved clades within Diospyros. In New Caledonia, there are 31 described Diospyros species, of which all but one are endemic, and they belong to three clades (Duangjai et al., 2009; Fig. 4, clades II, III and XI). The first clade (clade II) contains five species from New Caledonia that are related to Australian species of Diospyros. The second clade (clade III) includes species from Hawai‘i, Indian Ocean islands and 24 taxa from New Caledonia, within which the species from New Caledonia form a sublcade, here termed NC clade III. Although Duangjai et al. (2009) analysed more than 8000 base pairs of plastid DNA, low variability and little resolution was found among these endemic New Caledonian species. The third clade (clade XI), consisting of taxa from Asia, America, Pacific Islands and New Caledonia, includes two Diospyros species from New Caledonia, one endemic and the other found throughout the southern Pacific. These two species are not sister species, accounting for two more colonisations of New Caledonia (i.e. four in total). Similar, multiple colonisation events are also found among other organisms in New Caledonia (e.g. Murienne et al., 2005). Diospyros is observed in all types of New Caledonian vegetation except mangrove; the species range from sea level up to ca. 1250 m (New Caledonia’s highest point is 1628 m). There are several micro-endemics restricted to just a small area (White, 1992). Most New Caledonian Diospyros species from clade III are morphologically clearly defined and restricted by edaphic factors and occur on just one substrate type. For example, D. labillardierei (Fig. 1D) is distinctive with its long narrow leaves and Salix-like habit; it is a rheophyte on non-ultramafic substrates. Diospyros veillonii (Fig. 1F) is a remarkable species with coralloid inflorescence axes (unique among New Caledonian Diospyros) and large leaves, but is known from only a single locality in dry forest on black clay soil. Other species have broader distributions and ecologies, such as D. parviflora (Fig. 1J), which grows on both ultramafic and non-ultramafic substrates and is widespread throughout Grande Terre and Balabio Island in dense humid forests as well as in more open and dry vegetation. Some species can have similar ecological requirements, but are morphologically well differentiated; for example D. vieillardii (Fig. 1A) has a calyx narrower than its prune-like fruit, whereas D. glans (Fig. 1N) has a thick calyx much wider than its fruit, but both grow in maquis vegetation and co-occur at some sites.

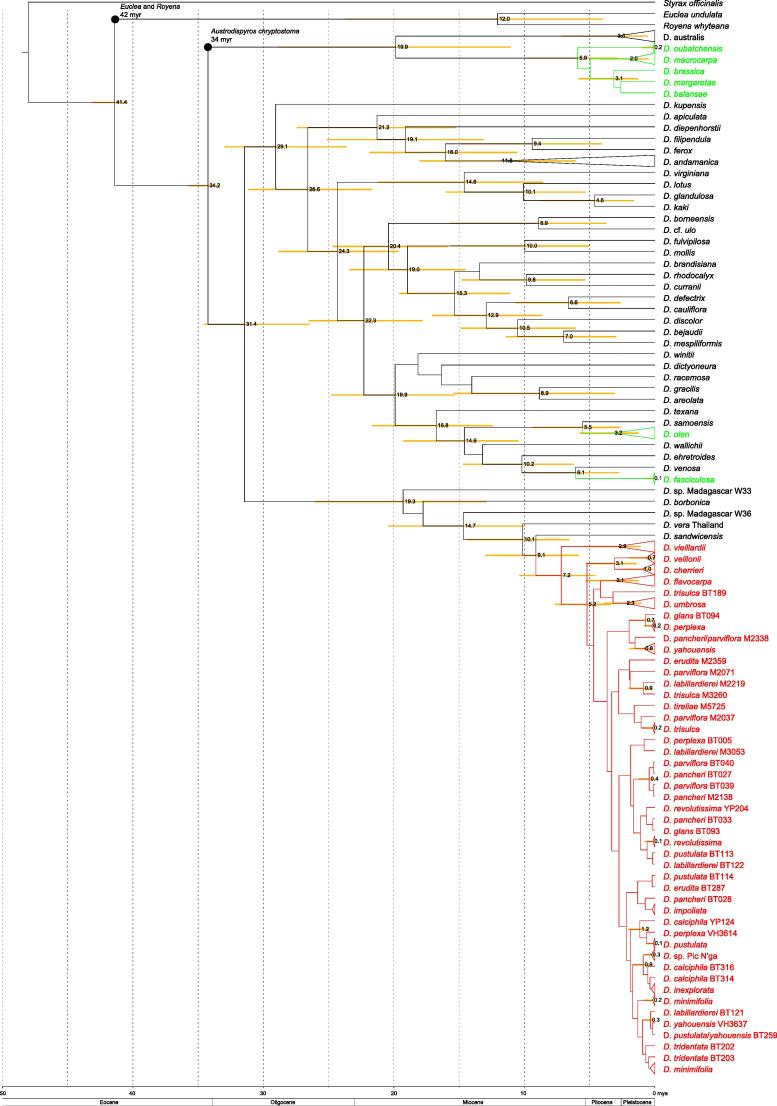

Fig. 4.

One of 210 equally parsimonius trees of the plastid data set. Clades are named according to Duangjai et al. (2009). Bold branches have more than 70% support in all three analysis. New Caledonian taxa are coloured, red represents clade III NC.

Fig. 1.

Examples of Diospyros species from New Caledonia (A–N) and Map of New Caledonia with collection points (O). A: D. vieillardii; B: D. umbrosa; C: D. flavocarpa, D: D. labillardierei; E: D. pancheri, F: D. veillonii; G: D. minimifolia; H: D. pustulata; I: D. cherrieri; J: D. parviflora; K: D.perplexa; L: D. yaouhensis; M: D. revolutissima; N: D. glans; O: Map of New Caledonia with sampling localities. Photographs taken by: C. Chambrey (I), V. Hequet (F, K, L), J. Munzinger (A, B, C, E, G, H, J, M, N) and B. Turner (D).

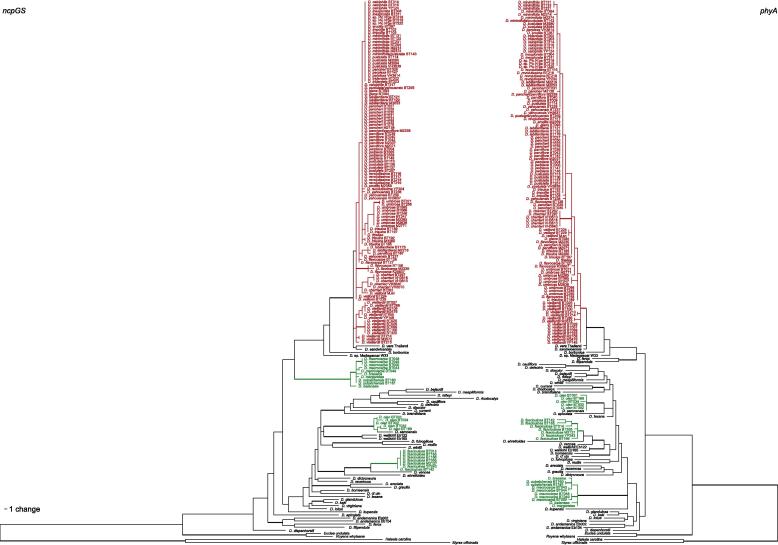

For establishing phylogenetic relationships, sequences of low-copy nuclear genes are not as often used as regions from the plastid genome, often due to methodological difficulties. Low-copy genes are present in one or few copies in the genome, and primers are often highly specific for individual groups, requiring them therefore to be newly designed for each study. On the other hand, low-copy nuclear markers are normally highly informative and as they are biparentally inherited they may also help detect recent hybridization (e.g. Moody and Rieseberg, 2012). However, in a study of Hawaiian endemics in two unrelated genera, Pillon et al. (2013) found that although two low-copy nuclear loci displayed a high level of variability, they also exhibited heterozygosity, intraspecific variation, and retention of ancient alleles; allele coalescence was older than the species under study. Nonetheless, we hoped that inclusion of low-copy nuclear genes might provide additional insight into species relationships and thus included two such loci. Phytochrome A (PHYA) belongs to the gene family of the phytochromes, which has eight members across the seed plants (PHYA–PHYE in angiosperms and PHYN–PHYP in gymnosperms); PHYN/PHYA, PHYO/PHYC and PHYP/PHYBDE are orthologs, the rest being paralogs of the others (Mathews et al., 2010). Genes of this family encode photoreceptor proteins that mediate developmental responses to red and far red light. The three main paralogs (PHYA, PHYB and PHYC) are different enough to be amplified with specific primers (Zimmer and Wen, 2012). Sequences of phy genes have been used successfully across the flowering plants (e.g. Mathews et al., 2010; Nie et al., 2008; Bennett and Mathews, 2006) for phylogenetic reconstruction. The gene PHYA used in this study consists of four exons and three introns. Glutamine synthetase (GS), codes for a protein involved in nitrogen assimilation. There are two main types of GS genes, cytosolic- and chloroplast-expressed. Chloroplast-expressed glutamine synthetase (ncpGS) consists of 12 exons and 11 introns and has been shown to be a single-copy gene in plants (Emshwiller and Doyle, 1999). This combination of coding and non-coding regions has been shown to be highly informative for inferring phylogenetic trees of various groups (e.g. Oxalidaceae, Emshwiller and Doyle, 1999; Passiflora, Yockteng and Nadot, 2004; Spiraeanthemum, Pillon et al., 2009a; Codia, Pillon et al., 2009b; Achillea millefolium, Guo et al., 2012).

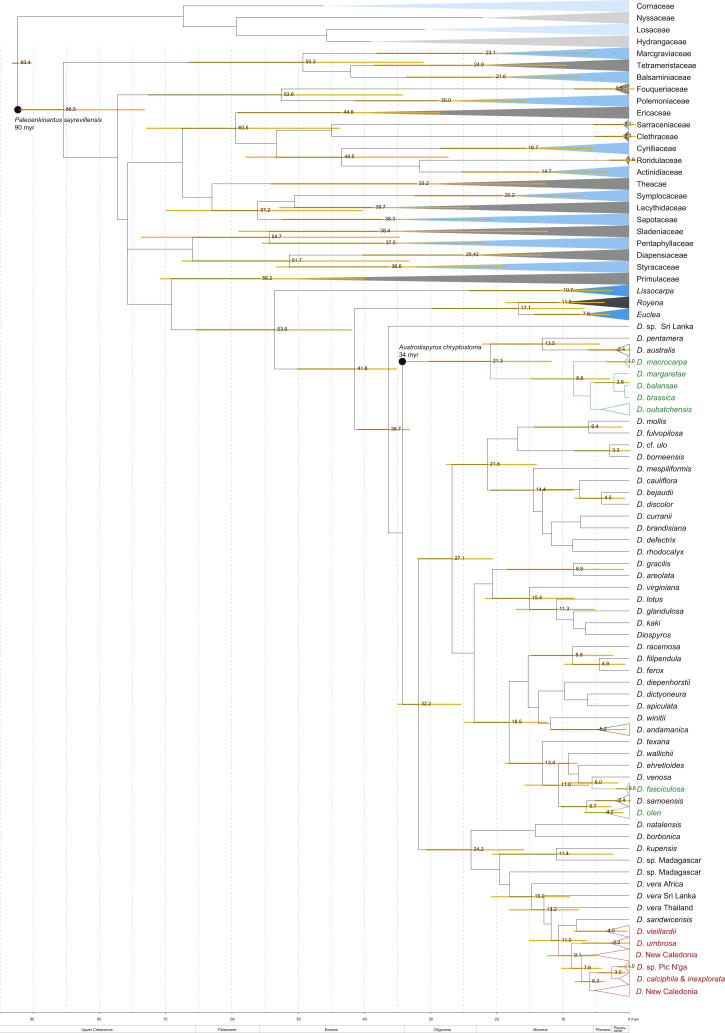

Beside phylogenetic relationships, the age of clades is of interest. In many cases, there are no fossils available for direct dating of a group of interest in a particular region, which is often the case for islands and is certainly true for New Caledonia (the few fossils recorded to date are older than the last emergence of the island and are not certain to be angiosperms; Salard and Avias, 1968). Rates of DNA divergence are generally consistent with a molecular clock (Zuckerkandl and Pauling, 1965), and therefore DNA data contain information about the relative ages of taxa. When substitution rates (e.g. Silvestro et al., 2011; Alba et al., 2000) or fossils belonging to defined clades (e.g. Pirie and Doyle, 2012; Magallón, 2010) are taken into consideration, the relative ages obtained can be transformed into absolute ages. Placement of fossils in the correct position in the phylogenetic tree is crucial for accurate interpretation (Forest, 2009). Some previous studies have has been published on the subject of the age of asterids (e.g. Millán-Martínez, 2010; Bell et al., 2010; Bremer et al., 2004) to which Ericales belong, and fossil Diospyros are known from some localities (mainly in India and North America), but none has been found in New Caledonia. Austrodiospyros cryptostoma (Basinger and Christophel, 1985), a fossil from Australia has many morphological similarities to D. australis of clade II (Duangjai et al., 2009). It is thus far the only fossil belonging to a clade that includes Diospyros species from New Caledonia. We treat A. cryptostoma as member of clade II in this study.

Genome sizes vary nearly 2400-fold across angiosperms (Pellicer et al., 2010). Most variation in DNA amount is caused by different amounts of non-coding, repetitive DNA, such as pseudogenes, retrotransposons, transposons and satellite repeats (Leitch, 2007; Bennett and Leitch, 2005; Parisod et al., 2009; Petrov, 2001). Genome sizes and chromosome numbers of Diospyros are within the range of those of other members of Ericales (Bennett and Leitch, 2010). Nuclear DNA amounts in Diospyros range from 0.78 pg (1C-value) in diploid D. rhodocalyx up to 4.06 pg in nonaploid D. kaki cultivars (Tamura et al., 1998). The basic chromosome number in Diospyros is 2n = 2x = 30, and most species seem to be diploid (e.g. Tamura et al., 1998; White, 1992). There are some reports of polyploid Diospyros, mostly from cultivated species (e.g. D. rhombifolia 4x, D. ebenum 6x, D. kaki 6x and 9x, D. virginiana 6x and 9x; Tamura et al., 1998). White (1992) provided chromosome counts for nine New Caledonian species of Diospyros (D. calciphila, D. fasciculosa, D. flavocarpa, D. minimifolia, D. olen, D. parviflora, D. umbrosa, D. vieillardii and D. yaouhensis), all of which are diploid.

Duangjai et al. (2009) found little sequence variation in the markers investigated among many species from NC clade III, which could indicate recent diversification. White (1992), who described most the New Caledonian Diospyros species, suspected some hybridization was taking place. The main aim of this study was to clarify relationships among New Caledonian Diospyros species, especially of those belonging to clade III (Duangjai et al., 2009). Furthermore, if we were able to find more variable than those previously studied, we wanted to elucidate potential factors underlying speciation (e.g. ecological speciation, hybrid speciation and introgression) and understand better differences in speciation rates of the clades that reached New Caledonia independently. We used low-copy nuclear markers, PHYA and ncpGS because they offered the prospect of resolving relationships within this clade and detecting possible hybrid species. We also included samples from nine additional species that were not available for the study of Duangjai et al. (2009). Moreover, we conducted dating analyses to obtain estimates of the ages for the lineages to which New Caledonian Diospyros species belong. We also present chromosome numbers and genome sizes of some additional New Caledonian species of Diospyros; we wished to examine further the hypothesis that polyploidy (perhaps involving hybridization) might have played a role in producing diversity in this comparatively species-rich clade.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Material

Material from New Caledonian Diospyros species was collected by B. Turner (BT), J. Munzinger (JM), Yohan Pillon (YP) or Vanessa Hequet (VH). When fertile, a voucher was made with several duplicates sent to various herbaria. When sterile, one voucher per population was taken; this was compared to already existing collections in Noumea Herbarium (NOU) from the same location and referred to that species if similar. One putatively new species was detected while doing fieldwork for this project, here called D. sp. Pic N’ga. Other Ebenaceae samples are from previous studies (Duangjai et al., 2009). Outgroup taxa and a few Diospyros samples were taken from the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, DNA Bank (http://apps.kew.org/dnabank/homepage.html). Compared to the sampling of Duangjai et al. (2009), we added material of the following New Caledonian species: D. erudita, D. glans, D. impolita, D. inexplorata, D. margaretae, D. tireliae, D. tridentata, D. trisulca and D. veillonii (for details see Table 1). The three un-sampled species from New Caledonia (D. fastidiosa, D. nebulosa and D. neglecta) are rare and have not been seen after their description.

Table 1.

Table of accessions; showing all individuals used in this study. Sequences provided by S. Duangjai are indicated.

| Taxon | Acc.-nr. | Origin | Voucher | Herbarium | atpB | rbcL | matK & trnK intron | trnS–trnG | ncpGS | PHYA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D. abyssinica (Hiern) F. White | K1672 | Africa | Gilbert & Sebseke 8803 | K | DQ923883 | EU980646 | DQ923990 | EU981061 | ||

| D. affinis Thwaites | DY03 | Sri Lanka | Yakandawala 03 | PDA | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | KF291310 | ||

| D. affinis | DY05 | Sri Lanka | Yakandawala 05 | PDA | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | KF291311 | ||

| D. affinis | DY18 | Sri Lanka | Yakandawala 18 | PDA | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | KF291312 | ||

| D. affinis | Eb179 | Sri Lanka | Samuel s.n. | PDA | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | KF291313 | ||

| D. affinis | Eb180 | Sri Lanka | Samuel s.n. | PDA | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | KF291314 | ||

| D. cf. affinis | S09 | Sri Lanka | Samuel 09 | PDA | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | KF291315 | ||

| D. andamanica (Kurz) Bakh. | Eb002 | Thailand | Duangjai 068 | KUFF, W | DQ923884 | EU980645 | DQ923991 | EU981060 | KF291447 | KF291624 |

| D. andamanica | Eb104 | Thailand | Duangjai 162 | KUFF, W | DQ923950 | EU980755 | DQ924057 | EU981170 | KF291448 | KF291625 |

| D. anisandra S.F. Blake | W68 | Guatemala | Wallnöfer 6012 | W | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | KF291316 | ||

| D. anisandra | W80 | Guatemala | Frisch 2006-1 | W | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | KF291317 | ||

| D. apiculata Hiern | Eb006 | Thailand | Duangjai 072 | KUFF | EU980813 | EU980647 | EU980936 | EU981062 | KF291449 | KF291626 |

| D. areolata King & Gamble | Eb160 | Brunei | Duangjai et al. 33 | BRUN, W, WU | Duangjai unpubl | Duangjai unpubl | Duangjai unpubl | KF291318 | KF291450 | KF291627 |

| D. artanthifolia Mart. ex Miq. | W15 | Peru | Pirie 62 | W | DQ923885 | EU980648 | DQ923992 | EU981063 | ||

| D. australis (R.Br) Hiern | Eb205 | Australia | Wallnöfer & Duangjai 13944 | WU | DQ923887 | EU980650 | DQ923994 | EU981065 | ||

| D. australis | K22548 | Australia | Forster 7848 | K | DQ923886 | EU980649 | DQ923993 | EU981064 | ||

| D. balansae Guillaumin | M3556 | New Caledonia | Munzinger 3556 | NOU015466 | EU980814 | EU980651 | EU980937 | EU981066 | KF291451 | KF291628 |

| D. batocana Hiern | K21210 | Namibia | Steyl 88 | K | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | KF291319 | ||

| D. batocana | K22553 | Zambia | Pope et al. 2196 | K | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | KF291320 | ||

| D. bejaudii Lecomte | Eb011 | Thailand | Duangjai 075 | KUFF, W | DQ923888 | EU980652 | DQ923995 | EU981067 | KF291452 | KF291629 |

| D. bipindensis Gürke | K22452 | Gabon | Stone & Niangadouma 3554 | MO | DQ923889 | EU980653 | DQ923996 | EU981068 | ||

| D. borbonica I. Richardson | K23682 | Reunion | Chase REU10042 | REU, WU | EU980815 | EU980654 | EU980938 | EU981069 | KF291453 | KF291630 |

| D. borneensis Hiern | Eb015 | Thailand | Duangjai 079 | KUFF, W | DQ923890 | EU980655 | DQ923997 | EU981070 | KF291454 | KF291631 |

| D. bourdillonii Brandis | W82 | India | DeFranceschi 18.12.2006 | W | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | KF291321 | ||

| D. brandisiana Kurz | Eb017 | Thailand | Duangjai & Sinbumrung 007 | KUFF, W | DQ923891 | EU980656 | DQ923998 | EU981071 | KF291455 | KF291632 |

| D. brassica F. White | M2898 | New Caledonia | Munzinger 2898 | NOU007949 | DQ923892 | EU980657 | DQ923999 | EU981072 | KF291456 | KF291633 |

| D. buxifolia (Blume) Hiern | Eb018 | Thailand | Duangjai 081 | KUFF, W | EU980816 | EU980658 | EU980939 | EU981073 | ||

| D. buxifolia | W85 | India | DeFranceschi 18.12.2006 | W | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | KF291322 | ||

| D. calciphila F. White | BT314 | New Caledonia | Munziner et al. 6650 | MPU, NOU, P | KF291801 | KF291860 | KF291919 | KF291323 | KF291457 | KF291634 |

| D. calciphila | BT316 | New Caledonia | Munziner et al. 6650 | MPU, NOU, P | KF291802 | KF291861 | KF291920 | KF291324 | KF291458 | KF291635 |

| D. calciphila | BT317 | New Caledonia | Munziner et al. 6653 | MPU, NOU, P | KF291459 | KF291636 | ||||

| D. calciphila | YP124 | New Caledonia | Pillon 124 | NOU006325 | KF291460 | KF291637 | ||||

| D. capreifolia Mart. ex Hiern | W09 | French Guiana | Prévost & Sabatier 3476 | W | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | KF291325 | ||

| D. carbonaria Benoist | W10 | French Guiana | Prévost & Sabatier 3470 | W | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | KF291326 | ||

| D. caribaea (A.DC.) Standl. | W65 | Cuba | Abbott 19004 | W | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | KF291327 | ||

| D. castanea (Craib) Fletcher | Eb020 | Thailand | Duangjai 083 | KUFF, W | DQ923893 | EU980660 | DQ924000 | EU981075 | ||

| D. cauliflora Blume | Eb024 | Thailand | Duangjai 087 | KUFF, W | DQ923894 | EU980661 | DQ924001 | EU981076 | KF291461 | KF291638 |

| D. cavalcantei Sothers | W22 | French Guiana | Prévost et al. 4671 | W | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | KF291328 | ||

| D. cayennensis A.DC. | W03 | French Guiana | Prévost 3430 | W | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | KF291329 | ||

| D. celebica Bakh. | K1242 | Indonesia | Chase 1242 | K | DQ923897 | EU980664 | DQ924004 | EU981079 | ||

| D. cherrieri F. White | BT262 | New Caledonia | Chambrey & Turner 16 | NOU079551, WU062860 | KF291803 | KF291862 | KF291921 | KF291330 | KF291463 | KF291640 |

| D. cherrieri | BT297 | New Caledonia | Chambrey & Turner 17 | NOU079547 | KF291804 | KF291863 | KF291922 | KF291331 | KF291464 | KF291641 |

| D. cherrieri | VH3510 | New Caledonia | Hequet 3510 | NOU015245 | EU980818 | EU980665 | EU980941 | EU981080 | KF291465 | KF291642 |

| D. cherrieri | VH3516 | New Caledonia | Hequet 3516 | NOU015251 | EU980819 | EU980666 | EU980942 | EU981081 | KF291466 | KF291643 |

| D. cherrieri | VH3610 | New Caledonia | Hequet 3610 | NOU016962 | KF291467 | KF291644 | ||||

| D. cherrieri | VH3640 | New Caledonia | Hequet 3640 | NOU017014 | KF291468 | KF291645 | ||||

| D. chrysophyllos Poir. | K25758 | Mauritius | Page 45 | MAU | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | KF291332 | ||

| D. chrysophyllos | K25769 | Mauritius | Page 71 | MAU | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | KF291333 | ||

| D. clementium Bakh. | Eb154 | Brunei | Duangjai et al. 24 | BRUN, W, WU | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | KF291334 | ||

| D. confertiflora (Hiern) Bakh. | Eb028 | Thailand | Duangjai 091 | KUFF, W | DQ923898 | EU980667 | DQ924005 | EU981082 | ||

| D. consolatae Chiov. | K1673 | Africa | Beentje 2168 | K | DQ923899 | EU980668 | DQ924006 | EU981083 | ||

| D. cooperi (Hutchinson & Dalziel) F. White | K20604 | Ghana | Merello et al. 1350 | MO | DQ923900 | EU980669 | DQ924007 | EU981084 | ||

| D. crassinervis (Krug & Urb.) Standl. | W23 | Cuba | Rainer s.n. | W | DQ923901 | EU980670 | DQ924008 | EU981085 | ||

| D. curranii Merr. | Eb031 | Thailand | Duangjai 094 | KUFF, W, WU | DQ923902 | EU980671 | DQ924009 | EU981086 | KF291469 | KF291646 |

| D. dasyphylla Kurz | Eb033 | Thailand | Duangjai 096 | KUFF, W | DQ923903 | EU980672 | DQ924010 | EU981087 | ||

| D. defectrix Fletcher | Eb097 | Thailand | Duangjai 155 | KUFF, WU | KF291805 | KF291864 | KF291923 | KF291335 | KF291470 | KF291647 |

| D. dendo Welw. ex Hiern | K21197 | Central African Republic | Harris & Fay 1594 | K | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | KF291336 | ||

| D. dichroa Sandwith | W13 | French Guiana | Sabatier et al. 4457 | W | DQ923904 | EU980673 | DQ924011 | EU981088 | ||

| D. dictyoneura Hiern | Eb038 | Thailand | Duangjai 100 | KUFF, W | EU980674 | EU980820 | EU980943 | EU981089 | KF291471 | KF291648 |

| D. diepenhorstii Miq. | Eb042 | Thailand | Duangjai 103 | KUFF, W | DQ923905 | EU980675 | DQ924012 | EU981090 | KF291472 | KF291649 |

| D. discolor Willd. | Eb088 | Thailand | Duangjai 146 | KUFF, WU | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | KF291337 | KF291473 | KF291650 |

| D. ebenum J. Koenig ex Retz | DY06 | Sri Lanka | Yakandawala 06 | PDA | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | KF291338 | ||

| D. ebenum | DY08 | Sri Lanka | Yakandawala 08 | PDA | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | KF291339 | ||

| D. ebenum | Eb174 | Sri Lanka | Samuel s.n. | WU | EU980677 | EU980821 | EU980944 | EU981092 | ||

| D. ebenum | W83 | India | Ramesh Diosass-2 | W | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | KF291340 | ||

| D. ebenum | W84 | India | DeFranceschi 21.12.2006 | W | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | KF291341 | ||

| D. egrettarum I. Richardson | K25788 | Mauritius | Page 122 | MAU | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | KF291342 | ||

| D. ehretioides Wall. ex G. Don | Eb043 | Thailand | Duangjai 104 | KUFF, W | DQ923907 | EU980678 | DQ924014 | EU981093 | KF291474 | KF291651 |

| D. eriantha Charmp. ex Benth | W63 | Taiwan | Chung & Anderberg 1401 | HAST | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | KF291343 | ||

| D. erudita F. White | BT287 | New Caledonia | Chambrey & Turner 20 | NOU | KF291806 | KF291865 | KF291924 | KF291344 | KF291475 | KF291652 |

| D. erudita | M2359 | New Caledonia | Munzinger et al. 2359 | NOU003840 | EU980845 | EU980739 | EU980968 | EU981154 | KF291476 | KF291653 |

| D. erudita/pustulata | M3010 | New Caledonia | Munziner et al. 3010 | NOU008358 | EU980841 | EU980735 | EU980964 | EU981150 | ||

| D. fasciculosa (F. Muell.) F. Muell. | BT014 | New Caledonia | Munzinger et al. 6617 | NOU | KF291477 | KF291654 | ||||

| D. fasciculosa | BT142 | New Caledonia | MacKee 27341 | NOU022840 | KF291478 | KF291655 | ||||

| D. fasciculosa | BT165 | New Caledonia | KF291479 | KF291656 | ||||||

| D. fasciculosa | BT166 | New Caledonia | KF291480 | KF291657 | ||||||

| D. fasciculosa | BT335 | New Caledonia | KF291481 | KF291658 | ||||||

| D. fasciculosa | M2127 | New Caledonia | Munzinger 2127 | NOU003604 | DQ923908 | EU980679 | DQ924015 | EU981094 | KF291482 | KF291659 |

| D. fasciculosa | YP243 | New Caledonia | Pillon et al. 243 | NOU010096 | EU980822 | EU980680 | EU980945 | EU981095 | KF291483 | KF291660 |

| D. ferox Bakh. | Eb146 | Brunei | Duangjai et al. 012 | BRUN, W, WU | DQ923909 | EU980681 | DQ924016 | EU981096 | KF291484 | KF291661 |

| D. ferruginescens Bakh. | Eb143 | Brunei | Duangjai et al. 007 | BRUN, W, WU | DQ923911 | EU980685 | DQ924018 | EU981100 | ||

| D. filipendula Pierre ex Lecomte | Eb048 | Thailand | Duangjai 109 | KUFF | DQ923912 | EU980686 | DQ924019 | EU981101 | KF291485 | KF291662 |

| D. flavocarpa (Vieill. ex P. Parm.) F. White | BT126 | New Caledonia | Munzinger et al. 6625 | NOU | KF291807 | KF291866 | KF291925 | KF291345 | KF291486 | KF291663 |

| D. flavocarpa | BT127 | New Caledonia | Munzinger et al. 6625 | NOU | KF291808 | KF291867 | KF291926 | KF291346 | KF291487 | KF291664 |

| D. flavocarpa | BT156 | New Caledonia | Munzinger et al. 6632 | NOU | KF291488 | KF291665 | ||||

| D. flavocarpa | K20607 | New Caledonia | McPherson & Lowry 18563 | NOU022877 | DQ923913 | EU980687 | DQ924020 | EU981102 | KF291489 | KF291666 |

| D. flavocarpa | K20614 | New Caledonia | Lowry et al. 5783 | NOU023319 | EU980870 | EU980782 | EU980993 | EU981197 | ||

| D. flavocarpa | M2235 | New Caledonia | Munzinger 2235 | NOU006659 | EU980825 | EU980688 | EU980948 | EU981103 | KF291490 | KF291667 |

| D. flavocarpa | M2905 | New Caledonia | Munzinger et al. 2905 | NOU007977 | EU980826 | EU980689 | EU980949 | EU981104 | ||

| D. fragrans Gürke | K22454 | Gabon | SIMAB 010610 | MO | DQ923914 | EU980690 | DQ924021 | EU981105 | ||

| D. frutescens Blume | Eb049 | Thailand | Duangjai 110 | KUFF, W | EU980827 | EU980691 | EU980950 | EU981106 | ||

| D. fulvopilosa Fletcher | Eb052 | Thailand | Duangjai 113 | KUFF, W | DQ923915 | EU980692 | DQ924022 | EU981107 | KF291491 | KF291668 |

| D. fuscovelutina Baker | RF938 | Madagascar | RF 938 | W | DQ923979 | EU980803 | DQ924088 | EU981218 | ||

| D. gabunensis Gürke | K22560 | Tanzania | Bidgood et al. 2890 | K | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | KF291347 | ||

| D. gilletii De Wild | K21198 | Cameroon | Harris & Fay 884 | K | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | KF291348 | ||

| D. glandulosa Lace | Eb053 | Thailand | Duangjai 114 | KUFF, W | DQ923916 | EU980693 | DQ924023 | EU981108 | KF291492 | KF291669 |

| D. glans F. White | BT019 | New Caledonia | KF291809 | KF291868 | KF291927 | KF291349 | ||||

| D. glans | BT093 | New Caledonia | Turner et al. 093 | MPU | KF291810 | KF291869 | KF291928 | KF291350 | KF291493 | KF291670 |

| D. glans | BT094 | New Caledonia | Turner et al. 094 | MPU | KF291811 | KF291870 | KF291929 | KF291351 | KF291494 | KF291671 |

| D. glaucifolia Metcalf | K14256 | China | Chase 14256 | K | DQ923917 | EU980694 | DQ924024 | EU981109 | ||

| D. cf. gracilipes Hiern | RF978 | Madagascar | RNF 978 | W | DQ923918 | EU980695 | DQ924025 | EU981110 | ||

| D. gracilis Fletcher | Eb058 | Thailand | Duangjai 019 | BK, BKF, KUFF, WU | KF291812 | KF291871 | KF291930 | KF291352 | KF291495 | KF291672 |

| D. greenweyi F. White | K21205 | Somalia | Friis et al. 4991 | K | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | KF291353 | ||

| D. grisebachii (Heirn) Standl. | W64 | Cuba | Abbott 18937 | W | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | KF291354 | ||

| D. guianensis (Aubl.) Gürke | W14 | French Guiana | Prévost & Sabatier 4029 | W | DQ923919 | EU980696 | DQ924026 | EU981111 | ||

| D. guianensis | W78 | French Guiana | Mori 25921 | NY, W | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | KF291355 | ||

| D. hartmaniana S. Knapp | K22455 | Panama | McPherson & Richardson 15959 | MO | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | KF291356 | ||

| D. impolita F. White | BT102 | New Caledonia | Schmid 5010 | NOU019538 | KF291813 | KF291872 | KF291931 | KF291357 | KF291496 | KF291673 |

| D. impolita | BT105 | New Caledonia | Schmid 5010 | NOU019538 | KF291814 | KF291873 | KF291932 | KF291358 | KF291497 | KF291674 |

| D. inconstans Jacq. | W79 | Ecuador | Rainer 1682 | W | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | KF291359 | ||

| D. inexplorata F. White | BT304 | New Caledonia | MacKee 22791 | NOU005818 | KF291815 | KF291874 | KF291933 | KF291360 | KF291498 | KF291675 |

| D. inexplorata | BT311 | New Caledonia | MacKee 22791 | NOU005818 | KF291816 | KF291875 | KF291934 | KF291361 | KF291499 | KF291676 |

| D. insidiosa Bakh. | Eb061 | Thailand | Duangjai 120 | KUFF, W | DQ923920 | EU980697 | DQ924027 | EU981112 | ||

| D. iturensis (Gürke) Letouzey & F. White | K21204 | Cameroon | Harris & Fay 1513 | K | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | KF291362 | ||

| D. kaki L.f. | K920 | Japan | Chase 920 | K | DQ923921 | EU980698 | DQ924028 | EU981113 | KF291500 | KF291677 |

| D. kirkii Hiern | K22551 | Zimbabwe | Poilecot 7650 | K | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | KF291363 | ||

| D. kupensis Gosline | AR62 | Cameroon | Russell 62 | K | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | KF291501 | KF291678 | |

| D. labillardierei F. White | BT121 | New Caledonia | Munzinger et al. 6624 | NOU | KF291817 | KF291876 | KF291935 | KF291364 | KF291502 | KF291679 |

| D. labillardierei | BT122 | New Caledonia | Munzinger et al. 6624 | NOU | KF291818 | KF291877 | KF291936 | KF291365 | KF291503 | KF291680 |

| D. labillardierei | BT179 | New Caledonia | KF291504 | KF291681 | ||||||

| D. labillardierei | K20763 | New Caledonia | McPherson & Munzinger 18038 | MO | DQ923922 | EU980699 | DQ924029 | EU981114 | ||

| D. labillardierei | M2219 | New Caledonia | Munzinger 2219 | NOU006657 | EU980828 | EU980700 | EU980951 | EU981115 | KF291505 | KF291682 |

| D. labillardierei | M3053 | New Caledonia | Munzinger 3053 | NOU008407 | EU980829 | EU980701 | EU980952 | EU981116 | KF291506 | KF291683 |

| D. lanceifolia Roxb. | K1245 | Indonesia | Chase 1245 | K | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | KF291366 | ||

| D. leucomelas Poir. | K25752 | Mauritius | Page 16 | MAU | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | KF291367 | ||

| D. lotus L. | D16 | Living coll. HBV | Turner D16 | Living coll. HBV | KF291507 | KF291684 | ||||

| D. lotus | K965 | Living coll. Kew 1882-3501 | Chase 965 | K | DQ923924 | EU980703 | DQ924031 | EU981118 | ||

| D. macrocarpa (Vieill.) Hiern | BT043 | New Caledonia | KF291508 | KF291685 | ||||||

| D. macrocarpa | BT044 | New Caledonia | KF291509 | KF291686 | ||||||

| D. macrocarpa | BT048 | New Caledonia | KF291510 | KF291687 | ||||||

| D. macrocarpa | BT049 | New Caledonia | KF291511 | KF291688 | ||||||

| D. macrocarpa | BT050 | New Caledonia | KF291512 | KF291689 | ||||||

| D. macrocarpa | M2014 | New Caledonia | Munzinger 2014 | NOU003637 | EU980830 | EU980704 | EU980953 | EU981119 | ||

| D. macrocarpa | M2829 | New Caledonia | Munzinger 2829 | NOU008233 | DQ923925 | EU980705 | DQ924032 | EU981120 | ||

| D. maingayi (Hiern) Bakh. | Eb073 | Thailand | Duangjai 131 | KUFF, W | DQ923926 | EU980706 | DQ924033 | EU981121 | ||

| D. malabarica (Desr.) Kostel. | Eb066 | Thailand | Duangjai 006 | KUFF, W | EU980708 | DQ923928 | DQ924035 | EU981123 | ||

| D. malabarica | K1247 | Indonesia | Chase 1247 | K | DQ923927 | EU980707 | DQ924034 | EU981122 | ||

| D. malabarica | W47 | South East Asia, cult. USA | Abbott 14325 | W | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | KF291368 | ||

| D. mannii Hiern | K20597 | Ghana | Merello et al. 1348 | MO | DQ923929 | EU980709 | DQ924036 | EU981124 | ||

| D. margaretae F. White | YP1267 | New Caledonia | Pillon 1267 | NOU049432, WU062863 | KF291819 | KF291878 | KF291937 | KF291369 | KF291513 | KF291690 |

| D. maritima Blume | Eb209 | Malaysia | Wallnöfer 13948 | W | DQ923930 | EU980710 | DQ924037 | EU981125 | ||

| D. melanida Poir. | K25786 | Mauritius | Page 112 | MAU | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | KF291370 | ||

| D. melocarpa F. White | K22457 | Gabon | SIMAB 012319 | MO | DQ923931 | EU980711 | DQ924038 | EU981126 | ||

| D. mespiliformis Hochst. Ex A.DC. | Eb206 | Tropical Africa | Wallnöfer & Duangjai 13945 | W | DQ923932 | EU980712 | DQ924039 | EU981127 | KF291514 | KF291691 |

| D. mespiliformis | W60 | Senegal | Prinz 2005-5 | W | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | KF291371 | ||

| D. minimifolia F. White | BT131 | New Caledonia | Dagostini 203 | NOU019556 | KF291820 | KF291879 | KF291938 | KF291372 | KF291515 | KF291692 |

| D. minimifolia | BT133 | New Caledonia | Dagostini 203 | NOU019556 | KF291821 | KF291880 | KF291939 | KF291373 | KF291516 | KF291693 |

| D. minimifolia | BT231 | New Caledonia | Veillon 7206 | NOU019554 | KF291517 | KF291694 | ||||

| D. minimifolia | BT264 | New Caledonia | Chambrey & Turner 24 | NOU079549, WU062872 | KF291518 | KF291695 | ||||

| D. minimifolia | M2214 | New Caledonia | Munzinger 2214 | NOU006263 | EU980831 | EU980714 | EU980954 | EU981129 | KF291519 | KF291696 |

| D. minimifolia | M2374 | New Caledonia | Munzinger 2374 | NOU006677 | EU980832 | EU980715 | EU980955 | EU981130 | KF291520 | KF291697 |

| D. minimifolia/pustulata | BT143 | New Caledonia | KF291521 | KF291698 | ||||||

| D. mollis Griff. | Eb074 | Thailand | Duangjai 132 | KUFF, W | DQ923934 | EU980716 | DQ924041 | EU981131 | KF291522 | KF291699 |

| D. montana Roxb. | Eb078 | Thailand | Duangjai 136 | KUFF, W | DQ923935 | EU980717 | DQ924042 | EU981132 | ||

| D. montana | Eb130 | Thailand | Duangjai & Sinbumrung 017 | KUFF, W | DQ923943 | EU980733 | DQ924050 | EU981148 | ||

| D. myriophylla (H. Perrier) G.E. Schatz & Lowry | W34 | Madagascar | Sieder 209 | W | DQ923974 | EU980797 | DQ924083 | EU981212 | ||

| D. natalensis (Harv.) Brenan | K22554 | Zambia | Bingham 10635 | K | DQ923936 | EU980718 | DQ924043 | EU981133 | ||

| D. nigra (J.F. Gmel.) Perrier | K212 | Cult. Mexico | Chase 212 | NCU | DQ923906 | EU980676 | DQ924013 | EU981091 | ||

| D. nigra | K1146 | Cult. Mexico | Chase 1146 | K | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | KF291374 | ||

| D. obliquifolia (Hiern ex Gürke) F. White | W91 | Cameroon | Rainer 6.3.2007 | W | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | KF291375 | ||

| D. oblonga Wall. Ex G. Don. | Eb083 | Thailand | Duangjai 141 | KUFF, W | DQ923937 | EU980719 | DQ924044 | EU981134 | ||

| D. olen Hiern | BT001 | New Caledonia | Munzinger et al. 6609 | NOU | KF291822 | KF291881 | KF291940 | KF291376 | KF291523 | KF291700 |

| D. olen | BT032 | New Caledonia | KF291524 | KF291701 | ||||||

| D. olen | BT034 | New Caledonia | KF291525 | KF291702 | ||||||

| D. olen | BT169 | New Caledonia | Munzinger et al. 6634 | NOU | KF291526 | KF291703 | ||||

| D. olen | BT302 | New Caledonia | KF291527 | KF291704 | ||||||

| D. olen | K20598 | New Caledonia | Lowry et al. 5628 | MO, NOU004840 | DQ923938 | EU980720 | DQ924045 | EU981135 | ||

| D. olen | M2827 | New Caledonia | Munzinger 2827 | NOU008235 | EU980833 | EU980721 | EU980956 | EU981136 | ||

| D. olen | YP153 | New Caledonia | Pillon 153 | NOU006438 | EU980834 | EU980722 | EU980957 | EU981137 | ||

| D. oubatchensis Kosterm. | BT160 | New Caledonia | LeCore et al. 768 | NOU079472 | KF291823 | KF291882 | KF291941 | KF291377 | KF291528 | KF291705 |

| D. oubatchensis | BT161 | New Caledonia | LeCore et al. 768 | NOU079472 | KF291824 | KF291883 | KF291942 | KF291378 | KF291529 | KF291706 |

| D. oubatchensis | M3118 | New Caledonia | Munzinger 3118 | NOU009675 | EU980835 | EU980723 | EU980958 | EU981138 | ||

| D. oubatchensis | M3333 | New Caledonia | Munzinger 3333 | NOU011201 | EU980836 | EU980724 | EU980959 | EU981139 | ||

| D. ovalifolia Wight | DY10 | Sri Lanka | Yakandawala 10 | PDA | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | KF291379 | ||

| D. pancheri Kosterm. | BT027 | New Caledonia | Munzinger et al. 6619 | NOU | KF291825 | KF291884 | KF291943 | KF291380 | KF291530 | KF291707 |

| D. pancheri | BT028 | New Caledonia | Munzinger et al. 6619 | NOU | KF291826 | KF291885 | KF291944 | KF291381 | KF291531 | KF291708 |

| D. pancheri | BT029 | New Caledonia | Munzinger et al. 6619 | NOU | KF291532 | KF291709 | ||||

| D. pancheri | BT030 | New Caledonia | Munzinger et al. 6620 | NOU | KF291533 | KF291710 | ||||

| D. pancheri | BT031 | New Caledonia | Munzinger et al. 6620 | NOU | KF291534 | KF291711 | ||||

| D. pancheri | BT033 | New Caledonia | Munzinger et al. 6620 | NOU | KF291827 | KF291886 | KF291945 | KF291382 | KF291535 | KF291712 |

| D. pancheri | BT035 | New Caledonia | Munzinger et al. 6620 | NOU | KF291536 | KF291713 | ||||

| D. pancheri | BT076 | New Caledonia | KF291537 | KF291714 | ||||||

| D. pancheri | M2138 | New Caledonia | Munzinger 2138 | NOU003868 | EU980837 | EU980725 | EU980960 | EU981140 | KF291538 | KF291715 |

| D. pancheri/parviflora | M2338 | New Caledonia | Munzinger 2338 | NOU006586 | EU980838 | EU980726 | EU980961 | EU981141 | KF291539 | KF291716 |

| D. parviflora (Schltr.) Bakh. | BT038 | New Caledonia | KF291828 | KF291887 | KF291946 | KF291383 | ||||

| D. parviflora | BT039 | New Caledonia | KF291829 | KF291888 | KF291947 | KF291384 | KF291540 | KF291717 | ||

| D. parviflora | BT040 | New Caledonia | KF291541 | KF291718 | ||||||

| D. parviflora | BT042 | New Caledonia | KF291542 | KF291719 | ||||||

| D. parviflora | BT187 | New Caledonia | Munzinger et al. 6636 | NOU | KF291543 | KF291720 | ||||

| D. parviflora | M2037 | New Caledonia | Munzinger 2037 | NOU002519 | EU980839 | EU980727 | EU980962 | EU981142 | KF291544 | KF291721 |

| D. parviflora | M2071 | New Caledonia | Munzinger 2071 | NOU002608 | EU980869 | EU980776 | EU980992 | EU981191 | KF291545 | KF291722 |

| D. parviflora | M2708 | New Caledonia | Munzinger 2708 | NOU006658 | EU980728 | EU980840 | EU980963 | EU981143 | ||

| D. parviflora | M3035 | New Caledonia | Munzinger 3035 | NOU008397 | EU980842 | EU980736 | EU980965 | EU981151 | ||

| D. pentamera (Woolls & F. Muell.) F. Muell. | K22549 | Australia | Forster & Booth 25525 | K | DQ923939 | EU980729 | DQ924046 | EU981144 | ||

| D. perplexa F. White | BT004 | New Caledonia | Munzinger et al. 6611 | NOU | KF291830 | KF291889 | KF291948 | KF291385 | KF291546 | KF291723 |

| D. perplexa | BT005 | New Caledonia | Munzinger et al. 6611 | NOU | KF291831 | KF291890 | KF291949 | KF291386 | KF291547 | KF291724 |

| D. perplexa | BT009 | New Caledonia | Munzinger et al. 6611 | NOU | KF291832 | KF291891 | KF291950 | KF291387 | KF291548 | KF291725 |

| D. perplexa | BT147 | New Caledonia | Munzinger et al. 6630 | NOU | KF291549 | KF291726 | ||||

| D. perplexa | BT148 | New Caledonia | Munzinger et al. 6630 | NOU | KF291550 | KF291727 | ||||

| D. perplexa | VH3614 | New Caledonia | Hequet et al. 3614 | NOU016957 | EU980873 | EU980786 | EU980996 | EU981201 | KF291551 | KF291728 |

| D. philippinensis A.DC. | K1248 | Indonesia | Chase 1248 | K | DQ923940 | EU980730 | DQ924047 | EU981145 | ||

| D. philippinensis | W62 | Taiwan | Chung & Anderberg 1400 | HAST | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | KF291388 | ||

| D. pilosanthera Blanco | Eb091 | Thailand | Duangjai 149 | KUFF, W | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | KF291389 | ||

| D. pilosiuscula G. Don | Eb092 | Thailand | Duangjai 150 | KUFF, W | DQ923941 | EU980731 | DQ924048 | EU981146 | ||

| D. preussii Gürke | LPJMO39 | Cameroon | LPJMO39 | YA | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | KF291390 | ||

| D. pruriens Dalzell | W81 | India | DeFranceschi 18.12.2006 | W | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | KF291391 | ||

| D. pseudomespilus Mildbr. | K20606 | Gabon | Walters et al. 956 | MO | DQ923942 | EU980732 | DQ924049 | EU981147 | ||

| D. puncticulosa Bakh. | Eb150 | Brunei | Duangjai et al. 018 | BRUN, W, WU | DQ923944 | EU980734 | DQ924051 | EU981149 | ||

| D. pustulata F. White | BT113 | New Caledonia | KF291833 | KF291892 | KF291951 | KF291392 | KF291552 | KF291729 | ||

| D. pustulata | BT114 | New Caledonia | KF291834 | KF291893 | KF291952 | KF291393 | KF291553 | KF291730 | ||

| D. pustulata | BT136 | New Caledonia | Munzinger et al. 6629 | NOU | KF291554 | KF291731 | ||||

| D. pustulata | BT137 | New Caledonia | Munzinger et al. 6629 | NOU | KF291555 | KF291732 | ||||

| D. pustulata | BT257 | New Caledonia | Cambrey & Turner 21 | NOU079548, WU062871 | KF291556 | KF291733 | ||||

| D. pustulata | M3580 | New Caledonia | Munzinger 3580 | NOU016720 | EU980843 | EU980737 | EU980966 | EU981152 | KF291557 | KF291734 |

| D. pustulata | M3584 | New Caledonia | Munzinger 3584 | NOU016734 | EU980844 | EU980738 | EU980967 | EU981153 | KF291558 | KF291735 |

| D. pustulata | VH3638 | New Caledonia | Hequet et al. 3638 | NOU017016 | KF291559 | KF291736 | ||||

| D. pustulata/yahouensis | BT259 | New Caledonia | Chambrey & Turner 26 | WU062855 | KF291835 | KF291894 | KF291953 | KF291394 | KF291560 | KF291737 |

| D. racemosa Roxb. | Eb106 | Thailand | Duangjai 164 | KUFF | EU980856 | EU980759 | EU980979 | EU981174 | KF291561 | KF291738 |

| D. revaughanii I. Richardson | K25760 | Mauritius | Page 47 | MAU | Duangjai unpubl | Duangjai unpubl | Duangjai unpubl | KF291395 | ||

| D. revolutissima F. White | BT116 | New Caledonia | MacKee 22382 | NOU023189 | KF291836 | KF291895 | KF291954 | KF291396 | KF291562 | KF291739 |

| D. revolutissima | BT117 | New Caledonia | MacKee 22382 | NOU023189 | KF291837 | KF291896 | KF291955 | KF291397 | KF291563 | KF291740 |

| D. revolutissima | BT218 | New Caledonia | Munzinger et al. 6640 | NOU | KF291564 | KF291741 | ||||

| D. revolutissima | BT219 | New Caledonia | Munzinger et al. 6640 | NOU | KF291565 | KF291742 | ||||

| D. revolutissima | YP204 | New Caledonia | Pillon 204 | NOU009155 | EU980846 | EU980740 | EU980969 | EU981155 | KF291566 | KF291743 |

| D. rhodocalyx Kurz | Eb096 | Thailand | Duangjai 154 | KUFF, WU | KF291838 | KF291897 | KF291956 | KF291398 | KF291567 | KF291744 |

| D. rhombifolia Hemsl. | Eb129 | Thailand | Duangjai & Sinbumrung 016 | KUFF, W | DQ923945 | EU980741 | DQ924052 | EU981156 | ||

| D. cf. rhombifolia | W76 | Cult. USA, (South East Asia) | Abbott 20824 | W | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | KF291399 | ||

| D. ridleyi Bakh. | Eb138 | Brunei | Duangjai et al. 002 | BRUN, W, WU | DQ923946 | EU980742 | DQ924053 | EU981157 | KF291568 | KF291745 |

| D. rigida Hiern | Eb140 | Brunei | Duangjai et al. 004 | BRUN, W, WU | DQ923947 | EU980743 | DQ924054 | EU981158 | ||

| D. ropourea B. Walln. | W20 | French Guiana | Wallnöfer 13459 | W | DQ923948 | EU980744 | DQ924055 | EU981159 | ||

| D. salicifolia Humb. & Bonpl. ex Willd. | W66 | Guatemala | Abbott 19765 | W | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | KF291400 | ||

| D. salicifolia | W67 | Guatemala | Abbott 19777 | W | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | KF291401 | ||

| D. samoensis A. Gray | Eb176 | Cult. Hawaii Bot Garden | Kiehn s.n. | WU | EU980745 | EU980847 | EU980970 | EU981160 | ||

| D. samoensis | M3593 | Vanuatu | Munzinger 3593 | NOU080070 | EU980848 | EU980746 | EU980971 | EU981161 | ||

| D. samoensis | M3624 | Vanuatu | Munzinger 3624 | NOU080138, NOU080139 | EU980849 | EU980747 | EU980972 | EU981162 | KF291569 | KF291746 |

| D. samoensis | M3691 | Vanuatu | Munzinger 3691 | NOU | EU980850 | EU980748 | EU980973 | EU981163 | ||

| D. sandwicensis (A.DC.) Fosberg | Eb175 | Cult. Hawaii Bot Garden | Kiehn s.n. | WU | EU980851 | EU980749 | EU980974 | EU981164 | KF291570 | KF291747 |

| D. scabra (Chiov.) Cufod. | K21206 | Ethiopia | Wondefrash & Tefera 9622 | K | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | KF291402 | ||

| D. scalariformis Fletcher | Eb172 | Thailand | Duangjai & Sinbumrung s.n. | KUFF, W | EU980750 | EU980852 | EU980975 | EU981165 | ||

| D. senensis Klotzsch | K22552 | Zambia | Bingham 11092 | K | EU980853 | EU980751 | EU980976 | EU981166 | ||

| D. squarrosa Klotzsch | K21207 | Somalia | Friis et al. 4894 | K | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | KF291417 | ||

| D. squarrosa | K22555 | Zambia | Bingham & Downie 11465 | K | EU980854 | EU980752 | EU980977 | EU981167 | ||

| D. styraciformis King & Gamble | Eb149 | Brunei | Duangjai et al. 017 | BRUN, W, WU | DQ923949 | EU980753 | DQ924056 | EU981168 | ||

| D. sumatrana Miq. | Eb099 | Thailand | Duangjai 157 | KUFF, W | EU980855 | EU980754 | EU980978 | EU981169 | ||

| D. tenuiflora A.C.Sm. | W32 | Brazil | Maas et al. 9186 | NY, W | DQ923923 | EU980702 | DQ924030 | EU981117 | ||

| D. tesselaria Poir. | K25751 | Mauritius | Page 15 | MAU | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | KF291418 | ||

| D. tetrandra Hiern | W31 | French Guiana | Prévost & Sabatier 4713 | W | DQ923951 | EU980756 | DQ924058 | EU981171 | ||

| D. tetrasperma Sw. | K14254 | Mexico | Chase 14254 | K, W | DQ923952 | EU980757 | DQ924059 | EU981172 | ||

| D. texana Scheele | Eb208 | Middle America | Wallnöfer & Duangjai 13946 | W | DQ923953 | EU980758 | DQ924060 | EU981173 | KF291575 | KF291752 |

| D. tireliae F. White | M5725 | New Caledonia | Munzinger 5725 | NOU051026 | KF291843 | KF291902 | KF291961 | KF291419 | KF291576 | KF291753 |

| D. tridentata F. White | BT202 | New Caledonia | Munzinger et al. 6639 | NOU | KF291844 | KF291903 | KF291962 | KF291420 | KF291577 | KF291754 |

| D. tridentata | BT203 | New Caledonia | Munzinger et al. 6639 | NOU | KF291845 | KF291904 | KF291963 | KF291421 | KF291578 | KF291755 |

| D. trisulca F. White | BT185 | New Caledonia | Hequet (leg. Butin) 3820 | NOU031344 | KF291846 | KF291905 | KF291964 | KF291422 | KF291579 | KF291756 |

| D. trisulca | BT189 | New Caledonia | Hequet (leg. Butin) 3820 | NOU031344 | KF291847 | KF291906 | KF291965 | KF291423 | KF291580 | KF291757 |

| D. trisulca | BT192 | New Caledonia | Hequet (leg. Butin) 3820 | NOU031344 | KF291848 | KF291907 | KF291966 | KF291424 | KF291581 | KF291758 |

| D. trisulca | BT197 | New Caledonia | Munzinger et al. 6637 | NOU | KF291582 | KF291759 | ||||

| D. trisulca | M3179 | New Caledonia | Munzinger 3179 | NOU016896 | EU980871 | EU980784 | EU980994 | EU981199 | ||

| D. trisulca | M3260 | New Caledonia | Munzinger 3260 | NOU016891, WU062868 | EU980872 | EU980785 | EU980995 | EU981200 | KF291583 | KF291760 |

| D. cf. ulo Merr. | Eb152 | Brunei | Duangjai et al. 021 | BRUN, W, WU | EU980857 | EU980760 | EU980980 | EU981175 | KF291462 | KF291639 |

| D. umbrosa F. White | BT065 | New Caledonia | KF291849 | KF291908 | KF291967 | KF291425 | KF291584 | KF291761 | ||

| D. umbrosa | BT066 | New Caledonia | KF291585 | KF291762 | ||||||

| D. umbrosa | BT071 | New Caledonia | KF291586 | KF291763 | ||||||

| D. umbrosa | BT246 | New Caledonia | McPherson 2144 | NOU023234 | KF291850 | KF291909 | KF291968 | KF291426 | KF291587 | KF291764 |

| D. umbrosa | BT247 | New Caledonia | McPherson 2144 | NOU023234 | KF291851 | KF291910 | KF291969 | KF291427 | KF291588 | KF291765 |

| D. umbrosa | BT256 | New Caledonia | McPherson 2144 | NOU023234 | KF291589 | KF291766 | ||||

| D. umbrosa | M2265 | New Caledonia | Munzinger 2265 | NOU006679 | EU980858 | EU980761 | EU980981 | EU981176 | KF291590 | KF291767 |

| D. umbrosa | M2636 | New Caledonia | Munzinger 2636 | NOU006678 | EU980859 | EU980762 | EU980982 | EU981177 | KF291591 | KF291768 |

| D. umbrosa | M2771 | New Caledonia | Munzinger 2771 | NOU007912 | EU980860 | EU980763 | EU980983 | EU981178 | KF291592 | KF291769 |

| D. undulata Wall. Ex G. Don | Eb112 | Thailand | Duangjai 170 | KUFF, W | DQ923954 | EU980764 | DQ924061 | EU981179 | ||

| D. veillonii F. White | BT224 | New Caledonia | Veillon 7919 | NOU019582 | KF291852 | KF291911 | KF291970 | KF291428 | KF291593 | KF291770 |

| D. veillonii | BT229 | New Caledonia | Veillon 7919 | NOU019582 | KF291853 | KF291912 | KF291971 | KF291429 | KF291594 | KF291771 |

| D. veillonii | M.sn. | New Caledonia | Munzinger s.n. | Living coll. Hortus Veillonii | EU980861 | EU980765 | EU980984 | EU981180 | KF291595 | KF291772 |

| D. venosa Wall ex A.DC | Eb119 | Thailand | Duangjai 177 | KUFF, W | DQ923955 | EU980767 | DQ924062 | EU981182 | KF291596 | KF291773 |

| D. venosa | Eb131 | Thailand | Duangjai 059 | KUFF, W | EU980862 | EU980766 | EU980985 | EU981181 | ||

| D. vera (Lour.) A. Chev. | DY16 | Sri Lanka | Yakandawala 16 | PDA | EU980823 | EU980682 | EU980946 | EU981097 | ||

| D. vera | Eb045 | Thailand | Duangjai 106 | KUFF | DQ923910 | EU980683 | DQ924017 | EU981098 | KF291597 | KF291774 |

| D. vera | K21193 | Central African Republic | Harris & Fay 2032 | K | EU980824 | EU980684 | EU980947 | EU981099 | ||

| D. vestita Benoist | W01 | French Guiana | Molino 1849 | W | DQ923956 | EU980768 | DQ924063 | EU981183 | ||

| D. vieillardii (Hiern) Kosterm. | BT025 | New Caledonia | Munzinger et al. 6618 | NOU | KF291854 | KF291913 | KF291972 | KF291430 | KF291598 | KF291775 |

| D. vieillardii | BT026 | New Caledonia | Munzinger et al. 6618 | NOU | KF291855 | KF291914 | KF291973 | KF291431 | KF291599 | KF291776 |

| D. vieillardii | BT055 | New Caledonia | KF291600 | KF291777 | ||||||

| D. vieillardii | BT057 | New Caledonia | KF291601 | KF291778 | ||||||

| D. vieillardii | BT099 | New Caledonia | KF291602 | KF291779 | ||||||

| D. vieillardii | BT100 | New Caledonia | KF291603 | KF291780 | ||||||

| D. vieillardii | BT213 | New Caledonia | MacKee 25141 | NOU023242 | KF291604 | KF291781 | ||||

| D. vieillardii | BT214 | New Caledonia | MacKee 25141 | NOU023242 | KF291605 | KF291782 | ||||

| D. vieillardii | BT286 | New Caledonia | Chambrey & Turner 13 | NOU054004, WU062859 | KF291606 | KF291783 | ||||

| D. vieillardii | BT325 | New Caledonia | Munzinger et al. 6657 | NOU, P | KF291607 | KF291784 | ||||

| D. vieillardii | M2106 | New Caledonia | Munzinger 2106 | NOU006676 | EU980863 | EU980769 | EU980986 | EU981184 | KF291608 | KF291785 |

| D. vieillardii | M2776 | New Caledonia | Munzinger 2776 | NOU008207 | EU980864 | EU980770 | EU980987 | EU981185 | ||

| D. vieillardii | M3476 | New Caledonia | Munzinger 3476 | NOU012947 | KF291609 | KF291786 | ||||

| D. vieillardii | M3572 | New Caledonia | Munzinger 3572 | NOU016733 | EU980866 | EU980772 | EU980989 | EU981187 | KF291610 | KF291787 |

| D. vieillardii | YP146 | New Caledonia | Pillon 146 | NOU006400 | EU980867 | EU980773 | EU980990 | EU981052 | KF291611 | KF291788 |

| D. virginiana L. | K14255 | USA | Chase 14255 | K | DQ923957 | EU980774 | DQ924064 | EU981189 | KF291612 | KF291789 |

| D. wallichii King & Gamble ex King | Eb122 | Thailand | Duangjai 180 | KUFF, W | EU980868 | EU980775 | EU980991 | EU981190 | KF291613 | KF291790 |

| D. wallichii | Eb165 | Brunei | Duangjai et al. 41 | BRUN, W, WU | KF291614 | KF291791 | ||||

| D. winitii Fletcher | Eb123 | Thailand | Duangjai 181 | KUFF, WU | KF291615 | KF291792 | ||||

| D. yahouensis (Schltr.) Kosterm. | BT237 | New Caledonia | Schlechter 15059 | P00057340 | KF291856 | KF291915 | KF291974 | KF291432 | KF291616 | KF291793 |

| D. yahouensis | BT238 | New Caledonia | Schlechter 15059 | P00057340 | KF291857 | KF291916 | KF291975 | KF291433 | KF291617 | KF291794 |

| D. yahouensis | BT239 | New Caledonia | Schlechter 15059 | P00057340 | KF291618 | KF291795 | ||||

| D. yahouensis | VH3637 | New Caledonia | Hequet et al. 3637 | NOU017017 | KF291858 | KF291917 | KF291976 | KF291434 | KF291619 | KF291796 |

| D. yatesiana Standl. | W27 | Guatemala | Frisch s.n. | W | DQ923958 | EU980777 | DQ924065 | EU981192 | ||

| D. sp. Pic N’ga | BT318 | New Caledonia | Munzinger 6065 | NOU | KF291839 | KF291898 | KF291957 | KF291404 | KF291572 | KF291749 |

| D. sp. Pic N’ga | BT319 | New Caledonia | Munzinger 6065 | NOU | KF291840 | KF291899 | KF291958 | KF291405 | KF291573 | KF291750 |

| D. sp. Pic N’ga | BT320 | New Caledonia | Munzinger 6065 | NOU | KF291841 | KF291900 | KF291959 | KF291406 | KF291574 | KF291751 |

| D. sp. | FS1637 | Madagascar | Fischer & Sieder 1637 | W | DQ923959 | EU980778 | DQ924066 | EU981193 | ||

| D. sp. | FS2217 | Madagascar | Fischer & Sieder 2217 | W | DQ923960 | EU980779 | DQ924067 | EU981194 | ||

| D. sp. | K20600 | Madagascar | Rabenantoandro et al. 1246 | MO | DQ923961 | EU980780 | DQ924068 | EU981195 | ||

| D. sp. | K20601 | Madagascar | Rabevohitra et al. 3660 | MO | DQ923973 | EU980796 | DQ924082 | EU981211 | ||

| D. sp. | K20613 | Zambia | Zimba et al. 893 | MO | DQ923962 | EU980781 | DQ924069 | EU981196 | ||

| D. sp. | K20616 | Ghana | Schmidt et al. 2207 | MO | DQ923963 | EU980783 | DQ924070 | EU981198 | ||

| D. sp. | K25759 | Mauritius | Page 46 | MAU | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | KF291403 | ||

| D. sp. | RF958 | Madagascar | RNF 958 | W | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | KF291407 | ||

| D. sp. | RF959 | Madagascar | RNF 959 | W | DQ923980 | EU980804 | DQ924089 | EU981219 | ||

| D. sp. | RF970 | Madagascar | RNF 970 | W | DQ923964 | EU980787 | DQ924071 | EU981202 | ||

| D. sp. | S10 | Sri Lanka | Samuel 10 | PDA | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | KF291408 | ||

| D. sp. | S12 | Sri Lanka | Samuel 12 | PDA | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | KF291409 | ||

| D. sp. | S18 | Sri Lanka | Samuel 18 | PDA | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | KF291410 | ||

| D. sp. | S22 | Sri Lanka | Samuel 22 | PDA | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | KF291411 | ||

| D. sp. | S25 | Sri Lanka | Samuel 25 | PDA | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | KF291412 | ||

| D. sp. | S26 | Sri Lanka | Samuel 26 | PDA | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | KF291413 | ||

| D. sp. | S28 | Sri Lanka | Samuel 28 | PDA | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | KF291414 | ||

| D. sp. | W33 | Madagascar | Sieder 440 | W | KF291842 | KF291901 | KF291960 | KF291415 | KF291571 | KF291748 |

| D. sp. | W36 | Madagascar | Sieder et al. 258 | W | DQ923965 | EU980788 | DQ924072 | EU981203 | ||

| D. sp. | W77 | Madagascar | Sieder et al. 3079 | W | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | KF291416 | ||

| Euclea crispa (Thunb.) Gürke | Eb202 | Living coll. HBV (EB 4/2) | Wallnöfer 13949 | W | DQ923966 | EU980789 | DQ924073 | EU981204 | ||

| Euclea crispa | K21188 | Malawi | Chapman & Chapman 8085 | K | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | KF291435 | ||

| Euclea divinorum Hiern | Eb201 | Cult. HBV (EB 2/1, Salisburg 69) | Wallnöfer & Duangjai 13947 | W | DQ923967 | EU980790 | DQ924074 | EU981205 | ||

| Euclea natalensis A.DC. | K21186 | Zimbabwe | Timberlake & Cunliffe 4389 | K | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | KF291436 | ||

| Euclea natalensis | W08 | South Africa | Kurzweil E514 | W | DQ923968 | EU980791 | DQ924075 | EU981206 | ||

| Euclea pseudobenus E. Mey. ex A.DC | K21190 | Namibia | Ward 9205 | K | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | KF291437 | ||

| Euclea racemosa L. | K21183 | Somalia | Thulin 10739 | K | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | KF291438 | ||

| Euclea sp. | W58 | Tanzania | Kutalek 1-2001 | W | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | KF291439 | ||

| Euclea sp. | W59 | Tanzania | Mbeyela 2-2001 | W | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | KF291440 | ||

| Euclea undulata Thunb. | Eb200 | Cult. HBV (EB 5/2, 1973) | Wallnöfer 13897 | W | EU980874 | EU980792 | DQ924076 | EU981207 | KF291620 | KF291797 |

| Royena cordata E. Mey ex A.DC | K1144 | South Africa | Chase 1144 | K | DQ923975 | EU980799 | DQ924084 | EU981214 | ||

| Royena glabra L. | W05 | South Africa | Kurzweil 2097 | W | DQ923976 | EU980800 | DQ924085 | EU981215 | ||

| Royena lucida L. | Eb203 | South Africa | Wallnöfer & Duangjai 13943 | W | DQ923977 | EU980801 | DQ924086 | EU981216 | ||

| Royena lucida | W06 | South Africa | Kurzweil E513 | W | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | KF291442 | ||

| Royena lycioides Desf. Ex A.DC | K977 | South Africa | Chase 977 | K | DQ923978 | EU980802 | DQ924087 | EU981217 | ||

| Royena sp. | K1145 | South Africa | Chase 1145 | K | KF291859 | KF291918 | KF291977 | KF291444 | ||

| Royena whyteana Hiern | Eb177 | Africa | Kiehn s.n. | WU | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | KF291443 | KF291622 | KF291799 |

| Royena zombensis B.L. Burtt | K22558 | Tanzania | Abdallah & Vollesen 95/106 | K | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | Duangjai unpubl. | KF291445 | ||

| Lissocarpa benthamii Gürke | W61 | Venezuela | Berry et al. 7217 | PORT | DQ923969 | EU980793 | DQ924077 | EU981208 | ||

| Lissocarpa guianensis Gleason | W04 | Guyana | Arets s.n. | U | DQ923970 | EU980794 | DQ924078 | EU981209 | ||

| Lissocarpa stenocarpa Steyerm. | K20609 | Peru | Vásquez & Ortiz-Gentry 25233 | MO | DQ923971 | EU980795 | DQ924079 | EU981210 | ||

| Argania spinosa (L.) Skeels | K978 | Morocco | Chase 978 | K | DQ923981 | EU980805 | DQ924090 | KF291308 | ||

| Cleyera japonica Thunb. | K1690 | Japan | Chase 1690 | K | DQ923985 | EU980811 | DQ924094 | KF291309 | ||

| Halesia carolina L. | K910 | USA | Chase 910 | K | KF291621 | KF291798 | ||||

| Madhuca macrophylla (Hassk.) H.J. Lam | K1363 | Cult. Indonesia | Chase 1363 | K | DQ923982 | EU980806 | DQ924091 | KF291441 | ||

| Styrax benzoin Dryand. | K1371 | Indonesia | Chase 1371 | K | DQ923989 | EU980809 | DQ924098 | KF291446 | ||

| Styrax officinalis L. | K872 | Living coll. RGB Kew 1973-14474 | Chase 872 | K | KF291623 | KF291800 |

2.2. DNA extraction

For DNA extraction the sorbitol/high-salt CTAB method (Tel-Zur et al., 1999), modified for 2 ml micro-centrifuge tubes, was used. Tubes containing silica gel-dried material were frozen with liquid nitrogen (to keep material frozen during grinding to avoid enzymatic action) and then ground with glass-beads to a fine powder. Prior to extraction, ground material was washed three times with sorbitol buffer.

2.3. PCR and cycle sequencing

We sequenced four plastid regions: atpB, rbcL, trnK–matK (partial trnK intron and complete matK gene) and trnS–trnG, which collectively represent approximately 6.5 kb. Primers and PCR conditions are those of Duangjai et al. (2009). We added 136 accessions to the matrix of Duangjai et al. (2009).

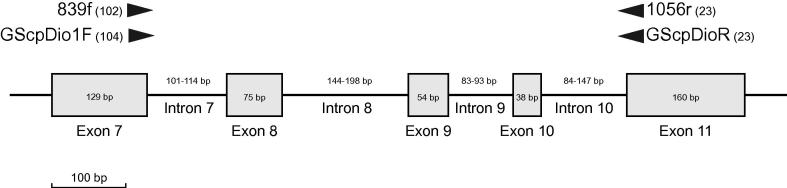

Chloroplast-expressed glutamine synthetase (ncpGS) was amplified with primers designed for this study (GScpDio1F and GScpDioR; Table 4). Initial Diospyros sequences for primer design were obtained with the primers and PCR protocol of Yockteng and Nadot (2004). Primers were situated at the end of exon 7 (forward) and beginning of exon 11 (reverse), amplifying a fragment between 700 and 715 bp (Fig. 2). Primers used for PCR were also used for cycle sequencing (Tables 2 and 3).

Table 4.

Primers used in this study.

| Primer name | Fragment | Sequence (5’-3’) | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| GScp839F | ncpGS | CACCAATGGGGAGGTTATGC | Yockteng and Nadot (2004) |

| GScp1056R | ncpGS | CATCTTCCCTCATGCTCTTTGT | Yockteng and Nadot (2004) |

| GscpDio1F | ncpGS | CCAATGGGGAGGTTATGCCTGGACAG | This study |

| GScpDioR | ncpGS | CATCTTCCCTCATGCTCTTTGTACTG | This study |

| PHYA upstream | phyA | GACTTTGARCCNGTBAAGCCTTAYG | Mathews and Donoghue (1999) |

| PHYA downstream | phyA | GDATDGCRTCCATYTCRTAGTC | Mathews and Donoghue (1999) |

| PhyADioF | phyA | GTBAAGCCTTAYGAAGTCCCGATGA | This study |

| PhyADioFi | phyA | GTCAAYGAGGGGGATGRAGAGGGAG | This study |

| PhyADioR | phyA | GCRTCCATYTCRTAGTCCTTCCAAG | This study |

| PhyADioRi | phyA | CTGATTYTCCAAYTCTAACTCCTTGTTGAC | This study |

Fig. 2.

Schematic diagram of exon 7–exon 11 of ncpGS with primer positions and length of exons and introns. Numbers in parentheses give 5′ end of primers.

Table 2.

PCR reactions.

| ncpGS | 1st phyA | 2nd phyA | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18 μl | 1.1xReddyMix (Thermo Scientific) | 18 μl | 1.1xReddyMix (Thermo Scientific) | 18 μl | 1.1xReddyMix (Thermo Scientific) |

| 0.4 μl | Primer GScpDio1F (20 pM) | 0.4 μl | Primer PHYA upstream (20 pM) | 0.4 μl | Primer PhyADioF (20 pM) |

| 0.4 μl | Primer GScpDioR (20 pM) | 0.4 μl | Primer PHYA down-stream (20 pM) | 0.4 μl | Primer PhyADioR (20 pM) |

| 0.7 μl | Water | 0.7 μl | Water | 0.3 μl | Water |

| 0.4 μl | BSA (20 mg/ml) | ||||

| 0.5 μl | DNA | 0.5 μl | DNA | 0.5 μl | PCR product |

BSA: bovine albumin serum (Thermo Scientific).

Table 3.

PCR conditions.

| ncpGS | 1st phyA | 2nd phyA | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 95 °C for 2 min | 95 °C for 2 min | 95 °C for 2 min | |||

| 95 °C for 30 s | 95 °C for 30 s | 95 °C for 30 s | |||

| 58 °C for 30 s | 35 cycles | 52 °C for 30 s | 35 cycles | 60 °C for 30 s | 35 cycles |

| 72 °C for 2 min | 70 °C for 2 min | 72 °C for 1.5 min | |||

| 72 °C for 7 min | 70 °C for 7 min | 72 °C for 7 min | |||

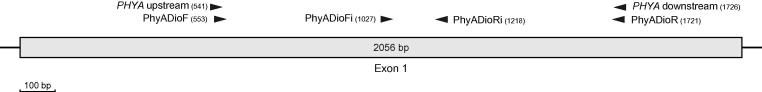

Initial PCR products and sequences of PHYA were obtained with the locus-specific primers of Mathews and Donoghue (1999; PHYA upstream [2nd] and PHYA downstream [1st]). As these primers were not specific enough, we cloned the PCR products (see Section 2.4) to be able to design Diospyros-specific PHYA PCR and sequencing primers (PhyADioF, PhyADioR, PhyADioFi and PhyADioRi; Table 4; Fig. 3). However, as the new PCR primers designed for Diospyros did not amplify consistently, we used a two-step amplification protocol. In the first PCR, the universal PHYA primers were used, and then a second nested PCR was performed with the newly designed primers and the product from the first PCR as template. All primers are located in exon 1 of PHYA flanking a region of 1187 bp in length. PCR conditions and composition are provided in Tables 2 and 3. For cycle-sequencing, we used the two internal primers and the external reverse primer.

Fig. 3.

Schematic diagram of exon 1 of phyA with primer positions and length of exon. Numbers in parentheses give 5′ end of primers.

PCR products were cleaned with a mixture of exonuclease I and alkaline phosphatase (10 units exo I and one unit FastAP, both from Thermo Scientific) and incubated at 37 °C for 45 min followed by 15 min at 80 °C to inactivate enzymes. Cycle sequencing reactions were performed with 0.8 μl BigDye Terminator v3.1 (AB, Live Technologies), 1.0 μl primer (3.2 μM), 1.6 μl 5× sequencing buffer and 6.6 μl cleaned-up PCR product using 35 cycles of 96 °C for 10 s, 50 °C for 5 s and 60 °C for 3 min. Sequences were produced on a capillary sequencer (3730 DNA Analyzer, AB, Life Technologies) following the manufacturer’s protocols.

2.4. Cloning

Cloning was needed to produce PHYA from some accessions; these where than used for development of more specific primers. In addition, cloning of samples was necessary when we failed to obtain good sequences with the Diospyros-specific primers. PCR products were obtained using the universal PHYA primers, and after gel purification (Inivsorb Spin DNA Extraction Kit, Invitek), cleaned products were cloned using the pGEM-T Easy cloning system (Promega), following the manufacturer’s protocol. Cloned fragments were amplified using M13-f47 and M13-r48 primers and the following PCR conditions: initial denaturation 94 °C for 3 min, 35 cycles of denaturation 94 °C for 30 s, annealing 62 °C for 30 s and extension 72 °C for 2 min followed by a final extension at 72 °C for 7 min.

2.5. Sequence assembly, and editing, and phylogenetic analyses

Assembly and editing of sequences was done with the SeqMan Pro of the Lasergene v8.1 software package (DNASTAR); alignment was conducted with MUSCLE v3.8 (Edgar, 2004) and inspected visually using BioEdit v7.0.4 (Hall, 1999). Discrimination between the two copies of PHYA that were recovered from some species was done based on the alignment, and the ‘wrong’ (highly divergent) copy was excluded from further analyses. To test congruence between the data sets, ILD (incongruence length difference) test (Farris et al., 1994) implemented in PAUP∗ v4b10 (Swofford, 2003; termed the “partition homogeny test”) was carried out with 100 replicates. To speed up this analysis, the neo-endemic clade (where resolution is low due to lack of variability and therefore congruence is unlikely to be detected) was reduced to two accessions (D. sp. Pic N’ga BT318 and D. vieillardii BT025). Results of the ILD test indicated congruence of the four plastid data sets, and therefore the plastid data sets were combined; jModeltest indicated the same model could be used in all analyses without partitioning. Phylogenetic analyses were performed using PAUP∗ v4b10 (Swofford, 2003) for maximum parsimony (MP) and RaxML (Stamatakis, 2006) for maximum likelihood (ML) analyses. For both methods, bootstrap with 1000 replicates was performed to estimate clade support. For Bayesian inference, the program BEAST v1.7.4 (Drummond et al., 2012) was used. Parsimony and Bayesian analyses were run on the Bioportal computer cluster of the University Oslo (www.bioportal.uio.no), and likelihood analyses were run on CIPRS Science Gateway (http://www.phylo.org/portal2/; Miller et al., 2010). Estimation of evolutionary models and values was conducted with jModeltest v2.0.1 (Darriba et al., 2012; Guindon and Gascuel, 2003). For the Bayesian analyses the general time reversible nucleotide substitution model (GTR; Tavaré, 1986) with among site rate variation modelled with a gamma distribution (GTR + Γ) was used for ncpGS, whereas for plastid data the same model was used but with a proportion of invariable sites (GTR + Γ + I). For PHYA the Hasegawa–Kishino–Yano nucleotide substitution model (HKY; Hasegawa et al., 1985) was used with among site rate variation modelled with a gamma distribution and a proportion of invariable sites (HKY + Γ + I). Base frequencies (uniform), substitution rates between bases (gamma shape 10), alpha (gamma shape 10), kappa (gamma shape 10) and p-inv (uniform) were inferred by Modeltest from each data set. We used a relaxed uncorrelated log-normal clock model (Drummond et al., 2006). As speciation model, we used a Yule model (Gernhard, 2008; Yule, 1925). For further details see Supplementary material S1. Two independent Metropolis-coupled Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) analyses each with 20 million generations were run sampling each 1000th generation. The initial 10% of trees obtained from each MCMC run were removed as burn in; the remaining trees of both runs were used to calculate a maximum clade credibility tree.

2.6. Dating the tree

To obtain an overarching dated tree, we used parts (atpB and rbcL sequences of Cornales and Ericales) of the data set of Bell et al. (2010) and combined it with our matrix. This matrix consisted of two plastid markers (atpB and rbcL), which were analysed as two partitions. Dating analyses were run in BEAST with an uncorrelated log-normal relaxed clock under the GTR + Γ + I model. The tree was calibrated with two fossils, Paleoenkianthus sayrevillensis (90 myr; Nixon and Crepet, 1993) as minimum age for Ericales and A. cryptostoma (34 myr; Basinger and Christophel, 1985) as minimum age for Diospyros clade II. Both groups (Ericales and Diospyros calde II) were defined as monophyletic, including the stem. Following tmrca (time of most recent common ancestor) settings used were: log normal prior distribution with a mean of 1.5, log standard deviation of 0.5 and an offset of 89 (Ericales) and 33 (Diospyros clade II). Priors for the molecular clock were: ucld.stdev: log normal, mean 0.9, log stdev 1, initial value 0.5, mean in real space; ucld.mean: CTMC rate reference (Ferreira and Suchard, 2008, initial value 1. Details of settings for BEAST analysis are provided in Section 2.5 (above) and Supplementary material S2. In addition to the plastid marker dating, we also conducted an analysis with our combined data set. We used the same settings as for the Bayesian analysis, but we added two calibration points: A. cryptostoma at 34 myr (Basinger and Christophel, 1985) as minimum age for Diospyros clade II and the split of Diospyros and its sister clade, Euclea plus Royena, 42 myr, which is the minimum age of that node based on dating exercises with the plastid markers. All settings for the molecular clock were the same as those for the plastid data set. The input file used for dating the combined analysis is provided in Supplementary material S3.

2.7. Chromosome counts of Diospyros

Chromosome preparations were made using Feulgen staining following the protocol from Weiss-Schneeweiss et al. (2009). Root tips were collected from plant material growing in the Botanical Garden of the University of Vienna (HBV) and a private garden in New Caledonia. To arrest mitotic spindles, root tips were treated with 0.002 M 8-hydroxquinoline for 2 h at room temperature and 2 h at 4 °C (always in darkness because 8-hydroxquinoline is light sensitive). Pre-treated material was fixed for 12 h at room temperature in 3:1 ethanol:acetic acid and then stored at −20 °C until examined. Fixed root tips were washed in distilled water to remove fixative, hydrolysed in 5 N HCl for 30 min, washed again with distilled water and stained with Schiff’s reagent for approximately 2 h in the dark. Squash preparations were made under a coverslip in a drop of 45% acetic acid. Counts could only be made for few species because obtaining young, actively growing root-tips from New Caledonian Diospyros is difficult. Collecting root-tips from forest trees and shrubs is not possible because there are too many roots in the soil to determine which is from the plant of interest. An alternative method is to grow seedlings in the lab/greenhouse. Obtaining seeds from tropical plants is not easy because these species do not produce fruit at a specific time of the year and flowering is diffuse (only few flowers produced at a time), so one would have to visit the plants regularly for at least 1 year to collect seed material. The logistics of this in process in New Caledonia were difficult. In addition, we found germination of seeds and maintenance of Diospyros seedlings highly problematic. Fortunately, the material we were able to obtain is well distributed among the genome sizes obtained, so we can conclude more than would otherwise be possible.

2.8. Genome size estimations of Diospyros

Genome size was determined using flow cytometry performed on leaf material. Fresh tissue was used from plants growing in the HBV. In addition, recently collected silica-gel dried material from New Caledonia was used for several measurements because it was not possible to transport fresh leaf material from New Caledonia to the laboratory. Samples were chopped in Otto I buffer (Otto et al., 1981) together with leaves of the internal standard species, Solanum pseudocapsicum, 1C = 1.30 pg (Temsch et al., 2010) or Pisum sativum ´Kleine Rheinländeriń, 1C = 4.42 pg (Greilhuber and Ebert, 1994), according to the method of Galbraith et al. (1983). The isolate was filtered through a 30 μm nylon mesh, and RNA was digested with 15 mg/l RNase A for 30 min at 37 °C. Subsequently, DNA was stained in propidium iodide (50 mg/l) supplemented with Otto II buffer (Otto et al., 1981). Mean fluorescence intensity of a total of 15,000 particles was measured with a CyFlow cytometer (Partec, Münster, Germany) equipped with a green laser (Cobolt Samba, Cobolt AB, Stockholm, Sweden); the 1C-value was calculated according to the formula: (MFIobject/MFIStandard) × 1C-valueStandard, where MFI is the mean fluorescence intensity of the G1 nuclei population. Statistical significance of asymmetry between the results obtained from Diospyros species belonging to clade III and those from clades VII–XI was tested using SPSS 15.0 (SPSS, Chicago; IL, USA) and the non-parametric Mann–Whitney U-test because of non-homogeneity of variances between the two groups of variables (Levene’s test for equality of variances, p < 0.05).

3. Results

The data characteristics and statistics from the maximum parsimony analyses of all three individual and the combined data sets are provided in Table 5. Since the focus of this paper is the New Caledonian Diospyros species from clade III, only results pertaining to this group will be discussed in detail. The other species have been included to (i) investigate the utility of these markers for resolving phylogenetic relationships within Diospyros and (ii) further evaluate the hypothesis (proposed by Duangjai et al., 2009) that not all New Caledonian Diospyros resulted from a single colonisation event.

Table 5.

Data characteristics and statistics from the maximum parsimony analyses of all three individual and the combined data sets.

| Combined plastid markers | ncpGS | phyA | Combined data set | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total no. of accessions | 294 | 177 | 177 | 129 |

| No. of outgroup accessions other than Ebenaceae | 4 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| No. of outgroup accessions from Ebenaceae | 21 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| No. of Diospyros accessions | 269 | 173 | 173 | 126 |

| No. of Diospyros species | 149 | 64 | 64 | 64 |

| No. of New Caledonian accessions | 98 | 134 | 134 | 86 |

| No. of New Caledonian species | 28 | 28 | 28 | 28 |

| No. of New Caledonian neoendemic accessions | 83 | 112 | 112 | 74 |

| No. of New Caledonian neoendemic species | 21 | 21 | 21 | 21 |

| Length of alignment | 6556 | 1039 | 1187 | 8542 |

| No. of variable characters | 1880 | 532 | 374 | 1845 |

| No. of parsimony informative characters | 1126 (17.2%) | 341 (32.8%) | 223 (18.8%) | 863 (10%) |

| No. of parsimony informative characters NCnc | 44 (0.7%) | 28 (2.7%) | 14 (1.2%) | 79 (0.9%) |

| Tree length of best parsimony tree (steps) | 3808 | 1171 | 689 | 3259 |

| Trees saved (parsimony analysis) | 210 | 4810 | 1870 | 930 |

| Consistency index | 0.603 | 0.663 | 0.685 | 0.692 |

| Retention index | 0.857 | 0.857 | 0.893 | 0.848 |

| Best fitting model | GTR + Γ + I | GTR + Γ | HKY + Γ + I |

3.1. Plastid markers