Abstract

Infants of mothers who varied in symptoms of depression were tested at 4 and 12 months of age for their ability to associate a segment of an unfamiliar non-depressed mother’s infant-directed speech (IDS) with a face. At 4 months, all infants learned the voice-face association. At 12 months, despite the fact that none of the mothers were still clinically depressed, infants of mothers with chronically elevated self-reported depressive symptoms, and infants of mothers with elevated self-reported depressive symptoms at 4 months but not 12 months, on average did not learn the association. For infants of mothers diagnosed with depression in remission, learning at 12 months was negatively correlated with the postpartum duration of the mother’s depressive episode. At neither age did extent of pitch modulation in the IDS segments correlate with infant learning. However, learning scores at 12 months correlated significantly with concurrent maternal reports of infant receptive language development. The roles of the duration and timing of maternal depressive symptoms are discussed.

Children of depressed mothers have a higher than normal risk for problems in cognitive development, including delays in reaching cognitive-developmental milestones (Murray, 1992), lags in attaining school-readiness (NICHD, 1999), and lower later IQ (Hay, 1997). The roots of these problems may be found in the quality and quantity of caregiver-infant interactions in infancy (Cicchetti, Rogosch, & Toth, 2000; Stanley, Murray, & Stein, 2004; Hay, 1997; Milgrom, Westley, & Gemmill, 2004). Research in our laboratory has involved a systematic analysis of the learning-promoting effects of an important kind stimulation for infants. Infant-directed speech (IDS), a distinctive style of speech characterized by exaggeration in prosodic cues, simplification of speech, and frequent repetition, is particularly effective at attracting and maintaining infant attention, modulating infant affect and arousal, and facilitating infant learning and rudimentary speech perception (Fernald, 1984; Kuhl, 2007). However, depressed mothers and fathers are known to produce IDS that is lacking in the extent of prosodic exaggeration (Bettes, 1988; Kaplan, Bachorowski, Smoski, & Zinser, 2001; Kaplan, Sliter, & Burgess, 2007; Zlochower & Cohn, 1996), an acoustic cue that has been linked to infant responding (Fernald & Kuhl, 1987). A series of experiments using a conditioned-attention paradigm (see below) has shown that, although IDS normally serves as a “priming” stimulus to facilitate infant voice-face associative learning (Kaplan, Jung, Ryther, & Kirk, 1996), IDS produced by depressed mothers is relatively ineffective in this regard (Kaplan, Bachorowski, & Zarlengo-Strouse, 1999). Moreover, whereas 4-month-old infants of depressed mothers learn well in response to IDS produced by unfamiliar non-depressed mothers, older infants of more chronically depressed mothers do not (Kaplan, Dungan, & Zinser, 2004; Kaplan, Danko, Diaz, & Kalinka, 2011), suggesting an experience-based change in infant responsiveness to maternal IDS. Because caregivers frequently use IDS and other stimuli to prime infant learning about the world around them (Fernald, 1984), an analysis of a progressive decline in responding to IDS across the first year in infants of depressed mothers may provide clues about the development of cognitive delays in these infants. The purpose of the current study was to track the development of this partially generalized associative learning deficit by assessing learning in individual infants at both 4 and 12 months.

The experiments reported here employed a conditioned-attention paradigm as a model system with which to study infant associative learning. As with overt responses, attentional responses are maintained or increase when one stimulus, S1, reliably predicts another, S2 (Lubow, 1989; Lubow & Josman, 1996). Kaplan, Fox, and Huckeby (1992) showed that a tone that had reliably preceded a smiling face acquired the ability to subsequently increase 4-month-olds’ looking at a novel checkerboard pattern, whereas a tone that reliably followed the face, or was presented randomly with respect to the face, did not. Properties of the signaling stimulus, such as its ability to increase an infant’s state of arousal, can have a proactive effect on the formation of the S1–S2 association. For example, a segment of IDS that reliably preceded a smiling face subsequently increased 4-month-olds’ looking at a novel checkerboard pattern, whereas IDS that reliably followed the face, and adult-directed speech (ADS) that reliably preceded or followed the face, were significantly less effective (Kaplan et al., 1996).

In contrast, the learning-promoting effects of maternal IDS for 4-month-olds were lacking in IDS produced by depressed mothers. In one study, 4-month-old infants of non-depressed mothers did not show evidence of learning in response to IDS recorded from mothers with elevated scores on the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI; Beck, Ward, Mendelson, Mach, & Erbaugh, 1961), but did exhibit learning in response to IDS recorded from mothers with non-elevated BDI scores. The same pattern of infant responding held for IDS recorded from clinically depressed in comparison with non-depressed mothers (Kaplan et al., 1999). In another study, 4-month-old infants of depressed mothers did not learn in response to their own or an unfamiliar depressed mother’s IDS, but showed significant learning in response to an unfamiliar non-depressed mother’s IDS (Kaplan, Bachorowski, Smoski, & Hudenko, 2002).

However, more prolonged exposure to a depressed primary caregiver produced a broader learning deficit in this paradigm. Kaplan et al. (2004) found that 5- to 13-month-old infants of depressed mothers not only failed to acquire voice-face associations in response to their own mothers’ IDS but, in contrast to the 4-month-olds, on average also failed to acquire associations in response to IDS produced by unfamiliar non-depressed mothers (Kaplan et al., 2004; Exp. 1). There was a significant negative correlation between infant learning and the post-partum duration of the infant’s mother’s current depressive episode. Interestingly, the same infants who on average did not exhibit learning in response to an unfamiliar non-depressed mother’s IDS exhibited better-than-normal learning in response to an unfamiliar non-depressed father’s IDS (Kaplan et al., 2004; Exp. 2). A follow-up study with 12-month-olds replicated this effect, but only for infants of depressed married mothers, suggesting a potential role for father involvement (Kaplan, Danko, & Diaz, 2010). These findings imply that, at least by the second half of the first year, responding to IDS is conditional upon social experience.

The hypothesis that learning failures in response to non-depressed mothers’ IDS among infants of chronically depressed mothers were due to greater duration of maternal depression, rather than to differences in infant age or severity of depression, was supported a study on 12-month-old infants of currently depressed mothers. Infants of depressed mothers with perinatal depression onset (i.e., onset within 1 month before or after birth) did not acquire associations in response to an unfamiliar non-depressed mother’s IDS, whereas infants of depressed mothers with later depression onset (mean duration of about 4 months) acquired the association, even though there were no current differences between groups in maternal depression severity, global assessment of functioning (GAF), or anti-depressant medication use (Kaplan et al., 2011).

The results of this series of studies suggest that infants of chronically depressed mothers undergo a transition during the first year of life during which their responsiveness to female IDS declines. This decline is not attributable to low perceptual salience of the IDS, or an infant’s prior learning that affectively flat IDS does not “go with” a smiling face, because it occurs in response to normal IDS produced by non-depressed mothers. Consistent with conditioned-attention theory, Kaplan et al. (2004) posited that infants of mothers who are low in sensitivity and contingent responding might learn to “tune-out” maternal IDS, in much the same way that organisms who are pre-exposed to an isolated stimulus exhibit comparatively slower associative learning when that stimulus subsequent signals an important outcome (“latent inhibition,” Lubow, 1989, or “learned irrelevance,” Linden, Savage, & Overmeier, 1997). If infants’ tendency to “tune-out” their mothers generalized to other female, but not male, IDS stimuli, then the pattern of results described above could be explained. In support of an experience-based account, Kaplan, Burgess, Sliter, and Moreno (2009) found that blind ratings of a mother’s sensitivity using the Emotional Availability Scales (Biringen & Robinson, 1991), coded from a separate mother-infant play interaction, significantly predicted infant learning in response to their own mothers’ IDS even after demographic risk factors, extent of F0 modulation, antidepressant medication use, and maternal depression had been taken into account.

The current experiment had three main goals. The first was to confirm the apparent developmental transition in responding to female IDS among infants of chronically depressed mothers, by assessing voice-face associative learning in response to “non-depressed” IDS in individual infants of continuously non-depressed versus continuously depressed mothers at 4 months and 12 months of age. We predicted that infants of non-depressed mothers would exhibit learning at both ages, whereas age-matched infants of chronically depressed mothers would exhibit learning at 4 months but not at 12 months. The second goal was to examine whether some of the effects attributable to depression duration might be at least partially attributable to early depression, by examining learning in 12-month-olds whose mothers had elevated symptoms of depression at 4 months but not at 12 months. Previous research has shown that 4-month-old infants of mothers with depression durations of up to 4 months exhibit significant learning in response to “non-depressed” female IDS, as do 12-month-old infants of depressed mothers with late onset depression (mean duration of approximately 4 months). However, effects of early depression on later learning have not been studied. The third goal was to provide a preliminary assessment of whether this kind of associative learning deficit can be linked to a more general deficit in cognitive development, by examining correlations between infants’ responding to IDS in this paradigm and maternal reports of vocabulary development using the MacArthur Communicative Development Inventory (MCDI; Fenson, Dale, Reznick, Bates, Thal, & Rethick, 1994). We predicted that, because IDS not only promotes voice-face associative learning (Kaplan et al., 1996), but also facilitates rudimentary processes such as phoneme discrimination (Kuhl, 2007; Liu, Kuhl, & Tsao, 2003), segmentation of the speech stream (Thiessen, Hill, & Saffran, 2005), and word learning and memory (Ma, Golinkoff, Houston, & Hirsh-Pasek, in press; Singh, Nestor, Parikh, & Yull, 2009), infants who were more responsive to IDS in our paradigm would also have larger receptive and productive vocabularies.

Method

Participants

Ninety-seven infants and their mothers participated in the study. Most mothers and infants (n = 90) were recruited through a monthly advertisement in Colorado Parent, a local parenting magazine available for free at area markets and infant-oriented retail stores. The remaining mothers and infants (n = 7) were recruited through Early Head Start (EHS) centers in the Denver Metropolitan area. To be included in the study, infants had to be healthy and full-term. The mean age of the mothers was 29.9 years (SD = 5.1 years). The mean age of the infants at the 4-month test was 135 days (SD = 22.5 days), and the mean age at the 12-month test was 357 days (SD = 32.2 days). Fifty-four of the mothers were White (55.6%), 25 were Latina (25.8%), 10 were African-American (10.3%), 5 were Asian (5.2%), and 3 were Native-American (3.1%). These proportions are consistent with those obtained in the City and County of Denver in the most recent U.S. Census. Their modal education level was 6.0 (where 5.0 = graduated college with a 2 year degree and 6.0 = graduated with a 4-year degree), and their modal family income was 7.0 (where 6.0 = $31,000–$40,000 and 7.0 = $41,000–$50,000). Mothers reported having a mean of 2.0 children (SD = 1.1). Seventy-three of the mothers (75.3%) reported they were legally married and 24 reported they were unmarried. Of the latter, 19 reported that they were currently cohabitating with a partner.

Apparatus

Four-month-old infants were tested in a car seat that was attached to a barber’s chair and situated in front of a large board that had been painted flat-black. During the 12-month test infants sat in their mothers’ laps, and the mother sat in the barber chair without the infant car seat. This mode of testing proved effective in prior studies with this age group (Kaplan et al., 2011). Mothers wore headphones with masking music, and a visor that blocked their view of the projection screen but permitted them to view their infants. In both arrangements, the height of the chair was adjusted such that the infant’s eyes were level with a 4-in square translucent Plexiglas projection screen that was embedded in the board. Located 1.9 cm to the infant’s left of the projection screen was an aperture through which a low-light video camera recorded the infant’s face. Two full-face views of the infant were displayed on 48.3-cm video monitors in separate rooms for two independent observers. Auditory stimuli were presented to infants using a SONY TCM 5000EV tape player. To ensure that looking at the projection screen was not an artifact of infants’ visual orienting toward the sound source, the loudspeaker was situated 10 cm below and 33.5 cm behind the infant’s head. The average distance from the infant’s head to the projection screen was approximately 42 cm. Two black-and-white visual stimuli, a slide of a smiling female face and a 4×4 checkerboard pattern (checks subtended 3° of visual angle), were presented using two computer-controlled slide projectors outfitted with shutters.

Speech Stimuli

Ninety-seven IDS samples were randomly selected at each age (without replacement) from a large pool of IDS segments previously recorded from non-depressed mothers (BDI-II score under 14 and without a DSM-IV diagnosis) in a 3-minute play interaction. Each infant was tested with an IDS stimulus from an unfamiliar mother. No attempt was made to test an individual infant with the same unfamiliar mother’s voice at 4 and 12 months.

IDS segments had been obtained from recording sessions during which mothers were asked to talk to their infants as they would at home. Following 2 minutes, mothers were handed a stuffed toy gorilla and asked to interest their infant in it using the phrase “pet the gorilla.” Mothers were instructed to both “ask” and “tell” their infants to “pet the gorilla” to make sure that both declarative and interrogative utterances would be made. This phase of the recording lasted about 1 min. To assemble a set of 10-s IDS segments roughly matched for linguistic content, the first two interrogative and the first declarative “pet the gorilla” utterances were edited out of the speech stream and repeated once (e.g., Will you pet the gorilla? Can you pet the gorilla? Pet the gorilla. Will you pet the gorilla? Can you pet the gorilla? Pet the gorilla.”). During this phase, the individual responsible for recording and editing the tapes was unaware of maternal depression diagnosis and self-reports. All speech samples were submitted to analyses of mean fundamental frequency range (ΔF0) using Praat Acoustic Analysis Software (Boersma & Weenink, 2009), and correlations between mean ΔF0 and infant learning were examined.

Assessment of Depressive Symptoms

All mothers were asked to fill out the BDI-II, a 21-item self-report instrument that is widely used for assessing the affective, cognitive, motivational, and physiological symptoms associated with depression (Beck, Steer, & Brown, 1996). The BDI-II has significant correlations with psychiatric ratings in clinical samples (Steer, Ball, Ranieri, & Beck, 1997). Suggested cut-offs for classifying respondents as “non-depressed” (BDI-II scores ≤ 13) or “depressed” (BDI-II scores > 13) were used in data analyses, in addition to clinical diagnoses. Here, we refer to the two BDI-II categories as “non-elevated” and “elevated,” respectively.

In addition, all mothers were administered the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis-I diagnosis (SCID; First et al., 1997). Clinical diagnoses were arrived at by Ph.D.-supervised, M.A.-level clinical psychologists, or clinical psychology graduate students, all with extensive training on the SCID and DSM-IV diagnosis. Training involved coursework, video demonstrations, observation of the trainer by the student, and practice interviews. Interviews lasted about 1 hr. Inter-rater reliability for diagnoses of Major Depression, calculated between the primary rater and a Ph.D.-level second rater yielded a kappa value of .86. Final diagnoses were based on the primary rater. We reserve the term “depressed” (DEP) for individuals diagnosed with a DSM-IV Axis-I depression-spectrum disorder, including Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) and Depressive Disorder Not Otherwise Specified (DDNOS).

Assessment of Vocabulary Development

Maternal reports of infant vocabulary development were obtained during the 12-month visit using the MCDI Infant Scale, short form; Fenson et al, 1994; Fenson, Pethick, Renda, Cox, Dale, & Reznick, 2000). The MCDI is a norm-referenced parent-report assessment of a child’s lexical growth (comprehension and production) using a standardized questionnaire. The parent is presented a list of 89 words and asked to identify words comprehended and spontaneously produced by the child in two separate columns.

Procedure

All procedures and materials were reviewed and approved by our institutional review board. We strictly adhered to APA ethical principles in the conduct of the study. At each age the testing procedure was identical, except that 4-month-olds sat in a car seat and 12-month-olds sat in their mothers’ laps. Immediately after filling out informed consent forms and all questionnaires (although the MCDI was administered only at 12 months), the infant conditioned-attention test was given. At the end of the conditioned-attention test, mothers were administered the SCID. The entire visit to the laboratory last approximately two hours.

On conditioning trials, each infant first heard a 10-s “pet the gorilla” speech segment when the projection screen was uniformly illuminated. At the offset of the speech segment, the infant received a 10-s presentation of a black-and-white photographic slide of a smiling adult female face. A 10-s inter-stimulus interval (ISI), during which the projection screen was uniformly illuminated and only background noise was heard, immediately followed the offset of the face. Infants received six speech segment-face pairings. Ten s after the offset of the sixth face, the post-conditioning test phase began. Infants received 4 10-s presentations of a 4 × 4 black-and-white checkerboard pattern (10-s ISIs). The speech segment from the pairing phase was presented simultaneously with the first and fourth checkerboards, whereas the second and third checkerboards occurred with only background noise (measured near the infant’s head at 58 dB). The total duration of the conditioned-attention test was 260 s. Durations of infant looking at the projection screen during each 10-s speech segment, face, and checkerboard trials were recorded. Two observers, each blind to diagnostic status, independently signaled looking when the reflection of the visual stimulus was centered on the infant’s pupils. The mean inter-observer correlation was .91 (SD = .05).

Data Analysis

Demographic variables were compared for clinically depressed and non-depressed mothers (and those with elevated vs. non-elevated BDI-II scores) to determine if they would then need to be controlled in analyses of infant learning. Split-plot repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to analyze the trial-by-trial test phase data, and one-way ANOVAs were used to analyze the resulting summary difference score data (see below) at each age. The data from the 4-month test were analyzed first, to determine if the pattern of findings previously obtained with 4-month-olds (Kaplan et al., 1999; Kaplan et al., 2002) had replicated. Similar analyses were carried out for the 12-month data. To test the two main hypothesis, that learning at the 12-month test would differ based on the presence and duration of symptoms of depression, a split-plot repeated measures ANOVA was performed on summation test data as a function of 4 groups (continuously non-elevated symptoms of depression, continuously elevated symptoms of depression, elevated symptoms at 4 months but not at 12 months, and elevated symptoms at 12 months but not 4 months) and the two test ages (4 and 12 months). To adjust for the possibility of an asymmetrical covariance matrix, Greenhouse-Geisser corrected degrees of freedom were used in all repeated-measures ANOVAs.

Results

Demographic and diagnostic data

Table 1 presents demographic and diagnostic information for the full sample of mothers and infants (N = 97). There were no differences as a function of 4-month BDI-II category or depression diagnosis in maternal age, infant age, infant gender, maternal education, family income, ethnicity, or marital status. Number of children was higher for mothers with elevated in comparison to non-elevated BDI-II scores, but did not differ between clinically depressed and non-depressed mothers.

Table 1.

Maternal Demographic and Diagnostic Data

| Variable | Non-Elevated (BDI-II) |

Elevated (BDI-II) |

NDEP (DSM-IV) |

DEP (DSM-IV) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | ||||

| 4 months (n = 97) | 56 | 41 | 85 | 12 |

| 12 months (n = 75) | 58 | 17 | 73 | 2 |

| Gender (girls/boys) | ||||

| 4 months | 28/28 | 17/24 | 39/46 | 6/6 |

| 12 months | 26/32 | 8/9 | 34/39 | 1/1 |

| Age of mother (years) | 30.2 (4.7) | 29.5 (5.7) | 30.0 (5.3) | 29.4 (5.1) |

| Age of infant (days) | ||||

| 4 months | 131 (21.7) | 139 (23.2) | 133 (22.5) | 143.0 (21.9) |

| 12 months | 360 (34.7) | 353 (28.1) | 352 (33.7) | 360 (18.6) |

| Ethnicity (4 mos.) | ||||

| White | 33 (58.9%) | 21 (51.2%) | 48 (56.5%) | 6 (50.0%) |

| Latina | 14 (25.0%) | 11 (26.8%) | 22 (25.9%) | 3 (25.0%) |

| African-American | 5 (8.9%) | 5 (12.2%) | 7 (8.2%) | 3 (25.0%) |

| Asian | 3 (5.4%) | 2 (4.9%) | 5 (5.9%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Native American | 1 (1.8%) | 2 (4.9%) | 3 (3.5%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Marital status | ||||

| married | 45 (80.4%) | 28 (68.3%) | 64 (75.3%) | 9 (75.0%) |

| unmarried | 11 (19.6%) | 13 (31.7%) | 21 (24.7%) | 3 (25.0%) |

| Mother’s education | 5.8 (1.5) | 5.2 (1.2) | 5.5 (1.4) | 5.3 (1.2) |

| Family income | 6.1 (2.3) | 5.9 (2.4) | 5.8 (1.5) | 6.5 (1.6) |

| Number of children | 1.8 (1.0)a | 2.3 (1.1)b | 2.0 (1.1) | 2.1 (1.0) |

| BDI-II score 4 mo | 7.7 (3.2)a | 22.1 (7.0)b | 12.1 (7.5)a | 26.2 (7.8)b |

| BDI-II score 12 mo | 6.2 (6.0)a | 12.5 (7.4)b | 8.3 (7.3)a | 12.0 (5.9)a |

| GAF rating 4 mo | 79.5 (6.5)a | 69.9 (9.9)b | 77.3 (7.7)a | 62.1 (9.4)b |

| GAF rating 12 mo | 79.1 (6.1)a | 71.3 (7.6)b | 76.7 (7.0)a | 69.0 (9.2)b |

Columns are defined based on 4-month BDI-II scores and SCID interviews. Numbers in parentheses are standard deviations. GAF = global assessment of functioning, as estimated from SCID interviews. Information about demographics in the subsets of infants who completed the 4-month and 12-month learning tests is presented in the text. Means with different subscripts differed significantly (p = .05).

Participant attrition

At the 4-month visit, 10 out of 97 infants (10.3%) failed to provide infant learning data due to excessive fussing (1 infant of a DEP mother and 9 infants of NDEP mothers). Attempts were made to retest all 97 participants at 12 months. Twenty-two out of 97 initial participants (22.7%) either declined our invitation to return for the 12-month follow-up (n = 11), or could not be reached due to disconnected telephone lines or having moved out of the area (n = 10). Two of these 22 were EHS mothers, including one who was clinically depressed at 4 months. Families that dropped out of the study did not differ from those that continued with the study in maternal age, infant age, family income, ethnicity, marital status, number of children, or BDI-II score at 4 months (MBDI = 14.3 vs. 13.8, respectively). They did have significantly lower educational attainment than those who completed the study, Mann-Whitney U = 560, z = 2.39, p = .02.

Thus, a total of 75 out of 97 infants and their mothers visited our laboratory at both 4 and 12 months (77.3% of the initial sample). Of these, 68 completed the 12-month learning test (including 5 who had not completed the 4-month test), and 63 successfully completed infant learning tests at both ages (64.9% of the original sample, or 84.0% of the infants who attended both sessions; 5 completed only the 4-month test, and 2 completed neither).

In addition, of the 12 mothers who were diagnosed as clinically depressed at 4 months (11 MDD and 1 DDNOS), none was still clinically depressed at 12 months. Five were diagnosed with depression in partial remission (PR, defined as the presence of some symptoms of depression but not enough to meet full criteria, or a period without significant symptoms that has lasted less than 2 months, with no previous dysthymic disorder; APA, 1994), indicating that they had not completely recovered. Four were diagnosed with depression in full remission (FR, defined as the absence of significant signs or symptoms in the past 2 months), and 3 did not return at 12 months (25% drop-out rate for DEP mothers). Only 2 mothers were diagnosed with MDD at 12 months, and neither had been clinically depressed at 4 months. Therefore, in most of the present data analyses, infants and their mothers who attended laboratory sessions at both ages were compared as a function of non-elevated vs. elevated maternal BDI-II categories at the 2 ages (N = 75; this classification yielded 4 categories: non-elevated 4—12, n = 41; non-elevated 4—elevated 12, n = 4; elevated 4—non-elevated 12, n = 17; elevated 4 —12, n = 13), as well as based on the duration of the mother’s depressive episode. Demographic data were reanalyzed using these 4 BDI-II categories. There were no significant differences in maternal or infant age, maternal education, family income, minority status, marital status, or number of children.

Infant Learning

Tests Pairing phases

A series of previous studies showed that looking during IDS stimulus presentations (projection screen uniformly illuminated) and faces across the 6 voice-face pairing trials did not change across trials, and did not differ based on maternal depressive symptoms or clinical diagnoses (Kaplan et al., 2002; Kaplan et al., 2004, Kaplan et al., 2011). The same was true at both test ages in the current study, consistent with the idea that differences obtained in the crucial summation test phase are not attributable to baseline differences in responding between infants of depressed and non-depressed mothers. Therefore, these data are not discussed further.

Summation test phase: 4-month test

Out of the 97 infants tested, 87 completed the 4-month learning test. A 2 (mother DEP vs. NDEP) × 4 (test trials) ANOVA with Greenhouse- Geisser corrected df yielded no significant effect of groups, F(1, 82) = 0.61, but a significant effect of trials, F(3, 235) = 14.34, p = .001, η2 = .149, and no significant groups × trials interaction, F(3, 235) = 1.73, p = .16. Table 2 presents mean looking times across the four checkerboard presentations grouped according to the joint 4- and 12-month maternal BDI-II categories. A 4 (joint 4-/12-month BDI-II categories) × 4 (test trials) ANOVA carried out on these data yielded no significant effect of groups, F(3, 64) = 0.44, but a significant effect of trials, F(3, 167) = 9.39, p = .001, η2 = .130, and no significant groups × trials interaction, F(9, 167) = 1.21, p = .30.

Table 2.

Mean Looking Times in Seconds on 4-Month Summation Test Trials as a Function of BDI-II Category

| Test Trial | NE 4—12 | NE 4—E 12 | E 4—NE 12 | E 4—12 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Voice + Checkerboard | 7.41 (2.62) | 7.95 (1.81) | 8.91 (1.31) | 7.35 (2.51) |

| 2 | Checkerboard | 5.70 (3.06) | 8.30 (2.69) | 6.71 (3.21) | 6.55 (1.94) |

| 3 | Checkerboard | 5.31 (3.32) | 4.62 (4.04) | 6.42 (3.59) | 5.44 (3.32) |

| 4 | Voice + Checkerboard | 6.87 (3.07) | 5.58 (2.87) | 7.93 (2.74) | 7.91 (1.81) |

| DS | 1.64 (2.01) | 0.31 (1.86) | 1.86 (1.96) | 1.64 (1.91) |

Note: DS = difference score, in seconds. NE 4—12 = non-elevated 4—12; E 4—NE 12 = elevated 4—non-elevated 12; NE 4—E 12 = non-elevated 4—elevated 12; E 4—12 = elevated 4—12.

A difference score was calculated by subtracting the mean duration of looking on checkerboard-alone test trials from that on voice-plus-checkerboard test trials. Positive scores indicate that voice stimuli increased looking at checkerboards, and prior research has shown significant increases (“positive summation”) after forward-pairing but not control arrangements (Kaplan et al., 1992; Kaplan et al., 1996; Kaplan et al., 2004). Therefore, difference scores significantly above zero are taken as evidence for associative learning. Mean difference scores did not vary at 4 months as a function of the mothers’ depression diagnosis (NDEP: M = 1.45 s, SD = 1.92; DEP: M = 2.50 s, SD = 2.30; F(1, 85) = 2.73, p = .11) or joint 4-/12-month BDI-II category (see Table 2). Four-month difference scores were not significantly correlated with the mean ΔF0’s in the IDS segments with which the infants were tested, r = .08, p = .57.1

Summation test phase: 12-month test

Of the 75 infants tested at 12 months, 68 completed the learning test. Table 3 shows looking times on the 4 test trials. A 4 (joint 4-/12-month BDI-II category) × 4 (test trials) ANOVA with Greenhouse-Geisser corrected df showed a non-significant effect of groups, F(3, 64) = 0.79, a significant effect of trials, F(3, 177) = 4.26, p = .01, η2 = .067, and a significant groups × trials interaction, F(9, 177) = 2.78, p = .01, η2 = .124.

Table 3.

Mean Looking Times in Seconds on 12-Month Summation Test Trials as a Function of BDI-II ategory

| Test Trial | NE 4—12 | NE 4—E 12 | E 4—NE 12 | E 4—12 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Voice + Checkerboard | 7.14 (2.83) | 7.62 (1.86) | 6.71 (2.65) | 5.52 (3.60) |

| 2 | Checkerboard | 5.11 (2.93) | 6.27 (2.76) | 5.77 (2.29) | 5.60 (2.98) |

| 3 | Checkerboard | 4.14 (2.89) | 3.42 (2.23) | 6.46 (3.02) | 6.06 (3.14) |

| 4 | Voice + Checkerboard | 5.54 (3.66) | 3.83 (4.31) | 5.62 (3.65) | 5.43 (3.52) |

| DS | 1.72 (2.36) | 0.88 (2.16) | 0.05 (1.79) | −0.36 (2.92) |

Note: DS = difference score, in seconds. NE 4—12 = non-elevated 4—12; E 4—NE 12 = elevated 4—non-elevated 12; NE 4—E 12 = non-elevated 4—elevated 12; E 4—12 = elevated 4—12.

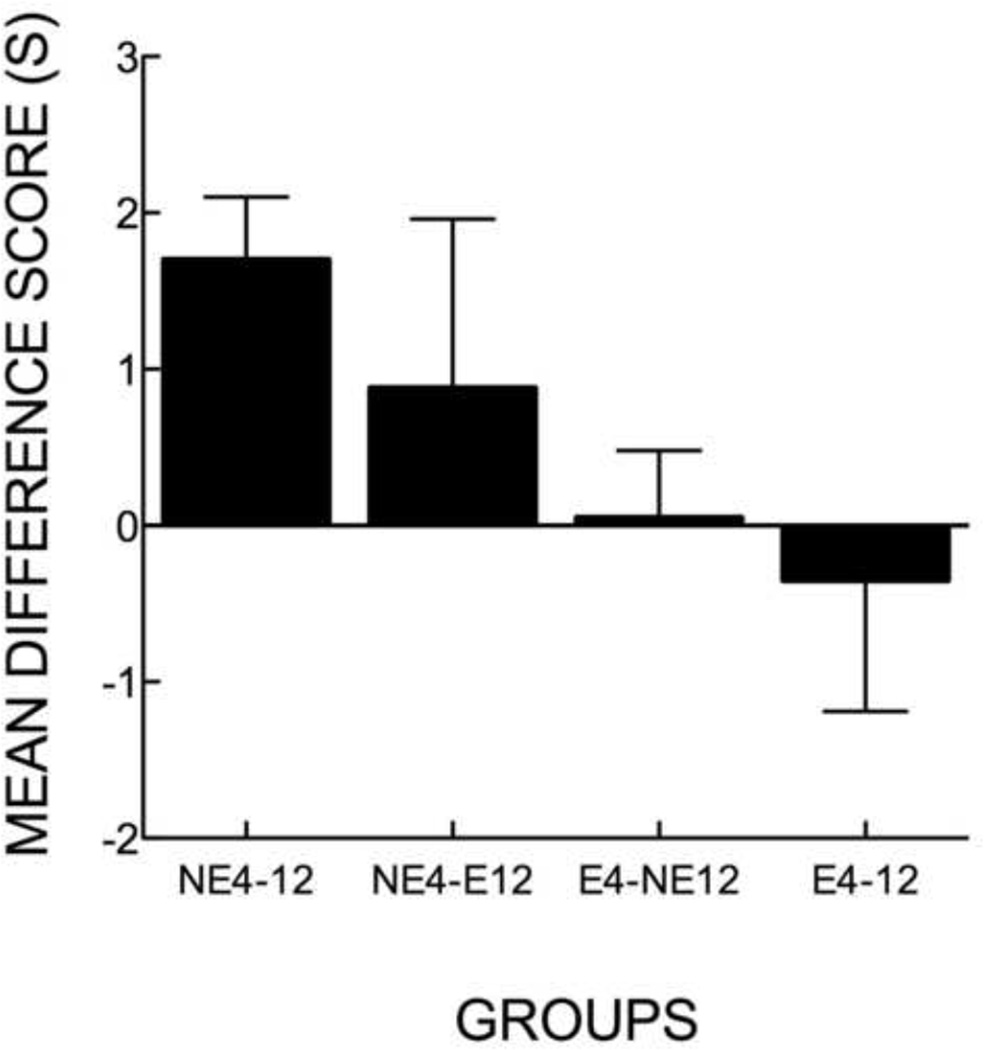

Table 3 and Figure 1 present mean difference scores on the 12-month test for infants in the 4 joint 4-/12-month BDI-II groups. An ANOVA yielded a significant effect, F(3, 64) = 3.40, p = .05, η2 = .137. Post-hoc LSD tests revealed significant mean differences between the non-elevated 4—12 condition and both the elevated 4—12, and the elevated 4—non-elevated 12 conditions (p = .05). Only in the non-elevated 4—12 condition was the difference scores significantly above zero, z = 4.33, p = .01.

Figure 1.

Mean difference scores in seconds for all infants who completed the 12-month test, as a function of joint 4- and 12-month BDI-II category (non-elevated 4—12, n = 35; non-elevated 4—elevated 12, n = 4; elevated 4—non-elevated 12, n = 17; elevated 4—12, n = 12). Error bars denote standard errors of the mean.

Mean ΔF0 in the IDS segment with which the infant was tested correlated more highly with the infant difference scores than was found at 4 months, r = .20, p = .10, 2-tailed. However, a hierarchical linear regression revealed that, with the contribution of ΔF0 accounted for in step 1, there was a significant effect of joint 4-/12-month BDI-II category on 12-month-old infant difference scores in step 2, ΔR2 = .136, F(1, 65) = 10.41, p = .01.

Although none of the mothers who were clinically depressed at 4 months were still in the midst of a major depressive disorder at 12 months, difference scores from the 12-month test were significantly negatively correlated with the postpartum duration of the those mother’s depressive episodes, r = −.72, p = .05, and significantly positively correlated with the postpartum duration of remission from depression (PR and FR combined), r = .77, p = .03. The two infants of mothers who were diagnosed with clinical depression at 12 months but not 4 months each exhibited positive difference scores (2.45 s & 0.90 s, respectively).

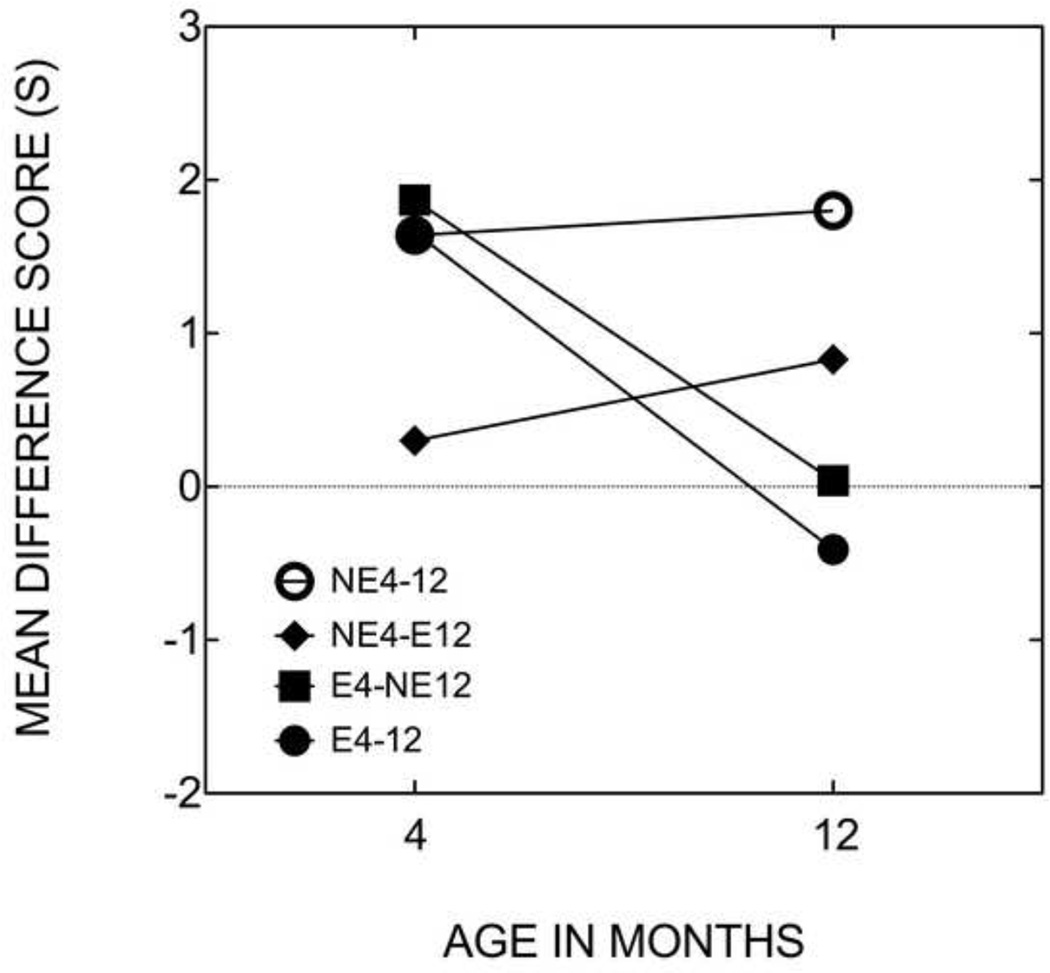

Test of the developmental hypothesis

Sixty-three infants completed learning tests at both 4 and 12. These data were analyzed using a split-plot repeated measures ANOVA, which showed no significant effect of groups, F(3, 58) = 1.99, p = .13, or age, F(1, 58) = 0.14, but a significant groups × age interaction, F(3, 58) = 3.43, p = .05, η2 = .151. Figure 2 shows that infants in the non-elevated 4—12 exhibited positive mean difference scores at both ages with no significant change, t(32) = 0.28, whereas infants in the elevated 4—12 and the elevated 4—non-elevated 12 conditions exhibited declines in mean difference scores between 4 and 12 months of age, t(9) = 2.43, p = .05, and t(15) = 2.67, p = .05, respectively. The small number of infants in the non-elevated 4—elevated 12 condition had lower mean scores than the other groups at 4 months, and exhibited a slight but non-significant increase in difference scores by 12 months, t(3) = 0.37. Nine out of 10 individual infants in the elevated 4—12 condition (90.0%; z = 2.21, p = .02), and 11 out of 16 infants in the elevated 4—non-elevated 12 condition (68.8%; z = 1.25, p = .11) showed lower difference scores at 12 than at 4 months (the proportions in the non-elevated 4—12 and non-elevated 4—elevated 12 conditions were 51.5% and 50.0%, respectively).

Figure 2.

Mean difference scores in seconds calculated from the 4-month and 12-month conditioned-attention tests for infants who completed both tests in the non-elevated 4—12 (n = 33), non-elevated 4— elevated 12 (n = 4), elevated 4—non-elevated 12 (n = 16), elevated 4—12 (n = 10) conditions.

Infant Communicative Development

MCDI-based maternal reports of infant communicative development completed during the 12-month visit provided information on receptive (MCDI-R) and productive (MCDI-P) vocabulary (n = 68). Mothers reported that their 12-month-olds comprehended a mean of 22.5 words (SD = 20.3) and both comprehended and produced a mean of 3.1 words (SD = 5.1). As shown in Table 4, MCDI-R and MCDI-P did not correlate significantly with maternal education, income, marital status, or joint 4- and 12-month BDI-II category. However, MCDI-R correlated significantly with 12-month difference scores obtained from conditioned-attention tests, r = .24, p = .05 (for MCDI-P, r = .15, p = .22).

Table 4.

Correlation Matrix Relating MCDI Performance to Demographic, Diagnostic, and Associative Learning Variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. MCDI-R | -- | .38** | .10 | −.11 | −.09 | −.11 | .24* |

| 2. MCDI-P | -- | −.22 | .01 | .02 | −.09 | .15 | |

| 3. Education | -- | .44** | .33** | −.14 | −.13 | ||

| 4. Income | -- | .55** | −.08 | .00 | |||

| 5. Marital status | -- | −.13 | −.07 | ||||

| 6. Joint 4-/12-BDI-II | -- | −.32 | |||||

| 7. Difference score | -- |

Discussion

Voice-face associative learning was studied in individual infants at 4 and 12 months of age in order to (a) document the apparent decline in responding to an unfamiliar non-depressed mother’s IDS by infants of chronically depressed mothers, (b) assess whether comparatively shorter maternal depressive episodes with early timing would also adversely affect responding in older infants, and (c) examine correlations between this kind of learning and concurrent maternal reports of language development. Consistent with prior work, 4-month-old infants of clinically depressed mothers exhibited significant learning in response to a non-depressed mother’s IDS. At 12 months, although none of the mothers earlier diagnosed with clinical depression were still in the midst of a major depressive episode, infants of mothers with more chronic symptoms of depression -- as measured by elevated BDI-II scores at both 4 and 12 months and, for the subset of mothers with clinical depression, by greater postpartum duration of the mother’s major depressive episode before remission -- exhibited evidence of weaker learning than non-depressed controls. A significant proportion of the infants of mothers with chronically elevated BDI-II scores who completed learning tests at both ages showed poorer learning at 12 than 4 months. Infants of mothers with elevated symptoms of depression at 4 months but not at 12 months also did not on average acquire associations at 12 months, but the proportion of infants who had lower differences scores at 12 than 4 months was not significant. Twelve-month learning scores were positively correlated with concurrent maternal reports of infant receptive, but not productive, communication. At neither age did infant learning correlate significantly with the extent of pitch modulation in the IDS samples. This developmental decline in responding to female IDS was not attributable simply to age or to lower developmental or ecological validity of the conditioned-attention paradigm for older infants, because 12-month-old infants of mothers with continuously non-elevated BDI-II scores exhibited significant learning.

A number of prior studies indicated that deficits in infant development tied to caregiver depression are often more severe or occur only in cases of chronic depression (Campbell & Cohn, 1997; Campbell, Cohn, & Meyers, 1995; Cornish et al., 2005; Diego, Field, & Hernandez-Reif, 2005; Frankel & Harmon, 2006; NICHD ECCRN, 1999). Two other pieces of evidence suggest an experience-based change in infant responding tied to relatively longer durations of maternal depression. First, relatively longer depressive episodes, with or without subsequent remission, are linked to poorer voice-face associative learning in the second six months of life (Kaplan et al., 2004; Kaplan et al., 2011; present study). Second, 5- to 13-month-old infants of currently depressed mothers with perinatal depression onset exhibit poorer learning in comparison with age-matched infants of currently depressed mothers with later depression onset (Kaplan et al., 2004; Kaplan et al., 2011). Interestingly, poor learning in response to female IDS in infants of chronically depressed mothers is accompanied by stronger-than-normal learning to male IDS, at least when the infant’s own parents are married (Kaplan et al., 2009).

However, less clear is whether effects of the duration of elevated symptoms of depression in the first year of life are independent of the timing of those elevated symptoms. Infants in the elevated 4—non-elevated 12 condition did not exhibit significant positive mean difference scores at 12 months, and their mean difference scores did not differ from those in the elevated 4—12 condition (although a few individual infants in the E4-NE12 condition may have carried this effect). These findings, in conjunction with significant learning in 12-month-old infants of currently depressed mothers with late onset of depression (Kaplan et al., 2011), and along with the data from 2 infants of late-onset depressed mothers here, suggest that a depressive episode early in the first year may have a greater effect on 12-month-olds’ learning than depression later in the first year. Nonetheless, despite the lack of precise information about how long the mothers in the elevated 4—non-elevated 12 condition had elevated BDI-II scores, the fact that mothers diagnosed with depression-in-remission who had comparatively longer durations of depression exhibited relatively poorer learning at 12 months implies that, if the timing of a depressive episode is important, it is in conjunction with relatively longer duration. More data will be needed to detect subtle differences and to titrate effects on infant learning attributable to the timing versus the duration of infant learning. It will also be important to follow-up infants beyond 12 months to determine if other effects of early maternal depression on infant learning and cognitive development are delayed in their manifestation.

The current findings are also generally consistent with the latent inhibition/generalized learned irrelevance hypothesis, according to which a history of interactions with relatively withdrawn and insensitive mothers leads infants to “tune-out” maternal IDS, and generalize this to other female, but not male, voices (i.e., “partial generalization,” Kaplan et al., 2004; Kaplan et al., 2010; Kaplan et al., 2011). Further support for this hypothesis comes from the finding that infants’ responding to their own mothers’ IDS is best predicted by the mother’s rated sensitivity in a separate free play interaction, even after demographic variables, antidepressant medication use, and depression diagnosis have been taken into account (Kaplan et al, 2009). Thus, maternal insensitivity mediates the link between maternal depression and infant responding to maternal IDS, which could also account for the non-responsiveness of infants of depressed mothers to normal IDS, as demonstrated here. Poor learning at 12 months in the elevated 4—non-elevated 12 condition can be accommodated under this hypothesis, in that elevated depressive symptoms no doubt persisted beyond 4 months for most mothers in that condition.

There were a number of differences between the current and past studies that suggest caution in accepting their strict comparability, despite detailed similarities in methodology. Specifically, major depressive episodes in the current sample of mothers were apparently relatively briefer than those in the Kaplan et al. (2011) study: in the current study, no mothers who were depressed at 4 months were still depressed at 12 months. In the prior study, 18 mothers of 12-month-olds were clinically depressed (approximately 11% of the sample), and half of them reported in structured clinical interviews that they had continuous major depression since around the time of the infant’s birth. Although the two samples were recruited from the same community population using nominally identical techniques, differences in characteristics of the two samples may have resulted from the different targeted ages (4 vs. 12 months). Perhaps mothers who responded to our recruitment efforts in the first few months after the birth of their child had a higher level of functioning, in comparison to mothers from the same population who only responded later in the first year. The current findings may therefore have greater relevance to mothers with relatively higher educational attainment and who could better cope with their depression, and additional research may be needed to determine if the same effects are obtained when clinical depression diagnoses, rather than elevated self-reported symptoms, are used as the defining criterion for depression.

In addition, there was selective attrition in the current study among mothers with lower educational attainment, suggesting that mothers who participated in the 12-month retest may have not only had relatively mild depression, but also lower demographic risk for delays in cognitive development, than those in previous studies in this series. Perhaps mothers with greater awareness of potential concerns for their infants we more likely to stay in the study.

Infants recruited from EHS centers exhibited significantly higher learning scores in response to the unfamiliar non-depressed mothers’ IDS at 4 months than did infants who were not involved with EHS (see footnote #1). There was no interaction between EHS status and elevated symptoms of depression, but the sample size was very small. The importance of this effect is also unclear because it was not replicated at the 12-month test, but it is still of potential interest. At least one study has demonstrated an effect of sensitivity and stimulation by female childcare workers on cognitive development in 9-month-olds (Albers, Riksen-Walraven, & de Weerth, 2010). A possible explanation is that infants’ experience in the first four months with non-depressed (presumably mainly female) caregivers at EHS centers led to enhanced initial responding to female IDS, but that such responding may have normalized by 12 months. However, EHS mothers were more likely than non-EHS mothers to be ethnic minorities, to be unmarried, and to have lower income, suggesting a number of potential confounds. For example, infants of unmarried mothers may have responded more strongly than infants of married mothers to female voices because, in the absence of extensive interactions with a father, they were more reliant on female caregivers such as EHS staff and extended family members. Infants of unmarried mothers do not learn in response to male IDS in this paradigm (Kaplan et al., 2010). Therefore, this potentially finding calls for additional research with larger sample sizes.

Infant learning in response to non-depressed mothers’ IDS at 12 months correlated significantly with receptive vocabulary scores on the concurrently administered MCDI. Although the MCDI data were based on maternal reports rather than direct observation of infant vocabulary, they represent the first potential indication that learning in response to IDS in this paradigm relates to a more general measure of cognitive functioning. The absence of a significant correlation between reports of productive vocabulary and infant learning may have been due to a floor effect, because most infants were reported to have very small productive vocabularies, and 28 of them (41.2%) were reported to utter no words at all. Also, there was no effect of joint 4-month/12-month BDI-II category on MCDI-R, but sample sizes were small.

At present, no causal connection can be made between voice-face associative learning and child language development. However, this finding is consistent with work by Tsao, Liu, and Kuhl (2004), who found that 6-month-olds trained on a phoneme discrimination task who reached an operant head-turning discrimination criterion relatively faster at 6 months had higher later MCDI-based word comprehension. Tsao et al. hypothesized that infants skilled in detecting phonetic differences may progress faster in the process of language acquisition, but they acknowledged that higher general cognitive development, such as greater attention and learning abilities, may have sped discrimination through faster acquisition of an associative contingency.

There were some limitations to the current study. The relatively small number of participants per cell has already been mentioned several of times. This limited our statistical power and suggests the need for confirmatory follow-up work. Also, that groups had to be defined by BDI-II category rather than DSM-IV diagnosis is a limitation, because elevated BDI-II scores could indicate depression, or instead more general psychiatric disturbance or adjustment issues. In addition, more frequent assessments of maternal depressive symptoms would have been useful in analyses of the duration and timing of depression on 12-month learning failures.

In conclusion, the finding of a progressive decline in responding to IDS by infants of mothers with chronically elevated self-report symptoms of depression supports the hypothesis that an infant’s experience during dyadic interactions contributes to the learning-promoting effects of IDS in this paradigm. It is consistent with the “social gating” hypothesis of language acquisition (Kuhl, 2007), according to which parents use of IDS, and the arousal and attention generated by contingent parental responding, increases the robustness and durability of word-object associations acquired during joint attentional states. It also raises concerns about how well older infants of depressed mothers will initially respond to childcare arrangements and interventions involving non-depressed female caregivers or therapists. Interventions mid-way through the first year of the infant’s life may be effective at preventing the partially generalized associative learning deficit identified here. Although this kind of learning deficit has been so far only minimally linked to a broader cognitive deficit, given the important roles that have been documented for maternal IDS in infant attention, learning, and speech and language development (Liu et al., 2003; Singh et al., 2009; Thiessen et al., 2005), and the centrality of association learning as a tool with which infants can learn about the world around them (Rovee-Collier, 1986), it is reasonable to hypothesize that interventions aimed at re-establishing the relevance of female IDS will improve child cognitive and language functioning.

Research Highlights.

Four-month-old infants of mothers with non-elevated or elevated self-report symptoms of depression learned to associate a segment of an unfamiliar non-depressed mother’s infant-directed speech (IDS) with an image of a smiling face that followed it.

In contrast, when the same infants were retested at 12 months, infants whose mothers had chronically elevated self-report symptoms, and those with elevated self-report symptoms at 4 months but not 12 months, did not learn the association.

Although none of the mothers was clinically depressed at 12 months postpartum, the strength of learning at 12 months was negatively correlated for the postpartum duration of their now at least partially remitted clinical depression.

Learning scores at 12 months correlated positively with maternal reports of infant receptive vocabulary at 12 months.

We conclude that the learning-promoting effects of IDS depend on the experience with a depressed caregiver.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by NICHD Grant HD049732 to PSK. We thank Michael Zinser and Kevin Everhart for providing clinical training and supervision of interviewers, and Amy Albers, Angela Bruns, Aaron Burgess, Matthew Boland, Andres Diaz, Katharine Gannon, Daniel Lemel, Megan McCartle, Jennifer Randolph, Jennifer Ratzlaff, Jason Roth, Drew Sall, Jessica Sliter, and Susan Sullivan, for their assistance in data collection.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Difference scores in response to an unfamiliar non-depressed mother’s IDS at 4 months varied based on recruiting source. Infants of mothers recruited from EHS Centers had significantly higher mean difference scores than those recruited from magazine advertisements at 4 months (M = 3.22 s, SD = 2.1, n = 6, vs. M = 1.45 s, SD = 2.0, n = 81, F(1, 85) = 4.53, p = .05, η2 = .050). However, recruiting source did not interact with depression diagnosis or joint BDI-II category to affect mean difference scores. Furthermore, in the 12-month test, difference scores did not differ significantly as a function of recruiting sources (EHS Centers vs. magazine advertisements; M = 0.19 s, SD = 1.3, n = 4, vs. M = 0.94 s, SD = 2.5, F(1, 66) = 0.35.

References

- Albers EM, Riksen-Walraven JM, de Weerth C. Developmental stimulation in child care centers contributes to young infants’ cognitive development. Infant Behavior & Development. 2010;33:401–408. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2010.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: Author; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. BDI-II: 2nd Edition Manual. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Beck A, Ward C, Mendelson M, Mach J, Erbaugh J. An inventory for measuring depression. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1961;4:561–571. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bettes B. Maternal depression and motherese: Temporal and intonational features. Child Development. 1988;59:1089–1096. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1988.tb03261.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biringen Z, Robinson J. Emotional availability: A reconceptualization for research. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1991;61:258–271. doi: 10.1037/h0079238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boersma P, Weenink D. Praat: doing phonetics by computer. 2009 (Version 5.1.05) [Computer program]. Retrieved from http://www.praat.org/ [Google Scholar]

- Campbell SB, Cohn JF. The timing and chronicity of postpartum depression: Implications for infant development. In: Murray L, Cooper P, editors. Postpartum depression and child development. New York: Guilford; 1997. pp. 85–110. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell SB, Cohn JF, Meyers TA. Depression in first-time mothers: Mother-infant interaction and depression chronicity. Developmental Psychology. 1995;31:349–357. [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Rogosch FA, Toth SL. The efficacy of toddler-parent psychotherapy for fostering cognitive development in offspring of depressed mothers. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2000;28:135–148. doi: 10.1023/a:1005118713814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornish AM, McMahon CA, Ungerer JA, Barnett B, Kowalenko N, Tennant C. Postnatal depression and infant cognitive and motor development in the second postnatal year: The impact of depression chronicity and infant gender. Infant Behavior & Development. 2005;28:407–417. [Google Scholar]

- Diego MA, Field T, Hernandez-Reif M. Prepartum, postpartum, and chronic effects on neonatal behavior. Infant Behavior & Development. 2005;28:155–164. [Google Scholar]

- Fenson L, Dale PS, Reznick JS, Bates E, Thal D, Pethick S. Variability in early communicative development. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 1994;59(5) Serial # 242. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenson L, Pethick S, Renda C, Cox JL, Dale PS, Reznick JS. Short-form versions of the MacArthur Communicative Development Inventories. Applied Psycholinguistics. 2000;21:95–116. [Google Scholar]

- Fernald A. The perceptual and affective salience of mothers’ speech to infants. In: Feagans L, Garvey C, Golinkoff R, editors. The origins and growth of communication. NJ: Ablex; 1984. pp. 5–29. [Google Scholar]

- Fernald A, Kuhl PK. Acoustic determinants of infant preference for motherese speech. Infant Behavior & Development. 1987;8:181–195. [Google Scholar]

- First M, Spitzer R, Gibbon M, Williams B. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I disorders. Patient Edition)_(SCID-I/P, Version 2.0) Biometric Research Department., NYS Psychiatric Institute; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Frankel KA, Harmon RJ. Depressed mothers: They don’t always look as bad as they feel. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1996;35:289–298. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199603000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hay DF. Postpartum depression and cognitive development. In: Murray L, Cooper PJ, editors. Postpartum depression and child development. New York: The Guilford Press; 1997. pp. 85–110. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan PS, Bachorowski J, Smoski MJ, Zinser M. Role of clinical diagnosis and medication use in effects of maternal depression on IDS. Infancy. 2001;2:537–548. doi: 10.1207/S15327078IN0204_08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan PS, Bachorowski J-A, Smoski MJ, Hudenko WJ. Infants of depressed mothers, although competent learners, fail to acquire associations in response to their own mothers’ IDS. Psychological Science. 2002;13:268–271. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.00449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan PS, Bachorowski J-A, Zarlengo-Strouse P. Child-directed speech produced by mothers with symptoms of depression fails to promote associative learning in four-month old infants. Child Development. 1999;70:560–570. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan P, Burgess A, Sliter J, Moreno A. Maternal sensitivity and the learning promoting effects of depressed and nondepressed mothers' infant-directed speech. Infancy. 2009;14:143–161. doi: 10.1080/15250000802706924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan PS, Danko CM, Diaz A. A privileged status for male infant-directed speech in infants of depressed mothers? Role of father involvement. Infancy. 2010;15:151–175. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7078.2009.00010.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan PS, Danko CM, Diaz A, Kalinka CJ. An associative learning deficit in 1-year-old infants of depressed mothers: Role of depression duration. Infant Behavior & Development. 2011;34:35–44. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2010.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan PS, Dungan JK, Zinser MC. Infants of chronically depressed mothers learn in response to male, but not female, IDS. Developmental Psychology. 2004;40:140–148. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.40.2.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan PS, Fox KB, Huckeby ER. Faces as reinforcers: Effects of facial expression and pairing condition. Developmental Psychobiology. 1992;25:299–312. doi: 10.1002/dev.420250407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan P, Jung PC, Ryther JS, Zarlengo-Strouse P. Infant-directed versus adult-directed speech as signals for faces. Developmental Psychology. 1996;32:880–891. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan PS, Sliter JK, Burgess AP. Infant-directed speech produced by fathers with symptoms of depression: Effects on infant associative learning in a conditioned-attention paradigm. Infant Behavior & Development. 2007;30:535–545. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2007.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhl PK. Is speech “gated” by the social brain? Developmental Science. 2007;10:110–120. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2007.00572.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linden DR, Savage LM, Overmeier JB. General learned irrelevance: A Pavlovian analog to learned helplessness. Learning & Motivation. 1997;28:230–247. [Google Scholar]

- Liu H-M, Kuhl PK, Tsao F-M. An association between mothers’ speech clarity and infants’ speech discrimination skills. Developmental Science. 2003;6:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Lubow R. Latent inhibition and conditioned attention theory. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Lubow RE, Josman ZE. Latent inhibition deficits in hyperactive children. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2006;34:959–973. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1993.tb01101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma W, Golinkoff RM, Houston D, Hirsh-Pasek K. Word learning in infant-and adult-directed speech. Language Learning & Development. 2011;7:185–201. doi: 10.1080/15475441.2011.579839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milgrom J, Westley DT, Gemmell AW. The mediating role of maternal responsiveness in some longer term effects of postnatal depression on infant development. Infant Behavior & Development. 2004;27:443–454. [Google Scholar]

- Murray L. The impact of postnatal depression on infant development. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1992;33:543–561. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1992.tb00890.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NICHD Early Child Care Research Network. Chronicity of maternal depressive symptoms, maternal sensitivity, and child functioning at 36 months. Developmental Psychology. 1999;35:1297–1310. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.35.5.1297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rovee-Collier C. The rise and fall of infant classical conditioning research: its promise for the study of early development. Advances in Infancy Research. 1986;4:139–159. [Google Scholar]

- Singh L, Nestor S, Parikh C, Yull A. Influences of infant-directed speech on early word recognition. Infancy. 2009;14:654–666. doi: 10.1080/15250000903263973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley C, Murray L, Stein A. The effect of postnatal depression on mother-infant interaction, infant response to the still-face perturbation, and performance on an Instrumental Learning task. Development and Psychopathology. 2004;16:1–18. doi: 10.1017/s0954579404044384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steer RA, Ball R, Ranieri WF, Beck AT. Further evidence for the construct validity of the Beck Depression Inventory-II with psychiatric outpatients. Psychiatric Reports. 1997;80:443–446. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1997.80.2.443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiessen ED, Hill EA, Saffran JR. Infant-directed speech facilitates word segmentation. Infancy. 2005;7:53–71. doi: 10.1207/s15327078in0701_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsao F-M, Liu H-M, Kuhl PK. Speech perception in infancy predicts language development in the second year of life: A longitudinal study. Child Development. 2004;75:1067–1084. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00726.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zlochower AJ, Cohn JF. Vocal timing in face-to-face interaction in clinically depressed and nondepressed mothers and their 4-month-old infants. Infant Behavior & Development. 1996;19:371–374. [Google Scholar]