Abstract

Background

Fractional exhaled nitric oxide (FENO) is nitric oxide (NO) in the lower airway measured by oral exhalation. FENO can be a useful non-invasive marker for asthma. Paraquat-mediated lung injury can be reflective of an ROS-induced lung injury. We aimed to verify if FENO is a clinical parameter of ROS formation and responsiveness to medical therapies in acute paraquat intoxication.

Material/Methods

We recruited 12 patients admitted with acute paraquat poisoning. A portable and noninvasive device called NIOX MINO™ (Aerocrine AB, Solna, Sweden) was used to measure FENO. Measurements were made at the time of hospital admission and at 24, 48, 72, 96, and 120 h after paraquat ingestion.

Results

Six out of the total 12 recruited patients had general conditions (e.g. oral pain) that made it difficult for them to exhale with adequate force. Mean plasma paraquat level was 1.4±2.5 μg/mL. We found no direct correlation between the paraquat levels (both ingestion amount and plasma concentration) and FENO (initial, maximal, and minimal values). All the measured FENO values were no greater than 20 ppb for the 2 patients who died. FENO did not vary more than 20% from the baseline. Compared to the above findings, FENO measurements were found to be greater than 20 ppb for the patients who survived. FENO tends to reach its peak value at between 50 h and 80 h.

Conclusions

FENO did not predict mortality, and there was no increase of FENO in patients with severe paraquat intoxication.

MeSH Keywords: Oxidative Stress, Nitric Oxide, Paraquat - adverse effects, Paraquat - toxicity, Asthma - diagnosis

Background

Paraquat (1,1-dimethyl-4-4-bipyridium dichloride) is a very toxic herbicide that produces reactive oxygen species (ROS) in humans. Paraquat mainly accumulates in the lungs, where it is retained even when its concentration in blood decreases. Subsequent redox cycling and generation of ROS can trigger lung injury [1]. Oxidative stress has important implications for several events in lung physiology and the pathogenesis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma, interstitial lung disease, and acute respiratory distress syndrome [2,3].

Reactive nitrogen species (RNS) are a family of antimicrobial molecules derived from nitric oxide (•NO) and superoxide (O2•−) produced via the enzymatic activity of inducible nitric oxide synthase 2 (NOS2) and NADPH oxidase, respectively [4]. Reactive nitrogen species act together with ROS to damage cells, causing nitrosative stress.

Nitric oxide (NO) is an important signaling molecule reacting with superoxide derived from the paraquat redox cycle [5]. NO is involved in the mechanism of paraquat-mediated toxicity, although its role is controversial. It can either form the potent oxidant peroxynitrite, causing serious cell damages, or it can scavenge superoxide, providing protection from lung injury [5,6].

Fractional exhaled nitric oxide (FENO) is NO in the lower airway measured by oral exhalation.5 Previous studies have demonstrated that FENO can be a useful non-invasive marker for asthma, bronchiectasis, and upper respiratory infections [7–10]. In asthma, FENO measurement was able to evaluate responsiveness to both inhaled and systemic corticosteroids, and its values were found to be increased in central or peripheral airway inflammation. Interestingly, FENO values were observed to be reduced in cystic fibrosis patients [11].

Paraquat-mediated lung injury can be reflective of an ROS-induced lung injury [12–15]. Exhaled NO has never been investigated in acute paraquat poisoning. In this study, sequential measurements of FENO were made. We aimed to verify if FENO could a clinical parameter of ROS formation and responsiveness to medical therapies in acute paraquat intoxication.

Material and Methods

Patients

Twelve patients were recruited who were admitted with acute paraquat poisoning from November to December in 2012 to the Institute of Pesticide Poisoning of Soonchunhyang University Cheonan Hospital, Cheonan, Korea. The present study was approved by Soonchunhyang Cheonan Hospital’s Investigational Review Board. The patients went through the standardized medical management according to the treatment guidelines for paraquat intoxication used by Soonchunghyang University Cheonan Hospital. All the treatments were performed by our trained physicians. A brief summary of the treatment that the patients received as follows: Gastric lavage was performed on all patients who were checked 2 h or less after paraquat ingestion. If intoxication had occurred previously and less than 12 h after the ingestion, 100 g of Fuller’s earth in 200 ml of 20% mannitol was administered. Cyclophosphamide (15 mg/Kg) and methylprednisolone (1000 mg) were infused for three consecutive days. Antioxidant (N-acetylcysteine 4 g) was infused for 7 days. Hemoperfusion was performed when the result of a urinary paraquat test was positive.

Data collection

Demographic variables such as age and sex of the patients were recorded by the physicians on the standardized data collection form. Time difference between the patient’s paraquat exposure and hospital arrival at Soonchunhyang University Cheonan Hospital was recorded by looking up the patient history. Clinical laboratory parameters (white blood cell count, hemoglobin, hematocrit, amylase, lipase, albumin, aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase, total bilirubin, glucose, lactate dehydrogenase, blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, pH, and arterial oxygen concentration) were obtained at the patients’ arrival at the emergency unit. Values of arterial blood gas were recorded daily for 7 days while no oxygen supplement was being provided.

To assess the amount of paraquat exposure, paraquat level was measured by high-performance liquid chromatography with a Perkin Elmer Series 200 (Perkin Elmer, USA). In brief, PQ were separated on a reversed-phase column Capcell Pak C18 UG120 (150×4.6 mm i.d.; particle size, 5 μm; Shiseido Co., Tokyo, Japan), by isocratic elution with a mixture of methanol and 200 mM phosphoric acid solution containing both 0.1 M diethyl amine and 12 mM sodium 1-heptane sulfonate (1: 4, v/v) as the eluents [16].

FENO measurement

A portable and noninvasive device called NIOX MINO™ (Aerocrine AB, Solna, Sweden) was used to make FENO measurement. Sampling of breath was not necessary using this device. Subjects were asked to exhale into the device for 10 s, which led to the instant reading of FENO measurement. The measurement was made following the recommendations of the American Thoracic Society [17]. Times of the measurements were at the hospital admission and 24, 48, 72, 96, and 120 h after paraquat ingestion.

Statistics

The measurement values in this study were analyzed using statistics software (SPSS v14.0, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). Results yielding a p value less than 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

Results

To obtain a reliable FENO measurement, the patient was asked to blow into the measuring device with sufficient flow rate for a certain period of time. Six out of the total 12 recruited patients had general conditions (e.g. oral pain) that made it difficult for them to exhale with adequate force. As a result, only the 6 patients were considered for our study.

Table 1 shows the initial patient information recorded at hospital arrival. Mean ingested amount of paraquat (24.5% concentration) was 21.7±4.1mL (range of values: 5~170). Mean plasma paraquat level was 1.4±2.5 μg/mL (range of values: 0.23~6.51). There was no underlying pulmonary disease in any participants. Table 2 shows the baseline laboratory parameters.

Table 1.

Clinical findings and laboratory data of at admission.

| Age(yr) | 41.8±17.2 [20, 59] |

|

| |

| Sex | |

| Male | 3 |

| Female | 3 |

|

| |

| Estimated ingestion amount of paraquat (ml) | 21.7±4.1 |

|

| |

| Time from poisoning to hospital admission (hr) | 11.5±9.4 |

|

| |

| Serum paraquat level (μg/mL) | 1.4±2.5 [0.23, 6.51] |

|

| |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.0±0.4 |

|

| |

| Serum Alanine transaminase (IU/L) | 33.7±19.14 |

|

| |

| Total serum billirubin(mg/dL) | 0.6±0.1 |

|

| |

| Arterial blood gas analysis | |

|

| |

| pH | 7.42±0.04 |

|

| |

| PCO2 (mmHg) | 34.2±7.1 |

|

| |

| PO2 (mmHg) | 90.0±19.8 |

|

| |

| HCO3− (mEq/L) | 22.4±5.3 |

Table 2.

The baseline laboratory parameter in six patients.

| Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | Case 4 | Case 5 | Case 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White cell count | 18550 | 14480 | 10050 | 11530 | 11500 | 8020 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 13.8 | 13.3 | 15.1 | 15 | 14 | 14.7 |

| Hematocrit | 41.6 | 38.4 | 42.4 | 43.9 | 41.1 | 45.5 |

| Albumin (mg/dL) | 4.1 | 4.7 | 4.3 | 5.3 | 4.4 | 4.4 |

| Glucose (mg/dl) | 347 | 152 | 126 | 100 | 176 | 135 |

| Aspartate transaminase (IU/L) | 38 | 22 | 23 | 20 | 43 | 25 |

| Alanine transaminase (IU/L) | 54 | 21 | 19 | 12 | 57 | 39 |

| Lactate dehydrase (IU/L) | 229 | 216 | 205 | 208 | 234 | 207 |

| Urea nitrogen (mg/dL) | 5.1 | 9.7 | 14.8 | 24.2 | 17.9 | 6.4 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.7 | 0.7 | 1.1 | 1.7 | 0.8 | 0.8 |

| Amylase (IU/L) | 51 | 181 | 121 | 43 | 32 | 35 |

| Lipase (IU/L) | 13 | 13 | 17 | 25 | 30 | 26 |

| Sodium (mEq/L) | 134 | 141 | 135 | 136 | 144 | 146 |

| Chloride (mEq/L) | 98 | 102 | 98 | 92 | 107 | 107 |

| Potassium (mEq/L) | 3.9 | 3.2 | 3.7 | 3.8 | 4.4 | 4.8 |

| pH | 7.40 | 7.48 | 7.39 | 7.45 | 7.40 | 7.41 |

| PaCO2 (mmHg) | 22 | 32 | 36 | 42 | 33 | 40 |

| PaO2 (mmHg) | 85 | 107 | 121 | 70 | 81 | 76 |

| HCO3− (mEq/L) | 13.6 | 23.8 | 21.8 | 29.2 | 20.4 | 25.4 |

In Table 3, FENO measurements are presented along with other clinical measures such as paraquat ingestion amount, serum paraquat level, paraquat urine test, and initial PaO2. We found no direct correlation between the paraquat levels (ingestion amount and plasma concentration) and FENO (initial, maximal, and minimal values). Similarly, Pearson analysis revealed no direct correlation between FENO and PaO2.

Table 3.

Serial change of exhaled Nitric oxide in six patients.

| Case No | Sex | Age | Time from ingestion (hr) | Amout (ml) | PUT | Serum paraquat level (mg/ml) | Mortality (expire day) | Initial PaO2 | Initial eNO | 2nd day eNO | 3rd day eNO | 4th day eNO | 5th day eNO | 6th day eNO |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | F | 55 | 16 | 20 | ++++ | 1.22 | D(5) | 85 | 14 | 15 | 20 | 13 | ||

| 2 | F | 20 | 6 | 20 | + | 0.23 | S | 107 | 24 | 20 | 22 | |||

| 3 | M | 59 | 3 | 20 | ++++ | 6.51 | D(3) | 121 | 19 | 18 | ||||

| 4 | F | 21 | 28.5 | 30 | + | 0.13 | S | 70 | ND | 20 | 28 | 18 | 13 | |

| 5 | M | 44 | 7.75 | 20 | +++ | 0.27 | S | 81 | 18 | 20 | 31 | 33 | 32 | 28 |

| 6 | M | 52 | 7.75 | 20 | ++++ | 0.17 | S | 76 | 23 | 28 | 45 | 37 | 28 | 38 |

F – female; M – male; Amount – estimated amount of paraquat dichloride exposure (ml); PUT – semiquantative urinary paraquat test; −/±: trace; +: clear blue; ++: light blue; +++: dark blue; ++++: black; D – death; S – survival.

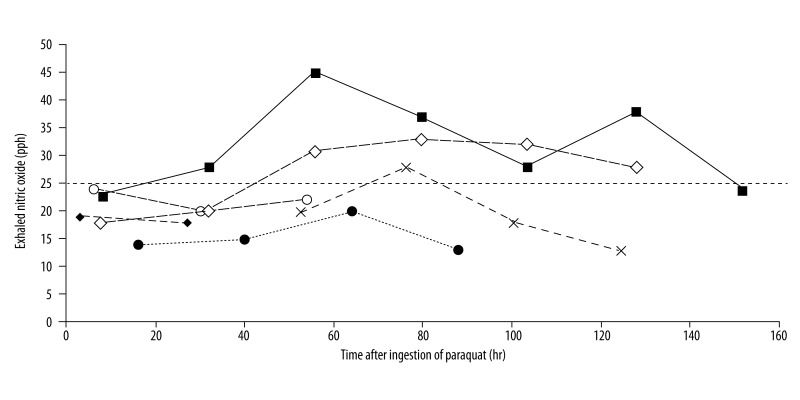

Interesting observations were made with respect to the levels and changes of the FENO values (Figure 1). All the measured FENO values were no greater than 20 ppb for the 2 patients who died. FENO did not vary more than 20% away from the baseline. Compared to the above findings, FENO measurements were greater than 20 ppb for the patients who survived. This was true for all the measurements except 1 case in which it was 18 ppb (Case no. 5 on Day 1). The patients seemed to have recovered when FENO was decreasing after having reached its peak. In Figure 1, changes in FENO are displayed on the time axis (hours). FENO tends to reach its peak value at between 50 h and 80 h after paraquat ingestion.

Figure 1.

Sequential variation of exhaled Nitric oxide in six patients. The horizontal dash line is indication of inflammation suggested by the American Thoracic Society. Two dead patients (case 1: ●, case 3: ◆) showed lower than 20 ppb of FENO. Case 1: ● (death), Case 2: ○ (survival), case 3: ◆ (death), case 4: × (survival) case 5: ◇ (survival), case 6: ■ (survival).

Discussion

Nitric oxide is the most extensively investigated exhaled marker of pulmonary diseases [7]. It is continuously generated in the lungs and the airways from amino acid L-arginine via constitutively active NO synthases (NOS) within the pulmonary vascular endothelium and the epithelial lining [18]. It has been suggested that endothelial cells constitutively express a relatively low output of NO pathway via type III NOS [18,19]. In contrast, airway epithelial cells express a relatively high output of NO pathway via type II NOS, which could be further induced by inflammatory mediators. Thiol-containing molecules chemically react with NO, hence they are a transient reservoir of NO [20,21]. With regard to ROS, it is known that NO assumes a double role. It can scavenge ROS (ie, superoxide), or it can produced peroxynitrate, inducing ROS injury [22–24]. Thus, the benefits of inhaling exogenous NO still remains controversial in paraquat intoxication.

For airway diseases (e.g. asthma) FENO is a useful marker, although its role remains to be clarified in lung parenchymal diseases and acute lung injuries [7,9]. Lung injury due to paraquat intoxication is well described to be lung damage induced via oxidative stress. FENO in paraquat-intoxicated patients may reflect ROS-induced lung injury. Our hypothesis is that FENO indicates the severity of lung injury or predict mortality. To our knowledge, this is the first study investigating FENO in paraquat poisoning. We anticipated that FENO would be useful in indicating ROS formation or responsiveness to medical therapies in acute paraquat intoxication.

The results in our study are striking, since FENO turned out to be no greater than 20 ppb for the 2 patients who died due to acute paraquat intoxication. On the contrary, FENO for the patients who survived were generally greater than 20 ppb. This was counter to our original expectation because FENO is commonly increased in most inflammatory airway diseases. The American Thoracic Society suggests the use of FENO levels greater than 25 ppb (>20 ppb in children) as an indication of inflammation [17].

Our paradoxical results could be explained by the following factors: 1) Inhibition of NO synthesis due to the abundant production of paraquat-induced inflammatory cytokines (e.g. IL-8) [25]. For example, in stable cystic fibrosis patients, FENO was significantly lower than in age-matched non-smoking healthy controls [9]. Levels of IL-8 in broncho-alveolar lavage samples from cystic fibrosis patients were higher than those in asthma or pulmonary infections. There also have been previous reports about oxidative stress, as in acute paraquat poisoning, resulting in overproduction of IL-8 in retinal pigment epithelial cells [25]. 2) Early consumption of NO in acute paraquat poisoning. In acute lung injury, ROS plays a significant role in disease progression. In our study, FENO values peaked after 48 h in 3 surviving subjects, and this may be due to FENO increase resulting from ROS production, by acute lung injury due to paraquat poisoning, or gradual recovery from the injury as a response to the medical treatments.

There are several limitations in our study. Only 6 subjects were studied. Two patients died within 5 days because the poisoning was very severe, explaining the missing data for these patients. Plasma paraquat concentration commonly peaks at around 2 h after ingestion and then declines thereafter. Our FENO measurements were not chronologically synchronized time with plasma paraquat checks, and this may have contributed to lack of correlation of the 2 variables. The source of NO was somewhat unclear in this study, since we could not measure it from bronchoalveolar lavage. Our previous study showed the change of lung cytoarchitecture in paraquat-intoxicated rats [26]. Inflammatory cell infiltration around the bronchiole was exhibited at 12 h after paraquat injection. Diffuse lung damage on the parenchyma and peribronchiole was observed at 72 h after paraquat injection. This pathology feature is different with asthma. Lastly, the effects on the measurements from medical therapies and the widely varying age of the subjects should be better clarified.

Conclusions

We conclude that FENO did not predict mortality in paraquat poisoning, and there was no increase of FENO in severely intoxicated patients. Our study shows that FENO was not directly correlated with paraquat levels or with PaO2. However, FENO level was not higher than the values indicative of inflammation for the patients who died due to acute paraquat poisoning. This was a pilot study in which a small group of patients was studied and the group size should be expanded to increase statistical power. Nonetheless, the current study presents interesting findings that are potentially useful in revealing the FENO level in paraquat poisoning patients. Further research with a larger group of subjects is highly suggested for comparing FENO measurements with oxidative stress parameters.

Footnotes

Statement of disclosures of conflict of interest

I have communicated with all of my co-authors and obtained their disclosures. My co-authors and I declare no conflicts of interest.

Source of support: This work was supported by the Soonchunhyang University Research Fund

References

- 1.Dinis-Oliveira RJ, Duarte JA, Sanchez-Navarro A, et al. Paraquat poisonings: mechanisms of lung toxicity, clinical features, and treatment. Crit Rev Toxicol. 2008;38:13–71. doi: 10.1080/10408440701669959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rosanna DP, Salvatore C. Reactive oxygen species, inflammation, and lung diseases. Curr Pharm Des. 2012;18:3889–900. doi: 10.2174/138161212802083716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Noor R, Mittal S, Iqbal J. Superoxide dismutase – applications and relevance to human diseases. Med Sci Monit. 2002;8(9):RA210–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Iovine NM, Pursnani S, Voldman A, et al. Reactive nitrogen species contribute to innate host defense against Campylobacter jejuni. Infect Immun. 2008;76:986–93. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01063-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moran JM, Ortiz-Ortiz MA, Ruiz-Mesa LM, et al. Nitric oxide in paraquat-mediated toxicity: A review. J Biochem Mol Toxicol. 2010;24:402–9. doi: 10.1002/jbt.20348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stefano GB, Kream RM. Reciprocal regulation of cellular nitric oxide formation by nitric oxide synthase and nitrite reductases. Med Sci Monit. 2011;17(10):RA221–26. doi: 10.12659/MSM.881972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barnes PJ, Dweik RA, Gelb AF, et al. Exhaled nitric oxide in pulmonary diseases: a comprehensive review. Chest. 2010;138:682–92. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-2090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ludviksdottir D, Diamant Z, Alving K, et al. Clinical aspects of using exhaled NO in asthma diagnosis and management. Clin Respir J. 2012;6:193–207. doi: 10.1111/crj.12001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Munakata M. Exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO) as a non-invasive marker of airway inflammation. Allergol Int. 2012;61:365–72. doi: 10.2332/allergolint.12-RAI-0461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Santamaria F, De Stefano S, Montella S, et al. Nasal nitric oxide assessment in primary ciliary dyskinesia using aspiration, exhalation, and humming. Med Sci Monit. 2008;14(2):CR80–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hofer M, Mueller L, Rechsteiner T, et al. Extended nitric oxide measurements in exhaled air of cystic fibrosis and healthy adults. Lung. 2009;187:307–13. doi: 10.1007/s00408-009-9160-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gil HW, Hong JR, Park JH, et al. Plasma surfactant D in patients following acute paraquat intoxication. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2007;45:463–67. doi: 10.1080/15563650701338138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gil HW, Seok SJ, Jeong DS, et al. Plasma level of malondialdehyde in the cases of acute paraquat intoxication. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2010;48:149–52. doi: 10.3109/15563650903468803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hong SY, Gil HW, Yang JO, et al. Clinical implications of the ethane in exhaled breath in patients with acute paraquat intoxication. Chest. 2005;128:1506–10. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.3.1506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Choi JS, Kwak KA, Park MJ, et al. Ratio of angiopoietin-2 to angiopoietin-1 predicts mortality in acute lung injury induced by paraquat. Med Sci Monit. 2014;20:28–33. doi: 10.12659/MSM.883730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zou Y, Shi Y, Bai Y, et al. An improved approach for extraction and high-performance liquid chromatography analysis of paraquat in human plasma. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2011;879(20):1809–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2011.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dweik RA, Boggs PB, Erzurum SC, et al. An official ATS clinical practice guideline: interpretation of exhaled nitric oxide levels (FENO) for clinical applications. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;184:602–15. doi: 10.1164/rccm.9120-11ST. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Asano K, Chee CB, Gaston B, et al. Constitutive and inducible nitric oxide synthase gene expression, regulation, and activity in human lung epithelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:10089–93. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.21.10089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guo FH, De Raeve HR, Rice TW, et al. Continuous nitric oxide synthesis by inducible nitric oxide synthase in normal human airway epithelium in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:7809–13. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.17.7809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sheu FS, Zhu W, Fung PC. Direct observation of trapping and release of nitric oxide by glutathione and cysteine with electron paramagnetic resonance spectroscopy. Biophys J. 2000;78:1216–26. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76679-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stamler JS, Simon DI, Osborne JA, et al. S-nitrosylation of proteins with nitric oxide: synthesis and characterization of biologically active compounds. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:444–48. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.1.444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Beckman JS, Beckman TW, Chen J, et al. Apparent hydroxyl radical production by peroxynitrite: implications for endothelial injury from nitric oxide and superoxide. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:1620–24. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.4.1620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Freeman BA, Gutierrez H, Rubbo H. Nitric oxide: a central regulatory species in pulmonary oxidant reactions. Am J Physiol. 1995;268:L697–98. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1995.268.5.L697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bloodsworth A, O’Donnell VB, Freeman BA. Nitric oxide regulation of free radical- and enzyme-mediated lipid and lipoprotein oxidation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2000;20:1707–15. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.20.7.1707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fernandes AF, Zhou J, Zhang X, et al. Oxidative inactivation of the proteasome in retinal pigment epithelial cells. A potential link between oxidative stress and up-regulation of interleukin-8. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:20745–53. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800268200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gil HW, Oh MH, Woo KM, et al. Relationship between pulmonary surfactant protein and lipid peroxidation in lung injury due to paraquat intoxication in rats. Korean J Intern Med. 2007;22:67–72. doi: 10.3904/kjim.2007.22.2.67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]