Abstract

BACKGROUND

Resuscitation centers may improve patient outcomes by achieving sufficient experience in post-resuscitation care. We analyzed the relationship between survival and hospital volume among patients suffering out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA).

METHODS

This prospective cohort investigation collected data from the Cardiac Arrest Registry to Enhance Survival database from 10/1/05-12/31/09. Primary outcome was survival to discharge. Hospital characteristics were obtained via 2005 American Hospital Association Survey. A hospital’s use of hypothermia was obtained via direct survey. To adjust for hospital-and patient-level variation, multilevel, hierarchical logistic regression was performed. Hospital volume was modeled as a categorical (OHCA/year ≤10, 11–39, ≥40) variable. A stratified analysis evaluating those with ventricular fibrillation or pulseless ventricular tachycardia (VF/VT) was also performed.

RESULTS

The cohort included 4,125 patients transported by EMS to 155 hospitals in 16 states. Overall survival to hospital discharge was 35% among those admitted to the hospital. Individual hospital rates of survival varied widely (0–100%). Unadjusted survival did not differ between the 3 hospital groups (36% for ≤10 OHCA/year, 35% for 11–39, and 36% for ≥40; p=0.75). After multilevel adjustment, differences in survival across the groups were not statistically significant. Compared to patients at hospitals with ≤10 OHCA/year, adjusted OR for survival was 1.04 (CI95 0.83–1.28) among 11–39 annual volume and 0.97 (CI95 0.73–1.30) among the ≥40 volume hospitals. Among patients presenting with VF/VT, no difference in survival was identified between the hospital groups.

CONCLUSION

Survival varied substantially across hospitals. However, hospital OHCA volume was not associated with likelihood of survival. Additional efforts are required to determine what hospital characteristics might account for the variability observed in OHCA hospital outcomes.

Keywords: Health Outcomes, Resuscitation, Out of Hospital Cardiac Arrest

INTRODUCTION

Out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) is a major public health problem with an overall mortality of approximately 90% across North America.1 Although prehospital interventions remain an important cornerstone of resuscitation, growing evidence indicates the implementation of specialized post-arrest care can positively affect outcome. In-hospital treatments such as therapeutic hypothermia and early cardiac catheterization provide opportunities to meaningfully improve survival.2–4

The impact of post-arrest care provides a rationale for the development of cardiac “resuscitation centers”, modeled after trauma centers in the United States (U.S).5–7 Some states such as Arizona and Minnesota, have either implemented or are planning to implement such systems of care. These efforts have been complemented by scientific consensus recommendations designed to inform and support the development of resuscitation centers.7 Higher patient volume is associated with improved survival in some medical and traumatic conditions and with success rates for certain surgical procedures.8–13 However, there is limited data on the role of hospital volume and OHCA survival.14–16

In this investigation, we evaluated the relationship between annual OHCA hospital volume and survival to assess the hypothesis that increasing hospital volume of OHCA patients is associated with improved survival.

METHODS

Study Design

This is a cohort investigation of prospectively collected data from the Cardiac Arrest Registry to Enhance Survival (CARES). Started in 2005, CARES is an OHCA registry that has grown each year as new communities, hospitals, and EMS agencies join. As of June 2011, CARES includes 73 EMS agencies serving 40 communities in 23 states and more than 340 hospitals. Details of the registry have been described previously.17, 18 In brief, CARES is a surveillance-based and quality assurance registry linking prehospital events with hospital care and patient outcome. The overall goal is to track the incidence of and survival from OHCA in order to identify the burden of disease as well as improve quality of care. For many EMS agencies, trained coordinators electronically enter data at regular intervals using an internet browser; for the remaining EMS agencies, selected data elements from the electronic patient care record for a case are transmitted directly into the database. Data integrity is assessed using quality measures such as range and logic checks as well as chart audits. Data collection and utilization is approved by the Emory University Institutional Review Board. The Biomedical Institutional Review Board at The Ohio State University approved the current study.

Study Population

The study population included adult patients (≥ 18 years old) who sustained an OHCA of presumed cardiac etiology, had resuscitation attempted by EMS, and were directly transported to a hospital between October 1, 2005 and December 31, 2009.19 As CARES only collects complete data on those with presumed cardiac etiology, inclusion of those with non-cardiac etiology was not possible. Such inclusion criteria is also consistent with prior literature.16 We limited the analysis to those CARES sites (N=16) that had enrolled patients for at least one year in order to derive a reasonably precise estimate of the annual number of post-OHCA patients cared for at each hospital. For the primary analysis, we excluded patients who did not survive to hospital admission to eliminate patients who may have been transported to a hospital with CPR in progress due to local EMS practices discouraging termination of resuscitation in the field. We also excluded those patients with missing data in key variables.

Key Covariates

Patient-level variables collected and available for analysis were: gender, age, race (White, Black, Hispanic, Asian, Other), presenting rhythm (ventricular fibrillation/pulseless ventricular tachycardia [VF/VT] vs. other), bystander-witnessed vs. EMS witnessed vs. non-witnessed arrest, bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR; yes/no), bystander automated external defibrillator (AED) use (yes, no), location of arrest (public vs. private), and CARES site. All variables were categorical except age which was a continuous variable.

Hospital data came from two sources: the 2005 American Hospital Association annual survey and a direct query of CARES hospitals.20 Variables from the hospital characteristics table were joined with CARES data by the hospital name. Variables analyzed for potential inclusion from the annual AHA survey in the analysis were: number of annual admissions, number of hospital beds, trauma vs. non-trauma hospital as defined by the American Hospital Association survey, teaching vs. non-teaching hospital as defined by the Council of Teaching Hospital of the Association of American Medical Colleges, and the presence of a cardiac catheterization laboratory. We contacted each CARES hospital in the summer of 2010 to determine the availability of therapeutic hypothermia on a hospital level. The use of therapeutic hypothermia on an individual patient level was not available in the CARES dataset at that time.

Annual hospital volume was classified into three categories: low (10 or less OHCA patients arriving at the ED per year), moderate (11–39 patients/year), and high (40 or greater patients/year) consistent with other recent publications evaluating the impact of volume on OHCA patients.7, 14

Outcome Measures

The main outcome was survival to hospital discharge, defined as leaving the hospital alive. Secondary outcomes included neurological status at discharge, identified by the Cerebral Performance Category (CPC) score. The CPC score is determined by hospital personnel for each patient based on patient records. “Good” neurological outcome was defined by CPC of 1 or 2 and “not good” was defined by CPC 3–5. To account for the missing neurological outcomes of some patients, those patients who had an unknown CPC score were classified as “not good”.

Data Analysis

We used descriptive statistics to assess the study population. To ascertain any differences in patient characteristics based on annual hospital volume, patients were stratified according to the three categories of volume. Continuous and categorical variables were compared via χ2 analysis, ANOVA, and Kruskal-Wallis test, where appropriate. A p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Univariate associations between the hospital-level variables and survival were assessed via logistic regression and were included in a forward, stepwise fashion. All variables with a p<0.10 or felt to be clinically-important based on published evidence were eligible for inclusion in the final model. Overall model fit was assessed via Akaike Information Criteria.

We assessed the relationship between hospital volume and survival by modeling hospital volume as a categorical variable. To account for any potential variation of patients or of variation in patient care based on the CARES site as well as the hierarchical structure of the data (i.e. patient level data, hospital level data, CARES site of event), we developed a multilevel, hierarchical logistic regression model (Proc GLIMMIX, SAS v 9.2, Cary, NC). This model accounts for individual-level and hospital-level data while simultaneously accounting for any correlated data related to the CARES site. Consequently, this approach enables assessment of how patient-level characteristics interact with hospital characteristics and how hospital characteristics interact within different sites. For the purpose of this study, data at the patient-level were considered fixed effects, while data at the hospital and site-level were considered random effects. This 3-level hierarchical model enables greater precision and more accurate adjustment for confounding with less bias than would be present with a traditional logistic regression alone.21, 22 The Cochran-Armitage test for trend was used to assess for evidence of a significant trend of survival across the low, moderate, and high hospitals.

Additionally, we also evaluated the relationship between hospital volume and survival for patients with a presenting rhythm of VF/VT who were admitted to the hospital. Moreover, as an alternative approach, we also assessed hospital volume as a continuous variable. Because we believed that annual volume may have had a non-linear relationship with mortality, we also assessed it as a fractional polynomial using a standard algorithm for selecting the best fit term (“fracpoly” in STATA v.10 StataCorp LP, College Station, TX).23, 24

To limit any potential selection bias of those cases who died in the ED, we performed a sensitivity analysis restricting to those patients who were transported with sustained ROSC (defined as prehospital ROSC ≥20 minutes) and were transported to the ED, some of whom did not survive to hospital admission, as well as all those patients transported to the ED, regardless of ROSC. In order to account for sicker patients who may be preferentially transported to larger hospitals by EMS, we also developed a propensity score for the probability of being transported to a high volume center (40 or greater per year) compared to lower volume centers. This score was built with the patient predictors that would be available to EMS providers at the time of the event. Finally, based on prior work that evaluated a different threshold of hospital volume (<20, 20–34, 35–50, >50 OHCA per year) on survival in all cardiac arrests (both OHCA as well as inhospital arrests), we also stratified hospitals based on these thresholds to determine if a different cut point may be more appropriate.25

Unless otherwise stated, SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC) was used for database management and analyses.

RESULTS

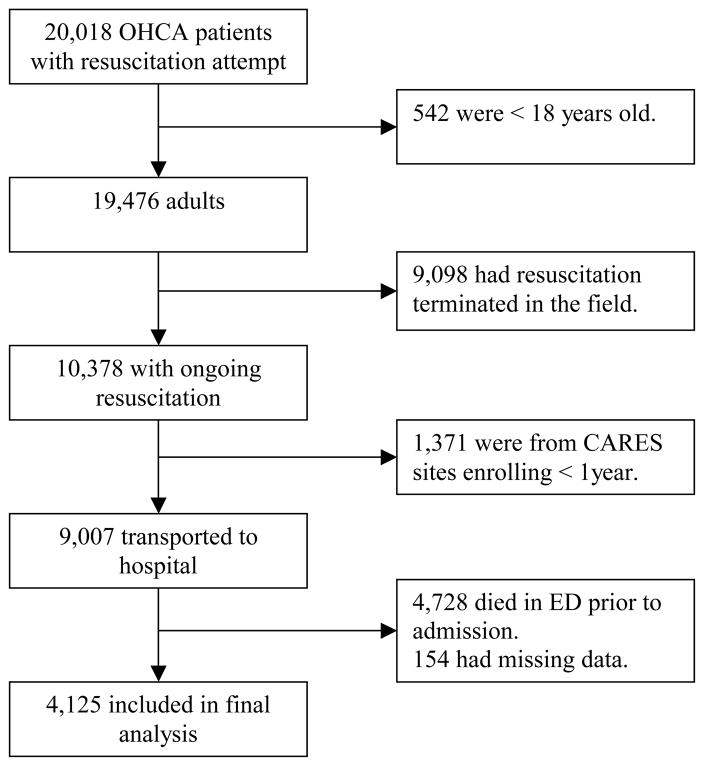

At the time of this analysis, 20,018 patients were in the CARES registry, after applying exclusion criteria, 4,125 patients were available for analysis (Figure 1). Patient characteristics are presented in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Flow Chart of Patients in Final Analysis

Table 1.

Patient Demographics

| N=4,125 (155 Hospitals) | |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Age, years | 63 (+/− 15.3) |

|

| |

| Witnessed Arrest | 2722 (66%) |

|

| |

| VFVT | 1720 (42%) |

|

| |

| Male | 2475 (60%) |

|

| |

| Public Location | 1480 (36%) |

|

| |

| Layperson CPR | 1485 (36%) |

|

| |

| Layperson AED | 124 (3%) |

| Race | |

| White | 1815 (44%) |

| Black | 990 (24%) |

| Hispanic | 289 (7%) |

| Asian | 83 (2%) |

| Other* | 948 (23%) |

|

| |

| Survival to DC | 1443 (35%) |

VFVT: Ventricular Fibrillation/Pulseless Ventricular Tachycardia

CPR: Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation

AED: Automated External Defibrillator

DC: Discharge

includes unknown race

Those patients taken to the high volume centers were more likely to be African-American and less likely to be of other race (Table 2). Hospital characteristics associated with survival were: number of annual admissions, trauma designation, presence of a cardiac catheterization lab, as well as ability of a hospital to perform therapeutic hypothermia. Those centers with the highest number of OHCA tended to be large non-profit teaching hospitals, were apt to be a trauma center, and were more likely to have therapeutic hypothermia (Table 2).

Table 2.

Demographics by Hospital Volume

| Tier 1 (10 or < arrests/year) N=697 | Tier 2 (11–39 arrests/year) N=2,500 | Tier 3 (40 or > arrests/year) N=928 | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Patient Level Data | |||

|

| |||

| Age, years (mean) | 63.7 | 62.9 | 62.6 |

|

| |||

| Witnessed Arrest | 467 (67%) | 1625 (65%) | 622 (67%) |

|

| |||

| VFVT | 319 (46%) | 1023 (41%) | 378 (41%) |

|

| |||

| Male | 397 (57%) | 1502 (60%) | 566 (61%) |

|

| |||

| Public | 251 (36%) | 902 (36%) | 343 (37%) |

|

| |||

| Layperson CPR | 244 (35%) | 901 (36%) | 334 (36%) |

|

| |||

| Layperson AED | 35 (5%) | 76 (3%) | 28 (3%) |

|

| |||

| Race | |||

| White | 328 (47%) | 1102 (44%) | 408 (44%) |

| Black | 132 (19%) | 525 (21%) | 344 (37%) |

| Hispanic | 28 (4%) | 148 (6%) | 92 (10%) |

| Asian | 7 (1%) | 50 (2%) | 19 (2%) |

| Other | 202 (29%) | 675 (27%) | 65 (7%) |

|

| |||

| Death in ED* | |||

| Transiently sustained ROSC | 196/696 (27%) | 407/2313 (18%) | 176/1062 (17%) |

| No ROSC | 1162/1359 (85%) | 2692/3286 (82%) | 95/137 (70%) |

|

| |||

| Survival to DC (all) | 251 (36%) | 876 (35%) | 334 (36%) |

|

| |||

| Survival (VFVT) | 180/321 (56%) | 595/1026 (58%) | 228/380 (60%) |

|

| |||

| Hospital Level Data | |||

|

| |||

| Hospitals | 80 | 67 | 8 |

|

| |||

| Arrests per year, median | 2.5 [1–6] | 20 [15–25] | 45 [41–51] |

|

| |||

| Annual Admits* | 12,723 [7,730–24,673] | 16,749 [11,796–24,673] | 31,797 [23,243–33,276] |

|

| |||

| Hospital Beds* | 246 [127–447] | 332 [214–415] | 602 [478–760] |

|

| |||

| For Profit | 25 (32%) | 13 (20%) | 0 (0%) |

|

| |||

| Teaching Hospital* | 17 (21%) | 20 (30%) | 4 (50%) |

|

| |||

| Trauma Hospital* | 27 (34%) | 29 (43%) | 6 (75%) |

|

| |||

| Cardiac Cath Lab* | 61 (70%) | 58 (87%) | 8 (100%) |

|

| |||

| Hospital Hypothermia* | 55 (69%) | 54 (80%) | 7 (88%) |

VFVT: Ventricular Fibrillation/Pulseless Ventricular Tachycardia

CPR: Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation

AED: Automated External Defibrillator

DC: Discharge

p<0.05

Unadjusted survival did not differ between the three hospital groups (36% for ≤10 vs. 35% for 11–39 vs. 36% for ≥40; Table 2). Individual hospital survival rates varied from 0% to 100% with a median of 34.3% [Interquartile Range 24.4%–47.1%] for all arrests and varied from 0% to 100% with a median of 58.3% [Interquartile Range 43.2%–72.4%] for VF/VT arrests. The Cochran-Armitage test for trend was non-significant (p=0.73). Survival in the eight high volume hospitals ranged from a low of 21% to a high of 48%.

In the adjusted analysis, there was no difference in survival in high volume compared to low volume centers (OR 0.97; CI95 0.73–1.30). When removing the high volume hospital with the lowest survival or the highest survival from the model, the results remained unchanged. A similar lack of benefit was observed when comparing moderate volume to low volume centers (OR 1.04; CI95 0.83–1.28). When volume was modeled continuously, no significant relationship was identified between hospital volume and survival (OR 1.00; CI95 0.99–1.00; Table 3).

Table 3.

Multilevel Hierarchical Logistic Regression Model (N=4,125)

| Odds Ratio | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| ≥40 OHCA per year | 0.97 | 0.73–1.30 |

| 11–39 OHCA per year | 1.04 | 0.83–1.28 |

| 10 or less OHCA per year | REF | REF |

|

| ||

| Age | 0.98 | 0.97–0.98 |

|

| ||

| Female | 0.89 | 0.76–1.03 |

|

| ||

| Private Location | 0.61 | 0.52–0.72 |

|

| ||

| VFVT | 4.66 | 4.01–5.42 |

|

| ||

| Witnessed Arrest | 1.93 | 1.63–2.27 |

|

| ||

| Layperson CPR | 1.03 | 0.88–1.22 |

|

| ||

| Layperson AED | 1.99 | 1.29–3.07 |

|

| ||

| Race | ||

| White | Reference | Reference |

| Black | 1.10 | 0.92–1.33 |

| Other | 1.21 | 0.98–1.49 |

|

| ||

| Trauma Hospital | 1.19 | 1.01–1.41 |

|

| ||

| Cath Lab | 1.14 | 0.88–1.49 |

|

| ||

| Hypothermia | 1.24 | 1.01–1.53 |

VFVT: Ventricular Fibrillation/Pulseless Ventricular Tachycardia

CPR: Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation

AED: Automated External Defibrillator

Sustained ROSC: Return of Spontaneous Circulation (20 minutes or greater)

Cath Lab: Cardiac Catheterization Lab

Hypothermia: Hospital Therapeutic Hypothermia Capabilities

No association between annual hospital volume and survival was observed when stratifying those with VF/VT arrest (Table 4). When analyzing good neurological outcome at discharge, 173 of the 1,458 patients (12%) had an unknown CPC score and were therefore classified as “not good”. There was no difference in the unknown CPC classifications by hospital groups (low 14% vs. moderate 11% vs. high 14%; p>0.05). There was no significant relationship between annual volume of OHCA and “good” neurological outcome. On adjusted analysis, when comparing high volume to low volume centers, patients at high volume centers were less likely to have a good neurological outcome (OR 0.38; 95% CI 0.22–0.66). However, no difference was observed when comparing moderate volume to low volume centers (OR 0.91; 95% CI 0.61–1.36).

Table 4.

Unadjusted and Adjusted Odds of Mortality for Sensitivity Analyses*

| Unadjusted Survival | Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| VFVT (n=1,720) | |||

| ≥40 OHCA per year | 60% | 0.91 | 0.61–1.35 |

| 11–39 OHCA per year | 58% | 0.96 | 0.72–1.29 |

| 10 or less OHCA per year | 56% | REF | REF |

|

| |||

| “Good” Neurological Outcome at DC (n=1,458) | |||

| ≥40 OHCA per year | 58% | 0.38 | 0.22–0.66 |

| 11–39 OHCA per year | 74% | 0.90 | 0.61–1.36 |

| 10 or less OHCA per year | 75% | REF | REF |

Adjusted for patient and hospital level variables as listed in Table 3

VFVT: Ventricular Fibrillation/Pulseless Ventricular Tachycardia

DC: Discharge

When evaluating patients with sustained ROSC who were transported to the ED, survival was similar between high and low volume centers (OR 0.94; CI95 0.70–1.27) and between moderate and low volume centers (OR 0.91; CI95 0.73–1.14). Similar findings were observed when evaluating all patients transported to the ED, regardless of ROSC. In the propensity adjusted analysis, which adjusted for transport to a high volume center as well as hospital-level characteristics (trauma center, presence of cardiac catheterization lab, presence of therapeutic hypothermia), we observed no difference in survival between high and low volume centers (OR 1.14; CI95 0.86–1.44) or between moderate and low volume centers (OR 1.11; CI95 0.94–1.39). Finally, we evaluated a higher threshold for a high volume center (>50); but only three hospitals met this criteria.25 We observed no difference when comparing any of the higher volume centers to the low volume (<20) centers. (Table 5).

Table 5.

Adjusted Odds of Mortality with Different Threshold of High Volume Hospital*

| Odds Ratio | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| >50 OHCA per year | 0.92 | 0.67–1.27 |

| 35–50 OHCA per year | 0.88 | 0.68–1.15 |

| 20–34 OHCA per year | 1.06 | 0.86–1.31 |

| 19 or less OHCA per year | REF | REF |

Adjusted for patient and hospital level variables as listed in Table 3 with results from 3 separate adjusted models displayed (i.e. <20 vs. >50, < 20 vs. 20–34, <20 vs. 35–50)

DISCUSSION

In this multicenter, multicity observational study, we did not observe a significant association between increasing OHCA hospital volume and survival in OHCAs of suspected cardiac etiology. While some hospital characteristics, such as trauma center designation and a hospital’s use of therapeutic hypothermia, were associated with improved outcomes in OHCA patients, their role with survival requires further exploration. It is possible that the impact of specific hospital attributes, such as the volume of OHCA patients, depends on many other hospital and patient-level characteristics.

There was wide variation in unadjusted survival among hospitals. This variability persisted for the entire cohort and within the hospital volume categories, suggesting that hospital factors do indeed impact the outcomes of OHCA patients. The current investigation could account for some but not all of the variability. For example, we found that a hospital designated as a trauma center and the availability of therapeutic hypothermia were both related to increased chances of survival. However, annual hospital volume, after adjusting for patient and hospital characteristics, does not appear to be one of these factors, despite the substantial variability across the hospitals in this study.

Similar results have been observed by others; similar to Melbourne, Australia, but in contrast to a study from the North American Resuscitation Outcomes Consortium, we found no difference in unadjusted mortality between the different groups of hospitals.14, 16 While the highest volume centers in the Resuscitation Outcomes Consortium sites did have the highest unadjusted survival to discharge, the differences did not persist in the adjusted analysis, suggesting that volume itself is not a key indicator of hospital care. Our study, coupled with others, suggests that hospital volume alone may not be a vital metric for identifying a capable resuscitation center. The relationship between volume and outcomes in OHCA likely is complex and requires additional investigation. It may be possible for low volume hospitals which dedicate time, resources, and personnel to deliver high quality, post-resuscitative care. 26, 27.

Rather than hospital level patient volume, it is plausible that healthcare provider level volume of OHCA patients may be an alternative marker to investigate. Prior work with other cardiovascular patient populations has suggested that low-volume physicians had higher rates of mortality, independent of the hospital volumes and that there was indeed an interaction between physician volume and hospital volume.28, 29 The experience, expertise, and interdisciplinary interactions of other hospital personnel such as nurses and rehabilitation therapists may also influence survival.30–32 Hospital “facility” factors alone may not be the best characteristics used in the potential regionalization or accreditation of specialized centers of care. Rather, it may be care by experienced providers, and the interaction and application of a multidisciplinary approach in a consistent and structured manner, that will improve the outcomes of OHCA patients.33

Direct transport of patients resuscitated from OHCA to specialized centers has been suggested to maximize survival by using the expertise presumably available at such centers.34–36 Such expertise is thought to be developed by caring for a high volume of patients. However, it is likely that an organized, structured approach is essential in order to improve survival, rather than arbitrary volume requirements alone. Trauma centers are an instructive example. Increasing evidence indicates better survival when comparing trauma centers to non-trauma centers, when comparing higher level trauma centers (i.e. level 1) to lower level trauma centers, as well as comparing higher patient volume to lower patient volume among trauma centers.11, 37–39 However, such findings were only observed after the development and implementation of such centers and their respective credentialing standards. When the elements of effective care for OHCA patients are integrated into a system that is dedicated to improving the care for this patient population then we may begin to see benefits that come with increasing institutional volumes. Such an organizational culture has been found to be present in high performing hospitals with regards to AMI and it is likely that such a paradigm shift will be equally important in OHCA patients.40

One example of a broad-based systems initiative was implemented in Arizona and has been successful in saving lives and in improving the outcomes of patients with OHCA.41 Whether such classification as an OHCA resuscitation center will also translate to more integrated care that could reveal a positive patient volume – survival relationship is not clear. If the process mirrors the trauma or stroke experience, the full benefit of a resuscitation center may require a period of time so that a center can mature and routinely achieve best practices.42, 43

An additional observation in this project is that patients cared for at large volume centers had worse neurological outcomes. One possible explanation is that tertiary bias may be present in such centers. Such bias likely contributed to the worse outcome observed. However, when evaluating the most viable OHCA patients (VF/VT), which would minimize such bias, no difference in survival was seen in higher volume centers. Additionally, it is plausible that the large volume hospitals are more likely to transfer patients who are recovering from an OHCA sooner to extended care facilities than other centers.44 As such, they may have a lower level of function upon discharge than a patient at a smaller hospital. This observation requires further exploration to validate the findings.

Our investigation has limitations. The first is we do not know how often the therapies available at a hospital, such as therapeutic hypothermia and cardiac catheterization, were actually applied to individual patients. While it is possible that patients cared for at centers that perform hypothermia did not receive it, clinical experience suggests that when such protocols are in place they are utilized appropriately.45 Some hospital characteristics, such as trauma center designation, may be a marker for more advanced care within a hospital. Future projects should evaluate how such hospital therapies individually and collectively impact survival in OHCA patients. This project is also limited by the variability in care that is provided within each city and among the various EMS systems. We attempted to control for such variability using a multilevel, random effects model. However, it is possible we were unable to completely account for potential confounding. Additionally, the CARES network only includes emergency medical services in a community. As such, transfers of patients from more remote, non-participating EMS systems and primary receiving hospitals to a CARES hospital are not included in the registry. Thus our measurement of case volume may not be completely representative of the full scope of hospital experience. However, such misclassification should impact all volumes of hospitals equally. Finally, the duration of participation in CARES by the various hospitals and sites varied from less than one to almost four years, which may have added a learning curve in data recording. We attempted to control that potential confounding by limiting the analysis to those centers that had been enrolling patients for at least one year. These limitations should be considered in the context of the study’s strengths. The study drew from a broad range of communities across the country, included thousands of patients, incorporated information about prehospital and hospital characteristics, and used advanced analytical methods to address a public health issue that has important clinical and policy implications.

CONCLUSIONS

Although survival varied considerably across hospitals, we observed that receiving hospital OHCA patient volume was not associated with survival to hospital discharge in those with presumed cardiac etiology. Additional efforts are required to determine what hospital characteristics account for the wide variability observed in hospital survival and neurological outcomes following resuscitation from out-of-hospital cardiac arrest.

Acknowledgments

We thank the more than 70 EMS Agencies and more than 340 Hospitals in the CARES registry for all that they do as well as the contributions that their hard work has contributed to this project.

Funding Source

The primary author MTC has funding support from the National Research Program of the American Heart Association (Award # 0835250N).

The Cardiac Arrest Registry to Enhance Survival (CARES) is funded by grant support from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and Emory University.

Neither funding source had any role in the study design, collection, analysis, interpretation of the data, nor the writing or submission of the manuscript.

Additional Members of the CARES Surveillance Group: Mike Levy, MD (Anchorage, Alaska); Joseph Barger, MD (Contra Costa County, California); James V. Dunford, MD (San Diego County, California); Karl Sporer, MD (San Francisco County, California); Angelo Salvucci, MD (Ventura County, California); David Ross, MD (Colorado Springs, Colorado); Christopher Colwell, MD (Denver, Colorado); Dorothy Turnbull, MD (Stamford, Connecticut); Rob Rosenbaum, MD (New Castle County, Delaware); Kathleen Schrank, MD (Miami, Florida); Mark Waterman, MD (Atlanta, Georgia); Richard Dukes, MD (Clayton County, Georgia); Melissa Lewis (Dekalb County, Georgia); Raymond Fowler, MD (Douglas County, Georgia); John Lloyd, MD (Forest Park, Georgia); Art Yancey, MD (Atlanta, Georgia); Earl Grubbs, MD (Gwinnett County, Georgia); John Lloyd, MD (Hapeville, Georgia); Johnathan Morris, MD (Metro Atlanta, Georgia); Stephen Boyle, MD (Metro Atlanta, Georgia); Troy Johnson, MD (Newton County, Georgia); Christopher Wizner, MD (Puckett County, Georgia); Melissa White, MD (Metro Atlanta, Georgia); Sabina Braithwaite, MD (Sedgwick County, Kansas); Sophia Dyer, MD (Boston, Massachusetts); Gary Setnik, MD (Cambridge, Massachusetts); Bob Hassett, MD (Springfield, Massachusetts); John Santor, MD (Springfield, Massachusetts); Bob Swor, MD (Oakland County, Michigan); Todd Chassee, MD (Kent County, Michigan); Charlie Lick, MD (Hennepin County, Minnesota); Mike Parrish (Hennepin County, Minnesota); Darel Radde (Hennepin County, Minnesota); Brian Mahoney, MD (Hennepin County, Minnesota); Darell Todd (Hennepin County, Minnesota); Joseph Salomone, MD (Kansas City, Missouri); Eric Ossman, MD (Durham, North Carolina); Brent Myers, MD (Wake County, North Carolina); Lee Garvey, MD (Charlotte, North Carolina); James Camerson, MD (New Jersey); David Slattery, MD (Las Vegas, Nevada); Joseph Ryan, MD (Reno, Nevada); Jason McMullan, MD (Cincinnati, Ohio); David Keseg, MD (Columbus, Ohio); James Leaming, MD (Hershey, Pennsylvania); BK Sherwood, MD (Hilton Head, South Carolina); Jeff Luther, MD (Sioux Falls, South Dakota); Corey Slovis, MD (Nashville, Tennessee); Paul Hinchey, MD (Austin-Travis County, Texas); Michael Harrington, MD (Baytown, Texas); John Griswell, MD and Jeff Beeson, MD (Fort Worth, Texas); David Persse, MD (Houston, Texas); Mark Gamber, MD (Plano, Texas); Joe Ornato, MD (Richmond, Virginia)

Footnotes

Presented in Poster form at 2011 Society for Academic Emergency Medicine National Research Meeting, Boston, MA, June 2011

Disclosures

None to report.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Reference List

- 1.Nichol G, Thomas E, Callaway CW, Hedges J, Powell JL, Aufderheide TP, Rea T, Lowe R, Brown T, Dreyer J, Davis D, Idris A, Stiell I. Regional variation in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest incidence and outcome. JAMA. 2008 Sep 24;300(12):1423–31. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.12.1423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bernard SA. Hypothermia improves outcome from cardiac arrest. Crit Care Resusc. 2005 Dec;7(4):325–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bernard SA, Buist M. Induced hypothermia in critical care medicine: a review. Crit Care Med. 2003 Jul;31(7):2041–51. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000069731.18472.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reynolds JC, Callaway CW, El K, Sr, Moore CG, Alvarez RJ, Rittenberger JC. Coronary Angiography Predicts Improved Outcome Following Cardiac Arrest: Propensity-adjusted Analysis. J Intensive Care Med. 2009 Mar 25; doi: 10.1177/0885066609332725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lurie KG, Idris A, Holcomb JB. Level 1 cardiac arrest centers: learning from the trauma surgeons. Acad Emerg Med. 2005 Jan;12(1):79–80. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2004.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lick CJ, Aufderheide TP, Niskanen RA, Steinkamp JE, Davis SP, Nygaard SD, Bemenderfer KK, Gonzales L, Kalla JA, Wald SK, Gillquist DL, Sayre MR, Oski Holm SY, Oakes DA, Provo TA, Racht EM, Olsen JD, Yannopoulos D, Lurie KG. Take Heart America: A comprehensive, community-wide, systems-based approach to the treatment of cardiac arrest. Crit Care Med. 2011 Jan;39(1):26–33. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181fa7ce4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nichol G, Aufderheide TP, Eigel B, Neumar RW, Lurie KG, Bufalino VJ, Callaway CW, Menon V, Bass RR, Abella BS, Sayre M, Dougherty CM, Racht EM, Kleinman ME, O’Connor RE, Reilly JP, Ossmann EW, Peterson E. Regional systems of care for out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: A policy statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2010 Feb 9;121(5):709–29. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3181cdb7db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Birkmeyer JD, Siewers AE, Finlayson EV, Stukel TA, Lucas FL, Batista I, Welch HG, Wennberg DE. Hospital volume and surgical mortality in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2002 Apr 11;346(15):1128–37. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa012337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hannan EL, Wu C, Ryan TJ, Bennett E, Culliford AT, Gold JP, Hartman A, Isom OW, Jones RH, McNeil B, Rose EA, Subramanian VA. Do hospitals and surgeons with higher coronary artery bypass graft surgery volumes still have lower risk-adjusted mortality rates? Circulation. 2003 Aug 19;108(7):795–801. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000084551.52010.3B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Halm EA, Lee C, Chassin MR. Is volume related to outcome in health care? A systematic review and methodologic critique of the literature. Ann Intern Med. 2002 Sep 17;137(6):511–20. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-137-6-200209170-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nathens AB, Jurkovich GJ, Maier RV, Grossman DC, MacKenzie EJ, Moore M, Rivara FP. Relationship between trauma center volume and outcomes. JAMA. 2001 Mar 7;285(9):1164–71. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.9.1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thiemann DR, Coresh J, Oetgen WJ, Powe NR. The association between hospital volume and survival after acute myocardial infarction in elderly patients. N Engl J Med. 1999 May 27;340(21):1640–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199905273402106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hannan EL, Racz M, Ryan TJ, McCallister BD, Johnson LW, Arani DT, Guerci AD, Sosa J, Topol EJ. Coronary angioplasty volume-outcome relationships for hospitals and cardiologists. JAMA. 1997 Mar 19;277(11):892–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Callaway CW, Schmicker R, Kampmeyer M, Powell J, Rea TD, Daya MR, Aufderheide TP, Davis DP, Rittenberger JC, Idris AH, Nichol G. Receiving hospital characteristics associated with survival after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Resuscitation. 2010 May;81(5):524–9. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2009.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carr BG, Kahn JM, Merchant RM, Kramer AA, Neumar RW. Inter-hospital variability in post-cardiac arrest mortality. Resuscitation. 2009 Jan;80(1):30–4. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2008.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stub D, Smith K, Bray JE, Bernard S, Duffy SJ, Kaye DM. Hospital characteristics are associated with patient outcomes following out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Heart. 2011 Jun 21; doi: 10.1136/hrt.2011.226431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McNally B, Stokes A, Crouch A, Kellermann AL. CARES: Cardiac Arrest Registry to Enhance Survival. Ann Emerg Med. 2009 Nov;54(5):674–83. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2009.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sasson C, Hegg AJ, Macy M, Park A, Kellermann A, McNally B. Prehospital termination of resuscitation in cases of refractory out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. JAMA. 2008 Sep 24;300(12):1432–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.12.1432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cummins RO, Chamberlain DA, Abramson NS, Allen M, Baskett PJ, Becker L, Bossaert L, Delooz HH, Dick WF, Eisenberg MS. Recommended guidelines for uniform reporting of data from out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: the Utstein Style. A statement for health professionals from a task force of the American Heart Association, the European Resuscitation Council, the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada, and the Australian Resuscitation Council. Circulation. 1991 Aug;84(2):960–75. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.84.2.960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.American Hospital Association. AHA Annual Survey Database for Fiscal Year 2005. Chicago, IL: American Hospital Association; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dai JJ, Li Z, Rocke DM. Hierarchical Logistic Regression Modeling with SAS GLIMMIX. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guo S. Analyzing grouped data with hierarchical linear modeling. Children and Youth Services Review. 2005;27:637–52. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Royston P. A strategy for modelling the effect of a continuous covariate in medicine and epidemiology. Stat Med. 2000 Jul 30;19(14):1831–47. doi: 10.1002/1097-0258(20000730)19:14<1831::aid-sim502>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Royston P, Sauerbrei W. A new approach to modelling interactions between treatment and continuous covariates in clinical trials by using fractional polynomials. Stat Med. 2004 Aug 30;23(16):2509–25. doi: 10.1002/sim.1815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Carr BG, Goyal M, Band RA, Gaieski DF, Abella BS, Merchant RM, Branas CC, Becker LB, Neumar RW. A national analysis of the relationship between hospital factors and post-cardiac arrest mortality. Intensive Care Med. 2009 Mar;35(3):505–11. doi: 10.1007/s00134-008-1335-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Auerbach AD, Hilton JF, Maselli J, Pekow PS, Rothberg MB, Lindenauer PK. Shop for quality or volume? Volume, quality, and outcomes of coronary artery bypass surgery. Ann Intern Med. 2009 May 19;150(10):696–704. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-10-200905190-00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kurlansky PA, Argenziano M, Dunton R, Lancey R, Nast E, Stewart A, Williams T, Zapolanski A, Chang H, Tingley J, Smith AL. Quality, not volume, determines outcome of coronary artery bypass surgery in a university-based community hospital network. Journal of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery. 2012 Feb 1;143(2):287–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2011.10.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Birkmeyer JD, Stukel TA, Siewers AE, Goodney PP, Wennberg DE, Lucas FL. Surgeon volume and operative mortality in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2003 Nov 27;349(22):2117–27. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa035205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Srinivas VS, Hailpern SM, Koss E, Monrad ES, Alderman MH. Effect of physician volume on the relationship between hospital volume and mortality during primary angioplasty. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009 Feb 17;53(7):574–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.09.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Drummond AE, Pearson B, Lincoln NB, Berman P. Ten year follow-up of a randomised controlled trial of care in a stroke rehabilitation unit. BMJ. 2005 Sep 3;331(7515):491–2. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38537.679479.E0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kalra L, Eade J. Role of stroke rehabilitation units in managing severe disability after stroke. Stroke. 1995 Nov;26(11):2031–4. doi: 10.1161/01.str.26.11.2031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Indredavik B, Bakke F, Slordahl SA, Rokseth R, Haheim LL. Stroke unit treatment. 10-year follow-up. Stroke. 1999 Aug;30(8):1524–7. doi: 10.1161/01.str.30.8.1524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Peberdy MA, Callaway CW, Neumar RW, Geocadin RG, Zimmerman JL, Donnino M, Gabrielli A, Silvers SM, Zaritsky AL, Merchant R, Vanden Hoek TL, Kronick SL. Part 9: post-cardiac arrest care: 2010 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care. Circulation. 2010 Nov 2;122(18 Suppl 3):S768–S786. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.971002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Spaite DW, Stiell IG, Bobrow BJ, de BM, Maloney J, Denninghoff K, Vadeboncoeur TF, Dreyer J, Wells GA. Effect of Transport Interval on Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest Survival in the OPALS Study: Implications for Triaging Patients to Specialized Cardiac Arrest Centers. Ann Emerg Med. 2009 Jan 22; doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2008.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Davis DP, Fisher R, Aguilar S, Metz M, Ochs G, Callum-Brown L, Ramanujam P, Buono C, Vilke GM, Chan TC, Dunford JV. The feasibility of a regional cardiac arrest receiving system. Resuscitation. 2007 Jul;74(1):44–51. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2006.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cudnik MT, Schmicker RH, Vaillancourt C, Newgard CD, Christenson JM, Davis DP, Lowe RA. A geospatial assessment of transport distance and survival to discharge in out of hospital cardiac arrest patients: Implications for resuscitation centers. Resuscitation. 2010 May;81(5):518–23. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2009.12.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.MacKenzie EJ, Rivara FP, Jurkovich GJ, Nathens AB, Frey KP, Egleston BL, Salkever DS, Scharfstein DO. A national evaluation of the effect of trauma-center care on mortality. N Engl J Med. 2006 Jan 26;354(4):366–78. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa052049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Demetriades D, Martin M, Salim A, Rhee P, Brown C, Doucet J, Chan L. Relationship between American College of Surgeons trauma center designation and mortality in patients with severe trauma (injury severity score > 15) J Am Coll Surg. 2006 Feb;202(2):212–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2005.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cudnik MT, Newgard CD, Sayre MR, Steinberg SM. Level I versus Level II trauma centers: an outcomes-based assessment. J Trauma. 2009 May;66(5):1321–6. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181929e2b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Curry LA, Spatz E, Cherlin E, Thompson JW, Berg D, Ting HH, Decker C, Krumholz HM, Bradley EH. What distinguishes top-performing hospitals in acute myocardial infarction mortality rates? A qualitative study. Ann Intern Med. 2011 Mar 15;154(6):384–90. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-154-6-201103150-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bobrow BJ, Spaite DW, Berg RA, Stolz U, Sanders AB, Kern KB, Vadeboncoeur TF, Clark LL, Gallagher JV, Stapczynski JS, LoVecchio F, Mullins TJ, Humble WO, Ewy GA. Chest compression-only CPR by lay rescuers and survival from out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. JAMA. 2010 Oct 6;304(13):1447–54. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Celso B, Tepas J, Langland-Orban B, Pracht E, Papa L, Lottenberg L, Flint L. A systematic review and meta-analysis comparing outcome of severely injured patients treated in trauma centers following the establishment of trauma systems. J Trauma. 2006 Feb;60(2):371–8. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000197916.99629.eb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Foley N, Salter K, Teasell R. Specialized stroke services: a meta-analysis comparing three models of care. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2007;23(2–3):194–202. doi: 10.1159/000097641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rittenberger JC, Raina K, Holm MB, Kim YJ, Callaway CW. Association between Cerebral Performance Category, Modified Rankin Scale, and discharge disposition after cardiac arrest. Resuscitation. 2011 Aug;82(8):1036–40. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2011.03.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stub D, Hengel C, Chan W, Jackson D, Sanders K, Dart AM, Hilton A, Pellegrino V, Shaw JA, Duffy SJ, Bernard S, Kaye DM. Usefulness of cooling and coronary catheterization to improve survival in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Am J Cardiol. 2011 Feb 15;107(4):522–7. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2010.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]