Abstract

Store-operated calcium (Ca2+) entry is the process by which molecules located on the endo/sarcoplasmic reticulum (ER/SR) respond to decreased luminal Ca2+ levels by signaling Ca2+ release activated Ca2+ channels (CRAC) channels to open on the plasma membrane (PM). This activation of PM CRAC channels provides a sustained cytosolic Ca2+ elevation associated with myriad physiological processes. The identities of the molecules which mediate SOCE include stromal interaction molecules (STIMs), functioning as the ER/SR luminal Ca2+ sensors, and Orai proteins, forming the PM CRAC channels. This review examines the current available high-resolution structural information on these CRAC molecular components with particular focus on the solution structures of the luminal STIM Ca2+ sensing domains, the crystal structures of cytosolic STIM fragments, a closed Orai hexameric crystal structure and a structure of an Orai1 N-terminal fragment in complex with calmodulin. The accessible structural data are discussed in terms of potential mechanisms of action and cohesiveness with functional observations.

Keywords: Orai channel proteins, calcium release activated calcium, calmodulin, store operated calcium entry, stromal interaction molecules

Introduction

Spatio-temporal changes in cytosolic calcium (Ca2+) levels drive a plethora of signaling events in eukaryotic cells that mediate diverse physiological and pathophysiological processes including apoptosis, fertilization, the immune response and transcription, to name a few.1-3 Large differences in intracellular compartmentalized Ca2+ levels can induce local transient changes in cytosolic Ca2+ concentrations. For example, the ER lumen maintains basal Ca2+ levels in the ~sub-mM concentration range, compared with the cytosol which generally keeps basal Ca2+ at ~sub-μM levels.4 This steep concentration gradient allows for passive movement of Ca2+ from the ER lumen to the cytosol at a minimal energetic cost through, for instance, inositol 1,4,5-trisphospate receptor (Ins[1,4,5]P3R) Ca2+ release channels on the ER. Ins(1,4,5)P3R channels open after binding the small second messenger inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (Ins[1,4,5]P3), produced by the catalytic conversion of phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PtdIns[4,5]P2) into Ins(1,4,5)P3 and diacylglycerol by phospholipase C after agonist-induced G-protein coupled receptor activation (reviewed in ref. 5). It is imperative that depletion of Ca2+ from the ER does not detrimentally effect vital luminal processes such as protein chaperone function6; hence, Ins(1,4,5)P3Rs have evolved a bell-shaped cytosolic Ca2+ dependent channel activity, where open probability is highly suppressed at low (i.e., < 10 nM) as well as high cytosolic Ca2+ concentrations (i.e., > 3 μM) and is maximal at ~100 nM – 1 μM.7,8

The Ca2+ released from the ER lumen only transiently increases cytosolic Ca2+ levels as pump, exchanger and buffer proteins quickly sequester and move the Ca2+ into different compartments and organelles such as the mitochondria, golgi and extracellular space. However, some physiological signals require longer term cytosolic Ca2+ increases such as T-cell activation that is dependent on transcriptional regulation.4,9,10 Eukaryotes have evolved the process of store operated Ca2+ entry (SOCE), which is intimately linked to agonist-induced ER stored Ca2+ depletion, to deliver sustained augmentation of cytosolic Ca2+ levels. SOCE occurs after ER Ca2+ store depletion; further, the reduction in luminal Ca2+ signals highly Ca2+ selective channels on the plasma membrane (PM) to open which elevate Ca2+ levels through the passive movement of Ca2+ down the steep concentration gradient from the virtually inexhaustible supply of the extracellular space (i.e., > 1 mM) to the cytosol (i.e., < 1 μM).11-13 SOCE-mediated increases in cytosolic Ca2+ not only signal various physiological processes, but also provide Ca2+ for the repletion of luminal Ca2+ by active pumping through sarco/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATPases (SERCA) located on the ER.

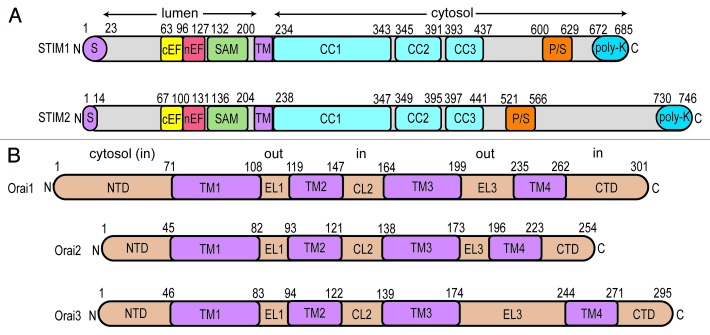

The molecular players that choreograph SOCE include the ER/SR-resident stromal interaction molecules (STIMs)14-16 and the Orai plasma membrane Ca2+ channels.17-21 STIMs are single pass, type I transmembrane (TM) proteins that sense changes in ER luminal Ca2+ levels via communicative interactions between EF-hand and sterile α motif (SAM) domains, conserved from lower to higher eukaryotes (Fig. 1A).16,22-25 This sensory luminal domain machinery is separated from 3 conserved cytosolic coiled-coil (CC) domains (i.e., CC1, CC2, and CC3) by an ~20 amino acid TM domain (Fig. 1A). The cytosolic STIM domains undergo a structural reorganization after luminal depletion,26-29 dependent on the allostery and intermolecular interactions of the Ca2+ sensing EF-hand and SAM domains.30-33 This structural change permits STIMs to physically couple to Orai subunits at ER-PM junctions, meditating stoichiometric channel assembly as well as gating of these PM Ca2+ release activated Ca2+ (CRAC) channels. The Orai family of proteins which constitute CRAC channels are 4 TM spanning proteins with cytosol-oriented N- and C-terminal domains (Fig. 1B) (reviewed in ref. 34). STIM coupling to both N- and C-terminal domains is implicated in recruitment and gating of the channel.35-40 Orai CRAC channels assemble with the TM1 segments constituting the central pore17,20,41-45 of a tetrameric46-50 or hexameric architecture.41,51

Figure 1. Domain architecture of human STIM and Orai proteins. (A) STIM1 and STIM2 domain composition. STIM proteins are targeted to the SR/ER through signal sequences (S; purple). STIM proteins contain a canonical Ca2+ binding EF-hand (cEF; yellow), non-canonical EF-hand (nEF; red) and SAM domain in the lumen (green). A single pass TM (purple) section separates the luminal domains from the cytosolic CC domains (CC1, CC2, CC3; cyan). Pro/Ser (P/S; orange) and poly-Lys-rich (poly-K; blue) regions are found in the non-conserved cytosolic segments of the proteins. (B) Orai1, Orai2 and Orai3 domain composition. The cytosolic N-terminal domain (NTD), extracellular loop1 (EL1), cytosolic loop 2 (CL2), extracellular loop3 (EL3) and cytosolic C-terminal domain (CTD) are colored beige while the transmembrane TM1, TM2, TM3 and TM4 domains are purple. In (A and B), residue ranges defining the domain boundaries are indicated above the linear depiction.

Recent structural information on the CRAC channel components has provided a wealth of information on the molecular basis of channel regulation. Structures of the EF-hand together with the SAM domain (EF-SAM) have improved our understanding of how the luminal STIM region senses changes in Ca2+ levels; further, high resolution data on the conserved cytosolic domains has increased our comprehension of the supercoiling events that play a role in mediating the STIM quiescent and active conformations. The elucidation of an Orai channel structure has revealed atomic features, vital for assembly of the channel as well as permeation and selectivity of Ca2+ through the TM1-constituted pore. Further, a structure of the ubiquitous and cytosolic Ca2+ sensor/regulator calmodulin (CaM) in complex with the Orai1 N-terminal domain has exposed a mechanism for negative channel regulation. This review focuses on the structural details of the aforementioned high resolution data and discusses the implications for CRAC channel regulation and function.

STIM EF-SAM Structure and Function

Vertebrates encode 2 STIM isoforms, and although STIM1 and STIM2 are ubiquitously expressed in mammalian tissues, STIM2 is more enriched in neuronal and brain cells compared with STIM1.24,52 Nonetheless, STIM1 appears to play a dominant role in regulating the ON/OFF capacity of CRAC channels,14,15 whereas STIM2 plays a prevailing role in basal intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis.53,54 At basal ER Ca2+ levels (i.e., ~400 μM), the majority of STIM1 is in a quiescent state; on the other hand, a considerable fraction of STIM2 is in an activated state, coupling to and opening PM CRAC channels that contribute to the maintenance of resting intracellular Ca2+ levels.53 Upon ER Ca2+ depletion, a large fraction of STIM1 molecules become activated compared with the more modest level of remaining STIM2 activation. This difference in Ca2+ sensitivity is partly attributable to distinctions in Ca2+ binding properties of STIM1 compared with STIM2. In vitro Ca2+ binding experiments have demonstrated that isolated and purified STIM1 EF-SAM domains bind Ca2+ with an equilibrium dissociation constant (Kd) of ~400 μM,30,31 compared with STIM2 EF-SAM which shows weaker affinity (i.e., Kd ~700 μM).32,55 Binding of Ca2+ keeps EF-SAM in a monomeric conformation and prevents dimerization/oligomerization and the accompanying conformational change prerequisite to the translocation of STIM to ER-PM junctions56 where coupling with Orai occurs.

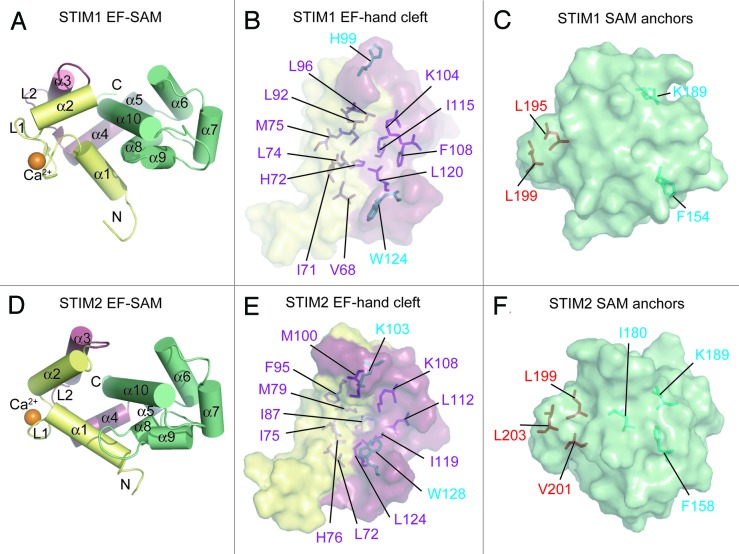

High resolution solution nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) structures of STIM1 and STIM2 EF-SAM have revealed that functional Ca2+ sensing distinctions between the isoforms involve factors in addition to Ca2+ affinity. The Ca2+-loaded STIM1 EF-SAM domain is primarily α-helical and folds into a compact and stable monomer (Fig. 2A). While primary sequence prediction reveals only a single canonical Ca2+ binding EF-hand motif (i.e., α1-loop1-α2), a second non-canonical EF-hand is, indeed present (i.e., α3-loop2-α4), exhibiting mutual loop1:loop2 stabilization via backbone hydrogen bonding between the carbonyl oxygen and amide hydrogen atoms of Val83 (loop1) and Ile115 (loop2).31,57 This STIM1 helix-loop-helix EF-hand pair forms a concave hydrophobic pocket comprised of residues from both the canonical and non-canonical EF-hands. The Val68, Ile71, His72, Leu74, Met75, and Leu92 from the canonical EF-hand and Leu96, Lys104, Phe108, Ile115, and Leu120 from the non-canonical EF-hand create this hydrophobic cleft (Fig. 2B). The STIM1 SAM domain folds into a 5 α-helix bundle (i.e., α6-α10), and a short linker helix (i.e., α5) connects the 2 luminal domains in sequence space (Fig. 2A). However, the EF-hand and SAM domains intimately interact through the hydrophobic EF-hand domain pocket and critical hydrophobic residues near the C-terminus of the α10 helix on the SAM domain (i.e., Leu195 and Leu199) (Fig. 2C). These α10 anchor residues pack into the EF-hand cleft and stabilize EF-SAM as a single entity.30

Figure 2. Ca2+-loaded STIM1 and STIM2 EF-SAM structural features. (A) Compact α-helical fold of Ca2+-loaded STIM1 EF-SAM. The 10 α-helices making up the compact fold of EF-SAM are labeled. (B) The STIM1 EF-hand hydrophobic cleft composition. The hydrophobic amino acids which create the non-polar cavity are shown as sticks (purple) on the surface depiction of the EF-hand domain. Residues which do not contribute to the cleft, but align with hydrophobic components of the STIM2 EF-hand cleft are colored cyan. (C) The STIM1 SAM domain hydrophobic anchors which pack into the hydrophobic cleft. The SAM domain is shown as a surface representation with hydrophobic anchor residues depicted as sticks (red). Residues which do not contribute to the hydrophobic core, but align with residues that are buried non-polar components of the STIM2 SAM domain are colored cyan. (D) Compact α-helical fold of Ca2+-loaded STIM2 EF-SAM. The 10 α-helices making up the compact fold are labeled. (E) The STIM2 EF-hand hydrophobic cleft composition. The hydrophobic residues which create the non-polar cavity are shown as sticks (purple and cyan) on the surface representation of the EF-hand domain. (F) The STIM2 SAM domain is shown as surface representation with hydrophobic anchor resides depicted as sticks (red). Residues which contribute to the hydrophobic core of the STIM2 SAM, but are not structurally conserved in the STIM1 SAM domain are shown in cyan. In (A–F), the domain color is consistent with Figure 1 and Ca2+ is shown as orange spheres; N and C denote amino and carboxy termini, respectively. Images were created with 2K60.pdb and 2L5Y.pdb coordinates for STIM1 and STIM2 EF-SAM, respectively.31,55

The intimate EF-hand:SAM domain interface revealed in the STIM1 EF-SAM structure was the first interaction involving well-characterized EF-hand and SAM domains identified in nature and has important implications on understanding the Ca2+ sensing function of STIM proteins. Upon Ca2+ depletion, STIM1 EF-SAM becomes markedly destabilized; further, this destabilization promotes homomeric EF-SAM:EF-SAM dimerization and oligomerization,30,31 a vital initiation step that leads to a conformational change in the cytosolic STIM1 region required for binding to and activating Orai channels at ER-PM junctions.26,28,33,56,58,59 The separate introduction of mutations in the EF-hand cleft and SAM domain anchors aimed at disruption of the structurally elucidated EF-hand:SAM domain interaction induces a similar destabilization in the EF-SAM context in vitro and activates full-length STIM1 in live cells without any perturbations in Ca2+ binding.31 These data suggest that a compact and well-folded EF-SAM domain in the presence of Ca2+ maintains STIM in a quiescent conformation, while Ca2+-depletion-induced destabilization of EF-SAM and the accompanying partial unfolding drives the oligomerization of the N-terminal region which initiates the downstream molecular mechanisms of SOCE activation.60

Examination of isoform-specific EF-SAM stability revealed that STIM2 EF-SAM is more stable than STIM1 in both the presence and absence of Ca2+ 32. This enhanced stability, despite the lower binding affinity, for STIM2 EF-SAM compared with STIM1 implies that other structural factors must compensate for attenuated stability conduced by the higher Kd.55,61 Indeed, the high resolution solution NMR structure of Ca2+-loaded STIM2 EF-SAM exposed 4 critical structural features which enhance the stability of STIM2 EF-SAM compared with STIM1.55 Overall, STIM2 EF-SAM is comprised of 10 α-helices forming a globular and compact shape similar to STIM1 (Fig. 2D). The EF-hand domain contains a canonical Ca2+ binding EF-hand motif (i.e., α1-loop1-α2) as well as a non-canonical EF-hand motif (i.e., α3-loop2-α4) that does not bind Ca2+, but plays a stabilizing role through backbone hydrogen bonding of the 2 adjacent loops [i.e., N(H) of Ile87 in loop1: C(O) of Ile119 in loop2]. This EF-hand pair creates a more extensive hydrophobic pocket than observed for STIM1, as 13 residues with hydrophobic character contribute to the cleft, compared with only 11 for STIM1. Specifically, Leu72, Ile75, His76, Met79, Ile87, Phe95, and Met100 from the canonical EF-hand and Lys103, Lys108, Leu112, Ile119, Leu124, and Trp128 from the non-canonical EF-hand make up the STIM2 EF-hand pocket (Fig. 2E). The increased hydrophobicity of the STIM2 EF-hand cleft is due to Lys103 and Trp128, which are directed out of the pocket in the case of STIM1 (i.e., His99 and Trp124 STIM1 numbering) (Fig. 2B and E). Lys103 is involved in the second structural factor which enhances the stability of STIM2 EF-SAM compared with STIM1, as this residue plays a dual role in contributing to the hydrophobicity of the EF-hand cleft via the aliphatic CH2 groups and forming a close ionic interaction with the acidic Asp200 located on the SAM domain through the positively charged ε-amino group.

The third structural factor enhancing the stability STIM2 EF-SAM is the hydrophobicity of the SAM domain core. The STIM2 SAM domain folds into a 5 α-helix bundle (i.e., α6-α10) with 12 hydrophobic residues at least 95% solvent inaccessible compared with only eight in the STIM1 SAM core. This enhanced hydrophobic packing is influenced by Ile180 which is not conserved in STIM1, and also involves the inclusion of Phe158 and Lys193 side chains which project out of the core in STIM1 SAM (i.e., Phe154 and Lys189 STIM1 numbering) (Fig. 2C and F). The final factor enhancing STIM2 SAM stability is the number of hydrophobic anchors at the α10 helix that pack into the EF-hand cleft. The STIM2 α10 helix conserves the 2 anchor residues identified in STIM1 EF-SAM (i.e., Leu199 and Leu203 STIM2 numbering); however, STIM2 contains an additional hydrophobic Val201 that is not conserved in STIM1, increasing the stability of the EF-hand:SAM domain interaction (Fig. 2C and F).

Functionally, a STIM1/STIM2 EF-SAM chimeric approach was used to corroborate the significance of stability to the Ca2+ sensing function of STIMs.55 Specifically, by delineating the canonical EF-hand motif, non-canonical EF-hand motif and the SAM domain as the building blocks of EF-SAM and engineering every STIM1/STIM2 chimeric combination, both ‘super-stable’ and ‘super-unstable’ EF-SAM domains were created. Importantly, when swapped with the endogenous EF-SAM in the full-length STIM1 context and expressed in live cells the ‘super-stable’ chimera which consists of the STIM1 canonical EF-hand, the STIM2 non-canonical EF-hand and the STIM2 SAM domain (i.e., ES122) demonstrates suppressed maximum attainable inward current densities indicative of decreased CRAC channel activity and increased times to maximal activation compared with wild-type STIM1. The ‘super-unstable’ chimera comprised of the STIM2 canonical EF-hand, the STIM1 non-canonical EF-hand and the STIM1 SAM domain (i.e., ES211) activates CRAC channels as efficiently as wild-type STIM1; however, the activation is spontaneous and independent of ER stored Ca2+. Therefore, the regulatory distinctions between STIM1 and STIM2 are facilitated, at least in part, by a balance between the EF-hand Ca2+ binding affinity and SAM domain stability; further, STIM1 has evolved as the principal SOCE regulator with a higher binding affinity and lower SAM stability, rendering it robustly responsive to agonist-induced ER Ca2+ store depletion, whereas STIM2 has evolved as a regulator of basal Ca2+ homeostasis with a lower binding affinity and higher SAM stability rendering a fraction of molecules persistently active at resting ER Ca2+ and the remaining fraction less responsive to small fluctuations in ER Ca2+ store depletion.53-55

CRAC-Activating Domain Structure and Function

The cytosolic domains of STIM1 contain the machinery required to couple to and gate Orai1 channels on the PM.38-40,62 Three independent groups identified similar boundaries within the conserved CC region as the minimal CRAC channel activating fragments with the CRAC activating domain (CAD, residues 342–448),39 STIM-Orai activating region (SOAR, residues 344–442)38 and coiled-coil boundary fragment 9 (ccb9, residues 346–450).63 Co-overexpression of any of these fragments with Orai1 in live cells constitutively assembles and gates Orai1 channels.38,39,63 At resting ER Ca2+ levels, these regions are inaccessible by Orai1 and/or in a quiescent conformation in the full-length context of STIM1. Ca2+-depletion-induced oligomerization of full-length STIM1, initiated by the N-terminal ER luminal domains and apposition of the CC1 region induces a constricted-to-extended structural change in the cytosolic domains which releases CAD/SOAR/ccb9 in a conformation which is conducive to recruiting and gating Orai1 CRAC channels at ER-PM junctions.26-29

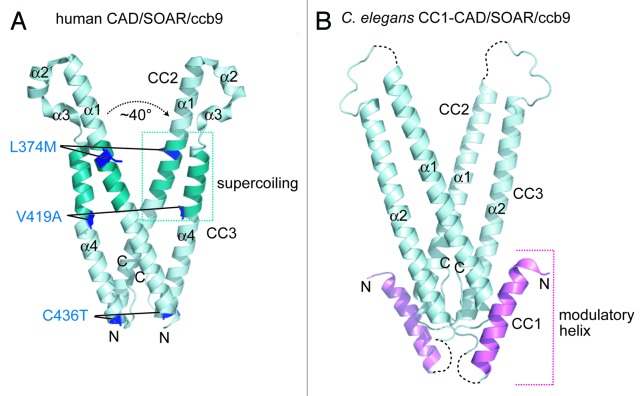

The crystal structure of a protein construct similar to human STIM1 CAD/SOAR/ccb9 (i.e., residues 345–444) bearing a triple Leu374Met/Val419Ala/Cys436Thr mutation that stabilizes the dimeric state was solved at ~1.9 Å.64 Although 3 distinct dimer interfaces were identified in the asymmetric unit, the biologically relevant dimer was defined from the interface with the greatest buried surface area (i.e., ~1800 Å2). The dimer identified in this manner shows the 2 monomers arranged in a 2-fold symmetrical V-shape (Fig. 3A). Consistent with this conformation, an ~2.6 Å crystal structure of Caenorhabditis elegans STIM cytosolic residues 212-410 (i.e., aligned with human residues ~233-465) identified from a single dimer interface in the asymmetric unit displays a similar symmetrical V-shape (Fig. 3B).64 Each monomer in the human protein contains a single extended α1-helix in the putative CC2 region followed by 2 short and 1 extended α-helix (i.e., α2-α4) in succession and antiparallel relative to α1 within predicted CC3; however, the C. elegans structure exhibits only a single extended α-helix and unstructured polypeptide chain in the region corresponding to the α2 and α3 human helices, raising questions about the relevance of the short α-helices in the human CC3 region (Fig. 3A and B). Analysis of the human V-shaped dimer using the SOCKET program which unambiguously and objectively identifies CC regions based on atomic resolution side chain packing65 reveals a single region of intramolecular left-handed coiling between 2 helices (i.e., supercoiling) involving residues Lys366-Ala376 of CC2 and Ile409-Ala419 of CC3 within each monomer (Fig. 3A). It is noteworthy that no intermolecular CC interactions were identified in the human STIM1 CAD/SOAR/ccb9 dimer. Triple mutants aimed at perturbing the dimer interface in the CC2 (i.e., Leu347Ala/Trp350Ala/Leu351Ala) and CC3 regions (i.e., Trp430Ala/Ile433Ala/Leu436Ala) abolish co-localization of this STIM1 fragment with Orai164; however, the effects on dimerization in the fragmental and full-length STIM1 context have not been determined.

Figure 3. Human and C. elegans structures of the cytosolic CAD/SOAR/ccb9 domains. (A) Crystal structure of a Leu374Met/Val419Ala/Cys436Thr triple mutant human CAD/SOAR/ccb9 dimer. The 4 α-helices making each monomer are labeled. The residues which were mutated to stabilize the dimer and facilitate crystallization are shown as sticks (blue). The region of intramolecular supercoiling between CC2 and CC3 helices are shaded teal. The intermolecular angle between the CC2 helices at the Tyr361 pivot point is indicated. (B) Crystal structure of the C. elegans CC1-CAD/SOAR/ccb9 dimer. The 2 α-helices making up each monomer are labeled. The CC1 helix demonstrated to modulate STIM1 activation is shaded magenta. Unresolved regions of low electron density are shown as broken black lines. In (A and B), the amino and carboxy termini are denoted by N and C, respectively. The human and C. elegans structure images were created with 3TEQ.pdb and 3TER.pdb coordinates, respectively.64

Interestingly, the larger C. elegans structure reveals an α-helix in putative CC1 (i.e., C. elegans residues 257-279), flanked by unstructured regions exhibiting low electron density; further, this helix packs against both extended helices corresponding to CC2 and CC3 in an intramolecular and intermolecular manner, respectively (Fig. 3B). Since deletion of the equivalent CC1 helix in human STIM1 results in constitutive activation of CRAC channels when co-overexpressed with Orai1 in live cells, this helix was initially labeled an ‘inhibitory helix’. However, more recent functional analyses have shown that mutations in this CC1 helix, rather than full deletion, can both constitutively activate as well as inhibit CRAC entry in live cells.26 Therefore, this region of CC1 likely plays an important modulatory role in the quiescent-to-active conformational change that occurs in the cytosolic domains, requisite for the recruitment and activation of Orai CRAC channels. While only intramolecular supercoiling was revealed in the cytosolic domain crystal structures, recent solution NMR studies in the Ikura laboratory (Ontario Cancer Institute) has shown that the cytosolic domains of STIM1 are also capable of forming intermolecular supercoils between CC1 as well as CC2 regions (Stathopulos PB and Ikura M, unpublished data). Taken together, the different interactions elucidated in the apo crystal structures and via solution NMR suggest that dynamic CC interplay is involved in the transition of the cytosolic STIM domains from a quiescent to Orai activation-competent conformation.

Drosophila melanogaster Orai Structure and Channel Formation

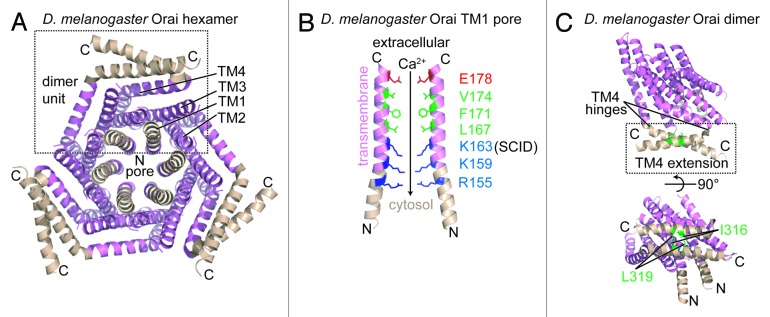

At present, there are no human Orai channel high resolution structures; nevertheless, a crystal structure of D. melanogaster Orai has been determined in which the native protein, consisting of 351 residues, was N- and C-terminally truncated in a construct encompassing residues 132–341 and carrying a Cys224Ser/Cys283Thr/Pro276Arg/Pro277Arg quadruple mutation to produce well-diffracting crystals (i.e., ~3.4 Å).51 Importantly, this D. melanogaster protein shares > 70% sequence identity with human Orai1 through the TM regions and, after reconstitution in liposomes, has the ability to conduct Ca2+ when constitutively activated with the Val174Ala (i.e., Val102Ala in human Orai1 numbering) mutation.34,51 Remarkably, this Orai crystal structure is formed by a trimer of dimer unit building blocks, exhibiting a 6-fold central axis of symmetry along the pore and overall 3-fold symmetry (Fig. 4A). The hexameric quaternary state is in contrast to several studies suggesting that Orai1 assembles as a functional tetramer.46-50 The TM1 helices line the pore in the hexameric structure, and a ring composed of Glu178 (i.e., Glu106 in human numbering) vital for Ca2+ binding and ion permeability is located near the extracellular surface of the assembled channel (Fig. 4B). The pore widens near the intracellular side and is lined by basic residues (i.e., Arg155, Lys159 and Lys163, corresponding to Arg83, Lys87, and Arg91 in human Orai1 numbering) (Fig. 4B). Sandwiched between the anionic and cationic pore regions is a hydrophobic section made up of Leu167, Phe171, and Val174 (i.e., corresponding to human Orai1 Leu95, Phe99, Val102) (Fig. 4B).

Figure 4.D. melanogaster Orai channel structure. (A) Cytosolic view of the Orai hexamer structure in the presumably closed state. An individual dimer unit building block is bounded by a broken black box. The TM1, TM2, TM3 and TM4 segments from a single monomer are labeled. (B) Residue composition of the TM1-consituted pore region. Only 2 TM1 segments exhibiting the greatest separation are shown for clarity. The acidic (red), hydrophobic (green), and basic (blue) pore-lining residues are shown relative to the extracellular space and the cytosol. The residue position mutated in a heritable form of severe combined immunodeficiency disease (i.e., R91W in human numbering) is labeled as ‘SCID’. The direction of the Ca2+ gradient (i.e., high to low concentration) is indicated with an arrow. (C) The TM4 C-terminal extension within the dimer unit. The antiparallel interaction between the C-terminal extensions is shown with hydrophobic residues involved in stabilizing this dimer interface depicted as sticks (green). The hinge regions responsible for creating the antiparallel orientation of the C-terminal extensions are indicated. In (A–C), color is consistent with Figure 2, and the amino and carboxy termini are labeled N and C, respectively. The D. melanogaster structure images were created with the 4HKR.pdb coordinate file.51

This acidic-hydrophobic-basic hierarchy implies a mechanism of permeation where extracellular Ca2+ is attracted to and binds the oppositely charged anionic ring; moreover, the widening of the pore would permit Ca2+ to move relatively freely into the central hydrophobic segment. It has been suggested that the basic region at the pore outlet binds anions,51 and these anions would have to be displaced for Ca2+ to permeate through to the cytosol. A widening of the pore on the intracellular side could dilute the electropositive potential facilitating the loss of the anions and permitting Ca2+ to diffuse into the cytosol. Interestingly, the Lys163Trp mutant D. melanogaster structure, crystallized using the same construct as the pseudo-wild-type and corresponding to human Arg91Trp that causes severe combined immunodeficiency,66 has a remarkably similar structure (i.e., Cα atom root mean square deviation of ~0.1 Å) as the pseudo-wild-type. The Lys163Trp residues extend the hydrophobicity of the central channel region and point into the center axis of the pore. It is tempting to speculate that the loss in function caused by the Lys163Trp (i.e., Arg91Trp in human numbering) mutation is due to an inability to undergo pore dilation required for Ca2+ permeability, restricted by inter-subunit Lys163Trp hydrophobic interactions. Although the precise role, if any, of anion binding to Ca2+ permeation through Orai channels has not been established, it should be noted that the Lys163Trp mutation abolishes at least one anion binding site.51

STIM1 CAD/SOAR/ccb9 interactions with both the N- and C-terminal Orai1 cystosolic regions are required for the recruitment and gating of the channel at ER-PM junctions.35-40 In the D. melanogaster crystal structure, the TM1 helix of each subunit linearly extends beyond the predicted depth of the inner PM leaflet into the cytosol without any breaks in the continuity of the helix (Fig. 4B). Further, studies show that human Orai1 remains active after deletion of residues 1–73; however, deletion of residues 73–84, corresponding to 145–156 in the D. melanogaster Orai structure that comprise most of the N-terminal extension (i.e., residues 144–157), abolishes interactions with CAD and eliminates CRAC entry,39 suggesting that the TM1 helical extension plays an important role in binding to STIM and the mechanism of Orai activation. The C-terminal helices are located on the periphery of the hexameric channel and also extend into the predicted cytosol; however, the cytosolic TM4 extensions which maintain an α-helical conformation run mostly parallel to the inner plane of the PM due to a hinge (i.e., residues 305–308) which bends the extensions (Fig. 4C). These cytosolic TM4 extensions adopt 1 of 2 conformations in the dimer unit building blocks such that the α-helices pair in an antiparallel manner via hydrophobic interactions (Fig. 4C). Critical residues which stabilize the inter-subunit antiparallel C-terminal domain interaction include Ile316 which packs against Leu319’ of the opposite subunit (i.e., Phe270 and Leu273 in human numbering). Considering that deletion of the C-terminal cytosolic extension abrogates interactions with STIM1,39,67,68 the antiparallel helix pair may represent a recruitment handle for Ca2+-depleted and oligomerized STIM1 at ER-PM junctions.

Ca2+-CaM:Orai1-N Structure and CRAC Entry Regulation

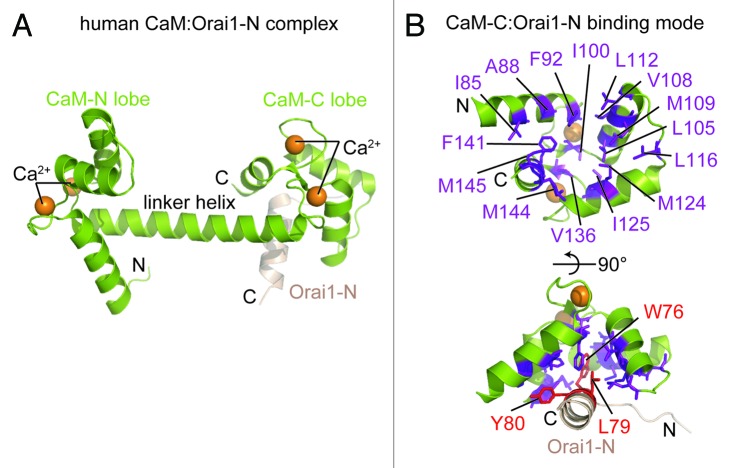

Ca2+-dependent inactivation (CDI) of CRAC channels is an important regulatory mechanism that confers limits on local Ca2+ concentrations influenced by SOCE; moreover, both STIM as well as calmodulin (CaM) have been linked to CDI of CRAC channels.14,69,70 STIM1 residues 470–491 are required for fast CDI of CRAC channels, although it is unclear whether this region serves as a bona fide Ca2+ sensor involved in the inactivation mechanism.70 Nevertheless, it has been demonstrated that CaM binds to the Orai1 N-terminal domain residues 68–91 in a Ca2+ dependent manner, and this CaM interaction is necessary for CDI of CRAC channels.70 A crystal structure of Ca2+-CaM in complex with an Orai1 construct encompassing N-terminal residues 69–91 solved at 1.9 Å shows that CaM is in the well-characterized dumbbell conformation, with an extended α-helix linking the 2 EF-hand lobes that coordinate 2 Ca2+ ions each (Fig. 5A).71 The Orai1-N peptide binds to the hydrophobic pocket created by the CaM-C lobe and retains the α-helical conformation observed in the D. melanogaster Orai crystal structure (see above); further, the CaM-N lobe remains free of Orai1-N in the crystal structure. The CaM-C:Orai1-N interaction is stabilized primarily by hydrophobic side chain packing. In particular, the Trp76, Leu79 andTyr80 residues of Orai1-N bind in a cleft formed by CaM-C consisting of Ala88, Ile85, Phe92, Ile100, Leu105, Val108, Met109, Leu112, Leu116, Met124, Ile125, Val136, Phe141, Met144, and Met145 (Fig. 5B).

Figure 5. Rat Ca2+-CaM structure in complex with a human Orai1 N-terminal fragment. (A) Dumbbell structure of Ca2+-loaded CaM forming a complex with a fragment of the Orai1 N-terminal domain (i.e., residues 69–91) through interactions at the C-lobe. The locations of the CaM lobes, central linker helix between lobes and the Orai1 N-terminal helix (beige) are labeled. (B) The Ca2+-CaM C-lobe hydrophobic cleft. The residues constituting the hydrophobic cleft are depicted as purple sticks. The anchor residues from the Orai1 N-terminal fragment which pack into the CaM C-lobe hydrophobic cavity are shown as red sticks. In (A and B), the amino and carboxy termini are labeled N and C, respectively, and the Ca2+ atoms are shown as orange spheres. The complex structure images were created with the 4EHQ.pdb coordinate file.71 All structure images in Figures 1–5 were rendered using The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Version 1.5.0.4 Schrödinger, LLC.

Solution experiments which include filtered-NOESY NMR, isothermal titration calorimetry, size exclusion chromatography and pull-down demonstrate, however, that CaM-N is capable of independently binding the Orai1-N peptide with somewhat lower binding affinity (i.e., CaM-C:Orai1-N Kd ~1 μM vs. CaM-N:Orai1-N Kd ~4 μM).71 The Ca2+-CaM:Orai1-N affinity is 2 orders of magnitude tighter than the affinity of STIM1 cytosolic residues 233–485 for a similar Orai1-N construct (i.e., residues 70–91; Kd ~250 μM).72 These stark differences in affinity for the Orai1 N-terminal domain advocate a CaM-dependent mechanism of CDI that is, at least in part, mediated by the free energy differences of the STIM1 and CaM complexes with Orai1-N. Increased Ca2+ levels local to the CRAC channel complex will favor the more stable Ca2+-CaM:Orai1-N interaction over STIM1:Orai1-N; however, it is tempting to speculate that, in addition to the displacement of the STIM1 cytosolic domains from Orai1-N by Ca2+-CaM, CDI may also involve the bridging of two Orai1-N domains by a single Ca2+-CaM molecule, thereby constricting the channel pore.71 It should also be noted that Ca2+-CaM can bind to the polybasic tails of both STIM1 (i.e., residues 667–685) and STIM2 (i.e., residues 730–746) with Kd ~1μM; moreover, this affinity is reduced by 2 orders of magnitude in the absence of Ca2+.73 Therefore, CaM may also downregulate SOCE via binding to STIMs in a Ca2+-dependent manner after localized cytosolic Ca2+ level increases, thereby inhibiting and/or disrupting ER-PM targeting of STIM1 molecules which is dependent on the polybasic stretches of STIMs.38,56,59,74,75

Concluding Remarks

The current available high resolution data of CRAC channel components and regulators have revealed a wealth of knowledge on the mechanisms controlling SOCE. In particular, the Ca2+-loaded STIM1 and STIM2 EF-SAM solution NMR structures have exposed the bases by which the luminal domains distinctly sense changes in ER stored Ca2+ 31; 55, signaling the cytosolic domains to induce CRAC entry and maintain basal intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis, respectively, via communication with Orai proteins; moreover, the balance between the EF-hand affinity for Ca2+ and SAM domain stability has evolutionarily defined these specific physiological roles for each isoform in mammals. Further, differences in the CAD/SOAR/ccb9 (i.e., CC2-CC3), CC1-CAD/SOAR/ccb9 crystal structures64 and solution NMR data on CC1-CC2 fragments (Stathopulos P.B. and Ikura M., Ontario Cancer Institute, unpublished data), both solved in the absence of Orai, are in line with the dynamic closed-to-open transition that the STIM1 cytosolic domains must undergo to adopt an Orai recruitment- and activation-competent conformation.26-29 The closed hexameric D. melanogaster Orai channel crystal structure reveals an extracellular-to-intracellular, anionic-hydrophobic-basic pore surface hierarchy that mediates Ca2+ permeation51; moreover, the TM1 helices that make up the pore contiguously extend into the cytosol exposing vital binding sites for, at least, STIM35,38-40 and CaM70 regulatory partners. Each lobe of CaM is capable of binding one TM1 extension with higher apparent affinity than the STIM1 cytosolic domain during CDI.71 The TM4 helices of D. melanogaster Orai also extend into the cytosol, stabilizing Orai dimer units through antiparallel intermolecular interactions.51 The antiparallel C-terminal domain extensions of TM4 make up a recruitment-like handle51 which may present Orai dimer C-terminal binding sites to STIM molecules at ER-PM junctions during the activation process.

Despite the tremendous progress in our comprehension on the structural biology of the CRAC entry molecular players, numerous targets of prime importance remain. For example, minimal high resolution structural information exists on the apo (i.e., Ca2+-free) luminal STIM domains which initiate the process of SOCE. Further, the structural basis for STIM CC3:CC3′ interactions involved in oligomerization is lacking, and it is currently unknown how or even whether CC3 directly interacts with the Orai proteins during the activation process. The human Orai channel structure in either the closed or open state has not been determined; moreover, the basis for Orai1 N-terminal or C-terminal interactions with STIM1 which have been implicated in channel recruitment and gating has not been disseminated. Additionally, the exact stoichiometry in the functional STIM:Orai complex has not been elucidated. The non-conserved far C-terminal domains of STIM are involved in targeting to ER-PM junctions via phosphoinositide binding, and high resolution structural data on the basis for this targeting is also missing.

In addition to these questions on static states, vital information on dynamic processes involved in the activation of CRAC channels remains outstanding. How is the Ca2+ binding event in the luminal domains transmitted to the cytosolic side of STIM in order to activate Orai? What conformational change in Orai is required for channel opening and how does STIM association induce this transformation? How do the numbers of active STIM:Orai complexes change at ER-PM junctions during the course of SOCE activation and how do these clusters of multiple active channels effect the functional properties of CRAC entry. Future studies on these aforementioned structural targets and questions are needed to paint a more complete picture of the molecular mechanisms governing SOCE which is vital to countless physiological processes in all eukaryotes.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Ikura M holds a Canada Research Chair in Cancer Structural Biology.

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/channels/article/26734

References

- 1.Bootman MD, Lipp P. (2001). Calcium signalling and regulation of cell function. Encyclopedia of Life Sciences, 1-7. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berridge MJ. (2009). Cell Signalling Biology, Vol. 2009. Portland Press, Ltd., London. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berridge MJ, Bootman MD, Roderick HL. Calcium signalling: dynamics, homeostasis and remodelling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4:517–29. doi: 10.1038/nrm1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Feske S. Calcium signalling in lymphocyte activation and disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:690–702. doi: 10.1038/nri2152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stathopulos PB, Seo MD, Enomoto M, Amador FJ, Ishiyama N, Ikura M. Themes and variations in ER/SR calcium release channels: structure and function. Physiology (Bethesda) 2012;27:331–42. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00013.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berridge MJ. The endoplasmic reticulum: a multifunctional signaling organelle. Cell Calcium. 2002;32:235–49. doi: 10.1016/S0143416002001823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tu H, Nosyreva E, Miyakawa T, Wang Z, Mizushima A, Iino M, Bezprozvanny I. Functional and biochemical analysis of the type 1 inositol (1,4,5)-trisphosphate receptor calcium sensor. Biophys J. 2003;85:290–9. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)74474-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Balshaw D, Gao L, Meissner G. Luminal loop of the ryanodine receptor: a pore-forming segment? Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:3345–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.7.3345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Srikanth S, Gwack Y. Orai1-NFAT signalling pathway triggered by T cell receptor stimulation. Mol Cells. 2013;35:182–94. doi: 10.1007/s10059-013-0073-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hogan PG, Chen L, Nardone J, Rao A. Transcriptional regulation by calcium, calcineurin, and NFAT. Genes Dev. 2003;17:2205–32. doi: 10.1101/gad.1102703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Putney JW. Origins of the concept of store-operated calcium entry. Front Biosci (Schol Ed) 2011;3:980–4. doi: 10.2741/202. [Schol Ed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Putney JW., Jr. A model for receptor-regulated calcium entry. Cell Calcium. 1986;7:1–12. doi: 10.1016/0143-4160(86)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lewis RS. The molecular choreography of a store-operated calcium channel. Nature. 2007;446:284–7. doi: 10.1038/nature05637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roos J, DiGregorio PJ, Yeromin AV, Ohlsen K, Lioudyno M, Zhang S, Safrina O, Kozak JA, Wagner SL, Cahalan MD, et al. STIM1, an essential and conserved component of store-operated Ca2+ channel function. J Cell Biol. 2005;169:435–45. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200502019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liou J, Kim ML, Heo WD, Jones JT, Myers JW, Ferrell JE, Jr., Meyer T. STIM is a Ca2+ sensor essential for Ca2+-store-depletion-triggered Ca2+ influx. Curr Biol. 2005;15:1235–41. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.05.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang SL, Yu Y, Roos J, Kozak JA, Deerinck TJ, Ellisman MH, Stauderman KA, Cahalan MD. STIM1 is a Ca2+ sensor that activates CRAC channels and migrates from the Ca2+ store to the plasma membrane. Nature. 2005;437:902–5. doi: 10.1038/nature04147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Prakriya M, Feske S, Gwack Y, Srikanth S, Rao A, Hogan PG. Orai1 is an essential pore subunit of the CRAC channel. Nature. 2006;443:230–3. doi: 10.1038/nature05122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vig M, Beck A, Billingsley JM, Lis A, Parvez S, Peinelt C, Koomoa DL, Soboloff J, Gill DL, Fleig A, et al. CRACM1 multimers form the ion-selective pore of the CRAC channel. Curr Biol. 2006;16:2073–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.08.085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vig M, Peinelt C, Beck A, Koomoa DL, Rabah D, Koblan-Huberson M, Kraft S, Turner H, Fleig A, Penner R, et al. CRACM1 is a plasma membrane protein essential for store-operated Ca2+ entry. Science. 2006;312:1220–3. doi: 10.1126/science.1127883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yeromin AV, Zhang SL, Jiang W, Yu Y, Safrina O, Cahalan MD. Molecular identification of the CRAC channel by altered ion selectivity in a mutant of Orai. Nature. 2006;443:226–9. doi: 10.1038/nature05108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang SL, Yeromin AV, Zhang XH, Yu Y, Safrina O, Penna A, Roos J, Stauderman KA, Cahalan MD. Genome-wide RNAi screen of Ca(2+) influx identifies genes that regulate Ca(2+) release-activated Ca(2+) channel activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:9357–62. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603161103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cai X. Molecular evolution and functional divergence of the Ca(2+) sensor protein in store-operated Ca(2+) entry: stromal interaction molecule. PLoS One. 2007;2:e609. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Manji SS, Parker NJ, Williams RT, van Stekelenburg L, Pearson RB, Dziadek M, Smith PJ. STIM1: a novel phosphoprotein located at the cell surface. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1481:147–55. doi: 10.1016/S0167-4838(00)00105-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Williams RT, Manji SS, Parker NJ, Hancock MS, Van Stekelenburg L, Eid JP, Senior PV, Kazenwadel JS, Shandala T, Saint R, et al. Identification and characterization of the STIM (stromal interaction molecule) gene family: coding for a novel class of transmembrane proteins. Biochem J. 2001;357:673–85. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3570673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Williams RT, Senior PV, Van Stekelenburg L, Layton JE, Smith PJ, Dziadek MA. Stromal interaction molecule 1 (STIM1), a transmembrane protein with growth suppressor activity, contains an extracellular SAM domain modified by N-linked glycosylation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002;1596:131–7. doi: 10.1016/S0167-4838(02)00211-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yu F, Sun L, Hubrack S, Selvaraj S, Machaca K. Intramolecular shielding maintains the ER Ca²⁺ sensor STIM1 in an inactive conformation. J Cell Sci. 2013;126:2401–10. doi: 10.1242/jcs.117200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhou Y, Srinivasan P, Razavi S, Seymour S, Meraner P, Gudlur A, Stathopulos PB, Ikura M, Rao A, Hogan PG. Initial activation of STIM1, the regulator of store-operated calcium entry. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2013;20:973–81. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Muik M, Fahrner M, Schindl R, Stathopulos P, Frischauf I, Derler I, Plenk P, Lackner B, Groschner K, Ikura M, et al. STIM1 couples to ORAI1 via an intramolecular transition into an extended conformation. EMBO J. 2011;30:1678–89. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Korzeniowski MK, Manjarrés IM, Varnai P, Balla T. Activation of STIM1-Orai1 involves an intramolecular switching mechanism. Sci Signal. 2010;3:ra82. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2001122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stathopulos PB, Li GY, Plevin MJ, Ames JB, Ikura M. Stored Ca2+ depletion-induced oligomerization of stromal interaction molecule 1 (STIM1) via the EF-SAM region: An initiation mechanism for capacitive Ca2+ entry. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:35855–62. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M608247200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stathopulos PB, Zheng L, Li GY, Plevin MJ, Ikura M. Structural and mechanistic insights into STIM1-mediated initiation of store-operated calcium entry. Cell. 2008;135:110–22. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zheng L, Stathopulos PB, Li GY, Ikura M. Biophysical characterization of the EF-hand and SAM domain containing Ca2+ sensory region of STIM1 and STIM2. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;369:240–6. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.12.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Luik RM, Wang B, Prakriya M, Wu MM, Lewis RS. Oligomerization of STIM1 couples ER calcium depletion to CRAC channel activation. Nature. 2008;454:538–42. doi: 10.1038/nature07065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cai X. Molecular evolution and structural analysis of the Ca(2+) release-activated Ca(2+) channel subunit, Orai. J Mol Biol. 2007;368:1284–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Frischauf I, Muik M, Derler I, Bergsmann J, Fahrner M, Schindl R, Groschner K, Romanin C. Molecular determinants of the coupling between STIM1 and Orai channels: differential activation of Orai1-3 channels by a STIM1 coiled-coil mutant. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:21696–706. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.018408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Muik M, Frischauf I, Derler I, Fahrner M, Bergsmann J, Eder P, Schindl R, Hesch C, Polzinger B, Fritsch R, et al. Dynamic coupling of the putative coiled-coil domain of ORAI1 with STIM1 mediates ORAI1 channel activation. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:8014–22. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M708898200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Muik M, Schindl R, Fahrner M, Romanin C. Ca(2+) release-activated Ca(2+) (CRAC) current, structure, and function. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2012;69:4163–76. doi: 10.1007/s00018-012-1072-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yuan JP, Zeng W, Dorwart MR, Choi YJ, Worley PF, Muallem S. SOAR and the polybasic STIM1 domains gate and regulate Orai channels. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11:337–43. doi: 10.1038/ncb1842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Park CY, Hoover PJ, Mullins FM, Bachhawat P, Covington ED, Raunser S, Walz T, Garcia KC, Dolmetsch RE, Lewis RS. STIM1 clusters and activates CRAC channels via direct binding of a cytosolic domain to Orai1. Cell. 2009;136:876–90. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhou Y, Meraner P, Kwon HT, Machnes D, Oh-hora M, Zimmer J, Huang Y, Stura A, Rao A, Hogan PG. STIM1 gates the store-operated calcium channel ORAI1 in vitro. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2010;17:112–6. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhou Y, Ramachandran S, Oh-Hora M, Rao A, Hogan PG. Pore architecture of the ORAI1 store-operated calcium channel. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:4896–901. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1001169107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McNally BA, Yamashita M, Engh A, Prakriya M. Structural determinants of ion permeation in CRAC channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:22516–21. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909574106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McNally BA, Prakriya M. Permeation, selectivity and gating in store-operated CRAC channels. J Physiol. 2012;590:4179–91. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2012.233098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McNally BA, Somasundaram A, Yamashita M, Prakriya M. Gated regulation of CRAC channel ion selectivity by STIM1. Nature. 2012;482:241–5. doi: 10.1038/nature10752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang SL, Yeromin AV, Hu J, Amcheslavsky A, Zheng H, Cahalan MD. Mutations in Orai1 transmembrane segment 1 cause STIM1-independent activation of Orai1 channels at glycine 98 and channel closure at arginine 91. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:17838–43. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1114821108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mignen O, Thompson JL, Shuttleworth TJ. Orai1 subunit stoichiometry of the mammalian CRAC channel pore. J Physiol. 2008;586:419–25. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.147249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Maruyama Y, Ogura T, Mio K, Kato K, Kaneko T, Kiyonaka S, Mori Y, Sato C. Tetrameric Orai1 is a teardrop-shaped molecule with a long, tapered cytoplasmic domain. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:13676–85. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M900812200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Thompson JL, Shuttleworth TJ. How many Orai’s does it take to make a CRAC channel? Sci Rep. 2013;3:1961. doi: 10.1038/srep01961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Demuro A, Penna A, Safrina O, Yeromin AV, Amcheslavsky A, Cahalan MD, Parker I. Subunit stoichiometry of human Orai1 and Orai3 channels in closed and open states. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:17832–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1114814108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Penna A, Demuro A, Yeromin AV, Zhang SL, Safrina O, Parker I, Cahalan MD. The CRAC channel consists of a tetramer formed by Stim-induced dimerization of Orai dimers. Nature. 2008;456:116–20. doi: 10.1038/nature07338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hou X, Pedi L, Diver MM, Long SB. Crystal structure of the calcium release-activated calcium channel Orai. Science. 2012;338:1308–13. doi: 10.1126/science.1228757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Berna-Erro A, Braun A, Kraft R, Kleinschnitz C, Schuhmann MK, Stegner D, Wultsch T, Eilers J, Meuth SG, Stoll G, et al. STIM2 regulates capacitive Ca2+ entry in neurons and plays a key role in hypoxic neuronal cell death. Sci Signal. 2009;2:ra67. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Brandman O, Liou J, Park WS, Meyer T. STIM2 is a feedback regulator that stabilizes basal cytosolic and endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ levels. Cell. 2007;131:1327–39. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Collins SR, Meyer T. Evolutionary origins of STIM1 and STIM2 within ancient Ca2+ signaling systems. Trends Cell Biol. 2011;21:202–11. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2011.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zheng L, Stathopulos PB, Schindl R, Li GY, Romanin C, Ikura M. Auto-inhibitory role of the EF-SAM domain of STIM proteins in store-operated calcium entry. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:1337–42. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1015125108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Liou J, Fivaz M, Inoue T, Meyer T. Live-cell imaging reveals sequential oligomerization and local plasma membrane targeting of stromal interaction molecule 1 after Ca2+ store depletion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:9301–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702866104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Stathopulos PB, Ikura M. Structure and function of endoplasmic reticulum STIM calcium sensors. Curr Top Membr. 2013;71:59–93. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-407870-3.00003-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Covington ED, Wu MM, Lewis RS. Essential role for the CRAC activation domain in store-dependent oligomerization of STIM1. Mol Biol Cell. 2010;21:1897–907. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E10-02-0145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Korzeniowski MK, Popovic MA, Szentpetery Z, Varnai P, Stojilkovic SS, Balla T. Dependence of STIM1/Orai1-mediated calcium entry on plasma membrane phosphoinositides. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:21027–35. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.012252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Stathopulos PB, Ikura M. Partial unfolding and oligomerization of stromal interaction molecules as an initiation mechanism of store operated calcium entry. Biochem Cell Biol. 2010;88:175–83. doi: 10.1139/O09-125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Stathopulos PB, Ikura M. Structurally delineating stromal interaction molecules as the endoplasmic reticulum calcium sensors and regulators of calcium release-activated calcium entry. Immunol Rev. 2009;231:113–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2009.00814.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Huang GN, Zeng W, Kim JY, Yuan JP, Han L, Muallem S, Worley PF. STIM1 carboxyl-terminus activates native SOC, I(crac) and TRPC1 channels. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:1003–10. doi: 10.1038/ncb1454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kawasaki T, Lange I, Feske S. A minimal regulatory domain in the C terminus of STIM1 binds to and activates ORAI1 CRAC channels. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;385:49–54. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.05.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yang X, Jin H, Cai X, Li S, Shen Y. Structural and mechanistic insights into the activation of Stromal interaction molecule 1 (STIM1) Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:5657–62. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1118947109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Walshaw J, Woolfson DN. Socket: a program for identifying and analysing coiled-coil motifs within protein structures. J Mol Biol. 2001;307:1427–50. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Feske S, Gwack Y, Prakriya M, Srikanth S, Puppel SH, Tanasa B, Hogan PG, Lewis RS, Daly M, Rao A. A mutation in Orai1 causes immune deficiency by abrogating CRAC channel function. Nature. 2006;441:179–85. doi: 10.1038/nature04702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zheng H, Zhou MH, Hu C, Kuo E, Peng X, Hu J, Kuo L, Zhang SL. Differential roles of the C and N termini of Orai1 protein in interacting with stromal interaction molecule 1 (STIM1) for Ca2+ release-activated Ca2+ (CRAC) channel activation. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:11263–72. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.450254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.McNally BA, Somasundaram A, Jairaman A, Yamashita M, Prakriya M. The C- and N-terminal STIM1 binding sites on Orai1 are required for both trapping and gating CRAC channels. J Physiol. 2013;591:2833–50. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2012.250456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Derler I, Fahrner M, Muik M, Lackner B, Schindl R, Groschner K, Romanin C. A Ca2(+ )release-activated Ca2(+) (CRAC) modulatory domain (CMD) within STIM1 mediates fast Ca2(+)-dependent inactivation of ORAI1 channels. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:24933–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C109.024083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Mullins FM, Park CY, Dolmetsch RE, Lewis RS. STIM1 and calmodulin interact with Orai1 to induce Ca2+-dependent inactivation of CRAC channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:15495–500. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906781106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Liu Y, Zheng X, Mueller GA, Sobhany M, DeRose EF, Zhang Y, London RE, Birnbaumer L. Crystal structure of calmodulin binding domain of orai1 in complex with Ca2+ calmodulin displays a unique binding mode. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:43030–41. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.380964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Derler I, Plenk P, Fahrner M, Muik M, Jardin I, Schindl R, Gruber HJ, Groschner K, Romanin C. The extended transmembrane Orai1 N-terminal (ETON) region combines binding interface and gate for Orai1 activation by STIM1. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:29025–34. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.501510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bauer MC, O’Connell D, Cahill DJ, Linse S. Calmodulin binding to the polybasic C-termini of STIM proteins involved in store-operated calcium entry. Biochemistry. 2008;47:6089–91. doi: 10.1021/bi800496a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Calloway N, Owens T, Corwith K, Rodgers W, Holowka D, Baird B. Stimulated association of STIM1 and Orai1 is regulated by the balance of PtdIns(4,5)P₂ between distinct membrane pools. J Cell Sci. 2011;124:2602–10. doi: 10.1242/jcs.084178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Walsh CM, Chvanov M, Haynes LP, Petersen OH, Tepikin AV, Burgoyne RD. Role of phosphoinositides in STIM1 dynamics and store-operated calcium entry. Biochem J. 2010;425:159–68. doi: 10.1042/BJ20090884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]