Abstract

Fermenting cells were grown under Fe-deficient and Fe-overload conditions, and their Fe contents were examined using biophysical spectroscopies. The high-affinity Fe import pathway was active only in Fe-deficient cells. Such cells contained ~150 μM Fe, distributed primarily into nonheme high-spin (NHHS) FeII species and mitochondrial Fe. Most NHHS FeII was not located in mitochondria, and their function is unknown. Mitochondria isolated from Fe-deficient cells contained [Fe4S4]2+ clusters, low- and high-spin hemes, S=½ [Fe2S2]1+ clusters, NHHS FeII species, and [Fe2S2]2+ clusters. The presence of [Fe2S2]2+ clusters was unprecedented; their presence in previous samples was obscured by the spectroscopic signature of FeIII nanoparticles which were absent in Fe-deficient cells. Whether Fe-deficient cells were grown under fermenting or respirofermenting conditions had no effect on Fe content; such cells prioritized their use of Fe to essential forms devoid of nanoparticles and vacuolar Fe. The majority of Mn ions in WT yeast cells was EPR-active MnII and not located in mitochondria or vacuoles. Fermenting cells grown on Fe-sufficient and Fe-overloaded medium contained 400 – 450 μM Fe. In these cells the concentration of nonmitochondrial NHHS FeII declined 3-fold, relative to in Fe-deficient cells, whereas the concentration of vacuolar NHHS FeIII increased to a limiting cellular concentration of ~ 300 μM. Isolated mitochondria contained more NHHS FeII ions and substantial amounts of FeIII nanoparticles. The Fe contents of cells grown with excessive Fe in the medium were similar over a 250-fold change of nutrient Fe levels. The ability to limit Fe import prevents cells from overloading with Fe.

Iron plays critical roles in cells, including as redox agents within mitochondrial respiratory complexes and as active-site metals in numerous metalloenzymes (1–3). Iron can also be deleterious, in that certain types of Fe centers, e.g. labile mononuclear nonheme FeII complexes, engage in Fenton chemistry to generate reactive oxygen species (ROS). Thus, Fe trafficking in cells must be highly regulated to allow Fe to be used in cellular functions while also minimizing deleterious side-processes. Understanding the molecular-level details of how cells do this is a current challenge in the field.

Cellular Fe trafficking involves numerous components interacting as a system. Membrane-bound proteins transport Fe across cellular and organellar membranes, while Fe-binding proteins and perhaps low-molecular-mass Fe complexes traffic Fe within aqueous regions of the cell (4). Iron-sensing proteins and DNA-binding transcription factors control gene expression levels of Fe-associated species (5, 6), while various chaperone proteins install Fe ions into myriad target/recipient apo-proteins.

The details of Fe trafficking are best understood in the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae (7). These cells import Fe through several pathways. A high-affinity pathway imports Fe through the Fet3p/Ftr1p complex on the plasma membrane. This pathway allows WT cells to grow under Fe-deficient conditions (8) in which the growth medium is pretreated with bathophenanthroline sulfonate (BPS), a strong chelator of FeII ions. The resulting [FeII(BPS)3]4− complex, generated using endogenous Fe in the growth medium, is inaccessible to cells for growth (9). WT cells growing in Fe-deficient medium express the iron regulon, a group of ca. 20 genes, including FET3 and FTR1 (10). Gene expression is controlled by the transcription factor Aft1p (5, 6, 11). Under Fe-deficient conditions, Aft1p moves from the cytosol to the nucleus where it increases expression of iron regulon genes. Under Fe-sufficient and Fe-overload conditions, Aft1p moves to the cytosol, decreasing expression of these genes. The rate of Fe import into the cell by the high-affinity system is saturable, such that plots of rates vs. the concentration of Fe in the medium ([Femed]) can be fitted to a Michaelis-Menten-type expression with apparent Km ~ 0.2 μM (12–15).

Iron metabolism in cells grown under Fe-deficient conditions is also regulated post-transcriptionally. Cth1p and Cth2p bind to mRNA strands transcribed from various Fe-associated genes (16). This destabilizes those transcripts and curtails protein synthesis. Cth2p binds and destabilizes the mRNA of Ccc1p, the only known Fe importer on the vacuolar membrane. Vacuoles store and detoxify Fe. These transcription factors also destabilize the mRNA of genes involved in Fe/S cluster and heme biosynthesis and respiration. Under Fe-deficient conditions, this regulatory mechanism minimizes the use of Fe by preventing vacuoles from depleting the cytosol of Fe and by curtailing synthesis of Fe-containing proteins.

Fe-sufficient growth conditions are defined here as having 5 – 40 μM Fe in the medium ([Femed]). Cells lacking the high-affinity Fe import pathway can grow under such conditions (9, 17) due to low-affinity pathways. FeII ions can be imported through Smf1p and Fet4p on the plasma membrane, with apparent Km values of 2.2 and 33–41 μM, respectively (13, 18–20). Once imported, Fe is trafficked to vacuoles, mitochondria, and other organelles. CCC1 gene expression is controlled by transcription factor Yap5 which activates CCC1 under intermediate and high cytosolic Fe ([Fecyt]) (21). Once installed in the vacuolar membrane, the newly synthesized Ccc1p imports Fe into the vacuole (22–24). Isolated vacuoles from fermenting cells grown in medium with [Femed] = 40 μM contain a magnetically-isolated mononuclear HS FeIII species (25). In fermenting Fe-sufficient yeast cells, this species represents ~75% of total cellular Fe (26). Fe in vacuoles can also be found as FeIII nanoparticles (25, 27). These organelles export Fe through Fet5p and Fth1p, homologs of the Fet3p and Ftr1p (28), and through Smf3p, a homolog of Smf1p (29).

The same cytosolic Fe species that is imported into vacuoles (30) is presumed to be imported into mitochondria primarily through high-affinity transporters Mrs3/4p (31, 32). High-affinity in this case means that ΔMrs3/4 cells cannot grow on Fe-deficient medium (31, 33), apparently because [Fecyt] in such cells is insufficient to be imported rapidly into mitochondria. Since mitochondria are the sole site of heme biosynthesis in the cell and the major site of Fe/S cluster biosynthesis, Fe-deficient ΔMrs3/4 cells probably cannot generate sufficient quantities of these prosthetic groups. These and other results imply that [Fecyt] is proportional to [Femed], at least under low-Fe conditions. These same strains can grow normally under Fe-sufficient conditions (31), implying that other low-affinity mitochondrial import pathways can operate when [Fecyt] is higher than it is under Fe-deficient conditions.

Little is known about the Fe content and distribution in cells grown under Fe-overload growth conditions, defined here as being > 40 μM. Only at extremely high concentrations is toxicity observed. WT cells grow reasonably well in medium containing as high as 5 mM – 10 mM FeII (34–38) and 20 mM FeIII (27).

We use an integrated biophysical approach centered on Mössbauer spectroscopy to evaluate the Fe content of organelles, cells, and tissues from a systems-level perspective (25, 39–41). In this paper, we analyze WT yeast cells grown on Fe-deficient and Fe-overloaded growth medium, as well as mitochondria isolated there-from. Under Fe-deficient condition, cells prioritize their use of Fe, using it for essential functions that involve Fe/S cluster and heme centers, and minimizing nanoparticles and vacuolar Fe. Cells grown on Fe concentrations ranging from 40 – 10,000 μM [Femed] maintained nearly the same Fe concentration and speciation despite a 250-fold increase in environmental Fe, indicating an amazing ability to regulate Fe import. A model that rationalizes these results is presented.

Experimental Procedures

Cell Growth and Preparation of Samples

WT strain W303-1B and strain DY150, FET3-GFP::KanMX (42) were used. DY150 is isogenic to W303 (43), and it was used for studies involving Fet3-GFP. Cells were grown on minimal medium without added Fe (26, 44, 45), called Fe-unsupplemented. The medium contained (2% w/v) glucose or galactose to establish fermenting or respirofermenting growth modes, respectively. Iron-deficient medium was prepared by adding 21 μM BPS (Sigma-Aldrich) to Fe-unsupplemented minimal medium, followed by supplementing with 1 μM 57Fe(citrate). This corresponded to a molar excess of BPS (the endogenous Fe concentration in minimal medium was ~ 100 nM). 57Fe citrate was prepared by dissolving 57Fe metal powder (IsoFlex USA) in a 1:1 mixture of concentrated trace-metal grade (TMG) HNO3 and HCl (Fisher Scientific) and diluting with double-distilled water. The resulting 80 mM Fe stock contained ~ 0.2% (v/v) acid. The solution was diluted further with distilled water and treated with a 3-fold molar excess of sodium citrate (Fisher Scientific). The solution was adjusted to pH ~ 5 with 1 M NaOH (EMD chemicals) resulting in a final concentration of 40 mM 57Fe citrate.

Fifty mL of Fe-unsupplemented minimal medium was inoculated with a single colony from a YPAD (1% yeast extract, 2% peptone 40 mg/L adenine sulfate, and 2% dextrose) plate. Cells were allowed to grow to an OD600 of 1.0 – 1.4 in a 30 °C rotary incubator at 150 rpm. The culture was used to inoculate fermenting minimal media supplemented with different concentrations of 57Fe citrate. Once the OD600 reached 1.0 – 1.4, cells were collected by centrifugation at 4000×g and rinsed 3× with 100 μM unbuffered EDTA. Subsequently cells were rinsed 3× with water and packed into EPR or Mössbauer cuvettes for analysis.

For cells from which mitochondria were isolated, 50 mL cultures were used to inoculate 1 L of growth medium. Once grown, these cultures were used to inoculate 24 L of medium in a custom glass bioreactor (ChemGlass) maintained at 30 °C. O2 (99.99%) was bubbled through the bioreactor at 2 SCFM with a propeller rotation of 150 rpm. Cells were harvested at an OD600 of 1.0–1.4. Mitochondria were isolated as described (26) with EGTA (1 mM final concentration) present in all buffers. Samples were packed into EPR or Mössbauer cuvettes as described (24) and stored in LN2 for subsequent analysis.

Spectroscopic Analysis

Mössbauer spectra were collected using a model MS4 WRC spectrometer (SEE Co, Edina MN) as described (45). Parameters in the text are reported relative to α-Fe foil at room temperature (RT). Applied magnetic fields were parallel to the gamma radiation. Spectra were simulated using WMOSS software. EPR spectra were collected on an X-band spectrometer (EMX, Bruker Biospin Corp., Billerica MA) with an Oxford Instruments ER910 cryostat. Spin quantifications used a 1.00 mM CuEDTA spin standard and SpinCount software (http://www.chem.cmu.edu/groups/hendrich). UV-vis spectra were collected at RT on a Hitachi 4400U spectrophotometer with a head-on photomultiplier tube. Spectra were analyzed as described for reduced heme a, b, and c content (44).

ICP-MS analysis

Metal concentrations were determined by ICP-MS (Agilent model 7700x). Samples were packed into EPR cuvettes to determine the volume of the cell pellet (typically 200 – 300 μL). Following analysis by EPR, samples were diluted by a known factor while being transferred to a 15 mL screw-top tube containing 100 μL of concentrated trace metal grade HNO3 (Fisher). Tubes were sealed with electrical tape to prevent evaporation, and then incubated overnight at 90° C. Digested samples were diluted with 7.8 mL double-distilled H2O, and then analyzed by ICP-MS. Double-distilled means that the H2O was house–distilled, deionized using exchange columns (Thermo Scientific 09-034-3), and distilled again using a sub-boiling still (Savillex DST-1000).

Fet3-GFP Expression Western Blot

Cells were grown to an OD(600) of 1.0 – 1.2 on minimal medium supplemented with 21 μM BPS and various concentrations of Fe under both fermenting and respirofermenting conditions. Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 4000×g, rinsed 3× with unbuffered EDTA (100 μM), then 3× with water. A portion of the resulting material was saved for Western blot analysis; the remainder was packed into EPR or Mössbauer cuvettes. Protein concentrations were measured (44) and 60 μg protein of each sample were added per lane of the SDS-PAGE gel. Proteins were separated and transferred to a PVDF membrane as described (26). The membrane was then incubated with antibodies against GFP and actin (Thermo Scientific) with the actin serving as a loading control. OxyBlot assays were performed as suggested by the manufacturer (Millipore).

Results

Iron-Deficient Cells

For this study, iron-deficient means that BPS was added to the growth medium to chelate endogenous unenriched Fe and that 1 μM 57FeIII citrate was subsequently added to enhance Mössbauer spectral intensity. Fe-deficient cells were grown with either glucose or galactose as the carbon source. Yeast cells exclusively ferment when grown on glucose whereas they both respire and ferment (called respirofermenting) when grown on galactose. In a previous study, we grew cells under respirofermenting conditions using minimal medium supplemented with 40 μM 57Fe (44). The Fe content (i.e. the types of Fe centers and percentages of each type) of those cells was essentially indistinguishable from that of cells grown on glycerol, a respiration-only carbon source. Thus, at the resolution of our experiments, respirofermentation essentially mirrors respiration. Growing cells on galactose is more convenient than growing them on glycerol, and so galactose-grown cells were used here. We will refer to BPS-treated fermenting and respirofermenting cells as BPS-F and BPS-RF cells, respectively.

Harvested BPS-F cells were rinsed with distilled and deionized water to remove [FeII(BPS)3]4−, and then packed into Mössbauer cups. The low-temperature, (6 ± 1 K) low-field (0.05 T) Mössbauer spectrum of these pinkish cells (Figure S1, A) exhibited poor S/N due to the low concentration of 57Fe. An unresolved resonance in the center of the spectrum dominated. Authentic [FeII(BPS)3]4− exhibited a similar feature (Figure S1, B), suggesting that the BPS-F sample contained [FeII(BPS)3]4− despite having been rinsed extensively. We subtracted the [FeII(BPS)3]4− spectrum from that of the BPS-F cells, at 35% intensity, resulting in the spectrum of Figure 1B. Thus, only ca. 65% of the total Fe in the packed sample (Table 1; 240 μM × 0.65 = 156 μM) was due to Fe contained in the BPS-F cells. Parenthetically, the concentration of [FeII(BPS]3]4− in the packed sample was substantially higher than the maximum possible concentration of [FeII(BPS]3]4− in the medium (i.e. ~ 0.1 μM), suggesting that [FeII(BPS)3]4− collected on the cell’s exterior. In principle, BPS could have penetrated the cell, but the charge on the complex probably discouraged this. Our packed pellets contain 70% cells and 30% buffer (46). The concentrations in Table 1 have been corrected for this 0.7 packing efficiency.

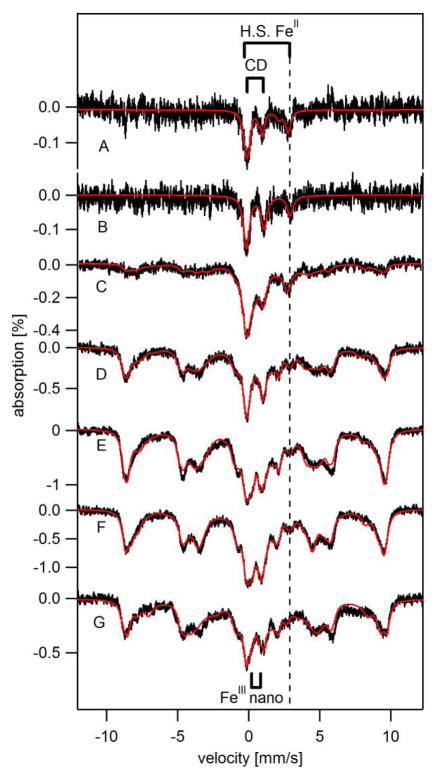

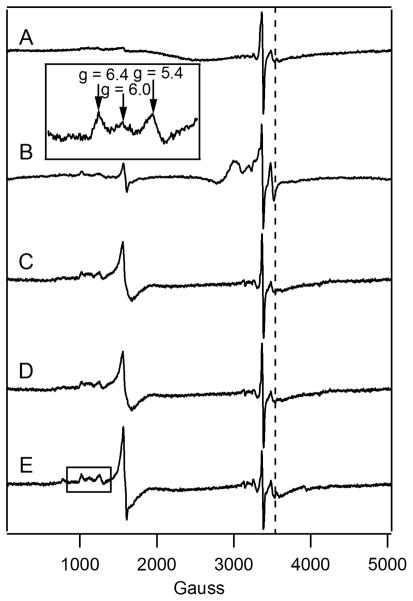

Figure 1. Mössbauer spectra (5 – 7 K, 0.05 T parallel field) of 57Fe-enriched yeast cells at various [Fe]med.

A, BPS-RF; B, BPS-F; C, 1-F; D, 10-F; E, 100-F; F, 1000-F; and G, 10,000-F. Red lines are simulations assuming percentages given in Table 1. Spectrum B was obtained by subtracting a contribution of the [FeII(BPS)3]4− spectrum from the raw spectrum (shown in Figure S1 A). Spectrum C has been published (46). Red lines in B – F are four-term simulations assuming the CD (δ= 0.45 mm/sec, ΔEq = 1.15 mm/sec) and NHHS FeII doublets (δ= 1.3 mm/sec, ΔEq = 3.1 mm/sec), a mononuclear HS FeIII sextet, and a nanoparticle doublet (δ= 0.5 mm/sec, ΔEq = 0.6 mm/sec). The HS FeIII sextet was simulated using D = 0.5 cm−1, E/D = 0.33, ΔEQ = 0.10 – 0.14 mm/s, η =2.8, A0/gN·βN = −238 kG, δ = 0.54 mm/s, Γ= 0.9 mm/s. Assumed temperature in C – G was 5, 6, 5, 7, and 6 K, respectively.

Table 1. Characteristics of Isolated Mitochondria and Whole cells.

Metal numbers, percentages used for Mössbauer spectral simulation, spin intensities of EPR signals, and concentrations of heme centers from UV-vis spectra. Percentages are based on corrected Mössbauer spectra where applicable. For fermenting mitochondria obtained from cells grown with 100 μM Fe in the medium, the two numbers listed for percentage refer to each of the two batches examined. EPR and ICP-MS data have been corrected for packing efficiency. Numbers in parenthesis represent number of trials (n) if different from 1. Estimated uncertainties in Mössbauer percentages are ± 4%, except for the sample obtained under Fe-deficient conditions in which the uncertainty is ± 7%. Uncertainties for EPR spin quantifications are ± 25%. Metal concentrations in cells have not been corrected for adventitious FeBPS bound on the cell’s exterior.

| Whole Cells | Respiroferm. | Ferm. | Ferm. | Ferm. | Ferm. | Ferm. | Ferm. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [Fe]medium (μM) | BPS + 1 | BPS + 1 | 1 | 10 | 100 | 1,000 | 10,000 |

| [Fe]cell (μM) | 170 ± 50 (3) | 240 ± 80 (3) | 250 (1) | 395 ± 40 (3) | 470 ± 100 (3) | 440 80 (3) | 450 (1) |

| [Cu]cell (μM) | 62 ± 25 (3) | 280 ± 20 (3) | --- | 26 ± 6 (3) | 20 ± 6 (3) | 35 ± 8 (3) | 90 (1) |

| [Mn]cell (μM) | 16 ± 7 (3) | 17 ± 4 (3) | --- | 14 ± 4 (3) | 17 ± 3 (3) | 39 ± 10 (3) | 30 (1) |

| [Zn]cell (μM) | 160 ± 40 (3) | 560 ± 70 (3) | --- | 600 ± 100 (3) | 570 ± 70 (3) | 1300 ± 130 (3) | 300 (1) |

| NHHS Fe3+ (%) | ~ 0 | ~ 0 | 40 | 76 | 80 | 75 | 84 |

| CD (%) | 43 | 36 | 22 | 18 | 10 | 5 | 3 |

| NHHS Fe2+ (%) | 39 (66 μM) | 26 (62 μM) | 26 (65 μM) | 7 (26 μM) | 5 (23 μM) | 6 (26 μM) | 5 (22 μM) |

| Nanoparticles (%) | 18 | ~ 0 | 12 | ~ 0 | 4 | 18 | 10 |

| [Fe2+(BPS)3]4− (%) | 12 | 35 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| g = 4.3 (μM) | ~ 0 | 14 | --- | 130 | 360 | 320 | 290 |

| g = 2.0 region (μM) | 26 | 14 | --- | 16 | 15 | 28 | 27 |

| Mitochondria | Respiroferm. | Ferm. | Ferm. | Ferm. | Ferm. | Ferm. | Ferm. |

| [Fe] (μM) | 300 | 480 ± 160 (2) | --- | 544 ± 70 (2) | 710 (1) | 840 ± 200 (3) | 500 |

| [Cu] (μM) | 270 | 80 | --- | 48 ± 13 (2) | 52 (1) | 60 ± 20 (3) | 65 |

| [Mn] (μM) | 12 | 13 | --- | 12 ± 3 (2) | 11 (1) | 10 ± 2 (3) | 22 |

| [Zn] (μM) | 250 | 570 | --- | 236 ± 100 (2) | 350 (1) | 450 ± 200 (3) | 150 |

| NHHS Fe3+ (%) | ND | < 15% | --- | < 15% | 51, 0 | --- | --- |

| CD (%) | 63 | 59 | --- | 11 | 12, 34 | --- | --- |

| NHHS Fe2+ (%) | 14 | 7 | --- | 28 | 18, 36 | --- | --- |

| HS Fe2+ Heme (%) | 7 | 9 | --- | ~ 0 | ~ 0 | --- | --- |

| nanoparticles (%) | ND | < 10% | --- | 57 | 27 | --- | --- |

| S = 0 [Fe2S2]2+ (%) | ND | 12 | --- | ND | ND | --- | --- |

| S = ½ [Fe2S2]1+ (%) | ND | 12 | --- | ND | ND | --- | --- |

| [g = 4.3] (μM) | ND | ND | --- | 20 | 20 | 28 | --- |

| [Heme a] (μM) | 30 | 30 | --- | 24, 43 | 27 | 13 | 23 |

| [Heme b] (μM) | 70 | 72 | --- | 64, 58 | 78 | 21 | 40 |

| [Heme c] (μM) | 120 | 120 | --- | 110, 129 | 130 | 40 | 97 |

The corrected BPS-F whole-cell Mössbauer spectrum was dominated by a quadruple doublet (δ = 0.45 mm/s, ΔEQ = 1.15 mm/s) indistinguishable from the Central Doublet (CD) identified previously (47). This doublet arises from S = 0 [Fe4S4]2+ clusters and LS FeII heme centers (47). A second prominent feature was a quadrupole doublet with parameters typical of nonheme high-spin (NHHS) FeII (δ = 1.2 mm/s and ΔEQ = 3.1 mm/s). Percentages of these and all other spectral components are given in Table 1. We estimate that the CD- and NHHS FeII –associated species in BPS-F cells are present at ca. 90 and 60 μM Fe, respectively. No other features, including those from FeIII oxyhydroxide (phosphate) nanoparticles or mononuclear HS FeIII species, were evident, though minor contributions could have escaped detection due to the poor S/N ratio.

The corresponding Mössbauer spectrum of BPS-RF cells also exhibited poor S/N. In this case a 12% contribution of the [FeII(BPS)3]4− spectrum was subtracted, affording the corrected spectrum shown in Figure 1A. The spectrum was similar to that of BPS-F cells, including major contributions from CD and NHHS FeII features. The absolute concentrations of these features were also similar (73 and 66 μM, respectively). A minor feature arising from HS FeII hemes may be evident in the BPS-RF spectrum, but the low S/N makes this assignment uncertain. In any event, the Mössbauer spectra of the two BPS-treated samples were very similar despite the fact that cells were grown in different metabolic modes.

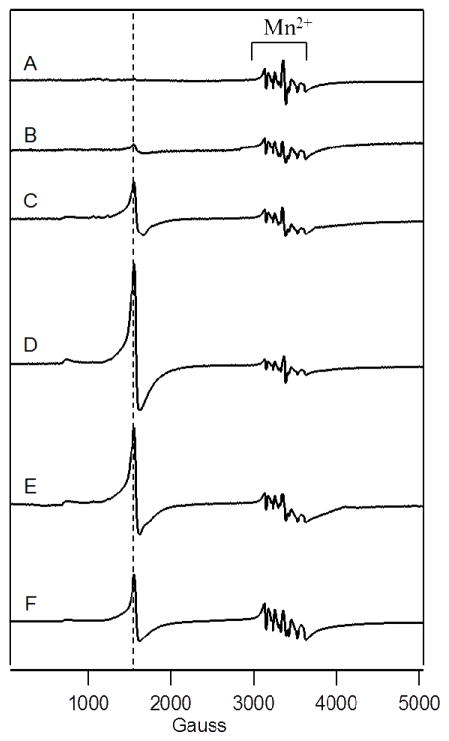

EPR spectra of BPS-F and BPS-RF cells were also similar. Both exhibited low-intensity signals in the g = 2 region from MnII ions, as evidenced by the hyperfine splitting arising from the I = 5/2 Mn nucleus (Figure 2, A and B). Such signals were observed in all whole-cell spectra (Figure 2, A – F) with similar intensities regardless of [Femed]. Also evident in the EPR spectra of BPS-F and BPS-RF cells were features at g ≈ 2.01, g ≈ 4.3, and minor features in the g = 6 region. The g = 4.3 signal is due to mononuclear HS FeIII ions with E/D ~ 1/3. The features at g = 6.4, 6.0 and 5.4 originate from a partially-oxidized state of cytochrome c oxidase (47, 48). No signals from Cu ions were observed, despite the relatively high concentration of Cu in all 3 BPS-F samples examined. Most Cu ions in these cells are probably in the diamagnetic CuI state, though there may be other reasons for the EPR silence.

Figure 2. 10 K X-band EPR spectra of unenriched fermenting whole cells.

A, BPS-RF; B, BPS-F; C, 10-F; D, 100-F; E, 1000-F; and F, 10,000-F. Other EPR conditions were: microwave frequency, 9.46 GHz; microwave power, 0.2 mW; modulation amplitude, 10 G; modulation frequency, 100 kHz; time constant, 335 sec; sweep time, 165 sec. The dashed line indicates g = 4.3.

Mitochondria from Fe-deficient Cells

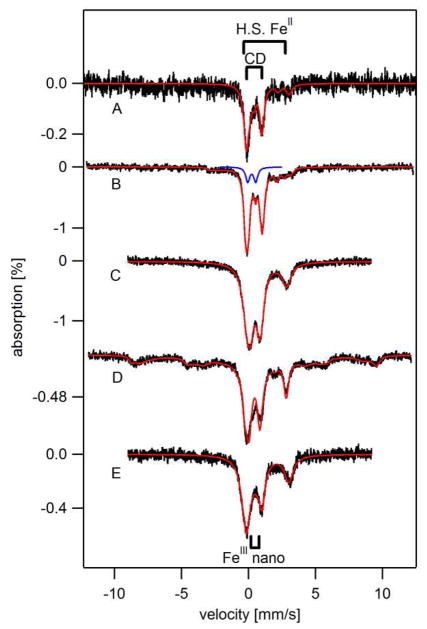

The pinkish color of the BPS-treated cells was absent in the corresponding isolated mitochondria, indicating that the BPS-Fe complex that adhered to the cell exterior was removed during this process. The 6 K, 0.05 T Mössbauer spectrum of mitochondria isolated from BPS-F cells – called “BPS-F mitochondria” (Figure 3B) – was dominated by the CD. Also present was a feature exhibiting magnetic hyperfine interactions that probably arose from S = ½ [Fe2S2]1+ clusters, e.g. the cluster in the Rieske protein associated with cytochrome bc1 (49). HS heme and nonheme FeII species were also present, as evidenced by the high-energy lines of the associated quadrupole doublets in the spectra.

Figure 3. 6 K, 0.05 T Mössbauer spectra of isolated mitochondria.

A, from BPS-RF cells; B, BPS-F cells; C, 10-F cells; D, 100-F cells; E, 100-F cells with 1 mM dithionite added in 0.6 M sorbitol and 0.1M Tris, pH 8.5. Red lines are simulations using percentages listed in Table 1. The blue line is a quadrupole doublet (δ = 0.3 mm/s; ΔEQ = 0.6mm/s) typical of S = 0 [Fe2S2]2+ clusters.

BPS-F mitochondria were largely devoid of FeIII oxyhydroxide nanoparticles, as the doublet due to this species falls between the well-resolved lines of the CD. Indeed, the resolution between the CD lines was sufficient to discern a resonance near ~ 0.6 mm/s that was assigned to the high-energy line of a quadrupole doublet arising from S = 0 [Fe2S2]2+ clusters. The blue line in Figure 3B is a simulation of that doublet. Such clusters in the oxidized diamagnetic 2+ state have not been observed previously in any Mössbauer spectra of mitochondria, perhaps because previous spectra inevitably included contributions from nanoparticles (26, 44) which absorb in the same region. The absence of intense NHHS FeII and nanoparticle doublets rendered the BPS-F spectrum more reminiscent of that obtained from 40-RF mitochondria (44), which also lacked these doublets, than from the spectrum of 40-F mitochondria which included them. However, even in 40-RF mitochondria, no feature arising from S = 0 [Fe2S2]2+ clusters was discerned. Percentages used to fit the Figure 3B spectrum are given in Table 1.

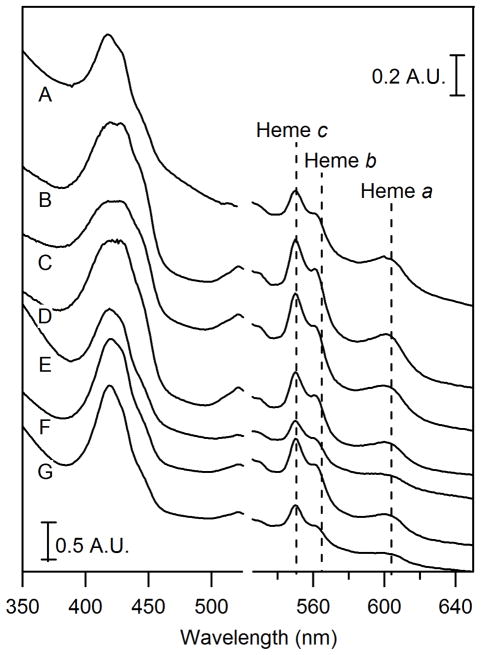

The UV-vis spectrum of BPS-RF and BPS-F mitochondria (Figure 4, A and B) exhibited features due to FeII heme centers. The concentrations of reduced hemes a, b, c (Table 1) were similar to those reported for 40-R mitochondria (44). The 10 K X-band EPR spectrum of BPS-RF and BPS-F mitochondria (Figure 5, A and B) exhibited low-intensity signals at g = 6.5, 5.4, and 4.3. The first two signals probably arose from the a3:Cub site of cytochrome c oxidase (48), while the g = 4.3 signal arose from a rhombic HS FeIII species in BPS-F mitochondria. The g = 2 region lacked the MnII signal that was evident in whole-cell spectra, indicating that the ions affording that signal are not located in mitochondria.

Figure 4. UV-vis spectra of isolated mitochondria.

A, BPS-RF; B, BPS-F; C, 10-F; D, 100-F; E, 1000-F; F, 10-F from a second batch; G, 10000-F from the second batch.

Figure 5. EPR of isolated mitochondria.

A, BPS-RF; B, BPS-F cells; C, 10-F cells; D, 100-F cells; and E, 1000-F cells. Spectrum A is matched to Figure 3A; spectrum B is matched to spectrum 3B. EPR conditions were as in Figure 2. The dashed line indicated g = 1.94.

Fe-Sufficient Cells and Mitochondria

For comparison, we examined fermenting cells grown on medium supplemented with 1 μM (with no BPS) and 10 μM 57Fe. Mössbauer spectra of 1-F and 10-F cells (Figure 1, C and D) exhibited features due to mononuclear HS FeIII, the CD, NHHS FeII, and FeIII oxyhydroxide nanoparticles (percentages given in Table 1). The main difference in these spectra was in the percentage of the HS FeIII sextet. For 10-F cells, this percentage was more than double that in the 1-F spectrum. This feature undoubtedly arose from Fe within isolated vacuoles (25), indicating that vacuolar Fe is essentially absent in BPS-F and BPS-RF cells and that it starts to accumulates as cells grow in medium containing 1 – 10 μM Fe. ICP-MS analysis indicated that ~100 μM of the Fe in 1-F cells and ~300 μM Fe in 10-F cells were associated with vacuoles. This corresponded to 40% and 76% of cellular Fe, respectively.

EPR spectra of 10-F cells (Figure 2C) were generally similar to those of BPS-RF and BPS-F cells (Figure 2, A and B), except for a more pronounced g ≈ 4.3 signal. This is consistent with an increased concentration of the vacuolar mononuclear HS FeIII species in the 10-F cells.

Interestingly, the absolute concentration of NHHS FeII ions in the cells (obtained by multiplying the cellular Fe concentration by the fractional Mössbauer intensity) declined significantly (3-fold) as [Femed] increased from 1 → 10 μM. The average NHHS FeII concentration was 64 ± 2 μM in the BPS-F, BPS-RF and 1-F samples, and 24 ± 2 μM in the 10-F, 100-F, 1000-F and 10,000-F cells (Table 1).

The low-temperature, low-field Mössbauer spectrum of 10-F mitochondria (Figure 3C) was nearly indistinguishable from that of 40-F mitochondria (26). Relative to BPS-RF and BPS-F mitochondria, 10-F mitochondria exhibited considerably more FeIII oxyhydroxide nanoparticles (Table 1). UV-Vis (Figure 4C) and EPR (Figure 5C) spectra of 10-F mitochondria were also similar to those of 40-F mitochondria (44). The UV-Vis spectrum exhibited FeII heme concentrations similar to those seen in the BPS-F sample (Table 1). The concentration of Fe in the 10-F sample was reduced relative to in the 40-F sample.

Fe-Overload conditions

The Fe concentrations in 100-F, 1000-F and 10,000-F cells were similar to each other and to that of cells grown on 10 μM Fe (Table 1), despite the 1000-fold range of [Femed]. The Mössbauer spectra of these cells (Figure 1, E – G) were also remarkably similar to each other and to spectra of 40-F cells; they exhibited similar contributions of the CD, the NHHS FeII doublet and FeIII nanoparticles. 100-F cells contained a slightly lower concentration of FeIII nanoparticles relative to the other two samples. However, no general trend was apparent, in that the 1000-F sample exhibited a higher concentration of FeIII nanoparticles than did 10,000-F cells. The main point is that a 250-fold change in [Femed] (from 40 → 10,000 μM) had little effect on the concentration or distribution of Fe within fermenting cells. The only noticeable exception was a gradual but significant decline of the CD intensity as [Femed] increased (Table 1).

100-F, 1000-F and 10,000-F cells exhibited EPR spectra (Figure 2, C – E) similar to those of 10-F cells, except for more intense g ≈ 4.3 signals. Spin concentrations of the g = 4.3 signal (Table 1) represented ~70% of the Fe concentration associated with the HS FeIII sextet in the corresponding Mössbauer spectra. Although not a perfect match, this percentage indicates an acceptable congruence between the two types of measurements.

The 5K, low-field Mössbauer spectra of isolated 10-F (Figure 3C), 40-F (26), and 100-F mitochondria (Figure 3D) all included the CD, a HS FeII doublet, and a doublet due to FeIII nanoparticles in approximately the same relative amounts. The 100-F sample also exhibited a sextet due to mononuclear HS FeIII species representing ca. 40% of the spectral intensity. 40-F mitochondria exhibited a similar feature but representing just 15% of spectral intensity (26).

The greater intensity of the sextet in the 100-F mitochondria spectrum prompted us to consider whether the additional HS FeIII ions were located in the mitochondria or whether they were an artifact of purification and bound on the exterior of the organelle. To address this, we isolated a second batch of 100-F mitochondria including the reductant dithionite in the buffer. Dithionite does not appear to penetrate mitochondrial membranes (26). The resulting spectrum (Figure 3E) showed no evidence of the sextet, suggesting that most or all of the Fe associated with this feature in first sample was artifactual. The expense associated with preparing 57Fe-enriched 100-F mitochondria from 24 L of cells prohibited us from exploring this issue further.

100-F and (unenriched) 1000-F mitochondria exhibited the same EPR signals with about the same relative intensities (Figure 5, D and E). 10-F (Figure 5C) and 40-F (44) mitochondria exhibited very similar spectra. Importantly, the intensities of the g = 4.3 signal in the 100-F and 1000-F spectra were not higher than those in the 10-F or 40-F spectra. This is further evidence that the more intense HS FeIII sextet observed in Mössbauer spectra of one batch of 100-F mitochondria was an artifact of that particular preparation. We conclude that the Fe content of 10-F, 40-F and 100-F mitochondria is approximately the same.

A 100-F mitochondria sample exhibited a UV-Vis spectrum (Figure 4D) similar to that of 10-F mitochondria (Figure 4C) while a 1000-F sample (Figure 4E) showed diminished intensities (heme concentrations are given in Table 1). To address whether this decline reflected a cellular response to toxic levels of Fe in the growth medium, we isolated two batches of mitochondria, from cells grown with 10 (control) and 10,000 μM [Femed] in the growth medium. Both batches of cells grew at nearly the same rate; i.e. the 10,000 μM sample showed essentially no sign of toxicity. Oxyblot analysis of extracts of the two organelles (Figure S2) indicated just 10% more ROS damage in the 10,000-F sample relative to the 10-F sample. ICP-MS analysis indicated insignificant differences in the concentration of Fe in the organelles (Table 1). However, corresponding UV-vis spectra indicated a decline in reduced heme intensities (Figure 4, F and G, and Table 1). The decline of heme intensity in Figure 4E and G appears to be real. We conclude that Fe concentrations in the growth medium as high as 10,000 μM FeIII citrate have insignificant effects on the growth rate of the cell, the level of ROS damage, and the Fe concentration of cells and their mitochondria and vacuoles. However, there does appear to be a decline in the level of [Fe4S4]2+ clusters FeII hemes at very high [Femed].

Fet3-GFP Expression Levels in Fermenting and Respirofermenting Cells

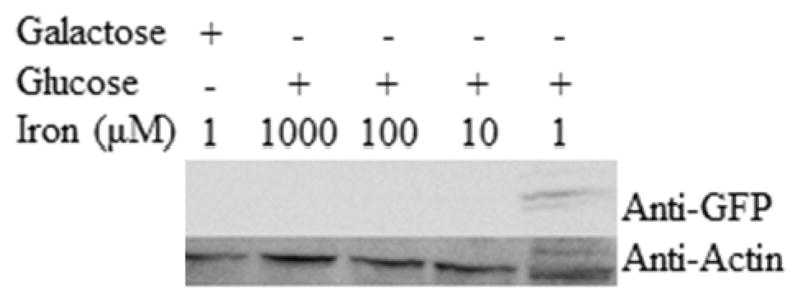

The DY150, FET3-GFP::KanMX strain biosynthesizes the green fluorescent protein (GFP) fused to Fet3p (42). We used this strain to perform a Western blot using an antibody against GFP as a reporter for Fet3p expression. The analysis was performed on cells grown under fermenting (and BPS-RF) conditions and supplemented with various concentrations of Fe in the growth medium. Fet3p was detected only in the BPS-F sample (Figure 6, right-most lane). Three bands were observed, with the middle band displaying the highest density and the upper band ~ 7-times less intense but visible nevertheless. Since bands were not visible in any other lane, the concentration of Fet3-GFP in the BPS-F sample appears to have been at least 10-times greater than in the other samples, assuming no threshold effects. This suggests that the Aft1-controlled Fe regulon was effectively shut down when cells were grown in medium containing > ca. 1 μM of Fe. Fe-deficient respirofermenting cells do not appear to utilize the Fe regulon, as no Fet3p expression was observed.

Figure 6. Western Blot of Fet3-GFP cells grown at various conditions.

Actin was added as a loading control. BPS was added to all samples.

Discussion

The Fe-Deficient State

Fermenting WT yeast cells grown under Fe-deficient conditions prioritize their use of Fe for essential functions. Such cells were devoid of vacuolar HS FeIII, a storage form of Fe that is not essential, and were largely devoid of FeIII oxyhydroxide (phosphate) nanoparticles, which do not seem to function in cellular Fe metabolism. Fe-deficient cells had a total Fe concentration of ca. 150 μM, distributed into two major groups. About 80 μM was present as S = 0 [Fe4S4]2+ clusters and LS FeII hemes (the two types of Fe cannot be distinguished by Mössbauer), most of which are undoubtedly associated with mitochondria and respiration. About 60 μM cellular Fe corresponded to NHHS FeII species. About the same distribution of Fe was observed in both fermenting and respirofermenting Fe-deficient cells.

Mitochondria from Fe-deficient fermenting and respirofermenting cells also prioritize their use of Fe; they contained similar levels of respiratory complexes relative to Fe-sufficient mitochondria, but lower concentrations of nanoparticles and NHHS FeII/FeIII species. This distribution was more typical of Fe-sufficient mitochondria from respiring cells (44). We previously proposed that the NHHS FeII and FeIII species in mitochondria are in equilibrium with each other and with the nanoparticles contained therein, and that the NHHS FeII species constitutes a pool of Fe used for heme and Fe/S cluster biosynthesis (26). This size of this pool declines in respiring mitochondria, which is consistent with the higher rates of Fe/S cluster and heme biosynthesis. The lower concentrations of this pool observed in Fe-deficient mitochondria might arise instead from a diminished rate of Fe import from the cytosol into mitochondria due to Fe-deficient conditions.

A Non-mitochondrial NHHS FeII Pool

The concentration of NHHS FeII in isolated Fe-deficient mitochondria was ~ 40 μM. What proportion of the NHHS FeII pool observed in whole cells is due to the NHHS FeII species in mitochondria? Mitochondria in fermenting cells occupy between 3% and 10% of cell volume (50). This means that the concentration of mitochondrially-associated NHHS FeII species in Fe-deficient cells is 1.2 – 4 μM (i.e. 40 μM × (0.03 to 0.1)). Since the observed concentration of NHHS FeII in Fe-deficient whole cells was ~ 60 μM, we conclude that > 90% of the NHHS FeII in whole cells is not located in mitochondria. Nor does this non-mitochondrial pool appear to be located in vacuoles (25). As a working hypothesis, we propose that the pool of NHHS FeII in Fe-deficient cells is located in the cytosol.

Decrease in Non-mitochondrial NHHS FeII as [Femed] increases

Under Fe-sufficient and Fe-overload conditions, mitochondria contained ~ 150 μM NHHS FeII – a 3-fold increase relative to under Fe-deficient conditions. Under these high-Fe conditions, our calculations suggest that as much as 60% of the NHHS FeII species present in whole cells is now located in mitochondria. Thus, the decline of non-mitochondrial NHHS FeII as cells transition from being Fe-deficient to Fe-sufficient (60 → 25 μM) is more dramatic than implied by the ratio 60:25. These results suggest that during the transition from 1 → 10 μM [Femed], most of the non-mitochondrial (probably cytosolic) NHHS FeII species of whole Fe-deficient cells moves into the mitochondria where they contribute to the NHHS FeII pool (and ultimately nanoparticles) in this organelle.

Occurring in approximately the same transition period was a decline in the expression of the Fe regulon as reported by Fet3p, confirming previous studies that Aft1-dependent expression of the Fe regulon is effectively abolished at > 1 μM [Femed] (10, 51). The low-affinity pathways play the major role in regulating cellular Fe beyond this transition. The transition of non-mitochondrial NHHS FeII into the mitochondria (or vacuoles) might be related to the switch from high- to low-affinity Fe regulatory mechanisms or to the activation of CCC1.

Accumulation of Vacuolar Fe

The lack of vacuolar Fe in Fe-deficient cells is probably due to the lack of Ccc1p on the vacuole membrane caused by destabilization of CCC1 mRNA by Cth1p/2p under Fe-deficient conditions (the process also requires Aft1p/2p) (52). Cth1p/2p also destabilize the mRNA of genes involved in Fe/S cluster and heme biosynthesis and the mRNA of numerous Fe/S-containing and heme-containing proteins. Our results support previous studies regarding the effects of Cth1p/2p on CCC1p, but do not indicate lower concentrations of Fe/S cluster or heme centers in Fe-deficient cells or mitochondria. This is probably because we supplemented the BPS-treated medium with 1 μM 57Fe (to allow Mössbauer analysis), which rendered our cells less rigorously Fe-deficient than the BPS-treated cells of Thiele and coworkers (21). We suspect that their Fe-starved cells shut down Fe/S cluster and heme assembly in a final attempt to survive.

CCC1 gene expression increases dramatically between [Femed] = 5–50 μM (21), consistent with the increased level of vacuole Fe that we observed as [Femed] increased. In this case, the increased CCC1 expression level is probably due to Yap5p, an Fe-inducible transcription factor. As the concentration of Ccc1p on the vacuolar membrane increases, vacuoles import Fe such that the vacuoles in cells grown on 1, 10 and 40 μM Fe are ca. 0, 40%, and 100% filled.

The concentration of Fe that can be associated with vacuoles maximizes between 300 – 350 μM. We have previously estimated that the Fe concentration in vacuoles in cells grown on 40 μM Fe is ~ 1.2 mM, based on the assumption that these organelles occupy ca. 25% of cell volume (26, 46). Our results indicate that cells limit the storage of HS FeIII in vacuoles to this cellular Fe concentration, regardless of the concentration of Fe in the growth medium. Whether they do this by limiting the percentage volume of vacuoles in the cell and/or the concentration of mononuclear HS FeIII contained therein is uncertain.

The total Fe concentration in fermenting cells is also limited, with a minimum of ca. 160 μM in Fe-deficient cells. This concentration gradually increasing as vacuoles fill and other changes occur, maximizing at ca. 450 μM in cells grown in Fe-overloaded medium. The increase in cellular Fe concentration is largely (but not entirely) due to the vacuoles filling with Fe, suggesting that the [Fe] of all non-vacuolar Fe components of the cell are roughly invariant (at ~ 160 μM) during this process. The majority of this invariant portion of cellular Fe is mitochondrial.

Modest Changes in the Fe Distribution in the Cells grown on Fe-overloaded Medium

The concentration of Fe in cells and the distribution of that Fe into different groups is roughly invariant over a 250-fold range of [Femed] (40 → 10,000 μM). In this region, Fe is being imported via low-affinity pathways. The invariant Fe concentration suggests that the low-affinity pathway must be saturated throughout this 250-fold interval. The Fe import velocity might be saturable, in which case a Michaelis-Menten-like expression with Km-app ~ 15 μM Fe could simulate this effect. This is within a factor of 2 of previous estimates of the apparent Km for the low-affinity transporter (13, 19, 20). Our results also reveal why WT yeast cells grow well under high-Fe (5–10 mM) conditions – namely because they prevent excess environmental Fe from being imported (rather than, for example, having special mechanisms to detoxify excess imported Fe).

Two modest but noticeable changes in the Fe distribution of such cells were a decline in the concentration of Fe associated with the Mössbauer central doublet and heme centers as [Femed] increased. Under Fe-deficient conditions, the cellular CD concentration was ca. 80 μM whereas with [Femed] = 1, 10, 100, 1000 and 10,000 μM, it was 55, 71, 47, 22 and 14 μM, respectively. UV-Vis spectra also showed some decline in heme features at high medium Fe concentration. These declines might reflect a decline in the fractional cellular volume occupied by mitochondria or a decline in the concentration of Fe-rich respiratory complexes. More extreme declines of these centers under even higher medium Fe concentrations might be responsible for the Fe-associated toxicity that is eventually observed.

Cellular Manganese

Comparing the ICP-MS-detected Mn concentrations to the spin concentrations of the Mn-associated EPR signal (Table 1, “g = 2.0 region”) indicates that the majority of Mn ions in the cells are mononuclear MnII species that exhibit(s) the EPR signal. This differs from the study of Chang and Kosman (53) who reported that the majority of cellular Mn is EPR-silent. McNaughton et al. used ENDOR spectroscopy to investigate the species affording this signal (54) and determined that > 70% of the contributing species are MnII ions coordinated with phosphate and/or polyphosphate anions. The absence of these signals in isolated mitochondria and vacuoles (25) suggests that these MnII(phosphate/polyphosphate) species are not located in either of these organelles. The concentration of MnII(phosphate/polyphosphate) species in our fermenting yeast cells appears to be 10 – 30 μM, regardless of [Femed].

Summary Model

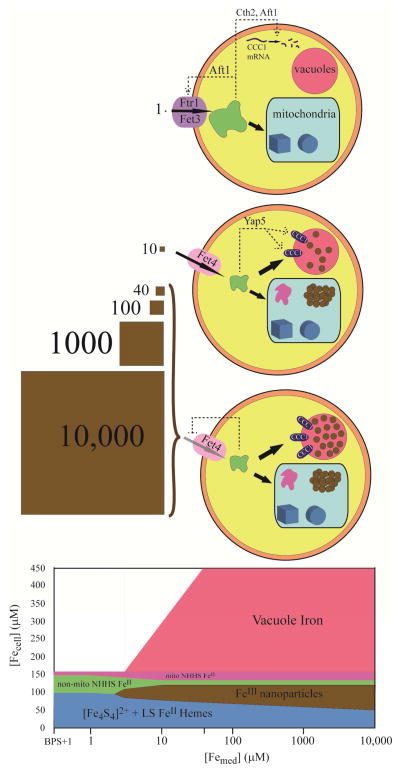

The major results of this study can be summarized by the model of Figure 7. The high-affinity Fe import pathway operates when [Femed] ≤ ca. 1 μM (BPS-treated plus 1 μM 57Fe). Under these conditions, the cell is Fe-deficient and must prioritize its use of Fe. Most of this precious commodity goes to the mitochondria where it is assembled into Fe/S clusters and heme centers, prosthetic groups that are critical for cellular metabolism. Little Fe is stored in vacuoles and little is present as FeIII nanoparticles. A significant portion of cellular Fe in Fe-deficient cells is in the form of NHHS FeII and is probably located in the cytosol. At [Femed] ~ 10 μM, the high-affinity pathway is shut-down and Fe is regulated by low-affinity pathways. The mitochondria remain the site where much imported Fe is sent for Fe/S cluster and heme synthesis. Additional Fe is imported (perhaps from the cytosolic pool of NHHS FeII), increasing the pool of mitochondrial NHHS FeII and FeIII oxyhydroxide nanoparticles. Cytosolic NHHS FeII species declines as some becomes stored in vacuoles as nonheme HS FeIII species. When [Femed] = 40 – 10,000 μM, the vacuoles are filled with Fe, and little else changes in terms of Fe content and distribution. The low-affinity import pathways are saturated in accordance with apparent Km 15 – 30 μM, limiting Fe import at this [Femed] concentration and higher. This prevents high concentrations of environmental Fe from entering the cell and causing toxicity. These regulatory properties allow fermenting yeast cells to grow on medium with Fe concentrations that vary over 4 orders of magnitude, an impressive feat by any standard!

Figure 7. Model of Fe distribution and regulation in fermenting yeast cells.

Top, Fe-deficient; middle, Fe-sufficient; bottom, Fe-loaded. The concentration of FeIII citrate in the growth medium (in μM) is indicated by the brown squares. Two import pathways are shown, including the high-affinity pathway (Aft1 regulating the iron regulon including Fet3p) and the low-affinity pathway (Fet4p-based). Also shown are mitochondria (blue rectangular shape) and vacuoles (red sphere). Under Fe-deficient conditions, Fe is imported via the high-affinity pathway; a portion is imported into mitochondria where Fe/S clusters (brown cube) and heme centers (disks) are predominantly made. Most of the rest of the imported Fe is present as a non-mitochondrial NHHS FeII pool (shown here in the cytosol, but this is not known). Aft1p is sensing a small portion of this pool. The vacuoles are empty because Cth2 working with Aft1p is activated by the absence of cytosolic Fe to degrade CCC1 mRNA. Under Fe-sufficient conditions, the high-affinity pathway is shut-down and the majority of Fe is imported via the low-affinity pathway. The concentration of nonmitochondrial NHHS FeII is reduced 3-fold, perhaps because a portion is imported into mitochondria and converted to nanoparticles (clumps of brown circles) and NHHS FeII and FeIII. The vacuoles are partially filled with mononuclear HS FeIII species, due to the absence of the Cth2 effect and the presence of Yap5p-dependent expression of CCC1. Under Fe-overload conditions, the Fe content is similar to that under Fe-sufficient conditions except that the vacoules are filled completely. The low-affinity import pathway is saturable such that a 250-fold change in the Fe concentration of the medium does not significantly impact the cellular Fe content. The bottom panel summaries these changes. Percentages of various species are approximate, and minor unassigned species are not included.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Jerry Kaplan (University of Utah) for kindly providing the DY150 FET3-GFP::KanMX strain.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available. This includes Mössbauer spectra showing the contribution of BPS in Fe-deficient cells (Figure S1) and an Oxyblot analysis of mitochondria isolated from WT cells grown under different Fe conditions (Figure S2). This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Ye H, Rouault TA. Human Iron-Sulfur Cluster Assembly, Cellular Iron Homeostasis, and Disease. Biochemistry. 2010;49:4945–4956. doi: 10.1021/bi1004798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lill R. Function and biogenesis of iron-sulphur proteins. Nature. 2009;460:831–838. doi: 10.1038/nature08301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaplan CD, Kaplan J. Iron Acquisition and Transcriptional Regulation. Chem Rev. 2009;109:4536–4552. doi: 10.1021/cr9001676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jacobs A. Low molecular weight intracellular iron transport compounds. Blood. 1977;50:433–439. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Casas C, Aldea M, Espinet C, Gallego C, Gil R, Herrero E. The AFT1 transcriptional factor is differentially required for expression of high-affinity iron uptake genes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast. 1997;13:621–637. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(19970615)13:7<621::AID-YEA121>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rutherford JC, Jaron S, Winge DR. Aft1p and Aft2p mediate iron-responsive gene expression in yeast through related promoter elements. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:27636–27643. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300076200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Philpott CC. Iron uptake in fungi: A system for every source. Bba-Mol Cell Res. 2006;1763:636–645. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2006.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davis-Kaplan SR, Ward DM, Shiflett SL, Kaplan J. Genome-wide Analysis of Iron-dependent Growth Reveals a Novel Yeast Gene Required for Vacuolar Acidification. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:4322–4329. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310680200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eide D, Daviskaplan S, Jordan I, Sipe D, Kaplan J. Regulation of Iron Uptake in Saccharomyces cerevisiae - the Ferrireductase and Fe(II) Transporter Are Regulated Independently. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:20774–20781. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.YamaguchiIwai Y, Stearman R, Dancis A, Klausner RD. Iron-regulated DNA binding by the AFT1 protein controls the iron regulon in yeast. Embo J. 1996;15:3377–3384. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Courel M, Lallet S, Camadro JM, Blaiseau PL. Direct activation of genes involved in intracellular iron use by the yeast iron-responsive transcription factor Aft2 without its paralog Aft1. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:6760–6771. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.15.6760-6771.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dancis A, Roman DG, Anderson GJ, Hinnebusch AG, Klausner RD. Ferric Reductase of Saccharomyces-Cerevisiae - Molecular Characterization, Role in Iron Uptake, and Transcriptional Control by Iron. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:3869–3873. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.9.3869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dix D, Bridgham J, Broderius M, Eide D. Characterization of the FET4 protein of yeast - Evidence for a direct role in the transport of iron. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:11770–11777. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.18.11770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Askwith C, Eide D, Vanho A, Bernard PS, Li LT, Daviskaplan S, Sipe DM, Kaplan J. The Fet3 Gene of Saccharomyces cerevisiae Encodes a Multicopper Oxidase Required for Ferrous Iron Uptake. Cell. 1994;76:403–410. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90346-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Desilva DM, Askwith CC, Eide D, Kaplan J. The Fet3 Gene-Product Required for High-Affinity Iron Transport in Yeast Is a Cell-Surface Ferroxidase. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:1098–1101. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.3.1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Puig S, Vergara SV, Thiele DJ. Cooperation of two mRNA-Binding proteins drives metabolic adaptation to iron deficiency. Cell Metab. 2008;7:555–564. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2008.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Askwith C, Eide D, Van Ho A, Bernard PS, Li L, Davis-Kaplan S, Sipe DM, Kaplan J. The FET3 gene of S. cerevisiae encodes a multicopper oxidase required for ferrous iron uptake. Cell. 1994;76:403–410. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90346-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen X-Z, Peng J-B, Cohen A, Nelson H, Nelson N, Hediger MA. Yeast SMF1 Mediates H+-coupled Iron Uptake with Concomitant Uncoupled Cation Currents. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:35089–35094. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.49.35089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hassett R, Dix DR, Eide DJ, Kosman DJ. The Fe(II) permease Fet4p functions as a low affinity copper transporter and supports normal copper trafficking in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochem J. 2000;351(Pt 2):477–484. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dix DR, Bridgham JT, Broderius MA, Byersdorfer CA, Eide DJ. The FET4 gene encodes the low affinity Fe(II) transport protein of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:26092–26099. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li L, Bagley D, Ward DA, Kaplan J. Yap5 is an iron-responsive transcriptional activator that regulates vacuolar iron storage in yeast. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:1326–1337. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01219-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li LT, Chen OS, Ward DM, Kaplan J. A yeast vacuolar membrane transporter CCC1 facilitates iron storage. Mol Biol Cell. 2001;12:206a–206a. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaplan CD, Kaplan J. Iron acquisition and transcriptional regulation. Chem Rev. 2009;109:4536–4552. doi: 10.1021/cr9001676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lindahl PA, Morales JG, Miao R, Holmes-Hampton G. Isolation of Saccharomyces cerevisiae Mitochondria for Mössbauer, EPR, and Electronic Absorption Spectroscopic Analyses. Method Enzymol. 2009;456:267–285. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(08)04415-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cockrell AL, Holmes-Hampton GP, McCormick SP, Chakrabarti M, Lindahl PA. Mössbauer and EPR Study of Iron in Vacuoles from Fermenting Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochemistry. 2011;50:10275–10283. doi: 10.1021/bi2014954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Holmes-Hampton GP, Miao R, Morales JG, Guo YS, Münck E, Lindahl PA. A Nonheme High-Spin Ferrous Pool in Mitochondria Isolated from Fermenting Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochemistry. 2010;49:4227–4234. doi: 10.1021/bi1001823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nishida K, Silver PA. Induction of Biogenic Magnetization and Redox Control by a Component of the Target of Rapamycin Complex 1 Signaling Pathway. PLoS Biol. 2012;10:e1001269. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Urbanowski JL, Piper RC. The iron transporter fth1p forms a complex with the Fet5 iron oxidase and resides on the vacuolar membrane. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:38061–38070. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.53.38061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Portnoy ME, Liu XF, Culotta VC. Saccharomyces cerevisiae expresses three functionally distinct homologues of the Nramp family of metal transporters. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:7893–7902. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.21.7893-7902.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li LT, Kaplan J. A mitochondrial-vacuolar signaling pathway in yeast that affects iron and copper metabolism. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:33653–33661. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403146200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mühlenhoff U, Stadler JA, Richhardt N, Seubert A, Eickhorst T, Schweyen RJ, Lill R, Wiesenberger G. A specific role of the yeast mitochondrial carriers Mrs3/4p in mitochondrial iron acquisition under iron-limiting conditions. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:40612–40620. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307847200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Froschauer EM, Schweyen RJ, Wiesenberger G. The yeast mitochondrial carrier proteins Mrs3p/Mrs4p mediate iron transport across the inner mitochondrial membrane. Bba-Biomembranes. 2009;1788:1044–1050. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2009.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Foury F, Roganti T. Deletion of the mitochondrial carrier genes MRS3 and MRS4 suppresses mitochondrial iron accumulation in a yeast frataxin-deficient strain. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:24475–24483. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111789200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jo WJ, Loguinov A, Chang M, Wintz H, Nislow C, Arkin AP, Giaever G, Vulpe CD. Identification of genes involved in the toxic response of Saccharomyces cerevisiae against iron and copper overload by parallel analysis of deletion mutants (vol 101, pg 140, 2008) Toxicol Sci. 2008;102:205–205. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfm226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kucej M, Foury F. Iron toxicity protection by truncated Ras2 GTPase in yeast strain lacking frataxin. Biochem Biophys Res Comm. 2003;310:986–991. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.09.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee A, Henras AK, Chanfreau G. Multiple RNA surveillance pathways limit aberrant expression of iron uptake mRNAs and prevent iron toxicity in S. cerevisiae. Mol Cell. 2005;19:39–51. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bleackley MR, Young BP, Loewen CJR, MacGillivray RTA. High density array screening to identify the genetic requirements for transition metal tolerance in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Metallomics. 2011;3:195–205. doi: 10.1039/c0mt00035c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Peiter E, Fischer M, Sidaway K, Roberts SK, Sanders D. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae Ca2+ channel Cch1pMid1p is essential for tolerance to cold stress and iron toxicity. Febs Lett. 2005;579:5697–5703. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.09.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lindahl PA, Holmes-Hampton GP. Biophysical probes of iron metabolism in cells and organelles. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2011;15:342–346. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2011.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jhurry ND, Chakrabarti M, McCormick SP, Holmes-Hampton GP, Lindahl PA. Biophysical investigation of the ironome of human jurkat cells and mitochondria. Biochemistry. 2012;51:5276–5284. doi: 10.1021/bi300382d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Holmes-Hampton GP, Chakrabarti M, Cockrell AL, McCormick SP, Abbott LC, Lindahl LS, Lindahl PA. Changing iron content of the mouse brain during development. Metallomics. 2012;4:761–770. doi: 10.1039/c2mt20086d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Felice MR, De Domenico I, Li LT, Ward DM, Bartok B, Musci G, Kaplan J. Post-transcriptional regulation of the yeast high affinity iron transport system. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:22181–22190. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M414663200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thomas BJ, Rothstein R. Elevated Recombination Rates in Transcriptionally Active DNA. Cell. 1989;56:619–630. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90584-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Garber Morales J, Holmes-Hampton GP, Miao R, Guo Y, Münck E, Lindahl PA. Biophysical characterization of iron in mitochondria isolated from respiring and fermenting yeast. Biochemistry. 2010;49:5436–5444. doi: 10.1021/bi100558z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Miao R, Martinho M, Morales JG, Kim H, Ellis EA, Lill R, Hendrich MP, Münck E, Lindahl PA. EPR and Mössbauer spectroscopy of intact mitochondria isolated from Yah1p-depleted Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochemistry. 2008;47:9888–9899. doi: 10.1021/bi801047q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Miao R, Holmes-Hampton GP, Lindahl PA. Biophysical Investigation of the Iron in Aft1-1(up) and Gal-YAH1 Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochemistry. 2011;50:2660–2671. doi: 10.1021/bi102015s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hudder BN, Morales JG, Stubna A, Münck E, Hendrich MP, Lindahl PA. Electron paramagnetic resonance and Mössbauer spectroscopy of intact mitochondria from respiring Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2007;12:1029–1053. doi: 10.1007/s00775-007-0275-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Aasa R, Albracht SPJ, Falk K-E, Lanne B, Vänngård T. EPR signals from cytochrome c oxidase. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Enzymology. 1976;422:260–272. doi: 10.1016/0005-2744(76)90137-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fee JA, Findling KL, Yoshida T, Hille R, Tarr GE, Hearshen DO, Dunham WR, Day EP, Kent TA, Münck E. Purification and characterization of the Rieske iron-sulfur protein from Thermus thermophilus. Evidence for a [2Fe-2S] cluster having non-cysteine ligands. J Biol Chem. 1984;259:124–133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stevens BJ. Variation in Number and Volume of Mitochondria in Yeast According to Growth-Conditions - Study Based on Serial Sectioning and Computer Graphics Reconstitution. Biologie Cellulaire. 1977;28:37–56. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yamaguchi-Iwai Y, Dancis A, Klausner RD. AFT1: a mediator of iron regulated transcriptional control in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. EMBO J. 1995;14:1231–1239. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07106.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Puig S, Askeland E, Thiele DJ. Coordinated remodeling of cellular metabolism during iron deficiency through targeted mRNA degradation. Cell. 2005;120:99–110. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.11.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chang EC, Kosman DJ. Intracellular Mn(II)-associated superoxide scavenging activity protects Cu, Zn superoxide dismutase-deficient Saccharomyces cerevisiae against dioxygen stress. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:12172–12178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.McNaughton RL, Reddi AR, Clement MHS, Sharma A, Barnese K, Rosenfeld L, Gralla EB, Valentine JS, Culotta VC, Hoffman BM. Probing in vivo Mn2+ speciation and oxidative stress resistance in yeast cells with electron-nuclear double resonance spectroscopy. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:15335–15339. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1009648107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.