Abstract

Objective

We surveyed customers in a hospital cafeteria in Boston, Massachusetts before and after implementation of traffic light food labeling to determine the effect of labels on customers’ awareness and purchase of healthy foods.

Methods

Cafeteria items were identified as red (unhealthy), yellow (less healthy), or green (healthy). Customers were interviewed before (N = 166) and after (N = 223) labeling was implemented. Each respondent was linked to cash register data to determine the proportion of red, yellow, and green items purchased. Data were collected from February–April 2010. We compared responses to survey questions and mean proportion of red, yellow, and green items per transaction between customers interviewed during baseline and customers interviewed during the intervention. Survey response rate was 60%.

Results

Comparing responses during labeling intervention to baseline, more respondents identified health/ nutrition as an important factor in their purchase (61% vs. 46%, p = 0.004) and reported looking at nutrition information (33% vs. 15%, p < 0.001). Respondents who noticed labels during the intervention and reported that labels influenced their purchases were more likely to purchase healthier items than respondents who did not notice labels (p < 0.001 for both).

Conclusion

Traffic light food labels prompted individuals to consider their health and to make healthier choices at point-of-purchase.

Keywords: Nutrition labeling, Obesity, Food labeling

Introduction

An effective food labeling system has the potential to help reduce the prevalence of obesity by promoting healthier choices at the point-of-purchase. Calorie labeling is a new public health policy (Stein, 2010), but evidence for its effectiveness is equivocal (Blumenthal and Volpp, 2010; Borra, 2006; Dumanovsky et al., 2011; Krukowski et al., 2006; Philipson, 2005). Interpreting nutrition labeling is a health barrier as it requires both high literacy and numeracy skills (Rothman et al., 2006), yet even those with functional literacy and numeracy may not have the resources to use nutrition information to engage in consistently healthy behaviors (Easton et al., 2010). Therefore, it is important that food labeling systems can be easily understood by all consumers (Carbone and Zoellner, 2012; Nielsen-Bohlman et al., 2004).

Previous surveys have questioned the ability of individuals to understand and interpret nutrition labels, such as a guideline daily amount (Cowburn and Stockley, 2005; Gorton et al., 2009; Kim and Kim, 2009; Möser et al., 2010; Roberto et al., 2012). Traffic light food labels have been shown to assist individuals in making healthier choices when selecting foods (Morley et al., 2013; Roberto et al., 2012; Thorndike et al., 2012). Other studies have demonstrated that consumers are more likely to identify healthier items with traffic light labels than with other monochromatic labeling systems, such as a percentage-based or a healthy choice label (Borgmeier and Westenhoefer, 2009; Hawley et al., 2012; Kelly et al., 2009). Individuals who report looking at food labels tend to have healthier food consumption compared with those who do not utilize nutrition labels (Ollberding et al., 2010). A color-coded system that translates nutritional values for consumers may prompt individuals who are less health-conscious to look at and effectively utilize food labels, therefore increasing the reach of a food labeling intervention (Brownell and Koplan, 2011).

We demonstrated that a traffic light labeling system increased sales of healthy items and decreased sales of unhealthy items in a large hospital cafeteria (Thorndike et al., 2012), including among minority and less educated employees (Levy et al., 2012). To assess the influence of labeling on customers’ awareness of health and healthy purchases, we surveyed cafeteria customers before and after the traffic light labeling intervention had been implemented. We hypothesized that: 1) customers would be more likely to report increased awareness of the healthfulness and nutrition of food items at the time of purchase during the labeling intervention compared to the baseline period and 2) customers who noticed the traffic light labels would purchase a higher proportion of healthy items compared to customers who did not notice the labels.

Methods

This study was deemed exempt from institutional review board review by the Partners Human Research Committee on September 28, 2009.

Setting

The setting for this study was the main cafeteria at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) in Boston, Massachusetts between February and April 2010. The cafeteria is operated by the MGH Nutrition and Food Services. It is open seven days a week from 6:30 am to 8:00 pm, completing an average of 6,534 transactions per weekday.

Intervention

We implemented a traffic light labeling intervention to inform cafeteria patrons about the relative healthiness of cafeteria items. This labeling system was developed by two staff nutritionists and was based on the 2005 United States Department of Agriculture’s Dietary Guidelines (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and the U.S. Department of Agriculture, 2005). The nutrition information was gathered via CBORD Master Nutrient Database (CMND) that was created by The CBORD Group, Inc. and is a food and nutrition service management system for foodservice operations. The nutrition information is drawn from the United States Department of Agriculture nutrition database and is supplemented with vendor-specific product information. The details of the labeling system have been previously described (Levy et al., 2012; Thorndike et al., 2012).

Briefly, all food and beverages served in the cafeteria were categorized into four groups (food entrée, food item, food condiment, or beverage) and were rated on three positive and two negative criteria. The positive criteria were having the main ingredient (defined as one of the first three ingredients by weight) be a: 1) fruit or vegetable, 2) whole grain, or 3) lean protein/low fat dairy. The two negative criteria were saturated fat and calorie content. Assuming a 2000 calorie per day diet with less than 10% of calories from saturated fat, we set an upper limit of 5 grams of saturated fat per food entrée and 2 grams of saturated fat per food item, condiment, or beverage to account for three meals per day (each with 5 grams of saturated fat or less) plus 5 grams of saturated fat for discretionary calories. For calories, we assumed three meals per day at 500 calories each and 500 discretionary calories. Therefore, the two negative criteria for a food or beverage were: 1) saturated fat content of ≥5 grams per entrée or ≥2 grams per item, condiment, or beverage and 2) caloric content of ≥500 kcal per entrée, ≥200 kcal per item, or ≥100 kcal per condiment or beverage. For beverages, each additional 100 kcal was considered an additional negative criterion. Food and beverages with only positive criteria, or more positive than negative criteria, were categorized as green. Food and beverages with positive criteria equal to negative criteria or possessing only one negative criterion were categorized as yellow. Food and beverages with two negative criteria and no positive criteria were categorized as red. Diet beverages with zero calories and water were rated green despite lacking positive criteria.

The labeling intervention began in March 2010. Over one weekend, all food and beverages were labeled as red, yellow, or green on either the menu board located directly over individual food stations, the shelf where the food was located, or directly on the packaging. The labeling intervention was advertised to patrons as the MGH “Choose Well Eat Well” program, and the overall message focused on how to make better food selection choices in the cafeteria. New signage to describe the labeling was posted on a wall in the cafeteria, as well as on two large columns in the middle of the cafeteria. The signage highlighted that green meant “consume often,” yellow meant “consume less often,” and red meant “there is a better choice in green or yellow.” During the first two weeks, a dietitian was available to answer questions about the labels and educate customers about the program. We also supplied the cafeteria with pocket-sized pamphlets containing information about the labeling as well as the calorie, fat, and saturated fat content of all items.

Data collection and measures

Survey

During the baseline period and the intervention period, a systematic sample of cafeteria customers was interviewed by a research coordinator immediately after making a purchase. The interviewer approached customers at one of the seven cafeteria cash registers. After completing a survey with one customer, the interviewer would approach the next customer who completed a transaction at the next cash register. The survey took approximately 2 minutes to complete. Customers were interviewed on weekdays over the course of two weeks during the baseline period and over the course of seven weeks during the labeling intervention. The majority of surveys were conducted during the breakfast (8 am–10 am) or lunch (11:30 am–1:30 pm) time periods when the cafeteria was busiest. During the baseline period, 268 people were asked to participate in the survey and 204 completed surveys, giving a baseline response rate of 76%. During the intervention period, 496 people were asked to participate and 253 completed surveys, giving a response rate of 51% for the intervention phase. Overall survey response was 60%.

The survey collected data on respondents’ demographic characteristics (age category, sex, race) and whether the respondent was a hospital employee. One question asked about noticing any nutrition information in the cafeteria (“Did you look at nutrition information posted on the cafeteria menu or a food label before making your purchase today?”). Respondents were asked to identify the two factors that were most important in making their food and beverage choices from the following list: 1) taste, 2) price, 3) health/nutrition, 4) convenience, and 5) other. Finally, customers were asked to respond to the following two statements by answering either always, usually, rarely, or never: “I consider nutrition information when making a decision about which foods/beverages to eat/drink” and “I choose food that is healthy.” Respondents interviewed during the labeling intervention were also asked “Did you notice the red, yellow, green labels in the cafeteria today?” and if the response was “yes,” they were asked the follow-up question: “Did the labels influence your purchase today?” For each respondent, the interviewer recorded the items purchased and the time of the interview.

Cash register data

Prior to the baseline study period, all cafeteria cash registers were programmed to capture the information needed to identify an item as red, yellow, or green. Each survey respondent was linked to cash register data by identifying the cash register number and the time of the purchase to determine the proportion of red, yellow, and green items in the individual’s purchase. The cafeteria items recorded on the survey by the research coordinator were used to verify that the purchase in the database was associated with the correct respondent.

Analyses

There were 38 baseline surveys and 30 intervention surveys that could not be matched with cash register data and were excluded from the analyses, leaving 166 surveys from baseline and 223 surveys from intervention for analysis. We compared the demographics and survey responses between the respondents surveyed during the baseline period with the respondents surveyed during the labeling intervention using chi squared tests. We compared respondent purchases of red, yellow, and green items according to survey responses and study time period using multinomial logit models, adjusting standard errors for clustering by respondent. We considered multivariate logit models to control for demographic characteristics.

Results

The demographics of survey respondents did not differ significantly between the two time periods. Overall, more respondents were female (59%) and age 40 or over (58%). Survey respondents self-reported their race, and 77% were white, 11% were black, 6% were Hispanic/Latino, and 6% were Asian. The majority of respondents were hospital employees (81%). Because multivariate models controlling for demographics and time of purchase (breakfast vs. lunch) yielded qualitatively and quantitatively similar intervention effects, we report the unadjusted findings.

The Table 1 displays factors influencing cafeteria purchases during the baseline period and the labeling intervention. At baseline, 46% of respondents identified health and nutrition as being an important factor in making their food or beverage choice; after the labeling, this proportion increased to 61% (p = 0.004). The importance of taste and price also increased significantly during the labeling intervention compared to baseline, and the importance of convenience decreased. There was no significant difference between the baseline and the intervention periods in the proportion of respondents who reported that they “usually” or “always” choose a food that is healthy. A higher proportion of respondents reported that they looked at any nutrition information during the labeling intervention than during the baseline period (33% vs. 15%, p < 0.001), and this increase occurred for all sex and racial subgroups.

Table 1.

Factors influencing cafeteria purchase before and during the labeling intervention.

| Survey item | Baseline period (N = 166) | Labeling intervention (N = 223) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Most important factors in making food choice today (choice of 2) | |||

| Health/nutrition | 46% | 61 | 0.004 |

| Taste | 48% | 59 | 0.04 |

| Price | 11% | 19 | 0.02 |

| Convenience | 37% | 28 | 0.06 |

| Other | 15% | 4% | <0.001 |

| “Always” chooses a food that is healthy | 10% | 10% | 0.94 |

| Looks at nutrition information on cafeteria menu or food label before making a purchase | |||

| All respondents | 15% | 33% | <0.001 |

| Men | 11% | 29% | 0.005 |

| Women | 18% | 36% | 0.003 |

| White | 17% | 36% | 0.001 |

| Black | 5% | 16% | 0.23 |

| Hispanic | 18% | 43% | 0.19 |

| Asian | 8% | 18% | 0.44 |

This study was conducted at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, Massachusetts (2010).

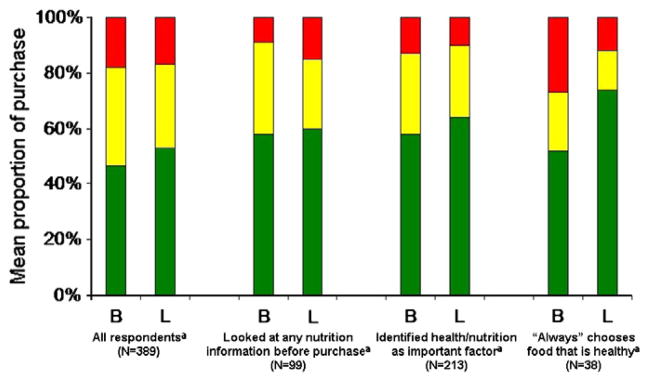

We examined the mean proportion of red, yellow, and green items purchased per transaction for survey respondents during the baseline period and during the labeling intervention (Fig. 1). For respondents who stated that health/nutrition was an important factor in their purchase and for respondents who reported that they “always” choose food that is healthy, green purchases increased and red purchases decreased during the labeling intervention compared to baseline, although these changes were not statistically significant.

Fig. 1.

This study was conducted at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, Massachusetts (2010)a P value for comparison between baseline (B) and labelling (L) is >0.05.

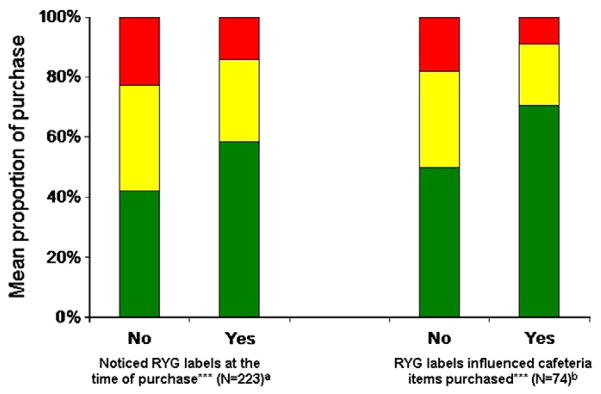

Fig. 2 demonstrates the proportion of red, yellow, and green items purchased by the respondents interviewed during the labeling intervention. Respondents who reported noticing the labels at the time of their purchase bought a higher proportion of green and lower proportion of red items compared to respondents who did not notice the labels (p < 0.001). Respondents who reported that the labels influenced their purchase bought a higher proportion of green items and a lower proportion of red items compared to respondents who reported that the labels did not influence their purchase (p < 0.001).

Fig. 2.

This study was conducted at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, Massachusetts (2010)***P value <0.001 for comparison of the proportion of red, yellow, and green (RYG) purhcases.a All respondentsb Respondents who reported that they had noticed RYG labels at the time of purchase.

Discussion

Our results demonstrate that a traffic light food labeling intervention increased consumers’ awareness of the healthfulness of food and beverages at the point-of-purchase. Compared to baseline, more customers reported that they had looked at nutrition information during the labeling intervention, and this improvement occurred among all ethnic/racial groups. Customers who reported noticing the traffic light labels bought a higher proportion of healthier items. This is the first study to our knowledge to evaluate the effectiveness of a food labeling system by linking consumer awareness of health and nutrition to objectively-measured food choices at the point-of-purchase.

The majority of patrons surveyed before and after the food labeling intervention reported that they “usually’ or “always” choose foods that are healthy. However, nearly half the items purchased at baseline by respondents who stated that they “always” choose healthy foods were not green (“healthy”) labeled foods or beverages. It is possible that these health-conscious consumers believed they were purchasing healthier items but were actually purchasing less healthy options due to an underestimation of the calorie or fat content of items or due to deficits in nutrition knowledge (Chandon and Wansink, 2007). When the traffic light food labeling intervention was implemented, these customers appeared to change their purchasing patterns in favor of the healthiest items, although this difference was not statistically significant. This trend is consistent with other research demonstrating that consumers may incorrectly identify “healthy” versus “less healthy” options and that preference for “healthy” items increases once additional nutrition information is provided (Burton et al., 2006; Dickson-Spillmann and Siegrist, 2010). Our findings suggest that, despite good intentions, many individuals are unaware of how to make healthy purchases. This lack of awareness may be independent of an individual’s motivation to make healthy food choices (McDonnell et al., 1998).

We demonstrated significantly healthier purchasing patterns for cafeteria patrons who noticed the labels and especially for those who reported that the labels had influenced their purchases. Only a few studies have assessed the impact of labels on food purchases (Levy et al., 2012; Sacks et al., 2009; Sutherland et al., 2010; Thorndike et al., 2012; Vyth et al., 2011), but to our knowledge, no studies have evaluated consumers’ awareness or concern about health at the point-of-purchase. Our study indicates that the proportion of respondents who identified health/nutrition as an important factor in their purchase increased after the traffic light labels were implemented, and respondents who identified health/nutrition as important tended to make healthier choices when the traffic light labels were available. These findings suggest that a traffic light labeling system may prompt consumers to consider their health at the point-of-purchase and therefore increase the likelihood that they will make a healthier choice.

A major strength of this study is that it linked consumer awareness of a specific intervention to the self-reported importance of health and nutrition and then objectively assessed frequency of healthy foods purchased. The food items were analyzed after the transaction had taken place, and therefore, the research was unlikely to have influenced food selection at the point-of-purchase. The study also has limitations. First, over 80% of the survey respondents were hospital employees. Though not all were clinicians, this population may be more health-conscious than the general public and therefore more likely to make healthier choices. Second, the improvements in healthy purchases between baseline and labeling did not reach statistical significance due to the relatively small sample size. However, we did see significant changes in healthy purchases after the labels were implemented in our larger analyses of overall cafeteria sales and of employee purchases (Levy et al., 2012; Thorndike et al., 2012). Third, we cannot determine if the impact of the labels on healthy purchases is sustained for individuals over time (Blackburn, 2005; Van Dillen et al., 2004). Finally, it is possible that the items purchased were intended for someone else.

Conclusion

Simplified labeling schemes have the potential to convey complex nutrition information quickly at the point-of-purchase. Our results suggest that traffic light food labels not only prompt more people to consider their health at the point-of-purchase but also increase the likelihood that these customers will make healthier choices. Employers, retailers, and institutions should consider implementing simplified labeling schemes in their food outlets to promote healthier eating habits of employees, customers, and students.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

There is no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Lillian Sonnenberg, Email: lsonnenberg@partners.org.

Emily Gelsomin, Email: egelsomin@partners.org.

Douglas E. Levy, Email: Dlevy3@partners.org.

Jason Riis, Email: jriis@hbs.edu.

Susan Barraclough, Email: sbarraclough@partners.org.

Anne N. Thorndike, Email: athorndike@partners.org.

References

- Blackburn G. Teaching, learning, doing: best practices in education. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;82:218S–221S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/82.1.218S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumenthal K, Volpp KG. Enhancing the effectiveness of food labeling in restaurants. JAMA. 2010;303:553–554. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borgmeier I, Westenhoefer J. Impact of different food label formats on healthiness evaluation and food choice of consumers: a randomized-controlled study. BMC Publ Health. 2009;9:184. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-184. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-9-184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borra S. Consumer perspectives on food labels. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;83:1235S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/83.5.1235S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownell KD, Koplan JP. Front-of-package nutrition labeling—an abuse of trust by the food industry. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2373–2375. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1101033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burton S, Creyer EH, Kees J, Huggins K. Attacking the obesity epidemic: the potential health benefits of providing nutrition information in restaurants. Am J Public Health. 2006;96:1669–1675. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.054973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carbone ET, Zoellner JM. Nutrition and health literacy: a systematic review to inform nutrition research and practice. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2012;112:254–265. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2011.08.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandon P, Wansink B. The biasing health halos of fast-food restaurant health claims: lower calorie estimates and higher side-dish consumption intentions. J Consum Res. 2007;34:301–314. [Google Scholar]

- Cowburn G, Stockley L. Consumer understanding and use of nutrition labelling: a systematic review. Public Health Nutr. 2005;8:21–28. doi: 10.1079/phn2005666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickson-Spillmann M, Siegrist M. Consumers’ knowledge of healthy diets and its correlation with dietary behaviour. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2010;24:54–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-277X.2010.01124.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumanovsky T, Huang CY, Nonas CA, Matte TD, Bassett MT, Silver LD. Changes in energy content of lunchtime purchases from fast food restaurants after introduction of calorie labeling: cross sectional customer surveys. BMJ. 2011;343:d4464. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d4464. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.d4464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Easton P, Entwistle VA, Williams B. Health in the ‘hidden population’ of people with low literacy. A systematic review of the literature. BMC Publ Health. 2010 doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-459. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-10-459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Gorton D, Ni Mhurchu C, Chen MH, Dixon R. Nutrition labels: a survey of use, understanding and preferences among ethnically diverse shoppers in New Zealand. Public Health Nutr. 2009;12:1359–1365. doi: 10.1017/S1368980008004059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawley KL, Roberto CA, Bragg MA, Liu PJ, Schwartz MB, Brownell KD. The science on front-of-package food labels. Public Health Nutr. 2012 Mar 22; doi: 10.1017/S1368980012000754. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S1368980012000754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kelly B, Hughes C, Chapman K, et al. Consumer testing of the acceptability and effectiveness of front-of-pack food labeling systems for the Australian grocery market. Health Promot Int. 2009;24:120–129. doi: 10.1093/heapro/dap012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim WK, Kim J. A study on the consumer’s perception of front-of-pack nutrition labeling. Nutr Res Pract. 2009;3:300–306. doi: 10.4162/nrp.2009.3.4.300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krukowski RA, Harvey-Berino J, Kolodinsky J, Narsana R, DeSisto T. Consumers may not use or understand calorie labeling in restaurants. J Am Diet Assoc. 2006;106:917–920. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2006.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy DE, Riis J, Sonnenberg LM, Barraclough SJ, Thorndike AN. Food choices of minority and low-income employees: a cafeteria intervention. Am J Prev Med. 2012;43:240–248. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonnell GE, Keith Roberts DC, Lee C. Stages of change and reduction of dietary fat: effect of knowledge and attitudes in an Australian university population. JNE. 1998;30:37–44. [Google Scholar]

- Morley B, Scully M, Martin J, et al. What types of nutrition menu labelling lead consumers to select less energy-dense fast food? An experimental study. Appetite. 2013;67:8–15. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2013.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Möser A, Hoefkens C, Van Camp J, Verbeke W. Simplified nutrient labeling: consumers’ perception in Germany and Belgium. J Verbr Lebensm. 2010;5:169–180. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen-Bohlman L, Panzer AM, Kindig DA. Health literacy: a prescription to end confusion. The National Academies Press; 2004. [Accessed April 12, 2012]. http://www.nap.edu/catalog.php?record_id=10883. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ollberding NJ, Wolf RL, Contento I. Food label use and its relation to dietary intake among US adults. J Am Diet Assoc. 2010;110:1233–1237. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2010.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philipson T. Government perspective: Food labeling. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;82:262S–264S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/82.1.262S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberto CA, Bragg MA, Schwartz MB, et al. Facts up front versus traffic light food labels: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Prev Med. 2012;43:134–141. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothman RL, Housam R, Weiss H, et al. Patient understanding of food labels: the role of literacy and numeracy. Am J Prev Med. 2006;31:391–398. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sacks G, Rayner M, Swinburn B. Impact of front-of-pack ‘traffic-light’ nutrition labelling on consumer food purchases in the UK. Health Promot Int. 2009;24:344–352. doi: 10.1093/heapro/dap032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein K. A national approach to restaurant menu labeling: the patient protection and affordable health care act, section 4205. J Am Diet Assoc. 2010;110 (1280–1286):1288–1289. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2010.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutherland LA, Kaley LA, Fischer L. Guiding stars: the effect of a nutrition navigation program on consumer purchases at the supermarket. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;91:1090S–1094S. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2010.28450C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorndike AN, Sonnenberg L, Riis J, Barraclough S, Levy DE. A 2-phase labeling and choice architecture intervention to improve healthy food and beverage choices. Am J Public Health. 2012;102:527–533. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health, Human Services, U.S. Department of Agriculture. Dietary Guidelines for Americans. 6. Government Printing Office; Washington, DC: U.S: 2005. [Accessed April 12, 2012]. January 2005 http://www.health.gov/dietaryguidelines/dga2005/document/ [Google Scholar]

- Van Dillen SME, Hiddink GJ, Koelen MA, de Graaf C, van Woerkum CMJ. Perceived relevance and information needs regarding food topics and preferred information sources among Dutch adults: results of a quantitative consumer study. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2004;58:1306–1313. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vyth EL, Steenhuis IHM, Heymans MW, Roodenburg AJC, Brug J, Seidell JC. Influence of placement of a nutrition logo on cafeteria menu items on lunch-time food choices at Dutch work sites. J Am Diet Assoc. 2011;111:131–136. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2010.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]