Abstract

Purpose: Targeted radiotherapy (TRT) is an emerging approach for tumor treatment. Previously, 3PRGD2 (a dimeric RGD peptide with 3 PEG4 linkers) has been demonstrated to be of advantage for integrin αvβ3 targeting. Given the promising results of 99mTc-3PRGD2 for lung cancer detection in human beings, we are encouraged to investigate the radiotherapeutic efficacy of radiolabeled 3PRGD2. The goal of this study was to investigate and optimize the integrin αvβ3 mediated therapeutic effect of 177Lu-3PRGD2 in the animal model.

Experimental Design: Biodistribution, gamma imaging and maximum tolerated dose (MTD) studies of 177Lu-3PRGD2 were performed. The targeted radiotherapy (TRT) with single dose and repeated doses as well as the combined therapy of TRT and the anti-angiogenic therapy (AAT) with Endostar were conducted in U87MG tumor model. The hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining and immunochemistry (IHC) were performed post-treatment to evaluate the therapeutic effect.

Results: The U87MG tumor uptake of 177Lu-3PRGD2 was relatively high (6.03 ± 0.65 %ID/g, 4.62 ± 1.44 %ID/g, 3.55 ± 1.08 %ID/g, and 1.22 ± 0.18 %ID/g at 1 h, 4 h, 24 h, and 72 h postinjection, respectively), and the gamma imaging could visualize the tumors clearly. The MTD of 177Lu-3PRGD2 in nude mice (>111 MBq) was twice to that of 90Y-3PRGD2 (55.5 MBq). U87MG tumor growth was significantly delayed by 177Lu-3PRGD2 TRT. Significantly increased anti-tumor effects were observed in the two doses or combined treatment groups.

Conclusion: The two-dose TRT and combined therapy with Endostar potently enhanced the tumor growth inhibition, but the former does not need to inject daily for weeks, avoiding a lot of unnecessary inconvenience and suffering for patients, which could potentially be rapidly translated into clinical practice in the future.

Keywords: Integrin αvβ3, Arg-Gly-Asp (RGD), 177Lu, radionuclide therapy, combination therapy.

Introduction

Radiotherapy is a very important tool in the fight against cancer and is used in the treatment of as many as 50% of all cancer patients 1-3. Compared with the conventional radiotherapy, the targeted radiotherapy (TRT) is an emerging approach for tumor treatment, which delivers the radiation in a targeted manner by a ligand that specifically binds to receptors overexpressed on the surface of some cancerous cells, thus providing good efficacy and tolerability outcomes 4-7.

Integrin αvβ3 is highly expressed on some tumor cells and new-born vessels, but is absent in resting vessels and most normal organ systems, making it a very attractive target for both tumor cell and tumor vasculature targeted imaging and therapy 8-10. Integrin αvβ3 has been proven to specifically recognize Arg-Gly-Asp (RGD) tripeptide sequence. In the last 20 years, a series of RGD peptide-based probes have been intensively developed for multimodality molecular imaging of integrin αvβ3-positive tumors 11-15. However, the RGD-based targeted radionuclide therapy is typically rare. Janssen ML et al. reported, for the first time, the integrin αvβ3 targeted radionuclide therapy with 90Y-labeled dimeric RGD peptide E[c(RGDfK)]2 in the NIH:OVCAR-3 subcutaneous (s.c.) ovarian carcinoma-bearing nude mouse model. A single injection of 37 MBq of 90Y-DOTA-E[c(RGDfK)]2 caused a significant tumor growth delay in treatment group as compared with the untreated control group 16.

Since a promising TRT relies on the maximized radiation accumulation and retention in tumors while minimizing the exposure of radiolabeled agents to normal tissues, many attempts, including multivalency and PEGlaytion, have been made to pursue more ideal RGD probes with high tumor targeting capability 17-19. We have combined both multivalency and PEGlaytion concepts together and developed a series of new RGD dimers with PEG4 and Gly3 linkers (e.g. 3PRGD2, a dimeric RGD peptide with 3 PEG4 linkers, see Fig 1) 20-24. The previous result showed that the 3PRGD2 conjugate (DOTA-3PRGD2, IC50 = 1.25 ± 0.16 nM) had higher binding affinity to integrin αvβ3 than the RGD monomer (c(RGDyK), IC50 = 49.89 ± 3.63 nM) and RGD dimer conjugates (DOTA-RGD2, IC50 = 8.02 ± 1.94 nM). The radiolabeled 3PRGD2 resulted in a high tumor uptake and improved in vivo pharmacokinetics as compared with those conventional RGD multimers, including RGD dimer (RGD2) and tetramer (RGD4), which simply utilized the multivalency concept to increase the tumor uptake 15, 17-21, 24. Furthermore, kit-formulated 99mTc-3PRGD2 has been successfully applied in clinic for characterization of malignant solitary pulmonary nodules (SPNs) 25, identification of differentiated thyroid cancer (DTC) patients with radioactive iodine-refractory (RAIR) lesions 26, and detection of lung cancer 27. Given the promising results of 99mTc-3PRGD2 for imaging in clinic, we were encouraged to further investigate the radiotherapeutic efficacy of radiolabeled 3PRGD2. In our previous research, 90Y-3PRGD2 showed comparable tumor growth inhibition but significantly lower toxicity as the lower accumulation in normal organs in comparison of 90Y-RGD4 24, indicating that the TRT of radiolabeled 3PRGD2 merits further investigation to achieve the better radiotherapeutic efficacy.

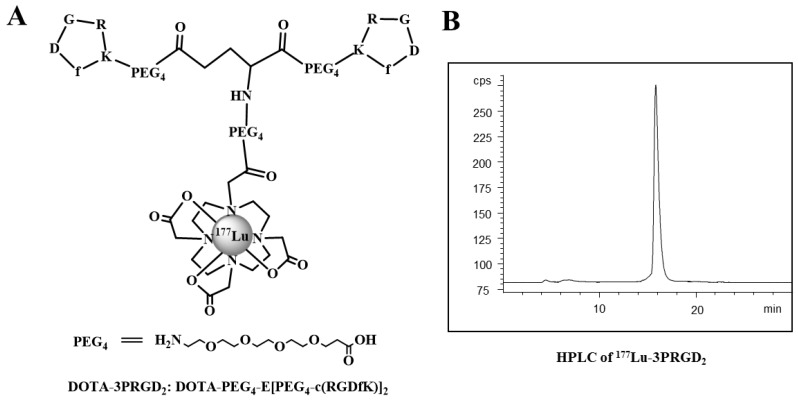

Figure 1.

The chemical structure (A) and HPLC chromatography (B) of 177Lu-3PRGD2.

177Lu, with longer half-life of 6.7 days and relatively mild β--emission (Emax: 0.497 MeV), offers the advantages to achieve higher injected dose amount and longer retention of radiation in tumors but lower irradiation of normal tissues adjacent to the tumors as compared with 90Y (half-life: 2.67 d, Emax: 2.28 MeV). Moreover, the γ-emission of 177Lu enables its use for the imaging and dosimetry assessment of patients before and during treatment without requiring a surrogate tracer. In this study, 177Lu radiolabeled 3PRGD2 was first investigated in terms of Glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) targeting capability and imaging feasibility, and was then examined in a therapeutic efficacy study on single dose as well as two-dose regimen TRT in a GBM animal model.

Angiogenesis is a key early event in tumor progression and metastasis. The inhibition of tumor growth by anti-angiogenic drugs has been achieved both in preclinical studies and in clinical trials, where promising anti-tumor responses have been reported for a variety of anti-angiogenic agents 28. Endostar, a novel recombinant human endostatin, which was approved by the China Food and Drug Administration (CFDA) in 2005 for clinical applications, showed strong growth inhibition of a variety of murine and xenotransplanted human tumors by suppressing neovascularization 29-31. The combination of radiotherapy and chemotherapy is an appealing approach that has led to improved treatment results in patients with advanced solid tumors 32-35. Herein, the combination therapy employing 177Lu-3PRGD2 TRT and Endostar anti-angiogenic therapy (AAT) was utilized to treat U87MG glioblastoma in a mouse model. Our aim was to optimize the therapeutic effect of radiolabeled 3PRGD2 for TRT of integrin αvβ3-positive tumors.

Materials and Methods

Materials

All commercially available chemical reagents were of analytical grade and used without further purification. See the supplemental material for the details.

Preparation of 177Lu-3PRGD2

The 3PRGD2 peptide was conjugated with chelator DOTA using previously described method 15. For 177Lu radiolabeling, 3700 MBq of 177Lu was diluted in 100 μL 0.4 M sodium acetate buffer (pH 5.0), and added to 50 μg DOTA-3PRGD2 conjugate (1 μg/μL in water) in a 1.5 mL eppendorf tube. The reaction tube was incubated in air bath for 10 min at 100 °C, and the 177Lu labeled peptide was then purified by the Sep-Pak C-18 cartridge. The quality control (QC) of the tracer was carried out with radio-HPLC by the previously reported method 15. The purified product was dissolved in saline and passed through a 0.22 μm syringe filter for in vivo animal experiments.

Cell culture and animal model

U87MG human glioblastoma cells were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). U87MG tumor model was established by subcutaneous injection of 2×106 U87MG tumor cells into the right thighs. All animal experiments were performed in accordance with guidelines of Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Peking University. See the supplemental material for the detailed procedures.

Biodistribution studies

Female nude mice bearing U87MG xenografts (4 mice per group) were injected with 370 kBq of 177Lu-3PRGD2 via tail vein to evaluate the distribution in major organs. The mice were sacrificed at 1 h, 4 h, 24 h and 72 h postinjection (p.i.). Blood, heart, liver, spleen, kidney, brain, lung, intestine, muscle, bone and tumor were harvested, weighed, and measured for radioactivity in a γ-counter (Wallac 1470-002, Perkin-Elmer , Finland). A group of four U87MG tumor-bearing nude mice was co-injected with 350 μg of c(RGDyK) for blocking study, and the biodistribution was performed at 1 h p.i. using the same method. Another group of four U87MG tumor-bearing nude mice was injected with 370 kBq of 177Lu-3PRGD2 following with 3 days of intraperitoneal Endostar administration (8 mg/kg per day), then the biodistribution was performed at 72 h p.i. using the above method. Organ uptake was calculated as the percentage of injected dose per gram of tissue (%ID/g). Values were expressed as mean ± SD (n = 4/group).

Gamma imaging

For the planar γ-imaging, the U87MG tumor-bearing nude mice were anesthetized with an intraperitoneal injection of sodium pentobarbital at a dose of 45.0 mg/kg. Each animal was administered with ~74 MBq of 177Lu-3PRGD2 in 0.2 mL of saline (n = 3 per group). Animals were placed on a two-head γ-camera (GE Infinia Hawkeye) equipped with a parallel-hole, low-energy, and high-resolution collimator. Images were acquired at 4 h and 24 h p.i., and stored digitally in a 128×128 matrix. The acquisition count limits were set at 500 k counts.

Maximum tolerated dose studies

The maximum tolerated dose (MTD) of 177Lu-3PRGD2 in non-tumor-bearing female BALB/c nude mice was determined by intravenous injection of escalating activities of 177Lu-3PRGD2 (37, 74 and 111 MBq per mouse), respectively (n = 7 per group). Body weight and health status were determined twice weekly over 20 days. Peripheral blood was collected from the tail vein twice weekly and then tested in a blood analyzer for white blood cell (WBC), red blood cell (RBC), hemoglobin (HGB), platelet (PLT) and neutrophile granulocyte (GRN) counts, etc. The MTD was set below the dose that caused severe loss of body weight (>20% of original weight), or death of one or more animals of a dose group.

Targeted radiotherapy and combined therapy

To assess the therapeutic potential of 177Lu-3PRGD2, U87MG tumor-bearing nude mice with a tumor size of ~50 mm3 were randomly assigned to several groups (n = 9 mice per group). Control group was injected via tail vein with single dose injection of saline. For TRT, U87MG tumor mice were dosed intravenously with either a single injection of 0.2 mL of 177Lu-3PRGD2 (5.55 GBq/kg; 111.0 MBq/0.2 mL; peptide 1.5 μg) or 2 equal doses on day 0 and day 6 (cumulative dose, 111.0 MBq/0.2 mL×2; peptide 1.5 μg/injection).

For the combination of TRT and AAT, a single dose injection of 177Lu-3PRGD2 (111 MBq) on day 0 combined with once daily administration of Endostar (8 mg/kg peritumoral subcutaneous (s.c.) injection) for 2 weeks (day 0 - 13). Furthermore, a scheduled dose injection of 177Lu-3PRGD2 (111 MBq) on day 5 combined with pretreatment of once daily administration of Endostar (8 mg/kg s.c. injection) for 5 days, then the Endostar treatment was continued for a total of 2 weeks (day 0 - 13).

Tumor dimensions were measured twice weekly with digital calipers, and the tumor volume was calculated using the formula: volume = 1/2 (length ×width ×width) 36. To monitor potential toxicity, body weight was measured. Mice were euthanized when the tumor size exceeded the volume of 1,500 mm3 or the body weight lost >20% of original weight.

Histopathology and immunohistochemistry

Frozen U87MG tumor tissues were cryo-sectioned and evaluated by standard hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining and immunohistochemistry (IHC). See the supplemental material for the detailed procedures.

Statistical analysis

Quantitative data are expressed as means ± SD. Means were compared using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Student's t test. P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Preparation of 177Lu-3PRGD2

After radiolabeling and purification, the specific activity of 177Lu tracer was typically about 7.4-14.8 MBq/nmol (0.2-0.4 Ci/mmol), with radiochemical purity greater than 99.5% (labeling yield more than 95%) as determined by analytic radio-HPLC.

Tumor uptake of 177Lu-3PRGD2

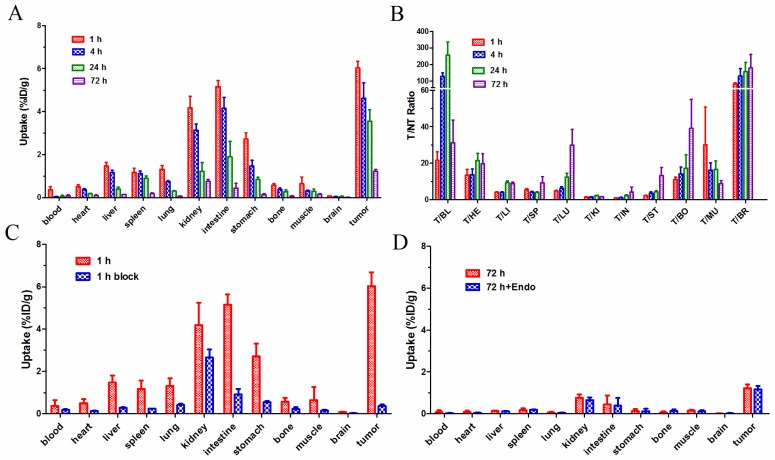

In biodistribution studies, the 177Lu-3PRGD2 depicted a similar biodistribution pattern with previously reported 111In-3PRGD2, which represents for 90Y-3PRGD2 24. As shown in Fig 2A, the uptake of 177Lu-3PRGD2 in U87MG tumors was 6.03 ± 0.65 %ID/g at 1 h p.i., which was decreased to 4.62 ± 1.44 %ID/g, 3.55 ± 1.08 %ID/g, and 1.22 ± 0.18 %ID/g at 4 h, 24 h, and 72 h p.i., respectively (n = 4/group). The %ID/g data are available as supplementary material (Table S1). 177Lu-3PRGD2 showed rapid blood clearance, and was cleared predominantly through both gastrointestinal and renal pathways as evidenced by relatively high intestine uptake (5.16 ± 0.48 %ID/g and 4.15 ± 1.12 %ID/g) and kidney uptake (4.18 ± 1.08 %ID/g and 3.13 ± 0.59 %ID/g) at 1 h and 4 h p.i., respectively. The tumor uptake of 177Lu-3PRGD2 was significantly inhibited by co-injection of the excess cold RGD peptide in blocking study (P <0.001, Fig 2C, Supplementary Material: Table S1), indicating the receptor-mediated targeting of 177Lu-3PRGD2 in integrin-positive U87MG tumors.

Figure 2.

(A) Biodistribution of 177Lu-3PRGD2 in U87MG tumor-bearing nude mice at 1 h, 4 h, 24 h, and 72 h after injection (370 kBq per mouse). (B) T/NT ratios of 177Lu-3PRGD2 in U87MG tumor-bearing nude mice at 1 h, 4 h, 24 h, and 72 h after injection (370 kBq per mouse). (C) Comparison of biodistribution of 177Lu-3PRGD2 with/without cold peptide blocking in U87MG tumor-bearing nude mice at 1 h after injection (370 kBq per mouse). (D) Comparison of biodistribution of 177Lu-3PRGD2 with/without Endostar treatment in U87MG tumor-bearing nude mice at 72 h after injection (370 kBq per mouse). Data are expressed as means ± SD (n = 4 per group).

The influence of anti-angiogenic therapy with Endostar on 177Lu-3PRGD2 tumor uptake was also determined. No difference on the tumor uptake was observed between the treatment and no-treatment groups (Fig 2D, P >0.5). The result may suggest that the 177Lu-3PRGD2 and Endostar do not bind to and work on the same receptor, although the binding mechanism of Endostar at the molecular level is unclear.

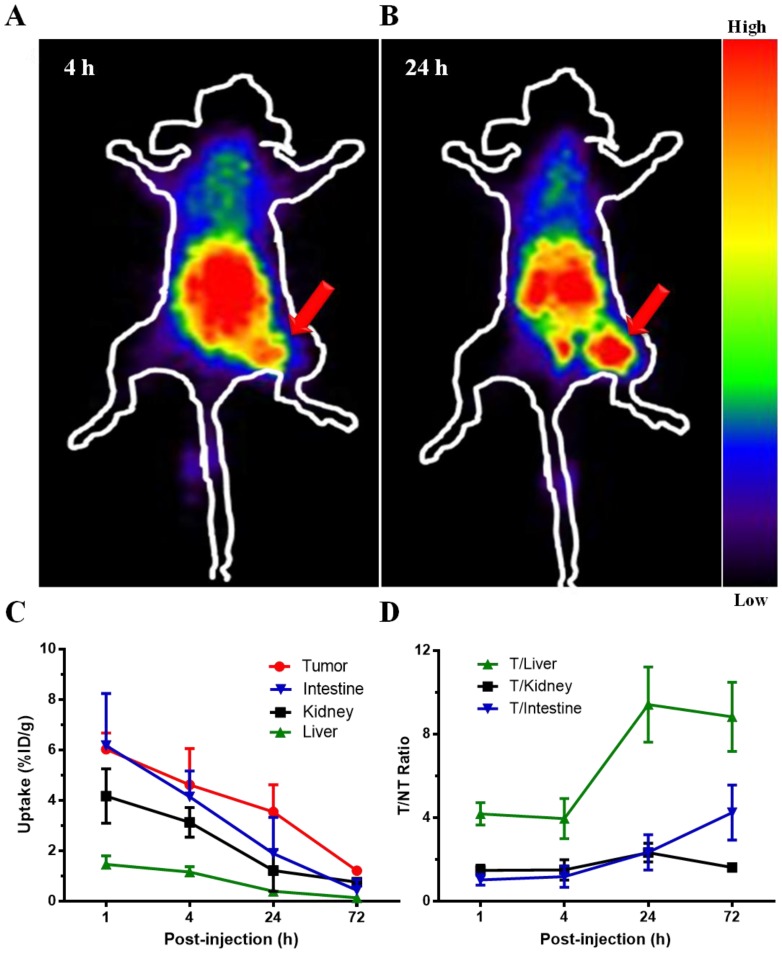

In planar γ-imaging study, the U87MG tumors receiving 177Lu-3PRGD2 were clearly visible at 4 h and 24 h p.i., with high contrast to the contralateral background (Fig 3A-B). Prominent gastrointestinal and renal uptake of this radiolabeled compound was also observed, suggesting both gastrointestinal and renal clearance of 177Lu-3PRGD2. Taken altogether, the imaging result was consistent with the biodistribution study.

Figure 3.

Representative planar gamma images of U87MG tumor-bearing nude mice at 4 h and 24 h after intravenous injection of ~74 MBq of 177Lu-3PRGD2. (n = 3 per group). Tumors are indicated by arrows.

Safety of 177Lu-3PRGD2

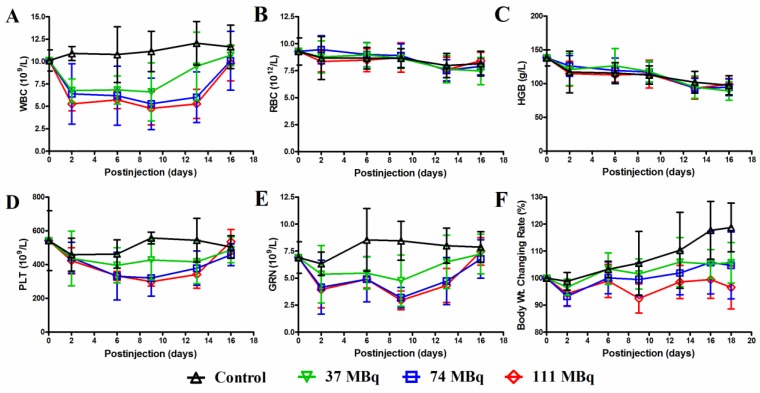

For the MTD determination, the animal body weight, WBC, RBC, HGB, PLA and GRN counts were analyzed after an escalating single injection dose of 177Lu-3PRGD2 Supplementary Material: Table S3, Fig 4. All those parameters showed a dose-dependent reduction. On day 9 p.i., these parameters reached the lowest level and then recovered to the baseline on day 16 p.i. (Fig 4). Overall, neither significant body weight loss (>20% of the original) nor mortality was observed in all groups. The highest dose (111 MBq) did not reach the MTD of 177Lu-3PRGD2 in mice.

Figure 4.

A MTD study was completed using escalating 177Lu-3PRGD2 doses of 0, 37, 74 and 111 MBq. Each dose was tested in seven female BALB/c nude mice. A hematology profile was measured twice-weekly, including (A) white blood cell (WBC), (B) red blood cell (RBC), (C) hemoglobin (HGB), (D) platelet (PLT), (E) neutrophile granulocyte (GRN). (F) Body weight was measured every other day.

Therapeutic efficacy of targeted radiotherapy and combined therapy

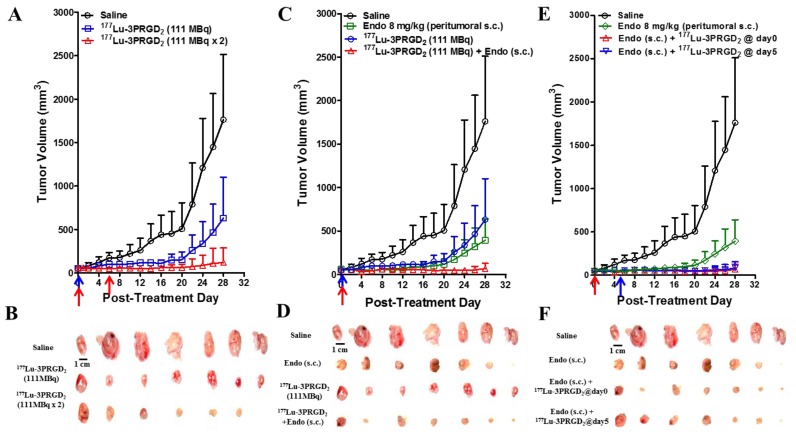

The therapeutic efficacy of 177Lu-3PRGD2 was investigated in integrin αvβ3-positive U87MG tumor-bearing nude mice. 177Lu-3PRGD2 possessed significant tumor inhibition effect as compared with the saline control group on day 28 post-treatment (P <0.005, Fig 5A-B). From day 6, the mice receiving the 2 × 111 MBq dose regimen of 177Lu-3PRGD2 exhibited the much better tumor growth inhibition as compared with the 111 MBq single dose (P <0.001 for day 6-14; P <0.01 for day 16-18; P <0.05 for day 20-26, Fig 5A).

Figure 5.

(A) Radionuclide therapy of established U87MG tumor in nude mice with saline (as control), 177Lu-3PRGD2 single dose (111 MBq), or 177Lu-3PRGD2 two doses (111 MBq × 2 on day 0 and day 6, respectively). (B) Tumor pictures of groups in (A) at the end of treatment. (C) Combination therapy of established U87MG tumors in nude mice with saline (as control), Endostar (8 mg/kg, peritumoral subcutaneous injection), 177Lu-3PRGD2 (111 MBq), or 177Lu-3PRGD2 (111 MBq) + Endostar (8 mg/kg, peritumoral subcutaneous injection). (D) Tumor pictures of groups in (C) at the end of treatment. (E) Combination therapy of established U87MG tumors in nude mice with saline (as control), Endostar (8 mg/kg, peritumoral subcutaneous injection), Endostar (8 mg/kg, (s.c.) peritumoral subcutaneous injection) + 177Lu-3PRGD2 (111 MBq day 0), or Endostar (8 mg/kg, peritumoral subcutaneous injection) + 177Lu-3PRGD2 (111 MBq day 5). (F) Tumor pictures of groups in (E) at the end of treatment. The time point of radioactivity administration was indicated by an arrow. Volume of tumors in each treatment group was measured and expressed as a function of time (means ± SD, n = 7 per group).

The Endostar AAT was performed via peritumoral s.c. injection and intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection. Only the group administrated via peritumoral s.c. injection exhibited significant tumor inhibition effect as compared with the saline control group (Fig 5C-F, Supplementary Material: Fig S1). The tumor inhibition was further promoted by combining the 177Lu-3PRGD2 TRT with Endostar AAT (peritumoral s.c. injection daily for two weeks), especially after day 18 (Fig 5C-D, P <0.05). No synergetic effect on tumor growth inhibition was observed when the 177Lu-3PRGD2 TRT combined with the Endostar AAT by i.p. injection Supplementary Material: Fig S1C-D, S2D). As shown in Fig 5E-F, pretreatment with Endostar (s.c.) for 5 days before 177Lu-3PRGD2 TRT didn't further improve the therapeutic efficacy, but exhibited a similar tumor inhibition effect as compared with the treatment group in which both 177Lu-3PRGD2 TRT and Endostar AAT were initiated on day 0 (Fig 5E-F).

A dose-dependent reduction of body weight was observed, but no significant body weight loss (>20% of the original) was observed in all treatment groups (Supplementary Material: Fig S4).

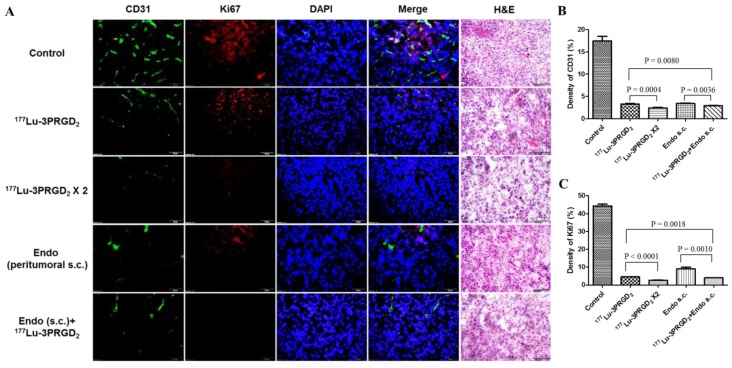

Immunofluorescence staining

CD31 and Ki67 immunofluorescence staining was performed to validate the therapeutic efficacy of 177Lu-3PRGD2 and Endostar treatment. Consistent with the therapy data, the tumor vasculature and Ki67 positive area in the 177Lu-3PRGD2 and Endostar treatment groups are much less than the control group, demonstrating the vasculature damage and the tumor cell proliferation inhibition of 177Lu-3PRGD2, as well as the neovascular growth inhibition of Endostar (Fig 6. Among the therapy groups, the repeated dose regimen and combination of 177Lu-3PRGD2 and Endostar (s.c.) showed the best therapeutic efficacy.

Figure 6.

A) CD31(green), Ki67(red), DAPI(blue) staining and Hematoxylin-Eosin (H&E) staining of the frozen U87MG tumor tissue slices at the end of treatment with saline (as control), 177Lu-3PRGD2 (111 MBq), 177Lu-3PRGD2 (111 MBq × 2), Endostar (8 mg/kg, peritumoral subcutaneous injection) and 177Lu-3PRGD2 (111 MBq) + Endostar (8 mg/kg, peritumoral subcutaneous injection). B) Density of CD31 was analyzed by Image J software, C) Density of Ki67 was analyzed by Image J software.

Discussion

The physical properties of 177Lu offer advantages compared to 90Y. 177Lu emits low energy γ-rays which directly allow quantitative determination of the biodistribution and dosimetry as well as the γ-imaging of the 177Lu-labeled tracers without using a radionuclide surrogate. In addition, 177Lu has shorter tissue penetration range (Rmax: 2 mm) and relatively mild β--emission (Emax: 0.497 MeV), which is favorable for treatment of small tumors and micrometastases, and offers the advantage of lower irradiation of normal tissues adjacent to the tumors 37, 38. Thus, 177Lu-labeled peptides are more suitable for high dose and multiple-dose regimens. Given the promising glioblastoma growth inhibition by the targeted 90Y-3PRGD2 radionuclide therapy in our previous study 24, 177Lu was employed in this study to introduce higher dose and multiple-dose regimens, which successfully improved the tumor inhibition efficacy.

Since the efficacy of TRT mainly depends on the specific accumulation of radiation in tumor, the tumor uptake and tumor-to-non-tumor (T/NT) ratios are crucial for a therapeutic agent. Here, we compared the biodistribution data of 177Lu-3PRGD2 with 111In-3PRGD2/111In-RGD4 (as the surrogates of 90Y-3PRGD2/90Y-RGD4). As 90Y is a pure β- nuclide, biodistribution and imaging for 90Y-labeled agents are usually estimated using 111In-labeled corresponding agents, which is biologically equivalent to 90Y-labeled agents 24. The tumor uptake of 177Lu-3PRGD2 at later time points (3.5 ± 1.1 %ID/g and 1.2 ± 0.2 %ID/g at 24 and 72 h p.i. respectively) was slightly higher than 111In-3PRGD2 (as the surrogate of 90Y-3PRGD2) (2.03 ± 0.24 %ID/g and 0.45 ± 0.05 %ID/g) and more comparable to 111In-RGD4 (as the surrogate of 90Y-RGD4) (3.67 ± 0.57 %ID/g and 1.72 ± 0.41 %ID/g), providing stronger and longer radiation treatment. Moreover, the uptake of 177Lu-3PRGD2 in normal organs, especially kidneys (4.2 ± 1.1 %ID/g and 3.1 ± 0.6 %ID/g at 1 h and 4 h p.i., respectively), was much lower than that of 111In-RGD4 (13.23 ± 1.22 %ID/g and 10.99 ± 0.88 %ID/g) 24, which resulted in much higher T/NT ratios and possibly much lower toxicity, indicating the desirable properties of this therapeutic agent (Fig 1A-B and Fig 2C-D). Thus, with the advantage of the relative long half-life (2.67 d) of 177Lu, the very high and potentially tumoricidal accumulated absorbed doses could be achieved.

Imaging and dosimetry before and during therapy are very valuable for the treatment planning and for the evaluation of the outcome. However, the dosimetric data on radiolabeled 3PRGD2 are still rare. For the first time, the human absorbed doses to normal organs for 177Lu-3PRGD2 were estimated from biodistribution data in U87MG tumor-bearing mice by using a dedicated software (OLINDA/EXM) (Table 2). It shows much lower whole body absorbed doses (0.014 ± 0.004 mSv/MBq) than 177Lu-DOTA-Y3-TATE (0.031 ± 0.007 mSv/MBq) 39, which has been currently using in clinic. The γ-imaging of 177Lu-3PRGD2 in U87MG tumors revealed high tumor uptake and fast clearance from liver, kidneys and intestine, which was consistent with the biodistribution data. With this imaging potential, the 177Lu-3PRGD2 could be not only used for TRT, but also used as imaging diagnosis agent for screening patients before personalized TRT and guiding the treatment 37, 38.

Table 2.

Human absorbed dose estimates of 177Lu-3PRGD2 obtained from U87MG tumor mice.

| Target Organ | Effective Dose (mSv/MBq) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | N | |

| Adrenals | 3.36E-06 | 3.08E-07 | 4 |

| Brain | 2.83E-06 | 5.24E-07 | 4 |

| Breasts | 1.29E-05 | 5.52E-06 | 4 |

| LLI Wall | 3.92E-05 | 3.00E-05 | 4 |

| Small Intestine | 3.34E-06 | 4.02E-06 | 4 |

| Stomach Wall | 2.11E-04 | 1.88E-04 | 4 |

| ULI Wall | 3.46E-06 | 3.25E-06 | 4 |

| Heart Wall | 7.75E-04 | 1.54E-04 | 4 |

| Kidneys | 7.39E-04 | 2.21E-04 | 4 |

| Liver | 7.77E-04 | 1.21E-04 | 4 |

| Lungs | 2.52E-03 | 4.58E-04 | 4 |

| Muscle | 2.20E-06 | 4.73E-07 | 4 |

| Pancreas | 4.18E-06 | 5.26E-07 | 4 |

| Red Marrow | 5.25E-05 | 1.08E-05 | 4 |

| Osteogenic Cells | 8.75E-05 | 3.10E-05 | 4 |

| Skin | 1.86E-06 | 7.74E-07 | 4 |

| Spleen | 5.81E-03 | 1.19E-03 | 4 |

| Thymus | 8.92E-07 | 3.52E-07 | 4 |

| Thyroid | 9.02E-06 | 4.49E-06 | 4 |

| Urinary Bladder Wall | 9.26E-06 | 7.49E-06 | 4 |

| Total Body | 1.35E-02 | 4.49E-03 | 4 |

Hematological parameters and body weight loss were used as the gross toxicity criteria in the MTD study. The mice exhibited much higher tolerance to 177Lu-3PRGD2 (>55.5 GBq/kg or 150 mCi/kg) as compared with 90Y-3PRGD2 (27.7 GBq/kg or 75 mCi/kg), which was most likely due to its relatively mild β--emission inducing less irradiation in normal organs, especially in the kidneys and liver. The higher MTD of 177Lu-3PRGD2 would allow higher single dose administration, and also possible treatment regimen of multiple doses.

Radiolabeled RGD peptides can specifically bind integrin αvβ3 expressed both on tumor cell surface and the new-born tumor vasculature 38, therefore, 177Lu-labeled RGD peptides are considered to specifically deliver radiotherapeutics to both the integrin αvβ3-expressing tumor cells and the tumor neovasculature, which may lead to better management of solid tumors. In our radionuclide therapy studies, partial tumor regression was successfully achieved by a single dose of 111 MBq 177Lu-3PRGD2, and the therapeutic effect of 177Lu-3PRGD2 was significantly better than that of control group (Fig 5A-B, S2A), while the tumor volume doubling time (TVDT) was 11 days and 3 days, respectively (Table 1). Due to the higher MTD and longer tumor radiation retention, 177Lu-3PRGD2 possessed more gratifying tumor regression effect as compared with 90Y-3PRGD2 at well-tolerated doses (TVDT: 11 days vs. 7 days, Table 1) 24. Yoshimoto M. et al. reported that multiple-dose administration (11.1 MBq × 3) of 90Y-DOTA-c(RGDfK) (RGD monomer) induced more significant inhibition of tumor growth than single dose injection (TVDT: 12 days vs. 10 days) 40. Considering the less toxicity of 177Lu-3PRGD2, the higher or multiple-dose injection of 177Lu-3PRGD2 is speculated to be more effective for tumor therapy. We also investigated the repeated dose administration of 177Lu-3PRGD2 in U87MG tumor model, and the second dose was administrated on day 6 with the interval as one half-life of 177Lu. Two cycles of 177Lu-3PRGD2 administration significantly increased the anti-tumor effect as compared with the single dose (TVDT: 28 days vs. 11 days), which is more pronounced compared with (11.1 MBq × 3) of 90Y-DOTA-c(RGDfK) (TVDT: 28 days vs.12 days), even remarkably cured one tumor among 7 tumors (Fig 5A-B, S2A, Table 1). Since the single dose TRT showed notable tumor regression until day 20, the two dose regimen might be optimized by extending dosing interval to 20 days to get prolonged therapy efficacy. It could be further improved by introducing more repeated doses in the multiple dose regimen as well. The vasculature destruction and tumor cell proliferation inhibition of 177Lu-3PRGD2 TRT resulted in the reduced tumor vasculature and tumor growth inhibition, which were confirmed by CD31 and Ki67 staining. Both CD31+ vascular endothelial cells and Ki67 positive areas showed significant reduction, suggesting 177Lu-3PRGD2 treatment induced vasculature collapse and tumor regression (Fig 6). These findings were also confirmed by H&E staining results, which showed more structural damages in tumor tissue of the TRT treatment group (Fig 6).

Table 1.

Tumor volume doubling time of all experimental groups in therapy studies.

| Experimental groups | Tumor volume doubling time (days) |

|---|---|

| Control | 3 |

| Cold peptide(~5 μg @ day 0)* | 3 |

| 177Lu-3PRGD2 (111 MBq @ day 0) | 11 |

| 177Lu-3PRGD2 (111 MBq × 2 @ day 0 and day 6) | 28 |

| Endostar treatment (i.p. 8 mg/kg/day for two weeks)# | 5 |

| 177Lu-3PRGD2 + Endostar (i.p.)# | 15 |

| Endostar treatment (peritumoral s.c.) | 21 |

| 177Lu-3PRGD2 + Endostar (peritumoral s.c.) | >28 |

| 90Y-3PRGD2 (37 MBq @ day 0)* | 7 |

| 90Y-3PRGK2 (37 MBq @ day 0)* | 4 |

| 90Y-RGD4 (37 MBq @ day 0)* | 6 |

| 90Y-RGD4 (18.5 MBq @ day 0)* | 3 |

| 90Y-RGD4 (18.5 MBq × 2 @ day 0 and day 6)* | 5 |

Note:

#: data showed in supplementary material (Fig S1-2).

*: data from previous paper 24. The 3PRGK2 is a nonsense counterpart of 3PRGD2.

Endostar treatment was administrated at 8 mg/kg daily for two weeks via either i.p. or peritumoral s.c. route.

All the single dose of 177Lu-3PRGD2 (111 MBq) in combination therapy was administrated on day 0.

Endostar, as an endogenous inhibitor of angiogenesis, has been verified to combine with standard chemotherapy or radiation therapy regimens to improve the tumor regression 30, 31, 41. Zhou J. et al. reported that combining Endostar with external beam radiotherapy successfully improved the inhibition of the NPC (Nasopharyngeal carcinoma) xenograft tumor growth and increased the sensitivity of tumor cells to radiation 30. In the current study, the cross-influence of Endostar injection to 177Lu-3PRGD2 tumor uptake was firstly evaluated. As a result, the tumor uptake was found non-affected during the Endostar treatment (Fig 2D). The results insured that 177Lu-3PRGD2 and Endostar could be used as a combination therapy. The tumor growth was significantly inhibited only by administrating Endostar via peritumoral s.c. injection, possibly due to the poor concentration of Endostar dose in U87MG tumor by systemic administration (TVDT: 21 days vs. 5 days) Supplementary Material: Fig S1, S2C-D, Table 1, which also has been proved by Schmidt group 28. Combination therapy of 177Lu-3PRGD2 TRT and Endostar (s.c.) futher improved the tumor regression, which was more notable starting from day 18 than the mono-therapy with 177Lu-3PRGD2 or Endostar (s.c.), and the TVDT was remarkably prolonged to more than 28 days (Fig 5C-D, S2B, Table 1; P <0.05). Also, the vasculature destruction and tumor cell proliferation inhibition of AAT and combination therapy were confirmed by CD31 and Ki67 staining, which showed significantly reduced CD31+ vascular endothelial cells and Ki67 positive areas, suggesting vasculature collapse and tumor regression (Fig 6). These findings were also confirmed by H&E staining results, which showed more structural damages in the tumor tissues of the combination treatment group.

Fang P. et al. 41 reported that Endostar could normalize the morphology and function of nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) vasculature for a period of time, leading to transient improvement in tumor oxygenation and response to radiation therapy. According to their findings, the normalization window was mostly during the first treatment 5-7 days, which was proved in the U87MG tumor model by performing tumor IHC analysis with CD31and NG-2 staining Supplementary Material: Fig S3). NG-2 antibody was used to label pericytes around vascular, since increased pericyte coverage was considered as a key characteristics of tumor vessel normalization (41. As shown in Supplementary Material: Fig S3, the NG-2 positive area was found significantly enhanced at Endostar (s.c.) treatment on day 5 - 7, compared to untreatment on day 0 and post-treatment day 14. However, the strategy that administrated Endostar 5 days in advance then combined with 117Lu-3PRGD2 induced no further therapeutic improvement, compared with that both Endostar and 117Lu-3PRGD2 were initiated at the day 0 (Fig 5E-F). More pretreatment studies with Endostar combined radiotherapy are still needed in the future to figure out if the normalization window theory would be suitable for TRT strategy. Other integrin αvβ3-positive tumor models and orthotropic tumor model should be involved in the further investigation. Our latest work of 68Ga-3PRGD2 imaging for the orthotropic GBM has showed the feasibility to treat GBM orthotropic tumor with 177Lu-3PRGD2 TRT 42.

Combination therapy showed comparable tumor growth inhibition to the two-dose TRT, but the latter does not need to repeat injection daily for weeks, which is more convenient and appreciatory for clinical use. Given the favorable in vivo properties of 177Lu-3PRGD2 and its promising tumor treatment efficacy in animal model, it could potentially be rapidly translated into clinical practice in the future.

Conclusion

177Lu-3PRGD2 exhibited high specific tumor targeting properties and relatively low uptake in normal organs, especially in kidneys and liver, leading to relatively low toxicity and higher MTD of 177Lu-3PRGD2, comparing with 90Y-3PRGD2. The high MTD of 177Lu-3PRGD2 made it more suitable for high dose or multiple-dose regimens, so as to achieve maximum therapeutic efficacy. Either the repeated high-dose regimen of 177Lu-3PRGD2 or combination treatment of 177Lu-3PRGD2 with Endostar potently enhanced the tumor growth inhibition. Compared to Endostar combined treatment, the repeated 177Lu-3PRGD2 does not need to inject daily for weeks, avoiding a lot of unnecessary inconvenience and suffering for patients, which could potentially be rapidly translated into clinical practice in the future to improve the outcome of integrin αvβ3-positive tumor treatment in clinic.

Supplementary Material

Methods, Table S1-S2, Figure S1-S4.

Acknowledgments

This work was financially supported, in part, by the Outstanding Youth Fund (81125011), “973” program (2013CB733802 and 2011CB707703), National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) projects (81000625, 30930030, 81222019, 30900373, 81201127, 81028009 and 81321003), grants from the Ministry of Science and Technology of China (2012ZX09102301-018, 2011YQ030114, and 2012BAK25B03-16), and grants from the Ministry of Education of China (31300 and BMU20110263).

Abbreviations

- DOTA

1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclododecane-1,4,7,10-tetracetic acid

- PEG4

15 amino-4,710,13-tetraoxapentadecanoic acid

- c(RGDfK)

cyclo(Lys-Arg-Gly-Asp-D-Phe)

- E[c(RGDfK)]2 (RGD2)

Glu[cyclo(Lys-Arg-Gly-Asp-D-Phe)-cyclo(Lys-Arg-Gly-Asp-D-Phe)]

- PEG4-E[PEG4-c(RGDfK)]2 (3PRGD2)

PEG4-Glu{cyclo[Lys(PEG4)-Arg-Gly-Asp-D-Phe]-cyclo[Lys(PEG4)-Arg-Gly-Asp-D-Phe]}

- PEG4-E[PEG4-c(RGKfD)]2 (3PRGK2)

PEG4-Glu{cyclo[Arg-Gly-Lys(PEG4)-D-Phe-Asp]-cyclo[Arg-Gly-Lys(PEG4)-D-Phe-Asp]}

- E{E[c(RGDfK)]2}2 (RGD4)

Glu{Glu[cyclo(Lys-Arg-Gly-Asp-D-Phe)]-cyclo(Lys-Arg-Gly-Asp-D-Phe)}-{Glu[cyclo(Lys-Arg-Gly-Asp-D-Phe)]-cyclo(Lys-Arg-Gly-Asp-D-Phe)}.

References

- 1.Begg AC, Stewart FA, Vens C. Strategies to improve radiotherapy with targeted drugs. Nature reviews Cancer. 2011;11:239–53. doi: 10.1038/nrc3007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Delaney G, Jacob S, Featherstone C, Barton M. The role of radiotherapy in cancer treatment: estimating optimal utilization from a review of evidence-based clinical guidelines. Cancer. 2005;104:1129–37. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fani M, Maecke HR, Okarvi SM. Radiolabeled peptides: valuable tools for the detection and treatment of cancer. Theranostics. 2012;2:481–501. doi: 10.7150/thno.4024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ersahin D, Doddamane I, Cheng D. Targeted Radionuclide Therapy. Cancers. 2011;3:3838–55. doi: 10.3390/cancers3043838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Veeravagu A, Liu Z, Niu G, Chen K, Jia B, Cai W. et al. Integrin v 3-Targeted Radioimmunotherapy of Glioblastoma Multiforme. Clinical Cancer Research. 2008;14:7330–9. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miederer M, Henriksen G, Alke A, Mossbrugger I, Quintanilla-Martinez L, Senekowitsch-Schmidtke R. et al. Preclinical Evaluation of the -Particle Generator Nuclide 225Ac for Somatostatin Receptor Radiotherapy of Neuroendocrine Tumors. Clinical Cancer Research. 2008;14:3555–61. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kwekkeboom DJ, de Herder WW, Kam BL, van Eijck CH, van Essen M, Kooij PP. et al. Treatment With the Radiolabeled Somatostatin Analog [177Lu-DOTA0,Tyr3]Octreotate: Toxicity, Efficacy, and Survival. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2008;26:2124–30. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.2553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu Z, Wang F, Chen X. Integrin alpha(v)beta(3)-Targeted Cancer Therapy. Drug development research. 2008;69:329–39. doi: 10.1002/ddr.20265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Danhier F, Breton AL, Préat V. RGD-Based Strategies To Target Alpha(v) Beta(3) Integrin in Cancer Therapy and Diagnosis. Molecular Pharmaceutics. 2012. 121004113049007. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Liu Z WF, Chen X. Integrin Targeted Delivery of Radiotherapeutics. Theranostics. 2011;1:10. doi: 10.7150/thno/v01p0201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beer AJ, Schwaiger M. Imaging of integrin alphavbeta3 expression. Cancer metastasis reviews. 2008;27:631–44. doi: 10.1007/s10555-008-9158-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yin Zhang YY, Weibo Cai. Multimodality Imaging of Integrin αvβ3 Expression. Theranostics. 2011;1:13. doi: 10.7150/thno/v01p0135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gaertner FC, Kessler H, Wester HJ, Schwaiger M, Beer AJ. Radiolabelled RGD peptides for imaging and therapy. European Journal of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging. 2012;39:126–38. doi: 10.1007/s00259-011-2028-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shi J, Liu Z, Jia B, Yu Z, Zhao H, Wang F. Potential therapeutic radiotracers: preparation, biodistribution and metabolic characteristics of 177Lu-labeled cyclic RGDfK dimer. Amino Acids. 2009;39:111–20. doi: 10.1007/s00726-009-0382-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shi J, Zhou Y, Chakraborty S. et al. Evaluation of 111In-Labeled Cyclic RGD Peptides: Effects of Peptide and Linker Multiplicity on Their Tumor Uptake, Excretion Kinetics and Metabolic Stability. Theranostics. 2011;1:18. doi: 10.7150/thno/v01p0322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Janssen ML, Oyen WJ, Dijkgraaf I, Massuger LF, Frielink C, Edwards DS. et al. Tumor targeting with radiolabeled alpha(v)beta(3) integrin binding peptides in a nude mouse model. Cancer Res. 2002;62:6146–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sudipta Chakraborty JS, Young-Seung Kim, Yang Zhou, Bing Jia, Fan Wang, Shuang Liu. Evaluation of 111In-Labeled Cyclic RGD Peptides: Tetrameric not Tetravalent. Bioconjugate Chem. 2010;21:10. doi: 10.1021/bc900555q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wu Y, Zhang X, Xiong Z, Cheng Z, Fisher DR, Liu S. et al. microPET imaging of glioma integrin {alpha}v{beta}3 expression using 64Cu-labeled tetrameric RGD peptide. J Nucl Med. 2005;46:1707–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li ZB, Cai W, Cao Q, Chen K, Wu Z, He L. et al. (64)Cu-labeled tetrameric and octameric RGD peptides for small-animal PET of tumor alpha(v)beta(3) integrin expression. J Nucl Med. 2007;48:1162–71. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.107.039859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu Z, Liu S, Wang F, Liu S, Chen X. Noninvasive imaging of tumor integrin expression using 18F-labeled RGD dimer peptide with PEG4 linkers. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2009;36:1296–307. doi: 10.1007/s00259-009-1112-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shi J, Wang L, Kim YS, Zhai S, Liu Z, Chen X. et al. Improving tumor uptake and excretion kinetics of 99mTc-labeled cyclic arginine-glycine-aspartic (RGD) dimers with triglycine linkers. J Med Chem. 2008;51:7980–90. doi: 10.1021/jm801134k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shi J, Kim YS, Zhai S, Liu Z, Chen X, Liu S. Improving tumor uptake and pharmacokinetics of 64Cu-labeled cyclic RGD peptide dimers with Gly3 and PEG4 linkers. Bioconjug Chem. 2009;20:750–9. doi: 10.1021/bc800455p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu Z, Jia B, Shi J, Jin X, Zhao H, Li F. et al. Tumor Uptake of the RGD Dimeric Probe 99mTc-G3-2P4-RGD2 is Correlated with Integrin αvβ3 Expressed on both Tumor Cells and Neovasculature. Bioconjugate Chem. 2010;21:548–55. doi: 10.1021/bc900547d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu Z, Shi J, Jia B, Yu Z, Liu Y, Zhao H. et al. Two90Y-Labeled Multimeric RGD Peptides RGD4 and 3PRGD2 for Integrin Targeted Radionuclide Therapy. Molecular Pharmaceutics. 2011;8:591–9. doi: 10.1021/mp100403y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ma Q, Ji B, Jia B, Gao S, Ji T, Wang X. et al. Differential diagnosis of solitary pulmonary nodules using (9)(9)mTc-3P(4)-RGD(2) scintigraphy. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2011;38:2145–52. doi: 10.1007/s00259-011-1901-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhao D, Jin X, Li F, Liang J, Lin Y. Integrin alphavbeta3 Imaging of Radioactive Iodine-Refractory Thyroid Cancer Using 99mTc-3PRGD2. J Nucl Med. 2012. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Zhu Z, Miao W, Li Q, Dai H, Ma Q, Wang F. et al. 99mTc-3PRGD2 for integrin receptor imaging of lung cancer: a multicenter study. J Nucl Med. 2012;53:716–22. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.111.098988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schmidt NO, Ziu M, Carrabba G, Giussani C, Bello L, Sun Y. et al. Antiangiogenic therapy by local intracerebral microinfusion improves treatment efficiency and survival in an orthotopic human glioblastoma model. Clinical cancer research: an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2004;10:1255–62. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-03-0052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Luna-Gutiérrez M, Ferro-Flores G, Ocampo-García B, Jiménez-Mancilla N, Morales-Avila E, De León-Rodríguez L. et al. 177Lu-labeled monomeric, dimeric and multimeric RGD peptides for the therapy of tumors expressing α(ν)β(3) integrins. Journal of Labelled Compounds and Radiopharmaceuticals. 2012;55:140–8. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ke Q-H, Zhou S-Q, Huang M, Lei Y, Du W, Yang J-Y. Early Efficacy of Endostar Combined with Chemoradiotherapy for Advanced Cervical Cancers. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention. 2012;13:923–6. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2012.13.3.923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chamberlain MC, Cloughsey T, Reardon DA, Wen PY. A novel treatment for glioblastoma: integrin inhibition. Expert review of neurotherapeutics. 2012;12:421–35. doi: 10.1586/ern.11.188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee JH, Song JH, Lee SN, Kang JH, Kim MS, Sun DI. et al. Adjuvant Postoperative Radiotherapy with or without Chemotherapy for Locally Advanced Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Head and Neck: The Importance of Patient Selection for the Postoperative Chemoradiotherapy. Cancer research and treatment: official journal of Korean Cancer Association. 2013;45:31–9. doi: 10.4143/crt.2013.45.1.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee FT, Mountain AJ, Kelly MP, Hall C, Rigopoulos A, Johns TG. et al. Enhanced efficacy of radioimmunotherapy with 90Y-CHX-A''-DTPA-hu3S193 by inhibition of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) signaling with EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor AG1478. Clinical cancer research: an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2005;11:7080s–6s. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-1004-0019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dumont RA, Tamma M, Braun F, Borkowski S, Reubi JC, Maecke H. et al. Targeted radiotherapy of prostate cancer with a gastrin-releasing peptide receptor antagonist is effective as monotherapy and in combination with rapamycin. J Nucl Med. 2013;54:762–9. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.112.112169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liang J, E M, Wu G, Zhao L, Li X, Xiu X. et al. Nimotuzumab combined with radiotherapy for esophageal cancer: preliminary study of a Phase II clinical trial. OncoTargets and therapy. 2013;6:1589–96. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S50945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Robertson R, Germanos MS, Manfredi MG, Smith PG, Silva MD. Multimodal imaging with (18)F-FDG PET and Cerenkov luminescence imaging after MLN4924 treatment in a human lymphoma xenograft model. J Nucl Med. 2011;52:1764–9. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.111.091710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brans B, Mottaghy FM, Kessels A. 90Y/177Lu-DOTATATE therapy: survival of the fittest? Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2011;38:1785–7. doi: 10.1007/s00259-011-1878-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kwekkeboom DJ, Kam BL, van Essen M, Teunissen JJ, van Eijck CH, Valkema R. et al. Somatostatin-receptor-based imaging and therapy of gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Endocrine-related cancer. 2010;17:R53–73. doi: 10.1677/ERC-09-0078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lewis JS WM, Laforest R, Wang F, Erion JL, Bugaj JE, Srinivasan A, Anderson CJ. Toxicity and dosimetry of (177)Lu-DOTA-Y3-octreotate in a rat model. Int J Cancer. 2001;94:5. doi: 10.1002/ijc.1540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yoshimoto M, Ogawa K, Washiyama K, Shikano N, Mori H, Amano R. et al. alpha(v)beta(3) Integrin-targeting radionuclide therapy and imaging with monomeric RGD peptide. Int J Cancer. 2008;123:709–15. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Peng F, Xu Z, Wang J, Chen Y, Li Q, Zuo Y. et al. Recombinant human endostatin normalizes tumor vasculature and enhances radiation response in xenografted human nasopharyngeal carcinoma models. PloS one. 2012;7:e34646. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shi J, Fan D, Liu X, Yang L, Yan N, Sun Y. et al. Dual PET and Cerenkov luminescence imaging of a kit-formulated integrin αvβ3-selective radiotracer 68Ga-3PRGD2 in human glioblastoma xenografts and orthotopic tumors. Abstract Book Supplement to the Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 2013;54:1. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Methods, Table S1-S2, Figure S1-S4.