Abstract

Objective

Evaluate the effect of long-term β1-aderergic receptor blockade (β1-AR blockade) on LV remodeling and function in patients with chronic, isolated degenerative mitral regurgitation (MR).

Background

Isolated MR currently has no proven therapy that attenuates LV remodeling or preserves systolic function.

Methods

38 asymptomatic subjects with moderate to severe, isolated MR were randomized to either placebo or β1-AR blockade (Toprol-XL) for two years. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with tissue tagging and 3 dimensional (3D) analysis was performed at baseline and at six month intervals for two years. Rate of progression analysis was performed for end-point variables for primary outcomes: LV end-diastolic volume/body surface area (EDV/BSA), LV ejection fraction (EF), LVED mass/EDV ratio, LVED 3D radius/wall thickness (r/wt); LV end-systolic volume (ESV)/BSA, LV longitudinal strain rate, and LV early diastolic filling rate.

Results

Baseline LV MRI or demographic variables did not differ between the two groups. Significant treatment effects were found on LVEF (p=0.006) and LV early diastolic filling rate (p=0.001), which decreased over time in untreated patients on an intention to treat analysis, and remained significant following sensitivity analysis. There were no significant treatment effects found on LVED or LVES volumes, LVED mass/LVEDV or LVED 3D r/wt, or LV longitudinal strain rate. Over two years, six patients in placebo and two patients in β1-AR blockade group required mitral valve surgery (p = 0.23).

Conclusions

β1-AR blockade improves LV function over a two-year follow-up in isolated MR and provides the impetus for a large scale clinical trial with clinical outcomes.

Keywords: Mitral regurgitation, Beta Blockade, Medical therapy, Mitral valve disease

Introduction

Degenerative mitral valve disease, usually related to mitral valve prolapse, is responsible for the majority of isolated MR in the USA.1 There is no effective medical therapy for isolated MR and, therefore, surgery is recommended in patients with severe MR and symptoms or evidence of progressive LV dysfunction.2,3 The natural history of MR is progressive LV dysfunction and adverse LV remodeling eventually leading to heart failure. Initially there is LV dilation and augmented stroke volume facilitated by an increase in preload and by ejection into the relatively low pressure left atrium. These changes are accompanied by increased sympathetic drive early in MR in both animal models4,5 and humans.6 However, prolonged excessive adrenergic stimulation has a cytotoxic effect on cardiomyocytes,7 resulting in increased LV end-systolic dimension or volume and wall stress. In the canine model of isolated MR, chronic β1-adrenergic receptor (AR) blockade has been shown to improve cardiomyocyte and LV function.8,9 In patients with severe MR and normal LV ejection fraction (EF), β-AR blockade is associated with a survival benefit with or without coronary artery disease.10

In humans with moderate to severe degenerative MR, 14 day treatment with β1-AR blockade decreases LV work, but with increases in LV end-diastolic and end-systolic volumes and no change in LVEF.11 However, the beneficial effect of β1-AR blockade on LV function in heart failure is achieved after long-term therapy, and there has not been a human trial of extended β1-AR blockade on LV remodeling and function in patients with isolated MR. Therefore, the current randomized controlled study utilizes magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with tissue tagging and 3- dimensional (3-D) analysis as a surrogate outcome to evaluate effects of long-term β1- AR blockade on LV remodeling and function in patients with chronic, isolated MR.

Methods

Study Population

Eligible patients had moderate or severe MR documented by color flow Doppler, LVEF >55%, LV end systolic dimension (ESD) < 40 mm, and echocardiographic thickening of the mitral valve leaflets and prolapse. Patients were excluded with New York Heart Association class III or IV symptoms, previous myocardial infarction, significant coronary artery disease by exercise testing with myocardial perfusion imaging, significant other valvular disease, serum creatinine >2.5, and hypertension requiring medical treatment. The study was approved by the University of Alabama Institutional Review Board and all subjects gave written informed consent.

Study Protocol

We conducted a randomized, double blind study with two years of treatment of β1-AR blockade with Toprol XL (range 25 to 100 mg/day) vs placebo in patients with moderate to severe MR. Toprol XL, with a starting dose of 12.5 mg – 25 mg/day and titrated as tolerated at two week intervals to a maximum of 100 mg/day. Following randomization patients underwent MRI scanning, which was repeated at six, 12, 18, and 24 months after randomization. MRI was also performed in control volunteers (age 52 ± 11, range 35–70 years), who had no prior history of cardiovascular disease and were not taking any cardiovascular medications.

Cardiac MRI

As previously described,12,13 MRI was performed on a 1.5-T MRI scanner (Signa GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, Wisconsin) optimized for cardiac application. The short axis volumes defined by the contours, excluding papillary muscles, were summed to calculate LV volume.12,13 LV volume-time curves were constructed and differentiated with respect to time to obtain peak diastolic filling rates.13

Three-dimensional LV geometric parameters were measured from surfaces fit to endocardial and epicardial contours manually traced near end-diastole and end-systole. Three-dimensional wall thickness was computed by measuring the perpendicular distance from a point on the endocardial surface to the closest point on the epicardial surface.

Tagged magnetic resonance images were acquired with repetition/echo times 8/4.4 ms, and tag spacing 7mm. 3-D LV strain from tagged images at end-systole, which was defined by visual inspection of the image data as the time frame with maximum contraction.14 Two-dimensional (2-D) strain rates were measured using harmonic phase analysis,15 which measures local myocardial 2-D strain based on the local spatial frequency of tag lines. Strain and strain rates were computed at each segment in the American Heart Association 17-segment model and averaged over the mid-ventricular segments.

Statistical Analysis

Primary Outcome Variables

Analyses of MRIs were performed blinded side-by-side in one-sitting for each patient. MRI outcome variables were categorized according to the following:

LV Geometry: LV end-diastolic volume (EDV)/Body Surface Area (BSA), LVED Mass/LVEDV, 3-D LVED radius/wall thickness (midwall) (3-D LVED r/wt).

LV Systolic Function: LVEF, LV end-systolic volume (ESV)/BSA, 2-D LV systolic longitudinal strain rate.

LV Diastolic Function: LV peak early filling rate (EDV/s).

Analysis

T-test (for continuous variables) and Fisher’s exact test (for categorical variables) were used to compare demographic, clinical characteristics, and outcome variables at baseline between the two groups. Treatment differences in the rate of progression, assessed on an intention to treat basis, was the focus of the comparisons over time between the treatment groups. Rate of progression for each outcome was modeled with SAS PROC MIXED assuming the best working correlation structure based on the Bayesian Information Criterion from the choices of autoregressive lag 1 (AR(1)), heterogeneous autoregressive lag 1 (ARH(1)), compound symmetry and heterogeneous compound symmetry. Compound symmetry was found to be the best structure for all outcomes except for LVEDV/BSA where autoregressive lag 1 was found to be the best structure. A significant interaction effect between the linear component of time and treatment group is the measure of treatment effect, assessed at p <0.05.

MRIs were performed at a six-month interval over the two year study period. To achieve a more accurate representation of a patient’s rate of progression over time, the actual time of the MRI relative to randomization that is closest to a 3-month interval (i.e., 0, 3, 6, 9, 12, 15, etc.) is used in the analysis instead of the target 6- month visit. For example, if a patient was scheduled to have a 12-month MRI but actually had an MRI taken 2.5 months late from the target visit, the time associated with the MRI data for this visit was considered to be at 15 months instead of 12 months.

Results

Demographic Data (Table 1)

Table 1.

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of patients with isolated MR

| Variable Mean (SD) or count (% N) |

Placebo | Toprol | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Patients (N) | 19 | 19 | ||

| Sex (Female) | 9 (47%) | 11 (58%) | 0.7459 | |

| Race (Caucasian) | 19 (100%) | 16 (84%) | 0.2297 | |

| Age, years | 56(9.2) | 52.9* (9.1) | 0.3101 | |

| Systolic Blood Pressure, mm Hg | 121 (14) | 125 (14) | 0.3859 | |

| Diastolic Blood Pressure, mm Hg | 75 (11) | 75 (8) | 0.8905 | |

| Heart rate, beats/min | 67 (12) | 66 (11) | 0.8238 | |

| NYHA Functional class I | 17 (90%) | 18 (95%) | ~1 | |

| MRI variables | ||||

| LVEDV/BSA, ml/m2 | 92 (17) | 96 (20) | 0.4964 | |

| LVED Mass/LVEDV, gm/ml | 0.61 (0.13) | 0.61 (0.12) | 0.9720 | |

| LVED Radius/Wall Thickness | 4.76 (0.92) | 4.69 (0.92) | 0.8001 | |

| LVEF, % | 63 (5) | 62 (6) | 0.7820 | |

| LVESV/BSA, ml/m2 | 34 (7) | 36 (8) | 0.4258 | |

| Peak Systolic Longitudinal Strain Rate, %/sec | 88 (27) | 83 (29) | 0.5619 | |

| Peak Early Filling Rate, EDV/sec* | 2.27 (0.61) | 2.12 (0.57) | 0.4139 | |

LV end-diastolic volume/body surface area (LVEDV/BSA); LV ejection fraction (EF); LV end-systolic volume (LVESV);

= EDV/sec: peak early filling rate (ml/sec) normalized to EDV.

Thirty-eight patients were enrolled: 19 in Placebo and 19 in Toprol groups. One patient in Placebo group dropped out soon after the randomization, and one patient in Toprol group died due to pulmonary embolus after cosmetic surgery shortly after the month 12 visit. Thus, 36 patients had two years follow-up data. However, these patients were included in random effects models on intention-to-treat principle.

Baseline age, sex, race, heart rate, or blood pressure did not differ between groups. Of the 38 MR patients, 10 had holosysyolic murmurs with 5 in treated and 5 in untreated patients. No patients had a flail leaflet. No patients had atrial fibrillation and all patients were NYHA class I or II with 90 and 95% of placebo and treatment groups being in NYHA Class I, respectively.

At baseline, MR patients had 35% higher LVEDV/BSA, 50% higher LVESV/BSA, 33% higher LV stroke volume/BSA, and 18% lower LVED mass/EDV ratio, while LVEF was slightly lower in MR patients vs. control subjects (Supplemental Tables 1-4).

Analyses of Outcomes

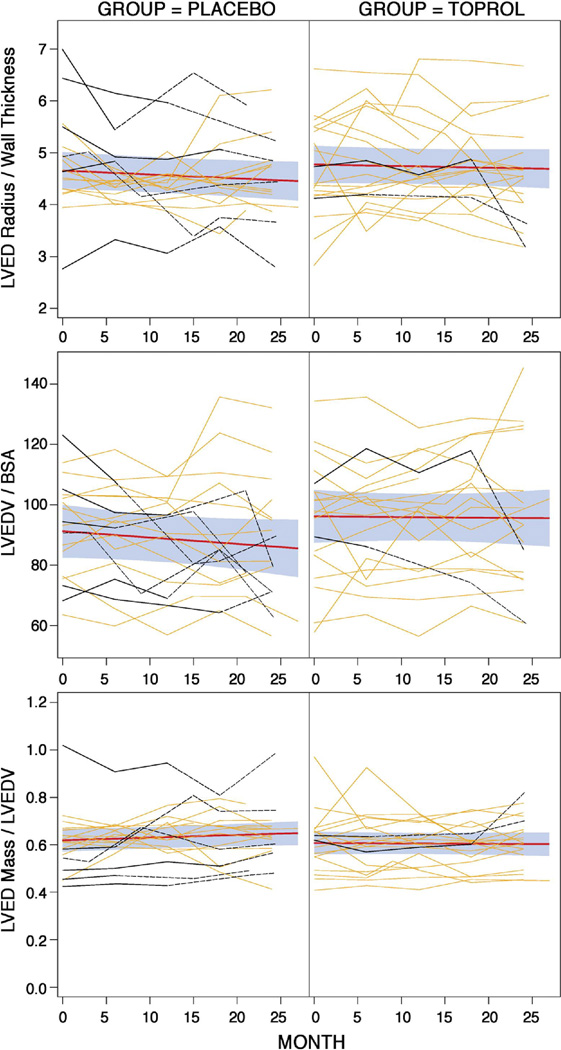

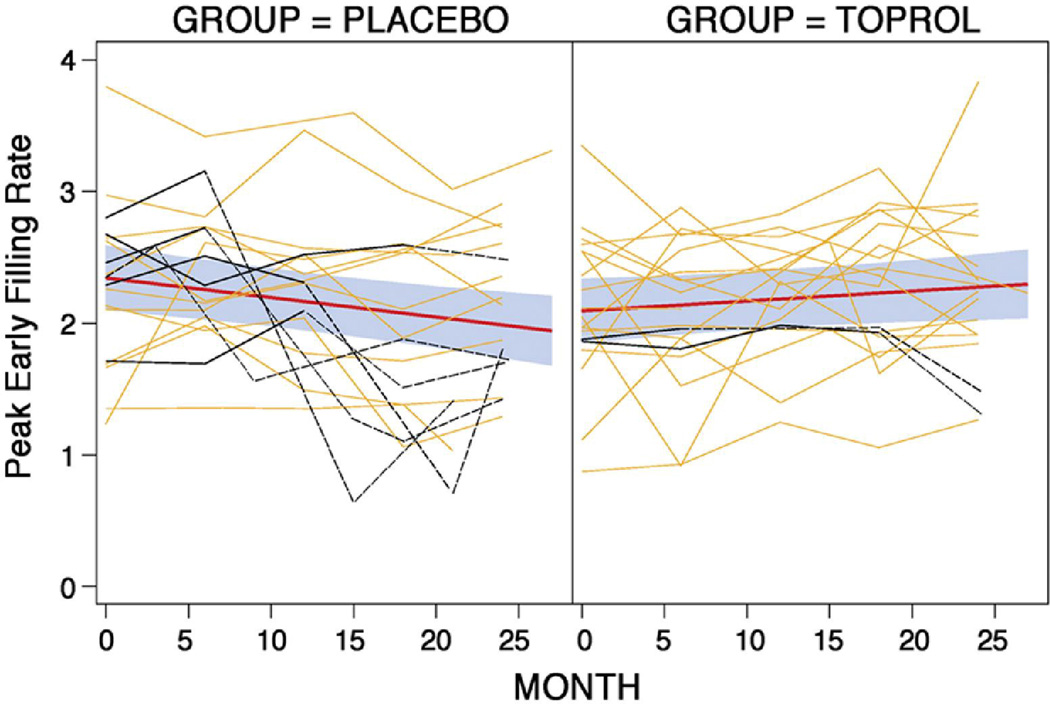

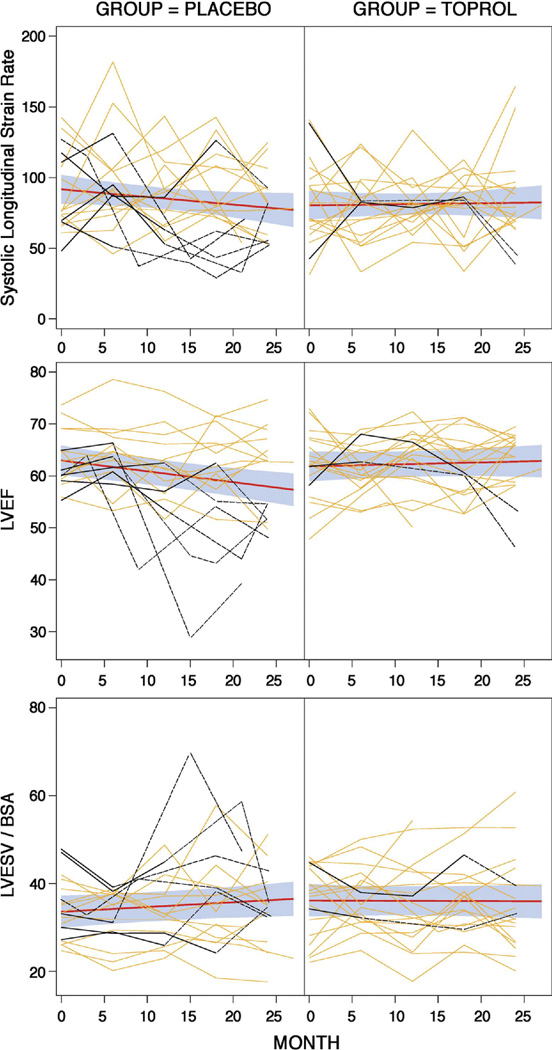

First-order and second-order polynomials for time effects were fitted for all outcome variables and coefficients associated with the second-order terms were not found to be significant; therefore, a first-order (linear) time effect model was used. Figures 1–3 display the raw data by treatment group for each LV outcome with the fitted lines as well as the fit with 95% confidence bands based on individual confidence intervals for the means at each time point. Table 2 displays the estimates and standard errors for the annual rates of progression (slope*12 months) for each group including the p-values which compare the estimates between the two groups.

Figure 1. Changes in LV end-diastolic volumes and geometry over two years.

Treatment efficacy is shown by the difference in rates of progression (slopes of the black lines shown with individual 95% confidence intervals, grey shaded areas, for the mean outcome at a given time point) between Placebo and Toprol groups. Individual patient data over time are shown for those with surgery (darker red) and without surgery (lighter red). There was no treatment effect for LVEDV/BSA, LVED mass/LVEDV ratio, or LVED 3-D radius/wall thickness.

Figure 3. Changes in LV diastolic function over two years (see Figure 1 for details).

There was a significant treatment effect for peak early filling rate.

Table 2.

Estimated annual rates of progression (increase if positive and decrease if negative) of each outcome for each treatment group. P-values are for comparing the estimates for the groups.

| Outcome Variable | Placebo Estimates (SE) |

Toprol Estimates (SE) |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| LVEDV/BSA, ml/m2 | −2.53 (2.19) | 0.25 (2.14) | 0.4568 |

| LVED Mass/LVEDV, gm/ml | 0.01 (0.01) | ~0.00 (0.01) | 0.1967 |

| LVED Radius/Wall Thickness | −0.09 (0.06) | −0.04 (0.06) | 0.5550 |

| LVEF, % | −2.48 (0.75) | 0.47 (0.75) | 0.0060 |

| LVESV/BSA, ml/m2 | 1.31 (0.81) | −0.11 (0.81) | 0.2144 |

| Peak Systolic Longitudinal Strain Rate, %/sec | −6.48 (3.70) | 0.96 (3.73) | 0.1587 |

| Peak Early Filling Rate, EDV/sec* | −0.18 (0.06) | 0.09 (0.06) | 0.0011 |

There were no significant treatment effects found on LVEDV/BSA (p=0.1195), LVED Mass/EDV (p=0.1967) and LVED 3-D radius/wt (p=0.55). Significant treatment effects were identified on LVEF (p=0.006), while no significant treatment effects were found on LVESV/BSA (p=0.46) and LV systolic longitudinal strain rate (p=0.16). The slope of LVEF per month for the Toprol group was estimated to be 0.04 (95% CI: −0.08, 0.16; not significantly different from 0), while the slope of the placebo group was estimated to be −0.21 (95% CI: −0.33, −0.08; significantly different from 0, p=0.001). This implies that the LVEF for the placebo group after two years is expected to decrease by as little as 1.92% and as high as 7.92%, on average, with 95% confidence. Significant treatment effects were detected for LV diastolic function measured by the peak early filling rate from the MRI volume time curves (p=0.001). The slope for the Toprol group was estimated to be 0.008 (95% CI: −0.002, 0.017) while the slope for the placebo group was estimated to be −0.015 (95% CI: −0.02, −0.005). In addition, there was a treatment effect for heart rate (p=0.006) and systolic blood pressure (SBP) (p=0.03) in placebo vs. Toprol treated MR patients (Supplementary Table 2).

Sensitivity Analysis

Sensitivity analyses were performed to account for possible effect in the statistical analyses of participants who had mitral valve surgery. These patients are identified (maroon curves) in Figures 1–3. Surgery is done because it is expected that the patient will get better. Therefore, it is logical to assume that the data observed after surgery of the patients who had mitral valve repair or replacement is better than what it would have been if they did not have surgery; hence, the data after surgery was replaced with the worst value for the visit within the treatment group. The conclusions were the same.

Adverse Events (AE)

While generally there was a pattern of a higher adverse event (AE) or serious adverse event (SAE) frequency in the placebo group, by design the study was not powered to detect modest differences between groups. Twelve of the 19 patients randomized to placebo and 8 of the 19 randomized to Toprol experienced at least one AE. Seven of the 12 in the Placebo and three of the eight in the Toprol group experienced SAEs. A formal test of the hypothesis using Fisher’s exact test did not show this difference to be statistically significant (p=0.33 for AE and p=0.27 for SAE). Six of the 19 patients in the Placebo group and only two of the 19 in the Toprol group had mitral valve repair or replacement. Fisher’s exact test also did not show this difference to be statistically significant (p=0.23).

Discussion

In this randomized placebo-controlled study, chronic β1-AR blockade prevents the progressive decline of LVEF, while LVEF slope decreases in the placebo group. At randomization, all patients are within standard echocardiographic guidelines with an LVES dimension < 40 mm and LVEF > 55% in the absence of symptoms. The beneficial effects of β1-AR blockade persist on an intention to treat and with a sensitivity analysis. There is no difference in the rate of progression for systolic wall stress calculated using blood pressure and 3D radius/wt at the base, mid, or distal LV (data not shown). Thus, the tendency for an increase in LVESV in the placebo group resulting in a decrease in the slope of LVEF may represent a decrease in contractility. In parallel with the effects on LV systolic function, early LV diastolic filling rate demonstrates a decreasing slope in placebo and an increasing slope in treated patients.

No treatment effects are detected for LV remodeling. The discordance between LV remodeling and improved LV systolic function with β1-AR has also been reported in the canine model of isolated MR.8,9 The dog model of isolated MR is marked by loss of extracellular matrix components essential to cardiac geometry,16,17 decrease in protein synthesis,18 and decrease in profibrotic growth factors including transforming growth factor-β.16 Thus, extracellular matrix loss combined with a less robust hypertrophy response produces LV wall thinning and a decrease in LVEDV mass/volume ratio16,17, as in our MR study patients (Supplementary Tables 1-4). These myocardial responses are a poor match for antifibrotic and antihypertrophic effects of renin-angiotensin system blockade, which explains why this therapy or vasodilators, do not attenuate LV remodeling in isolated MR.2,3 Although β1-AR blockade improves LV and cardiomyocyte function in the MR dog, interstitial loss is unchanged, which may explain the failure to attenuate LV dilatation.9

β1-AR blockade exhibits a trend toward preventing the need for operative intervention; however, the current study is not adequately powered to evaluate this outcome. Of interest, Figure 1 demonstrates baseline MRI-derived LVEFs less than 55% in three patients who receive β1-AR blockade. The discrepancy between echo-derived LV ESD and fractional shortening and MRI volume-based LVEF likely resides in the mid and apical spherical remodeling distal to standard echo-derived LVESD at the tips of the papillary muscles. Supplementary Figure 1 and Tables 1-4 demonstrate the greater amount of LV apical spherical remodeling, which contributes to increased LVES volume. Nevertheless, LVEF slope is positive in the treated group further supporting the beneficial effect of β1-AR blockade in isolated MR.

We do encourage caution that spurious findings that could arise from the multiple statistical tests conducted for the seven outcomes considered in this report. Because this was a pilot study, it was not clear at the inception what adjustments were appropriate to protect from the possibility of these spurious findings. However, even the most conservative approach, a Bonferroni adjustment with alpha of 0.0071 (0.05/7), was subsequently shown to not affect the interpretation of the findings, as all factors significant at 0.05 were also significant at this strict level. In addition, as noted in the Statistical Methods section, multiple correlation structures may be used to analyze the data. The choice of an appropriate structure was based on a priori and objective criteria of goodness-of-fit indices for the model using that particular working correlation and not based on treatment differences in the outcome measures. Thus, it is worth noting that using autoregressive structures considered or using actual times when MRI was taken resulted in no significant differences in any of the outcomes.

The current study uses cardiac remodeling as a surrogate outcome to assess the potential beneficial impact of β1-AR blockade in chronic isolated MR. While we are convinced that the surrogate outcome of LVEF will be strongly related with important clinical outcomes including prevention of heart failure and prolonging the need for surgical intervention, the current study does not definitively establish that clinical outcomes will improve, an association that can only be assessed in a Phase III randomized clinical. Nevertheless, this study using LV functional outcome, in addition to other reports of a survival benefit in patients with isolated MR,10 provides empiric support for the use of β1-AR blockade in patients with chronic degenerative MR. These findings call for a large multi-center clinical trial to confirm these effects.

Supplementary Material

Figure 2. Changes in LV systolic function over two years (see Figure 1 for details).

There was a significant treatment effect for LVEF but not for LVESV/BSA or LV peak systolic longitudinal strain rate.

Acknowledgements

Patient Recruitment in Birmingham, AL

Robert Foster MD: Birmingham Heart Clinic

Bradley Cavender MD and Steven Bakir MD: Cardiovascular Associates

Michael Parks MD: Southview Cardiovascular Associates

This study was funded by NHLBI Specialized Center for Clinically Oriented Research (SCCOR) in Cardiac Dysfunction P50HL077100.

Drug and Placebo were supplied by Astra-Zenica

Abbreviations

- (β1-AR blockade)

β1-aderergic receptor blockade

- (MRI)

Magnetic resonance imaging

- (3D)

3 dimensional

- (EDV/BSA)

LV end-diastolic volume/body surface area

- (EF)

LV ejection fraction

- LVED

mass/EDV ratio

- (r/wt)

LVED 3D radius/wall thickness

- (ESV)/BSA

LV end-systolic volume

- (AE)

adverse event

- (SAE)

serious adverse event

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Enriquez-Sarano M, Akins CW, Vahanian A. Mitral regurgitation. Lancet. 2009;373:1382–1394. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60692-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Borer JS, Bonow RO. Contemporary approach to aortic and mitral regurgitation. Circulation. 2003;108:2432–2438. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000096400.00562.A3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bonow RO, Carabello BA, Chatterjee K, et al. ACC/AHA 2006 guidelines for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48(3):e1–e148. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nagatsu M, Zile MR, Tsutsui H, et al. Native β-adrenergic support for left ventricular dysfunction in experimental mitral regurgitation normalizes indexes of pump and contractile function. Circulation. 1994;89:818–826. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.89.2.818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hankes GH, Ardell JL, Tallaj J, et al. Beta1-adrenoceptor blockade mitigates excessive norepinephrine release into cardiac interstitium in mitral regurgitation in dog. Am J Physiol. 2006;291(1):H147–H151. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00951.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mehta RH, Supiano MA, Oral H, et al. Compared with control subjects, the systemic sympathetic nervous system is activated in patients with mitral regurgitation. Am Heart J. 2003;145(6):1078–1085. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8703(03)00111-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mann DL, Kent RL, Parsons B, Cooper G. Adrenergic effects on the biology of the adult mammalian cardiocyte. Circulation. 1992;85:790–804. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.85.2.790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tsutsui H, Spinale FG, Nagatsu M, et al. Effects of chronic beta-adrenergic blockade on the left ventricular and cardiocyte abnormalities of chronic canine mitral regurgitation. J Clin Invest. 1994;93:2639–2648. doi: 10.1172/JCI117277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pat B, Killingsworth C, Denney T, et al. Dissociation between cardiomyocyte function and remodeling with β-adrenergic receptor blockade in isolated canine mitral regurgitation. Am J Physiol. 2008;295:H2321–H2327. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00746.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Varadarajan P, Joshi N, Appel D, Duvvuri L, Pai RG. Effect of beta-blocker therapy on survival in patients with severe mitral regurgitation and normal left ventricular ejection fraction. Am J Cardiol. 2008;102:611–615. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2008.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stewart RA, Raffel OC, Kerr AJ, Gabriel R, Zeng I, Young AA, Cowan BR. Pilot study to assess the influence of beta-blockade on mitral regurgitant volume and left ventricular work in degenerative mitral valve disease. Circulation. 2008;118(10):1041–1046. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.770438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ahmed M, Gladden JD, Litovsky S, et al. Myofibrillar degeneration, oxidative stress and post surgical systolic dysfunction in patients with isolated mitral regurgitation and pre-surgical LV ejection fraction > 60% J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:671–679. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.08.074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Feng W, Nagaraj H, Gupta H, et al. A dual propagation contours technique for semi-automated assessment of systolic and diastolic cardiac function by CMR. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2009;11:30. doi: 10.1186/1532-429X-11-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Denney TS, Gerber BL, Yan L. Unsupervised reconstruction of a three-dimensional left ventricular strain from parallel tagged cardiac images. Mag Reson Med. 2003;49:743–754. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Osman NF, Kerwin WS, McVeigh ER, Prince JL. Cardiac motion tracking using cine harmonic phase (HARP) magnetic resonance imaging. Magn Reson Med. 1999;42:1048–1060. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1522-2594(199912)42:6<1048::aid-mrm9>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zheng J, Chen Y, Pat B, et al. Microarray identifies extensive downregulation of noncollagen extracellular matrix and profibrotic growth factor genes in chronic isolated mitral regurgitation in the dog. Circulation. 2009;119:2086–2095. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.826230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dell'Italia LJ, Balcells E, Meng QC, et al. Volume overload cardiac hypertrophy is unaffected by ACE inhibitor treatment in the dog. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:H961–H970. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1997.273.2.H961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Matsuo T, Carabello BA, Nagatomo Y, et al. Mechanisms of cardiac hypertrophy in canine volume overload. Am J Physiol. 1998;275:H65–H74. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1998.275.1.h65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.