Abstract

Pregnane X receptor (PXR) is a member of the nuclear receptor (NR) superfamily of ligand-activated transcription factors and is activated by a huge variety of endobiotics and xenobiotics, including many clinical drugs. PXR plays key roles not only as a xenosensor in the regulation of both major phase I and II drug metabolism and transporters but also as a physiological sensor in the modulation of bile acid and cholesterol metabolism, glucose and lipid metabolism, and bone and endocrine homeostasis.

Post-translational modifications such as phosphorylation have been shown to modulate the activity of many NRs, including PXR, and constitute an important mechanism for crosstalk between signaling pathways and regulation of genes involved in both xenobiotic and endobiotic metabolism. In addition, microRNAs have recently been shown to constitute another level of PXR activity regulation.

The objective of this review is to comprehensively summarize current understanding of post-transcriptional and post-translational modifications of PXR in regulation of xenobiotic-metabolizing cytochrome P450 (CYP) genes, mainly in hepatic tissue. We also discuss the importance of PXR in crosstalk with cell signaling pathways, which at the level of transcription modify expression of genes associated with some physiological and pathological stages in the organs. Finally, we indicate that these PXR modifications may have important impacts on CYP-mediated biotransformation of some clinically used drugs.

Keywords: Cytochrome P450, gene regulation, induction, post-transcriptional, post-translational modification, pregnane X receptor, PXR

1. INTRODUCTION

Most of the detoxification mechanisms are under control of nuclear receptors (NRs) or ligand-activated transcription factors that trigger transcriptional upregulation of drug-metabolizing enzymes (DMEs). In 1994, aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR) and constitutive androstane receptor (CAR) were the first xenosensors discovered, although their roles as the molecular targets of the classic hepatic enzymes inductors has been discovered later on [1,2]. Four years later, mouse Pxr was discovered as an orphan nuclear receptor from a mouse liver cDNA library according to its sequence homology to ligand-binding domains of known nuclear receptors [3]. In parallel, the human ortholog of PXR was independently described by three research groups and termed the pregnane activated receptor (PAR), the pregnane X receptor (PXR), or the steroid and xenobiotic receptor (SXR) [4–6].

More recently, PXR receptor has been shown to be a critical factor in transactivation of most important DMEs and transporters. In addition, a growing body of evidence suggests its role in the regulation of endogenous metabolism.

2. PREGNANE X RECEPTOR

2.1. PXR – General Remarks

Pregnane X receptor (PXR, NR1I2) is a member of the nuclear receptors superfamily of ligand-dependent transcriptional factors, subfamily NR1I, and it has been identified as a xenobiotic/metabolite sensor regulating the expression of a wide variety of genes involved in transport, metabolism and elimination of xenobiotics and some endogenous substances [7–9].

It has been shown that PXR is predominantly expressed in the liver and intestine [3–6,10]. This expression pattern correlates with major cytochrome P450 (CYP) genes which encode important enzymes involved in the metabolism of xenobiotics. However, to a much lesser extent, PXR may also be found in such other tissues as kidney, stomach, brain, bone, lung, uterus, heart, adrenal glands, bone marrow, skeletal muscle, and testis [10–12].

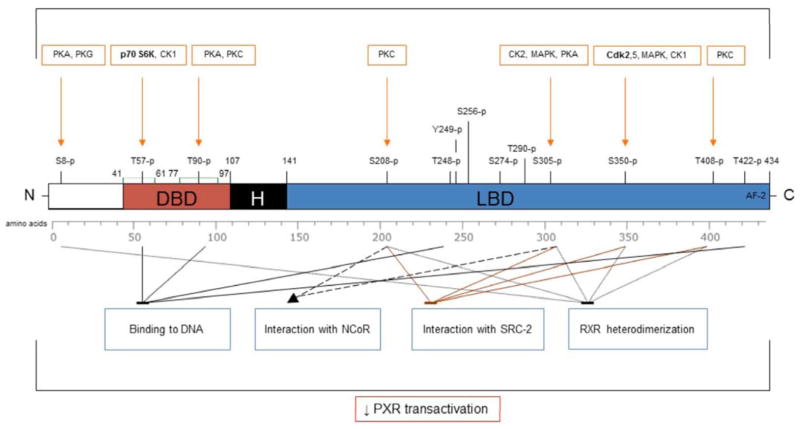

Like other typical nuclear receptors, PXR contains both a DNA-binding domain (DBD) at the N-terminus that facilitates binding to DNA responsive elements and a ligand-binding domain (LBD) at the C-terminus which is responsible for ligand binding and interaction with co-regulators [13] (Fig. 1). The crystal structure of human PXR-LBD is characterized by a ligand-binding cavity which is notably larger in volume compared with that of other NRs and is hydrophobic with only small number of polar residues. Thus, the character of the ligand-binding pocket reflects the structure of PXR ligands which are commonly hydrophobic with several polar groups [13–15].

Fig. 1.

The N-terminal region of human PXR includes DNA-binding domain (DBD) which is connected to ligand-binding domain (LBD) and activation function 2 (AF2) situated on the C-terminal region by the hinge region (H).

Evolutionarily conserved zinc-finger motifs are highlighted by green color; in silico predictive phosphorylation sites for protein kinases (orange squares) in the human PXR are indicated by orange arrows [45]. The protein kinases by which specific phosphorylation sites within human PXR were confirmed to be important for their effect on PXR-mediated transcriptional activity are in bold.

The effects of site-specific phosphorylation of human PXR such as DNA binding, RXR dimerization and co-regulator interaction are depicted (blue squares; arrow means activation; stop bar means suppression).

The mechanism underlying PXR transactivation of target genes involves ligand binding to PXR which in turn results in binding to a regulatory DNA sequence termed a response element within the promoter of a target gene. However, PXR requires heterodimerization with retinoid X receptor (RXR) for high-affinity DNA binding [13,16].

It has been reported that coactivators such as the steroid receptor coactivator-1 (SRC-1) [3,5], SRC-2, SRC-3 and the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-binding protein (PBP) associate with activated PXR and promote recruitment of transcription machinery at the promoters of the target genes by decompacting the chromatin structure [17]. This could occur through endogenous histone acetyltransferase (HAT) activity of coactivators or by facilitating recruitment of other regulators with HAT activity to activated PXR [17]. In contrast, the silencing mediator for retinoid and thyroid receptors (SMRT) binds to PXR in the absence of ligand and suppresses its transcriptional activity [18,19]. Similarly, small heterodimer partner (SHP), an atypical orphan nuclear receptor, has been shown to interact directly with PXR and repress its activity [20].

2.2. Pregnane X Receptor and Regulation of Xenobiotic and Endogenous Metabolism

CYP3A4 and several other CYP isoforms, such as CYP2B6 [21] and CYP2C isoforms [18,22], are induced through PXR activation in response to a myriad of natural and synthetic compounds [23,24]. In humans, CYP3A4 is the most important CYP enzyme involved in drug metabolism. There are two main reasons: (i) CYP3A4 is abundantly expressed in liver and intestine, which are major organs participating in xenobiotic metabolism; and (ii) it has broad substrate specificity responsible for biotransformation of more than 50% of all clinically used drugs [25–27]. In addition to regulating phase I DMEs, PXR also controls the expression of some phase II DMEs and transporters for xenobiotic detoxification and elimination [9]. These facts highlight a protective role of PXR against potentially toxic compounds jeopardizing the body. However, PXR also constitutes a molecular basis for potential drug–drug, herb–drug and food–drug interactions in cases when patients use combinations of chemicals. One PXR activator might, for instance, increase target CYP expression, which could then promote the clearance of other concurrently administered drugs and lead to therapeutic failure in patients. For that reason, drug interactions pose significant obstacles in developing new drug candidates and it is necessary to characterize these in early phases of preclinical development [8,23,28]. In addition to direct binding and activation of PXR, many xenobiotics alter multiple kinase pathways involved in post-translational modifications (PTMs) of PXR, thus resulting in alterations of PXR transcriptional activity and further contributing to drug–drug interactions [29].

In addition to its central role in regulation of xenobiotic metabolism, PXR also crosstalks with endogenous metabolism and inflammation [30–32]. It has been shown that PXR is also involved in modulation of hepatic glucose and lipid metabolism [7,33,34], bone homeostasis [35], endocrine homeostasis [36], and other processes [7,8,12,13,35].

3. POST-TRANSLATIONAL REGULATION OF PXR

While it is well known that the transcriptional activity of PXR is governed by direct binding of ligands, many reports have indicated that cellular signaling pathways modulate the functions of nuclear receptors, including PXR. These aspects shed some light on possible non-liganded mechanisms of receptor activation [37]. Herein, we comprehensively summarize recent evidence interfacing cell signaling pathways with PXR post-translational modification and its impact on CYPs regulation. Thus far, PXR has been shown to be a subject for phosphorylation, SUMOylation, ubiquitination and acetylation (Table 1; Fig. 1).

Table 1.

Summary of major PXR post-translational modifications and their effects on PXR-mediated transactivation of CYPs.

| PXR modification | Site1 | Enzyme | PXR-mediated mechanism | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| phosphorylation | ||||

| phosphorylation | unknown | PKC | ↓ transcription; ↑ interaction with NCoR; ↓ ligand-dependent interaction with SRC-1 | [38] |

| dephosphorylation | unknown | PP1/2A (inh.) | ↓ transcription | |

| phosphorylation | Cdk2 | ↓ transcription | [39] | |

| direct phosphorylation2 | unknown | Cdk2/cyclin A, E | ||

| phosphomimetic mutation | Ser350D | ↓ transcription | ||

| phosphorylation-deficient mutation | Ser350A | partial resistance to ↓ transcription by Cdk2 | ||

| unknown | unknown | Cdk2 (siRNA) | ↑ expression | [40] |

| unknown | unknown | Cdk4 (siRNA) | ↔ expression | |

| phosphorylation | unknown | Cdk5 | ↓ transcription | [41] |

| phosphorylation | unknown | Cdk5 (siRNA) | ↑ transcription | |

| direct phosphorylation2 | unknown | Cdk5/p35 | ||

| phosphorylation | unknown | p70 S6K | ↓ transcription | [42] |

| direct phosphorylation2 | unknown | p70 S6K | ||

| phosphomimetic mutation | Thr57D | ↓ transcription; × subcellular localization; ↔ SRC-1 interaction; ↓ DNA binding (ER6) | ||

| phosphorylation-deficient mutation | Thr57A | partial resistance to ↓ transcription by p70S6K; ↔ subcellular localization; ↔ SRC-1 interaction, ↔ DNA binding | ||

| phosphorylation | unknown | PKA | ↑ transcription3; ↑ interaction with SRC-1, PBP | [43] |

| direct phosphorylation2 | unknown | PKA | ||

| phosphorylation | unknown | PKA | ↓ transcription4; ↑ interaction with NCoR | [44] |

| phosphorylation | unknown | PKA | ↑ threonine phophorylation5 | |

| direct phosphorylation 2 | unknown | Cdk1, CK2, GSK3, PKA, PKC, p70 S6K | ||

| phosphomimetic mutations | Ser8D | ↓ transcription; ↔ DNA binding (ER6); ↓ RXRα heterodimerization; | [45] | |

| Ser208D | ↓ transcription; ↔ DNA binding; ↓ RXRα heterodimerization; interaction with NCoR ↑; SRC-2↓ | |||

| Ser305D | ↓ transcription; ↔ DNA binding; ↓ RXRα heterodimerization; interaction with NCoR ↑; SRC-2↓ | |||

| Ser350D | ↓ transcription; ↔ DNA binding; ↓ RXRα heterodimerization; interaction with NCoR↔; SRC-2↓ | |||

| Thr408D | ↓ transcription; ↔ DNA binding; ↓ RXRα heterodimerization; interaction with NCoR↔; SRC-2↓; × subcellular localization | |||

| Thr57D | ↓ transcription; ↓ DNA binding; ↔ RXRα heterodimerization | |||

| Thr90D | ↔ transcription; ↓ DNA binding; ↔ RXRα heterodimerization | |||

| phosphorylation-deficient mutations | Ser8A | ↔ transcription; ↔ DNA binding; ↔ RXRα heterodimerization | ||

| Ser208A | ↑ transcription; ↔ DNA binding; ↔ RXRα heterodimerization; interaction with NCoR↓; SRC-2↑ | |||

| Ser305A | ↔ transcription; ↔ DNA binding; ↔ RXRα heterodimerization; interaction with NCoR↑; SRC-2↑ | |||

| Ser350A | ↔ transcription; ↔ DNA binding; ↔ RXRα heterodimerization; interaction with NCoR↔; SRC-2↓ | |||

| Thr408A | ↓ transcription; ↔ DNA binding; ↔ RXRα heterodimerization; interaction with NCoR↑; SRC-2↓; × subcellular localization | |||

| Thr57A | ↔ transcription; ↔ DNA binding; ↔ RXRα heterodimerization | |||

| Thr90A | ↔ transcription; ↓ DNA binding; ↔ RXRα heterodimerization | |||

| mutations (including phosphorylation-deficient mutations) | Thr248G, A,V,L,S | ↓ transcription | [46] | |

| phosphorylation-deficient mutations | Thr248A,V | SRC-1 ↓ | ||

| phosphomimetic mutations | Thr248D | ↑ transcription; ↓ DNA binding (DR3); ↔ RXRα heterodimerization | [47] | |

| Tyr249D | ↓ transcription; ↔ DNA binding; ↔ RXRα heterodimerization | |||

| Thr422D | ↓ transcription; ↓ DNA binding; ↔ RXRα heterodimerization | |||

| phosphorylation-deficient mutations | Thr248V | ↓ transcription; ↓ DNA binding; ↔ RXRα heterodimerization | ||

| Tyr249F | ↔ transcription; ↔ DNA binding; ↔ RXRα heterodimerization | |||

| Thr422A | ↓ transcription; ↔ DNA binding; ↔ RXRα heterodimerization | |||

| SUMOylation | ||||

| SUMOylation-SUMO-1, SUMO-2, SUMO-3 (in vitro) | unknown | E1; E2 | [48] | |

| SUMOylation-preferentially SUMO-3 (in vivo) | unknown | E2 | ↔ transcription | |

| ubiquitination | ||||

| ubiquitination | unknown | RBCK1 | ↓ transcription | [49] |

| ubiquitination ↑ | unknown | PKA | [29] | |

| ubiquitination ↑6 | unknown | ↓ transcription | ||

| acetylation | ||||

| acetylation (in vivo) | unknown | unknown | [37] | |

| deacetylation (in vivo) | unknown | SIRT17 |

A, alanine; D, aspartic acid; F, phenylalanine; G, glycine; L, leucine; Ser, S, serine; Thr, threonine; Y, Tyr, tyrosine; V, valine

It is unclear whether amino acid residues within PXR which have been shown to be associated with phosphorylation-related functions are really phosphorylation sites for kinases;

by in vitro kinase assay;

mouse hepatocytes;

rat and human hepatocytes;

PXR exists as a phosphoprotein as detected by Western blot analysis;

using 26S proteasome inhibitor (MG132);

other HDAC(s) are assumed

↑: stimulation or strengthen; ↓: repression or weaken; ↔: no effect; ×: alteration

3.1. Phosphorylation of PXR

It is well established that many nuclear receptor superfamily members exist as phosphoproteins and that their phosphorylation is a dynamically changing process modulating their activities [50].

There is a growing body of evidence that site-specific phosphorylation of PXR provides an important mechanism for PXR-mediated regulation of CYP expression. It has been shown that series of kinases such as p70 S6K [42,45,51], PKA [43–45], PKC [38,45], Cdk2 [39,40,52] and Cdk5 [41] can phosphorylate and regulate PXR transcriptional activity. Along that same line, immunopurified human PXR also has been found to be a target for phosphorylation by such other kinases as glycogen synthase kinase 3 (GSK3), casein kinase II (CK2) and Cdk1 [44] (Fig. 1).

The effects of site-specific phosphorylation of PXR by kinases interfere with a wide variety of its functions involving subcellular localization, dimerization, DNA binding, and co-regulator interaction [38,43–45,47,51]. While phosphorylation generally may contribute to both activation or termination activity in NRs [50], direct phosphorylation in the case of human PXR leads mostly to negative response in its transcriptional activity [9].

3.1.1. PXR Phosphorylation and Inflammation

The activity of hepatic CYP genes is considerably suppressed during inflammation [53]. Recent data give rise to a hypothesis of there being bidirectional negative crosstalk between PXR and NF-κB, the known transcriptional regulator of immune and inflammatory responses, and thus making a connection between xenobiotic metabolism and inflammatory disease [30–32].

Importantly, the cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase A (PKA) is part of the glucagon mediated pathway and has been shown to have increased activity during acute inflammation [44,54]. There are inconsistent results regarding PKA signaling’s effect on the modulation of PXR transcriptional activity via phosphorylation. In mice, activation of the PKA signaling potentiated Pxr-mediated Cyp3a11 gene expression in mouse hepatocytes [43,44]). However, it has a repressive effect on PXR/Pxr transcriptional activity in both human and rat hepatocytes, which indicates PKA to work in a species-specific manner in regulating PXR/Pxr activity [44]. In addition, human PXR was shown to be a substrate for PKA, which was confirmed by in vitro kinase assay [43,44]. It was further discovered that PXR exists as a phosphoprotein in vivo and that the extent of threonine phosphorylation is enhanced by PKA signaling, which was confirmed by Western blot analysis using specific antibodies directed against phosphothreonine [44]. Finally, PKA signaling promotes interaction of mouse Pxr with coactivators such as SRC-1 and PBP [43] and NCoR with human PXR [44]. Taken together, these results demonstrate that PKA signaling probably modulates PXR activity through modulation of its phosphorylation status, but specific phosphorylation sites for PKA remain obscure [43–45].

It is worthy of note that the phenomenon of PXR activity repression in both cell-based reporter gene assays and in hepatocytes was also observed when protein kinase C (PKC)-dependent intra-cellular signaling pathway, which is also involved in inflammation, was activated [38]. The initiation of PKC signaling during inflammation is mediated upon cytokines stimulation of hepatocytes. In particular, IL-1, IL-6 and TNF-α activate PKC signaling in hepatocytes [55]. It has been well documented that release of proinflammatory cytokines downregulates CYP genes expression in liver [56–58]. The potential molecular basis for negative regulation of PXR transcription activity by PKC includes increasing the strength of interaction between PXR and corepressor NCoR while also disrupting ligand-dependent interaction between PXR and SRC-1. The role of alteration in the phosphorylation status in PXR or co-factors (NCoR and SRC-1) by PKC signaling remains to be evaluated. Interestingly, treatment of hepatocytes with okadaic acid (OA), the known inhibitor of protein phosphatase PP1/2A, diminishes ligand-dependent PXR activity, thus further suggesting a role of protein phosphorylation in regulating PXR activity [38].

Taken together, the available data shed light on the mechanism involved in repressing CYP genes associated with inflammation and presumed molecular links between signaling cascades and CYP expression in the liver.

3.1.2. PXR Phosphorylation and Cell Proliferation

Numerous studies have shown that CYPs are greatly reduced during liver development or regeneration [59]. It has been well established that downregulation of CYP isoenzymes’ activities occurs when hepatocytes are exposed to human growth factors such as HGF [60], which potently induces hepatocyte proliferation [61]. Similarly, findings linking EGF and TGFα with alteration of CYP expression in human hepatocytes have also been reported [62,63].

In recent work pioneered by Lin et al. [39], these authors speculate that the activity of PXR changes while cells pass through the various phases of the cell cycle. That study provided compelling evidence about a connection between attenuation of PXR activity during cell cycle progression with the activity of cyclin-dependent kinase 2 (Cdk2), which is one of the key regulators of the cell cycle [39]. The study showed that PXR-mediated activation of CYP3A4 luciferase gene reporter in transient transfection assays was decreased with activation of Cdk2 in HepG2 cells. Consistently, PXR transcriptional activity was substantially reduced in the S phase of the cell cycle, which is when Cdk2 activity increases. In addition, PXR protein was found to be a good substrate for Cdk2 in in vitro kinase assay. A putative Cdk2 phosphorylation site at Ser350 position was suggested, but this does not exclude that other phosphorylation sites for Cdk2 may exist within PXR. Furthermore, the phosphorylation-deficient mutation (S350A) rendered partial resistance to the suppressive effects of Cdk2 on activation of the CYP3A4 luciferase gene reporter. By contrast, phosphomimetic mutation (S350D) negatively altered PXR function [39].

Similarly, a study by Sugatani et al. [40] provides evidence that Cdk2 negatively regulates the expression of several genes related to xenobiotic metabolism. In contrast to Cdk4, silencing of Cdk2 by siRNA led to upregulation of CYP3A4 and CYP2B6 protein levels in HepG2 cells. Moreover, the treatment of HepG2 cells with HGF, which has been shown to be an anti-mitogenic factor for some tumor cell lines, led to negative regulation of Cdk2 activity. It is likely this occurred via increased expression of p16, p21 and p27, the known Cdk2/Cdk4 inhibitors [40,64], and upregulation of CYP2B6 expression [40]. Importantly, this effect is the inverse of the effect observed in human hepatocytes, where HGF is a strong mitogen and attenuates the expression and activity of CYP isoenzymes [60,61]. In addition, the dissociation between the expression of activated Cdk2 and the expression of CYP2B6 and CYP3A4 was apparent when cells were released into a synchronous cell cycle after S phase blocking by thymidine, which further links cell cycle progression with negative effect on CYP expression [40].

In a more recent work, the mechanism behind the increased CYP3A4 expression in confluent Huh7 cells compared to sub-confluent control cells was examined. The evidence indicates that Cdk2 plays an important role in decreasing PXR-mediated CYP3A4 expression. In proliferative cells, silencing of Cdk2 by siRNA resulted in increase of both CYP3A4 and PXR proteins. Additionally, the PXR mutant S350A induced CYP3A4 expression in HepG2 cells [65].

In parallel, it was observed that Cdk5 negatively regulates PXR activity [41]. In contrast to Cdk2, Cdk5 is not involved in cell-cycle progression but primarily participates in development of the central nervous system and maintaining neuronal survival. The expression of Cdk5 is not restricted only to neuronal tissue since it has also been detected in other non-neuronal cells [66]. Dong et al. [41] indicated that Cdk5 and its regulatory subunit p35 are expressed together in HepG2 cells. Otherwise, when Cdk5 was overexpressed in this cell line, there was significant repression of both basal and rifampicin-induced PXR activity in transient transfection CYP3A4 gene reporter assay. In the same line, the increase in PXR activity was detected after siRNA-mediated downregulation of Cdk5. In vitro kinase assay outlined direct phosphorylation of PXR by Cdk5 as a possible mechanism in attenuating PXR transcriptional activity [41].

The PI3K-Akt pathway transduces signals from cell-surface tyrosine kinase receptors (TKRs) after their stimulation by insulin and other growth factors to downstream kinases involved in regulating mRNA transcription and protein translation [54]. Recently, p70 S6K, a downstream kinase of the PI3K-Akt pathway was identified as a negative regulator of PXR transcriptional activity and was shown to directly phosphorylate PXR in vitro. Based on bioinformatics predictions, Thr57, a highly conserved phosphorylation site within DBD of human NRs as well as in PXR orthologues from various species, was found to be a putative phosphorylation site for p70 S6K. Site-directed mutagenesis provides a phosphomimetic mutant (T57D) of PXR, which leads to loss of PXR transcriptional activity in transient transfection CYP3A4 luciferase gene reporter in HepG2 cells probably due to disruption of PXR binding to the CYP3A4 gene promoter. Moreover, PXR mutant T57D exhibits a distinctive (punctate) nuclear distribution pattern and does not influence the interaction between PXR and transcriptional coactivator SRC-1. On the other hand, a phosphorylation-deficient mutation (T57A) of PXR renders partial resistance to p70 S6K-mediated negative regulation of PXR activity [42].

Mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) are serine/threonine kinases, which play an important role in transduction of extracellular signals from activated receptors on the cell surface to different cellular responses by interfering with various substrates such as transcriptional factors or downstream kinases. Importantly, MAPK signaling governs several cellular events, including growth, differentiation and survival. The best studied group of MAPKs consist of extracellular signal-regulated protein kinases (ERK1 and ERK2) [67]. Once activated, ERK may directly phosphorylate an array of NRs. Generally, this occurs at serine and threonine amino acid residues surrounded by proline and leading to either positive or negative regulation of NR transcriptional activity [68]. Based on in silico analysis of consensus phosphorylation sites for common protein kinases, Lichti-Kaiser et al. recently predicted human PXR to be a target for direct phosphorylation by a MAPK [45]. In our work, we have consistently observed that specific inhibition of mitogen-activated/extracellular signal-regulated kinase kinases 1/2 (MEK1/2), upstream kinases of ERK1/2, leads to activation of PXR transcriptional activity in gene reporter assay in HepG2 cells (our unpublished data). Thus, we provide indirect evidence for negative PXR regulation by MEKs. Taken together, we suppose that the MEK/ERK pathway negatively alters its transcriptional activity through direct PXR phosphorylation. Further studies, which will clarify the interplay between PXR and MEK/ERK signaling, are underway in our laboratory.

In an attempt to broaden our understanding of how phosphorylation regulates PXR activity, Lichti-Kaiser et al. [45] described comprehensively 18 potentially important serine and threonine amino acid residues within PXR which in silico prediction had suggested to be putative kinase phosphorylation sites. Six of the 18 potential phosphorylation sites within PXR were then selected for further characterization according to their ability to alter PXR transcriptional activity in gene reporter assay. This study showed that phosphorylation at Ser8, Thr57, Ser208, Ser305, Ser350 and Thr408 sites altered such various PXR functions as ability for DNA binding, RXRα heterodimerization, interaction with protein cofactors and PXR subcellular localization. Moreover, Thr90 was investigated due to its position within an evolutionarily highly conserved second zinc-finger motif of DBD-PXR. The effects of phosphomimetic and phosphorylation-deficient site mutants within PXR on distinct biological PXR roles are summarized in Table 1. It is unknown to date whether phosphorylation at these sites has any physiological significance, and subsequent studies should aim to prove the various effects of PXR modulation in vivo. The authors of the aforementioned work have reported some discrepancies among the data they have obtained. For instance, both phosphorylation-deficient and phosphomimetic mutations at Thr90 have lower binding ability to the CYP3A4 gene ER6 response element in comparison with wild-type PXR, although this does not substantially impact on PXR transcriptional activity in reporter gene assay [45]. Likewise, mutation at Ser350D disrupts RXRα heterodimerization with PXR but does not alter PXR’s binding to its response element together with RXRα. Only basal but not rifampicin-induced transactivation capacity of Ser350D mutant PXR was reported as repressed. These results differ from those observed by Lin et al. [39], wherein a phosphomimetic mutant at Ser350D decreased both basal and rifampicin-induced PXR activity in gene reporter assay. This could be due to the different model cell lines (CV-1 vs. HepG2 cells) used in the experiments [39,45].

In a follow-up study, Doricakova et al. [47] characterized the roles of other putative phosphorylation sites at T248, T422 [45] and Y249 of PXR. These sites were selected on the basis of in silico consensus kinase site prediction analysis. The effects on PXR biological functions using phosphomimetic and phosphorylation-deficient mutants of human PXR at the chosen amino acid residues are summarized in Table 1. These results suggest that residues T248 and T422 within PXR might be structural determinants for PXR function [47], which is in agreement with a report by Ueda et al. [46], who showed that hydrogen-bonding interaction of T248 with T422 in α-helix 12 is important for rifampicin-mediated activation of PXR. In addition, ligand-mediated recruitment of SRC-1 coactivator with AF2 domain of PXR was disrupted when phosphorylation-deficient mutants T248A or T248V were used in mammalian two-hybrid assay [46]. Notably, both phosphomimetic and phospho-deficient mutants at T422 abrogate PXR activity, thus indicating that phosphorylation at T422 is not likely a cause for loss of PXR function but that another mechanism should be presumed [47].

Recently, using mass spectrometry Elias et al. [69] identified S114, T133/135, S167, and S200 residues phosphorylated within PXR following an in vitro kinase assay using Cdk2 and phosphorylation at S114, T133, and T135 in vivo in the cells. Closer inspection showed that only dual phosphomimetic mutant T133D/T135D and phosphomimetic mutant S114D attenuate the transcriptional activity of PXR [69].

3.2. Ubiquitination of PXR

To date, the regulatory mechanisms involved in ubiquitination and degradation of PXR and their impacts on PXR-mediated CYP expression have been poorly investigated and require more experimental attention.

The degradation of proteins, including NRs, via proteasomes is targeted by conjugation of selected proteins with a polyubiquitin chain. This process is governed by a sequential pathway of three different enzymes (E1, E2 and E3) and results in covalent binding of ubiquitin to a selective substrate [70].

The first study searching for the connection between PXR and proteasome signaling has been carried out using a yeast two-hybrid protein interaction assay. It was shown that progesterone-occupied PXR interacts with suppressor for gal 1 (SUG1) [71], a known subunit of the 26S proteasome complex [72], but no interactions have been observed in the presence of the other PXR activators such as phthalic acid and nonylphenol. This finding highlights the fact that various PXR activators may alter PXR degradation differently, and it suggests another pathway in regulating PXR-mediated gene expression. The distinct interaction between PXR and SUG1 may be explained by conformational changes which occur within PXR upon binding of various agonists. Subsequently, the same group provided additional evidence supporting the hypothesis that PXR may be degraded by the proteasome. Notably, levels of PXR protein in nuclear fraction extracted from mouse mammary cancer (BALB-MC) cells were elevated when cells were treated with proteasome inhibitors. Consistent with that, overexpression of SUG1 in BALB-MC cells led to the appearance of proteolytic PXR fragments while the addition of proteasome inhibitor eliminated their generation, thus further suggesting an involvement of a proteasome. Moreover, the interaction between PXR and SUG1 depended on the presence of progesterone since proteolytic PXR derivatives did not appear in the absence of this steroid [74], which is in agreement with results of Masuyama et al [71]. Finally, overexpression of SUG1 suppressed progesterone- and PXR-mediated activation of CYP3A1 transcription in gene reporter assays [74].

Recently, Staudinger et al. [29] showed that the level of ubiquitinated PXR was elevated in response to MG132, the known inhibitor of 26S proteasome. Notably, PKA activation also led to increase in ubiquitinated PXR protein. It is worthy of note that inhibition of proteasomal degradation inhibited PXR-mediated transcriptional activity in the activation of the CYP3A4 luciferase gene reporter construct [29].

Also noteworthy is that the E3 ubiquitin ligase RBCK1 (Ring-B-box-coiled-coil protein interacting with protein kinase C-1) directly binds and ubiquitinates PXR, resulting in PXR’s degradation. The ectopic overexpression of RBCK1 in human hepatocytes leads to downregulation of rifampicin-mediated induction of PXR target genes (such as CYP2C9 and CYP3A4), presumably as a result of endogenous PXR protein degradation although other mechanisms involved or effects on PXR synthesis remain to be elucidated [49].

Taken together, the results provide evidence that some PXR ligands could prolong the lifespan of PXR, in part by disrupting the association between PXR and the proteasome component SUG1 [71,74]. In addition, it has been suggested that PXR is ubiquitinated directly, which may constitute a plausible way for regulating PXR transcriptional activity [29,49].

3.3. SUMOylation of PXR

Post-translational modification of proteins through conjugation with ubiquitin-like proteins – and mainly involving the small ubiquitin-related modifier (SUMO) family members – has been demonstrated to play important roles in modulating NR function. In humans, the SUMO family is comprised of three members known as SUMO-1, SUMO-2 and SUMO-3. SUMOylation, like ubiquitination, utilizes reversible conjugation and deconjugation pathways, but they differ in the array of enzymes which are involved in these processes. For the most part, SUMOylated NRs display repression of their transcriptional activity, which suggests another level of the NRs-mediated regulation of their target genes [73,75].

The SUMO pathway constitutes a conserved enzymatic cascade wherein SUMO conjugation to the target protein is initiated by E1 activating enzyme, which transfers the activated SUMO protein to the E2 conjugating enzyme (Ubc9). Finally, SUMOlation of lysine amino group residues within the substrate is completed by the E2, which usually requires another enzyme among those referred to as E3 ligases. Inverse to conjugation, the substrate may be SUMO deconjugated, which is accomplished by such SUMO isopeptidases as SENP [73,75].

As in the case of phosphorylation, SUMOlyation of PXR could be involved in regulating CYP expression during inflammation. Four potential sites for SUMOylation within PXR have been found by bioinformatic analysis. Consequently, PXR was shown to be a substrate for SUMOylation using an in vitro approach [48]. Furthermore, subsequent results have provided evidence that PXR probably is SUMOylated in vivo by SUMO-3 chains after stimulation of the hepatocytes by TNFα, which further leads to PXR-mediated repression of NF-κB target gene expression. On the other hand, SUMOlation of PXR has little effect on CYP3A gene expression. These findings indicate an interesting way as to how PXR modification could preferentially regulate the inflammatory response without significant targeting of CYP3A’s expression [48]. PXR is not a substrate for SUMO-1 (unpublished data, Mani Lab, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, NY).

3.4. Acetylation of PXR

A recent study has focused on the involvement of acetylation in regulating PXR function [29,37]. This has been confirmed by other laboratories [52]. Acetylation constitutes a common mechanism for post-translational modification of proteins, including NRs [76]. It has been demonstrated that PXR is acetylated in vivo and rifampicin-mediated activation of PXR leads to its deacetylation. In addition, the histone deacetylase SIRT1 was shown to be associated with PXR and partially involved in PXR deacetylation [77]. The given data also suggest that other deacetylases may participate in deacetylation of PXR. To date, however, it is unclear which lysine residues undergo acetylation and which HATs are responsible for PXR acetylation [37].

4. POST-TRANSCRIPTIONAL REGULATION OF PXR

MicroRNAs (miRNA) are short (about 22 nucleotides in length), noncoding RNA molecules. They are capable of regulating target genes by binding to complementary regions of transcripts, which results in repression of their translation or in mRNA degradation. Based on computational prediction, it is estimated that about 60% of all human mRNAs may be under the control of miRNA [78].

Recent data indicate the possibility of miRNA-mediated PXR post-transcriptional regulation. Takagi et al. [79] have noted that the level of PXR protein was not associated with PXR mRNA level in human liver samples from the Japanese population, thus pointing to the involvement of a post-transcriptional regulation. They have further evidenced that miR-148a recognizes the complementary sequence in the 3′-untranslated region of human PXR mRNA that leads to downregulation of PXR protein and, subsequently, of its target genes such as CYP3A4 [79].

On the other hand, in a follow-up study, Wei et al. [80] did not confirm the results of Takagi et al., as they found linear correlation between PXR mRNA and protein levels in human liver samples of Chinese donors. Moreover, no significant correlation of miR-148a with expression of PXR or CYP3A4 was detected [80]. Those authors concluded that ethnic differences between Japanese (N=25) [79] and Chinese Han (N=24) populations might play an important role and contribute to the inconsistent conclusions [80]. Similarly, an absence of correlation between miR-148 and either PXR or CYP3A4 mRNAs has been reported for Caucasian human liver donors (N=92) [81]. The results clearly demonstrate that PXR is not the only translational factors controlling basal expression of CYP3A4. Other nuclear receptors and transcription factors (such as CAR, HNF4α, C/EBPs etc.) are critical for CYP3A4 basal expression and its expression variability in human liver [26].

5. EXPERT OPINION

It is tempting to assume that mutually competitive modifications between SUMOylation and such other PTMs as acetylation and ubiquitination at lysine residues of PXR may occur [73]. However, further analysis is warranted to obtain more evidence as to the purposes of the individual PTMs in relation to PXR activity and their interplay in the context of PXR-mediated CYP expression.

Moreover, it has been noted that depending upon the target protein, phosphorylation may send either a positive or negative regulatory signal which directs the protein to SUMOlation [73]. It is not yet known whether phosphorylation of PXR may regulate its SUMOlation and, if so, how.

It is important to note that cell signaling pathways are mutually interconnected. For that reason, future research should be directed to obtaining a more comprehensive view that integrates multiple cell stimuli in the regulation of PXR-mediated activity. In addition, devoting more effort to the regulation of PXR activity through post-transcriptional and post-translational modifications would provide us new insight into drug metabolism by CYPs and the efficiency of drug therapy during the various physiological and pathological states.

The promiscuity among PXR and other NRs in binding to response element sites of target genes [27] further raises the question of how different post-transcriptional and post-translational modifications of individual NRs alter their role in CYPs’ regulation.

Moreover, it should be noted that co-regulators of NRs are also phosphorylation substrates that represent another level in the regulation of PXR-mediated activity [82].

Acknowledgments

The text has been supported by funds from the Czech Scientific Agency GACR303/12/G163 and GACR303/12/0472.

ABBREVIATIONS

- AF2

Activation function 2

- Akt

Protein kinase B

- CAR

Constitutive androstane receptor

- Cdk

Cyclin-dependent kinase

- CK2

Casein kinase II

- CYP

Cytochrome P450

- DBD

DNA binding domain

- DMEs

Drug-metabolizing enzymes

- EGF

Epidermal growth factor

- ERK1/2

Extracellular signal-regulated protein kinases 1/2

- gal1

Yeast galactokinase Gal1

- GSK3

Glycogen synthase kinase 3

- HAT

Histone acetyltransferase

- HDAC

Histone deacetylase

- HGF

Hepatocyte growth factor

- IL-1,6

Interleukin-1,6

- LBD

Ligand-binding domain

- MEK1/2

Mitogen-activated/extracellular signal-regulated kinase kinase 1/2

- miRNA

MicroRNA

- NCoR

Nuclear receptor corepressor

- NF-κB

Nuclear factor-kappa B

- NR

Nuclear receptor

- OA

Okadaic acid

- P70 S6K

70-kDa form of ribosomal protein S6 kinase

- PAR

Pregnane activated receptor

- PBP

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-binding protein

- PI3K

Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase

- PKA

Cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase

- PKC

Protein kinase C

- PP1/2A

Protein phosphatase 1/2A

- PTMs

Post-translational modifications

- PXR

Pregnane X receptor

- RBCK1

Ring-B-box-coiled-coil protein interacting with protein kinase C-1

- RXR

Retinoid X receptor

- SHP

Short/Small heterodimer partner (N0B2)

- siRNA

Small interfering RNA

- SIRT1

Sirtuin 1, Silent mating type information regulation 2 homolog 1

- SMRT

Nuclear receptor corepressor 2; silencing mediator for retinoid and thyroid hormone receptors

- SRC-1

Steroid receptor coactivator-1

- SUG1

Suppressor for gal 1

- SUMO

Small Ubiquitin-related Modifier

- SXR

Steroid and xenobiotic receptor

- TKR

Tyrosine kinase receptor

- TNFα

Tumor necrosis factor alpha

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors confirm that this article content has no conflicts of interest.

Send Orders for Reprints to reprints@benthamscience.net

We declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Ema M, Matsushita N, Sogawa K, Ariyama T, Inazawa J, Nemoto T, Ota M, Oshimura M, Fujii-Kuriyama Y. Human arylhydrocarbon receptor: Functional expression and chromosomal assignment to 7p21. J Biochem. 1994;116(4):845–851. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a124605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baes M, Gulick T, Choi HS, Martinoli MG, Simha D, Moore DD. A new orphan member of the nuclear hormone receptor superfamily that interacts with a subset of retinoic acid response elements. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14(3):1544–1552. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.3.1544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kliewer SA, Moore JT, Wade L, Staudinger JL, Watson MA, Jones SA, McKee DD, Oliver BB, Willson TM, Zetterstrom RH, Perlmann T, et al. An orphan nuclear receptor activated by pregnanes defines a novel steroid signaling pathway. Cell. 1998;92(1):73–82. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80900-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bertilsson G, Heidrich J, Svensson K, Asman M, Jendeberg L, Sydow-Backman M, Ohlsson R, Postlind H, Blomquist P, Berkenstam A. Identification of a human nuclear receptor defines a new signaling pathway for cyp3a induction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95(21):12208–12213. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.21.12208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lehmann JM, McKee DD, Watson MA, Willson TM, Moore JT, Kliewer SA. The human orphan nuclear receptor pxr is activated by compounds that regulate cyp3a4 gene expression and cause drug interactions. J Clin Invest. 1998;102(5):1016–1023. doi: 10.1172/JCI3703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blumberg B, Sabbagh W, Jr, Juguilon H, Bolado J, Jr, van Meter CM, Ong ES, Evans RM. Sxr, a novel steroid and xenobiotic-sensing nuclear receptor. Genes Dev. 1998;12(20):3195–3205. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.20.3195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wada T, Gao J, Xie W. Pxr and car in energy metabolism. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2009;20(6):273–279. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2009.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ma X, Idle JR, Gonzalez FJ. The pregnane x receptor: From bench to bedside. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2008;4(7):895–908. doi: 10.1517/17425255.4.7.895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang YM, Ong SS, Chai SC, Chen T. Role of car and pxr in xeno-biotic sensing and metabolism. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2012;8(7):803–817. doi: 10.1517/17425255.2012.685237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nishimura M, Naito S, Yokoi T. Tissue-specific mrna expression profiles of human nuclear receptor subfamilies. Drug Metab Pharmacokinet. 2004;19(2):135–149. doi: 10.2133/dmpk.19.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pavek P, Dvorak Z. Xenobiotic-induced transcriptional regulation of xenobiotic metabolizing enzymes of the cytochrome p450 superfamily in human extrahepatic tissues. Curr Drug Metab. 2008;9(2):129–143. doi: 10.2174/138920008783571774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhou C, Verma S, Blumberg B. The steroid and xenobiotic receptor (sxr), beyond xenobiotic metabolism. Nucl Recept Signal. 2009;7:e001. doi: 10.1621/nrs.07001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.di Masi A, De Marinis E, Ascenzi P, Marino M. Nuclear receptors car and pxr: Molecular, functional, and biomedical aspects. Mol Aspects Med. 2009;30(5):297–343. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2009.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Watkins RE, Wisely GB, Moore LB, Collins JL, Lambert MH, Williams SP, Willson TM, Kliewer SA, Redinbo MR. The human nuclear xenobiotic receptor pxr: Structural determinants of directed promiscuity. Science. 2001;292(5525):2329–2333. doi: 10.1126/science.1060762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ekins S, Chang C, Mani S, Krasowski MD, Reschly EJ, Iyer M, Kholodovych V, Ai N, Welsh WJ, Sinz M, Swaan PW, et al. Human pregnane x receptor antagonists and agonists define molecular requirements for different binding sites. Mol Pharmacol. 2007;72(3):592–603. doi: 10.1124/mol.107.038398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cai Y, Konishi T, Han G, Campwala KH, French SW, Wan YJ. The role of hepatocyte rxr alpha in xenobiotic-sensing nuclear receptor-mediated pathways. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2002;15(1):89–96. doi: 10.1016/s0928-0987(01)00211-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rosenfeld MG, Lunyak VV, Glass CK. Sensors and signals: A coactivator/corepressor/epigenetic code for integrating signal-dependent programs of transcriptional response. Genes Dev. 2006;20(11):1405–1428. doi: 10.1101/gad.1424806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Synold TW, Dussault I, Forman BM. The orphan nuclear receptor sxr coordinately regulates drug metabolism and efflux. Nat Med. 2001;7(5):584–590. doi: 10.1038/87912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Takeshita A, Taguchi M, Koibuchi N, Ozawa Y. Putative role of the orphan nuclear receptor sxr (steroid and xenobiotic receptor) in the mechanism of cyp3a4 inhibition by xenobiotics. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(36):32453–32458. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111245200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ourlin JC, Lasserre F, Pineau T, Fabre JM, Sa-Cunha A, Maurel P, Vilarem MJ, Pascussi JM. The small heterodimer partner interacts with the pregnane x receptor and represses its transcriptional activity. Mol Endocrinol. 2003;17(9):1693–1703. doi: 10.1210/me.2002-0383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goodwin B, Moore LB, Stoltz CM, McKee DD, Kliewer SA. Regulation of the human cyp2b6 gene by the nuclear pregnane x receptor. Mol Pharmacol. 2001;60(3):427–431. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gerbal-Chaloin S, Pascussi JM, Pichard-Garcia L, Daujat M, Waechter F, Fabre JM, Carrere N, Maurel P. Induction of cyp2c genes in human hepatocytes in primary culture. Drug Metab Dispos. 2001;29(3):242–251. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Staudinger JL, Ding X, Lichti K. Pregnane x receptor and natural products: Beyond drug-drug interactions. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2006;2(6):847–857. doi: 10.1517/17425255.2.6.847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sinz M, Kim S, Zhu Z, Chen T, Anthony M, Dickinson K, Rodrigues AD. Evaluation of 170 xenobiotics as transactivators of human pregnane x receptor (hpxr) and correlation to known cyp3a4 drug interactions. Curr Drug Metab. 2006;7(4):375–388. doi: 10.2174/138920006776873535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li AP, Kaminski DL, Rasmussen A. Substrates of human hepatic cytochrome p450 3a4. Toxicology. 1995;104(1–3):1–8. doi: 10.1016/0300-483x(95)03155-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Martinez-Jimenez CP, Jover R, Donato MT, Castell JV, Gomez-Lechon MJ. Transcriptional regulation and expression of cyp3a4 in hepatocytes. Curr Drug Metab. 2007;8(2):185–194. doi: 10.2174/138920007779815986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Plant N. Use of reporter genes to measure xenobiotic-mediated activation of cyp gene transcription. Methods Mol Biol. 2006;320:343–354. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-998-2:343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lin JH. Cyp induction-mediated drug interactions: In vitro assessment and clinical implications. Pharm Res. 2006;23(6):1089–1116. doi: 10.1007/s11095-006-0277-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Staudinger JL, Xu C, Biswas A, Mani S. Post-translational modification of pregnane x receptor. Pharmacol Res. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2011.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gu X, Ke S, Liu D, Sheng T, Thomas PE, Rabson AB, Gallo MA, Xie W, Tian Y. Role of nf-kappab in regulation of pxr-mediated gene expression: A mechanism for the suppression of cytochrome p-450 3a4 by proinflammatory agents. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(26):17882–17889. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601302200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhou C, Tabb MM, Nelson EL, Grun F, Verma S, Sadatrafiei A, Lin M, Mallick S, Forman BM, Thummel KE, Blumberg B. Mutual repression between steroid and xenobiotic receptor and nf-kappab signaling pathways links xenobiotic metabolism and inflammation. J Clin Invest. 2006;116(8):2280–2289. doi: 10.1172/JCI26283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shah YM, Ma X, Morimura K, Kim I, Gonzalez FJ. Pregnane x receptor activation ameliorates dss-induced inflammatory bowel disease via inhibition of nf-kappab target gene expression. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2007;292(4):G1114–1122. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00528.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kodama S, Koike C, Negishi M, Yamamoto Y. Nuclear receptors car and pxr cross talk with foxo1 to regulate genes that encode drug-metabolizing and gluconeogenic enzymes. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24(18):7931–7940. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.18.7931-7940.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bhalla S, Ozalp C, Fang S, Xiang L, Kemper JK. Ligand-activated pregnane x receptor interferes with hnf-4 signaling by targeting a common coactivator pgc-1alpha. Functional implications in hepatic cholesterol and glucose metabolism. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(43):45139–45147. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M405423200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Igarashi M, Yogiashi Y, Mihara M, Takada I, Kitagawa H, Kato S. Vitamin k induces osteoblast differentiation through pregnane x receptor-mediated transcriptional control of the msx2 gene. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27(22):7947–7954. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00813-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 36.Zhai Y, Pai HV, Zhou J, Amico JA, Vollmer RR, Xie W. Activation of pregnane x receptor disrupts glucocorticoid and mineralo-corticoid homeostasis. Mol Endocrinol. 2007;21(1):138–147. doi: 10.1210/me.2006-0291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Biswas A, Pasquel D, Tyagi RK, Mani S. Acetylation of pregnane x receptor protein determines selective function independent of ligand activation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2011;406(3):371–376. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.02.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ding X, Staudinger JL. Repression of pxr-mediated induction of hepatic cyp3a gene expression by protein kinase c. Biochem Pharmacol. 2005;69(5):867–873. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2004.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lin W, Wu J, Dong H, Bouck D, Zeng FY, Chen T. Cyclin-dependent kinase 2 negatively regulates human pregnane x receptor-mediated cyp3a4 gene expression in hepg2 liver carcinoma cells. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(45):30650–30657. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M806132200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sugatani J, Osabe M, Kurosawa M, Kitamura N, Ikari A, Miwa M. Induction of ugt1a1 and cyp2b6 by an antimitogenic factor in hepg2 cells is mediated through suppression of cyclin-dependent kinase 2 activity: Cell cycle-dependent expression. Drug Metab Dispos. 2010;38(1):177–186. doi: 10.1124/dmd.109.029785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dong H, Lin W, Wu J, Chen T. Flavonoids activate pregnane x receptor-mediated cyp3a4 gene expression by inhibiting cyclin-dependent kinases in hepg2 liver carcinoma cells. BMC Biochem. 2010;11(23) doi: 10.1186/1471-2091-11-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pondugula SR, Brimer-Cline C, Wu J, Schuetz EG, Tyagi RK, Chen T. A phosphomimetic mutation at threonine-57 abolishes transactivation activity and alters nuclear localization pattern of human pregnane x receptor. Drug Metab Dispos. 2009;37(4):719–730. doi: 10.1124/dmd.108.024695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ding X, Staudinger JL. Induction of drug metabolism by forskolin: The role of the pregnane x receptor and the protein kinase a signal transduction pathway. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;312(2):849–856. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.076331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lichti-Kaiser K, Xu C, Staudinger JL. Cyclic amp-dependent protein kinase signaling modulates pregnane x receptor activity in a species-specific manner. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(11):6639–6649. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M807426200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lichti-Kaiser K, Brobst D, Xu C, Staudinger JL. A systematic analysis of predicted phosphorylation sites within the human pregnane x receptor protein. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2009;331(1):65–76. doi: 10.1124/jpet.109.157180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ueda A, Matsui K, Yamamoto Y, Pedersen LC, Sueyoshi T, Negishi M. Thr176 regulates the activity of the mouse nuclear receptor car and is conserved in the nr1i subfamily members pxr and vdr. Biochem J. 2005;388(Pt 2):623–630. doi: 10.1042/BJ20041572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Doricakova A, Novotna A, Vrzal R, Pavek P, Dvorak Z. The role of residues t248, y249 and t422 in the function of human pregnane x receptor. Arch Toxicol. 2013;87(2):291–301. doi: 10.1007/s00204-012-0937-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hu G, Xu C, Staudinger JL. Pregnane x receptor is sumoylated to repress the inflammatory response. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2010;335(2):342–350. doi: 10.1124/jpet.110.171744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rana R, Coulter S, Kinyamu H, Goldstein JA. Rbck1, an e3 ubiquitin ligase, interacts with and ubiquinates the human pregnane x receptor. Drug Metab Dispos. 2012;41(2):398–405. doi: 10.1124/dmd.112.048728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rochette-Egly C. Nuclear receptors: Integration of multiple signalling pathways through phosphorylation. Cell Signal. 2003;15(4):355–366. doi: 10.1016/s0898-6568(02)00115-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pondugula SR, Dong H, Chen T. Phosphorylation and protein-protein interactions in pxr-mediated cyp3a repression. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2009;5(8):861–873. doi: 10.1517/17425250903012360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sugatani J, Uchida T, Kurosawa M, Yamaguchi M, Yamazaki Y, Ikari A, Miwa M. Regulation of pregnane x receptor (pxr) function and ugt1a1 gene expression by posttranslational modification of pxr protein. Drug Metab Dispos. 2012;40(10):2031–2040. doi: 10.1124/dmd.112.046748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Morgan ET, Goralski KB, Piquette-Miller M, Renton KW, Robertson GR, Chaluvadi MR, Charles KA, Clarke SJ, Kacevska M, Liddle C, Richardson TA, et al. Regulation of drug-metabolizing enzymes and transporters in infection, inflammation, and cancer. Drug Metab Dispos. 2008;36(2):205–216. doi: 10.1124/dmd.107.018747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kim SK, Novak RF. The role of intracellular signaling in insulin-mediated regulation of drug metabolizing enzyme gene and protein expression. Pharmacol Ther. 2007;113(1):88–120. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2006.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sayeed MM. Alterations in cell signaling and related effector functions in t lymphocytes in burn/trauma/septic injuries. Shock. 1996;5(3):157–166. doi: 10.1097/00024382-199603000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Abdel-Razzak Z, Loyer P, Fautrel A, Gautier JC, Corcos L, Turlin B, Beaune P, Guillouzo A. Cytokines down-regulate expression of major cytochrome p-450 enzymes in adult human hepatocytes in primary culture. Mol Pharmacol. 1993;44(4):707–715. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Muntane-Relat J, Ourlin JC, Domergue J, Maurel P. Differential effects of cytokines on the inducible expression of cyp1a1, cyp1a2, and cyp3a4 in human hepatocytes in primary culture. Hepatology. 1995;22(4 Pt 1):1143–1153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jover R, Bort R, Gomez-Lechon MJ, Castell JV. Down-regulation of human cyp3a4 by the inflammatory signal interleukin-6: Molecular mechanism and transcription factors involved. Faseb J. 2002;16(13):1799–1801. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0195fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hines RN. Ontogeny of human hepatic cytochromes p450. J Biochem Mol Toxicol. 2007;21(4):169–175. doi: 10.1002/jbt.20179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Donato MT, Gomez-Lechon MJ, Jover R, Nakamura T, Castell JV. Human hepatocyte growth factor down-regulates the expression of cytochrome p450 isozymes in human hepatocytes in primary culture. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1998;284(2):760–767. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gomez-Lechon MJ, Castelli J, Guillen I, O’Connor E, Nakamura T, Fabra R, Trullenque R. Effects of hepatocyte growth factor on the growth and metabolism of human hepatocytes in primary culture. Hepatology. 1995;21(5):1248–1254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Greuet J, Pichard L, Ourlin JC, Bonfils C, Domergue J, Le Treut P, Maurel P. Effect of cell density and epidermal growth factor on the inducible expression of cyp3a and cyp1a genes in human hepatocytes in primary culture. Hepatology. 1997;25(5):1166–1175. doi: 10.1002/hep.510250520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Braeuning A. Regulation of cytochrome p450 expression by ras- and beta-catenin-dependent signaling. Curr Drug Metab. 2009;10(2):138–158. doi: 10.2174/138920009787522160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Shima N, Stolz DB, Miyazaki M, Gohda E, Higashio K, Michalopoulos GK. Possible involvement of p21/waf1 in the growth inhibition of hepg2 cells induced by hepatocyte growth factor. J Cell Physiol. 1998;177(1):130–136. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(199810)177:1<130::AID-JCP14>3.0.CO;2-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sivertsson L, Edebert I, Palmertz MP, Ingelman-Sundberg M, Neve EP. Induced cyp3a4 expression in confluent huh7 hepatoma cells as a result of decreased cell proliferation and subsequent pregnane x receptor activation. Mol Pharmacol. 2013;83(3):659–670. doi: 10.1124/mol.112.082305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zhu J, Li W, Mao Z. Cdk5: Mediator of neuronal development, death and the response to DNA damage. Mech Ageing Dev. 2011;132(8–9):389–394. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2011.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Min L, He B, Hui L. Mitogen-activated protein kinases in hepatocellular carcinoma development. Semin Cancer Biol. 2010;21(1):10–20. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2010.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zassadowski F, Rochette-Egly C, Chomienne C, Cassinat B. Regulation of the transcriptional activity of nuclear receptors by the mek/erk1/2 pathway. Cell Signal. 2012;24(12):2369–2377. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2012.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Elias A, High AA, Mishra A, Ong SS, Wu J, Peng J, Chen T. Identification and characterization of phosphorylation sites within the pregnane x receptor protein. Biochem Pharmacol. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2013.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Portbury AL, Ronnebaum SM, Zungu M, Patterson C, Willis MS. Back to your heart: Ubiquitin proteasome system-regulated signal transduction. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2012;52(3):526–537. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2011.10.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Masuyama H, Hiramatsu Y, Kunitomi M, Kudo T, MacDonald PN. Endocrine disrupting chemicals, phthalic acid and nonylphenol, activate pregnane x receptor-mediated transcription. Mol Endocrinol. 2000;14(3):421–428. doi: 10.1210/mend.14.3.0424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Rubin DM, Coux O, Wefes I, Hengartner C, Young RA, Goldberg AL, Finley D. Identification of the gal4 suppressor sug1 as a subunit of the yeast 26s proteasome. Nature. 1996;379(6566):655–657. doi: 10.1038/379655a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bossis G, Melchior F. Sumo: Regulating the regulator. Cell Div. 2006;1(13) doi: 10.1186/1747-1028-1-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Masuyama H, Inoshita H, Hiramatsu Y, Kudo T. Ligands have various potential effects on the degradation of pregnane x receptor by proteasome. Endocrinology. 2002;143(1):55–61. doi: 10.1210/endo.143.1.8578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Treuter E, Venteclef N. Transcriptional control of metabolic and inflammatory pathways by nuclear receptor sumoylation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1812(8):909–918. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2010.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wang C, Tian L, Popov VM, Pestell RG. Acetylation and nuclear receptor action. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2011;123(3–5):91–100. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2010.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Buler M, Aatsinki SM, Skoumal R, Hakkola J. Energy sensing factors pgc-1alpha and sirt1 modulate pxr expression and function. Biochem Pharmacol. 2011;82(12):2008–2015. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2011.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Nakajima M, Yokoi T. Micrornas from biology to future pharmacotherapy: Regulation of cytochrome p450s and nuclear receptors. Pharmacol Ther. 2011;131(3):330–337. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2011.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Takagi S, Nakajima M, Mohri T, Yokoi T. Post-transcriptional regulation of human pregnane x receptor by micro-rna affects the expression of cytochrome p450 3a4. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(15):9674–9680. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M709382200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Wei Z, Chen M, Zhang Y, Wang X, Jiang S, Wang Y, Wu X, Qin S, He L, Zhang L, Xing Q. No correlation of hsa-mir-148a with expression of pxr or cyp3a4 in human livers from chinese han population. PLoS One. 2013;8(3):e59141. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0059141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Rieger JK, Klein K, Winter S, Zanger UM. Expression variability of adme-related micrornas in human liver: Influence of non-genetic factors and association with gene expression. Drug Metab Dispos. 2013 doi: 10.1124/dmd.113.052126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Staudinger JL, Lichti K. Cell signaling and nuclear receptors: New opportunities for molecular pharmaceuticals in liver disease. Mol Pharm. 2008;5(1):17–34. doi: 10.1021/mp700098c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]