Abstract

Purpose. Human papillomavirus (HPV) as a risk factor for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) has previously been studied, but importance of HPV status in ESCC for prognosis is less clear. Methods. A total of 105 specimens with ESCC were tested by in situ hybridization for HPV 16/18 and immunohistochemistry for p16 expression. The 5-year overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival were calculated in relation to these markers and the Cox proportional hazards model was used to determine the hazard ratio (HR) of variables in univariate and multivariate analysis. Results. HPV was detected in 27.6% (29) of the 105 patients with ESCC, and all positive cases were HPV-16. Twenty-five (86.2%) of the 29 HPV-positive tumors were stained positive for p16. HPV infected patients had better 5-year rates of OS (65.9% versus 43.4% among patients with HPV-negative tumors; P = 0.002 by the log-rank test) and had a 63% reduction in the risk of death (adjusted HR = 0.37, 95% CI = 0.16 to 0.82, and P = 0.01). Conclusions. HPV infection may be one of many factors contributing to the development of ESCC and tumor HPV status is an independent prognostic factor for survival among patients with ESCC.

1. Introduction

Esophageal cancer is the eighth most common cancer and the sixth most common cause of death from cancer, worldwide [1, 2]. Once developed, esophageal cancer usually rapidly invades surrounding tissues and lymph nodes [3]. Due to the absence of early symptoms, invasiveness of the disease, and its late diagnosis, it is generally associated with a poor prognosis [4]. Despite increasing rates of esophageal adenocarcinoma in many western countries, esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) remains the dominant histological type of esophageal cancer worldwide. ESCC is still the main cancer burden and the fourth most common cause of death in China [5], especially northern China [6], and thus is the focus of this study.

The etiology of ESCC remains unclear, and epidemiological studies suggest that tobacco smoking, heavy alcohol drinking, micronutrient deficiency [7, 8], and dietary carcinogen exposure may cause the malignancy. Infectious agents have been implicated, as either direct carcinogens or promoters. In particular, human papillomavirus (HPV) has been postulated as a possible cause of ESCC [9]. HPV infection in esophageal cancer was first suggested in 1982 based on histological observations [10]. Subsequent studies using various methods have confirmed the presence of HPV in ESCC [9, 11].

HPV types 16 and 18 are known to cause the majority of squamous cell carcinomas of the cervix [12–15] and are strongly associated with cancers of the head and neck, particularly the oropharynx [16–18]. The viral oncogene products E6 and E7 play a key role in HPV-associated carcinogenesis, abrogating p53 and retinoblastoma tumor suppressor functions, respectively [19, 20]. E7 binds to and degrades Rb, releasing E2F, leading to p16INK4A overexpression, hereafter denoted as p16, which is associated with superior clinical outcome [21, 22]. Thus HPV-positive tumors are characterized by high expression of p16 [23–25] and p16 is widely considered a surrogate marker for HPV infection in the context of squamous cell carcinoma [21, 25].

Some retrospective clinical studies have consistently proved that patients with HPV-positive head and neck squamous cell carcinoma had a better prognosis than patients with HPV-negative tumors [21, 26–28]. Esophagus can be infected with these viruses in the same way as the oral cavity, tonsils, and pharynx; it is supposed that the histological similarities between the head and neck squamous epithelia and esophagus would suggest a similar association and clinical characteristics. The prognostic value of the HPV status has previously been investigated in patients with ESCC. However, the results are much controversial [29–31].

With the present study, we aim to determine the prevalence of HPV infection in ESCC and evaluate its clinical significance. We also sought to evaluate the effect of tumor HPV status on survival of patients with ESCC in northern China.

2. Patients and Methods

2.1. Patients and Tissues Samples

A total of 279 patients with primary esophageal carcinoma treated with surgery, admitted to the Oncology Center, Qilu Hospital of Shandong University, were identified from December 2006 to January 2008. This hospital is located in Shandong province, which was a high-incidence area for ESCC in China [32]. Patients treated with neoadjuvant therapy, which could potentially interfere with the prevalence of HPV, were excluded, as were patients who died within 30 days after surgery. The additional exclusion criteria comprised the nonsquamous cell subtype and uncooperative patients unable to answer questions or who could not be contacted. A total of 184 patients met the protocol study criteria. All patients provided their written informed consent regarding this study, and the protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Qilu Hospital of Shandong University (documentation no. 2012178). Attempts were made to retrieve paraffin blocks from pathology laboratories at which the patients were diagnosed. Of these, pathology review established that samples from 105 patients had sufficient ESCC tumor tissue to detect HPV and p16. Serial 4 μm sections were cut from each patient's tumor tissue. One representative section was stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) to ensure the tissue derived from esophageal cancer. The other sections were prepared for detection. All slides were reviewed by a pathologist specializing in gastrointestinal pathology.

2.2. Followup

Postoperative follow-up data were obtained from all patients. The following parameters were studied: gender, age, tumor location, postoperative pathological T and N status (pT and pN), TNM staging according to American Joint Committee on Cancer TNM staging system, differentiation grade of the tumor, adjuvant therapy (postoperative radiotherapy with or without chemotherapy), and smoking and alcohol habits. Anatomical localization of the tumor was grouped into an upper part (15–24 cm), a middle part (25–34 cm), and a lower part of the esophagus (35–46 cm). The tumor status was characterized into localized (primary tumor with or without local node metastases) or advanced disease (with distant metastases). Alcohol intake cutoff point was 0.025 kg/day. The cutoff value was based on the 2011 Chinese Inhabitant Dietary Guideline.

All patients had a regular follow-up schedule including a complete history and physical examination every 3 months during the first 2 years after surgery and every 6 months thereafter. Routine radiological examinations and esophagoscopy were performed when necessary. Patients were followed until death or for a maximum of 5 years.

2.3. HPV Detection

All specimens were evaluated for HPV-16 and HPV-18 with using the in situ hybridization-catalyzed signal amplification method for biotinylated probes (GenPoint, Dako). Briefly, sections underwent conventional deparaffinization, heat-induced target retrieval was performed, and digestion using proteinase K and then HPV-16 biotinylated DNA probe (GenPoint, Dako) was applied. Sections were then denatured and stained with diaminobenzidine detection system. Sections were counterstained with hematoxylin. All tumors were further evaluated for HPV-18 by means of HPV-18 biotinylated DNA probe (GenPoint, Dako). The positive control was a cervical squamous cell carcinoma sample, whereas the negative control was obtained by omitting the HPV probe. All slides were scored as positive or negative. Brown staining confined to nuclei of infected tumor cells was defined positive. All scorings were conducted with no knowledge of p16 immunohistochemistry status.

2.4. P16INK4A Immunohistochemistry

P16 immunohistochemical detection was done as described previously [33]. Briefly, after formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tumor specimens were deparaffinized, antigen retrieval was performed by use of heat-induced epitope retrieval with Tris-EDTA (PH = 9.0, Dako) according to the manufacturer's recommendations. Processions were carried out by the Dako Envision-System method (code: GK500705) using a primary antibody against p16 (monoclonal mouse anti-human p16INK4A protein, Clone G175-405, Dako). A p16-positive tumor was used as a positive control; negative controls were obtained by omitting the primary antibody. P16-positive was defined as >50% of cells showing strong nuclear and cytoplasm immunolabeling. All scorings were conducted with no knowledge of clinical characteristics or outcome.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

All analyses were performed using SPSS 16 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). Statistical analyses included univariate analyses of demographic and postoperative outcome data. For these analyses, the differences between the groups were tested for significance using the Mann-Whitney test for continuous variables and the chi-square test or Fisher's exact test for categorical variables and the Kruskal-Wallis test for ranked data. The Kaplan-Meier method and log-rank test were used for analysis and comparison of survival curves. The primary end point was overall survival (OS), defined as the time from date of surgery to death. Secondary end points included progression-free survival (PFS), defined as the time from date of surgery to death or the first documented relapse, which was categorized as local-regional disease (tumor at the primary site or regional nodes) or distant metastases. Death from the primary cancer without a documented site of recurrence or death from an unknown cause was considered death from local-regional disease. PFS and its components were adopted to facilitate comparison with published meta-analyses [34]. The Cox proportional hazards model was used to determine the hazard ratio (HR) of variables on 5-year OS and PFS in univariate and multivariate analysis. The results were given as HRs with their 95% confidence interval (CI). P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics

A total of 105 patients (84 males and 21 females) met the protocol study criteria for analysis. The median age of the patients was 60 (range: 42–78) years at the date of surgery. Patients were divided into two groups according to the tumor HPV status. Baseline characteristics of HPV-positive and HPV-negative patients are shown in Table 1. There were no significant differences between the groups with respect to gender (P = 0.66), age (P = 0.22), pT status (P = 0.18), pN status (P = 0.27), TNM stage (AJCC) (P = 0.14), differentiation grade (P = 0.21), adjuvant therapy (P = 0.41), smoking (P = 0.13), and alcohol consumption (P = 0.78) and only marginally associated with tumor location (P = 0.07).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the study patients and their tumors, according to tumor HPV status.

| Characteristics | Total (N = 105) no. (%) |

HPV-positive (N = 29) no. (%) |

HPV-negative (N = 76) no. (%) |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 84 (80.0) | 24 (82.8) | 60 (78.9) | 0.66 |

| Female | 21 (20.0) | 5 (17.2) | 16 (21.1) | |

| Age | ||||

| Median (range) | 60 (42–78) | 60 (44–75) | 62 (42–78) | 0.22△ |

| Tumor location | ||||

| Cervical/upper | 11 (10.5) | 6 (20.7) | 5 (6.6) | 0.07 |

| Middle | 49 (46.7) | 14 (48.3) | 35 (46.1) | |

| Low | 45 (42.9) | 9 (31.0) | 36 (47.4) | |

| pT status | ||||

| pT1 | 20 (19.0) | 7 (24.1) | 13 (17.1) | 0.18☆ |

| pT2 | 22 (21.0) | 7 (24.1) | 15 (19.7) | |

| pT3 | 58 (55.2) | 15 (51.8) | 43 (56.6) | |

| pT4 | 5 (4.8) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (6.6) | |

| pN status | ||||

| pN0 | 68 (64.8) | 21 (72.4) | 47 (61.8) | 0.27☆ |

| pN1 | 25 (23.8) | 6 (20.7) | 19 (25.0) | |

| pN2 | 10 (9.5) | 2 (6.9) | 8 (10.5) | |

| pN3 | 2 (1.9) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (2.6) | |

| TNM stage (AJCC) | ||||

| I | 23 (21.9) | 7 (24.1) | 16 (21.1) | 0.14 |

| II | 49 (46.7) | 17 (58.6) | 32 (42.1) | |

| III | 33 (31.4) | 5 (17.2) | 28 (36.8) | |

| Differentiation grade | ||||

| Well | 27 (25.7) | 11 (37.9) | 16 (21.1) | 0.21 |

| Moderate | 44 (41.9) | 10 (34.5) | 34 (44.7) | |

| Poor | 34 (32.4) | 8 (27.6) | 26 (34.2) | |

| Adjuvant therapy | ||||

| No | 61 (58.1) | 15 (51.7) | 46 (60.5) | 0.41 |

| yes | 44 (41.9) | 14 (48.3) | 30 (39.5) | |

| Pack-years of smoking※ | ||||

| <20 | 42 (40.0) | 15 (51.7) | 27 (35.5) | 0.13 |

| ≥20 | 63 (60.0) | 14 (48.3) | 49 (64.5) | |

| Alcohol intake (kg/day) | ||||

| <20 | 53 (50.5) | 14 (48.3) | 39 (51.3) | 0.78 |

| ≥20 | 52 (49.5) | 15 (51.7) | 37 (48.7) |

AJCC: American Joint Commission on Cancer Staging; Pt: pathological tumor stage; pN: pathological node stage.

☆ P values were calculated with the use of the Kruskal-Wallis test.

△ P values were calculated with the use of the Mann-Whitney test.

※A pack-year is defined as the equivalent of smoking one pack of cigarettes per day for 1 year.

3.2. Analysis of HPV and p16

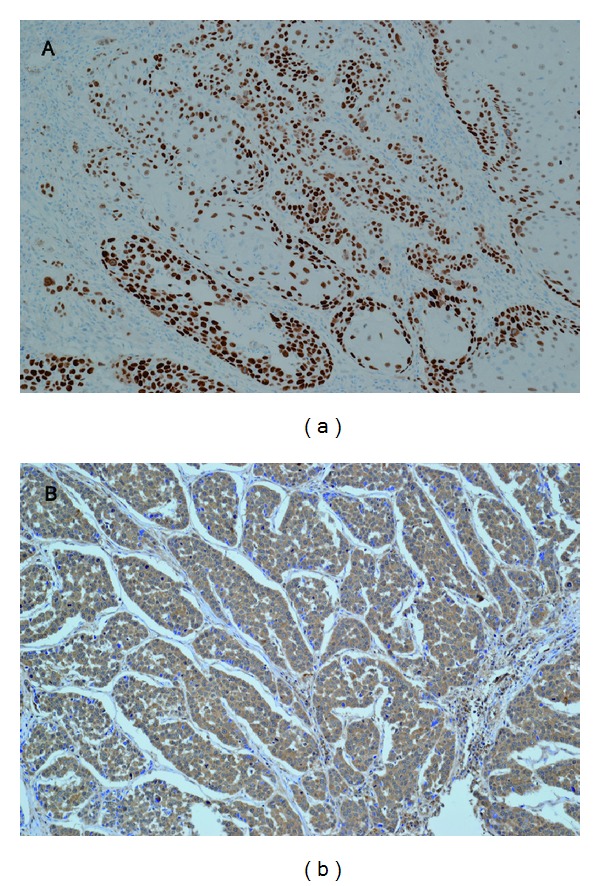

Twenty-nine (27.6%) of the 105 ESCC patients were determined to be HPV-positive by in situ hybridization, and all positive cases were HPV-16 (Figure 1(a)); none were positive for HPV-18 DNA. The median age of the HPV-positive group was 60 years (range: 44–75 years) and 62 years (range: 42–78 years) in the HPV-negative group. Twenty-five (86.2%) of 29 HPV-positive tumors were stained positive for p16 with immunohistochemistry (Figure 1(b)). P16 expression was strongly associated with HPV positivity (86.2% in HPV-positive tumors versus 18.4% in HPV-negative tumors, P < 0.001) (Table 2).

Figure 1.

(a) In situ hybridization signal of HPV-positive esophageal squamous cell carcinomas. Numerous tumor cells show positive nuclear signals. (b) Immunohistochemical staining of p16INK4A in esophageal squamous cell carcinomas. More than 50% of tumor cells showing strong nuclear and cytoplasm immunolabeling. (Original magnification ×200.)

Table 2.

Correlation between HPV in situ hybridization and p16 immunohistochemistry in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma.

| p16 status | Total (N = 105) no. (%) |

HPV-positive (N = 29) no. (%) |

HPV-negative (N = 76) no. (%) |

P value | Kappa value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive | 39 (37.1) | 25 (86.2) | 14 (18.4) | <0.001 | 0.61 |

| Negative | 66 (62.9) | 4 (13.8) | 62 (81.6) |

P and Kappa values were calculated with the use of Pearson's chi-square test and Cohen Kappa test, respectively.

3.3. Survival Analysis

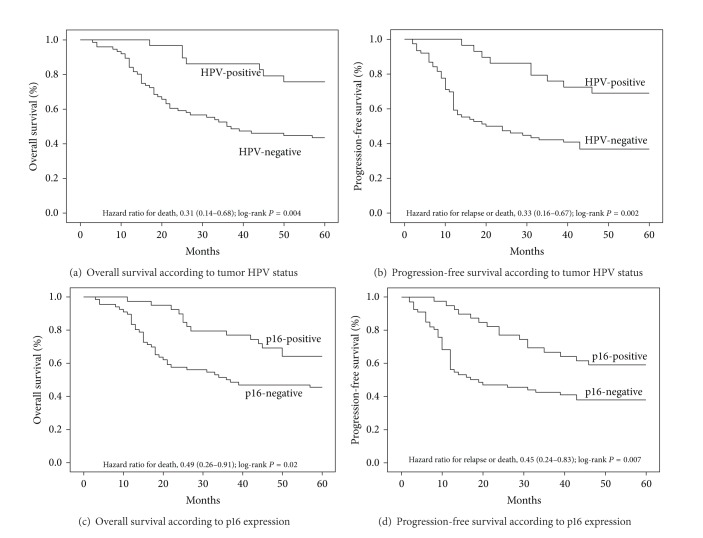

Based on Kaplan-Meier analysis, patients with HPV-positive tumors had better survival than patients with HPV-negative ones (P = 0.002, log-rank test). The 5-year rates of OS were 65.9% in the HPV-positive subgroup and 43.4% in the HPV-negative one (Figure 2(a)). HPV-positive patients also had statistically significantly better PFS than HPV-negative patients (P = 0.001, log-rank test). The 5-year rates of PFS were 61.8% and 36.8%, respectively (Figure 2(b)). Tumors were evaluated for the expression of not only HPV but also a known biomarker of HPV oncoprotein function, the cyclin-dependent-kinase inhibitor p16, which is minimally detectable in HPV-negative tumors [35]. The presence of HPV and p16 expression in tumors had a good agreement (kappa = 0.61; 95% CI: 0.45 to 0.77). Using p16 expression as a stratification factor, we found differences in OS and PFS that were consistent with those based on HPV status. The 5-year rates of OS were 64.1% in the subgroup that was positive for p16 expression and 45.5% in the negative subgroup (P = 0.021, log-rank test) (Figure 2(c)). The 5-year rates of PFS were 58.7% and 37.9%, respectively (P = 0.007, log-rank test) (Figure 2(d)).

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier estimates of survival among the study patients, according to tumor HPV status or p16-expression status. For 5-year overall survival rate (a) and 5-year progression-free survival rate (b), HPV was significantly associated with improved outcomes (P = 0.002, P = 0.001, resp.). For 5-year OS rate (c) and 5-year progression-free survival rate (d), p16 was significantly associated with improved outcomes (P = 0.021, P = 0.007, resp.).

Univariate analysis was performed to evaluate factors potentially associated with OS and PFS (Table 3). Gender, age, tumor location, differentiation grade of the tumor, adjuvant therapy, and alcohol habits were not important determinants of survival or PFS. However, pT and pN status, TNM staging, and smoking and tumor HPV status were associated with OS or PFS. T status (T1/T2 versus T3/T4, HR = 3.44, and 95% CI = 1.85 to 6.40), N status (N0 versus N1/N2/N3, HR = 2.71, and 95% CI = 1.55 to 4.73), TNM stage (AJCC stage I/II versus III/IV, HR = 3.04, and 95% CI = 1.74 to 5.32), and tumor HPV status (positive versus negative, HR = 3.26, and 95% CI = 1.46 to 7.25) were associated with OS. T status (T1/T2 versus T3/T4, HR = 2.42, and 95% CI = 1.40 to 4.19), N status (N0 versus N1/N2/N3, HR = 2.79, and 95% CI = 1.66 to 4.72), TNM stage (AJCC stage I/II versus III/IV, HR = 2.66, and 95% CI = 1.57 to 4.50), and tumor HPV status (positive versus negative, HR = 3.01, and 95% CI = 1.50 to 6.17) were associated with PFS. The association of tumor HPV status with survival could not be explained by smoking: patients with HPV-positive tumors with or without a history of smoking had a similar reduction in risk of mortality when compared with their HPV-negative counterparts. Tobacco smoking was also associated with OS and PFS both in the subgroup of patients (<20 versus ≥20, HR = 1.88, and 95% CI = 1.03 to 3.45 and HR = 1.96 and 95% CI = 1.11 to 3.45, resp.).

Table 3.

Cox univariate analysis for 5-year survival and progression-free survival in the study patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma.

| Parameters | Univariate analysis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5-yr overall survival | 5-yr progression-free survival | |||||

| HR | 95% CI | P value | HR | 95% CI | P value | |

| Gender | 1.29 | 0.68–2.47 | 0.44 | 1.32 | 0.71–2.45 | 0.38 |

| Male versus female | ||||||

| Age | 0.98 | 0.56–1.70 | 0.93 | 0.85 | 0.51–1.44 | 0.55 |

| <60 versus ≥60 | ||||||

| Location | 0.75 | 0.30–1.89 | 0.54 | 0.66 | 0.28–1.55 | 0.34 |

| Cervical/upper versus middle/low | ||||||

| Differentiation | 1.01 | 0.56–1.81 | 0.99 | 1.12 | 0.58–2.14 | 0.74 |

| Well/moderate versus poor | ||||||

| pT status | 3.44 | 1.85–6.40 | <0.001 | 2.42 | 1.40–4.19 | 0.002 |

| T1/T2 versus T3/T4 | ||||||

| pN status | 2.71 | 1.55–4.73 | <0.001 | 2.79 | 1.66–4.72 | 0.001 |

| N0 versus N1/N2/N3 | ||||||

| TNM stage | 3.04 | 1.74–5.32 | <0.001 | 2.66 | 1.57–4.50 | <0.001 |

| I/II versus III/IV | ||||||

| Adjuvant therapy | 0.75 | 0.54–1.53 | 0.35 | 0.51 | 0.45–1.28 | 0.12 |

| No versus yes | ||||||

| Pack-years of smoking | 1.88 | 1.03–3.45 | 0.04 | 1.96 | 1.11–3.45 | 0.02 |

| <20 versus ≥20 | ||||||

| Alcohol intake (kg/day) | 1.66 | 0.95–2.92 | 0.08 | 1.61 | 0.95–2.73 | 0.06 |

| <0.025 versus ≥0.025 | ||||||

| Tumor HPV status | 0.31 | 0.14–0.68 | 0.004 | 0.33 | 0.16–0.67 | 0.002 |

| Negative versus positive | ||||||

| Tumor HPV status | 3.26 | 1.46–7.25 | 0.004 | 3.01 | 1.50–6.17 | 0.002 |

| Positive versus negative | ||||||

HR: hazard ratio; CI: confidence interval; a pack-year: the equivalent of smoking one pack of cigarettes per day for 1 year.

We then performed multivariable analysis to estimate the association of tumor HPV status with survival outcomes (Table 4). In this analysis, T status (T1/T2 versus T3/T4, adjusted HR = 2.65, 95% CI = 1.39 to 5.05, and P = 0.003), N status (N0 versus N1/N2/N3, adjusted HR = 2.07, 95% CI = 1.16 to 3.72, and P = 0.01), and TNM stage (I/II versus III/IV, adjusted HR = 1.91, 95% CI = 0.28 to 2.43, and P = 0.04) were associated with degraded mortality risk after adjustment for smoking and tumor HPV status. Tumor HPV status was independently associated with mortality risk after adjustment for pT status, pN status, TNM stage, and smoking: patients with HPV-positive tumors had a 63% lower risk of death than patients with HPV-negative (adjusted HR = 0.37, 95% CI = 0.16 to 0.82, and P = 0.01). After adjustment for pT status, pN status, TNM stage, and smoking, tumor HPV status was also statistically significantly associated with PFS. Patients with HPV-positive tumors had a risk of progression that was 62% lower than that of patients with HPV-negative tumors (adjusted HR = 0.38, 95% CI = 0.18 to 0.77, and P = 0.008).

Table 4.

Multivariate Cox analysis for 5-year survival and progression-free survival in the study patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma.

| Parameters | Multivariate analysis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5-yr overall survival | 5-yr progression-free survival | |||||

| HR | 95% CI | P value | HR | 95% CI | P value | |

| pT status | 2.65 | 1.39–5.05 | 0.003 | 2.09 | 1.17–3.72 | 0.01 |

| T1/T2 versus T3/T4 | ||||||

| pN status | 2.07 | 1.16–3.72 | 0.01 | 2.14 | 1.24–3.68 | 0.006 |

| N0 versus N1/N2/N3 | ||||||

| TNM stage | 1.91 | 0.28–2.43 | 0.04 | 0.48 | 0.15–2.47 | 0.03 |

| I/II versus III/IV | ||||||

| Pack-years of smoking | 1.84 | 1.00–3.39 | 0.06 | 1.94 | 1.09–3.44 | 0.02 |

| <20 versus ≥20 | ||||||

| Tumor HPV status | 0.37 | 0.16–0.82 | 0.01 | 0.38 | 0.18–0.77 | 0.008 |

| Positive versus negative | ||||||

HR: hazard ratio; CI: confidence interval; a pack-year: the equivalent of smoking one pack of cigarettes per day for 1 year.

4. Discussion

HPV is a small double-stranded DNA virus with tropism for the squamous epithelium where it can cause hyperproliferative lesions [19]. There are more than 130 HPV types identified and these have been classified into low- or high-risk groups according to their potential for oncogenesis [36]. The high-risk HPV types are closely related to malignancies. According to previous studies, HPV-16 is the most prevalent type in squamous cell carcinoma, followed by HPV-18 [37], while other high-risk HPV types are rare [38, 39].

The etiological role of HPV in ESCC is still unclear. The incidence of HPV in ESCC varies between different geographical areas [9]. It is postulated that areas with high incidence of esophageal carcinoma have higher rates of HPV than areas with low incidence of esophageal carcinoma [40]. In our study, we observed an association between HPV infection and ESCC, HPV was detected in 27.6% of the cases by the use of in situ hybridization, and all cases were HPV-16 positive. The observation was consistent with the previous studies in high-risk areas for ESCC in China [29, 39, 41, 42].

In the present study, we also found that there were marginally significant differences between the HPV-positive and -negative ESCC (P = 0.07) with tumor location. HPV infection in upper esophagus was higher than lower. Potentially possible causes were the route of HPV infection and the histological similarities between the oropharyngeal squamous epithelia and upper digestive tract. HPV is currently one of the most common sexually transmitted infections worldwide [43]. Numerous studies have examined that changes in sexual behavior may be able to explain the increase in the incidence of HPV-positive cancers [44, 45]. Esophagus can be infected with these viruses in the same way as the oral cavity, tonsils, and pharynx.

In our study, 25 (86.2%) of the 29 HPV-positive ESCC cases expressed p16, while 14 (18.4%) of 76 HPV-negative subgroup. We observed strong agreement between tumor HPV status by in situ hybridization and p16 by immunohistochemistry, an established biomarker for the function of the HPV E7 oncoprotein. HPV in situ hybridization assay has sensitivity for single viral copies, and a positive result is strongly correlated with expression of the HPV E6 and E7 oncogenes which is the standard for defining a tumor as being effected with HPV [46, 47]. A restriction of our study is not to detect the other subtypes except HPV-16/18, the misclassification of HPV-positive tumors, as HPV-negative tumors probably emerge. The expression of p16 is not specific for HPV type; therefore, p16 immunohistochemistry is a very good surrogate marker of HPV infection for ESCC.

The prognostic value of HPV status has previously been investigated in patients with ESCC. However, the results were much controversial. Furihata et al. reported that HPV-positive patients had worse survival than HPV-negative patients with an overexpression of p53 in esophageal carcinoma patients; they concluded that HPV infection and p53 overexpression indicate poor prognosis [30]. Hippeläinen et al. reported that HPV were involved in 11% of 61 patients with ESCC but without prognostic value [29]. Dreilich et al. reported patients with a HPV-16 viral load > 1.0 viral genome per cell had higher survival rates compared to patients with a HPV-16 viral load < 1.0 viral genome per cell [31].

On the basis of our data, tumor HPV status was an independent prognostic factor for OS and PFS among patients with ESCC. Other retrospective researches have also consistently demonstrated that patients with HPV-positive tumors have a superior prognosis than patients with HPV-negative ones [23, 28, 48, 49]. Several hypotheses have been proposed to explain these results. Cisplatin sensitivity is increased in HPV-16 transfected ovarian cancer cells in vitro studies [50], which imply a better prognosis. HPV-DNA integration is confined to the neoplastic and dysplastic tissue only, so no effect is observed in the field cancerization in HPV-positive tumors [51, 52]. The relationship between the immune system, HPV status, and outcome remains an interesting area of ongoing research; a higher percentage of CD8 cells in the peripheral blood and a lower CD4/CD8 ratio and higher mean sum of CD4 and CD8 infiltrates in the tumor microenvironment may be predictive of better outcome [53]. Integration of HPV results in higher expression of the oncoproteins E6/E7, thereby abrogating the p53 and Rb protein functions, promoting genomic rearrangements [54]; rearranged DNA is theoretically more sensitive to radiation and chemotherapy, providing an explanation for the indication of higher survival rates for patients with HPV-positive tumors. Therefore, the biologic basis for the improved survival among the HPV-positive patients is unclear and warrants further study.

Smoking is associated with an increased risk of ESCC [55] and a poor outcome [22]. In the present study, patients with pack-years of smoking < 20 indicated a trend towards better survival than patients with pack-years of smoking ≥ 20, although this was not statistically significant (P = 0.06). However, patients with pack-years of smoking < 20 had a 49% reduction in their risk of progression compared with patients with pack-years of smoking ≥ 20 (P = 0.02). The link between HPV positivity in ESCC and smoking was still under investigation. Some studies have suggested synergistic effect [16, 56] while others have not [18, 57]. Genetic alterations induced by tobacco-associated carcinogens may be strengthened by HPV and cause HPV-positive tumors less sensitive to treatment. Our sample was too small to exclude confounding by smoking, although there was no apparent difference in the prevalence of smoking intake among patients with HPV-positive versus HPV-negative. Analysis of a larger study could more thoroughly evaluate the possibility of confounding by smoking via analysis of different levels of tobacco consumption.

Additional variables of potential prognostic importance, such as weight loss, anemia, performance status, dietary habits, and sexual behavior, were lacking in our study. Sample size limits the number of variables that could be included in our models. Factors not included in our models may be important and affect survival. Although statistically significant differences in survival were observed between HPV-positive and -negative, definitive conclusions cannot be drawn from this study due to its small sample size and retrospective nature; larger confirmatory studies are needed to provide definitive evidence.

In addition, the temporal sequence of HPV infection and onset of ESCC cannot be ascertained. Therefore, a causal relationship between exposure and outcome must be a tentative one, despite the association of infection and tumor which has been observed. A prospective study would be needed to further address this issue. The role of viruses has great potential in the clinical practice, particularly when investigated in combination with other factors. This study provides a direction for future clinical research. However, given the limited sample size, the results of this study should be interpreted with caution.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by China Postdoctoral Science Fund (no. 2011M500531) and Science and Technology development Planning of Shandong province (no. 2012GGE27088). The authors thank Dr. Junlong Xu (pathologist from the Department of Pathology, Liaocheng People's Hospital, Liaocheng, China) for his expert suggestions and technical assistance.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declared that there is no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this paper.

References

- 1.Ferlay J, Shin H-R, Bray F, Forman D, Mathers C, Parkin DM. Estimates of worldwide burden of cancer in 2008: GLOBOCAN 2008. International Journal of Cancer. 2010;127(12):2893–2917. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2011;61(2):69–90. doi: 10.3322/caac.20107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Collard J-M, Otte J-B, Fiasse R, et al. Skeletonizing en bloc esophagectomy for cancer. Annals of Surgery. 2001;234(1):25–32. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200107000-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Risk JM, Mills HS, Garde J, et al. The tylosis esophageal cancer (TOC) locus: more than just a familial cancer gene. Diseases of the Esophagus. 1999;12(3):173–176. doi: 10.1046/j.1442-2050.1999.00042.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wei W-Q, Yang J, Zhang S-W, Chen W-Q, Qiao Y-L. Analysis of the esophageal cancer mortality in 2004-2005 and its trends during last 30 years in China. Chinese journal of preventive medicine. 2010;44(5):398–402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gholipour C, Shalchi RA, Abbasi M. A histopathological study of esophageal cancer on the western side of the Caspian littoral from 1994 to 2003. Diseases of the Esophagus. 2008;21(4):322–327. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2007.00776.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Holmes RS, Vaughan TL. Epidemiology and pathogenesis of esophageal cancer. Seminars in Radiation Oncology. 2007;17(1):2–9. doi: 10.1016/j.semradonc.2006.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wei W-Q, Abnet CC, Qiao Y-L, et al. Prospective study of serum selenium concentrations and esophageal and gastric cardia cancer, heart disease, stroke, and total death. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2004;79(1):80–85. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/79.1.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Syrjänen KJ. HPV infections and oesophageal cancer. Journal of Clinical Pathology. 2002;55(10):721–728. doi: 10.1136/jcp.55.10.721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Syrjänen KJ. Histological changes identical to those of condylomatous lesions found in esophageal squamous cell carcinomas. Archiv fur Geschwulstforschung. 1982;52(4):283–292. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chang F, Syrjänen S, Shen Q, et al. Evaluation of HPV, CMV, HSV and EBV in esophageal squamous cell carcinomas from a high-incidence area of China. Anticancer Research. 2000;20(5 C):3935–3940. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Muñoz N, Bosch FX, de Sanjosé S, et al. Epidemiologic classification of human papillomavirus types associated with cervical cancer. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2003;348(6):518–527. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Walboomers JM, Jacobs MV, Manos MM, et al. Human papillomavirus is a necessary cause of invasive cervical cancer worldwide. The Journal of Pathology. 1999;189(1):12–19. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199909)189:1<12::AID-PATH431>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Naucler P, Chen H-C, Persson K, et al. Seroprevalence of human papillomaviruses and Chlamydia trachomatis and cervical cancer risk: nested case-control study. Journal of General Virology. 2007;88(3):814–822. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.82503-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meschede W, Zumbach K, Braspenning J, et al. Antibodies against early proteins of human papillomaviruses as diagnostic markers for invasive cervical cancer. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 1998;36(2):475–480. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.2.475-480.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Herrero R, Castellsagué X, Pawlita M, et al. Human papillomavirus and oral cancer: the international agency for research on cancer multicenter study. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2003;95(23):1772–1783. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djg107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zumbach K, Hoffmann M, Kahn T, et al. Antibodies against oncoproteins E6 and E7 of human papillomavirus types 16 and 18 in patients with head -and-neck squamous-cell carcinoma. International Journal of Cancer. 2000;85(6):815–818. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(20000315)85:6<815::aid-ijc14>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.D’Souza G, Kreimer AR, Viscidi R, et al. Case-control study of human papillomavirus and oropharyngeal cancer. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2007;356(19):1944–1956. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa065497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zur Hausen H. Papillomaviruses and cancer: from basic studies to clinical application. Nature Reviews Cancer. 2002;2(5):342–350. doi: 10.1038/nrc798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Münger K, Howley PM. Human papillomavirus immortalization and transformation functions. Virus Research. 2002;89(2):213–228. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1702(02)00190-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reimers N, Kasper HU, Weissenborn SJ, et al. Combined analysis of HPV-DNA, p16 and EGFR expression to predict prognosis in oropharyngeal cancer. International Journal of Cancer. 2007;120(8):1731–1738. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kumar B, Cordell KG, Lee JS, et al. EGFR, p16, HPV titer, Bcl-xL and p53, sex, and smoking as indicators of response to therapy and survival in oropharyngeal cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2008;26(19):3128–3137. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.7662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fakhry C, Westra WH, Li S, et al. Improved survival of patients with human papillomavirus-positive head and neck squamous cell carcinoma in a prospective clinical trial. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2008;100(4):261–269. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Licitra L, Perrone F, Bossi P, et al. High-risk human papillomavirus affects prognosis in patients with surgically treated oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2006;24(36):5630–5636. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.6136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smeets SJ, Hesselink AT, Speel E-JM, et al. A novel algorithm for reliable detection of human papillomavirus in paraffin embedded head and neck cancer specimen. International Journal of Cancer. 2007;121(11):2465–2472. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Syrjänen S. HPV infections and tonsillar carcinoma. Journal of Clinical Pathology. 2004;57(5):449–455. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2003.008656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kong CS, Narasimhan B, Cao H, et al. The relationship between human papillomavirus status and other molecular prognostic markers in head and neck squamous cell carcinomas. International Journal of Radiation Oncology Biology Physics. 2009;74(2):553–561. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weinberger PM, Yu Z, Haffty BG, et al. Molecular classification identifies a subset of human papillomavirus- associated oropharyngeal cancers with favorable prognosis. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2006;24(5):736–747. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.00.3335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hippeläinen M, Eskelinen M, Lipponen P, Chang F, Syrjänen K. Mitotic activity index, volume corrected mitotic index and human papilloma-virus suggestive morphology are not prognostic factors in carcinoma of the oesophagus. Anticancer Research. 1993;13(3):677–681. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Furihata M, Ohtsuki Y, Ogoshi S, Takahashi A, Tamiya T, Ogata T. Prognostic significance of human papillomavirus genomes (type-16, -18) and aberrant expression of p53 protein in human esophageal cancer. International Journal of Cancer. 1993;54(2):226–230. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910540211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dreilich M, Bergqvist M, Moberg M, et al. High-risk human papilloma virus (HPV) and survival in patients with esophageal carcinoma: a pilot study. BMC Cancer. 2006;6, article 94 doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-6-94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zheng S, Vuitton L, Sheyhidin I, Vuitton DA, Zhang Y, Lu X. Northwestern China: a place to learn more on oesophageal cancer. Part one: behavioural and environmental risk factors. European Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2010;22(8):917–925. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e3283313d8b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Saqi A, Pasha TL, McGrath CM, Yu GH, Zhang P, Gupta P. Overexpression of p16INK4A in liquid-based specimens (SurePath) as marker of cervical dysplasia and neoplasia. Diagnostic Cytopathology. 2002;27(6):365–370. doi: 10.1002/dc.10205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Michiels S, Le Maître A, Buyse M, et al. Surrogate endpoints for overall survival in locally advanced head and neck cancer: meta-analyses of individual patient data. The Lancet Oncology. 2009;10(4):341–350. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70023-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reed AL, Califano J, Cairns P, et al. High frequency of p16 (CDKN2/MTS-1/INK4A) inactivation in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Research. 1996;56(16):3630–3633. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.zur Hausen H. Papillomaviruses in the causation of human cancers—a brief historical account. Virology. 2009;384(2):260–265. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2008.11.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Muñoz N. Human papillomavirus and cancer: the epidemiological evidence. Journal of Clinical Virology. 2000;19(1-2):1–5. doi: 10.1016/s1386-6532(00)00125-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moberg M, Gustavsson I, Gyllensten U. Real-time pcr-based system for simultaneous quantification of human papillomavirus types associated with high risk of cervical cancer. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2003;41(7):3221–3228. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.7.3221-3228.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mork J, Lie AK, Glattre E, et al. Human papillomavirus infection as a risk factor for squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2001;344(15):1125–1131. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200104123441503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shen Z-Y, Hu S-P, Lu L-C, et al. Detection of human papillomavirus in esophageal carcinoma. Journal of Medical Virology. 2002;68(3):412–416. doi: 10.1002/jmv.10219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gao Y, Hu N, Han X, et al. Family history of cancer and risk for esophageal and gastric cancer in Shanxi, China. BMC Cancer. 2009;9, article 269 doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-9-269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wen D, Shan B, Wang S, et al. A positive family history of esophageal/gastric cardia cancer with gastric cardia adenocarcinoma is associated with a younger age at onset and more likely with another synchronous esophageal/gastric cardia cancer in a Chinese high-risk area. European Journal of Medical Genetics. 2010;53(5):250–255. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2010.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Baseman JG, Koutsky LA. The epidemiology of human papillomavirus infections. Journal of Clinical Virology. 2005;32:S16–S24. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2004.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Herbenick D, Reece M, Schick V, Sanders SA, Dodge B, Fortenberry JD. Sexual behavior in the United States: results from a national probability sample of men and women ages 14–94. Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2010;7(5):255–265. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.02012.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bajos N, Bozon M, Beltzer N, et al. Changes in sexual behaviours: from secular trends to public health policies. AIDS. 2010;24(8):1185–1191. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328336ad52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.de Vuyst H, Clifford GM, Nascimento MC, Madeleine MM, Franceschi S. Prevalence and type distribution of human papillomavirus in carcinoma and intraepithelial neoplasia of the vulva, vagina and anus: a meta-analysis. International Journal of Cancer. 2009;124(7):1626–1636. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Parkin DM, Bray F, Ferlay J, Pisani P. Global cancer statistics, 2002. CA Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2005;55(2):74–108. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.55.2.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gillison ML, Koch WM, Capone RB, et al. Evidence for a causal association between human papillomavirus and a subset of head and neck cancers. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2000;92(9):709–720. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.9.709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ang KK, Harris J, Wheeler R, et al. Human papillomavirus and survival of patients with oropharyngeal cancer. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2010;363(1):24–35. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0912217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pestell KE, Hobbs SM, Titley JC, Kelland LR, Walton MI. Effect of p53 status on sensitivity to platinum complexes in a human ovarian cancer cell line. Molecular Pharmacology. 2000;57(3):503–511. doi: 10.1124/mol.57.3.503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Begum S, Cao D, Gillison M, Zahurak M, Westra WH. Tissue distribution of human papillomavirus 16 DNA integration in patients with tonsillar carcinoma. Clinical Cancer Research. 2005;11(16):5694–5699. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.McGovern SL, Williams MD, Weber RS, et al. Three synchronous HPV-associated squamous cell carcinomas of Waldeyer’s ring: case report and comparison with Slaughter’s model of field cancerization. Head and Neck. 2010;32(8):1118–1124. doi: 10.1002/hed.21171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wansom D, Light E, Thomas D, et al. Infiltrating lymphocytes and human papillomavirus-16-associated oropharyngeal cancer. The Laryngoscope. 2012;122(1):121–127. doi: 10.1002/lary.22133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dahlgren L, Mellin H, Wangsa D, et al. Comparative genomic hybridization analysis of tonsillar cancer reveals a different pattern of genomic imbalances in human papillomavirus-positive and -negative tumors. International Journal of Cancer. 2003;107(2):244–249. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hecht SS. Cigarette smoking: cancer risks, carcinogens, and mechanisms. Langenbeck’s Archives of Surgery. 2006;391(6):603–613. doi: 10.1007/s00423-006-0111-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schwartz SM, Daling JR, Doody DR, et al. Oral cancer risk in relation to sexual history and evidence of human papillomavirus infection. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 1998;90(21):1626–1636. doi: 10.1093/jnci/90.21.1626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Applebaum KM, Furniss CS, Zeka A, et al. Lack of association of alcohol and tobacco with HPV16-associated head and neck cancer. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2007;99(23):1801–1810. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djm233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]