Abstract

The identification of molecular markers, useful for therapeutic decisions in pancreatic cancer patients, is crucial for advances in disease management. Gemcitabine, although a cornerstone of current therapy, has limited efficacy. RRM1 is a key molecule for gemcitabine efficacy and is also involved in tumor progression. We determined in situ RRM1 and excision repair cross complementation group 1 (ERCC1) protein levels in 68 pancreatic cancer patients. All had R0 resections without preoperative therapy. Protein levels were determined by automated quantitative analysis (AQUA), a fluorescence-based immunohistochemical method. The relationship between protein expressions and clinical outcomes, including response to gemcitabine at the time of disease recurrence, was determined. Patients with high RRM1 showed significantly better overall survival than patients with low expression (P=0.0196). There was a trend toward better overall survival for patient with high ERCC1 (P=0.0552). When both markers were considered together, patients with both high RRM1 and ERCC1 faired the best in terms of overall and disease-free survival (P=0.0066, P=0.0127). In addition, treatment benefit from gemcitabine in patients with disease recurrence was observed only in patients with low RRM1. The combination of RRM1 and ERCC1 expression is prognostic in pancreatic cancer patients after a complete resection. On disease recurrence, only patients with low RRM1 derive benefit from gemcitabine.

Keywords: pancreatic cancer, RRM1, ERCC1, AQUA, prognosis, gemcitabine

Introduction

Pancreatic cancer is one of the leading causes of tumor-related mortalities. The prognosis of patients after complete resection is poor, and more than 50% of patients develop tumor recurrence at distant or locoregional sites, with an estimated 5-year survival of only 20% (Kayahara et al., 1993; Nitecki et al., 1995; Staley et al., 1996; Sener et al., 1999; Li et al., 2004). The addition of chemotherapy and radiotherapy to surgical resection is important, and gemcitabine, a pyrimidine nucleotide analogue, has become the standard chemotherapeutic agent in such programs (Burris et al., 1997; Oettle et al., 2007) (Rothenberg et al., 1996). However, the clinical response rate to gemcitabine remains modest, mainly because of the profound chemoresistance inherent in pancreatic cancer. The selection of patients who derive a true benefit from gemcitabine could be an important stepping stone toward improvement of outcome of pancreatic cancer.

RRM1, the gene that encodes the regulatory subunit of ribonucleotide reductase, is a key determinant of gemcitabine efficacy. In various cancers, we and others have described that overexpression of the RRM1 gene is strongly associated with gemcitabine resistance (Cao et al., 2003; Rosell et al., 2004; Bergman et al., 2005; Bepler et al., 2006; Nakahira et al., 2007). However, there is no clinical study that investigated the correlation between RRM1 protein expression and gemcitabine resistance.

On the other hand, the expression of RRM1 was also reported to correlate with the tumorigenic and metastatic potential of lung cancer (Gautam et al., 2003), and an oncogenic ras-transformed cell line with high expression of an RRM1 transgene had reduced metastatic potential (Fan et al., 1997). Furthermore, high expression of RRM1 in transgenic mice is associated with resistance to carcinogen-induced lung tumorigenesis (Gautam and Bepler, 2006). Recently, overexpression of RRM1 and the excision repair cross-complementation group 1 (ERCC1) gene product was reported to correlate with favorable prognosis in non-small-cell lung cancer (Zheng et al., 2007).

The present study was designed to evaluate the protein expression of RRM1 and ERCC1 in pancreatic cancer by automated quantitative analysis (AQUA). We describe the relationship between RRM1 and ERCC1 expression, the association between the expression of these proteins and prognosis, as well as the response to gemcitabine therapy. To our knowledge, this study is the first to examine both the prognostic and predictive aspects of RRM1 in the same clinical samples.

Results

RRM1 and ERCC1 expression characteristics

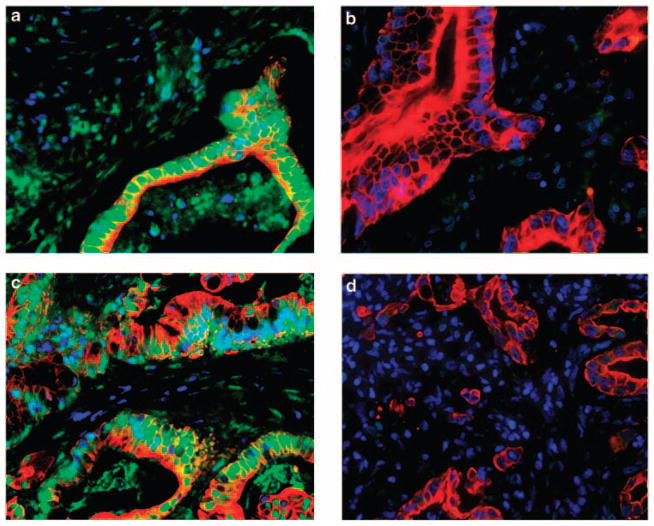

We constructed a tissue microarray using triplicate 0.6- mm cores from formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded specimens of the primary tumor. Immunostaining showed a granular nuclear pattern for RRM1, and a fine granular pattern for ERCC1 (Figure 1). Next, we used AQUA to analyse the expression levels of RRM1 and ERCC1 in specimens obtained from 68 patients. The scores of RRM1 ranged from 116 to 1644 (median, 539; mean, 546) for all specimens, and the scores of ERCC1 ranged from 55 to 1469 (median 382, mean 412).

Figure 1.

Staining for RRM1 and excision repair cross-complementation group 1 (ERCC1) proteins. (a) RRM1-positive sample. Note the granular nuclear pattern. Nucleus, blue; cytoplasm, red; RRM1, green; and merged, light blue to light green. (b) RRM1-negative sample. Nucleus, blue; and cytoplasm, red. (c) ERCC1-positive sample. Note the fine granular pattern in the nucleus. Nucleus, blue; cytoplasm, red; ERCC1, green; and merged, light blue to light green. (d) ERCC1-negative sample. Nucleus, blue; and cytoplasm, red.

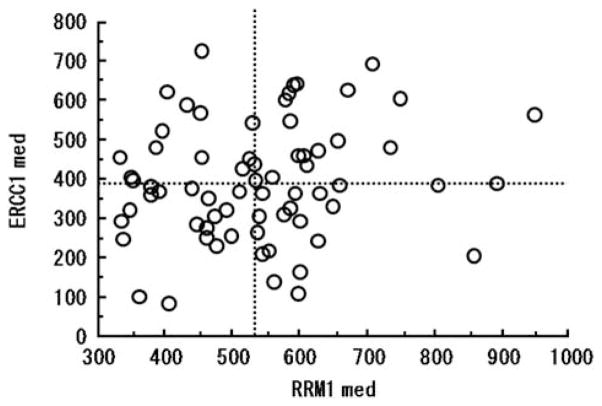

The average score of triplicate tissues from each patient was used for analysis of the association between staining and clinical parameters. The AQUA scores for RRM1 did not correlate significantly with those of ERCC1 (r=0.172, P=0.1610) (Figure 2). The median values of RRM1 and ERCC1 expression levels were used to divide the patients into high and low expression groups. There were no significant differences between patients with high and low tumoral RRM1 expression or high and low tumoral ERCC1 expression with respect to age, sex, histopathological type (well/mod/poor), tumor size, tumor location (head/body/tail), pathological depth of tumor (pT1/T2/T3), the total number of resected lymph nodes, pathological lymph node metastasis (negative/positive) and the number of metastatic lymph nodes, and whether or not gemcitabine was used as chemotherapy (Table 1).

Figure 2.

Relationship between automated quantitative analysis (AQUA) scores of RRM1 and excision repair cross-complementation group 1 (ERCC1) expression. RRM1 expression did not correlate with that of ERCC1 (r=0.172, P=0.161).

Table 1.

Relationship between protein expression levels and clinicopathological factors

|

RRM1 expression level

|

ERCC1 expression level

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High | Low | P-value | High | Low | P-value | |

| Age (years) (mean ± s.d.) | 66.8 ± 7.6 | 64.4 ± 7.9 | 0.220 | 64.6 ± 7.7 | 66.6 ± 7.8 | 0.283 |

| Sex (male/female) | 15/19 | 18/16 | 0.628 | 15/19 | 18/16 | 0.628 |

| Histopathology (well/mod/poor) | 17/14/3 | 9/18/7 | 0.102 | 12/19/3 | 14/13/7 | 0.237 |

| Tumor size (cm) (mean ± s.d.) | 27.4 ± 9.3 | 26.7 ± 8.2 | 0.752 | 25.2 ± 8.2 | 28.9 ± 8.9 | 0.077 |

| Tumor location (head/body/tail) | 27/6/1 | 27/4/3 | 0.497 | 27/4/3 | 27/6/1 | 0.497 |

| pT (T1/T2/T3) | 1/1/32 | 1/0/33 | 0.602 | 1/1/32 | 1/0/33 | 0.602 |

| Total number of resected lymph node | 34.4 ± 12.9 | 30.3 ± 13.6 | 0.243 | 30.8 ± 10.6 | 34.3 ± 15.7 | 0.330 |

| PN (positive/negative) | 12/22 | 17/17 | 0.327 | 18/16 | 11/23 | 0.141 |

| Total number of metastatic lymph node | 1.6 ± 1.9 | 1.0 ± 1.7 | 0.202 | 1.1 ± 1.7 | 1.5 ± 1.9 | 0.315 |

| Gem therapy (+/−) | 14/20 | 14/20 | 0.999 | 13/21 | 15/19 | 0.806 |

Abbreviation: ERCC1, excision repair cross-complementation group 1.

Relationship between RRM1/ERCC1 expression and prognosis

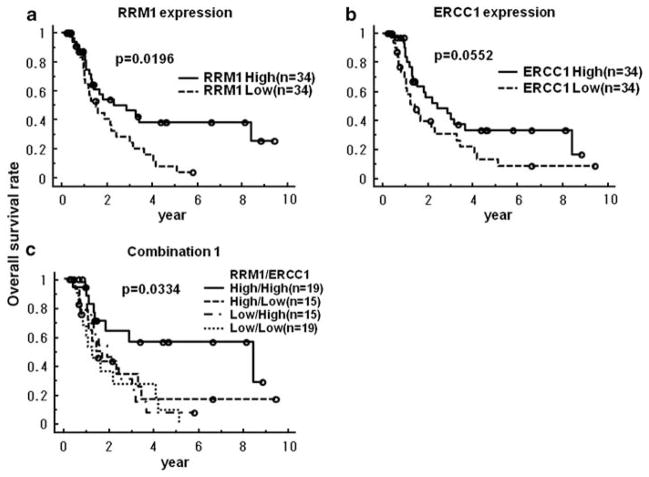

The median overall survival of all patients was 16.3 months (4.3–113) and the median disease-free survival was 10.3 months (2–106). The Kaplan–Meier overall survival estimates were significantly better for patients with high RRM1 expression compared with those having low RRM1 expression levels (3-year survival; 46.3 versus 28.6%, P=0.0196) (Figure 3a). Likewise, patients with high ERCC1 expression had a better overall survival than those with low levels of expression; although this difference was only marginally significant (P=0.0552) (Figure 3b). When we divided the 68 patients into four groups; that is, high tumoral expression of both proteins (High/High, n=19), high expression of only RRM1 (High/Low, n=15), high expression of only ERCC1 (Low/High, n=15) and low expression of both proteins (Low/Low, n=19); only patients of the High/High group had a significantly better prognosis than the others (3-year survival; 56.7 versus 30.5%, P=0.0066) (Figure 3c, Supplementary Figure 1).

Figure 3.

Relationship between RRM1 and excision repair cross-complementation group 1 (ERCC1) expression levels and overall survival rate. (a) Relationship between RRM1 and overall survival is significant (3-year survival; 46.3 versus 28.6%, P=0.0196). (b) Relationship between ERCC1 and overall survival is marginal (P=0.0552). (c) Relationship between the combination of RRM1 and ERCC1 expression levels in the same tumor and overall survival rate. Only high expression levels of RRM1 and ERCC1 in the same tumor related with the improvement of overall survival rate (P=0.0334).

With regard to disease-free survival, high ERCC1 expression levels were significantly associated with better outcome (3-year survival; 30.2% for high versus 23.1% for low, P=0.0454). There was no significant difference in disease-free survival between the high and low RRM1 expression groups (Supplementary Figures 2A and B). With respect to the combination of RRM1 and ERCC1, only the High/High group showed a significantly better disease-free survival compared with the other groups (3-year survival, 43.2 versus 19.2%, P=0.0127) (Supplementary Figures 2C and D).

Univariate and multivariate analysis of factors associated with prognosis

We investigated the prognostic significance of various clinicopathological factors in pancreatic cancer patients who underwent radical resection. Univariate analysis showed that only the pathological type and absence or presence of lymph node metastases, were prognostically significant for disease-free survival (P=0.034, 0.025, respectively), and both parameters had marginal significance for overall survival (P=0.078, 0.084, respectively) (Table 2). Multivariate analysis identified the RRM1 expression level as the only independent determinant of overall survival (hazard ratio (HR) 1.89, P=0.046), and none of the parameters tested was selected by the analysis as a significant prognostic factor in disease-free survival.

Table 2.

Prognostic factors for postoperative survival by Cox’s proportional hazard model

|

Univariate analysis

|

Multivariate analysis

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

DFS

|

OS

|

DFS |

OS

|

|||||

| HR | P-value | HR | P-value | HR | P-value | HR | P-value | |

| Histology (poor, mod/well) | 1.91 | 0.034 | 1.75 | 0.078 | 1.77 | 0.066 | 1.56 | 0.172 |

| PN (positive/negative) | 2.00 | 0.025 | 1.76 | 0.084 | 1.73 | 0.107 | 1.50 | 0.256 |

| RRM1 expression (low/high) | 1.55 | 0.129 | 2.04 | 0.022 | 1.39 | 0.265 | 1.89 | 0.046 |

| ERCC1 expression (low/high) | 1.75 | 0.048 | 1.78 | 0.059 | 1.42 | 0.265 | 1.54 | 0.194 |

Abbreviations: DFS, disease-free survival; ERCC1, excision repair cross-complementation group 1; HR, hazard ratio and OS, overall survival.

RRM1 expression and response to gemcitabine

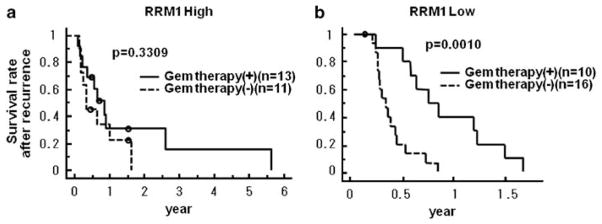

Of all the 68 patients, 28 received therapy with single-agent gemcitabine. In 23 patients, this treatment was initiated at the time of tumor recurrence. To elucidate the relationship between RRM1 expression level and gemcitabine therapy, we used survival after recurrence, which represented the period from starting gemcitabine therapy or other therapies in 50 patients with relapse, until death. First, we examined the survival benefit of gemcitabine. The 23 patients who were treated with gemcitabine had a significantly better survival than those who did not (P=0.0074) (Supplementary Figure 3). After dividing patients that were treated with gemcitabine into high and low RRM1 expression groups, only patients with low RRM1 expression benefited from gemcitabine therapy (P=0.0010) (Figure 4b). The survival of patients with high RRM1 expression treated with gemcitabine was not significantly better than of those not treated with gemcitabine (P=0.3309) (Figure 4a). The interaction term between RRM1 expression and gemcitabine treatment was significant for survival after recurrence (P=0.0109).

Figure 4.

Relationship between survival after recurrence and patients treated with or without gemcitabine (a) in high RRM1 expression group, and (b) in low expression group. Only patients with low RRM1 expression benefited from gemcitabine therapy (P=0.0010).

Discussion

Ribonucleotide reductase, composed of the regulatory subunit RRM1 and the catalytic subunit RRM2, is a key enzyme involved in DNA synthesis, catalyzing the biosynthesis of deoxyribonucleotides from the corresponding ribonucleotides (Wright et al., 1990; Hurta and Wright, 1992). ERCC1, a structure-specific DNA repair endonuclease responsible for the 5′ incision, has a key role in the removal of adducts from genomic DNA through the nucleotide excision repair pathway (Reardon et al., 1999; Niedernhofer et al., 2004; Ceppi et al., 2006). RRM1 is reported to influence cell survival, probably through interaction with the phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN), which is an inhibitor of cell proliferation, and suppresses cell migration and invasion by reducing the phosphorylation of focal adhesion kinase (Gautam et al., 2003; Bepler et al., 2004). In lung cancer, the expression levels of RRM1 and ERCC1 are significantly correlated (Bepler et al., 2006; Ceppi et al., 2006).

Gemcitabine is the first line cytotoxic agent for treatment of patients with advanced pancreatic cancer, and it is the only agent with proven benefit in a large adjuvant clinical trial (Oettle et al., 2007). However, it is estimated that only 25% of patients benefit from gemcitabine (Burris et al., 1997). RRM1 expression appears to be the key determinant of gemcitabine resistance (Dumontet et al., 1999; Goan et al., 1999; Jung et al., 2001). This is partially due to expansion of the dNTP pool, which competitively inhibits the incorporation of gemcitabine triphosphate into DNA (Plunkett et al., 1996). Another mechanism is the direct interaction between RRM1 and gemcitabine with RRM1 acting as a ‘molecular sink’ for gemcitabine (Davidson et al., 2004; Bergman et al., 2005). ERCC1 is reported to be associated with the repair of cisplatin-induced DNA adducts in ovarian cancer (Li et al., 2000), gastric cancer (Metzger et al., 1998), colorectal cancer (Shirota et al., 2001), lung cancer (Olaussen et al., 2006) and esophageal cancer (Joshi et al., 2005; Kim et al., 2008).

Quantitative analysis of gene expression in pancreatic cancer is challenging because it contains more stromal tissue than other cancers (Sato et al., 2004; Bachem et al., 2005; Infante et al., 2007), which makes laser microdissection a necessity to obtain gene expression of tumor tissue (Giovannetti et al., 2006). Quantitative analysis of the RRM1 protein had been difficult because of technical limitations. However, an automated, quantitative in situ assessment of protein expression was developed recently (Camp et al., 2002), and applied for objective and practical evaluation of RRM1 and ERCC1 protein expression levels in tumor specimens (Zheng et al., 2007). In this study, we used the above mentioned technology for gene expression analysis in pancreatic cancer specimens.

We found that the expression levels of RRM1 and ERCC1 affected the clinical outcome similar to that described in non-small-cell lung cancer (Zheng et al., 2007). Patients with high levels of expression of both proteins had the best prognosis, including both diseasefree survival and overall survival. However, once treatment with gemcitabine was initiated at the time of recurrence, it was only the group of patients with low levels of RRM1 that benefited significantly from this intervention. In other words, patients with high tumoral RRM1 levels may as well be treated with other agents, such as S-1 or oxaliplatin plus 5-fluorouracil plus leukovorin (CONKO-003), instead of gemcitabine (Ueno et al., 2005; Okusaka et al., 2008; Saif, 2008). In contrast, patients with low tumoral RRM1 levels showed improved survival following treatment with gemcitabine (Moore et al., 2007; Boeck and Heinemann, 2008). Many clinical trials of anticancer drugs, including molecular targeting agents, did not result in the improvement of outcome when conducted in unselected groups of patients (Heinemann et al., 2006; Herrmann et al., 2007; Cascinu et al., 2008). However, if patients can be divided into groups with high or low likelihood of benefit from gemcitabine, a more rational design of future trials becomes available (Simon et al., 2007). We believe that future treatment strategies for pancreatic cancer should be more precise and tailored to individual patients, and RRM1 may be one of the candidate molecules for the stratification. We found that RRM1 and ERCC1 were not significantly coexpressed in pancreatic cancer, which is different from several previous reports in non-small-cell lung cancer (Ceppi et al., 2006; Zheng et al., 2007). This discrepancy may be explained by differences in tissue of origin and mechanisms of carcinogenesis between pancreatic cancer and lung cancer.

It is important to carry out prospective tailored therapeutic trials in pancreatic cancer with the goal of improving the clinical outcome, and it is our opinion that RRM1 and ERCC1 could play an important role in the design of such trials.

Materials and methods

Patients

Between January 1992 and March 2008, 166 patients underwent surgery for pancreatic cancer at Osaka University Hospital. We excluded 84 patients for the following reasons: (1) tumors were not resectable in 26 patients because of liver metastases or peritoneal carcinomatosis, (2) surgery resulted in R1 (residual microscopic cancer) or R2 (residual macroscopic cancer) resections in 21 patients, (3) chemotherapy or chemoradiotherapy was provided preoperatively to 37 patients and (4) lack of neutral-buffered formalin-fixed and paraffinembedded tumor blocks or/and clinical follow-up information for study purposes in 14 cases. As the natural history of variant pancreatic neoplasms differs from the usual pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, patients with intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms, mucinous cystic adenocarcinomas and medullary adenocarcinomas were excluded from this study. Supplementary Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of the 68 patients who were enrolled in this study. They included 33 men and 35 women with a mean age of 60.7 ± 7.8 years (± s.d.). All patients had R0 (no residual cancer) resections by pancreaticoduodenectomy in 54 patients, distal pancreatectomy in 12 patients and other resections in 2 patients. The histopathological grading showed poorly, moderately, and well-differentiated adenocarcinoma in 10, 32 and 26 patients, respectively. The UICC-TNM classification was 2, 1 and 65 patients with pT1, pT2 and pT3; 29, 33 and 6 patients with pN0, pN1 and pM1lym; and 1, 1, 27, 33 and 6 patients with stage IA, IB, IIA, IIB and IV, respectively. None of the patients had received neoadjuvant therapy preoperatively. All 68 patients were followed until disease recurrence and/or death. The median follow-up period was 16.3 months (range, 4.3–113), the 5-year survival rate was 23.4%, and the recurrence of disease was observed in 50 patients. Treatment with gemcitabine was carried out in 28 patients; 5 patients received it as adjuvant chemotherapy and 23 patients received it after disease recurrence. Radiation therapy was not carried out during all the follow-up period.

Immunofluorescence and automated quantitative analysis

We carried out immunostaining after constructing a tissue microarray. Immunofluorescence combined with AQUA was used to assess in situ expression of the target molecules as described previously (Zheng et al., 2007). Antigens were retrieved by incubating the tissue in a microwave oven. Optimal concentrations of antisera and antibodies were used to detect RRM1, ERCC1 and cytokeratin. The antiserum to RRM1 was generated from rabbits and affinity-purified (R1AS-6) as described previously (Zheng et al., 2007). Commercially available antibodies were used for the analysis of ERCC1 (Ab-2 clone 8F1, MS-671-R7, Laboratory Vision Corporation, Fremont, CA, USA) and cytokeratin (antihuman pancytokeratin AE1/AE3, M3515 and Z0622, Dako Cytomation, Glostrup, Denmark) (Zheng et al., 2007). They were visualized with the use of fluorochrome-labeled secondary antibodies. The final slides were scanned with SpotGrabber (HistoRx, New Haven, CT, USA), and images were analysed with AQUA (version 1.6, PM-2000, HistoRx). The AQUA scores ranged from 0 (no expression) to 3000 (maximal observed expression).

Statistical analysis and ethical issues

Data are expressed as mean ± s.d. Differences in continuous values were evaluated by the Student’s t-test (Table 1). The Fisher’s exact probability test was used to compare discrete variables (Table 1). We evaluated correlations between AQUA scores of RRM1 and ERCC1 by Pearson’s correlation coefficient (Figure 2). Disease-free and overall survival rates were estimated by the Kaplan–Meier method and compared using the log-rank test (Table 1, Figures 3 and 4). Cox’s proportional hazard regression model with stepwise comparisons was used to analyse independent prognostic factors (Table 2). The predictive value of RRM1 was studied by testing the interaction between RRM1 expression and gemcitabine treatment in the same Cox model. A P-value <0.05 was used to indicate statistical significance.

This study was analysed by the statistical expert in our laboratory and the study protocol was approved by the Human Ethics Review Committee of Osaka University, and a signed consent form was obtained from each subject.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was partially supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant R01-CA129343 to GB and by a grant-inaid for cancer research from the Ministry of Culture and Science of Japan.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on the Oncogene website (http://www.nature.com/onc)

References

- Bachem MG, Schunemann M, Ramadani M, Siech M, Beger H, Buck A, et al. Pancreatic carcinoma cells induce fibrosis by stimulating proliferation and matrix synthesis of stellate cells. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:907–921. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.12.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bepler G, Kusmartseva I, Sharma S, Gautam A, Cantor A, Sharma A, et al. RRM1 modulated in vitro and in vivo efficacy of gemcitabine and platinum in non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:4731–4737. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bepler G, Sharma S, Cantor A, Gautam A, Haura E, Simon G, et al. RRM1 and PTEN as prognostic parameters for overall and disease-free survival in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:1878–1885. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergman AM, Eijk PP, Ruiz van Haperen VW, Smid K, Veerman G, Hubeek I, et al. in vivo induction of resistance to gemcitabine results in increased expression of ribonucleotide reductase subunit M1 as the major determinant. Cancer Res. 2005;65:9510–9516. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boeck S, Heinemann V. Second-line therapy in gemcitabine-pretreated patients with advanced pancreatic cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:1178–1179. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.3304. author reply 1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burris HA, III, Moore MJ, Andersen J, Green MR, Rothenberg ML, Modiano MR, et al. Improvements in survival and clinical benefit with gemcitabine as first-line therapy for patients with advanced pancreas cancer: a randomized trial. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:2403–2413. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.6.2403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camp RL, Chung GG, Rimm DL. Automated subcellular localization and quantification of protein expression in tissue microarrays. Nat Med. 2002;8:1323–1327. doi: 10.1038/nm791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao MY, Lee Y, Feng NP, Xiong K, Jin H, Wang M, et al. Adenovirus-mediated ribonucleotide reductase R1 gene therapy of human colon adenocarcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:4553–4561. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cascinu S, Berardi R, Labianca R, Siena S, Falcone A, Aitini E, et al. Cetuximab plus gemcitabine and cisplatin compared with gemcitabine and cisplatin alone in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer: a randomised, multicentre, phase II trial. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9:39–44. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(07)70383-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ceppi P, Volante M, Novello S, Rapa I, Danenberg KD, Danenberg PV, et al. ERCC1 and RRM1 gene expressions but not EGFR are predictive of shorter survival in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer treated with cisplatin and gemcitabine. Ann Oncol. 2006;17:1818–1825. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdl300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson JD, Ma L, Flagella M, Geeganage S, Gelbert LM, Slapak CA. An increase in the expression of ribonucleotide reductase large subunit 1 is associated with gemcitabine resistance in non-small cell lung cancer cell lines. Cancer Res. 2004;64:3761–3766. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-3363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumontet C, Fabianowska-Majewska K, Mantincic D, Callet Bauchu E, Tigaud I, Gandhi V, et al. Common resistance mechanisms to deoxynucleoside analogues in variants of the human erythroleukaemic line K562. Br J Haematol. 1999;106:78–85. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1999.01509.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan H, Huang A, Villegas C, Wright JA. The R1 component of mammalian ribonucleotide reductase has malignancy-suppressing activity as demonstrated by gene transfer experiments. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:13181–13186. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.24.13181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gautam A, Bepler G. Suppression of lung tumor formation by the regulatory subunit of ribonucleotide reductase. Cancer Res. 2006;66:6497–6502. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gautam A, Li ZR, Bepler G. RRM1-induced metastasis suppression through PTEN-regulated pathways. Oncogene. 2003;22:2135–2142. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giovannetti E, Del Tacca M, Mey V, Funel N, Nannizzi S, Ricci S, et al. Transcription analysis of human equilibrative nucleoside transporter-1 predicts survival in pancreas cancer patients treated with gemcitabine. Cancer Res. 2006;66:3928–3935. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goan YG, Zhou B, Hu E, Mi S, Yen Y. Overexpression of ribonucleotide reductase as a mechanism of resistance to 2,2- difluorodeoxycytidine in the human KB cancer cell line. Cancer Res. 1999;59:4204–4207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinemann V, Quietzsch D, Gieseler F, Gonnermann M, Schonekas H, Rost A, et al. Randomized phase III trial of gemcitabine plus cisplatin compared with gemcitabine alone in advanced pancreatic cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:3946–3952. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.1490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrmann R, Bodoky G, Ruhstaller T, Glimelius B, Bajetta E, Schuller J, et al. Gemcitabine plus capecitabine compared with gemcitabine alone in advanced pancreatic cancer: a randomized, multicenter, phase III trial of the Swiss Group for Clinical Cancer Research and the Central European Cooperative Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:2212–2217. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.0886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurta RA, Wright JA. Alterations in the activity and regulation of mammalian ribonucleotide reductase by chlorambucil, a DNA damaging agent. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:7066–7071. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Infante JR, Matsubayashi H, Sato N, Tonascia J, Klein AP, Riall TA, et al. Peritumoral fibroblast SPARC expression and patient outcome with resectable pancreatic adenocarcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:319–325. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.8824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi MB, Shirota Y, Danenberg KD, Conlon DH, Salonga DS, Herndon JE, II, et al. High gene expression of TS1, GSTP1, and ERCC1 are risk factors for survival in patients treated with trimodality therapy for esophageal cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:2215–2221. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-1387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung CP, Motwani MV, Schwartz GK. Flavopiridol increases sensitization to gemcitabine in human gastrointestinal cancer cell lines and correlates with down-regulation of ribonucleotide reductase M2 subunit. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7:2527–2536. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kayahara M, Nagakawa T, Ueno K, Ohta T, Takeda T, Miyazaki I. An evaluation of radical resection for pancreatic cancer based on the mode of recurrence as determined by autopsy and diagnostic imaging. Cancer. 1993;72:2118–2123. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19931001)72:7<2118::aid-cncr2820720710>3.0.co;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim MK, Cho KJ, Kwon GY, Park SI, Kim YH, Kim JH, et al. Patients with ERCC1-negative locally advanced esophageal cancers may benefit from preoperative chemoradiotherapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:4225–4231. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li D, Xie K, Wolff R, Abbruzzese JL. Pancreatic cancer. Lancet. 2004;363:1049–1057. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15841-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q, Yu JJ, Mu C, Yunmbam MK, Slavsky D, Cross CL, et al. Association between the level of ERCC-1 expression and the repair of cisplatin-induced DNA damage in human ovarian cancer cells. Anticancer Res. 2000;20:645–652. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metzger R, Leichman CG, Danenberg KD, Danenberg PV, Lenz HJ, Hayashi K, et al. ERCC1 mRNA levels complement thymidylate synthase mRNA levels in predicting response and survival for gastric cancer patients receiving combination cisplatin and fluorouracil chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:309–316. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.1.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore MJ, Goldstein D, Hamm J, Figer A, Hecht JR, Gallinger S, et al. Erlotinib plus gemcitabine compared with gemcitabine alone in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer: a phase III trial of the National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:1960–1966. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.9525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakahira S, Nakamori S, Tsujie M, Takahashi Y, Okami J, Yoshioka S, et al. Involvement of ribonucleotide reductase M1 subunit overexpression in gemcitabine resistance of human pancreatic cancer. Int J Cancer. 2007;120:1355–1363. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niedernhofer LJ, Odijk H, Budzowska M, van Drunen E, Maas A, Theil AF, et al. The structure-specific endonuclease Ercc1-Xpf is required to resolve DNA interstrand cross-link-induced double-strand breaks. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:5776–5787. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.13.5776-5787.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nitecki SS, Sarr MG, Colby TV, van Heerden JA. Long-term survival after resection for ductal adenocarcinoma of the pancreas. Is it really improving? Ann Surg. 1995;221:59–66. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199501000-00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oettle H, Post S, Neuhaus P, Gellert K, Langrehr J, Ridwelski K, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy with gemcitabine vs observation in patients undergoing curative-intent resection of pancreatic cancer: a randomized controlled trial. Jama. 2007;297:267–277. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.3.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okusaka T, Funakoshi A, Furuse J, Boku N, Yamao K, Ohkawa S, et al. A late phase II study of S-1 for metastatic pancreatic cancer. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2008;61:615–621. doi: 10.1007/s00280-007-0514-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olaussen KA, Dunant A, Fouret P, Brambilla E, Andre F, Haddad V, et al. DNA repair by ERCC1 in non-small-cell lung cancer and cisplatin-based adjuvant chemotherapy. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:983–991. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa060570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plunkett W, Huang P, Searcy CE, Gandhi V. Gemcitabine: preclinical pharmacology and mechanisms of action. Semin Oncol. 1996;23:3–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reardon JT, Vaisman A, Chaney SG, Sancar A. Efficient nucleotide excision repair of cisplatin, oxaliplatin, and Bis-aceto-ammine-dichloro-cyclohexylamine-platinum(IV) (JM216) platinum intrastrand DNA diadducts. Cancer Res. 1999;59:3968–3971. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosell R, Danenberg KD, Alberola V, Bepler G, Sanchez JJ, Camps C, et al. Ribonucleotide reductase messenger RNA expression and survival in gemcitabine/cisplatin-treated advanced non-small cell lung cancer patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:1318–1325. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-03-0156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothenberg ML, Moore MJ, Cripps MC, Andersen JS, Portenoy RK, Burris HA, III, et al. A phase II trial of gemcitabine in patients with 5-FU-refractory pancreas cancer. Ann Oncol. 1996;7:347–353. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.annonc.a010600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saif MW. New developments in the treatment of pancreatic cancer. JOP; Highlights from the ‘44th ASCO Annual Meeting’; Chicago, IL, USA. May 30–June 3, 2008; 2008. pp. 391–397. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato N, Maehara N, Goggins M. Gene expression profiling of tumor-stromal interactions between pancreatic cancer cells and stromal fibroblasts. Cancer Res. 2004;64:6950–6956. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sener SF, Fremgen A, Menck HR, Winchester DP. Pancreatic cancer: a report of treatment and survival trends for 100,313 patients diagnosed from 1985–1995, using the National Cancer Database. J Am Coll Surg. 1999;189:1–7. doi: 10.1016/s1072-7515(99)00075-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirota Y, Stoehlmacher J, Brabender J, Xiong YP, Uetake H, Danenberg KD, et al. ERCC1 and thymidylate synthase mRNA levels predict survival for colorectal cancer patients receiving combination oxaliplatin and fluorouracil chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:4298–4304. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.23.4298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon G, Sharma A, Li X, Hazelton T, Walsh F, Williams C, et al. Feasibility and efficacy of molecular analysis-directed individualized therapy in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:2741–2746. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.2099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staley CA, Lee JE, Cleary KR, Abbruzzese JL, Fenoglio CJ, Rich TA, et al. Preoperative chemoradiation, pancreaticoduodenectomy, and intraoperative radiation therapy for adenocarcinoma of the pancreatic head. Am J Surg. 1996;171:118–124. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9610(99)80085-3. discussion 124–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueno H, Okusaka T, Ikeda M, Takezako Y, Morizane C. An early phase II study of S-1 in patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer. Oncology. 2005;68:171–178. doi: 10.1159/000086771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright JA, Chan AK, Choy BK, Hurta RA, McClarty GA, Tagger AY. Regulation and drug resistance mechanisms of mammalian ribonucleotide reductase, and the significance to DNA synthesis. Biochem Cell Biol. 1990;68:1364–1371. doi: 10.1139/o90-199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng Z, Chen T, Li X, Haura E, Sharma A, Bepler G. DNA synthesis and repair genes RRM1 and ERCC1 in lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:800–808. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa065411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.