Abstract

Background

Prostate cancer is the most common cancer in older men in the United States (USA) and Western Europe. Androgen deprivation (AD) constitutes, in most cases, the first-line of treatment for these cases. The negative impact of CAD in quality of life, secondary to the adverse events of sustained hormone deprivation, plus the costs of this therapy, motivated the intermittent treatment approach. The objective of this study is to to perform a systematic review and meta-analysis of all randomized controlled trials that compared the efficacy and adverse events profile of intermittent versus continuous androgen deprivation for locally advanced, recurrent or metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer.

Methods

Several databases were searched, including MEDLINE, EMBASE, LILACS, and CENTRAL. The endpoints were overall survival (OS), cancer-specific survival (CSS), time to progression (TTP) and adverse events. We performed a meta-analysis (MA) of the published data. The results were expressed as Hazard Ratio (HR) or Risk Ratio (RR), with their corresponding 95% Confidence Intervals (CI 95%).

Results

The final analysis included 13 trials comprising 6,419 patients with hormone-sensitive prostate cancer. TTP was similar in patients who received intermittent androgen deprivation (IAD) or continuous androgen deprivation (CAD) (fixed effect: HR = 1.04; CI 95% = 0.96 to 1.14; p = 0.3). OS and CSS were also similar in patients treated with IAD or CAD (OS: fixed effect: HR = 1.02; CI 95% = 0.95 to 1.09; p = 0.56 and CSS: fixed effect: HR = 1.06; CI 95% = 0.96 to 1.18; p = 0.26).

Conclusion

Overall survival was similar between IAD and CAD in patients with locally advanced, recurrent or metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer. Data on CSS are weak and the benefits of IAD on this outcome remain uncertain. Impact in QoL was similar for both groups, however, sexual activity scores were higher and the incidence of hot flushes was lower in patients treated with IAD.

Keywords: Androgen deprivation, Prostate cancer, Systematic review

Background

Prostate cancer is the most common cancer in older men in the United Kingdom (UK), United States (USA) and Western Europe [1]. Despite its high incidence, the disease is often responsive to treatment even when metastatic and may be cured when localized. In patients with locally advanced tumors, recurrent or metastatic, the goals of therapy are to prolong survival, slow the progression of disease and preserve the quality of life [2].

Androgen deprivation (AD) constitutes, in most cases, the first-line of treatment for these cases. However, the deleterious effects of continuous androgen deprivation (CAD) are widely known and are related to some degree of deterioration in the quality of life. The most frequent symptoms resulting from AD include sexual dysfunction, fatigue, anemia, reduced muscle and bone mass, depression, abnormal lipid metabolism, cognitive dysfunction and development or worsening of metabolic syndrome [3,4]. The negative impact of CAD in quality of life, secondary to the adverse events of sustained hormone deprivation, plus the costs of this therapy, motivated the intermittent treatment approach.

In recent years, non-randomized studies (most of them with heterogeneous criteria for selection and clinical assessment) were performed to confirm the effectiveness of intermittent androgen deprivation (IAD) in patients with prostate cancer. Two systematic reviews [5,6] previously published analyzed the results of these non-randomized studies and the authors suggested that the best candidates for intermittent androgen deprivation are patients with biochemical progression after prostatectomy or radiation, with no evidence of metastases and with mildly aggressive tumors. On the other hand, patients with large tumor volumes, positive lymph nodes and bone metastases, PSA >100 ng/ml or short PSA doubling time, would be best treated with continuous deprivation.

Irrespective of official guideline recommendations, IAD is a treatment option used worldwide by both urologists and oncologists even outside of clinical trials [5].

The 2008 UK National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) recommends that IAD may be offered to men with metastatic prostate cancer providing they are informed that there is no long-term evidence of its effectiveness [7].

The results of some randomized controlled trials (RCT) were statistically inconclusive [8] or controversial. Crook et al. [9,10] analyzed IAD versus CAD for prostate-specific antigen (PSA) elevation after radiotherapy, assessing overall survival (OS) in a non-inferiority randomized trial with 1,386. The results demonstrated that IAD was non-inferior to CAD in regard to OS (8.8 years versus 9.1 years respectively - hazard ratio for death, 1.02; CI 95% 0.86 to 1.21, p for non-inferiority = 0.009), besides providing potential benefits in aspects such as physical function, fatigue, urinary problems, hot flashes, libido, and erectile function. Furthermore, the authors pointed that time to hormone resistance was statistically significantly improved on the IAD arm (HR 0.80, 95% CI 0.67-0.98; p = 0.024).

Regarding time-to-progression or castration-resistant disease, however, Crook et al. [9,10] showed better results in favor of CAD, while the results of Salonen et al. [11,12] were favorable to IAD. Such contradictory results make it difficult to emit a strong scientific-based recommendation for or against IAD.

The objective of this study is to analyze all published randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that compared the efficacy and adverse events profile of IAD versus CAD for locally advanced, recurrent or metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer.

Methods

Study selection criteria

Types of studies

We included RCTs with parallel design that compared the use of intermittent versus continuous androgen deprivation.

Types of participants

The selected studies included patients with locally advanced, recurrent or metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer.

Search strategy for identification of studies

A wide search on the main computerized databases was conducted, including EMBASE, LILACS, MEDLINE, SCI, CENTRAL, The National Cancer Institute Clinical Trials service and The Clinical Trials Register of Trials Central. In addition, the abstracts published in the proceedings of the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO), American Society of Radiation Oncology (ASTRO), the European Society of Medical Oncology (ESMO), Society of Urologic Oncology (SUO), European Society for Radiotherapy and Oncology (ESTRO) and American Urological Association (AUA) were also searched.

For MEDLINE, we used the search strategy methodology for randomized controlled trials [13] recommended by the Cochrane Collaboration [14]. For EMBASE, adaptations of this same strategy were used [13], and for LILACS, we used the search strategy methodology reported by Castro et al. [15]. An additional search on the SCI database was also performed to retrieve articles that were cited on the included studies. The specific terms relevant to this review were added to the overall search strategy methodology for each database.

The overall search strategy was: #1: prostate cancer, #2: intermittent, #3: androgen deprivation and #4: Randomized Controlled Trial. Searches in electronic databases combined the terms: #1 AND #2 AND #3 AND #4.

The search was not limited by date, language or specific outcome.

Critical evaluation of the selected studies

All the references retrieved by the search strategies had their title and abstract evaluated by two of the researchers. Every reference with the least indication of fulfilling the inclusion criteria was listed as pre-selected. The complete article of all pre-selected references was retrieved. The articles were analyzed by two different researchers and included or excluded according to the previously reported criteria. The excluded trials and the reason of their exclusion are listed in this article. Data was extracted from all the included trials.

Details regarding the main methodology characteristics empirically linked to bias [16] were extracted with the methodological validity of each selected trial assessed by two reviewers (T.E.A.B and O.C). Particular attention was given to some items such as: the generation and concealment of the sequence of randomization; blinding; application of intention-to-treat analysis; sample size pre-definition; loss of follow-up description; adverse events reports; if the trial was performed in multiple center or a single center; and the sponsorship.

Data extraction

Two independent reviewers extracted the data. The name of the first author and year of publication were used to identify the study. All data were extracted directly from the text or calculated from the available information when necessary. The data of all trials were based on the intention-to-treat principle, so they compared all patients allocated in one treatment with all those allocated in the other.

The primary endpoint was overall survival (OS). The OS was calculated from the date of randomization to the date of death, with data censored at the last known date that the patient was alive.

Other clinical outcomes were also evaluated:

• Cancer-specific survival (CSS): the cancer-specific survival was calculated from the date of randomization to the date of death from prostate cancer or a complication of cancer treatment;

• Time to progression (TTP) or castration-resistant disease: defined as increases in PSA level or evidence of new clinical disease while the patient was receiving androgen-deprivation therapy and testosterone was at castration level;

• Differences in the quality of life (QoL): hot flashes, desire for sexual activity, urinary symptoms, depression and gynecomastia;

• Died because of cardiovascular events.

Analysis and presentation of results

Data analysis was performed using the Review Manager 5.1.2 statistical package (Cochrane Collaboration Software) [17].

Dichotomous clinical outcomes are reported as Risk Ratio (RR) and survival data as Hazard Ratio (HR) [18]. The corresponding 95% confidence interval (CI 95%) was calculated, considering P values less than 5% (p < 0.05). Statistic Heterogeneity was calculated through I2 method (25% was considered low-level heterogeneity, 25-50% moderate-level heterogeneity and >50% high-level heterogeneity) [19,20].

To estimate the absolute gain in OS, cancer-specific survival and time to progression, the meta-analytic survival curves were calculated as suggested by Parmar et al. [18]. A pooled estimate of the HR was computed by a fixed-effect model according to the inverse-variance method [21]. Thus, for effectiveness or adverse events, an HR or RR >1 favors the standard arm (continuous treatment) whereas an HR or RR <1 favors the intermittent treatment.

If statistic heterogeneity was found in the meta-analysis, an additional analysis was performed, using the random-effects model described by DerSimonian and Laird [22] that provides a more conservative analysis.

To assess the possibility of publication bias, the funnel plot test described by Egger et al. was performed [23]. When the pooled results were significant, the number of patients needed to treat (NNT or NNH) to cause or to prevent one event was calculated by pooling absolute risk differences in the trials included in this meta-analysis [24-26]. For all analyses, a forest plot was generated to display the results.

Results

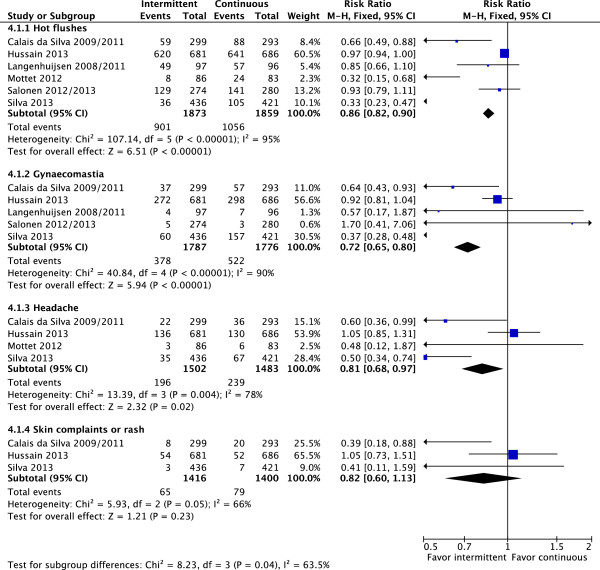

The diagram represents the flow of identification and inclusion of trials, as recommended by the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses) statement [27] (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Trial selection flow.

Overall, 73 references were identified and screened.

Twenty-nine studies were selected and retrieved for full-text analysis. Of these studies, 16 were excluded for various reasons described on Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of excluded studies

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Klotz [28] |

Not a randomized trial |

| Goldenberg [29] |

Not a randomized trial |

| Higano [30] |

Not a randomized trial |

| Oliver [31] |

Not a randomized trial |

| Bierkens [32] |

Not a randomized trial |

| Grossfeld [33] |

Not a randomized trial |

| Calais da Silva Jr F [34] |

Analysis of pooled data from 2 trials |

| De Conti P [35] |

Systematic Review |

| Loblaw [36] |

Practice guideline |

| Heidenreich [37] |

Practice guideline |

| Heidenreich [38] |

Not a randomized trial |

| Heidenreich [39] |

Practice guideline |

| Buchan [40] |

Not a randomized trial |

| Keizman [41] |

Not a randomized trial |

| Gruca [42] |

Literature review |

| Organ [43] | Castration-resistant prostate cancer |

Characteristics of included studies

Thirteen randomized trials comprising 6,419 patients with hormone-sensitive prostate cancer were included in this analysis. More than 2,800 patients (44%) had metastatic disease and 1,595 patients (25%) had PSA progression after prostatectomy (n = 209) or radiotherapy (n = 1,386). The number of patients in these trials varied from 43 to 1,535, but only 5 involved >500 patients. The average age of patients was 70 years.

PSA was measured every 2-3 months in most studies [1,9-12,44-54]. Only in one study [8,55] PSA levels were measured monthly.

Full details of trial design are not available for all studies: several reports are available only in abstract form [48,49,56].

The criteria for stopping and re-start of therapy in groups treated with IAD were similar, however not uniform (Table 2). Average follow-up time in these studies was of >2 years. The induction period varied, but most patients used IAD for a period of approximately 3-6 months (Table 3).

Table 2.

Characteristics of randomized included studies

|

Study |

Patients with PCa |

N (ITT) |

PSA levels (ng/ml) |

Primary endpoint |

Median follow-up (years) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cease treatment | Restarted treatment | |||||

| Crook 2012 [9,10](CIC-CTG PR.7 Trial) |

Recurrent (after radiotherapy) |

1386 |

<4 and not > 1 above the previous recorded value as monitored |

>10 |

OS |

6.9 |

| Calais da Silva 2009/2011 [44,45](SEUG Trial) |

Locally advanced, metastatic |

626 |

<4 ≤80% initial level |

≥10 (symptomatic) or ≥20 (asymptomatic) ≥20% above nadir value |

TTP |

4.75 |

| Hussain 2013 [8,55](SWOG 9346 Trial) |

Metastatic |

1535 |

≤4 |

≥20 or ≥10 or symptoms |

OS |

9.2 |

| Salonen 2012/2013 [11,12](FinnProstate Trial VII) |

Locally advanced, metastatic or recurrent (after radiotherapy or prostatectomy) |

554 |

<10 >50% (PSA < 20) |

PSA or CP |

TTP |

5.4 |

| Tunn 2012 [1,46,47](EC507 Trial) |

Recurrent (after prostatectomy) |

201 |

≤0.5 |

≥3 or when was CP |

Time to androgen-independent |

2.4 |

| De Leval 2002 [51] |

Locally advanced, metastatic or recurrent (after prostatectomy) |

68 |

≤4 |

≥10 |

Time to androgen- independent |

2.7 |

| Langenhuijsen 2008/2011 [52,53] (TULP Trial) |

Locally advanced or metastatic |

193 |

<4 |

≥10 (M0) ≥20 (M1) |

TTP |

2.58 |

| Miller 2007 [56] |

Locally advanced or metastatic |

335 |

<4 |

- |

TTP |

NR |

| ≤90% initial level | ||||||

| Mottet 2012 [50](TAP 22 Trial) |

Metastatic and PSA ≥ 20 ng/ml |

173 |

< 4 |

≥10 or CP |

OS |

3.7 |

| Verhagen 2008/2013 [48,49] |

Asymptomatic metastatic |

258 |

Good or moderate response |

PSA or CP |

Quality of life |

NR |

| Hering 2000 [54] |

Metastatic |

43 |

0.4 |

≥10 (initial ≤20) |

TTP and adverse events |

4 |

| ± 50% initial (initial > 20) | ||||||

| Irani 2008 [57] |

Locally advanced or metastatic |

129 |

6 months |

6 months |

Quality of life and TTP |

5 |

| Silva 2013 [58](SEUG 9901 Trial) | Locally advanced or metastatic | 918 | < 4 | ≥20 or CP | OS | 5.5 |

Abbreviations: OS overall survival, TTP time to progression, PCa prostate cancer, PSA prostate-specific antigen, CP clinical progression, NR not reported, ITT intent-to-treat, CP clinical progression.

Table 3.

Treatment regimens in the included studies

| Crook 2012 (CIC-CTG PR.7 Trial)[9,10] |

Intermittent:

induction only (8 mo): LHRHa injections plus a non-steroidal antiandrogen, with the latter continued for a minimum of 4 weeks. |

| |

Continuous:

consisted of a LHRHa plus a non-steroidal antiandrogen, with the latter continued for a minimum of 4 weeks, or orchiectomy. |

| Calais da Silva 2009/2011 (SEUG 9401 Trial)[44,45] |

Intermittent:

induction only (3 mo): CPA 200 mg for 2 weeks followed by monthly depot injections of a LHRHa plus 200 mg of CPA daily. |

|

Continuous:

received an LHRHa plus 200 mg of CPA daily. | |

| Hussain 2013 (SWOG 9346 Trial)[8,55] |

Intermittent:

induction only (7 mo): received LHRHa (goserelin) plus bicalutamide. |

|

Continuous:

LHRHa plus bicalutamide | |

| Salonen 2012/2013 (FinnProstate Study VII)[11,12] |

Intermittent:

induction only (6 mo): goserelin acetate (3.6 mg) SC every 28 days. The CPA was given in 100 mg twice daily during the first 12.5 days to minimize flare reaction. |

|

Continuous:

continued with goserelin acetate or bilateral orchiectomy. | |

| Tunn 2012 (EC507 Trial)[1,46,47] |

Intermittent:

induction only (6 mo): received LHRHa (Leuprorelin acetate 11.25 mg, 3-mo depot, SC or IM) plus CPA 200 mg/day orally was administered for the first 4 weeks to prevent tumor flare. |

|

Continuous:

LHRHa | |

| De Leval 2002 [51] |

Intermittent:

induction only (3-6 mo): flutamide (250 mg, 3 times, daily) for 15 days. This therapy was followed by flutamide and goserelin acetate (3.6 mg, monthly). |

| |

Continuous:

goserelin plus flutamide (250 mg orally every 8 hours) without interruption. |

| Langenhuijsen 2008/2011 (TULP Trial) [52,53] |

Intermittent:

induction only (6 mo): Buserelin depot 6.6 mg, a 2-monthly SC plus nilutamide 300 mg (once a day for the first 4 weeks and 150 mg daily thereafter). |

|

Continuous:

buserelin depot plus nilutamide | |

| Miller 2007 [56] |

Intermittent:

induction only (6 mo): goserelin plus bicalutamide |

|

Continuous:

goserelin plus bicalutamide | |

| Mottet 2012 (TAP 22 Trial)[50] |

Intermittent:

induction only (6 mo): leuprorelin SR 3.75 mg, SC every 28 days and flutamide, one 250 mg tablet, three times daily. |

|

Continuous:

leuprorelin and flutamide continued until disease progression or study end. | |

| Verhagen 2008/2013 [48,49] |

Intermittent:

induction only (3-6 mo): CPA 100 mg three times daily |

|

Continuous:

CPA 100 mg thrice daily. | |

| Hering 2000 [54] |

Intermittent:

induction only (10.5 mo): CPA 200 mg/day orally |

|

Continuous:

CPA 200 mg/day orally | |

| Irani 2008 [57] |

Intermittent:

induction only (6 mo): goserelin 10.8 mg 3-mo depot and flutamide 250 mg three times daily and resumed 6 mo later |

|

Continuous:

goserelin and flutamide 250 mg three times daily continued without interruption | |

| Silva 2013 (SEUG 9901 Trial)[58] |

Intermittent:

induction only (3 mo): CPA 200 mg/d for 2 weeks followed by monthly depot injections of triptoreline plus 200 mg of CPA daily and restarted monotherapy with CPA 300 mg/d in the progression |

| Continuous: CPA 200 mg/d for 2 weeks followed by monthly depot injections of triptoreline plus 200 mg of CPA daily. |

Abbreviations: Mo months, CPA cyproterone acetate, LHRHa luteinizing hormone–releasing hormone agonist, SC subcutaneous, IM intramuscular injection.

Two studies [48,49,54] did not use luteinizing hormone–releasing hormone agonist (LHRHa) or orchiectomy. These studies used cyproterone acetate (CPA) with doses between 300-400 mg/day orally. Overall, goserelin was the most used LHRHa, followed by leuprorelin (Table 3).

Evaluation of OS was the primary endpoint in 4 studies [8-10,50,55,58] and TTP or time to androgen-independent was the primary endpoint in 7 studies [1,11,12,44-47,50-54,56,57] (Table 2). Five studies [1,8-10,44-47,55,58] were designed to evaluate the non-inferiority of IAD compared to CAD (Table 4).

Table 4.

Efficacy analysis in the trials included in the meta-analysis

| Study | Arm | Design of study | Time to progression or time to castration-resistant disease | Cancer-specific survival | Overall survival (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crook 2012 [9,10](CIC-CTG PR.7 Trial) |

CAD |

Non-inferiority |

10 years |

HR: 1.18 (0.90-1.55) |

9.1 years |

| |

IAD |

(HR <1.25) |

9.8 years |

p = 0.24 |

8.8 years |

| |

|

|

HR: 0.80 (0.67-0.98) p = 0.024 |

|

HR: 1.02 (0.86-1.21) for non-inferiority (IAD vs CAD ≥1.25) = 0.009 |

| Calais da Silva 2009/2011 [44,45](SEUG Trial) |

CAD |

Non-inferiority |

HR: 0.81 (0.63-1.05) favoring CAD |

HR: 1.27 (0.98-1.64) |

HR: 0.96 (0.80-1.14) favoring CAD |

| |

IAD |

(<30%) |

|

|

|

| Hussain 2013 [8,55](SWOG 9346 Trial) |

CAD |

Non-inferiority |

NR |

NR |

5.8 years |

| |

IAD |

(HR <1.20) |

|

|

5.1 years |

| |

|

|

|

|

HR: 1.10 (0.97-1.25) |

| Salonen 2012/2013 [11,12] |

CAD |

Compare the efficacy |

30.2 months |

44.3 months |

45.7 months |

|

(FinnProstate Trial VII) |

IAD |

|

34.5 months |

45.2 months |

45.2 months |

| |

|

|

HR: 1.08 (0.90-1.29) favoring IAD |

HR: 1.17 (0.91-1.51) favoring IAD |

HR: 1.15 (0.94 -1.4) favoring IAD |

| Tunn 2012 [1,46,47](EC507 Trial) |

CAD |

Non-inferiority |

16 risk of progression |

NR |

NR |

| |

IAD |

|

37 risk of progression |

|

|

| |

|

|

p = 0.853 |

|

|

| |

|

|

HR: 0.97 (0.68-1.38) & |

|

|

| De Leval 2002 [51] |

CAD |

Compare the efficacy |

14.4 months |

4 (12.1%) deaths |

NR |

| |

IAD |

|

25.7 months |

2 (5.7%) deaths |

|

| |

|

|

HR: 0.57 (0.07-4.64) & |

NS |

|

| |

|

|

|

HR: 0.46 (0.09-2.35) & |

|

| Langenhuijsen 2008/2011 [52,53] |

CAD |

Compare the efficacy |

24.1 months# |

NR |

NS |

| (TULP Trial) |

IAD |

|

18 months |

|

|

| |

|

|

NS |

|

|

| Miller 2007 [56] |

CAD |

Compare the efficacy |

11.5 months |

NR |

53.8 months |

| |

IAD |

|

16.6 months |

|

51.4 months |

| |

|

|

p = 0.1758 |

|

p = 0.658 |

| |

|

|

HR: 0.69 (0.41-1.16)& |

|

HR: 1.04 (0.86-1.28)& |

| Mottet 2012 [50](TAP 22 Trial) |

CAD |

Compare the efficacy |

15.1 months |

NR |

52 months |

| |

IAD |

|

20.7 months |

|

42.2 months |

| |

|

|

p = 0.74 |

|

p = 0.75 |

| |

|

|

HR: 0.88 (0.63-1.4)& |

|

HR: 1.14 (0.74-1.77)& |

| Verhagen 2008/2013 [48,49] |

CAD |

Compare the efficacy |

NS |

NS |

NS |

| |

IAD |

|

|

|

|

| Hering 2000 [54] |

CAD |

Compare the efficacy |

20.1 months |

2 (11.1%) deaths |

NR |

| |

IAD |

|

NR |

2 (8%) deaths |

|

| |

|

|

NS |

NS |

|

| |

|

|

|

HR: 0.70 (0.09-5.44) & |

|

| Irani 2008 [57] |

CAD |

Compare the efficacy |

HR: 1.1 (0.6-1.8) p = 0.3 favoring IAD |

HR: 0.6 (0.2–1.6) p = 0.12 favoring CAD |

HR: 0.6 (0.3–1.3) p = 0.06 favoring CAD |

| |

IAD |

|

|

|

|

| Silva 2013 [58](SEUG 9901 Trial) |

CAD |

Non-inferiority |

HR: 1.16 (0.93-1.47) |

HR: 1.0 (0.76-1.32) |

HR: 0.90 (0.76-1.07) |

| IAD | (HR < 1.20) |

Abbreviations: ITT intention-to-treat, HR Hazard ratios, Mo months, NS not significant, IAD intermittent androgen deprivation, CAD continuous androgen deprivation.

#No hazard ratio or P value reported.

&Calculated the meta-analytic survival curves as suggested by Parmar et al. [18].

More details on the treatment modality, follow-up, number of patients and primary endpoint in the 13 trials included in this analysis are summarized in Tables 2 and 3.

The efficacy analysis was summarized in Table 4.

Meta-analysis

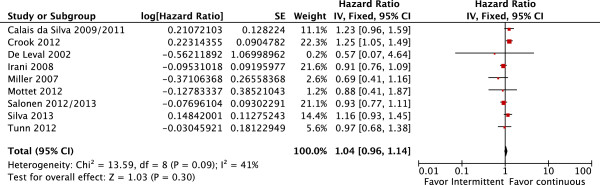

Overall, TTP was similar in patients who received IAD or CAD (fixed effect: HR = 1.04; CI 95% = 0.96 to 1.14; p = 0.3), with high moderate heterogeneity (Chi2 = 13.59, df = 8 [P = 0.09]; I2 = 41%) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Time-to-progression: comparative effect of intermittent versus continuous androgen deprivation in prostate cancer.

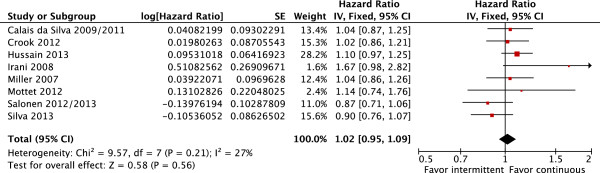

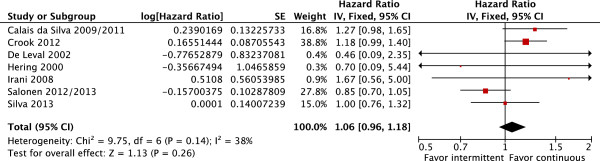

OS and CSS were also similar in patients treated with IAD or CAD (OS: fixed effect: HR = 1.02; CI 95% = 0.95 to 1.09; p = 0.56 with moderate heterogeneity Chi2 = 9.57, df = 7, P = 0.21, I2 = 27% and CSS: fixed effect: HR = 1.06; CI 95% = 0.96 to 1.18; p = 0.26 also with moderate heterogeneity Chi2 = 9.75, df = 6, P = 0.14, I2 = 38% (Figures 3 and 4, respectively).

Figure 3.

Overall survival. Comparative effect of intermittent versus continuous androgen deprivation in prostate cancer.

Figure 4.

Cancer-specific survival. Comparative effect of intermittent versus continuous androgen deprivation in prostate cancer.

In order to explore this heterogeneity, the study by Salonen et al. [11,12] was removed from the survival analysis, since patients treated in the IAD arm had lower levels of baseline PSA than patients on CAD group (IAD: mean PSA 116.0 ± 173.4 ng/ml; CAD: mean PSA 186.3 ± 454.4 ng/ml). Regarding OS, results remain similar between the groups (fixed effect: HR = 1.04; CI 95% = 0.96 to 1.12; p = 0.32) while there was a decrease in heterogeneity (Chi2 = 6.87, df = 5, P = 0.23, I2 = 27%). Furthermore, CSS was favorable to CAD (fixed effect: HR = 1.16; CI 95% = 1.02 to 1.31; p = 0.02; NNT = 6) with no heterogeneity (Chi2 = 3.51, df = 5, P = 0.62, I2 = 0%).

Four studies [8,48-50,54,55] included only patients with metastatic disease (or ≥90% metastatic). In this subgroup of patients, only 1 study [50] reported TTP data and another [54] reported cancer-specific survival data, so a meta-analysis was not feasible. Two studies [8,50,55] reported OS data, which permitted meta-analysis. OS was also similar in patients treated with IAD or CAD (fixed effect: HR = 1.10; CI 95% = 0.98 to 1.24; p = 0.11) with no heterogeneity (Chi2 = 0.02, df = 1, P = 0.88, I2 = 0%).

Two studies [1,9,10,46,47] included only patients with recurrent disease after definitive local therapy (prostatectomy or radiotherapy). In this subgroup, TTP was favorable to patients who received CAD (fixed effect: HR = 1.19; CI 95% = 1.01 to 1.39; p = 0.03), with moderate heterogeneity (Chi2 = 1.57, df = 1 [P = 0.21]; I2 = 36%). However, when the random-effects model analysis was performed, no significant difference was detected (random effects: HR = 1.16, CI95% = 0.92 to 1.45; p = 0.22). It was not possible to perform a meta-analysis for OS and CSS, since only Crook et al. [9,10] reported these data.

One study [58], on re-introduction of treatment in IAD group, used a hormone therapy scheme (cyproterone 300 mg/d) that was different from the one used in the CAD group (LHRHa: triptoreline 11.25 mg plus cyproterone 200 mg/d). When OS analysis was performed without this study, the results remained similar between IAD and CAD (fixed effect: HR = 1.04; CI 95% = 0.97 to 1.12; p = 0.25; with no heterogeneity: Chi2 = 7.08, df = 6, P = 0.31, I2 = 15%).

In most studies [8-10,44,48-50,55] baseline quality-of-life scores were similar in both groups for the majority of items, with no clinically significant differences. Sexual activity scores appeared to be favorable in the IAD group (Table 5).

Table 5.

Significant differences in quality of life (QoL)

| Study | EORTC quality-of-life core questionnaire (QLQ-C30) and the EORTC Prostate Cancer Module |

|---|---|

| Crook 2012 [9,10](CIC-CTG PR.7 Trial) |

Intermittent (better):

hot flashes, desire for sexual activity, and urinary symptoms |

|

Continuous: -

| |

| Calais da Silva 2009/2011 [44,45](SEUG Trial) |

Intermittent (better):

sexual function |

|

Continuous (better):

emotional domain, nausea and vomiting, severity of insomnia | |

| Hussain 2013 [8,55](SWOG 9346 Trial) |

Intermittent (better):

erectile function and mental health at 3 months but not thereafter |

|

Continuous:

- | |

| Salonen 2012/2013 [11,12](FinnProstate Trial VII) |

Intermittent (better):

sexual function |

|

Continuous:

- | |

| Tunn 2012 [1,46,47](EC507 Trial) |

Intermittent:

NR |

|

Continuous:

NR | |

| De Leval 2002 [51] |

Intermittent:

NR |

|

Continuous:

NR | |

| Langenhuijsen 2008/2013 [52,53] (TULP Trial) |

Intermittent:

NS |

|

Continuous:

NS | |

| Miller 2007 [56] |

Intermittent (better):

sexual activity appeared to be favorable in the intermittent |

|

Continuous:

- | |

| Mottet 2012 [50](TAP 22 Trial) |

Intermittent:

NS |

|

Continuous:

NS | |

| Verhagen 2008/2013 [48,49] |

Intermittent (better):

symptom and potency scales |

|

Continuous:

- | |

| Hering 2000 [54] |

Intermittent (better):

erectile function |

|

Continuous:

- | |

| Irani 2008 [57] |

Intermittent (better):

ability to have and maintain an erection. |

|

Continuous:

- | |

| Silva 2013 [58](SEUG 9901 Trial) |

Intermittent (better):

sexual activity |

| Continuous: - |

Abbreviations: EORTC European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer, NS not significant, NR not reported.

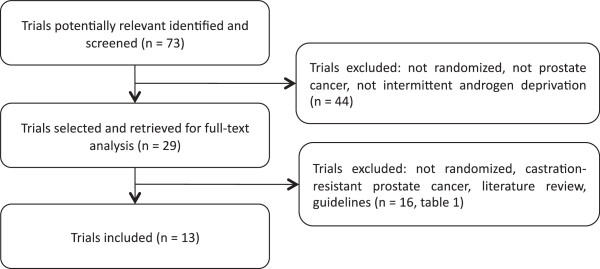

The prevalence of adverse events of androgen deprivation such as hot flushes (fixed effect: RR = 0.86; CI 95% = 0.82 to 0.90; p < 0.00001), gynecomastia (fixed effect: RR = 0.72; CI 95% = 0.65 to 0.80; p < 0.00001) and headache (fixed effect: RR = 0.81; CI 95% = 0.68 to 0.97; p-0.02) were more frequent in patients treated with CAD, with high heterogeneity levels (Figure 5). As planned, a random-effects model analysis was performed to better explore this heterogeneity. In this analysis, with exception of hot flushes (RR = 0.65; CI 95% = 0.45 to 0.95; p = 0.03; NNH = 10), adverse events were similar in both groups (gynecomastia: RR = 0.66; CI 95% = 0.39 to 1.13; p = 0.13 and headache: RR = 0.68; CI 95% = 0.42 to 1.10; p = 0.11).

Figure 5.

Toxicities. Comparative effect of intermittent versus continuous androgen deprivation in prostate cancer.

Mortality secondary to cardiovascular events was report in only 4 studies [9-12,44,45,58]. Results of this analysis were favorable to the group treated with IAD (fixed effect: RR = 0.80; CI 95% = 0.67 to 0.94; p = 0.007; NNH = 33) however with high heterogeneity levels (Chi2 = 6.67, df = 3 [P = 0.08]; I2 = 55%).

According to funnel plot analysis [23] the possibility of publication bias was low for all of the outcomes. When funnel plot shows asymmetry, there is a possibility of bias and despite its limmitations, this method is widely used by authors.

Discussion

Currently, many oncology guidelines do not recommend the use of IAD for patients with metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer [36,59]. But it is important to note that these guidelines date back to 2007. Guidelines from the European Association of Urology (EUA) state that IAD is now widely offered to patients with prostate cancer and should no longer be regarded as investigational [60,61].

Two other meta-analysis published earlier [62,63] showed that both treatments had similar results regarding OS and CSS. Analysis of OS was performed with 4 studies [8-12,44,45,55] in the Niraula et al. meta-analysis [62] and 7 studies [8-12,44,45,50,52,53,55,57] in Tsai et al. [63]. CSS analysis was performed with 3 [9-12,44,45] and 6 studies [8-12,44,45,51,55,57] respectively.

In this present meta-analysis, we included a larger number of studies. When HRs were not directly reported in the original study, they were estimated indirectly by using the reported number of events and the corresponding P value for the log-rank statistics, or by reading survival curves as suggested by Parmar et al. [18]. To reduce reading errors, original survival curves were digitalized and enlarged, and data extraction was based on reading electronic coordinates for each point of interest, as described by DeLaurentiis in another meta-analysis [64].

In the final OS and CSS analyses we included 8 and 7 studies respectively. The induction time of androgen deprivation was, in general, 3-6 months. Two studies were available only in abstract form [48,49,56]. Overall, goserelin was the most used LHRHa, followed by leuprorelin. Only two studies [48,49,53] did not used luteinizing hormone–releasing hormone agonist (LHRHa) or orchiectomy. These studies used cyproterone acetate (CPA).

In this meta-analysis, randomized studies included heterogeneous groups of patients (locally advanced, metastatic or recurrent). It was not possible to perform the proper analysis of subgroups of patients (i.e. by Gleason score, initial PSA levels, minimal or extensive metastatic disease) because results for such sets were not published in the studies. As to overall survival, our results reinforce the equivalent efficacy of CAD and IAD, regardless of previous treatments.

Apropos of CSS, despite the overall analysis demonstrating only a trend towards treatment with CAD, the results must be interpreted with caution. As mentioned before, in one of the studies [11,12] the baseline PSA levels were lower on the IAD arm, suggesting that these patients had less extensive disease. Once this trial was excluded from the analysis, results favored the group treated with CAD; therefore we cannot exclude the possibility that IAD may carry a higher risk of death by cancer.

Recently, a large prospective Danish study, including over 30,000 patients, investigated the relationship between androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) and cardiovascular diseases such as myocardial infarction (MI) and stroke in men with prostate cancer [65]. The authors found that patients treated with medical endocrine therapy had an increased risk for MI and stroke with adjusted HRs of 1.31 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.16-1.49) and 1.19 (95% CI, 1.06-1.35), respectively, compared with nonusers of ADT. However, androgen deprivation secondary to orchiectomy did no increase the risks for MI (HR: 0.90; 95% CI, 0.83-1.29) or stroke (HR: 1.11; 95% CI, 0.90-1.36). Nevertheless, the conclusions might have been affected, by the lack of information on prognostic lifestyles.

In this meta-analysis, mortality secondary to cardiovascular diseases, despite the heterogeneity found and the paucity of studies reporting this outcome, was favorable to the group treated with IAD. This aspect might have influenced the similar results achieved in OS.

In the event of biochemical recurrence after prostatectomy, when androgen deprivation is indicated, the best candidates for IAD are patients who reach PSA values <0.5 ng/mL after the induction time, according to a randomized study that was considered pure (i.e which included only patients with recurrence after prostatectomy) [1,46,47]. For biochemical recurrences after radiotherapy, the best candidates for IAD are patients who reach PSA levels <4 ng/mL after the induction time [9,10]. Only in these situations (recurrence after radiotherapy or prostatectomy), TTP seems to be favorable to patients receiving CAD. In locally advanced and/or metastatic tumors, the best candidates for IAD are patients who reach PSA values <4 ng/mL after induction time.

Although TTP analysis was performed in this meta-analysis, the results should be evaluated with caution since criteria for progression were different among the included studies.

Patients with a lower burden of disease (i.e. less extensive diseases) and without co-morbidities may be the ones achieving most benefits with IAD treatment.

The implementation of guidelines to assess, monitor and reduce known risk factors for cardiovascular disease may influence the results of overall survival in patients treated with CAD.

Regarding quality of life, differences were not clinically significant in most studies. But it was observed that sexual activity scores seemed to be higher in patients treated with IAD, and the incidence of hot flushes was lower.

Furthermore, it is important to note that IAD modality offers an economic benefit with reduction of pharmaceutical costs during “off-therapy” [62]. Economic analysis is not the aim of this investigation. The studies included failed to report the costs of both modalities (intermittent and continuous). Niraula et al. [62], analyzing only drug costs, estimated that the median cost savings with IAD would be 48%. Hering et al. [54], also based only on the average drug costs, demonstrated that the cost of treatment in IAD arm was approximately 50% lower that in the CAD, over 48 months.

Conclusions

Overall survival was similar between IAD and CAD in patients with locally advanced, recurrent or metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer. Data on CSS are weak and the benefits of IAD on this outcome remain uncertain. Impact in QoL was similar for both groups, however, sexual activity scores were higher and the incidence of hot flushes was lower in patients treated with IAD.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

Systematic review and meta-analysis TEAB, OC. Identification of studies, critical evaluation and discussion. RBDR, ACLP, UF, MVS, FFHBT, TEAB. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:

Contributor Information

Tobias Engel Ayer Botrel, Email: tobias.engel@evidencias.com.br.

Otávio Clark, Email: otavio.clark@evidencias.com.br.

Rodolfo Borges dos Reis, Email: rodolfosbusp@uol.com.br.

Antônio Carlos Lima Pompeo, Email: pompeuro@uol.com.br.

Ubirajara Ferreira, Email: ubirafer@uol.com.br.

Marcus Vinicius Sadi, Email: mvsadi@gmail.com.

Francisco Flávio Horta Bretas, Email: fhbretas@yahoo.com.br.

References

- Tunn U. The current status of intermittent androgen deprivation (IAD) therapy for prostate cancer: putting IAD under the spotlight. BJU Int. 2007;99(Suppl 1):19–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2007.06596.x. discussion 3-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Cancer Institute. Prostate Cancer Treatment (PDQ®). General Information About Prostate Cancer. http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/pdq/treatment/prostate. Accessed on 16 December 2013.

- Choong K, Basaria S. Emerging cardiometabolic complications of androgen deprivation therapy. Aging Male. 2010;13(1):1–9. doi: 10.3109/13685530903410625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harle LK, Maggio M, Shahani S, Braga-Basaria M, Basaria S. Endocrine complications of androgen-deprivation therapy in men with prostate cancer. Clin Adv Hematol Oncol. 2006;4(9):687–696. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abrahamsson PA. Potential benefits of intermittent androgen suppression therapy in the treatment of prostate cancer: a systematic review of the literature. Eur Urol. 2010;57(1):49–59. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2009.07.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw GL, Wilson P, Cuzick J, Prowse DM, Goldenberg SL, Spry NA. et al. International study into the use of intermittent hormone therapy in the treatment of carcinoma of the prostate: a meta-analysis of 1446 patients. BJU Int. 2007;99(5):1056–1065. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2007.06770.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Prostate cancer: diagnosis and treatment. February 2008. http://publications.nice.org.uk/prostate-cancer-cg58/guidance#metastatic-prostate-cancer. Accessed on 16 December 2013.

- Hussain M, Tangen CM, Berry DL, Higano CS, Crawford ED, Liu G. et al. Intermittent versus continuous androgen deprivation in prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(14):1314–1325. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1212299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crook JM, O’Callaghan CJ, Duncan G, Dearnaley DP, Higano CS, Horwitz EM. et al. Intermittent androgen suppression for rising PSA level after radiotherapy. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(10):895–903. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1201546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klotz L, O’ Callaghan CJ, Ding K, Dearnaley DP, Higano CS, Horwitz EM. et al. A phase III randomized trial comparing intermittent versus continuous androgen suppression for patients with PSA progression after radical therapy: NCIC CTG PR.7/SWOG JPR.7/CTSU JPR.7/UK Intercontinental Trial CRUKE/01/013. J Clin Oncol. 2011;2011:4514. ASCO Annual Meeting Abstracts Vol 29, No 15_suppl (May 20 Supplement) [Google Scholar]

- Salonen AJ, Taari K, Ala-Opas M, Viitanen J, Lundstedt S, Tammela TL. The FinnProstate Study VII: intermittent versus continuous androgen deprivation in patients with advanced prostate cancer. J Urol. 2012;187(6):2074–2081. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2012.01.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salonen AJ, Taari K, Ala-Opas M, Viitanen J, Lundstedt S, Tammela TL. Advanced prostate cancer treated with intermittent or continuous androgen deprivation in the randomised FinnProstate Study VII: quality of life and adverse effects. Eur Urol. 2013;63(1):111–120. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2012.07.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickersin K, Scherer R, Lefebvre C. Identifying relevant studies for systematic reviews. BMJ. 1994;309(6964):1286–1291. doi: 10.1136/bmj.309.6964.1286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins JPT, Green S. The Cochrane Library, Issue 4, 2006. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2006. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions 4.2.6 [updated September 2006] [Google Scholar]

- Castro AA, Clark OA, Atallah AN. Optimal search strategy for clinical trials in the Latin American and Caribbean Health Science Literature database (LILACS database): update. Sao Paulo Med J. 1999;117(3):138–139. doi: 10.1590/s1516-31801999000300011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egger M, Smith GD, Altman D. Systematic Reviews in Health Care. London: BMJ Books; 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Review Manager (RevMan) [Computer program]. Version 5.1. Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Parmar MK, Torri V, Stewart L. Extracting summary statistics to perform meta-analyses of the published literature for survival endpoints. Stat Med. 1998;17(24):2815–2834. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0258(19981230)17:24<2815::AID-SIM110>3.0.CO;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327(7414):557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang K, Wang YJ, Chen XR, Chen HN. Effectiveness and safety of bevacizumab for unresectable non-small-cell lung cancer: a meta-analysis. Clin Drug Investig. 2010;30(4):229–241. doi: 10.2165/11532260-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deeks JJHJ, Altman DG. In: Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of In- terventions (ed 4.2.6 [updated September 2006]) Higgins JP, Green S, editor. Chichester, United Kingdom: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2006. Analysing and presenting results. [Google Scholar]

- DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7(3):177–188. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315(7109):629–634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McQuay HJ, Moore RA. Using numerical results from systematic reviews in clinical practice. Ann Intern Med. 1997;126(9):712–720. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-126-9-199705010-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smeeth L, Haines A, Ebrahim S. Numbers needed to treat derived from meta-analyses–sometimes informative, usually misleading. BMJ. 1999;318(7197):1548–1551. doi: 10.1136/bmj.318.7197.1548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altman DG, Deeks JJ. Meta-analysis, Simpson’s paradox, and the number needed to treat. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2002;2:3. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-2-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gotzsche PC, Ioannidis JP. et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(4):W65–W94. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klotz LH, Herr HW, Morse MJ, Whitmore WF Jr. Intermittent endocrine therapy for advanced prostate cancer. Cancer. 1986;58(11):2546–2550. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19861201)58:11<2546::AID-CNCR2820581131>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldenberg SL, Bruchovsky N, Gleave ME, Sullivan LD, Akakura K. Intermittent androgen suppression in the treatment of prostate cancer: a preliminary report. Urology. 1995;45(5):839–844. doi: 10.1016/S0090-4295(99)80092-2. discussion 44-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higano CS, Ellis W, Russell K, Lange PH. Intermittent androgen suppression with leuprolide and flutamide for prostate cancer: a pilot study. Urology. 1996;48(5):800–804. doi: 10.1016/S0090-4295(96)00381-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver RT, Williams G, Paris AM, Blandy JP. Intermittent androgen deprivation after PSA-complete response as a strategy to reduce induction of hormone-resistant prostate cancer. Urology. 1997;49(1):79–82. doi: 10.1016/S0090-4295(96)00373-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bierkens AF, Hendrikx AJ, De La Rosette JJ, Stultiens GN, Beerlage HP, Arends AJ. et al. Treatment of mid- and lower ureteric calculi: extracorporeal shock-wave lithotripsy vs laser ureteroscopy. A comparison of costs, morbidity and effectiveness. Br J Urol. 1998;81(1):31–35. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.1998.00510.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossfeld GD, Small EJ, Carroll PR. Intermittent androgen deprivation for clinically localized prostate cancer: initial experience. Urology. 1998;51(1):137–144. doi: 10.1016/S0090-4295(97)00488-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- da Silva Jr F C, Calais Da Silva F, Brausi M, Goncalves F, Kliment J, Queimadelos A, Pooled Analysis of two protocols of intermittent hormonal therapy in advanced prostatic cancer. : AUA 2013 Annual Meeting; p. 777. [Google Scholar]

- De Conti P, Atallah Alvaro N, Arruda Homero O, Soares Bernardo GO, El Dib Regina P, Wilt Timothy J. Intermittent versus continuous androgen suppression for prostatic cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007. Available from: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD005009.pub2/abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Loblaw DA, Virgo KS, Nam R, Somerfield MR, Ben-Josef E, Mendelson DS. et al. Initial hormonal management of androgen-sensitive metastatic, recurrent, or progressive prostate cancer: 2006 update of an American Society of Clinical Oncology practice guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(12):1596–1605. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.10.1949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heidenreich A, Aus G, Bolla M, Joniau S, Matveev VB, Schmid HP. et al. EAU guidelines on prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 2008;53(1):68–80. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2007.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heidenreich A, Pfister D, Ohlmann CH, Engelmann UH. Androgen deprivation for advanced prostate cancer. Urologe A. 2008;47(3):270–283. doi: 10.1007/s00120-008-1636-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heidenreich A, Aus G, Bolla M, Joniau S, Matveev VB, Schmid HP. et al. EAU guidelines on prostate cancer. Actas Urol Esp. 2009;33(2):113–126. doi: 10.1016/S0210-4806(09)74110-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchan NC, Goldenberg SL. Intermittent versus continuous androgen suppression therapy: do we have consensus yet? Curr Oncol. 2010;17(Suppl 2):S45–S48. doi: 10.3747/co.v17i0.711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keizman D, Carducci MA. Intermittent androgen deprivation–questions remain. Nat Rev Urol. 2009;6(8):412–414. doi: 10.1038/nrurol.2009.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruca D, Bacher P, Tunn U. Safety and tolerability of intermittent androgen deprivation therapy: a literature review. Int J Urol. 2012;19(7):614–625. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2042.2012.03001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Organ M, Wood L, Wilke D, Skedgel C, Cheng T, North S. et al. Intermittent LHRH therapy in the management of castrate-resistant prostate cancer (CRPCa): results of a multi-institutional randomized prospective clinical trial. Am J Clin Oncol. 2013;36(6):601–605. doi: 10.1097/COC.0b013e31825d5664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- da Silva FE C, Bono AV, Whelan P, Brausi M, Marques Queimadelos A, Martin JA. et al. Intermittent androgen deprivation for locally advanced and metastatic prostate cancer: results from a randomised phase 3 study of the South European Uroncological Group. Eur Urol. 2009;55(6):1269–1277. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2009.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- da Silva FM C, da SIlva F C, Bono A, Whelan P, Brausi M, Queimadelos A. et al. Phase III study of intermittent MAB vs continuos MAB. J Urol. 2011;185(4):e288. April 2011, AUA 2011 abstract 716. [Google Scholar]

- Tunn U, Kurek R, Keinle E. et al. Intermittent is as effective as continuous androgen deprivation in patients with PSA relapse after radical prostatectomy. J Urol. 2004;171:384. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000102933.25905.08. Abstract 1458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tunn UW, Canepa G, Kochanowsky A, Kienle E. Testosterone recovery in the off-treatment time in prostate cancer patients undergoing intermittent androgen deprivation therapy. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2012;15(3):296–302. doi: 10.1038/pcan.2012.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verhagen PCMS, Wissenburg LD, Wildhagen MF, Quality of life effects of intermittent and continuous hormonal therapy by cyproterone acetate (CPA) for metastatic prostate cancer [abstract 541] Milan, Italy: Presented at: 23rd Annual Congress of the European Association of Urology; March 26–29, 2008; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Verhagen PCMS, Wildhagen MF, Verkerk A, Bolle WABM. et al. Intermittent versus continuous cyproterone acetate in bone metastatic prostate cancer: Results of a randomized trial. Eur Urol. 2013;12:e680. doi: 10.1016/S1569-9056(13)61162-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mottet N, Van Damme J, Loulidi S, Russel C, Leitenberger A, Wolff JM. Intermittent hormonal therapy in the treatment of metastatic prostate cancer: a randomized trial. BJU Int. 2012;110(9):1262–1269. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2012.11120.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Leval J, Boca P, Yousef E, Nicolas H, Jeukenne M, Seidel L. et al. Intermittent versus continuous total androgen blockade in the treatment of patients with advanced hormone-naive prostate cancer: results of a prospective randomized multicenter trial. Clin Prostate Cancer. 2002;1(3):163–171. doi: 10.3816/CGC.2002.n.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langenhuijsen JF, Badhauser D, Schaaf B, Kiemeney LA, Witjes JA, Mulders PF. Continuous vs. intermittent androgen deprivation therapy for metastatic prostate cancer. Urol Oncol. 2011;9 doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2011.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langenhuijsen JF, Schasfoort EMC, Heathcote P, Intermittent androgen suppression in patients with advanced prostate cancer: an update of the TULP survival data [abstract 538] Milan, Italy: Presented at: 23rd Annual Congress of the European Association of Urology; March 26–29, 2008; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Hering F, Rodrigues PRT, Lipay MA, Nesrallah L, Srougi M. Metastatic adenocarcinoma of the prostate: comparison between continuous and intermittent hormonal treatment. Braz J Urol. 2000;26:276–282. [Google Scholar]

- Hussain M, Tangen CM, Higano C, Schelhammer PF, Faulkner J, Crawford ED. et al. Absolute prostate-specific antigen value after androgen deprivation is a strong independent predictor of survival in new metastatic prostate cancer: data from Southwest Oncology Group Trial 9346 (INT-0162) J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(24):3984–3990. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.4246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller K, Steiner U, Lingnau A, Randomised prospective study of intermittent versus continuous androgen suppression in advanced prostate cancer [abstract 5105] Chicago, IL, USA: Presented at: American Society of Clinical Oncology; June 1–5; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Irani J, Celhay O, Hubert J, Bladou F, Ragni E, Trape G. et al. Continuous versus six months a year maximal androgen blockade in the management of prostate cancer: a randomised study. Eur Urol. 2008;54(2):382–391. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2008.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva FC, Silva FM, Goncalves F, Santos A, Kliment J, Whelan P, Locally advanced and metastatic prostate cancer treated with intermittent androgen monotherapy or maximal androgen blockade: results from a randomised phase 3 study by the south European uroncological group. Eur Urol. 2013. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Prostate cancer. Guideline for the management of clinically localized prostate cancer. 2007. update. American Urological Association. Web site. http://www.auanet.org/content/guidelines-and-quality-care/clinical-guidelines/main-reports/proscan07/content.pdf.

- Heidenreich A, Bastian PJ, Bellmunt J, Guidelines on prostate cancer. Eur Association Urol. Web site http://wwwuroweborg/gls/pdf/08%20Prostate%20Cancer_LR%20March%2013th%202012pdf.

- Sciarra A, Abrahamsson PA, Brausi M, Galsky M, Mottet N, Sartor O. et al. Intermittent androgen-deprivation therapy in prostate cancer: a critical review focused on phase 3 trials. Eur Urol. 2013;64(5):722–730. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2013.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niraula S, Le LW, Tannock IF. Treatment of prostate cancer with intermittent versus continuous androgen deprivation: a systematic review of randomized trials. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(16):2029–2036. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.46.5492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai HT, Penson DF, Makambi KH, Lynch JH, Van Den Eeden SK, Potosky AL. Efficacy of intermittent androgen deprivation therapy vs conventional continuous androgen deprivation therapy for advanced prostate cancer: a meta-analysis. Urology. 2013;82(2):327–334. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2013.01.078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Laurentiis M, Cancello G, D’Agostino D, Giuliano M, Giordano A, Montagna E. et al. Taxane-based combinations as adjuvant chemotherapy of early breast cancer: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(1):44–53. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.11.3787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jespersen CG, Norgaard M, Borre M. Androgen-deprivation therapy in treatment of prostate cancer and risk of myocardial infarction and stroke: a nationwide Danish population-based cohort study. Eur Urol. 2013. [DOI] [PubMed]