Abstract

Work stress is endemic among direct care workers (DCWs) who serve people with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Social resources, such as work social support, and personal resources, such as an internal locus of control, may help DCWs perceive work overload and other work-related stressors as less threatening and galvanize them to cope more effectively to prevent burnout. However, little is known about what resources are effective for coping with what types of work stress. Thus, we examined how work stress and social and personal resources are associated with burnout for DCWs.

We conducted a survey of DCWs (n = 323) from five community-based organizations that provide residential, vocational, and personal care services for adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Participants completed a self-administered survey about their perceptions of work stress, work social support, locus of control, and burnout relative to their daily work routine. We conducted multiple regression analysis to test both the main and interaction effects of work stress and resources with respect to burnout.

Work stress, specifically work overload, limited participation decision-making, and client disability care was positively associated with burnout (p < .001). The association between work social support and burnout depended on the levels of work overload (p < .05), and the association between locus of control and burnout depended on the levels of work overload (p < .05) and participation in decision-making (p < .05). Whether work social support and locus of control make a difference depends on the kinds and the levels of work stressors.

The findings underscore the importance of strong work-based social support networks and stress management resources for DCWs.

Keywords: workforce issues, mental health, stress and coping, intellectual and developmental disability

Work Stress and Burnout among Direct Care Workers: Do Work Social Support and Locus of Control Make a Difference?

1. Introduction

Direct care workers (DCWs) have played a crucial role in maintaining the health and well-being of adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities (ID) in a variety of settings, such as nursing facilities, group residences, and home care. This has included caring for adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities (ID) by administering medication; assisting with hygiene, grooming, dressing, and oral health care; and managing challenging behaviors. DCWs also have supported their clients’ professional and social development through vocational training and by facilitating their inclusion in the community-at-large (Hatton, 1999). Stressors resulting from heavy workloads, client behavioral and health problems, and limited job autonomy have been shown to be prevalent in DCW work. Such stressors, if not managed appropriately, can contribute to burnout and diminish the effectiveness of care delivery (Hatton, 1999; Skirrow & Hatton, 2007).

Burnout is commonly recognized as exhaustion from and reduced interest in tasks or activities (Maslach, 1993). Various types of job-related stressors, such as work overload, role ambiguity, role conflict, limited job autonomy, and client demands have been shown to contribute to burnout (Devereux, Hastings, Noone, Firth, & Totsika, 2009b; Kowalski, et al., 2010; Peiro, Gonzalez-Roma, Tordera, & Manas, 2001; White, Edwards, & Townsend-White, 2006). The individual experiences stress and, without adequate resources for coping, may face strain, exhaustion, and attitudinal and behavioral changes indicative of burnout (Maslach, 1982).

Several studies have indicated that social resources, such as support from supervisors or colleagues, are associated with low levels of burnout among DCWs in the ID field (Devereux, Hastings, & Noone, 2009a; Devereux, et al., 2009b; Dyer & Quine, 1998; Innstrand, Espnes, & Mykletun, 2004; Skirrow & Hatton, 2007; Thomas & Rose, 2010). (See Devereux, et al. (2009b) for a review.) However, we know little about how work social support interacts with work stress to reduce burnout among DCWs in the ID field. We have identified two studies that involve interaction effects of work stress and work social support with this population in the United Kingdom, which yielded somewhat inconsistent results. Devereux et al. (2009b) found no significant interaction effects between perceived work demands and work social support in a study of 96 DCWs. However, Dyer et al. (1998) found significant interaction effects between work social support and some stressors (i.e., work overload), but not others (i.e., non-participation in decision-making) for 80 DCWs. Research on the role of personal resources, specifically locus of control orientation, for burnout with DCWs in the ID field is even more scant. A U.S. study of mental health professionals indicated that individuals with an internal locus of control were more likely to approach work stressors with a problem-solving, proactive focus, and adapt to problems, whereas those with an external locus of control were more likely to succumb to the effects of stress: A significant interaction between an internal locus of control and work stress was found (Koeske & Kirk, 1995). Similarly, an internal locus of control orientation has been demonstrated to reduce levels of work stress (e.g., work overload), which in turn mitigates burnout among German nurses (Schmitz, Neumann, & Oppermann, 2000). However, to our knowledge, no study has examined whether the association of locus of control and burnout is dependent on level of work stress among DCWs caring for adults with ID. Furthermore, most studies on burnout and resources for DCWs in the ID field have been conducted in Europe and have used relatively small samples. Appropriate resources needed to help reduce burnout for such workers may be specific to the types of work they do, as well as the work contexts. Further research is needed to examine the relationships among various types of work stress, social and personal resources, and burnout among DCWs caring for ID populations in other social and cultural contexts, such as in the United States.

Thus our aim was to examine what types of work stress are related to DCW burnout, and how social and personal resources, such as work social support and locus of control, contribute to lower burnout for DCWs caring for adults with ID in a large US Midwestern metropolitan area. Guided by a conceptual model (see Figure 1) inspired by the Ensel and Lin life stress models (1991, 2004), we addressed two research questions: (1) How are work stress and resources, such as locus of control and work social support, associated with burnout when we control for sociodemographic and work-related characteristics? (2) Is the association between resources and burnout dependent on the level of work stress, and if so, how? We examined the main effects of work stress and resources on burnout to address the first question and the interaction between resources and work stressors (specifically, work overload and low levels of participation in decision-making) on burnout to address the second.

Figure 1.

Study conceptual model

2. Method

2.1 Participants and Procedure

We surveyed 323 DCWs employed at five organizations that provide residential, vocational, and personal care services for adults with ID. We selected a purposeful sample of five ID community service organizations from five different locations in a large city. These organizations employed DCWs from a variety of racial and ethnic groups. Eligible survey participants were direct support professionals providing non-medical direct care services to adults with ID, were fluent in both written and spoken English, and were at least 18 years of age.

We distributed surveys in three ways: 1) in-person, where project staff were present on-site to answer questions while the survey was completed; 2) supervisor distribution, where participants mailed packets back to the project office in pre-stamped envelopes when complete; and 3) mailed, where participating organizations sent survey packets to staff at home, and participants then returned completed surveys back to the project office in pre-stamped envelopes when complete. Although we attempted to distribute surveys in person to maximize response rates, some participating organizations' situations did not allow for DCWs to complete the survey on site. In an effort to improve the response rate further, we distributed a second round of survey packets to the organizations with the lowest response rates. This improved the study response rate by 5% (American Association for Public Opinion Research, 2008). As expected, the in-person mode of survey packet distribution produced the highest survey completion response rate at 86%. Although the overall study response rate of 47% of all eligible DCWs was not ideal, it is consistent with similar studies of DCWs serving ID clients, with response rates ranging from 22% to 75% (Hatton & Emerson, 1995). We detected no significant differences in sociodemographic characteristics among the three distribution groups.

Two researchers entered and compared data to ensure accuracy. Participants submitting incomplete data received a follow-up phone call in order to complete the surveys. In instances of incomplete data, we employed line-by-line deletion.

Study participants were largely female (83%) (see Table 1). The racial/ethnic breakdown was 64% non-Hispanic African American, 19% non-Hispanic White, and 17% Hispanic and other. Sixty-seven percent of the participants had completed some college classes or other specialized training. The majority (53%) of the sample were 35 or older. Precisely half of the participants reported being married or in a stable relationship, and most (87%) indicated that they lived with others. A small majority (54%) noted that they had home-based caregiving responsibilities, indicating possible home caregiving stress. Overall, our study group is comparable to typical DCW population samples except for slightly higher education levels (Hatton & Emerson, 1995; Test, Flowers, Hewitt, & Solow, 2003). The mean organizational tenure, or time employed at a specific organization, was reported to be slightly less than five years (58 months), and a small percentage (14%) of DCWs served in a supervisory role.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics

| Variable | n | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Male | 51 | 17% | |

| Female | 243 | 83% | |

| Age | |||

| ≤ 34 years | 152 | 47% | |

| ≥ 35 years | 169 | 53% | |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| Non-Hispanic African American | 208 | 64% | |

| Non-Hispanic White | 60 | 19% | |

| Hispanic & other | 54 | 17% | |

| Education | |||

| High school degree/GED or < | 97 | 33% | |

| Partial college/specialized training or > | 197 | 67% | |

| Married/in stable relationship | |||

| Yes | 161 | 50% | |

| No | 161 | 50% | |

| Living alone | |||

| Yes | 41 | 13% | |

| No | 282 | 87% | |

| Home caregiving responsibilities | |||

| Yes | 173 | 54% | |

| No | 149 | 46% | |

| Organization | |||

| A | 100 | 31% | |

| B | 26 | 8% | |

| C | 52 | 16% | |

| D | 116 | 36% | |

| E | 29 | 9% | |

| Supervisory status | |||

| Yes | 45 | 14% | |

| No | 278 | 86% | |

| Mean | SD | |

|---|---|---|

| Organizational Tenure, months (mean) | 58.27 | 57.93 |

2.2 Materials

Burnout, work stress, and resources were measured using instruments validated in previous studies. Table 2 provides descriptive statistics, the number of scale items, sample items, and Cronbach's alphas for our study sample. In our cross-sectional survey, work stressors were measured for the past three months of work, resources over the past month, and burnout within the past week to be consistent with the temporal order of elements in our stress-process framework. More detailed information is provided in previous work (Gray-Stanley, et al., 2010).

Table 2.

Work Stress, Work Social Support, and Locus of Control: Descriptive Statistics

| Mean | SD | Number of Items | Instrument Range | Cronbach's alpha | Sample Items | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Work Stress (sum) | 64.07 | 15.66 | 26 | 26-130 | .87 | |

| Work overload | 13.55 | 5.47 | 6 | 6-30 | .83 | I am asked to do work without adequate resources to complete it. |

| Role ambiguity | 9.70 | 4.06 | 5 | 5-25 | .82 | I have clear, planned goals and objectives for my job. |

| Role conflict | 8.70 | 4.13 | 4 | 4-20 | .83 | Professionals make conflicting demands of me. |

| Participation decision-making | 11.91 | 4.03 | 4 | 4-20 | .77 | Do you have the opportunity to contribute to meetings on new work developments? |

| Client disability | 20.34 | 7.27 | 7 | 7-35 | .89 | Low levels of client mobility (i.e., walking, moving). |

| Work social support (sum) | 33.88 | 9.47 | 10 | 10-50 | .89 | |

| Supervisor support | 20.53 | 6.80 | 6 | 6-30 | .92 | Offer new ideas for solving job-related problems? |

| Coworker support | 13.22 | 4.87 | 4 | 4-20 | .93 | To what extent could you count on your co-workers to help you with a difficult task at work? |

| Locus of control | 7.03 | 4.53 | 8 | −16 to 16 | .67 | I am responsible for my failures. |

| Burnout-emotional exhaustion | 19.19 | 13.34 | 9 | 0-54 | .92 | I feel burned out from my work. |

Burnout

Burnout was measured with the nine-item emotional exhaustion subscale from the Maslach Burnout Inventory Human Services Survey shortened version (Maslach & Jackson, 1996). All items were assessed using a six-point Likert response scale, with higher ratings indicating higher levels of burnout (Maslach & Jackson, 1996). We chose this measure based on prior research that identified emotional exhaustion (i.e., feelings of being drained of one's resources and energies), as a dominant dimension of the concept of burnout (Kristensen, Borritz, Villadsen, & Christensen, 2005) among other dimensions such as depersonalization, (i.e., detached, negative responses in working with others), and lack of personal accomplishment, (i.e., limited feelings of achievement in people-related work)(Maslach, 1982; Maslach, Schaufeli, & Leiter, 2001).

Work stress

Five dimensions of work stress were assessed with a five-point Likert scale (Hester Adrian Research Centre, 1999): (1) work overload, the quantity of work and overload, where the worker doesn't perceive adequate resources to complete work duties (six items) (Caplan, 1971); (2) role ambiguity, lack of clarity about role expectations (five items) (Rizzo, House, & Lirtzman, 1970); (3) role conflict, conflicting work requirements from superiors (four items) (Rizzo, et al., 1970); (4) participation in decision-making, as an indicator of work-related authority (four items) (Vroom, 1960); and (5) client disability, or levels of client functioning, mobility, and intellectual abilities (seven items) (Hester Adrian Research Centre, 1999). Five work-stress subdimension variables were created by summing items in each dimension. Global work stress was measured by the sum of all the work-stress related items.

Work social support

We assessed work social support with 10 items on a five-point Likert scale (West & Savage, 1988). The scale was divided into two subscales of supervisory support (6 items) and coworker support (4 items). Supervisor support includes informational, instrumental, and appraisal support elements, such as encouragement to employees to put forward their best efforts. Coworker support includes informational, instrumental, and emotional support elements, such as the extent to which coworkers can back each other up with work duties. A global measure, consisting of a sum of all work social support items, was also developed.

Locus of control

Locus of control, ranging from external to internal control beliefs, was measured with a locus of control five-point Likert scale of eight items (Ross & Mirowsky, 1989). Higher scores represented more internal control.

3. Results

3.1 Analyses

Multiple regression analysis was conducted to examine whether stressors had positive and resources had negative relationships with burnout (i.e., main effects model) and also how the association between resources and burnout varied among workers, depending on their reported stress levels (i.e., moderation effects model) (Ensel & Lin, 1991; Ensel & Lin, 2004).

Intercorrelations were examined among the independent variables and covariates, as well as with the dependent variable. Based on this analysis as well as theoretical considerations, we included the following control variables in the model: age, race and ethnicity, gender, education, marital status and living arrangement, home caregiving responsibilities, supervisory status, and tenure with the organization. Four dummy variables representing the five organizations captured and controlled for organizational effects. There were too few clusters (i.e., organizations) in this study to use hierarchical linear modeling (Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002).

3.2 Main Effects Models: How Are Work Stress and Resources Associated with Burnout?

Work stress was positively associated with burnout for models using the global work stress measure as expected (see Table 3, Models 1 & 2). When all work stress subdimensions were simultaneously entered in the model (Model 3), work overload, client disability, and low decision-making participation had statistically significant associations with burnout. Role ambiguity and role conflict were not statistically significant.

Table 3.

Multiple Regression Analysis of Burnout: Main and Moderating Effect Models

|

Main Effects Models |

Moderating Effects Models |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Independent Variable | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | Model 7 | Model 8 |

| Work stress | 0.47a*** (0.04)b | 0.47*** (0.04) | ||||||

| Work overload | 0.61*** (0.14) | 1.98*** (0.45) | 1.58*** (0.39) | 1.65** (0.37) | 0.43 (0.23) | |||

| Role ambiguity | 0.08 (0.17) | |||||||

| Role conflict | 0.26 (0.19) | |||||||

| Participation decision-making | 0.65*** (0.19) | 1.57*** (0.38) | ||||||

| Client disability | 0.55*** (0.10) | |||||||

| Work social support | −0.07 (0.07) | −0.06 (0.08) | 0.22 (0.18) | −0.13 (0.08) | −0.22** (0.07) | |||

| Supervisor support | −0.04 (0.10) | 0.25 (0.26) | ||||||

| Coworker support | −0.11 (0.14) | 0.57 (0.37) | ||||||

| Locus of control | −0.04 (0.15) | −0.04 (0.15) | −0.06 (0.15) | −0.22 (0.16) | −0.22 (0.16) | −0.22 (0.16) | 0.68 (0.51) | −1.10** (0.42) |

| Work social support X work overload | −0.03** (0.01) | |||||||

| Supervisor support X work overload | −0.03* (0.02) | |||||||

| Coworker support X work overload | −0.06* (0.03) | |||||||

| Internal locus of control X work overload | 0.06* (0.03) | |||||||

| Internal locus of control X participation decision-making | −0.09* (0.04) | |||||||

| R2 | 0.40 | 0.40 | 0.42 | 0.26 | 0.26 | 0.26 | 0.21 | 0.26 |

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001.

Unstandardized regression coefficient

Standard error.

Control variables: age, race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic African American, Hispanic & other), gender, education, marital and household status, home caregiving responsibilities, organization, supervisory status, and organization tenure

Regarding resources’ main effects, work social support, the subdimensions of supervisor and coworker support, and locus of control were not significantly associated with lower levels of burnout in models which included the global measure of work stress (Models 1 & 2), or all the work stress subdimension measures (Model 3).

3.3 Moderating Effect Models: Association between Resources and Burnout Dependent on Work Stress Levels

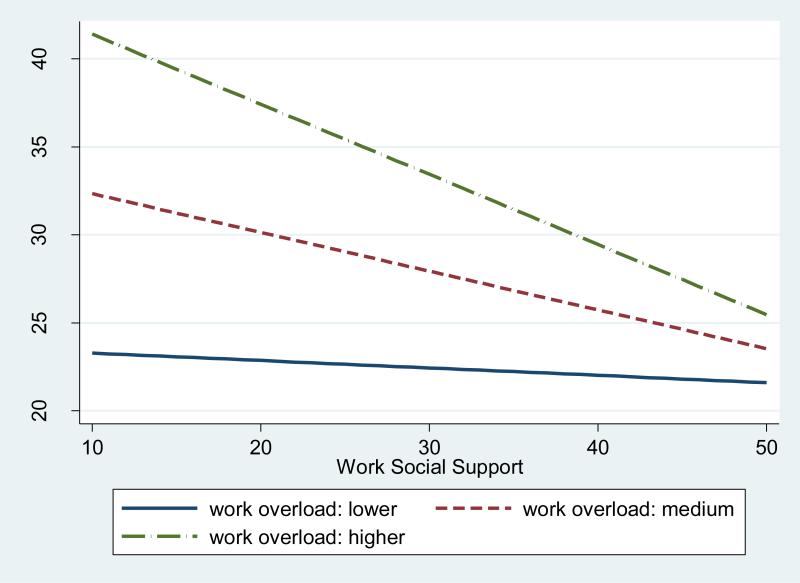

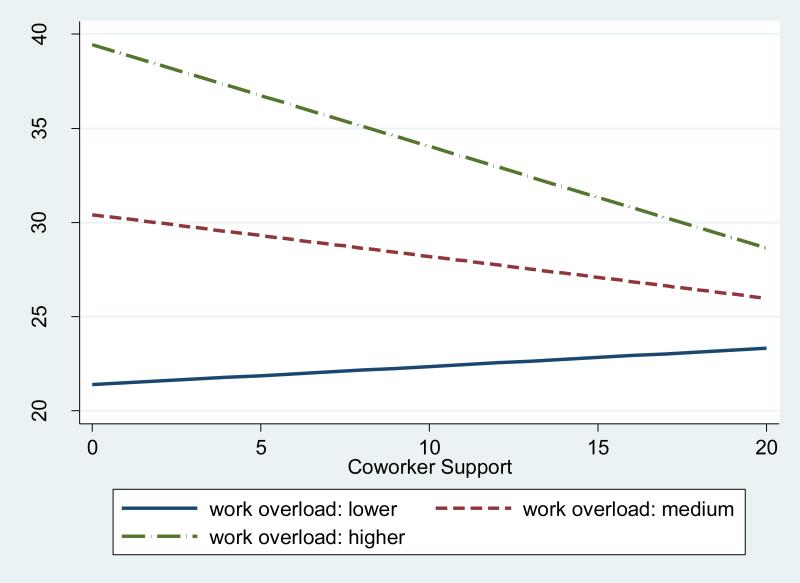

We tested the interaction effects of resources (i.e., work social support and locus of control) and the specific stressor subdimensions that were statistically significant in the main effects model (Model 3). Table 3 (Models 4-8) presents the results showing significant interaction effects, which are plotted in the associated figures (see Figures 2-6). We found significant interaction effects for work social support and locus of control with some subdimensions of work stress (Table 3, Models 4-8), which are visually presented in Figures 2 to 6. The interaction effects that involve client disability were not statistically significant (results not shown).

Figure 2.

Interaction between work social support and work overload for the outcome of burnout

The association between work social support (global) and burnout was statistically significant when work overload was at the medium (p < .01) and the high levels (mean + 1 SD, p < .001).

Figure 2 is based on Model 4.

Figure 6.

Interaction between locus of control and work overload for the outcome of burnout

The association between locus of control and burnout was statistically significant when work overload was at the low level (mean – 1 SD, p < .01).

Figure 6 is based on Model 8.

Figures 2 illustrates the association between the global measure of work social support and burnout for DCWs with high, middle, and low levels of work stress based on Model 4 (Table 3). As hypothesized, work social support showed the stronger inverse relationship with burnout (i.e., steeper negative slope) among workers perceiving heavier workloads. The inverse relationship between work social support and burnout was weaker (i.e., slope close to zero) and nonsignificant among workers perceiving lighter workloads. The results were similar for the subdimensions of work social support: supervisor and coworker support (Figures 3 and 4, which correspond to Models 5 and 6, respectively).

Figure 3.

Interaction between supervisor support and work overload for the outcome of burnout

The association between supervisor support and burnout was statistically significant when work overload was at the high level (mean + 1 SD, p < .001).

Figure 3 is based on Model 5.

Figure 4.

Interaction between coworker support and work overload for the outcome of burnout

The association between coworker support and burnout was statistically significant when work overload was at the high level (mean + 1 SD, p < .001).

Figure 4 is based on Model 6.

Per our expectations, the association between locus of control orientation and burnout depended on the levels of participation in decision-making (Model 7). Figure 5 shows this relationship. For workers who had limited participation in decision-making, possessing internal control beliefs lessened feelings of burnout, while external control beliefs contributed to it. The interaction effect was statistically significant when work stress (i.e., low decision-making participation) was at medium and higher levels.

Figure 5.

Interaction between locus of control and low decision-making participation for the outcome of burnout

The association between locus of control and burnout was statistically significant when decision-making participation was at the low level (mean + 1 SD, p < .05).

Figure 5 is based on Model 7.

Note: Decision-making participation appears as “decision-making partic” in the above figure.

The relationship between locus of control orientation and burnout also depended on the levels of work overload (Model 8). As shown in Figure 6, the association between locus of control and burnout was stronger among those who perceived lighter workloads. The inverse relationship between locus of control and burnout was weaker (i.e., slope close to zero) and insignificant among those with higher perceived workloads. This result was somewhat counterintuitive as we expected stronger locus of control effects for those perceiving heavier workloads.

4. Discussion

As far as we know, this is the first U.S. study with DCWs in the ID field which demonstrated that the association between coping resources (work social support and locus of control) and burnout depends on the kinds and levels of stress. Burnout was significantly associated with work stress, specifically the work stress subdimensions of work overload, low participation in decision-making, and client disability among DCWs.

While Dyer and Quine (1998) found main effects of work social support which were effective for both high and low stress levels, we found that work social support only made a difference for high stress levels. Our findings of a significant interaction effect between work overload and work social support was consistent with that in Dyer and Quine's (1998) study, which underscores the value of work social support for DCWs perceiving high levels of work overload. However, Devereux et al. (2009b) did not find such interaction effects between work social support and work demands. Differences in findings across studies could be due to differences in conceptualization and measurement of work stress, work social support, and burnout, as well as study samples and settings. For example, Devereux et al. (2009b) used a composite measure of work stressors, whereas we and Dyer and Quine (1998) measured separate subdimensions of work stress, conceptualized similarly with different measurement instruments. Dyer and Quine (1998) conceptualized work social support as staff perceptions of how work social support facilitated their job, whereas we and Devereux et al. (2009b) conceptualized work social support as staff perceptions of the presence, type, and satisfaction of supports available, using different measurement instruments. Authors of all three studies examined the emotional exhaustion dimension of burnout, but we and Devereux et al. (2009b) used the Maslach Burnout Inventory Human Services Survey, and Dyer and Quine (1998) designed a burnout instrument specifically for their study.

We also found that the association between locus of control orientation and burnout depended on the degree of participation in decision-making. Individuals possessing an internal locus of control are more likely to assume situational responsibility and employ problem-solving and other practical coping strategies to cope in positive ways (Koeske & Kirk, 1995) when feelings of exclusion or marginalization from the official organizational decision-making processes are experienced. This finding may be especially relevant for DCWs who work in semi-isolated community-based locations and yet lack adequate authority to make some expedient decisions in the field. Personal control beliefs (i.e., internal locus of control), but not work social support lessened the effects of low decision-making participation in this study. Similarly, Dyer and Quine (1998) did not find that work social support lessened the effects of non-participation in decision-making generally or for any particular stress level.

Locus of control effects depended on the levels of workloads, and was associated with less burnout for workers perceiving lower workload levels. While this finding may seem counterintuitive, it demonstrates the utility of internal control mechanisms at lower stress levels. As the perceived workload increases, other types of supports may be more effective. The fact that work social support was associated with lower burnout when workload levels were high, and locus of control lessened burnout when workload was low also suggests limits to internal control resources. An internal locus of control may not be sufficient to counter perceptions of a heavy workload, but work social support seemed to be valuable, as colleagues could provide emotional support, feedback, and other supports as needed.

Our relatively large sample (n = 323), compared to that of the Devereux et al. (2009b) (n = 96) and Dyer and Quine (1998) (n = 80) studies has allowed us to control for multiple potentially confounding factors. Certainly, with larger sample sizes, our coefficients for resources in the main effects models could have been statistically significant, which would have strengthened our findings. Moreover, our data were obtained through a purposeful sample, which was adequate for exploring interrelationships among the study concepts, but limited generalizability of the findings.

We made every effort to improve the response rate, such as by distributing a second round of survey packets to organizations with the lowest response rates. Thus our in-person survey packet distribution mode was 86%. However, some participating organizations did not allow for on-site survey completion, which contributed to our overall study response rate of 47%, similar to other studies of hard-to-reach DCWs caring for ID clients (Hatton & Emerson, 1995).

Furthermore, we can only determine associations, rather than causation, using cross sectional data. Though longitudinal data is needed to clarify possible causal relationships among work stress, resources, and burnout, we did include time parameters in the survey instrument. Work stressors were measured for the past three months of work, resources over the past month, and burnout within the past week.

Findings from this study can guide improvements in working conditions for DCWs. Building on our findings that work social support can help lessen burnout, it would be worthwhile to test different types of work social support across various work environments (i.e., residential versus vocational settings).

We found that possessing an internal locus of control orientation can be of value in the workplace. Though personal control traits usually do not change quickly (Schieman & Turner, 1998), training may help workers gradually develop stronger internal control beliefs and adopt active coping behaviors. Some researchers have suggested that specialty-specific interventions can teach workers to distinguish between types of situations that they can (e.g., assisting with client hygiene) or cannot control (e.g., aggressive client behaviors), and to develop on-the-job coping skills (Browning, Ryan, Thomas, Greenberg, & Rolniak, 2007).

Policies or interventions developed as a result of this analysis might include strategies to foster work-based social support networks (i.e., team building efforts), as well as interventions to help workers develop personal stress management resources (Tierney, Quinlan, & Hastings, 2007). Successful protocols, once identified, can contribute to improved DCW job morale and ultimately better client care.

Research highlights.

Work stress was positively associated with direct care worker (DCW) burnout.

The association between resources and burnout depended on work stress levels.

Work social support and stress management resources are critical for DCWs.

Acknowledgments

The research was supported by a Midwest Roybal Center for Health Maintenance, National Institutes of Aging pilot project grant (P30AG022849). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute on Aging or the National Institutes of Health. We are grateful for the support and assistance of our colleagues from the Center for Research on Health and Aging, Institute for Health Research and Policy. We are thankful to Tamar Heller, Susan Hughes, Timothy Johnson, and Jesus Ramirez-Valles, as well as Carolinda Douglass, Arlene Keddie, Jinsook Kim, Nancy LaCursia, Maribel Valle, and Marc Stanley for their comments on earlier versions of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

This manuscript is based on the first author's doctoral dissertation. An earlier version of this paper was presented at the 2009 Gerontological Society of America 62nd Annual Scientific Meeting.

Contributor Information

Jennifer A. Gray-Stanley, Department of Public Health and Health Education, School of Nursing and Health Studies, Northern Illinois University, 253 Wirtz Hall, DeKalb IL 60115

Naoko Muramatsu, Division of Community Health Sciences, School of Public Health, University of Illinois at Chicago, 1603 W. Taylor St., Chicago IL 60612, naoko@uic.edu.

References

- American Association for Public Opinion Research . Standard definitions: Final dispositions of case codes and outcome rates for surveys. AAPOR; Lenexa, Kansas: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Browning L, Ryan CS, Thomas S, Greenberg M, Rolniak S. Nursing specialty and burnout. Psychology, Health & Medicine. 2007;12(2):248–254. doi: 10.1080/13548500600568290. doi:10.1080/13548500600568290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caplan RD. Organizational stress and individual strain: A social psychological study of risk factors in coronary heart disease among administrators, engineers, and scientists. University of Michigan; Ann Arbor, Michigan: 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Devereux JM, Hastings RP, Noone S. Staff stress and burnout in intellectual disability services: Work stress theory and its application. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities. 2009a;22:561–573. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3148.2009.00509.x. [Google Scholar]

- Devereux JM, Hastings RP, Noone SJ, Firth A, Totsika V. Social support and coping as mediators or moderators of the impact of work stressors on burnout in intellectual disability support staff. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2009b;30(2):367–377. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2008.07.002. doi:10.1016/j.ridd.2008.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyer S, Quine L. Predictors of job satisfaction and burnout among the direct care staff of a community learning disability service. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities. 1998;11:320–332. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3148.1998.tb00040.x. [Google Scholar]

- Ensel WM, Lin N. The life stress paradigm and psychological distress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1991 Dec;32:321–341. doi:10.2307/2137101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ensel WM, Lin N. Physical fitness and the stress process. Journal of Community Psychology. 2004;32(1):81–101. doi:10.1002/jcop.10079. [Google Scholar]

- Gray-Stanley J, Muramatsu N, Heller T, Hughes S, Johnson TP, Ramirez-Valles J. Work stress and depression among direct support professionals serving adults aging with intellectual/developmental disabilities: The role of work support and locus of control. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 2010;54(8):749–761. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2010.01303.x. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2788.2010.01303.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatton C. Staff stress. In: Bouras N, editor. Psychiatric and behavioural disorders in developmental disabilities and mental retardation. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge, United Kingdom: 1999. pp. 427–438. [Google Scholar]

- Hatton C, Emerson E. The development of a shortened ’ways of coping’ questionnaire for use with direct care staff in learning disability services. Mental Handicap Research. 1995;8:237–251. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3148.1995.tb00160.x. [Google Scholar]

- Hester Adrian Research Centre . Survey on working in services for people with learning disabilities. Hester Adrian Research Centre; Manchester, UK: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Innstrand ST, Espnes GA, Mykletun R. Job stress, burnout, and job satisfaction: An intervention study for staff working with people with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities. 2004;17:119–126. doi:10.1111/j.1360-2322.2004.00189.x. [Google Scholar]

- Koeske, Kirk SA. Direct and buffering effects of internal locus of control among mental health professionals. Journal of Social Service Research. 1995;20(3/4):1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Kowalski C, Driller E, Ernstmann N, Alich S, Karbach U, Ommen O. Associations between emotional exhaustion, social capital, workload, and latitude in decision-making among professionals working with people with disabilities. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2010;31(2):470–479. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2009.10.021. doi:10.1016/j.ridd.2009.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kristensen TS, Borritz M, Villadsen E, Christensen KB. The Copenhagen Burnout Inventory: A new tool for the assessment of burnout. Work & Stress. 2005;19:192–207. doi:10.1080/02678370500297720. [Google Scholar]

- Maslach C. Burnout: The cost of caring. Prentice-Hall; Englewood Cliffs: NJ: 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Maslach C. Burnout: a multidimensional perspective. In: Schaufeli WB, Marek CT, editors. Professional burnout: Recent developments in theory and research. Taylor & Francis; Washington, D.C.: 1993. pp. 19–32. [Google Scholar]

- Maslach C, Jackson SE. Maslach Burnout Inventory: Human Services Survey. In: Maslach C, Jackson SE, editors. MBI Manual. 3rd ed. Consulting Psychologists Press, Inc.; Palo Alto, CA: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Maslach C, Schaufeli WB, Leiter MP. Job burnout. Annual Review of Psychology. 2001;52:397–422. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.397. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peiro JM, Gonzalez-Roma V, Tordera N, Manas MA. Does role stress predict burnout over time among health care professionals? Psychology and Health. 2001;16:511–525. doi: 10.1080/08870440108405524. doi:10.1080/08870440108405524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS. Hierarchical linear models: Applications and data analysis methods. 2nd ed. Sage; Newbury Park, CA: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Rizzo J, House RJ, Lirtzman SI. Role conflict and ambiguity in complex organizations. Administrative Science Quarterly. 1970;15:150–163. doi:10.2307/2391486. [Google Scholar]

- Ross CE, Mirowsky J. Explaining the social patterns of depression: Control and problem solving -- or support and talking? Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1989;30(June):206–219. doi:10.2307/2137014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schieman S, Turner HA. Age, disability, and sense of mastery. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1998;39:169–186. doi:10.2307/2676310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz N, Neumann W, Oppermann R. Stress, burnout and locus of control in German nurses. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2000;37(2):95–99. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7489(99)00069-3. doi:10.1016/S0020-7489(99)00069-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skirrow P, Hatton C. Burnout’ amongst direct care workers in services for adults with intellectual disabilities: A systematic review of research findings and initial normative data. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities. 2007;20(2):131–144. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3148.2006.00311.x. [Google Scholar]

- Test DW, Flowers C, Hewitt AS, Solow J. Statewide study of the direct support staff workforce. Mental Retardation. 2003;41(4):276–285. doi: 10.1352/0047-6765(2003)41<276:SSOTDS>2.0.CO;2. doi:10.1352/0047-6765(2003)41<276:SSOTDS>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas C, Rose J. The relationship between reciprocity and the emotional and behavioural responses of staff. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities. 2010;23:167–178. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3148.2009.00524.x. [Google Scholar]

- Tierney E, Quinlan D, Hastings RP. Impact of a three-day training course on challenging behaviour on staff cognitive and emotional responses. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities. 2007;20(1):58–63. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3148.2006.00340.x. [Google Scholar]

- Vroom VH. Some personality determinants of the effects of participation. Prentice Hall; Englewood Cliffs: 1960. [Google Scholar]

- West M, Savage Y. Coping with stress in health visiting. Health Visitor. 1988;61:366–368. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White P, Edwards N, Townsend-White C. Stress and burnout amongst professional carers of people with intellectual disability: another health inequity. Current Opinion in Psychiatry. 2006;19(5):502–507. doi: 10.1097/01.yco.0000238478.04400.e0. doi:10.1097/01.yco.0000238478.04400.e0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]