Abstract

High brain and acute leukemia, cytoplasmic (BAALC) expression defines an important risk factor in cytogenetically normal acute myeloid leukemia (CN-AML). The prognostic value of BAALC expression in relation to other molecular prognosticators was analyzed in 326 CN-AML patients (<65 years). At diagnosis, high BAALC expression was associated with prognostically adverse mutations: FLT3 internal tandem duplication (FLT3-ITD) with an FLT3-ITD/FLT3 wild-type (wt) ratio of ⩾0.5 (P=0.001), partial tandem duplications within the MLL gene (MLL-PTD) (P=0.002), RUNX1 mutations (mut) (P<0.001) and WT1mut (P=0.001), while it was negatively associated with NPM1mut (P<0.001). However, high BAALC expression was also associated with prognostically favorable biallelic CEBPA (P=0.001). Survival analysis revealed an independent adverse prognostic impact of high BAALC expression on overall survival (OS) and event-free survival (EFS), and also on OS when eliminating the effect of allogeneic stem cell transplantation (SCT) (OSTXcens). Furthermore, we analyzed BAALC expression in 416 diagnostic and follow-up samples of 66 patients. During follow-up, BAALC expression correlated with mutational load or expression levels, respectively, of other minimal residual disease markers: FLT3-ITD (r=0.650, P<0.001), MLL-PTD (r=0.728, P<0.001), NPM1mut (r=0.599, P<0.001) and RUNX1mut (r=0.889, P<0.001). Moreover, a reduction in BAALC expression after the second cycle of induction chemotherapy was associated with improved EFS. Thus, our data underline the utility of BAALC expression as a marker for prognostic risk stratification and detection of residual disease in CN-AML.

Keywords: BAALC expression, CN-AML, prognosis, MRD

Introduction

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is a heterogeneous disease with respect to clinical picture and therapeutic outcome, partly reflected by differences in cytogenetics and molecular genetics. In approximately 55% of patients with AML, cytogenetic aberrations can be used for risk stratification, but there is still a large subgroup of patients who lack informative chromosome markers.1 Differential prognosis of cytogenetically normal AML (CN-AML) has been allocated by the discovery of specific molecular abnormalities.2 The most useful markers implicated in prognostication are NPM1 mutations (mut), FLT3 internal tandem duplication (FLT3-ITD),3, 4, 5, 6, 7 biallelic CEBPA mutations (biCEBPA),8 partial tandem duplications within the MLL gene (MLL-PTD), RUNX1mut and ASXL1mut.9, 10, 11, 12

Besides mutations, deregulated expression of genes involved in cell proliferation, survival and differentiation, for example, brain and acute leukemia, cytoplasmic (BAALC),13, 14 ERG,15 MN1,15 WT116 and EVI1,17 have been identified as prognostic markers. An elevated expression of the BAALC gene was originally discovered in a gene expression profiling study of AML with trisomy 8, but was later also found in other AML and in acute lymphoblastic leukemia.18, 19 High BAALC expression was shown to correlate with FLT3-ITD, NPM1 wild-type (wt) and high expression levels of ERG and MN1 and has been linked to poor prognosis, especially in CN-AML.13, 14, 15, 20 The function of BAALC in the hematopoietic system as well as its contribution in leukemogenesis is not fully understood. Recently, it was proposed that BAALC blocks myeloid differentiation and thus requires a second mutation, which gives a proliferative advantage to induce leukemia.21

Risk stratification based on pretreatment genetic signatures has become a critical step in the therapeutic decision-making process. For instance, a large study of 3638 patients has revealed that only low- or intermediate-risk but not good-risk group patients would benefit from allogeneic cell transplantation in first complete remission.22, 23 Moreover, the detection of mutations during the course of therapy is an important prognostic tool, since the outgrowth of minimal residual disease (MRD) cells is responsible for relapse.24, 25 Nowadays, highly sensitive and fast methods (for example, quantitative real-time PCR) facilitate molecular monitoring and early detection of relapse, thereby allowing direct treatment intervention. In spite of the great progress in understanding the biology of AML, only 40–45% of patients younger than 60 years achieve long-term survival.26, 27

Therefore, it is of great interest to further analyze the recently described biomarkers to refine risk-adapted models. The objective of this study was to evaluate the prognostic impact of BAALC expression on clinical outcome in the context of other relevant molecular prognosticators and to examine its utility as a marker for detection of residual disease in CN-AML.

Patients and methods

Patients

All bone marrow (BM) (n=524) or peripheral blood (PB) (n=152) samples included in the study were referred to our laboratory for diagnostic or follow-up assessment of AML between September 2005 and September 2012. AML was diagnosed according to the FAB (French-American-British) and WHO (World Health Organization) classifications.28, 29 To the best of our knowledge, all patients had de novo AML without any preceding malignancy or myelodysplastic syndrome. The characteristics of the 326 patients analyzed at diagnosis are summarized in Table 1. Of these, 290 patients received intensive treatment according to German standard AML protocols. Before therapy, all patients gave their informed consent for scientific evaluations, after having been advised about the purpose and investigational nature of the study. The study was approved by the Internal Review Board of the MLL and adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Table 1. Pretreatment clinical characteristics and molecular features at diagnosis according to BAALC expression status in CN-AML.

| Total cohort | Low BAALC expression | High BAALC expression | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n=326 | n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Sex, no. (%) | 0.825 | |||

| Female | 167 (51.2) | 85 (52.1) | 82 (50.3) | |

| Male | 159 (48.8) | 78 (47.9) | 81 (49.7) | |

| Age (n=326), years (range) | 0.063 | |||

| Median | 52.9 (18.3–64.8) | 53.8 (18.5–64.8) | 52.4 (18.3–64.5) | |

| Mean | 50.8 | 51.9 | 49.6 | |

| WBC count (n=256), x109/l (range) | 0.807 | |||

| Median | 24.4 (0.6–400.0) | 32.1 (0.7–313.2) | 18.0 (0.6–400.0) | |

| Mean | 53.8 | 54.9 | 52.8 | |

| Hb levels (n=243), g/dl (range) | 0.700 | |||

| Median | 9.2 (2.8–16.3) | 9.2 (2.8–16.3) | 9.1 (4.0–14.4) | |

| Mean | 9.3 | 9.3 | 9.2 | |

| Platelet count (n=243), x109/l (range) | 0.939 | |||

| Median | 64.0 (6.0–454.0) | 64.0 (6.0–342.0) | 65.0 (6.0–454.0) | |

| Mean | 90.8 | 91.2 | 90.4 | |

| PB blasts (n=156), % (range) | 0.285 | |||

| Median | 50.5 (0–100) | 49.5 (0–100) | 52.5 (0–97) | |

| Mean | 48.9 | 45.8 | 51.5 | |

| BM blasts (n=269), % (range) | 0.951 | |||

| Median | 68.5 (6–99) | 73.6 (6–99) | 66.0 (9–99) | |

| Mean | 63.8 | 63.9 | 63.7 | |

| NPM1, no. (%) | <0.001 | |||

| Mutated | 209 (64.1) | 138 (84.7) | 71 (43.6) | |

| Wild type | 117 (35.9) | 25 (15.3) | 92 (56.4) | |

| FLT3-ITD, no. (%) | 0.052 | |||

| Present | 124 (38.0) | 53 (32.5) | 71 (43.6) | |

| Absent | 202 (62.0) | 110 (67.5) | 92 (56.4) | |

| NPM1mut and FLT3wt or FLT3-ITD/FLT3wt<0.5, no. (%) | 151 (46.3) | 114 (69.9) | 37 (22.7) | <0.001 |

| FLT3-ITD/FLT3wt<0.5, no. (%) | 252 (77.3) | 139 (85.3) | 113 (69.3) | 0.001 |

| FLT3-ITD/FLT3wt ⩾0.5, no. (%) | 74 (22.7) | 24 (14.7) | 50 (30.7) | |

| FLT3-TKD, no. (%) | 0.058 | |||

| Present | 31 (9.5) | 21 (12.9) | 10 (6.1) | |

| Absent | 295 (90.5) | 142 (87.1) | 153 (93.9) | |

| MLL-PTD, no. (%) | 0.002 | |||

| Present | 26 (8.0) | 5 (3.1) | 21 (12.9) | |

| Absent | 300 (92.0) | 158 (96.9) | 142 (87.1) | |

| RUNX1, no. (%), (n=325) | <0.001 | |||

| Mutated | 33 (10.2) | 2 (1.2) | 31 (19.0) | |

| Wild type | 292 (89.8) | 160 (98.8) | 132 (81.0) | |

| ASXL1, no. (%) | 0.257 | |||

| Mutated | 13 (4.0) | 4 (2.5) | 9 (5.5) | |

| Wild type | 313 (96.0) | 159 (97.5) | 154 (94.5) | |

| CEBPA, no. (%) | 0.003 | |||

| Mutated | 30 (9.2) | 7 (4.3) | 23 (14.1) | |

| Wild type | 296 (90.8) | 156 (95.7) | 140 (85.9) | |

| Monoallelic and wild type, no. (%) | 308 (94.5) | 161 (98.8) | 147 (90.2) | 0.001 |

| Biallelic (n=332), no. (%) | 18 (5.5) | 2 (1.2) | 16 (9.8) | |

| IDH1R132, no. (%), (n=324) | 0.397 | |||

| Mutated | 39 (12.0) | 22 (13.7) | 17 (10.4) | |

| Wild type | 285 (88.0) | 139 (86.3) | 146 (89.6) | |

| IDH2R140, no. (%), (n=325) | 0.121 | |||

| Mutated | 48 (14.8) | 29 (17.9) | 19 (11.7) | |

| Wild type | 277 (85.2) | 133 (82.1) | 144 (88.3) | |

| IDH2R172, no. (%), (n=325) | 0.030 | |||

| Mutated | 6 (1.8) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (3.7) | |

| Wild type | 319 (98.2) | 162 (100.0) | 157 (96.3) | |

| NRAS, no. (%) | 0.166 | |||

| Mutated | 50 (15.3) | 20 (12.3) | 30 (18.4) | |

| Wild type | 276 (84.7) | 143 (87.7) | 133 (81.6) | |

| TET2, no. (%), (n=80) | 0.593 | |||

| Mutated | 18 (22.5) | 10 (26.3) | 8 (19.0) | |

| Wild type | 62 (77.5) | 28 (73.7) | 34 (81.0) | |

| WT1, no. (%) | 0.001 | |||

| Mutated | 27 (8.3) | 5 (3.1) | 22 (13.5) | |

| Wild type | 298 (91.7) | 157 (96.9) | 141 (86.5) |

Abbreviations: BAALC, brain and acute leukemia, cytoplasmic; BM, bone marrow; CN-AML, cytogenetically normal acute myeloid leukemia; FLT3-ITD, FLT3 internal tandem duplication; Hb, hemoglobin; PB, peripheral blood; WBC, white blood cell; wt, wild type.

Cytomorphology, cytogenetics and immunophenotyping

Cytomorphologic assessment was based on May-Grünwald-Giemsa stains, myeloperoxidase reaction, and non-specific esterase using alpha-naphthyl-acetate as described previously and was performed according to the criteria defined in the FAB and the WHO classifications in 325 patients.28, 29, 30 Cytogenetic studies were performed in all cases after short-term culture. Karyotypes, analyzed after G-banding, were described according to the International System for Human Cytogenetic nomenclature.31 The minimum number of analyzed metaphases was 20 per case except for 20 patients, where only 9–19 metaphases could be analyzed. Cytogenetic results were available for all patients in the study. Immunophenotyping was performed in 155 cases as described previously.32, 33

Examination time points

BAALC mRNA expression was analyzed in 326 de novo AML patients (<65 years) with CN-AML by the use of quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR). Median follow-up was 2.7 years. In 66 cases follow-up samples were available, with 57 cases showing high and 9 cases showing low BAALC expression at diagnosis. In total, 350 follow-up samples from different time points during therapy were analyzed. A total of 2–20 samples (median, 5; mean, 6.3) were analyzed per patient.

Molecular analysis and BAALC determination

Mononuclear cells from PB or BM were separated by Ficoll density gradient. Either mRNA or RNA was extracted with the MagnaPureLC mRNA Kit I (Roche Applied Science, Mannheim, Germany) or with the MagNA Pure 96 Cellular RNA Large Volume Kit (Roche Applied Science). The cDNA synthesis from mRNA or RNA from an equivalent of 2.5–5 × 106 cells was performed using 300 U Superscript II (Life Technologies, Darmstadt, Germany) and random hexamer primers (Roche Applied Science). qPCR was performed by the use of the Applied Biosystems 7500 Fast Real Time PCR System (Life Technologies). Each sample was analyzed at least in duplicates. BAALC expression was determined using previously described primers and probes.13 For detection of ABL1, the following primers and probe were used: ABL_ex6-7R, GCAGCAAGATCTCTGTGGATGAAGT, ABL2_exon5F, ATGACCTACGGGAACCTCCT and ABL-Probe_ex6, CTGCCGGTTGCACTCCCTCAGGTA. Amplification was performed after initial incubation at 95 °C for 1 min in a 2-step cycle procedure (95 °C, 15 s and 60 °C, 30 s) for 40 cycles.

To calculate BAALC and ABL1 copy numbers, standard curves for both assays were generated in every run by 10-fold dilution series of five different plasmid concentrations. The expression of BAALC was normalized against the expression of the control gene ABL1 to adjust for variations in mRNA quality and varying efficiencies of cDNA synthesis.

Analyses for mutations of ASXL1, CEBPA, FLT3-TKD, IDH1R132, IDH2R140, IDH2R172, NPM1, NRAS, RUNX1, WT1, TET2 and TP53, as well as MLL-PTD and FLT3-ITD were described previously.5, 9, 12, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40 For CEBPA, the term ‘biallelic' (biCEBPA) was used for patients with one N-terminal and one bZIP gene mutation, since it has been published that these mutations are usually biallelic and no wt CEBPA is expressed in these cases.8 Samples showing only one mutation were referred as to monoallelic CEBPA (monoCEBPA).

Statistical analysis

First, BAALC expression was analyzed as a continuous variable. Subsequently, the median expression level was calculated and used to dichotomize the total patient cohort into low and high expressers. Overall survival (OS) was the time from diagnosis to death or last follow-up. Event-free survival (EFS) was defined as the time from diagnosis to treatment failure, relapse, death, or last follow-up. To eliminate the effect of allogeneic stem cell transplantation (SCT), OS was also recalculated by censoring patients at the day of transplantation (OSTXcens). Survival curves were calculated for OS, EFS and OSTXcens according to Kaplan–Meier and compared using the two-sided log-rank test. Cox regression analysis was performed for OS, EFS and OSTXcens with different parameters as covariates. Median follow-up was calculated taking the respective last observations in surviving cases into account and censoring non-surviving cases at the time of death. Results were considered as significant at P<0.05. Parameters that were significant in univariate analyses were included in multivariate analyses. Dichotomous variables were compared between different groups using the Fisher's exact test and continuous variables by Student's t-test. Correlation coefficient was specified as Spearman's rank correlation. All reported P-values are two-sided. No adjustments for multiple comparisons were performed. SPSS software version 19.0.0 (IBM corporation, Armonk, NY, USA) was used for statistical analysis.

Results

Association of BAALC expression with patient characteristics and molecular mutations at diagnosis

At diagnosis, BAALC expression of 326 patients ranged from 0.1 to 8019.9% BAALC/ABL1 with a median of 33.1%. With regard to patient characteristics, no correlation between BAALC expression levels and sex, white blood cell (WBC) count, PB blasts, BM blasts or hemoglobin levels was found (Table 1). There was a trend of high BAALC expressers to be of younger age than the low expressers (49.6 vs 51.9 years, P=0.063). In terms of molecular characteristics, patients with high BAALC expression were more likely to harbor FLT3-ITD (71/163, 43.6% vs 53/163, 32.5%, P=0.052), MLL-PTD (21/163, 12.9% vs 5/163, 3.1%, P=0.002) and to carry mutations in RUNX1 (31/163, 19.0% vs 2/162, 1.2%, P<0.001), CEBPA (23/163, 14.1% vs 7/163, 4.3%, P=0.003) or WT1 (22/163, 13.5% vs 5/162, 3.1%, P=0.001), whereas NPM1mut was negatively correlated (71/163, 43.6% vs 138/163, 84.7%, P<0.001). Separation of FLT3-ITD according to its mutation load revealed a strong correlation of high BAALC expression to FLT3-ITD with an FLT3-ITD/FLT3wt ratio of ⩾0.5, as compared with low BAALC expression (50/163, 30.7% vs 24/163, 14.7%, P=0.001). For CEBPA, a significant correlation of high BAALC expression with biCEBPA could be shown (16/163, 9.8% vs 2/163, 1.2%, P=0.001).

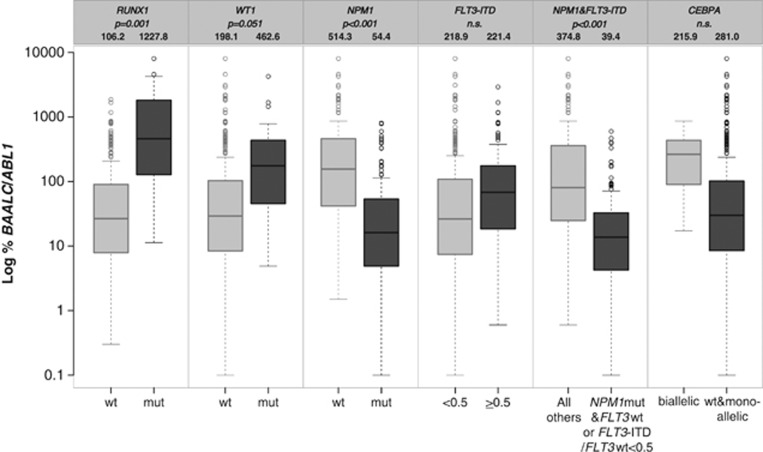

To confirm these correlations, BAALC expression was also analyzed as a continuous variable, thereby comparing mean expression levels of BAALC within the molecular groups (Figure 1). In this analysis, patients with RUNX1mut and WT1mut revealed higher mean BAALC expression levels than patients without these mutations (1227.8 vs 106.2, P=0.001 and 462.6 vs 198.1, P=0.051, respectively). Mean expression levels of BAALC in patients with NPM1mut were significantly lower as compared with those in patients with NPM1wt (54.4 vs 514.3, P<0.001). Analyzing BAALC expression with regard to FLT3-ITD, mean BAALC expression levels were almost identical in FLT3-ITD-positive patients compared with FLT3wt patients, also when analyzing FLT3-ITD according to its mutation load (FLT3-ITD/FLT3wt<0.5 vs FLT3-ITD/FLT3wt⩾0.5: 218.9 vs 221.4, n.s.). However, subdivision of patients according to their NPM1 and FLT3-ITD mutational status revealed significantly lower BAALC expression in the group of patients with NPM1mut and FLT3wt or FLT3-ITD/FLT3wt<0.5 expression compared to patients with FLT3-ITD/FLT3wt⩾0.5, irrespective of their NPM1 mutational status (39.4 vs 374.8, P<0.001). In contrast, mean expression levels of BAALC in patients concomitantly harboring MLL-PTD were comparable to those of MLL-PTD-negative patients (217.9 vs 237.4, n.s., data not shown). When comparing BAALC expression of patients with biCEBPA to that of patients with monoCEBPA or CEBPAwt, the mean expression levels did not differ between these groups (281.0 vs 215.9, n.s.).

Figure 1.

Box plot of BAALC expression levels across different genetic subgroups. Mean %BAALC/ABL1 expression levels were compared with Student's t-test. Depicted are BAALC expression levels in RUNX1, WT1, NPM1, FLT3-ITD, NPM1&FLT3-ITD, and CEBPA mutated and wt cases separately. Also mean %BAALC/ABL1 values are given in the heading of the respective genetic subgroups.

BAALC expression as a prognostic marker

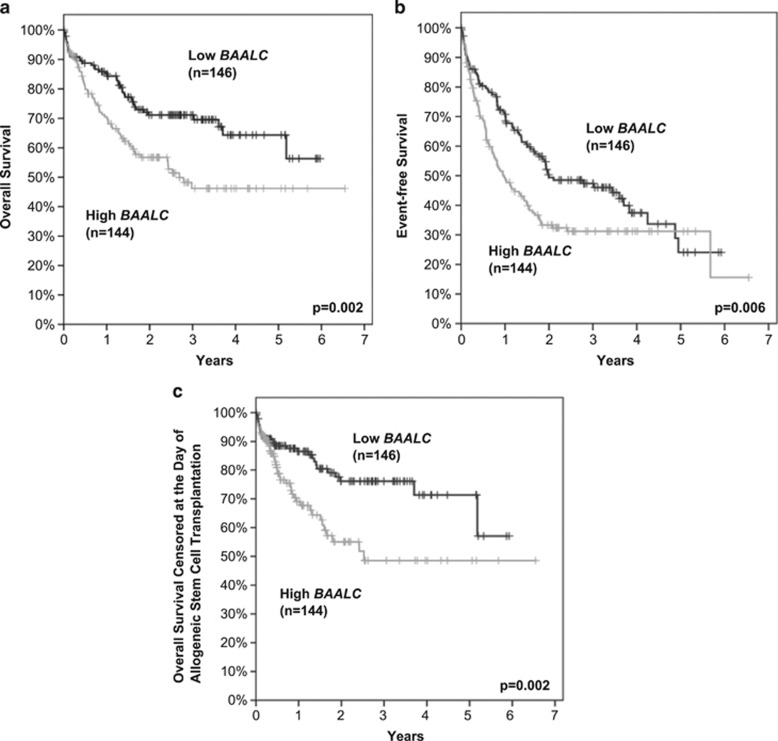

Patients with high BAALC expression had significantly shorter EFS and OS (Figures 2a and b). The estimated 3-year EFS rates for high and low BAALC expressers were 31.2 and 47.4% (P=0.006) and the estimated 3-year OS rates for the two groups were 46.2 and 71.1% (P=0.002), respectively. Additionally, when analyzing OS and censoring patients at the day of transplantation, thereby eliminating the effect of allogeneic SCT (OSTXcens) high BAALC expression was related to considerably shorter survival (OSTXcens at 3 years: 48.6 vs 76.1%, P=0.002; Figure 2c).

Figure 2.

Outcome of 290 intensively treated CN-AML patients aged younger than 65 years with respect to BAALC expression. The median expression level was used to dichotomize the total patient cohort into low (black) and high (gray) BAALC expressers. (a) Overall survival; at 3 years: 46.2 vs 71.1%, P=0.002, (b) event-free survival; at 3 years: 31.2 vs 47.4%, P=0.006, (c) overall survival censored at the day of allogeneic SCT; at 3 years: 48.6 vs 76.1%, P=0.002.

Univariate- and multivariate analysis

As we observed significant correlations of BAALC expression with several molecular markers, we performed multivariate analysis to clarify whether BAALC expression is an independent prognostic factor in CN-AML (Table 2). In univariate analysis, a significant negative impact on OS was shown for higher age (P<0.001, hazard ratio (HR) per decade: 1.37), higher WBC count (P<0.001, HR per 10 × 109/l: 1.07), ASXL1mut (P=0.047, HR: 2.18), FLT3-ITD/FLT3wt⩾0.5 (P<0.001, HR: 2.54), MLL-PTD (P<0.001, HR: 2.77), WT1mut (P=0.029, HR: 1.96) and high BAALC expression (P=0.002, HR low vs high BAALC expression: 1.85). A significant negative impact on EFS was found for higher age (P=0.001, HR per decade: 1.24), higher WBC count (P<0.001, HR per 10 × 109/l: 1.05), FLT3-ITD/FLT3wt⩾0.5 (P<0.001, HR: 1.96), WT1mut (P<0.001, HR: 2.58) and high BAALC expression (P=0.006, HR low vs high BAALC expression: 1.53). When censoring the effect of allogeneic SCT the following parameters revealed a negative impact on OSTXcens: higher age (P<0.001, HR per decade: 1.50), higher WBC count (P<0.001, HR per 10 × 109/l: 1.11), ASXL1mut (P=0.009, HR: 2.83), FLT3-ITD/FLT3wt⩾0.5 (P<0.001, HR: 3.29), IDH2R140mut (P=0.029, HR: 1.89), MLL-PTD (P=0.001, HR: 3.25), WT1mut (P=0.024, HR: 2.26) and high BAALC expression (P=0.002, HR low vs high BAALC expression: 2.10).

Table 2. Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses on OS, EFS and OSTXcens.

| Parameter |

Overall survival |

Event-free survival |

OSTXcens |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Univariate |

Multivariate |

Univariate |

Multivariate |

Univariate |

Multivariate |

|||||||

| HR | P | HR | P | HR | P | HR | P | HR | P | HR | P | |

| Age | 1.37a | <0.001 | 1.45a | <0.001 | 1.24a | 0.001 | 1.31a | <0.001 | 1.50a | <0.001 | 1.57a | 0.001 |

| WBC count | 1.07b | <0.001 | 1.06b | <0.001 | 1.05b | <0.001 | 1.03b | 0.013 | 1.11b | <0.001 | 1.10b | <0.001 |

| ASXL1mut | 2.18 | 0.047 | 2.01 | 0.142 | 1.63 | 0.155 | — | — | 2.83 | 0.009 | 2.91 | 0.038 |

| FLT3-ITDc | 1.97 | 0.001 | n.a. | n.a. | 1.38 | 0.045 | n.a. | n.a. | 2.78 | <0.001 | n.a. | n.a. |

| NPM1mut and FLT3wt or FLT3-ITD/FLT3wt<0.5 | 0.47 | <0.001 | n.a. | n.a. | 0.67 | 0.009 | n.a. | n.a. | 0.36 | <0.001 | n.a. | n.a. |

| FLT3-ITD/FLT3wt⩾0.5 | 2.54 | <0.001 | 1.65 | 0.061 | 1.96 | <0.001 | 1.61 | 0.030 | 3.29 | <0.001 | 2.08 | 0.014 |

| IDH2R140 | 1.36 | 0.247 | — | — | 1.19 | 0.422 | — | — | 1.89 | 0.029 | 2.15 | 0.022 |

| MLL-PTD | 2.77 | <0.001 | 2.23 | 0.017 | 1.58 | 0.102 | — | — | 3.25 | 0.001 | 2.56 | 0.020 |

| WT1mut | 1.96 | 0.029 | 2.11 | 0.042 | 2.58 | <0.001 | 2.52 | 0.001 | 2.26 | 0.024 | 2.85 | 0.013 |

| High BAALC expression | 1.85 | 0.002 | 1.77 | 0.013 | 1.53 | 0.006 | 1.59 | 0.011 | 2.10 | 0.002 | 2.00 | 0.018 |

Abbreviations: BAALC, brain and acute leukemia, cytoplasmic; EFS, event-free survival; FLT3-ITD, FLT3 internal tandem duplication; HR, hazard ratio; MLL-PTD, partial tandem duplications within the MLL gene; n.a., not applicable; OS, overall survival; OSTXcens, overall survival censored at the day of allogeneic SCT; SCT, stem cell transplantation; wt, wild type.

Per 10 years of increase.

Per 10 × 109/l.

Not analyzed because FLT3-ITD was analyzed according to its mutation load.

In multivariate analysis, high BAALC expression revealed an independent prognostic impact on OS (P=0.013, HR: 1.77), EFS (P=0.011, HR: 1.59) and also on OSTXcens (P=0.018, HR: 2.00). In addition, age (P<0.001, HR per decade: 1.45), higher WBC count (P<0.001, HR per 10 × 109/l: 1.06), MLL-PTD (P=0.017, HR: 2.23) and WT1mut (P=0.042, HR: 2.11) had an independent impact on OS. In multivariate analysis for EFS, additional independent factors were age (P<0.001, HR per decade: 1.31), higher WBC count (P=0.013, HR per 10 × 109/l: 1.03), FLT3-ITD/FLT3wt⩾0.5 (P=0.030, HR: 1.61) and WT1mut (P=0.001, HR: 2.52). In multivariate analysis for OSTXcens, additional independent factors were age (P=0.001, HR per decade: 1.57), higher WBC count (P<0.001, HR per 10 × 109/l: 1.10), ASXL1mut (P=0.038, HR: 2.91), FLT3-ITD/FLT3wt⩾0.5 (P=0.014, HR: 2.08), IDH2R140mut (P=0.022, HR: 2.15), MLL-PTD (P=0.020, HR: 2.56) and WT1mut (P=0.013, HR: 2.85).

Evaluation of BAALC expression for disease monitoring

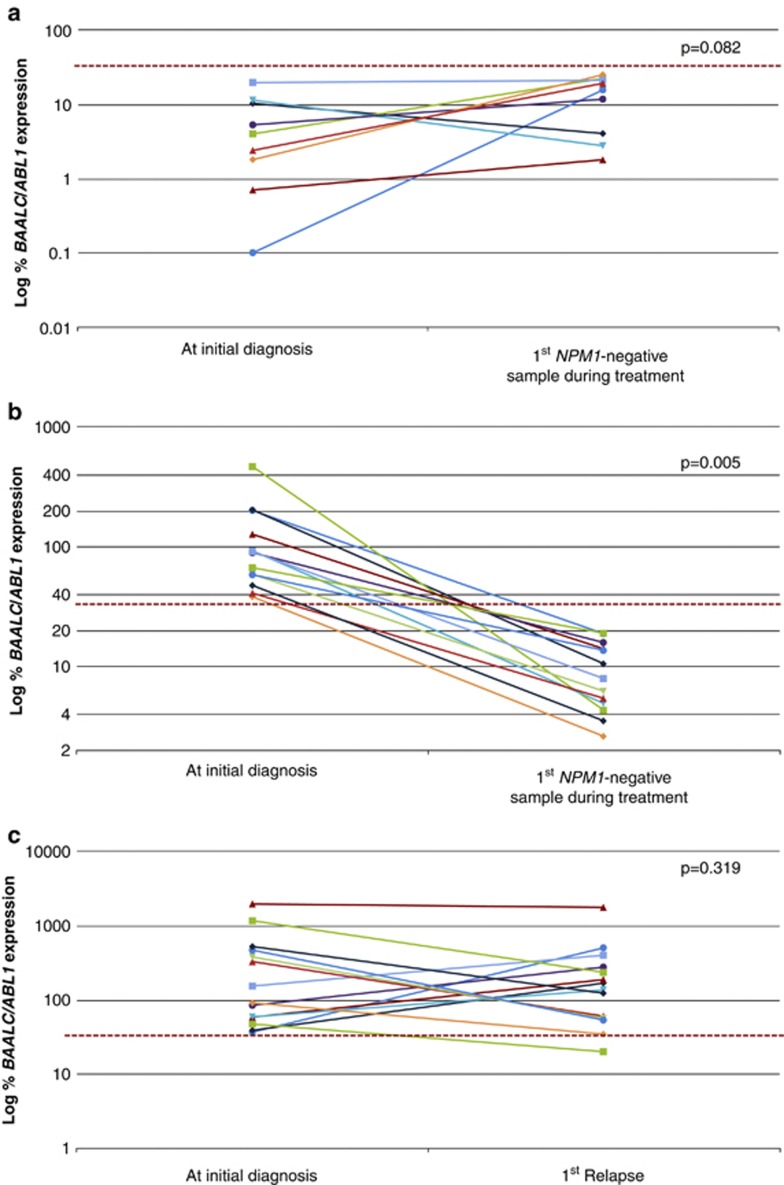

Before evaluating the utility of BAALC overexpression as a novel biomarker for molecular monitoring, we performed experiments to exclude BAALC expression in general from being modulated by the treatment regimen. For this purpose, serial follow-up samples of nine patients showing an NPM1mut and low BAALC expression at diagnosis were analyzed. BAALC expression levels of the diagnostic samples were correlated with those of the first sample showing complete molecular remission (CMR) defined by NPM1 mutational status. In these nine patients, no significant difference of BAALC expression levels could be observed during treatment (mean±s.e.m. at diagnosis vs mean±s.e.m. at first CMR: 6.2±2.2 vs 13.8±3.0, P=0.082; Figure 3a). In contrast, in 13 patients with BAALC overexpression at diagnosis a strong reduction in mean BAALC expression levels at first CMR could be shown (mean±s.e.m. at diagnosis vs mean±s.e.m. at first CMR: 121.5±32.5 vs 9.7±1.6, P=0.005; Figure 3b). Furthermore, in the patients with low BAALC expression at diagnosis the detected BAALC expression levels remained below the previously defined cutoff. These results indicate that BAALC expression is not generally modulated by the treatment.

Figure 3.

Analysis of 36 diagnostic and 36 follow-up samples. (a) Nine NPM1mut patients with low BAALC expression at diagnosis, (b) 13 patients with NPM1mut and high BAALC expression levels at diagnosis. Figures (a) and (b) represent BAALC expression levels at diagnosis and at first CMR defined by undetectable NPM1mut. (c) Fourteen patients with high BAALC expression at diagnosis and samples of first relapse available. P-values were derived by paired Student's t-test. The dashed line represents the median BAALC expression level (33.1% BAALC/ABL1) of the diagnostic cohort.

Next, we investigated the stability of BAALC overexpression between diagnosis and relapse in paired samples of 14 patients. As demonstrated in Figure 3c, no significant difference in mean BAALC expression levels between both time points was found (mean±s.e.m. at diagnosis vs mean±s.e.m. at relapse: 384.4±146.6 vs 286.3±119.5, P=0.319). These results also indicate that the expression levels of BAALC at relapse were in the range of those at diagnosis. Moreover in 4 of these 14 patients a characterization according to cytomorphologic criteria during follow-up was available. In these four cases a molecular relapse was detected, based on elevated BAALC expression levels (32.4–65.5%BAALC/ABL1) within 37–149 days before morphological relapse.

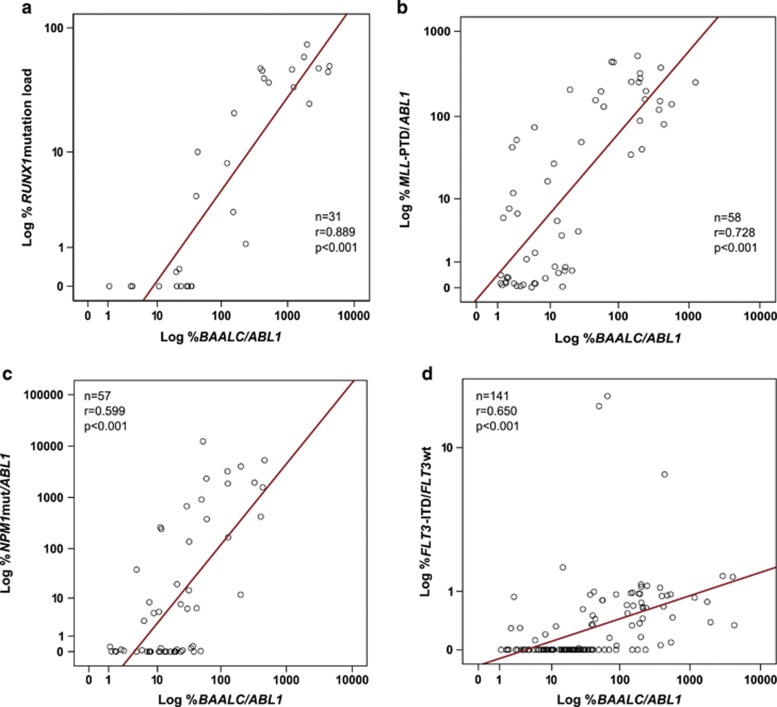

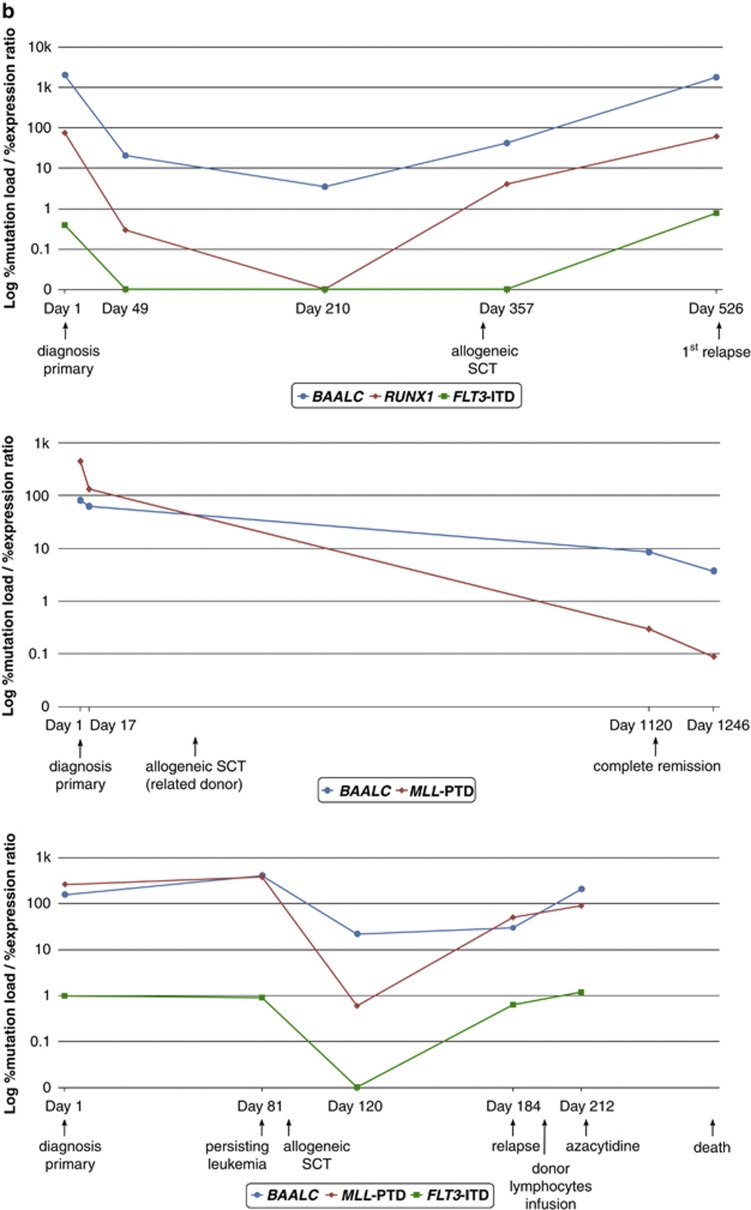

To further evaluate the utility of BAALC expression to monitor therapy response, BAALC expression was analyzed in 358 diagnostic and follow-up samples of 57 patients showing high BAALC expression at diagnosis. BAALC expression levels were correlated with either the mutational status or the expression levels of other follow-up markers: FLT3-ITD, MLL-PTD, NPM1mut and RUNX1mut. BAALC expression at diagnosis ranged from 11.3 to 8019.9 (median: 459.8) in patients with RUNX1mut and from 1.5 to 1177.7 (median: 140.4) in patients with MLL-PTD. Initial BAALC expression in NPM1-mutated patients ranged from 0.1 to 806.2 (median: 16.1) and in FLT3-ITD-positive patients from 0.4 to 4256.3 (median: 44.3). Spearman's rank correlation coefficient revealed a strong correlation of mutational status of %RUNX1 and %MLL-PTD/ABL1 with %BAALC/ABL1 levels (r=0.889, P<0.001 and r=0.728, P<0.001, Figures 4a and b). But, less consistency in correlation of NPM1 mutation load and FLT3-ITD expression with %BAALC/ABL1 levels (r=0.448, P<0.001 and r=0.445, P<0.001) was found. These conflicting results might be due to the lower overall BAALC expression levels in the NPM1mut group at diagnosis, which only allows detection of BAALC expression during follow-up within one log range (Figure 1). To confirm this hypothesis, in a second analysis only patients with high %BAALC/ABL1 levels (⩾100; ⩾200; ⩾300) at diagnosis were correlated with mutational status of NPM1. This comparison revealed a good correlation of the %BAALC/ABL1 levels with the NPM1 mutation load (levels ⩾100: r=0.599, P<0.001, Figure 4c and levels ⩾200: n=38, r=0.601, P<0.001; levels ⩾300: n=24, r=0.698, P<0.001). FLT3-ITD mutational load was detected by Genescan analysis, which is a semi-quantitative approach. Furthermore, copy-number neutral loss of heterozygosity at 13q, frequently occurring in AML, results in the prevalence of the FLT3-ITD mutant allele over the FLT3wt allele. Both influences the linearity and therefore the precision of the FLT3-ITD expression analysis and might account for the constrained correlation of %BAALC/ABL1 with FLT3-ITD expression. Consequently, exclusion of loss of heterozygosity cases showed good correlation of %BAALC/ABL1 with FLT3-ITD expression (r=0.650, P<0.001, Figure 4d).

Figure 4.

Correlation of BAALC expression levels with mutation load or expression levels of different mutations. (a) RUNX1 mutation load, (b) %MLL-PTD/ABL1 expression, (c) %NPM1/ABL1 mutation load (only patients with %BAALC/ABL1 levels⩾100) and (d) FLT3-ITD (excluding cases showing loss of heterozygosity (LOH) by loss of FLT3wt).

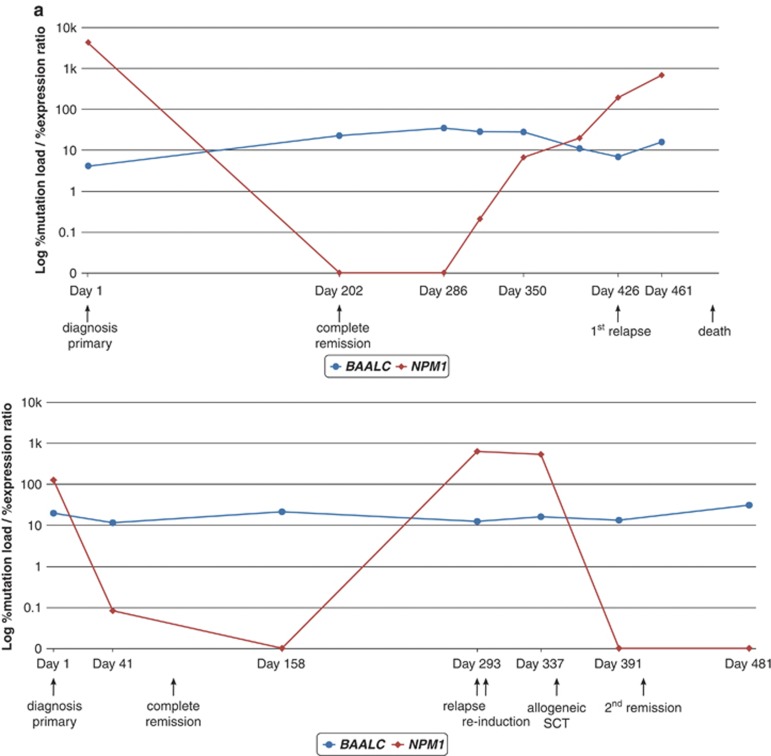

Next, single patients were analyzed serially during follow-up. The molecular courses of three patients with high and two patients with low BAALC expression which were also monitored for FLT3-ITD, MLL-PTD, NPM1mut or RUNX1mut are depicted in Figure 5. As expected, in low expressers the %BAALC/ABL1 is stable during follow-up (Figure 5a). In contrast, in high expressers the %BAALC/ABL1 during follow-up correlated well with the kinetics of FLT3-ITD, MLL-PTD and/or RUNX1mut (Figure 5b).

Figure 5.

Clinical course of (a) two patients with NPM1mut (red) and low BAALC expression levels (blue) at diagnosis showing no difference in BAALC expression levels during the cause of the disease and (b) three patients with high BAALC expression levels (blue) at diagnosis concomitantly carrying FLT3-ITD (green), MLL-PTD and/or RUNX1mut (red) showing good concordance of these markers during follow-up.

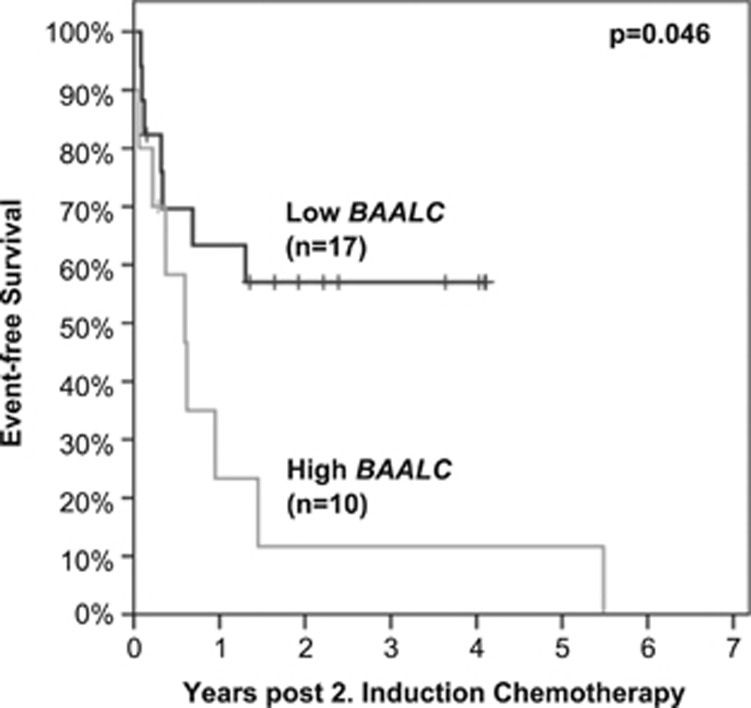

Prognostic significance of BAALC expression during follow-up

To investigate the predictive value of BAALC expression levels during follow-up, BAALC expression was analyzed in samples following the second cycle of induction chemotherapy of 27 patients with high BAALC expression levels at diagnosis. To separate low from high BAALC expression in this follow-up analysis, the initial cutoff (median expression of diagnostic cohort=33.1%BAALC/ABL1) was used. During follow-up, 37% (10/27) of the patients had high BAALC expression levels, while 63% (17/27) of the patients exhibited low BAALC expression levels. Kaplan–Meier analysis revealed that low BAALC expression after the second cycle of induction chemotherapy was associated with higher EFS rates compared with high BAALC expression (median: not reached vs 218 days, P=0.046, Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Kaplan–Meier plot of patients achieving low vs high BAALC expression levels after second cycle of induction chemotherapy. To separate low (black) from high (gray) BAALC expressers the median BAALC expression level (33.1%BAALC/ABL1) of the diagnostic cohort was used. This resulted in significant differences in EFS (median: not reached vs 218 days, P=0.046).

Discussion

In this study, we investigated the prognostic value of BAALC expression levels on clinical outcome in the light of other currently relevant molecular prognosticators. Furthermore, we examined the utility of BAALC expression as a marker for detection of residual disease in CN-AML.

Previous studies have addressed the question whether to use BM or PB to analyze BAALC expression in AML. A strong correlation of BAALC expression levels in both specimens from AML patients has been reported.41, 42 This correlation was confirmed in seven of our patients from which pretreatment blood and marrow samples were available (data not shown) and therefore a combination of both specimens has been analyzed in this study.

Different associations of altered BAALC expression to specific molecular aberrations have been shown. For instance, high BAALC expression has been demonstrated to correlate with the mutation status of FLT3-ITD, CEBPA, MLL-PTD as well as to NPM1wt.13, 14, 15, 20 We here addressed the question whether BAALC expression also associates with recently described biomarkers such as ASXL1, IDH1R132, IDH2R140, IDH2R172, NRAS, RUNX1, WT1 and TET2. In our cohort of 326 CN-AML patients, the correlation of high BAALC expression with FLT3-ITD, CEBPAmut, MLL-PTD and NPM1wt could be confirmed. Moreover, we were able to show a strong correlation of high BAALC expression with the recently described prognosticators WT1mut, RUNX1mut, biCEBPA and also to IDH2R172mut, while no correlations to ASXL1mut, IDH1R132mut, IDH2R140mut or TET2mut were found.

An association of high BAALC expression with WT1mut has recently been described in a cohort of 196 young CN-AML patients by Paschka et al.43 Here, we were able to corroborate this correlation of BAALC expression levels with the mutational status of WT1. This specific association might be age dependent since no correlation of high BAALC expression with WT1mut was found in a cohort of 158 CN-AML patients aged 60 years or older,20 which could also be confirmed in our cohort, when analyzing a fairly small subset of 77 patients of at least 60 years of age (data not shown).

Furthermore, we show a strong correlation of BAALC expression with RUNX1mut, with 31 of 33 RUNX1-positive patients showing high BAALC expression. An association of RUNX1mut and high BAALC expression has also been shown in gene expression profiling experiments in a group of 93 CN-AML patients.44 Moreover, recently Eisfeld et al.45 reported two SNPs within exon 1 and 5′UTR of BAALC creating binding sites for RUNX1 as a predisposing genetic factor to overexpression of the BAALC gene. But, so far, it remains elusive, whether these SNPs also account for BAALC overexpression in RUNX1-mutated patients, since at least some RUNX1mut have been reported to lead to a loss of protein function by disruption of the DNA binding ability.46 A correlation of high BAALC expression with distinct RUNX1mut was not found in our cohort (data not shown).

CEBPA mutations have been shown to be associated with favorable outcome47 and more recent studies suggest that this applies only to patients with biCEBPA.48 Here, we show that high BAALC expression correlates with biCEBPA. However, when analyzing BAALC expression as a continuous variable, no significant difference in mean BAALC expression levels between biCEBPA and monoCEBPA or wt patients could be observed. Due to the restricted number of biCEBPA-mutated patients with high BAALC expression in our cohort it has to be corroborated in a larger cohort, whether biCEBPA patients with high BAALC expression levels define a separate prognostic group within the CN-AML.

Despite the specific correlation of altered BAALC expression with different well-defined molecular prognosticators, we were interested whether BAALC expression is only a surrogate marker or an independent factor for the prognostic allocation of intensively treated CN-AML patients. In our study, high BAALC expression presented with independent impact on EFS and OS. This is in part in accordance with previous studies where high BAALC expression was independently associated with lower CR rates,14, 20 shorter DFS20 and shorter OS,13, 14, 20 while some studies could not confirm this independent prognostic effect of BAALC expression on survival.15, 49 However, none of the aforementioned studies included the newly described prognosticators such as RUNX1 or WT1, as we did, underlining the independent prognostic impact of high BAALC expression in CN-AML.

The pathogenetic impact of high BAALC expression and its association with different adverse prognosticators in the evolution of leukemia remains elusive, since neither the role of BAALC nor the role of most of the concomitant mutations in leukemogenesis have been fully clarified. A study of Heuser et al.21 has shown that BAALC expression hinders cell differentiation, but does not promote cell proliferation. On the basis of the two-hit hypothesis,50 a second event that induces proliferation would be indispensable for the onset of leukemia. At least for FLT3-ITD a proliferation promoting effect has been confirmed.50 Therefore, the correlating mutations might synergize with BAALC expression in the development of AML.

Furthermore, BAALC overexpression seems to be specifically associated with certain subtypes of leukemia characterized by specific molecular features, since we found strong correlations with mutations in transcription factors and genes that induce proliferation, but no correlation with mutations in epigenetic regulators or genes associated with epigenetic pathways such as TET2, ASXL1 and the IDH genes.51, 52, 53 An exception is IDH2R172, which is correlated with high BAALC expression. Beside the fact that this result has to be interpreted with caution due to the small number of IDH2R172-mutated patients, it has already been described that this specific mutation differs in prognosis and appearance as compared with IDH1R132 and IDH2R140.54

Many studies have shown that assessment of MRD is of great importance for risk stratification and early detection of relapse in AML.24, 25 Most frequently, monitoring of PCR-based MRD was restricted to patients carrying specific genetic markers such as fusion genes55, 56, 57 and gene mutations.58, 59 However, many patients lack such markers amenable to sensitive detection by PCR. For this reason, it is crucial to identify molecular targets that are appropriate to measure MRD in the majority of patients with AML. Up to now, only one study has addressed the molecular analysis of BAALC expression as a marker for molecular monitoring.42 This study indicated the applicability of BAALC as an MRD target in a cohort of 34 AML and 11 acute lymphoblastic leukemia patients.

In our study, we were able to validate the applicability of BAALC expression as a marker for detection of residual disease in 57 patients. Parallel analysis of BAALC expression in a total of 358 diagnostic and follow-up samples revealed a significant correlation of BAALC expression levels with FLT3-ITD, MLL-PTD, NPM1mut and RUNX1mut, all of them being well-known MRD markers.58, 59, 60 Moreover, in 14 patients with matched samples at diagnosis and relapse mean BAALC expression levels at first relapse were comparable to that of the diagnostic samples, indicating BAALC expression as a stable marker.

Depending on diagnostic BAALC expression levels, with our assay up to 2.4 log differences were assessable. Therefore, the sensitivity of our assay is comparable to that of MLL-PTD and FLT3-ITD detection assays. Using BAALC expression as a marker for molecular monitoring in patients with high initial %BAALC/ABL1 levels of above 100 would make 28% (91/326) of our CN-AML patients accessible to molecular monitoring. A full molecular characterization according to the four MRD markers, FLT3-ITD, MLL-PTD, NPM1mut and RUNX1mut, was available for all of these 91 patients indicating a lack of mutation in 29% (26/91) of these cases with respect to the four established markers. Thus, despite good genetic characterization 29% of these patients lack a mutation-based MRD target and would benefit from molecular monitoring using a quantitative BAALC expression assay.

Recently, detecting RUNX1mut by next-generation deep sequencing has been proposed as a stable and sensitive method to monitor RUNX1mut during the cause of the disease.60 However, this method is still quite cost intensive and not yet accessible to many diagnostics laboratories. In this respect, the analysis of BAALC expression by qPCR could be a suitable substitute to detected MRD in patients having RUNX1mut and high BAALC expression at diagnosis. In view of this fact, up to 43% (39/91) of patients with high initial %BAALC/ABL1 levels could benefit from the quantitative assessment of BAALC expression during the course of the disease.

Furthermore, we were able to show that a reduction in BAALC expression levels below the initially defined cutoff after the second cycle of chemotherapy resulted in better EFS. This not only indicates the prognostic impact of BAALC detection for residual disease, but also further validates the cutoff set at diagnosis. However, in prospective studies larger numbers of patients should be analyzed to strengthen these data.

Taken together, our results reveal particular associations between BAALC expression and mutations in CN-AML. Despite these correlations, high BAALC expression was an independent predictor of shorter EFS and OS. Moreover, our data demonstrate the applicability of BAALC expression as a target for monitoring of residual disease. Therefore, future prospective studies should corroborate the prognostic impact of BAALC-based monitoring, since up to 43% of the CN-AML patients with high BAALC expression (%BAALC/ABL>100) at diagnosis might benefit from BAALC detection during the course of their disease. Accordingly, our data may strongly affect the collective use of molecular markers in risk assessment and disease monitoring of CN-AML.

Acknowledgments

We thank all co-workers in our laboratory for their excellent technical assistance and all patients and clinicians for their participation in this study. Especially, the technical assistance of Louisa Noël and Madlen Ulke, who performed a large part of BAALC-specific qPCR analyses, is greatly appreciated.

SS, WK, CH and TH are part owners of the MLL Munich Leukemia Laboratory. SW, TA, FD, SJ, NN, CE, AF, AK and MM are employed by the MLL Munich Leukemia Laboratory.

Footnotes

Author contributions

SW investigated BAALC expression, analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. SJ and FD contributed in writing the manuscript. CE, AF and MM did sequence analysis of ASXL1. AK performed next-generation sequencing. NN contributed to the data illustration. CH was responsible for chromosome banding analysis. WK was responsible for immunophenotyping. TH was responsible for cytomorphologic analysis. TA collected and analyzed clinical data. SS was the principle investigator of the study. All authors read and contributed to the final version of the manuscript.

References

- Mrozek K, Heerema NA, Bloomfield CD. Cytogenetics in acute leukemia. Blood Rev. 2004;18:115–136. doi: 10.1016/S0268-960X(03)00040-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcucci G, Haferlach T, Dohner H. Molecular genetics of adult acute myeloid leukemia: prognostic and therapeutic implications. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:475–486. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.30.2554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falini B, Mecucci C, Tiacci E, Alcalay M, Rosati R, Pasqualucci L, et al. Cytoplasmic nucleophosmin in acute myelogenous leukemia with a normal karyotype. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:254–266. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verhaak RG, Goudswaard CS, van PW, Bijl MA, Sanders MA, Hugens W, et al. Mutations in nucleophosmin (NPM1) in acute myeloid leukemia (AML): association with other gene abnormalities and previously established gene expression signatures and their favorable prognostic significance. Blood. 2005;106:3747–3754. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-05-2168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnittger S, Schoch C, Kern W, Mecucci C, Tschulik C, Martelli MF, et al. Nucleophosmin gene mutations are predictors of favorable prognosis in acute myelogenous leukemia with a normal karyotype. Blood. 2005;106:3733–3739. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-06-2248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dohner K, Schlenk RF, Habdank M, Scholl C, Rucker FG, Corbacioglu A, et al. Mutant nucleophosmin (NPM1) predicts favorable prognosis in younger adults with acute myeloid leukemia and normal cytogenetics: interaction with other gene mutations. Blood. 2005;106:3740–3746. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-05-2164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnittger S, Bacher U, Kern W, Alpermann T, Haferlach C, Haferlach T. Prognostic impact of FLT3-ITD load in NPM1 mutated acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia. 2011;25:1297–1304. doi: 10.1038/leu.2011.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wouters BJ, Lowenberg B, Erpelinck-Verschueren CA, van Putten WL, Valk PJ, Delwel R. Double CEBPA mutations, but not single CEBPA mutations, define a subgroup of acute myeloid leukemia with a distinctive gene expression profile that is uniquely associated with a favorable outcome. Blood. 2009;113:3088–3091. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-09-179895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnittger S, Kinkelin U, Schoch C, Heinecke A, Haase D, Haferlach T, et al. Screening for MLL tandem duplication in 387 unselected patients with AML identify a prognostically unfavorable subset of AML. Leukemia. 2000;14:796–804. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2401773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnittger S, Dicker F, Kern W, Wendland N, Sundermann J, Alpermann T, et al. RUNX1 mutations are frequent in de novo AML with noncomplex karyotype and confer an unfavorable prognosis. Blood. 2011;117:2348–2357. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-11-255976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaidzik VI, Bullinger L, Schlenk RF, Zimmermann AS, Rock J, Paschka P, et al. RUNX1 mutations in acute myeloid leukemia: results from a comprehensive genetic and clinical analysis from the AML Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:1364–1372. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.30.7926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnittger S, Eder C, Jeromin S, Alpermann T, Fasan A, Grossmann V, et al. ASXL1 exon 12 mutations are frequent in AML with intermediate risk karyotype and are independently associated with an adverse outcome. Leukemia. 2013;27:82–91. doi: 10.1038/leu.2012.262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldus CD, Thiede C, Soucek S, Bloomfield CD, Thiel E, Ehninger G. BAALC expression and FLT3 internal tandem duplication mutations in acute myeloid leukemia patients with normal cytogenetics: prognostic implications. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:790–797. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.6253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langer C, Radmacher MD, Ruppert AS, Whitman SP, Paschka P, Mrozek K, et al. High BAALC expression associates with other molecular prognostic markers, poor outcome, and a distinct gene-expression signature in cytogenetically normal patients younger than 60 years with acute myeloid leukemia: a Cancer and Leukemia Group B (CALGB) study. Blood. 2008;111:5371–5379. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-11-124958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metzeler KH, Dufour A, Benthaus T, Hummel M, Sauerland MC, Heinecke A, et al. ERG expression is an independent prognostic factor and allows refined risk stratification in cytogenetically normal acute myeloid leukemia: a comprehensive analysis of ERG, MN1, and BAALC transcript levels using oligonucleotide microarrays. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:5031–5038. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.5328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cilloni D, Renneville A, Hermitte F, Hills RK, Daly S, Jovanovic JV, et al. Real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction detection of minimal residual disease by standardized WT1 assay to enhance risk stratification in acute myeloid leukemia: a European LeukemiaNet study. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:5195–5201. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.4865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barjesteh van Waalwijk van Doorn-Khosrovani S, Erpelinck C, van Putten WL, Valk PJ, van der Poel-van de Luytgaarde S, Hack R, et al. High EVI1 expression predicts poor survival in acute myeloid leukemia: a study of 319 de novo AML patients. Blood. 2003;101:837–845. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-05-1459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldus CD, Tanner SM, Ruppert AS, Whitman SP, Archer KJ, Marcucci G, et al. BAALC expression predicts clinical outcome of de novo acute myeloid leukemia patients with normal cytogenetics: a Cancer and Leukemia Group B Study. Blood. 2003;102:1613–1618. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-02-0359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanner SM, Austin JL, Leone G, Rush LJ, Plass C, Heinonen K, et al. BAALC, the human member of a novel mammalian neuroectoderm gene lineage, is implicated in hematopoiesis and acute leukemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:13901–13906. doi: 10.1073/pnas.241525498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwind S, Marcucci G, Maharry K, Radmacher MD, Mrozek K, Holland KB, et al. BAALC and ERG expression levels are associated with outcome and distinct gene and microRNA expression profiles in older patients with de novo cytogenetically normal acute myeloid leukemia: a Cancer and Leukemia Group B study. Blood. 2010;116:5660–5669. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-06-290536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heuser M, Berg T, Kuchenbauer F, Lai CK, Park G, Fung S, et al. Functional role of BAALC in leukemogenesis. Leukemia. 2012;26:532–536. doi: 10.1038/leu.2011.228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta V, Tallman MS, Weisdorf DJ. Allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation for adults with acute myeloid leukemia: myths, controversies, and unknowns. Blood. 2011;117:2307–2318. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-10-265603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koreth J, Schlenk R, Kopecky KJ, Honda S, Sierra J, Djulbegovic BJ, et al. Allogeneic stem cell transplantation for acute myeloid leukemia in first complete remission: systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective clinical trials. JAMA. 2009;301:2349–2361. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ommen HB, Schnittger S, Jovanovic JV, Ommen IB, Hasle H, Ostergaard M, et al. Strikingly different molecular relapse kinetics in NPM1c, PML-RARA, RUNX1-RUNX1T1, and CBFB-MYH11 acute myeloid leukemias. Blood. 2010;115:198–205. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-04-212530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hokland P, Ommen HB. Towards individualized follow-up in adult acute myeloid leukemia in remission. Blood. 2011;117:2577–2584. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-09-303685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez HF, Sun Z, Yao X, Litzow MR, Luger SM, Paietta EM, et al. Anthracycline dose intensification in acute myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1249–1259. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0904544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnett AK, Hills RK, Milligan DW, Goldstone AH, Prentice AG, McMullin MF, et al. Attempts to optimize induction and consolidation treatment in acute myeloid leukemia: results of the MRC AML12 trial. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:586–595. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.9088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett JM, Catovsky D, Daniel MT, Flandrin G, Galton DA, Gralnick HR, et al. Proposals for the classification of the acute leukaemias. French-American-British (FAB) co-operative group. Br J Haematol. 1976;33:451–458. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1976.tb03563.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arber DA, Brunning RD, Le Beau MM, Falini B, Vardiman J, Porwit A, et al. Acute myeloid leukemia with recurrent genetic abnormalitiesIn: Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL, Jaffe ES, Pileri SA, Stein H, et al (eds).WHO Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC): Lyon; 2008110–123. [Google Scholar]

- Haferlach T, Kern W, Schoch C, Hiddemann W, Sauerland MC. Morphologic dysplasia in acute myeloid leukemia: importance of granulocytic dysplasia. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:3004–3005. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.99.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitelman F.(ed) ISCN (1995): Guidelines for Cancer Cytogenetics, Supplement to: An International System for Human Cytogenetic Nomenclature.Karger: Basel, Switzerland; 1995 [Google Scholar]

- Kern W, Voskova D, Schoch C, Hiddemann W, Schnittger S, Haferlach T. Determination of relapse risk based on assessment of minimal residual disease during complete remission by multiparameter flow cytometry in unselected patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2004;104:3078–3085. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-03-1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kern W, Bacher U, Haferlach C, Schnittger S, Haferlach T. The role of multiparameter flow cytometry for disease monitoring in AML. Best Pract Res Clin Haematol. 2010;23:379–390. doi: 10.1016/j.beha.2010.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dicker F, Haferlach C, Kern W, Haferlach T, Schnittger S. Trisomy 13 is strongly associated with AML1/RUNX1 mutations and increased FLT3 expression in acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2007;110:1308–1316. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-02-072595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossmann V, Schnittger S, Schindela S, Klein HU, Eder C, Dugas M, et al. Strategy for robust detection of insertions, deletions, and point mutations in CEBPA, a GC-rich content gene, using 454 next-generation deep-sequencing technology. J Mol Diagn. 2011;13:129–136. doi: 10.1016/j.jmoldx.2010.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bacher U, Haferlach C, Kern W, Haferlach T, Schnittger S. Prognostic relevance of FLT3-TKD mutations in AML: the combination matters—an analysis of 3082 patients. Blood. 2008;111:2527–2537. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-05-091215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnittger S, Haferlach C, Ulke M, Alpermann T, Kern W, Haferlach T. IDH1 mutations are detected in 6.6% of 1414 AML patients and are associated with intermediate risk karyotype and unfavorable prognosis in adults younger than 60 years and unmutated NPM1 status. Blood. 2010;116:5486–5496. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-02-267955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bacher U, Haferlach T, Schoch C, Kern W, Schnittger S. Implications of NRAS mutations in AML: a study of 2502 patients. Blood. 2006;107:3847–3853. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-08-3522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohlmann A, Grossmann V, Klein HU, Schindela S, Weiss T, Kazak B, et al. Next-generation sequencing technology reveals a characteristic pattern of molecular mutations in 72.8% of chronic myelomonocytic leukemia by detecting frequent alterations in TET2, CBL, RAS, and RUNX1. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:3858–3865. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.27.1361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnittger S, Schoch C, Dugas M, Kern W, Staib P, Wuchter C, et al. Analysis of FLT3 length mutations in 1003 patients with acute myeloid leukemia: correlation to cytogenetics, FAB subtype, and prognosis in the AMLCG study and usefulness as a marker for the detection of minimal residual disease. Blood. 2002;100:59–66. doi: 10.1182/blood.v100.1.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bienz M, Ludwig M, Mueller BU, Leibundgut EO, Ratschiller D, Solenthaler M, et al. Risk assessment in patients with acute myeloid leukemia and a normal karyotype. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:1416–1424. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-1552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Najima Y, Ohashi K, Kawamura M, Onozuka Y, Yamaguchi T, Akiyama H, et al. Molecular monitoring of BAALC expression in patients with CD34-positive acute leukemia. Int J Hematol. 2010;91:636–645. doi: 10.1007/s12185-010-0550-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paschka P, Marcucci G, Ruppert AS, Whitman SP, Mrozek K, Maharry K, et al. Wilms tumor 1 gene mutations independently predict poor outcome in adults with cytogenetically normal acute myeloid leukemia: a cancer and leukemia group B study. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:4595–4602. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.2058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greif PA, Konstandin NP, Metzeler KH, Herold T, Pasalic Z, Ksienzyk B, et al. RUNX1 mutations in cytogenetically normal acute myeloid leukemia are associated with a poor prognosis and up-regulation of lymphoid genes. Haematologica. 2012;97:1909–1915. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2012.064667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisfeld AK, Marcucci G, Liyanarachchi S, Dohner K, Schwind S, Maharry K, et al. Heritable polymorphism predisposes to high BAALC expression in acute myeloid leukemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:6668–6673. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1203756109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harada Y, Harada H. Molecular pathways mediating MDS/AML with focus on AML1/RUNX1 point mutations. J Cell Physiol. 2009;220:16–20. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frohling S, Schlenk RF, Stolze I, Bihlmayr J, Benner A, Kreitmeier S, et al. CEBPA mutations in younger adults with acute myeloid leukemia and normal cytogenetics: prognostic relevance and analysis of cooperating mutations. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:624–633. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.06.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pabst T, Eyholzer M, Fos J, Mueller BU. Heterogeneity within AML with CEBPA mutations; only CEBPA double mutations, but not single CEBPA mutations are associated with favourable prognosis. Br J Cancer. 2009;100:1343–1346. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haferlach C, Kern W, Schindela S, Kohlmann A, Alpermann T, Schnittger S, et al. Gene expression of BAALC, CDKN1B, ERG, and MN1 adds independent prognostic information to cytogenetics and molecular mutations in adult acute myeloid leukemia. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2012;51:257–265. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilliland DG, Griffin JD. The roles of FLT3 in hematopoiesis and leukemia. Blood. 2002;100:1532–1542. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-02-0492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko M, Huang Y, Jankowska AM, Pape UJ, Tahiliani M, Bandukwala HS, et al. Impaired hydroxylation of 5-methylcytosine in myeloid cancers with mutant TET2. Nature. 2010;468:839–843. doi: 10.1038/nature09586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SW, Cho YS, Na JM, Park UH, Kang M, Kim EJ, et al. ASXL1 represses retinoic acid receptor-mediated transcription through associating with HP1 and LSD1. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:18–29. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.065862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Figueroa ME, Abdel-Wahab O, Lu C, Ward PS, Patel J, Shih A, et al. Leukemic IDH1 and IDH2 mutations result in a hypermethylation phenotype, disrupt TET2 function, and impair hematopoietic differentiation. Cancer Cell. 2010;18:553–567. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcucci G, Maharry K, Wu YZ, Radmacher MD, Mrozek K, Margeson D, et al. IDH1 and IDH2 gene mutations identify novel molecular subsets within de novo cytogenetically normal acute myeloid leukemia: a Cancer and Leukemia Group B study. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:2348–2355. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.27.3730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbacioglu A, Scholl C, Schlenk RF, Eiwen K, Du J, Bullinger L, et al. Prognostic impact of minimal residual disease inCBFB-MYH11-positive acute myeloid leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:3724–3729. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.28.6468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viehmann S, Teigler-Schlegel A, Bruch J, Langebrake C, Reinhardt D, Harbott J. Monitoring of minimal residual disease (MRD) by real-time quantitative reverse transcription PCR (RQ-RT-PCR) in childhood acute myeloid leukemia with AML1/ETO rearrangement. Leukemia. 2003;17:1130–1136. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2402959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisser M, Haferlach C, Hiddemann W, Schnittger S. The quality of molecular response to chemotherapy is predictive for the outcome of AML1-ETO-positive AML and is independent of pretreatment risk factors. Leukemia. 2007;21:1177–1182. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisser M, Kern W, Schoch C, Hiddemann W, Haferlach T, Schnittger S. Risk assessment by monitoring expression levels of partial tandem duplications in the MLL gene in acute myeloid leukemia during therapy. Haematologica. 2005;90:881–889. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnittger S, Kern W, Tschulik C, Weiss T, Dicker F, Falini B, et al. Minimal residual disease levels assessed by NPM1 mutation-specific RQ-PCR provide important prognostic information in AML. Blood. 2009;114:2220–2231. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-03-213389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohlmann A, Nadarajah N, Alpermann T, Grossmann V, Schindela S, Dicker F, et al. Monitoring of residual disease by next-generation deep-sequencing of RUNX1 mutations can identify acute myeloid leukemia patients with resistant disease Leukemia 2013. e-pub ahead of print 20 August 2013; doi: 10.1038/leu.2013.239 [DOI] [PubMed]